-

Currently Reading

The law of custom, imposed by force, will always be with us. And, yes, that creates the space of individual freedom. But I'm thinking something more along these lines: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Antinomianism -

Currently Reading

Actually I just read about that ambiguity. I think goal and end are both appropriate for my purposes, since I see the Law in its evolving manifestations as rungs on the ladder. But the ladder is thrown away. Of course this (for me) is "creative misreading." Or rather it doesn't matter what Paul meant. As I see it this Christ idea or personality is as radical as it gets, transcending any tradition that contingently lights it up in one's mind.

I like some aspects of conservatism. But I just want to clarify again what I see as a separation between religion at its height and politics. -

MysticismHere are few oneliners I hadn't seen before that seemed to fit with the theme.

Abjection is a methodological conversion, like Cartesian doubt and Husserlian epoche: it establishes the world as a closed system which consciousness regards from without, in the manner of divine understanding.

The world is sacred because it gives an inkling of a meaning that escapes us.

In doing Good, I lose myself in Being, I abandon my particularity, I become a universal subject.

One is still what one is going to cease to be and already what one is going to become. One lives one’s death, one dies one’s life. — Sartre -

MysticismI use this stance in contemplation of divine geometry such as squircles( giggle) transcendent states and techniques, along with a kind of personal subjective preening, or sorting and refining of conceptual architecture in the self. There is also a clear division, or membrane between side A and B, here, although the activity bridges this divide and there is also a process of conceptual refraction across the membrane enabling more subtle conceptual sculpting. — Punshhh

It sounds like you've got something good going on. I can't help but interpret this "A" and "B" as names for different mental states. I don't believe in squircles, but I love the word. I do of course know some beautiful math. The real numbers are a black and seamless sea, and also an "uncountable" infinity. Unlike the rational numbers, we can't print them out one by one or line them up. It's beautiful to me that such psychedelic and "drippy" numbers get called the "reals." The rationals are shiny and crystalline. The reals are like wet, black smoke. -

Mysticism

But why bother defending this word? Is the word itself sacred? Is it the sort of thing that needs to be defended and kept pure? You're welcome to the word, but I don't think any of us get to control meaning like that in general. It's just a word. If the 'spiritual' is only a matter of the proper names, then the "spiritual" is just too small -- it becomes a politics that doesn't recognize itself as such. Learn the demons name and he will serve you, Rumpelstiltskin, etc.

As to resenting titles like "Hell is other people"...That's like blaming spiritual works for talking about sin and illusion. It's the same with the line you've quoted. The protagonist is not some simple "hero" of the book. It's like attributing "kill, kill, kill, kill" to Shakespeare himself and not to King Lear in a traumatic moment.

I'm not saying Sartre's perfect (I can find things to criticize) but he was a great theorist and poet of freedom, including the dark side of godlessness. He has some of the best one-liners around. Have you really read these "existentialists"? From here it looks like your coughing up the caricature. The Fall is a favorite. (Camus) There's the same kind of caricature of all the (more recently) imported religion with its exotic terminology: "It's all just a bunch of confused or plain superstitous hippies burning incense and sitting with their legs crossed." This kind of reductive/humiliating description is the symbolic warfare that we don't have to take seriously or get trapped in, but we tend to defensively "rewrite" and "make shallow" whatever threatens our contingent, "surface" attachments. (I'm not saying I never do this or that you are currently doing. I just study this sort of thing as various impositions of the Law I've been mentioning. ) -

MysticismAs I understand it, Sartre saw (the spirit of ) man as a futile passion to identity itself with something fixed and substantial, something unfree and therefore not responsible for itself. I relate this to the "seeing of a structure" (the game of the "Law" or the "Truth") that "Christ" was the "end" of. To see the nothingness is to annihilate one's chains with benevolent but impious laughter, at least in the retreat to one's spiritual imagination if not always in the thick of life. But this is just some guy's interpretation and synthesis of his favorite texts in the largely emotional and sensual context of his experience.

-

MysticismWe can't leave out this. I'd call it mystical, or mystical enough, but that's secondary. And this is why "sensation and emotion" are important to me. "Sensation" points at incarnation. "Emotion" makes any of this worth talking about or noticing in the first place.

Perhaps because explanation deals with finite essences in a system, and this "existence" precedes or is other than essence. But this precedence of existence to essence is also understood in another way when it comes to the natureless nature of man, a "hole" in being. Bad faith touches closely upon idolatry. The self wants to fix its identity in a solid object, to flee from its nothingness and freedom. Beautiful stuff.But I wanted to fix the absolute character of this absurdity. A movement, an event in the tiny colored world of men is only relatively absurd — in relation to the accompanying circumstances. A madman's ravings, for example, are absurd in relation to the situation in which he is, but not in relation to his own delirium. But a little while ago I made an experiment with the absolute or the absurd. This root — there was nothing in relation to which it was absurd. How can I pin it down with words? Absurd: in relation to the stones, the tufts of yellow grass, the dry mud, the tree, the sky, the green benches. Absurd, irreducible; nothing — not even a profound, secret delirium of nature could explain it. Obviously I did not know everything, I had not seen the seeds sprout, or the tree grow. But faced with this great wrinkled paw, neither ignorance nor knowledge was important: the world of explanations and reasons is not the world of existence. A circle is not absurd, it is clearly explained by the rotation of the segment of a straight line around one of its extremities. But neither does a circle exist. This root, in contrast, existed in such a way that I could not explain it. Knotty, inert, nameless, it fascinated me, filled my eyes, brought me back unceasingly to its own existence. In vain I repeated, "This is a root" — it didn't take hold any more. I saw clearly that you could not pass from its function as a root, as a suction pump, to that, to that hard and thick skin of a sea lion, to this oily, callous; stubborn look. The function explained nothing: it allowed you to understand in general what a root was, but not at all that one there. That root with its color, shape, its congealed movement, was beneath all explanation. — Sartre -

Mysticism

We can (among so many other options) envision God as the totality that is just radically there and Christ as a conceptually elaborated "primordial image" that allows us to feel at home in this otherwise alien God ('who' includes children with cancer, genocide,rape, our deaths, etc.).It took my breath away. Never, up until these last few days, had I suspected the meaning of "existence." I was like the others, like the ones walking along the seashore, wearing their spring clothes. I said, like them, "The sea is green; that white speck up there is a seagull," but I didn't feel that it existed or that the seagull was an "existing seagull"; usually existence conceals itself. It is there, around us, in us, it is us, you can't say two words without mentioning it, but you can never touch it. When I believed I was thinking about it, I was thinking nothing, my head was empty, or there was just one word in my head, the word "being." Or else I was thinking — how can I put it? I was thinking of properties. I was telling myself that the sea belonged to the class of green objects, or that green was one of the qualities of the sea. Even when I looked at things, I was miles from dreaming that they existed: they looked like scenery to me. I picked them up in my hands, they served me as tools, I foresaw their resistance. But that all happened on the surface. If anyone had asked me what existence was, I would have answered in good faith, that it was nothing, simply an empty form added to things from the outside, without changing any thing in their nature. And then all at once, there it was, clear as day: existence had suddenly unveiled itself. It had lost the harmless look of an abstract category: it was the dough out of which things were made, this root was kneaded into existence. Or rather the root, the park gates, the bench, the patches of grass, all that had vanished: the diversity of things, their indi viduality, were only an appearance, a veneer. This veneer had melted, leaving soft, monstrous lumps, in disorder — naked, with a frightful and obscene nakedness. — Sartre -

Mysticism

But are you so sure that you understand what I've been saying? Do you perceive me as someone who lives in the "normal" way, even as I share a passionate image of total freedom, the nothingness of all "spiritual" law exterior to and alienated from the self as a joyful, creative, incarnate "nothingness" that recognizes itself as such? I eschew all this talk of the hidden and the difficult and some authoritative truth or essence or knowledge of mysticism, for instance, though I recognize that an attachment to the hidden and the difficult and the authoritative is in fact the primary difficultly. In symbols now: bound by our desire to bind we nail him up, the blasphemous pervert, along with the freest center of our selves. I mean this is just the vision, a slice of the heresy as I've made sense of it. I'm still just a guy with a life and a wife and a job. It's a beautiful story or clump of ideas. But it resonates in my guts and lights up my heart. -

Mysticism

But surely you see that the "Being" of our lives is largely conception, emotion, sensation. If we are talking about states that are radically other than life as we know it, rather than a superior intensity of feeling and clarity of thought, then it sounds to me like the same old impossible object, the secret that yet is not a secret (since it's "unthinkable"), a fetishized empty negation.

Don't get me wrong. I see the allure of this "Being." I've stood before the That-Which-Is in shock and wonder. It is, and it is beneath all explanation. Sartre treated this well in Nausea. This is some of the "mysticism" I found in the TLP.

As far as symbols go, I mean numinous images and concepts. Most important by far, in my view, is the conceptually elaborated image of personified virtue. As I see it, this very conversation is driven on both sides by the energy of our differing images of the "ought to be" or the "ego-ideal." We feel pride or narcissistic pleasure as we identity ourselves with this image (live up to it) and shame or guilt as we perceive a gap between our actual and ideal selves. But the (passionate conceptual) images shape our lives that simultaneously shape the images. We tend to project our own notion of virtue as a universal value. "This is the way. This is the truth. This is the law. " But we can "intellectually" unveil this "nothingness" and the contingency and artificiality of all such law. The reason we don't, in my view, is because we want to "bring the Law" or "the Truth" or "the Method" and control or limit the spirits of others. We identify with these "alienations" or "finite/constrained" gods/myths. So the image of radical freedom is a threat to the ego whose escape from time and death is "tied up" in them. What he or she thinks is his or her best self is not taken seriously (as an absolute value) by the heretic who insists on a notion of the complete transcendence of everything pious, solemn, dutiful, sacred. This notion, "Christ" as the end of the law, is also the "Devil." This is just the end of the "ideal" law, not of laws in the world. Life goes on. Politics goes on (which is what every thing less than total freedom looks like ultimately). But to get stuck there, and to put the center of one's religion there, is, in my experience less satisfying. -

Mysticism

I won't say that others don't have wordless raptures. I won't pretend to believe in "round squares," though. I've had some "peak" experiences that I associate with symbols elaborated conceptually, lit, in theory, by primordial images. They are treasures that make my life better ---without, however, obliterating the need to struggle in this world and eventually die a personal death. They just light the world up and make it easier to love life (which includes my death).As regards what can and can't be known - an awful lot depends on what you mean by 'known'. Quite often mystical and gnostic understanding is grounded in trance or rapture - the suspension of discursive thought. So what can be 'known' in such states is nothing like we call 'empiricial truth'. That is why it resorts to symbolism to communicate those ideas. Deep and difficult questions of interpretation in all that, would take volumes to spell out. — Wayfarer

I don't know where Being came from. I don't think an answer could even make sense. All such answers seem to be necessarily mystifications. It's not so much that I idolize the rational but rather a matter of authenticity. If I don't have a clear and distinct idea, I don't want to pretend to myself otherwise. I'm not saying this about you, but it's reasonable to hypothesize that some of these "round squares" are themselves just abstract "irrational" myths, resonating as promises. Nothingness, for instance, is beautiful. I remember Sartre's Being and Nothingness on the shelf at a bookstore when I was a teen. What kind of book was this? What words were more beautiful? Negation, generality, transcendence of everything particular toward that which is most universal and eternal. Indeed, that's the genius in the total anarchy of the concept of Christ 'm attached to. All finite systems that want to dominate are set aside, at least for this divine man of the human imagination, elaborated conceptually in terms of iconoclasm's journey toward "at-home-ness."

Is this first-person report "mysticism"? It doesn't matter. I do like staying close to conversation and away from "mystification." If the symbols work (to some degree) irrationally, I call it emotion or feeling. Why not? Feeling is nakedly the source of value. Concepts are here in our dialogue.

If others report or expect something more, that's OK with me. -

Jesus Christ's Resurrection History or Fiction?For me the Gospels are a profound "wisdom writing." Whether or not they have any truth (and I certainly don't believe in an actual resurrection) is, for me, mostly beside the point. So what we have is a just a strange set of texts that we can pan for gold in.

-

MysticismSo realising emptiness is not actually itself a matter of feeling or conceptualisation. It is more a matter of understanding how the processes, the 'five heaps', give rise to our sense of ourselves, how together they constitute the sense of 'this is me, this is mine'. So through meditative absorption, dhyana, one penetrates the 'chain of dependent origination' and in that sense 'goes beyond' or 'sees through' the illusion of separate existence. — Wayfarer

You mention "understanding," which I associate with the conceptual. There's a conceptual "seeing through" of separate existence in Hegel and an emotional or felt "seeing" through of human separateness in Schopenhauer and in Schrodinger above. "Realizing emptiness" is something I associate with "all is vanity / everything is empty" in Ecclesiastes, which I think can be interpreted as the bonfire of the vanities or idols or masks/identifications of the ego. I like all of these themes very much, but I don't see how you can explain a non-conceptual revelation that isn't feeling or sensation. You can (seems to me) only paste more words on an empty negation, but as soon as you get metaphorical, you're in the realm of myth and concept.Now you might ask, is there anything beyond 'feeing and sensation'. The technical answer is: there is not anything 'beyond' it, but there is 'stopping'. 'Stopping' is the cessation of the activities of the skandhas so as to see their 'empty nature' (śūnyatā) - hence why in Mahayana Buddhism, the aim of the practice is described as 'realising emptiness'. — Wayfarer

It sounds like you are talking about stopping thinking in order to understand ("see") something about thinking. For me, this does not compute. But I obviously think that thinking about thinking can lead to a perception of "nothingness" or the emptiness of masks. However, we are attached to these masks or illusions, so that's where (in my view) desire enters the picture. For me the illusions are impossible hopes, inconsistent conceptions.

I think Sophia is female for reason. The phallus can be interpreted symbolically as a dogmatic assertion, law, or tradition and therefore as an "alienated" crystallization of the self's virtue outside of and above the bodily self in the world. Sophia is beyond or before such alienation.Love stories, however inadequate as theories of love, are nonetheless stories, logoi, items that admit of analysis. But because they are manifestations of our loves, not mere cool bits of theorizing, we—our deepest feelings—are invested in them. They are therefore tailor-made, in one way at least, to satisfy the Socratic sincerity condition, the demand that you say what you believe (Crito 49c11-d2, Protagoras 331c4-d1). Under the cool gaze of the elenctic eye, they are tested for consistency with other beliefs that lie just outside love’s controlling and often distorting ambit. Under such testing, a lover may be forced to say with Agathon, “I didn’t know what I was talking about in that story” (201b11–12). The love that expressed itself in his love story meets then another love: his rational desire for consistency and intelligibility; his desire to be able to tell and live a coherent story; his desire—to put it the other way around—not to be endlessly frustrated and conflicted, because he is repetitively trying to live out an incoherent love story. — stanford -

What is the subject matter of philosophy?

Good points. Both of these point together toward a self-consciously pursued ideal of staying within the limits of intelligibility. I remember being younger and having a hunch that a certain phrase was profound and then repeating it without being able to paraphrase it or really master it. So I was passing on a string of marks/noises that "felt" valuable without having a strong grip on them. But at some point I started holding myself to a higher standard. Even today, though, there may be an inescapable "fuzz" on philosophical/analogical thinking. But one is (or strives to be) always ready to paraphrase.If we're too self-confident, we might step beyond the limits of intelligibility and into the realm of obscurantism and bullshit. If we're too self-conscious, we submerge into a quasi-masturbatory skepticism feigning as wisdom. — darthbarracuda

Yes, pragmatism does tend to reject "quasi-masturbatory skepticism" as I understand it. Genuine inquiry is driven by genuine doubt. Differences that make no difference in life are set aside as word-games, terminological disputes. (Of course metaphysicians get attached to their favored terms, so there is some difference even here in emotional life. Hence the difference involved is implicit worldly or "trans-philosophical.") -

MysticismNon-conceptual is what 'the direct path' is about, and of course we can't 'make sense' of it, because to make sense of it, is to try and process it in the verbal-symbolic part of the mind. It takes doing. — Wayfarer

What can I say? I'm skeptical. It sounds like someone saying that they saw a round square in their dreams. Feeling and sensation can be nonconceptual. I get that. But I could ask you what you could possibly be thinking of here beyond feeling and sensation and by definition you couldn't tell me. And couldn't, in fact, know (at least not conceptually.) It looks like an empty negation. -

Mysticism

Thanks for jumping in. I like your mention of laughter. I'm guessing individual experiences vary, even if they are similar. I really can't know. I'm wondering (in my own case) whether there's much of a point in using the word. I have this conception/image of Christ that "shines" emotionally. I've also had a few "peak" experiences, but I can fit them under "concept/image" and emotion (love, joy, at-home-ness). -

MysticismThis is great, too. Not an authority, but definitely an influence.

Hence Christianity is first of all a particularistic, family, and

slavish reaction against the pagan universalism of the Citizen-Mas-

ters. But it is more than that. It also implies the idea of a synthesis

of the Particular and the Universal — that is, of Mastery and Slavery

too: the idea of Individuality — i.e., of that realization of universal

values and realities in and by the Particular and of that universal

recognition of the value of the Particular, which alone can give

Man Befriedigung, the supreme and definitive "Satisfaction."

...

The whole problem, now, is to realize the Christian idea of

Individuality. And the history of the Christian World is nothing

but the history of this realization.

Now, according to Hegel, one can realize the Christian an-

thropological ideal (which he accepts in full) only by "overcom-

ing" the Christian theology: Christian Man can really become what

he would like to be only by becoming a man without God — or,

if you will, a God-Man. He must realize in himself what at first

he thought was realized in his God. To be really Christian, he

himself must become Christ.

According to the Christian Religion, Individuality, the syn-

thesis of the Particular and the Universal, is effected only in and

by the Beyond, after man's death.

This conception is meaningful only if Man is presupposed to be

immortal. Now, according to Hegel, immortality is incompatible

with the very essence of human being and, consequently, with

Christian anthropology itself.

Therefore, the human ideal can be realized only if it is such that

it can be realized by a mortal Man who knows he is such. In other

words, the Christian synthesis must be effected not in the Beyond,

after death, but on earth, during man's life. And this means that

the transcendent Universal (God), who recognizes the Particular,

must be replaced by a Universal that is immanent in the World. — Kojeve -

MysticismWe also find the affirmation theme:

When all is said and done, the “method” of the Hegelian Scientist consists in having no method or way of thinking peculiar to his Science. The naive man, the vulgar scientist, even the pre-Hegelian philosopher — each in his way opposes himself to the Real and deforms it by opposing his own means of action and methods of thought to it. The Wise Man, on the contrary, is fully and definitively reconciled with everything that is: he entrusts himself without reserve to Being and opens himself entirely to the Real without resisting it. — Kojeve -

MysticismI don't take this authoritative (imagine that!) but it's beautiful and it certainly influenced me.

It is by following this “dialectical movement” of the Real that Knowledge is present at its own birth and contemplates its own evolution. And thus it finally attains its end, which is the adequate and complete understanding of itself — i.e., of the progressive revelation of the Real and of Being by Speech — of the Real and Being which engender, in and by their “dialectical movement,” the Speech that reveals them. And it is thus that a total revelation of real Being or an entirely revealed Totality (an “undivided Whole”) is finally constituted... — Kojeve -

Mysticism

Please, pick nits, share as you see fit.

I'm not terribly attached to the term "mysticism" ("heresy" might work), but I mentioned "concept" also. I highlighted "feeling" in that context because Punshh seemed to understand what I was getting at to be merely conceptual. I know that you know that Hegel presents God's self-revelation. I understand this in conceptual terms, but desire drives the system. I really can't make sense of non-conceptual revelation. -

Mysticism

Thank you for elaborating, first.There are two kinds of mysticism to point out here, there are the folk who are creatively embracing mysticism as a concept like yourself. I am with you as creativity is one of my great passions. Also there is mysticism as a spiritual way of life. — Punshhh

The words aren't that important, but I view the spiritual in terms of concept and feeling. I don't think it has to be unworldly. I realize that 'spirituality' is often associated with deities, but even here I have my 'deity.' So really it's a "theological" issue, isn't it? But the labels are secondary...As I say, I am with you in your approach, for me I have followed a Grail quest in the field of art and aesthetics(I have no formal training in philosophical aesthetics), creativity. Along with heroic efforts in the development of creative conceptual architecture. — Punshhh

That sounds fascinating. If you want to share anything, ... -

MysticismI was exposed to this theory about 20 years ago. Jung was a key figure for me, though I don't vouch for everything he said, of course. But this is the kind of thing I have in mind when I speak of "hero myths" at the foundations of philosophies.

The "Self" archetype is relevant here.Thus, while archetypes themselves may be conceived as a relative few innate nebulous forms, from these may arise innumerable images, symbols and patterns of behavior. While the emerging images and forms are apprehended consciously, the archetypes which inform them are elementary structures which are unconscious and impossible to apprehend.

Jung was fond of comparing the form of the archetype to the axial system of a crystal, which preforms the crystalline structure of the mother liquid, although it has no material existence of its own. — Wiki

In Jung's words, "the Self...embraces ego-consciousness, shadow, anima, and collective unconscious in indeterminable extension. As a totality, the self is a coincidentia oppositorum; it is therefore bright and dark and yet neither".[15] Alternatively, he stated that "the Self is the total, timeless man...who stands for the mutual integration of conscious and unconscious".[16] Jung recognized many dream images as representing the self, including a stone, the world tree, an elephant, and the Christ.[17] — Jung -

Mysticism

We probably have a different meaning in mind for the word "mysticism." There may indeed be heights that I never have and never will attain. But I write with a glowing image in my mind. It's an intellectually elaborated (dialectically evolved) "mask" on what I'd call a primordial image.

I can't speak for anyone else on this thread, but the mysticism that matters to me currently is something I understand as "just" or "only" concepts and images along with, most crucially, a feeling about or toward them. Now maybe I can fit everything you've mentioned into the "dialectic" above, but I won't pretend a false humility and pretend to be more of a seeker than a finder. I write from what feels like the end of a process. Life continues, of course, and I continue to learn. But I've been riding this enjoyable "system" or "worldview" in its basic form for quite a while now. I'm 40. I may open new doors as I move into a new phase of life, but I doubt I'll change much while I'm still ambitious and carving out a place in the world.Jung first used the term primordial images to refer to what he would later term "archetypes". Jung's idea of archetypes was based on Immanuel Kant's categories, Plato's Ideas, and Arthur Schopenhauer's prototypes.[3] For Jung, "the archetype is the introspectively recognizable form of a priori psychic orderedness".[4] "These images must be thought of as lacking in solid content, hence as unconscious. They only acquire solidity, influence, and eventual consciousness in the encounter with empirical facts." — wiki

What I can't be sure of is whether my experience is going to be valuable to others. -

Mysticism

No, I don't think so. People love their political self-righteousness if not their religious self-righteousness.But he's only stating the obvious - that is what everyone believes nowadays, question it and woe betide unto you. — Hoo

I didn't mean to imply otherwise. Yes, Trump is a perfect example...of all sorts of things..But his success demonstrates the limits of liberalism in the US. There really is a culture war, even if the progressives are slightly dominant. If you look into the dark side of the internet, you'll find incredible hate, incredible racism especially. But there are crazies on the left, too, dripping with resentment and revenge, equally conspiratorial in their worldview. To me this is all bad "concept religion." It narrows the heart. As a citizen, I may have to dirty my hands, come down to the business of life, cast a vote. But I still insist that any religion that isn't beyond politics is only more politics.Not if you actually do learn to be less ego-centred as a consequence. Of course there's the obvious trap of 'trying to be less egotistical' (like when Trump said that some reporter had no idea how humble he was.) But there really is a way of learning to be less reflexively self-centered through meditation. — Wayfarer -

Mysticism

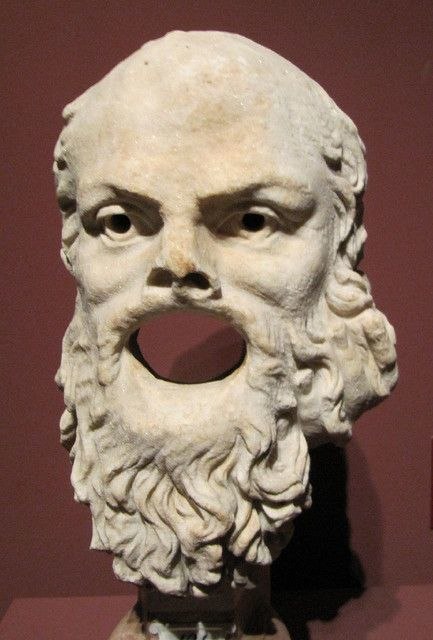

Exactly! Jesus is the Devil. That's why he had to be publicly executed. But of course I'm talking in symbols here. And you're right that there are all sorts of ways to build a Jesus from the texts. IMV, the pieces do not fit together. I don't know (or care much) if there was a historical Jesus. We know that there was a Socrates, but that too isn't central. If some mad genius dreamed up the whole thing, it might be no less valuable.Who was it who said 'do what you will shall be the whole of the law', again? — Wayfarer

I have to disagree with you about the ego issue, or make a distinction so that we can agree. Surely you'll agree that there is (at least) the hopeless game of priding one's self on having transcended the ego. I really wrestled intensely with this non-ego ideal, along with altruism as a duty. But (in my view) this is just an endless hall of mirrors, this very self-consciously trying to get beyond self-consciousness and self-importance and selfishness. That's why I take the Hegelian notion, instead, of the evolution of narcissism into something magnanimous, precisely because it eventually feels free and authentic. So a healthy egoism that is willing to face its mortality is also able to love authentically or un-self-consciously. Or just more able, because we are always able to slip (at least occasionally) into genuine play, genuine affection,in which self dissolves. It's like the lovers in the opening quote. That's how I read "already in Buddha" or "ordinary mind." But on the "Hegelian" route, anyway, narcissism learns to laugh at itself without condemning itself, since we'd have to curse the entire world for this omnipresent "sin." It's just a matter of elevating narcissism as we elevate lust. Or that's how I see my own journey (which continues even here and now...

Death is central here. Personal immortality is the last refuge of the ego. To accept death is to be forced to find one's best self in one's universal guts, the "primordial images" of early Jung, elaborated intellectually. The player dies, but the play continues. Plato's Forms might come in here. We participate in the Forms so that death loses much of its sting. But the proper name is a toe tag that must to the fire of life which is also the rose. -

Mysticism

I hear you, and I respect that. But it's my understanding that Christianity largely shaped the notion of the individual as sacred and free. Protestantism completed this. We work out our own optionally-mediated salvation. True, this freedom is a rope we can hang ourselves with. But there will always be a tension between freedom and security. There is death in sex as well as life, but that may be the point. I think Plato is right, though. We learn to seek higher pleasures, without ever ceasing, however, to find particular bodies desirable. Would I want to lose this desire? Not unless it was really screwing up my life. It lights up the world, bodily beauty. But I at least was never satisfied with it, except of course in the moment. There is indeed an intellectual love. I would never deny that. That's why I'm here. -

MysticismI think I can quote this, too, because Nietzsche was absolutely something of a mystic. His superman is an updated Christ image. (Or that's my reading.) In retrospect, I realize how much The Antichrist enriched my notion of Christ. Nietzsche, like Blake, is a Christian heretic.

That last sentence is ungenerous, but he's making the point that Stirner made about the connection of the external sacred and alienation. This gulf between man and some impossible object is precisely opposed to a feeling of at-home-ness in one's own flesh in one's own world. Here, now, this.With a little freedom in the use of words, one might actually call Jesus a “free spirit.” He cares nothing for what is established: the word killeth, whatever is established killeth. The idea of “life” as an experience, as he alone conceives it, stands opposed to his mind to every sort of word, formula, law, belief and dogma. He speaks only of inner things: “life” or “truth” or “light” is his word for the innermost—in his sight everything else, the whole of reality, all nature, even language, has significance only as sign, as allegory.—Here it is of paramount importance to be led into no error by the temptations lying in Christian, or rather ecclesiastical prejudices: such a symbolism par excellence stands outside all religion, all notions of worship, all history, all natural science, all worldly experience, all knowledge, all politics, all psychology, all books, all art—his “wisdom” is precisely a pure ignorance of all such things.

If I understand anything at all about this great symbolist, it is this: that he regarded only subjective realities as realities, as “truths” —that he saw everything else, everything natural, temporal, spatial and historical, merely as signs, as materials for parables. The concept of “the Son of God” does not connote a concrete person in history, an isolated and definite individual, but an “eternal” fact, a psychological symbol set free from the concept of time. The same thing is true, and in the highest sense, of the God of this typical symbolist, of the “kingdom of God,” and of the “sonship of God.” Nothing could be more un-Christian than the crude ecclesiastical notions of God as a person, of a “kingdom of God” that is to come, of a “kingdom of heaven” beyond, and of a “son of God” as the second person of the Trinity. All this—if I may be forgiven the phrase—is like thrusting one’s fist into the eye (and what an eye!) of the Gospels: a disrespect for symbols amounting to world-historical cynicism.... But it is nevertheless obvious enough what is meant by the symbols “Father” and “Son”—not, of course, to every one—: the word “Son” expresses entrance into the feeling that there is a general transformation of all things (beatitude), and “Father” expresses that feeling itself—the sensation of eternity and of perfection.

The “kingdom of heaven” is a state of the heart—not something to come “beyond the world” or “after death.” The whole idea of natural death is absent from the Gospels: death is not a bridge, not a passing; it is absent because it belongs to a quite different, a merely apparent world, useful only as a symbol. The “hour of death” is not a Christian idea—“hours,” time, the physical life and its crises have no existence for the bearer of “glad tidings.”... The “kingdom of God” is not something that men wait for: it had no yesterday and no day after tomorrow, it is not going to come at a “millennium”—it is an experience of the heart, it is everywhere and it is nowhere....

Jesus himself had done away with the very concept of “guilt,” he denied that there was any gulf fixed between God and man; he lived this unity between God and man, and that was precisely his “glad tidings”...

The old God, wholly “spirit,” wholly the high-priest, wholly perfect, is promenading his garden: he is bored and trying to kill time. Against boredom even gods struggle in vain.

What does he do? He creates man—man is entertaining.... But then he notices that man is also bored. God’s pity for the only form of distress that invades all paradises knows no bounds: so he forthwith creates other animals. God’s first mistake: to man these other animals were not entertaining—he sought dominion over them; he did not want to be an “animal” himself.—So God created woman. In the act he brought boredom to an end—and also many

other things! Woman was the second mistake of God.—“Woman, at bottom, is a serpent, Heva”—every priest knows that; “from woman comes every evil in the world”—every priest knows that, too. Ergo, she is also to blame for science.... It was through woman that man learned to taste of the tree of knowledge.

...

That grand passion which is at once the foundation and the power of a sceptic’s existence, and is both more enlightened and more despotic than he is himself, drafts the whole of his intellect into its service; it makes him unscrupulous; it gives him courage to employ unholy means; under certain circumstances it does not begrudge him even convictions. Conviction as a means: one may achieve a good deal by means of a conviction. A grand passion makes use of and uses up convictions; it does not yield to them—it knows itself to be sovereign.—On the contrary, the need of faith, of something unconditioned by yea or nay, of Carlylism, if I may be allowed the word, is a need of weakness. The man of faith, the “believer” of any sort, is necessarily a dependent man—such a man cannot posit himself as a goal, nor can he find goals within himself. The “believer” does not belong to himself; he can only be a means to an end; he must be used up; he needs some one to use him up. His instinct gives the highest honours to an ethic of self-effacement; he is prompted to embrace it by everything: his prudence, his experience, his vanity. Every sort of faith is in itself an evidence of self-effacement, of self-estrangement.... — Nietzsche -

MysticismThis might interest someone.

The time [in which Jesus lived] was politically so agitated that, as is said in the gospels, people thought they could not accuse the founder of Christianity more successfully than if they arraigned him for 'political intrigue', and yet the same gospels report that he was precisely the one who took the least part in these political doings. But why was he not a revolutionary, not a demagogue, as the Jews would gladly have seen him? [...] Because he expected no salvation from a change of conditions, and this whole business was indifferent to him. He was not a revolutionary, like Caesar, but an insurgent: not a state-overturner, but one who straightened himself up. [...] [Jesus] was not carrying on any liberal or political fight against the established authorities, but wanted to walk his own way, untroubled about, and undisturbed by, these authorities. [...] But, even though not a ringleader of popular mutiny, not a demagogue or revolutionary, he (and every one of the ancient Christians) was so much the more an insurgent who lifted himself above everything that seemed so sublime to the government and its opponents, and absolved himself from everything that they remained bound to [...]; precisely because he put from him the upsetting of the established, he was its deadly enemy and real annihilator...." — Stirner -

Mysticism

Ah, Wayfarer, come on, man. I don't live so wild these days. I'm trying to get a PhD in math over here. I like my pleasures serene these days. But why must the spiritual path be so anti-flesh? anti-drugs? anti-music? Or, basically, anti-Dionysian? Can we talk of the depths of the self and insist that this involves something cold and pure like crystalline intellect? Do think there is nothing to be learned on the "irrational" side of the personality? No darkness to look at with open eyes and assimilate?

No doubt, I'm coming from a Norman O. Brown kind of perspective. Lifedeath on one side and immortality/undeath/unlife on the other. Incarnation, the word became flesh. Jesus and Socrates were put to death by the pious. They were perverts or atheists or blasphemers. As I see it, there's a strain of mysticism that's too radical to be institutionalized. This strain is essentially subversive. It runs like wind through the nets of hierarchy and standardize dogma. "From now on, this is the way that religion shall proceed. The man with the robe or the hat will tell you all that you need to know." An institution that wants to involve itself in world affairs has no choice but to ossify. It's a bone for the beating of stubborn unbelievers --and heretics like Jesus. Let's not miss the center of the myth. The word made flesh was publicly executed. -

Instrumentality

I respect that. For me it was a pushing of that kind of cynicism further, into itself finally. If a thinker is locked in to the idea that happy people are deluded or shallow, then they've "gone blind" to a healthy hearted common-sense. They can't be superior if they compare themselves in terms of happiness, relationships, careers, because the "deluded" people have all that, and usually more of it.

"God" is too superstitious, so cosmic spiritual truth becomes God. But this truth can't claim to be useful. It can't be a tool. It might get tested in the profane world of the deluded. It wouldn't be holy or pure or superior enough. So it takes an esthetic form, and yet this is unstable, because no one wants to say "I'm superior because I think the world is gross." Well, a few puritans play that game, perhaps. So I try to point out this "cold, hard" truth as a fairly obvious tool in the hands of a spirit or personality that wants some damned status and recognition in this world. Don't we all? Till we get enough. It looks like a hell of a short cut. Words alone do the trick.

If I were to gripe about anti-natalism/pessimism, it would be that I've been living with the "death of God" or "death of absolute meaning" axiomatically for 15 years. It's the air I breath. What's new? It's actually a beautiful open space around all the non-absolute "meanings" that actually drive us when we don't have our wheels in the mud of the "shortcut" of the purely verbal solution. That is where the positive potentially lies in a perception of "instrumentality." At least that prepares the way for embracing all thinking as a technology. It prepares the leap of "well that's how life is, and I'm part of it as I think to oppose it." -

The STYLE of Being and Time (Joan Stambaugh's translation)

Well, that's pretty macho, Kevin (your "tough shit"). Sometimes, yes, it's worth the hassle. But the problem is always the opportunity cost of other books we could be reading, including secondary sources that aren't necessarily less valuable --unless one is invested in one of these asshole word-mongers as more than just another dude with a mind-blowing story that finally is the real Secret of man and the universe. I'm too old to play the fan-boy, so these famous f*ckers are going to justify themselves to me and not the other way around. That said, there's always some humility and suspension of disbelief and curiosity in opening one's self to a thinker. This humility only has real weight if one goes in with a sense of self-possession and of knowing the "essential" already. The other kind of "humility" is, in my mind, a juvenile quest for some master whose glamour one can buy in on. For instance, by tossing off keywords without being able to lucidly paraphrase a single thought of relevance to those not under the spell of the Name (I'm not aiming this at anyone in particular, just at ubiquitous intellectual vanity, which I sure as hell don't pretend to be free of). Ah, but maybe we can use some badly written book to enlarge the self more, learn a new poem, weave a more complex and beautiful synthesis. But, Jesus F. Christ, style matters. -

Instrumentality

I think we are tool-users in our blood, "meant" (or wired) to be happy and adapt. I think we agree there. I don't dispute at all your right to challenge Schop, either. That's what we're here for, not only to be "recognized" but also to hold our tools/personalities up to the fire. Even these positions that probably strike as both as unnecessarily "troubled" are, in my view, the better, more positive view struggling to be born. My hunch is that we should often push forward, make our "mistakes" exuberantly and have the guts to speak our "indulgent" thoughts and see what happens. If not here, where? -

Instrumentality

Maybe it's the contingency of the world he find absurd. It is absurd. "Why is there a here here?" I've never been convinced by metaphysical answers. But nausea is just the flip side of wonder. So really this "absurdity" is a feature rather than a defect...or can be seen that way... -

Mysticism

I like the radical simplicity, but must it be as Plotinus sees it? Maybe. For all I know, there are 777 varieties of profound or heightened experience. But I prefer "all beings are already Buddha" without the paradox. I can only read that line in terms of "creative play" or the selves that we are when we are "beyond good and evil" and lovingly absorbed in a person or a project. This is a good way to read Genesis, too. The tree of knowledge of good and evil obscures the tree of life. Of course we want extraordinary feeling, but here too I wouldn't rule out sex, drugs, and rock-n-roll. (I guess I'll represent the 'devil-worshiping' branch of mysticism around here. )But at the center of the mystical vision there has to be a radical simplicity. It is essentially the same vision as 'the One' of Plotinus, whereby the individual and individuated mind is thoroughly (re)absorbed into the single source of all manifest things. Of course it is indescribable, but one of the (many) paradoxes surrounding it, is that for those who realise it, it is also utterly obvious and something that has been obvious all along (cf. 'all beings are already Buddha'). — Wayfarer -

InstrumentalityDo you know Nausea?

There's some other stuff more directly about instrumentality, but that's a great passage on absurdity and contingency.All at once the veil is torn away, I have understood, I have seen.... The roots of the chestnut tree sank into the ground just beneath my bench. I couldn't remember it was a root anymore. Words had vanished and with them the meaning of things, the ways things are to be used, the feeble points of reference which men have traced on their surface.

...

Absurdity: another word. I struggle against words; beneath me there I touched the thing. But I wanted to fix the absolute character of this absurdity. A movement, an event in the tiny colored world of men is only relatively absurd — in relation to the accompanying circumstances. A madman's ravings, for example, are absurd in relation to the situation in which he is, but not in relation to his own delirium. But a little while ago I made an experiment with the absolute or the absurd. This root — there was nothing in relation to which it was absurd. How can I pin it down with words? Absurd: in relation to the stones, the tufts of yellow grass, the dry mud, the tree, the sky, the green benches. Absurd, irreducible; nothing — not even a profound, secret delirium of nature could explain it. Obviously I did not know everything, I had not seen the seeds sprout, or the tree grow. But faced with this great wrinkled paw, neither ignorance nor knowledge was important: the world of explanations and reasons is not the world of existence. A circle is not absurd, it is clearly explained by the rotation of the segment of a straight line around one of its extremities. But neither does a circle exist. This root, in contrast, existed in such a way that I could not explain it. Knotty, inert, nameless, it fascinated me, filled my eyes, brought me back unceasingly to its own existence. In vain I repeated, "This is a root" — it didn't take hold any more. I saw clearly that you could not pass from its function as a root, as a suction pump, to that, to that hard and thick skin of a sea lion, to this oily, callous; stubborn look. The function explained nothing: it allowed you to understand in general what a root was, but not at all that one there. That root with its color, shape, its congealed movement, was beneath all explanation.

...

I was there, motionless, paralyzed, plunged in a horrible ecstasy. But at the heart of this ecstasy, something new had just appeared; I understood the nausea, I possessed it. To tell the truth, I did not formulate my discoveries to myself. But I think it would be easy for me to put them in words now. The essential point is contingency. I mean that by definition existence is not [logical] necessity. To exist is simply ... to be there; existences appear, let themselves be encountered, but you can never deduce them. Some people, I think, have understood this. Only they tried to overcome this contingency by inventing a being that was necessary and self-caused. But no necessary being [i.e., God] can explain existence: contingency is not a delusion, an appearance which can be dissipated; it is the absolute, and, therefore, perfectly gratuitous. Everything is gratuitous, this park, this city, and myself.

...

I was no longer in Bouville; I was nowhere, I was floating. I was not surprised, I knew it was the World, the naked World revealing itself all at once, and I choked with rage at this gross absurd being. You couldn't even ask where all this came from, or how it was that a world existed, rather than nothingness. It didn't have any meaning, the world was present everywhere, before, behind. There had been nothing before it. Nothing. There had never been a moment in which it could not have existed. That was what bothered me; of course there was no reason for its existing, this flowing larva. But it was not possible for it not to exist. It was unthinkable: to imagine nothingness you had to be there already, in the midst of the World, eyes wide open and alive; nothingness was only an idea in my head, an existing idea floating in this immensity; this nothingness had not come before existence, it was an existence like any other and ap peared after many others. I shouted, What filth, what filth! And I shook myself to get rid of this sticky filth, but it held and there was so much, tons and tons of existence, endless. — Sarte

Hoo

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum