-

Is there an objective quality?

I think I am simply saying, if one wants to tell someone else “you are wrong” than one is operating from the standpoint that something is objective between them.

If you have the opinion that I am wrong, you also have the opinion there is something objective.

With regard to relativism, if the only basis you operate from to judge another person right or wrong is your own, subjective point of view, then you would be more consistent with your viewpoint to never see anyone as wrong. They would just be different, from their point of view, not yours.

Incoherence versus coherence is an agreed upon game, but then the agreement takes the place of objectivity. We don’t get to agree to do math and each say 2+2 equals all sorts of things. How math works becomes objective and is not subject to opinions about how to do it, if you want to play math.

They say ritual human sacrifice is good and beautiful.

You say it is not.

The relativist might say it’s culturally dependent and so it is both good and not good depending on who you ask (so neither good nor not good objectively speaking)

If there is nothing objective, then all opinions may seem different, but what else is there to say?

So if you want to have the opinion that someone else is wrong, you can’t have any opinion you want. -

How do you determine if your audience understood you?Are you sure you were teaching them addition and plus, not quaddition and quus? Or maybe it was laddition and luus? — Count Timothy von Icarus

Don’t these other ideas have to come after addition, if they don’t actually include the idea of addition anyway?

But ok.

But doesn’t this just raise a version of epistemological problems with understanding anything independent of our minds?

It is true, there is the line between the other one’s behavior/ words, and the understanding mind behind that behavior/words. We are many layers divided from each other and the thing-in-itself.

And really, is it disrespectful to presume we could understand such a thing as what another one understands?

But how do we seek to understand anything?

We seek evidence.

So the question becomes how could we elicit evidence of another’s understanding?

And this question becomes what is it we understand that we are seeking evidence of, in another?

We seek evidence of an understanding out there, that matches our own.

To seek this, we must first put our understanding into words to give the other one something to understand.

Words are the fulcrum in this whole inquiry.

They are my words first, telling the other person what I want them to understand. So now there is my understanding, and then there are my words.

Then the other person takes my words and understands something of them.

At that moment I can ask “do they understand me?”, and I can seek evidence of what it is they’ve understood from my words.

So now, if they can speak back to me different words than mine, but nevertheless draw for me the same idea that I am understanding, we’ve both provided evidence (words behaviors) that in themselves don’t match each other (different words/behaviors). But, if we understand each other, we nevertheless demonstrate the one same idea understood in those different words.

This draws a line distinguishing our words which are different from each other, from the one same idea those different words both now convey. If I can gather the same idea from the different words, I have strong evidence that the other person who said those different words understands me.

We have isolated our two understandings from the two different words and the behaviors exchanged, a now can show those two understanding correspond and are the same.

This os all another a long winded way of saying, tell them what you mean and ask them to show you they understand.

Let’s do this right now. The “How can I tell whether you understand me?” example test:

What I understand is a number. A certain quantity, if you will. To be more specific, one way of understanding this single number is as “equal to 3.3 + .7”. That is enough to give you the idea about which I am asking ‘how can I know whether anyone understands me?’

If you do understand, you might say my idea is the same as “one and one and one and one”, or maybe “117, but after taking away 113 from it”. This idea helps organize a great golf outing, or a game of horseshoes.

I can tell whether you understand something of this idea I’ve spoken about, if you can say something I haven’t said about it.

And if you can, how does it not mean that we each now can tell we both understand each other?

The words are the fulcrum between two understanding minds, and what they each understand. Words are the best evidence we can gather to most intimately know what another understands. I need words for you to understand me, and can elicit words from you to see if you understand what I understand. And the test of the same understanding requires different words from each in order to strengthen the evidence of the same idea in each.

I’m sure this example is not perfect, and I’m sure it does not prove either of us understand anything, let alone understand each other’s mind. But if “4” crossed your mind, during the test, I bet you could explain to me what I am trying to say here, maybe show not only that you understand it, but how it is flawed, and how we might still not know each other at all.

But I still say we understand each other and so understand what each other understands.

In fact, IMO, it is precisely because people can speak their minds, and that people can admit words capture their own minds, that we can know people better than we can know anything else.

We can’t understand the-thing-in-itself; there is the brightlne wall never to be crossed. But people, can seek to know the other person’s understanding-in-itself in a different way, unlike people seek to understand any other type of thing. Because the other can make themselves vulnerable, sort of let down the wall between two things in themselves, and reveal themselves seeking to be completely known, to make clear in words and by questioning confirming, what is one’s understanding and whether the other one is listening. -

How do you determine if your audience understood you?They’re your friends, why don’t you ask them. — T Clark

I should have said that. -

How do you determine if your audience understood you?How would you go about determining who understood you? What would you take as evidence that some sort of meeting of the minds had taken place? Or do you think there is any such thing as meeting of the minds? — frank

Perhaps I don’t understand the question, but it seems like everyone is skipping over the obvious.

We have to assume everyone can understand at all, and each understands something in particular, to then ask how can we know the other one understands us.

And this raises a curious feature of the question. You asked, “how can we know if someone else understands you?” If you make this particular and ask “how can we know someone else understands the particular idea I just spoke about?” In such case, the same information is learned if you simply ask the other person “Do you understand the particular idea?” Or better, we both ask ourselves together “what idea do we both now understand?”

How can I know if another one understands me, is the same question as how can I know if the other one understands it (the idea in me), or do you understand the idea, or what do we both now purport to understand.

But maybe you are asking how to read people’s body language and prove their honesty?

Because the obvious answer is you could ask them to show they understand. They could repeat the idea you want to see that they understand, in their own words. Or provide their own example that shows they get it.

I could teach them how to add, ask them what the answer is to some new test cases and if they get the right answers, they show me they understand addition like I understand it. I know they get my idea of addition because they can add any new numbers up just like I would.

Or they might extend my idea showing me they understand it even better than me. This is real proof of understanding, when they not only display the same idea in their own unique words, but they show me something I hadn’t thought of about this idea that is new, but something only someone who understood it would come up with.

Like I teach you addition, you show me how you understand it, but also now see you can flip this process called additional and do subtraction. Wow, a genius at understanding what I thought was my idea. I learn something new from you the one who I was wondering if you understood me.

Does my answer above show that I understand your question? At least good enough to fire off an answer in the ball park you are playing in?

I will add that each one of us has at least a slightly, if not vastly, different vantage point. We probably rarely see things precisely eye to eye. But then, even when we are alone, we probably think the things we understand are one way and they may actually be another just as well. So actually, when it comes to all of the things we can understand, because we can ask other people to express their minds in words, two minds understanding the same idea may be the closest thing to actual knowledge of something we truly ever get. I mean, a rock can’t tell us we are correct in calling it hollow in the middle. We can’t confirm we understand a rock or the atom or my dog’s emotional state, as immediately as we can understand another person’s mind by simply asking them. -

Is there an objective quality?"Opinions are plural; anyone can have one. But if your opinion happens to be that there is nothing beyond opinions, no truth, no fact of the matter, then it is meaningless for you to also tell me I am wrong about something." — J

Yes, more precise is better. But less snappy.

Maybe, you can have any opinion you want, but if one has the two opinions “you can have any opinion you want” and “your opinion is wrong” then you are contradicting yourself.

In the context of “is there objective quality” or “is there truth, good and beauty prior to recognition as such in the eye of the beholder”, the point of the statement you clarified for me above is that, if we don’t think there is anything objective or non-subjective to beauty and truth and good, then the words beauty and truth and good are meaningless.

Maybe there is nothing good, true or beautiful, and we all fumble around when using these terms. But if you think there is nothing objective about them, we will always, only fumble. And what is the point of fumbling at each other in a debate/discussion? Power struggles for competition’s sake? But that’s a zero sum loss of the war (game) for sake of some stupid battle between we fumblers. It would be like two smart people trying to win at tic tac toe. Pointless as long as each has mastered the game.

In other words, if you can convince someone that there is nothing objective and that context will always undermine the prior and overwhelm the conclusion, all is provisional stipulation to later be revised and discarded, then really, why bother asserting anything?

I don’t believe anyone really believes these things - that nothing is ever fixed and there is no opinion that must be absolutely held by all opinion holders. That’s why we continue to assert things. Pursuit of truth, good and beauty.

Even saying “there is no one truth for all” is a truth for all. The only way to truly have the opinion “there is no truth” is to stop speaking about it. You don’t tell someone “you can’t say there is truth”. If someone is saying “there is one truth for all” and you disagree, and you think that there is no such thing, you simply cannot speak without contradicting yourself.

Cratylus, Heraclitus’ pupil, was known to wiggle his finger in response to questions about these things. That was, in my opinion, a more honest form of response based on the belief that all is flux and there is no objective quality. -

Is there an objective quality?

Perhaps we can say truth is not invented by humans, but neither does it exist in some Platonic realm, independent of all interpretive conditions. Instead truths become available within human discourse—not arbitrarily, not as illusions, but as intelligible articulations of a world we are always already in relation with.

— Banno

That’s sharper than my view and nicely put. — Tom Storm

That is well put.

But there is a bit of tension between these two terms:

“truth is not invented by humans” and

“truths become available within human discourse”

They may contradict each other a bit.

And there may be another contradiction by saying “not arbitrarily…”.

I think the precise point we are debating is whether quality is arbitrary or not. I am saying all is NOT arbitrary. If you are saying all is not arbitrary (as in, “…not arbitrarily”) then we agree. You should then agree that:

“You can have any opinion you want. But if you are trying to tell me I’m wrong, then you can’t have any opinion you want.”

All I’m saying is if you want to have the opinion “all is arbitrary” you can. But if you want to correct me, about anything, you are actually saying something is not arbitrary, or you are lying, or contradicting yourself.

But regardless, I think this part is all you need to sum up your main point:

truths become available within human discourse—not arbitrarily, not as illusions, butas intelligible articulations of a world we are always already in relation with. — Banno

I would restate this as, truths are moving targets (ie. becoming available in discourse) articulating things that are moving (ie. of a world of relations).

I agree that articulating truth is a pickle. We may rarely hit the mark.

But it is not even possible or worth attempting if there is no truth.

What I’m saying is, the above would be better stated without using the word truth as in “opinions become available within human discourse—not arbitrarily, not as illusions, butas intelligible articulations of a world we are always already in relation with.”

This is fine. That may be the human condition.

But then there is no truth.

And then there is no error, or correction.

And no reason to debate our opinions.

… address the ‘you can’t have values if there’s no external validation of the good’

— Tom Storm

And the question becomes, external to what? If the world is always, and already, in a context and a language, then there is nothing "external" to the interpretation.

Which brings us back, I think, to how it is that Tim can understand the divine, without thereby interpreting it.

So for Tim the world is already divided up. Whereas for me the division is something we do, and re-do, as our understanding progresses. — Banno

If there is nothing external to the interpretation, than what is it an interpretation of?

This has become a chicken and egg discussion about a statement and the truth of a statement. Or maybe a statement and what the statement is truly about.)

I agree the division is something we do. This is to give an opinion.

But then we can debate and determine something else about this opinion - does it reflect something true? Is it an opinion of something anyone who could give opinions would (or should) indeed hold because it is also there in the world, truly?

We divided the morning from the evening, and even though the light was similar at both times, one was getting brighter and the other was getting darker. So maybe the opinion that the morning is different than the evening is false because the light was similar at both times (and this division was arbitrary), or maybe it is true because of other divisions we can point out such as brightening or darkening. These divisions and interpretations are OF not merely our words and language, but of the world, not arbitrarily divided. -

Is there an objective quality?You can have any opinion you want. But if you are trying to tell me I’m wrong, then you can’t have any opinion you want.

— Fire Ologist

Do you mean wrong as in mistaken about something, or wrong as in morally wrong? Or both? — J

I mean wrong in any sense or application.

There is your opinion.

There is my opinion.

We can leave it at that.

But if we want to debate which opinion is correct, we have to go after some third thing between us that matches one of our opinions.

That third thing would be the prior, or the objective, or the truth. With a capital T as some like to call it.

That’s my opinion. -

Beyond the PaleI have already conditioned these out of my example. — AmadeusD

Would you do me a favor and show me your example and how you conditioned these out of it? -

Is there an objective quality?

When I respond to your view here, am I really engaging in a rational pursuit of truth, or am I simply performing a kind of power move, attempting to universalise my own subjective stance? — Tom Storm

That deserves its own thread. It’s the nut of so many discussions.

If one answers that giving an opinion is “performing a kind of power move, making universal that which is really subjective” aren’t those who hold such a view basically lying when they offer their opinions?

Here is an opinion, for example: “to judge art as ‘good’ is a subjective view and is not about the piece of art in itself”.

This is a universal statement about what art and what good art is.

If I offer this opinion as part of an argument for the sake of a rational pursuit of truth, than whether this opinion is either true or false will require supporting argument to prove its merit. But I can honestly mean it. This can be an honest opinion about the truth of art as part of an honest debate.

But since the opinion itself is a universal statement, if I believe universal opinions cannot be true (or are not real, or are some sort of categorical mistake of language), because all such statements are really “attempts” and “power moves,” then I am lying to you about what I actually think when I tell you what I think art is. If I think “art is only subjective” is universally true, then I am “attempting” to universalize my own subjective stance and make a power move; I am not really saying anything true about art, or more plainly, I am lying to you.

Bottom line, as is so often the case, where all is relative and subjective, there can be nothing to honestly discuss about it. So if you are bothering to speak, you must see something objective we both would have to say, or you are lying to me in order to over power me.

How else can I be corrected but by something prior to your opinion that can be prior to mine? Your view may over power my view, but it can’t correct error if it is merely your powerful view.

If one honestly thinks judgements are simply subjective then you should be agreeing with the Count about Brave New World having no defects as all such orientations are like all other human endeavors - inventions from nothing, purely conventional, in a world where the practical can be re-trained according to any subsequent and new power move.

Or if you disagree with Hitler, on principle, you might be “engaging in a rational pursuit of truth.” But if you disagree with Hitler absent any objective, prior principles or belief in universal truths, you might be “simply performing a kind of power move, attempting to universalize your own subjective stance.” In which case you said nothing about Hitler anymore, but merely became the over-powering dictator.

Last point, when people who think all is subjective and relative agree with each other, there is no real point in debating, but they might enjoy themselves making small clarifications (which would really be attempts at universalizing as they win power struggles). But when people who think all is subjective and relative truly disagree with someone, their best argument is really “you are stupid and you should just shut up” because otherwise they have to pretend (attempt) to engage in rational argument for the pursuit of truth, which would be lying.

Right?

You can have any opinion you want. But if you are trying to tell me I’m wrong, then you can’t have any opinion you want. -

Are moral systems always futile?Do you see post-modernism as inherently relativistic, morally? I loved the postmodern art I was encountering, Angela Carter, the Simpsons, the musician Beck, but I started to feel queasy as I encountered the moral relativism - I still remember clearly a prof telling us that we had no right to judge the practice of female genital mutilation - and I see that moral relativism everywhere today. — Jeremy Murray

Hey Jeremy,

I hope you don’t mind me hijacking your questions for Count.

I think there is a narrow but unique contribution to be gained from post-modernism. I might say I see it as more of a method, than it is actual content. It’s like a metaphysical spell-checker.

Content, which itself is too static, is secondary, asserted only so that one can look sideways at content, while focused more on itself in the looking, at the same time content is asserted. All is therefore, ironic. Or all is story-telling with the post-modern.

There certainly is a time and place for the attitude and process that post-modernism typifies. It produces a unique type of skepticism towards institution, and an ability to disagree with others and to deconstruct the content others might supply. This can be the right course of action to take, given the dubious content errant human beings often supply; but postmodernism is itself a type of subversion, and so it can jeopardize a maturity towards true wisdom.

And artists are always the best at working the medium (creating the best content for irony’s sake), so if there is a lasting impact to post-modernist thought, I suspect it will be from the arts, and not from philosophy or the humanities. Really good pop music since the sixties is truly something that will always engage as much as it repels.

Relation and process are the most positive terms to make something out of postmodernist academia. But as a process of deconstruction and relation without relata to fix, this content remains blurred and formless, and accidental.

But really, post-modernism has no inherent content. Even existentialism had the human condition and history and a fading sense of pride as its focus, which is why Nietzsche and Dostoyevsky and Goethe and Camus and Satre are so much more compelling to read than Wittgenstein, Derrida, Foucault and anyone since, who tried to run with this spirit of meaningless meaning making. (They turn truth and metaphysics into nonsense, but for the sake of turning emotion and will into metaphysics and truth.)

But with all of that said, post-modernism is relativistic, particularly when it comes to morality and ethics (and by application, politics). Which is ironic, because even post-modernists resist being called a relativists, and as such, have come up with some of the most rigid, oppressive moral codes and dogmatic systems (DEI/political correctness, race/women/sexuality/gender dogma, climate change social virtue, anything conservative and capitalist and republican and religious is evil/facist, etc.). The post-modern is so relativist, they can be or value anything, including their own total self-contradiction, and with straight face be the right kind of absolute dogmatist when the mood suits them.

So yes, morally, the spirit of the post modern age is relativistic at base. We now can be experts at a million new specialties, and experiment constantly in our fields, and no one who isn’t a new expert can tell us we are wrong (and the experts are at their best when they disagree with each other), as long as what we are doing is over-throwing something that existed yesterday. Disruption for disruption sake is the virtue. We can ask questions of our intentions and biases later, or just move on and ignore the smoldering mess that is always some old, white, rich oppressors fault anyway. We can hide in scientism, shrug off that which is not falsifiable, and silence those who just won’t understand the post-modern. The adolescents have tied up their parents and taken over the high schools. You can literally see it on most college campuses for the past 50 years.

Next time I’ll tell you what I really think! But seriously, it’s not all bad if you look at postmodernism the way postmodernists look at everything else. As self-reflection, it is a type of humility. The existentialists should have had the last word; the postmodernists just kept talking anyway.

how important to you are your religious / spiritual beliefs in terms of the philosophy you are drawn to?

I consider myself a fairly staunch atheist. — Jeremy Murray

You are an interesting and honest poster. I think I’ve told you I believe in God and practice Catholicism. I think your attitude towards the theist exemplifies my attitude toward the atheist; there is plenty of philosophy and science and practicality and wisdom to share in addition to or just without mentioning God or religion.

Religion and God are important to me, and it is the nature of religion that it is something that can make itself immediately present in any discussion. It can be all-pervasive. But just as immediately as it can be brought out, it can be kept separate and left for the believers and theologians to discuss in their free time.

To really answer your question, I see it like this.

If I talk about my children, I can discuss their biology, or reduce that to chemistry and physics, or go from biology to something more specifically human and universal like anthropology or human psychology/self-reflective consciousness…But would any of that really ever account for what I could say if I as their father was telling you about my kids that I love? Does the interesting information about brain states really say the same thing as me telling a story showing why I love my kids? Can we learn more about love from me showing you, or from a neuro-scientist? I mean, even if in the end, love is just a feeling (which I actually think is reductive absurdity), isn’t a story told in love always more interesting and more revealing than whatever the brain state/behavior facts/functionalist emergence story could possibly be?

So to me, talking about God like a philosopher talks is like talking about my own kids like a biologist talks. I can do it, but there is so much more interesting biology than my kids can demonstrate, and there is so much more interesting theology than the God of philosophy can demonstrate.

But all of that said, it is hard, at least for me, to find a common morality without God.

We need some sort of ideal or target to strive towards - some fixed notion of good or essential virtue - to really sink our teeth into morality. It may not have to be a God or a religion, but something necessarily good needs to be discovered to even begin constructing a morality. We both (or all) need to bite some apple to discover we know something of good and bad in themselves.

Maybe we make it up first (I doubt we will ever finish making it up ourselves), but if good and bad is not fixed between us, sitting there as if growing on a tree, morality never gets off the ground and/or it gets devoured by relativism.

Religious institution and the word of God himself make it easier for many to accept that there is a true good we either seek or fail to have. God grounds moral authority and gives a confidence in righteousness and punishment/correction.

But things like “we hold these truths to be self-evident” and “act as if whatever you do it could be made into a universal law that all will do” and “treat no person as a means”, which are all secular, could easily be from a religion (and basically are). The point being, these tenets aren’t true or good just because I am wonderful enough to understand them and agree with them - they are things we all can learn to one day take for granted, like adults who accept their duty willingly. And more importantly for this thread, in my humble experience, without something fixed and permanent like these, morality is a meaningless game.

When the moral goal post of can be moved, there may as well be no goal post.

Unfortunately, it’s no fun breaking the rules when there really aren’t any rules. So we keep reinventing the boogeyman and a corresponding brave overcoming.

Having had more than my share of bad luck, the problem of evil (and why me?) is too large an obstacle, despite how appealing I find the idea of belief. I think this best explains my interest in virtue ethics. But we both seem drawn to similar ideas?

Regardless, I like theology. — Jeremy Murray

There are saints who had no idea where to really find God, or what or who God really is. Mother Teresa wrote privately about her long- lived feeling of utter loneliness and abandonment when she sought God.

With your obvious interest in the truth and what is good, you may be a saint as much as anyone, and if you don’t watch out God may show up yet.

At least that is my hope for all of us! -

Free Speech - Absolutist VS Restrictive? (Poll included)

Huh? Just because I can do 50 other things doesn’t mean I am not reacting right now to your words.

What does “can you” have to do with it?

Cause and effect can have intervening causes.

One of the intervening causes may be my consent and choices. But I’m responding to NOS4A2 in a way that rationally relates to what you asked me. So you are involved in these words I’m typing right now.

To get back on point, no government should regulate whatever I am saying now and whatever you said or might say in response to me.

But if you and I were conspiring to commit murder, just flinging murderous thoughts and plans at each other, and one of us takes one affirmative step according to those plans, like buying guns or something, then both of us could be charged with conspiracy to commit murder and potentially jailed, not for buying the guns, but for the words we shared as the reason for buying the guns.

That would be government regulating speech but because of its consequences, not because of its content.

Etc., etc. -

Free Speech - Absolutist VS Restrictive? (Poll included)So how can you move a human being with words? — NOS4A2

Ask them a question, like you just did to me. -

Free Speech - Absolutist VS Restrictive? (Poll included)Use your words and cause me to take specific actions. — NOS4A2

NOS4A2, post something, anything, anywhere on TPF.

You are my slave now. -

Free Speech - Absolutist VS Restrictive? (Poll included)and pressures everyone into silence/agreement — MrLiminal

I certainly see what you are saying. I just think there is a sort of categorical, paradigmatic difference between a government that has to respect free speech, and a government that regulates speech. There will always be loud majorities who bully - in a free state, there is recourse, but in a totalitarian state, there is none. -

Free Speech - Absolutist VS Restrictive? (Poll included)Full free speech will end up with the majority shouting down the minority. Restricted free speech gives the government power — MrLiminal

Can’t we, in a free society always just ignore the majority if we want? It may take courage, but the majority shouting down the minority is still immensely better than a government silencing the individual and forcing him to do something he doesn’t want to do.

Screw the majority! Be bold. And screw the government too. In a truly totalitarian state, you can’t say “screw the government” or really, you can only say what the government and the majority it allows to exist says. Majority and government become a monopoly on speech under a government that regulates speech.

The media sucks. The majority is really loud and intrusive. Those are not the same issue as the government regulating speech. -

Is there an objective quality?How about, the ability to engage the beholder’s mind (teaching them, making them reconsider something, saying something better than ever experienced before), and/or heart (making them feel emotion, experience physical connection). The more engagement the better the art.

-

Free Speech - Absolutist VS Restrictive? (Poll included)Not in a government composed of two political parties where the political parties do not speak on behalf of the state, but on behalf of their party. When the party regulates the speech of their constituents by only providing partial information, your freedom to information is restricted and therefore your ideas would be restricted which effectively limits your speech. The party also regulates speech by ostracizing any party member that questions the party's claims. This is how political parties become a political construct of group-think. — Harry Hindu

You are just talking about how hard it is to be good voter and to determine who there is to vote for, and be a free citizen, and avail yourself of your freedom of speech, to dig deep and make the above observations and stay as free from undue influence as you can. -

What is faithDo you think a follower’s faith in a guru is of the same nature as a patient’s trust in a doctor? And what if the roles were reversed; if the person were receiving medical advice from the guru and spiritual guidance from the doctor? — Tom Storm

That may depend on the person, the ailment, the doctor, the advice being sought, the guru and the reason for your question.

Do you think faith only has to do with a lack of reason and knowledge?

But faith is basically always the same qua faith, it just may be self-deluded, or misplaced if the person or thing one has faith in is not reasonable or worthy.

It is hard to tell who is worthy. Just like it is hard to be a good doctor and a good guru. -

Measuring Qualia??Color is such a flat aspect of qualia. It does the trick, but really, when decorating a living room with someone and talking about why they like orange more than red, you probably get more intimate measures of their experience of red than any brain state data will tell you.

Taste is better than sight to understand qualia. Maybe her research wasn’t fully cooked and she doesn’t know what fully baked philosophy is supposed to taste like.

Are we talking about taking measurements of someone else’s brain that would enable us to predict whether that person will like or dislike the taste of strawberries, or just that when that person is eating X (which happens to be a strawberry), we can take measurements that show us he must be tasting strawberry?

Because really, along with all of the brain states, instead of measuring those, you could just watch his face as he eats a strawberry. Knowing the correlates in the brain is nice, but knowing exactly what it is like to be that guy eating a strawberry? When you love strawberries and he seems to hate them? You can know every inch of the brain state and still not account for taste. Or redness to him. Right?

I think the person in the video doesn’t understand the concept of qualia very deeply.

The scientists measured brains seeing red and noted the similarities. What if the scientists saw three similar brains all looking at the same color, but the scientists didn’t know what the color was? Could they figure out “that must look like a darker shade of taupe to those people”?

It’s the “like….to those people” that is not being touched by the science no matter how many times the speaker says “science.” -

Free Speech - Absolutist VS Restrictive? (Poll included)Do you think you can be responsible for the actions of others?

No. No one can control another’s motor cortex with words. — NOS4A2

Really. How about as a parent. Are you a parent? Do you think a parent can be responsible for the actions of their children? As in “kids, go spray paint the neighbors front door.” Do you think it’s all those kids fault and the parent’s little speech played no role in the paint in the neighbor’s door?

The legal history of the “yelling fire in a theatre case” is a red herring. The state can regulate speech when that speech leads to a crime that others commit or leads to harm caused by the actions of others. Check out Brandenburg v. Ohio if you want to be accurate. It overturned the “clear and present danger” test for regulating speech.

How about conspiracy laws? Mob boss says “go murder that guy.” And mob soldier goes out and murders that guy. Was the mob boss just an innocent speaker? Or part of conspiracy to commit murder and a murderer?

You are not answering my question.

How about laws? Don’t laws affect actions? Or a stop sign?

It’s obvious to me that my words cause others to take specific actions and so I can be held responsible for the outcome of the acts of others because they listened to my words.

Repeatedly talking about motor cortex’s is having no affect on the arguments. Motor cortex’s are how. They are not why. You are not talking politics and the question of free speech is a political one. -

Free Speech - Absolutist VS Restrictive? (Poll included)

I can’t tell if you are basically agreeing with me or what you are trying to modify about what I said.

You seem to be disagreeing with me. But you aren’t addressing anything I say specifically. As if we are scribbling at each other without communicating.

Free speech is not using scribbles in any way you want. If we were to do that, how would you hope to communicate with others — Harry Hindu

Take the word “free” out of the above and it is perfectly clearly true, and I think we both obviously agree about it. “speech is not using scribbles in any way you want. If we were to do that, how would you hope to communicate.” That makes perfect sense.

But “Free speech” is a political concept and saying “free” in your quote here doesn’t really say anything about the politics of free versus government regulated speech. You may as well have said “regulated speech is not using scribbles in any way you want. If we were to do that, how would you hope to communicate .” That is as true as your sentence regarding how language works, but says nothing about the difference between free and regulated speech (only their similarity as not being scribbles).

Free speech is not even saying anything you want without repercussions — Harry Hindu

That is not true. Free speech is precisely saying anything you want without governmental, state enforceable, repercussions.

There may be societal repercussions when you say “women should not be able to vote” or “stupid people need to be forced into education camps”, but freedom of speech means we all get to float any stupid idea we want to, and say it publicly and debate it as long as we want.

But if the speech incites harmful acts, the harmful actors can be punished.

And if those harm causing actors can demonstrate that they were incited to act by someone else’s speech, prompting them to trample their way out of a theater and kill someone, the speaker who promoted them may be held responsible for the actions of those who reacted to the speech. In such case, the state isn’t regulating the content of what was said (the content of the speech per se) but instead regulating the harmful effect caused by words said in a certain context to certain reasonable people.

That is the free speech question - when can the state tell someone to shut up? The starting point answer is never, unless that speech clearly incites illegal acts.

When speech has the only repercussion of pissing people off, or making them happy, or prompting more speech, it should never be abridged. No matter what it says or means. That is political freedom.

Free speech is not even saying anything you want without repercussions. That would be authoritarianism, not free speech, as the state would be able to say whatever they want without anyone questioning it — Harry Hindu

That doesn’t make any sense to me.

You are now talking about the state as a speaker.

Representatives of the state only get to speak on behalf of the state

- in court when the state prosecutes a crime, (which is precisely a debate to see who wins the argument)

- or when a diplomat speaks to a foreign state (in which case we all get to criticize or support what that diplomat said when they return home)

- or when the police arrest somebody, (which is also ultimately adjudicated in court.)

But politically, free speech means precisely everyone gets to say whatever they want, and people in government have to be free to say whatever they want as they are all just citizens - that’s government of the people, by the people, for the people. Candidates for office and elected leaders should be able to say whatever they want in political rallies. Legislators proposing legislation should be able to say whatever they want. All of that should be able to be debated, booed, harrayed, ignored. As long as it doesn’t obviously call for rioting, trampling, destroying private property.

In a free society, we can discuss and debate whether we should abolish private property, but until we change the current law protecting private property, no one gets to physically steal or trample other people and their property. And if my words “go storm the police station and burn it down” lead a frenzied mob to burn down the police station, I have broken the law by my speech. If those words lead to nothing, as me saying on TPF “go burn down your local police station” will lead to nothing, then the government should never be able to for TPF to take these words off the site.

Curfews, rules against yelling “fire!”, rules about inciting riots, rules about fraudulent or slanderous or “dangerous” speech - these are all fraught with the peril of authoritarianism.

But you do not seem to be focused on political speech. I don’t know what you are trying to say to me.

And I think you are a free speech proponent who sees the need to regulate harmful consequences like riots and trampling people running out of buildings because someone yelled “fire” - so I don’t know why you disagree with me so much.

Or are you saying we do have free speech? Or should not have free speech? -

Free Speech - Absolutist VS Restrictive? (Poll included)

Ok. So, I am arguing my words can cause a physical impact in the world, such that I can be held responsible, through speech, for causing others to trample someone to death.

So, I sent these words out into the world:

Then what is the point of a constitution or a law? About anything? Such as “free speech?” — Fire Ologist

And in response you said…

I enjoy posting here. I enjoy thinking and arguing about such topics. — NOS4A2

So apparently, I may be wrong. :grin:

But I don’t think you answered the question.

Do you think you can be responsible for the actions of others?

If yes, do you think words might help you accomplish such a feat?

If no, I’m glad you enjoy posting, because this seems to be the perfect place to do that.

Trust me, don’t yell “fire!” in a crowded room. Some people might hold you responsible for what other people do, that they will say was based on what you yelled.

I’m just saying “words can’t cause action in others” is not gonna fly in the courthouse.

Speech can be legally determined to be the cause of actions others take.

(I know you know this. But…

If you want to argue that speech causing others to act is metaphysically impossible, or physically impossible, or just not the case, that’s fine, but then what is the point of a constitution, or a law? About anything? Such as “free speech?

Laws are words written to regulate actions. Right?

You might just say “no point to them” and then can get back to posting and arguing the metaphysics.

But then we have just ruled out a discussion about a political issue on a thread about a political issue. -

What is faithAcceptance of truth on authority is something we do all the time, as in medicine, where we trust the authority of doctors, or in schools, where we trust the authority of teachers. In these cases the truth that we do not know ourselves but accept from others is a truth we could come to know ourselves if we went through the right training. In the case of divinely revealed truth, we can, ex hypothesi, never know it directly for ourselves (at least not in this life), but only on authority. The name we give to acceptance of truth on authority is “faith.” Faith is of truth; it is knowledge; it is knowledge derived from authority; it is rational. These features are present in the case of putting faith in what a doctor tells us about our health. What we know in this way is truth (it is truth about our health); it is knowledge (it is a coming to have what the doctor has, though not as the doctor has it); it is based on authority (it is based on the authority of the doctor); it is rational (it is rational to accept the authority of one’s doctor, ceteris paribus). Such knowledge is indirect. It goes to the truth through another. But it is knowledge. The difference is between knowing, say, that water is H2O because a chemist has told us and knowing that water is H2O because we have ourselves performed the experiments that prove it. The first is knowledge by faith, and the second is knowledge direct. — Peter L. P. Simpson, Political Illiberalism, 108-9

Good stuff.

We are rational in trusting our doctor, because we have evidence that… — Peter L. P. Simpson, Political Illiberalism, 108-9

Only after all evidence is gathered can we, by our choice and faith, consent to putting our lives in the hands of the doctor.

And so none of this discussion of ‘what is faith’ is necessarily about God or a religion. And further, relegating faith to belief without reason or incorrigible choice, only misunderstands faith (or far too narrowly construes it), and misunderstands the role of evidence and reasoning, and consent, and how people are called to act in everyday practical situations all of the time.

Thanks for posting that. -

Free Speech - Absolutist VS Restrictive? (Poll included)No one has made the case how the written word can "causally influence" a human being differently than any other mark on paper. — NOS4A2

Then what is the point of a constitution or a law? About anything? Such as “free speech?”

On another (but now related) topic, why are you bothering to post here? -

Free Speech - Absolutist VS Restrictive? (Poll included)But the point is, words are not meanings,

— Fire Ologist

I would need to you define "meaning", but honestly I'd much rather talk about free speech in a Free Speech thread. — Harry Hindu

The point of all of this is make clear that we should be politically free to say whatever words we want to, and to mean whatever we think we mean by those words in the context of adults discussing public policy, civil and criminal law…

…Words, meaning, and action need to be three separate things. — Fire Ologist

Words, meaning and action need to be three separate things in order to protect the right to free speech from its being abridged by the government, but to allow the government to punish actions that reasonably follow certain speech in certain context.

What if I’m standing in the doorway of a crowded theater and right across the street is a shooting range. And I decide to yell “fire!” — Fire Ologist

And let’s say everyone in the theatre panicked, runs and tramples someone to death.

In court, some of the issues would be:

What yelling “fire!” reasonably means?

What did I specifically mean when I yelled it?

If I could prove that I wasn’t thinking about where I was standing or who could hear me in the theatre, and I meant to prompt the guys across the street to “shoot their guns”, I would have a defense against the accusation that I meant “the building is burning” and that people should trample their way out.

Here, in order to adjudicate free speech, you need to separate words, meaning and action.

Wittgenstein should definitely let his lawyer do the talking. I’m not really commenting on meaning versus use versus language versus language games.

I’m saying the law that protects or limits speech based on its content (meaning) versus its consequential acts (where they are physical acts potentially/actually causing harm), such law must distinguish the word from its meaning and from its consequences.

We can’t legislate words and their meanings. That’s what free speech is about. Wittgenstein gets to debate with Aristotle all day long about essences and objective meanings. But where words lead to actions, we need to understand if it is reasonable that such words can be meant to cause such actions (in order to connect those specific consequential actions to the specific speaker whose specific words meant something to the specific listeners who acted in specifically harmful ways). -

Free Speech - Absolutist VS Restrictive? (Poll included)(When I say “bank” some might hear “river’s edge” and others might hear “building with money”. This is because words are distinct from meanings.)

— Fire Ologist

Wrong. — Harry Hindu

There are words, and separately, there are what the words signify or mean. The context in which a word is used is helpful to know what the word signifies or means. Context helps define the meaning, but the word remains just the word, separate from its meaning. Like “bank” in one context clearly has nothing to do with a river. And words are just scribbles and not even words if we don’t speak the language; and rules of grammar and such are all part of the context which allows words to convey meaning.

But the point is, words are not meanings, and meanings are not equivalent to words. We have two distinct concepts where we understand what a word is and what a meaning is. (Because meaning is most often described with words, people often see them is inseparably bound, but they are separable, and must be, for words to convey meaning.)

Sometimes we try to say something and have trouble, but as we fumble along someone else says “I still see what you mean” and then they prove it by having less trouble with their words and saying for you what you meant, and you say “yes, that is what I was trying to say.” That scenario hopefully helps show you that words and meanings are distinct things we have to juggle and organize when we communicate. The first person here managed to convey meaning without saying the right words, and this was proven when the second person said better words showing he had the meaning despite not being given the words that could convey that meaning by the first person.

Yelling “fire!” to a bunch of English speaking people in a crowded room, on one level is sound effect.

Separately, it also conveys meaning, such as “everyone, you should all understand that fire is burning nearby and may overcome this room so you better leave now!” (Or something similar, you get my meaning.).

A third distinct element here is an effect that follows after words convey meaning. Certain words convey a meaning that reasonably prompts those who understand the words and their meaning to action. Such as yelling “fire.” It is reasonable to assume people in a burning building will want to run out of the building upon hearing someone yell simply “Fire” because the act of yelling fire inside a building conveys the meaning “the the building your are in is burning, so you should get out.”

The point of all of this is make clear that we should be politically free to say whatever words we want to, and to mean whatever we think we mean by those words in the context of adults discussing public policy, civil and criminal law, all things political, all things artistic (again among adults), and really anything in the context of a discussion for the sake of discussion and exchanging our ideas. No law should ever limit that. And government can (and must) let societal influences sort out the parameters of what people end up thinking is appropriate or not. Government should make no laws “abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the government for a redress of grievances.” (ie. The First Amendment.)

But as soon as whatever is meant by whatever we say would reasonably prompt actions, not simply further discussion for the sake of exchanging ideas, like yelling “Fire!” in a crowded room for instance, then the person who yelled “”Fire!” when there is no such fire should be punishable by law for causing any harm that follows the reasonable response of a room full people who now think they are in burning building.

Many words to say “what’s ‘wrong’ about any of that as you say? Words, meaning, and action need to be three separate things. -

Free Speech - Absolutist VS Restrictive? (Poll included)

Maybe. Do you mean words and meaning are distinct? -

Free Speech - Absolutist VS Restrictive? (Poll included)Wrong. No one ever simply walks around and says, "bank". "Bank" is often used with other words and it the other words that provide the context of the meaning of "bank". The issue is in thinking that only individual words carry all the meaning when other words often change, or clarify the meaning of the other words in a sentence. So you probably shouldn't attribute meaning to words by themselves, but to the sentence they are part of. Just as a cell has no meaning on it's own. It's meaning manifests itself in it's relation with other cells, forming an organism. — Harry Hindu

Context helps define meaning, but it defines meaning of a particular word. The fact that you may not be able to tell my meaning by the way I use words doesn’t mean words and meaning (or use/function) are not distinct objects.

What if I’m standing in the doorway of a crowded theater and right across the street is a shooting range. And I decide to yell “fire!” Or I’m standing on a bridge and I point to a building that is sitting against the water has a sign on it Savings and Trust and I just say “bank” and point towards where the building meets the water?

If you want to know what I meant by those words, you would have to ask me for more words or better pointing.

You can undo the point I’m making by living in the real world where not everyone is an ironic comedian like myself, or you can wonder if Wittgenstein really was the last word on meaning and see how meaning is distinguishable from words. -

Magma Energy forever!

That’s funny.

I suggest adding that he is so handsome he is the only reason any sane guy might want to identify as a woman.

And Cc. Putin in the letter suggesting a partnership startup. -

Free Speech - Absolutist VS Restrictive? (Poll included)

Politics assumes:

- Individual people have bodies with senses enabling them to interact with each other and the world.

- Individual people use language consisting of written and spoken words as they interact with the world and each other.

- Language/words, once written or spoken, is a thing in itself, like the people with bodies are things in themselves.

- Language/words convey meaning from the speaker to the hearer/reader.

- Meanings of words are distinguishable from the words, like words are distinguishable from speakers and speakers are distinguishable from each other.

(When I say “bank” some might hear “river’s edge” and others might hear “building with money”. This is because words are distinct from meanings.)

If we chop any of these things out, politics doesn’t work. This is a conversation about free speech policy.

Maybe politics is an illusion, our senses are useless to sufficiently interact with the world and each other, words are just sounds, meaning is totally invented when sounds are constructed in the brain (which may be physical or we can’t tell…). But if all of that is up for grabs, who can say anyone actually said “fire!”, or whether there was a crowd that ran, or that “fire!” was supposed to mean “shoot” or “stay seated and eat candy” or “you are in danger if you stay seated”.

We can’t divorce the use of words to convey meaning and figure out whether words cause anything. Just like we can’t metaphysically divorce the notion of cause and effect from bodily interactions, and figure out what causes people to do whatever they do with their bodies.

Are we playing politics here or not?

For those arguing words can’t cause action, are you saying there need not be any laws or governments? Because what is the point of saying it should be legal to yell “fire!” in a crowded building - if we write a law “don’t yell fire or you can be held liable” who cares, because words don’t cause action?

We are talking philosophy of mind, mind-body problem, psychology, metaphysics of causality, but for the sake of governmental policy about public speech.

We don’t have to have a government if we don’t want to. But if we think we need one, it’s because people can use their bodies to harm other bodies and people can use words to mean something in others’ minds causing their actions that cause harm.

If we undo the possibility that the meaning of a word can cause an action in another, we undo politics.

When your boss tells you to chop that tree down, and you chop the tree down and it breaks someone’s house, you might not be liable for anything, if you are just acting according to your boss’s words of direction. Your boss might be liable for everything, or maybe not even he is held liable, but the company you both work for is. -

The Phenomenological Origins of Materialism

Most everyone got it completely wrong about women. But yes, he should have known better, or talked to a woman. Today we are getting it wrong about women all over again, in many new and fanciful ways.

I also think Darwin would have perplexed Aristotle quite a bit. But not undone him, at all. -

The Phenomenological Origins of Materialismwe do not access reality directly,

— T Clark — Fire Ologist

I agree with that. Except maybe the reality associated with our own existence. But that’s a small, lonely piece of being.

— Fire Ologist

I guess we're on the same page except I don't see "the reality associated with our own existence" as small or lonely. I think it's half of everything. The world is half out there and half in here. — T Clark

So I don’t think we are saying much differently here about reality. I agree that the world as presented in my mind is constructed by my mind using the “world out there” and my mind “in here” as its raw materials to make the construction presented in me. Since Kant we see this clearly, but Plato’s cavemen make a similar point.

I was talking about what we might know absolutely and certainly. The only bit I claim to know directly, meaning where the “out there” meets the “in here”, is my own existence, my own thinking.

So to be more precise, the vast, vast majority of reality can only be known indirectly (half out there and half in here), but I can know that I exist directly and absolutely (out there IS in here at once). I am a part of reality (like the out there), and I can know this (in here is now out there). Descartes actually said something. “I am” is absolute knowledge, to me. Further, I now directly can conclude “certain absolute knowledge also is real, because I know ‘I exist’ certainly and absolutely.” So ‘I am’ and ‘certain knowledge is’ are two absolute truths about reality, known by my own direct access to the objects now known, namely, my existence, and my knowledge of this as knowledge.

So there is some absolute knowledge for the knowing, but, as a good scientist, I find that it ends up only being knowledge about me that I can know directly. The fact that I can only know the world indirectly is a third absolute truth, but it is again, a truth about me and my limitation up against a world out there, and provides no color to the world, other than whatever color ‘I am’ might have (hard to pin down the color of my mind - also changes a lot!).

Yes, agreed, we have knowledge. Is some of it absolute? To me "absolute" means without uncertainly at least in this context. I don't know anything without uncertainty and I suspect you don't either. — T Clark

Just because what I say can be critiqued to the point of meaninglessness, the critique then would reclaim the real existence of meaning in the universe. So if we are to claim any knowledge at all, regardless of the degree of certainty we believe it may have, we must have set something absolute before us to distinguish this knowledge from the thing it certainly or uncertainly knows. We can’t make a move without fixing something absolutely. You can’t say you know nothing with certainty and mean what you say. Then the only thing you know absolutely is that you know nothing. That may be the extent of knowledge, making something known out of “nothing”, but then there you have something certainly; “I know nothing” becomes absolute knowledge. But besides this, thanks to Descartes, Socrates was wrong; he should have said he knew something after all - he certainly existed while he wondered if there was anything he could know.

But knowing thyself is a small lonely science, (maybe until you admit this “self”, which is real in the world, is a mixture, requiring interaction with the “out there” as it forms “in here” during its self-reflection/thinking/perception. This would all grow as absolutely certain knowledge then. Now we are following Hegel.)

There is no wall between different aspects of reality, but there is a wall between different aspects of how we think about that reality. Physics and my family are both parts of reality, but I don't generally use the same words to describe them. — T Clark

This all describes one reality (as far as I can tell). You agreed with Tom who said there are multiple realities, based on multiple perspectives and frameworks.

But here you say “There is no wall between different aspects of reality.” That points to only one reality.

Above you said “The world is half out there and half in here.” That is one whole reality as well.

Here you say “ Physics and my family are both parts of reality…”

That’s parts of one reality.

One world.

Being always means the same being.

(I think a clarification between “reality” and “being” and “world” and may “the subjective experience” may be helpful here, but that would require we start this conversation over, and I think we are making points without such clarifications. And I would rather not write a book here on TPF. But maybe we have to…) -

The Phenomenological Origins of Materialismthis (multiple realities) makes it impossible to be wrong, which makes philosophy worthless. — Count Timothy von Icarus

Yes, this is why I pointed out:

in all disagreements we should all be saying “you might be right” and in all agreements we should all be saying “we might both be wrong” — Fire Ologist

Luckily for we philosophers, reality pushes back against such worthless debate. -

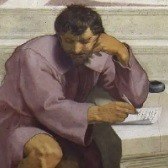

The Phenomenological Origins of MaterialismI want to say, because people don’t appreciate Aristotle.

The reason for so very, very many problems in modern philosophy... :rofl: — Count Timothy von Icarus

It really is a shame.

I think it is all because religion aligns with him and today academics refuse to align with religion, Aristotle is simply not understood.

The man was a badass. He should be as revered in the history of science as he was by religion. Francis Bacon picked up the baton after Aristotle started the race. All of those before Aristotle were running qualifying heats, but Aristotle organized all of it into science. -

The Phenomenological Origins of Materialism

we do not access reality directly, — T Clark

I agree with that. Except maybe the reality associated with our own existence. But that’s a small, lonely piece of being.

, nor can we claim any definitive knowledge of what reality ultimately is. — T Clark

This itself is knowledge.

I think we have knowledge. I think some of it is absolute, but that as an honest scientist, we should be skeptical of its absoluteness. But as a person, interacting with other people, we claim absolute knowledge between each other all of the time. Otherwise in all disagreements we should all be saying “you might be right” and in all agreements we should all be saying “we might both be wrong” but people are not so agreeable as that at all.

What we encounter instead are multiple realities, each intelligible through particular conceptual frameworks or perspectives. — T Clark

That sounds like one reality.

Multiple encounters and perspectives and frameworks keep it interesting, as does reality itself keep us interested. But why leap to the conclusion that some kind of wall separates one reality from another, when the distinction could be seen as two different ways into the same forrest?

I think Wittgenstein and Aristotle and Heraclitus and Empedocles, and Hegel and Kant, and Nietzsche, were having one conversation about one thing. They are all trying to say the same thing. I ask between Witt and Aristotle, why do you each say it so differently?

If change is all there is and is absolute, whatever we say about the many things changing before our many eyes will be burned up and lost to the change. So if “reality” is whatever we say about changing things, there are so many realities there may as well be none (and you may as well hold that “what we encounter instead are multiple realities.”) But if that really is the case, if as Heraclitus says, “all is change”, I find the concept “multiple realities” to be an equivocation on the word “reality” and that what is really meant and distinguished here is that “the one reality is change, always changing.” -

The Phenomenological Origins of MaterialismOne metaphysical position does not, can not, address all of reality. We need to use different ones in different situations. — T Clark

I don’t know if I agree with that.

I am making the grossly imprecise observation that if materialism was correct, if someone followed this intuition, “my brother” could not refer to anything other than atoms, and similarly, any references to “history” and “personality” would be references to my own mental abuses of words, unspeakable and incommunicable, until translated back into atoms perhaps.

I’m not a materialist. My brother is real. His atoms will never explain, or be useful to demonstrate, his sense of humor. -

Beyond the PaleNo, that's not up to me. Either when i get there there's a 1:1 match between you directions and my location, or there is not. I do not judge whether that is the case - it either is or isn't and I observe which it is. However, that analogy doesn't hold with my point - if you gave me an active, working Google Maps. I closed my eyes, followed the directions(pretend for a moment this wouldn't be practically disastrous lmao) and then the Maps tells me i've arrived - that's what I'm talking about. I am literally not involved in any deliberation - I am, in fact, still taking instruction. It would have been a judgement whether to actually engage this course of action, though, to be sure. — AmadeusD

I don’t mean to interrupt, but it seems like you both may basically agree on what a judgment is, but are finding fault with the application of the definition to the scenario, or various scenarios.

If I am not mistaken, I think you both would agree that the bolded part above speaks to a moment of judgment. Amadeus said it, and it seems to reflect a moment Leon is describing as judgment.

So you must be agreeing on something basic/essential/definitional about judgments.

Amadeus seems to be saying no more judgment is needed to carry out the course of action.

Leon is saying there are more pivotal moments requiring more judgments.

This may mean you are disagreeing with some underlying definition of judgment, but then I don’t think Amadeus would have made the above bolded statement if there was some glaring conflict between you regarding the nature of judgment.

I happen to agree with Leon, and don’t see how you can follow directions blindly, and skip adjudicating between when a step is completed and when the next step begins. When I am following directions, I know that I could misunderstand the direction and go astray and end up lost and not at my destination. I also know that Google maps is wrong and has led me to the wrong destination. So at each step, I have to decide “Is the last step completed yet? Can I move on to the next step? Is where I am driving what is meant by this next step? Is Google still correct of should I switch to Apple Maps?

Often these interim judgments are easy and immediately made, but that doesn’t mean they aren’t judgments. -

The Phenomenological Origins of Materialismwe use different points of view depending on what we are talking about. We use different ones when we are talking about electrons than when we are talking about our brothers. — T Clark

But if “everything is collocations of atoms, ensembles of balls of stuff,' or that 'things are what they are made of,’” what does my brother really add to a scientific discussion of things? What point of view isn’t reduced to its matter? What does point of view matter, apart from its material cause?

So discussions of nature or essence or my brother are all in my mind, which is really neurons and balls of stuff.

“It was essential to leave out or subtract subjective appearances and the human mind -- as well as human intentions and purposes -- from the physical world in order to permit this powerful but austere spatiotemporal conception of objective physical reality to develop.”

— Thomas Nagel, Mind and Cosmos, Pp35-36

That is basically the same point. Subtract my actual brother when discussing my brother, which is really a discussion of atoms and physics.

Fire Ologist

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum