-

Was Nietzsche right about this?thats interesting, I had forgotten about Hegel, but I dimly remember being told he said it. Do you happen to know the reference?

-

Was Nietzsche right about this?Was Nietzsche correct that the ‘death of God’ would usher in a time of meaninglessness and bloodshed? — Tom Storm

Obviously, this is one of Nietzsche's sensationalist remarks, as the God he is saying has died cannot by definition die (or rather die again if one includes Jesus in it).

People these days have alot of trouble understanding what a God is. If the Romans were still in power, they would say Santa Claus is a God. For good reason. Belief in him controls 15% of the world economy. Gods are not born, they are created. Gods do not die, they are lost.

Nietzsche's statement is certainly enough to inflame the imagination of the embittered, which is rather apparently his intent. -

(Poll) Sabellian Heresy versus Orthodox TrinitarianismThe paradox is not to do with God. It is to do with the Holy Spirit and Christ existing before Man did.

Perhaps someone could explain why so many people have a problem understanding the quesiton. It is a very frequent response. -

Time and the presentI think it is a misunderstanding of Kierkegaard's intention to read being 'present but not present' before a child's inward reserve to mean the same thing as a "hands off" style of parenting that only notices the child's experience when bad things happen. — Valentinus

Well I dont know, lol, being forced to work 364 days a year by his parents, with only Christmas off did, apparently cause his obsessive reiteration of one tragic religious narrative about one of Christ's ancestors, Abram, and his intended sacrifice by his father, in an entire book on the subject titled 'Fear and Trembling and Sickness unto Death.' One needs to bear in mind that Christ also was to be sacrificed by his Father, even at his birth.

So I'd have to say, with regrets, the extent his views were colored by his childhood experience can only be a matter of opinion. I mean, how many people ever want to talk about trying to forgiving their father that much? lol.

Personally, if I learned anything important from K, it was how much suffering God must have felt Himself to sacrifice his Son for the sake of our sins in the conventional account of Christ's life, something normally ignored during the glittering Christmas celebrations of Western Protestantism. -

Time and the presentIt was aphorism gathered by his, um sister, for his last book Ecce Homo, by which time he had become increasingly incoherent. Both source and translations vary.

-

Is my red innately your redDon’t make the mistake of assuming that this capacity to recognize feeling in music is either ‘innate’ or just a concatenation of reinforcement contingencies. — Joshs

I don't lol. Musical patterns are learned. Recently they found a songbird species that had forgotten its song

https://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-56417544

Have a nice day ) -

Is my red innately your red

Colors are not physical phenomena, they are perceptual phenomena, and as such are the achievement of a constructive process. They are intentional acts , and like all acts, they produce a change of sense. Colors may not present ‘intrinsic’ properties on the order of qualia, but they do present us with the experience of a transformative construction. For instance, the perceptual act of color constitution is created primoridally as a black shape either emerging out of or receding into a dark background. You can demonstrate this yourself. Cut out a white cardboard circle, paint one half black , and then draw a series of black lines following the curvature of the circle on either side of the disk emerging from the black half. Then attach it to a fan and watch the appearance of red and blue. — Joshs

So I thought about it, and I think you have a point, but it's more complicated. there's three parts to it:

1) Object and Lighting Properties

2) Visual Processing

3) Color Associations

1) Object and Lighting Properties

As you observe, apparent colors change, but it does not need such a sophisticated experiment as moving objects. It happens all the time. A white balloon outside looks 'white' most of the day, but if I carry it into shadow, it looks grey. At sunrise and sunset, it looks red. Color is an object's absorptive and emissive spectra COMBINED WITH its reflective, specular, and translucent properties, MODIFIED BY the color of the light falling on it.

2) Visual Processing

An object's apparent color is FURTHER MODIFIED BY internal processing we perform to modify brightness, detect edges, and detect movement in the visual pre-cortex. Our irises dilate and contract to adjust the light intensity to our optimal detection processing. Muscles distort the eyeball's curvature to focus on different distances. Early processing compensates for these artefactual contraptions. And we know some of the further processing by dissecting the ocular pre-cortex nerve structures. There is a 'crossover network very early in the nerve chain to enhance edges, for example. At some point in the visual processing, the effects of changes to the eye for different lighting and focal length are 'canceled out' so we are not normally aware of them. We make so many internal modifications in our brains depending on our lighting conditions that are so innate, you may not have consciously realized them, lol.

Most people don't. Van Gogh, who actually had very bad vision and wore glasses, painted stars with rings around them because that's what he saw through his glasses (he liked to paint when it was raining, or he was in a smoky room). Most people don't realize 'Starry Night' is Van Gogh trying to paint what he actually saw. Here's another Van Gogh example.

People who wear glasses, or sunglasses, adjust after a few days and stop noticing the artifacts. Another obvious example is that the image on the inside of the eye is actually upside down. People can wear glasses that make the image upside down before it reaches the eye, and adjust to it, and don't notice it after a few hours. That is to say, the processing is innate, but it is not completely hard-wired. We can learn to turn parts of it on and off.

3) Color Associations

There is an associative element to the 'meaning' of color. This may form at an early age. Suppose we are waiting in a dark room as a baby, and our mother comes in and turns the light on, then feeds us. Then when she leaves she turns the light off. This makes an association in our minds that bright light is good, and shadows are bad.

I believe such associations at a very early age explain much of what we personally 'feel' about color. As we grow older, we form more associations, which are more direct, such as red being 'danger' because of traffic lights and blood. But even those learned associations with world phenomena at later ages are already 'tinted' by our earliest perceptions when little meant sense to us at all, and that's what makes color such an intensely personal experience. -

Darwinian Doubt - A logical inquiryI would say that they arise from the extension of methodological naturalism to a metaphysical principle. — Wayfarer

well yes, I'd have ot think how much methodological naturalism varies from a scientific method, I would guess the second is similar but extends to a larger scope. -

Darwinian Doubt - A logical inquiryThe argument is about evaluating truth statements. Every surviving species, other than h. sapiens, manages to survive and procreate without any such ability whatever. Only a sentient being with the ability to think and speak is even able to contemplate such a question. — Wayfarer

With regrets, I have to object that the actual process going through the brain of an animal species is largely beyond our comprehension. There are some specific examples of animals demonstrating complex reasoning tasks. For example, I have seen demonstrations of crows figuring out sequences of half a dozen levers to push and weights to move in a particular sequence, in order to obtain food. I have seen chimpanzees demonstrate knowledge of object permanence. And I have seen dolphins show they can distinguish between rounded shapes and shapes with corners. These demonstrations show that animals can form ordered, rational deductions from abstracted principles. Therefore, there must be SOME mechanism inside their brains which is able to evaluate at least a subset of logical propositions, as we know them, and we can't actually know if the animal is aware of the cognition, or if it happens in the same automatic way as electricity flows through a circuit when a battery is attached to it.

With reference to above on Tom Nagel, there is also his famous paper 'what's it like to be a bat?'

https://www.sas.upenn.edu/~cavitch/pdf-library/Nagel_Bat.pdf

And what is the significance of that to the OP, well I think it is a general criticism of the evolutionary debate that it focuses on God versus automatic processes, which I had posted yesterday and had thought the posters had read and started a new thread, but if not:

First, if God is more intelligent than we were 5,000 years ago, then God uses tools. Using natural selection to do most the work, while tweaking a DNA pair here and there would be a natural thing for an intelligent creator to do.

Second,making the argument solely about natural selection versus traditional concepts of God ignores the presence of other possible teleological forces. An animal might simply have a sense of beauty, and prefer the appearance of one animal over another because of that. I understand some would say such teleological processes are themselves product of natural selection. But that defeats the point of the scientific model of evolution in the first place, which was, to provide as simple a model as possible to explain observed species variation. Once one starts annexing suppositions as to causality to the Darwinist theory, or suppositions of what animals actually think, then it is no longer a scientific theory. Now one might prefer to make metaphysical statements, rather than construct a scientific model, but in that case, the conventions of science no longer apply to the conclusions. Most of the errors here noted, and most subjects of evolutionary debate, arise from attempts to extend a scientific model of natural selection to include causal explanations that are emprically untestable, and therefore, not scientific. -

Time and the presentI think N's remark might definitely apply to K's opinions on parenting, but I agree in general, N was prone to vast generalizations.

-

Is my red innately your redThis explains why red is often a metaphor for anger and aggression, and blue can represent calm and coldness. — Joshs

that is AN explanation. One of many. lol. Let me think about it, thanks for the thoughts. -

Darwinian Doubt - A logical inquiryits a very popular delusion that Trump is gone. He and his tribe are only in recess. Last week, Judge Thomas said he is oipen to arguments that banning Trump from Twitter was a violation of free speech, and as he is in a GOP-majority supreme court, it means his tweets are coming back, like it or not, whether he or one of his tribe run, he's coming back. And probably will win. He came a lot closer to winning after his covid denial than I expected, but if not, I really dont want to be here for the next round of riots. Come to Europe ) lol. Im going for a walk, later.

-

Darwinian Doubt - A logical inquirywell no, thats not what happens, because most simply put, EMPLOYERS DONT HAVE AS MUCH INCOME TO HAND OUT, which was a severe and catastrophic effect in a tabu period in US history after the civil war, the only periopd in US history even closely comparable to the USSR. It's not taught much in schools, and the information on it is pretty dicey, because another effect is rampant inflation, which disguises the effects of losses to individuals if you wish to be a deviant economist, and inflation wasnt understood at all at the time, but you can see about it if you look up 'long depression' on the Web, during which, wages first plummeted due to increased workforce size from setting slaves free, tens of thousands of businesses and farms foreclosed from lack of income, then almost all the banks went bankrupt, almost everyone lost all their savings, and millions starved to death. Even the exact duration of the 'depression' varies where you see about it, and due to inflation not being understood, it wasn't obvious why so many people were suffering from not having money. But it wasnt as bad as the loss to russia of its new industrial workforce, and only lasted one or two generations instead of three or four. It's really a horrible subject and if you excuse me Im going for a walk. Have a nice day )

-

Darwinian Doubt - A logical inquiryyes, that's right. In an industrial economy, a sudden decrease in population results in lack of commodities, depressed wages, lower education standards, and all the many other disadvantages that led to the end of massacring peasants in feudal wars, although it did take several thousand years of human civilization to figure that out, so empirically, its something you actually have to learn by studying it. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/World_War_II_casualties_of_the_Soviet_Union

-

Darwinian Doubt - A logical inquiryWell the USSR had the opposite problem to the USA in the 1970s. The USA used to be in growth mode and has been trying to reverse long-standing social protocols, such as turning a blind eye to illegal immigration so that illegal immigrants could work on farms at sub-minimum wages. The USSR in the 1970s was still recovering from its massive loss of life in WW2, and still has a relatively low population, although not to the drastic level of underpopulation it has for the first three generations after WW2. So its reward to women having more than 10 children, a vacation in Moscow with a medal award for service to the nation, was lowered to 8 children, then discontinued.

-

Darwinian Doubt - A logical inquiryYes, Im still thinking about that. As of the current state of affairs, the left and the right have 'evolved' into purely combative positions that don't even act in their own self interest. If the left had impeached Trump for violating his oath of office and not protecting the life of Pence, instead only calling to find out if he had changed his mind about election certification before Pence escaped, there would have been no logical possibility of him beating the impeachment. But the left chose to impeach him for starting an insurrection, again making dubious claims of unprovable immorality. What I currently find of note is the number of criticisms that can now be made of the US government, parties aside, that it previously made of the USSR in the 1970s:

* The largest wealth disparity ever

* Biased news propaganda

* Six times more military spending than any other nation

* 'Tactical nuclear bomb' development sidestepping nuclear treaties

* Governmental incompetence, including, being unable to remove the President from opffice.

* Forest fires with smoke so thick for hundreds of miles you can't see more than 100 yards for a month.

* School illiteracy, widespread ignorance, riots, and gun murders

* Homelessness, alcoholism, wife abuse, runaway teens, and opiate addiction

* Labor exploitation without unions being able to protect worker rights

* Highest incarceration rate of any country ever

* Human rights violations up to and including torture

* This year, four trillion dollars of pork-barrel spending without any compromise.

* And most recently, the Supreme Court just indicated that there would be no problem with approving Trump getting back on Twitter, saying it was a violation of free speech to ban him...so, the President has licensed freedom to say anything he wants.

the only signficant difference between the USA now, and the USSR as it was in the 1970s, is that it has two parties exercising decadence without check instead of one, to little apparent benefit. Thus partisan differences of opinion are really no longer the issue. Now we are confronted with the time delay of an issue reaching the point where it can be taken seriously enough to warrant ANY political action. For slow moving problems like global warming, the USA appears incapable of taking any effective action at all. Consider, its last Supreme Court decision on gun control permitted limited use of some firearms in self defense, without defining the limits or which firearms, in 2008. Since then, the USA has had more firearm fatalities than died in WW2, which was the justification for trillions of spending against COVID this year. Yet despite repeated attempts at gun control since 2008, special interest groups have fought firearm limitations in court so much that gun deaths are still going up. Global warming is a similar issue to guns, and the outlook is bleak. -

Darwinian Doubt - A logical inquiryMy biggest problem, though, is Stephen Meyer. He attempts to resolve Darwin’s Doubt by saying that intelligent design is the only explanation if evolution is true. This makes it more difficult for me to notate this.

How would I write that? — Georgios Bakalis

[url=http://]https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/If_and_only_if[/url]

While it might seem an outlandish proposition, it does have the benefit over current natural selection theory of actually being falsifiable, as it does not admit to 'unknown selection force.' -

Darwinian Doubt - A logical inquiryCausality is a huge selection pressure. — counterpunch

That's funny, I woke up this morning thinking Trumpism might be a brain dysfunction, rendering the individual incapable of performing simple truth evaluation of standard causal relationships if they conflict with hedonist desires.

Maybe the dysfunction has even proven to be the fittest solution to the last moments of survival on a doomed planet, as the authority structure in the human race's most powerful social organization on the planet has not evolved to the point of consistent rational response to the threat of global warming.

My favorite remains Trump's modification of a USGS weather map with a black felt marker he is holding in his hand while 'proving' a storm should reach Georgia as he claimed, and the USGS had already repeatedly denied. If only such acts really had been intended as a joke, he would have been one of the greatest comedians ever. -

Is Kant justified in positing the existence of the noumenal world?Oh I was just checking my tickets to move to Europe, lol, I agree with you on Biden too, but I better not get into it. Sweet dreams to you too )

-

Is Kant justified in positing the existence of the noumenal world?lol, I have no idea what is happening in the mind of Trump, or his supporters, but whatever illogical process it is that enables them to decide what is true, and whatever 'representation of reality' they have if any at all, its beyond me, but they are winning

Chief Justice Thomas said last week he'd be 'open to hearing' arguments that Twitter violated rights to free speech by banning Trump. As its now a GOP majority in the supreme court, that means, without question, more Trump tweets by 2024. Fait accomplis. One could wonder how long ago Trump knew that would happen i guess, but its here now. More Trump tweets.

There's no rational explanation for this or any 'representation of reality' it fits in lol. Its insane. Sorry I have to go to bed. Good night ) -

Is Kant justified in positing the existence of the noumenal world?We'll die out if we are not correct to reality. — counterpunch

That is a logician's assumption. For lower-order concepts, there is obviously a need to distinguish between what is food and not food. Above basic, first-order concepts on the needs of life, it's not actually clear that the abstractions logicians consider necessary truth actually are either necessary or true. From a logician's point of view they are. From Schopenhauer's or Nietzsche's point of view, that's even naive. Human beings do not control themselves based on a logician's view of 'reality' and from what behavior ive observed in the USA during the Trump administration, human beings dont care how many people it kills either, as long as those with power are having their desires satisfied. -

A poll on hedonism as an ethical principleUilitarianism refers to maximization of 'happiness,' not 'pleasure,' and the definition of happiness is deliberately avoided. The semantic confusions over semantic pleasure versus higher order pleasures led to the choice of happiness over pleasure.

Hedonism refers to a family of theories, all of which have in common that pleasure plays a central role in them. Psychological or motivational hedonism claims that our behavior is determined by desires to increase pleasure and to decrease pain.[1][2] Normative or ethical hedonism, on the other hand, is not about how we actually act but how we ought to act: we should pursue pleasure and avoid pain.[2] Axiological hedonism, which is sometimes treated as a part of ethical hedonism, is the thesis that only pleasure has intrinsic value.[1][3][4] Applied to well-being or what is good for someone, it is the thesis that pleasure and suffering are the only components of well-being.[5] — wikipedia

Hedonism strictly referred to pleasure, and avoidance of pain, in classical times, including by Epicurus. Locke was rather unique in saying that the greatest happiness arises from acting for the common good. It was the reason Jefferson included the right to pursue happiness as a natural right, but despite over a decade now trying to point that out, all universities and politicians deny it because, as Locke also pointd out, acting for the greater good rarely gives rise to happiness in this life. One must accept the existence of an afterlife for it to be justly rewarded. Therefore to accept Jefferson's original definition of pursuit of happiness as a natural right, one has to accept the right exists as a consequence of the USA being a Christian nation. That is too objectionable for many to accept, so now 'the pursuit of happiness' is considered more hedonistic, or if you are Epicrus, egoistically hedonistic. -

A poll on hedonism as an ethical principleI agree with what you are saying, but people don't NORMNALLY think of hedonism as being something one does for other people. It's considered generally to be more self-oriented pleasure. But if you have reasoned that the greatest pleasure is acting for the greatest of good, then I'd agree, but I'd say, you're getting as weird as Locke. lol.

-

A poll on hedonism as an ethical principlemaybe happiness is a virtue, but virtue isn't happiness. lol.

-

A poll on hedonism as an ethical principleI don't quote follow what you mean that that "totally implodes the entire concept of 'ethical hedonism'", though. — Pfhorrest

well, if the definition of 'hedonism' is extended to include 'acting for the greater good' it isnt really hedonism any more, it's virtue instead. -

Is Kant justified in positing the existence of the noumenal world?One can dispense with the idea of the world as representation by accepting that the experiencing mind is part of the reality it experiences, — counterpunch

That's not actually true. Just because a biological mechanism exists to produce the representation does not mean that the abstractions are 'part of reality.' It means that the abstractions do exist, and therefore, higher functions of the mind must be supported by mechanical apparati which typically don't do a very good job at ensuring all members of the species are actually capable of handling higher-level abstractions without making fundamental errors. Some even dispute the process of reason is actually an advantage, calling it 'intellectual elitism' or some such, and they've had alot of success, so it's not even clear the ability to reason is a competitive advantage in the first place. False representations of reality go a long way these days. -

Is Kant justified in positing the existence of the noumenal world?Hi, I didnt yet read the other posts, but to answer your first:

Suppose you put some water in a kettle on the stove and turn its burner on. Now according to common thought, we know the water is going to boil.

In fact, we only predict the water is going to boil from the model of the apparent observable world that we construct in our mind as part of our learned experience of it. We think we know the water will boil because in most cases it does. However, we dont know it until after it does boil, before which, for example, the gas mains or some other unlikely event could cause it not to. In a similar way, all experience leads us to believe we have 'knowledge' of a posteriori events, but the knowledge is really assumed prediction from prior experience, and not certain knowledge.

What Kant tried to do was to define knowledge that could be known independent of observed 'a posteriori' events, which he called 'a priori' knowledge. That distinction is still valid, but some reasonably doubt whether it is truly knowledge that can exist independent of thought.

The noumenal world is not part of a priori knowledge, although partly constructed upon it, it is the representation of the apparent observable world in our minds. This has been a difficult topic in philosophy as it has not been possible to construct empirical tests which distinguish between different possible versions of such a noumenal world, and some challenge whether it exists at all. While one can refine different alternative views, they are still opinions, which some adopt religiously, and others deny religiously. And there are views that only language exists, for example, in Wittgensteinian metaphysics, in which case the whole debate is only a language game.

At Oxford I was taught to consider many of these views, and my tutor spoke of their relative 'merit.' The merit of a view is not only derives from its logical coherency and usefulness in explanation, but also from its teleological nature, that is, what benefits it provides to science, law, ethics, and other modern fields which still rely on philosophy as their foundation. Many philosophers will of course scoff at that, especially existential cynics, but Oxford does not have a great deal of respect for existential cynics as contributing much to the quality of life, so the feeling is mutual.

So then you may ask, what is a 'reasonable doubt' of a priori knowledge? A reasonable doubt has to provide an equally cogent explanation for what the epistemological status of logic and mathematics actually is, and there hasn't been many of those. There are those who simply scoff or deny, and their philosophical position is of little merit.

Part of the reason I haven't looked in detail at the thread here is that existential cynics, especially nihilists, have staged rather a takeover of this forum for some extended periods of time in the past, and I dont really have the spiritual presence of mind to maintain a pleasant face to them in many cases. But I am glad to see you at least started this thread with a very good issue ) -

Time and the present

The art is that of constantly being present, and yet not being present, so that the child may be allowed to develop himself, and at the same time one has a clear view of the development. The art is to leave the child to himself in the very highest degree and on the greatest possible scale, and to express this apparent relinquishing in such a way that, unnoticed, one is aware of everything. If only one is willing, time for this can very well be found, even though one is a royal officeholder. If one is willing, one can do all things. — Same translation as above, starts within section (IV 393)

Well, K makes alot of assumptions about others having experience as horrible as his own, as he was required from an early age to work 364 days a year, just getting Christmas off, for almost no pay.

As N said, every philosophy is a kind of specious autobiography. That might also not apply in all cases, but from one existentialist to another, it appears particularly suitable.

I can't agree with K's assessment. My parents left me entirely alone until I did something stupid, then blamed the other for raising me wrong as part of their 15-year-long-divorce, while punishing me for it with relish. So we all serve different purposes to our parents, dont we, lol -

God and antinatalismIt turns out I was actually a psychologist, and I agree my first answer was not appropriate, but my second was.

-

A poll on hedonism as an ethical principlehi. One can conclude alot of weird things about hedonism.

The best Ive seen yet is Locke's which was that acting for the greatest good yields the greatest pleasure. That was really good, I'll look up the quote if you like, because it totally implodes the entire concept of 'ethical hedonism.' lol.

Have a nice day ) -

God and antinatalismAgain, seek professional help, and don't expect any more replies from me. — ernest meyer

-

God and antinatalismDouble bind, and double binds are not atypical for sociopaths, in fact it is one of the preferred techniques for such minded people.

You are SERIOUSLY mentally ill to propose an argument that God doesnt want children too.

I didnt want to say it the first time, but you asked for it.

Again, seek professional help, and don't expect any more replies from me. -

Economic IdeologyWell, I booked a passage on a cruise, and as I had a spare bunk I posted an ad on social media saying someone could have it. So this cute college girl said she'd like it, and within a week, I was getting urgent messages saying her cash card had been declined in the supermarket, and she needed an 80 buck transfer to her web thingie right away.

So maybe society can live without money if everyone was born 40 years old and already was in an earning career, but as far as kids go, they dont have the social responsibility for it, exempla gratia. -

God and antinatalismwith respect, you are a very intelligent person, but if you are so down on life that you telling others that life a prison, you need to see a professional mental health counsellor. Respectfully, but you need to.

-

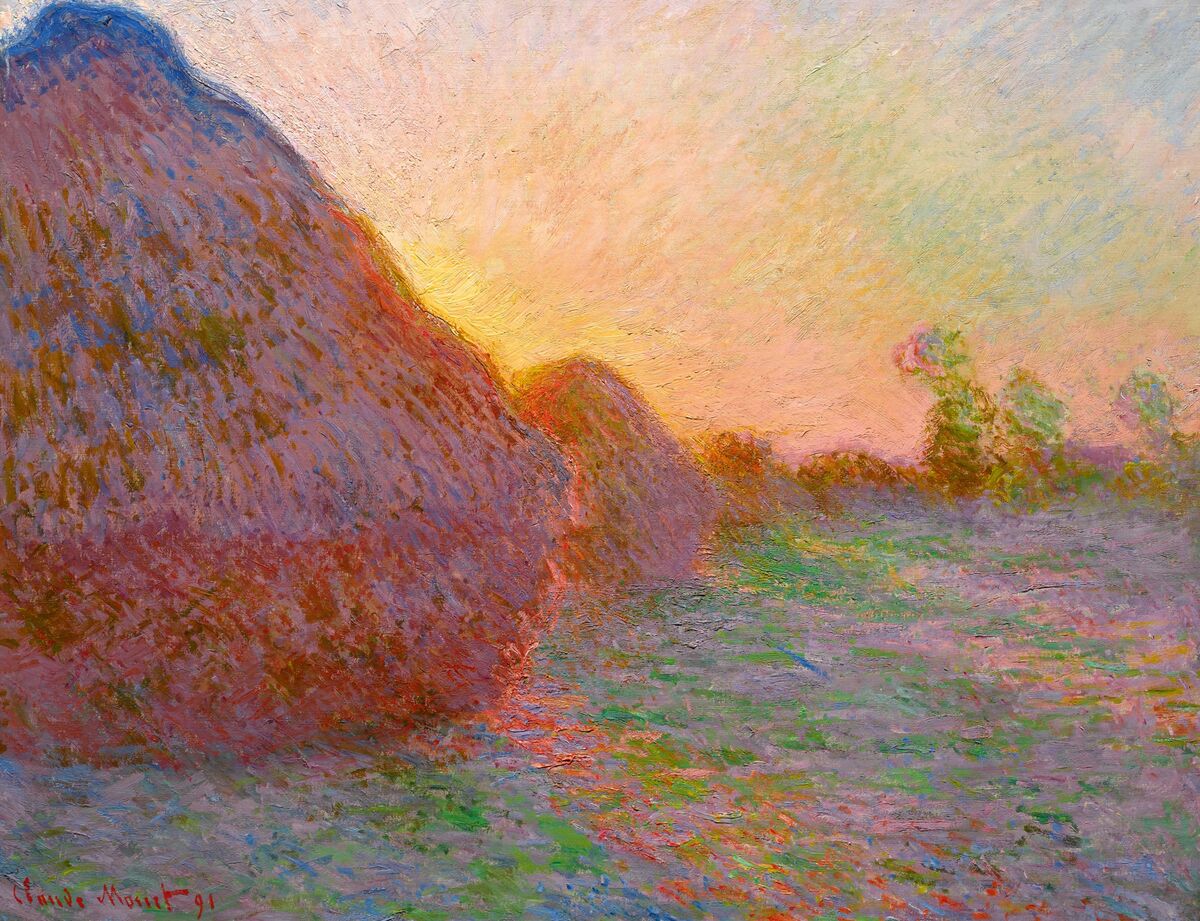

Is my red innately your redHAYSTACKS AT SUNSET - MONET

Some of the last thoughts by the metaphysical logician Wittgenstein were on the mystical nature of color. He asked the question whether color was imbued in physical substance, or an artifact of our perception, to which he felt there was no final answer. In his earlier thought, that would have been all that could be said. But in his later thought, the discussion of color becomes meaningful when we wield the concept like a tool.

While many have scoffed at the ridiculousness of considering something like color in so much depth, consumerism has indubitably transformed color into a commercial tool. One may only witness the incredible number of packages and brands distributing lipstick and eye makeup colors at the entrance of any local pharmacy, where once there were medicines and common household goods.

This proliferation of 'color for sale' inside the caverns of our stock houses replaces appreciation of the natural colors around us, and their sensitive purpose. Primary in this spectrum is the color of the chloroplast's photosynthetic mechanism. We are attuned to see this vivid green most of all, because that mechanism is how plants create and sustain all life on the surface of this planet. The hues around the green of growth are therefore most frequently easiest for eyes to see, and therefore dominated by peculiar evolutionary developments, such as flowers and fruits to attract animal life and encourage it, in the most bizarre forms of symbiosis, to propagate the seed of the sedentary plant. Yet no one complains of this massive act of domination, but instead considers it only with pleasure, for all the benefits that the plant provides to animal and human experience.

From this each culture has attached its own secondary associations. For example, in the West, scarlet is associated with danger, and forbidding of action; whereas in the East, scarlet is the color of parties and festivities, across cultural, familial, and political realms.

The subtlety of Wittgenstein's thought was to identify that association as being arbitrary, or rather, without logical necessity, yet still existent and powerful enough to be a causal agent. We are influenced by color, both by deep evolutionary forces, and by abstract cultural associations; yet the colors themselves possess no intrinsic properties to cause such influence. The colors themselves are no more than labels we apply to a physical phenomena (parts of the electromagnetic spectrum, in this case). When engaged in tantric meditation, we are encouraged to perceive beyond the direct physical manifestation, and to discover the strange and illogical passions to which such phenomena can bend our unconscious will. To the insights from such introspection the tantric gurus attach the names of Gods and forces to which they claim direct and irrefutable knowledge. It is the path of Wisdom to pass by such exaggerations without verbal debate; for if some person becomes convinced of a supernatural connection at the borders of perception, there is no verbal dissuasion possible from the delusion.

The irresolvable question to Wittgenstein nonetheless remained: we have the capacity to consider the nature of experiencing a color, such as the paradoxical nature of scarlet, without connection to any physical object directly, but merely as a property of itself.

The word 'merely' is in this case no diminishment, but rather remarkably, in some ultimately unknowable absolute sense, a humble portal to a deeper understanding of conceptual reality. In some respects, our understanding must always be limited, for, how much can we truly appreciate the different associations of any particular color to different cultures?

It even remains perplexing to those who share in communal joy, for example, this picture of haystacks by Claude Monet, even while others pass it by in disdain and scornful abjuration of those who find peaceful appreciation within it.

For any introspective insight we obtain, no matter how wise it may be to ourselves, remains only for ourselves, if we find no way to apply that insight for the omniversal influence of society.

From our insights we may choose sides, and argue for example that such concepts as color could exist without any contemplation of such concepts by any thinking being. If so, we may pause to consider what concepts remain yet to be considered. For if there exist concepts by themselves, not in the thoughts of any conscious entity, then there might remain concepts of reality as yet unknown by any person at all.

If you look again at Monet's painting, perhaps now the striking scarlets in the haystack appear in new shades of our imagination. In the distant hazy cottages we may infer, from this color, the joyful and industrious party of farmers embarked on celebration of their haymaking. We may infer, from this color, the warmth inside the haystack itself, lingering more slowly inside the straw bundles, during the twilights of sunset. Others may share the imagination and inference of Monet's intent. But within Monet's own silence, we find no confirmation of our speculation, and our insights persist only as hypothetical inferences of his intent. Those who claim some perfect understanding of reality may have deep contributions to make on its underlaying precepts, but for most of our knowledge of others' experience, the veil of postulation is too impenetrable to remove the bias of personal perspective.

We may also choose to believe there are no abstractions beyond those conceived by conscious entities. Leibniz argues that we see imperfectly that which is totally and perfectly understood by God, from which our own abilities of understanding and imagination propagate. Modern thinkers prefer to remove more majestic conceptions with Occam's razor, diminishing us further into the effervescent randomness of physical events.

Yet no matter how much the nihilists and cynics scoff, too many are struck by the beauty of material order and fantastic structures of rational thought, leading to mathematics and the physical sciences. Too many find something more in such as a painting by Monet; a sense of wonder, undeniable in strength, somehow demanding finer resolution of our own understanding, within the passing of days, and seasons, and eras of our civilizations. -

Interesting concept - monkeys playing "pong" on a computer.Not so weird. When they hit the ball right a machine gives them a food pellet within a second, together with an immediate different sound to cue the association directly. Monkeys are fast learners, you only need to show them it working a couple of times and they do it themselves. Human beings only need the sound, lol.

-

Arguments for having Childrenyes, but like most others on the topic, he only considered the impact to personal existence, lol. After a while it gets a little old having to say that to philosophers and it gets depressing actually.

-

Arguments for having ChildrenNo, the issue is, that other people who do not accept suicide as a solution are left to clean up the mess afterward, and that is something Schopenhauer did not consider.

-

Arguments for having Childrenwhat happens is that the people I ask all want me to start paying their bills. An executor would also be responsible for me if I become incapacitated, and I just cant trust the person sleeping under a bridge etc to do that, and it seems better just to let the state appoint a probate officer. Its actually one of the associated reasons I am planning to leave the USA lol, I dont think it would be a problem in other places. Well thats me for the day. All the best )

ernest meyer

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum