-

Ontology of TimeIncidentally there was an earlier thread on the Bergson Einstein debate. The video lecture at the head of that thread is by the author of a book on the subject.

-

Ontology of TimeWell as far as Einstein was concerned, there could only be one subject of discussion. Again, as a scientific realist, he believed that the world is just so, irrespective of how anyone interprets or measures it. We strive for better and better approximations of what is real, but that is something independent of your or my mind. That's what makes him realist.

-

Ontology of TimeTime doesn't exist. Only space and objects exist. — Corvus

Now that I've joined this thread, I will say something about this statement, namely, that I think it's fallacious. Time can be measured according to intersubjectively validated standards, hence the existence of clocks and other time-measurement devices. Every phenomenal existent, and all mechanical and electronic artifacts, are subject to the vicissitudes of time, and regulate their activities, or have them regulated, by or according to time.

What I've been arguing for in this thread is that despite all of this, time is not solely objective. Time has a subjective pole or aspect that can neither be eliminated, nor directly perceived. My first post quoted an Aeon essay to that effect, about the philosophy of Henri Bergson:

Each successive ‘now’ of the clock contains nothing of the past because each moment, each unit, is separate and distinct. But this is not how we experience time. Instead, we hold these separate moments together in our memory. We unify them. A physical clock measures a succession of moments, but only experiencing duration allows us to recognise these seemingly separate moments as a succession. Clocks don’t measure time; we do. — Aeon.co

But this emphatically doesn't mean that 'time doesn't exist', simpliciter. Try holding your breath for a minute while you say that.

Isn't it natural to presume such a dichotomy?

— Wayfarer

Sure. Is it right? — Banno

That's the nub of the issue. In the Einstein-Bergson debate, Einstein, a scientific realist, insisted that time is real irrespective of whether anyone measures it or not - in other words, completely objective. Bergson, as I interpret it, insists that measurement is an intrinsic aspect of time, and that therefore, time is not only objective. And if that goes for time, then the implications are far-reaching. -

Ontology of TimeYou recognise it as a result of having been taught what a right angle is. Right angles area part of your culture as well as a part of the world.

What's problematic is supposed that they are either in the world or they are only in the mind. — Banno

Isn't it natural to presume such a dichotomy? -

Ontology of TimeThe right angle is there becasue we put it there as much as that it is there in some transcendent fashion. — Banno

We don't get to do that. We recognise it. That's how come we could build, you know, pyramids, and the rest. -

Ontology of TimeThe right angles don't EXIST transcendently, nor does any "form". That would entail reifying abstractions. — Relativist

Such forms don't exist in any material sense but they're nevertheless real, as their forms are givens. It would only be a reification if they were regarded as existent objects, which they are not. But then, because they're not existent objects, then naturalism is obliged to say that whatever reality they possess is derivative - products of the mind, is the usual expression. But that is a reflection of the shortcomings of a naturalist ontology.

We can evidently say, for example, that mathematical objects are mind-independent and unchanging, but now we always add that they are constituted in consciousness in this manner, or that they are constituted by consciousness as having this sense … . They are constituted in consciousness, nonarbitrarily, in such a way that it is unnecessary to their existence that there be expressions for them or that there ever be awareness of them. — Source -

Ontology of TimeI would not say that the 90 degree angle exists (it's not an object in the world), but rather: a state of affairs exists (the carpenter's square), and that the 90 degree relation is a component in this state of affairs. So in this sense, 90-degree angle does exist- immanently, within the state of affairs. — Relativist

And I would say, that this relation exists as an intelligible relationship, a regularity that registers as significant for an observing mind. Furthermore that while right angles might exist immanently in particular a carpenter's square they also transcend any specific instantiation. That it is actually a principle, or a form, which can be grasped by an observing mind, and existent in the sense that you and I can both grasp what a right-angle is.

And I say the nature of time is analoguous to that. -

The Musk PlutocracyAbove all, let's just remember one person that has had personal experience from the courts: Donald Trump himself. He's lost, he's won and he has avoided a lot, yet he gives a lot of importance to courts. A true fascist wouldn't care much about the courts, the important thing would be the raw power, the military, the intelligence services and the security forces. I'm not so sure if Trump really can just fire all the judges and replace them with lawyers totally loyal to him. — ssu

He doesn't have to fire them, if he can just bypass them. There are a number of judgements that have already been made about some of his actions, right now the lead NY Times story is Judge Rules the White House Failed to Comply With Court Order with respect to the illegal freezing of Congressionally-approved funds:

A federal judge on Monday said the White House has defied his order to release billions of dollars in federal grants, marking the first time a judge has expressly declared that the Trump White House was disobeying a judicial mandate.

The ruling by Judge John J. McConnell Jr. in Rhode Island federal court ordered Trump administration officials to comply with what he called “the plain text” of an edict he issued on Jan. 29.

That order, he wrote, was “clear and unambiguous, and there are no impediments to the Defendants’ compliance with” it.

Judge McConnell’s ruling marked a step toward what could quickly evolve into a high-stakes showdown between the executive and judicial branches, a day after a social media post by Vice President JD Vance claimed that “judges aren’t allowed to control the executive’s legitimate power,” elevating the chance that the White House could provoke a constitutional crisis. ...

But for some of President Trump’s allies, it is the judges ruling against Mr. Trump who are out of bounds.

“Activist judges must stop illegally meddling with the President’s Article II powers,” wrote Mike Davis, who heads the Article III Project, a conservative advocacy group.

Vance is already saying that the judges are 'acting illegally'. With a supine Congress, from which any meaningful check on Trump's authoritarianism has already been extinguished, the Courts are the last bastion. I think Trump/MAGA will basically just ignore their rulings, saying that the Courts are opposing 'the will of the people' (i.e. Trump.) As I already said, there will be a lot of kvetching in the media about it, but if the President defies the Courts with the backing of Congress, it is very hard to see how he can be stopped.

Also of note is the next story, saying that the President is acting in defiance of the law, and that America is already in a constitutional crisis. But this is what Americans voted for - shaking the place up, taking it to the Establishment - although I really don't know if they comprehended what the outcome would be. -

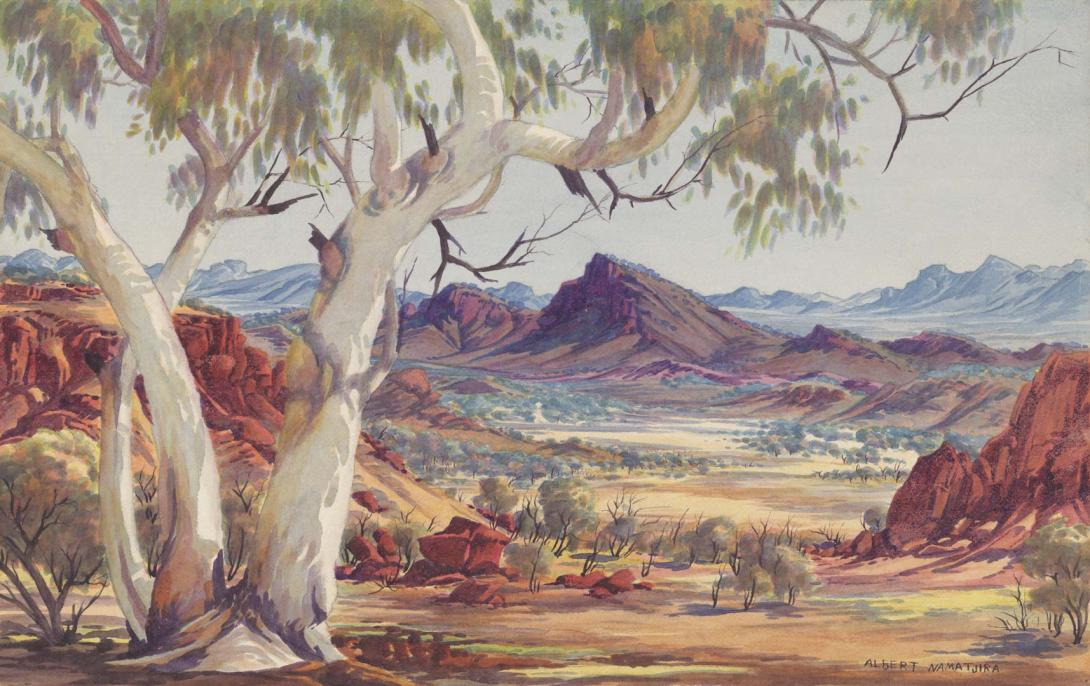

Australian politicsI'm one of those of whom it is said 'He doesn't know much about Modern Art, but he knows what he likes'. I like Albert, not so much Vincent. Seems to me Vincent can’t paint any better than I can, but if that was all I could do, then I wouldn’t do it. Which is why I don’t paint.

-

Australian politics:up:

When I was a kid, I knew about Albert Namatjira - I think one of my schoolteachers showed us his paintings, and I thought they were beautiful works. Still do, even if they’re kind of old-school. -

Australian politicsIt was only by reason of the media flap about that particular painting that I learned anything about the artist. I didn't mean that he should try and beautify or embellish a portrait of Reinhardt, heavens no.

-

Ontology of TimeAs I thought. That's the main point as far as I'm concerned. I think I get why he would be critical of the attempt to boil everything down to subject/object terminology, it was just the kind of abstraction he believed was ruinous.

-

Ontology of TimeI will read it some more. Kudos for you for a very carefully-composed essay. But the overall problem with analytical philosophy is its assumption of a one-dimensional ontology - that everything exists in the same way.

Not a table, then. — Banno

A man (not a man)

Throws a stone (not a stone)...

etc. -

Ontology of TimeDon’t you and I both believe that everything is inseparable from lived experience? — T Clark

Taken out of context: the point being, what is objective is supposed to be real irrespective of experience. So that, time would exist in the same manner as that measured by h.sapiens, were there none of them. That sense of time existing independently of any observer (i.e. absolute time) is what I'm questioning - but it might be useful to peruse the prior entries particularly the one on Einstein and Bergson. So what I'm arguing is that while an observer is intrinsic to the nature of time, the observer is never a part of what is being measured. It's a specific instance of a larger argument.

According to this view the present is determined by a difference with respect to the past and the future, implied by the absence that is given in them. The present is never identically present but always deferred and postponed (a la Derrida), that is, we cannot deny the absence and non-subjectivity that constitutes it. — JuanZu

That becomes a bit abstact for me. I'm not well-versed in 20th century philosophy. My only point is to call into question the idea that time is real sans observers.

Preferably a flat surface, for accomodating objects, a suitable height for the purpose (either standing or sitting) and generally a space underneath to place one's legs if one wishes to sit at it. One can use a packing crate or all manner of objects as a table but provided it fulfills the function of a table then will serve the purpose.What are the necessary and sufficient conditions for table-ness? — Banno

There must be something that makes a table what it is, and this we will call tableness, and we will generalise this to other stuff, and say that what makes something what it is is it's essence. — Banno

And that is, precisely, it's eidos, the 'idea of a table'. But it is not something that exists in the same sense that the table exists.

The above also applies to your article. I see a problem with trying to maintain the notion of 'existence' as being univocal with respect to both the parts and the whole, meaning that the whole then becomes a separate, countable entity in addition to the parts that comprise it - in line with the above. The forms don't exist in the same sense as constituents. Hence the saying, I believe originating with Aristotle (although I might be mistaken) that the whole is more than the sum of its parts. -

Ontology of TimeI think you can post a link, can't you? It's not self-promotion if it's a philosophy article in a journal. Anyway, by all means PM.

Identity doesn’t depend purely on form. If it did, then the table would cease to exist the moment it stopped being functional as a table. — Banno

Which, of course, it does. When the object is dissassembled to its parts, the object no longer exists. Plain language, not 'word salad' :brow:

identity seems to track something deeper—perhaps continuity of language, history, and the way we rigidly designate things — Banno

But whatever that might be, it is not inherent in the object. There is no use looking for a table in the sawdust, that is just a desparate attempt to maintain some kind of objective referent. -

Ontology of TimeThe "form" seems to be a misunderstanding of what happens when we decide to count the newly bonded timber as a table — Banno

It's not a misunderstanding, but an actualisation of potential, at least as I understand it. Form is intrinsic to identity - matter must exist as form in order for it to be intelligible, identifiable as a table. Furthermore a table is an artefact, it is composed according to a design to fulfill a function. -

Ontology of TimeHeidegger’s notion of temporality deconstructs both subjectivity and objectivity, replacing the subject-object binary with Dasein’s being in the world. — Joshs

But would he agree that time is inseparable from lived experience?

Aren't you discussing the Ship of Theseus?

When the collection of atoms existed as a living tree, it wasn't a table, yet it was the table, just as the wood chips are the table. — Banno

Fortuitous example, considering that the 'hyle' in hylomorphism is precisely 'lumber' or 'timber'. -

Ontology of TimeI agree that there is irremediably a type of time that exists as Bergson points out. But I would not be so sure that it is something simply subjective. — JuanZu

Actually, there is something I want to add about this. I'm not referring to the 'simply subjective' which is a rather dismissive way of framing it. The subjective pole of existence is not subjective in the sense of pertaining to the individual subject, but more in the sense of Kant and Husserl's transcendental ego - that which describes the structure of consciousness of any subject (or the 'ideal subject'). To quote an essay of mine on the issue, 'The subjective refers to the structures of experience through which reality is disclosed to consciousness. In an important sense, all sentient beings are subjects of experience. Subjectivity — or perhaps we could coin the term ‘subject-hood’ — encompasses the shared and foundational aspects of perception and understanding, as explored by phenomenology. The personal, by contrast, pertains to the idiosyncratic desires, biases, and attachments of a specific individual.' Which is what I think the second part of your post is referring to as 'constitutive of subjectivity'. -

Ontology of TimeWe must be very cautious in introducing consciousness as an observer. The two things are not the same. The same has to be said about seeing and measuring, they are not the same. — JuanZu

I don't much like the way Andrei Linde introduces the term 'consciousness'. I would prefer it if he stuck with 'the observer'. But then, Andrei Linde is a qualified commentator, he is a recognised expert in cosmological physics. He says in the interview that his publisher was very anxious about including his thoughts about consciousness on the matter - but, says Linde, he couldn't live with his conscience if he didn't.

My interpretation of the matter is simply that time has an inextricably subjective pole. So there's no truly objective time in the sense of being independent of any act of observation and measurement. This is implicit in what Linde says - that an observation requires there to be an observer and what is being measured. Time is only meaningful in that context - it is not truly observer-independent in the way that scientific realism might expect.

But that certainly doesn't mean, as the OP says, that time doesn't exist. It is far too simplistic an idea, and obviously problematic, as these very communications devices are reliant on measures of time. -

Australian politicsIt is truly a horrible painting. I don't much like Gina Reinhardt, she's Australia's richest women, heir of a massive iron ore fortune, and a Trump toady, trying to create an Australian MAGA party. But as much as I dislike her, I agree that painting is truly awful.

As for the artist - Vincent Namatjira is is great-grandson of another famous indigenous artist, Albert Namatjira (1902-1959). Albert Namatjira was well-known for painting Australian landscapes in a classical European watercolour style, which I would guess is a bit politically uncomfortable for many people today, because anything classical and European is, of course, associated with colonialism and the oppression of First Nation's peoples.

An example of Albert Namatjira's art:

So, reading around, I notice in the Wikipedia entry, that:

Initially thought of as having succumbed to European pictorial idioms – and for that reason, to ideas of European privilege over the land – Namatjira's landscapes have since been re-evaluated as coded expressions on traditional sites and sacred knowledge..

...presumably meaning that his works have been declared to adhere to politically-correct aesthetic standards by the appropriate cultural guardians.

Vincent Namatjira's work, on the other hand, is nowadays popular, but, to me at least, seems to lack the graceful aesthetics, not to mention artistic technique, of his grandfather's.

Source

But each to his or her own, I suppose. -

Ontology of TimeFor sure. Emphasis on 'lived'. But that is not what the OP said, and I believe it's overall mistaken.

The problem of including the observer in our description of physical reality arises most insistently when it comes to the subject of quantum cosmology - the application of quantum mechanics to the universe as a whole - because, by definition, 'the universe' must include any observers.

Andrei Linde has given a deep reason for why observers enter into quantum cosmology in a fundamental way. It has to do with the nature of time. The passage of time is not absolute; it always involves a change of one physical system relative to another, for example, how many times the hands of the clock go around relative to the rotation of the Earth. When it comes to the Universe as a whole, time looses its meaning, for there is nothing else relative to which the universe may be said to change. This 'vanishing' of time for the entire universe becomes very explicit in quantum cosmology, where the time variable simply drops out of the quantum description. It may readily be restored by considering the Universe to be separated into two subsystems: an observer with a clock, and the rest of the Universe.

So the observer plays an absolutely crucial role in this respect. Linde expresses it graphically: 'thus we see that without introducing an observer, we have a dead universe, which does not evolve in time', and, 'we are together, the Universe and us. The moment you say the Universe exists without any observers, I cannot make any sense out of that. I cannot imagine a consistent theory of everything that ignores consciousness...in the absence of observers, our universe is dead'. — Paul Davies, The Goldilocks Enigma: Why is the Universe Just Right for Life, p 271

And from the horse's mouth:

-

The Musk PlutocracyPredictably, Trusk has directed vitriol at the judge who has put restrictions on DOGE:

Elon Musk expressed outrage on Saturday after a federal judge in New York temporarily restricted his government cost-cutting team’s access to the Treasury Department’s payment and data systems.

In a rapid-fire series of posts on his social media site X, Mr. Musk criticized the decision and called the judge, Paul A. Engelmayer, “an activist posing as a judge.”

Judge Engelmayer said in his decision that there was a risk of “irreparable harm” in allowing Treasury access by political appointees and “special government employees,” which includes Mr. Musk and members of his team. Access to those systems, he said, could leave highly sensitive financial information vulnerable to leaks and hacks.

In a separate statement, the White House called the judge an “activist” and the ruling “absurd and judicial overreach” for effectively locking the treasury secretary out of his role.

“These frivolous lawsuits are akin to children throwing pasta at the wall to see if it will stick,” Harrison Fields, a spokesman, said in a statement. “Grandstanding government efficiency speaks volumes about those who’d rather delay much-needed change with legal shenanigans than work with the Trump administration of ridding the government of waste, fraud, and abuse.”

Mr. Musk said on X that the Treasury Department and his team had agreed upon a list of adjustments to be made to the payroll system that were “obvious and necessary changes,” including incorporating a do-not-pay list and mandating categorization codes and notes in comment fields outlining reasons for payments.

In response to a post from the conservative podcaster Charlie Kirk, who said the Trump administration should consider defying the order if it becomes permanent, Mr. Musk suggested without evidence that the judge’s decision was part of a “super shady” scheme to protect scammers.

The judge’s decision barred Mr. Musk and his team from access to the systems at least until Friday, when a hearing before a different judge was scheduled in the matter. Those workers who have been allowed access since Jan. 20 must “destroy any and all copies of material downloaded from the Treasury Department’s records and systems,” according to the order.

It was unclear if the Trump administration and Mr. Musk’s team would take steps to comply with the emergency order.

Last month, just after President Trump took office, a top Treasury Department official, David Lebryk, refused to give Mr. Musk’s team access to the government’s payment system. He was placed on administrative leave and later announced his retirement. — NY Times

I had thought 'contempt of Court' was a thing, but I guess it's another thing that Trusk wants to abolish. -

Ontology of TimeWell said.

There's an interesting essay on Aeon.co, Who Really Won when Bergson and Einstein Debated Time? Evan Thompson.

It concerns a famous debate which occured spontaneously when Henri Bergson attended a public lecture by Einstein, and then gave an improptu talk on his conception of 'experienced' as distinct from 'objective' time. In short, Einstein brushed off Bergson's talk, and public opinion has generally had it that Einstein, who after all probably has the greatest scientific prestige of any 20th c figure, was correct.

Here, Thompson questions that.

We usually imagine time as analogous with space. We imagine it, for example, laid out on a line (like a timeline of events) or a circle (like a sundial ring or a clock face). And when we think of time as the seconds on a clock, we spatialise it as an ordered series of discrete, homogeneous and identical units. This is clock time. But in our daily lives we don’t experience time as a succession of identical units. An hour in the dentist’s chair is very different from an hour over a glass of wine with friends. This is lived time. Lived time is flow and constant change. It is ‘becoming’ rather than ‘being’. When we treat time as a series of uniform, unchanging units, like points on a line or seconds on a clock, we lose the sense of change and growth that defines real life; we lose the irreversible flow of becoming, which Bergson called ‘duration’.

Think of a melody. Each note has its own distinct individuality while blending with the other notes and silences that come before and after. As we listen, past notes linger in the present ones, and (especially if we’ve heard the song before) future notes may already seem to sound in the ones we’re hearing now. Music is not just a series of discrete notes. We experience it as something inherently durational.

Bergson insisted that duration proper cannot be measured. To measure something – such as volume, length, pressure, weight, speed or temperature – we need to stipulate the unit of measurement in terms of a standard. For example, the standard metre was once stipulated to be the length of a particular 100-centimetre-long platinum bar kept in Paris. It is now defined by an atomic clock measuring the length of a path of light travelling in a vacuum over an extremely short time interval. In both cases, the standard metre is a measurement of length that itself has a length. The standard unit exemplifies the property it measures.

In Time and Free Will, Bergson argued that this procedure would not work for duration. For duration to be measured by a clock, the clock itself must have duration. It must exemplify the property it is supposed to measure. To examine the measurements involved in clock time, Bergson considers an oscillating pendulum, moving back and forth. At each moment, the pendulum occupies a different position in space, like the points on a line or the moving hands on a clockface. In the case of a clock, the current state – the current time – is what we call ‘now’. Each successive ‘now’ of the clock contains nothing of the past because each moment, each unit, is separate and distinct. But this is not how we experience time. Instead, we hold these separate moments together in our memory. We unify them. A physical clock measures a succession of moments, but only experiencing duration allows us to recognise these seemingly separate moments as a succession. Clocks don’t measure time; we do. — Aeon.co

I think this is the salient point: that time itself relies on or is bound to the awareness of duration. And the awareness of duration is something that only a mind can bring. Of course, we don't notice that, because to do so would require becoming aware of awareness, which we cannot do as it would require a perspective outside of awareness. In Kantian terms, the awareness of time is a transcendental condition of experience, and whilst such conditions determine experience, they are not directly available within experience (that being pretty much the meaning of 'transcendental' in Kant's philosophy.)

Thompson goes on to note that Bergson was factually incorrect in his dismissal of the idea of time dilation, which is the discovery that time passes at measurably different rates for observers travelling at vastly different velocities. This error also undermined Bergson's reputation, which overall did not much outlast WWII except for in the Universities, unlike Einstein's, whose reputation has overall only increased. Nevertheless, Thompson argues, Bergson's fundamental insight about the significanc of 'lived time' remains valid, in Thompson's argument. -

The Musk PlutocracyBreaking news:

A federal judge early Saturday temporarily restricted access by Elon Musk’s government efficiency program to the Treasury Department’s payment and data systems, saying there was a risk of “irreparable harm.”

The Trump administration’s new policy of allowing political appointees and “special government employees” access to these systems, which contain highly sensitive information such as bank details, heightens the risk of leaks and of the systems becoming more vulnerable than before to hacking, U.S. District Judge Paul A. Engelmayer said in an emergency order.

Judge Engelmayer ordered any such official who had been granted access to the systems since Jan. 20 to “destroy any and all copies of material downloaded from the Treasury Department’s records and systems.” He also restricted the Trump administration from granting access to those categories of officials.

The defendants — President Trump, Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent and the Treasury Department — must appear on Feb. 14 before Judge Jeannette A. Vargas, who is handling the case on a permanent basis, Judge Engelmayer said.

The situation could pose a fundamental test of America’s rule of law. If the administration fails to comply with the emergency order, it is unclear how it might be enforced. The Constitution says that a president “shall take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed,” but courts have rarely been tested by a chief executive who has ignored their orders.

Federal officials have sometimes responded to adverse decisions with dawdling or grudging compliance. Outright disobedience is exceedingly rare. There has been no clear example of “open presidential defiance of court orders in the years since 1865,” according to a Harvard Law Review article published in 2018.

Saturday’s order came in response to a lawsuit filed on Friday by Letitia James of New York along with 18 other Democratic state attorneys general, charging that when Mr. Trump had given Mr. Musk the run of government computer systems, he had breached protections enshrined in the Constitution and “failed to faithfully execute the laws enacted by Congress.”

The lawsuit was joined by the attorneys general of Arizona, California, Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, Hawaii, Illinois, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Nevada, New Jersey, North Carolina, Oregon, Rhode Island, Vermont and Wisconsin.

They said the president had given “virtually unfettered access” to the federal government’s most sensitive information to young aides who worked for Mr. Musk, who runs a program the administration calls the Department of Government Efficiency, or DOGE.

While the group was supposedly assigned to cut costs, members are “attempting to access government data to support initiatives to block federal funds from reaching certain disfavored beneficiaries,” according to the suit. Mr. Musk has publicly stated his intention to “recklessly freeze streams of federal funding without warning,” the suit said, pointing to his social media posts in recent days.

In her own social media post on Saturday, Ms. James reiterated that members of the cost-cutting team “must destroy all records they’ve obtained,” and added: “I’ve said before, and I’ll say it again: no one is above the law,” she wrote. ...

Before Mr. Trump took office last month, access was granted to only a limited number of career civil servants with security clearances, the suit said. But Mr. Musk’s efforts had interrupted federal funding for health clinics, preschools and climate initiatives, according to the filing.

The money had already been allocated by Congress. The Constitution assigns to lawmakers the job of deciding government spending. — Judge Halts Access to Treasury Payment Systems by Elon Musk’s Team

Congress has plainly surrendered to Trump's will. The judiciary is the last bastion, but my sense is that Trump will flout these rulings, and the Courts don't have any real power to enforce them. There will be much moaning and gnashing of teeth in the media, but Musk will simply brush it aside. At that point, it will, at least, have been made manifestly obvious that the President and his main collaborator are operating in defiance of the law.

source -

The Musk PlutocracyA video falsely claiming that the United States Agency for International Development paid Ben Stiller, Angelina Jolie and other actors millions of dollars to travel to Ukraine appeared to be a clip from E!News, though it never appeared on the entertainment channel.

In fact, the video first surfaced on X in a post from an account that researchers have said spreads Russian disinformation.

Within hours it drew the attention of Elon Musk, who reposted it. So did President Trump’s son Donald Trump Jr. -

Philosophy writing challenge June 2025 announcementSomethimg which you alone can provide, hence the point of the exercise!

-

I Refute it Thus!On second thoughts, what I will say is that I think humans alone are capable of giving explanations, and I think that this is self-evident. So if you want me to explain that, I will decline, as I don’t think an explanation is required.

humans seem to have an innate ability to determine that we are favoured creatures of gods, and better/smarter than everything else on the planet. — Tom Storm

That is how Christians are said to have construed it, which fact is then regarded as an argument against it. But the Greeks proclaimed the sovereignty of reason before Jesus came along. Again, any argument against it must appeal to the very faculty which it seeks to question. It must give reasons.

It might even be argued that our particular brand of reasoning makes us inferior to animals who have and can find and do everything they need much more simply and elegantly than humans. — Tom Storm

A moral judgement which no animal would make. There is nothing better or worse for them. They’re not able to envisage that things could be otherwise than what they are. -

Fascism in The US: Unlikely? Possible? Probable? How soon?Started by Never Trumper Republican media people. Like the Lincoln Project. But all those panelists are independent of that.

-

Fascism in The US: Unlikely? Possible? Probable? How soon?I agree, and I do read The Bulwark from time to time. But they’re all disillusioned conservatives, which shows just how far MAGA has morphed from its origins.

-

Fascism in The US: Unlikely? Possible? Probable? How soon?So, no one is really indigenous to anywhere except the African continent. — Arcane Sandwich

What about the warm little pond?? Where was that? :brow:

We know things must be truly desperate when 180 starts posting The Bulwark. -

Philosophy writing challenge June 2025 announcementMy advice would be to start with a concise paragraph expressing the point of the essay. Then sketch out headings and sub-headings, representing the progressive stages of building the argument and the steps required to establish each step. That step of building level 1, 2 and 3 headings is often helpful in structuring your content.

Also consider likely objections and your counter to them.

End with a conclusion which should state the paragraph you started with but now as a conclusion based on the preceding paragraphs. -

Could anyone have made a different choice in the past than the ones they made?Read the question and decided, against character, to register a response.

-

The Musk PlutocracyHochschild has plainly bought into the alternative history, that the insurrection attempt was a peaceful protest about a stolen election with the protesters as victims. I suspect it is futile to attempt to reason against such a view. It’s part of the process of normalizing ‘the big lie’ such that it becomes the dominant narrative.

Think of all the lies I got to put up with! ---Pretenses! Ain't that mendacity? Having to pretend stuff you don't think or feel or have any idea of? — Big Daddy, in Cat on a Hot Tin Roof -

I Refute it Thus!s the line between us and animals so special because we have atom bombs and iPhones? Are our more complex adaptations and affectations a sign of superiority or really a kind of deficit? — Tom Storm

I’m going to make a spinoff thread and respond, but it will tomorrow. -

I Refute it Thus!This is what I think is required to support your claim of an ontological difference of kind. — Metaphysician Undercover

On what basis did Aristotle designate man the ‘rational animal’?

The ‘faculty of reason’ is a perfectly intelligible expression, and the idea that humans alone possess it fully developed, and some animals only in very rudimentary forms, ought hardly need to be stated. Yet for some reason whenever it is stated, it provokes a good deal of argument. Which I attribute to the irrationality of modern culture!

Wayfarer

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum