-

My own (personal) beef with the real numbersI think we agree that it's bad pedagogy to simply posit the reals with no explanation and no time or ability to answer very expected and natural questions. — boethius

The opposite argument is that it's bad pedagogy to expect high school students to understand the sophisticated constructions of higher math. It's true in all disciplines that at each level of study we tell lies that we then correct with more sophisticated lies later. It's easy to say we should present set theory and a rigorous account of the reals to mathematically talented high school students. It's much less clear what we should do with the average ones. Probably just do things the way we do them now. -

My own (personal) beef with the real numbersThereafter I avoided abstract algebra. — jgill

Difficult to take abstract at grad level without undergrad. Abstract algebra shows up everywhere. Physics is a lot of group theory these days. -

Qualia and Quantum Mechanics, The SequelYou know Penrose's idea? He thinks consciousness originates in quantum interactions in the microtubules of the brain.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Quantum_mind

http://nautil.us/issue/47/consciousness/roger-penrose-on-why-consciousness-does-not-compute

https://bigthink.com/paul-ratner/why-a-genius-scientist-thinks-our-consciousness-originates-at-the-quantum-level

Nobody takes this idea too seriously; but like a lot of Sir Roger's ideas, his bad ideas are better than most other people's good ones. -

My own (personal) beef with the real numbersSome years ago the New Math was in vogue. As a mere instructor at the time I was given a text on College Algebra having a lengthy first chapter devoted to an axiomatic approach to the subject. It was not a good experience for instructor or student. — jgill

Yup. New math, new new math, Common Core. One educrat failure after another. I have no idea what the answer is. -

Infinite Bananasso I would welcome your thoughts on SDG/SIA — aletheist

I don't know enough. I know that it's categorical in flavor ... but then again so is differential geometry. I'll dispatch a clone to study up on SIA and another clone to read the collected works of Peirce ... uh oh I haven't got any clones. That means these tasks might not get done any time soon if ever.

Accepting the common-sense notion [of time], then, I say that it conflicts with that to suppose that there is ever any discontinuity in change. That is to say, between any two instantaneous states there must be a lapse of time during which the change is continuous, not merely in that false continuity which the calculus recognizes but in a much stricter sense. — Peirce, R 300, 1908

Sounds like Peirce is rejecting discontinuous functions. Or something like that. I know that in constructive math, all functions are computably continuous or something like that. Makes some of the problems go away.

That particular text is incomplete and largely unpublished, but there is a transcription online — aletheist

Oh jeez I gave that link a look. Not exactly a clear writer IMO. I don't think I could ever slog through this.

You might be interested in John Bell's book, The Continuous and the Infinitesimal in Mathematics and Philosophy. — aletheist

Dispatching a clone. Not the first time I've had this book recommended to me. Sigh.

And the defining characteristic involving squared infinitesimals seems just another strange notion one can avoid — jgill

I always thought this was an abstraction of basic 17th century calculus, where higher powers of infinitesimals can be ignored. -

My own (personal) beef with the real numbersI'm familiar with the axioms (I'm a child of new math, if you know what that 1960s fad was), — tim wood

Yes, that was an attempt to teach set theory in grade school. Needless to say the teachers were confused and the students were confused. Big fail. Now we have Common Core. The teachers are confused and the students are confused. In the US, public school students learn math in spite of the curriculum, not because of it.

but the lub - well, that's not so clear. Maybe because it's too obvious - that happens.

From online

"Let S be a non-empty set of real numbers.

1) A real number x is called an upper bound for S if x ≥ s for all s ∈ S.

2) A real number x is the least upper bound (or supremum) for S if x is an upper bound for S and x ≤ y for every upper bound y of S."

1) is pretty clear. With respect to integers only, given the set (1,2,3) 3 is an upper bound. Now here's maybe the question the answer to which will help me out. 3 is an upper bound, but is it correct to say that all x, x>3 are also upper bounds, and that 3 is the least upper bound? — tim wood

Yes. And for example 1 is the least upper bound of the set .9, .99, .999, .9999, etc.

And the idea that the rationals do not provide a lub for the square root of two simply means that although there is no end of upper bounds, for any upper bound that seems a candidate for the lub, a better candidate can always be found, in the rationals. If this is it, then I understand the lub. — tim wood

Yes. Again consider where is the rationals. No matter what upper bound you pick, there is no least upper bound in the rationals. So the rationals are not complete. (Or Cauchy-complete, or topologically complete, to distinguish this from other uses of the word complete).

But that set does have a least upper bound in the reals. In fact every nonempty set of reals bounded above has a least upper bound. That fact uniquely characterizes the real numbers among all totally ordered fields.

Here the pro forma question, though it's evolved since the first paragraph. And even this you've already answered. It seems to me that to question the existence of a measure, or distance, or number corresponding to the square root of two is the greatest nonsense, because it is so easily modeled, and a fortiori any other irrational. Almost as easily is π modeled, so with transcendentals. — tim wood

Yes definitely. There are so many ways to develop the square root of 2. You don't even need least upper bounds. You can do it with pure algebra. If is a purely formal symbol that means nothing, but has the property that , then consider the set of all formal expressions

Define addition componentwise, and multiplication using the usual distributive law. Then it's easy to see that is closed under addition and multiplication, and that multiplication distributes over addition, etc.

What about inverses? It's not immediately obvious, but in fact if then

https://math.stackexchange.com/questions/821260/inverting-ab-sqrt2-in-the-field-bbb-q-sqrt2

In other words our set is a field (add, subtract, multiply, divide) that contains a square root of 2.

But, just as with the real number earlier, all we've done is define some formal symbols that have the right properties. Can we construct such a field using set theory? Yes. If you have seen some abstract algebra, here is the construction.

You start with , defined as the set of all polynomials in one variable having integer coefficients. We can add, subtract, and multiply any two such polynomials as we learned in high school. So is a commutative ring.

Now the set of all multiples of the polynomial is an ideal in this ring. Ideals in rings are analogous to normal subgroups in group theory. You can "mod out" by an ideal to get another ring. In this case the ideal generated by , denoted , is a maximal ideal; and therefore (it's a theorem) that when you mod out by you get a field. And what field do you get? You get a field isomorphic to our field of formal made-up symbols.

This is a bit of abstract algebra that most people haven't seen unless they took that course. But the point is that we can whip up a field containing a square root of 2 in the usual two ways: We can invent it as a make-believe set of formal symbols that behave according to some rules; AND we can construct such a beast within set theory.

This gives all the mathematical existence it needs.

Apologies if this exposition was a bit too much abstract algebra. But perhaps someone reading this took a course in groups, rings, and fields but forgot this beautiful construction, which we can sum up in one equation:

On the left we have a made-up collection of formal symbols that mean nothing; on the right, we have a concrete realization of that thing cooked up within set theory.

Again, note that this construction parallels how we define the real numbers. We make up a formal system using some rules; and then we show that such a thing can be built out of spare parts within set theory. That is mathematical existence.

Nor is a numeral for any of these lacking, if by "numeral" is meant a name. Of course an exact decimal representation is a problem, But then so is my idea of the perfect woman (pace wife). But it appears that the proof of these things ignores the obvious: irrational numbers are easily proved to exist. For me, I guess, the question is, what is (was) the problem? What the need for the thingie? (If for some arcane application, that's enough of an answer: likely I could not follow anything more than that.) And ty, btw. — tim wood

Seems that way to me too. Our friend @Metaphysician Undercover, who must be a neo-Pythagorean, is mightily vexed by the fact that the square root of 2 is (a) a commonplace geometric object, being the diagonal of a unit square; and (b) doesn't happen to be the ratio of any two integers.

What of it? Humans got over this about 2500 years ago. -

Infinite BananasIn any case, scholars of Peirce's mathematical thought seem to agree that it comes much closer to being a rigorous implementation of his conceptions of infinitesimals and continuity than NSA. — aletheist

So just as I call modern constructivism Brouwers revenge, I can call SIA Peirce's revenge. This is very interesting. Do you happen to know how SIA relates to constructive math? They both deny excluded middle as I understand it.

either absolutely unchanging or always changing continuously. — Peirce, R 300, 1908

What's R 300? Where can I find Peirce talking about calculus? I don't suppose I could ask for a simple explanation of what this phrase means? Is it anything like the quotient of dy and dx being the derivative when dy and dx "become" zero but aren't actually zero, as Newton thought of it?

ps -- Why are there so many Peirceans on this forum? I never hear about him anywhere else but his ideas are incredibly interesting.

For another, functions in SDG/SIA "are differentiable arbitrarily many times" — aletheist

Aha. That's also true of the complex analytic functions in standard math. If a complex function (function from the complex to the complex numbers) is differentiable once, it's automatically infinitely differentiable. So complex differentiable functions are extremely well-behaved. Whereas real number functions (reals to reals) can be very wild, and differentiable only once, or twice, or some finite number of times before they are no longer differentiable. I wonder if this is related to SIA somehow. -

My own (personal) beef with the real numbersBut this isn't what the words "constructing a number" suggest to me. Any light for the darkness, here? — tim wood

Construct in this context means build a thingie within set theory that behaves exactly like we want our thingie to do.

For this purpose, the construction of Dedekind cuts (linked earlier) is a construction of the real numbers. But how do I know that? It's because we first write down properties we want the real numbers to have; then everyone can use them, even though we don't know whether they exist mathematically. The construction shows that they do.

Let me expand this in full gory detail.

Here are the axioms for a totally ordered, Cauchy-complete, infinite field.

https://sites.math.washington.edu/~hart/m524/realprop.pdf

This PDF lists the properties of the real numbers. It's much better than the Wiki link on the same topic.

Briefly you can do arithmetic: a + b = b + a, and multiplication distributes over addition and ab = ba, and if b is nonzero then the quotient a/b exists. Then you have the order relations: for any two distinct reals either a < b or b < a.

Now the rationals satisfy these properties; so we need one more special property that fully characterizes the real numbers: The Least Upper Bound property, which says that every nonempty set of reals bounded above, has a least upper bound. This is also known as the completeness axiom. It says there are no "holes" in the real numbers.

Example. The rationals don't satisfy the LUB property. The nonempty set does not have a least upper bound! This came up earlier. This is why the rationals aren't a mathematical continuum.

The real numbers -- whatever they are -- SHOULD have this property.

Now as far as we know, there is no such abstract object that satisfies these properties. Maybe the real numbers don't exist. But it doesn't matter. We can just use their properties. We can do physics, engineering, calculus, etc ... even if the real numbers don't exist. Just by using their properties!

But now a someone comes along and calls the entire enterprise null and void because for all we know, we're talking about something that doesn't exist. But if you believe in the rationals, you must believe in Dedekind cuts; and the set of Dedekind cuts satisfies all the real number properties. So we are justified in calling the set of Dedekind cuts the real numbers.

Having seen this construction once in our lives, we are confident that the real numbers are mathematically legitimate, because we can build an object using set theory that behaves exactly like the real numbers. We now forget all about it; till someone asks, "Oh yeah? How do we know there is any such thing as the real numbers?" Then we show them.

tl;dr: The real numbers are anything that satisfies the list of real number properties. But is there even any such thing at all? Yes. Within ZF set theory we can build up a set that has exactly these properties. We can in fact do this in several different ways. They're all isomorphic. We call any of these models the real numbers.

Was this helpful? -

My own (personal) beef with the real numbersThe whole point of my post is that high school students would have no way of stating their questions succinctly as you demand, but they are in my view meaningful questions to ask. — boethius

We're in deep and complete agreement on this. The mathematical definition of the real numbers is far beyond high school students; in analogy with the difficulties Newton and Leibniz had, which needed to wait 200 years for resolution.Instead of accepting the conclusion that root 2 is irrational (not a rational number) — boethius

Instead of accepting the conclusion that root 2 is irrational — boethius

This fact has a proof, 2300 years old dating to Euclid's written account; but most likely at least several hundred years older than that.

The subject of the square root of 2 is part of my response to @Metaphysician Undercover in the bijection thread. I'm drafting a response that will expound at length on the mathematics and the mathematical philosophy of the square root of 2. I hope to corral my thoughts into a postable screed within a week or so. Meanwhile please forgive my lack of comment today on the mathematical existence of a positive real number whose square is 2. I believe in such a real number and I believe it's not the ratio of integers and I believe that it's computable, hence encodes only a finite amount of information despite its endless and patternless decimal representation. A real number is not its decimal representation. I hope you believe these things too.

ps -- Note well The irrationality of the square root of 2 does NOT introduce infinity into mathematics. All the irrationals familiar to us are computable, and have finite representations. The noncomputable reals do introduce infinity into math; but plenty of people who don't believe in noncomputable reals nevertheless DO believe in the square root of 2. Namely, the constructive mathematicians.

Please demonstrate how this infinite numerator and denominator either does not get counted in Cantor's diagonal proof, does not represent an irrational value, or there is something preventing finding and placing all the digits of suitable real numbers into a numerator and denominator to solve for root 2. — boethius

Euclid's proof of the irrationality of has nothing at all to do with Cantor's discovery of the uncountability of the reals. The rest of this paragraph, I confess, is not intelligible to me.

What axioms does a high school student possess to avoid the above issue of concluding root 2 is rational? — boethius

None whatever. In high school we mumble something about "infinite decimals" while frantically waving our hands; and the brighter students manage not to be permanently scarred for life.

The teaching of mathematics in the US public schools is execrable. How many times do I have to agree with you about this? I'd gladly join you in a protest down at the local school board, but it would do no good. The educrats have bought off and bamboozled the politicians. The teaching of math in the US is stupid by order of the government. I wish I could do something about it.

Followup question (as I believe this is what interests you to demonstrate) what axioms does a university student possess to avoid the above issue and how? — boethius

A university student in anything other than math: None.

A well-schooled undergrad math major? Someone who took courses in real and complex analysis, number theory, abstract algebra, set theory, and topology? They could construct the real numbers starting from the axioms of ZF. They could then define continuity and limits and I could rigorously found calculus. It's not taught in any one course, it's just something you pick up after awhile. The axiom of infinity gives you the natural numbers as a model of the Peano axioms. From those you can build up the integers; then the rationals; and then the reals. Every math major sees this process once in their life but not twice. Nobody actually uses the formal definitions. It's just good to know that we could write them down if we had to.

So, as I've noted already, people who study math in university get all their conceptual questions about the real numbers and the nature of calculus answered. The physicists, engineers, economists, pre-meds, and everyone else, do not. The formal constructions aren't important as long as you know the rules for manipulating real numbers. Even the mathematicians just use the real numbers according to the rules of addition and subtraction and so forth. The formal constructions are to demonstrate that the real numbers have logically valid mathematical existence. [As always please don't jump in just to point out that this is not necessarily actual existence. I quite agree].

Buildings and bridges are made of quarks. But architects and bridge builders don't need to know particle physics. Likewise nobody needs to care about the formal definition of the real numbers; except that if they ask, they can honestly be told that there is one. And of course it's all on Wikipedia.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dedekind_cut -

Infinite BananasInfinitesimals are deeply illogical/impossible concepts and are shunned by most of maths. — Devans99

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hyperreal_number

The hyperreals are a model of the first-order axioms of the real numbers that contain infinitesimals. To construct them requires a weak form of the axiom of choice. In the 1970's nonstandard analysis, based on the hyperreals, was touted as a better way to teach calculus. Results are mixed. Most studies showed that students come out of standard or nonstandard calculus classes equally confused. No new math is introduced with the hyperreals; that is, anything you can prove with them you can already prove with the standard reals. That's why they haven't caught on. The standard reals have extensive mindshare. But infinitesimals have been made logically legit as of 1948.

If you truly want to understand the mathematics of infinitesimals, I recommend learning about synthetic differential geometry, also called smooth infinitesimal analysis. These links are to excellent brief introductions by Sergio Fabi and John Bell, respectively. — aletheist

Yes, yet another way to do infinitesimals. I'll check out your links since I don't know much about SIA.

A moment of time has a duration that is not zero, but is less than any assignable or measurable value relative to any arbitrarily chosen unit. — aletheist

Quibble I must. Nobody knows what a "moment of time" is, or if it's modeled by any of the various mathematical models of infinitesimals. I object to this claim. There's no currently accepted theory of physics that supports what you said AFAIK. Math Physics. -

My own (personal) beef with the real numbersSo if you want to get back on track, answer my questions concerning the real numbers i — boethius

Perhaps you could state them succinctly. I prefer not to wade into this. You have an ax to grind and I've only succeeded in upsetting you. If you'll list some clear questions I'll do my best to respond. My sense is that you didn't actually read your own post. If you did, you'd realize that you have no beef with the real numbers, only with their teaching in high school. I share many of your concerns in that regard.

You did state that ZF should be taught in high school and ZFC in college. That does not make sense to me at all. ZF is a fairly sophisticated system. I wouldn't teach a full course in ZF to high school students except to the most mathematically motivated and talented students. ZFC actually adds very little in terms of complexity or teachability. If anything, the axiom of choice regularizes infinite sets and eliminates a lot of problems. For example absent choice, there's an infinite set that's not Dedekind-infinite. Surely you don't mean to claim we should be teaching this to high school students. -

Universe as simulation and how to simulate qualiaI am hoping to find something less senseless than “room is conscious”. — Zelebg

I'm not an expert in these matters. Perhaps someone else can jump in. -

Continua are Impossible To Define Mathematically?My ears tell me sound is infinite, when I study music. There is an infinity within the limit of the highest and lowest frequency. — Gregory

Your eyes tell you there is a continuous gradation of light. Physics proves otherwise.

For that matter your senses tell you the world is flat. Science shows otherwise. -

My own (personal) beef with the real numbersAs for the intricacies of the real number system, I wonder — jgill

It's worth noting that the pedagogy retraces the history.

Newton developed calculus to study the motions of the heavens. He was not able to drill down a logical explanation of his methods even to the standards of rigor of the day. He had no idea what his derivative (what he called a fluxion) was. If we contemplate the expression (in Leibniz's notation, which was better than Newton's) , what exactly is it? If the numerator and denominator are not zero, that's NOT the derivative. If they are, then the expression is not mathematically defined.

The philosopher George Berkeley sarcastically called Newton's fluxions, "The ghost of departed quantities." What a great line. If these guys came back today they'd all be on the Internet flaming away at each other.

Newton struggled with the logical nature of infinitesimals and limits. In fact his publications clearly show that he didn't ignore the issue at all, but was rather keenly aware of the problem and tried hard over his lifetime, without success, to come up with a good explanation.

Dating from 1687, the publication of Newton's Principia, to the 1880's, after Cantor's set theory and the 19th century work of Cauchy and Weirstrass and the other great pioneers of real analysis; it took two centuries for the smartest people in the world to finally come up with the logically rigorous concept of the limit. For the first time we could write down some axioms and definitions and have a perfectly valid logical theory of calculus.

This was a very great achievement of humanity, one not very well appreciated. We don't teach the history of math. In addition to "Pull down the exponent and subtract 1" that we beat students over the head with, it would be great if we could impart the sense of mathematicians working on this problem of defining limits for 200 years before they worked it out.

It's no surprise that these are extremely subtle concepts to understand. So in high school and college we just tell people that real numbers are mysterious "infinite decimals," whatever that means, and no harm is done. And in calculus class we show people what limits are but we can't really be precise, so mostly we focus on techniques, which the physicists and engineers and economists will need for their work.

The development of the real numbers and the limit concept in the 19th century is one of our greatest intellectual achievements. I wish there were more appreciation of it. -

Continua are Impossible To Define Mathematically?Violins can create an infinity of sounds with infinitesimal changes. — Gregory

I do not believe that could be true according to the known laws of physics. A sufficiently high frequency would eventually require back-and-forth movement of the bow in space smaller than the Planck length.

To be clear, since this is a common misunderstanding: The Planck scale is the point at which our theories of physics break down and may no longer be applied. It does NOT mean the world itself is quantized. Below the Planck length we simply do not know and can't even speculate, because our physics no longer works.

With that understanding, if there is a length below which we can not analyze or understand; there is a highest possible frequency. And within them, to discriminate one from another must likewise become impossible. There are not infinitely many gradations, to the best of my understanding of things.

After all quantum theory says that light is not infinitely variable. Pretty reasonable that sound isn't either. -

My own (personal) beef with the real numbersTD;LR: we should teach ZF in high school and then add C later for pure maths students. — boethius

What??

First, the technical construction(s) of the reals are taught only to math majors in a class called Real Analysis. Nobody who's not either a math major or someone taking that class as an elective ever sees the technicalities. Perhaps they teach high school kids advanced real analysis in high school in Russia or China but truly I doubt that very much.

Second, if your complaint is with pedagogy it's not about math. And certainly there are many problems with the way math is taught. But that is not a beef with the real numbers. In fact I didn't see you present any beef with the real numbers. I only saw you beef with the teaching of the real numbers; a subject on which I'm in complete agreement with you in the large, if not necessarily every detail. When I'm emperor of the world the first thing I'm going to do is send all the math curriculum boards off to Gitmo. I've long held that idea.

And third, what does the axiom of choice have to do with anything? It's certainly not needed to define or construct the reals. Teach ZF to high school students? What, teach ordinals and cardinals to high school students? It would be fun to teach ZF to SOME high school students, the especially mathematically talented ones. The mainstream, no. I wonder what you are talking about here. Again, the axiom of choice is not needed to defined or construct the reals.

as small as you want ... but not infinitesimal — boethius

That IS the essence of the real numbers. There are no infinitesimals in the standard real numbers. I think perhaps you had an unhappy calculus class, as most students do. They don't teach the technical definition of the real numbers in calculus. Perhaps what you're unhappy about is that you didn't have a more rigorous class in calculus. But that's not done because calculus is a service class for a lot of physics, engineering, economics, and other majors. The math majors have to make the best of it till real analysis class.

In fact this is the very reason there's so much confusion about the real numbers. Nobody is ever taught what the real numbers are simply because it's not relevant to anyone's profession unless they're going to be a math major. So even technical professionals like physicists and engineers don't know what a real number is. And then when you get to online discussion forums, you get a lot of confusion on the subject.

I appreciate that you agreed with what I wrote, but what you wrote didn't have much if anything to do with it. I think what you are calling for is better teaching of the reals to high school students, which I'd also like to see. But to go into the full technical details is way beyond high school students.

[Disclaimer: Poster quotes me in AGREEMENT and I give him a hard time. I'm a terrible person. Forgive me]. -

Infinite BananasIn my view, nothing within mathematics is actual — aletheist

I admit to not understanding the distinction between real and actual as you tried to explain it in this post. But consider Internet security. Are cryptocurrencies and online security actual? They have actual (in the everyday sense) impact in the real world of our lives. But online security is based on public key cryptography, which is 100% based on abstract number theory; namely, the theory of factoring large composite numbers.

It's interested that for over 2000 years, number theory was considered beautiful but useless mathematics. It wasn't till the mid 1980's that public key cryptography was invented and then used as the basis of all online encryption and security.

This is a striking example of abstract, meaningless math becoming suddenly actual.

What say you? Again I confess I don't know what you mean by real versus actual. Can you give an example? -

Infinite BananasYes, given the standard mathematical definitions, the proposition that the number denoted by "5" possesses the character denoted by "prime" is true. Do you think that either of these terms denotes something actual? — aletheist

Yes I do. That's why I can't so easily sign on to the proposition that math isn't true. Some parts of math are obviously true, or actual. It's easy enough to say that abstract math isn't true in the sense of physically true. But there are truths that aren't physical. "5 is prime" is one of them. The axiom of infinity is NOT one of them. The axiom of infinity is taken as an axiom in set theory but is not (as far as we know) true or even meaningful in the actual world. But "5 is prime" IS true in the actual world.

Is that a distinction you find meaningful? Or do you not make a distinction between "5 is prime" and the axiom of infinity? -

Infinite BananasEverything that "exists" in mathematics is merely logically possible, not actual. — aletheist

Question: Do you think that "5 is prime" is true? Or merely logically possible? Or a complete fiction made up by evil set theorists?

I think "5 is prime" presents a challenge to those who say that math isn't true. "Actual" as you put it. Is "5 is prime" actual or not? And if not, what is it? -

The InternetNot disagreeing with you here. I'm just relatively angry with the fact that the internet made personal critical evaluation of information so easy that it should have made highly marketed ways of thought less relevant. And it seems like the marketing won in the last decade and it became even more relevant. I'm giving up and just accepting that mankind will probably always fail no matter how much easier technology will make things for us. — Qmeri

I quite agree. The Internet was going to change the world for the better but in many very serious ways made it worse. Just look at China's social credit system and ubiquitous surveillance tied to facial recognition all controlled by AI. And in the US we have our own version of that kind of control, but it's enforced by corporations acting on behalf of the state, instead of by the state directly. That's because in the US we have "freedom." Or what's left of it.

The world's become a techno-dystopia before our eyes.

Happy 2020s! — Qmeri

Likewise! -

The InternetA man who understands the internet and has the charisma and the means to market himself for his audience. — Qmeri

But enough about Obama, who ran a brilliant social media campaign.

https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2017/01/did-america-need-a-social-media-president/512405/

You know FDR used radio for his "fireside chats" to speak directly to the American people using the latest technology of his day. Isn't it perfectly natural for politicians to use the latest communication technology? If FDR lived today he'd be on Twitter.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fireside_chats -

Epistemology versus computabilityYes, but what is computer without display screen? — Zelebg

A server. They run the Internet. This website runs on a server in some datacenter. There's no display connected to it. When the IT folks need to access it they log in remotely over the network.

Haven't followed the discussion but just happened to notice this. Computers without display screens are extremely common. -

Universe as simulation and how to simulate qualiaExactly, so I'm looking if there are any arguments claiming the opposite. — Zelebg

Sure, everyone who disagrees with Searle about the Chinese room argument. Just Google Chinese room and half the links will be on one side and half on the other. -

Universe as simulation and how to simulate qualiaThere are two distinct ideas that are often conflated in the literature.

* The video game argument. In the 70's we had Pong and now we have realtime networked shoot 'em ups; so in the future "a simulation will be indistinguishable from reality." But this assumes there is a mind doing the distinguishing. If you put a super duper VR headset on me and wire it up to a supercomputer, you could simulate a very convincing reality for me. But it would still be my mind doing the experiencing. We'd be back to Descartes' evil daemon. Even if you are fooling me, my mind exists.

So this idea doesn't explain the mind or even attempt to.

* The idea that the mind itself is a simulation. That a computer program could implement a mind. Now we're back to Searle's Chinese room. We have no evidence that a computer could implement a mind; only simulate an environment.

A lot of the AI hype that I read does not distinguish these two cases. -

Infinite BananasI called the groups of bananas 'collections' rather than 'sets' to get around the issue of sets having to be composed of distinct objects. — Devans99

I don't think that helps any. You're starting out with bad notation and that's leading to incorrect conclusions. By collection do you mean a proper class of bananas? That's a lot of bananas.

Perhaps you mean what's called in computing a multiset, or (older terminology) a bag. If so say that. If you mean something else, say that. That's what notation is for: to engender clarity of communication. -

Continua are Impossible To Define Mathematically?That's right, I'm not curious about that math — Metaphysician Undercover

Then we have nothing to talk about. I still owe you my thoughts on the bijection thread, where you made a couple of remarks that I can use as a starting point.

It's curious, though, that you are so interested in the philosophy of math yet so uninterested in math. Your math is wrong. You have some ill-formed ideas that are leading you astray. And you have no interest in clarifying your own errors. Hard to know what to make of that.

If your attitude is that these foundations were built by the greats, therefore there are no weak points, (appeal to authority resolves fundamental problems), then I think you are in need of God's help. — Metaphysician Undercover

Not something I've ever said. If I have said such a thing, please be so kind as to quote my words directly. You can't because I never said any such thing. It's pathetic that your only means of discourse is to lie.

Since I explicitly mentioned all the alternative models of the continuum that I'm familiar with, your remark has no basis in reality; other than your own reality of incoherent bullshit. -

Continua are Impossible To Define Mathematically?:lol: Not likely. I thought the thread needed some comic relief. — jgill

Good, I thought it was just me. In fact after I posted I looked up his name and found that when he submitted his 2005 papers (so fifteen years ago) one reviewer rejected him saying that he "lacks fundamental understanding of basic calculus." Exactly the same criticism I noted. -

Infinite Bananas{b, b, b, b, …}

{b, b, b, b, …} — Devans99

Inaccurate notation, since by the axiom of extensionality, the set {b,b,b,b,b,...} is the exact same set as {b}. Perhaps if you notate it your argument will be more clear. -

Continua are Impossible To Define Mathematically?The issue is not so much the mathematical definition itself, which I have acknowledged is adequate for most practical purposes. It is the widespread misconception that what most mathematicians call a continuum--anything isomorphic with the real numbers--is indeed continuous, and thus has the property of continuity. We seem to agree that it is not and does not. — aletheist

Ah. But I'd call that a strawman. The "widespread misconception." There isn't ANYBODY out there beating the drum for the proposition that the mathematical real line is the "true" continuum, whatever true might mean in this context. The overwhelming majority of mathematicians give the matter no thought at all. If they're studying differential equations or abstract algebra or proving Fermat's last theorem, they're simply not concerned with such matters.

And among those mathematicians who have taken the time and trouble to think about the nature of the continuum, they'd know about Brouwer and the modern constructivists and the hyperreals and if they studied some philosophy they'd get some context for the conceptual objections to the real numbers as the "true" continuum (again, whatever that might mean), and they'd most likely agree that the standard mathematical real numbers leave a lot to be desired in the philosophical realm,

I just don't think there are that many people who have thought about the matter for five minutes and don't have some sympathy for the alternative point of view. I don't think there is a widespread misconception. I think there's a widespread lack of interest in the question; and among those who are interested, some degree of agreement that the real numbers don't express everything we think must be true about a continuum. -

Continua are Impossible To Define Mathematically?Perhaps Peter Lynds' essay — jgill

Wow that nutball Peter Lynds is still around? I heard of him about ten years ago ... maybe fifteen or twenty, now that I think about it. It was on Usenet. So it must have been at least twenty years. Tempus fugit.

I remember that he had solved Zeno, or some such ... I actually don't remember the particulars. Everyone on sci.math was talking about him with varying opinions. Lynds had written two papers. I downloaded and read them both line by line with close attention. I concluded that Mr. Lynds needed a good course in basic calculus. I regarded him at that time as a minor crank.

I have not heard his name since then. If in the intervening decades he has managed to acquire mindshare among ... well anyone, frankly ... I wish to register my dissent.

No need to disagree, this isn't a hill I'm going to die on. And maybe he's reformed his ways and is now writing articles of actual substance. If so I'd appreciate a link to anything recent that he's done. If there's new evidence I'll change my opinion. As it is. the mere mention of his name annoys me. As Dennis Miller used to say back when he used to be funny, That's just my opinion, I could be wrong.

The real numbers cannot fulfill the conditions of a proper definition of "continuity". Real numbers produce a sequence of contiguous units. Contiguity implies a boundary of separation between one and another. This boundary must produce an actual separation between one number and the next, to allow that each has a separate value. This is contrary to "continuity" which is the consistency of the same thing.

So mathematicians have created a term, "continuum", which applies to a succession of separate units, allowing that each is different, so there is something missing in between them, and that "something", which is the difference in value, is unaccounted for. Therefore "continuum" means something completely different from "continuity".

The rational numbers are an attempt to account for this "something", the difference in value, which exists between the reals. This an attempt to create a true continuity. However, the irrationals appear, and foil this attempt. So mathematics still does not have a continuity. — Metaphysician Undercover

In my post that you were replying to, I took pains to explicitly mention the following:

Note please that I'm only saying what a mathematical continuum is. I'm not addressing any of the many philosophical objections there could be to calling the real numbers a continuum, But mathematically, the reals are a continuum and the rationals are not. — fishfry

Since I wrote that, I wonder why you replied as you did. I'm perfectly well aware of the philosophical objections to calling the real numbers a continuum.

It's also a fact about the world that mathematicians regard the real numbers as the (mathematical) continuum.

My disclaimer made it perfectly clear that I understand the distinction between the mathematical continuum and the various philosophical approaches. In recent years I've studied the classical intuitionist continuum, (Brouwer et. al.), the modern constructivist continuum, the hyperreal line of nonstandard analysis (that's the one with the reals plus infinitesimals), and I've even seen a little Peirce. I have sympathy towards these points of view.

I wonder why you feel compelled to respond to me so irrelevantly, with such trite philosophy and inaccurate mathematics. Your remarks regarding the rationals are particularly unenlightened.

I'd welcome substantive engagement with you but I told you in the other thread that I find your style unpleasant. To me this is more of the same. You saw my disclaimer but couldn't help yourself piling on with the usual ... usual.

I am in the process of writing a reply to some of the things you read in the bijection thread. I read everything you wrote. I have a better understanding of your ideas. This is not the place and I'll try to finish that post up soon. I'll put my thoughts into a larger context. Meanwhile what is your point in telling me what I already know?

That's right, the existence of irrationals really throws a wrench into the rational number line. Where do those irrationals exist in relation to that line? — Metaphysician Undercover

You have asked a mathematical answer. I'd be happy to give you a mathematical answer.

My concern is that no matter what mathematical points I make, you're just going to pile on with the usual nihilism and simplistic philosophy that math must be wrong because it's not true. As if everyone doesn't already know that math isn't literally true. You're the only one flailing at this strawman.

The irrationals fill in all the holes in the rationals. I already illustrated this with a sequence of rationals that approaches the point sqrt(2) but there's a hole there instead of a point. The irrationals fill in those holes.

We can formalize the process of filling in the holes with various technical constructions of the reals. There are several, the two best known being Dedekind cuts and Cauchy sequences. The details aren't of interest. The point is that it can be done within set theory and it allows us to found calculus in a logically rigorous way, something that escaped Newton and Leibniz. We can also axiomatically define the reals as "the unique Cauchy-complete totally ordered infinite field." When you unpack the technical terms, you end up with an axiomatic system that's satisfied within set theory by the Dedekind cuts or Cauchy sequences. It's all very neat. One need not believe in it or care. It must be frustrating to you to both not believe in it, yet care so much!

I could drill the math down a lot more but should probably wait for encouragement, and if none is forthcoming I should leave it be. I don't think you're curious about the math at all. You just want to throw rocks. But why? People uninterested in chess don't spend their lives hating on chess. They just ignore it. You think math is bullshit? Maybe you're right. Maybe it is all bullshit. The thing is why do you keep repeating the point over and over as if we haven't all heard you already? And as if we all don't already understand the point?

Am I being too harsh? Maybe. I don't know. You misunderstand me. Perhaps I misunderstand you. Why would you reply to my post at all? You don't think I know anything. Why'd you even bother? -

Continua are Impossible To Define Mathematically?I don't see why Zeno's paradox is not a paradox but Banach-Tarski is. — Gregory

Naming conventions are a matter of historical accident. Banach-Tarski is a theorem. It's not actually a paradox. It is however a veridical paradox, which is a true result that is contrary to intuition. If you want to call it the Banach-Tarski theorem that would be both accurate and less confusing. It's not really a paradox. It does show the distinction between abstract math and physics. The kinds of set-theoretic manipulations required in Banach-Tarski can't be done in the real world ... as far as we know, anyway. -

Continua are Impossible To Define Mathematically?Incidentally, your compact form of Leibnitz expansion has a simple error. And 1/3 =.333... = limit of a geometric series, well defined. You may be talking about mathematicians who labour in foundations. Making such fine distinctions is unnecessary in most math careers, IMHO. — jgill

Oops thanks I left out the exponent of the -1. Fixed it.

Not sure I followed the rest of your remark. My post is intended to clarify the thinking of all who say that "irrational numbers introduce infinity into mathematics." This is actually false. It's noncomputable numbers that introduce infinity into mathematics. A far more subtle and philosophically interesting point.

In any event I'm not arguing that working mathematicians care about these fine points in their daily work. I'm simply noting that a number is not any one of its representations; and that having an infinite decimal expression is an artifact of radix notation and not the real numbers themselves. After all pi and the square root of 2 have perfectly finite Turing machines that generate their decimal representations. That's the key point. Not who thinks about what during the work day. -

Continua are Impossible To Define Mathematically?Continuum is a set of points where for every two points in the set there exists a point in the set that is in between the two points. — Magnus Anderson

I happened on this remark which you made a while ago. I wanted to note a correction.

Consider the rational numbers. They have what's called a dense linear ordering, which means that between any two rationals there exists another rational. Just take their midpoint, for example, which must be rational.

But the rationals fail to be Cauchy-complete. For example the sequence 1, 1.4, 1.41, ... etc. that converges to sqrt(2), fails to converge in the rationals because sqrt(2) is not rational. There's a hole in the rational number line.

That is not a continuum, mathematically or morally.

What characterizes a continuum is the least upper bound property. This says that every nonempty set of reals that is bounded above, has a least upper bound.

The least upper bound property is false for the rationals. For example the set

where is the set of rationals, does not have a least upper bound in the rationals. But it DOES have a least upper bound in the reals.

That's exactly why the reals are regarded as a mathematical continuum, and the rationals aren't.

Note please that I'm only saying what a mathematical continuum is. I'm not addressing any of the many philosophical objections there could be to calling the real numbers a continuum, But mathematically, the reals are a continuum and the rationals are not.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Least-upper-bound_property -

The bijection problem the natural numbers and the even numbersBeyond finite instances, cardinalities are not numbers. They are equivalence classes. — jgill

Quibble-wise this is not true. Originally, a cardinal was the class of all sets with that cardinality. The trouble is that those classes are proper classes and not sets; and we want to define cardinals as sets so that we can use the rules of set theory on them.

I wrote a longer exposition but I'll just shorthand this and provide the links.

Case 1: Assume the axiom of choice. Then given a set , the axiom of choice says that can be well-ordered; that is, there is some ordinal such that and are in bijection. Since the proper class of ordinals is well-ordered, there must therefore be a least such ordinal that's cardinally equivalent to . We define that as the cardinal of .

For example is the ordinal corresponding to the natural numbers; and by this definition, . And is defined as the first uncountable ordinal, . (Yes there are uncountable ordinals, even without the axiom of choice. How counterintuitive is that!)

Case 2: Assume the negation of choice. Then there's some set that can't be well-ordered so we can't use the idea as in case 1. Instead (I'm going to just fly through this for sake of brevity and supply the links if anyone's interested) the cardinal of a set is the set of sets bijectively equivalent to the given set whose rank is the same as that set. The idea is that each set has a "born on" date called its rank; and the collection of all ranks forms the Von Neumann hierarchy. Each level is a set, and the union of all the levels is the universe of sets. So given some set, we find the level at which it first appears; and we defined its cardinal as the set of all bijectively equivalent sets at that level.

This isn't supposed to make sense if you haven't seen it. As I noted, I drafted but didn't post a much longer exposition of these matters which would not be of interest to anyone who's not already studying advanced set theory.

The main point is that this is how you define cardinal numbers these days. They're no longer equivalence classes of sets that themselves aren't sets. That was a problem so it got fixed at the expense of needing to do some technical work.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ordinal_number

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cumulative_hierarchy

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Von_Neumann_universe

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Scott%27s_trick -

The bijection problem the natural numbers and the even numbersI think fishfry said something to the effect that bijection has precedence of injection. Why? — TheMadFool

I have not followed all these posts for a while so I don't know if this is still a point of confusion. I just want to assure you that I never could have possibly said any such thing; for the simple reason that I don't have any idea what that means.

The point that you were hung up on before is that the definition of a bijection says that there exists at least one bijection between two sets. The fact that a million other functions between the sets don't happen to be bijections is irrelevant. It's an existential condition. If it rained for five minutes today and was otherwise sunny, it's still true that "it rained today." I hope someone's been able to clarify that for you. -

Continua are Impossible To Define Mathematically?But there is no way to mark an exact irrational length on the ruler - unless a line representing an irrational distance is constructed (like the square root of two) and marked on the ruler by direct measurement. Correct? — tim wood

Depends on what you mean by mark. Every point on the real line "marks" that point. All the irrationals and even the noncomputable reals. Every real number is the location of some point on the real number line.

Of course if you mean construct as in compass and straightedge, that's different of course. But every point is at some exact real number location to the left or right of the origin. All the points are marked, the way I see it. Perhaps we're talking semantics. -

The bijection problem the natural numbers and the even numbersI accept. I ought to because I've delivered a few and felt justified doing so, so I ought to take if I've earned. — tim wood

Rock and roll Brother Tim. Thanks for the kind words. It's all good.

I haven't read the intervening posts so perhaps some of these points have been covered. I did want to toss in my two cents about uncountable bijections, and how the subject of bijections relates to the subject of well-ordering. In short, it doesn't at this level. It's not an unreasonable thing to think, as I came to learn. But bijections are defined between sets; and sets have no inherent order. The sets {a,b,c} and {c,b,a} are the exact same set. Any maps between them, including bijections, pertain only to the elements and not to any order properties the sets might have.

Of course there are ordered sets, along with the order preserving bijections between them. Among these are the well-ordered sets, which lead to the beautiful topic of the ordinal numbers. I could talk about the ordinals all day. But not right now, because they're peripheral to the subject of basic bijections. I hope you'll take this on faith now, and the following examples will bring out this point. In this post I'll limit myself to discussing bijections.

Now I'm going to walk through six bijections between uncountable sets.

(1) The question arises: Can there be a bijection between uncountable sets?

Suppose there were such a thing. What's the most obvious example we could think of? How about the identity map on the reals; that is, the function given by .

This function should look familiar to everyone who took analytic geometry in high school. Its graph is a straight line through the origin making an angle of 45 degrees or radians with the positive -axis. This is such a familiar mathematical object that we never stop to think that it's a bijection between two uncountable sets.

We now have at least one example of a bijection between uncountable sets. And in passing we've proven a theorem.

Theorem: Every set is cardinally equivalent to itself.

Proof: The set's identity function provides the required bijection.

In other words, cardinal equivalence is a reflexive relation.

(2) Even though the real numbers aren't well ordered, the identity map preserves the usual order on the reals. (The usual order is the one we learned in grade school). So maybe bijections are related to order properties after all??? But no. Consider the bijection from the reals to itself given by everywhere except that , , and .

This bijection does not preserve order, because but . And you can see that we could easily cook up far more complicated nested cycles and loops and tricks that would make bijections as complicated as we want. So we can see that order properties are a separate consideration from whether or not a function is a bijection.

By the way we have a familiar name for a bijection from a set to itself: a permutation. Permutations of finite sets are more familiar to us, but you can permute infinite sets as well. Every permutation of a set is a bijection from that set to itself; and most of them are completely random, they don't preserve order or any other property.

(3) The function between and given by , with inverse function .

This has already been mentioned earlier in the thread. There are two points of interest.

* This bijection shows that bijections do not necessarily preserve length. And in general, bijections don't necessarily preserve measure, the abstract generalization of length, area, volume, etc. A circle of radius 1 is bijectively equivalent to a circle of radius 2. Bijections don't preserve measure. Good to know.

* Both and its inverse are continuous in the sense of freshman calculus. Very informally, their graphs can be drawn without lifting your pencil from the paper.

In the mathematical discipline of topology, two topological spaces are regarded as equivalent if there is such a bi-continuous bijection between them (meaning the bijection and its inverse are both continuous). The intuitive meaning is that we can stretch or shrink or twist one space into the other without ripping or tearing or poking holes. If you've ever seen one of those illustrations of a donut being turned into a coffee cup, that mathematical trick is done using a continuous bijection.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Mug_and_Torus_morph.gif

(4) The continuous bijection between and given by , with inverse .

The tangent function is usually defined as sine over cosine, but it's more helpful to think of it as the function that inputs an angle, and outputs the slope of the line through the origin making that angle with the positive -axis. If you think of a clock with a single hand that goes from 6 counterclockwise to 12, as the angle goes from to , the slope goes from to . That is, the tangent function is a bijection from the open interval to the entire real line . Its inverse, the arctangent, maps the entire real line to the the open interval .

Since both the tangent and the arctangent are continuous, we see that a bounded open interval is topologically equivalent to the entire real line. Not only do bijections fail to preserve finite lengths; they can't even distinguish between finite and infinite lengths. And topology can't tell the difference either. You can take the tiniest imaginable open interval of the real numbers, and stretch it like taffy till it becomes the entire real line.

(5) "Cantor's surprise." For any positive integer , the -dimensional Euclidean space has the same cardinality as the real numbers.

Cantor originally thought that the real numbers had cardinality ; and the plane had cardinality , and Euclidean 3-space had cardinality , and so forth. [In math, dimensional space just means the set of all -tuples of real numbers, with pointwise addition and scalar multiplication by reals, just as with the usual x-y plane and x-y-z space. Nothing to do with "time as the fourth dimension" or rolled-up dimensions in string theory or any other physical interpreation. That's sometimes a point of confusion.]

He was surprised to realize that in fact all finite-dimensional Euclidean spaces have the same cardinality. Here's the proof. We'll show that the open unit interval and the open unit square have the same cardinality. That is, we'll show a bijection between the real numbers strictly between 0 and 1, and the set of ordered pairs in the x-y plane each of whose coordinates are strictly between 0 and 1.

Suppose is a point in the open unit square with decimal representations and respectively. We map the pair to a single real number by interleaving the digits to get .

It's clear that you can reverse this process. Given any real number you can de-interleave its digits to get a pair of real numbers. We can extend the result from the unit interval to the entire real line via the tangent/arctangent. Of course this bijection is highly discontinuous, it has no nice properties at all.

You can clearly interleave -digits this way, and that's the proof. When Cantor discovered this result he wrote to his friend Dedekind: "I see it but I don't believe it!"

We saw earlier that bijections don't necessarily preserve length or volume. Now we see that bijections don't necessarily preserve dimension. It's good to keep in mind the limitations as well as the utility of bijections.

Quibble: One could note that some real numbers have two distinct decimal representation, such as , possibly messing up the bijection. But there are only countably many such problematic reals, and we can formalize the principle that "countable sets never make a difference in uncountability arguments." The problem can be fixed.

(6) Can we find a bijection between and ? There must be one but it's tricky.

First, why must there be a bijection? We've seen earlier that there's a bijection between and the entire real line. And and are both proper subsets of the real line and proper supersets of . So both of those cardinalities are squeezed between two equal cardinalities. In other words if is the cardinality of the set , then:

, but the first and last cardinalities are equal via the tangent/arctangent. So and must have the same cardinality; after all they only differ by a point.

If you've seen the story of the Hilbert hotel, you know that you can always shift each guest to the next higher room, in effect "losing a guest." And if you were to move each guest to the next lower-numbered room, the hotel would still be full and you'd have an extra guest with no room! This is the basic idea behind adding or getting rid of endpoints in all these kinds of problems.

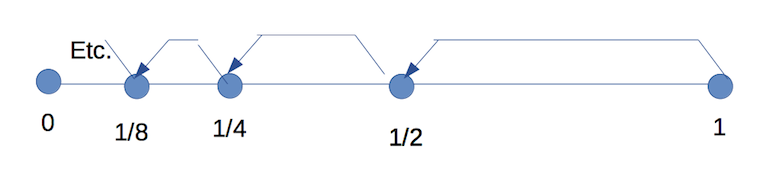

In this case we pick out a countable subset of , and "Hilbert shift" away that pesky 1 at the right end. Here's the function :

[Something funny about the markup, ignore those brl things, the forum software put them in].

Everything gets mapped to itself; except that 1 goes to 1/2, 1/2 goes to 1/4, 1/4 goes to 1/8, and so on. We've "made the 1 disappear" by Hilbert-shifting it to the "next room" as it were, and we have our bijection.

Here's a picture of what happens. 1 goes to 1/2, 1/2 goes to 1/4, and so forth. Every point has somewhere to go, and nothing replaces the point at 1. It disappears like the guest in the first room of the Hilbert hotel.

-

Continua are Impossible To Define Mathematically?Irrational numbers are not only irrational, but they go on forever ... — Gregory

No, this is not true. But it's such a common misunderstanding that a bit of exposition is in order.

One of the first things to know about the philosophy of math is the distinction between a number, on the one hand, and a representation of a number, on the other. 5, five, fünf, cinco, 2 + 2 + 1, 4.999..., the number of points on a mystical pentagram, and "half of ten" are all distinct representations of the same number.

So what's a number? If one is a Platonist, the number 5 is the abstract thingie out in the Platonic world "pointed to" or represented by each of those representations that I listed. If one rejects Platonism, I suppose we could get by saying that the number 5 is the collection of all possible finite-length strings of symbols that represent that number. (Although when it comes to numbers, an anti-Platonist has a tough row to hoe, suggesting that a Martian mathematician would not necessarily know the concept of five, or that there weren't five things before there were people to count them).

But whether one is a Platonist or not, one must distinguish between the abstract concept of the number 5 and any of its many representations.

Now, a real number is a real number. The exact definition of a real number is a technical matter for math majors and isn't too important at the moment. What is important is to understand that a real number HAS a decimal representation, sometimes two! But it is wrong to say that a real number IS a decimal representation.

One can be forgiven for wrongly believing the latter, since it's what we tell high school students. And even in technical disciplines, the distinction's not important. A working professional engineer, even a working professional research physicist, does not need to know or care about the distinction between a real number and its decimal representation.

There are only two classes of people who need to carefully make this distinction: mathematicians, who are trained on this topic in their undergrad years; and philosophers, who SHOULD BE but often aren't cognizant of the distinction.

Now decimal notation happens to be broken. Some perfectly sensible and familiar rational numbers, such as 1/3 = .3333333..., have infinitely-long decimal representations. That's not because 1/3 is broken; it's because decimal representation is.

Likewise some perfectly familiar integers, like 5 = 4.9999..., have TWO distinct decimal representations. Again, this isn't because real numbers are broken [though for the record, in this post I'm not necessarily arguing that they're not!]; it's because decimal representation has these well-known flaws.

The same applies to pi and the circumference in the sense of infinite fintude. — Gregory

So what about a real number like ? Does represent or encode an infinite amount of information? NO it does not! I will now show three distinct finite length descriptions of that uniquely characterize that particular real number:

* The first is the famous Leibniz series for :

This is a finite string of symbols in a formal language that unambiguously characterizes the real number , and that, Platonism or not, would without doubt be recognized as such by a Martian mathematician.

* But ok suppose that you don't like those dots. We can compactify the notation as follows:

[NOTE: Typo in formula corrected].

* But ok, perhaps you don't like the notion of infinitary processes, even in compact notation that only uses finitely many symbols in a formal language. In this case:

is the smallest positive zero of the sine function.

Our Martian mathematician would have no trouble agreeing with that. And it's a finite string of symbols written in plain English, with no infinitary process in sight, that uniquely and unambiguously characterizes the real number .

So in fact the real number encodes only a finite amount of information. This is true also of every real number you can name, such as the square root of 2, the base of the natural logarithm , the golden ratio , and so forth.

Are there real numbers that can't possibly be expressed with a finite amount of information? Most definitely. These are the noncomputable real numbers as defined by Alan Turing in his landmark 1936 paper that defined the nature of computation. In constructive math, one doubts the existence of such numbers; but that discussion is for another time.

Takeaway: Every real number that you know encodes only a finite amount of information and can be expressed using only a finite number of symbols. Decimal representation is defective to the extent that some reals require infinitely many symbols and others have two distinct representations. But a real number is not any of its particular representations, so this is not a philosophical problem.

Maybe math proves that something can come from nothing since spatially finite comes directly with spatial infinity. — Gregory

Math proves no such thing, since your examples don't hold up to mathematical scrutiny. But more strongly, as many posters have already noted (hundreds if not thousands of times on this site over the years), math can prove nothing at all about the world. At best, math is a super-handy (and as Putnam and Quine might put it, indispensable) tool for building mathematical models of physical theories. Newton and Einstein both used math to express their respective theories of gravity; even though neither, strictly speaking, is true. They're both just approximations that describe the experiments and observations we're able to do with our current level of technology. I hope this point is clear not only here, but once and for all on this forum. Science isn't true. Science is our best mathematical model that fits the observations we're able to make with the equipment we're able to build subject to technology and funding. (As the government bureaucrat pointed out in the film, The Right Stuff: "No bucks, no Buck Rogers!")

Nothingness is not dark, but white and shining says the Tibetan Book of the dead — Gregory

Way cool, but perhaps a little off the mark in this particular conversation. -

The bijection problem the natural numbers and the even numbersFor me it can be difficult to tell whether something's technical or not if I'm unfamiliar with it. — fdrake

Ok then what's wrong with, "Can you please explain yourself," versus, "My drill sergeant says you should suck it up, buttercup." What is the point? I do hang out on the Craigslist forums, where "Fuck you moron" is regarded as just as intellectually appropriate as quoting Aquinas. If this place is devolving to the CL forums I can play too. Hey @tim wood go fuck yourself. Everyone happy now? As if I don't know how to be an Internet jerk. I come to this forum in the hopes that I DON'T have to be an Internet jerk just to hold my own in a conversation. -

The bijection problem the natural numbers and the even numbersI think you need to check your math privilege. — fdrake

I just don't understand the insult culture around here. Over the past couple of years I've had to take extended breaks from this forum because someone started piling on personal insults at me over technical matters on which they happened to be flat out wrong. Not because I can't snap back; but because I'm perfectly capable of snapping back, and that's not what I'm here for. I'd suggest to members that whenever they throw an insult in lieu of a fact, perhaps they should consider whether they've got any facts.

fishfry

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum