-

What makes a government “small”?I realized re-reading my passage you quoted there that there is room for misinterpretation of it, so I've slightly edited it (in the post above) to read like so now:

The smallest government possible would be one where anyone was allowed to do anything to anyone or anything, and where nothing, not even mutual agreement, could create obligations that limited that liberty.

I also wanted to add an addendum to this bit from earlier:

A claim to property in anything else besides one's own body is an additional claim beyond that, in need of defense. And exceptions to that may likewise be warranted. — Pfhorrest

John Locke, the infamous big-government advocate, famously advocated exactly such an exception: the Lockean proviso that there be "enough, and as good, left in common for others". -

Why isn't happiness a choice?Do you even want to be happy all the time? — unenlightened

I do. I want to be rationally motivated to do things that will help other people be happy and keep me and them alive to continue being happy, and then so long as I'm doing the best I can toward those goals, be happy with the things that are already good and calmly undeterred by the things that are still going wrong. -

What makes a government “small”?I've been trying not to participate in or encourage the off-topic digression into the merits of small vs big government, but I have a comment that maybe partially ties it back in:

If you start from the premise that small government is generally better, and that means more permissive laws (more liberty and immunity, fewer claims and powers), then it seems like you would demand a justification for every claim or power added.

The obvious first claim we'd want to add is a claim to property in our own bodies, which is to say a claim that we get to decide who is or isn't allowed to do what to our bodies. A claim against battery, basically. That's pretty easily defended. Nobody wants anybody to be able to just attack them.

We also usually want an exception to that claim: we want it to be permissible to act upon someone else's body as necessary to prevent them from acting impermissibly upon other peoples' bodies. Otherwise, the actions required in the defense against battery would be impermissible, so battery, while impermissible in principle, could nevertheless proceed unabated in practice.

A claim to property in anything else besides one's own body is an additional claim beyond that, in need of defense. And exceptions to that may likewise be warranted.

The first power that anybody usually wants to grant is the power to contract: the power to create claims against one another (or grant liberties otherwise prohibited to one another) by mutual agreement. This is an additional thing that needs defending, beyond any kind of property rights.

And there are likewise probably some important exceptions we'd want to make to that power in order for it to be workable in practice, just like the exceptions to the claims we normally make above.

The point I'm making here is that each of these steps toward what "small government" people typically want is actually a step toward bigger government than the presumed default of maximal liberty and immunity. The more exceptions to the power to contract, or the less the power to contract in the first place, the smaller the government. The more exceptions to claims to property, or the fewer the claims to property in the first place, the smaller the government. The smallest government possible would be one where anyone was allowed to do anything to anyone or anything, and where nothing, not even mutual agreement, could create obligations that limited that liberty.

Pretty sure that nobody wants government that small, not even anarchists (who are not anti-government, just anti-state). But if smaller is by default better unless otherwise justified, you need to justify each of those steps -- the claim to property in your own body, to property in anything else, and the power to contract -- and defeat the justifications of any exceptions to them that others might propose. -

Why isn't happiness a choice?I finished adding them at almost the same second you posted your reply. No worries. :-)

-

Why isn't happiness a choice?is it real or just some chemical reaction? — Brett

Chemical reactions are real.

As to whether or not and why not happiness may or may not be a choice, I think it's worth reflecting on the nature of choice in general.

As I see it, and to my understanding psychological and neurological research backs this up, we are not actively intervening in the moment when we make the decisions that we make. Rather, we review the decisions we made in retrospect and construct a narrative about why we did what we did. But I think it's important that that narrative is not only looking backward, but looking forward. It's not just an explanation of what happened in the past, but a script for the future.

I think of it as though we are each a parent to ourselves. Imagine yourself as a ghost following a child around. You can speak into the child's mind, and watch his actions, but you cannot control him directly, physically move his body, or directly alter his mind. All you can do is watch what he does, try to figure out why he's doing what he does, and give him education and positive or negative feedback so that in the future he will maybe do things differently.

That child is you. You can't make yourself do something, but you can try to understand why you do things, teach yourself, and give yourself positive or negative feedback so that in the future you will maybe do things differently.

Now back to the topic: can you make the child happy? Why or why not?

You can't just reach into his brain and force him to be happy, just like you cannot force him to do anything. But you can teach him and give him feedback on his actions that will, hopefully, encourage happiness in him in the future.

Also, if something is chemically wrong with the kid, you can try giving him some medications to fix that.

One big conclusion I've reached this past year of existential dread is that often times, the feeling of things being fine or awful, hopeful or desperate, meaningful or meaningless, etc, come first, and then (like the post-hoc narrative of our actions) we find things to pin those feelings on, rather than external things putting those feelings into us. (Though that often happens too, of course). If your brain is just chemically in an "everything is awful" pattern, you will find things to feel awful about, even if they're things you already knew and didn't feel awful about before. Conversely, if your brain is just chemically in an "everything is great" pattern, you will find things to feel great about, finding joy and beauty even in ordinary little things that you might have otherwise overlooked.

I've have some limited success in trying to focus on those little things I might otherwise have overlooked as a way to jump-start the feel-good pattern in my own brain. Taking walks around my neighborhood at sunset and photographing ordinary little flowers I see in people's yards along the way is one of my go-to cheer-me-ups. -

Why the argument from evil is lame.I assume you're referring to the Problem of Evil here.

That argument purports to show that specifically an all-knowing, all-powerful, all-good God is incompatible with the existence of evil.

Possible ways to avoid it include saying that nothing in reality is actually evil, or that God isn't all-good. Those usually aren't acceptable to most people, but if you're fine with one or both of them, then the Problem of Evil is a non-problem to you. But that doesn't actually contradict it, that just bites the bullet. -

What makes a government “small”?I guess that a government that has limited legislative power, a small government, could have very strict laws on the few subjects they are allowed to regulate. So small government doesn't necessarily mean permissive across the board, but it certainly does for the things they are not allowed to regulate, as no regulation is permissive naturally. — ChatteringMonkey

Yeah, I'm considering limitations on the government part of its laws, so a government that is (by its own laws) limited to only regulating a few things is, by those same laws, necessarily permissive of everything else.

It's probably worth mentioning a bit of technical philosophy here, the Hohfeldian analysis of rights. Hohfeld analyzed "rights" into four kinds, along two axes: an active-passive axis, and a first- or second-order axis. (Neither of these is the same as the positive-negative axis; that's a third thing that Hohfeld's not concerned with, that can be applied to any of these four types of rights).

A first-order active right is a "liberty", which is a permission to do or not-do something.

A first-order passive right is a "claim", which is an obligation on someone else to do or not-do something.

It's worth mentioning again here that these are not the same as positive and negative rights. Usually when people are talking about positive and negative rights, they're talking about positive and negative claims specifically: a positive claim is an obligation on someone else to do something, and a negative claim is obligation on someone else to not do something.

Claims and liberties limit each other though, because obligation and permission are De Morgan duals: an obligation is the lack of permission to not do something, and permission is the lack of an obligation to not do something. So you have liberties to do everything nobody has a claim against, and all of your claims limit others' liberties. (Even, maybe especially, your negative claims: your claim against someone doing something limits their liberty to do that).

A second-order active right is a "power". Second-order means rights regarding rights, so a power is basically the liberty to change who has what rights. Powers are the kinds of rights that governments have, the kind of thing that lets them declare who may or must do or not do such-and-such, who has what permissions and obligations.

A second-order passive right is an "immunity", which is a claim against having one's rights changed. Immunities are the kinds of rights granted by the US Bill of Rights, which do not directly say that anyone is or isn't permitted or obliged to do something, but that the Congress does not have the power to make changes in who is or isn't permitted or obliged to do certain kinds of things. Because like claims and liberties, powers and immunities limit each other: one has powers to do everything that nobody has immunity against, and all of one's immunities limit others' powers.

"More permissive laws" means more liberties, fewer claims. Since permission is the default in absence of any law, more immunities (like ChatteringMonkey is talking about) means less power to change that status quo ante, resulting in fewer claims being granted, and so more liberties remaining.

I suppose after writing all of that out, I realize that my own conception of "smaller government" is "fewer powers" rather than strictly "more liberties", much like ChatteringMonkey here, but for a non-technical poll that doesn't require all this background, I think they're equivalent enough as "More permissive laws". -

Anscombe's "Modern Moral Philosophy"So would you be willing to defend your view here, in a discussion of the article? — Banno

If I can find time to read the article, sure. I was just replying to the snipped you quoted for now. -

Anscombe's "Modern Moral Philosophy"Obligation makes as much sense in absence of a moral lawgiver as alethic necessity makes in absence of a reality-maker: plenty. Obligations are just deontic necessities, and deontic or descriptive claims no more need be made true by someone than alethic or descriptive claims do. Once you understand what a prescriptive claim means, there are some that are just necessarily true in virtue of their logical structure, and those are the obligations. There are still plenty that are only contingently true, made true by phenomenal experiences accessible in common by to people, just like contingent descriptions are made true by empirical observation; and honestly consequentialism appeals much more to those than to any obligations.

-

What makes a government “small”?Ok, but who owns these homes? You can't give homeless people a home that someone has just left for a few months to go on vacation. It's still theirs. — BitconnectCarlos

That statistic is about continuously unoccupied homes, not just people on vacation. And I’m actually not for just redistributing homes like that, but my point is that at this time there not being enough homes to go around isn’t a problem. There are more than enough homes to go around, if only their ownership were somehow distributed differently.

