-

It is more reasonable to believe in the resurrection of Christ than to not.Therefore, in my precious post, saying that I wasn't aware of how Christianity was described by early Romans was just a sort of a soft introductory to describe my 'actual' Christianity that no Christian Church or Denomination in the world approves. On your side, you were interested in my introduction and said nothing about what came next :) — KerimF

Don't get me wrong. In no way was my goal with my last comment to attack you or exacerbate my ego. I just commented the beginning of your answer, because it was what most interested me and the points mentioned about Christianity, I decided not to comment because they are points about your personal interpretation of Christianity, something that has nothing to do with the initial proposal of the OP. :grin: -

It is more reasonable to believe in the resurrection of Christ than to not.I think your point about St Paul's talk of the spiritual body is something that a lot of Christians do not take on board fully. Many seem to exaggerate the importance of a physical resurrection. — Jack Cummins

There are very few true Christians. Ha! Claiming to believe in God is very easy, so that's what most of the faithful do. Often, they don't even know the basics of their beliefs.

The only thing I would say is that I am not sure that there is a complete difference between the physical and spiritual bodies, but more a gradation of density. There is recognition of this in quantum physics with a recognition of physical matter being energy.

This would give a potential for understanding of a resurrection body and similar matters. In particular, the transfiguration in the Bible may indicate the blurry edges of reality.

Perhaps the whole for and against the resurrection of Jesus could be transcended if we acknowledge the limitations of classical understandings of reality, opening up to a vision of multidimensional reality. — Jack Cummins

In my view, mixing theology, metaphysics and quantum physics does not go well. Even more, there is no evidence to prove these hypotheses - of other dimensions and worlds -. Until proven otherwise, the only existence that Is, is this. -

Super heroesThe current Hollywood super hero films - are they simply a continuation of the Gods theme that has been around for thousands of years? — david plumb

It is more of a tactic to publicize the political bias of producers and the people involved. -

TPF Quote Cabinet“We return evil for evil, in which there is no sin, for it is necessary to pay a wicked man in his own coin.” - Chanakya, Arthashastra

-

It is more reasonable to believe in the resurrection of Christ than to not.Thank you... I didn't imagine that such description of Christianity could be said in the far past — KerimF

I can assure you that 90% of people know nothing about history, let alone about the history of the Church. Therefore, it is not surprising that you were also unaware of these facts. -

It is more reasonable to believe in the resurrection of Christ than to not.Who cares what Paul said? Paul is dead, and nobody will ever know for sure what he said or what he meant. He may not have been clear about what he meant himself, who knows?

There are some words by somebody on some page. If we can use them, then use them — Hippyhead

The point is that the discussion between me and the OP started with the fact that in his original publication, he defended the thesis that the resurrection of Jesus Christ was a historic moment, something that I completely disagree with. And to discuss this subject, the biggest reference that can be used is Saint Paul and his scriptures, and as I have already said, he makes two statements that contradict each other. Either Saint Paul had been too naive - which I doubt very much - or he knew why he was using two contradictory arguments - doublethnk -.

The question of whether Christianity is good or not, useful or not, does not come into question, as it is not the issue being discussed. -

It is more reasonable to believe in the resurrection of Christ than to not.I’m not quite sure how you could make that claim when they were the ones who propagated and kept the faith alive and well through the church. — Josh Vasquez

First things first, during the "Apostolic Age" - from 33 AD - the supposed date of the death of Jesus of Nazareth - until about 100 AD - with the death of the last of Jesus' twelve Apostles, John the Evangelist - the "Church" as the organized institution based on a codified and canonized scripture did not exist. What existed were small groups - or as the Romans called their cult: superstitio - superstition - - that were completely descentralized in custom and methods of worship. Quoting Pliny the Younger about how the Romans viewed the young Christian church:

"Roman investigations into early Christianity found it an irreligious, novel, disobedient, even atheistic sub-sect of Judaism: it appeared to deny all forms of religion and was therefore superstitio."

Therefore, Christian belief was still the subject of fervent debate by all those who called themselves "Christians". The concept of "sōma pneumatikos" did not even exist, since there was no structured thinking about who he was, or better saying, who Is Jesus of Nazareth - during the period -. These thoughts only came to be structured with the conversion of Paul of Tarsus to Christianity, and his view that the Christian faith would only grow in the popular setting of Roman religions, if it were completely structured - therefore, different from all other religions, which until then, were not architected and absolute -.

With that in mind, I affirm that Paul's canonized claim in the Bible is wrong because it was a construction for the purpose of converting the masses - sōma pneumatikos or psychikos, it didn't matter to Paul as long as it made Christianity more attractive to the greek gentiles -, not to mention that when the first Bible was finalized - in 144 AD by Marcion of Sinope - Paul had died more than 80 years earlier.

Didn’t the apostle Paul write his letters? — Josh Vasquez

Thirteen of the twenty-seven books in the New Testament have traditionally been attributed to Paul. Seven of the Pauline epistles are undisputed by scholars as being authentic, with varying degrees of argument about the remainder. Recalling that, the only contact Paul had with Jesus Christ - if accepted as real - was during his conversion to Christianity, where he was traveling on the road from Jerusalem to Damascus on a mission to "arrest them - the christians - and bring them back to Jerusalem " when the ascended Jesus "appeared" to him in a great bright light. He was struck blind, but after three days his sight was restored. Paul undoubtedly did not have the same attachment to the Christian message as the twelve apostles, as he did not know the figure of Jesus in person, however without him, Christianity would not have flourished as it flourished, as he practically wrote half of the current canonical Bible - and for the ancients, the whole bible -.

Were the gospel writers not more closely associated to Jesus and his disciples than us? — Josh Vasquez

This was and remains one of the great problems of Christianity. Jesus left nothing written, so what we have is the individual interpretation of the apostles. It is no coincidence that a mere 10 years after Jesus' alleged death, Saint Thomas created the basis of Nestorian Christian belief. After they split up to spread the Gospels, each had their own experiences, feelings and "revelations", and it is no accident that no one was able to make sense of Christianity during its first 3 centuries of existence. It was Paul and his so-called "canonical" writings in Greece, Thomas and his revelations in the Levant, John and his messages in Britain, etc ... The truth is that nobody understood and still does not understand Jesus, because his message was left open.

It is no accident that eventually, after the death of the apostles, other people would argue to that they had had their own revelations of God as the apostles, and with that Gnosticism - gnōstikós - having knowledge - - would eventually be born and transform Christianity to a certain extent to a form reminiscent of current Christianity - every individual and its own interpretations are canonical -.

doesn’t that mean something is wrong with the faith of one who disagrees with them? — Josh Vasquez

Here you argue using the premise that the Bible contains true facts. If that is how you argue, there is no discussion, because then I would be completely wrong, for against dogma there is no argument.

History is a matter of fact and facts are not up for interpretation because that would go against the very nature of them being facts. Now there are certain books that I do believe could be up for interpretation such as the Psalms, Proverbs, Songs of Solomon, and Ecclesiastes but that is because these books were written as wisdom literature or poetry. The gospels of Jesus Christ and the letters in the New Testament are not genres that can be interpreted as one pleases. — Josh Vasquez

My position is that there are events, and subjects cited in the Bible, that there are no records - so far - anywhere else. There is no way to have a greay legitimacy on any subject, if there is only one source, because in all cases, the sources are biased towards those who wrote them.

From Gary R. Habermas’ and Michael R. Licona’s The Case for the Resurrection of Jesus:

“In [1 Corinthians] 2:14-15… Paul contrasts the natural and spiritual man, i.e., the unsaved man who is lead by his soulish or fleshly nature and the Christian who is led by the Holy Spirit. Now these are the same two words Paul employs in [1 Corinthians] 15:44 when, using the seed analogy, he contrasts the natural (psychikos) and spiritual (pneumatikos) body.”

Thus, when Paul speaks of the spiritual body, he is speaking of someone who’s spirit is being led by the Holy Spirit as opposed to its own selfish desire. According to scripture it seems as if when someone resurrects it is both a spiritual and physical resurrection. — Josh Vasquez

One of the letters sent by Paul to one of the early Greek churches, the First Epistle to the Corinthians, contains one of the earliest Christian creeds referring to post-mortem appearances of Jesus, and expressing the belief that he was raised from the dead, namely 1 Corinthians 15:3–8

"[3] For I handed on to you as of first importance what I in turn had received: that Christ died for our sins in accordance with the scriptures, [4] and that he was buried, and that he was raised on the third day in accordance with the scriptures, [5] and that he appeared to Cephas, then to the twelve. [6] Then he appeared to more than five hundred brothers and sisters at one time, most of whom are still alive, though some have died. [7] Then he appeared to James, then to all the apostles. [8] Last of all, as to one untimely born, he appeared also to me."

In the Jerusalem "ekklēsia" - Church -, from which Paul received this creed, the phrase "died for our sins" probably was an apologetic rationale for the death of Jesus as being part of God's plan and purpose, as evidenced in the scriptures. For Paul, it gained a deeper significance, providing "a basis for the salvation of sinful Gentiles apart from the Torah".

As Wedderburn, A.J.M. in his 1999 book Beyond Resurrection said:

"As Paul repeatedly insisted that the future resurrection would only include a spiritual or pneumatic body, denying any future for the flesh, it seems likely that this was also how he understood the resurrection body of Jesus." -

Belief in god is necessary for being good.tend to the political right — Banno

"Right-wing" has become a pejorative term. Oh! What great times do we live in... -

Are humans inherently good or evilwhether human is inherently good or evil. — Isabel Hu

Good and Egoism. - If you accept that humans are not "bad" but in fact "egoistic", you may realize that, in fact, "good" is just a reflection of someone's egoistic nature. So, in conclusion, good is unnecessary, but to exist as an option in life, egoism is bound to exist. -

Is Christianity really Satanic?1. If God were to strive – which means to exert himself vigorously or try hard – for anything, then it

would make him imperfect in nature

2. God is not imperfect in nature

3. Therefore, God does not strive (1,2 MT)

4. If God does not strive, then that entails he is lazy

5. Laziness is not a Godly virtue but a Satanic one

6. Therefore, Satan is inherent in God — Josh Vasquez

Now tell me if this is worth discussing...

Simplistic pseudo-argument based on the individual opinion of the OP simply because he has some resentment towards Christianity. Pathetic. -

Submit an article for publicationI didn't even know you had sent it. In our private conversation, you just went silent, giving no indication of what you were going to do, and I rarely check infoatthephilosophyforumdotcom . — jamalrob

I thought you didn't take my article proposal seriously and so I just decided to send it to the e-mail address that you gave me. If there was any misunderstanding, I apologize.

I've posted it in the editors' private area, so maybe someone will read it now. Thanks for the contribution. — jamalrob

Thank you. :smile: -

Submit an article for publicationHow is it possible that for all the time the Philosophy Forum has been in existence only the articles by Jamalrob and Lamarch have been deemed worthy to be posted???? — charles ferraro

DISCLAIMER:

I only submited my article for publication, but the editors still have not contacted me about it, even though, I said - to them - that even if it wasn't approved, I would like a response. -

Egoism: Humanity's Lost VirtueHi Charles. The philosophical vision that I defend here is completely original and constructed by me.

but didn't Nietzsche say all of this years ago? — charles ferraro

Nietzsche, in none of his works, defends the ego and egoism, much less the thought that human nature is that of egoism. The point that no one understands about Nietzsche's philosophy - and that ultimately makes that they don't understand nothing of his works - is that Nietzsche, while opposing nihilism, is in favor of it so that we can build a new society based on new values and "virtues". Nietzsche precisely refers to nihilism, not egoism.

What exactly is different, or original, about what you're saying? — charles ferraro

The whole article :smile: -

A question on moralityUgh, no. There are clearly moral and immoral actions. Perhaps we don't understand which one's are which as journey onto old age, but that is where we test and ask other people. — Philosophim

What makes a "moral" act be considered "moral"? I would say that a hegemony of thought - like a religion, a dogma, an ideology, a theory, etc ... -. We live in times where an absolute truth no longer exists because it has been completely discredited by the new generations, and now everyone is using its subjective truths - something internal; an internal knowledge perhaps? -. Neognosticism - commonly known as the lack of an absolute truth - is as present and real as the recreation of the classic globalized and secular world. The moral, and consequently, the immoral, no longer exist, because one depends on the other, and as the moral was "killed", the immoral is no longer obliged to exist.

Am I saying that this is good? No. What I argue for is that we should use that same subjectivity to create new concepts; concepts that make the individual and its egoism the center and focus of all human interaction and purpose.

In the case of OP, when you allow yourself to be freed from the putrid and common interactions of the masses, anguish - usually as a bad feeling, of strangeness, alienation - occurs, precisely by the act of freeing yourself from what is considered normal by the majority. -

A question on moralityI will have to avoid lesser people from now on, so I don't get my inner peace rolled over again? — TheDude

One of the most difficult acts of the individual to achieve is the total abandonment of any type of morality - which are chains that make it impossible for the individual to be fully potentialized - however, if reached, the anguish of realizing that its ego is the only one truly freed is destructive for those not prepared.

You live with the anguish of wanting to get rid of morality, however, when you are able to break free, anguish makes you look down, where the sea of the dull and contented mass resides, and while you look at it, it looks back at you , judging you, fearing you, envying you, all this and more because they are only they, and you are your own. -

The (?) Roman (?) Empire (?)This isn't to say it was "good." — Ciceronianus the White

The only purpose of a civilizaiton is to be good to its own people, nothing more, nothing less. Rome was good to Romans, ancient Greece was good to Ancient Greeks, etc... -

TPF Quote Cabinet“No future and no humanity, no communism and no anarchy is worthy of the sacrifice of my life. From the day that I discovered myself, I have considered myself as the supreme PURPOSE.” - Renzo Novatore

-

The (?) Roman (?) Empire (?)History is filled to the brim with horrors. No nation, no tribe is innocent. Placating our modern views and standards on the past as you are doing is pretty useless. Sure the Caesars killed many, that what kings and emperors do... Water under the bridge. — Olivier5

What he is not able to perceive is that this concept of "ethnic supremacy" did not exist - and in reality, never did exist - in the Classical Age. Human society is based on the victory of the best over the worst, always. A single person being against it is completely insignificant. I am grateful to our - and here I use plural because they were OUR and not MINE - ancestors for building a civilization as glorious and beautiful as Rome. It was built on blood, genocide and war, however, we are all sons of the winners - in the case of the West: Greece and Rome -; being ressentful for those who have long since lost, means nothing on the grand scale of humanity.

I thought that with JerseyFlight's ban this rotten and evil use of doublethink would have ended, however, it seems that these cancers keep spreading.. -

The (?) Roman (?) Empire (?)"Barbarians" could attain power through the military, which gained more and more influence over the succession. — Ciceronianus the White

Some examples of Barbarians attaining power in Roman society - that in itself is already a symptom of decadence and degradation - were Flavius Stilicho - he was a high-ranking general - magister militum - in the Roman army who, for a time, became the most powerful man in the Western Roman Empire. He was half Vandal and half Gothic and married to the niece of Emperor Theodosius I; his regency for the underage Honorius marked the high point of Germanic advancement in the service of Rome -, Flavius Aetius - was a Roman general of the closing period of the Western Roman Empire. He was half gothic. He was an able military commander and the most influential man in the Western Roman Empire for two decades - 433–454 -. He managed policy in regard to the attacks of barbarian federates settled throughout the Western Roman Empire. Notably, he mustered a large Roman and allied - foederati - army to stop the Huns in the Battle of the Catalaunian Plains, ending the devastating Hunnic invasion of Attila in 451. Edward Gibbon refers to him as "the man universally celebrated as the terror of Barbarians and the support of the Republic" -, and Flavius Aspar - was an Eastern Roman patrician and magister militum - "master of soldiers" - of Alanic-Gothic descent. As the general of a Germanic army in Roman service, Aspar exerted great influence on the Eastern Roman Emperors for half a century, from the 420s to his death in 471, over Theodosius II, Marcian and Leo I -.

For instance, Rome and to a greater extent Greece have to be condemned for their ethno-supremacism, for instance, though it must be said that Rome appears to have been far less ethno-supremacist than Greece — Tristan L

Yeah, let's condemn the precursors to our civilization. Nihilism at its peak... -

What are you listening to right now?"but this world is a broken home

just enough for the memory to feel right"

-

The (?) Roman (?) Empire (?)This is actually a very good example why in order to understand history it's important to focus on more than just one narrative. Perhaps what we lack in our history education still is to say while meanwhile... and just pick the focus and the narrative we like. — ssu

The problem with this is that humanity is essentially biased. If everyone has different opinions, which one is the real one? This was the case in which Roman civilization found itself when the west fell, and it was like that in the east - Byzantine - at the time of the Arab invasions. When a nation loses its base of values and absolute truths, most of the time, only with the introduction of new values by third parties - in the case of the Western Roman Empire, the Germans, and in the case of the East, the Arabs - that purpose can be reached again. I do not deny that the freedom of the ecumenical world is wonderful, but it seems that on the grand scale of history, hegemony and order is the most successful path.

The rise of Islam happened at the perfect time, when the Roman Empire (or the Byzantinians to us) just had with Emperor Heraclius finally delivered a crushing blow to Sassanid Empire only then to be also in a weak state to suffer a defeat to the Arabs and lose the crucial Nile valley, which basically was the only reason that Constantinople was able to be a megacity of it's time. With two empires being weak at the same time gave chance for a third to be formed. — ssu

The case of Islam is a great example of the phrase "give time to time, and everything will come true". The Arabian peninsula was always on the margins of ancient and classic societies, where no one sought to conquer and annex. It is obvious that if given time, some superpower would be born from there, and that became truth in the 6th century. -

TPF Quote Cabinet“But at the bottom, the immanent philosopher sees in the entire universe only the deepest longing for absolute annihilation, and it is as if he clearly hears the call that permeates all spheres of heaven: Redemption! Redemption! Death to our life! and the comforting answer: you will all find annihilation and be redeemed!” - Philipp Mainländer

-

The (?) Roman (?) Empire (?)As Rome wasn't alone and didn't just face "barbaric" tribes and the celts in the north, it would be interesting to learn how much the Persian Empire (Sassanid Empire etc.) of the same age left it's mark on the later era. Unfortunately the Mongols devastated the area of modern Iran and Iraq later while Western Europe avoided the Mongol scourge. Later Chinese culture and society obviously got similar influence from the age of Antiquity. — ssu

The human civilization of antiquity can be summarized in 4 states:

Roman Empire;

Sassanian Empire;

Aksumite Empire;

Han Dynasty of China;

All of them covered vast geographic territories, in addition to being provided with high levels of urbanization, bureaucratization and a wide locomotion structure, in addition to a stable and regulated economy. Life in the ancient classical world - excluding Late Antiquity - was practically like our own, minus the technology.

It is obvious that all these societies that represented the "globalized" world of the time would leave a unique legacy that would be the longing and inspiration for all the nations that would succeed them with the beginning of the Middle Ages. Like the Roman Empire, the Sassanid Empire also experienced submission by the Huns - The Hephthalites, also called the White Huns, were a people who lived in Central Asia and South Asia during the 5th to 8th centuries. Militarily important during 450 to 560, they were based in Bactria and expanded east to the Tarim Basin, west to Sogdia and south through Afghanistan to Pakistan and parts of northern India. They were a tribal confederation and included both nomadic and settled urban communities. They were part of the four major states known collectively as Xyon - Xionites - or Huna, being preceded by the Kidarites, and succeeded by the Alkhon and lastly the Nezak. All of these peoples have often been linked to the Huns who invaded Eastern Europe during the same period, and / or have been referred to as "Huns" -, and I can state through my studies, that the devastation faced by the Sassanids and by the Gupta dynasty in India, by the Huns, was twice as bad as that faced by the Romans in Europe.

The Aksumites paved the way for the future Ethiopian and Islamic nations of the Horn of Africa. And, well, China remains being China.

One of the biggest differences between the West and nations like Persia, was the situation in which one fell to the Islamic invasions - Sassanid Empire - completely, and the other resisted for more than 600 years - in the case of the Roman Empire -. We, unlike the Persians, were not Arabized - for now -.

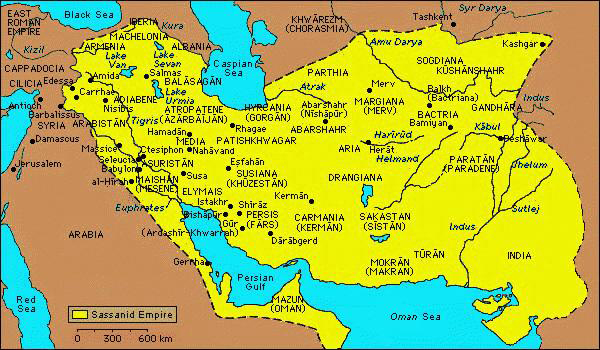

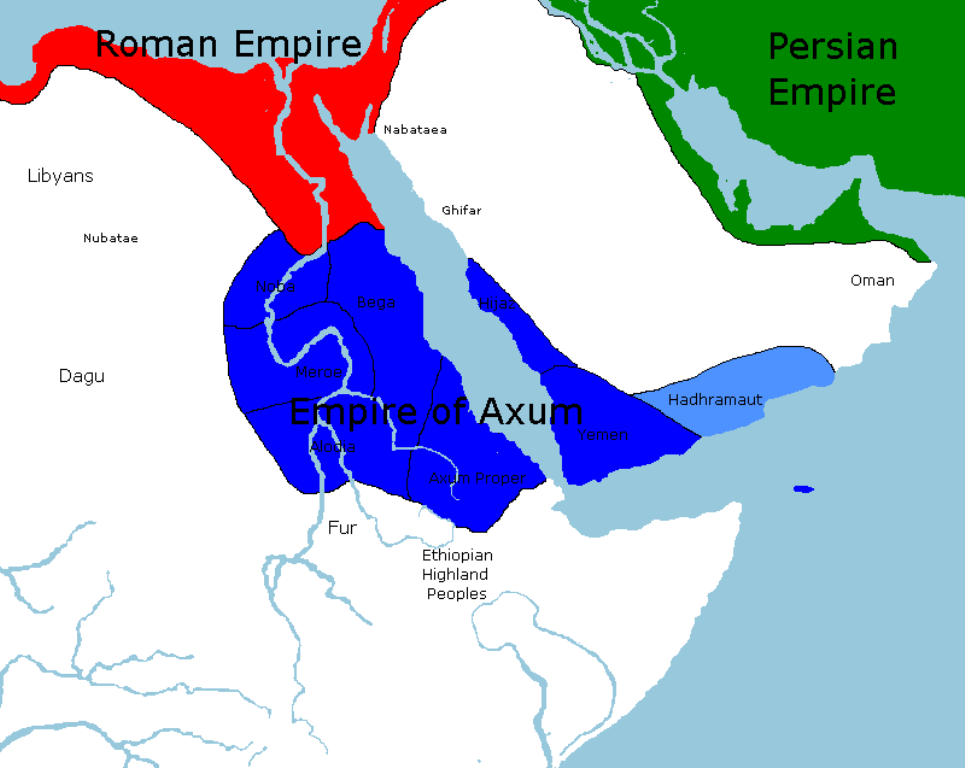

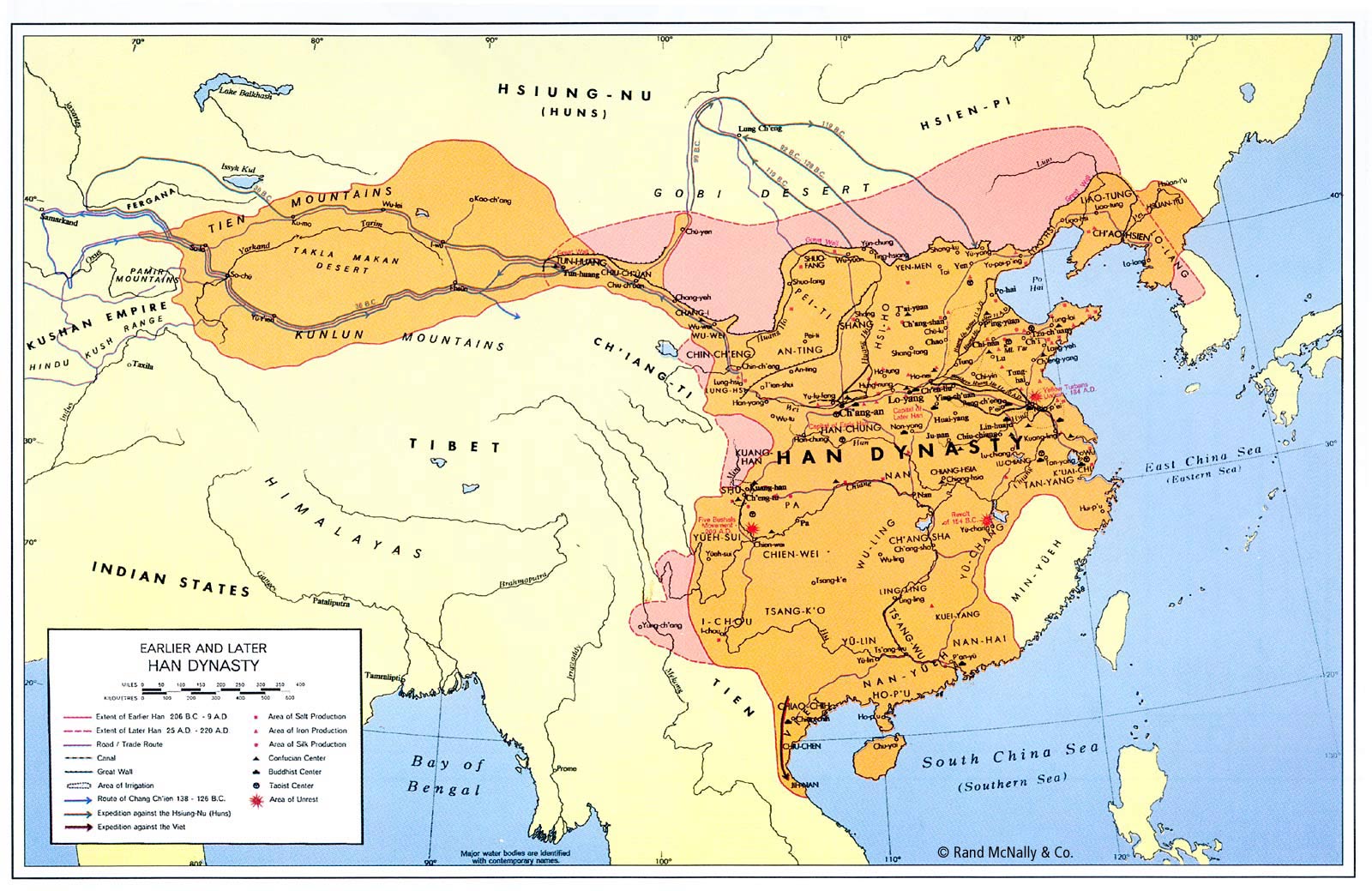

For the ones who don't know about Sassanid Persia, Aksumite Ethiopia, and Han China, here are some representation of their states:

Sassanid Empire;

Aksumite Empire;

Han Dynasty.

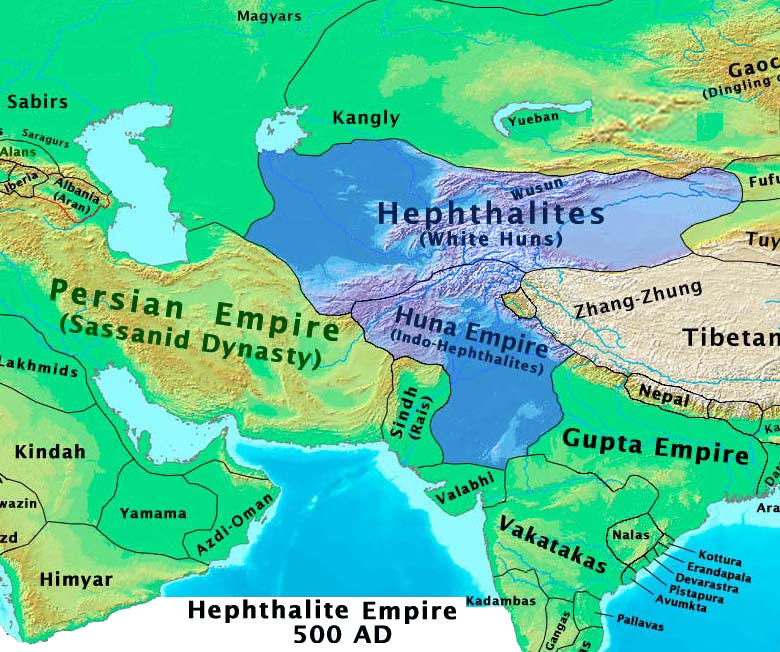

And for the Huns; while Rome suffered from the North:

China suffered from the North:

- Xianbei is another name given to the Huns by the Chinese -

And Sassanian Persia suffered from the East:

-

Which philosophy do you ascribe to and why?Just sheer curiosity. — Dina

Positive-Egoism.

Egoism is the nature of humanity and we should accept it. -

The (?) Roman (?) Empire (?)Due to the Roman Empire's vast extent and long endurance, the institutions and culture of Rome had a profound and lasting influence on the development of language, religion, art, architecture, philosophy, law, and forms of government in the territory it governed, and far beyond. The Latin language of the Romans evolved into the Romance languages of the medieval and modern world, while Medieval Greek became the language of the Eastern Roman Empire. The Empire's adoption of Christianity led to the formation of medieval Christendom. Greek and Roman art had a profound impact on the Italian Renaissance. Rome's architectural tradition served as the basis for Romanesque, Renaissance and Neoclassical architecture, and also had a strong influence on Islamic architecture. The corpus of Roman law has its descendants in many legal systems of the world today, such as the Napoleonic Code, while Rome's republican institutions have left an enduring legacy, influencing the Italian city-state republics of the medieval period, as well as the early United States and other modern democratic republics.

Even if you don't accept it, you're only You the way you are, because of Rome and Greece. Nihilism from the decadence of the prosperity of secular globalization. Where did I see that already? Oh, yes, Thebes and Rome, and now the West - you're a perfect example of this -. -

Are we on the verge of a cultural collapse?Are we on the verge of a cultural collapse?

Just look around you. What do you see? If it's not hegemonic, then the culture has been long dead.

“The most worthless of mankind are not afraid to condemn in others the same disorders which they allow in themselves; and can readily discover some nice difference in age, character, or station, to justify the partial distinction. Tolerance and diversity brought Roman civilization to its knees.”

Diversity is the decay of civilization. If your society doesn't know anymore what it is, some other culture - more strong and willful - will prevail in its stead... -

The (?) Roman (?) Empire (?)One great vice of the Romans and even more so the Greeks was their ethno-supremacism. — Tristan L

By my egoism! Please stop filling the discussion with garbage and stupid revisionism.

The purpose of my discussion was not to judge the Romans, as this is out of the question. If you have any personal resentment for them, history doesn't care, because you only live as you do, thanks to all the splendor of the Greeks and the Romans. So please, if you are a putrid revisionist, I kindly ask you to withdraw from the discussion. You can create your own and fill it with this value inversion garbage :) -

Egoism: Humanity's Lost VirtueAs far as I can see, compassion boils down to being able to put yourself in another person's shoes - feel what s/he feels - and this ability is called empathy, it's the bedrock of the ubiquitous moral principle known as the golden rule.

Notice though that the measure used in compassion, empathy, and the golden rule, is the self. Compassion and its retinue of beliefs/emotions is all about getting in touch with the feelings of others. That, however, is restricted/privileged information - it's impossible to know what another person is actually thinking/feeling. The only option then is to imagine yourself into other people's situation and get an idea of what you yourself would feel in it. In other words, you're confined, even in the most selfless sense of true compassion, to your own ego. — TheMadFool

:100: -

The (?) Roman (?) Empire (?)Yeah, I don't really have any qualm calling it a "Dark Age", one of many in human history. Dark Ages tend to be ages that occur after flourishings. They are sort of desolutions of empires, ideas, commerce, and technology. Many societies have had them for environmental, cultural, and economic reasons. Label it whatever you want, but Dark Ages fits fine with me. I also think the years you use are well enough. I've seen everything from 800s-1000s, so anywhere in there probably works, depending on how you demarcate the age. — schopenhauer1

I think it is a problem located only here in Brazil; this discussion of the term "Dark Ages". Almost all "academics" favor ending the use of "Dark Ages" because "it makes young people have a bad impression of the past", when over 95% of them doesn't even worry about the past 20 years.

But I guess my question is, how is it between that time, that the Germanic peoples went from tribal to feudal? Specifically in my last post, it seems that Germanic tribes were more pastoral than they were farmers. Yet, feudalism was dominated by crops, farming, planting, etc. How and when did this take place in the years between lets say 500 and 900 CE? — schopenhauer1

I think this has already been answered by our past discussion and your well-placed points.

"1.) The Catholic Church had no interest in competing with tribal chieftains for power and conversion. Local chieftains often had the backing of tradition (including pagan religious practices) to keep them in power. Wherever a chieftain converted to Christianity, so went the tribe. Thus converting to Christianity, often stripped away tribal privileges and rites to Christian ones, taking away local identity and replacing it with a more universal one.

2.) Charlemagne's own policies unified Germanic tribal identities. His court was filled with key positions from leaders of different tribal affiliations. He can have Saxon, Gothic, Jutes, Burgundians, all in the same court. This intermixing led to slow dissipation over probably 100 years of keeping tribal affiliations intact in favor of hereditary identification only.

3.) Roman Law- With the integration of Germanic tribes into the Roman political and military system, these Germans became more Romanized. This in itself, could have diminished the identity with tribe for identity with a territory or legal entity. Thus various Germanic "dux" (dukes) within the Roman Empire were already in place along Spain and southern France (as were ancestors of Charlemagne). Being incorporated in a multi-ethnic Empire itself could diminish the fealty towards local affiliation with any one tribe. With the Church's help in keeping records in monasteries and libraries, these leaders retained Roman law far into the Holy Roman Empire's reign.

4.) Nobility transfer by kings- Since the unification of Charlemagne, there was a conference of land and title from top-down sources. As local tribal kings (chieftains?) were quashed during the wars of Charlemagne, he then doled out titles of land (dukes and counts) to those he favored, thus diminishing the local identity of leadership further.

It is a fact that the barbarian germanic tribes eventually assimilated to Roman culture. The point is that they simply made this culture theirs:

"Over time, the Lombards gradually adopted Roman titles, names, and traditions. By the time Paul the Deacon was writing in the late 8th century, the Lombardic language, dress and hairstyles had all disappeared. Paul writes:

The Lombards live and dress as if all the land they currently inhabit - referring to Italy - was their native land: We are from Lombardy! Some would have the courage to shout - referring to the Lombards who called Italy as Lombardy -."

My point is that Charlemagne was the first European monarch, after the fall of Rome to really bring to public knowledge to the masses, that everything they had was the legacy of a fallen civilization - remembering here, that for the ordinary citizen of the 8th century from Western Europe, the Byzantine Empire was seen as the "nation of the Greeks" -.

The only real barbaric people who were completely assimilated and tried to maintain Roman order during the fall of the Roman Empire and afterwards, were the Visigoths. The Visigoths were romanized central Europeans who had moved west from the Danube Valley. They became foederati of Rome, and wanted to restore the Roman order against the hordes of Vandals, Alans and Suebi. The Western Roman Empire fell in 476 AD; therefore, the Visigoths believed they had the right to take the territories that Rome had promised in Hispania in exchange for restoring the Roman order - and they tried -."

And so forth, -

Age of AnnihilationIf this is the peak of this cycle of civilization, we should be grateful that we got to be here to experience it. — Hippyhead

It is very likely that this will be humanity's last civilizatory cycle. If we destroy ourselves - and it is almost certain that we will - I very much doubt that another human civilization based on fossil fuels will emerge again. With the easiest roots to reach depleted, and without the current technology capable of reaching the deepest and most difficult, we will probably never leave a medieval proto-modern state of technology again. Unless we develop some other way of producing energy other than with fossil fuel. Humanity may surprise us, but I still believe it will be the end. -

I am DussiasI greet you, as my pretension is of good. This is a time of war, I'm sure you're aware. Let us find the best ideas through honest debate, for truth is unknowable but honesty is unmistakable. — dussias

We live during the fall of our Rome. It's uncommon to people to become aware of it.

I greet you. -

The "One" and "God"

-

The "One" and "God"You gotta admit it’s pretty self-denying for anyone to deny sentience or self-awareness. — praxis

I am not here to discuss whether Plotinus is correct or not. I am simply stating that people, when reading his works, easily confuse the concept of the One with God. -

The (?) Roman (?) Empire (?)True, though I thin the "Dark Ages" in Europe had a slower progression of change than say the 500 years after the Renaissance. — schopenhauer1

I would like to make it public my favor for the use of the term "Dark Ages" to cover the period from 476 AD - deposition of Romulus Augustulus by Odoacer - until the year 1066 - victory of William the Conqueror for the throne of the Kingdom of England, and death of Harald Hardrada - bringing the end of the Viking Age - in the battle of Stanford Bridge - to contextualize the cultural, economic, moral, and religious retrocess that happened between that period. The argument that those opposed to the use of "Dark Ages" is that it was a period with some cultural and technological advancement, using the examples of Charlemagne's Empire and the Umayyad Caliphate of Cordoba, however, I argue. How could there be a technological and cultural "advance", since the period occurred on the ruins of a precursor civilization that was more advanced in all aspects?

I agree that the term shouldn't be applied to the Late Middle Ages - from 1067 to 1453 - because the Christian Germanic culture during that period really brought a new vision of culture and technological air different and independent from the old Roman heritage. However, I cannot see the period between 476 and 1066 as being anything more than a "Age of Darkness".

For egoism sake, even the medievals saw the time from 476 to 1066 a era of Dark. Petrach - medieval scholar that lived from 1304 to 1374 - said:

"Amidst the errors there shone forth men of genius; no less keen were their eyes, although they were surrounded by darkness and dense gloom".

Even the use of the term "Rennaissance" seems to imply that before it, there was something "Bleak" - and that was in the "Modern Age" -. -

The "One" and "God"This is one reason why people have trouble understanding Plotinus. Metaphysical concepts which have contrary incompatible underlying assumptions cannot be used interchangeably without introducing equivocation and logical incoherence.

Plato mostly got these right whereas Platonists uniformly get them wrong. It is amazing how a fundamentally simple closed static One can be confused with an open transcendent interactive Good, or how either can be thought of as an active creative Agent. — magritte

The first purpose of this discussion of mine was about the fact that people find it very easy to confuse the concepts of the One with God. It is probably because of the interchangeable use of some concepts by Plotinus, but it is also likely that his philosophy was focused on a group of people who would understand what Plotinus was trying to explain - his students -.

Gus Lamarch

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum