-

Creativity: Random or deterministic? Invention or discovery?Does Clavius' Law save you from all contradictions? — Luke

Clavius' Law says that "if (not-P implies P) then P".

In this case P is it is impossible to invent an idea.

So:

If

(it isnot impossible to invent an idea implies it is impossible to invent an idea)

then

it is impossible to invent an idea -

Why do you post to this forum?To learn (seeking knowledge) and to teach (making a change), both of them by talking with others, either of which gets me attention, and which justify my views in different senses of that phrase: the former in the sense of acquiring reasons to hold views (adjusting my views in the process to accord with those reasons), the latter in the sense of displaying the reasons to hold my views.

-

Is anyone here a moral objectivist?Please keep going, you’re making lots of great points.

-

Is anyone here a moral objectivist?You can have context-independence, or you can have observer-dependence. I don't think both is logical. — Kenosha Kid

Not sure if you made a typo here, but objectivism as I mean it is context-DEpendent but observer-INdependent. -

Clothing: is it necessary?I always figured the religious prohibition against nudity was related to the broader religious obsession with sex as an object of moral concern. Naked is sexy and sexy is sinful therefore naked is sinful.

Religions are generally completely wrong about the morality of sex though, so they’re also wrong about the morality of nudity. There’s nothing wrong with it. -

Would you like some immortality maybe?The best thing is choice. To be able to live forever is good. To be forced to live forever is bad.

And because dying removes choices -- you can't change your mind when you're dead -- for someone to want to live, to desire life, for life to seem good, which is basically what it means to be happy, is good. The highest good is for life to be worth living and available to be lived.

Also, so long as you're alive, there's always the possibility of changing from sadness to happiness. The same is not true when you're dead. -

Mentions over commentsI kind of wonder how this ratio scales with the number of comments.

As in, what's your mentions/(comments^2)? Mine is 0.344_. -

Is there a good political compass?Wikipedia has a whole article on different varieties of them and the academic research (or lack thereof) backing them up:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Political_spectrum

Another well-known one besides that political compass you linked is the Nolan Chart, which also has a quiz that will place you on it, but I won't link to it here because I think it's a poorly constructed and biased spectrum. Google "World's Smallest Political Quiz" if you really want to try it.

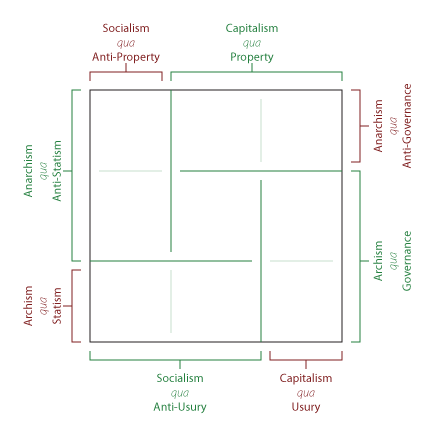

I have a political spectrum of my own, inspired in part by both of the aforementioned, but with adjustments:

-

Mentions over commentsI've usually hovered at close to 1. Currently I'm at about 1.03 (3.1K/3K). Usually it's slightly above 1 like that.

I've often wondered what that ratio suggests about a poster, so this is an interesting thread.

Also, there doesn't seem to be a way to see your number of mentions on mobile, as far as I can tell. -

Risks and impositionsThis question seems to presume that we are already in the business of punishing people for doing things without asking for permission first. Licensure like that is contrary to liberty and serves no useful purpose. Someone who does something without license can still cause harm, and should still be held responsible for that harm (make restitution) regardless of their prior license. Likewise someone may do something without license and cause no harm, and they should not be punished just for failing to ask permission first.

Just require everyone make restitution for any harm they cause, and the magnitude and likelihood of that harm their activities might cause (and thus the potential cost to themselves) will serve as exactly proportional deterrence for those actions. -

The meaning of the existential quantifierBut there is still a difference right? If you're a coyote, you're always a coyote, wherever you go and whatever you do. If you're howling, that's a temporary state. When a coyote dies, there is one less coyote in the world, though others are probably added. When something stops howling, does a howling thing blink out of existence? There is one less howling thing in the world, okay, but wouldn't we rather just say that fewer of the things in the world are howling? And same for the converse: it's not that a thing that is howling springs into existence; one of the things already here begins howling. If that thing is a coyote, it was already a coyote, and doesn't begin being a coyote at the same time it begins howling. — Srap Tasmaner

In a sense, one could say that when a coyote dies, that matter stops doing whatever it was that constituted being a coyote. The matter still exists, it just stopped doing something. To be is to do. -

The meaning of the existential quantifierIn my related thread on a sole sufficient quantifier, I set forth a way where this whole bounded quantification thing has to be addressed explicitly:

The for() function that takes three arguments, the first being a set of values that some variable can take to satisfy some formula, the second being that variable, and the third being that formula. (This would then be read as "for [these values of] [this variable], [this statement involving that variable] (is true)").

This replicates some of functionality of another function frequently used together with the traditional quantification operators, ∈, which properly indicates that whatever is on the left of it is a member of the set on the right of it, but together with the existential operators is often used to write things like

∀x∈S...

meaning "for every x in set S...", meaning that only the members of S satisfy the formula to follow. Expressions like the usual

∃x∈S...

(meaning "for some x in set S...") can also be formed, with this function, by using the equivalent of an "or" function on the set in the first argument of for(), to yield an expression meaning "some of this set". — Pfhorrest -

The meaning of the existential quantifierIn my system of logic, the “over there” would be conveyed through a modal operator “at()”: it would basically be analyzed as “at there, for a non-zero number of dogs, dogs are barking”. (Or rather, accounting for the abstraction of assertive force out into mood operators, "there is, at there, for a non-zero number of dogs dogs, dogs being barking").

-

A sole sufficient quantification function: for()This is a generalization that can express a lot more than either ∀ or ∃. It can select an arbitrary quantity: you can punch in an exact number of things you want, not just "some". It just happens that if that number is zero, you've got the same as "not some" (i.e. none), which you can negate to get "some" (∃) and from there "all" (∀) and "not all".

The sole sufficient operator for modality was really a lot more interesting (see the other thread). I admit that this topic is boring in comparison. -

Marx and the Serious Question of Private PropertyI wonder sometimes if those at the top of the hierarchy really do believe in climate change, and believe that it's already too late, and are just determined to stay on top and in their lives of luxury until the bitter end. They're all old anyway, so their bitter end is coming soon one way or another.

-

Self sacrifice in the military or just to save the life of one other.How to you explain greater legacy as a consequence of dying sooner? How would the length of one's life have anything to do with "legacy?" Does it relate to a culture of honoring those who sacrifice their lives to their country? Why should anyone care about legacy? — Nils Loc

By "legacy" I mean whatever impact you leave behind on the world. If you can do something good with your life, but doing that will make it shorter, I can see why someone would choose that.

Say you have a choice between:

1) live another 40 years until your natural death, and shortly after that, events already in motion (details unimportant) will lead to the collapse of civilization, worldwide suffering, and the eventual (but not too distant) extinction of all life on Earth.

2) do something that will prevent all that and allow life and civilization to flourish far into the future, at the expense of you dying in the process, 40 years sooner than you otherwise would have.

I can see it being a rational choice (but by no means an obligatory one) to pick option 2.

But as I said before, I absolutely don't think military service is "doing something good with your life", the likes of which justifies sacrificing the rest of it. I'm just talking about the general principle, not this specific case. -

Natural Evil ExplainedIf God is incapable of pain, then yes, his POV on morality will lack a component that is crucial to ours. — bert1

God could be incapable of his own pain but understand what pain for others is and think it bad.

The relativist theist does not have to say God's POV is the right one, though. It's right for God, but right not from our point of view. — bert1

Theists tend not to be relativists, though. Especially not the kind who claim that God is omnibenevolent.

For an omnipotent being, whatever is, is good. Because if it wasn't good, it could not exist. For an omnipotent being to not will something is for that something not to exist. God's omnibenevolence just follows from God's omnipotence. — bert1

It’s true that whatever an omnipotent being wants is what will be real, but it’s still an open question whether what that being wants is good. Even if you were somehow a relativist theist, who holds that wanting something just is it being good (for you), all you end up saying is that God wants what he wants, but it’s an open question whether he wants we want, and so whether he is “good” in the sense that we mean.

As I think we may already agree (not sure) what is good just is what is willed. — bert1

I agree that to will something and to think it is good are the same thing, but thinking something is good is not the same thing as it being actually good. -

Natural Evil ExplainedPerhaps because suffering is morally irrelevant from God's POV. — bert1

That would suggest that God’s POV on morality is completely alien to ours, or conversely (since presumably God’s POV is right), that we have absolutely no idea what it really means for something to be moral. Which then raises the question of what we’re even saying when we say that God is omnibenevolent. -

Self sacrifice in the military or just to save the life of one other.If one believes there is no actual life after death, and everyone dies eventually, then all that survives anyone is their legacy, so dying sooner rather than later in exchange for a greater rather than lesser legacy makes a kind of rational sense.

Military service is not generally a great way to leave a positive legacy, though. -

Is Epiphenomenalism self-contradictory?I think this is a good argument against epiphenomenalism, but I imagine the epiphenomenalist would say in response that epiphenomena correspond to physical phenomena, and it is the physical phenomenon whose epiphenomenon is pain (some brain state, say) that causes us to say “I’m in pain”. It might be, they would say, that there could be a philosophical zombie with all the same physical stuff going on who reports that it’s in pain, but doesn’t actually have the epihenomenon of really feeling pain.

I would ask them in turn why we need to posit epiphenomena at all; why can’t the physical stuff doing the causing also be having the experience by itself? -

Intellectuals and philosophers, do you ever find it difficult to maintain relationships?For my part, after I outgrew my social ineptitude and learned how to be a popular person with lots of friends and dating all the time etc, I soon learned that it’s more often than not simply not worth the effort. I don’t get enough out of most social interactions for it to be worth the time and emotional energy it takes to cultivate them well.

I’ve got one deep relationship with my girlfriend of the past 8 years, and a handful of deep intellectual long-term friends on the internet who supplement what I don’t get from her. That’s enough. And maintaining those relationships isn’t especially hard, no more than most relationships between most people; we have problems but we work through them.

Everyone else, people I just see around places, I get along with them, I’m nice to them, they seem to like me, and ones I see frequently I’d even consider friends, but those are all effortless shallow friendships of acquaintance: people who just happen to be there a lot. -

The way to socialist preference born in academical home(summary in first post)I struggle to understand why a contract that is voluntarily agreed upon by two mentally capable individuals would be deemed invalid, except for perhaps contracts that result in direct physical harm (or are made under threat thereof). Is this to protect individuals from their own bad decisions? — Tzeentch

It’s basically a matter of one’s power to contract (or not) being inalienable. Nobody has the power to agree to agree (or not) to any change of rights or ownership, such as by agreeing not to enter into other contracts (as in non-compete agreements), or agreeing to accept whatever terms the other party later dictates (as in selling oneself into slavery, or as in the "social contract" sometimes held to justify a state's right to rule), or agreeing to grant someone a temporary liberty upon certain conditions ("selling" someone the temporary use of your property, as in contracts of rent or interest; letting someone do something is not itself doing something).

In short, the power to contract must be limited to the simple trade of goods and services, and cannot create second-order obligations between people that place one person in a position of ongoing power over another person. — Pfhorrest

Thinking about how to explain this more clearly helped me come up with a... well, a clearer way of explaining it, which is very useful for me for my philosophy book where I write about this stuff, so thanks again for this conversation.

This explanation depends on the precise technical terms used in a Hohfeldian analysis of rights, so I'll quote an earlier post from myself in this thread first, where I summarize those:

(In Hohfeldian terms, a liberty is something that you are not prohibited from doing. It is the negation of the obligation of a negation, and so it is equivalent to a permission. A claim, conversely, is a limit on others' liberty: it is something that it is forbidden to deny you, which is just to say that it is obligatory. A power is the second-order liberty to change who has what rights. And an immunity, conversely, is a limit on others' power, just as a claim is a limit on others' liberty.)

At first glance, one would think a maximally libertarian society would be one in which there were no claims at all (because every claim is a limit on someone else's liberty), and no powers at all (because powers at that point could only serve to increase claims, and so to limit liberties). But that would leave nobody with any claims against others using violence to establish authority in practice even if not in the abstract rules of justice, and no claims to hold anybody to their promises either making reliable cooperation nigh impossible. So it is necessary that liberties be limited at least by claims against such violence, and that people not be immune from the power to establish mutually agreed-upon obligations between each other in contracts.

But those claims and powers could themselves be abused, with those who violate the claim against such violence using that claim to protect themselves from those who would stop them, and those who would like for contracts not to require mutual agreement to leverage practical power over others to establish broader deontic power over them. So too those claims to property and powers to contract, which limit the unrestricted liberty and immunity that one would at first think would prevail in a maximally libertarian society, must themselves be limited. — Pfhorrest

The limitation on the claim to property is already well-understood and I think agreed upon here: you can't call foul when someone else coerces you into not coercing someone, as in if they're fighting back against you attacking them; your claim against trespass upon your body is waived to the extent necessary to stop you from trespassing upon someone else's.

It's the analogous limit on the power to contract that's at issue here, and the clearer explanation of that that I just came up with is:

- You have the power to waive specific claims — which is just to transfer away your ownership of things.

- You have the power to waive specific liberties — which is just to take on obligations to do or not do things.

- But you do not have the power to waive your immunities — to transfer away your power to change your first-order rights as above.

- And you do not have the power to waive your powers — to take on obligations to permit or not permit things.

Those limits have far-reaching implications on many kinds of things, but their specific implication on rent and interest is that you don't have to power to take on an obligation to permit someone to use your property -- so long as it is your property, you have the right to decide whether or not someone is permitted to use it, and you can't take on an obligation to permit it, except by making it no longer your property, and therefore not subject to your permission at all. Since you can't take on an obligation to permit the use of your property, you can't sell such an obligation to someone; which means you can't rent out your property. You can allow someone to use your property, and they can give you money, but they can't validly buy a right to use your property against your future will, which makes the whole institution of rent completely insecure and unfeasible as a widespread economic instrument.

The natural alternatives to it in a free market have the socialist consequences already explained earlier. - You have the power to waive specific claims — which is just to transfer away your ownership of things.

-

I Ching and DNASorry, I don't mean to be dismissive of the I Ching generally -- although I don't put any stock in it, but it's interesting, and dismissing it wasn't my point.

My point was just that 64 codons of DNA and 64 I Ching hexagrams is a completely unsurprising coincidence, because there are 4 DNA bases (A, C, T, and G) and codons are have length 3, so 4^3 = 64, while hexagrams have two bases (sometimes written 1 and 0) and hexagrams have length 6, so 2^6 = 64 as well. It's unsurprising that 4^3 = 2^6 because 4 = 2^2, so 4^3 = (2^2)^3 = 2^6.

The number of triplets of classical western elements (earth, air, wind, and fire) is also equal to the number of chords it's possible (if not advisable) to play on a six-string guitar, for exactly the same reason. (And the number of each is exactly the same: 64). -

I Ching and DNAThe binary representation of I Ching hexagram 63, “chi chi” or “after completion”, symbolizing a state of totality, is 101010, which is also the binary representation of the decimal number 42, which according to The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy series is “the answer to life, the universe, and everything”, the corresponding question to which is “what do you get when you multiply six by nine”, which is totally true if you do your multiplication in base 13, but that’s a completely unintended coincidence... just like everything in this thread.

-

The way to socialist preference born in academical home(summary in first post)I struggle to understand why a contract that is voluntarily agreed upon by two mentally capable individuals would be deemed invalid, except for perhaps contracts that result in direct physical harm (or are made under threat thereof). Is this to protect individuals from their own bad decisions? — Tzeentch

It’s basically a matter of one’s power to contract (or not) being inalienable. Nobody has the power to agree to agree (or not) to any change of rights or ownership, such as by agreeing not to enter into other contracts (as in non-compete agreements), or agreeing to accept whatever terms the other party later dictates (as in selling oneself into slavery, or as in the "social contract" sometimes held to justify a state's right to rule), or agreeing to grant someone a temporary liberty upon certain conditions ("selling" someone the temporary use of your property, as in contracts of rent or interest; letting someone do something is not itself doing something).

In short, the power to contract must be limited to the simple trade of goods and services, and cannot create second-order obligations between people that place one person in a position of ongoing power over another person.

Maybe you could elaborate a bit further on this, because I don't think I fully understand what you mean. Should everything I have no use for then belong to someone who does have a use for it? — Tzeentch

Both the usual type of socialist and I say yes. The differences between us are in how that comes about. The usual type of socialist says basically that use just is ownership, so something you’re not using just doesn’t belong to you.

I say instead that the legal framework ought to be such that there is no incentive to own things you aren’t using, i.e. there should be no way to profit simply from ownership, leaving the most profit you can get from it as just the proceeds from the sale of it. And since nobody else has motive to buy something they’re not going to use themselves, the market you would have to sell to would only be people who have a use for it. So making absentee ownership not profitable encourages the voluntary transfer of property from those who have more than they need for their own use to those who have less than they need for their own use. -

What am I now? - I can't even pigeon-hole myself anymore . .Libertarian socialist / anarcho-socialist sounds right to me, plus techno-progressive and maybe anarcho-environmentalism.

-

The meaning of the existential quantifierAre you just concerned about (not) making metaphysical commitments when we write formulas? — SophistiCat

Yes. -

The way to socialist preference born in academical home(summary in first post)When someone pays a landlord so they can live on their property, it is implied in the agreement that whenever they can no longer pay the landlord, they can no longer live on their property. Presumably, they know the terms of the agreement beforehand, and voluntarily choose to go ahead with it.

The same seems to be true for the workplace example. One makes a voluntary agreement with the workplace owner to do labour in exchange for wages. — Tzeentch

The true voluntariety of these agreements is something that socialists generally dispute, as there generally is not a reasonable alternative for many people besides to accept one of several largely indistinguishable bad deals. I don't want to rent from anybody, for instance, but my only practical options are to rent a house from somebody, or rent money from the bank with which to mortgage a house from somebody. I don't want to do any of those things, but I don't have enough money to do none of them, so I pick the one that sucks the least. "Your money or your life" is still a choice, but "your life" is not a reasonable choice, which is what makes that "choice" actually coercion.

There's also a question of what kind of agreements (contracts) should be valid to begin with. Presumably you would object to an agreement to do whatever somebody else tells you to in perpetuity, i.e. a contract selling oneself into slavery. Unlike most socialists, who reject property and contracts entirely, this is the approach that I take, to reconcile both of those with socialism and equality. I think that there are exceptions to the power to contract, just like there are exceptions to the claim against aggression, in both cases in the reflexive case: the claim against aggression has an exception for people who are themselves aggressing -- I can't attack you and then claim you have no right to fight me off -- and the power to contract has an exception for contracts regarding contractual terms, such as the agreement to do whatever you tell me to in the future, or an agreement to allow you to do something with me or my property (which, being my property, I have a right to exclude you from) whether I like it or not in the future. That last bit means that, among other things, contracts of rent (including interest, which is rent on money) are invalid: "I'll let you use my property" isn't a thing that can be a term of a contract, so you can't contractually owe me money for that "service".

That does mean I can kick you out of the house I was letting you live in... but it also means I have no use for that house that I'm not living in, since I can't contractually obligate anyone to pay me to live there, since I can't legally owe them the right to live there... without just making it their property, that is. So in lieu of being able to rent it out, I would have no better choice but to sell it... and nobody else will be buying it for a rental property, since they can't rent it out either... so I can only manage to sell it on terms that people who would otherwise be renters could afford.

I think that that revision to which contracts are valid would have far-reaching effects that basically incentivize people not to own things besides for their own use, and so achieve socialist ends -- the owners of things are the users of things -- without actually having to directly reassign ownership. -

What happens after you no longer fear death? What comes next?It's a comment on living in the present vs worrying about the future.

Most of my life I had no fear of death, and was also a generally happy person; during a time when I was unemployed and living in a tool shed next to my dad's trailer, someone once asked why I was in such a good mood that day, and I answered simply that I had nothing I needed to be worrying about right then.

As I got older I started worrying more and more and further and further into the future, and I considered this a wise, pragmatic thing. Then last year I was struck for no particular reason with an existential crisis during which I could rarely ever tear my mind off of fixating about the inevitable death of the universe as a whole, not just myself; but myself too, and every other person, animal, etc. (I started being vegetarian then too, because I couldn't stomach food when it reminded me of death; I could barely stomach food at all anyway, from the anxiety).

Part of getting over that crisis was just physiological, which is what I expect brought it on, but another part of it was learning to accept that the future is largely unknown and uncontrollable, and that there is an important balancing point between doing the things you can do, and accepting the things you can't do anything about.

I stopped (for the most part) fixating on the largely uncontrollable high probability of some kind of eventual death at some point, and instead focused on, first, doing whatever things within my control that there were to do to maximize the length and enjoyment of my life, and then, once I had done the things I could do, just enjoying the present moment as much as I can. (E.g. I started doing nature photography while hiking, as a way of drawing my attention to things of beauty around me).

Beyond enjoying myself now, and doing what I can to prolong enjoyment as much as possible, there's a big fuzzy future where I don't know what will happen or what I can do about any of it. And there will always be. Even if we cure aging, go 100% solar, build a Dyson sphere, starlift all the stars and fit them with stellar engines to build some unfathomable contraption to harness all the energy stored in the supermassive black hole at the center of our galaxy, and then in the uncountable *illions of years that that buys us, figure out how to tap dark energy to perpetuate life forever in principle -- there are still always unknowns. And we can't sit paralyzed by them, or else we might, if we are lucky, spend eternity perpetually staring into the abyss of the unknown future that we will never fully illuminate. -

What happens after you no longer fear death? What comes next?After you no longer fear death, you get on with living.

-

The meaning of the existential quantifierThere's some equivalence of course, but I don't think anyone is going to convince mathematicians to quantify over expressions instead of objects. — Srap Tasmaner

I'm not asking mathematicians to change anything at all. I'm just suggesting we interpret the ontological import of the things they write differently.

And of course you trade whatever is a pain-in-the-ass about existence for whatever is a pain-in-the-ass about truth. — Srap Tasmaner

Yes, but that's fine with me, because that's where I think the important discussion need to be had: are all true statements true in virtue of the (non)existence of something, or can there be true statements of kinds that aren't even trying to describe what does(n't) exist? -

The meaning of the existential quantifierThat use is not contrary to what I’m saying at all. In fact it’s a great illustration of the alternative reading of the “existential” operator I’m suggesting: instead of “there exists some x such that [formula involving x] is true”, I suggest “for some value of x, [formula involving x] is true”. The formula involving x may or may not be asserting the existence of anything. If it is, then saying some x satisfies it does assert the existence of something. But if it’s not, then it doesn’t.

-

The meaning of the existential quantifierBut the configuration of prefixes '~∀x~' figures so prominently in subsequent developments that it is convenient to adopt a condensed notation for it; the customary one is '∃x', which we may read 'there is something that'. — Quine, Mathematical Logic

It’s only the very end of this that I have any objection to: reading the DeMorgan dual of universal quantification as asserting that there is (or exists) something. This reading works if, but ONLY if, it occurs in a sentence that is already talking about what does or doesn’t exist. If a sentence is in the business of doing something other than describing, then that reading brings in unnecessary ontological commitments. -

The meaning of the existential quantifierInteresting read. Unlike the Meinongian, or the Quinean interpretation of him at least, I don’t support the use of an existential predicate. Rather, I think only some sentences are in the business of describing reality in the first place, while others instead prescribe, and still others only discuss relationships between ideas without saying either that the world is or that it ought to be any way. In any of these kinds of sentences we can find use for quantifying over variables used in them, whether that quantity be “all” or only “some”.

I had another thread already about a logic for clarifying what kind of sentence we mean to assert, here:

https://thephilosophyforum.com/discussion/9066/logical-mood-functions-and-non-bivalent-logics -

The meaning of the existential quantifierThis reading is inconsistent with how ∃ is actually used in mathematical texts, at least the ones I am familiar with (which would be math textbooks mostly). — SophistiCat

Can you elaborate? -

The meaning of the existential quantifier

I’m not talking about the empty set issue or anything like that. I fully support the standard modern relations between “some”, “all”, and “none”. It is perfect correct in my view to take “some rectangles have equal length legs” as equivalent to “it is not the case that all rectangles have different length legs” or “it is not the case that no rectangles have equal length legs”.

I’m more going on about how “all rectangles have different length legs” fleshes out to “if something is a rectangle then it has different length legs”, and we can affirm or deny that conditional statement without asserting the existence, in any ordinary sense, of any rectangles at all: a disagreement about that conditional is a disagreement about what would count as a rectangle if any such things existed, not about what kind of things exist.

Pfhorrest

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum