-

Why is there Something Instead of Nothing?If the question is why the empty world is not the actual world, then the question IS why we are not in it, at least to a modal realist like me, to whom “the actual world” means “the world we are in” and nothing more.

-

Do Atheists hope there is no God?It depends on what exactly you mean by God. It would be awesome if an all-knowing, all-powerful, all-good being existed, because then nothing bad would ever happen. Except bad things do happen, so...

It’d be great if there was even a very knowledge, very powerful, very good being, since then much less bad would happen. The latter is at least something that someday could exist: we could make and/or become such a being ourselves, or someone somewhere else could and then we could benefit from it too.

It would also be nice if what we think is reality isn’t actually the whole of reality and there exists some being beyond it who for some reason can’t make everything in here perfect for everyone (to explaining why it’s not) but can eventually rescue everyone from here (even those who’ve already died) and put them somewhere that it can make perfect for all of us. But now we’re into really far-fetched wishful thinking, basically hoping that we are in some aliens’ simulation and that very specific circumstances in our favor pertain in the aliens’ world. -

The objects of morality: "teleology" as “moral ontology”Rather than distinguishing between what ‘is’ and what ‘ought to be’, recognize with Putnam, Rorty and others the inseparability of fact and value, description and prescription — Joshs

I recognize that there is a descriptive and prescriptive facet to everything, and that they are abstractions from a single experiential-behavioral process; that to non-sentient beings, every experience is simultaneously informative and motivational and directly leads to a subsequent behavior. But it is precisely the ability to differentiate those aspects, setting aside some kinds of experiences as merely informative, some as merely motivational, then reflecting on both of the models thereby generated, before then combining those "is" and "ought" thoughts (beliefs and intentions) together to drive behavior, that constitutes sentience (and sapience) itself. (As discussed in my thread on philosophy of mind).

Recognize that affectivity( the hedonic) is not separable from rationality but forms the core of intentional meaning. — Joshs

I'm not making a distinction between the hedonic and the rational, except to the same degree as the empirical and the rational; empiricism and hedonism are both about experiences (distinguished by direction of fit), while rationality is a structure of thinking about both, where everything we think is about those experiences. It's all one multidimensional continuum, but analyzing the different dimensions and directions in that continuum is what philosophy is for.

NB from the preceding thread:

In general, I view the correct approach to prescriptive questions about morality and justice to be completely analogous to, but also entirely separate from, the correct approach to descriptive questions about reality and knowledge. This is different from views that hold that one set of questions reduces entirely to the other set of questions, like both scientism (which reduces prescriptive questions to descriptive ones) and constructivism (which reduces descriptive questions to prescriptive ones).

But it is also different from views such as the "non-overlapping magisteria" proposed by Stephen Jay Gould, who held that questions about reality are the domain of science, with its methodologies, while questions about morality were entirely separate in the domain of religion, with its wholly different methodologies.

I hold, like Gould, that they are entirely separate questions, but that perfectly analogous, broadly-speaking scientific, methodologies can be applied to each, and that religious methodologies have historically been (wrongly) applied to both of them as well. This is largely because of my views that prescriptive assertions and opinions are generally analogous in every way to descriptive assertions and opinions, differing only in a quality called "direction of fit". — Pfhorrest

More on that direction-of-fit basis in my earlier thread about metaethics and philosophy of language.

Understand that both subjectivity and objectivity are constructed through intersubjective processes. Instead of the computer-based metaphor of the subjective agent receiving inputs from objective sense data and transforming this into behavioral output, see the organism-environment relation as a single system of of mutual transformation. — Joshs

In my ontology (already linked in the OP) I do explicitly acknowledge that already. All objects are subjects, all subjects are all objects, every experience is of something else's behavior, and every behavior constitutes something else's experience, experience and behavior being different perspectives on the same thing, an interaction. That's why in the diagram in the OP, the two things represented by circles are labelled "object role" and "subject role", to show that the interaction is a behavior of the thing considered as an object, and an experience from the perspective of the thing considered as a subject, and it's which role they're being considered in (which perspective we're taking) that determines which end of the interaction is experiential and which is behavioral.

But again, it's analyzing the different facets of these compound things that gives us greater insight into them. We could just de-analyze everything to "stuff happening" in the extreme other direction, but it's the distinctions that make for a philosophical examination. -

Why is there Something Instead of Nothing?Hence the question in the OP might become "Why is the empty possible world not the actual world?"

And the answer is, it just isn't. — Banno

From a modal realist perspective like mine, "actual" is indexical, so that question in turn becomes "why aren't we in the empty possibly world?" The answer to which, of course, is that any world that we are in is by definition not empty; we can only find ourselves in a world that contains at least ourselves.

We might then ask why there is anything besides ourselves in this world, and the answer to that would concern the prevalence of possible worlds that just contain (basically) a Boltzmann Brain compared to worlds containing complex cosmological and evolutionary processes that give rise to brains in the way we suppose ours were created. Which pretty much reduces this problem to the Boltzmann brain problem. -

What if....(Many worlds)I like this, and it reminds me of my own take on many things. In philosophy of time I'm sort of both a presentist and an eternalist, in different senses. On ontology more generally I stand by both the positions that all there is nothing to reality but empirically observable stuff and that all of reality is itself an abstract mathematical object. And yeah, regarding quantum mechanical observations, I can see a Copenhagen interpretation or an Everett interpretation as equally valid, depending on perspective. In all of these issues I've listed here, the main difference is between a first-person perspective and a third-person perspective on the same thing.

I've heard the Sanskrit term "advaita" (nondualism) and am often tempted to use it to describe this type of thinking, but TBH I'm not confident enough in my knowledge of that area's philosophy to be sure I'd be using it right. (I'm at least familiar with the notion of "Atman is Brahman", and the veil of maya creating an illusory distinction between them, and while I don't think I agree with the usual interpretation of that, the diagram of the relationship between them that comes to me mind does remind me of a diagram I've often pictured of my own philosophy: the surface of a mirror, against which the eye of an invisible observer is pressed, and everything happening at that boundary between eye and mirror is all of phenomenal reality; the invisible observer abstracts things from those phenomena in his mind, behind his eye, but because of the mirror, he sees those things projected behind the phenomena instead; and infinitely far back into the mind recedes, forever inaccessible, the notion of some true self, which is then mirrored as and projected infinitely far into the distance as the notion of some kind of supreme being behind all of reality. If the structural similarities aren't clear: the phenomena on the surface of the eye/mirror boundary are maya, the true self imagined infinitely far back into the mind is Atman, and the supreme being imagined infinitely far behind the mirror is Brahman, which is just a reflection of Atman, which itself is just imaginary). -

Why is there Something Instead of Nothing?There is no possible world at which there is no world, therefore the existence of something is logically necessary.

-

The objects of morality: "teleology" as “moral ontology”I wouldn’t call myself “dualist” in the usual ontological sense: I am a strong monist (physicalist phenomenalist) about ontology. I’m not proposing the existence of nonphysical beings or substances or properties here, but rather drawings attention to the prescriptive equivalents of such descriptive ontological things.

What sense of “dualism” do you mean, and what are the blind spots you speak of? I strongly suspect that they are not applicable to what I mean here, as this is not at all a traditional model; at least, I never learned of anything like it in the course of my philosophy degree. -

The principles of commensurablismGlancing back at this thread nine months later, I realize that because the original function of it (that got shunted into a different thread) got derailed into talking about this subject earlier than expected, and then this subject got derailed by completely focusing on one tiny aspect of these more general principles, I never actually posted the proper thread on this subject that I meant to way back then, including especially the reasons for holding these principles. So, here is that now. (NB that I've also updated the terminology in the OP and in this post to reflect changes in my usage since 9mo ago).

----

The underlying reason I hold this general philosophical view, or rather my reason for rejecting the views opposite of it, is my metaphilosophy of analytic pragmatism, taking a practical approach to philosophy and how best to accomplish the task it is aiming to do.

This view, commensurablism, is just the conjunction of criticism and universalism, which are in turn just the negations of dogmatism and relativism, respectively. If you accept dogmatism rather than criticism, then if your opinions should happen to be the wrong ones, you will never find out, because you never question them, and you will remain wrong forever. And if you accept relativism rather than universalism, then if there is such a thing as the right opinion after all, you will never find it, because you never even attempt to answer what it might be, and you will remain wrong forever.

There might not be such a thing as a correct opinion, and if there is, we might not be able to find it. But if we're starting from such a place of complete ignorance that we're not even sure about that – where we don't know what there is to know, or how to know it, or if we can know it at all, or if there is even anything at all to be known – and we want to figure out what the correct opinions are in case such a thing should turn out to be possible, then the safest bet, pragmatically speaking, is to proceed under the assumption that there are such things, and that we can find them, and then try. Maybe ultimately in vain, but that's better than failing just because we never tried in the first place.

This line of argument bears similarities to Blaise Pascal's "Wager", or pragmatic argument for believing in God. In the Wager, Pascal argues that if we cannot know whether or not God exists, we nevertheless cannot help but act on a tacit opinion one way or another, by either worshipping him or not. This results in four possible outcomes:

- either we believe in God, and he doesn't exist, and we lose a little in the wasted effort of worship;

- or we disbelieve in God, and he doesn't exist, and we save what little effort we would have spent in worship;

- or we believe in God, and he does exist, and we reap the infinite reward that is heaven;

- or we disbelieve in God, and he does exist, and we suffer the infinite loss that is hell.

Pascal argues that it is thus the practically safest bet to believe in God, whether or not he turns out to actually exist. My pragmatic argument for commensurablism bears a formal similarity to that, in that I am also arguing that if we cannot know whether there are answers to our questions to be found, we nevertheless cannot help but act on a tacit opinion one way or another, by either trying to find them or not, resulting again in four possible outcomes:

- either we try to find the answers, and there are none, and we lose a little in the wasted effort of investigation;

- or we don't try to find the answers, and there are none, and we save what little effort we would have spent in investigation;

- or we try to find the answers, and there are some, and we reap the unknown but possibly immense reward that is having them;

- or we don't try to find the answers, and there are some, and we suffer the unknown but possibly immense loss that is never having them.

The important key difference between Pascal's Wager and mine is that Pascal urges us to "bet" on one specific possibility, when there are many different possibilities with similar odds – different religions to choose from, different supposed Gods to worship and ways to worship them – leaving one forced to choose blindly which of those many options to bet on, and necessarily taking the worse option on all the other bets. Whereas I am only urging one to "bet" at all, to try something, anything, many different things, and at least see if any of them pan out, rather than just trying nothing and guaranteeing failure.

To analogize the respective "wagers" to literal wagers on a horse race: Pascal is urging us to bet on a specific horse winning, rather than losing, while I am only urging us to bet on there being a bet at all, rather than not. If there is no bet, then we cannot lose the non-existent bet by betting in that non-existent bet that there will be a bet, even though we still might not win either, if there is indeed no bet to win.

I would argue that to do otherwise than to try (even if ultimately in vain) to find answers to our questions, to fall prey to either relativism or dogmatism, to deny that there are such things as right or wrong opinions about either reality or morality, or to deny that we are able to figure out which is which, is actually not even philosophy at all.

The Greek root of the word "philosophy" means "the love of wisdom", but I would argue that any approach substantially different from what I have laid out here as commensurablism would be better called "phobosophy", meaning "the fear of wisdom". For rather than seeking after wisdom, seeking after the ability to discern true from false or good from bad, it avoids it, by saying either that it is unobtainable, as the relativism does, or that it is unneeded, as the dogmatist does.

Commensurablism could thus be said to be necessitated merely by being practical about the very task that defines philosophy itself. If you're trying to do philosophy at all, to pursue wisdom, the ability to sort out the true from the false and the good from the bad, you end up having to adopt commensurablism, or else just give up on the attempt completely, dismissing it as either hopeless or useless.

As Henri Poincaré rightly said, "To doubt everything or to believe everything are two equally convenient solutions; both dispense with the necessity of reflection." (La Science et l'Hypothèse, 1901). Or as Alfred Korzybski similarly said, "There are two ways to slide easily through life: to believe everything or to doubt everything; both ways save us from thinking."

To further elaborate on the worldview entailed by this general philosophy:

I hold that there are two big mutually exclusive and jointly exhaustive questions, neither of which is reducible to the other, and between the two of which all other smaller questions are covered. One is the descriptive question of what is real, or true, or factual. The other is the prescriptive question of what is moral, or good, or normative.

There are many more concrete questions that are each in effect a small part of one of these questions, such as questions about whether some particular thing is real, or whether some particular thing is moral, that are the domains of more specialized fields of inquiry. And there are also more abstract questions about what it means to be real or to be moral, what criteria we use to assess whether something deserves such a label, what methods we use to apply those criteria, what faculties we need to enact those methods, who is to exercise those faculties, and why any of it matters. But in the middle of it all are those two big questions, in service of which all the other questions are asked: "What is real?" and "What is moral?"

I hold that in answering either question, it is completely irrelevant who thinks what is the answer, or how many people think what is the answer. All that matters is whether there are any reasons at hand to prefer one answer over another. In absence of any reasons, any proposed answer might be right, no matter who or how many people agree or disagree. But no matter how many reasons to prefer one answer over another, that preferred answer still always might be wrong, no matter who or how many people agree or disagree: the reasons to discard it may merely not be at hand just yet.

All of inquiry, on either factual or normative matters, is an unending process of trying to filter out opinions that we have reasons to think are the wrong ones, and to come up with new ones that still might be the right ones. But no matter your current best answer to either question, there is always some degree of uncertainty: you might be right, but you might be wrong. All we can do is narrow in further and further on less and less wrong answers.

In a way this is somewhat comparable to the "spiral-shaped" progress described by philosophers such as Johanne Fichte and Georg Hegel. Imagine an abstract space of possible answers, with the correct answers lying most likely somewhere around the middle of that space. Our investigations whittle away further and further at all opposite extremes, theses and their antitheses, and then again at the remaining extremes of the resulting syntheses, again and again, indefinitely. The center of the area remaining after each step will consequently wander around the original complete space of possibilities in a manner that gradually "spirals", roughly speaking, closer and closer to wherever the correct answer is in that space.

Fichte and Hegel's "spiral-shaped progress" of theses, antitheses, and syntheses is, I think, a bit too much an idealization of this process, but it is at least in the right general direction relative to its predecessors, in a way that is itself an illustration of this very process:

Eliminating first the extremes, the thesis and antitheses, of viewing worldviews either as constant and static, or as progressing linearly in a given direction, a first approximation at a synthesis could be the notion of circular change, alternating between opposites in a constant pattern. Hegel's notion of spiral progress is a further refinement upon that, a synthesis between linear progress and circular change, a view of alternating between opposites but narrowing in constantly toward some limit.

My view is a refinement further still, which can perhaps be framed as the synthesis of Hegel's view, and the view that there is no pattern at all to change, just random or at least chaotic, unpredictable change. In my view the changes of worldview are largely unpredictable and unstructured, but by constantly weeding out the untenable extremes, the chaotic swinging between ever-less-extreme opposites still tends generally toward some limit over time.

Commensurablism is itself explicitly such a synthesis of opposing views. As described already in the introduction, the history of philosophy is itself a series of diverging theses and antitheses punctuated by unifying syntheses, and I aim to position this philosophy as a synthesis of the contemporary pair of thesis and antithesis in that series, Analytic and Continental philosophy.

It is furthermore a synthesis of two opposing trends in general public thought that I observe in my contemporary culture, that very loosely track affinity to those professional philosophical schools. One of them places utmost emphasis on the physical sciences and the elite academic authorities thereof, largely denying the universality of morality entirety. The other places their utmost emphasis on the ethical and political authority of the general populace, while largely denying the universality of reality entirely.

But each of the faults of each of those trends of thought stem ultimately from haphazardly falling one way or another into one of the two worldviews that commensurablism is most truly a synthesis of: fideist objectivism and skeptical subjectivism. I aim to adapt and shore up the strengths of each of those opposing views, while rejecting those parts of each against which the other has sound arguments, resulting in this new view that retains the best of both and the worst of neither, being critical yet universalist about both reality and morality. -

What is the wind *made* from?It would be quite a lot of typing to state everything I know about quantum field theory. Do you have a more specific question, or want a broad overview of it?

-

What is the wind *made* from?I don't know what you mean by "follower", but I know about the theory, yes.

-

What are we doing? Is/ought divide.I think it's reasonable to think there is far more agreement in regards to what is perceived via the senses than there is in regard to all but the most extreme moral questions (i.e. rape, murder, child abuse etc). — Janus

The degree of agreement isn’t important if you’re not taking a majoritarian vote (which I’m not advocating) but rather taking every individual into equal account. And also you don’t seem to be differentiating between moral opinions (“this state of affairs is morally good”) and the experiences I’m advocating we take as the grounds for forming moral opinions (“this experience feels good”); it’s the latter we’re talking about here.

I'm basically advocating that we take as the criterion for a state of affairs to be moral without qualification that in said state of affairs everyone feels good rather than bad, like science takes reality to be that which is consistent with all observations. A right or just action is then one that at least preserves the present degree of goodness thus defined, if not increases it; in the same way that valid epistemological inferences are truth-preserving.

Then within that framework, we investigate what in particular actually is good or right in that sense. At no point do we take someone merely thinking that something in particular is good as a reason to think it actually is, just like in the physical sciences we don't care who thinks what is true. All that matters in the physical sciences is the observations and the validity of inferences about them, not what people believe is real; and likewise in an ethical science all that mattered would be the actual experiences people have, and the justification of actions regarding them, not what anybody merely thinks is moral.

I think ethical questions (how best to live) are far more subtle, and not at all simply based on considerations of seeking pleasure and avoiding pain. I can see you're trying hard to recast the usual account into a form that will pass through your lens, but I don't find it convincing at all. — Janus

The point is just that we could do something like science with regard to moral questions if we wanted to. You’re saying here basically that you don’t want to. I’m already arguing why we should in other threads right now so I won’t do that here as well, my only point here is that we could: we could take morality to be all about hedonic experiences and compile and sort through all such experiences in the same way science takes reality to be all about empirical experiences and compiles and sorts through them.

There is no "ordinary philosophical way going back thousands of years". This is naive, have you never heard of hermeneutics or anachronism? It's all a matter of interpretation. We read translated texts that inevitable reflect, to greater or lesser degrees, the biases of modern translators. It is naive to think we can get inside the heads of the ancients. — Janus

I’m using it the way defined by modern philosophy encyclopedias and consistent with the views espoused in modern translations of ancient texts that also labeled themselves thus. Which is not the way is has crept into modern colloquial speech, but that’s the fault of common folks misunderstanding, not philosophers making stuff up. -

What is the wind *made* from?Beans. — Banno

And broccoli, and... I remember there were two others in an old joke about the "four winds", but I can't find that joke on Google to refresh my memory. -

Guest Speaker: David Pearce - Member Discussion ThreadOn the farm, humans minimise the suffering of animals they slaughter for food — counterpunch

Have you seen factory farm conditions?

The conditions of nature are pretty awful too, but tell me which you would prefer for yourself:

- being a prehistoric human in the untamed wilderness with all the risks that modern civilization has since mitigated, or

- being born and raised your whole life in a cage too small for you move, which gets stacked with a bunch of similar cages in a dark warehouse where you'll never see the sun, such that the piss and shit from the people in cages above you just rains down on you, but you're pumped full of antibiotics (on top of a diet of nothing but corn syrup to fatten you up cheaply) to make sure that you're likely enough to at least survive uninfected until adulthood so that you can be slaughtered and consumed safely enough (for the safety of the people consuming your body) that the people operating the warehouse full of you shit-covered cage-people can turn a profit.

The first option isn't great, especially compared to my life, but I'd pick that over the second option any day. -

Psycho-philosophy of whingingAll of humanity's problems stem from man's inability to sit quietly in a room alone — Pascal

This reminds me of something I just said in another thread yesterday:

"allows a person to enjoy themselves without a minimum threshold of stimulation that constantly needs to be maintained or increased." — Shawn

I’ve always been the kind of person who never gets bored, because my own mind is full of my own interesting thoughts to entertain me. I’ve also pretty much never even been tempted to do recreational drugs. Most all of my suffering in life has come from negative stimuli, not any absence of positive stimuli.

Most of 2019, I found myself suddenly and inexplicably struck with existential dread the likes of which I had never experienced before. It was only then that I understood what people talked about when they searched for a “meaning of life”. To me that had always seemed like a non-question, but suddenly I understood it, the feeling like there's some bottomless hole in one's soul that needs to be constantly filled by... something. From my perspective, it seemed the usual hedonic order had been flipped around: instead of feeling fine by default as long as nothing awful was happening, I felt awful by default unless some positive stimulus pushed me out of it, temporarily filled that hole inside of me, the hole that had never been there for my entire life before.

The thought that for a lot of people that empty feeling, the worst thing I’ve ever experienced in my life, is their normal, is terrible, and I’d love if something could be done to alleviate it for them.

I’ve also thought before that introversion and extroversion might be related to this, since from my introverted perspective, it seems to me like introverts are people who neither need to dump their excess emotions on others nor charge up on others’ emotions, maintaining emotional homeostasis alone, whereas extroverts need other people to give or take stimulation from them in order to achieve emotional balance. — Pfhorrest -

A poll on hedonism as an ethical principleAnd in the process of doing so, the person gets designated as "abnormal". "Wrong". "Defective". "Inferior". — baker

No, that's quite the opposite. Consider for example recognizing neurodiversity, as in, the non-defectiveness of autistic (etc) experience patterns. Things that please and calm many neurotypical people can be very distressing and displeasing to neurodivergent people. The position you assumed I was arguing would be to call whatever pleases "normal" (neurotypical) people good, and neurodivergent people defective for not finding that good. But what I'm actually advocating is that we say it's good to act one way toward a neurotypical person (the way that they find pleasant and calming), but bad to act that same way toward a neurodivergent person (because they'll find it distressing and displeasing).

Just like a theory of color that makes predictions hinging on "normal" three-color vision needs to make that dependency explicit or else it will end up making false predictions from the perspective of colorblind people. A truly universal theory of color vision will have to make predictions that "normal" people will see one type of thing and colorblind people will see a different type of thing. -

What is the wind *made* from?is wind similar to waves in the ocean (the water rising and falling to get out of the way of passing energy), and that neither of them exist — The Opposite

When you really get down to the physical bottom of things, everything is like waves in the ocean, patterns of energy density propagating through media (the media at the bottom here being quantum fields, and all other media being themselves already patterns in those fields).

So if wind and waves don't exist, then by extension nothing exists.

But things exist, thus so does wind. -

Dissolving normative ethics into meta-ethics and ethical sciencesPeople's views on reality are equally difficult to change. Many people simply aren't going to engage in a full examination of evidence and argumentation to change their views on something like cosmology, evolution, race, sex, gender, medicine, epidemiology, climate, etc -- just to list some notable contentious issues where the physical sciences are ineffectual at shaping public opinion. Many people come to believe what they believe about those things via a complex set of mostly non-rational causes.

But that doesn't matter, because some people will engage in that thorough examination, and those people are the scientists. They're still not perfect, they've still got their flaws, they're still human, but at least there's an organized effort of some people out there trying to study reality the rational way, and to let everybody else know what the results of those studies are. And the existence of that social institution then influences the beliefs of the public at large through the non-rational means by which they come to their beliefs.

To put the ethical analogue of that in Kohlberg terms, I'm presuming that I'm talking here to people in the second postconventional stage of moral development, people who are driven in their moral thinking by universal ethical principles, and we're here discussing what those universal ethical principles are. We're supposed to be doing philosophy here, after all. That most people won't get on board with that because they're morally underdeveloped is no more an argument against the principles in question than many people's irrational belief-formation processes are an argument against the principles that underlie the physical sciences. -

A poll on hedonism as an ethical principleI think what is supposed to become clear through Buddhism is not necessarily the subject of experience per se, but an understanding about, or insight into, the nature of experience, generally. — Wayfarer

That would still not be transcendental in the sense I mean then, because it's not an a posteriori claim about actual particulars of either reality or morality ("this kind of thing exists", "this kind of thing is good", etc) at all, but an a priori claim about the philosophical matters of how to even answer questions about those things (the nature of experience being one factor of that topic).

These two experiences seperately do not tell us anything. We need another element, which I argue is reason, to connect the dots. — Tzeentch

Sure, but I'm not arguing that we don't need to rely on reason, only that we do need to rely on experience. Reason alone gets us nowhere, it just stops us from heading down dead ends. To make actual progress in figuring out any of the particulars, we have to rely on experience as well. -

David Pearce on Hedonism.It's interesting to note that many people need peak experiences in life to endow it with meaning. Drugs like hallucinogens or cannabis can alleviate these feelings of lack of meaning in life sometimes. — Shawn

Yeah, even though I'd never experienced existential dread until 2019, I had had plenty of peak experiences here and there throughout my life, all naturally without drugs or anything, and while I really enjoyed them, I never found them like, religiously significant or anything. I did find them very useful: I could be very productive and come up with a lot of really good creative thoughts while having such feelings. Interestingly, friends I know who have done drugs like that and attained peak experiences that way would sometimes tell me that I sounded like someone who had just come back from a "really good trip" when I described the ideas I'd come up with. -

David Pearce on Hedonism.I didn’t read this thread before, but came here from your suggested David Pearce interview thread, and along with completely agreeing with that Hedonic Initiative you linked, this quoted bit really stands out to me:

allows a person to enjoy themselves without a minimum threshold of stimulation that constantly needs to be maintained or increased. — Shawn

I’ve always been the kind of person who never gets bored, because my own mind is full of my own interesting thoughts to entertain me. I’ve also pretty much never even been tempted to do recreational drugs. Most all of my suffering in life has come from negative stimuli, not any absence of positive stimuli.

Most of 2019, I found myself suddenly and inexplicably struck with existential dread the likes of which I had never experienced before. It was only then that I understood what people talked about when they searched for a “meaning of life”. To me that had always seemed like a non-question, but suddenly I understood it, the feeling like there's some bottomless hole in one's soul that needs to be constantly filled by... something. From my perspective, it seemed the usual hedonic order had been flipped around: instead of feeling fine by default as long as nothing awful was happening, I felt awful by default unless some positive stimulus pushed me out of it, temporarily filled that hole inside of me, the hole that had never been there for my entire life before.

The thought that for a lot of people that empty feeling, the worst thing I’ve ever experienced in my life, is their normal, is terrible, and I’d love if something could be done to alleviate it for them.

I’ve also thought before that introversion and extroversion might be related to this, since from my introverted perspective, it seems to me like introverts are people who neither need to dump their excess emotions on others nor charge up on others’ emotions, maintaining emotional homeostasis alone, whereas extroverts need other people to give or take stimulation from them in order to achieve emotional balance. -

A poll on hedonism as an ethical principlewe're not outside of or apart from the object of enquiry, 'we are what we seek to know.' — Wayfarer

I’d say that is as true of reality as it is of morality, precisely because of phenomenalism about reality, empirical realism, like Kant’s. All we can know about is how things appear to us, so we are a part of the object of enquiry there too. Likewise, all we can know about morality is what does or doesn’t feel good to us — all of us, not just one of us, just like in empirical investigations of reality.

In Buddhist ethical theory, the aspirant is presumed to be able to validate the teachings by first-hand insight, through their attaining of that insight in the living of the principles. The key term is 'ehi-passiko', 'seeing for oneself'. In practice there are obstacles to that, first and foremost the difficulties of realising such goals, but you can't say that in principle nobody it able to do so. — Wayfarer

That would not be transcendentalism in the sense I mean then, since if you can experience it for yourself it is definitionally phenomenal. -

A poll on hedonism as an ethical principleAnd we've talked about how these experiences alone are too easy to fool to serve as a guide. — Tzeentch

But we're asking how we know that they are so unreliable. Your answer was "reason". I responded that reason alone can't get you much of anywhere, you need something to reason from to begin with, and I asked "where do you get that, besides experience (or else taking someone's word for it)?". Assuming we agree that taking someone's word for it is no good, that leaves us appealing to experience to tell us that experience is unreliable.

Which works if what we mean is that further experiences can tell us that some limited earlier experiences were not the full picture; I agree with that completely. But in that case you're still relying on experience generally. And if you can't rely on experience generally because experience tells you so... that's circular there.

But one cannot replicate others' experiences.

For example, I don't drink coffee, because it makes me sleepy. Many people drink coffee in the morning specifically for the purpose that it "wakes them up". So which is it? Who is right, who is wrong? Who has the right experience of drinking coffee in the morning? I or they? Is there an objectively right way to experience drinking coffee in the morning? — baker

Observations always only tell you a relationship between observers and the world; the predictions based on those observations are that certain types of observers will or won’t observe certain things. It is those relationships that can be objective (as in universal), not just the object-end of them.

E.g. even how things look or sound etc are not the same between every observer. There are different kinds of colorblindness, actual blindness in different degrees, tetrachromaticity, different degrees of hearing sensitivity or deafness to different pitches of sound, people who can or can’t smell or taste various things or to whom they smell or taste different, etc.

An ethical science would likewise have features of subjects of experience baked into both its input and its output.

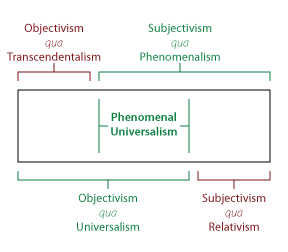

Objectivisms are authoritarian — baker

Transcendentalisms are, yes, because they demand that you take someone's word for it, because nobody can check the results for themselves. But universalism is not necessarily transcendentalism, just as phenomenalism (non-transcendentalism) is not necessarily relativism (non-universalism).

But it still comes down to whose observation matters. — baker

On a universalist account, everyone's observation matters; that's what makes it universalist.

Physical science is universalist about reality in that if someone doesn't experience the same phenomena that everyone else does, even after completely controlling for the objects of said experience (the environment / experiment / etc), we go figure out what's different about the subject (the person) such that they experience the same object differently, and adjust our theories to correctly predict what that kind of subject will experience as well. An ethical science would have to do likewise. -

Dissolving normative ethics into meta-ethics and ethical sciencesIn order to change things, you need to start with how they actually are. — baker

Right, which is why we need the descriptive, natural, physical sciences. But we're talking about prescriptive, moral, ethical matters here. If you say there's nothing to the latter the former then you're implying change is impossible; or at least, refusing to speak about change.

It's like if I say "we need to get to location A" and you say "we are not at location A, we are at location B". Okay, sure... is that supposed to disagree with me? I'm not claiming anything about where we are, but about where we should go. Are you saying that we can't go anywhere other than where we already are? Or are you just saying nothing at all about where we should go? -

A poll on hedonism as an ethical principleOk, but how does this make a case for hedonism? — Tzeentch

Hedonism (specifically ethical hedonism, the topic of the thread) is about appealing to experiences (of things feeling good or bad) as grounds to call something good or bad.

Hopefully I don't need to make the obvious case against just taking someone's word for it. -

A poll on hedonism as an ethical principleBut your moral objectivism amounts to the same thing. — baker

It very explicitly does not. That's the point of replicating others' experiences: so we don't have to take their word for it.

You never explained your bizarre "empathy is incompatible with objectivism" comment, but I'd guess from that that you take "objectivism" to mean what I called "transcendentalism", which would require taking someone's word for it, which is why I'm against that, as I explicitly said. The only sense of "objectivism" I support is "universalism", the view that something being good or bad doesn't depend on what anyone thinks or says... because that would just be taking someone's word for it too.

Just like (according to a scientific worldview) reality doesn't depend on what anyone thinks about it, but there's still nothing about reality that's beyond observation: it's not relative, it's universal, but it's also not transcendent, it's entirely phenomenal.

we can use reasoning alone to come to conclusions about what is good and bad — Tzeentch

Only when we already have some known-true propositions about what's good or bad to reason from. But when we're starting from scratch, or are lost in radical doubt, where do we get any such moral propositions to start that reasoning process from? I can think of nothing other than experience, or else just taking someone's word for it. -

Dissolving normative ethics into meta-ethics and ethical sciencesI read your brief critique of Sam Harris' wellbeing frame and it seems like you are wanting to redirect this with additional analytic mechanisms - maybe I have that wrong. — Tom Storm

My critique of Harris is really only a critique of his dismissal of other things. The things he actually advocates for rather than against all sound generally good to me: use science to figure out what things contribute to peoples' well-being. My difference from him is that he relies entirely on empirical observation of people in the third person to figure out what constitutes their well-being in the first place, whereas I advocate using repeatable first-person hedonic experiences to confirm what it's like for them to be well; and also that he basically says "stop doing philosophy, just define this factual state of affairs as 'good' and get on with it", but I think that it can be philosophically justified that such states of affairs are good in a way that escapes the problems of the implicit ethical naturalism he espouses. -

Dissolving normative ethics into meta-ethics and ethical sciences"It's not that way" doesn't mean "it can't be that way".

The entire point of moral theory is figuring out how to change things. If they can't be other than they already are, there's no point. -

A poll on hedonism as an ethical principleI think such experiences and reasoning can tell us many things that are both true and good for ourselves. — Tzeentch

Reasoning PLUS experience can, sure, but you were just doubting the reliability of experience, and when pressed for what grounds we have to doubt it, gave just reasoning alone as an answer.

My point overall is that while the conclusions reached from some experiences can indeed turn out to be wrong, the way we find that out is via more experiences, so it’s still ultimately experience that we’re relying on.

I didn't invoke the existence of a "super perfectly ethical person" - and I could not answer your question for such a person, if I had! — counterpunch

there's no-one who would like to answer "1. Everyone's is relevant" more that I would, but I can't — counterpunch

This second bit here is why I mentioned the super-person the first bit is about. It sounds to me like you’re saying that if you were a better person, you would care about everyone more than you in fact do; thus, that your idea of what a good person would answer is 1.

I bring that up because what I’m asking about is what you think the morally correct answer is, not just what you’re personally emotionally motivated to act on. Like, if you could be a better person, however you conceive “better” to be, what do you conceive that that better you would care about? And it sounds like you conceive that it would be 1. -

Dissolving normative ethics into meta-ethics and ethical sciencesYour own moral philosophy now sounds more like a form of ethical rationalism than ethical naturalism, since you're not appealing to empirical facts but to abstract practical reason, so that escapes most of the criticism I had for what I thought you thought.

science is not in the WHY (this rather than that) business — 180 Proof

You're completely correct that the descriptive, natural, physical sciences, like we have today, are not. Which is why I am as adamantly as you seem to be against using them to answer prescriptive, moral, ethical questions. It really seems like you think I'm advocating something I'm not, and that you're arguing against the same thing I myself am adamantly against.

If you like, read every instance where I've said "ethical science" as "ethical analogue of science" instead, if in your mind "science" has to mean the descriptive, natural, physical investigations into reality that we have today. I used to say "ethical analogue of science" myself, so that's fine.

This is why moral philosophy, which is in the WHY business, can't be replaced by an "ethical science" – it can't even answer WHY it is "good, and better than" moral philosophy – because science is N O T self-reflexive, or reflective, in the way philosophy is inherently. The philosopher herself is always subsumed by doing philosophy, that is, by implicitly asking WHY do philosophy? with every philosophical inquiry & dialectic. — 180 Proof

Yes, which is why I'm not saying we should do away with moral philosophy, and why I say that applied ethics (either as we have it today, or transformed as I'm advocating) is not properly a branch of philosophy.

The philosophical questions about morality are about finding the best way to answer our questions about what in particular is the right thing to do in a particular situation. Actually answering those particular questions is beyond the scope of philosophy. What I'm advocating here is that philosophy focus entirely (in its ethical endeavors) on answering those kinds of questions, the general and fundamental kinds of questions about how to tell what is or isn't good, what it even means for something to be good, etc. Moral epistemology, moral ontology, moral semantics, etc.

And then that the answers that philosophy gives to those question then be taken and extensively and systemically applied to answer the particular questions, the "applied ethics" questions. That extensive application of philosophical principles to coming up with systemic strategies for doing good in the real world is all I mean by "ethical (analogue of) science" here. -

A poll on hedonism as an ethical principleSensory experiences combined with our reasoning faculty, where the latter can provide us with an understanding the sensory experiences cannot. — Tzeentch

About what, how? So far as I can see, a priori reasoning can only tell us when things are logically impossible because they're contradictory incoherent nonsense. That's useful, sure, but it doesn't get you very far; it can't tell you any contingent things about either what's true or what's good, only about what's (not) possible.

it has been stated already* that this activity is the activity of contemplation — Nichomachean Ethics

On what grounds can we judge whether or not that claim (that contemplation is the highest virtue) is correct? In virtue of what (pun intended) is contemplation the highest virtue? i.e. what makes contemplation so good? -

Dissolving normative ethics into meta-ethics and ethical sciencesIf that's what you gather from my postings all these months, all I can say is you've profoundly misread me. Please show where I've proposed "innate" or "a priori" assumptions — 180 Proof

I could have sworn there was something right in this thread to that effect, to the effect that we already know what the goods we're aiming to achieve are and only need to study how to achieve them, but now I can't find it, so maybe I confused you and someone else here. But...

No humean "Ought from Is" problem on my part, Pfhorrest – unless, for you, ethical naturalism & hypothetical imperatives rest on an "Ought from Is" fallacy — 180 Proof

Ethical naturalism absolutely conflates "is" with "ought"; that's the whole point of the naturalistic fallacy.

Hypothetical imperatives don't, because they use "ought"s in their antecedents: "if you ought to do X then you ought to do Y", which can hinge on a purely logical relationship between X and Y without concern for the "ought"ness of either; but then you're still left with the question "ought I do X?" unanswered.

analogues – not scientistic replacements – for reasoning about ethics. And I'm also diametrically opposed to attempts like Harris' and yours to supplant moral philosophy with an "ethical science". — 180 Proof

I am myself diametrically opposed to scientism and for that reason also to (the foundational assumptions of) Harris' program. I'm not saying "just do (natural) science, that will tell you what's good!" -- I'm completely opposed to that. I'm saying "let's build moral philosophy up the same way that natural philosophy got built up -- just like that got turned into natural science, let's turn moral philosophy into moral science".

The moral or ethical science I propose it not a kind of natural or physical science, but a completely separate analogue to them. My first objection to you in this thread was that you were putting forth some things that are descriptive (natural, physical) sciences, that give "how does" answers, as though they were prescriptive (moral, ethical) fields that gave "why should" answers; my proposal in contrast is to have completely separate analogous prescriptive investigations, that supplement the descriptive ones we already have.

None of that means that philosophy no longer has anything to say on the subject of morality: it means that philosophy's place becomes securing the groundwork for such a project, the same way that philosophy today isn't about wondering out loud whether things are all made of water or of fire, but about securing the groundwork for doing an actual rigorous investigation into questions like that.

I don't want to supplant moral philosophy, but to make the part of moral investigation that philosophy still does more philosophical, more "meta", more about pragmatic concerns regarding how to answer questions (what are we asking? what kind of thing would constitute a correct answer? how do we sort out which proposed answer that is?) than about speculating on answers and arguing about them from our armchairs. And then to augment that, not replace it, with the actual application of those philosophical answers to contingent normative questions about the actual world. -

A poll on hedonism as an ethical principleWhat is that criterion besides comforting/pleasing/helping rather than hurting?

— Pfhorrest

Well, you're against transcendentalism which doesn't leave a lot of options. — Wayfarer

Can you explain what a transcendental criterion would look like anyway? -

A poll on hedonism as an ethical principleThen how do we know that there is any reason to doubt them?

— Pfhorrest

Hopefully one wisens up to this fact as they grow up, through their experiences and gathered knowledge. — Tzeentch

Experiences of what? Knowledge of what? That something felt good at first but later lead to greater suffering? That’s information from your senses again, telling you that your earlier senses didn’t give you the full picture. It’s still your senses you ended up relying upon to tell you that, which is what you just said two posts ago can’t happen. -

What are we doing? Is/ought divide.We don't, and can't, do that at all for most of what counts as scientific knowledge; we simply accept or do not accept science on the basis that we trust or do not trust the experts. — Janus

That’s why I said, in the bit you cut out, that that’s the process said experts use, which makes the consensus of said experts trustworthy for the general public to rely on.

What feels good to me is not necessarily what feels good to others. — Janus

How things look or sound etc are not the same between every observer either. There are different kinds of colorblindness, actual blindness in different degrees, tetrachromaticity, different degrees of hearing sensitivity or deafness to different pitches of sound, people who can or can’t smell or taste various things or to whom they smell or taste different, etc.

Observations tell you a relationship between observers and the world; the predictions based on those observations are that certain types of observers will or won’t observe certain things. An ethical science would likewise have features of subjects of experience baked into both its input and its output.

people can turn suffering to good account — Janus

What is “good account” if not someone kind of enjoyable experience? e.g. getting hurt then recovering makes you stronger, being stronger makes you less likely to get hurt... the avoidance of pain is still the benefit there.

You seem to be using 'hedonism' in a tendentious way that is not in keeping with ordinary parlance — Janus

I’m using it in the ordinary philosophical way going back for thousands of years. You may as well complain that I’m not using “begging the question” in the ordinary way because I don’t misuse it like everyone does today. It’s ordinary people who misuse philosophical terms of art, not me who’s misusing ordinary language. -

A poll on hedonism as an ethical principleAristotelian philosophy generally is teleologically oriented - things have a purpose, a telos, which is the basis for what is considered good - being able to fulfil that purpose is a criterion of what is good — Wayfarer

What is purpose but what something is good for, what good comes as a consequence of it? — Pfhorrest

If what's good is fulfilling your purpose and your purpose is what good you can do, we're left with no idea what either "good" or "purpose" mean, other than that they're related -- which they definitely are. But we need more than that, some criterion by which to tell what something's purpose is, what effects of it are good. What is that criterion besides comforting/pleasing/helping rather than hurting?

Is there a box I can tick for that? — counterpunch

If you think it ought to be morally relevant to some kind of super perfectly ethical person, some saint or hero, even though you personally (like pretty much everyone) fall short of that, then I'd say that's answer #1 to the second question. -

What are we doing? Is/ought divide.What you are talking about is just psychology, and it is only akin to science in it's statistical dimension, and unlike other sciences it is always going to be reliant upon individual reports if it is not merely concerning behavior of people en masse. — Janus

Not at all what I'm talking about.

Empirical, descriptive, physical sciences depend on first-person experiences, because that's what observations are, but we don't just take somebody's word for what "looks true to me", or vote on what "looks true to me" to the most people, or anything like that. We replicate their experiences (observations) for ourselves when there's any doubt or disagreement about what's true: we go stand in the same contexts and see if we experience (observe) the same things ourselves, and then try to come up with some theory that explains how all of those experiences (observations) can be consistent with the same reality. The people doing the investigations do that, at least, and their consensus gets reported to the public at large. It's the replication and reconciliation of experiences (observations) that makes science what it is.

If we were to do something analogous with that for ethics, it likewise could not depend on taking someone's word about what "feels good to me", or voting on what "feels good to me" to the most people, or anything like that. We'd have to replicate their experiences (of things feeling good or bad) for ourselves when there's any doubt or disagreement about what's good: go stand in the same contexts and see if we experience the same things (good or bad feelings) ourselves, and then try to come up with some strategy to get to a state of affairs where all the good experiences are had and none of the bad ones are, and call that state of affairs the moral one. The people investigating what's moral would have to do that, at least, and we'd report their consensus to the public at large. It's the replication and reconciliation of experiences (of things feeling good or bad) that would make such a method analogous, make it a hedonic, prescriptive, ethical science.

I also don't think such investigations are necessary because we already know that being murdered, raped, robbed, beaten up, exploited, ridiculed and so on makes people feel bad — Janus

We also know a lot of things about reality just from our common experience of it too. Those aren't the things in question; although sometimes in the course of investigation we learn that everyone's common assumptions were actually wrong in some non-obvious way. Just because we all already know (or at least are very sure) that some common core of things are good or bad, doesn't mean there's not more to learn.

the problem with a hedonistic approach is that much that makes people feel good is not ethical because it is damaging to their health and people may then become burdens on others — Janus

What is "damage to health" but some bodily condition of suffering? And what is "being a burden on others" but seeing to your comfort costing someone else their comfort? Those are still hedonistic concerns. Hedonism doesn't mean short-sightedness or selfishness. -

What are we doing? Is/ought divide.In the case of ethical claims it is not so simple. There is nothing that is subject to direct observation and testing of predictions. — Janus

We COULD do for ethics something completely parallel to what we do for physical sciences: see what repeatably feels good rather than bad, take that as our repeatable “observations”, and then strategize plans that might satisfy all those feelings, just like we theorize explanations that might satisfy all observations, and then test them against the same kinds of things we based them on, repeat as necessary.

Of course not everybody AGREES that that would tell us everything or even anything there is to know about morality. But also not everybody agrees that science is the only, or even a, reliable way to learn about reality. Lots of people disagree with scientific results about evolution, cosmology, the brain, race, gender, sex, health care, climatology, even the shape of the planet. Does that somehow count against science?

Perhaps not coincidentally, those who reject both of the above methodologies seem to correlate with each other... and with religiosity.

Pfhorrest

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum