-

The Mind-Created WorldThe key representatives of objective idealism I can think of are Hegel and Plato. — Count Timothy von Icarus

Quite right, although as often pointed out, the term ‘idealism’ was not current in Plato’s time and would not be coined until the 1700’s. But there’s another contemporary defender of absolute idealism, Sebastian Rodl, professor of philosophy at Leipzig University. From the jacket copy of Self-Consciousness and Objectivity: an Introduction to Absolute Idealism ‘ Self-Consciousness and Objectivity undermines a foundational dogma of contemporary philosophy: that knowledge, in order to be objective, must be knowledge of something that is as it is, independent of being known to be so. Sebastian Rodl revives the thought--as ancient as philosophy but largely forgotten today--that knowledge, precisely on account of being objective, is self-knowledge: knowledge knowing itself.’ -

The Mind-Created WorldThe question of solipsism has come up several times in this thread. ‘If “the world” is experience alone, then how is solipsism avoided?’

From an excellent blog post on idealism and non-duality, the following solution is given:

Influenced by the Zen experience of Enlightenment (“satori”), the Japanese philosopher Kitarō Nishida writes in his classic work An Inquiry into the Good: “Over time I came to realize that it is not that experience exists because there is an individual, but that an individual exists because there is experience. I thus arrived at the idea that experience is more fundamental than individual differences, and in this way I was able to avoid solipsism… The individual’s experience is simply a small, distinctive sphere of limited experience within true experience. (Nishida, Kitarō (1990 [1922]), An Inquiry into the Good.)

With his statement that the Zen experience of Enlightenment enabled him to “avoid solipsism”, Nisihida indicates the insight that consciousness is not ‘locked up’ inside the individual’s head or brain: “it is not that consciousness is within the body, but that the body is within consciousness”. (Idem: 43.) If consciousness resided in the brain, it would indeed be cut off from the world outside one’s skull, which would invite the solipsistic conclusion that all I can know is the phenomenal world appearing in my subjective consciousness, but not the real, objective world outside of it. The Zen realization that consciousness is radically different, that it is rather the non-dual openness in which both individual and world appear, thus takes away the threat of solipsism. Nishida, of course, does not deny that brain activity is closely connected to individual mind activity, but for him this only means that one group of phenomena appearing in consciousness (mental processes) correlates with another such group (neural processes): “To say that phenomena of consciousness accompany stimulation to nerve centers means that one sort of phenomena of consciousness necessarily occurs together with another.” (Ibidem.) This already gives a glimpse of how Western Idealism can benefit from Eastern spirituality.

(I think this is the same point I try to make with the argument that ‘the mind’ is not simply the individual mind, your mind or mind, but the mind, which however is never an object of consciousness.) -

Currently ReadingTotally get that. Author is a young Australian researcher, this is her PhD thesis, published as a book. I found it via another really interesting article I’ll share soon. BTW - you might check out this blog, Critique of Pure Interest, by a Dutchman with a lot of reading under his belt and a keen insight into non-dualism.

-

Aquinas on existence and essenceThe passage you’ve linked to clearly says in many places that Descartes conceives the soul and body as separate substances, with the soul acting on the body through the pineal gland, for example:

In the Treatise of man, Descartes did not describe man, but a kind of conceptual models of man, namely creatures, created by God, which consist of two ingredients, a body and a soul. “These men will be composed, as we are, of a soul and a body.’

….. Descartes’ criterion for determining whether a function belongs to the body or soul was as follows: “anything we experience as being in us, and which we see can also exist in wholly inanimate bodies, must be attributed only to our body. On the other hand, anything in us which we cannot conceive in any way as capable of belonging to a body must be attributed to our soul.

While it’s true that the description of his position in terms of other schools of though might be a matter of debate, Descartes’ dualism is a fact of his philosophy.

Not a point you will find support for in any of the sources you’ve quoted, as far as I can discern.My point was that for Descartes held the soul and body to be held by one ego — Gregory

‘Cogito’ is purely the functionality of the ‘res cogitans’, whereas all the motions of the body, he describes in ‘mechanical’ terms with reference to ‘animal spirits’, although as the article notes, he made important errors even in terms of what was known in his day, all of which is of course completely superseded in our say. -

Currently Readingmate you’re a champion. Averse as I am to IP violations, here my curiosity outweighs such scruples. Thanks a ton.

-

Currently ReadingI’ve discovered the book I’ve been wanting to read for decades: The Pythagorean World: Why Mathematics is Unreasonably Effective in Physics, Jane McDonnell. The bad news is that even the Kindle edition is AU$109.00 and the hardcover $128.00 - specialist academic text, I guess but seems to offer the kind of objective idealist philosophy I’ve always sought after. ‘This work defends the proposition that mind and mathematical structure are the grounds of reality.’

-

The Mind-Created WorldHume dissolved the self. Mach and Heidegger do so in their own ways. I hope it's not too eurocentric to hope for some kind of universal human insight here, which is a product of a universal-enough human logic. — plaque flag

There have been many comparisons between Hume’s so-called ‘bundle theory of self’ and Buddhist no-self teachings. But obviously the context and intentions of Hume’s philosophy and Buddhism are worlds apart. (Although there’s an interesting, if overly long, essay in The Atlantic, about the possibility that Hume encountered Buddhist teachings in the French town of Le Clerche we he lived whilst composing The Treatise.)

With respect to the ‘six sense gates’, that is from abhidharma, Buddhist philosophical psychology. It’s a very sophisticated system and very hard condense, although it’s noteworthy that it’s often mentioned by Francisco Varela and Humberto Maturana in their research into embodied cognition. Its convergences with phenomenology have also been subject to a lot of comment.

Some of my best work related thinking has ocurred when I'm not thinking about the topic, and possibly even while I was sleeping. — wonderer1

An interesting book by a 60s-70s author whose name is rapidly receding in the past: ‘The Sleepwalkers: A History of Man's Changing Vision of the Universe is a 1959 book by Arthur Koestler. It traces the history of Western cosmology from ancient Mesopotamia to Isaac Newton. He suggests that discoveries in science arise through a process akin to sleepwalking. Not that they arise by chance, but rather that scientists are neither fully aware of what guides their research, nor are they fully aware of the implications of what they discover.’ It’s full of serendipitous discoveries and scientists making astonishing, accidental discoveries whilst in pursuit of something else altogether. And accounts of discoveries like you mention, where insights arise unexpectedly when going about their daily lives. -

Why is rational agreement so elusive?How do you mean it has been demolished, by what/whom? — kudos

What I meant was that while religion used to provide the ‘summum bonum’, a universally-agreed ‘highest good’, this history of sectarian religious conflict has undermined that consensus. (Well, among other factors.) -

Dualism and InteractionismIt means that particulars do not instantiate Platonic Ideas or universal — Dfpolis

Gotcha -

Dualism and InteractionismIt (the law of identity) states something about all particulars which differentiates a particular from a universal. — Metaphysician Undercover

So in the way that this law is usually identified - “A=A” - what, precisely, is the difference between the left-hand ‘A’ and the right hand ‘A’? Are they ‘particulars’?

You can Google "the problem of universals" — Dfpolis

I've read up on it, to some extent. The paper you linked is highly specific, however. -

Aquinas on existence and essenceThat's just a word salad. — Gregory

You ask a question then don't understand the answer. It's philosophy 101. -

Aquinas on existence and essenceAquinas' hylomorphic dualism does not suffer from the 'interaction problem' of Descartes because it does not posit a stark dichotomy between body and soul (or mind). In the hylomorphic framework a human being is not seen as two substances "joined" together but as a single substance composed of form (soul) and matter (body). The soul, as the form of the body, gives a particular human being its essential characteristics and powers. Thus, humans are a composite of soul and body, with the soul being the animating principle of the body.

For Aquinas, the soul and body are intimately connected in such a way that the soul is the "form" of the body. This means that the body achieves its particular nature and function through the soul. There's no need for an external "bridge" for interaction since the soul and body are intrinsically intertwined.

Instead of seeing the mind and body as two separate entities that need a mechanism to interact, Aquinas views the various capacities of the soul (e.g., intellect, will) as interacting seamlessly with the body. For instance, sensory perceptions inform the intellect, which in turn can lead to bodily actions driven by the will.

So Aquinas' hylomorphic dualism doesn't suffer from the "interaction problem" because it posits a more integral relationship between soul and body than does Cartesian dualism. The soul, in the Thomistic view, isn't a separate substance from the body but its very form, making their interaction natural and intrinsic.

If you still can't see the distinction, then I'm afraid I'm unable to provide further help. -

Aquinas on existence and essenceDescartes described a human as one substance composed of body and soul. — Gregory

Not so. Descartes proposes two 'substances', one purely intellectual, the other purely material.

This conclusion in the Sixth Meditation asserts the well-known substance dualism of Descartes. That dualism leads to problems. As Princess Elisabeth, among others, asked: if mind is unextended and matter is extended, how do they interact? This problem vexed not only Descartes, who admitted to Elisabeth that he didn't have a good answer (3:694), but it also vexed Descartes' followers and other metaphysicians. It seems that, somehow, states of the mind and the body must be brought into relation, because when we decide to pick up a pencil our arm actually moves, and when light hits our eyes we experience the visible world. But how do mind and body interact? Some of Descartes' followers adopted an occasionalist position, according to which God mediates the causal relations between mind and body; mind does not affect body, and body does not affect mind, but God gives the mind appropriate sensations at the right moment, and he makes the body move by putting it into the correct brain states at a moment that corresponds to the volition to pick up the pencil. Other philosophers adopted yet other solutions, including the monism of Spinoza and the pre-established harmony of Leibniz. — René Descartes, SEP

One of the deepest and most lasting legacies of Descartes’ philosophy is his thesis that mind and body are really distinct—a thesis now called “mind-body dualism.” He reaches this conclusion by arguing that the nature of the mind (that is, a thinking, non-extended thing) is completely different from that of the body (that is, an extended, non-thinking thing), and therefore it is possible for one to exist without the other. This argument gives rise to the famous problem of mind-body causal interaction still debated today. — Descartes, the Mind-Body Distinction -

Why is rational agreement so elusive?Second, one of most prevalent tendencies in post-modern philosophy has been to question, often hostilely, the role of rationality itself – what is it, what is it worth, what knowledge does it lead to, etc. Can this sort of critique of rationality be deployed to examine the Habermas problem? In other words, is it possible that the often frustrating morass of competing “reasonable” claims might be a revealing wake-up call about rationality itself, and its role in philosophy? — J

Obviously a very deep and difficult issue.

One point, it is the nature of dialect to explore a question from the perspective of competing arguments. That is why dialectic, in particular, has such a role in philosophy. For example Kant's critiques responded to the dialectic between empiricist (Hume, Berkeley) and rationalist (Spinoza, Liebniz) philosophers. In so doing he produced a kind of 'third way' which was not available to the protagonists of either side. In some ways, dialectic offers a kind of range of possibility, rather than a settled dogma.

Another point is that attaining philosophical insight might not itself be easy or even possible to communicate. It is often said that philosophy is hung up on problems it has been canvassing for 2,000 years 'without making any progress'. But how do you measure 'progress' in this matter? Perhaps some of the sages of yore reached a pinnacle of philosophic insight which is preserved in their writings - the later platonists come to mind - but those who now read them don't really understand them, and neither did many of their contemporaries. In which case the accusation of futility is not really applicable. It's that realising the insights that they try to convey is very difficult - unlike the fruits of scientific research, which are cumulative across generations, and yield practical results.

It could be argued that reason in contemporary culture lacks the kind of lodestar that was formerly provided by religion. After all, it was suppose to provide the summum bonum, the reason for all reasons. But then religion seems itself to have demolished that ideal, when viewed through the history of religious conflict in Western culture.

There's an old opinion piece in the NY Times that I often cite, concerning Habermas' dialogue with religion (as is well-known, he engaged in a number of dialogues with Cardinal Ratzinger, later Pope Benedict XVI). This was eventually published as the book An Awareness of What is Missing. Habermas is not endorsing any kind of wholesale return to religious faith, rather he says that while 'religion must accept the authority of secular reason as the fallible results of the sciences and the universalistic egalitarianism in law and morality, conversely, secular reason must not set itself up as the judge concerning truths of faith.'

In the NY Times column, some of these points are discussed:

What secular reason is missing is self-awareness. It is “unenlightened about itself” in the sense that it has within itself no mechanism for questioning the products and conclusions of its formal, procedural entailments and experiments. “Postmetaphysical thinking,” Habermas contends, “cannot cope on its own with the defeatism concerning reason which we encounter today both in the postmodern radicalization of the ‘dialectic of the Enlightenment’ and in the naturalism founded on a naïve faith in science.”

Postmodernism announces (loudly and often) that a supposedly neutral, objective rationality is always a construct informed by interests it neither acknowledges nor knows nor can know. Meanwhile science goes its merry way endlessly inventing and proliferating technological marvels without having the slightest idea of why. The “naive faith” Habermas criticizes is not a faith in what science can do — it can do anything — but a faith in science’s ability to provide reasons, aside from the reason of its own keeping on going, for doing it and for declining to do it in a particular direction because to do so would be wrong.

So I suppose none of that points to a resolution - which, considering the topic, is kind of appropriate. -

Aquinas on existence and essenceI dont see why the interaction problem would apply to Aquinas any less than to Descartes. The soul is the same for both. — Gregory

Not true. Aquinas doesn't depict the soul as a separate substance in the way Descartes does, so there are not two types of entity involved. Beyond that, I will have to yield to someone with better knowledge of A-T than I. -

The Mind-Created WorldAs long as you include Kant in your criticism, I hear you. — plaque flag

I've often said, and sorry if I'm repeating myself, that I first encountered Kant in The Central Philosophy of Buddhism, T R V Murti, a book that became very much part of my spiritual formation. Murti compares Kant with Madhyamaka (the middle-way of Nāgārjuna) and details many convergences between them. This book has since been deprecated by more current academics on the grounds that Murti (an Indian, Oxford-educated scholar) was too 'eurocentric' in his approach but one of my thesis supervisors endorsed it. As to how to incorporate Buddhism in such a way that it's meaningful, I won't pretend that is an easy question. -

The Mind-Created WorldYes, but I'm wary of the German idealists. I've been reading Magnificent Rebels, by Andrea Wulff, which is about Fichte, Schelling and others in late 18th c Jena. Even though I have respect for the German idealists, they were often verbose and incredibly obscure. Fichte's writings, of which I only have very small exposure, are labyrinthine. (I seem to recall him boasting that he was so clever he doubted anyone in his orbit would be able to understand his brilliance.) There are points of convergence between German idealism and (particularly) Vedanta philosophy, that is subject to comment, but the Germans lacked the cultural milieu in which to actualise those insights, in my opinion. (This is also covered extensively in Urs Apps' 'Schopenhauer's Compass' which is the other book I'm reading on it.)

-

The Mind-Created WorldOne of my concerns about hidden-in-principle stuff in the self is that it leads us back into dualism. — plaque flag

But it only does that when you begin to speculate 'what could that be?' By positing it as something, then you're introducing a division or rupture. Obviously this is a very deep subject, but it came up in the MA thesis I did in 2012 on Anatta (no-self) in Buddhism. The first excerpt is from the Buddha referring to the states of jhana (meditative absorption). Then there's a Q&A between a monk and a senior monk on what this means.

The intellect is to be abandoned. Ideas are to be abandoned. Consciousness at the intellect is to be abandoned. Contact at the intellect is to be abandoned. And whatever there is that arises in dependence on contact at the intellect — experienced as pleasure, pain or neither-pleasure-nor-pain — that too is to be abandoned. — Pahanaya Sutta, SN 35.24

Does this say, then, that beyond the ‘six sense gates’ and the activities of thought-formations and discriminative consciousness, there is nothing, the absence of any kind of life, mind, or intelligence? Complete non-being, as many of the early European interpreters were inclined to say. This question is put to Ven Sariputta (Sariputta is the figure in the Buddhist texts most associated with higher wisdom):

Then Ven. Maha Kotthita went to Ven. Sariputta and, on arrival, exchanged courteous greetings with him. After an exchange of friendly greetings & courtesies, he sat to one side. As he was sitting there, he said to Ven. Sariputta, "With the remainderless stopping & fading of the six contact-media [vision, hearing, smell, taste, touch, & intellection] is it the case that there is anything else?"

[Sariputta:] "Don't say that, my friend."

[Maha Kotthita:] "With the remainderless stopping & fading of the six contact-media, is it the case that there is not anything else?"

[Sariputta:] "Don't say that, my friend."

….

[Sariputta:] "The statement, 'With the remainderless stopping & fading of the six contact-media [vision, hearing, smell, taste, touch, & intellection] is it the case that there is anything else?' objectifies non-objectification.The statement, '... is it the case that there is not anything else ... is it the case that there both is & is not anything else ... is it the case that there neither is nor is not anything else?' objectifies non-objectification. However far the six contact-media go, that is how far objectification goes. However far objectification goes, that is how far the six contact media go. With the remainderless fading & stopping of the six contact-media, there comes to be the stopping, the allaying of objectification. — Kotthita Sutta, AN 4.174

The phrase ‘objectifies non-objectification’ (vadaṃ appapañcaṃ papañceti) is key here. As Thanissaro Bikkhu (translator) notes in his commentary, ‘the root of the classifications and perceptions of objectification is the thought, "I am the thinker." This thought forms the motivation for the questions that Ven. Maha Kotthita is presenting here.’ The very action of thinking ‘creates the thinker’, rather than vice versa. In effect, the questioner is asking, ‘is this something I can experience?’ So the question is subtly ego-centric.

The way this translates to me, is in the form of a strictly apophatic approach: knowing that you don't know. That is different to wondering what it might be, if you can see what I mean. That was the approach of a particular Korean Son (Zen) teacher, Seungsahn, who's teaching method was 'only don't know!'

Of course, it's easy to say such things (particularly for me as I'm overly loquacious) but actually realising it requires considerable dedication. That is the practical application (praxis). -

Aquinas on existence and essenceGlossary entry: In Aquinas' epistemology, the essence (essentia or quidditas) of a particular refers to "what it is." It delineates the nature or the kind of a particular being. Existence (esse), on the other hand, refers to "that it is," or to the act of existing. Aquinas argues that in all beings essence and existence are distinct (except for in God, see below). This means that for any given creature, what it is (its essence) is distinct from the fact that it exists. In God, essence and existence are identical.

In Aristotelian and Thomist (A-T) metaphysics, there's a distinction between accidental and essential properties. Essential properties are those that belong to the essence of a thing (without which the thing wouldn't be what it is), while accidental properties are those that can change without the thing becoming something else (like color, size, etc.) Beings (at least corporeal beings) are composed of matter and form. Matter provides the potentiality for a particular being, while form actualizes that potentiality and gives it a specific nature. "Esse" (existence) is the act by which something exists, whether that thing is material (composed of matter and form) or immaterial (such as angelic intelligences).

Aquinas indeed holds that forms are known by the intellect, but these forms are abstracted from the particulars sensed by the corporeal senses. It's not that the form is "what is real" and the particulars are not. Rather, the intellect knows things in a universal, abstracted manner, while the senses know them in their particularity. (The nature and reality or otherwise of universals is one of the great arguments in Western philosophy.)

When comparing Aquinas's views with later philosophical traditions, It's important to distinguish between the hylomorphic (matter-form) dualism of Aristotle/Aquinas and the substance dualism of Descartes. The former argues that every material being is a composite of matter and form, while the latter argues that a human being is composed of two distinct substances: mind (res cogitans) and body (res extensia) which seem to be separable in principle, giving rise to the well-known 'interaction problem'. -

The Mind-Created WorldWell, Heidegger was according to some readings still pre-occupied with the fallen state of humanity. I think the absence of that kind of sense from secular humanism is a yawning gulf. It seems we (i.e. Steve Pinker) just want to make the world like a five-star resort. And it ain't going so well.

Yes, the accounts from Israel are absolutely shattering and heart-breaking, aside from being absolutely bloody terrifying, although there is a separate thread on that (although I'm refraining from general comments, it will only add to the hubbub.) -

The Mind-Created WorldWe are thrown into doing things the Right way. — plaque flag

except for when we don't, which seems to happen an awful lot. -

The Mind-Created WorldRight. Dasein as being 'thrown into' existence. (Anamnesis, remembering how it happened, although I don't think that's in Heidegger.)

-

The Mind-Created WorldHow can a 'machine' (a mere faculty) give us a normative 'output' ? — plaque flag

There's nothing mechanical about reason. Reason is the relation of ideas. And the reason why it seems 'metaphysical' is because, as we already established, you look with it, not at it. We can't know it, because it is what is knowing. That's what 'the eye can't see itself' means. Not understanding that is behind innummerable confusions about the nature of logic and mathematics.

Re geometery - I read a compelling account that the foundations of geometery were laid by the requirement to mark out parcels of land-holdings on the ancient Nile delta for each planting season, after the annual floods had re-arranged the landscape. Makes perfect sense to me. But that still doesn't explain the faculty of being able to count and calculate. As I understand it, Husserl grounds arithmetic in the act of counting. (I have the idea that this actually dovetails with Aquinas' idea of 'being as a verb'. So arithmetic, even though it comprises 'unchanging truths' on the one hand, is also inherently dynamic, in that grasping it is an activity of the intellect.)

Note that chatbots use a mathematics of millions and even billions of 'dimensions.' — plaque flag

I'm having great experiences with ChatGPT4 - it's just amazing for bouncing ideas off and generating other ideas. I call it, not 'artificial' intelligence, but 'augmented' intelligence.

I loved Pinter's book on abstract algebra, and such algebra is a great example of abstraction. Group theory ignores absolutely everything about a system except its satisfaction of a few simple axioms. This allows for a rich theory that applies to all possible groups, even those not yet invented or discovered. But this theory still exists in the world as an intellectual tradition. It uses symbols to support a thinking which is basically immaterial. (I'm not a formalist. Math gives insight.) — plaque flag

Right! I had noticed Pinter's books on abstract algebra, although not being a mathematician, they probably wouldn't mean much to me. But do look at the abstract of his Mind and the Cosmic Order, I'm sure you'd like it.

algebra is a great example of abstraction — plaque flag

Even though this quotation is about geometry and astronomy (as algebra hadn't yet been invented), it still rings true to me:

It is indeed no trifling task, but very difficult to realize that there is in every soul an organ or instrument of knowledge that is purified and kindled afresh by such studies (as geometry and astronomy) when it has been destroyed and blinded by our ordinary pursuits, a faculty whose preservation outweighs ten thousand eyes; for by it only is reality beheld (because by it the eternal principles are beheld). Those who share this faith will think your words superlatively true. But those who have and have had no inkling of it will naturally think them all moonshine. For they can see no other benefit from such pursuits worth mentioning. Decide, then, on the spot, to which party you address yourself. — Republic 527d -

The Mind-Created WorldSpirit is a modification of nature. — plaque flag

On the contrary - doesn't C S Peirce say that 'matter is effete mind'?

So what in the world (but of course not in the world, which is exactly the problem) is left over? — plaque flag

though we know that prior to the evolution of life there must have been a Universe with no intelligent beings in it, or that there are empty rooms with no inhabitants, or objects unseen by any eye — the existence of all such supposedly unseen realities still relies on an implicit perspective. What their existence might be outside of any perspective is meaningless and unintelligible, as a matter of both fact and principle.

Which, now that I reflect further, suggests 'that of which we cannot speak....'

It'd be very un-Kantian to make those faculties more than structures or possibilities of experience. — plaque flag

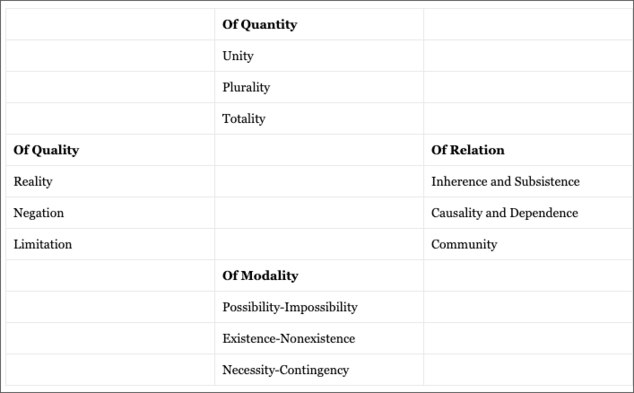

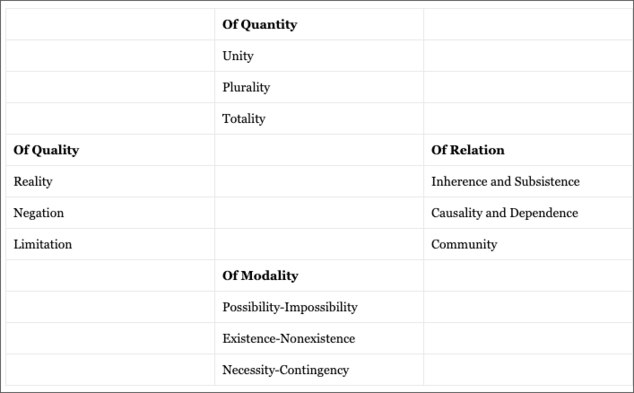

According to IEP, Kant adopted Aristotle's categories, with some slight modifications.

They do indeed 'structure' experience, but they're not derived from experience. That's what makes them 'transcendental'. -

The Mind-Created WorldDon't get too diverted by it, there are many more important points to consider. That was simpy a passing allusion to David Chalmers. It's the connection between 'innateness', mathematical truths and rational principles that is the quarry.

-

The Mind-Created WorldKant didn’t saw off his own branch. — Mww

Exactly as I see it also.

The thinking, presenting subject; there is no such thing.

...

And from nothing in the field of sight can it be concluded that it is seen from an eye ~ Wittgenstein — TLP

I quoted from that in my MA thesis in Buddhist Studies. As I've said before, the self is never an object, yet the reality of the subject of experience ('what it is like to be....') is apodictic, cogito ergo sum. Where in the world is the metaphysical subject to be noted? Why, that would be 'nowhere', yet otherwise there is no world.

The objects of experience then are not things in themselves, but are given only in experience, and have no existence apart from and independently of experience. — Kant

The OP is pretty well an exercise in understanding how this can be true. (A successful one, I would like to think.)

Anyway, I perceive (interpret) this surrounding darkness as a deep blanket of threatening-promising possibility. — plaque flag

I once wrote a rather contemplative piece on the old forum, about how meditation is like learning to see in the dark. The analogy was that conscious thought brings everything into the pool of light around the campfire, but there's an awareness that outside that area there is a landscape and other creatures moving about that we're only dimly aware of and feel threatened by. The idea being that moving away from the pool of light and letting your eyes adjust to the moonlight, so you can see the contours of the landscape.

I think Mill hits the nail on the head on this issue of the I-know-not-what that's supposed to be more than possible or actual experience : some kind of [ aperspectival ] Substance that's hidden forever behind or within whatever actually appears. — plaque flag

Pinter's book, Mind and the Cosmic Order, starts with the British Empiricists, and their insistence that knowledge comes solely from sense experience. But he moves on to Kant who showed that there must be innate faculties :yikes: which organize and categorise sense-data, otherwise we would not be able to make sense of sense.

John Stuart Mill asserted that all knowledge comes to us from observation through the senses. This applies not only to matters of fact, but also to "relations of ideas," as Hume called them: the structures of logic which interpret, organize and abstract observations.

Against this, Kant argued that the structures of logic which organize, interpret and abstract observations were innate to mind and were true and valid a priori ('innateness' being anathema to the empiricists Hume and Mill).

Mill, on the contrary, said that we believe them (i.e. mathematical proofs) to be true because we have enough individual instances of their truth to generalize: in his words, "From instances we have observed, we feel warranted in concluding that what we found true in those instances holds in all similar ones, past, present and future, however numerous they may be".

Although the psychological or epistemological specifics given by Mill through which we build our logical apparatus may not be completely warranted, his explanation still inadevertantly manages to demonstrate that there is no way around Kant’s a priori logic. To restate Mill's original idea: “Indeed, the very principles of logical deduction are true because we observe that using them leads to true conclusions” - which is itself a deductive proposition!

For most mathematicians the empiricist principle that 'all knowledge comes from the senses' contradicts a more basic principle: that mathematical propositions are true independent of the physical world. Everything about a mathematical proposition is independent of what appears to be the physical world. It all takes place in the mind drawn from the infallible principles of deductive logic. It is not influenced by exterior inputs from the physical world, distorted by having to pass through the tentative, contingent universe of the senses. It is internal to thought, as it were. — Scrapbook Entry, from an archived version of the Wikipedia entry on Philosophy of Mathematics

(I'll also add in passing that traditional philosophy sees a relationship between the domain of the apriori and the invariance of scientific laws and regularities - another principle called into question in modern philosophy.) -

Donald Trump (All General Trump Conversations Here)I will acknowledge the rise of an extreme, or alt right-wing in recent years. I would like to hear people’s thoughts for the cause of this rise. Personally, I think the political correctness and the left-lean in most educational and corporate institutions is causing the reaction from young men who do not wish to comply with their ideology. Does anyone else have thoughts on this? — ButyDude

Mainly that the so-called 'right-wing' or 'extreme conservative' reaction is a massive overreaction. I too get pissed off with political correctness in the media, with things you're supposed to believe about various social and political issues, but I don't think that accounts for the extemism that you see in so-called conservative politics (and I say so-called because a lot of it is quite unlike traditional conservatism).

The world is changing at a faster pace than ever before (this is not hyperbole). And we're reading about and dealing with multiple crises - environmental, political and social. Part of that is that the makeup of US society is becoming more diverse and traditions are breaking down all the time. All this is creating huge anxiety, and one of the consequences is something like panic. Trump knows instinctively how to exploit the politics of grievance - he appeals to the feeling of having been wronged, the dread that Government itself is part of the problem. (That's why every indictment feeds the myth!) But the reality is, almost every single thing Trump says is a lie, and that's not a matter of opinion or 'according to whom?' or 'depends on what you mean'. He's a veritable Yellowstone geyser of mendacity, and his lies pollute the public discourse, lead many people astray, and generally create and promote disorder, division, and distrust within and between people. Sooner he's out of the picture, better for everyone. -

The Mind-Created WorldI do have the impression that you are prone to withdraw when the going gets tough. — Janus

It might be a matter of deciding what challenges are worth responding to. There are plenty of times in these debates where people are talking past one another. -

The Mind-Created World.....As I think I've already mentioned either here or some other place - it's something I mention often - the canonical source for the idea of that 'the eye cannot see itself' is not something found in the Western tradition, as far as I'm aware. It's found in the Upaniṣads. There's an erudite and witty French philosopher of science named Michel Bitbol who has written some excellent articles on that point. But it's not something that I think you find in mainstream philosophy or philosophy of science.

I quote Locke and Hobbes to show that Kant is very much part of a sequence, pushing things to the limit, until Fichte and Hegel went all the way, returning to a now sophisticated (direct) realism. Objects do not hide behind themselves. The subject and the object are one. — plaque flag

Again from Eastern philosophy, you will doubtless recall the Zen koan, made into a song, 'first there is a mountain, then there is no mountain, then there is.' That also is about the transition from naive realism (first there is..) to critical philosophy (then there is no...), and the 'return' to seeing 'things as they truly are' (then there is...) -

The Mind-Created WorldWe are such practical, linguistic creatures, then we [ tend ] to 'look right through.' And physical science is a supreme achievement in this direction — plaque flag

I was right with you up until 'physical science'. I want to back up to this point, as it's central to my concerns.

There is an Aeon essay, The Blind Spot of Science is the Neglect of Lived Experience, which I started a thread about here some time back.

When we look at the objects of scientific knowledge, we don’t tend to see the experiences that underpin them. We do not see how experience makes their presence to us possible. Because we lose sight of the necessity of experience, we erect a false idol of science as something that bestows absolute knowledge of reality, independent of how it shows up and how we interact with it. ...

That of course is the main point made by phenomenology. They go on

Scientific materialists will argue that the scientific method enables us to get outside of experience and grasp the world as it is in itself. As will be clear by now, we disagree; indeed, we believe that this way of thinking misrepresents the very method and practice of science.

Which is exactly what I was trying to get at with:

What I’m calling attention to is the tendency to take for granted the reality of the world as it appears to us, without taking into account the role the mind plays in its constitution. This oversight imbues the phenomenal world — the world as it appears to us — with a kind of inherent reality that it doesn’t possess. This in turn leads to the over-valuation of objectivity as the sole criterion for truth. — Wayfarer

(Incidentally, that Aeon essay, by Adam Frank, Marcelo Gleiser, and Evan Thompson, is to be published as a book in March next year.)

This is in line with my view... — plaque flag

I tend to agree.... — plaque flag

Well, that's a relief! I'll take my wins wherever I can get 'em ;-) -

Dualism and InteractionismPlease expand on why you disagree. — Dfpolis

OK, here is the question that has occupied my philosophical quest for decades. It concerns the reality of universals. With your background and interests, I presume you hold to realism concerning universals. Am I right in that? What interests me is what it means to say that universals are real - because they don't exist as do phenomenal objects (the proverbial rocks, apples and trees.) Do you see what I'm getting at? Is this a topic for discussion in the sources you're aware of? -

The Mind-Created WorldWe are such practical, linguistic creatures, then we ought to 'look right through.' And physical science is a supreme achievement in this direction. — plaque flag

Except for the blind spot of science, which ironically is a product of that same tendency not to be aware of our own seeing. Isn't that the main point of Husserl's critique of naturalism? -

The Mind-Created Worldbeing prepared to sustain engagement as long as is required to either arrive at agreement or agreement to disagree. — Janus

I don't think I can be accused of dodging. I write a lot of responses.

What I mean by such realism (the kind I reject) is the postulation of 'aperspectival stuff' being primary in some sense, existing in contrast to ( and prior to ) mind or consciousness. — plaque flag

That's pretty well what I'm also rejecting.

Metaphysically, realism is committed to the mind-independent existence of the world investigated by the sciences. This idea is best clarified in contrast with positions that deny it. For instance, it is denied by any position that falls under the traditional heading of “idealism”, including some forms of phenomenology, according to which there is no world external to and thus independent of the mind. — plaque flag

:up: But the way I have worded the OP, I'm trying to avoid the implication of non-perceived objects ceasing to exist, so as to avoid the necessity of positing a 'Divine Intellect' which maintains them in existence (per Berkeley).

consciousness is just the being of the world given 'perspectively ' — plaque flag

I've always thought that the designation of humans as 'beings' carries that implication. -

Dualism and InteractionismThe blueprint, or design of the thing, as a form, is actual and prior to the individual material thing. — Metaphysician Undercover

I believe this is the point already addressed:

If it were a separate entity, we would have dualism. It is not. A "principle" is the source (arche) of a concept. — Dfpolis

The form, idea or principle is not something that exists - at least, in the sense that a particular exists. The intelligible form of particulars is a universal.

Which leads me to this:

A thing is necessarily the thing which it is and cannot not be the thing it is, by the law of identity. — Metaphysician Undercover

In Aristotelian and classical philosophy, the law of identity is a logical law that is general and not tied specifically to particulars.

We've argued about that many times, I'd be interested in @Dfpolis' interpretation. -

The Mind-Created WorldI'm obviously not condemning reading other philosophers, but surely if we have mastered their arguments, we can present them in our own words — Janus

I did that in the OP. I provide the passage about Schopenhauer's philosophy by way of showing points of agreement with at least one historic philosopher. -

The Mind-Created WorldKant's radicality makes the brain itself a mere piece of appearance, not to be trusted. He saws off the branch he's sitting on. — plaque flag

He doesn't have to anything to say about the brain, in his day the physiology of the brain was pretty well completely unknown, but he does no such thing. Please take some time to read through the passages that I posted just before the one from Sartre. -

The Mind-Created WorldKant casts into doubt all of our basic, ordinary understanding. — plaque flag

Kant calls into question the 'the inborn realism which arises from the original disposition of the intellect'. That is why it produces such hostile reactions - it challenges our view of reality.

Wayfarer

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum