-

If there was no God to speak of, would people still feel a spiritual, God-like sensation?I don’t have any professional research on hand to share, but for myself personally I have had sober experiences that match the descriptions I’ve read of “mystical” experiences, and friends who have done LSD say that when I am having those experiences I seem like someone on a “really good trip”, and that their experiences while on LSD also match the descriptions they’ve read of “mystical experiences”.

-

What’s your philosophy?I think perhaps he just means that a paradigm is defined by its unspoken assumptions, which is the way Kuhn coined the term. In which case yeah I pretty much agree with that definition of a paradigm.

To clarify my intent with this thread though, I didn’t mean so much for us all to go through the questions one by one together and try to agree on a philosophical system. I’m just interested in hearing what other individual people’s complete philosophical systems are, phrased as answers to the same set of questions for comparison. -

What’s your philosophy?I’m sure books could be and have been written on each, but I’m just looking for a brief summary answer on each, not even whole essays like I’m working on.

Your comments only reinforce the superficial impression I already had of Wittgenstein that he’s one of those “shut up and just run with my unspoken assumptions as the natural default instead of making up a bunch of different stuff I don’t agree with” types. Like capitalists are regarding property rights. Mostly that impression comes from a quote about the proper method of philosophy being to speak only the propositions of the natural sciences... but Witty, what makes something a natural science or not, what do their propositions mean, how can we judge them, etc... also you’re telling me to do something, pretty sure imperatives are not propositions of natural sciences, how do I decide whether to obey such commands or not, etc... You can be a hardcore physicalist (as I am) and not tell everyone to shut up about all philosophy. -

"Agnosticism"You don't think our actions that are can be based on abstract ideas don't have any concrete effects? — ssu

Our actions do, the ideas by themselves don’t. You won’t find a number 3 somewhere out in the universe doing things on its own. You will find people doing things in various threefold ways. And even atheists agree that people do things in ways that employ their ideas of God, all they disagree with theists about is whether you’re going to find a God out there somewhere doing things on its own.

But they aren't talking about that. It's about the existence of God, not what God is. And as I've done now for a long time, I've tried to explain that existence isn't such a straightforward thing as it is to a physicalist / materialist. — ssu

I’m not clear what you’re saying here. I’m saying that if by “God” you mean something that only “exists” in some non-concrete non-objective sense, abstractly or socially or subjectively, then you’re not even talking about the same thing that most theists and atheists are arguing about. You’re not taking a position on the same issue and saying you don’t know if that thing we’re talking about does or doesn’t exist; you’re apparently just affirming that some other thing entirely exists. -

What’s your philosophy?Would you like to do a summary of Wittgenstein’s answers to these questions for everyone’s edification? I’m not sure I’ve actually read much of him; I feel like there must have been some excerpts at least somewhere in some class but I can’t really place anything particular and I don’t feel like I have more than a passing familiarity with him.

-

"Agnosticism"So everything that is abstract are only words? That sounds like classic straightforward physicalism to me. — ssu

I never said I wasn’t a physicalist. And my view on abstract objects isn’t quite as simple as that (that would be nominalism, whereas my view is mathematicism) but in any case abstract objects don’t have any concrete effects on the world we’re a part of — that would make them concrete.

Exactly. But I was talking about reasons for agnosticism, not about the overtly dogmatic reasoning of theists / atheists. — ssu

Theism/atheism and gnosticism/agnosticism purport to be views about the same thing though: God. If they’re talking about different conceptions of God, then someone could simultaneously be a theist and an atheist, a gnostic and an agnostic, all of them at the same time in different senses. Before one can say which of these positions one takes on the existence of “God”, one had to decide what “God” means. And if you take “God” to mean something different than what theists and atheists disagree about, then you’re just going to confuse everyone when you state your position on it.

Theists generally mean something or another that actually has some effect on our world, and that’s what atheists disagree with them about, and what normal agnostics are unsure of, whether they lean theist or atheist. Atheists don’t deny that e.g. love exists, so if someone just means “God” as “love” then that‘s only a disagreement of words. Atheists don’t deny that the universe exists, so if a naturalistic pantheist like I used to be just means “God” as “the universe”, then that’s also just a disagreement of words, which is why I stopped doing that. Likewise with all the other senses (abstract, constructivist, subjective) of “God” we talked about above. -

"Agnosticism"

To say that God exists only abstractly and not concretely is only to say that you have some definition of a thing you've named "God" that you can logically infer things about from your definition, but that that thing is not instantiated in the universe we are a part of, or in any other way connected to it.

To say that that God exists only as a social construct is only to say that people behave as though something they call God exists.

To say that God exists only subjectively is only to say that people think or feel that God exists.

None of these things seem to be what your ordinary run-of-the-mill theists are talking about, the kind of people who think there is a God who created the universe/Earth/humans and intervened in various ways throughout history and has some other realm like heaven where it can transport some part of a human being like a soul after death, and interact meaningfully with that soul in heaven.

None of that stuff makes any sense if by "God" you just mean one of the above things. All of those usual theistic trappings hinge on it being objectively true that some kind of God concretely exists, in a way that actually has effects on the universe. And even atheists won't deny that the above things "exist" in their respective senses -- obviously people think or feel that God exists, they behave as though there is such a thing, and some of them define what they take that thing to be and infer things about it from that definition -- so if that's all anyone meant by "God", there would be no distinction between theists and atheists at all.

Which brings us to...

For a trivial example, the big bang is the origin of all on a naturalistic atheistic view grounded in modern scientific models. Would you say that the big bang is such peoples’ god then? -

"Agnosticism"I think you mean to say "polytheism" when you say "pantheism". Pantheism is the belief that the universe itself is identifiable with God. Polytheism is the belief in multiple gods.

In any case, what you take your God or gods to be like is besides the point. "At least one god" was just meant to be inclusive of polytheists, who are also still theists.

But beside that, if you want to characterize your conception of God as being so metaphysical that it's not accurate to say that he "exists"... then congratulations, you don't disagree with atheists. That's actually what made me stop calling myself a pantheist (in the accurate sense of thinking the universe itself is God). I realized that I was just slapping the label "God" onto something that even atheists believe in (the universe itself), and so not really asserting anything that differentiated me from an atheist, so I just decided to stop creating needless confusion and just admit to being one.

If "the first principle, ground of being, or origin of all" is all you mean by God, without any particular claims about what that thing / those things are like, then you don't necessarily disagree with atheists about anything, who also have first principles, grounds of being, and origins of all in their various philosophies, they just don't say "...and that thing is God" at the end. -

If there was no God to speak of, would people still feel a spiritual, God-like sensation?Yes, the so-called "religious experience" or "mystical experience" is a neurochemical phenomenon that can be induced with drugs, and occurs (without drugs) even in strong atheists like me.

I've recently come to the conclusion that the opposite of that experience, a non-rational feeling of abject meaninglessness rather than a non-rational feeling of profound meaningfulness, is what fuels the otherwise nonsensical "what is the meaning of life?" question that so many people have, that feeling of existential angst, dread, or horror. It's a false philosophical non-problem, masking a very real and tragic emotional problem.

I've coined the terms "ontophilia" (love of being) and "ontophobia" (fear of being) for those two feelings, respectively. And inasmuch as "what is the meaning of life?" might mean "what is the purpose of life?", and purpose is just whatever something is good for, and goodness is grounded in hedonic pleasure and flourishing and the avoidance of pain and suffering, I'd say that attaining and maintaining and spreading and cultivating ontophilia, that blissful non-rational feeling of meaningfulness, is itself the pragmatic meaning of life, the highest pleasure we should be striving for and sharing with others. -

"Agnosticism"If you've seen anything I've commented in other threads, you know that I explicitly deny that religion is defined in terms of God. But theism and atheism are. There are atheistic religions. There are irreligious theists. Religion or irreligion is about why and how you believe whatever you do, not about what you believe. But "theism" just means "belief in God", and "atheism" just means "not theism". And I never said agnostics are confused or anything like that, so I think you must be projecting something from an argument with someone else.

The rest of this is really off-topic, but sure I'll answer your questions:

Do numbers exist? — ssu

Not concretely, but abstractly, where on my account concrete existence is an indexical subset of abstract existence: the things that concretely exist are the things that are part of the same abstract structure as we are, but other abstract structures besides that one (such as numbers) also exist in an abstract sense. (And number-like substructures are also part of the larger abstract structure that is our concrete universe).

Does beauty/value/morals exist? — ssu

Things of beauty and value exist, and judgements of beauty and value can be objectively correct, so there exist things that are objectively beautiful or valuable, but beauty and value aren't things or even descriptive properties, so existence doesn't apply to them.

Does inflation, money, value, countries exist? — ssu

Inflation is a process that occurs to money, which "exists" as a social construct, which is to say that talk about money is actually talk about people's opinions and behaviors, which definitely exist. People do in fact treat things as money, and the value of it to them does decrease as the supply of it increases.

I already covered value more generally above.

And countries are physical places, which definitely exist. -

"Agnosticism"Theism/atheism and gnosticisism/agnosticism are orthogonal issues.

- Theists believe in at least one god

- Weak atheists don't believe in any gods

- Strong atheists believe there are no gods

Orthogonaly:

- Gnostics think their beliefs constitute knowledge

- Weak agnostics don't think their beliefs constitute knowledge

- Strong agnostics don't think there can be knowledge on the matter

You can be any combination of those things.

- Gnostic theists think they know that at least one god exists.

- Weak-agnostic theists don't think they know whether any gods exist, but they believe at least one does

- Strong-agnostic theists don't think it can be known whether any gods exists, but they believe at least one does.

- Gnostic weak atheists... hmm actually I'm not sure this combination actually is coherent. They think they know that there is no reason to think any gods exist?

- Weak agnostic weak atheists don't think they know whether any gods exists, but they don't believe in any

- Strong agnostic weak atheists think it can't be known whether any gods exists, but they don't believe in any

- Gnostic strong atheists think they know that no gods exist.

- Weak agnostic strong atheists don't think they know that no gods exist, but they believe that no gods exists.

- Strong agnostic strong atheists think it can't be known whether any gods exists, but they believe that no gods exist.

-

Modern Ethics“Degenerate” suggests we’ve gone backward somehow, when if anything we’ve haphazardly come forward slowly over time. There is still room for improvement though, such as I suggested in my first post in this thread.

-

Modern EthicsGetting kind of tired of hearing this baseless claim that "atheists have no systems" over and over again.

-

Is there nothing to say about nothing"Nothing", together with "something", "everything", and "not everything" (or, if you will, "neverything"), is just part of one of many sets of four DeMorgan dual concepts that all bear the same relationship to each other, the relationship of none, some, all, and not-all (or, if you will, "nall").

None = all-not = not-some = not-nall-not

Some = nall-not = not-none = not-all-not

All = none-not = not-nall = not-some-not

Nall = some-not = not-all = not-none-not

Since nothing = "none of the things", something = "some of the things", everything = "all of the things", and neverything = "nall of the things":

Nothing = everything-not = not-something = not-neverything-not

Something = neverything-not = not-nothing = not-everything-not

Everything = nothing-not = not-neverything = not-something-not

Neverything = something-not = not-everything = not-nothing-not

And since impossible = "at none of the possible worlds", possible = "at some of the possible worlds", necessary = "at all of the possible worlds", and contingent = "at none of the possible worlds:

Impossible = necessary-not = not-possible = not-contingent-not

Possible = contingent-not = not-impossible = not-necessary-not

Necessary = impossible-not = not-contingent = not-possible-not

Contingent = possible-not = not-necessary = not-impossible-not

And since impermissible, permissible, obligatory, and supererogatory bear all the same relations to possible worlds as those alethic modalities but with a deontic direction of fit instead:

Impermissible = obligatory-not = not-permissible = not-supererogatory-not

Permissible = supererogatory-not = not-impermissible = not-obligatory-not

Obligatory = impermissible-not = not-supererogatory = not-permissible-not

Supererogatory = permissible-not = not-obligatory = not-impermissible-not

There are probably others I'm overlooking too. Even the ordinary boolean operators NOR, OR, AND, and NAND are just two-place versions of some, none, all, and nall, so:

NOR = AND-not = not-OR = not-NAND-not

OR = NAND-not = not-NOR = not-AND-not

AND = NOR-not = not-NAND = not-OR-not

NAND = OR-not = not-AND = not-NOR-not

And I'd argue that in all of these cases, the first one, based on "none", is really the most primitive and fundamental, because all of the boolean logical operators, not just these ones but IF, ONlY-IF, IFF, XOR, and so on, can be built out of nothing but NORs. (True, they can also be built out of nothing but NANDs, but that just seems like a weird and convoluted consequence of NAND being the negation of the NOR of negations). -

Is there nothing to say about nothingIt's not a matter of plurality or singularity. The point is that there isn't any special kind of thing(s) that has(/have) to exist at any possible world; just that some kind of thing(s) or (an)other must exist at each possible world. They can all be completely different things at every possible world, and it doesn't matter what they are, so long as there's something there.

-

Modern EthicsAssuming we can adequately define reason, did rational thinking make human beings more ethical in the past, perhaps in Plato's era, and is this still the case? — Enrique

Rationality is a tool, one that can be used toward many ends. Those who are trying to be ethical will be more successful if they use that tool well, but just having that tool doesn't mean that people are going to use it toward that end.

Do questions of ethics even apply to modern civilization, or are we living in a post-ethics world? — Enrique

What would a post-ethics world even be like? Ethical questions are continuously applicable to everyone everywhere all the time. Every time anybody wonders what to do, that is an ethical question. The closest thing to a post-ethics world I can conceive of would be a world wherein nobody's actions ever had any consequences whatsoever, so it didn't matter what anybody did; but even in such a world, there is still room for ethical judgement of the things that are happening, even if nobody can do anything about them.

What kind of paradigm for defining human behavior philosophically would be relevant in a modern discourse? What are the currently prevailing theories in this area? — Enrique

Aside from brute legalism ("do what the law says because the law says so and besides we'll shoot you if you don't" -- including Divine Command Theory in that category), which seems to still be the first thing that most unthinking people turn to, the prevailing approach among thinking people today appears to be utilitarianism, with Kantian deontology constantly trying to give it a run for its money. There are veins of virtue ethics still around today too but they don't seem nearly as popular as the other two.

My own view takes a kind of in-between approach between utilitarianism and deontology, and that seems to be a popular thing to attempt (see for example rule utilitarianism, or rights as deontological side-constraints on otherwise utilitarian ethics) since there are well-known problems with both ordinary views of utilitarianism and deonology.

The version of that approach I advance is basically the ethical equivalent of falsificationism. Just as falsificationism says that of course evidence is important, but evidence cannot ever confirm a theory (anti-confirmationism), it can only falsify it, so too I say that of course maximizing pleasure and flourishing and minimizing pain and suffering is important, like utilitarianism says, but those consequences cannot ever justify an action (anti-consequentialism), they can only rule it out. And then on top of that, a libertarian theory of rights grounded in the definition of property serves a role in normative decisions similar to that which logical considerations, grounded in the definitions of words, serves in factual investigation. -

Is there nothing to say about nothingNothing can't exist. — Pfhorrest

[...]

So, what would the mandatory existent be like that just is, but has no direction put into it? — PoeticUniverse

This question implicitly commits a logical error that predicate logic was invented to avoid. Consider the sentence "every mouse fears some cat". You might mean that for each mouse, there is some cat or another that that mouse fears, maybe not the same cat feared by all mice. Or you might mean that there is some one cat in particular of whom all mice are afraid. Saying the former doesn't imply the latter. In predicate logic we would distinguish these two sentences from each other as:

For every mouse, there exists some cat, such that the mouse fears the cat.

and

There exists some cat, such that for every mouse, the mouse fears the cat.

In our case, I'm saying that nothing can't possible exist, and therefore that something or another must necessarily exit; but you're taking that to mean that there is some one particular thing that must necessarily exist, which is not implied by the first statement. It's the difference between:

At every possible world, there exists some thing, such that the thing exists in the world.

and

There exists some thing, such that at every possible world, the thing exists in the world.

Cosmological arguments for God generally commit this same error, taking the generally agreed upon statement "everything comes from something", which is to say:

For every thing, there exists some other thing, such that the thing came from the other thing.

...which is perfectly compatible with there being infinite chains of creation or even loops in principle, and takes it to be equivalent to or at least to imply:

There exists some other thing, such that for every thing, that thing came from the other thing.

...and then they proceed to call that erroneously-inferred first cause (the "other thing") "God". -

Is there nothing to say about nothingOn a different topic, I have something else to say about nothing. Why is there something rather than nothing? Well, on a modal realist account, it's trivially because there exists no possible world at which there is no world, which translates back to normal modal language as saying that it is not possible for there to be nothing. Nothing can't exist.

-

Is there nothing to say about nothingConstructing fundamental mathematical objects out of sets is like constructing bricks out of houses. — A Seagull

I can see why you would think that, but that's how modern mathematicians do it.

The natural numbers, for instance, meaning the counting numbers {0, 1, 2, 3, ...}, are easily defined in terms of sets. First we define a series of sets, starting with the empty set, and then a set that only contains that one empty set, and then a set that only contains those two preceding sets, and then a set that contains only those three preceding sets, and so on, at each step of the series defining the next set as the union of the previous set and a set containing only that previous set. We can then define some set operations (which I won't detail here) that relate those sets in that series to each other in the same way that the arithmetic operations of addition and multiplication relate natural numbers to each other. We could name those sets and those operations however we like, but if we name the series of sets "zero", "one", "two", "three", and so on, and name those operations "addition" and "multiplication", then when we talk about those operations on that series of sets, there is no way to tell if we are just talking about some made-up operations on a made-up series of sets, or if we were talking about actual addition and multiplication on actual natural numbers: all of the same things would be necessarily true in both cases, e.g. doing the set operation we called "addition" on the set we called "two" and another copy of that set called "two" creates the set that we called "four". Because these sets and these operations on them are fundamentally indistinguishable from addition and multiplication on numbers, they are functionally identical: those operations on those sets just are the same thing as addition and multiplication on the natural numbers.

All kinds of mathematical structures, by which I don't just mean a whole lot of different mathematical structures but literally every mathematical structure studied in mathematics today, can be built up out of sets this way. The integers, or whole numbers, can be built out the natural numbers (which are built out of sets) as equivalence classes (a kind of set) of ordered pairs (a kind of set) of natural numbers, meaning in short that each integer is identical to some set of equivalent sets of two natural numbers in order, those sets of two natural numbers in order that are equal when one is subtracted from the other: the integers are all the things you can get by subtracting one natural number from another. Similarly, the rational numbers can be defined as equivalence classes of ordered pairs of integers in a way that means that the rationals are the things you can get by dividing one integer by another. The real numbers, including irrational numbers like pi and the square root of 2, can be constructed out of sets of rational numbers in a process too complicated to detail here (something called a Dedekind-complete ordered field, where a field is itself a kind of set). The complex numbers, including things like the square root of negative one, can be constructed out of ordered pairs of real numbers; and further hypercomplex numbers, including things called quaternions and octonions, can be built out of larger ordered sets of real numbers, which are built out of complicated sets of rational numbers, which are built out of sets of integers, which are built out of sets of natural numbers, which are built out of sets built out of sets of just the empty set. So from nothing but the empty set, we can build up to all complicated manner of fancy numbers.

But it is not just numbers that can be built out of sets. For example, all manner of geometric objects are also built out of sets as well. All abstract geometric objects can be reduced to sets of abstract geometric points, and a kind of function called a coordinate system maps such sets of points onto sets of numbers in a one-to-one manner, which is hence reversible: a coordinate system can be seen as turning sets of numbers into sets of points as well. For example, the set of real numbers can be mapped onto the usual kind of straight, continuous line considered in elementary geometry, and so the real numbers can be considered to form such a line; similarly, the complex numbers can be considered to form a flat, continuous plane. Different coordinate systems can map different numbers to different points without changing any features of the resulting geometric object, so the points, of which all geometric objects are built, can be considered the equivalence classes (a kind of set) of all the numbers (also made of sets) that any possible coordinate system could map to them. Things like lines and planes are examples of the more general type of object called a space. Spaces can be very different in nature depending on exactly how they are constructed, but a space that locally resembles the usual kind of straight and flat spaces we intuitively speak of (called Euclidian spaces) is an object called a manifold, and such a space that, like the real number line and the complex number plane, is continuous in the way required to do calculus on it, is called a differentiable manifold. Such a differentiable manifold is basically just a slight generalization of the usual kind of flat, continuous space we intuitively think of space as being, and it, as shown, can be built entirely out of sets of sets of ultimately empty sets.

Meanwhile, a special type of set defined such that any two elements in it can be combined through some operation to produce a third element of it, in a way obeying a few rules that I won't detail here, constitutes a mathematical object called a group. A differentiable manifold, being a set, can also be a group, if it follows the rules that define a group, and when it does, that is called a Lie group. Also meanwhile, another special kind of set whose members can be sorted into a two-dimensional array constitutes a mathematical object called a matrix, which can be treated in many ways like a fancy kind of number that can be added, multiplied, etc. A square matrix (one with its dimensions being of equal length) of complex numbers that obeys some other rules that I once again won't detail here is called a unitary matrix. Matrices can be the "numbers" that make up a geometric space, including a differentiable manifold, including a Lie group, and when a Lie group is made of unitary matrices, it constitutes a unitary group. And lastly, a unitary group that obeys another rule I won't bother detailing here is called a special unitary group. This makes a special unitary group essentially a space of the kind we would intuitively expect a space to be like — locally flat-ish, smooth and continuous, etc — but where every point in that space is a particular kind of square matrix of complex numbers, that all obey certain rules under certain operations on them, with different kinds of special unitary groups being made of matrices of different sizes.

I have hastily recounted here the construction of this specific and complicated mathematical object, the special unitary group, out of bare, empty sets, because that special unitary group is considered by contemporary theories of physics to be the fundamental kind of thing that the most elementary physical objects, quantum fields, are literally made of. So everything in reality can in principle be arduously constructed out of empty sets, transformed through operations that can all be constructed out of repeated use of (basically) negation. -

The False Argument of FaithOnce again it's important to point out the difference between "faith" as in believing something that isn't conclusively proven from the ground up, and "faith" as in believing something regardless of evidence to the contrary and refusing to question whether it might not be true.

One is a guess, the other is a conviction.

Guesses that are admitted to be guesses are fine, and yes all knowledge is based on them, because nothing can be conclusively proven from the ground up. Unquestionable convictions are the problem. And refusing to allow people to run with their best guesses just is asserting an unquestionable conviction to the contrary of whatever those guesses would be, so to be against faith-as-in-convictions just is to be accepting of "faith"-as-in-guesses. -

The False Argument of FaithI think something went wrong with your post. Below "I created this arrangement:" all I see is "dateposted-public" where I suspect was supposed to be some kind of table or diagram. EDIT: while I was posting that you changed it to an image link.

Anyway yeah, that's pretty straightforward. Appeal to faith is a pretty well-known fallacy, and there's not much you can do in response. "Opinions not founded in reason cannot be swayed by it" or something to that effect is a popular aphorism. (Apparently of uncertain origin and phrasing). -

Why is so much rambling theological verbiage given space on 'The Philosophy Forum' ?I'm just affirming the is-ought distinction, though not the cognitivist-noncognitivist implications often carried by it. I don't think that prescriptive assertions can be inferred from only descriptive assertions, so what is real is a separate question from what is moral. We could know nothing about reality and still figure out things about morality.

Thanks to the ambiguity of language, we could in a sense talk about what prescriptive assertions are "true" as in correct prescriptions (at least if you're a moral cognitivist like me and I would assume you, and unlike someone like Hume), but that's a different sense (on an account like mine) from talk about what is "true" as in "real", which seemed to be the sense you meant with "what is real, what is true". -

How important is (a)theism to your philosophy?

No, I'm interested to hear from "weak" or "negative" atheists too; people who simply don't hold a belief in God, rather than holding positive disbelief in God.But I guess you are only interested in the dogmatic people here. — ssu

I expected the results to be mostly weak atheists mostly saying that it's just an incidental consequence of their philosophy, and mostly theists saying that it's a core principle of their philosophy, and the results have borne that expectation out. (Though I guess I can't tell how many of the atheists are weak or strong, but the incidentality of their non-belief suggests probable weakness to me, even though I'm my own counterexample being a strong atheist to whom that's an incidental belief). -

How important is (a)theism to your philosophy?Mark, I didn't take you to be having a meltdown. I have meltdowns of my own (that's what I meant about work yesterday), and suspect I might be somewhere on the spectrum myself, so I'm not trying to be judgemental at all. And I'm definitely not saying you can't overcome anything.

It just looked to me like there was misunderstanding happening in the conversation, a misunderstanding related to dialectical charity, and I was just going to comment on that, but as I said, I've had at least two other autistic people (one of them here) tell me that their autism makes specifically that difficult for them, so since you had just mentioned your autism before I could even comment on the charity thing, rather than just suggesting you could stand to be more charitable, I thought perhaps that difficulty might be the case with you too, so I mentioned those other friends.

I'm sorry I upset you, I really didn't mean to. -

Why is so much rambling theological verbiage given space on 'The Philosophy Forum' ?This is a philosophy forum, and the concern ought to be what is real, what is true. — Wayfarer

Not to denigrate truth or reality at all, but philosophy is about much more than just that. For starters it is equally much about goodness and morality, prescription as much as description. But besides that, it's not just about what is real/true and moral/good, but about what those kinds of terms mean, what criteria we might judge assertions of them by, what methods we might use to apply such criteria, what faculties we need to employ those methods, who is to exercise those faculties, and why to care about any of that at all.

So, as much as I'm opposed to religion in general never mind fundamentalism, it's not in appropriate philosophizing to say "its claims may be false but it's still useful in such-and-such way". What is or isn't actually true definitely matters, but it isn't necessarily the only thing that matters. -

How important is (a)theism to your philosophy?Mark, I hope it's clear from our private conversations that I generally like you, so I hope you take this from a friendly place: it seems to me like you're being needlessly antagonistic in this conversation, seeming to take Terrapin to be saying things he doesn't mean. You mentioned earlier that you're autistic, and I don't want to make this all about that, but I am seeing shades of some arguments another autistic friend of mine has had with a mutual friend of ours, so I suspect that that might be a common factor here.

Probably specifically the defining autistic cognitive difficulty with (as you've put it) cognitive empathy making it difficult to accurately tell what another person is thinking and meaning when they say something, which in turn makes it difficult to properly extend the principle of charity to other people. That's what that other friend has suggested is his difficulty that prompts such arguments so frequently; and one of the first conversations I had on these forums was encouraging someone to employ that principle more, and them countering that their autism made that very difficult. I don't think that was you, but please remind me if it was.

In any case I just wanted to share my observation on this conversation and hopefully help you be more aware of some of your own blind spots that might be making it more difficult for you. -

Do you lean more toward Continental or Analytic philosophy?Would you then argue that Analytic philosophy is an offshoot of Continental philosophy, if everything from Kant onward minus everything from Frege onward is Continental? Frege's immediate philosophical ancestor was a Continental?

Consider also other forks in philosophical tradition, like Platonists vs Aristotelians. Both claim everyone up to Socrates in their philosophical heritage, and Aristotle was a student of Plato, but the Aristotelian tradition does not incorporate many Platonic views, but rather opposes many of them. It seems to me, looking back over the history of philosophy, that every schism works that way: at some point everyone agrees on everything up to some philosopher or school of philosophy, but then things start trending in one direction from there, that other people find contentious, and eventually rebel against.

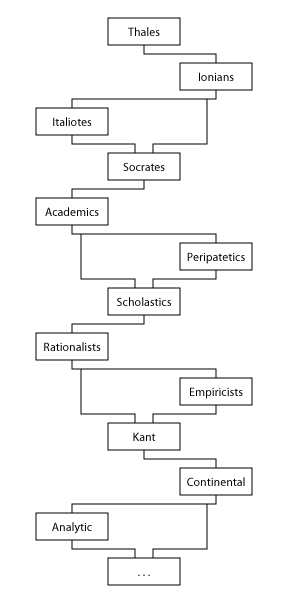

The presocratic schism between Ionians and Italiotes traces back to a common agreement on Thales, then the Ionians following after Thales' student Anaximander, and the Italiotes following after Anaximander's student Pythagoras. The classical era had the common agreement up to Socrates and then a split between his student Plato and Plato's student Aristotle. I'm not aware of a clear schism in the medieval era, thanks probably to the unifying influence of the Church. But then out of that Descartes began the Modern era with Rationalism, and then Empiricism emerged in rebellion against that. Those were united together under Kant, and what would be called the Continentals continued after him, until the Analytics rejected most of their work since him and went on to do their own thing. -

How important is (a)theism to your philosophy?Again, do you have a lack of belief in unicorns? Or Santa Claus? — Pantagruel

Yes, of course.

More than that, I not only don't believe that unicorns or Santa Claus exist, I believe that they don't exist.

(Where "believe X" simply means "think X is true", nothing about justification or lack thereof or anything like that).

Of course there would be no reason to assert such disbelief if there weren't anybody asserting belief. I also don't believe that snarfboggles exist (and believe that snarfboggles don't exist), where a snarfboggle is a small, flying, ugly, hairy creature, like a troll crossed with a fairy, most notable for their incessantly running noses, which I just made up right now to use an an example here. I'll probably never have reason to mention my disbelief in snafboggles outside of this thread, but I have it nevertheless. Belief in unicorns, Santa Claus, or especially God is different though, because those are things that other people actually believe in, that I might have reason to state my disagreement with. -

Do you lean more toward Continental or Analytic philosophy?If I may offer an analogy:

If we were going to write a history of the evolution of humans in particular, not the evolution of all life but just the speciation of the human species, we would logically start with the most recent common ancestor of humans and their closest relatives. We would then describe how some group of that MRCA over time evolved into the origins of the lineage that ends up with humans eventually. To do so is not, however, to claim that MRCA as exclusive to the human lineage; a similar history of bonobo evolution would begin with that same MRCA.

Similarly, a history of Continental philosophy would logically start with the "most recent common ancestor" of both Continental philosophy and its closest "relatives", and then show how some group of that "MRCA" evolved into the Continental branch of contemporary philosophy. But a similar history of Analytic philosophy would begin likewise, starting with Kant as the branch point between Continental and Analytic, the last point of common agreement, and then following early anti-Hegelians etc opposing the way the what-would-be-called Continental school was developing until it came to a head with the Vienna Circle, and the subsequent evolution of Analytic philosophy since then. -

How much philosophical education do you have?I don't think Terrapin was saying that answering the question about your education was un-humble, but that your reaction to his joke seemed less than humble (because it seemed defensive, and defensiveness can be a sign of fragile egotism). But you just didn't get the joke, so I think it's understandable that you would react differently than if you had understood he was joking. And it's clear that there's already some bad blood between you two from elsewhere on the forum, so tensions are understandably high to begin with.

-

Is there nothing to say about nothingI don’t think that’s accurate to say that mathematics says things are made of an infinity of zeros,

but modern mathematics does construct all its objects out of nested sets of sets of ultimately empty sets,

and all of its functions can be constructed exclusively with nested application of the joint denial function (“nor”) which is basically a binary negation operation (“nor(x,x)” is the same as “not(x)”),

so it is fairly accurate to say that everything is made of negations of nothing. -

How important is (a)theism to your philosophy?Agnosticism isn’t listed as an option because that’s an answer to a different question. Agnosticism is orthogonal to theism/atheism. Whether or not you think you do or don’t or can or can’t know whether God exists, either you do think he exists, or not. Atheism most broadly defined is just that “or not”: lack of thinking that God exists. Positively thinking that he doesn’t exist is only a subset of that.

On each of these two orthogonal axes there are three positions.

One axis is:

“I believe (God exists)”, theism

“not-(I believe (God exists))”, weak or broad or negative atheism

“I believe not-(God exists)”, strong or narrow or positive atheism

On an orthogonal axis, regardless to those answers:

“I do know”, gnosticism

“I don’t know”, weak agnosticism

“It can’t be known”, strong agnosticism

For this poll, your position on the second axis isn’t important; I’m only interested in whether or not you occupy the first position on the first axis. -

How important is (a)theism to your philosophy?I'm curious, do poll threads get bumped when people vote in them, or just when people comment in them?

-

How much philosophical education do you have?Yeah I would like to know that too. Or even who the few people with Masters degrees are.

-

Do you lean more toward Continental or Analytic philosophy?Kant is commonly considered the start of the division. — Terrapin Station

That sounds like more or less what I said. Kant is the most recent common ancestor of both Analytic and Continental philosophers, and is studied extensively within contemporary Analytic philosophy departments (like I was educated in) as basically the apex of Modern philosophy, after which we skip all of the intervening Continental stuff and move right on to 20th century Analytic works. He's "not a Continental philosopher" in the same way that Plato isn't; which isn't to say that Continentals don't trace back to either of them, but that neither are exclusive to their branch of the contemporary divide.

I refer to the two traditions as the Anal Tradition and the Incontinent Tradition. :wink: — Janus

I just now on my third re-read caught how clever this is. -

Do you lean more toward Continental or Analytic philosophy?

Well, I'm attempting to write a work of philosophy bridging things "from the meaning of words to the meaning of life", and to quote the introduction of that, "I aim to once again reconcile the linguistic abstraction (as well as the precision, detail, and professionalism) of the contemporary Analytic school, in which I was primarily educated, with the practical and experiential emphasis (as well as the breadth, holism, and personal applicability) of the contemporary Continental school." So, that's where I think we should be headed.What is the next phase of philosophy? Where is it moving? — Metaphyzik

Your definition of analytic philosophy is much too narrow--you seem to basically be equating it with logical positivism/the Vienna Circle as a movement, while your definition of continental philosophy is too broad. — Terrapin Station

That is the historical origin of the division: the positivists and their descendants vs their opponents and their descendants. As time wears on the distinction gets blurrier, so that historical split is where I chose to emphasize the difference. I did try to name some broad characteristics of both movements as well though, and I did miss an important one that you thankfully caught for me (the narrow vs wide focus).

My formal education is almost entirely in Analytic philosophy and I barely know any Continental stuff, so if anything my bias would be toward Analytic; but I try to bridge the gap between the two, so I voted Yes.It suggests a bias to say the least. — Terrapin Station

Kant isn't a Continental philosopher, he predates the division and is pretty much the last philosopher claimed in common heritage by both sides of contemporary philosophy, marking the end of the core era of Modern philosophy that was characterized by the Rationalist vs Empiricist division instead.A handful of continental philosophers--Kant — Terrapin Station

admitting that you have a continental leaning is like admitting that you're a hipster — Terrapin Station

Pfft, hipsters are too mainstream. I didn't give a shit about what was popular before that was cool.

SO the task at hand might be described as reaching continental conclusions using analytic method. — Banno

:up:

How can you answer yes or no to a binary choice between two options that aren’t yes or no? Why can’t Both be an answer? — Mark Dennis

That's kind of a logic joke. "P or Q" is true if either P is true, or Q is true, or P and Q are both true, so if someone asks you "P or Q?" and at least one (or more) of them is true, "yes" is a valid answer. So that's where "both" fits. "No" is, likewise, "neither".

Now some say pragmatism "bridges the gap" between the analytic and continental traditions, whatever that may mean — Ciceronianus the White

I've found that seeming true myself, though there is a lot of variation within pragmatism so it's kinda hard to pin down. Some neopragmatists can get awfully relativistic, but I wholeheartedly embrace a form of pragmatism myself that, like Banno said above, basically uses Analytic-like means to pursue Continental-like ends, being very dry, practical, and precise, by asking what exactly are we trying to do here and why, what use would an answer to this philosophical question be in actually living our lives, as a manner of clarifying what exactly we're even asking and how to go about answering it. Pragmatism kind of evolved outside of the Continental-Analytic schism itself, principally in America so in the shadow (and so influence) of Analytic philosophy's dominance of the Anglophone world, but still apart from it, and so sharing more concern for things the Analytics cast aside as nonsense and the Continentals continued to pursue. -

What It Is Like To Experience XI don't understand why is a reply to me? Doesn't seem to have anything to do with anything I was talking about.

Pfhorrest

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum