-

What’s your philosophy?The Importance of Justice

Why does is matter what is moral or not, good or bad, in the first place? — Pfhorrest

All actions are driven by a combination of belief and intention, so no matter what you’re trying to do, half the battle of doing it successfully is having the correct intentions to drive your actions. -

An interesting objection to antinatalism I heard: The myth of inactionI agree with you but I am not exactly discussing the morality of the situation right now. I am asking whether or not you not saving someone is a cause for their drowning. I think the answer is yes — khaled

This is why I brought up the "vanished from existence" factor in an earlier post in this thread. If the Drowning Man still would have drowned even if the Abandoning Man had vanished from existence before getting the opportunity to abandon him, then "abandonment" is not an action.

(I can think of counter-examples to this as a general principle -- such as, for instance, if Alice shot Bob and that prevented Chris from being able to shoot Bob, but had Alice vanished from existence prior to being able to shoot Bob, Bob still would have been shot, just by Chris instead, then that doesn't let Alice off the hook for actually shooting Bob in the non-counterfactual scenario -- but I don't have time to sort that out into a properly nuanced general principle right now.) -

Are we hardwired in our philosophy?Sceptical of what? — Brett

Everything. Infinite regress arguments I learned about in philosophy classes seemed to have gone completely unanswered. Here were these arguments showing that we had no good reason to think that anything was real or moral, and attempts at defeating them, and the faults of those attempts... leaving us with the still-undefeated skeptical arguments. I was freaking out, asking fellow students and professors how the hell they can just continue living normally in the face of this, and the best anyone could give me was basically a shrug and a comment like "you just can't live like nothing is real or moral, so I just ignore it and carry on as though things are". I really really didn't want to accept them, so I continued acting as though I thought things were real and moral, but for a few years at least just sort of felt like those were my baseless opinions and nobody could ever have any claim to tell anyone else that anything was actually real or moral, just their own baseless opinions about that all. -

Are we hardwired in our philosophy?I was raised in a religious family (evangelical, even), identified as a communist in my early adolescence, then as a libertarian by the time I reached adulthood, and was severely skeptical almost to the point of nihilism by the time I finished college (and have now swung back to somewhere in the middle of that range), so at least some people's views can vary wildly over the course of their lives.

On the other hand, my core values were really the same all along, and it was just what I thought was the best way of achieving those values that changed over time. But then those values were things like truth, knowledge, goodness, justice, etc, which I think are pretty universally valued; it's just what people think is the best way of achieving them that varies. -

An interesting objection to antinatalism I heard: The myth of inactionI know his names been brought up but I can't remember in what context; Manson sending the girls out to specifically murder someone. — Brett

That's not inaction, that's indirect action. If the people wouldn't have been murdered had Manson spontaneously vanished from existence before issuing his orders to murder them, then he's indirectly responsible for their murder. In contrast, had the guy who could have saved the drowning guy spontaneously vanished from existence before going for the walk on which he had an opportunity to save him, the guy still would have drowned. -

An interesting objection to antinatalism I heard: The myth of inactionYou might have any number of reasons not to save the drowning man. They might not be great reasons, but they are your reasons and your choice and you’re not killing him just because you didn’t save him. Obviously it is morally preferable that he be saved, but you are not morally liable for that not happening.

Down the contrary road, everyone who hasn’t already given all of their possessions to the most effective charities and dedicated their entire lives to helping those most in need in the most efficient manner possible is morally liable for all of the harm that’s happening that could have been prevented it they did that. -

An interesting objection to antinatalism I heard: The myth of inactionYeah I’m strongly opposed to that whole no-such-thing-as-inaction deal on principle. If you’re doing nothing, then you’re doing nothing wrong. You’re also not doing anything good, but it’s not wrong to fail to do good. To say otherwise is consequentialism gone haywire.

-

Is homosexuality an inevitability of evolution?Sounds plausible to me and is a thought I’ve had before too. But then I’m pansexual so only being attracted to one sex has always seemed a little “unnatural” / culturally conditioned to me.

-

We are not fit to live under or run governments as we do in the modern world.There are a lot of different proposals for how an anarchic society could be structured. You can read my ideas on that in my essay On Politics, Governance, and the Institutes of Justice.

-

A Query about Noam Chomsky's Political PhilosophyIf we compare Nozick with Chomsky, then Nozick sets out to make the case for minarchism in the form that trained philosophers go about in making the case for anything, but Chomsky doesn't have this background and may not have realized that anyone expected this of him. — Walter B

This is a half-formed thought of mine as I'm about to pass out in bed, but: as a left-libertarian myself who loves to hear Chomsky speak (haven't read anything of his unfortunately), who came to my position by way of right-libertarianism and a formal philosophical education, I love the axiomatic approach, "the form that trained philosophers go about in making the case for anything", and I enjoy framing my own version of left-libertarianism in such a way (even a propertarian way, decomposing ownership via a Hohfeldian analysis of rights into more primitive deontic notions, and then building back up to an anti-capitalist form of propertarianism from there), so I would love to read somewhere a concise and rigorous axiomatic buildup of Chomsky's views like the OP is asking for, if such a thing exists. Links appreciated. -

Self-studying philosophyI feel like I should give reasons for my earlier recommendations, because looking back on my earlier post I realize it just sounds like a list of authors and fields I like, but it's not just that.

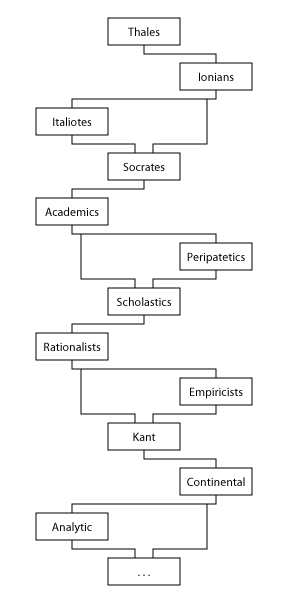

The authors I recommended are because in the history of philosophy, there is a tendency for there to be periods of two opposing camps or trends or schools, and then one philosopher or school of philosophy to unite them, and then two new opposing schools to branch off from that again, back and forth like that. The authors I selected were to give an overview of those opposing schools, and the figures who united them and from whom new ones were formed, as illustrated here:

We don't have a lot of material from Thales, the other Ionians, or the Italiotes (collectively the Presocratics), and their work was really primitive and not super relevant today, so I skipped them entirely. Socrates is really where philosophy as we think of it begins, and his student Plato and Plato's student Aristotle were the founders of the two main opposing schools during the Classical period of philosophy. In the Medieval period things were largely reunited into one school, the Scholastics, of whom Thomas Aquinas is the preeminent figure. The Modern period began with Rene Descartes, the first of what would come to be called Rationalists, and their opposing school, the Empiricists, got their beginning with John Locke. Then Immanuel Kant once again reunited philosophy, until it split again into this Contemporary period's still-unreconciled divide between Analytic and Continental schools, who are too numerous and recent and ongoing to pick preeminent figures for. So that's why I recommend those authors for a historical overview.

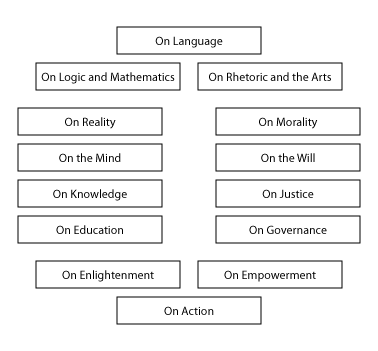

The reason I named the philosophical fields I did is because I think they give a thorough overview of the range of topics philosophy discusses, which all inevitably interrelate with each other. At the most abstract is philosophy of language, and two only slightly less abstract fields that are kind of opposite one another, philosophy of mathematics and philosophy of art. I missed all of those in my formal education and I regret it.

Instead I focused on the two halves of what I'd call core philosophical topics, roughly ontology and epistemology on one hand (about reality and knowledge), and ethics on the other hand (about morality and justice), which I would subdivide into fields analogous to ontology and epistemology (that are also roughly related to utilitarianism and deontology, hence why I emphasized those in particular) but that's not standard practice so I won't go into that here. Metaethics is an especially important part of ethics that ties in closely to philosophy of language, so I recommended that in particular.

Philosophy of mind ties in really closely with ontology and epistemology, and I think free will fits into a similar place regarding ethics because of the connection between free will and moral responsibility. Political philosophy has its obvious connections to ethics as well, being in essence the most important practical application of ethics, and though there doesn't seem to be a single established field that's perfectly analogous to it in relation to ontology and epistemology, I've found significant parallels in both philosophy of education and philosophy of religion, so I recommend those as well.

And lastly, the biggest thing that I overlooked in my formal philosophical education, opposite those abstract fields at the start, is the practical application of philosophy to how to live one's life meaningfully, which Continental schools like existentialism and absurdism address. This topic doesn't seem to have its own name, that I'm aware of, but I colloquially refer to it as "philosophy of life".

The bottom part of this illustration from my philosophy book illustrates the structure I think these fields have to each other:

For these purposes you can ignore everything above Metaphilosophy on that chart, as those are particular views of mine and not philosophical topics (this is actually a chart of the structure of my book, the latter part of which is structured after this same array of topics).

Speaking of which, add Metaphilosophy to my list of fields worth studying. What even is philosophy, what is it trying to do, what constitutes progress at doing that, how can we do it, what does it take to do it, who should do it, and why does it even matter? -

Nothing, Something and EverythingThat's correct, provided we can take "younger than 15 billion years" to be equivalent to "no older than 15 billion years". (Technically we can't, because cases where things are exactly 15 billion years differ between those two formulations, but I think you probably meant the latter).

-

Which is the real world?Big bad things are relatively rare and so are newsworthy. Little good things are everywhere. Little bad things are dealt with. Big good things are exceedingly rare and so usually unavailable to report on.

So you look around you personally and you see lots of little good things happening and little bad things being dealt with and that’s so common it’s not reported on. Then the media rounds up all of the rare big bad things from around the world, not mentioning all the little good things going on in everyone else’s lives, and it looks to you like a false picture of the world. But both worlds are true, you just have to remember that there’s a whole world full of unremarkable little okay lives not being reported on.

But also, it sounds like you do live in a place where things are pretty nice, on the global scale. It’s also useful to be aware that you’ve probably got it a lot better than many, many other people. But it’s still not a world of total darkness like the news reports: even people living much harder lives still have lots of little good things to enjoy, and their hardships usually mostly amount to lots more little bad things they have to deal with. -

Nothing, Something and EverythingNo, same sense. If you want to say nothing is older than 15 billion years in formal logic, you’d use the same symbols (either not-something or everything-not) as you would to say nothing in that room is red, you just wouldn’t specify a set you’re picking from on the first case. You select a number of subjects (possibly zero) and apply a predicate to them either way. To select all, you can select zero and apply the negation of the predicate you want applied to all.

-

Nothing, Something and EverythingIf there are zero things to be had, then you have nothing. — creativesoul

That is also true on the modern account. Because “everything” is equivalent to “nothing not”: nothing is not red if and only if everything is red. That’s pretty uncontroversial isn’t it? It only becomes an apparent problem if there is nothing whatsoever in the universe of discourse. Because then nothing is not red, and nothing is red, because there is nothing whatsoever; but since everything is red iff nothing is not red, then in that circumstance everything is red, and since everything is non-red iff nothing is red, then everything is non-red in that circumstance too. It would be a contradiction if there was some thing that was both red and non-red, but thankfully we’re not saying something is red or something is non-red, we’re saying nothing is non-red and nothing is red, which just says that there’s nothing at all. -

Nothing, Something and EverythingYes, that's exactly the kind of case. I brought it up to make a logical point, but in practice (hence practically unused) when do we ever talk about how much of a set of zero things some predicate applies to?

:up: but that is a little circular as you're employing the very logic that's being questioned here. Aristotelian logic basically had "everything entails something" as an axiom (not that it was really an axiomatic system, but loosely speaking). The modern, axiomatized logic you're employing looked at that and say "ehhhh that's not really necessary and it's a cleaner system without it". -

Nothing, Something and EverythingAristotle had a problem with that as well, but modern logicians have generally agreed that it's really not a problem because practically speaking we never really talk about empty sets, and it's really useful mathematically to have a DeMorgan dual of "something" (a function that just means "not-something-not"), and the sense of "everything" that you and Aristotle want to use is really, really close to that, except in the practically unused case of talking about empty sets. The Aristotelian sense of "everything" is "not-something-not, and also, something", which only differs from "not-something-not" simpliciter when you're talking about an empty set, which we generally never do in practice.

-

The "Fuck You, Greta" MovementBy talking about incentives, I mean exactly making sure that the market price accurately reflects the real costs. If non-renewables are causing a public harm, then that cost needs to be factored into the market cost of them (by making the producers and/or users of them bear that cost -- which is a matter of politics, since this is a tragedy of the commons situation) so that there will be appropriate market pressures to transfer away from them.

-

Why we cannot prayIf Alice says she's anti-man because she hates straw and men are all made of straw, and Bob corrects her that generally men are not actually made of straw, does that not mean that Alice isn't actually anti-man, even if she is anti-straw, since men are not actually made of straw? She may call herself anti-man but if all she cares about is avoiding straw, then she doesn't have any actual conflict with non-straw men, does she? And more to the point, men are actually made of the same stuff as women are, not the straw that women like Alice claim they're made of, so men are just like women in the respect that Alice is concerned with.

-

What is Leibniz' "Plenum"?That is an unresolved question in contemporary physics. General relativity treats space as continuous, while quantum mechanics treats everything as discrete (which is what the "quantum" part means). The two have yet to be reconciled with each other, but yeah it is generally expected that there will be found some way of quantizing space and time (and thereby gravity), we just don't know for sure what it is yet.

But also, both theories in effect treat space as a plenum. In GR, space itself is a significant feature of the universe, so since there is space everywhere definitionally, and it's all got some curvature and energy and gravitational effects and so forth, then no space is really empty in GR, even if there was "nothing" in it. But meanwhile in QM, every particle is viewed as an excitation in a quantum field of infinite extent, where a field is by definition a mathematical object which has a value everywhere, so "field" is almost a synonym for "plenum"; there aren't, for example, hard boundaries on an electron, but rather some degree of "electron-ness" everywhere, of which electrons as we know them are sharp little local concentrations; and likewise with all other particles. -

Why we cannot prayAre you saying that theists actually agree with atheists, and atheists just falsely believe that theists disagree with them? Because atheists are saying "this is what I take religion to be and I disagree with it", so if you say they take religion to be something it's not, then what they disagree with is not what you actually believe, ergo you actually agree with them.

-

Why we cannot prayTo supplicate means to ask or beg for something. How is that different from petition?

-

What is Leibniz' "Plenum"?A plenum is a space filled through and through, with no true gaps or voids in between things, though there may be different stuff (or different amounts of stuff) at different points in the space. This is in contrast to the concept of a space where objects have definite hard boundaries, where there is stuff inside those boundaries and there is truly absolutely nothing outside their boundaries, between the objects.

I'm trying hard to think of a real-world example or analogy, and the best I can think of right now is the difference between a digital signal and an analog signal. A digital signal is always either 100% on or 100% off, 1 or 0. But an analog signal is never truly "off": it's just different degrees of amplitude. The later is like a plenum, the former is like atoms in a void.

Leibniz doesn't seem to be arguing here that space is a plenum, just assuming that we already know it is, because he doesn't seem to give any reasons for it in the quoted bit. He's just saying that since it is (every point in space is filled with some thing or other, none of it is truly empty), if every thing was exactly the same as every other thing, there would be no discernible change, because if you swap two identical things you can't tell the difference. If space were not a plenum, that would not be the case, because you would still have the arrangement of identical things and the gaps between them changing around.

It's like saying that since every point in an image is filled with some pixel or another, if all pixels were the same color we wouldn't see any change as they moved around. But if there was such a thing as a non-pixel, like if screens were transparent except where pixels got filled in, then even if all pixels were the same color we could still see patterns changing in where there were or were not pixels. -

Nothing, Something and EverythingOkay, I'll give this one more try, because I'm a sucker for difficult students apparently.

There are three people, Alice, Bob, and Chris. Each of them has a storage unit. To start with, we don't know what if anything they each have in their storage. But then, each of them tells us something about what they each have in their storage.

Alice tells us that nothing in her storage is red.

We still don't know whether she has anything at all in her storage.

Because we don't know if she has something non-red in her storage instead.

But we do know that she does not have something red in her storage.

And we equivalently know that everything in her storage is non-red.

The bolded bits are all equivalent:

Nothing is = not-something is = everything is not.

Bob tells us that something in his storage is red.

We don't know if he has anything non-red in his storage.

So we don't know whether or not everything in his storage is red (though it might be, if in addition to having something red, he also has nothing non-red. This is the only point I've really been trying to get through to you.)

But we do know that he does not have nothing red in his storage.

And we equivalently know that not everything in his storage is non-red.

The bolded bits are all equivalent:

Something is = not-nothing is = not everything is not.

Chris tells us that everything in their storage is red.

We still don't know whether they have anything at all in their storage (because "everything" might be nothing, if they don't have anything at all in their storage. This seems to be what you're getting hung up on, missing the point above.)

All we know is that nothing in their storage is non-red.

Or equivalently, that they do not have something non-red in their storage.

The bolded bits are all equivalent:

Everything is = nothing is not = not-something is not. -

We are not fit to live under or run governments as we do in the modern world.To be fair I didn’t notice that you got it right after you got it wrong, so I’m glad it was just a momentary mistake and not a fundamental misunderstanding.

-

Nothing, Something and EverythingPlease stop with the condescension. This is standard logic I’m trying to teach you, not my own argument I’m putting forth for debate. You can read all about this in any logic text you care to search for too, probably explained better than I am doing.

Why? It has proof value. Your proposition has been disproven by a proof-value tool. — god must be atheist

It has not, and I did address your point, but that explanation seemed to be raising more questions than it answered for you so it’s clearly not the best educational tool for this job.

objects can be red. Nothing cannot be red. Therefore your first premise is wrong. The rest of your argument can be discarded. — god must be atheist

You don’t seem to understand the structure of what I was saying. I was giving three different cases involving the things that may or may not be in the room. In one of those cases we know there is at least one thing in the room. In the other two cases we don’t know how many things are in the room at all, only that IF anything is in the room THEN it is... whatever.

That’s the point of the explanation: “all A are B” is equivalent to “if something is an A then it’s a B”. So “everything in the room is red” is equivalent to “if something is in the room then it’s red”, or “nothing in the room is non-red”. But there might not be anything in the room at all, and that’d still be true.

And back to the original point: if something in the room is red, and nothing in the room is non-red, then everything in the room is red, so it can easily be the case that both something and everything in the room is red. But that doesn’t make “something” and “everything” equivalents, because it could instead be the case that some things in the room are red and other things are non-red, in which case something but not everything in the room is red. You seem to want to restrict “something” to only this case, but that’s just not how the word works. You’d have to say “only some things” or such to get that meaning. -

We are not fit to live under or run governments as we do in the modern world.The very first line of the post I was responding to was:

Anarchy means, literally, "no rule". — god must be atheist -

Nothing, Something and EverythingIt is probable that you own every time-traveling car ever built on Earth, and that you also own none of the time-traveling cars ever built on Earth, because there are probably no time-traveling cars that have ever been built on Earth.

Other than that, spot on. -

Nothing, Something and EverythingEverything doesn't imply at least one thing, because there might be zero things to begin with, in which case everything in that set of zero things is less than one thing.

Logicians are well aware that this sounds very weird to the untrained ear, but that's just because we pretty much never have reason in normal life to talk about empty sets. But strictly speaking this is how the logic works out when you don't forcibly exclude them. -

Nothing, Something and EverythingForget about the Venn diagram. That's just for illustration but it seems to only be confusing you more. (For the record though, I'm not saying you have to apply different rules to the outside area, but that if you find yourself talking about the outside area, you can conclude you must be talking about an empty set, because there's no other way to dealing with something out there, to have none and all simultaneously, unless "all" is zero).

Let's talk about a more concrete example instead. There's a room with a number of things in it, bearing in mind that zero is a number so the room might have zero things in it, or it might have more than zero, I'm not specifying either way.

If we know that everything in the room is red,

then we know it is not the case that something in the room is non-red,

and we know it is the case that nothing in the room is non-red.

(All = not some not = none-not).

So far as we know in this case it could either be the case that somethings in room is red, or that nothing in the room is red. If there is something in the room at all, we know it must be red, but there might be nothing in the room at all, in which case it's still true that everything (all zero things) in the room are red, i.e. nothing in the room is non-red. All we know is that if something is in that room, it is red.

On the other hand if we know only that something in the room is red,

then we know it is not the case that nothing in the room is red,

and we know it is not the case that everything in the room is non-red.

(Some = not-none = not-all-not).

We know for sure in this case that there is something in the room, because if there is something red in the room there has to be something in the room. But we don't know if everything in the room is red or not. It might be, if there are no non-red things in addition to the red things (this is the case the Venn diagram was meant to illustrate, and that @khaled sums up nicely above: that something doesn't imply not everything, although a phrase like "only some things" would); but it might not be everything, if there are some non-red things in addition to the red things.

"Something" and "everything" can but don't have to overlap. You can have:

neither something nor everything (if there are things to be had but you have none of them).

something but not everything (if there are some things you don't have and some you do),

both something and everything (if there are things to be had and you have all of them),

not something but still everything (if there are zero things to be had and you have all zero of them),

Lastly, if we know that nothing in the room is red,

then we know it is not the case that something in the room is red,

and we know it is the case that everything in the room is non-red.

(None = not-some = all-not).

This illustrates perhaps most clearly why "everything" and "nothing" can apply at the same time, if you have zero things. If nothing in the room is red, then everything in the room is non-red, and vice versa. If nothing in the room is non-red, then everything in the room is red, and vice versa. So if nothing in the room is red and nothing in the room is non-red, you can conclude that there must be nothing in the room at all. And if everything in the room is red and everything in the room is non-red, you can likewise conclude that there is nothing in the room at all, because (aside from the fact that otherwise there would be a contradiction) each of those "everything" statements translates into a "nothing" applied to the negation of its operand. -

Does the Atom Prove Anaximander's Apeiron Theory?Short version is that back when presocratic philosphers were arguing that “all is fire” or “all is air” and so on, Anaximander introduced the idea that everything is indeed made of one substance, but it’s not one of those traditional elements or anything else with which we are familiar, because those are all forms of this same one, undefined (or “boundless”) stuff that underlies all of them.

This was the earliest era of philosophy where a lot of things were really speculative so whatever arguments Anaximander had are not as important as just the fact that he proposed this possibility.

I think the modern physicalist conception of everything being made of energy taking different forms matches pretty well with Anaximander’s “aperion”, myself.

But I can’t make sense of the rest of the OP. -

Nothing, Something and EverythingOnly the fourth category you asked about involves empty sets. The rest involves any sets. And this is bog standard logic, nothing of my own invention.

It’s easier to talk about the terms all, some, and none, and then translate that into everything, something, and nothing (as everything = all the things, something = some of the things, and nothing = none of the things), so I’m just gonna do that from now on.

What is the relationship between all, some, and none? That is the question at hand here, basically.

Pretty uncontroversially, none = not some.

That requires that some = not none as well.

So we know the relationship of some and none to each other easily enough. Now what of all?

Well, if all of A are B, then none of A are not B, pretty uncontroversially.

But if there are no A at all, then it’s true that no A are B, because no A are anything.

Aristotle thought that means that “no A are not B” wasn’t a full definition of “all A are B”, and that it required an additional “and some A are B”.

Modern logicians say that’s not necessary, “no A are not B” is fine, and if that makes a weird case out of empty sets, so be it, because how often do we care to talk about empty sets.

So to modern logician, all = none not.

And since none = not some, that means all = not some not.

This is a kind of relationship called a DeMorgan duals, where one function is the negation of the other function on a negation, and vice versa.

So some = not all not. Which makes sense: if not all A are not B, then some A must be B.

And since none = not some, that means none = all not. Which also makes sense: if all A are not B, then none of A are B.

So none = not some = all not.

And some = not none = not all not.

And all = none not = not some not.

And there you go.

You can also coin the negation of all, call it “nall”, and say:

None = not nall not

Some = nall not

All = not nall

And nall = not all = some not = not none not. -

Nothing, Something and EverythingEverything and something are overlapping states, as already described.

The area outside the circles is an interesting thing in modern quantitative logic. All of my children have graduated high school, but none of my children have graduated high school. This is possible because I have no children, so 100% of my 0 children have graduated high school. Since “everything is...” just means “nothing isn’t”, that area outside both circles is for circumstances like this: where it’s not something (so nothing), but also not not-everything (and so everything), which can only be the case when the set we’re choosing from is empty, like the set of my children.

Pfhorrest

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum