-

The Blind Spot of Science and the Neglect of Lived Experience

To turn the page for the moment, here's some Plotinus I like.

If, then, the perfect life is within human reach, the man attaining it attains happiness: if not, happiness must be made over to the gods, for the perfect life is for them alone.

...

It has been shown elsewhere that man when he commands not merely the life of sensation but also Reason and Authentic Intellection, has realised the perfect life.

...

To the man in this state, what is the Good?

He himself by what he has and is.

And the author and principle of what he is and holds is the Supreme, which within Itself is the Good but manifests Itself within the human being after this other mode.

The sign that this state has been achieved is that the man seeks nothing else.

...

Once the man is a Sage, the means of happiness, the way to good, are within, for nothing is good that lies outside him. Anything he desires further than this he seeks as a necessity, and not for himself but for a subordinate, for the body bound to him, to which since it has life he must minister the needs of life, not needs, however, to the true man of this degree. He knows himself to stand above all such things, and what he gives to the lower he so gives as to leave his true life undiminished.

Adverse fortune does not shake his felicity: the life so founded is stable ever. Suppose death strikes at his household or at his friends; he knows what death is, as the victims, if they are among the wise, know too. And if death taking from him his familiars and intimates does bring grief, it is not to him, not to the true man, but to that in him which stands apart from the Supreme, to that lower man in whose distress he takes no part.

...

If the Sage thinks all fortunate events, however momentous, to be no great matter—kingdom and the rule over cities and peoples, colonisations and the founding of states, even though all be his own handiwork—how can he take any great account of the vacillations of power or the ruin of his fatherland? Certainly if he thought any such event a great disaster, or any disaster at all, he must be of a very strange way of thinking. One that sets great store by wood and stones, or . . . Zeus . . . by mortality among mortals cannot yet be the Sage, whose estimate of death, we hold, must be that it is better than life in the body.

But suppose that he himself is offered a victim in sacrifice?

Can he think it an evil to die beside the altars?

But if he go unburied?

Wheresoever it lie, under earth or over earth, his body will always rot.

But if he has been hidden away, not with costly ceremony but in an unnamed grave, not counted worthy of a towering monument?

The littleness of it! — Plotinus

Kojeve also mentions satisfaction as proof of the wisdom that philosophy seeks.

What also stands out is the detachment from disaster. The sage looks evil, cold, or irresponsible to those who take the news seriously. Part of the appeal of science to me when I was a young adult was what I perceived as its quest for this kind of detachment. It was above and beyond the good and evil of the tribe. Even if the sage is gentle, his or her detachment would be offensive to most.

All social life is essentially practical. All mysteries which lead theory to mysticism find their rational solution in human practice and in the comprehension of this practice.

...

The philosophers have only interpreted the world, in various ways; the point is to change it. — Marx

Small surprise given this response to Feuerbach that Marx would hate Stirner's sage-like response to Feuerbach. And Feuerbach himself was something of a contemplative. I've read swaths of all three, and the tone of each is different.

Maybe the point of philosophy is to change the philosopher into something more like the sage.

I don't think you've tended to like ironic Western quasi-mystics, but to me the difference is largely one of style. In all cases there's a quest for the high place and its perspective.

For at the stage of romantic art the spirit knows that its truth does not consist in its immersion in corporeality; on the contrary, it only becomes sure of its truth by withdrawing from the external into its own intimacy with itself and positing external reality as an existence inadequate to itself. Even if, therefore this new content too comprises in itself the task of making itself beautiful, still beauty in the sense hitherto expounded remains for it something subordinate, and beauty becomes the spiritual beauty of the absolute inner life as inherently infinite spiritual subjectivity.

But therefore to attain its infinity the spirit must all the same lift itself out of purely formal and finite personality into the Absolute; i.e. the spiritual must bring itself into representation as the subject filled with what is purely substantial and, therein, as the willing and self-knowing subject. Conversely, the substantial and the true must not be apprehended as a mere ‘beyond’ of humanity, and the anthropomorphism of the Greek outlook must not be stripped away; but the human being, as actual subjectivity, must be made the principle, and thereby alone, as we already saw earlier [on pp. 435-6, 505-6], does the anthropomorphic reach its consummation.

The true content of romantic art is absolute inwardness, and its corresponding form is spiritual subjectivity with its grasp of its independence and freedom. This inherently infinite and absolutely universal content is the absolute negation of everything particular, the simple unity with itself which has dissipated all external relations, all processes of nature and their periodicity of birth, passing away, and rebirth, all the restrictedness in spiritual existence, and dissolved all particular gods into a pure and infinite self-identity. In this Pantheon all the gods are dethroned, the flame of subjectivity has destroyed them, and instead of plastic polytheism art knows now only one God, one spirit, one absolute independence which, as the absolute knowing and willing of itself, remains in free unity with itself and no longer falls apart into those particular characters and functions whose one and only cohesion was due to the compulsion of a dark necessity.[1]

...

God in his truth is therefore no bare ideal generated by imagination; on the contrary, he puts himself into the very heart of the finitude and external contingency of existence, and yet knows himself there as a divine subject who remains infinite in himself and makes this infinity explicit to himself. — Hegel -

The Blind Spot of Science and the Neglect of Lived Experience

I was thinking earlier that philosophy for me at least was largely phenomenology. Words can simply point out and summon our attention to what is already there.

[/quote]

Heidegger argues that we ordinarily encounter entities as (what he calls) equipment, that is, as being for certain sorts of tasks (cooking, writing, hair-care, and so on). Indeed we achieve our most primordial (closest) relationship with equipment not by looking at the entity in question, or by some detached intellectual or theoretical study of it, but rather by skillfully manipulating it in a hitch-free manner. Entities so encountered have their own distinctive kind of Being that Heidegger famously calls readiness-to-hand.

...

Tools-in-use become phenomenologically transparent. Moreover, Heidegger claims, not only are the hammer, nails, and work-bench in this way not part of the engaged carpenter's phenomenal world, neither, in a sense, is the carpenter. The carpenter becomes absorbed in his activity in such a way that he has no awareness of himself as a subject over and against a world of objects. — SEP

So the famous hammer has at least two modes of being, one as tool-in-use and the other as object for theory. And this is a beetle in the box. We can't weigh the hammer to check to for its 'handiness,' but we might realize afterward that we were dissolved with it and the scale in its weighing.

Because phenomenology does seem to aim at the beetle in the box (subjectivity), it give philosophy something to do that science isn't obviously equipped to do. Phenomenology does seem to aim at objective or unbiased truth, without, however, being subject to falsification.

Along those lines, here is something that also ties in with the OP.

Suppose everyone had a box with something in it: we call it a "beetle". No one can look into anyone else's box, and everyone says he knows what a beetle is only by looking at his beetle.-Here it would be quite possible for everyone to have something different in his box. One might even imagine such a thing constantly changing.---But suppose the word "beetle" had a use in these people's language?---If so it would not be used as the name of a thing. The thing in the box has no place in the language-game at all; not even as a something: for the box might even be empty.--No, one can `divide through' by the thing in the box; it cancels out, whatever it is.

That is to say: if we construe the grammar of the expression of sensation on the model of `object and name' the object drops out of consideration as irrelevant.

The essential thing about private experience is really not that each person possesses his own exemplar but that nobody knows whether other people also have this or something else. The assumption would thus be possible---though unverifiable---that one section of mankind had one sensation of red and another section another. — Wittgenstein

For 'the sensation of red' we can substitute 'genuine spiritual experience' or 'what it is like to grasp a concept' or 'the kind of being a quark has' or 'happiness' and so on.

What does all of this mean or imply? I liked behaviorism when I first read about it as a clever way to circumvent the problem of elusive private consciousness. One interesting game with its own kind of purity is finding quantitative and causal relationships among public entities across time and space. Another is contemplating human existence as a whole with all of its troublesome beetles. -

The Blind Spot of Science and the Neglect of Lived ExperienceReason is but one aspect of human life; it is by no means the sole medium we "swim in". It is good that reason should be "demoted" in my view; who (apart from Hegel) would want it to be the absolute? — Janus

I never said I swim only in reason, and are you really setting me up as knee-deep in scientism? I'm just saying that I can't catch my own tail. If I reason that my reason is undermined, then I can't trust that my reason is undermined after all. On Certainty is great on this issue. I am in a 'system' that I can always only doubt piecemeal.

Also reason runs out of reasons. For me existence is a brute fact. We've discussed thequestion.'Why is there a there here?' We don't want the kind of answer that we know how to give. We seem to be expressing wonder, perceiving the contingency of the rose without reason.

Science is a lovely instrument, but I also cherish my ironic mysticism of whatever anyone wants to call it. If the words matter, it's not the real thing, seems to me. And I'm @g0d, so that should count for something.

The “kingdom of heaven” is a state of the heart—not something to come “beyond the world” or “after death.”

...

This faith does not formulate itself—it simply lives, and so guards itself against formulae...It is only on the theory that no word is to be taken literally that this anti-realist is able to speak at all. Set down among Hindus he would have made use of the concepts of Sankhya,[7] and among Chinese he would have employed those of Lao-tse[8]—and in neither case would it have made any difference to him.—With a little freedom in the use of words, one might actually call Jesus a “free spirit”[9]—he cares nothing for what is established: the word killeth,[10] whatever is established killeth. The idea of “life” as an experience, as he alone conceives it, stands opposed to his mind to every sort of word, formula, law, belief and dogma. He speaks only of inner things: “life” or “truth” or “light” is his word for the innermost—in his sight everything else, the whole of reality, all nature, even language, has significance only as sign, as allegory. — Nietzsche on Christ

I was watching old Vonnegut videos lately, and I was thinking of the fundamental roles we adopt. I like the jokers. Seriousness is the toll we pay to keep waking up in the morning. For me it's really about something like laughing with the gods. [And of course the usual nice things in life, but I was thinking of intellectual pleasures.] -

The Blind Spot of Science and the Neglect of Lived ExperienceThat said, I think that if some metaphysical theories were to be "true" (whatever you might take that "truth" to mean) then it would more likely be those which are in accordance with scientific understanding than those which are not. In assessing such likelihood and hence plausibility of metaphysical theories i don't see that we have much else to go on. — Janus

I agree. It seems to be our nature to try and integrate our beliefs, scientific and otherwise. More generally, I like this attitude:

When I speak of reason or rationalism, all I mean is the conviction that we can learn through criticism of our mistakes and errors, especially through criticism by others, and eventually also through self-criticism. A rationalist is simply someone for whom it is more important to learn than to be proved right; someone who is willing to learn from others — not by simply taking over another's opinions, but by gladly allowing others to criticize his ideas and by gladly criticizing the ideas of others. The emphasis here is on the idea of criticism or, to be more precise, critical discussion. The genuine rationalist does not think that he or anyone else is in possession of the truth; nor does he think that mere criticism as such helps us achieve new ideas. But he does think that, in the sphere of ideas, only critical discussion can help us sort the wheat from the chaff. He is well aware that acceptance or rejection of an idea is never a purely rational matter; but he thinks that only critical discussion can give us the maturity to see an idea from more and more sides and to make a correct judgement of it. — Popper -

The Blind Spot of Science and the Neglect of Lived Experienceto say that reason is an evolved, rtaher than some kind of "absolute", faculty would not be to undermine it. — Janus

Well I can't help but use reason. I swim in it. So I wouldn't use 'undermined.' But I do think that reason is thereby demoted in some sense, and not for the first time. Does it change my feeling about science? No. -

The Blind Spot of Science and the Neglect of Lived ExperienceAnd it does seem plausible to think that theories which entail predictions that are confirmed by observation and experiment are more likely to be true to the nature of things than those which do not. — Janus

Of course this is reasonable. I think that's largely what beliefs are for. We only care about whether they are 'true' or not in terms of consequences. 'Your fuel pump's shot' helps us get the car going. Isn't this a classic issue? I do like instrumentalism for just dodging metaphysics.

A successful scientific theory reveals nothing known either true or false about nature's unobservable objects, properties or processes.[4] Scientific theories are assessed on their usefulness in generating predictions and in confirming those predictions in data and observations, and not on their ability to explain the truth value of some unobservable phenomenon. The question of "truth" is not taken into account one way or the other. According to instrumentalists, scientific theory is merely a tool whereby humans predict observations in a particular domain of nature by formulating laws, which state or summarize regularities, while theories themselves do not reveal supposedly hidden aspects of nature that somehow explain these laws.[5] Initially a novel perspective introduced by Pierre Duhem in 1906, instrumentalism is largely the prevailing theory that underpins the practice of physicists today.[5]

Rejecting scientific realism's ambitions to uncover metaphysical truth about nature,[5] instrumentalism is usually categorized as an antirealism, although its mere lack of commitment to scientific theory's realism can be termed nonrealism. Instrumentalism merely bypasses debate concerning whether, for example, a particle spoken about in particle physics is a discrete entity enjoying individual existence, or is an excitation mode of a region of a field, or is something else altogether.[6][7][8] Instrumentalism holds that theoretical terms need only be useful to predict the phenomena, the observed outcomes.[6] — Wiki -

The Blind Spot of Science and the Neglect of Lived ExperienceMy contention was more modest: that the general efficacy of reason to draw valid conclusions has been augmented by natural selection. — Janus

Of course that's plausible. I don't see how we could test, however. Let's say we could pluck out a sequence of ancestors with a time machine. We'd have to use the reason we've evolved to evaluate whether progress was made.

I think what we call our reason is an abyssal or groundless ground. I suppose that both individuals and communities (through individuals) employ faculties that they can't justify and mostly don't notice (personal and cultural liquid lenses.) -

The Blind Spot of Science and the Neglect of Lived ExperienceThis seems to me a misrepresentation of Dennett's faith in rationality. I take it that Dennett thinks rationality is effective in getting to the truth precisely because it has evolved as a tool which has been honed and refined by natural selection. — Janus

That's a good point, but Nietzsche comes to mind. Is what helps us survive therefore the truth? I'm not against pragmatism's 'truth,' but I think it's fair to point out a tension in this or that position. Why should we have evolved to perceive what we think we mean by 'truth'?

Or do we just call useful beliefs 'true'? (Then I remember my OLP and that we use 'true' in a million ways that don't add up to some clean, single concept.) -

The Blind Spot of Science and the Neglect of Lived ExperienceBut the synthetic a priori enables us to acquire a kind of deductive certainty with respect to phenomena that you might think were only inductively true. — Wayfarer

I agree that it allows us to think deductively about nature. We can still be wrong. We can postulate some necessity (the quantity of matter is constant), deduced expected measurements, and check them against actual measurements.

I am not doubting the fact that it's valid, but I'm questioning the sense in which it exists. In what sense does such a theorem exist? You can't perceive any such thing through the unaided senses, its existence is purely intellectual, but it's real, just as Einstein says. — Wayfarer

What does it mean for something to be? Do different entities have different modes of being? I say yes, different modes of being. The 'what-it-is' of grasping a theorem just... is what it is? In the same way redness is redness? There is no gap, no representation more or less correct, but just it, right there. We do have the beetle in the box problem. I can't know that others experience what we call 'red' as I do, and I can't know what it is like for them to grasp the theorem. I think we tend to naturally trust that my red is your red, my toothache is your toothache, my spatial intuition is yours, etc. In my wife's face I think I see my own feeling reflected.

So the Pythagorean theorem is not 'out there somewhere', it doesn't exist in a phenomenal sense at all. Rather it is close, I think, to what ancient philosophy designated an 'intelligible object' - something the existence of which is mind-dependent, but it is not dependent on a particular mind; it is a noetic device, if you like, through which we then view and explain phenomena. — Wayfarer

I agree with mind-dependent and individual-independent. I can't prove this, because it's a beetle in a box. But I think 'world 3' exists for others as it does for me.

And another text:Before we as individuals are even conscious of our existence we have been profoundly influenced for a considerable time (since before birth) by our relationship to other individuals who have complicated histories, and are members of a society which has an infinitely more complicated and longer history than they do (and are members of it at a particular time and place in that history); and by the time we are able to make conscious choices we are already making use of categories in a language which has reached a particular degree of development through the lives of countless generations of human beings before us. . . . We are social creatures to the inmost centre of our being. The notion that one can begin anything at all from scratch, free from the past, or unindebted to others, could not conceivably be more wrong. — Popper

To sum up, we arrive at the following picture of the universe. There is the physical universe, world 1, with its most important sub-universe, that of the living organisms. World 2, the world of conscious experience, emerges as an evolutionary product from the world of organisms. World 3, the world of the products of the human mind, emerges as an evolutionary product from world 2.”

“The feedback effect between world 3 and world 2 is of particular importance. Our minds are the creators of world 3; but world 3 in its turn not only informs our minds, but largely creates them. The very idea of a self depends on world 3 theories, especially upon a theory of time which underlies the identity of the self, the self of yesterday, of today, and of tomorrow. The learning of a language, which is a world 3 object, is itself partly a creative act and partly a feedback effect; and the full consciousness of self is anchored in our human language.” — Popper

These ideas are in other thinkers too.

Feuerbach made his first attempt to challenge prevailing ways of thinking about individuality in his inaugural dissertation, where he presented himself as a defender of speculative philosophy against those critics who claim that human reason is restricted to certain limits beyond which all inquiry is futile, and who accuse speculative philosophers of having transgressed these. This criticism, he argued, presupposes a conception of reason that is a cognitive faculty of the individual thinking subject that is employed as an instrument for apprehending truths. He aimed to show that this view of the nature of reason is mistaken, that reason is one and the same in all thinking subjects, that it is universal and infinite, and that thinking (Denken) is not an activity performed by the individual, but rather by “the species” acting through the individual. “In thinking”, Feuerbach wrote, “I am bound together with, or rather, I am one with—indeed, I myself am—all human beings” (GW I:18). — SEP

In short, the we precedes the I in a vital sense. Yet this 'we' and its 'world 3' depend on the lives of individuals. Our individual bodies are candles that share in one flame. I know this makes the haters cringe, but it's as mundane understanding English and talking about philosophy together. The individual ego is not abolished, but its power to disagree and stand apart is not its own. It learns the words it uses to construct its secret name from others. -

The Blind Spot of Science and the Neglect of Lived Experience

This is a great issue. We might as well bring out the text:

http://www.gutenberg.org/files/4280/4280-h/4280-h.htm#chap08It is, therefore, a question which requires close investigation, and not to be answered at first sight, whether there exists a knowledge altogether independent of experience, and even of all sensuous impressions? Knowledge of this kind is called a priori, in contradistinction to empirical knowledge, which has its sources a posteriori, that is, in experience.

But the expression, “a priori,” is not as yet definite enough adequately to indicate the whole meaning of the question above started. For, in speaking of knowledge which has its sources in experience, we are wont to say, that this or that may be known a priori, because we do not derive this knowledge immediately from experience, but from a general rule, which, however, we have itself borrowed from experience. Thus, if a man undermined his house, we say, “he might know a priori that it would have fallen;” that is, he needed not to have waited for the experience that it did actually fall. But still, a priori, he could not know even this much. For, that bodies are heavy, and, consequently, that they fall when their supports are taken away, must have been known to him previously, by means of experience.

By the term “knowledge a priori,” therefore, we shall in the sequel understand, not such as is independent of this or that kind of experience, but such as is absolutely so of all experience.

...

In all judgements wherein the relation of a subject to the predicate is cogitated (I mention affirmative judgements only here; the application to negative will be very easy), this relation is possible in two different ways. Either the predicate B belongs to the subject A, as somewhat which is contained (though covertly) in the conception A; or the predicate B lies completely out of the conception A, although it stands in connection with it. In the first instance, I term the judgement analytical, in the second, synthetical.

...

The science of natural philosophy (physics) contains in itself synthetical judgements a priori, as principles. I shall adduce two propositions. For instance, the proposition, “In all changes of the material world, the quantity of matter remains unchanged”; or, that, “In all communication of motion, action and reaction must always be equal.” In both of these, not only is the necessity, and therefore their origin a priori clear, but also that they are synthetical propositions. For in the conception of matter, I do not cogitate its permanency, but merely its presence in space, which it fills. I therefore really go out of and beyond the conception of matter, in order to think on to it something a priori, which I did not think in it. The proposition is therefore not analytical, but synthetical, and nevertheless conceived a priori; and so it is with regard to the other propositions of the pure part of natural philosophy. — Kant

Kant made a strong case (against received wisdom) that math was indeed synthetic a priori

knowledge. I agree. The a priori and a posteriori distinction isn't perfect though, as others have suggested.

But what does it mean to say that 'in all changes of the material world, the quantity of matter remains unchanged'? I think what's important here is simply our ability to frame the world as incapable of changing its quantity of matter. The quantity of matter 'must' be constant. 'I know that 2000 years from now that we'll have the same amount of matter.'

Our experience is rich with this kind of structure, and perhaps Hume did not do it justice. Perhaps Hume also understood the subject as passive in this regard, when in fact we spontaneously generate theories (sometimes to our detriment.) What Hume didn't emphasize was perhaps the 'conceptual experience' of law. He was aware of such laws but maybe not as explicitly aware as was Kant. I'd have to read more to know for sure.

Still, as Nietzsche liked to joked, Kant's answer was basically 'by means of a faculty.' I guess it's no small thing to bring such a faculty into the direct light of reason as an explicit object of investigation. -

Subject and object

What do you make of quarks, atoms, waves? These are mental in some sense (concepts) and yet applied to objects in the world. If the redness of the apple is mental, then why not also our understanding of it in terms of atoms? The non-mental is like a vanishing point. Yet I agree that we always aim our talk at something we might call 'non-mental.' The quest for objectivity suggests that communication presupposes a world or reality that is talked about more or less correctly. -

Subject and object

Me too.

I do like the 'non-mental' as the other to the mental. I like the lens metaphor. The mental is aimed at and reveals the non-mental. Or at least the lens metaphor gets something right. -

Subject and objectAre you saying that you do not see how getting human thought/belief right is so important? — creativesoul

No. Having good beliefs is absolutely central, hence philosophy and science.

I guess I think having beliefs about beliefs is uncontroversial. We talk about beliefs about things as well as beliefs about beliefs. -

Subject and objectI'm a physicalist, so I wouldn't say mental and physical, but mental and non-mental, or alternately, a subset of brain function (which is what "mental" is, physically) and everything else. — Terrapin Station

Fair enough. So you acknowledge the experience of redness? A what-it-is-like to be a human being? -

Subject and objectOne would think so... none wrote about it. — creativesoul

Perhaps because it didn't seem important to them?

I confess: I'm still not seeing why the distinction is so important. -

Subject and objectNot drawing and maintaining the actual distinction between thought/belief and thinking about thought/belief, and as a result mistakenly thinking/believing - as a result of the consequences following from an inadequate notion of thought/belief - that only humans are capable of thinking/believing. — creativesoul

It seems to me that they use the distinction constantly. Isn't philosophy largely beliefs about beliefs? I don't claim that any philosopher is adequate in the sense of cannot-be-improved.

So are you thinking of animals, aliens? And are you saying that philosophers have tended to under-rate the intelligence of animals? Personally I think that some animals do indeed think (have concepts and beliefs). I suppose the difficult issue is how much language we demand before we use the word 'belief.'

But then humans have strong visual imaginations, and we can expect a basketball to rebound a certain way for instance without having words for it.

A landowner had been quite bothered by the crow since it had chosen to nest in his watch-house. He had planned to shoot it. The bird would fly away and wait until the landowner had left to return to its nest inside the watch-house, given that no-one would be inside to shoot it. In order to deceive it, the landowner had two people enter the watch-house and one leave. The crow was not deceived by this malicious plan, even when three men entered and two left. It wasn’t until five men had entered the tower and four had left that the bird did eventually fly back inside the watch-house. — link

https://blogofthecosmos.com/2016/03/01/the-numerical-abilities-of-non-human-animals/

More impressive:

er instructor and caregiver, Francine Patterson, reported that Koko had an active vocabulary of more than 1,000 signs of what Patterson calls "Gorilla Sign Language" (GSL).[4][5] In contrast to other experiments attempting to teach sign language to non-human primates, Patterson simultaneously exposed Koko to spoken English from an early age. It was reported that Koko understood approximately 2,000 words of spoken English, in addition to the signs.[6] Koko's life and learning process has been described by Patterson and various collaborators in books, peer-reviewed scientific articles, and on a website.[7]

As with other great-ape language experiments, the extent to which Koko mastered and demonstrated language through the use of these signs is disputed.[8][9] It is generally accepted that she did not use syntax or grammar, and that her use of language did not exceed that of a young human child.[10][11][12][13][14] However, she scored between 70 and 90 on various IQ scales, and some experts, including Mary Lee Jensvold, claim that "Koko...[used] language the same way people do".[15][16][17] — Wiki

Even if Koko was only like a 2-year old (which I'm not sure about), that's impressive. -

Subject and objectTaking account of human thought/belief must take proper account of how one acquires a worldview, and it must do so using a framework that is amenable to evolution.

12 minutes ago — creativesoul

I think I agree with that. That's where anti-realism continues with Hegel, Heidegger, Wittgenstein, etc. The 'lens' (framework) is liquid and historical. The liquidity is realized as we get over the notion that words have fixed-enough context-independent meanings to build systems with. Our living liquid system has to already be working just fine before we even dream of fixing what isn't broken.

What I mean by 'math with essences' is treating concepts as sharp and distinct and then joining them together like legos and calling it a day. The situation is far more organic, and our skill surpasses the account we can give of it. Along with this our actions are hopelessly entangled with meaning-in-the-head. Wittgenstein's beetle in the box helps point this out. I'm sure your're aware of the idea, but this video is cute if you haven't seen it:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=x86hLtOkou8 -

The Blind Spot of Science and the Neglect of Lived ExperienceNotice the emphasis on the 'synthetic a priori' - this is the idea that, unlike purely a priori truths which are tautological, in some sense, the synthetic a priori 'synthesis' rational arguments to arrive at a novel conclusion, i.e. one which is not implicit in the premisses. — Wayfarer

Indeed, and the passage on geometry in Hume suggests that Hume was aware of what Kant called synthetic a priori truths. http://www.humesociety.org/hs/issues/v13n2/steiner/steiner-v13n2.pdf To be sure he didn't focus on them or call them that.

To be sure Kant made explicit something important. We aren't born knowing the Pythogorean theorem but only with a shared spatial intuition that makes the perception of its truth possible for all of us, more or less independently of our cultural-linguistic software.

-

The Blind Spot of Science and the Neglect of Lived ExperienceSo I think one way of putting that is that Hume is arguing that we can't actually perceive a necessary relationship between cause and effect, but that Kant counters that, without the 'categories of the understanding', which intuitively perceive such relations, then experience itself wouldn't be cohesive - we literally couldn't think, let alone argue. — Wayfarer

I agree very much that we need the categories of the understanding. This is being 'in' a language. And I have read about both of their conceptions of causality. I lean toward saying that yes there is a kind of faculty that projects necessity. But what do we mean by this? How is this so different from expectation?

There is no consensus, of course, over whether Kant’s response succeeds, but there is no more consensus about what this response is supposed to be. There has been sharp disagreement concerning Kant’s conception of causality, as well as Hume’s, and, accordingly, there has also been controversy over whether the two conceptions really significantly differ. There has even been disagreement concerning whether Hume’s conception of causality and induction is skeptical at all. — SEP

I agree that Kant went in to far more detail about our conceptual structuring of reality, but I think the popular rendition cuts to many corners.

3. Nothing, at first view, may seem more unbounded than the thought of man, which not only escapes all human power and authority, but is not even restrained within the limits of nature and reality. To form monsters, and join incongruous shapes and appearances, costs the imagination no more trouble than to conceive the most natural and familiar objects. And while the body is confined to one planet, along which it creeps with pain and difficulty; the thought can in an instant transport us into the most distant regions of the universe; or even beyond the universe, into the unbounded chaos, where nature is supposed to lie in total confusion. What never was seen, or heard of, may yet be conceived; nor is any thing beyond the power of thought, except what implies an absolute contradiction.

But though our thought seems to possess this unbounded liberty, we shall find, upon a nearer examination, that it is really confined within very narrow limits, and that all this creative power of the mind amounts to no more than the faculty of compounding, transposing, augmenting, or diminishing the materials afforded us by the senses and experience. When we think of a golden mountain, we only join two consistent ideas, gold, and mountain, with which we were formerly acquainted. A virtuous horse we can conceive; because, from our own feeling, we can conceive virtue; and this we may unite to the figure and shape of a horse, which is an animal familiar to us. In short, all the materials of thinking are derived either from our outward or inward sentiment: the mixture and composition of these belongs alone to the mind and will. Or, to express myself in philosophical language, all our ideas or more feeble perceptions are copies of our impressions or more lively ones. — Hume

As you can see, Hume believed in ideas like 'gold' and 'mountain.' He doesn't mention that perceiving a mountain as a mountain involves structuring, but that's not his focus.

He clearly thinks the mind has a structure --is a system of faculties:

It cannot be doubted, that the mind is endowed with several powers and faculties, that these powers are distinct from each other, that what is really distinct to the immediate perception may be distinguished by reflexion; and consequently, that there is a truth and falsehood in all propositions on this subject, and a truth and falsehood, which lie not beyond the compass of human understanding. There are many obvious distinctions of this kind, such as those between the will and understanding, the imagination and passions, which fall within the comprehension of every human creature; and the finer and more philosophical distinctions are no less real and certain, though more difficult to be comprehended. — Hume -

Subject and objectFair question. He waffles. A priori and a posteriori. — creativesoul

That's a good distinction, if not perfect. I suggest that we pretty much have only good-not-perfect distinctions. -

The Blind Spot of Science and the Neglect of Lived ExperienceWhat was it that Hume wrote, that Kant said ‘awakened him from his dogmatic slumber’? — Wayfarer

This is fascinating page: https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/kant-hume-causality/

Whereas the concept of causality is, for Kant, clearly a priori, he does not think that particular causal laws relating specific causes with specific effects are all synthetic a priori—and, if they are not a priori, how can they be necessary? Indeed, Kant illustrates this difficulty, in a footnote to § 22, with his own example of the sun warming a stone (4, 305; 58):

But how does this proposition, that judgments of experience are supposed to contain necessity in the synthesis of perceptions, agree with my proposition, urged many times above, that experience, as a posteriori cognition, can yield only contingent judgments? If I say that experience teaches me something, I always mean only the perception that lies within in it, e.g., that heat always follows the illumination of the stone by the sun. That this heating results necessarily from the illumination by the sun is in fact contained in the judgment of experience (in virtue of the concept of cause); but I do not learn this from experience, rather, conversely, experience is first generated through this addition of the concept of the understanding (of cause) to the perception.

In other words, experience in the Humean sense teaches me that heat always (i.e., constantly) follows the illumination of the stone by the sun; experience in the Kantian sense then adds that:

the succession is necessary; … the effect does not merely follow upon the cause but is posited through it and follows from it. (A91/B124)

But what exactly does this mean? — link

Yes, what exactly does it mean? -

The Blind Spot of Science and the Neglect of Lived ExperienceWhich is precisely what the empiricists claim. They’re not equivocal about it. — Wayfarer

You have the context, though:

And of course:For, on the contrary, it is quite possible that our empirical knowledge is a compound of that which we receive through impressions, and that which the faculty of cognition supplies from itself (sensuous impressions giving merely the occasion), an addition which we cannot distinguish from the original element given by sense, till long practice has made us attentive to, and skillful in separating it. — Kant

How are these conceptually structured intuitions so different from Hume's impressions?Thoughts without content are empty, intuitions without concepts are blind. It is, therefore, just as necessary to make our concepts sensible, that is, to add the object to them in intuition, as to make our intuitions intelligible, that is, to bring them under concepts. — Kant

Compare that with:

The senses at first let in particular ideas, and furnish the yet empty cabinet; and the mind by degrees growing familiar with some of them, they are lodged in the memory, and names got to them. Afterwards the mind, proceeding farther, abstracts them, and by degrees learns the use of general names. In this manner the mind comes to be furnished with ideas and language, the [21] materials about which to exercise its discursive faculty: and the use of reason becomes daily more visible, as these materials, that give it employment, increase.

...

The understanding, like the eye, whilst it makes us see and perceive all other things, takes no notice of itself; and it requires art and pains to set it at a distance, and make it its own object. — John Locke

And consider this:

Hume doesn't go into much detail, but that last sentence is hard to ignore.All the objects of human reason or enquiry may naturally be divided into two kinds, to wit, Relations of Ideas, and Matters of Fact. Of the first kind are the sciences of Geometry, Algebra, and Arithmetic; and in short, every affirmation which is either intuitively or demonstratively certain. That the square of the hypotenuse is equal to the square of the two sides, is a proposition which expresses a relation between these figures. That three times five is equal to the half of thirty, expresses a relation between these numbers. Propositions of this kind are discoverable by the mere operation of thought, without dependence on what is anywhere existent in the universe. Though there never were a circle or triangle in nature, the truths demonstrated by Euclid would for ever retain their certainty and evidence.

— Hume

We can go back further.

By this it appears that Reason is not as Sense, and Memory, borne with us; nor gotten by Experience onely; as Prudence is; but attayned by Industry; first in apt imposing of Names; and secondly by getting a good and orderly Method in proceeding from the Elements, which are Names, to Assertions made by Connexion of one of them to another; and so to syllogismes, which are the Connexions of one Assertion to another, till we come to a knowledge of all the Consequences of names appertaining to the subject in hand; and that is it, men call SCIENCE. And whereas Sense and Memory are but knowledge of Fact, which is a thing past, and irrevocable; Science is the knowledge of Consequences, and dependance of one fact upon another: by which, out of that we can presently do, we know how to do something els when we will, or the like, another time; Because when we see how any thing comes about, upon what causes, and by what manner; when the like causes come into our power, wee see how to make it produce the like effects.

...

No Discourse whatsoever, can End in absolute knowledge of Fact, past, or to come. For, as for the knowledge of Fact, it is originally, Sense; and ever after, Memory. And for the knowledge of consequence, which I have said before is called Science, it is not Absolute, but Conditionall. No man can know by Discourse, that this, or that, is, has been, or will be; which is to know absolutely: but onely, that if This be, That is; if This has been, That has been; if This shall be, That shall be: which is to know conditionally; and that not the consequence of one thing to another; but of one name of a thing, to another name of the same thing. — Hobbes

There is a difference in attitude between the empiricists (excluding the Bishop, whom I didn't quote) and Kant.

I must, therefore, abolish knowledge, to make room for belief. — Kant -

Subject and objectAs I said... too much baggage. — creativesoul

And I say not justification/explanation for 'too much baggage,' especially since common-sense realism is almost the minimal, pre-philosophical position. -

Subject and objectThere is no thinking possible without experience. There is no reason without thinking. All experience is chock full of thought/belief. Reason is thinking about thought/belief. Reason requires pre-existing thought/belief in the same way that an apple pie requires apples. Where there is no apple/thought, there can be no apple pie/reason. — creativesoul

Of course, but why do you think Kant doesn't know that?

Here's how the CPR opens.

That all our knowledge begins with experience there can be no doubt. For how is it possible that the faculty of cognition should be awakened into exercise otherwise than by means of objects which affect our senses, and partly of themselves produce representations, partly rouse our powers of understanding into activity, to compare to connect, or to separate these, and so to convert the raw material of our sensuous impressions into a knowledge of objects, which is called experience? In respect of time, therefore, no knowledge of ours is antecedent to experience, but begins with it. — Kant

And reason deals with beliefs:

The first half of the Critique of Pure Reason argues that we can only obtain substantive knowledge of the world via sensibility and understanding. Very roughly, our capacities of sense experience and concept formation cooperate so that we can form empirical judgments.

...

In the famous “Refutation of Idealism,” Kant says the following: “Whether this or that putative experience is not mere imagination [or dream or delusion, etc.] must be ascertained according to its particular determinations and through its coherence with the criteria of all actual experience” (B279). To see what Kant means, consider a simple example. Suppose that our dreamer believes she has won a lottery, but then starts to examine this belief. To decide its truth, she must ask how far it connects up with her other judgments, and those of other people.[4] If it fails to connect up (she checks the winning numbers, say, and sees no match with her actual ticket), she must conclude that the belief was false. Otherwise, she would contradict a fundamental law of possible experience, that it be capable of being unified. As Kant summarizes his position: “ the law of reason to seek unity is necessary, since without it we would have no reason, and without that, no coherent use of the understanding, and, lacking that, no sufficient mark of empirical truth…” (A651/B679).[5]

In sum, what separates material error from true cognition for Kant is that true cognitions must find a definite place within a single, unified experience of the world. Since reason is an important source of the unifying structure of experience, it proves essential as an arbiter of empirical truth. — SEP

My interest here is an adequate account of that complexity. — creativesoul

Sure, me too. Or an adequate account of why such an account should no longer be hoped for or pursued.

I'm sure that there are plenty of insightful authors who draw compelling comparisons between the two... — creativesoul

Of course, but of course I didn't pick the one I mentioned randomly.

I see that they both make the same mistake of Hume and Kant. I like all of these greats and more. They've paved the way. — creativesoul

By all means let's have the mistake they all made. -

The Blind Spot of Science and the Neglect of Lived ExperienceThis is the sense in which Kant criticizes the empiricists. The gist of it is, to even make the arguments that they make, the empiricists are already assuming the very faculties which they believe they can account for in terms of experience. — Wayfarer

I like to see more textual evidence that empiricists

Kant is great, and he added to the empiricists. But what is the spirit of his work? The preface of the first edition is a natural place to look.

It is plainly not the effect of the levity, but of the matured judgement* of the age, which refuses to be any longer entertained with illusory knowledge, It is, in fact, a call to reason, again to undertake the most laborious of all tasks—that of self-examination, and to establish a tribunal, which may secure it in its well-grounded claims, while it pronounces against all baseless assumptions and pretensions, not in an arbitrary manner, but according to its own eternal and unchangeable laws. This tribunal is nothing less than the critical investigation of pure reason.

I do not mean by this a criticism of books and systems, but a critical inquiry into the faculty of reason, with reference to the cognitions to which it strives to attain without the aid of experience; in other words, the solution of the question regarding the possibility or impossibility of metaphysics, and the determination of the origin, as well as of the extent and limits of this science. All this must be done on the basis of principles.

This path—the only one now remaining—has been entered upon by me; and I flatter myself that I have, in this way, discovered the cause of—and consequently the mode of removing—all the errors which have hitherto set reason at variance with itself, in the sphere of non-empirical thought... It is true, these questions have not been solved as dogmatism, in its vain fancies and desires, had expected; for it can only be satisfied by the exercise of magical arts, and of these I have no knowledge. But neither do these come within the compass of our mental powers; and it was the duty of philosophy to destroy the illusions which had their origin in misconceptions, whatever darling hopes and valued expectations may be ruined by its explanations. — Kant

And then the beginning of the introduction:

Kant points out that moving from what I'd call naive realism requires 'long practice' and skill. That the empiricists should have accidentally left some of the work of their own minds 'projected' is no surprise. And those who came after Kant criticized him. What we have is an evolving theory of the 'lens' and how it structures the given into experience. Kant aimed at one fixed lens. Others later held to the lens metaphor but insisted that the lens changed with time. Heidegger and Wittgenstein presented something like a soft and evolving lens that we could never quite grasp explicitly and/or comprehensively.That all our knowledge begins with experience there can be no doubt. For how is it possible that the faculty of cognition should be awakened into exercise otherwise than by means of objects which affect our senses, and partly of themselves produce representations, partly rouse our powers of understanding into activity, to compare to connect, or to separate these, and so to convert the raw material of our sensuous impressions into a knowledge of objects, which is called experience? In respect of time, therefore, no knowledge of ours is antecedent to experience, but begins with it.

But, though all our knowledge begins with experience, it by no means follows that all arises out of experience. For, on the contrary, it is quite possible that our empirical knowledge is a compound of that which we receive through impressions, and that which the faculty of cognition supplies from itself (sensuous impressions giving merely the occasion), an addition which we cannot distinguish from the original element given by sense, till long practice has made us attentive to, and skillful in separating it. — Kant -

The Blind Spot of Science and the Neglect of Lived ExperienceAs far as that which is common to us all that would constitute knowledge that is not learned, but innate; our dissatisfaction with the world as it is, seems to be a norm that binds us all together. Why is it that we all find the state of the world to be disgusting? Wouldn't that point to an innate knowledge? — Cris

I don't think so. I do think we have something like a human nature, and that would serve your purpose. But I don't think we pop out of mother with a set of justified beliefs. We can't even talk yet! And I think that's the gist of what Locke was saying. I'm not born knowing the Pythagorean theorem, but I can of course grow up, see the proof, and agree with all the other grownups that 'of course it's true.'

So I say yes to human nature and of course to being embedded in a culture that makes us intelligible to one another. But I say no to the idea that we don't need to learn a language and train our young brains. Of course our brains are structured in a certain way that allows for creating knowledge, but I wouldn't call that potential for learning the knowledge itself. -

The Blind Spot of Science and the Neglect of Lived ExperienceSome say the universe is made of atoms, but I say it is made of stories. — Cris

Hi. I like this. Yes, the world is made of stories...and atoms and windmills and smiles and toothaches and mothers and trapezoids and...

I have never seen an atom. I simply believe the story I was told. This is the case for all I know. No on has ever seen the continents drift from a single land mass to where we ae now. People found a bunch of bones and stones and pieced togehter a story. No one has ever seen the big bang. They observed things and did some math and then told the story that they believe and now so do I. — Cris

Yup. I agree. We mostly just get stories. But I have flown to New York in a few hours. I was up in the clouds. The story of atoms gets our attention because it is connected to events like these. Of course there are profound internal experiences associated with religious stories, but those experiences are more elusive. So religious stories are more controversial.

We compile the stories and form our worldview. If the stories are harmonious then they are more believable and we enter them in as knowledge. If they are not compatible then one must go and we will look for anoter to fill its place. That seems to be the scientific method. — Cris

I think you describe the way humans think in general.

The observable process which Schiller and Dewey particularly singled out for generalisation is the familiar one by which any individual settles into new opinions. The process here is always the same. The individual has a stock of old opinions already, but he meets a new experience that puts them to a strain. Somebody contradicts them; or in a reflective moment he discovers that they contradict each other; or he hears of facts with which they are incompatible; or desires arise in him which they cease to satisfy. The result is an inward trouble to which his mind till then had been a stranger, and from which he seeks to escape by modifying his previous mass of opinions. He saves as much of it as he can, for in this matter of belief we are all extreme conservatives. So he tries to change first this opinion, and then that (for they resist change very variously), until at last some new idea comes up which he can graft upon the ancient stock with a minimum of disturbance of the latter, some idea that mediates between the stock and the new experience and runs them into one another most felicitously and expediently.

This new idea is then adopted as the true one. It preserves the older stock of truths with a minimum of modification, stretching them just enough to make them admit the novelty, but conceiving that in ways as familiar as the case leaves possible. An outrée [outrageous] explanation, violating all our preconceptions, would never pass for a true account of a novelty. We should scratch round industriously till we found something less eccentric. The most violent revolutions in an individual’s beliefs leave most of his old order standing. — James -

The Blind Spot of Science and the Neglect of Lived ExperienceThe problem with Cartesian dualism is the very idea of there being a 'thinking substance'. It is an impossible abstraction, and has lead to enormous confusion. Husserl has a great criticism of that in Crisis of European Sciences. — Wayfarer

Well I agree that Cartesian dualism, like IMV every exact metaphysical system, falls apart upon close examination. It gets something right at the cost of getting something wrong. Our language is too fluid and complex to model itself in an artificial structure.

I'd say that the notion of a thinking substance was anything but arbitrary. It sounds like a soul. And it gets the part of us that quietly talks to ourselves right. But indeed it is an impossible abstraction. All brittle systems crumble, and systems are brittle IMV because they imagine that concepts are like distinct crystals. And that distinctions are perfect rather than approximate.

This is from 'the antinomies of reason'. It is about the fact that there are questions traditionally regarded as metaphysical, which can never be resolved, like whether the world has a beginning or whether there is a first cause. — Wayfarer

Yes, and you mention one of my favorite antinomies. Kant made it obvious that human cognition has glitches like that.

Right - there's a succinct statement of the 'blank slate'. — Wayfarer

But it's so harmless in context, at least to me.

t is extremely complicated, but the fact remains that 'empiricism' means 'demonstrable in objective experience', right? — Wayfarer

I think I know what you mean, but empiricism means (roughly) 'a philosophical belief that states your knowledge of the world is based on your experiences, particularly your sensory experiences. According to empiricists, our learning is based on our observations and perception; knowledge is not possible without experience.' So it's more general than that.

I do associate science with demonstration via objective/unbiased experience.

It can be distinguished from philosophical reasoning that is aimed at effecting a transformation of insight, as was traditional philosophy; science is results-oriented and instrumental in nature. Not wrong on that account, but also not necessarily efficacious in any sense other than those. — Wayfarer

I agree, but I think that some tie their sense of the spiritual to it. As we've discussed, unbiasedness is also a spiritual concept. I also suggest that engineering can be experienced as art. We love beautiful machines, powerful machines, ...

I don't think it's all or nothing. One can 'live in the world' as many a good Christian, Buddhist or Hindu might do, but still feel that sense of the radical insufficiency of natural life. — Wayfarer

I agree that it's not all or nothing. -

The Blind Spot of Science and the Neglect of Lived ExperienceIt is said that 'science relies on reason' but really it relies even more on what is tangible or instrumentally-detectable; it is nothing like rationalism in the sense that a Leibniz or rationalist philosophy understands, which sought to intuit an order wholly transcending the order of the sense; something which is practically unintelligible to a modern. — Wayfarer

Isn't it more complicated than that?

Hypotheses are often created in an unwordly language of pure form. Of course they are tested in terms of the tangible, but atoms for instance are beyond the order of sense. QM doesn't even make sense (" I think I can safely say that nobody understands quantum mechanics.") So we trust and use patterns in measurements that we can't ground in intuition.

But look at the role of observability in empirical science - the yardstick of what is real, is what can be ascertained by sensory experience, amplified by instruments, and mathematical abstraction thereof. — Wayfarer

Well empirical means (roughly) 'based on, concerned with, or verifiable by observation or experience rather than theory or pure logic.' So, yes, empirical science is concerned with the observable. As far as leaving rationalist philosophy behind, well that makes sense.

We've talked about the quest for unbiasedness. A careful measurement is just about as unbiased as it gets for us humans. Eternal truths revealed to intuition are problematic, probably because people don't agree about these universal truths.

If you claim that, given measurement x at time t_0, I should expect measurement y at time t_1, then you have truly said something definite. In a world of so much confusion and wishful thinking, this is beautiful.

For me man is the metaphysical animal and philosophy is an ultimate treasure, but science by reducing its project in some sense gains something that philosophy can't offer. -

The Blind Spot of Science and the Neglect of Lived ExperienceGod is not the creator deity of the universe and mankind, but man's true nature and the norm of all things, in general. The moral and religious conscience live in the consciousness of the contrast between this norm (Realität) and empirical reality (Wirklichkeit)

I've held a theory like this for quite a while, and it's not far from Feuerbach's humanism. But clearly we don't have consensus about this norm. This site is largely about presenting, comparing, attacking, and defending proposed norms.

The general structure of having a norm ('the sacred') does seem innate.

The religious perceive our present life, or our natural life, as radically deficient, deficient from the root (radix) up, as fundamentally unsatisfactory; he feels it to be, not a mere condition, but a predicament; it strikes him as vain or empty if taken as an end in itself; he sees himself as homo viator, as a wayfarer (!) or pilgrim treading a via dolorosa through a vale that cannot possibly be a final and fitting resting place; he senses or glimpses from time to time the possibility of a Higher Life; he feels himself in danger of missing out on this Higher Life of true happiness. — Bill Vallicella

This is a fascinating quote, but note that it frames the religious person in terms of longing, sorrow, and fear who merely glimpses something Higher now and then. What is not mentioned is a general sense of well-being. To be sure there is plenty of vanity in the world, but we can choose our spouses, friends, books, etc. Can we not get better at life as we get better at riding a bike?

I do like the 'wayfarer' metaphor. And I agree that the intensity of 'spiritual' experience is not constant. Peak moments come and go. But I'm personally more anti-anti-worldly than anti-wordly. As far as I know this is the one world and one life that I actually have. My thinking is that we transcend vanity by identifying with what all good people have in common. We meet in our profound myths, thoughts, rituals, works of science, works of art in different media, etc. -

The Blind Spot of Science and the Neglect of Lived ExperienceNote the difference between hylomorphic and Cartesian dualism. The former never conceived of 'the soul' as a substance, or something that exists over and above the body. In a sense, Aristotle's intuition is that the soul is the unity of the body. — Wayfarer

OK, yes I see the difference. But I had the impression that you liked both forms of dualism. In James and Mach we have elements of informed matter but no witness. -

The Blind Spot of Science and the Neglect of Lived Experienceot 'a mess of sensations' but the 'tabula rasa' principle of Locke was and is a firm dogma of empiricism. — Wayfarer

First, to argue for the continuity I mentioned, I quote from Locke and Kant.

Since it is the understanding, that sets man above the rest of sensible beings, and gives him all the advantage and dominion, which he has over them; it is certainly a subject, even for its nobleness, worth our labour to inquire into. The understanding, like the eye, whilst it makes us see and perceive all other things, takes no notice of itself; and it requires art and pains to set it at a distance, and make it its own object.

...

If, by this enquiry into the nature of the understanding, I can discover the powers thereof; how far they reach; to what things they are in any degree proportionate; and where they fail us: I suppose it may be of use to prevail with the busy mind of man, to be more cautious in meddling with things exceeding its comprehension; to stop when it is at the utmost extent of its tether; and to sit down in a quiet ignorance of those things, which, upon examination, are found to be beyond the reach of our capacities. We should not then perhaps be so forward, out of an affectation of an universal knowledge, to raise questions, and perplex ourselves and others with disputes about things, to which our understandings are not suited; and of which we cannot frame in our minds any clear or distinct perceptions, or whereof (as it has perhaps too often happened) we have not any notions at all. — Locke

Human reason, in one sphere of its cognition, is called upon to consider questions, which it cannot decline, as they are presented by its own nature, but which it cannot answer, as they transcend every faculty of the mind.

It falls into this difficulty without any fault of its own. It begins with principles, which cannot be dispensed with in the field of experience, and the truth and sufficiency of which are, at the same time, insured by experience. With these principles it rises, in obedience to the laws of its own nature, to ever higher and more remote conditions. But it quickly discovers that, in this way, its labours must remain ever incomplete, because new questions never cease to present themselves; and thus it finds itself compelled to have recourse to principles which transcend the region of experience, while they are regarded by common sense without distrust. It thus falls into confusion and contradictions, from which it conjectures the presence of latent errors, which, however, it is unable to discover, because the principles it employs, transcending the limits of experience, cannot be tested by that criterion. — Kant

As for the blank slate, let's look closer:

For, first, it is evident, that all children and idiots have not the least apprehension or thought of them; and the want of that is enough to destroy that universal assent, which must needs be the necessary concomitant of all innate truths: it seeming to me near a contradiction, to say, that there are truths imprinted on the soul, which it perceives or understands not; imprinting, if it signify any thing, being nothing else, but the making certain truths to be perceived. [15] For to imprint any thing on the mind, without the mind’s perceiving it, seems to me hardly intelligible. If therefore children and idiots have souls, have minds, with those impressions upon them, they must unavoidably perceive them, and necessarily know and assent to these truths: which since they do not, it is evident that there are no such impressions. For if they are not notions naturally imprinted, how can they be innate? and if they are notions imprinted, how can they be unknown?

...

To avoid this, it is usually answered, That all men know and assent to them, when they come to the use of reason, and this is enough to prove them innate. I answer,

Doubtful expressions that have scarce any signification, go for clear reasons, to those, who being prepossessed, take not the pains to examine, even what they themselves say. For to apply this answer with any tolerable sense to our present purpose, it must signify one of these two things; either, that, as soon as men come to the use of reason, these supposed native inscriptions come to be known, and observed by them: or else, that the use and exercise of men’s reason assists them in the discovery of these principles, and certainly makes them known to them.

If they mean, that by the use of reason men may discover these principles; and that this is sufficient to prove them innate: their way of arguing will stand thus, (viz.) that, whatever truths reason can certainly discover to us, and make us firmly assent to, those are all naturally imprinted on the mind; since that universal assent, which is made the mark of them, amounts to no more but this; that by the use of reason, we are capable to come to a certain knowledge [17] of, and assent to them; and, by this means, there will be no difference between the maxims of the mathematicians, and theorems they deduce from them; all must be equally allowed innate; they being all discoveries made by the use of reason, and truths that a rational creature may certainly come to know, if he apply his thoughts rightly that way.

...

That certainly can never be thought innate, which we have need of reason to discover; unless, as I have said, we will have all the certain truths, that reason ever teaches us, to be innate.

...

So that to make reason discover those truths, thus imprinted, is to say, that the use of reason discovers to a man what he knew before: and if men have those innate impressed truths originally, and before the use of reason, and yet are always ignorant of them, till they come to the use of reason, it is in effect to say, that men know, and know them not, at the same time.

...

The senses at first let in particular ideas, and furnish the yet empty cabinet; and the mind by degrees growing familiar with some of them, they are lodged in the memory, and names got to them. Afterwards the mind, proceeding farther, abstracts them, and by degrees learns the use of general names. In this manner the mind comes to be furnished with ideas and language, the [21] materials about which to exercise its discursive faculty: and the use of reason becomes daily more visible, as these materials, that give it employment, increase. But though the having of general ideas, and the use of general words and reason, usually grow together; yet, I see not, how this any way proves them innate. The knowledge of some truths, I confess, is very early in the mind; but in a way that shows them not to be innate. — Locke

I recently read Locke for the first time, and I found him pretty likable. -

The Blind Spot of Science and the Neglect of Lived ExperienceSo this is hylomorphic dualism, matter-form dualism, and I have to confess, it makes sense to me. — Wayfarer

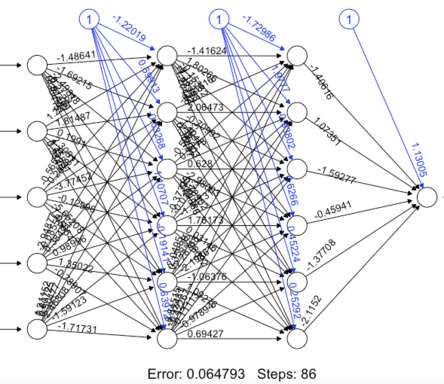

I think it gets quite a bit right. One of the classic neural network problems is deciding whether an image contains a cat or not. This task was out of reach for a long time, and yet it's so easy for humans. It's only in reach now because we have enough computational power to represent the concept of a cat as a massive spiderweb of floating point numbers whose structure is inspired by brains. And because we expose that computer to many labelled examples.

We also have clustering algorithms that (roughly) divide a world of experience into objects, which is like concept creation. I don't think computers see red or see concept, to be clear. I'm just saying that there is a mathematical pattern associated with human conceptuality. -

The Blind Spot of Science and the Neglect of Lived ExperienceI think is a strong case for a form of dualism. — Wayfarer

I find dualism to be roughly true. On the one hand we perceive redness. On the other we determine the radiation associated with this perception to have a frequency of 710 nm.

To me it's clear as day that redness is not frequency. It may be a beetle in a box, but it's my beetle, and I think it's other people's beetle too.

https://existentialcomics.com/comic/6

“Abstraction, which is the proper task of active intellect, is essentially a liberating function in which the essence of the sensible object, potentially understandable as it lies beneath its accidents, is liberated from the elements that individualize it and is thus made actually understandable. The product of abstraction is a species of an intelligible order. Now possible intellect is supplied with an adequate stimulus to which it responds by producing a concept.” — link

Yes, this sounds right to me.

Just as I see redness, my intellect 'sees' circularity or a cat and not a dog. -

The Blind Spot of Science and the Neglect of Lived ExperienceActually in pretty close agreement with James, but would parse it differently.

'Thoughts' are not objects as such; objects exist in thought, or rather, in mind, but you can't be discursively aware of that, because you can't step outside mind or treat mind as an object, as it never is an object. — Wayfarer

I agree with you in a common sense way, but I think this misses James' point. For him the 'mind' is one more object in a nexus of objects. Objects are thoughts and thoughts are objects. They are pieces of formedexperience.There is no witness left over, only what the hypothesized witness was supposed to be witnessing. The witness is one more thought/object.

For common sense the thought of an apple is not itself an apple. For James these are both just object-thoughts with a similar but still different form.

I'd really have to writeobjectsandthoughts.Because we have left mind and matter behind in such a wild theory. We have to climb the ladder of the witness and the witnessed to get there. And really we've just climbed up to an unsustainable speculative truth, since we are sure to come down.

The radical anti-realist don't just insist that the lens is unstable, they deny the lens metaphor altogether and get a 'subject-object.' -

The Blind Spot of Science and the Neglect of Lived ExperienceAnd while the faculty of reason is certainly something that evolved, what is discerned by reason didn't evolve; I mean, the 'law of the excluded middle' didn't come into being when we evolved to perceived it; what evolved was our capacity to perceive it. And this is something I don't believe the empiricist philosophers would agree with. — Wayfarer

This is a great issue. I'm not a mathematical Platonist, but I experience a shared realm. For me it's plausibly explained as a blend of subitizing, spatial intuition, and metaphor. I don't know how we can see around our own cognition to check whether what is discerned by reason evolved.

I postulate a biological, cultural, and personal lens through which we experience reality. It seems that anything added by the biological lens would be hard to isolate. The 'beetle in the box' video I posted in reply to @leo also suggests that we could only infer a similar understanding in aliens, for instance, indirectly or through their behavior. Consider receiving this message from outer space:

||, |||, |||||, |||||||, |||||||||||, .... [2,3,5,7,11,...]

We'd infer that something out there grasped both natural numbers and what it means for a number to be prime. That would at least suggest similar cognitive structure. -

The Blind Spot of Science and the Neglect of Lived ExperienceThe stroke of genius of atomism was that 'the changeless' could be understood as the fundamental element of everything; that whilst the atom remained indivisible and eternal in itself and so, like the One, it could at the same time combine in countless ways to produce the 'ten thousand things', so resolving the paradox. — Wayfarer

It really was a work of genius.

I think that intuition remains behind atomism but the original philosophical inspiration long forgotten, as it still preserved the division between 'the uncreated' (unconditioned, unmade, unfabricated) and 'the manifest realm'. So now the original appeal of atomism has been forgotten, but it wanted to discern the bedrock, the basis, the fundamental ground from which everything appears. — Wayfarer

To me the mystique of physics in particular is still connected to this. Even those who don't want to learn physics still perhaps enjoy their image of it.

Then I noticed how much evolutionary paradigms had seeped into all kinds of philosophical problems - that everything could be understood through the lense of evolutionary biology - including Mach, by the way. — Wayfarer

Indeed, though I think the historical evolution of ideas was noticed first.

Relying on a complex etymology, Vico argues in the Scienza Nuova that civilization develops in a recurring cycle (ricorso) of three ages: the divine, the heroic, and the human. Each age exhibits distinct political and social features and can be characterized by master tropes or figures of language. The giganti of the divine age rely on metaphor to compare, and thus comprehend, human and natural phenomena. In the heroic age, metonymy and synecdoche support the development of feudal or monarchic institutions embodied by idealized figures. The final age is characterized by popular democracy and reflection via irony; in this epoch, the rise of rationality leads to barbarie della reflessione or barbarism of reflection, and civilization descends once more into the poetic era. Taken together, the recurring cycle of three ages – common to every nation – constitutes for Vico a storia ideale eterna or ideal eternal history. — Wiki

I think someone before Vico already thought as much, but Vico came to mind.

That is why the predominant materialism of secular culture is based in neo-Darwinism; it's kind of a 'reverse fundamentalism', as it believes that evolutionary theory debunks the religious account of creation. But it only does that if you first believed that the religious account was literally true; if you've never thought it was literally true (as I did not) then the fact that it's *not* literally true has no significance. — Wayfarer

I hear you. For me the gap is between religion that experiences God as an invisible person who sees inside one's heart and does miracles and other more abstract versions of God. More abstract versions of God aren't controversial, as far as I can see, but somewhere between myth and metaphysics. I call myself an atheist because it's the least confusing word I could choose, but I think the myths are profoundly true in ways I would not defend with arguments.