We're getting way ahead of ourselves here: When you say entitled to an equal-ish share are you talking about land appropriation? If I'm imaging this correctly this seems to be saying we're just fleecing millionaires and billionaires. Am I getting you right or no? — BitconnectCarlos

“Fleecing” suggests a that they would be left with nothing. I’m actually not advocating forced redistribution (just talking about the consequences of hypothetical rules), but even if I were, taking a lot from people who have unfathomably more than that still left is not “fleecing”. -

What makes a government “small”?There are more unoccupied houses than homeless people in the US.

Also, if the principle were that everyone were entitled to an equal-ish share of what is available, and too many people stopped producing as a consequence of that, then how much is available to be shared would go down, as would the size of an equal share of that, which would then incentivize people to work more again.

That would also be in line with the Lockean proviso that people are free to appropriate so long as there’s enough and as good left for others. If there’s not enough and as good... -

What makes a government “small”?FWIW, I never meant this to be an argument about the merits of small government, just about what exactly people mean by that, as illustrated by the argument over UBI I related earlier.

I myself am a philosophical anarchist in principle, but in practice where we live in a world that has states anyway, a lot of self-identified “small government” people chide me for “supporting big government” because I don’t like the de facto power caused by wealth differences any more than I like de jure state power, and if we have to have either I’d prefer they keep each other in check. -

Mathematicist GenesisI had initially intended this to take the first of those two routes, but I feel like I would learn more from the second one, since I know less about it already than the first. So I’m leaning toward the second. But is there not a way to incorporate both at each step? E.g. the naturals are not closed under subtraction so we need some larger set that is (second approach), and the objects of that larger set are the integers which can be built out of naturals like so (first approach).

-

What makes a government “small”?I notice that “simpler/fewer laws” is leading in the poll, and I want to ask the people who picked that a question to make sure they understand it right: would you say that a government with a single rule, “obey all commands from the monarch”, is a “small” government? Because that’s very few and very simple laws; it’s just not a very permissive law.

-

Mathematicist GenesisHurray, we're finally up to where I began, and the first step past it that I said I wasn't able to do myself!

Is it possible to write "1 + 1 = 2" entirely in terms of sets and set operations? Like, if I understand correctly, we can say that 0 = ∅ = {}, and that 1 = {∅} = {{}}, no? So 2 = {{},{{}}}, right?

So {{}} + {{}} = {{},{{}}}

But is there a way to write that "+" in terms of things like ∪, entirely set-theoretic operations? -

The Codex QuaerentisIf I were to ask you to defend libertarian socialism... — BitconnectCarlos

I'm kind of going off-topic in my own thread / getting ahead of the game here, but for some reason this question just popped back into my head again and I wanted to give kind of a response to it.

The way I get to libertarian socialism from a pragmatic grounding isn't by starting with the question "is this the best political system?" but with much more general questions like "What do we mean by 'better'? And what is a political system supposed to do?" and tackle those in a pragmatic way. As we'll see in more detail in the later essays on these topics, I first address what prescriptive questions are practically asking for, then later what criteria are practicable ones by which to judge the answers to those questions, then what is a practical way of applying those criteria, and (glossing over all of that that will be covered later) end up with a liberal hedonistic altruism as the most pragmatic way of figuring out answers to prescriptive questions; of figuring out what to do. A political system is supposed to tell who has prescriptive authority, and from the "liberal" part of the aforementioned system it follows that nobody has prescriptive authority: in other words, philosophical anarchism.

But even the briefest reflection on the practical implementation of anarchism shows that to keep people from exercising prescriptive authority they don't rightfully have requires a general degree of equality, which is where the socialist aspect comes from. How exactly to keep people generally equal, so they can be free of each other's unwarranted prescriptive authority, without in the process exercising such authority oneself, is a question that leaves the domain of philosophy and enters the domain of a more applied ethical science (as I'll call them later), like political science, where case studies etc are applicable. The goal of libertarian socialism is a philosophical result, reached a priori with only regard for the practical ends that are in mind -- what are we trying to do, and what is a logically entailed sub-goal required to do that -- but how to get libertarian socialism is a scientific question, to be answered a posteriori. -

What makes a government “small”?It sounds like you mean "more permissive laws" then. (That's my answer too, but I don't like to vote in my own polls until there are enough votes that I'm not biasing future votes by my first vote).

-

The Codex QuaerentisNot sure if you're addressing me or BitconnectCarlos, but both of us mean it in that sense (CS Peirce is up there above James and Dewey among founders of Pragmatism, and we were both quoting him at each other), but we disagree about what the qualifications are to be counted as part of that movement.

-

The Codex QuaerentisBut I think on further consideration W realised that there are questions that can only be answered with one's life. "Do you take this woman to be your lawful wedded wife?" It is not "I do" that answers, but the actual doing. — unenlightened

Good point. My passage you quoted does have the "of reality and morality" clause, limiting the scope of my claim to just those two types of speech-act, which I elaborate upon later in my essay On Meaning and Language, which also briefly touches on the existence of those kinda of bidirectional speech-acts.

Wow! You have a book!! I have doodles on scraps of paper. :sad: — TheMadFool

This book started as doodles like this (later redrawn on computer obviously) in my notebook during my first philosophy class. (I'm glad I titled that file "nonsense", because even I can't make any sense of it now, 16 years later.) Maybe some day you will have a book too. -

The Road to 2020 - American ElectionsSo I keep hearing how Bernie has now pulled ahead of Biden, but FiveThirtyEight still shows Biden in the lead. I don't know enough about electoral predictions to know why those two things don't line up. Can anyone explain?

-

The Codex QuaerentisSo, that might apply to ethical or moral questions, where different answers might be given in different cultural contexts. Or if such questions are merely matters of opinion, then a question that calls for an overarching answer would not be appropriate. — Janus

My position that unenlightened quoted is specifically taking a stance against that kind of thing (cultural relativism, everything being just matters of opinion), but it occurs to me that Wittgenstein's quote isn't. I am saying "P therefore Q" and he's saying "if not Q then not P", which both have in common "if P then Q" but I'm explicitly affirming P (there are meaningful questions, which therefore have answers) while from what I understand of Wittgenstein he's more likely, regarding moral questions at least, to deny Q, to say that there are no answers and therefore the question is meaningless. -

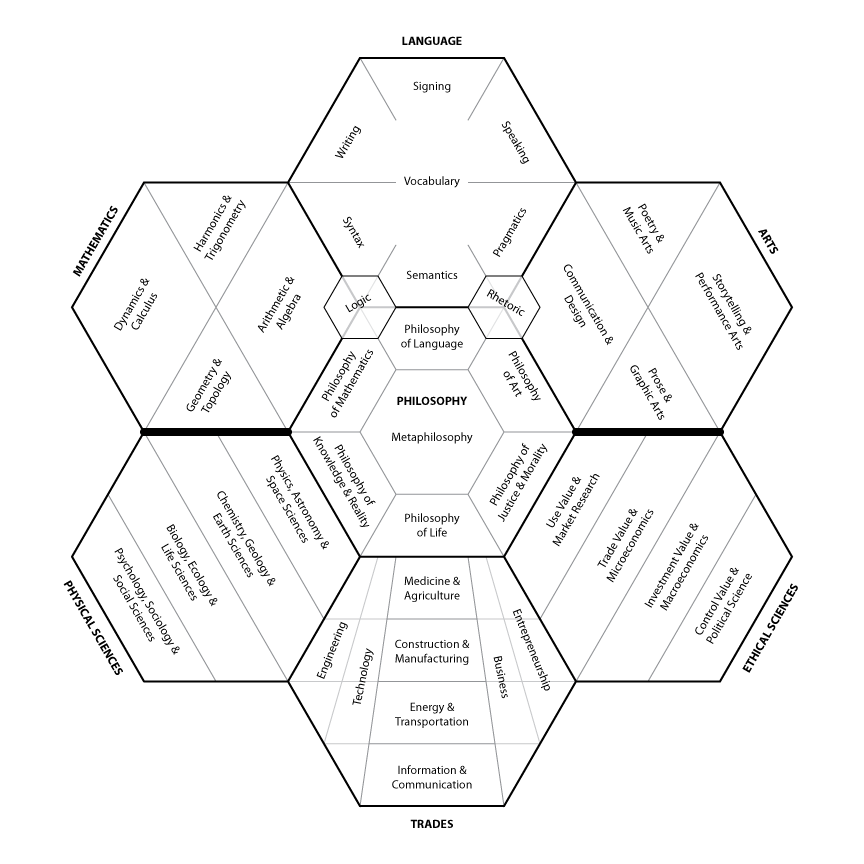

What makes the arts and the humanities of any importance?I think "the arts and humanities" is a poorly constructed category of just "all the stuff that isn't STEM".

I prefer to break down the fields like this:

On which account "the arts" are obviously their own thing, and "the humanities" are they're usually reckoned are spread across something like three and a quarter other categories: language and philosophy are each their own things on part with the arts, mathematics, or the physical sciences, plus there's a whole underdeveloped field of what I'd call "ethical sciences" with seeds in economics and political science, and then psychology and sociology I'd reckon as properly part of the physical sciences stack, but are usually reckoned as "humanities". -

Why should one ask the questions that can never be answered?I personally don't ask questions that I think cannot be answered, and advise others not to either.

The questions I do ask, I think have answers, otherwise I wouldn't ask them.

Also, @unenlightened just shared a great quote in another thread of mine that seems relevant here:

For an answer which cannot be expressed the question too cannot be expressed.

The riddle does not exist.

If a question can be put at all, then it can also be answered. — Ludwig Wittgenstein, Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus

I would say that "unanswerable questions", or the incoherent attempt to pose questions to which answers cannot be found, is more the domain of religion (along with positing answers that, they say, cannot be questioned), which I consider half of the exact opposite of philosophy, which I call phobosophy. (The other half is nihilism). -

The Codex QuaerentisI take it that's offering a Wittgenstein quote that you think encapsulates the same thing that I'm saying? If so, thanks! I'll try to integrate that somewhere soon, though I think it may be more appropriate for the essay on Commensurablism (where I lay out that general philosophy in more detail) than for the introduction.

It sounds to me that saying a question can be answered is saying that there is a true answer to it. That answer may be broad and admit of multiple specific implementations, but if it can be truly answered that suggest that at least there cannot be contrary answers, i.e. mere differences of opinions. -

Are living philosophers, students, and enthusiasts generally more left-wing or right-wing?there's no law or clause in the constitution which demands a two party system. — Artemis

America is actually weird in that we constitutionally have no concept of parties at all. The emergence of a "two-party system" is an inevitable consequence of our FPTP electoral system, but the actual letter of the law has no acknowledgement of political parties at all.

That's partly why our checks and balances have broken down. The Constitution pits the individuals in Congress against the President (and the Supreme Court pitted themselves against both), but nobody expected that a single group would coordinate the capture of multiple branches and make them act in concert, so there's no concept of pitting such groups against each other for checks and balances of political parties. -

Why a Wealth Tax is a stupid idea ...and populismIf you have wealth, cash, moolah, you can buy products and services — ssu

You said "only" before. I'm denying that "only". Here you don't say "only", so that's a completely different statement I'm not objecting to. Wealth effects other things besides that, not only that.

I already explained this but let me try to be more clear about it. If someone has much more of something than they need and someone else has much less of it than they need (both "needs" as determined by each person's own assessment of themselves), the normal expectation would be the poor person would work for the rich person in exchange for some of whatever that is (or work for someone else for money to trade for it, same thing in principle, money is just a medium facilitating multi-party trades), until the poor person has as much as they need or the rich person doesn't have more than they need anymore. But if rent is an option, instead of that exchange of labor for property, the rich person can only offer a temporary use of the property in exchange, so after the whole transaction is over, the original property has been returned to the rich person, and the payment for its use remains with the rich person, so the rich person now has more than they started out with, and the poor person has less. You might say why doesn't the poor person go to someone else who will sell to him instead, but it's in every rich person's interest to have this kind of "I win at your expense" arrangement, so as classes, the rich, who are the ones with the power to dictate what arrangements are available, will prefer those that leave the poor paying them continuously for the temporary use of things, rather than the poor eventually getting richer and no longer having to work for the rich just to get the money they need to pay the rich.If then trade is so good and renting so bad, what is so wrong with renting something than buying? — ssu

If I travel to a foreign country where I would want to explore the surroundings with a bicycle, why would I have to buy a bicycle and then sell it a week later? I theoretically could do that, but renting a bicycle would less difficult. — ssu

Why would it have to be less difficult? Rentals are already more complex arrangements than sales, and sales can be made more complex to simulate rentals if that's what people actually want. The same business that rents you a bicycle (gives you a bicycle to use for so long as you continue making periodic payments for the continued use of it, and you have to keep paying those payments until you return it) could instead just as easily sell and buy used bicycles on installment (so they give you a bicycle and so long as you continue to make periodic payments until it's paid off you can keep using it, or if you don't want to keep using it you can bring it back and they'll rebuy it, for a lower price of course, much of which will simply go to cancelling out your remaining debt for the purchase). The difference is that if you do want to keep the bicycle indefinitely, you can just finish paying it off, and not end up owing for its use indefinitely. And if you don't like the difference between that business's sale and repurchase prices, you're free to sacrifice the convenience they offer to find a better buyer elsewhere, so market forces (great thing eh?) will force the difference between sale and repurchase price to be worth the convenience.

And this is a problem quite generally in every poor country. — ssu

I'm not in a poor country. I'm in the richest state in the richest country in the world (by GDP). It's the people in the piss-poor states who can easily buy huge tracts of land that nobody else wants, who generally think it's everyone else's fault for "choosing" to have been born in the places where most people are born because those are the places most people live.

And who or what is responsible for those financial markets working or not working? It's in the interest of the wealthy for them to "not work" like that (which is working according to plan from their perspective), and the wealthy are the ones with the wealth being lent out, who can dictate the terms on which it is lent. Why would they want anyone to be able to own outright and stop paying them rent or interest? Who is going to stop them? And most to the point, wouldn't stopping them be -- gasp -- socialist interference in the "free" market"?It is a genuine cause for povetry, for a country to lag behind, for there not to exist a large wealthy middle class. The fact is that then the financial sector simply doesn't work. If an ordinary person working in an ordinary job cannot go to the bank, cannot get a loan and cannot pay that loan back and still live decently, the financial markets in the economy simply don't work! If ONLY the rich can get loans with a decent interest, then simply the market doesn't work. — ssu

To be clear, I am proposing "stopping them", but by removing the state protection of the arrangements that allow them to do this (invalidating contracts of rent and interest eventually, but working up to that by increasingly taxing rent and interest income including a negative tax on rent and interest expenses), rather than by adding state enforcement of prohibitions against it (such as by legally mandating interest rates be kept below a certain percent). My way seems more libertarian, more free-market.

(Also, mandating interest rates be limited doesn't necessarily help, if the price of the properties being lent out can just skyrocket so even a small interest rate on a ridiculously overpriced property is still prohibitively expensive).

(On a parallel note, a part of me wonders if the state government of California likes policies that lead to skyrocketing property values, not only because the rich who own that property therefore profit, but because the people directly voted in a constitutional amendment limiting property tax rates, so the only way the government can get more tax is if the properties are worth more).

Simply put, when there is no option other than to rent for people who work, then the entire society has a huge problem. — ssu

At least we can agree on that. -

Are living philosophers, students, and enthusiasts generally more left-wing or right-wing?You explained your curiosity by pointing to other online commmunities and something about rigor. What's the connection? — frank

The specific thing I had in mind there was something I've seen repeated in trans communities (I'm nonbinary myself), where someone philosophically-minded objects to the social constructivism underlying the usual framing of trans identities on general philosophical principles, not in an attempt to attack trans people, and gets framed as being "conservative" (i.e. right-wing) because of that.

Another thing that I've seen a lot of recently is complaints that philosophy is all about old white men and not inclusive enough and so leans toward the right on account of that.

The actual thing that prompted me to start this thread was noticing a lot of people who seem very economically right-leaning on this forum, not to mention the frequent religious posters who I would at first guess think to be right-leaning too because of the association of the right and religion. (Although I have also been surprised in recent years to see people on the left associating atheism with the right wing, which seems really weird to me).

All of that together prompted me to wonder how people generally see philosophers/students/enthusiasts, and how they see themselves.

Moderation for the sake of moderation seems nonsensical. — Artemis

Even Aristotle himself made sure to point out that by advocating for the Golden Mean, he didn't mean the arithmetic mean, the exact halfway point between extremes; he just meant whatever point in between the extreme of excess and the extreme of deficiency is neither too much nor too little of whatever's in question.

I also consider myself a moderate centrist in the way I would frame the political spectrum, but I recognize that that is far to the left of most mainstream positions and so in a colloquial sense (I didn't mean this to be a thread about the nuances of political spectra, just in reference to the mainstream political conflict) I'm "radical left". To me, that just means mainstream politics has almost always been to the right of true centrism. -

The Steeds That Draw My Chariot.most said to me there is nothing beyond the universe. But when they are pressed further about what 'nothing is' they are always unable to answer. — Michael Lee

There is a difference between "the thing that is beyond the universe is called 'nothing'" (what you hear) and "there is not any thing beyond the universe" (what they say). The latter can be rephrased equivalently as "everything is in the universe". The former cannot be coherently phrased at all, because it's nonsense. -

Are living philosophers, students, and enthusiasts generally more left-wing or right-wing?It sounds like you have a strange perception of what "left" and "right" are. For one, it seems focused entirely on economics, ignoring social liberalism vs conservativism which is where I expected religious morality would have the biggest focus (religious moral codes being ancient and so typically conservative by modern standards). But even within the economic dimension, which is indeed a factor, it sounds like by "left" you're picturing maybe Democrats? They're only left in comparison to Republicans, and by international standards (and the standards of most self-avowed leftist people in America) are considered center-right. America has no mainstream left-wing party, and the left-wing people are avidly anti-corporate and terribly disappointed in the Democrats.

Also, it's not so clear-cut that corporations are considered evil by religious people. Consider for example prosperity theology.

everyone is a philosopher for all that's required to be one is an armchair and an average brain which is everyone, right? — TheMadFool

Everyone has the tools to be a philosopher, but not everybody uses those tools for that purpose.

Anyway, I guess it's insufficiently clear from context that by "philosopher" in the question, juxtaposed with "philosophy student" and "philosophy enthusiast", I mean someone who does philosophy professionally, publishing work that is read and commented on by other people widely reckoned as philosophers. -

Are living philosophers, students, and enthusiasts generally more left-wing or right-wing?That's because religious morality is inherently a right-wing thing. Of course right-wing religious moralists think the existence of liberal left-wing morals is a sign of decadence and depravity.

Much like how a "no-party state", made out to be such a high noble thing above partisanship, is actually just a state where nobody is allowed to disagree with the single de facto party. -

On SuicideYou need to work on some reading comprehension if you think what Wallows is on about isn't perfectly clear. You think it's not clear because the specifics aren't mentioned, but that's because it's not about specifics but about a general pattern. It doesn't matter what "A" or "B" are, they're unspecified "confounding factors" of "C" (suicide) the details of which aren't important for his point; he's just asking why we don't address the things (whatever they are) that lead people to suicide, instead of waiting until people are suicidal to do anything. He doesn't mention the specifics, and yeah I don't know what specifics he has in mind, but those are irrelevant to the point.

-

Are living philosophers, students, and enthusiasts generally more left-wing or right-wing?In honor of Banno I have to ask who cares? — frank

Do you have some problem with idle curiosity?

Hey Forrest, I couldn't participate because I'm a moderate independent. (We need more moderates in our political and religious institutions.) — 3017amen

You can still share your opinions on the other questions, even if you don't want to answer the last one.

on this forum they are typically more left wing. — christian2017

So far the results suggest otherwise. (EDIT: At the time I posted this, the results were predominantly left-wing for all questions but the last, which was predominantly right-wing).

socialist countries are considered right-wing according to the standard nomenclature of America, of which this is a website. So despite the most populous country, China, is extreme left-wing, in America the Chinese society is right wing. — god must be atheist

This seems completely backwards. China and all countries called "socialist" or "communist" in America are typically considered left-wing by mainstream Americans, but are officially state-capitalist by their own admission (capitalism generally being right-wing), with communism only a nominal future goal. Historically authoritarianism is also a right-wing position; there's a reason "liberal" and "left" have long been synonyms (though no longer everywhere). -

Are living philosophers, students, and enthusiasts generally more left-wing or right-wing?Also curious to hear people's explanations of what gives rise to those perceptions. Me for instance, I generally expect most educated, academic people to be left-wing, so philosophers and philosophy students would be no exception, but I've also seen online several run-ins between left-wing communities (especially trans communities) and philosophically inclined people, where it seems like lines are being drawn between "philosophically rigorous" and "socially inclusive" as though those are dichotomous categories. So I really just don't know anymore.

-

On SuicideYou're not worth responding to, especially on a day like today, but I understood the general gist of what Wallows was on about (why aren't we doing more to address the societal ills, which are many and varied, that lead people into suicidal conditions) and my response was that society itself is sick, and the symptoms of that sickness prevent it from adequately curing its own sickness. Just like one person's depression makes it harder for them to do things to dig themselves out of the circumstances that lead them to depression, so too society's many and various problems lead people to be dysfunctional in ways that prevent us collectively from addressing those very problems leading to that dysfunction.

And I certainly don't think myself some kind of special hero who's going to fix everything. I did say I'm "barely" functional enough to do "what little I can". I'm acknowledging that most people are too beat down by life to do anything more than feebly try to solve their own problems. I'm pretty much in that category myself, but I've apparently got my head a little more above water than a lot of others. -

Why a Wealth Tax is a stupid idea ...and populismThat there wouldn't be a price for the use of land or built structures sounds very strange, if you otherwise do favor the price mechanism of markets to barter or central planning. — ssu

The price is the purchase price. "To have a right to use something" and "to own something" should be the same thing. The point is for the users of things to be the owners of those things, instead of some people using things owned by others and others owning the things that everyone else uses.

Wealth only effects one's potential to buy products and services — ssu

In a truly free market, without rent and interest, yeah. The exact problem is that that's not true: that wealth can just "generate" more wealth not by being spent but just by being lent. You said earlier:

But that's not how actual wealth is created, that's just how wealth enables one to extract more wealth from the productive economy. If you'd actually read Wealth of Nations you'd understand that the reason why economies aren't zero-sum is because it's not simply the quantity of stuff in the economy but the distribution of it that constitutes the wealth in the economy: if I have a gazillion pencils and no paper, and you have tons of paper but no pencils, we can make the very same stuff worth more by trading some pencils for some paper so that we each now have the ability to write whereas before neither of us did. Trade is what actually creates new wealth; lending just siphons off of that.it is these rents and interests, should we say return on investment, that makes assets grow — ssu

And those with skills that are in higher demand usually get wealthier than others — ssu

All else being equal, yes. The problem is that all else is not equal, and you can get (and stay) wealthier just by starting out wealthier, despite being less productive a worker than people who started out poorer and, despite their greater productivity, remain poorer.

In a modern economy agricultural production is a small cog in the wheel where the service sector is in an important role. So owning land isn't the only thing that rich people can do. — ssu

True, but the underlying mechanism of lending productive capital is unchanged. This is actually an analogy I make a lot: rent and interest are the remnants of feudalism, adapted to a modern economy. In a feudalistic, agrarian economy, serfs lived and worked on land that belonged to someone else, and had to give much of the product of their labor to that landlord for the privilege of living and working there. In a modern economy, there are more types of capital besides land, and we usually work upon one lord's capital while living on another's, but still a big chunk of the product of our labor goes to the first "lord" (the employer) and then a huge chunk of what we "get to keep" goes straight to paying another (the literal landlord, or else the bank).

Paying rent isn't the problem. — ssu

Yes, it is. And banks don't solve the problem, because interest is rent on money and has all the same problems. Borrowing money isn't any better than borrowing housing.

Here if you rent a large two room or a normal three room apartment, you could with the same money buy a smaller flat of your own and pay similar amount some years and then have the flat for yourself. — ssu

Maybe that's true in places where land is dirt cheap and three-room apartments are "normal". When you live in the middle of nowhere and supply is virtually infinite relative to demand, these problems are easily overlooked. But in places where people actually live, where there is a crunch, all these flaws show through.

My parents have spent their entire lives paying for housing and still own no housing to show for it, despite having paid over that time more than the current cost of a house. I have spent my entire life paying the lowest rent I can possibly find (in the area where I was born and raised and where my entire life is so don't just say "why did you move somewhere expensive" or "why don't you just move back somewhere cheap"), saving and investing at ridiculous rates (currently up to over a third of my take-home income) trying to save up enough money for a down payment on anything available for purchase such that the interest alone (which is, again, rent on money) wouldn't exceed my existing rent, so that I can actually finish paying off a house before I die and not spend my entire life having to pay just for the privilege of having somewhere to sit and stave to death in peace.

I have never wanted to rent. I have always wanted to own. I have always lived in the place I want to continue living. But owning within my lifetime has always been out of reach. Even now that I make more than 75% of people in the country do. I don't even live in a big city, I live in a trailer park surrounded by farms and ranches out on the edge of civilization (within walking distance of national forest), and I would settle for anywhere within commuting distance of here, but there isn't anything affordable for hundreds of miles. I have to save up hundreds of thousands of dollars of down payment just so that interest alone on the cheapest available home doesn't make owning more expensive than renting. And the vast majority of people are poorer than me, and live in places more densely populated than my hometown, so this isn't just a "me" thing, this is a huge systemic problem affecting billions of people.

Owning is more expensive than...? — ssu

Than it otherwise would be. If you own two houses, you can live in one and rent the other out for free money. That makes owning houses attractive to people who otherwise wouldn't be interested in owning more houses, people who already have a house of their own, people who generally have a lot more money than people who don't yet have a house and need one to live in. So with more rich people interested in buying additional houses as "investments" (free money machines, not actual investments), the price of those houses goes up way above what it would be if the only people buying were people who need a first home to live in.

And so the people who would be the buyers otherwise, the people who need a first home to live in, are priced out of that, and forced to rent a tiny studio apartment or a bedroom in someone else's house, or if they're rich like me, a plot of land on which to park an oversized vehicle vaguely resembling a reasonable one-bedroom apartment. (One still two small for two people to live in, leaving me approaching 40 years of age and 10 years of a serious relationship and still unable to get married because we can't afford a place we could live in together).

Who's incentive is to build houses if there isn't any price? — ssu

PEOPLE. BUY. HOUSES. TO. LIVE. IN.

I don't want to continue this conversation. Ideological capitalists like you simply can't conceive of any heterodox economic model, and just writing this reply has sucked up my entire day so far. I've had this conversation a million times, and the only people who ever get it are the people who already got it, so I don't want to have it again. -

It's time we clarify about what infinity is.There are more reals than naturals though, so which kind of number do you mean?

-

On Suicide

Thank you :)Then you are an honorable person. — Wallows

I'm not sure. I guess a search for meaning? I want to understand what's important about everything, how it all fits together and relates, and I also want to be important to the world, to create and do good things and to matter to others.I've seen the work that you did on your webpage, and ask you very humbly what makes you tick? — Wallows

Pfhorrest

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum