-

Global warming and chaosMaybe we should exterminate whole existence all together. Exactly that is what we are heading for, so you will be served at back and call! Or shall we provide everyone with effective means to be shot into oblivion? Is the only way out collective suicide? — Raymond

I didn't say that. I simply advocate not continuing other existence by passively not procreating. The only thing we the existing can do is commiserate.. but we can't.. WORK HAS TO GET DONE. Don't you see? Things decay.. Things move forward and we need to survive, etc. So we the living have no relief. -

Global warming and chaosHowever, meaningful relationships, creativity, and the experience of other positives that are not "trivial" for countless sentient beings do not deserve to be prevented simply because nobody is capable of asking for them before they exist. You would once again say that nobody is deprived from their absence, but this misses the point entirely because, as I have mentioned ad nauseum if the lack of bads can be good sans any conscious feeling of satisfaction, the absence of the goods is necessarily bad. — DA671

Ok, so you are not paying attention to what I am saying again. Because you are mischaracterizing my argument over and over, I'll break it down:

This isn't about an actual child prior to procreation. It is about the parent. YOU as the parent decide:

1) Someone is born and they are harmed. This is a known result of being born.

2) Someone is not born and they are not harmed.

Why considerations of "But they will like the happy moments" matters, is what I am questioning. That is exactly what I think is neutral in terms of ethical calculation. Happiness prevented has zero ethical obligations attached to it. Only suffering prevented has ethical obligations to it. AND furthermore, IF happiness is a gift bestowed upon someone AT THE COST of a life time full of various harmful experiences, that is no gift at all, and is in fact an UNETHICAL (though I would reduce it to being misguided to not be hyperbolic) line of reasoning, as that is no gift at all, but a gift attached with burdensome conditional circumstances put upon the recipient. Back to my analogy.. If you give a gift to someone and that gift entails a lifetime worth of painful experiences of various degrees and intensities, that is not a gift.

No person existed beforehand to "need" happy experiences. YOU created that need FOR THEM. You cannot create the circumstances whereby one can get deprived of happiness (by birthing them) JUST so you can say, "Look they now need happiness and we don't wan to deprive them!". Rather, you caused people to NEED happiness in the first place (by birthing them), for which they could be NOW BE deprived. -

Global warming and chaosso I apologise if I came off as being rude. — DA671

No that's fine.. It's the stringing together the BS that follows this statement I have a problem with so let's see...

I also explained that nobody in inexistence is craving s prevention of all life. However, if it can still be good to prevent all harms, it's also bad to prevent all happiness, irrespective of whether or not there is a conscious feeling of deprivation. — DA671

So you are not paying attention to my argument. Again, I said:

If no one exists, no one suffers. Put a value on that of what you want (good, bad, neutral). If someone exists, someone suffers. The value part comes in when you as the parent/already existing person processes this and makes an action or inaction from it. So the parent decides that no one will suffer when they could have. My point is, this inaction (to not procreate), has no collateral damage to an actual person (as they are not born). However, an action (procreating) will create collateral damage, as there will actually be a person that suffers, whatever other good that comes from it. I think the moral choice is to prevent that suffering, and am pointing out that there is no collateral damage either. — schopenhauer1

In one scenario collateral damage of suffering occurs, in the other, it does not. The parent makes this choice. I am not taking the view from nowhere, as you are trying to make this out (the void of voided nobodies voiding nowhere).

The prevented suffering also doesn't "matter" to anybody and doesn't fill anybody with relief. However, when one can say that preventing harms is good, I don't think that it's reasonable to believe that it wouldn't be bad to prevent all the goods. — DA671

Again dude, here is the argument again: In one instance no ONE suffers. In the other, someone does. This is a violation of this principle explained eariler:

The basis for this is basically that it is never good to cause unnecessary suffering (in the first place) that is not trivial and inescapable unless extreme measures are taken (like starvation or suicide). It puts people in a bind of comply or die as well (if you don't like the "rules of the life game" you must "deal with it and go fuck yourself if you don't like it"..aka commit suicide). — schopenhauer1

So if you believe in not creating for someone else an inescapable, non-trivial set of harmful experiences (and/or suffering depending on how that is defined), then this would not be good to impose on someone else.

Ans that right there is the crux of the issue— I don't think that it makes sense to say that the absence of harms is good even though it doesn't actually lead to a benefit for anybody (except in an abstract sense), but the lack of good isn't problematic. It's certainly good to focus on reducing suffering for existing people, since that's usually sufficient for them to live decent lives. However, in the case of creating people, I think that it can be good to create potential happiness. — DA671

Again dude, stop trying to turn this argument as a view from nowhere. It is the view of someone making the decision to procreate. Do you want to create a set of inescapable (excepting suicide or death in someone sense) harms on someone else?

I never said it didn't. However, if one believes that not creating a person is good due to prevented harms, it's also unimaginably bad due to all the prevented goods. All the valuable lives cannot be relegated to being collateral damage (and yes, it would indeed be bad to prevent the good if it's good to prevent the harms). — DA671

Huh? To what weird non-entity are we owing happiness to? Who has been besmirched their happiness? That is right... no ONE. And yes, suffering is the collateral damage that goes along with thinking that you are going to create happy experiences.

There's also "thank you for this single opportunity of experiencing joy, which, despite being precious and fragile, has been a source of inimitable value". The right is still necessary, but it isn't sensible to think that bestowing the ethereal positives is unnecessary or worthless; it most definitely isn't. — DA671

"Who" is saying this? No actual person. The void. Your head.

The point is that if you believe that it's better to prevent all the negatives, it's also worse to prevent all the positives. — DA671

There is no justification you have made here, just assertion. There is no principle other than, happiness is something that can be experienced once born. That doesn't just magically resolve the boondogle of the collateral damage problem. It doesn't "cancel out" that suffering was still thus created. It is indeed imposing a lifetime of negative experiences on someone else's behalf. Guess what recourse they have? None. Comply with the program or kill yourself. Real nice.. And please, spare me another argument where you again say, "But happiness exists and therefore all solved".

The absence of suffering also doesn't matter (and is therefore not a solution) for the nonexistent beings in the void, by the same token. If the lack of harms is still preferable in an instrumental/abstract sense, the lack of goods is certainly a problem. — DA671

This is definitely a slippery slope then. For you, someone has to be born in order to realize the bad. It's from the procreator's perspective, not the void. This is not a "If a tree falls in the forest" argument as someone is existing to determine if they want to create a set of negative experiences on someone else's behalf.. and thinking it through.. Is it right to cause unnecessary suffering on someone because you yourself have a notion of them experiencing happiness as well? You will say, "Yep justified", as if happiness negates causing the bad. It would constantly ignoring the very argument of the antinatalist, that happiness existing for people negates the negatives they must endure.

Nevertheless, it's irrational to suggest that the bringing about the absence of all harms that nobody is desperate to avoid is an obligation — DA671

I mean, let's say I give you a gift you liked and then created a situation whereby other non-wanted experiences happened to you as well as a contingency of the gift.. It doesn't seem like that gift was a gift anymore, but rather a sort of gaslighting burden.. "You get this but, oops watch out for that!! Too bad, that's part of the contingency of my gift fucker!! Oh you don't like it? Kill yourself.. most other people just take it.. now sit back down and take it too!!!"

It wouldn't be particularly nice to prevent all happiness, even if your intentions were to just stop the possibility of harms. — DA671

Again WHO is this not nice to? You are speaking to the void again.

The truth is not convolution. The reality is that universal antinatalism does imply that even if a person would have a deeply meaningful life and would cherish their existence (and hope to relive it), it supposedly would not be good to create them, which is something that seems patently absurd to me. But I digress—the reality is that there's it's unreasonable to consider the lack of harms to be preferable whilst failing to see that the positives will also always matter. — DA671

You are trying to cause some sentimental argument.. (argument from pathos let's say), but you need a person for there to be deprived of this meaning, and you don't have it. Just the void. This is about the decision to procreate.. Not people that are already born. Do you want to be the cause for imposing the conditions whereby other people will suffer? If your answer is, "But, but, but happy experiences!!" Then that is not a good enough threshold to decide you will create the conditions of a lifetime of negative experiences for someone else..

Pain is also not an entity that requires a sacrifice of happiness at the altar of "prevention". Nobody in nonexistence has a need for preventing everything that would inundate them with relief. But if it can still be good to ensure that future harms don't exist, it's quite apparent that it's unethical to prevent all the positives. The lack of happiness could certainly be considered a collateral damage (or a much bigger damage, since most peop — DA671Thank you for your kind words. Hope you have a nice weekend! — DA671

For the final time hopefully, this is not about the nobodies not existing. This is about not creating a situation for someone else in the first place. It is not unethical to prevent "all the positives". Not creating happiness is neutral if anything. Not creating suffering is where it matters ethically. Nothing existing is nothing existing. Something existing starts harm where there is none, and happiness that is also created doesn't negate this.

Thank you for your kind words. Hope you have a nice weekend! — DA671

Yeah same. Just a tip.. if you want to quote a text, drag your mouse over the text and let go, then click on the quote button that displays. This will create the text in quote form in your reply post. -

Global warming and chaosAlso, I don't think that creating valuable lives has much to do with causing harm. — DA671

Not on its own. I said that creating "good" comes with the collateral damage of suffering, and that is a problem for your ethical argument.

I don't think that the harms is good, and I certainly hope that we had better options for people to find a graceful exit. — DA671

Or more ethically, we shouldn't put people in a bind whereby that need for a graceful exit are the choices one is put in, but this is exactly what procreation does ("deal with it" or "comply or die").

Nevertheless, I don't think that one should decide to arbitrarily impose a pessimistic view that leads to the cessation of all that matters. — DA671

But the point is if no one is born, no one is imposing anything on anyone. Not true if someone is born.

Love, beauty, and the pursuit of knowledge matter to a lot of people—definitely a lot more than a "game" — DA671

Doesn't matter if not born in the first place.

and it isn't fair to pull the plug on the basis of a perspective that's not true for billions of people, many of whom deeply value their lives in spite of the existence of harms. — DA671

People not born, don't care if they aren't born. This is all, literally, nonsense. You are not obligated to create new people that experience happiness.. It would certainly be a misjudgment to create people that experience bad things, even if your goal was for them to experience happiness.

"Oh yeah, I can tell that you have deluded yourself into loving your life even though you've suffered a lot, but I don't think that your life needs to be created (if it didn't exist), so it's still acceptable if you didn't exist at all (yet it's obligatory to prevent negatives that don't lead to a tangible better outcome for an actual person, which means the "good" coming from that prevention is an abstract one). — DA671

No, that is not it. Rather, if you are already born, doesn't apply.. So for a future person, no person will exist to be harmed, and no person exists to be deprived of happiness either. Don't convolute the point by mixing in people who exist already.

If it's obligatory to prevent harms that nobody was desperate to avoid in the void, I believe that it is also necessary to ensure that the good in the world is conserved. — DA671

Separate point, so irrelevant to the argument.

Still, I am sorry if my comments came off as being callous towards the reality of suffering. As someone who has struggled with illnesses for much of my younger years, I am aware of the fact that it is a grim reality that isn't addressed properly, particularly in a self-centred society. I advocate for a liberal RTD (along with transhumanism) because I do want the harms to end, and I am hopeful that, provided we work together, we can eliminate most forms of extreme suffering. — DA671

Cool. I'm glad you are understanding of the suffering, and are for trying to reduce it. I just think there is no reason to start it for another person, especially in light of no collateral damage to that person for not starting it, and that "good and value" don't exist as an independent entity that needs to be "fed" by the pain of yet more humans. -

Global warming and chaosI don't think that it's rational to believe that not preserving the good is somehow not problematic. — DA671

Rational is another slippery use of language. Why isn't it "rational"? I explained how it correlates to no actual person experiencing deprivation of happiness (no collateral damage to a person) and thus I think is "rational".

If someone exists, they can be happy. My point is that not creating a person does not create the opportunity of an immense good for a person (since they don't exist). — DA671

And that loss matters to whom?

However, creating them can also lead to goods, even if there would be negatives. — DA671

And right there is the very step that I am questioning is "good" and indeed think is not ethical.

I believe that the moral choice is to minimise harms and to increase the goods. — DA671

That is irrelevant in the procreational choice. Perhaps as a heuristic after birth, sure. But no one is obligated to create "goods" (since no one exists to be deprived) and certainly it is wrong to unnecessarily create inescapable, non-trivial harm for others, de novo/ex nihilo. -

A CEO deserves his rewards if workers can survive off his salary.) than their lack of not knowing what is going on in the world. I guess one could argue that there is a large gap between those that struggle to survive because they have less time and energy to invest in knowing what is going on around them and the fact that those with money and power have the ability to do things like push out propaganda that suits their needs, donate/bribe politicians, and buy media outlets to control access to what the masses are able to know; however all of this has been going on since around the beginning of the industrial age so I believe it is more of an underlining or ongoing problem that something "new". — dclements

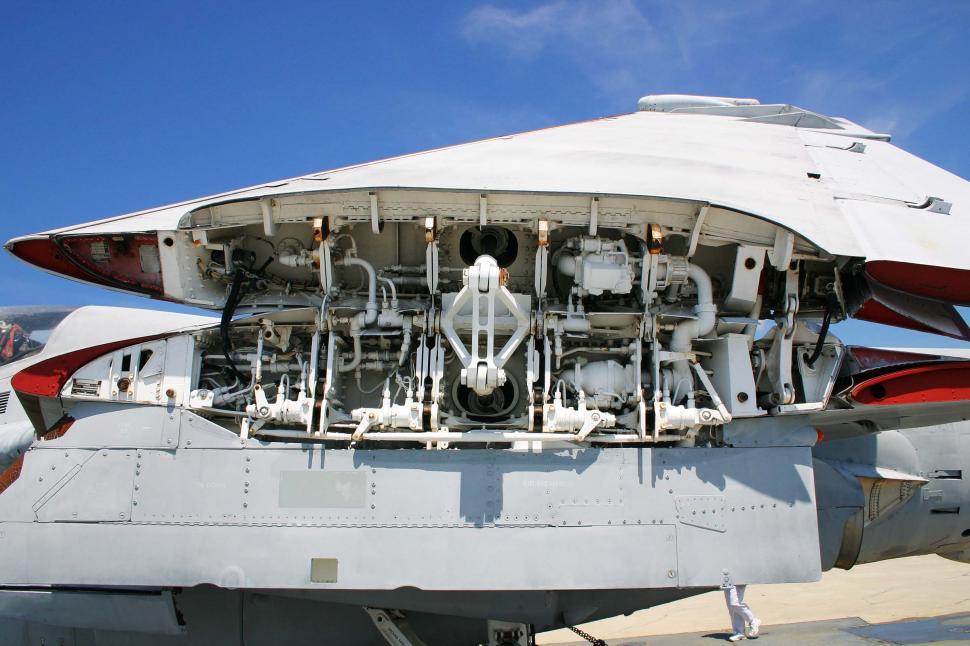

So, I'm not talking about access to political information or even general knowledge on how technology works. But literally be able to make and produce items. Can you design and produce a transmission, for example? Nope, that would rely on the expertise of other people who know far more and are probably paid quite handsomely for it.. You would need to be involved in a whole litany of supply chain networks that you have no access to. It is to be distributed and doled out to the consumer and to their workers by the gods of car distribution (aka boards and owners of car companies). -

Global warming and chaosPerhaps some other people would do well to not project their pessimism onto others ;) I wouldn't wish to derive happiness out of ceasing all valuable experiences.

The suffering also doesn't mean anything on its own. However, it does have significance for those who exist, just as the positives do. If nobody exists, there isn't anybody in the void who benefits from the absence of harms. If the lack of suffering would be good, I believe that the presence of happiness is also better (in an abstract sense, of course). — DA671

This is linguistic nonsense to get around this simple fact:

If no one exists, no one suffers. Put a value on that of what you want (good, bad, neutral). If someone exists, someone suffers. The value part comes in when you as the parent/already existing person processes this and makes an action or inaction from it. So the parent decides that no one will suffer when they could have. My point is, this inaction (to not procreate), has no collateral damage to an actual person (as they are not born). However, an action (procreating) will create collateral damage, as there will actually be a person that suffers, whatever other good that comes from it. I think the moral choice is to prevent that suffering, and am pointing out that there is no collateral damage either.

The basis for this is basically that it is never good to cause unnecessary suffering (in the first place) that is not trivial and inescapable unless extreme measures are taken (like starvation or suicide). It puts people in a bind of comply or die as well (if you don't like the "rules of the life game" you must "deal with it and go fuck yourself if you don't like it"..aka commit suicide).

On the flipside, it is not morally obligatory to create happiness de novo (ex nihilo) for someone else, especially since no one exists already to need happiness in the first place and that happiness comes with collateral damage of suffering. -

Global warming and chaosAlthough I don't believe that it's always wrong to procreate (since I believe that it can be good to preserve the ineffably meaningful experiences of life, just as it would be good to eliminate the bad ones) — DA671

I don’t think ineffably meaningful experiences on its own means anything. It’s not an entity onto itself. If no human exists, there is no person that exists that is missing out on anything, including meaning. It would only be a parent projecting their misplaced sadness on a thing that doesn’t exist. -

Not knowing everything about technology you use is bad@Pantagruel and @Ciceronianus and @Bitter Crank The Wikipedia article on Marx' idea of alienation actually does align quite well with what I'm saying, for what it's worth. See here:

In the "Comment on James Mill" (1844), Marx explained alienation thus:

"Let us suppose that we had carried out production as human beings. Each of us would have, in two ways, affirmed himself, and the other person. (i) In my production I would have objectified my individuality, its specific character, and, therefore, enjoyed not only an individual manifestation of my life during the activity, but also, when looking at the object, I would have the individual pleasure of knowing my personality to be objective, visible to the senses, and, hence, a power beyond all doubt. (ii) In your enjoyment, or use, of my product I would have the direct enjoyment both of being conscious of having satisfied a human need by my work, that is, of having objectified man's essential nature, and of having thus created an object corresponding to the need of another man's essential nature ... Our products would be so many mirrors in which we saw reflected our essential nature.[2]" — Marx

The design of the product and how it is produced are determined, not by the producers who make it (the workers), nor by the consumers of the product (the buyers), but by the capitalist class who besides accommodating the worker's manual labour also accommodate the intellectual labour of the engineer and the industrial designer who create the product in order to shape the taste of the consumer to buy the goods and services at a price that yields a maximal profit. Aside from the workers having no control over the design-and-production protocol, alienation (Entfremdung) broadly describes the conversion of labour (work as an activity), which is performed to generate a use value (the product), into a commodity, which—like products—can be assigned an exchange value. That is, the capitalist gains control of the manual and intellectual workers and the benefits of their labour, with a system of industrial production that converts said labour into concrete products (goods and services) that benefit the consumer. Moreover, the capitalist production system also reifies labour into the "concrete" concept of "work" (a job), for which the worker is paid wages—at the lowest-possible rate—that maintain a maximum rate of return on the capitalist's investment capital; this is an aspect of exploitation. Furthermore, with such a reified system of industrial production, the profit (exchange value) generated by the sale of the goods and services (products) that could be paid to the workers is instead paid to the capitalist classes: the functional capitalist, who manages the means of production; and the rentier capitalist, who owns the means of production. — Wikipedia

The worker is alienated from the means of production via two forms: wage compulsion and the imposed production content. The worker is bound to unwanted labour as a means of survival, labour is not "voluntary but coerced" (forced labor). The worker is only able to reject wage compulsion at the expense of their life and that of their family. The distribution of private property in the hands of wealth owners, combined with government enforced taxes compel workers to labor. In a capitalist world, our means of survival is based on monetary exchange, therefore we have no other choice than to sell our labour power and consequently be bound to the demands of the capitalist. — Wikipedia

The Gattungswesen ('species-essence' or 'human nature'), human nature of individuals is not discrete (separate and apart) from their activity as a worker and as such species-essence also comprises all of innate human potential as a person.

Conceptually, in the term species-essence, the word species describes the intrinsic human mental essence that is characterized by a "plurality of interests" and "psychological dynamism," whereby every individual has the desire and the tendency to engage in the many activities that promote mutual human survival and psychological well-being, by means of emotional connections with other people, with society. The psychic value of a human consists in being able to conceive (think) of the ends of their actions as purposeful ideas, which are distinct from the actions required to realize a given idea. That is, humans are able to objectify their intentions by means of an idea of themselves as "the subject" and an idea of the thing that they produce, "the object." Conversely, unlike a human being an animal does not objectify itself as "the subject" nor its products as ideas, "the object," because an animal engages in directly self-sustaining actions that have neither a future intention, nor a conscious intention. Whereas a person's Gattungswesen does not exist independently of specific, historically conditioned activities, the essential nature of a human being is actualized when an individual—within their given historical circumstance—is free to subordinate their will to the internal demands they have imposed upon themselves by their imagination and not the external demands imposed upon individuals by other people. — Wikipedia

In the classless, collectively-managed communist society, the exchange of value between the objectified productive labour of one worker and the consumption benefit derived from that production will not be determined by or directed to the narrow interests of a bourgeois capitalist class, but instead will be directed to meet the needs of each producer and consumer. Although production will be differentiated by the degree of each worker's abilities, the purpose of the communist system of industrial production will be determined by the collective requirements of society, not by the profit-oriented demands of a capitalist social class who live at the expense of the greater society. Under the collective ownership of the means of production, the relation of each worker to the mode of production will be identical and will assume the character that corresponds to the universal interests of the communist society. The direct distribution of the fruits of the labour of each worker to fulfill the interests of the working class—and thus to an individuals own interest and benefit—will constitute an un-alienated state of labour conditions, which restores to the worker the fullest exercise and determination of their human nature. — Wikipedia

@Bitter Crank, This last paragraph about "un-alientated state of labour conditions".. What does that really mean in concrete terms? What would "restoring the worker to their human nature" look like, and how would coercion not be a part of making that person do their "duties" as "worker"? That coercion seems to be something kind of left out.. Marx must have thought humans really dedicated to any activity they do.. If left to their own devices without threat, humans tend to wander off and do their own thing.. Having them labor at some project for the "communist collective" doesn't seem like enough of a motivator for most people. Capitalism has the advantage of "You don't get your living needs met if you don't do what we want (you get fired)". Would perhaps the satisfaction in "knowing the means of production" somehow factor into it? -

Not knowing everything about technology you use is badCan we have a healthy and integrated society where there is sharp division between the majority who use the tools, and the minority who understand and develop them? — Pantagruel

Yes, that is a good way of rephrasing the question. Apparently, this society we are in is supposed to represent that healthy society by people like @Ciceronianus give or take some regulations or whatnot.

However, I think there is a sort of alienation going on between the consumer and the gap between that which is produced. I don't think that will ever be resolved though. Luckily, I am an antinatalist. I always have a ready solution handy.. don't procreate more alienation and replicate the current condition unto another. Other than that, unless we become AI with our memory and can store millions of units of information, we will always be passive consumers who only produce that which is allotted by our corporate owners so that they can make profit selling to other consumers. We will always be passive consumers in our own living situation as it would be impossible to give you the means to produce this monitor I am looking at, this keyboard, the carpet, the concrete, the metals that go into the structures and the electronics, etc. etc. -

Not knowing everything about technology you use is bad

Here is also more what I am getting at with the power dynamics thing:

So I am in alignment with what you are saying, but I guess I am looking at it from a different angle than traditional left politics. So I notice that you mention wealth and taxes and profits. Well, much of these are held up in stocks and such.. so spreading around the wealth would mean a lot of times, spreading around the stocks, which just means more people holding stocks in corporations, etc. However, I am trying to get at it not just as an inequality of wealth (the traditional model), but an inequality of information. So this definitely is more in line with Marx' idea of controlling means of production, but it emphasizes not just some sort of public "ownership" but public knowledge of how things work. In other words, we are alienated from the technologies that make our stuff, and we are rendered helpless consumers because of this. We are literally doled out only the portion of knowledge necessary to keep the corporate/business owner interests going. We can read up on stuff sure, but we will never actually have any technological efficacy because we lack access to the actual technology. We can maybe make do with hobby projects like using a Raspberry Pi or something like that, but this is not the same.. It is a simulation of that technology and makes little impact on how people live in the world. I am not sure if this is making sense. — schopenhauer1

It's not that I am anti-technology in the way you think. Rather, it is the consequences of being alienated from that which sustains us. related but perhaps not quite the same as what @Pantagruel is saying, technology is human created, and thus the affront to our alienation is human-created. We are doing this to ourselves, from ourselves. Can the information-distribution problem ever be different? If not, there is a serious problem, to me in terms of our relation to ourselves, one of a sort of alienation.

I understand your point about specialization and people throughout centuries not knowing the basis of the technology they use. I'm not saying now is different.. It does seem to be a part of what it means to use technology- that you are relying on someone else's knowledge and means to produce the technology. The computer programmer, mathematician, engineer, and scientist who often produce minute portions of this vast knowledge, often get where they are because they have a capacity (and probably inherent skill) to work with a lot of rather boring minutia. Their reward is getting first-hand production capacities in the means of our survival and daily living. However, this is exactly the model I am balking at. I am not concerned with the efficiency of how owners use engineer-types to create technologies to sell to the consumer. I understand this, but it is exactly this current model which is alienating in a sense. I know you don't find it to be so, but I do think this to be a problem whereby we can never fully grasp our own means of survival, and that we are basically reduced to doled out workers (on a minute area) and consumer. -

A CEO deserves his rewards if workers can survive off his salaryIn many ways it is worse that what I argued and you said, the system has always been a bit lopsided toward the rich but it is getting more so each year. Corporations no longer pay the lion share of the taxes through profits (instead it comes from wages), and it seems like the power people have through voting and/or other means hardly makes a difference anymore. i don't have the time right now, but in the next day or so I will research and look through some of my old stuff to find various links and YouTube videos might shed a little more light on this issue then I can by myself. — dclements

So I am in alignment with what you are saying, but I guess I am looking at it from a different angle than traditional left politics. So I notice that you mention wealth and taxes and profits. Well, much of these are held up in stocks and such.. so spreading around the wealth would mean a lot of times, spreading around the stocks, which just means more people holding stocks in corporations, etc. However, I am trying to get at it not just as an inequality of wealth (the traditional model), but an inequality of information. So this definitely is more in line with Marx' idea of controlling means of production, but it emphasizes not just some sort of public "ownership" but public knowledge of how things work. In other words, we are alienated from the technologies that make our stuff, and we are rendered helpless consumers because of this. We are literally doled out only the portion of knowledge necessary to keep the corporate/business owner interests going. We can read up on stuff sure, but we will never actually have any technological efficacy because we lack access to the actual technology. We can maybe make do with hobby projects like using a Raspberry Pi or something like that, but this is not the same.. It is a simulation of that technology and makes little impact on how people live in the world. I am not sure if this is making sense. -

Not knowing everything about technology you use is badI mean, idk I think there is satisfaction that can be derived from understanding how something works, even if it is a broad, general understanding and not a detailed one. I think the question I'd raise to you is to explain why you think a technological device like a computer is inhuman, but the physical-chemical-biological systems of the natural world are not...unless you think they are inhuman as well?

I'm not disagreeing with you, I just want to know what your thoughts on this are. The vast technological orchestra is frequently nauseating to me too, yet the vast natural orchestra is not (at least sometimes). Why is this? — _db

I think you were getting at it with helplessness and no one having full knowledge. You may know this element but not that element. It becomes a rabbit hole of a rabbit hole of a rabbit hole. Even knowing some things about networking.. you will never know the full extent.. It is this endless feeling of being excluded.. Then you just throw up your hands and watch those insidious self-reinforcing algorithmed videos on social media that @Bitter Crank talks about.. It's like the vastness of the technology lulls you into a stupor that also sort of gives you inertia.. At that point, you just give in to the companies that are providing your needed technology.. And you just consume, work, and don't think too hard again about it. Let the companies dole out your product without any knowledge of all the things that went into what you use. Someone mentioned magic.. it really is no better than medieval mentality.. The ignorance of that which sustains us in our survival, entertainment, comfort and the like. -

Not knowing everything about technology you use is badI dare say, the "real" is "techne". Everything else is frivolous fluff that gets a ride on the real and is allowed as long as the real gets done first. At the end of the day, your thoughts on this or that don't matter.. What matters is the techne. Everything else becomes irrelevant and dissolves away.. The captains of industry are the serious ones as long as they are making techne. The engineers and scientists and the like that are producing tangible techne...Everyone else are just flotsam and jetsam only necessary in the consumption and demand of such real items of the world.

-

Not knowing everything about technology you use is badThe lords hold the power to produce by means of law, coercion, secrecy, deceit, et cetera -- not because they know how to manipulate magic. The economic arrangement can be changed, if the workers decide to collectively act to change it (e.g., revolution). — Bitter Crank

I think I agree. But as you say here:

How I hate having to deal with minutia and minutia mongers. I am strictly a big picture man. "Don't ask me where that little screw went --the question is, "Will we make it all the way to Mars and back?" — Bitter Crank

The latter can't happen without the former. We need minutia mongering on all fronts. First, we need thought-based minutia-mongering.. the engineers designing those screws and cranking equations. Then we need machinists mongering the minutia of interlocking parts. Then we need the industrial proletariat to crank out as many parts as possible on mass quantity. We need the service technicians to monger the minutia involved in fixing these small parts.

We don't need the humanity guy pondering life on mars, Bitter.. As much as we like talking to that guy.. we NEED the guy who knows how monitors can work and the knowhow to produce it. Minutia is cold, void of humanness but necessary. It is the little cog, that turns the other thingy for this thingy to cause this doodad to oscillate that widget, and so on and so on. -

A CEO deserves his rewards if workers can survive off his salaryDo you think it is more likely that the kings and priests who are being used/ under appreciated/ exploited or do you think it is more likely peasants, labors, and/or "untouchables" who are being treated in such a way. Again I could be wrong about such parallels existing between the India and Western caste/class systems, but if you do agree that they do exist I think you can see the fallacies that arise when those on the top of a caste system try to argue that they are the one's being "exploited". — dclements

So my whole argument here is a sort of devil's advocate. I started another thread perhaps truer to my own philosophy.. that the fact that we don't understand the technology we use is a sort of alienation on various fronts that allows for exploitation of the keepers of the knowledge.. I am sort of mocking the system whereby people must crawl to another fiefdom of technology-hoarders to dispense little pockets of productive activities for the workers, so that they can consume and make other technology-hoarders (uh, producers), money and so on.. -

Not knowing everything about technology you use is badAs with any habituated behavior (smoking, drinking, eating potato chips, mindlessly switching channels, endlessly surfing the net) we have to make a decision to do it less or stop doing it at all. I'm not suggesting people should stop using their phones and computers to access social media and on-line companies, but one can and should reduce the frequency of use. — Bitter Crank

Absolutely.. This is a known insidious outcome of targeted algorithms. It's hard to stop, like a merry-go-round because they know your likes better than you now ha.

But I think there is something to be said about the disparity of those who have the means to produce and those who just consume.. But I don't want to bring in dynamics of simply capitalists vs. proletariat, as I think it is a bit different. It is knowledge-capitalists, technicians, minutia-mongerers.. The finance people are nominal and expendable. They are nothing without the real knowledge-keepers. -

Not knowing everything about technology you use is badI'm under the impression the OP is thinking about this in more general, even "metaphysical" terms. Ie. when one's survival depends on things one doesn't understand, one is profoundly vulnerable. — baker

In a way yes. I did relate back to power dynamics. I think there is something about having the means to produce an important item for someone else and then just passively consuming that item.

However, yes the metaphysical not being able to access fully that which sustains us, is something that I am trying to get a better understanding of. -

Not knowing everything about technology you use is badChances are fairly good that I know a lot more about the practice of law than most others gracing this forum. That gives me an advantage--in practicing law and knowing how the legal system works. Doctors have an advantage over others when it comes to knowledge of and the practice of medicine. Plumbers have an advantage when it comes to plumbing. Do these entirely commonplace, unsurprising forms of power dynamics disturb you as well? — Ciceronianus

It's the fact that the lords hold the knowledge and means to produce the things we need.. That is real power. There is more power in being the producer than the consumer. -

Not knowing everything about technology you use is badCheck out the movie "Don't Look Up" if you haven't already seen it. It is a hilarious (and frightening) look at people enslaved by their own tech. — Pantagruel

I saw it, and it is good. But that is just the consumer side of it. It is more like, the deficit of those who use and those who produce the technology...It is touched upon a little on the movie between the scientists and the overly-consumed by their technology/media human citizens though and especially the Steve Jobs-like guy and his technology. There is a huge amount of disconnection and deficit between the two. -

Not knowing everything about technology you use is badTechnology can only be used optimally to the extent it is understood. Or to the extent that it's use is directed and controlled by those that really understand it, I guess.... — Pantagruel

I just think there is a huge power differential regarding the people that know the technology and those that just consume it. I think it is this that is the real political-economic power in the world- who understands and can produce the technology. I think the focus on capital is misplaced because it is more about the finance behind something or the resources one is using. It is the knowhow and the means to use the knowhow.. It is I think different than starightup capital.. and perhaps economics should be more rooted in this understanding rather than 19th century uses of the word "capital" which we seem to be stuck in when explaining economic models. -

Not knowing everything about technology you use is badIs there something like the fantasy of an ideal adult that is frustrated here? Even our 'visionary' tech billionaires are riding on the back of a beast they can't control or understand. Some of us have tiny maps of the abyssal territory that are just a little less tiny than the maps of others. — ajar

Very true. -

Not knowing everything about technology you use is badLet's start in the inner workings of our brain and intuition. It's powerful. — Caldwell

Not sure what you mean, but we have produced all the minutia.. The minutia which sustains.. -

Not knowing everything about technology you use is badAs someone who works in the computer industry I can safely say that the technology is not well-known amongst the engineers that are thought to understand it. — _db

May I ask what your role is specifically?

That is one of the things that is so fucking sinister about modern technology, nobody understands it in its entirety, nor can they manufacture it themselves. Every technician understands a part, and even then they don't need to understand it as much as they just need to know how to use it. And if a person were to come close to grasping all of what goes on inside a single computer model, it would only be by an immense sacrifice of everything else in their life. — _db

Right, and then they don't even know how that cup was made or the chair they sit on.. and back to square one :lol:.Well I think it certainly has something to do with Marx's notion of alienation, being reduced to a cog, a button-presser, the maintainer, etc. Humans did not evolve to do this sort of crap, it goes against our natural state of being. There's this blind, amoral force of technique that drags us along in its current of relentless improvement of efficiency, whether we like it or not. — _db

Yes, for sure we are alienated from the production that makes us survive and from meaning in the work (often stretching it to be meaning in the meaninglessness or Sisyphus or Kafka or Office Space or whatnot). But there is something else.. this dialectic is getting closer, but not quite hitting it yet...

1) We are born to forces that we know little to nothing about. Patents, manufacturing knowledge, electro-mechanical-materials-structural-engineering, chemical, biological, medical, etc. etc. But I'd like to harken back to my minutia-mongering neologism. Technology parses to a degree of such minutia. The minutia is blindingly boring. There is a drowning weight to it.. Just how the internet works alone or code language, or engineering blueprints.. There is something deadeningly inhuman.. Yet it is what sustains.

2) The power differential of those who hold the technology and those who don't. Those who know more and those who don't. Those who know more and have the means to produce it and those who don't. Imagine if how we distributed resources was knowing how each item you consumed worked.. No one could consume the item. -

Not knowing everything about technology you use is badAlthough we've used technology of various kinds for millenia, it seems to me that only recently, relatively speaking, have some of us come to believe that technology renders us somehow divorced from "reality" and "being" or some-such in what strikes me as a hyperbolic, Romantic, quasi-mystical manner a la Heidegger with his talk of hydro-electric plants as if they were monsters, or our coercing the world to do what we please, summoning forth the power of the sun (I forget what he condemned so excitedly). He compared it to the peasant lovingly planting seed in Nature's bosom, if I recall correctly. There was a chalice too, I believe. Chalice good, coal bad.

Technology presents real problems, but I suggest some restraint when it comes to contriving metaphysical and epistemological horrors arising from the fact that we don't know how to make certain things. — Ciceronianus

Technology commands us.. We consume it, and yet we don't know it. There is at least some form of power dynamics that comes from being excluded from that which we survive from. -

Not knowing everything about technology you use is badAnd speaking of cells, consider also that our bodies themselves are more complex machines than our spaceships or our computers. So even the caveman depends on that which he does not understand. He's just ignorant of his ignorance. — ajar

Good point..even our own basis of life is hidden to some extent. However, unlike natural causes, technology is man-made and yet it eludes most men, though they use it. -

Not knowing everything about technology you use is badOur technology has advanced exponentially while the species has hardly evolved. This seems to me a fundamental problem. — NOS4A2

I would imagine our cultural evolution is part of what makes our species survive, so that seems to make sense. -

Not knowing everything about technology you use is badBeing self-sufficient seems like it is an important quality of a mature human being. It seems to me that there is something fundamentally repulsive (pathetic) about not being able to take care of yourself when you ought to be able to. Not understanding the technology we use and being unable to live without it makes realizing this quality of self-sufficiency impossible. — _db

Yes this! You are very close to what I'm trying to say.. But there is something even more troubling than it being pathetic and repulsive to not be able to take care of yourself. Here I am using a computer in which I only know a vague understanding of certain things but for which the technology is well known amongst electronic and computer engineers. And monitors and their displays, a rudimentary knowledge but relies on so many intricate parts and concepts coming together. The plastic that encases the computer, the silicon chips, the copper wires and, even what the basis for the green in most PCB boards.. All of it requires millions and millions of minutia-knowledge that I can never fully comprehend.. And even if I did, all the minutia that is adjacent to that , and to that, and to that.. What is it about this behemoth complexity upon complexity that seems to subsume ones own efficacy? It is pathetic our reliance but inability to know all of it.. But it is more than that. -

Not knowing everything about technology you use is badas this knowledge is for the chosen ones only — Raymond

No, this isn't ridiculous.. There does seem to be a tier that knows more.. But even they only know more in their specialty. It would be very hard for a biotechnical engineer to understand mechanical engineer to understand an electronic engineer to understand a material engineer and so on..Though if given time, it would be easier for them to understand each other than someone with no background... they all need some basic sampling from each in undergrad at least and complicated enough maths for differential equations and Calculus III, statics, and such. -

Not knowing everything about technology you use is badTrust is implicated here. There is too much for any single person to know about technology. I trust the vaccines work. I trust the brakes on my car work. — emancipate

Yep, certainly in a practical sense, not knowing how a technology works, relies you to trust what others know... It is still beyond that. It is more than just, "I hope this mechanic knows what he's doing". It's more like not understanding the minutia of the metals used to create the parts of your engine. The amount of minutia we are not aware of, but rely upon is dizzyingly vast. The amount of patents, the amount of machine parts, the amount of even one ounce of what went into modern products.

I am not sure if this is relevant, but it seems to draw parallels with what Graham Harman was discussing in an object's interaction with other objects. They never "know" fully the depth of that other object, only how it interacts with it..

Harman defines real objects as inaccessible and infinitely withdrawn from all relations and then puzzles over how such objects can be accessed or enter into relations: "by definition, there is no direct access to real objects. Real objects are incommensurable with our knowledge, untranslatable into any relational access of any sort, cognitive or otherwise. Objects can only be known indirectly. And this is not just the fate of humans — it’s the fate of everything."[10] — https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Graham_Harman

But instead of objects, rather it is knowledge of our own human world of being which is excluded from ourselves as individuals by ourselves (as a vast network of interactions). -

Not knowing everything about technology you use is badYou gotta have knowledge about everything you surround yourself with? Will it lead to disaster if you don't know? — Raymond

I don't know, that's what I am trying to find out haha. Think of it as a concept that is sort of on the tip of your tongue but haven't quite narrowed it yet. It seems to have something to do with efficacy, being alienated from larger forces that one can never be a part of, but that control you, economic implications, metaphysical implications, etc. -

Not knowing everything about technology you use is badI've said also mentioned it in an earlier comment here:

1) We use technology and items that we have no idea how they work. We are a forever behind the veil of our own mode of production and living. You are ignorant in any highly detailed way, of your own way of being and survival. -

A CEO deserves his rewards if workers can survive off his salary@Maw @Xtrix

Right, but what about these type of things? Not real? : https://www.fundera.com/blog/business-success-stories

The story of electricity is complicated, but a large part of its distribution came from Edison (with Tesla and Westinghouse continuing and improving it). https://www.nps.gov/edis/learn/historyculture/edison-biography.htm

There is the cheap automobile with Ford.. who as a person I really dislike, but he did start with little:

The company was a success from the beginning, but just five weeks after its incorporation the Association of Licensed Automobile Manufacturers threatened to put it out of business because Ford was not a licensed manufacturer. He had been denied a license by this group, which aimed at reserving for its members the profits of what was fast becoming a major industry. The basis of their power was control of a patent granted in 1895 to George Baldwin Selden, a patent lawyer of Rochester, New York. The association claimed that the patent applied to all gasoline-powered automobiles. Along with many rural Midwesterners of his generation, Ford hated industrial combinations and Eastern financial power. Moreover, Ford thought the Selden patent preposterous. All invention was a matter of evolution, he said, yet Selden claimed genesis. He was glad to fight, even though the fight pitted the puny Ford Motor Company against an industry worth millions of dollars. The gathering of evidence and actual court hearings took six years. Ford lost the original case in 1909; he appealed and won in 1911. His victory had wide implications for the industry, and the fight made Ford a popular hero.

“I will build a motor car for the great multitude,” Ford proclaimed in announcing the birth of the Model T in October 1908. In the 19 years of the Model T’s existence, he sold 15,500,000 of the cars in the United States, almost 1,000,000 more in Canada, and 250,000 in Great Britain, a production total amounting to half the auto output of the world. The motor age arrived owing mostly to Ford’s vision of the car as the ordinary man’s utility rather than as the rich man’s luxury. Once only the rich had travelled freely around the country; now millions could go wherever they pleased. The Model T was the chief instrument of one of the greatest and most rapid changes in the lives of the common people in history, and it effected this change in less than two decades. Farmers were no longer isolated on remote farms. The horse disappeared so rapidly that the transfer of acreage from hay to other crops caused an agricultural revolution. The automobile became the main prop of the American economy and a stimulant to urbanization—cities spread outward, creating suburbs and housing developments—and to the building of the finest highway system in the world. — https://thephilosophyforum.com/discussion/12347/a-ceo-deserves-his-rewards-if-workers-can-survive-off-his-salary/latest/comment

The airplane started from humble entrepreneur origins..

In 1909, when the Wright Company was incorporated with a capitalization of $1,000,000, the Wright brothers received $100,000, 40 percent of the stock, and a 10 percent royalty on every plane sold. The company developed extensive financial interests in aviation during those early years but, counter to the recommendations of its financiers, did not establish a tight monopoly.

By 1911, pilots were flying in competitive races over long distances between European cities, and this provided enormous incentives for companies to produce faster and more reliable aircraft. In 1911–12 the Wright Company earned more than $1,000,000, mostly in exhibition fees and prizes rather than in sales. French aircraft emerged as the most advanced and for a time were superior to those of competing countries. All planes built in this early period were similar in construction—wings and fuselage frames were made of wood (usually spruce or fir) and covered with a coated fabric. — https://www.britannica.com/technology/aerospace-industry/History

So that represents the incubator period.. Orville Wright made a lot of money.. But then other companies made their own and created conglomoaretes.. There's your big business height of industry phase...

The Boeing Company was started in 1916, when American lumber industrialist William E. Boeing founded Aero Products Company in Seattle, Washington. Shortly before doing so, he and Conrad Westervelt created the "B&W" seaplane.[14][15] In 1917, the organization was renamed Boeing Airplane Company, with William Boeing forming Boeing Airplane & Transport Corporation in 1928.[14] In 1929, the company was renamed United Aircraft and Transport Corporation, followed by the acquisition of several aircraft makers such as Avion, Chance Vought, Sikorsky Aviation, Stearman Aircraft, Pratt & Whitney, and Hamilton Metalplane.[2]

In 1931, the group merged its four smaller airlines into United Airlines. In 1934, the manufacture of aircraft was required to be separate from air transportation.[16] Therefore, Boeing Airplane Company became one of three major groups to arise from dissolution of United Aircraft and Transport; the other two entities were United Aircraft (later United Technologies) and United Airlines.[2][16] — https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Boeing

So Boeing came about from William making money on the timber industry? How did he do that? His dad worked in timber and was able to buy small acres and make a bit of money that way.. William took that idea and expanded it by buying even more lucrative land out in the state of Washington.. Once he had that money he didn't even have to live on premise at Washington but in Michigan. From there he could do side businesses on hobby interests of his, like flight.. those hobby interests turned into profits when he bought small airplane companies and started bringing them under one corporation. But you see, it took him doing all of this.. It didn't just "come about". -

A CEO deserves his rewards if workers can survive off his salary

Independent sources of capital were always a part of it. It’s still in the early phases before someone gets a return. People need the capital infusion and rarely have their own to grow the business unless already wealthy which is where an unfair advantage does enter into it. -

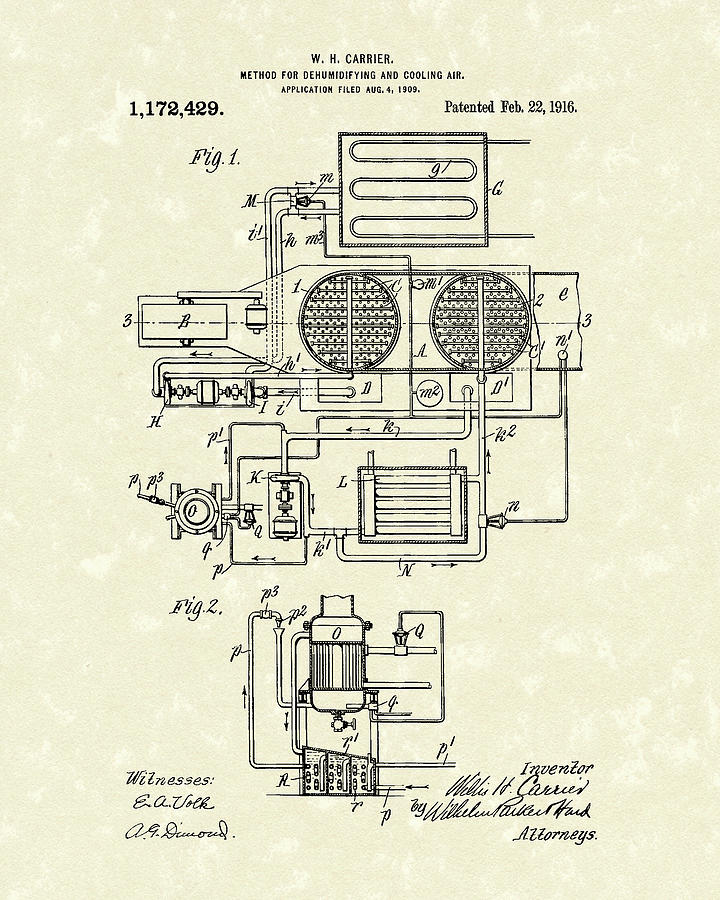

A CEO deserves his rewards if workers can survive off his salarymeans of production — StreetlightX

I can't win. I mentioned private ownership of capital the first time.. But yes, Xtrix already covered what I think you were going to mention. So I pose the same question.. Would you be for getting rid of the "capital heights of the economy" (large corporate entities run by boards, shareholders, etc.) but still keep the medium and small businesses run by single proprietors that started them? It seems that much of the anger is directed towards the really big, multinational corporate Wall Street guys more than the smaller businesses. But you did mention that there is less scrutiny so often more chances for exploitation, which I can concur does make sense in small business. But, the small businesses, are the incubators for creating the bigger ones which then become almost like public goods by being so ingrained in the lives of everyone. Take for example, air conditioners. I think that was started by the Carrier company.. Before that people didn't realize what they were missing.. they just had fans and other cooling techniques...Then air conditioning became essential in hot climates. The same goes for any of these utilities.. Edison and electrical grids.. didn't know we needed them until we needed them. -

A CEO deserves his rewards if workers can survive off his salaryHow are these corporations organized? The same relationship: owners/employers (in this case the major shareholders, board of directors, and executives) hire workers/employees. The workers generate profits. What happens to those profits? Where do they go? They go to, essentially, the "owners" -- the board of directors, who decide what to do with the money. Since the board directors are chosen by major shareholders, they usually do the bidding of the major shareholders -- and we see that demonstrated today with stock buybacks and dividends, which accounts for 90+% of profit distribution (please see the links I provided earlier, or google it yourself, as this should be a stunning statement). — Xtrix

Ok, so these more-or-less correspond to commanding heights of the economy.. i.e. utilities, raw materials, construction, large technology companies, etc. How about the medium to small businesses? Would you be good with doing away with private ownership of capital heights (the really big corporate guys) and but keeping it for smaller industries (which still make up a significant amount of the economy)? Why or why not? These smaller guys tend to be owned by a single person, a partnership, a family, etc. The company is usually managed directly or through several manager in various regions and/or departments. -

Question about the Christian Trinity

Occam's Razor here.. "Why have you forsaken, me?" was a person trying to claim the role as messiah, thinking he was actually going to succeed in some miraculous fashion, and then it did not.

Crisis for remaining followers...what to do? Appearances of apparition.. he can't be dead..

This "can't really be dead" turns into much different thing by the Book of John. Now, he is not a human messiah in the Jewish sense (political leader herald in political autonomy and depending on the group- the End Times).. he is some part of a more complicated picture more in line with geometric Greek thought. Perhaps influence from Hellenistic Judaism played a part via Paul in this, through contemporary works by Philo of Alexandria.. -

The Internet is destroying democracy

Humans tend to suck. The internet is just this presented in a hyper way. Layers of obfuscation created by the consuming of technology.. What's so great about the act of survival? What's so great about our little hobbies, friends, and family? Really, the internet is just a mirror of this lack at the center. We crave more because we cannot just be. Being and becoming are important themes here. Internet is a network of manifested obfuscation of becoming. But being is really not much better. Just thereness there.. so we diddle and daddle and doodle and dawdle. -

Global warming and chaosI think Zeus's concern, that with the technology of fire we would discover all technologies and then rival with the gods, forgetting the wisdom of the gods and thinking ourselves the ultimate power and destroying nature to satisfy ourselves, was a justified concern. We have confused technology with science and now have technological smarts but not wisdom. — Athena

Yes, but no one's going to give up the technology once they have it. You can prevent future humans from living through what you are describing though. Simply don't procreate them. Easier thing to give up and pretty darn easy these days. Procreation for most (especially who have the most technology and fund it) can be prevented. -

A CEO deserves his rewards if workers can survive off his salary

Ah yes, please enlighten me on your obviously objective version of a definition that is inherently a whole litany of aspects.. private ownership of capital, profit-oriented, free market exchange, etc.

schopenhauer1

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum