-

The Question of CausationNo, by fact it is not the same Wayfarer. Same being identical. Are a pair of twins the same? Similar, but not identical. Again, lumping things into a category is not the same as saying that all the things in that category are identical in reality. I can define sheep, but there is no one sheep that is identical to any other sheep. — Philosophim

If your philosophy cannot allow for the existence of a song, and copywright to it, then all I can say is that it has a serious deficiency.

there is no one sheep that is identical to any other sheep. — Philosophim

Regardless, it's different from everything except another sheep. It's not a camel, or a llama.

I'm merely asking for a clear definition of something non-physical — Philosophim

Melodies, as discussed. Numbers, laws, conventions, chess. There are thousands of these general kinds of things that are grasped by the mind (but not by 'neural activity'). -

The Question of CausationNo, the melody is not the same. It is similar, which is a very distinct difference. If I play the song in two different places at the same time, they are not the same. The physical composition of the instrument, the physical composition and actions of the player, and the very air and accoustics the song travels two are different. We summarize them as 'the same song' for convenience and summary in communication. But when we break it down and need to look at it in detail, our summary is not representative of some 'form' that exists outside of physical reality. — Philosophim

Incorrect. The melody IS the same. RIght now, my 10-month-old grand-child is playing with an electronic toy which is playing the song My World is Blue. It is the same melody. There are many arrangements of this song on Spotify and Apple Music which are the same melody but arranged with different instruments and vocalists. If I tried to put out a song with that melody, I would rightly be sued for copyright infringement. This happens frequently, and quite often the similarity is not even obvious.

I am very open to the existence of something non-physical. I am open to a God existing. A magical unicorn. I am not being sarcastic or intending to insult. I LOVE thinking of wonderful things. — Philosophim

The problem is, that is not at all what philosophy of mind believes by the immaterial or non-physical. The fact you can only conceive of alternatives to the physical in terms of magical unicorns indicates a misunderstanding of the subject. -

The Question of CausationDon't forget about property dualism. :grin: Matter has a non-physical property. — Patterner

Which nobody can specify.

Its when you start to think they (mental processes) exist apart from physical processes as some independent entities that you run into trouble. — Philosophim

They're still physical, but are designated 'mental'. How can that be distinguished from straight-ahead physicalism? -

The Question of CausationAre informational objects causally related in the same sense that physical objects are? If so, how. I not how so? — I like sushi

I think the thread is about 'mental causation' - can mind, if it is non-physical, cause physical effects? It seems obvious that it does, but it's a question of great controversy in academic philosophy, because of its commitment to metaphysical naturalism. And naturalism generally assumes a physicalist outlook. 'Non-reductive physicalism' is now popular - it posits that while everything is physical, not all physical phenomena can be reduced to or explained by basic physical laws and properties. It accepts that the world is fundamentally physical but denies that higher-level phenomena, like mental states or biological processes, are merely identical to or fully explained by the fundamental physical level. Donald Davidson who has been mentioned and about whom Banno knows a lot, is an example of non-reductive physicalism.

The alternative seems to be dualism - that mind is one kind of substance and matter another. That is the implication of Descartes' dualism, but it's not much accepted nowadays. Or idealism - that mind is somehow fundamental, which is hardly accepted by academic philosophy at all. But in any case it's a more complicated problem than it seems. -

The Mind-Created WorldAnd Kant concluded that Ultimate Reality (noumenon) is fundamentally unknowable to humans. He seems to be implying that philosophers are just ordinary humans, who have made it their business to guess (speculate) about non-phenomenal noumena. — Gnomon

It’s more a question of intellectual humility - no matter how much we know there’s still a sense in which we lack insight into how things really are. Human knowledge is necessarily incomplete, in that sense.

I get quite confused about whether the aim is to end mental activity or give up one's attachment to it and in it. Both of these are hard to distinguish from ceasing to live. As to the epoche, it is clearly a cousin or something. You see, presented with this relationship, my first thought is to clarify the differences, and there are plenty of those.

You probably want to say "Shut up and meditate". — Ludwig V

I've given up on meditation. I attempted to practice it for many decades, having a disciplined routine of getting up an sitting in a customary 'zazen' position for anything up to 45 minutes (which was often excruciating, but then that's part of it.) About five years ago, the practice just fell away, and besides, I was never a disciplined yogi. My lifestyle remains pretty 'bougie' (a word I picked up from my adult son). I've tried to return to it a few times, but I can no longer assume the customary posture, and just sitting on a chair seems lacking. Due to books like 'The Miracle of Mindfulness', it's presented as a panacea, the end to all woes. But if you read the original text of mindfulness meditation, the Satipatthana Sutta, you will see that in context it is a very exacting discipline, conducted as part of a regimen of discipline and lifestyle (in which mindfulness, sati, is one leg of a tripod, the others being morality, sila, and wisdom, panna.)

All that said, something remains. My initial discovery of meditation involved a confluence of reading and practice which really did trigger some epiphanies. I used to see visiting teachers some of whom really did precipate awakening experiences. I was enrolled in comparative religion and studying what I understood as the enlightenment vision, and I really do believe that this is real. (Believing that is not necessarily the same as believing in God.) I have always had the sense of having, in some very distant past, an understanding which was the most important thing in life, the only thing that really needed to be understood. I came to understand this as an intimation of what Vedanta calls self-realisation although I make no claim to have realised a higher state. More like a glimpse or what Plato calls an anamnesis, an un-forgetting of something vital once known.

I can understand "emptiness" as meaning something like the idea that things and events do not, in some sense, have the significance or importance or weight that common sense attributes to them. That would enable one to abandon desire. (That would be a parallel to the stance that Western scientists and phenomenologists attempt.) But the difficulty with that is that it makes compassion hard to understand. — Ludwig V

Excellent insight and completely true. That is why Mayahana Buddhism stresses that emptiness (śūnyatā) and compassion (metta-karuna) are like the two wings of a bird - the bird needs both to take flight.

Scientific objectivity started, in Medieval thought, as a form of philosophical detachment, but it diverges from it, due to the emphasis on the 'primacy of the measurable', which we've already discussed. That is the subject of one of my Medium essays Objectivity and Detachment. -

The Question of CausationOf course its physical. Let take music for example. The physical notes I write on a page. The physical intstrument I play it with. The physical ears that hear it. Are you claiming that if we got rid of all of these physical things that the information of music would be floating out in space somewhere? — Philosophim

A melody can be represented in musical notation or binary code. It can be engraved in metal or copied on to paper. Then it can be played back on different instruments or through digital reproduction. In every case the physical medium is different but the melody is the same. So how then can the melody be described as physical?

I clearly told you I don't associate with the physicalist position. — Philosophim

Every post of yours that I’ve read assumes physicalism. Maybe because you assume that everything is physical, and don’t understand how anything can described in other terms, then you don’t understand what physicalism is, because you think there is nothing outside the physical with which to compare it. -

The Question of CausationIf I were watching a computer play (chess against) another, which part is physical? — Hanover

The medium is physical; the game is formal; the meaning or purpose (like “this move is a blunder”) is relational or noetic. -

Language of philosophy. The problem of understanding beingI only posted it - I post this passage often - because what you said here:

there is no way to differentiate rest and motion. (There's nowhere for an observer to observe from.) — Ludwig V

Isn't it making the same point? Anyway, it's a digression, let's leave it. -

Language of philosophy. The problem of understanding beingFor a universe that consists of a single body, there is no way to differentiate rest and motion. (There's nowhere for an observer to observe from.) — Ludwig V

The problem of including the observer in our description of physical reality arises most insistently when it comes to the subject of quantum cosmology - the application of quantum mechanics to the universe as a whole - because, by definition, 'the universe' must include any observers.

Andrei Linde has given a deep reason for why observers enter into quantum cosmology in a fundamental way. It has to do with the nature of time. The passage of time is not absolute; it always involves a change of one physical system relative to another, for example, how many times the hands of the clock go around relative to the rotation of the Earth. When it comes to the Universe as a whole, time looses its meaning, for there is nothing else relative to which the universe may be said to change. This 'vanishing' of time for the entire universe becomes very explicit in quantum cosmology, where the time variable simply drops out of the quantum description. It may readily be restored by considering the Universe to be separated into two subsystems: an observer with a clock, and the rest of the Universe.

So the observer plays an absolutely crucial role in this respect. Linde expresses it graphically: 'thus we see that without introducing an observer, we have a dead universe, which does not evolve in time', and, 'we are together, the Universe and us. The moment you say the Universe exists without any observers, I cannot make any sense out of that. I cannot imagine a consistent theory of everything that ignores consciousness...in the absence of observers, our universe is dead'. — Paul Davies, The Goldilocks Enigma: Why is the Universe Just Right for Life, p 271 -

Language of philosophy. The problem of understanding beingA fundamental ontological distinction is between beings and things. I’ve had many an argument about it. That was the context in which I was sent the Kahn paper.

-

Language of philosophy. The problem of understanding beinga static being is like the Buddha in stillness. — Punshhh

although the Buddha said there is nothing not subject to change -

Language of philosophy. The problem of understanding beingA classic paper you might find of interest is The Greek Verb 'To Be' and the Problem of Being, Charles S. Kahn.

-

Does anybody really support mind-independent reality?Arguably so, but being thought of doesn't change it to be affected by thought. — noAxioms

I’m not saying that an object is ‘affected by thought’. I’m thinking of the Statue of Liberty right now which will make no difference to it whatever. The question of mind independence that is of interest to me, is the sense in which the world exists independently of the mind. -

The Mind-Created WorldObviously, the human mind is doing the measuring in terms of locally conventional increments. But the point is that the physical universe existed long before metaphysical minds. — Gnomon

The point I'm pressing is the distinction between the empirical facts of science, which I'm not disputing in the least, and the grounding of these facts in the philosophical and scientific framework through which we understand them. That argument is that our knowledge of the physical universe (world, object) is not knowledge of the universe as it is in itself but of how it appears to us.

Western culture has a preoccupation with finding the primary ground or fundamental state, being or thing, but nowadays conceived as first in series of material and efficient causes. I'm not pursuing an understanding of a first cause in that sense (whether scientific or theistic).

That’s why I’ve referred to Kant, and to Husserl’s critique of the “natural attitude.” What I’m exploring isn’t an alternative physical theory — it’s a philosophical inquiry into the possibility of meaning, including the meaning of physical theories. And also an argument against the sense that science sees the world as it truly is outside any perspective.

what must be the case for such experience to be possible?

— Wayfarer

I'm afraid I'm prone to afterthoughts. Our problem can be thought of as a kind of antinomy. — Ludwig V

Precisely! A couple of pages back I quoted a long passage from Schopenhauer which says exactly that (this post).

But how does this fit with Buddhism and meditation? — Ludwig V

Because a major point of mindfulness is to understand how the mind creates your world. This is a snippet from an essay on 'emptiness' in Buddhist meditation. It means, among other things, empty of presuppositions or inferred meanings.

Emptiness is a mode of perception, a way of looking at experience. It adds nothing to and takes nothing away from the raw data of physical and mental events. You look at events in the mind and the senses with no thought of whether there's anything lying behind them.

This mode is called emptiness because it's empty of the presuppositions we usually add to experience to make sense of it: the stories and world-views we fashion to explain who we are and the world we live in. Although these stories and views have their uses, the Buddha found that some of the more abstract questions they raise — of our true identity and the reality of the world outside — pull attention away from a direct experience of how events influence one another in the immediate present. Thus they get in the way when we try to understand and solve the problem of suffering.

Ultimately in the Buddhist analysis the cause of suffering is clinging or holding to possessions, sensations, ideologies - attachment, generally speaking. This is an incessant mental activity. Notice also the similarity to the phenomenological epochē or suspension of judgement.

I'm in pursuit of a more nuanced approach to reality vs appearance. — Ludwig V

As am I! The main point being that in the early modern scientific worldview, the division of subject and object was fundamental but also concealed. Kant and later, phenomenology, seeks to make explicit this division and to re-instate the role of the subject in the construction of knowledge.

I get stuck on the idealism — Ludwig V

There is a school of Mahāyāna Buddhism (the form of Buddhism common to Tibet and East Asia, distinct from the Theravada schools of southern Asia) called Yogācāra or Vijñānavāda. This is usually translated as 'mind-only Buddhism'. It is by no means universally accepted in Buddhism (and not at all by Theravada Buddhism). But it is philosophically rich and many comparisions have been made between it, and Berkeleyian and Kantian idealism. You can find the Wikipedia entry here. -

How do you think the soul works?Does, per Kant, knowledge only arise because of the mind? Isn’t is also knowledge of some thing? — Fire Ologist

Mind is the faculty of knowledge. Consciousness is always consciousness of... which was one of the basic observation of phenomenology. (However Indian philosophy also understands states of 'contentless consciousness' arising through dhyana (meditation)).

The point I was making was in response to the question 'what kind of thing is the soul (mind)?' which I say is a nonsensical question. Soul or mind is 'that which knows'.

The passage I mentioned from the Upaniṣads (philosophical scriptures of Vedanta) elaborates on this in vivid terms.

The subject of the dialogue is the nature of Ātman (Sanskrit): commonly translated as soul or self, Ātman is the innermost essence or enduring subject of experience. In many Indian traditions, especially Vedānta, it refers to the true self, distinct from the body, mind, and ego. Unlike the Western notion of an immortal individual soul (e.g., in Christian theology), ātman is often conceived as identical with (Advaita Vedānta) or ultimately unified in (qualified or dualistic Vedānta) Brahman, the ground of Being.

Below is an edited excerpt from a dialogue between the sage Yajnavalkya who is the principal voice in the Upaniṣad, and a questioner, who is trying to elicit information about the ātman.

You have only told me, this is your inner Self in the same way as people would say, 'this is a cow, this is a horse', etc. That is not a real definition. Merely saying, 'this is that' is not a definition. I want an actual description of what this internal Self is. Please give that description and do not simply say, 'this is that'. Yājñavalkya says: "You tell me that I have to point out the Self as if it is a cow or a horse. Not possible! It is not an object like a horse or a cow. I cannot say, 'here is the Ātman; here is the Self'. It is not possible because you cannot see the seer of seeing. The seer can see that which is other than the Seer, or the act of seeing. An object outside the seer can be beheld by the seer. How can the seer see himself? How is it possible? You cannot see the seer of seeing. You cannot hear the hearer of hearing. You cannot think the Thinker of thinking. You cannot understand the Understander of understanding. That is the Ātman."

Nobody can know the Ātman inasmuch as the Ātman is the Knower of all things. So, no question regarding the Ātman can be put, such as "What is the Ātman?' 'Show it to me', etc. You cannot show the Ātman because the Shower is the Ātman; the Experiencer is the Ātman; the Seer is the Ātman; the Functioner in every respect through the senses or the mind or the intellect is the Ātman. As the basic Residue of Reality in every individual is the Ātman, how can we go behind It and say, 'This is the Ātman?' Therefore, the question is impertinent and inadmissible. The reason is clear. It is the Self. It is not an object.

Ato'nyad ārtam: "Everything other than the Ātman is stupid; it is useless; it is good for nothing; it has no value; it is lifeless. Everything assumes a meaning because of the operation of this Ātman in everything. Minus that, nothing has any sense". Then Uṣasta Cākrāyana, the questioner kept quiet. He understood the point and did not speak further. — Brihadaranyaka Upaniṣad trs Swami Krishnananda

This is why, in this tradition, asking what kind of thing the ātman or soul is, amounts to a category error. It is not a thing among things, but that in virtue of which anything appears as a thing at all. -

Evidence of Consciousness Surviving the BodyThe mechanics of cognitive externalism are generally considered to be physical — sime

That’s true if one assumes from the outset that “the physical” is by definition causally closed and fully intersubjective. But that’s precisely the point at issue. To say that cognitive externalism operates—as in your example of a robot using landmarks—is to presume a mechanistic model where all cognitive content is traceable to physical causation. Yet the eels returning to ancestral ponds doesn’t conform neatly to that model as it suggests information persistence and access without clear causal pathways, at least not in the standard physicalist sense. But then, I suppose the definition of physical can be adjusted to suit such anomalies. It’s one of the attributes which gives it such persistence.

I cannot remember what I ate for breakfast on this very day last year, and yet this doesn't seem to matter with regards to anyone's identification of me as being the "same" person from last year up to the present. — sime

t’s not a question of personal identity. The issue isn’t whether episodic memory is necessary for self-continuity, but whether our current conceptual framework is adequate to accommodate the kinds of anomalous phenomena reported in NDEs—particularly veridical perceptions occurring during states of minimal or absent brain activity. Even if we remain agnostic about interpretation, such cases are at least analogically suggestive of cognitive processes that are not easily reducible to brain function alone. -

Evidence of Consciousness Surviving the BodyThe idea that NDEs behave as a sixth sense is actually in conflict with the idea that NDEs are evidence of Cartesian dualism; for how are the experiences of a disembodied consciousness supposed to be transferred to the physical body as is necessary for the wakeful patient to remember and verbally report his NDE? — sime

That’s a valid question—but perhaps what’s really at stake is our concept of what counts as “physical” and how information is encoded and retrieved in living systems. Even in animals, we find forms of memory and orientation that are difficult to explain within current neurobiological or straightforwardly genetic models. Take, for example, pond eels in suburban Sydney that migrate thousands of kilometers to spawn near New Caledonia—crossing man-made obstacles like golf courses along ancestral routes. After years in the open ocean, their offspring return to the very same suburban ponds (ref). It’s hard to see how this kind of precise memory is passed on physically, and yet it plainly occurs.

Even more dramatically, the research of psychiatrist Ian Stevenson, though often met with skepticism, presents another challenge. Over several decades, he documented more than 2,500 cases of young children recalling specific details of previous lives with the details being validated against extensive documentary evidence and witness testimony. Often what they said was well beyond what the children could plausibly have learned by ordinary means and conveyed knowledge of people and events that they could only have learned about from experience. Stevenson was cautious in drawing conclusions - he never claimed that his research proved that reincarnation occured, but that these cases showed features suggestive of memory transfer beyond what conventional physical mechanisms could explain.

Both examples—the eels and the children—don’t necessarily prove anything metaphysical, but they do suggest that our current physicalist assumptions may be too narrow. Near-death experiences might be pointing in the same direction: not toward disembodiment in a Cartesian sense, but toward a broader view of mind and memory that isn't strictly brain-bound. -

Measuring Qualia??Merleau Ponty writes: “For what exactly is meant by saying that the world existed prior to human consciousnesses? It might be meant that the earth emerged from a primitive nebula where the conditions for life had not been brought together. But each one of these words, just like each equation in physics, presupposes our pre-scientific experience of the world, and this reference to the lived world contributes to constituting the valid signification of the statement. — Excerpt from the Blind Spot Adam Frank, Marcelo Gleiser, Evan Thompson

-

The Mind-Created WorldIn the 17th century, scientists foreswore the hidden realities of the (Aristotelian) scholastics. The function of science was to understand the realities that we actually experience - except those things that we experience that were not amenable to mathematical treatment - but that was treated as a marginal note. — Ludwig V

The point of the Galilean method was that it was defined in terms of primary and secondary attributes of matter, instead of Aristotelian (meta)physics and its 'natural tendencies'. As well as being inextricably connected with the geocentric cosmology. This is all history, of course.

Galileo's primary qualities, also endorsed by Locke, were those attributes of matter such as mass, force, velocity, inertia and so on - which were amenable to mathematical measurement and representation. That was the essence of the 'new physics' that represented a complete break from the earlier model.

For Galileo, how things appeared, on the other hand - color, taste, scent, and so on - were assigned to the mind of the individual. So here was a dualism of a completely different kind to what you're suggesting - between the measurable attributes of bodies, understood as objectively real, the same for all observers, as opposed to how they appeared, which was assigned to the individual mind, and so 'subjectivised'. This is the genesis of the 'Cartesian division' which has been subject to much commentary. Thomas Nagel put it like this:

The modern mind-body problem arose out of the scientific revolution of the seventeenth century, as a direct result of the concept of objective physical reality that drove that revolution. Galileo and Descartes made the crucial conceptual division by proposing that physical science should provide a mathematically precise quantitative description of an external reality extended in space and time, a description limited to spatiotemporal primary qualities such as shape, size, and motion, and to laws governing the relations among them. Subjective appearances, on the other hand -- how this physical world appears to human perception -- were assigned to the mind, and the secondary qualities like color, sound, and smell were to be analyzed relationally, in terms of the power of physical things, acting on the senses, to produce those appearances in the minds of observers. It was essential to leave out or subtract subjective appearances and the human mind -- as well as human intentions and purposes -- from the physical world in order to permit this powerful but austere spatiotemporal conception of objective physical reality to develop. — Mind and Cosmos, Pp 35-36

I can just about get my head around "conditions of the possibility of knowledge". I've never had a firm grip on what metaphysics is supposed to be. My philosophical education was most remiss about that. — Ludwig V

I understand that. I was introduced to Kant via an unorthodox route, through a 1950's book called The Central Philosophy of Buddhism, T.R.V. Murti. It has extensive comparisons with the European idealists and the 'Middle Way' (Madhyamaka) philosophy of a semi-legendary figure called Nāgārjuna (memorialised as 'the second Buddha', living in around the first century C.E. although dates are unknown.) Murti's book as fallen out of favour for being overly eurocentric (Murti having been Oxford-trained.) But it was one of those books which for me was a profound part of my spiritual and philosophical formation. It enabled me to see the link between meditative awareness and Kantian idealism.

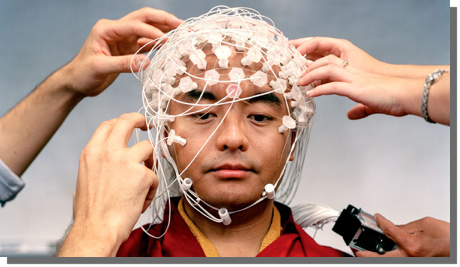

Buddhism has always been aware of the way the mind creates (or constructs) our world. That is why there has been extensive consultation between contemporary Buddhist scholarship, psychologists, and neuroscience (see The Mind-Life Institute). But Buddhism doesn't rely on scientific apparatus to attain its insights - it relies on highly-trained awareness to discern these insights about the constructive activities of the mind – although, that said, neuroscientists have devoted resources to exploring the effects of meditation on the mind:

Mingyur Rinpoche participating in experimental analysis of meditation

An AI-generated description of the parallels between Kant and Buddhist philosophy:

Murti draws a strong parallel between Nāgārjuna’s Madhyamaka philosophy and Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason. Both begin with the insight that our experience of the world is structured by the mind and that we never encounter reality as it is in itself. For Kant, this leads to the distinction between phenomena (what appears to us) and noumena (the in-itself), showing that the categories of the understanding shape experience. Nāgārjuna similarly shows that all concepts and views are dependent and relational—empty of inherent nature or intrinsic reality (śūnyatā). Where Kant outlines the transcendental conditions of experience, Nāgārjuna critiques all fixed views, including metaphysical and epistemological views, to reveal the dependently-originated and non-substantial nature of all appearances.

I know there's a lot to take on there - both Kant and Nāgārjuna's texts have engendered huge volumes of commentary - but the key takeway is that both analyse the role of cognition in the construction of experience.

From the reactions to this OP, I'm realizing that it's a very difficult argument to present clearly. Broadly speaking, it's a transcendental argument—that is, it begins not with claims about what exists, but with an analysis of experience and cognition, and then asks: what must be the case for such experience to be possible? (This is why it is epistemological rather than ontological.)

One of the key implications is that we are not passive observers of a pre-given world, but active participants in the constitution of the world as we know and live it. To grasp this, we have to reflect on the role our own minds play in shaping the structures of experience—our world of lived meanings. This is precisely where phenomenology enters the picture, since it offers a disciplined way of examining experience from within, rather than assuming it as something merely external or objective. Hence the requirement for a changed perspective, not simply the acquisition of some propositional knowledge.

But that's a larger discussion. I've said enough for now.

Yes, according to modern cosmology, the physical universe existed for about 10 billion years without any animation or "cognition" : just malleable matter & causal energy gradually evolving & experimenting with new forms of being ; ways of existing. — Gnomon

Where does the measure 'years' originate, if not through the human experience of the time taken for the Earth to rotate the Sun? -

How do you think the soul works?But the positive contribution here is that, in order to discuss what a mind is, the notion of reflection has to be incorporated. There is something unique going on that is mind, and in every mental happening, there is a reflection involved. — Fire Ologist

Plainly I can think about my mind, or mind in general. I can reflect on my inner states and those that others must have. But that doesn’t undermine the point that the mind is not an object, except for in the metaphorical sense of it being an ‘object of thought’ - but then, that applies to anything we think about. The second point is reflexivity, that the mind is that which thinks, not itself an object. There is a metaphor in the Indian texts, 'It is never seen but is the seer; it is never heard but is the hearer; it is never thought of but is the thinker; it is never known but is the knower'. I think this is an elementary fact, and that the unknowable nature of mind is something it is important to acknowledge and be aware of. In other words, recognizing the mind’s unknowable nature—its status as that which knows, rather than something known—is to recognize the ground of experience, the source from which knowledge arises. To mistake it for an object among objects is to lose sight of the subjectivity that makes knowledge possible in the first place. -

The Origins and Evolution of Anthropological Concepts in ChristianityYou have your work cut out for you, that’s for sure.

-

The Origins and Evolution of Anthropological Concepts in ChristianityThe contemporary assertion of the dualistic nature of humanity in a spiritual context, positing spirit and body as separate entities, appears to modern individuals as something commonplace, self-evident, and taken for granted. In their popular interpretations, a significant portion of Christian denominations lean toward dualism, viewing the body as a temporary vessel for an immortal spirit, which, after the completion of earthly life, continues to exist independently or is reborn in a new body. — Astorre

One point I would make about this is in respect of the cultural influence of René Descartes. As you will know, he is generally introduced to philosophy students as 'the first modern philosopher'. Descartes, along with Newton, Galileo, and some other key figures, were principals of ;the scientific revolution.

Cartesian dualism, as you will also know, posits that man is a composite of two substances, res extensa, unthinking extended matter, and res cogitans, immaterial thinking soul or mind. This dualistic model has been hugely influential in modern culture. But it was an awkward marriage trom the start - Descartes himself was never really able to explain how two radically different substances interact, positing it was through the pineal gland, but hardly going into any detail.

Then there's the added confusion around the word 'substance'. As you might know, 'substance' in philosophy means something quite different from 'substance' in everyday use. The philosophical term originated with the Latin translation of Aristotle's 'ouisia', which is much nearer in meaning to 'being' than to our word 'substance'. Essentially, for Aristotle, substance is the underlying reality that persists through change. A substance is a combination of matter (the potential to be something) and form (the actual, defining essence of that thing).The translation was actually 'substantia', meaning, that of which attributes can be predicated.

So the upshot of all of this, was that Western culture adopted this rather oxymoronic conception of 'spiritual substance' or 'thinking substance'. Whereas, the ability to manipulate analyse and exploit material substance, the main occupation of science and engineering, proceeded brilliantly. So when modern people talk about 'dualism', it is usually something like Cartesian dualism that they have in mind, even if they don't know any details of how that originated or really what it means, And besides, they will say, the idea of 'thinking substance', which they will equate with 'soul', is an outmoded concept. Everyone knows, they will say, that mind is what the brain does, the credo of scientific materialism.

It should also be clear that the dualism of matter and form (Aristotle) is intrinsically more intelligible than Descartes dualism of matter and mind. To this day, hylomorphism remains a live option in philosophy, whilst Cartesian dualism is generally regarded as untenable. They're very different conceptions.

None of that is relevant to the origin of Christian conceptions of the soul but probably relevant as an influence in the modern period. -

The Origins and Evolution of Anthropological Concepts in Christianity'Holism' is a modern word. It was coined by Jan Smuts early in the 20th c. I don’t think I’ll comment on the other matters but will follow the thread.

-

The Origins and Evolution of Anthropological Concepts in ChristianityThese differences may be related to the influence of Platonism on Western Christianity — Astorre

I had rather thought that Aristotle was the greater influence on Western (Catholic) Christianity due to the rediscovery of his works from the Islamic world. And that Platonism was more of an influence on Orthodox Christianity through Pseudo-Dionysius and other sources. Although it’s true that Plato is writ large in all of this. But I once put this to an Orthodox father and he was in agreement. -

How do you think the soul works?It is a matter of fact that the mind is not an object in any sense other than the metaphorical, such as ‘the object of the argument’, ‘the object of the question’.

-

How do you think the soul works?My claim was the mind is not a thing. Doesn't mean it's nothing. But it's not a thing, it's not an object. Your 'experience of the mind' is not an experience at all mind is that to whom experiences occur, that which sees objects, and so forth. It is not itself an object. That's one of the things that makes philosophy of mind such a big and elusive topic.

-

The Mind-Created WorldSure it's a project. I enrolled late at University in the second half of my twenties, and ended up doing a BA and MA hons in philosophy and related subjects. I have nothing external to show for it, never managed to make anything much from it, but I'm still pursuing it.

-

The Mind-Created WorldThe irony with the situation between Wayfarer and myself is that I am very familiar with all the arguments he presents, — Janus

Well, I want to get this straight. You've heard them many times, but I say you don't understand them. Take this latest exchange - it began with:

we know that the cosmos was visible prior to the advent of percipients, otherwise there never would have been any percipients. — Janus

This is a misrepresentation. The reason you say this is 'repetitive' is because you (and many others) misrepresent what is being said over and over again, to which I try and respond. In this case, I copied a couple of paragraphs from the original post, and then added commentary to the effect that it is not being argued that there was no universe prior to observers. So we get to:

An unfortunate deductive error inferring from our inability to say with certainty what kind of existence unperceived objects have to a conclusion that there could be no such actual existence, and that saying there is any such existence is incoherent. It's called 'confusing oneself with a truism'; the truism being that it is only minds that can know anything. — Janus

I say: “We can't say what existence means apart from mind.”

And you interpret as:

“Nothing existed before minds.”

The question I’m raising is not whether the universe existed, but what it means to say so. That is: what conditions make such a claim intelligible at all? When you say “the cosmos was visible prior to the advent of percipients,” you're smuggling in a category — visibility — that only has meaning within the context of experience. That’s the point I keep returning to.

You dismiss this as a “confusion with a truism” — that “only minds can know.” But this isn't about knowledge in the empirical or factual sense. It's about the conditions for meaningful discourse — the structure that allows us to form concepts like “universe,” “visibility,” or “existence” in the first place. I’m not making a deductive claim about what did or didn’t exist. I’m making a transcendental claim about what makes it possible to talk about existence at all.

To be clear: I’m not arguing that the universe didn’t exist before percipients. I’m arguing that the very concept of the universe — including any claims about its being — is bound to the framework of cognition. That’s not speculative metaphysics. It’s critical philosophy — and it was precisely this confusion that Kant sought to untangle.

The “actual existence” which you say must have pre-existed observers is exactly what’s at issue. I’m not denying the reality of the universe prior to observation — I’m saying that what it is, apart from any possible mode of perception, conception, or representation, is not something that science can tell us, because science already presupposes intelligibility, structure, and observation. That is Kant's 'in itself' - to which I add, it neither exists nor doesn't exist. Nothing can be said about it.

Of course we can reconstruct the early universe. I’m not contesting any of that. But all such reconstructions take place within the space of reason and inference — they’re appearances, structured by theory, observation, and mathematical representation. That’s not a flaw — it’s the condition of knowledge. But it does mean that the thing-in-itself — the “actual existence” prior to appearance — remains transcendent with respect to what science can access.

That’s the critical point: science gives us knowledge of appearances, not of reality unconditioned by perspective. When we forget this distinction, we turn methodological naturalism into a metaphysical doctrine — and mistake the limits of our mode of knowing for the limits of what is.

So — this is not “an unfortunate deductive error.” It’s a position foundational to a great deal of contemporary philosophy, especially in European traditions, though less so in the Anglo-American analytic stream.

There’s an online journal, Constructivist Foundations, which is an international, peer-reviewed e-journal dedicated to the study of constructivist and enactive approaches across philosophy, cognitive science, second-order cybernetics, neurophenomenology, and non-dualizing thought. I don’t have the academic credentials to make the cut in a journal of that kind, but I’d suggest that the core argument of Mind-Created World would be regarded as fairly stock-in-trade in that context — not a mistake, but a well-recognized philosophical position.

So I'd appreciate it if you might acknowledge that I'm not 'repeating the same mistake ad nauseum', as I don't think I am.

I don't have an agenda - I have an interest in recovering what I think is the meaning of philosophy proper, which is not at all obvious, and very difficult to discern. I say that philosophical and scientific materialism is parasitic upon philosophy proper. But the times, they are a'changin. -

The Mind-Created WorldI've reflected recently on how much I've learned on this forum - even from you! I'd never heard of Davidson or Austin or the other anglo analyticals before. Likewise Apokrisis and biosemiotics - I've read a lot about that now. Joshs has taught be a lot about phenomenology. This comes mainly from following up what they and others have said. It also comes from disagreements - when others disagree with your contributions, it can be a great learning opportunity, provided they're grounded in a genuine understanding.

Of course not every thread and every contributor is an opportunity for learning, but overall and for a public forum, I think thephilosophyforum.com has a good reputation. -

The Mind-Created WorldNot all the exchanges in this thread have been acrimonious, in fact they're the minority. Ludwig and I have managed to negotiate a pretty detailed conversation without it departing from civility, likewise for many other contributors. I'm not inclined to bend over backwards to posters who frequently engage in ad hominems and who are obviously antagonistic.

As far as being dogmatic is concerned, please be so kind as to indicate where you think this shows up in the OP. -

The Mind-Created Worldif you don't agree then you must not have understood" — Janus

But you clearly don't understand. Your arguments don't display a proper grasp of the issues. I've tried for years to explain ideas to you, to be met first with incomprehension, then with invective, and then with insults. So I generally ignore your remarks, a practice I will now resume. -

The Mind-Created WorldNot at all! Very much enjoying the forum at the moment, there are many very interesting discussions, and I'm learning a lot.

-

Does anybody really support mind-independent reality?But you beg the question, which is whether speaking of something affects it. An obvious question is, "In what way is it affected". — Ludwig V

@Mww replied for me.

Remember this thread started in part with

The Principle of Counterfactual Definiteness (PCD) asserts "the ability to assume the existence of objects, and properties of objects, even when they have not been measured". Efforts have been made to demonstrate say the existence of a photon 'in flight', only to come up empty. Photons only exist in the past of the event at which they are measured.

One of many such apparent paradoxes in quantum physics - which is, after all, supposed to be the science of fundamental particles. -

How do you think the soul works?Quite right. It's a lovely word, regardless of whether it's fashionable or not. I was most impressed by a 1996 Tom Wolfe essay, Sorry but your Soul Just Died, when I first started posting to forums - about neuroscientific explanations of mind and their existential implications.

-

The Mind-Created WorldThere's no use trying to explain it to those without sufficient education to understand it.

-

How do you think the soul works?I have my mind here right now in front of me. — T Clark

Speaking figuratively, of course. -

The Mind-Created WorldDoes Phenomenology successfully bridge over the spooky abyss of Spiritualism? — Gnomon

Husserl was never overtly 'spiritual' (whatever that means) but some say his emphasis on the transcendental aspects of phenomenology became somewhat too idealist later in life. Many of his successors, specifically Heidegger (with whom he had a somewhat fraught relationship) were much less sympathetic to that dimension of Husserl's thought, and more concerned with being-in-the-world.

One of the online articles I've found informative is The Phenomenological Reduction (IEP).

Wayfarer

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum