-

Idealism in ContextI've copied this passage you provided elsewhere because I would appreciate your perspective on the issue I've raised in the OP, specifically in two paragraphs after the heading The Matter with Matter.

RevealThe earlier philosophy of St Thomas Aquinas, building on Aristotle, maintained that true knowledge arises from a real union between knower and known. As Aristotle put it, “the soul (psuchē) is, in a way, all things,”² meaning that the intellect becomes what it knows by receiving the form of the known object. Aquinas elaborated this with the principle that “the thing known is in the knower according to the mode of the knower.”³ In this view, to know something is not simply to construct a mental representation of it, but to participate in its form — to take into oneself, immaterially, the essence of what the thing is. (Here one may discern an echo of that inward unity — a kind of at-one-ness between subject and object — that contemplative traditions across cultures have long sought, not through discursive analysis but through direct insight.) Such noetic insight, unlike sensory knowledge, disengages the form of the particular from its individuating material conditions, allowing the intellect to apprehend it in its universality. This process — abstraction— is not merely a mental filtering but a form of participatory knowing: the intellect is conformed to the particular, and that conformity gives rise to true insight. Thus, knowledge is not an external mapping of the world but an assimilation, a union that bridges the gap between subject and object through shared intelligibility.

By contrast, the word objective, in its modern philosophical usage — “not dependent on the mind for existence” — entered the English lexicon only in the early 17th century, during the formative period of modern science, marked by the shift away from the philosophy of the medievals. This marks a profound shift in the way existence itself was understood. As noted, for medieval and pre-modern philosophy, the real is the intelligible, and to know what is real is to participate in a cosmos imbued with meaning, value, and purpose. But in the new, scientific outlook, to be real increasingly meant to be mind-independent — and knowledge of it was understood to be describable in purely quantitative, mechanical terms, independently of any observer. The implicit result is that reality–as–such is something we are apart from, outside of, separate to.

One of the central flaws in Kant’s theory of knowledge is that he has blown up the bridge of action by which real beings manifest their natures to our cognitive receiving sets. He admits that things in themselves act on us, on our senses; but he insists that such action reveals nothing intelligible about these beings, nothing about their natures in themselves, only an unordered, unstructured sense manifold that we have to order and structure from within ourselves. — W. Norris Clarke - The One and the Many: A Contemporary Thomistic Metaphysics

So what I'm arguing is that it wasn't Kant who 'blew up the bridge', but the developments in the early modern period to which Kant was responding. As is well known, Kant accepted the tenets of Newtonian science, and sought to present a philosophy that could accomodate this, while still 'making room for faith' (his expression).

I suspect, but I don't yet know, that some of the modern analytical Thomists - I'm thinking Bernard Lonergan - might have explored this issue. Also a difficult book called Kant's Theory of Normativity, Konstantin Pollok (ref). -

The Christian narrativeIs your claim that if the dog we call Bee had a different DNA, it would be a different dog? — Banno

Of course, but it would still be a dog, not an elephant or a cat. Surely the distinction between different canines can be accomodated by the Thomistic distinction between essence and accident. -

The Christian narrativeIt just seems like a pointless field of study - trivial, redundant, not informative, not interesting in light of my perspective on the world. — Apustimelogist

Yet, here you are :wink: -

The Christian narrativeAre you saying the essence of a my dog, Bee, is her DNA? — frank

As I understand it, and Heaven forbid, were it to come to pass that your dog Bee was caught in some terrible calamity, such that her mortal form were utterly destroyed, provided what was left was not incinerated, then her identity could be definitively ascertained from her DNA, by comparing it with remnants left on her artifacts etc. So, yes, DNA is very much like the molecular counterpart of 'essence'.

Banno and I have discussed this before, but a Platonist riddle is sometimes presented in school texts, in regard to the question of form and identity:

A man (not a man)

Throws a stone (not a stone)

At a bird (not a bird)

On a tree (not a tree)

The solution is, a eunuch (not a man, because, you know...) throws piece of pumice (not a stone, because it floats) at a bat (has wings, but also fur) hanging from a reed (not a tree, because no branches.)

I suppose it's a rhetorical exercise in appearance and reality.

I think the undercurrent to all of this (and metaphysics generally) is indeed the search for definition, in the sense of the ability to see what is. When reduced to textbook examples for pedagogical purposes, it seems straightforward, but in real life, it's often considerably more difficult. -

The Mind-Created WorldI conclude that your position is somewhere in platonist territory, and that you think that nominalism amounts to denying their existence. I don't agree with either conjunct — Ludwig V

The decline of Platonist realism is well-established intellectual history. The constellations of attitudes which Lloyd Gerson designates 'Ur-Platonism' (the broader Platonist movement including but not limited to the Dialogues of Plato) is realist about universals (see Edward Feser Join the Ur-Platonist Alliance). But to say that, is to invite the question, 'if they're real, where do they exist?' The usual response is to say that they're the products of the human mind, and so of the h.sapiens brain, conditioned as it is by adaptive necessity and so on. This is the 'naturalised epistemology' route. The neo-traditionalist approach is that the ability to perceive universals and abstract relations is the hallmark of the rational intellect which differentiates humans as 'the rational animal'. It doesn't take issue with the facts of natural science, but differs with respect to the interpretation of meaning.

I thought you believed that our concepts and perceptions were all constructs. — Ludwig V

One of the central questions of philosophy is what, if anything, exists sui generis—independent of construction—and what relation our mental constructs bear to it. -

The Mind-Created WorldThe Ted Kaczynski archive?

I offer this far more simple excerpt from the Nishijima-roshi, a Sōtō Zen priest who died in 2012, in respect of the real and the existent:

The Universe is, according to philosophers who base their beliefs on idealism, a place of the spirit. Other philosophers whose beliefs are based on a materialistic view, say that the Universe is composed of the matter we see in front of our eyes. Buddhist philosophy takes a view which is neither idealistic nor materialistic; Buddhists do not believe that the Universe is composed of only matter. They believe that there is something else other than matter. But there is a difficulty here; if we use a concept like spirit to describe that something else other than matter, people are prone to interpret Buddhism as some form of spiritualistic religion and think that Buddhists must therefore believe in the actual existence of spirit.

So it becomes very important to understand the Buddhist view of the concept spirit. I am careful to refer to spirit as a concept here because in fact Buddhism does not believe in the actual existence of spirit. So what is this something else other than matter which exists in this Universe? If we think that there is a something which actually exists other than matter, our understanding will not be correct; nothing physical exists outside of matter.

Buddhists believe in the existence of the Universe. Some people explain the Universe as a universe based on matter. But there also exists something which we call value or meaning. A Universe consisting only of matter leaves no room for value or meaning in civilizations and cultures. Matter alone has no value. We can say that the Universe is constructed with matter, but we must also say that matter works for some purpose.

So in our understanding of the Universe we should recognize the existence of something other than matter. We can call that something spirit, but if we do we should remember that in Buddhism, the word spirit is a figurative expression for value or meaning. We do not say that spirit exists in reality; we use the concept only figuratively. — Gudo Nishijima-roshi, Three Philosophies and One Reality

Compare with Terrence Deacon’s absential:

Absential: The paradoxical intrinsic property of existing with respect to something missing, separate, and possibly nonexistent. Although this property is irrelevant when it comes to inanimate things, it is a defining property of life and mind; described as a constitutive absence.

Constitutive absence: A particular and precise missing something that is a critical defining attribute of 'ententional' phenomena, such as functions, thoughts, adaptations, purposes, and subjective experiences.

Also Wittgenstein's aphorism:

The sense of the world must lie outside the world. In the world everything is as it is and happens as it does happen. In it there is no value—and if there were, it would be of no value. -

Idealism in ContextEven in fee will, the present has been determined. — RussellA

What is a table to you, is a meal to a termite, and a landing place to a bird.

A table is an object, not a relation. — RussellA

Without wanting to wade into the endless quantum quandries, I really do not see how determinism can survive the uncertainty principle, nor the unpredictability of the quantum leap. This is what Einstein complained about, when he said 'God does not play dice'. But it seems irrefutable nowadays, that at a fundamental level, physical reality is not fully determined. The LaPlace Daemon model of inexorable past events determining a certain course has long gone. -

The Christian narrativeThe term "essence" has been used in very different ways throughout the history of philosophy. Locke's real/nominal essences are very different from what Hegel has in mind and both are very different from what modern analytics have in mind, with their "sets of properties"/bundle theories, which is wholly at odds with how the Islamic and Scholastic thinkers thought of essences. — Count Timothy von Icarus

Not only different cultures, but also different forms, levels or states of consciousness. Something the Scholastics and Islamists will understand that the analytics will not.

A lot of fuss about very little here. I think I triggered it, by trying to point out that the word 'essence' is obviously a form of the Latin 'esse', 'to be'. So it denotes the essential qualities of a particular, what makes it what it is.

Apropos of which Max Delbrück, a physicist turned biologist, famously argued that Aristotle, in his biological writings, had anticipated the core principle of DNA: that a living being's development is guided by an inherent "form" or plan. Delbrück saw Aristotle's concept of the soul (psuche) as the form (morphe) that shapes and directs matter, mirroring the way DNA encodes the blueprint for an organism's development. He even humorously suggested that Aristotle deserved a Nobel Prize in biology for this insight (however Nobel prizes are never awarded posthumously, much less to someone who died more than two millenia ago.) Delbrück highlighted that it's the formal aspect of DNA, the information it carries, rather than the physical material of DNA itself, that is crucial for inheritance and development. This aligns with Aristotle's view that the soul (form) is distinct from the physical body. Also, presumably, one of the reasons that Aristotle's hylomorphism is still very much a live option in contemporary philosophy.

Aristotle, in his writings on embryology and reproduction, emphasized the role of "form" or "entelechy" as the principle that shapes and guides the development of living things. He saw semen as carrying this form, which directs the development of the offspring.

What has this to do with essence? It's that the same philosophical heritage that gave rise to 'essence' and 'substance', also gave rise to the scientific disciplines that discovered DNA. And I don't think this is coincidental. -

The Musk PlutocracyI wasn’t able to find the David Pakman commentary — T Clark

He has a YouTube channel https://www.youtube.com/@thedavidpakmanshow . I much prefer Brian Tyler Cohen and Glenn Kirshner, although it should be acknowledged that the anti-MAGA media is feeling extremely discouraged at this time. The bad guys really are winning, or so it seems. -

The Mind-Created WorldRight — and that’s why I found the Rödl passage interesting. He’s saying that logical principles don’t ground experience, but they also can’t be treated as a mind-independent reality separate from it. That’s why empirical knowledge remains incomplete if we treat it on its own. My point about the existence–reality distinction is very much in that spirit: we shouldn’t collapse reality into empirical existence, but we also shouldn’t reify reality as if it were some external substrate “out there".

-

Idealism in ContextIf one were to put it this way: instead of consciousness arising from matter, matter arises within consciousness. — Tom Storm

I'm trying to stick with epistemological idealism: matter arises within consciousness, because consciousness is a necessary pre-requisite to knowledge. Whatever we know, is disclosed through consciousness. This is, I hope, also consistent with the phenomenological attitude of attention to the fundamental characteristics of lived experience. As Husserl says, 'the world is disclosed by consciousness' - not that 'consciousness' is some kind of magic ingredient.

In other words, reality is pure consciousness. — Tom Storm

On face value, this collapses all manner of important distinctions. You might encounter such a statement in for example, Advaita Vedanta, but there it situated within a framework which stipulates the context and meaning. In another context it might mean something very different.

Kant is a kind of dualist with his phenomena/noumena distinction. — Tom Storm

He is! Perhaps @Mww can check in here, but I often refer to this passage:

The transcendental idealist... can be an empirical realist, hence, as he is called, a dualist, i.e., he can concede the existence of matter without going beyond mere self-consciousness and assuming something more than the certainty of representations in me, hence the cogito ergo sum. For because he allows this matter and even its inner possibility to be valid only for appearance– which, separated from our sensibility, is nothing – matter for him is only a species of representations (intuition), which are called external, not as if they related to objects that are external in themselves but because they relate perceptions to space, where all things are external to one another, but that space itself is in us. (A370) — A370

My belief about the in-itself is that it has caused a great deal of baseless speculation, even by many learned expositors of Kant's philosophy. I interpret it very simply - it is simply the world (object, thing) as it is in itself outside all cognition and perception of it. As soon as the thought arises, well, what could that be? - the point is already lost! We're then trying to 'make something out of it'. But, we don't know! Very simple. -

Donald Trump (All Trump Conversations Here)You guys should read more Wall Street Journal and less of whatever it is you're reading. — frank

Washington Post, NY Times, Australian Broadcasting Commission, CNN, etc. Occasional stories from Wall Street Journal through Apple News. The ‘important stuff’ I see Trump doing is undermining democratic norms, attacking science, public education, public health and public broadcasting. Deprecating the power of Congress and attacking the Judiciary. Preparing to betray Ukraine out of his infatuation with strong-man Putin. -

The Mind-Created WorldThe title of that very difficult book is Self-Consciousness and Objectivity: An Introduction to Absolute Idealism. Do you think the absolute idealism of the title is something he is trying to advocate and explain? Or as something he wishes to rebut?

Sorry, it was a bad choice of words on my part, I was irritated. To say it more philosophically: I read your responses to this OP as specious because I don’t think they demonstrate any grasp of the point being made. It is one thing to rebut an argument by showing faults with it, but not seeing the point of an argument is not a rebuttal, and nothing you’ve said indicates that you see the point of the argument. -

The Mind-Created Worldwhy I think Wayfarer's crusade is largely vacuous and pointless. — Apustimelogist

Whereas from my perspective that is a fair description of your responses to it, but let’s not get involved in mudslinging.

I think that only things that are created and maintained in existence by the mind are mind-dependent. That makes for quite a short list. — Ludwig V

That would be the mainstream understanding. The point of philosophical analysis is to see through it. -

Ukraine CrisisFrom the day-after headlines, it seems pretty clear that Trump is going to back Putin and sell Ukraine out. Reports are circulating that Putin’s conditions for a ceasefire requiring the surrendering of territory including regions not yet under Russia’s control. I suspect Trump is going to press Putin’s case in these follow-up calls with Zelenskyy and NATO, and then accuse Ukraine of being uncooperative when they won’t go along with the terms. Marjorie Taylor Greene is already Trumpeting the view that Ukraine is the real culprit in all of this. The betrayal begins.

-

The Mind-Created WorldCan you unpack what Rödl means here by the incomprehensibility of the judgment of experience? Is he pointing to the problem of grounding causal necessity in logical necessity? And how do you see this bearing on our discussion? What do you mean by ‘the ground being sought by either lexicon’?

-

The Mind-Created WorldWhat, exactly, is their ontological standing? Are we talking platonism here? — Ludwig V

The fact that the theoretical constructs are an essential constituent of what is considered real, while they're not themselves existent in the way that the objects of the theory are. -

Idealism in ContextSo if someone says 'there is nothing except consciousness" what is your view of this? — Tom Storm

My response would be 'what do you mean?' It might be a meaningful expression, but that would depend on whether it was being said by someone who actually understood it. -

Idealism in ContextI’m still not entirely clear on the exact difference between Kant’s transcendental idealism and classical idealism. Kant isn’t really saying that everything is consciousness, is he? He’s saying that there is something out there (we can't apprehend), and we shape our experience of it through our cognitive apparatus and this we experience as phenomena/reality. Which sounds similar to some of the perspectives you have offered. Thoughts? — Tom Storm

I'm attempting to portray Kant's form of idealism. The term 'classical ideaiism' is a little misleading, because idealism itself is a modern idea - that's one of the points of the OP. The term only comes into use in the early modern period.

The meaning of the expression 'everything is in consciousness' is elusive. It is often taken to mean that its adherents say the world is all in the mind of the perceiver - everything is in my consciousness. But that leads to problems of solipsism. I think it's the incorrect perspective - we're trying to stand apart from 'the world' and 'the observer' as if seeing them from some point outside both. But we can't do that.

I really got the sense of what it means for 'mind to create world' through meditation - seeing that process unfolding moment to moment. This process of world-creation is actually going on, all the time - it is what consciousness is doing every second. Becoming directly aware of that world-making process is key. As I've mentioned, I learned about Kant from a scholarly book comparing Buddhist and Kantian philosophy (ref). At the same time this process is happening, there is a vastness beyond that process. I learned about that from Krishnamurti.

Well said, except a minor quibble, — Mww

Thanks, it was carelessly expressed on my part.

I agree that it it seems plain that Edinburgh and London exist in different places independently of our knowledge of them.

The concept "relation" certainly exists in our mind, in that I know that Edinburgh is to the north of London.

But is it the case that relations exist independently of the mind? — RussellA

I see you’re taking a deflationary approach by treating relations as a matter of linguistic convention. But this, I think, misses Russell’s central claim in The World of Universals.

The relation “north of” isn’t just a word we happen to use; it’s something our words pick out. If London had never been discovered, or if nobody ever thought about Edinburgh, the fact that one is north of the other would still obtain. Coordinates make this more explicit, but they don’t abolish the relation — they presuppose it. A system of latitude and longitude is itself a network of relations.

The point is that universals are not “in the mind” — not mere thoughts or conventions. But nor are they independent existents like Edinburgh or London. They are real in the noetic sense: they are what is apprehended in thought. As Russell says, they are not thoughts, though when they are known they are objects of thought. That’s why Russell calls universals real — they aren’t “in the mind,” but only minds can apprehend them. Relations may be expressed in language, but they aren’t created by language — they’re the logical structure that language captures. Again the 'world-building' activity of the mind is always going on, but we don't notice that. We're looking through it, practicing philosophy and meditation is learning to look at it.

In B276 of his Critique of Pure Reason, in his Refutation of Idealism, he attempts the proof of his theorem "The mere, but empirically determined, consciousness of my own existence proves the existence of objects in space outside me." — RussellA

Indeed - which was directed at Berkeley's idealism. As I mentioned in the OP, after the first edition of CPR, critics said Kant was just recycling Berkeley's idealism, which annoyed him considerably. So he included his 'refutation of idealism' in the B edition, as you say, arguing that the determination of one's own existence in time relies on the perception of something persistent outside of oneself. This challenges what he calls "problematic idealism," of Berkeley's type, which casts doubt on the existence of external objects. -

Idealism in ContextAgree. I might mention the interview where I first read it. It’s a good intro to Bernardo Kastrup, and he’s definitely worth knowing about.

-

Idealism in ContextI agree. I like that image of Kastrup that ‘tears are what sorrow looks like from the outside’ (but then, it’s such a sensitive new-age analogy….)

-

Idealism in ContextKastrup, as you know, wrote a book on Schopenhauer (Decoding Schopenhauer’s Metaphysics) which I found very good, and Schopenhauer saw himself (rightly or not) as Kant’s successor. Now you mention it, I don’t recall Kastrup saying much about Kant, but I think Kant, Schopenhauer, and Kastrup could comfortably fit under one umbrella, so to speak.

//although they might elbow each other from time to time :rofl: // -

Idealism in ContextA simplistic dichotomy, and simplistic analyses never apply to Kant. The actual distinction Kant makes is between empirical realism and transcendental idealism, which he sees as complementary and not conflicting.

For Kant, empirical realism means that objects of experience - the phenomena we encounter in space and time - are real within the empirical domain. When we perceive a tree or a rock, these objects have objective reality as appearances.

Transcendental idealism, on the other hand, holds that space, time, and the categories of understanding are not features of things as they exist independently of our cognitive faculties, but rather are the forms through which experience is structured or articulated.

Kant sees these as working together rather than in tension: we can be realists about the empirical world precisely because we understand or have insight into the transcendental conditions of experience. The empirical reality of objects is grounded in the fact that they conform to the universal and necessary structures of cognition (space, time, causality, and so forth).

This allows Kant to avoid both the skeptical problems he saw in Hume’s empiricism and what he considered the dogmatic excesses of rationalist metaphysics (e.g. Berkeley). We can have genuine knowledge of objects, but only as they appear to us under the conditions that make experience possible, not as they might exist independently of those conditions.

On the second point, you’re correct. -

To What Extent is Panpsychism an Illusion?

The “unity of experience” isn’t just a special riddle for consciousness—it’s mirrored by the unity of life itself. Just as an organism isn’t literally built by stitching cells together but emerges as a whole with its own integrity, consciousness may be the subjective expression of this same principle of organismic unity.

In philosophy the question of the subjective unity of experience was considered by Kant, but the unity of organisms goes back to Aristotle. It is also a major focus of enactivism and phenomenology. -

On emergence and consciousnessMy own view is that a naturalistic account of the strong emergence of mental properties, (that incorporates concepts from ethology and anthropology), including consciousness, can be consistent with a form of non-reductive physicalism or Aristotelian monism (i.e. hylomorphism) that excludes the conceivability of p-zombies and hence does away with the hard problem — Pierre-Normand

So, more of a Frankenstein than a zombie, then. :wink: -

Donald Trump (All Trump Conversations Here)I was referring more to the event - pomp, pageantry and nothing of consequence.

-

Donald Trump (All Trump Conversations Here)No, what I said: a nothingburger. Spectacle and empty words.

-

Donald Trump (All Trump Conversations Here)What’s that horrible Americanism that Trump sycophants always used about the findings of various criminal and civil investigations into him, even when they were clearly incriminatory? Oh that’s right: a big, fat nothingburger.

Big gift to Vlad the Destroyer, though, being treated like a dignitary instead of the criminal terrorist he so plainly is. -

Idealism in ContextWhen a body is caused to accelerate, it may continue to accelerate long after that cause has ceased acting. — Metaphysician Undercover

This statement is incorrect according to Newton’s first law of motion (the law of inertia).

When a force causes a body to accelerate, the acceleration only continues as long as that net force is acting on the object. Once the force ceases, the object will continue moving at whatever constant velocity it had reached, but it will no longer accelerate.

There are some nuanced exceptions in relativity or when dealing with fields, but in classical mechanics, the statement as written is fundamentally incorrect. -

Idealism in ContextUniversals are not generally associated with idealism. Berkeley rejected them, although Peirce’s objective idealism recognizes them.

-

The Mind-Created WorldThe schema you're laying out makes sense, and can clearly be useful in dividing up the conceptual territory, but would you want to argue that it's the correct use of "real" in metaphysics? — J

Sorry my remark about metaphysics was prompted by many of the comments made here about it, but you're right, it is a field that has made a comeback in current philosophy.

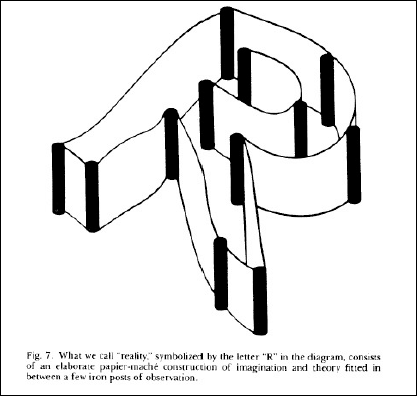

Consider this graphic from John Wheeler’s essay Law without Law:

The caption reads ‘what we consider to be ‘reality’, symbolised by the letter R in the diagram, consists of an elaborate paper maché construction of imagination and theory fitted between a few iron posts of observation’.

The “R” of reality is not given, but built from the accumulated record of acts of observation — each a scrap in the paper-mâché construction of the world.

My point about universals is that they are fundamental constituents of this ‘R’. I think Wheeler’s simile of ‘paper maché’ is a little misleading, as the tenets of physical theory are rather more ‘solid’ than this suggests. But regardless the elements of the theory are real in a different sense to its objects. They comprise theories and mathematical expressions of observed regularities. -

The Mind-Created WorldBut would you import it (designation of 'real') into a consideration of numbers, for instance? It seems like a bad fit. My contention is that, the more we enter metaphysics and epistemology, the less useful "real" is. — J

Would that be because metaphysics is generally considered archaic by modern philosophy?

I've posted an excerpt from Bertrand Russell on universals in the Idealism in Context thread which can be reviewed here:

Reveal]Consider such a proposition as 'Edinburgh is north of London'. Here we have a relation between two places, and it seems plain that the relation subsists independently of our knowledge of it. When we come to know that Edinburgh is north of London, we come to know something which has to do only with Edinburgh and London: we do not cause the truth of the proposition by coming to know it, on the contrary we merely apprehend a fact which was there before we knew it. The part of the earth's surface where Edinburgh stands would be north of the part where London stands, even if there were no human being to know about north and south, and even if there were no minds at all in the universe. ... But this fact involves the relation 'north of', which is a universal; and it would be impossible for the whole fact to involve nothing mental if the relation 'north of', which is a constituent part of the fact, did involve anything mental. Hence we must admit that the relation, like the terms it relates, is not dependent upon thought, but belongs to the independent world which thought apprehends but does not create.

This conclusion, however, is met by the difficulty that the relation 'north of' does not seem to exist in the same sense in which Edinburgh and London exist. If we ask 'Where and when does this relation ["north of"] exist?' the answer must be 'Nowhere and nowhen'. There is no place or time where we can find the relation 'north of'. It does not exist in Edinburgh any more than in London, for it relates the two and is neutral as between them. Nor can we say that it exists at any particular time. Now everything that can be apprehended by the senses or by introspection exists at some particular time. Hence the relation 'north of' is radically different from such things. It is neither in space nor in time, neither material nor mental; yet it is something [real].

It is largely the very peculiar kind of being that belongs to universals which has led many people to suppose that they are really mental. We can think of a universal, and our thinking then exists in a perfectly ordinary sense, like any other mental act. Suppose, for example, that we are thinking of whiteness. Then in one sense it may be said that whiteness is 'in our mind'. ...In the strict sense, it is not whiteness that is in our mind, but the act of thinking of whiteness. The connected ambiguity in the word 'idea', which we noted at the same time, also causes confusion here. In one sense of this word, namely the sense in which it denotes the object of an act of thought, whiteness is an 'idea'. Hence, if the ambiguity is not guarded against, we may come to think that whiteness is an 'idea' in the other sense, i.e. an act of thought; and thus we come to think that whiteness is mental. But in so thinking, we rob it of its essential quality of universality. One man's act of thought is necessarily a different thing from another man's; one man's act of thought at one time is necessarily a different thing from the same man's act of thought at another time. Hence, if whiteness were the thought as opposed to its object, no two different men could think of it, and no one man could think of it twice. That which many different thoughts of whiteness have in common is their object, and this object is different from all of them. Thus universals are not thoughts, though when known they are the objects of thoughts. — Bertrand Russell, The World of Uhiversals

Russell makes a simple but important point about universals: things like the relation “north of” or the quality “whiteness” are real, but they’re not located in space or time, and they’re not just mental events.

Here’s the gist of his argument in four steps:

[1] Independence from mind – The truth of “Edinburgh is north of London” doesn’t depend on anyone thinking it; it would hold in a mindless universe.

[2] Non-spatiotemporal status – ‘North of’ isn’t in either city, and it’s not in space or time like physical objects are.

[3] Act vs. object of thought – Thinking of whiteness is a mental act in time; whiteness itself is not the act but the object of that act.

[4] Universality preserved – If whiteness were just a thought, it would be particularized (your thought now, my thought then), and couldn’t be the same across different thinkers and times.[/quote]

I'll go back to the original contention: that numbers (and other abstracta) are real but not existent in the sense explained by Russell. Empiricism attempts to ground mind-independence in the empirical domain - situated in space and time, instrumentally detectable and measurable. But the reality of such objects are still necessarily contingent upon the act of measurment and the theories against which they're interpreted.

And furthermore, the ability to even conduct such observations itself depends on the grasp of intelligible relations which is itself a noetic or intellectual act. Whereas empiricism, with its equation of “mind-independent” with “detectable by instruments,” then treats the faculties which enable these abilities as if they are derivative from the processes they're investigating. And this, against the background of the methodological bracketing of the knowing subject and the structures of understanding. We end up with worldview that literally uses universals constantly (in mathematics, definitions, logical inferences) while denying their ontological standing. -

Idealism in ContextBertrand Russell has a chapter called World of Universals in his early Problems of Philosophy, which I often refer to.

Consider such a proposition as 'Edinburgh is north of London'. Here we have a relation between two places, and it seems plain that the relation subsists independently of our knowledge of it. When we come to know that Edinburgh is north of London, we come to know something which has to do only with Edinburgh and London: we do not cause the truth of the proposition by coming to know it, on the contrary we merely apprehend a fact which was there before we knew it. The part of the earth's surface where Edinburgh stands would be north of the part where London stands, even if there were no human being to know about north and south, and even if there were no minds at all in the universe. ... But this fact involves the relation 'north of', which is a universal; and it would be impossible for the whole fact to involve nothing mental if the relation 'north of', which is a constituent part of the fact, did involve anything mental. Hence we must admit that the relation, like the terms it relates, is not dependent upon thought, but belongs to the independent world which thought apprehends but does not create.

This conclusion, however, is met by the difficulty that the relation 'north of' does not seem to exist in the same sense in which Edinburgh and London exist. If we ask 'Where and when does this relation ["north of"] exist?' the answer must be 'Nowhere and nowhen'. There is no place or time where we can find the relation 'north of'. It does not exist in Edinburgh any more than in London, for it relates the two and is neutral as between them. Nor can we say that it exists at any particular time. Now everything that can be apprehended by the senses or by introspection exists at some particular time. Hence the relation 'north of' is radically different from such things. It is neither in space nor in time, neither material nor mental; yet it is something [real].

It is largely the very peculiar kind of being that belongs to universals which has led many people to suppose that they are really mental. We can think of a universal, and our thinking then exists in a perfectly ordinary sense, like any other mental act. Suppose, for example, that we are thinking of whiteness. Then in one sense it may be said that whiteness is 'in our mind'. ...In the strict sense, it is not whiteness that is in our mind, but the act of thinking of whiteness. The connected ambiguity in the word 'idea', which we noted at the same time, also causes confusion here. In one sense of this word, namely the sense in which it denotes the object of an act of thought, whiteness is an 'idea'. Hence, if the ambiguity is not guarded against, we may come to think that whiteness is an 'idea' in the other sense, i.e. an act of thought; and thus we come to think that whiteness is mental. But in so thinking, we rob it of its essential quality of universality. One man's act of thought is necessarily a different thing from another man's; one man's act of thought at one time is necessarily a different thing from the same man's act of thought at another time. Hence, if whiteness were the thought as opposed to its object, no two different men could think of it, and no one man could think of it twice. That which many different thoughts of whiteness have in common is their object, and this object is different from all of them. Thus universals are not thoughts, though when known they are the objects of thoughts.

Russell makes a simple but important point about universals: things like the relation “north of” or the quality “whiteness” are real, but they’re not located in space or time, and they’re not just mental events.

Here’s the gist of his argument in four steps:

-

[1] Independence from mind – The truth of “Edinburgh is north of London” doesn’t depend on anyone thinking it; it would hold in a mindless universe.

[2] Non-spatiotemporal status – ‘North of’ isn’t in either city, and it’s not in space or time like physical objects are.

[3] Act vs. object of thought – Thinking of whiteness is a mental act in time; whiteness itself is not the act but the object of that act.

[4] Universality preserved – If whiteness were just a thought, it would be particularized (your thought now, my thought then), and couldn’t be the same across different thinkers and times. -

On emergence and consciousnessI think panpsychism fails to explain the unity of experience; therefore, it is not acceptable. — MoK

I agree with you! -

The Christian narrativeTo be a substance (thing-unit)... — Count Timothy von Icarus

I think this is a misrepresentation from the outset. Isn't this just exactly what Heidegger criticized about the objectification of metaphysics? The original Greek term was nearer in meaning to 'being' than 'thing', and a great deal is lost in equiviocating them. 'Being' is a verb. -

On emergence and consciousnessI included that, because he does come to that conclusion in the essay I presented of his. But I think his arguments against emergence were more important, and also noted that he doesn't develop this idea in his later work.

-

The Christian narrativeI'd be happy to consider alternatives - if they could be given clearly. — Banno

The positivists have a simple solution: the world must be divided into that which we can say clearly and the rest, which we had better pass over in silence. But can anyone conceive of a more pointless philosophy, seeing that what we can say clearly amounts to next to nothing? If we omitted all that is unclear, we would probably be left with completely uninteresting and trivial tautologies. — Neils Bohr

Wayfarer

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum