-

Are our minds souls?I don't think I misunderstand it at all. Which premise in which of my arguments are you disputing? — Bartricks

I just told you, didn't I? Why not read something about this topic if it interests you? You might want to start not with the identity theory specifically but with an overview of theories of mind, which will put things in perspective.

As for panpyschism having lots of proponents - er, no it doesn't, it just has a fancy name and is associated with a philosopher who has long hair and thinks he's a rock star.

Numbers don't mean anything, it is evidence that counts. But if you're (misguidedly) interested in numbers, then my view wins hands-down. The thesis that your mind is an immaterial soul and not your brain or any other physical thing is far and away the prevailing view among reflective people, now and throughout history. — Bartricks

You persist in misunderstanding this. "Self-evident" doesn't mean the most popular. Self-evident means that it is impossible to deny. This isn't just a quibble about words, by the way. You are too blithely dismissing positions without even trying to learn about them. That is not the attitude of a philosopher. At the very least, the fact that such positions are taken seriously by people who are not stupid or insane ought to give you a pause. -

Are our minds souls?You are misunderstanding the mind-brain identity thesis. It does not say that your mind is literally a physical object that is your brain. Rather, it says that the mind is identical to the processes in your brain, and mental states are really brain states. That should satisfy your modest requirement that the mind should not be a thing that you can touch, see, smell, etc.

That said, mind-brain identity position is not as widely held as you make it sound: it is only one of a number of physicalist theories of mind and, at a guess, not the most popular. Moreover, a dualistic soul is not the corollary of denying mind-brain identity. Again, it is only one of a number of non-physicalists positions on the mind, and again at a guess, not the most popular, at least among philosophers.

Yes, I understand what panpyschism is. — Bartricks

Then you should also understand that it cannot be self-evidently false, otherwise it would not have as many proponents as it does. -

How Do You Do Science Without Free Will?And of course free-will is tainted by its theological roots - I'm not trying to 'insinuate' this: here's me being explicit about it: free-will is theological trash. — StreetlightX

Well, thank you for being so upfront, I guess - this will save me time and effort. By giving a caricature of your position I was hoping (though it wasn't much of a hope after seeing your earlier posts) that I might be proven wrong or that I might elicit a more nuanced take. But it looks like the caricature was spot-on. Oh well.

As for concepts being 'conflated with 'that which they purport to address', wtf else are concepts if not designed specifically for address 'what they purport to address'. — StreetlightX

Fortunately, that's not what I said. -

How Do You Do Science Without Free Will?Funny how an 'innate understanding' had to be invented by theologians a couple of hundred years ago before which it was nowhere to be found. — StreetlightX

It's not contentious. — StreetlightX

It's contentious, if you care to survey philosophical literature on free will, rather than just the works of one or two authors. And no, I am not going to get into a childish flame war with you over this; I am not that interested in history and exegesis, any way. My point of contention is that you are muddying the waters by conflating the intellectual history of free will as an articulated philosophical concept (and a very specific version of that concept, if you insist on tracing it to Augustin et al.) with that which this concept purports to address. What I particularly resent is the attempt to shout down the debate by the unsubtle insinuation that the concept is forever tainted and discredited by its history as an opium for the masses that was maliciously concocted by theologians. You can be critical and revisionist about free will without being stupid and dogmatic. -

My notes on the Definition of Mathematics.analytic truth truth by virtue of the meaning of the words of a statement, synthetic needs meaning and correspondence with reality as well. Here with this terminology I'm speaking about rule following which can even be of strings of empty symbols, so meaning is not involved here, however synthetic seems to be overlapping with receptive truths. I think that analytic is "meaningful consequential truths", so I think the term "consequential truth" is weaker than analytic truth, although of course you can object to this by holding that consequential truth is a kind of non-meaningful analytic truth or by saying that rule fellowship is a kind of meaning, you can call it meaning by having a role in following a rule, if so then we can subsume consequential into analytic. The new things is that KANT was saying that mathematics is apriori synthetic. Which this philosophy doesn't agree with. I more agree with Hume that mathematics is purely analytic nothing else. — Zuhair

Right, so your receptive/consequential distinction falls approximately along the same line as Hume's matters of fact vs. relations of ideas, which is now often aliased as synthetic/analytic, although one can certainly split semantic hairs and introduce further distinctions, like Kant's a priori/a posteriori. (For that matter, Hume's own treatment of relations of ideas amounted to more than just rule-following.) In any event, this is a well-trodden path - I was just wondering whether you thought you were bringing some fresh perspective and not just your personal terminology.

The idea that all there is to mathematics is manipulation of symbols according to fixed rules is true only within a comparatively limited, 18th century conception of mathematics, when mathematics was the mathematics, and it sprang from the same source as logic and rationality itself. Since then we have significantly broadened our ideas of mathematics - and for the matter, of logic and rationality as well. This is what @fdrake is getting at: the more interesting questions in the philosophy of mathematics revolve around the rules themselves, rather than the uncontroversial fact that conclusions can be deduced by following those rules. -

My notes on the Definition of Mathematics.That's a lot of words, but I am kind of struggling to understand what it is that you think is the original thought here. How is your receptive/consequential distinction different from synthetic/analytic, etc. - what has become known as "Hume's fork" (and has since been deconstructed and criticized by Quine, etc.)?

-

How Important is Reading to the Philosophical Mind? Literacy and education discussion.Unfortunately, the only Hugo I've read is "Les Miserables," which I read in French in high school. — T Clark

That's some assignment!

I read Notre-Dame de Paris as a teen, and even at that age his overwrought romanticism turned me off. The shear bulk of Les Miserables scares me. Not that I am intimidated by big books in general, but five volumes of that kind of prose... -

Bias against philosophy in scientific circles/forums"What it means" is where conceptual issues begin and end. What did you think I meant? Specifically with regard to causality, since that was the context, the issue is pretty controversial in QM. As you know, cause is not really a term in QM's vocabulary (and the same can be said about most areas of physics), so it is all about interpretation.

-

How Important is Reading to the Philosophical Mind? Literacy and education discussion.Certainly. Sorry if I've misunderstood you.

-

How Important is Reading to the Philosophical Mind? Literacy and education discussion.Reader here. I read every day, though since I am a slow reader, I don't cover nearly as much ground as some. I don't have a good idea of how much other people outside of my small social circle read, so I can't really compare myself to others. I take no personal credit for my literacy - it was inculcated in me by my parents.

I read mostly fiction - "serious" literature, with a bit of light fare for when I am too exhausted or distraught for more demanding stuff. I rarely read book-length non-fiction - I just don't value most of it enough to prioritize it over fiction. I was a bit surprised to see @Amity and others referring to reading fiction almost as if it was cheating at reading. On the contrary, I have always associated "reading" with fiction books, first and foremost.

Shakespeare’s language is, of course, “dramatic” stage language. It doesn’t make for easy reading. — Bitter Crank

I actually find Shakespeare's dramatic "high" style easier than his "low" style - all that witty banter, in which most of the witticisms and sexual innuendos you wouldn't even understand without a commentary that runs twice as long as the text itself. I think I learned (and have long since forgotten) a dozen euphemisms for penis and vagina while reading an annotated Much Ado about Nothing (starting with the title, of course). In Henry IV I struggled with Falstaff's scenes, uproarious though they might be, but when I would get to some princely monologue - whew! Smooth sailing at last! Here I could read a few lines without consulting notes. -

Bias against philosophy in scientific circles/forumsNow of course this is a single interaction. — Coben

Which is impossible to judge based on the retelling of one of the participants. For all I know, you could be right, but to a rational observer who knows only that the argument was between a non-expert with a superficial familiarity with the research and the experts who conducted the research (because even before you squabbled with someone on a forum you were in a virtual argument with the authors of the studies in question), the balance of credibility is obviously not in your favor.

But that's not the important point. What was the point of this anecdote?

I just bring it up because it is a sort of classic philosophy/science encounter. — Coben

From what you have told us, it appears that the "classic encounter" consists of you presuming that scientists in general would not know anything about isolating principal causes of a phenomenon while accounting for relevant confounders. How could they, indeed? After all, 'cause' is a philosophical term of art, so they need an amateur philosopher with little knowledge of the subject matter to set them straight.

What is particularly perplexing about this encounter is that as a philosopher you weren't problematizing a concept that is commonly taken for granted, or bringing to light an unexamined assumption, or suggesting a different conceptual framework. Rather, you were challenging the science on its own turf - perhaps without even realizing that that is what you were doing. It could be that the researchers did not do a good job of accounting for all relevant factors and evaluating alternative hypotheses - I don't have enough information and expertise to judge. But that is precisely what is expected of them as scientists.

How do you think philosophers theorize about causality? How do they evaluate their own theories? They systematize and generalize causality by examining our causal thinking and practice. But toy examples like billiard balls colliding or stones smashing windows can only get you so far. Scientific practice provides a large pool of complex examples, from Newtonian dynamics to epidemiology, and here philosophers mostly learn from scientists, rather than the other way around. If a philosophical account of causality is contrary to the best scientific practices, this is usually taken to be philosophy's deficiency.

That is not to say that philosophers cannot contribute to the discussion of causality, but that would be more in areas where science runs up against conceptual difficulties, such as in quantum mechanics, for example. As for routine problems with the quality of studies and such, scientists and mathematicians are more adept at debugging those than most philosophers. -

How Important is Reading to the Philosophical Mind? Literacy and education discussion.I thought Hugo was a Republican. — Bill Hobba

LOL you guys. Yeah, you could say that Hugo was a republican, though not in the way you think. -

Reductionism in EthicsHave you heard of "blogs"? It's a hot new thing on the Internet - you should check it out!

-

Bias against philosophy in scientific circles/forumsFrom my perspective, what you say is mistaken. Any area with a mental component has philosophy somewhere in its foundations, if you grub around enough to find it. How could it possibly be otherwise? — Pattern-chaser

Did you read just this last sentence? I don't deny the value of philosophy, nor even its applicability to science. -

Bias against philosophy in scientific circles/forumsSomebody in this thread said that part of the reason philosophy is looked down on by scientists is that the philosophers don't do or understand science. — T Clark

This situation is changing though. Just as science is no longer the province of gentlemen dilettantes, as it was until about the mid-19th century, philosophy is catching up and becoming more professional and specialized. It is not uncommon now for philosophers of science to have an honest-to-goodness science degree. And while such a formal degree is not a prerequisite for doing good philosophy, I believe that only those philosophers who demonstrate a decent grasp of their subject deserve to be taken seriously.

We should turn that around too, make people understand that so-called scientists who don't understand the intellectual underpinnings of what they do are just technicians. — T Clark

Some people here tend to arrogantly overestimate their understanding of science and scientific process and underestimate scientists' intellectual abilities. It is easy enough to find examples of uninspired or incompetent science (provided that you have the competence to judge!) just as it is easy to find examples of uninspired or incompetent carpentry, and for pretty much the same reason: when something is so ubiquitous, it can't all be excellent. (And how much excellence does hammering a nail require, anyway? A lot of research is basically hammering nails.) But there have always been outstanding intellectuals working in science, who could give the best of philosophers a run for their money, even if they didn't spend much time poring over their Aristotle and Kant. Frankly, the conceptual riches that have opened up in science and mathematics over the last 200 years make a lot of philosophy look shallow and insignificant in comparison.

I am embarrassed for those "philosophers" (not talking about you, T Clark) - nitwits and crackpots who come here to sneer condescendingly at the Borns and the Feynmans - those benighted bunglers! If only they listened to our sophomoric insights, science wouldn't have been in such a hot mess that it is nowadays! If any self-respecting scientist happened upon this forum, she would tell them where they can stuff their philosophy - and would be absolutely right. Philosophers need to step up their own game if they want to be relevant. -

Bias against philosophy in scientific circles/forumsBeyond that, the question in science is rather: How did you test that? How did you take care of scientific controls? Has anybody else tested it again? These anti-spam measures neatly hark back to Popperian falsificationism, which in my impression, still rules as king over the epistemic domain of science. — alcontali

This isn't so much Popperian falsificationism as just empiricist principles that were around, more or less, since Bacon's time. Falsificationism is something more technical and specific - one analytical treatment out of many that were being developed starting from around the turn of the century in an attempt to formalize and precisify those widely shared ideas. Poper, Duhem, Hempel, Ramsey, Fisher, Neyman, etc., etc. - they weren't in disagreement about the general principles (except when they were trying to exaggerate their differences, as Popper in particular was apt to do) - they disagreed about analysis.

But while such analytical work still continues, I think the era of all-encompassing analytical programmes for science has been eclipsed over the last half-century by a more historical-sociological approach of Kuhn, Feyerabend, etc. that acknowledges science's messy, complex human nature. None of the simple analytical models that have been proposed proved to be a good universal fit for science's successes and failures. Instead, there are general, necessarily vague empiricist principles, and then there are many particular methodologies, protocols, techniques and know-hows that are being gradually developed and adjusted as we go along. -

"White privilege"For myself, I am proud that I had loving parents, grandparents and grew up in a stable home with both a mom and dad present. — Teller

What exactly are you proud of? Choosing your parents wisely? -

Bias against philosophy in scientific circles/forumsUnfortunately, NY Times has a policy of endlessly nagging for readers to create a "free" account and give up lots of personally-identifying data, in order to access the information linked to. I have a personal policy that says, if the only source is NY Times, then it has no source, and then the information simply does not exist. My policy works absolutely fine. We do not "need" NY Times. How could we "need" them, if they are not even convenient to use? — alcontali

You don't need a NYT account to read this article. If somehow, despite your policy, you've exceeded their free articles-per-month limit, you can just open it in a private/incognito window or delete newyorktimes cookies.

Anyway, there is a link there to d'Espagnat's 1979 article in Scientific American, The Quantum Theory and Reality. Apparently he was pushing for a link between consciousness and quantum measurement - not a new idea even then, but one that was and still is largely rejected both by physicists and philosophers. Still, d'Espagnat is given credit for the resurgence of interest in philosophical problems of quantum theory.

Interesting link:

But, as many in Munich were surprised to learn, falsificationism is no longer the reigning philosophy of science. Nowadays, as several philosophers at the workshop said, Popperian falsificationism has been supplanted by Bayesian confirmation theory, or Bayesianism — alcontali

I don't think it's fair to say that Bayesianism supplanted Popperian falsificationism. Bayesian confirmation theory was developed by Ramsey, de Finetti and others long before Popper came on the scene, and remains with its variations, such as likelihoodism, one of the dominant quantitative treatments of theory selection. Falsificationism, on the other hand, never really took off and isn't much talked about, except in connection with Popper.

In my opinion, anything based on probability theory and statistics must be treated with utmost scrutiny, because these things are core ingredients in the snake-oil industry. — alcontali

Statistics is a very tricky and philosophically fraught subject. Nevertheless, statistics is where the rubber meets the road, as far as philosophy of science is concerned. If your philosophy has no implications for statistical methodology, then it has little relevance to science. -

The American Gun Control Debate32 mass shootings this so far this year - that's about once per week.

Looking forward to "debating" this for the next round of mass shootings! — Maw

“In retrospect Sandy Hook marked the end of the US gun control debate,” Dan Hodges, a British journalist, wrote in a post on Twitter two years ago, referring to the 2012 attack that killed 20 young students at an elementary school in Connecticut. “Once America decided killing children was bearable, it was over.” — NYT -

Bias against philosophy in scientific circles/forumsDo scientists have an irrational bias against philosophy, specifically philosophy of science? Or am I not understanding an obvious truth, such as that science doesn't seem to have anything to do with philsophy of science? — Shushi

Well, Science Forums has an explicitly stated narrow focus and tight moderation, so the fact that your thread was closed immediately and the earlier thread was short-lived as well is not an indication of anything. However, it has been my experience that people with scientific and engineering background do often display little patience for and a good deal of prejudice against philosophy. Unsurprisingly, this is mainly seen among those who know little about the field, or worse, have distorted ideas about it.

For example, outside of its specialized usage, the word "metaphysics" can mean "abstract theory with no basis in reality" (OED), and historically it has often been associated with the irrational and the occult. Is it surprising that people who are into natural sciences would tend to be allergic to such a notion? You yourself have confessed to thinking that "it was just pure speculative talk and nonsense that anyone could make up" - before you learned a little more about what philosophy was really about. And, to be fair, a good deal of philosophy has been and still is "speculative talk and nonsense" - but not all of it, as you and I agree (although to my mind, Penrose and Polkinghorne offer examples of the more disreputable kind of "metaphysics").

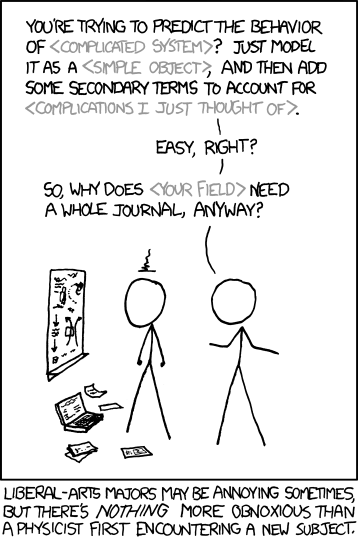

No doubt, some of the prejudice comes from ignorance and the sort of arrogance that people who are accomplished in their field often display for other fields (here, of course, I am talking about people like Hawking and Krauss, not just random Science Forum posters, most of whom are not even scientists). Physicists might be especially guilty of this:

There have always been scientists with an interest in and a respect for philosophy. Off the top of my head, a few of the prominent working scientists are George Ellis, Sean Carroll, Anthony Aguirre - perhaps not surprisingly, all cosmologists. I could also think of some theoretical physicists. But it used to be - I don't know if things have changed in the recent decades - that philosophy was almost a taboo subject in science departments. David Albert, who earned his Ph.D. in theoretical physics in 1981, says that after he developed an interest in philosophy he almost got kicked out of the grad school when he said that he wanted to write his thesis on foundations of physics. In the end he was forced to do a thesis on a very technical, calculation-heavy subject picked for him by the department, but eventually, after working with Aharonov at the Tel Aviv University, he became one of the more prominent philosophers of physics. -

The Universe Cannot Have Existed ‘Forever’WTF? Will you just keep spamming these idiotic threads about infinity? One is not enough for you?

-

Free Will or an illusion and how this makes us feel.Sorry I was a little snippy in my response. That free will is undermined by a deterministic universe is an old and perfectly respectable philosophical position.

How would I feel about the free will that doesn't exist? I think it would make me happy knowing that I am fully responsible for my actions and that others would be responsible for theirs instead of being victims of circumstance we would be accountable in a similar sense you would be able to blame and be blamed for things but also take complete credit. I suppose the feeling of control is what the best thing about it would be. — AwazawA

I think the best thing about a real free will would be that I could truly be the author of my own thoughts and feelings and actions which makes them feel more real than having it all go according to a fate. — AwazawA

But don't you still feel that, when you deliberately do something, it is you acting on your intentions? Don't you still feel in control and responsible for your actions? Don't you still hold others responsible for theirs?

It is true that, when we learn about all the external factors that influenced or even forced someone's decision, we are apt to feel that they were less in control, that the decision was not fully theirs, and that they are therefore less responsible for it. Likewise, when we contemplate the environment and incidents that formed someone's character, we may blame them less for some offense that they committed, or, in opposite circumstances, tend to take for granted their good deeds. But by and large, that sense of people, ourselves included, being the source of their actions and making choices when there are choices to be made remains strong, no matter what. -

Law Of Identity And Mathematics Of Changedon't want to reject mathematical models, far from being a mere philosophical point; if I thought that I would have to change job! Specifically, I think mathematical models really do allow us to find things out about nature. What I was trying to highlight was that the use of time in mathematical models doesn't really tell us much about it, as any smooth bijective function of time could be used to parametrise them. — fdrake

Well, there is this position, to which I am somewhat sympathetic, that the abstract (mathematical) entities that we find to be indispensable in explaining (modeling) the world thereby exist. Of course, as you point out, time may not even be all that indispensable, or even if some time was necessary, there is no one definite form of it that we are forced to adopt. But then the latter problem is basically what Einstein's relativity tackles, where time is quite substantive, even if it is very much a reference- and coordinate-dependent entity.

My love of the chain rule example is that it suggests one way to exploit the arbitrarity of the time variable to 'internalise' it to other concepts; of differentials of unfolding. While time and unfolding are probably interdependent, time is often seen as unitary whereas unfolding is a plurality of links which we know have affective power in nature. It invites an immanent thought of time, whereas the times thought in (A,B) and the hypostatised 'indifferent substrate' of time are both marred by their transcendental character. — fdrake

You don't even need a smooth function in order to convey this idea: really, what it comes down to is variable substitution: expressing one quantity in terms of another. This works even for ragged and discontinuous relationships. However, to return to my reservations about this thought as a justification for what is, I think, a physical and/or metaphysical thesis, the same abstract manipulation can be applied in ways that are less physically meaningful and certainly don't warrant a parallel conclusion. For example, in the famous predator-prey example, instead of looking at populations of wolves and hares, we could look at the population of wolves and the amount of manure excreted by hares, which of course is closely related to the population of hares. Does this mean that we can therefor dispense with hares in this system? Well, we could for the sake of modeling the population of wolves (or the amount of shit, if that is what we are interested in), but surely our ability to do so doesn't indicate that hares lack substance!

(By the way, for me the Lotka-Volterra problem was one of the more memorable experiences from learning mathematics. It becomes even more dynamically interesting in 3D, if you add another variable into the system, such as grass.)

Edit-imprecise summary: time is something empirically real, not just something transcendentally ideal. The empirically real component requires different methodology to attack than the usual Kantian/phenomenological interpretive machines, and is still of philosophical interest. — fdrake

Thanks for this, I know I haven't addressed much of what you've said - but that's because I would like to think more about it. -

Free Will or an illusion and how this makes us feel.You are not answering the question. You don't need to tell me about how you think free will does not exist because I've heard this a thousand times, and so has anyone who has spent any amount of time on a philosophy forum. I am wondering, along with your OP, how you feel about the hypothetical real free will, the one you think we don't have. What would it be like? How would it be different from the one that you call "pseudo free will" and Dennett calls "free will worth having?"

-

Free Will or an illusion and how this makes us feel.Gotcha. Yes, it's a good question. But I would like to turn it around: What would a real, non-illusory free will be like? In what way would it be different from the one that is supposedly illusory? What would it take to have such a capacity (if that's what it is, a capacity)?

-

Free Will or an illusion and how this makes us feel.Currently there hasn't been a great deal of discussion about free will — AwazawA

Have you tried the search function? -

Law Of Identity And Mathematics Of ChangeThere's a lot going on in the question. — fdrake

Yes, and thank you for a comprehensive response.

From this I think we should resist saying that the progression of the physical entity of a clock depends upon a concept we have derived from the clock; as if the clock would not tick without the operationalisation of time that it embodies in our understanding. Or if it would not tick without experiential temporality stretching along with it. — fdrake

Oh but I don't think that we derive the concept of time from the clock. From the moment of the first eye opening we already have some intuitive understanding of time. Observing clocks helps us to further contextualize, structure, and quantify that understanding, and more careful observation and reflection leads to more sophisticated understanding of the structure and measure of time in terms of mathematical models and measuring devices.

So when you ask yourself, "What is time?" you can point to periodic processes or to theoretical models, but then if you ask, "What validates those explanations?" you still have to go back to the phenomenology (including, of course, the phenomenology of clocks), because what else would we go back to? That doesn't mean, of course, that we have to hang on to every prejudice and intuition, but our explanations have to be true to something, or else they just hang free, like abstract mathematical entities.

What does a clock show? What does it mean to say that this iteration is prior to that? If we reject mathematical models as inadequate for exhaustively answering empirical questions, I am afraid that an answer can only be provided by gesturing, tautologically, towards some sort of unfolding. Tautologically because, of course, our notion of unfolding is already informed by the notion of periodic processes. -

The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy as a model for online informationThere is a difference between not dumbing a subject down, and explaining it in such a way that your explanation can only be understood by someone who has a sophisticated understanding of that subject already.

The following is a direct copy and paste from the article:

The following theses are all paradigmatically metaphysical:

“Being is; not-being is not” [Parmenides];

“Essence precedes existence” [Avicenna, paraphrased];

“Existence in reality is greater than existence in the understanding alone” [St Anselm, paraphrased];

“Existence is a perfection” [Descartes, paraphrased];

“Being is a logical, not a real predicate” [Kant, paraphrased];

“Being is the most barren and abstract of all categories” [Hegel, paraphrased];

“Affirmation of existence is in fact nothing but denial of the number zero” [Frege];

“Universals do not exist but rather subsist or have being” [Russell, paraphrased];

“To be is to be the value of a bound variable” [Quine]. — van Inwagen, Peter and Sullivan, Meghan

Hmm... Okay. Cool.

My personal favorites are the final three. Although "Existence is a perfection" has its charms too. — Theologian

Again, I am at a loss as to what occasioned your ridicule. Do you think that in order to understand the authors' point here, one needs to have studied all of the philosophers that they list, and understand the positions that each of those (selfconsciously crypitc) slogans designates? If you really think that, then I am sorry to say, you just don't know how to read.

What I actually said was:

an encyclopaedia article should be comprehensible to an intelligent lay person willing to put in a little effort. — Theologian — Theologian

You said that, but then you bristled at the suggestion that "an intelligent lay person" may have to put a little effort into looking something up in order to better understand what she is reading.

Note, I said "better." One thing you don't seem to understand about reading is that readers with different backgrounds can get different things out of the same text, and even the same reader can get different things from subsequent readings. You won't always comprehend everything there is to comprehend about a text, and that is OK, as long as you comprehend a fair amount. Someone who has never heard about Aquinas' Five Ways will still come away with an understanding that those arguments are a typical example of a certain kind of traditional metaphysics (as explained in the rest of the article), and if he doesn't care to look them up right away, perhaps he'll do so later with this knowledge in mind.

Try reading the article in its entirety and then get back to me. Of course, you do realize that I suggest this only because you have now earned sufficient enmity that I want to make you suffer... — Theologian

Yes, thank you, I am reading it now, and I am afraid I only have bad news for you. First, I like the article. Second, I find that it is fairly typical for SEP in rigor and style. -

Law Of Identity And Mathematics Of ChangeThe idea that a clock is simultaneously a measurement of and a definer of time is a bit weird (@Banno Luke @Fooloso4 @StreetlightX for Wittgenstein thread stuff :) ). I think it's better to think of periodic phenomena as operationalisations of a time concept which is larger than them; ways to index events to regularly repeating patterns. — fdrake

Yes, exactly, clocks (periodic processes) don't define time in the way definitions usually work, i.e. by completely reducing one concept to one or more other concepts; instead they operationalize time.

Thought experiment here - suppose that the universe is a process of unfolding itself, how can there be a time separate from the rates of its constitutive processes? What I'm trying to get at is that we should think of time as internal to the unfolding of related processes, rather than as an indifferent substrate unfolding occurs over. Think of time as equivalent to the plurality of linked rates, rather than a physical process operative over all of them. — fdrake

I agree with you here: it wouldn't do to think of time as just mathematical time of scientific models, or as an abstract metaphysical entity that exists independently of the world of physical processes. Just as there is no movement without there being moving things, there is no time without there being processes, unfoldings, etc.

And yet... how can there be processes, what could unfolding possibly mean, what are we to make of rates - without referring to the concept of time? I still insist that, although all these physical concepts in the first part of the sentence - let's refer to them as clocks for brevity - serve to operationalize time, they do not define time away; they are not more primary in our understanding than time itself is. And while we cannot understand time without referring to clocks, neither can we understand clocks without referring to time. -

The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy as a model for online informationI don't know that having at least heard of Aquinas' Five Ways constitutes "technical background knowledge," but fine, let's assume that some readers don't have any notion of them. So what? Perhaps you are thinking of an encyclopedia as the sort of popular encyclopedias that used to be sold door-to-door, or children's encyclopedias? Well, this is obviously not that kind of encyclopedia. I am not even sure that complete amateurs are its intended primary readership, but in any case, it is not light entertainment. This is an adult resource dealing with a fairly difficult intellectual subject. It doesn't spoon-feed you everything; if you don't know or don't understand something, it is your responsibility to do the extra work to keep up. And I am glad that the authors and the editors neither dumb down their writing nor bloat it with details intended to explain every little thing and cover every possible gap in the reader's knowledge - and yet they manage to present their subject in a way that even a layman like myself, without any education in the field, can follow most of it.

Learning something new is always difficult when you have to start from scratch - whether it is learning a foreign language, or a scientific theory, or challenging art. Philosophy is a mature professional field, so why do you have this expectation that learning it should be effortless for everyone, no matter their background? -

The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy as a model for online informationHonestly, I have no idea what you are talking about. Technical terms? What technical terms? Here is the sentence again:

"The first three of Aquinas's Five Ways are metaphysical arguments on any conception of metaphysics."

Well, I suppose if the words "Aquinas's Five Ways" say nothing to you, then you wouldn't quite know what the author is referring to, but you would still be able to infer from the context that some famous historical philosophical text is a paradigmatic example of metaphysical writing, even if contemporary metaphysicians concern themselves with different questions. And if you google those words, then in about ten seconds you can learn that "Aquinas's Five Ways" are "five logical arguments regarding the existence of God summarized by the 13th-century Catholic philosopher and theologian St. Thomas Aquinas in his book Summa Theologica." -

The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy as a model for online informationPerhaps we've been reading different articles, because my impression of the SEP is the exact opposite. I am a consummate layman: never took a philosophy class, and with the exception of Russell's little History of Western Philosophy, which I read many years ago and which served more to arouse interest and respect for the subject than anything else, I've never even read a complete philosophy book. As layman, I find SEP to be a great resource for getting acquainted with whatever philosophical subjects that catch my fancy. You get a brief explanation of the issue, an overview of developments, challenges, theories, open questions and controversies - and all this is supplied with a bibliography that you can follow at your leisure if you wish. You couldn't get this kind of information otherwise, without being a specialist yourself; I imagine that professional philosophers too find such resources useful for getting into topics that they know less about.

For the most part, I find the articles pretty accessible. Some topics proved to be a drag because the topic just didn't interest me much, but I don't think I've encountered entries that were objectively badly written or too technical for an interested layman to get at least something out of them.

Quite near the beginning of this atrociously dense and technical piece of writing, the author throws in the line: "The first three of Aquinas's Five Ways are metaphysical arguments on any conception of metaphysics." — Theologian

I don't understand why you find this sentence problematic. English is not my first language, so tell me, I am curious: is it the style? Or do you really not understand what it is saying? -

Donald Trump (All General Trump Conversations Here)I mean what was referred to in those days as the First World - North America, Western Europe, Japan, Australia. The liberal democratic order in those countries is what was widely considered to be the norm - not only by people who lived in those countries, but far beyond, by those who aspired towards the same lifestyle. Towards the end of the century especially, it came to be seen as the ultimate state of the human civilization (with some room for variations and improvements, to be sure), with no credible and stable alternative.

-

Donald Trump (All General Trump Conversations Here)I wonder what this will look like from the perspective of time and distance - an aberration that was limited and corrected or something that had more widespread and lost lasting consequences. — Fooloso4

I wonder whether a few decades from now, the post-war Western liberal democratic order will come to be seen as an aberration, or yet another passing phase at best, rather than "the end of history," as many saw it at the end of the last century. -

Law Of Identity And Mathematics Of ChangeSo, since it's arbitrary for the math, you can think of time relationally; as the pairing of systems creating an index; rather than as the index by which systems evolve. — fdrake

I think you have it a little backwards. We should think of time in relation to physical "clocks," such as heartbeats, diurnal cycles, pendulums or electromagnetic oscillations - because how else can we think of it? That this can be expressed in the form of the chain rule when modeling processes using differentiable functions is just a consequence. The backwards reasoning from a mathematical model to reality is inherently perilous, because mathematics can model all sorts of unphysical and counterfactual things.

Edit: or if you want it put (overstated) metaphysically, instead of conceiving as becoming as being changing over time, you can consider time as being's rates of becoming. — fdrake

Yes, except that when you ask what "rate" is, time creeps back in. I don't think you can completely eliminate time from consideration, reduce it to something else. You can put it in relation to something else, such as a clock (heartbeats, etc.), but that relationship is not reductive: it goes both ways. Clocks are just as dependent on time as time is on clocks. -

Arguments from AnalogyDid you read this in Wikipedia Argument from analogy perhaps?

P and Q are similar in respect to properties a, b, and c.

P has been observed to have further property x.

Therefore, Q probably has property x also.

Perhaps it may help to think of a property of P as any predicate applied to P:

P is red

P works in a bank

P happened yesterday

P is wrong

etc.

The latter "property" of being wrong or right, good or bad is particularly common in rhetorical uses of analogy. So for example when someone compares refugee detention centers to concentration camps, the analogy is clearly meant to imply that treating refugees in this way is wrong. -

Kastrup's The Idea of the World1. The existence of our perceptions and thoughts is more certain than the existence of matter, since the concept of matter is constructed from our perceptions and thoughts. (same goes with energy, invisible fields, superstrings, ...) — leo

What do you think? — leo

I think that this line of thought is psychologically naive. No, perceptions, thoughts, a certain order and hierarchy of our mental architecture - these are not apodictic, a priori truths. They are very much products of an abstract, theory-laden, culturally indebted thought. I don't think it even makes sense to talk about some absolutely a priori concepts. -

Can humanism be made compatible with evolution?They can base their values on whatever they like. — Coben

An ethical system is typically named after its core value. The core value of humanism is the human being. If they are basing this value on something else, then they shouldn't be called humanists - they should be something else-ists (rationalists perhaps, if they claim to have purely rational foundations for their values). -

Can humanism be made compatible with evolution?You are making it sound like cooperative behavior is motivated entirely by self-interest, which just isn't true. I don't even care to argue the point, I think it should be obvious if you think about it for a moment.

SophistiCat

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum