-

The methods of justice: "deontology" as "moral epistemology"On Distributive Justice

Just as, like many empiricists, I hold that synthetic a posteriori knowledge, empirical truth, is in a sense the primary kind of knowledge, so too like a good hedonist I also hold that distributive imperfect duties, hedonic goods, are in a sense the primary kind of justice, both in that they are the kind that we are most concerned about in trying to effectively achieve moral outcomes, and in that they are where we get the basic ideas of what seems good or bad that we can then employ introspectively ala "The Golden Rule" in distributive perfect duties.

Though distributive imperfect duties are the kind of greatest concern, being about our lived experience, it is only when we get to perfect duties that we can deal in clear-cut moral obligations, for while all matters of imperfect duty are omissible, which is what makes that duty imperfect, all perfect duty imputes moral obligation. -

The methods of justice: "deontology" as "moral epistemology"On Types of Justice

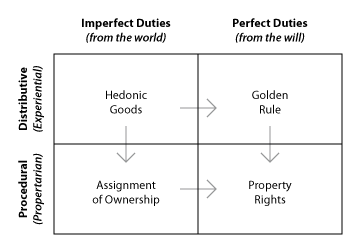

For most of the above I have been implicitly talking about what philosophers call "distributive justice" and "imperfect duties", though most of what I've said applies also to the other kinds of justice and duties I am about to discuss as well. Distributive justice stands in contrast to procedural justice, while imperfect duties stand in contrast to perfect duties.

Procedural justice is about adherence to strict, transactional, rules of behavior, or procedures, while distributive justice is about how value ends up distributed among people as a consequence of whatever behavior. I hold that distinction to be analogous to the epistemological distinction between analytic and synthetic knowledge.

Both procedural justice and analytic knowledge are simply about following the correct steps in sequence from a given starting point to whatever conclusion they may imply, analytic knowledge following just from the assigned meaning of words and procedural justice following just from the assigned rights that who has over what (which I analyze as identical to the concept of ownership, i.e. to have rights over something is what it means to own it).

Likewise both distributive justice and synthetic knowledge are about the the experience of the world, synthetic knowledge about the sensory or descriptive experience of the world and distributive justice about the appetitive or prescriptive experience of the world.

Meanwhile the distinction between perfect and imperfect duties, which was introduced by Immanuel Kant, is roughly the distinction between specific things that we are obliged to always do, and general ends that we ought to strive for but admit of multiple possible means of realization.

I reckon that distinction, in turn, to be analogous to the epistemological distinction between a priori and a posteriori knowledge, because just as a priori knowledge comes directly from within one's own mind (concerning the kinds of things that can coherently be believed) while a posteriori knowledge comes from the outside world, so too perfect duties come directly from within one's own will (concerning the kinds of things that can coherently be intended) while imperfect duties comes from the outside world.

Many liberal or libertarian political philosophers have at least tacitly treated these distinctions as largely synonymous, with procedural justice, matters concerning the direct actions of people upon each other and their property, being the only things about which anyone has any perfect duties, on their accounts; and conversely, distributive justice, matters concerning who receives what value in the end, being at most subject to imperfect duties, if even that.

But I argue that, just as Immanuel Kant showed that the distinction between analytic and synthetic knowledge was orthogonal to the distinction beween a priori and a posteriori knowledge, so too the distinction between procedural and distributive justice is orthogonal to the distinction between perfect and imperfect duties.

At the intersection of matters of distributive justice and perfect duties lies the moral analogue of the synthetic a priori knowledge that Kant introduced. While that synthetic a priori knowledge is about imagining hypothetical things in the mind and exploring what sorts of things could even conceivably be imagined to be, this intersection of perfect duty and distributive justice is where I place the traditional moral concept of "The Golden Rule": if you cannot imagine it seeming acceptable to you for someone else to treat you some way, then you must find it morally unacceptable to treat anyone else that way. Kant's own Categorical Imperative ethical theory could plausibly be described as primarily concerning this category of justice, about what willings could conceivably be universalized.

This is very similar to but subtly distinct from the matter of property rights – of not acting upon something contrary to the will of its owner (including a person's body, which they necessarily own, i.e. necessarily have rights over), which lies in the traditional intersection of perfect duties and procedural justice – because it does not rely on any assignment of ownership, but only on experiential introspection; in much the same way that synthetic a priori knowledge is very similar to but subtly different from analytic a priori knowledge, in that it does not rely on any assignment of meaning to words, but only, again, on experiential introspection.

And of course, just as I hold there to be a category of analytic a posteriori knowledge as well, I also hold there to also be an intersection of procedural justice and imperfect duties as well, which is of utmost importance. For while distributive perfect duties are obligatory (as obligation tracks with perfect duty, and omissibility with imperfect duty), for that same reason of them being internal to the will (hence perfect duties), but not in terms of publicly established relationships of rights (hence distributive), they are not interpersonally relatable, and so are only a matter of private justice, not public society.

The only obligations that can be treated publicly are those phrased in terms of property with assigned ownership, procedural perfect duties; but those in turn depend on the procedural imperfect (and thus omissible) duties of assignment of such ownership. -

The methods of justice: "deontology" as "moral epistemology"On Efficiency

This notion of the value put on the line by different intentions dovetails into another prominent principle of intention-formation, which I consider analogous to the principle of parsimony in epistemology, what we might call the principle of efficiency, or perhaps the principle of economy. This principle simply states, rather uncontroversially, that if given multiple intentions or strategies or abstract models that all satisfy our appetites equally well, the one that requires the least investment of anything of value – whether that be capital, labor, whatever – should be preferred.

Likewise, just as in a previous thread I argued for an application of the principle of parsimony to give a normative grounding to Thomas Kuhn's description of the structure of scientific revolutions, so too I think this principle of efficiency can give a normative grounding to a structure of practical revolutions.

The entire point of coming up with strategies, abstract models to intend, is to have an easier, less costly means of achieving our ends than just attending to every single appetite on an individual basis. So this structure of practical revolutions would proceed from a period analogous to Kuhn's pre-science, wherein no single strategy has yet been devised that can account for all of the appetites at stake, and so there is no better, easier, simpler, more efficient way of satisfying all of them than many different strategies used in a patchwork to account for each of the disjointed areas of concern.

Once a strategy is devised that can account for all of those appetites, that then becomes the better, easier, simpler, more efficient way of achieving it all, and so the patchwork of other strategies are rationally, pragmatically discarded in favor of it. There may still be other strategies that also account for all of those appetites, and so are equally permissible, but unless they are in turn even more efficient, there is no reason to use them instead, and pragmatic reason not to.

But as new appetites are found that cannot be satisfied by the existing paradigmatic strategy, the best way to satisfy all the appetites at stake begins to grow again into an unwieldy patchwork of the main paradigmatic strategy and all of the exceptions and special cases needed to be made and used to handle the anomalous cases, until at some point that patchwork becomes so complex that other competing strategies, previously rejected as less efficient than the paradigmatic one, are now more efficient than the old paradigm plus all of its exceptions, and it becomes rational to adopt the best of them instead of trying to cling to the old paradigm and its mess of special exceptions. -

The methods of justice: "deontology" as "moral epistemology"Against Consequentialism

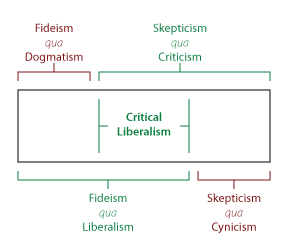

As should be expected from the positions already argued for in my previous thread about commensurablism, my general position on the methods of justice is critical liberalism. That is to say, I hold that rather than by default rejecting all intentions until reasons can be found to justify them, all intentions should be considered justified enough by default to be tentatively held until reasons can be found to reject them.

It is only when one wishes to assert one intention over another that reasons need to be presented to show the other intention to be in some way wrong, and that alone does not in turn show that the proposed alternative is the one unique correct alternative, only that some alternative is needed, with the one put forth being merely one possibility.

In this manner, achieving justice is not, on my account, about starting from a state of everything being prohibited by default and building up to grander and grander systems of obligations for how to live the good life – the totalitarian view that every behavior either must be or must not be, everything either prohibited or obligatory – but rather about starting with limitless freedom to act or not to act, nothing either prohibited or obligatory, and then embarking on a never-ending process of narrowing down the range of permissible actions by eliminating those that can be shown to be bad. This deontological view is more generally known as liberalism or libertarianism, and it has been promoted by many, many philosophers dating back at the very least to John Locke.

Although I do consider ends to be important, and have done an entire previous thread on purpose about that subject, my overall ethical view is technically deontological in the more usual sense, as in opposite the view called consequentialism, which holds that the ends justify the means, because I also consider means to be independently important, and not merely justified by the ends that come about because of them. I consider consequentialism to be the prescriptive analogue of confirmationism, which I have already argued against in my previous thread on epistemology.

Just as confirmationism holds that true implications of a belief can positively justify that belief, so too consequentialism holds that good consequences of an intended action can positively justify that action or intention. And just as I hold that beliefs do not need positive justification, but rather only need to hold up to negative criticism, and in fact can never be positively justified but only tentatively survive such criticism, so too I hold to that principle for intentions as well.

Consequences do matter, but only because bad consequences can show an intended action to be bad, not because they can positively justify it as good. Intentions can only be shown bad, or not yet shown bad; never positively shown good. Because of this, nobody is ever positively obliged to action, though they can be obliged to inaction: if you are doing nothing, then you are doing nothing wrong, even though to do something instead of nothing might still be better than merely not-wrong. In other words, inaction is always permissible, even though actions may still be omissibly good.

But this does not imply that all intentions not yet shown bad are equal. Different intentions, none of them yet shown bad, can still be more or less likely than each other to bring about better consequences. When it comes to practical decision-making, it is often most reasonable to act on the intentions that have such a greater probability of doing more good than bad. But it is not deontologically wrong to intend something that is merely risky but not actually shown bad yet.

(So, for example, it is never morally necessary for someone to be licensed by some authority, or in other words seek out preemptive permission, to do some risky activity, such that they would deserve punishment merely for not asking such permission first, rather than simply for any harm they might end up causing whether or not they asked permission first).

And it is in some ways sometimes better to adopt such risky intentions, because intentions that put more of value into action, while thereby exposing all of that value to greater risk, can also leverage it for greater returns – or conversely put, to never bet anything at all leaves no opportunity to ever win anything either. And it is only by taking such risks, sticking our necks out and risking doing badly, that we can hope to better discover which actions yield better returns than others and so maximize the value that we create, the good that we do.

In general, I hold, we should tentatively adopt more risky intentions whenever we can afford to lose, but when we cannot afford that risk, we should act in accordance with those intentions that have the greatest probability of doing the most good. (For example, someone who can afford to start many small business ventures, most of which will likely fail but some of which may prove wildly successful, should do so, because otherwise such wildly successful new ventures will never come to be, and the whole world will miss out on what they would produce; but someone who cannot afford to fail at even one business venture should probably pour their efforts into working with some other already-proven business.) -

A poll on hedonism as an ethical principleWhat is a social institute? Would that be a school? — Athena

A school is a kind of social institute, but in this case I was referring to a government, though I do draw parallels between education and governance in my overall philosophy.

What I'm struggling to understand here is how you're forming an argument that hedonism is the only alternative to "...because X said so", yet also arguing that alternative philosophies exist which do not amount to "...because X said so". If Kant's framework relies on reason - ie, only act according to that which you could at the same time wish were a universal law (or something like that), then it seems that the only two conclusions you could draw from that are either a) there exists a non-hedonistic means of judging that which is moral that does not amount to "...because X said so", or b) morality captures more than hedonism and no matter how accurate your measurement of it you'd be missing something if you didn't also measure 'reasonableness' (or somesuch). If you agree that Kant's moral philosophy is based on something no-hedonic, yet also non-authoritarian, then your argument about hedonism being required in order to avoid having to resort to "...because X said so" falls apart. — Isaac

Two common critiques of Kantian ethics are, on the one hand, that it does actually appeal to hedonistic criteria even while it claims it doesn't (Mill himself argued that), or, on the other hand, that it amounts to "I think this should be a universal rule, I would agree to be bound by this, therefore this is a universal rule, and everyone is bound to it, because I think they should be". I agree with both of those critiques, and think that Kantian ethics either amount to endorsing something because the agent is imagining it would be more pleasurable / less painful for everyone if that something were a universal law, or else (and possibly even simultaneously) saying that its a universal law "because I said so". Of course Kant himself would argue that it's neither of those things, but just because he says it's not doesn't mean it isn't.

The "reason" aspect of Kant's theory basically amounts to non-hypocrisy, which is more or less the same as my universalism; and non-consequentialism like his is also an indirect consequence of universalism, on my account. None of that runs counter to hedonism, but see below for more on that point.

If that were an issue then temporal nearness or hyperbolic discounting would also 'matter'. Something else other than feeling good or bad would matter - how far removed the feeling is in time. — Isaac

Again, that just means that something else matters. Here it's the number of people who share in the pleasure/displeasure. That's unarguably something else mattering other than just whether people feel good or bad. — Isaac

Questions which cannot be judged on the basis of reducing suffering. Yet they're still moral questions. One of them even contains the term 'permissible' as you've phrased it. The other implies permissible behaviour (who ought to judge and who ought not). If you're denying that these are moral questions, then on what grounds? If not then there are clearly moral questions which cannot be resolved by reference to hedonic values. — Isaac

Once more, now something else matters - justness of personal responsibility. Just good/bad are no longer all that matter, but additionally the rightfulness of the authority of the judge. — Isaac

Temporal nearness, hyperbolic discounting, number of people, and so on, are all aspects of a concern about suffering, about which one could decide one way or another without changing that the concern is still about suffering.

My view isn't just hedonism simpliciter: that's a very broad category of views, there's room for a lot of disagreement within hedonism. Hedonism could be egotistic, but mine isn't. Hedonism could be consequentialistic, but mine isn't. Hedonism could be authoritarian, but mine isn't. All of those would still be hedonism though, as is mine.

My total ethical view is the intersection all of my four core principles as applied to ethics. Phenomenalism is one of those principles, and applied to ethics that's hedonism. Universalism is another one of those principles, which narrows in to only a specific subset of hedonism. Criticism and liberalism are two more principles, which narrow in on an ever more specific subset of hedonism.

Is it? what would be the 'bad' in that approach - It seems again to confuse a discussion forum with your personal blog. The entire point of posting something on a discussion forum is as a topic for discussion (critical, if need be). To say that people who then discuss such an offering are doing so in bad faith is really weird. — Isaac

Critical discussion is not necessarily bad-faith argument, it's just argument simpliciter. What makes your argument style bad faith is that you don't seem to be engaging in a cooperative pursuit of the truth with anyone, since you never even state what your own stance is, much less look into whether or not it might be right. You just look for any way that someone else might be wrong. Looking for ways that a position might be wrong is not in itself bad faith, but if you're just here to tear other people's views down no matter what they are, and (act as though) you don't actually have any views of your own and aren't engaging in the same figuring-out-what-might-be-right mission as others, just a figure-out-how-someone-else-is-wrong mission, then that's not arguing in good faith.

Which I've no doubt already disagreed with, you've already claimed I'm merely misunderstanding you on, and thus you use, as if flawless, as a prop... I'm only trying to see if the argument has more to offer than "these are the things I think". One of the reasons your posts bug me - and you're not the only one - is that this a public forum. Forum being the key word. It's not your personal blog, you can publish that yourself anytime you like, curate responses if you want to, edit, or not, as you see fit. But here is not the place to do that. Here is a forum for public debate, we're here to discuss, not accumulate a database of "stuff people on the internet reckon".

That you think your account of moral semantics "defends a kind of cognitivism and explains what moral sentences categorically mean" is utterly irrelevant here. Great material for your personal website. Publish it, stick it on YouTube, shout about it on your street corner... whatever. But here what matters is what other posters think it defends or explains. It taken as given that you think it does, that's presumably why you posted it. If you publish it here then it becomes the topic for debate, we're not your editors, nor your peer review board. We're not to be dismissed with "thanks for the input but I don't agree so your services are no longer required" — Isaac

As above, why on earth would I do that? The aim is not to reach a resolution on something such that if that's not possible the project might as well be abandoned. What you're doing is the conversational equivalent of ignoring your interlocutors with "yes, that's all very interesting, but stop interrupting...now, as I was saying..." — Isaac

It's really not about convincing me of anything. Again, we're a discussion forum, we're not a policy think tank either, we don't have to come up with the answer any time. It's about having a decent amount of respect for weight of human thought that's previously gone into these issues. — Isaac

Move on to what? You seem to be confusing the forum with a Gallup poll now. "here's my idea", "I agree", "I disagree", "great discussion guys...next". The argument about moral realism probably extends to several hundred thousand pages in philosophical literature...and it's still not resolved. Do you expect Rosalind Hurthouse to object to Robert Louden’s 'application problem' criticism with a paper just entitled "Yes, I get it, you don't agree, move on!" in which she just complains about his constant interjections that non-virtuous agents cannot learn virtue without rules? Of course not. and the debate already spans several thousand words. We've barely exchanged more than couple of hundred on this, yet a handful of posts in you're already wanting to shut down the discussion and move on as if it never happened. You put the ideas out there ostensibly for debate, but you don't seem at all interested in getting into the debate, you just want a quick round of applause so you can move on to post the next in your grand edifice for the same purpose.

We're here to discuss. The issues with your theory (as yet unresolved) are as good a topic as any, there's no good reason at all to 'move on'. Hell, we still haven't 'moved on' from debating Platonic realism and that debate started 2000 years ago. You've fundamentally misunderstood how philosophical discussion works if you think a couple of exchanges is a good reason to ignore the issues and carry on regardless. — Isaac

My issue with the way that you engage, including the way you frame the issue above here, is that you act like the fact that you made an objection and then were not satisfied with my response is a reason why I should shut up. I don't have a problem with you having objections in the first place, or anyone else; I'm happy to consider them and offer responses. But if I think they're bad ones, and I say why, and you think my reasons why are bad in return, and we're go back and forth and then around and around in loops over and over without making any progress toward settling anything, that doesn't mean that I have to completely stop talking about anything else, just because you are still unconvinced. Nor does it oblige me to keep going around and around in circles with you until one or the other of us is convinced.

Picture this as a literal forum, a physical space. Someone starting a discussion thread is like someone standing up on a soapbox to say something, and then others can come listen and respond and so a conversation happens. It's not the obligation of the person who stood up on the box and started that conversation to devote all of their attention to one heckler in the crowd who won't shut up and satisfy them completely before they're allowed to continue with anything else that they've come to say. Okay, heckler, I get that you don't agree with the things I have to say, but you are not the entire forum, and maybe someone else might be interested in hearing me continue despite the fact that you disagree already. If you continue standing there shouting your disagreement with earlier points, then you're just being disruptive.

I'd ask how you'd like it if someone did that to you in your discussions, but you never state your own opinions, so that's not possible. You're just here to heckle everyone else. That's why you're arguing in bad faith.

The way a good-faith argument works is that everyone agrees to disagree unless reasons to change the other person's mind can be presented, and then everyone states their opinions and their reasons for holding it, and their reasons to discard the other's opinions, and after everyone's done sharing what they think and why, if there isn't total agreement then whoever still disagrees can continue disagreeing in peace until someone has something new to say.

It is not the case that anyone must respond to all objections to the satisfaction of the objector or else be compelled to change their mind or at least shut up. -

Should we follow "Miller's Law" on this Forum?When discussing the dog-eat-dog nature of life, only a simpleton would be indiscriminately charitable, or goodwilled. — baker

Yet you complain that I’m too quick to conclude you’re not arguing in good faith... -

The British UnderstatementI’m reminded of a similar way of speaking that’s commonly in computers programming circles, where there’s no such thing as a “difficult” problem, only a “non-trivial” one.

-

A poll on hedonism as an ethical principleDefine "suffering". — baker

A phenomenal experience with negative world-to-mind fit. -

A poll on hedonism as an ethical principleI mean having accepted that, they don't then question god's instructions on the basis of whether they think he's doing a good job or not. — Isaac

My point (on this specific issue) is not "God doesn't exist therefore this other thing must be the source of morality", but rather "it doesn't matter what God does or doesn't say, if he even exists". And I'm far from the first one to argue either for or against this: philosophers as far back as Socrates (who did not deny that gods existed, nor that they at least sometimes commanded good things) have argued for it, and many philosophers from then up to some still living today (like Robert Adams) still argue against it.

While writing the above it also occurred to me that there's a much more secular common kind of anti-hedonism: Kant's ethics make no appeal to divine commands, nor to any experience, but to some kind of abstract reasoning. On which note, see also the aforementioned Plato, who didn't directly appeal to any of the gods he believed in (being the one to record the aforementioned argument from Socrates), though later Christians transmuted his "Form of the Good" into just a synonym for their God.

That's self-contradictory. If they were concerned about justifying means and libertarian concerns about authority, then they would be performatively contradicting a belief that people feeling good rather than bad is probably the only thing that really matters. — Isaac

Not so. Just agreeing that people feeling good rather than bad is all that matters doesn't tell you anything about, for example, whether or not it's okay to cause a little suffering now to spare a lot of suffering later, or whether or not it's okay to cause a lot of suffering for a few people so as to spare the suffering of a disproportionately huge number of people. In either case you'd be trying to do good by hedonistic criteria, but is it wrong to do some bad by hedonistic criteria even to achieve that good? Is it obligatory? Just agreeing on the criteria alone doesn't tell you that.

Nor does it tell you whether or not it's wrong to disregard the claims of some particular authority figure about what causes the most or the least suffering, or whether or not it's wrong to disregard the majority opinion about what causes the most or the least suffering. In either case you'd still be aiming to do good by hedonistic criteria, and avoid the bad by hedonistic criteria that you think the alternatives would allow, but the others think the same about you, and do you get to take that responsibility into your own hands? Do they? Just agreeing on the criteria alone doesn't tell you that.

The only point of agreement at that point is that if somehow everything could magically and reliably be instantly made such that everyone felt good and nobody felt bad, that state of affairs would be good without qualification, necessarily and sufficiently. How it's permissible to actually get to that state, and who's responsible for ensuring that that happens, are additional questions on top of that. And then how it's practically possible, within those constraints, to make progress in that direction, is yet another question.

I know you hate these analogies, but it's exactly like how generally agreeing about empiricism doesn't resolve any disagreement between (hypothetico-deductive) confirmationists and falsificationists. Both of them agree that what is real is what conforms to all possible observations, but they disagree on the methodology by which to apply that criterion. Also, agreeing on empiricism wouldn't answer any question about whether it's (epistemically) wrong to doubt scientific authorities, or to doubt observational "common sense", etc. All of those are additional questions on top of empiricism. And even once those questions are answered, that still doesn't tell us any particulars about what is real; it just gives us a method to figure that out. Actual scientific questions are additional on top of even all that.

Impossible right off the bat, so anything done from here is going to be a pretence — Isaac

It doesn't have to be possible to actually get to that state of mind in order for it to be useful in an argument. We've all had the experience of having things we believed thrown into doubt, usually more than once. We can imagine where that might lead, if that kept happening without end -- to the aforementioned epistemic darkness -- and then think about how we'd go about finding a way out of there, as a means of preemptively keeping from getting anywhere close to there.

The question could be ill-formed, meaningless or nonsensical. — Isaac

Then it's not actually a question, but a sentence in the grammatical form of a question which nevertheless asks nothing. Just like "Colorless green ideas sleep furiously" expresses no proposition, despite being a grammatically correct sentence. There's nothing actually being claimed, and likewise "Do colorless green ideas sleep furiously?" isn't actually asking anything.

I already foresee that you'll reply "What if all moral sentences are categorically like that?", which is just non-cognitivism, and that's why I have an account of moral semantics that defends a kind of cognitivism and explains what moral sentences categorically mean, though of course it's still always possible to construct a specific meaningless one, like "Colorless green ideas ought to sleep furiously".

why would you think we'd follow on through the project as if it hadn't happened? — Isaac

I wouldn't think you would. I would think you would drop out as soon as it became clear that we're not going to reach a resolution on something that will be foundational to everything else to come.

If someone was doing a bunch of discussions expounding on a kind of theist philosophy, I might (but probably wouldn't both to) engage in the first one to point out how whatever that topic is rests on something I think is a faulty premise -- the existence of God -- and when it became clear that they were unconvinced by my arguments against that premise, I wouldn't bother following along to remind them that I disagree with their theism every time they posted.

I'm aware that there have been objections along the way in my series of threads. I think I've adequately addressed them. I'm aware that you don't think that. I don't think it's worth the time trying to convince you about them, because I still don't think you're arguing in good faith. (You only ever adopt a position so as to argue against someone else's and never positively endorse any position yourself, making you always playing offense and everyone else always play defense, which is a classic type of bad-faith argument style).

So I expect that, like a reasonable person, you will abandon the argument against what you perceive as an incorrigible interlocutor. And yet you keep showing up to remind me that you still disagree. Yeah. I know. Move on. I don't care to convince anyone in particular in practice, only to have an argument that is sound so far as I can tell -- even after listening to objections and looking for anything new in them -- and if others are unconvinced by it for what seem to me to be bad reasons, oh well, I didn't convince someone, who cares, move on.

But if he is trying to start with widely shared, uncontroversial premises in building up his argument, he has to contend with the fact that, right out of the door, people's moral intuitions aren't in alignment with his principle. — SophistiCat

The point of that Russell quote on that topic I quoted earlier is pretty much that in doing philosophy, we're always going to start out appealing to some intuitions people have, and showing that other of their intuitions are contrary to the implications of those. If we're doing it well, we'll pick deeper, broader, more fundamental things, the rejection of which would be even more catastrophic, as premises, and show that other less foundational but still common views are incompatible with those, for our conclusions.

People's intuitions of particulars about both reality and morality can be all over the map, and I'm trying to appeal to far broader and deeper things like "there's such a thing as a right answer" and "any answer might be a wrong one" (neither of those only specifically about ethics, just in general) to establish, not even answers about those particulars, but merely a reliable method of finding such answers. -

A poll on hedonism as an ethical principleMaybe this paragraph needs to be in 3 or 4 dot points of itself. — Tom Storm

I can probably just trim out a lot of redundancy and external reference to make it better:

The method by which to decide what is good or bad is for everyone to do whatever they like, unless one of them can show reason why another’s intention would hurt someone. That still doesn’t conclusively settle what is the most good, but it narrows in on it gradually by eliminating the bad. -

A poll on hedonism as an ethical principleI’m not sure what you’re responding to there? I don’t have any disagreements with what you wrote.

Do you think you would be able to summarize your ethical system in 5 or 6 dot points or a syllogism? — Tom Storm

Sure thing.

- The meaning of ethical claims is to impress (get someone to adopt) an intention (which is the same thing that might otherwise be called a “moral belief”).

- The criteria by which to judge whether to adopt an intention (to think something is good or bad) are hedonic experiences: pleasure, pain, enjoyment, suffering, etc. Everyone’s such experiences are relevant to such judgement.

- Will is the process of forming such intentions, and freedom of will is having them be effective in the direction of your behavior, i.e. it’s the power to cause yourself to do what you think you should do.

- The method by which to conduct that will, to form such intentions, to decide what is good or bad, is to initially think whatever you are just inclined to think even if you can’t name a good reason to, and to agree to disagree with anyone who thinks differently (i.e. to live and let live, to respect liberty), until one of you can show reason — grounded in those criteria above — why someone or other’s intention is bad. That still doesn’t conclusively settle what is good, but it narrows in on it gradually.

- The social institutes responsible for resolving conflicts about the above process should be non-authoritarian and non-hierarchical, a global cooperation of independent people working together voluntarily; basically a form of anarchism, or libertarian socialism.

- The way to get people to form such institutions is basically to help them, to help them help themselves, to help them to help others, to help them to help others to help themselves, to help them to help others to help others, etc.

There’s a lot more detail that can go into each of those points, which is why I did (or will soon do) a thread on each one, and I haven’t given here any of my arguments for them, just outlined what they are. -

Guest Speaker: David Pearce - Member Discussion Thread“Ascetic” is a good suggestion. I thought I had considered and rejected it before because it didn’t actually have anything to do with rejecting pleasure technically, just a disciplined life only contrary to the gross common use of “hedonism”, but looking it up again now it does seem like self-denial of pleasure is a part of the definition, so that might work after all.

-

A poll on hedonism as an ethical principleIf we survey current and past moral attitudes, we can find plenty of examples of moral imperatives that are not aimed at the reduction of suffering. I take it that Pfhorrest and a number of others would not support such attitudes. — SophistiCat

:up:

So people disagree about right and wrong. What else is new? What are we discussing here? What's the point of all these threads and polls? To identify like-minded members? — SophistiCat

Well my threads all have different points, as elaborated in response to Isaac two (of my) posts ago. They're just all about parts of the same (my own) philosophical system, so of course they're all compatible with my hedonistic views, but only one of them is actually supposed to be arguing for those views.

This poll is because I was surprised at the apparent total lack of agreement in an earlier discussion, so I thought I would just ask explicitly who does or doesn't agree, to see if maybe there are like-minded people who just aren't commenting because people only comment when they have an objection. -

Transhumanism with Guest Speaker David PearceThank you for your response! If you don't mind, I have a few followup questions for clarification:

An architecture of mind based entirely on information-sensitive gradients of well-being simply isn’t genetically credible — David Pearce

I'm unclear what you mean here by "genetically credible", but my guess would be that you mean we are genetically predisposed to disbelieve in a wholly hedonistic morality (thus explaining why acceptance of it is so atypical, as you say). Is that an accurate guess as to your meaning? If not, can you elaborate what you mean?

And on a related note, I'm wondering if your suggestions to self-label with things like "secular Buddhism” or “suffering-focused ethics” is intended to be a response to this bit of my initial question:

Oh and also: does he know a good term for anti-hedonist views in general? Because I feel like I’m sorely lacking any catch-all term that doesn’t name something more specific than just that. — Pfhorrest

If so, then I think I was unclear. I was wondering if you know a good blanket term for the kind of position that's opposed to views like yours and mine, the kind of position that holds that reducing suffering is either unnecessary or insufficient for morality.

Thanks again! -

A poll on hedonism as an ethical principleWell, since religious people accept their ethics on faith, not rational argument, I can't understand why you would put such effort into it. — Isaac

Because there are supposedly rational people (thousands of years of professional philosophers) who give arguments for why that's supposedly the right way to do things, who get copied by the amateurs who use those arguments as cover for their irrationality. The point is to shoot down that cover, and give ammunition for others to do so, to expose irrationality as irrationality and not let it hide behind a veneer of rationality. If people want to stand by irrationality openly as such, then there's nothing more to do.

You've not quoted a single philosopher who doesn't agree with the basic points you take as premises here. — Isaac

Plato is the first obvious example, and consequentially pretty much all Platonists, Neoplatonists, and so also most Christian philosophers. Plato in general rejects the importance of pretty much anything experiential, whether that be empirical experience to tell us about reality, or hedonic experience to tell us about morality. To Plato, experience is pretty much all deception and vice, and both truth and goodness can only be found introspectively, by contemplating the Forms, all of which are subsumed within the Form of the Good, the highest form (equated by later Christian philosophers with God himself), which is the source of all goodness and all truth.

Lots of supposedly smart, reasonable people believe some really wacky shit.

SEP also has a list of arguments against hedonism with names if you like.

It means having an answer to those questions (otherwise you wouldn't even be starting the process). — Isaac

It really doesn't. I have thoughts on the answers to those other questions, sure, but someone who was philosophically unsure could agree in general that people feeling good rather than bad is probably the only thing that really matters, as an end in itself, but be undecided about whether the ends justify the means, or whether we should trust authority, etc.

The idea that you out of all of them, have come up with a system finally, after 200,000 years of trying which is not just a re-framing, or restatement of the issues already known, is ludicrous to the point of being messianic. — Isaac

I'm very open about how most of the parts of my views are not new things that have never been espoused before. I think my novel contribution to the problem is mostly in taking parts from those different well-known views and connecting them together into a form that escapes their common arguments against each other; basically, agreeing with their best arguments against each other, in every direction, and keeping only what's left of each side. And also, in grounding the resultant structure in the basic pragmatism (itself also not entirely my own invention) I'm about to elaborate on below.

for that to be the case you'd surely be unsurprised by the amount of 'pushback' you get from people struggling to believe this fact, yet it seems to constantly alarm you. — Isaac

What surprises me is not that some people disagree, but that it seems like nobody at all agrees. I expect a certain type of person (like all those descended from Plato above) to disagree out the gate, but I also expect there to be plenty of people who haven't had their minds ruined by bad philosophy to think it's obviously right, and to be interested in a new line of attack against those who think it's wrong. It was the utter lack of the latter (until this poll showed they were just hiding in the woodwork) that shocked me.

You're working with people's intuitions only here. No actual physiological facts. so how are you distinguishing a 'conclusion' from a 'premise'. Our intuitions don't go around with little labels on them. if I have a feeling that everyone should "be less authoritarian and hierarchical and work together independently but cooperatively to realize all of our dreams" and I also have a feeling that "imposing suffering on others is bad", and maybe also a feeling that "some divine being must have made this universe and so whatever He says is right must be right"... What properties of each of those feelings are you using to judge that one is a 'premise' and the others 'conclusions'. Why should one not take one's feeling about God as a premise and one's feeling about suffering as a conclusion - realising that they must be wrong about the whole suffering thing because God can be a bastard sometimes in that respect? — Isaac

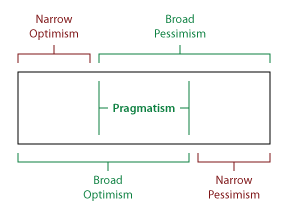

Answering questions like this is the most novel individual point of my entire philosophical system (as opposed to the structural things relating pieces of already well-known positions together). Even this has precursors though, in a lot of pragmatists and proto-pragmatists, going way back to Blaise Pascal.

And that answer is basically to suppose a starting point of absolute radical doubt where you don't even know what there is to know, or how to know it, or if we can know it at all, or if there is even anything at all to be known, and then recognize that in any case you can't help but act on some tacit assumption one way or the other, and ask which of the possible assumptions among those you've got to blindly make in this epistemic darkness are most likely to lead you to figuring out the answers to things, in case it should turn out that there actually are any answers that can be figured out.

The first two such assumptions I argue for from that position are that there is some such answer or other to whatever question is at hand (because if you assumed instead to the contrary, you'd have no reason to try out any potential answers), but that it's always uncertain whether any particular thing is that answer (because if you assumed instead to the contrary, you'd have no reason to check if any other potential answer is better than your present guess).

From there I then rule out other things that run contrary to those pragmatic assumptions, anything that would give reason to give up the investigation in either of those two ways, and run with whatever is left. Elaborating the chain from those core pragmatic assumptions to every other specific position is what all the text I've already written in all those other threads is for, so I'm not going to repeat it all here. But on the topic of this thread about hedonism specifically, I'll give an abbreviated version of that chain:

If you are to remain always uncertain whether any particular thing is the correct answer, you can't just take anyone's word without question; you have to be able to check supposed answers. To check supposed answers, we have two things to test: their own basic internal logical self-consistency, and their accordance with external phenomenal experience. And phenomenal experiences of things seeming good or bad are what is meant by hedonic experiences. So any claim of something being good or bad must be in light of the hedonic experiences associated with it, or else you'd have to just take someone's word on it without question, in which case you'd never find out if you were wrong, which leaves you much more likely to be wrong, which you presumably care to avoid. (And if you don't care to avoid it, okay, go ahead and be probably-wrong.) -

The "subjects of morality": free will as effective moral judgementI have not changed it at all. You just don't understand it. Willfully, I think, since you said you want not to distinguish between the two.

If you put a bunch of simple things together and some higher-level structure or behavior appears out of the complex of them, that's emergence, simpliciter, of some sort or another.

If you could (in principle) model just the simple things, put together like that, and your model would automatically show the higher-level structure or behavior in the complex of them, that's weak emergence.

If, instead, even a perfect model of just the simple things, even put together like that, could not (even in principle) automatically show the higher-level structure or behavior in the complex of them, unless you added a special rule to the model to make complexes like that do things like that, that's strong emergence.

On my account, if you were to perfectly model just the low-level behavior of a bunch of matter arranged exactly like it is in a human being, you would automatically model a being capable of suffering, and all other mental phenomena, without having to add any special rules to the model specifically to handle modeling mental phenomena. So that is weakly emergent, not strongly emergent. -

The "subjects of morality": free will as effective moral judgementThe capacity to suffer arises when matter without capacity to suffer is arranged the right way. Therefore, suffering is strongly emergent as per your definition. — Olivier5

No, because the capacity to suffer is, on my account, a product of the way that the brain functions (though like all mental phenomena it's multiply-realizable: it doesn't have to be exactly a human brain to be capable of suffering, just execute the same general kind of function), which is an ordinary physical process built up out of simpler ordinary physical processes in a way that is only weakly emergent.

I.e. there's not some extra fundamental law of nature about suffering, on top of the ordinary physical laws, that only applies to matter arranged the right way into something like a human brain. But when you arrange matter the right way, a possible product of the complex interactions of the ordinary laws already governing that matter is a state of suffering. -

The "subjects of morality": free will as effective moral judgementRocks should be however minimizes the suffering of things capable of suffering. Rocks can't suffer, so the rocks themselves aren't subjects of concern in ethical considerations.

And yes, the capacity to suffer is a (weakly) emergent phenomenon, like life, consciousness, and back to the subject we're wildly diverging from now, will. It's a kind of functionality, which like all functionality shapes both behavior and experience. -

Should we follow "Miller's Law" on this Forum?Should we follow "Miller's Law" on this Forum? — Don Wade

Yep, though it's more often called the principle of charity in a philosophical context.

Failure to to apply it is pretty rampant here, as with most everywhere. -

The "subjects of morality": free will as effective moral judgementIf your form of reductionism is not like that, if it can find ways to calculate moral values based on the Schrödinger equation — Olivier5

It isn't like that, but not because it can "calculate moral values based on the Schrödinger equation", but because questions about what is real and questions about what is moral are completely separate kinds of questions, on my account. Analyzing what a human being (or anything) is, down into quantum fields or whatever, tells us nothing one way or the other about what ought to be; the answers to the latter question are independent of answers to the former question.

And that's not strongly emergent, because it's not that new "ethical properties" arise when amoral matter is arranged the right way, but that ethical questions are completely separate from what kinds of properties what kinds of things have and how they relate to each other. -

A poll on hedonism as an ethical principleIf one excludes the religious, then I think it is indeed plausible (trivially so) that "all that matters, morally speaking, is people not suffering" — Isaac

Excluding the religious (and similar) views on morality is the point of this facet of my ethics. The people who object to this ethical view pretty much just are religious people. They’re the ones I’m arguing against.

We’ve been over this before. If you trivially agree with my points, great! Others don’t. Let’s talk about why exactly they’re wrong. Not just congratulate each other on being right, but examine just what subtle errors lead (or excuse) others away from being right.

It packs within that all sorts of assumptions about how to deal with uncertainty (do we act immediately on every 'discovery', or are we cautious about new knowledge?), how we deal with trust ('we' never discover anything, some group does - do we trust them?) — Isaac

It explicitly does not, and this is the point you keep missing about all the different threads that are each focused on one narrow part of the big picture. Endorsing hedonistic altruism doesn’t have to mean endorsing consequentialism or authoritarianism or anything like that. It’s just an answer to one little question: what criteria to use when assessing what is moral. The methods by which to apply that are another topic (and on that topic I’m anti-consequentialist), who is responsible for applying such methods is yet another (and on that topic I’m an anarchist), etc. And those are topics I’m getting to.

You always seem so bothered that I’m not addressing ALL of the parts of the WHOLE complex of issues all at once in one thread, but do you have any idea how huge of an OP that would be? I was actually going to have a nicely organized thread with an overview of the whole general structure of my big picture argument back at the start of this, and I though all this time that I had, but I recently realized that the way YOU jumped all over me in the thread that was to precede that one screwed up those plans and I never actually did that correctly. (I made a followup post to that thread recently noting that fact, and elaborating on the stuff that I didn't get to posting back then).

It seems like you want me to start with the big picture conclusion (“hey everyone lets be less authoritarian and hierarchical and work together independently but cooperatively to realize all of our dreams”) and then go into the reasons for that conclusion and the reasons for those reasons etc, going backward through the argument until we get to the deepest premises. I get it, you’re used to psychologically analyzing like that. And that could be a way to do it, sure.

Except then anyone who doesn’t like that conclusion on the face of it is going to dig in their heels and reject any premise that might lead to it no matter how trivially true those premises. So instead I start with the trivially true premises, and build up from them slowly toward the big conclusion, showing along the way why it had to follow from those very agreeable, trivial premises.

Yet when I do that, YOU nevertheless jump as uncharitably as possible straight to what you think my conclusion will be, take reaching that conclusion to be the reason to hold the premises rather than the other way around, and so try to twist those premises, that are MEANT to be trivial uncontroversial starting points, into a hidden form of the conclusion you think I’m going for, and when I clarify that that’s all unwarranted reading-into what I’m actually saying, you call what I’m actually saying “trivial” as though that was a bug rather than a feature.

Bertrand Russell wrote "The point of philosophy is to start with something so simple as not to seem worth stating, and to end with something so paradoxical that no one will believe it."

I started off with things you think are not worth stating. Good! That's where we're supposed to start! The point is to first get agreement with those no-duh obvious things, and then build up to things nobody wants to believe (like the rejection of all religions and states), on the grounds of those very same trivial obvious things.

So to have you constantly complaining either that those things are trivial and obvious (duh) or else a hidden attempt at authoritarianism (quite the opposite)...

ETA: I wanted to give a brief recap of the series of threads you insist are all on the same topic, and your disruptive influence on them.

- First I did a series of threads on meta-philosophical topics.

Those all went pretty fine and as far as I can remember you didn't participate in them.

- Those were to culminate on a thread about taking a systematic and principled approach to philosophy generally, in which I gave, as an example of the kind of thing I meant, my core principles (just stated, not argued for) and a list of some other positions that I think they imply (again, just stated, not argued for; these were only examples of the kind of thing I wanted to get other people's examples of too).

That got completely derailed into a long argument with you about the implications you assumed must follow from one half of one of those four principles (the moral side of the principle I then called objectivism, now universalism), so I made a different thread to continue the topic that that one was supposed to be about, and turned that one instead into...

- A thread about my basic philosophical principles in general and how they relate to each other in a big-picture kind of way.

Because I was already just trying to get out of the fruitless loop of argument with you, I actually never got around to properly presenting arguments for adopting those principles, or relating them to each other in a big-picture way, as I had planned. (I returned to that thread recently to do so, when I realized that). That completely threw off everything else that was to come.

- I was going to do a series of four other threads, each one on one of those four core principles, elaborating on what I do or don't mean by it, and giving more extensive arguments for it.

But I was so fucking burnt out from you in that previous thread that I just skipped those entirely.

- Instead I moved on and started a thread on philosophy of language generally, including but in no way limited to moral language.

You took that opportunity to pick up the same damn argument against moral objectivism/universalism (because, yeah, my general philosophy of language implies that both factual and normative types of claim can be equally true) and turned that entire thread into more of the same shit again.

- Then I did a few threads each about rhetoric and the arts.

- And a few more threads eachabout logic and mathematics.

- I did a thread about the criteria by which to judge what is real, and implications of that on ontology more generally.

- I did a thread about philosophy of mind.

As I recall, you didn't participate in any of those (the last of which really surprises me), and they all went pretty fine.

- I did a few threads about different sub-topics within epistemology, i.e. about the methods by which to apply the aforementioned criteria by which to judge what is real, because every thought I have on epistemology would be way too long for one OP.

And you showed up to the first one to attack things I wasn't even arguing for yet, but I had implied I believed since the next thread was going to be about that, and then complained when I dropped that thread to start the one in which I was actually going to give arguments for the thing you were already attacking, and that turned into another shit show because of you. (Yes, others were also participating, but you were the only one being a pissant there.) You thankfully didn't show up for the remaining few sub-topics of epistemology, or if you did I managed to ignore you.

- Then a thread about philosophy of education, sorta crossed with philosophy of religion.

You didn't show up there as I recall, and it generally went well.

- A thread about my approach to the sub-fields of ethics generally, and how that differs from the usual organization of ethics into different sub-fields.

I think you maybe showed up there briefly but I managed to ignore you.

- A few threads about the criteria by which to judge what is moral, and how that's sort of the moral analogue to ontology, which field I refer to as "teleology".

Despite the fact that this is finally the topic that you kept making so many of the earlier threads about, you didn't show up, thankfully.

- I'm currently doing a thread on free will and moral responsibility.

And I'm surprised you haven't shown up there, but please, don't change that.

- Next up will be a thread (or maybe a series thereof) about the methods by which to apply the aforementioned criteria by which to judge what is moral, and how that's sort of the moral analogue to epistemology, which field I refer to as "deontology".

- Then, almost finally, a thread (or maybe a series thereof) about the social institutions to apply such methods, i.e. about governance.

Those are the topics you claim I'm ignoring the implications on, when I'm explicitly not implying anything about them yet, because I'm planning to talk about them each on their own, soon.

- And lastly will be some meaning of life type of stuff you probably don't give a shit about.

So yeah, I guess I just keep on ranting about the same thing over and over again, eh? Or maybe you're just not paying attention? -

The "subjects of morality": free will as effective moral judgementIf that’s your point, it’s completely beside my point.

Emergence came up in this thread in the course of making the point that the higher and lower level structures are metaphysically continuous, such that the higher level can be broken down to the lower level and the lower level built up into the higher level and at no point do all new metaphysics have to be invoked: it’s all the same kind of stuff, examined at different levels of detail or abstraction. Strong emergentism definitionally runs counter to that. If you’re not counter to that, then I’m not arguing against you. As I’ve been saying all along. -

If all (perception and understanding of) reality is subjective then the burden of proof is not on thTo claim something is to disagree with anything contrary to the claim; conversely to disagree just is to claim to the contrary. It’s the same thing.

And the burden of proof is on whoever is doing that thing, not the person they’re doing it to. IOW you’re free to think whatever you like for no particular reason, until reason to think otherwise is presented; so anyone telling you to think otherwise needs to give reasons for that, reasons beside your own lack of reason to think so. -

The "subjects of morality": free will as effective moral judgementI suspect you use this distinction between strong and weak donkeys to muddy the water and avoid facing the existence of real donkeys. Because you and I happen to agree on the impossibility of transluminous donkeys. Where we disagree is where you say "weak emergence is trivial". I believe it is massively important and non trivial, as it created you and me. — Olivier5

I only mean trivial in the sense that it's not something in dispute. Nobody denies the existence of subluminal donkeys, so there's no point arguing about them. And you and I may exist that there are no superluminal donkeys, but there are other people who claim that they do exist. I suspect that you think it's pointless arguing about whether superluminal donkeys because they obviously don't, but if you agree that that's obvious you're not the target of the argument, the people who think they do exist are. If the only donkey's you're talking about are subluminal ones, I don't know why we're even arguing, and in that sense (the "where's the disagreement?" sense) it's trivial.

However, as the conversation has gone on, it's begun to sound like you really do believe in superluminal donkeys, think all donkeys are superluminal, and take disputing the existence of superluminal donkeys to be equivalent to disputing the existence of donkeys entirely. Or at other times, in the other direction, like you think a "donkey" is just any ungulate. Or possibly both at once, that all ungulates are donkeys and all of them are superluminal, and take my denial of anything superluminal as a denial that even cows exist.

A theory of everything would include some description of life, societies, language, literature, science, philosophy, and the likes, and therefore would need to account for their emergence. The TOE won't be just about muons. — Olivier5

Sure, but the TOE should be able to relate phenomena on any level to phenomena on any other level, in principle, even if it's impractically difficult and not something we'd want to do in the ordinary routine of things. It should be able to describe psychological phenomena in terms of biological phenomena, and biological phenomena in terms of chemical phenomena, and chemical phenomena in terms of physical phenomena. Just like in mathematics, we can in principle describe things as complicated as Special Unity groups (a kind of locally-flat geometric space, obeying certain rules, where every point in that space is a square matrix of complex numbers, also obeying certain rules) entirely in terms of empty sets nested inside of each other.

There's no practical reason why we would want to do that ordinarily, but being able in principle to zoom into the details of someone on one level of abstraction and see a complex arrangements of things on another lower level means we never have any discontinuities in our understanding of things: we can understand how all of these different kinds of objects at different scales relate to each other. Weak emergence is just the converse of that: if you zoom out and ignore the details on the smaller scale you'll begin to see new structures on a larger scale, just as a natural consequence of those smaller-scale things doing what they do. Strong emergence OTOH is the claim that those higher-level structures are not such a natural consequence: that there are special higher-level rules that explicitly cause those higher-level structures to exist, and as a consequence if you zoom in too far ("reductionism") you lose information.

It would perhaps be handle to speak also of "weak reductionism" and "strong reductionism", where weak reductionism is compatible with weak emergentism and vice versa, while strong reductionism is incompatible with strong emergentism and vice versa. Which once again fits the kind of pattern that comes up over and over again in my general philosophy:

etc

Quantum fields have moral values? Since when? — Olivier5

Patterns of information encoded in quantum fields have moral value (singular, i.e. are of moral value) since they developed into forms that differentiate the experiences they are subjected to into types with different directions of fit, thereby becoming susceptible to suffering upon mismatch of those experiences. -

Moral realismIf anything I'm too hesitant to reach that conclusion, and I'm applauding Maw on their decisiveness.

-

A poll on hedonism as an ethical principleI think I already clarified this earlier, but establishing a scale against which to compare the morality of situations where one end of that scale is nobody suffering and the other end is abject misery for everyone doesn't mean that I expect (who?) to make that good end the case or else (who?) is a criminal or something. It's a scale. It's just how we compare things. Suffering bad. More suffering worse. Less suffering better. No suffering best. It's not a complicated thing.

Thanks for the insight, though I don't think I fit cleanly into either of James' categories. I'm rationalistic, empiricist, intellectualistic, both or neither idealistic/materialistic in different senses, optimistic in some ways but pessimistic in others, fiercely anti-religious, free-willist inasmuch as that means anti-fatalistic, monistic in some ways but pluralistic in others, and fiercely anti-dogmatic but equally anti-cynical. (I'm not sure what he means by "sensationalistic" there; the usual sense I'm familiar with seems out of place).

What I probably am above all else is tenacious. My personal motto and the literal foundation of my entire system of philosophy is "it may be hopeless but I'm trying anyway". Which circles back to the first paragraph of this post: it doesn't matter if attaining complete good in the sense I mean it here is not possible, all that matters is that that's the direction to push toward. Further that direction is better, and that we might never get all the way there is entirely beside the point, because some progress is still better than none. -

The "subjects of morality": free will as effective moral judgementYou might as well, because all this talk about weak and strong emergence is cheap. — Olivier5

I'm still talking about weak and strong emergence. Your refusal to acknowledge that we're talking about different things is the root of this entire disagreement. Philosophical progress is made almost entirely by differentiating concepts that would otherwise cause intractable confusion when conflated together.

The main problem I see with reductionism (the actual name for this idea of yours; an idea from the 19th century) is the elusive bottom: there's no reason to assume that there is some rock bottom somewhere on the path to the infinitely small. — Olivier5

Reductionism is much older than the 19th century, and that's not a fault with it; lots of old ideas are still the right ideas. Literally the first ever philosophical theory in recorded history was "maybe everything is made of the same stuff" (water, according to Thales), and that notion that everything is connected in one continuous unified whole has been the driving force behind most of science. It's not about finding a "rock bottom", it's about not having discontinuities in our understanding: having every account or everything transition seamlessly into each other with no sudden new fundamental laws of nature added anywhere, just building up from simpler laws of simpler things, and analyzing those simple laws of simple things down in to even simpler laws of even simpler things. We start in the middle and connect both up and down.

Man, the more I talk about this with you the more I realize my overarching philosophical principles apply to this situation more directly than I thought. Your recourse to strong emergence to avoid the bottomless pit of reductionism is exactly analogous to the transcendental dogmatist who thinks the only alternative to that worldview is cynical relativism (a la "you have to believe in magic or else you believe in nothing"). You're taking a side on a dichotomy that I consider false. I'm not on the opposite side of that dichotomy from you, I reject the dichotomy entirely.

Another problem is that our present understanding of biology contradicts reductionism, in that in a living being, the structure is more important than the elements, and in fact manages its own elements. This is evidence of top-down causation, an anathema for reductionists. — Olivier5

This is still misunderstanding what's even at issue here. What you're talking about is multiple realizability: you can have a high-level structure realized in many different kinds of low-level structures. That doesn't change that all you need to get the high-level structure it to put some such low-level structure or another in place; you don't have to arrange the parts and then wave your magic wand to bring them to life, just arranging any appropriate parts the appropriate way is enough. That different parts can be used to the same effect is beside that point.

Finally, reductionism is tragically penny-wise dollar-stupid. It makes the quest of truth about some sort of sad bean counting. By that I mean that instead of taking the human condition seriously, it makes gestures in the direction of muons and quarks, assuring us that one day, we will know who we are by looking at our smallest pieces... This is alienating, and may explain the tragedies of the 20th century. After all, if human beings are nothing more than clusters of atoms, one might as well kill them en masse.

Reductionism is a death cult. — Olivier5

I've suspected that some kind of attitude like this was behind your recalcitrance. You think that a deeper understanding of something somehow makes it less special, takes away some kind of magic. Never mind that this is completely mixing up is and ought. You can understand that human beings are fundamentally just really complex patterns of excitations in quantum fields, and still also understand that their lives have moral value; because one has nothing to do with the other. -

The "subjects of morality": free will as effective moral judgementThat is I suppose the crux of your argument. Factually speaking, it is NOT TRUE that we can model, derive or compute the laws of genetics from the laws of chemistry. It hasn't been done yet. Likewise, we cannot really derive the laws of chemistry from those of QM. — Olivier5

"We have not done it" is not the same as "it cannot be done".

Of course in that case we're still not certain as empirical facts can be that it can be done, which is why this is a philosophical issue rather than a scientific one. The question at hand is whether (it is reasonable) to expect that it can eventually be done, or instead that it is just in principle not possible.

That's the repeated theme throughout a bunch of my philosophy: "we haven't done it yet, but should we conclude on that basis that it therefore can't, or instead assume that it can and just keep trying to?" My answer is always the latter.

This is actually a much clearer way of formulating my objection to strong emergentism, so this has turned out to be a productive conversation after all; I'll make a note to myself to phrase it this way in the future.

In any case, I would be interested to hear a synopsis of where exactly the difficulties in reducing biology to chemistry or chemistry to physics are, because in the biology I've studied macroscopic organisms were easily reducible to microscopic organisms, and we've gotten really good at modelling the nanoscopic molecular machinery that those microscopic organisms are made of, which seems like that's already a reduction to chemistry. Likewise, in the chemistry I've studied, all the aggregate chemical reactions were explained in terms of molecule-by-molecule interactions, which appealed ultimately to the physics of electron orbitals for how the atoms of those molecules do their things to each other. At no point in my (admittedly non-specialist) education in these fields were any specific problems where something could not be clearly reduced to something simpler ever detailed, so I'd be curious to hear about some.

I don’t see why we can’t say reason depends on non-physical stuff, if only because reason is itself non-physical — Mww

That's begging the question there. -

A poll on hedonism as an ethical principleThanks fdrake for helping clarify baker's motives/perceptions to me. I don't know how to avoid those misperceptions in the future without just refraining from <sarcasm>daring</sarcasm> to have detailed philosophical views at all. Heck, in this thread it's not even an especially detailed one I'm talking about: it's just "all that matters, morally speaking, is people not suffering" (and consequently, which lead to this discussion, "therefore we should update our idea of what's moral when we discover that something causes someone to suffer"). Which seems like a kindergarten-level "insight", not something that should make me look like an "authoritarian know-it-all".

-

A poll on hedonism as an ethical principlewe're already dealing with a notion of truth that is more epistemic and pragmatic, and thus probably agree for practical purposes — fdrake

:up:

But FWIW, I'm not talking about anything like fuzzy logic or such when I talk about "degrees of truth" here. I'm talking about how one can be concerned with the (boolean) truth of a very general proposition, without having to be concerned with (boolean) truths of any of the many more specific cases of that general proposition being true. E.g. even if it matters whether it's true that there's a car heading toward you, it needn't matter whether it's true that car is a Volvo, or that it's a Honda, or... etc. But the truth of the more general proposition still matters.

Circling back around to the start of this discussion about truth, wherein Baker asked why we should update our ethical models in light of new evidence, or (in a different thread) why I care whether it's true that God exists: in the context of talking about such topics, we're already paying attention to those questions, acting like they matter, at least for the purposes of our discussion here. Since I'm already attending to the question, I care to make sure I don't give a false answer to it.

Baker's question seemed to be "why do you care not to give false answers to things?", not "why are you talking about that topic?" There are lots of good practical reasons not to care to pay attention to particular things, but given that you're paying attention to something already, it's kind of shocking to see someone so explicitly act like it doesn't matter whether they're right or wrong about it. -

The "subjects of morality": free will as effective moral judgementWhether natural laws exist or not by themselves is a matter of dispute. But it cannot be disputed that human beings have identified regularities in the working of nature, which they call laws. Some of these laws pertain to how genetics work. Get used to it. — Olivier5

That doesn't answer the question at all.

Of course we've identified laws of genetics. The question is: if we perfectly modeled the molecules that, when put together the right way in real life, obey those laws of genetics, and didn't explicitly program our model with those laws of genetics, just the laws of chemistry (etc), would we just see the complex systems of molecules obeying the laws of genetics in our model automatically, even though we didn't tell the model anything about genetics?

If yes, that's only weak emergence and I've never argued against it.

If no -- if we'd have to program the model with those laws of genetics in addition to the laws of chemistry (etc) in order to see the same behavior in the complex system of molecules that we see in real life -- then that's strong emergence and that's the only thing I'm against.