-

The Mind-Created WorldThe disagreement is always over their precise nature. One groups says that the rational entity prevents us from knowing reality as it is in itself; the other group says that it does not. — Leontiskos

The problem there is that you're trying to assume a perspective outside both, in order to arrive at which one of the two is correct. And I don't think that can be done, in this case. (Oh, and Plaque Flag and I go back at least 10 years now. He's a very interesting contributor, although somewhat prone to digression ;-) ) -

The Mind-Created WorldWhat I’m calling attention to is the tendency to take for granted the reality of the world as it appears to us, without taking into account the role the mind plays in its constitution....

— Wayfarer

I think this is so by design, because otherwise, any kind of normativity is impossible. — baker

Not so. It is specific feature of modern and post-industrial culture with its emphasis on scientific instrumentalism. In earlier cultures, the 'is/ought' gap had not yet appeared, because it was presumed that what one ought to do, and what is the case, are connected: 'In the Indian context it would have been axiomatic that liberation comes from discerning how things actually are, the true nature of things. That seeing things how they are has soteriological benefits would have been expected, and is just another way of articulating the ‘is’ and ‘ought’ dimension of Indian Dharma. The ‘ought’ (pragmatic benefit) is never cut adrift from the ‘is’ (cognitive factual truth).'

but that, absent an observer, whatever exists is unintelligible and meaningless as a matter of fact and principle.

— Wayfarer

How do you propose to build a system of morality based on the above idea? — baker

Many pre-modern moral systems never doubted it - the idea that the universe comprises dumb stuff directed solely by physical forces is a very recent one. (It has always been around, but had never before become dominant.) -

The Mind-Created WorldHusserl's notion of the transcendence of the object is helpful here. — plaque flag

As also his depiction of 'the natural attitude', which I see as the basis the objections thus far:

From a phenomenological perspective, in everyday life, we see the objects of our experience such as physical objects, other people, and even ideas as simply real and straightforwardly existent. In other words, they are “just there.” We don’t question their existence; we view them as facts.

When we leave our house in the morning, we take the objects we see around us as simply real, factual things—this tree, neighboring buildings, cars, etc. This attitude or perspective, which is usually unrecognized as a perspective, Edmund Husserl terms the “natural attitude” or the “natural theoretical attitude.”

When Husserl uses the word “natural” to describe this attitude, he doesn’t mean that it is “good” (or bad), he means simply that this way of seeing reflects an “everyday” or “ordinary” way of being-in-the-world. When I see the world within this natural attitude, I am solely aware of what is factually present to me. My surrounding world, viewed naturally, is the familiar world, the domain of my everyday life. Why is this a problem?

From a phenomenological perspective, this naturalizing attitude conceals a profound naïveté. Husserl claimed that “being” can never be collapsed entirely into being in the empirical world: any instance of actual being, he argued, is necessarily encountered upon a horizon that encompasses facticity but is larger than facticity. Indeed, the very sense of facts of consciousness as such, from a phenomenological perspective, depends on a wider horizon of consciousness that usually remains unexamined. — Key Ideas in Phenomenology

I explicitly disagreed with Pinter's claim that objects in the unobserved universe have no shape, and you agreed with my argument. We agreed that unobserved boulders have shape. Or rather, so as not to put words in your mouth, you said, "It's safe to assume." — Leontiskos

'No features', is the expression Charles Pinter uses - shape being one. Features correspond to functions of the animal sensorium, but this thesis is developed over several chapters, and not one I can summarise in a few words.

I acknowledge at the outset that the universe pre-exists us: 'though we know that prior to the evolution of life there must have been a Universe with no intelligent beings in it, or that there are empty rooms with no inhabitants, or objects unseen by any eye — the existence of all such supposedly unseen realities still relies on an implicit perspective.'

I think it's the idea of 'an implicit perspective' that you're calling into question. -

The Mind-Created WorldBut Pinter's featureless stuff here is empty of content — plaque flag

Of course! That's the point!

In a universe without an observer having a purpose, you cannot have facts. As you may judge from this, a fact is something far more complex than it appears to be at first sight. In order for a fact to exist, it must be preceded by a segmentation of the world into separate things, and requires a brain that is able to extract it from the background in which it is immersed*. Moreover, this brain must have the power to conceive in Gestalts, because in order to perceive its outlines and extract it, a fact must be seen whole, together with some of its context.

A fact does not exist if it has not been articulated, that is, if it does not exist explicitly as a verbal entity sufficiently detailed that it can be made to correspond (approximately) to something in the external world. Facts don’t exist in the absence of their statement (because a statement cuts the fact out of the background), and the statement cannot exist apart from an agent with a purpose. When an intentional agent sets out to carve a specific object from the background world, he has a Gestalt concept of the object—and from the latter, he acts to carve the object out. Thus, a fact cannot exist in a universe without living observers.

A fact does not hold in the universe if it has not been explicitly formulated. That should be obvious, because a fact is specific. In other words, statements-of-fact are produced by living observers, and thereby come into existence as a result of being constructed. It is only after they have been constructed (in words or symbols) that facts come to exist. Commonsense wisdom holds the opposite view: It holds that facts exist in the universe regardless of whether anyone notices them, and irrespective of whether they have been articulated in words. You may now judge for yourself if that is true. — Pinter, Charles. Mind and the Cosmic Order (p. 93). Springer International Publishing. Kindle Edition

Pinter, Charles. Mind and the Cosmic Order (p. 93). Springer International Publishing. Kindle Edition.

*That is what I mean by 'existence being complex'. It's a manifold, not an off/on phenomenon.

So, facts come into being with us. Not 'the universe', but there is no meaningful sense of existence in the universe prior to this act of formulation (as naturalism never tires of telling us). -

The Mind-Created WorldIt's worth watching the video I posted a couple of times, Is Reality Real? The opening line is, 'is there an external reality? Of course there is an external reality! We just don't see it as it is.'

Then have a look at Mind and the Cosmic Order, by Charles Pinter. Chapter 1 abstract is:

Let’s begin with a thought-experiment: Imagine that all life has vanished from the universe, but everything else is undisturbed. Matter is scattered about in space in the same way as it is now, there is sunlight, there are stars, planets and galaxies—but all of it is unseen. There is no human or animal eye to cast a glance at objects, hence nothing is discerned, recognized or even noticed. Objects in the unobserved universe have no shape, color or individual appearance, because shape and appearance are created by minds. Nor do they have features, because features correspond to categories of animal sensation. This is the way the early universe was before the emergence of life—and the way the present universe is outside the view of any observer.

Note the similarity with my ‘meadow’ analogy.

So that's the sense in which I'm 'anti-realist' - it's because I recognise that what we take to be inherently real is, let’s say, a representation that has been re-constituted by our cognitive system. According to Arthur Schopenhauer, in the opening paragraph of WWI, recognising this is ‘the beginning of wisdom’. And I think it’s validated by cognitive science, although they may of course have a completely different view of the philosophical implications. -

The Mind-Created World(Oh dear, can let this one go by. I've added the qualifiers in square brackets, I trust this is as you intended? )

Recall that the central issue here is whether we can know mind-independent reality as it is in itself. The first person in my analogy [i.e. 'Kantian'] represents those who say that we cannot, whereas the second [i.e. 'empirical realist'] represents those who say that we can. I don't think anything you've noted about Kant moves him away from that first group, does it? — Leontiskos

It doesn't, but that is not the point. Surely the point is how to adjuticate which is correct? Kantian, or empirical realist? If you're supporting the latter, then the case has to be made as to why that is correct, and the Kantian view wrong. -

The Mind-Created Worldobjectivity is something which inheres within the judgement, not within the object. — Metaphysician Undercover

Let's consider the case of bona fide COVID vaccines vs quack cures such as hydroxychloroquine. Scientific studies show that the former are effective and the latter not. That is because of the inherent properties of the real vaccines, which the quack cures do not possess.

On the other hand, there's the interesting case of placebo cures. It is abundantly documented that placebos will often effect a cure even absent any actual medical ingredient in the tablet. In that case subjective factors, namely, the subject's confidence in the efficacy of cure, has objective consequences, namely, healing or cure.

So none of this open and shut. As the closing quote says in the essay ''Ultimately, what we call “reality” is so deeply suffused with mind- and language-dependent structures that it is altogether impossible to make a neat distinction between those parts of our beliefs that reflect the world “in itself” and those parts of our beliefs that simply express “our conceptual contribution.” The very idea that our cognition should be nothing but a re-presentation of something mind-independent consequently has to be abandoned.’

Even so, there are many things, like medicines, that are shown to be effective by objective measures. It's important to acknowledge that, lest you slide into out-and-out relativism. -

Israel killing civilians in Gaza and the West BankThis situation is frickin' terrifying. Commentary from US media has pointed out that Iran is almost certainly involved in this attack - on 3rd Oct Ayatollah Khamenei posted an anticipatory tweet, commending the fighting spirit of the Palestinian jihadis and assuring them that they would be successul in destroying the invaders (that is, Israel). And the commentary pointed to the huge number of missiles that have been deployed, and the tactics and strategies that have never previously been available to Hamas. Meanwhile it suits Putin down to the ground to have this flare up, it will divert attention and possibly arms from his illegal war. If Hezbollah gets involved and the conflict spreads God help all of us.

-

The Mind-Created WorldI think the glass example should have illustrated that, for surely there is no reason why the person who says that everything viewed through the glass has a glassy aspect is necessarily committed to the position which says that the viewed objects do not exist. — Leontiskos

But I don't see that as a valid analogy for what Kant's idealism says. Kant's view is that we never know [the object] as it is in itself (ding an sich). Instead, we only know [the object] as it appears to us (the phenomena, meaning appearance), and this appearance is inextricably a product of the inherent structures of the mind (the primary intuitions of space and time and the categories of understanding). That is always the case for empirical (or sensory) knowledge. So the mind is not just a passive recipient of sensory data; it actively shapes and structures our experience. It is, I would aver, an agent.

The analogy's issue is that Kant doesn't merely claim the "glass" (our cognitive faculties) is translucent. Instead, Kant argues that our cognitive faculties play an active role in constituting our experience, not merely transmitting it. It's as if the glass doesn't just let us see the world but actively shapes, organizes, and structures what we see based on its inherent properties. So it's better compared to spectacles, which focus light so we can recognise what we're looking at. If your natural vision was poor, then without them you can't see anything but blurs.

That can be extended to argue that Kant's critical project was actually to learn to look AT your spectacles, not just THROUGH them - to turn our attention away from objects of knowledge and direct it towards the conditions that make knowledge possible ('knowing about knowing'). Instead of merely accepting our experiences at apparent value, Kant investigates the faculties and structures that underlie experience.

How would you differentiate a case where there is a mind involved, from a case where there is not?

— Wayfarer

I think the easiest way is to follow your lead and talk about a pre-human age. Or a post-human age. — Leontiskos

I did explicitly discuss that under the second heading.

I sense we're talking past each other here, so I'm happy to leave it at that, unless you have more issues you'd like to discuss. -

The Mind-Created WorldHaven't we already agreed <that it is likely false> that "boulders will only treat cracks differently than canyons when a mind is involved"? — Leontiskos

How would you differentiate a case where there is a mind involved, from a case where there is not? -

The Mind-Created WorldTouch a stone and you will know right there and then that the feeling that something is impenetrable in/of it can not be reduced to the plurality of the matter of the experience (sensation: touch), yet since all you have (in the totality of your being) is either a. experience or b. abstraction it can not precede the experience, EVEN if the concept itself of impenetrability is a priori. — Julian August

:chin:

I suppose you're familiar with the 'argument from the stone', which is based on Samuel Johnson's response to one of Bishop Berkeley's lectures? -

The Mind-Created WorldThey might say it in hindsight, but the point was, they couldn't have imagined it happening before it happened. Anyway, it's pretty tangential to the discussion.

-

The Mind-Created WorldWould it be possible to imagine something that you have never seen or experienced in your life before, or places that you have never visited in real life? — Corvus

Imagination is an infinitely resourceful faculty. On the other hand, people do sometimes say they have encountered something, or something has happened to them, which was 'unimagineable' - 'I never imagined that would happen!' -

Teleology and InstrumentalityUseful discussion of Aristotle's telos in the IEP.

The word telos means something like purpose, or goal, or final end. According to Aristotle, everything has a purpose or final end. If we want to understand what something is, it must be understood in terms of that end, which we can discover through careful study. It is perhaps easiest to understand what a telos is by looking first at objects created by human beings. Consider a knife. If you wanted to describe a knife, you would talk about its size, and its shape, and what it is made out of, among other things. But Aristotle believes that you would also, as part of your description, have to say that it is made to cut things. And when you did, you would be describing its telos. The knife’s purpose, or reason for existing, is to cut things. And Aristotle would say that unless you included that telos in your description, you wouldn’t really have described – or understood – the knife. This is true not only of things made by humans, but of plants and animals as well. If you were to fully describe an acorn, you would include in your description that it will become an oak tree in the natural course of things – so acorns too have a telos. Suppose you were to describe an animal, like a thoroughbred foal. You would talk about its size, say it has four legs and hair, and a tail. Eventually you would say that it is meant to run fast. This is the horse’s telos, or purpose. If nothing thwarts that purpose, the young horse will indeed become a fast runner.

It's the basis of the idea of final cause, the end to which something is directed. Counter-intuitively, for instance, the final cause of a match is fire (because matches exist to start fires) whilst the efficient case of fire is the match. Generally speaking, since the overthrow of Aristotelian physics by Galileo, the concept of telos and teleology has fallen into disrepute, although I've read that philosophy of biology has found reasons to want to resurrect the idea of final cause. -

The Mind-Created WorldWithout some angel in the shell we are nothing but meaty robots, or an animal not much different than all others—just an object, like a stone. — NOS4A2

Thereby absolving us of all responsibility as moral agents.

Apparently. -

The Mind-Created WorldHumans are naturally endowed with a relational intellect, for which the capacity, as function, for discernment is integrated necessarily, but in doing so, in enacting, as operation, the functional capacity, re: being able to discern, there must already be that which serves as ideal against which the content under discernment is complementary. — Mww

Which in the Christian world, would amount to the faculty of conscience, grounded in faith in the Divine Word, which provides the criteria against which to make such judgements. But, of course, Kant was preparing the ground for a post-Christian world and trying to sieve universal principles of morality out of the wreckage of the collapsed Medieval Synthesis. Anyway, as we both agree, a diversion to this particular topic, perhaps more suited to a thread on Ethics. Thank you as always for your insightful contributions.

It seems like you are not distinguishing between the judgement itself, and what the judgement is about. Yes, the judgement is about an object, and it may be a judgement about what inheres within the object, but the judgement is not inherent in the object, and therefore cannot be "objective" by the definition you provided. — Metaphysician Undercover

It is objective to all intents and purposes (i.e. empirically) but also ultimately requires that there is a subject who judges (transcendentally ideal). -

The Mind-Created WorldBut you seem to be holding to two conflicting principles. Either the mind can know mind-independent reality as it is in itself, or it cannot — Leontiskos

I think I understand what you're seeing as a conflict. You think that what I'm saying must necessarily entail that 'the unobserved object doesn't exist'. But what I wrote was 'to think about the existence of a particular thing in polar terms — that it either exists or does not exist — is a simplistic view of what existence entails. This is why the criticism of idealism that ‘particular things must go in and out of existence depending on whether they’re perceived’ is mistaken. It is based on a fallacious idea of what it means for something to exist. The idea that things ‘go out of existence’ when not perceived, is really their ‘imagined non-existence’ - your imagining that they don't exist. In reality, the supposed ‘unperceived object’ neither exists nor does not exist. Nothing whatever can be said about it.'

In the Medium version there is a supporting footnote:

‘By and large, Kaccayana, this world is supported by a polarity, that of existence and non-existence. But when one sees the origination of the world as it actually is with right discernment, “non-existence” with reference to the world does not occur to one. When one sees the cessation of the world as it actually is with right discernment, “existence” with reference to the world does not occur to one.’ ~ The Buddha, Kaccāyanagotta Sutta.

I'm sympathetic to the scientists, and I'm not very impressed with post-Kantian philosophy. I'm not convinced that any philosophy that takes Hume or Kant's starting point has ever worked, or ever will work, even if that starting error is mitigated as far as possible. — Leontiskos

Hume and Kant are chalk and cheese.

I think that physics has validated Kant's attitude in many respects. Many of Bohr's aphorisms seem to support it: 'It is wrong to think that the task of physics is to find out how Nature is. Physics concerns what we can say about Nature.' Likewise from Heisenberg 'What we observe is not nature in itself but nature exposed to our method of questioning.' Then you have Wheeler’s model of the participatory universe, suggesting that the universe is incomplete without the participation of observers—essentially, that our observations help to bring the universe into existence (see the quotation from cosmologist Andrei Linde in this thread.)

"Opposing various forms of idealism, I would claim that reality exists and minds are able to know it. This is not to say that all knowledge is objective, but lots of it is" — Leontiskos

As I've said, I don't take issue with the objective facts (and besides, where to draw the line? What is 'lots'?). The question is one of interpretation.

As far as I can tell, that's analogous to the argument over the intellect between Realists and Anti-Realists. — Leontiskos

All due respect, it is not analogous, but is a misreading. I do understand that Kant's 'ding an sich' has been ferociously criticized (including by Schopenhauer) but I've previously referred to my prefered reading:

Kant's introduced the concept of the “thing in itself” to refer to reality as it is independent of our experience of it and unstructured by our cognitive constitution. The concept was harshly criticized in his own time and has been lambasted by generations of critics since. A standard objection to the notion is that Kant has no business positing it given his insistence that we can only know what lies within the limits of possible experience. But a more sympathetic reading is to see the concept of the “thing in itself” as a sort of placeholder in Kant's system; it both marks the limits of what we can know and expresses a sense of mystery that cannot be dissolved, the sense of mystery that underlies our unanswerable questions. Through both of these functions it serves to keep us humble. — Emrys Westacott, The Continuing Relevance of Immanuel Kant

these relative sizes will hold good whether or not they are measured — Leontiskos

And as I say, all such statements still carry an implicit perspective. As soon as you posit such a hypothetical you have created as what phenomenology calls 'the intentional object'*. This exists as a possibility within your mind. Then empirical investigation may confirm or disconfirm that posit.

I'm very interested in pursuing the discussion about Aquinas, but it's a separate topic, and one that I'm preparing further material on. A preview on Medium, The Ligatures of Reason (defending Platonic realism).

------

* The intentional object is not necessarily a real or actual object in the external world. Instead, it refers to the content or the "what" of a conscious act. -

Joe Biden (+General Biden/Harris Administration)Obama has failed to be a transformational leader. — Echarmion

Alternatively, all we've been seeing since is the backlash. The transformation being resisted. -

Joe Biden (+General Biden/Harris Administration)I'm surprised the Dems voted for removal TBH. It would have been a good move towards forcing the GOP towards the sort of compromise politics they should be pursuing considering they hold just one chamber and on razor thin margins. — Count Timothy von Icarus

But that would have been dead in the water. Gaetz said before the vote, 'If the Democrats want him, they can have him.' So if he had been 'saved' by the Democrats, then he would have had even less sway with the MAGA faction than he had already had. And, as you note, McCarthy had already reneged on various deals to placate the fanatics, AND launched a groundless impeachment enquiry against Biden with no floor vote (in blatant contradiction of his own protests about Pelosi doing the same against Trump after the infamous 'Ukraine shake-down' call). It would have been beyond the pale for the Dems to have stepped in. -

Teleology and InstrumentalityIt's one of the main theme's of Mind and Cosmos. As I mentioned, it's a very short book and more than pays back the time invested to read it. — Pantagruel

:100: -

The Mind-Created WorldSo you are saying that boulders will only treat cracks differently than canyons when a mind is involved? — Leontiskos

I was going to also add, that measurements of space and distance are also implicitly perspectival. You could, theoretically, conceive of the distance between two points from a cosmic perspective, against which it is infinitesimally small, and a subatomic perspective, against which it is infinitesimally large. As it happens, all of the units of measurement we utilise, such as years or hours, for time, and meters or parsecs, for space, ultimately derive from the human scale - a year being, for instance, the time taken for the earth to orbit the sun, and so on. Given those parameters, of course it is true that measures hold good independently of any mind, but there was a mind involved in making the measurement at the outset. -

The Mind-Created WorldI always thought the maxim 'know thyself' was simply about seeing through your own delusions and false hopes.

— Wayfarer

…..which, of course, presupposes knowing what they are, by the subject, or self, effected by them. — Mww

Being able to discern delusions and false hopes is not a tall order, is it? It’s obvious that a lot of people don’t do that, or aren’t capable of it. But I associate the saying ‘know thyself’ with Socrates (although of course the Delphic maxim preceded him), and his quest for understanding piety, justice, goodness, and so on, seems to me to clearly require a deep kind of self-awareness, doesn’t it? (A digression perhaps but a worthy one.) -

Teleology and InstrumentalityThomas Nagel has some really good descriptions of the ways in which reality seems to have fundamentally teleological aspects. — Pantagruel

Where, in particular? I’ve read some of his work, which has impressed me deeply, but I can’t recall this discussion in particular (although I do know that the idea of ‘the universe become self aware’ was part of his Mind and Cosmos.)

Instrumentality is the translation of an abstract into a concrete idea, — Pantagruel

I was under the impression that ‘the instrumentalising of reason’ was a criticism of post-Enlightenment philosophy by the New Left. I can’t see how instrumentality is tied to Aristotle’s idea of telos. -

The Mind-Created WorldSo, let's take the neutral "thing" or "stuff", whatever it out-there is, in part, responsible for how we take these objects to be, they stimulate us into reacting as-if, external objects existed. — Manuel

Sure, 100%. I’m not claiming that ‘the world is only in your mind’. If you look at the cognitive scientists who appear in the BigThink video I posted ‘Is Reality Real?’ all of them start by saying, of course there is a world out there. It’s just that we don’t see it as it truly is (but, the Kantian philosopher would say, only as it appears to us.) -

The Mind-Created WorldIt's often helpful to place the two things side by side and assess our certainty:

Boulders will treat cracks differently than canyons whether or not a mind is involved.

Boulders will only treat cracks differently than canyons when a mind is involved.

I'd say we have a great deal more certainty of (1) than (2), and you seem to agree. — Leontiskos

As I said in the OP ‘there is no need for me to deny that the Universe (or: any object) is real independently of your mind or mine, or of any specific, individual mind. Put another way, it is empirically true that the Universe exists independently of any particular mind. But what we know of its existence is inextricably bound by and to the mind we have, and so, in that sense, reality is not straightforwardly objective. It is not solely constituted by objects and their relations. Reality has an inextricably mental aspect…’

…which is introduced as soon as you make any hypothetical object the subject of a proposition. -

The Mind-Created WorldI suppose ‘smaller’ and ‘larger’ are a priori categories, though, so larger things cannot fit into smaller spaces deductively not inductively. (But that’s it for now, I’ll be away for rest of day.)

-

The Mind-Created WorldSo you are saying that boulders will only treat cracks differently than canyons when a mind is involved? — Leontiskos

It’s safe to assume not, but then it is an empirical matter isn’t it? But then I am at pains to say that I have no need to call empirical facts into question. -

The Mind-Created WorldPresupposing naturalism for the moment. — Leontiskos

It’s the natural thing to do!

But is my claim about the boulder meaningless and unintelligible outside of any perspective? Does not the idea that a boulder has a shape transcend perspective? — Leontiskos

Yes and no respectively. Is ‘shape’ meaningful outside any reference to visual perception? We see shapes because it is essential to navigating the environment - Pinter shows this is true even for insects. -

The Mind-Created WorldI don’t know if I said ‘there are no mind-independent objects’, although I suppose it is something that can be justified in Schopenhauer’s philosophical framework, for which ‘there are no objects without subjects’. So I suppose it is a reasonable inference. But the way I put it was this: ‘I am not arguing that [idealism] means that ‘the world is all in the mind’. It’s rather that, whatever judgements are made about the world, the mind provides the framework within which such judgements are meaningful. So though we know that prior to the evolution of life there must have been a Universe with no intelligent beings in it, or that there are empty rooms with no inhabitants, or objects unseen by any eye — the existence of all such supposedly unseen realities still relies on an implicit perspective. What their existence might be outside of any perspective is meaningless and unintelligible, as a matter of both fact and principle.’

I feel as though your response is made on the basis of a step after the suppositions that inform mine. You’re saying that given that objects exist - boulders, canyons, and so on - then we can say….

Whereas the thrust of the argument I’m offering is solely to call attention to the role that the mind plays in any and all judgements about supposedly external objects. I’m not saying that, outside our perception, things don’t exist but that any judgement of existence or non-existence is just that - a judgement.

As for realism, the point about modern realism is that assumes the reality of mind-independent empirical objects.That’s where the problem lies, as empirical objects are by their nature necessarily contingent. Scholastic realism on the other hand presumes the mind-independent reality of the Forms - these are independent of particular minds, but can only be grasped by a mind. That is where I’m coming to in my analysis. -

The Mind-Created WorldYou define it as "inherent in the object". But according to the article of the op, the human mind has no access to what is "inherent in the object". — Metaphysician Undercover

I don't say 'the mind has no access to what is inherent in the object'. Plainly if my shower is too hot, I won't get in it, if my meal is cold, I won't eat it. They are objective judgements. As I say at the outset, I'm not disputing scientific judgements, but calling into question what they're taken to imply. It is especially pernicious when humans and other sentient beings are treated as objects, as if the objective analyses provided by evolutionary biology and the other sciences have the final say on human nature. Beings are subjects of experience, and as such their true nature is beyond the purview of the objective sciences.

I like to read this in terms of the famous ontological difference, in terms of being itself not being an entity ---though of course the concept of being itself is indeed an entity. — plaque flag

Quite! Some aspects of Heidegger have seeped through to me, although I've never bitten the bullet of doing the readings. I have been accused in the past of engaging in ‘onto-theology’. One thing I did read about Heidegger is the anecdote of a colleague of his finding him reading D T Suzuki, and admitting, ‘If I understand this man correctly, it is just what I’ve been trying to say’ or something along those lines. Not that he would ever endorse the adoption of Buddhism as a matter of practice.

It's a bit like moving from the extreme of nominalism to the extreme of Platonic idealism — Leontiskos

Oh, I don’t know. If you read on to the section about Pinter’s book Mind and the Cosmic Order, he says there are quite valid scientific grounds for his proposals, which I hope my arguments conform with.

I’m not saying that everything is a matter of perspective, but that no judgement about what exists can be made outside a perspective. If you try and imagine what exists outside perspective, then you’re already positing an intentional object.

I don’t think of myself as a subject or the world as an object when a I’m cooking dinner. — Mikie

There’s no need to, but I think the distinction between self and other is nevertheless basic to consciousness, isn’t it?

I'm surprised that consciousness is totally absent in your description of the topic — Alkis Piskas

Thanks for your feedback!

That’s because for my purposes I’m treating ‘mind’ and ‘consciousness’ as synonyms. They’re not always synonyms, for instance in some medical or psychological contexts, but for my purposes. And yes, I have framed the question in terms of idealism and materialism, as I see that as the underlying dynamic that is playing out in the debates. There are many varieties of each of course.

This is clearly a physicalist/materialist view. It belongs to Science and its materialist view of the world. — Alkis Piskas

Not at all! I think many elements within science itself are actually starting to diverge from a materialist view of the world. I actually address that objection in the extended version of the essay. Both neuroscience and physics have tended to call into question the modern understanding of realism.

And this sort of thinking seems to make it easy to fall into circles asking about what things are maps and what things are territories. — Count Timothy von Icarus

We need to understand the ‘mind-making’ process on a practical level - actually grasp how the mind is doing that. Otherwise, you do really have ‘the hand trying to grasp itself’!

Are the contents of experience just what we experience? — Count Timothy von Icarus

‘The content of consciousness is consciousness’ ~ J Krishnamurti. -

Joe Biden (+General Biden/Harris Administration)What Michael says. He's a ignorant blowhard and diehard partisan.

-

The Mind-Created WorldIt is impossible to understand what is happening without recourse to the fact that the cell treats itself as a separate whole in its responses. It is already the subject of its actions. Note that nothing has been said yet about awareness or experience; theses are other levels of complexity that can only be built upon an organisms pre-existing and more fundamental subjectivity. — unenlightened

Very well said. That's the sense in which otherness is fundamental to any kind of life-form. Because it essentially recognises in some basic way the distinction of self from other. 'Alterity is the basic condition of existence'. -

The Mind-Created WorldI agree that reality is not "straightforwardly objective," but more because of general confusion over what the term "objective," means. It seems to me like there is a strong tendency to conflate the "objective world," with something like Kant's noumenal realm. — Count Timothy von Icarus

First, thanks for the positive feedback. :pray: You've covered a lot in your comments, I will do my best to respond.

I take the term 'objective' at face value, that is, 'inherent in the object'. Seems to me that estimation of objectivity as the main criterion for truth parallels the emergence of science, which really is kind of obvious. Remember Carl Sagan's 'Cosmos is all there is'? By that he means, I think, the Cosmos qua object of science. So the overestimation of objectivity in questions of philosophy amounts to a bias of sorts (per Kierkegaard 'Concluding Non-scientific Postscript'.) At any rate, as far as today's popular wisdom is concerned, as the domain of the transcendent is generally discounted, objectivity is presumptively the only remaining criteria. I don't hold to relativism, I think objectivity is extremely important in many domains but that there are vital questions the answer to which may not necessarily be sought in solely objective terms. So anything to be considered real has to be 'out there somewhere', existing in time and space. (This shows up in debates of platonic realism.) The ways-of-thought that accomodate the transcendent realm have by and large been abandoned in secular philosophy.

If you recognize how intricately connected cause and the process of local becoming is, it becomes silly to talk of things we know to exist "not being observed and so disappearing." — Count Timothy von Icarus

Well, true enough, but let's not forget Samuel Johnson's 'argument from the stone' - when he kicked a stone to purportedly demonstrate the falsehood of Berkeley's arguments for immaterialism. Even though it has been pointed out ad nauseum that Berkeley doesn't deny the apparent reality of stones, but only their existence independently of the perception of them, the 'argument from the stone', or similar are frequently used against idealism. I know there are many here who can't see how idealism doesn't imply things going in and out of existence depending on whether they're perceived or not, which is why I made a point of mentioning it.

"Reality has an inextricably mental aspect, which itself is never revealed in empirical analysis."

I'm not totally sure what is meant here. Are minds not objects that have relations, or is it only the individual's mind that is not an object to itself? — Count Timothy von Icarus

I'm inclined to say that the mind is never an object, although that usually provokes a lot of criticism. I've long been persuaded by a specific idea from Indian philosophy, namely, that the 'eye cannot see itself, the hand cannot grasp itself. The 'inextricably mental' aspect is simply 'the act of seeing'. Perhaps I might quote a translation of the passage in question. This is from a dialogue in the Upaniṣads where a sage answers questions about the nature of ātman (the Self).

Yājñavalkya says: "You tell me that I have to point out the Self as if it is a cow or a horse. Not possible! It is not an object like a horse or a cow. I cannot say, 'here is the ātman; here is the Self'. It is not possible because you cannot see the seer of seeing. The seer can see that which is other than the Seer, or the act of seeing. An object outside the seer can be beheld by the seer. How can the seer see himself? How is it possible? You cannot see the seer of seeing. You cannot hear the hearer of hearing. You cannot think the Thinker of thinking. You cannot understand the Understander of understanding. That is the ātman."

Nobody can know the ātman inasmuch as the ātman is the Knower of all things. So, no question regarding the ātman can be put, such as "What is the ātman?' 'Show it to me', etc. You cannot show the ātman because the Shower is the ātman; the Experiencer is the ātman; the Seer is the ātman; the Functioner in every respect through the senses or the mind or the intellect is the ātman. As the basic Residue of Reality in every individual is the ātman, how can we go behind It and say, 'This is the ātman?' Therefore, the question is impertinent and inadmissible. The reason is clear. It is the Self. It is not an object. — Brihadaranyaka Upaniṣad

I'm not advocating 'belief in ātman' but as I say in the OP, it's a matter of perspective - the mind is never something we can get outside of or apart from. But I understand that this is difficult perspectival shift to make. It's something very like a gestalt shift. It might have been owed in part to my long-standing practise of zazen, Buddhist meditation, by which means insight arises into the world-making activities of the mind. This point is also central to the 'argument from the blind spot of science' that I often mention - no coincidence that Adam Frank, one of the authors, is a long time Zen practitioner.

However, it seems possible to me that there might be distant processes that are far enough away from any minds that the goings on within them are quite irrelevant to any experiences. But I would still say its possible for these processes to exist. — Count Timothy von Icarus

But notice that as soon as you invoke them or gesture towards them, then already 'mind' is involved. All such conjectures are variations on the sound of the unseen falling tree.

But what we know of its existence is inextricably bound by and to the mind we have, and so, in that sense, reality is not straightforwardly objective. It is not solely constituted by objects and their relations. Reality has an inextricably mental aspect, which itself is never revealed in empirical analysis. Whatever experience we have or knowledge we possess, it always occurs to a subject — a subject which only ever appears as us, as subject, not to us, as object.

Is this not assuming the subject/object dichotomy? — Mikie

First, thank you for the positive feedback.

The subject-object relationship is a fact of life, even in simple life-forms. Individualism tends towards a kind of atomised individuality, we're all separated selves and everything is interpreted through the subject-object dichotomy. What I'm proposing is aimed at transcending that divided way of being by getting insight into it and the role of the mind in engendering it.

As for Kant, I always feel as though my understanding of him is incomplete - there's so much more to know about him. I first encountered Kant through a mid-20th century book The Central Philosophy of Buddhism, T R V Murti, which has extensive comparisions between Buddhist philosophy (specifically Madhyamaka or 'middle-way) and Kant, Hegel, Hume, Bradley and others. According to Murti, the parallels between Kant and Buddhist philosophy are especially striking. It was one of those books which was formative for me, because it enabled me to understand Kant on a kind of experiential level at the same time I had a conversion experience to Buddhism.

No, that one passed me by. I did read part of his follow-up, People of the Lie, but I didn't like it nearly as much as the first.Did you read The Different Drum? — wonderer1

Thanks for those passages, as you say, these questions have occupied many a philosopher. I do see some parallels there. -

Donald Trump (All General Trump Conversations Here)Illegal immigration is a problem all over the developed world, not just the US. Australia famously stopped the boats but today's press stories show that there are 105,000 immigrants with asylum requests, and unknown hundreds of thousands more visa overstays. Britain is having to push draconian laws to keep displaced people coming across the Channel and the enormous death toll in the Mediteranean is daily news.

The problem is that all the developed nations have as a matter of course a basic framework of human rights. It is one of the factors that makes them 'developed nations'. So if anyone arrives from a failed state with no human rights and no working economy - think the Central American republics, many African and Middle-Eastern territories - then it's a breach of human rights to return them. You can't, in practice, send someone from a country that holds to human rights, to a country that does not, as it's a breach of human rights. It's analogous to a process of osmosis.

Add to that the inevitable machinery of visa and asylum applications and rights-to-work, with bureaucrats required to establish the identity and bona fides of millions of displaced persons often with no passports or proof of identity. Hence backlogs of many years in the processing queues, meanwhile the subjects are all categorised as unemployable and must be given subsistence rations by the welfare state.

A sorry state of affairs, but one the Republicans are always eager to exploit for whatever partisan advantage can be found by exploiting fear and resentment, their favoured tools of choice. -

Donald Trump (All General Trump Conversations Here)I used to know a girl, a flatmate of a friend, who firmly believed 'the news is all made up'. I wondered what she thought was really going on, if the news is all, as DJT insists, fake, but I didn't want to open that can of worms.

-

The Mind-Created WorldI also think that this self-knowledge is being aware of and being able to manage flaws or patterns in one's thinking and behavior. It seems to be a synonym for a type of self-improvement. This does not necessarily track back to philosophy from what I can see. — Tom Storm

I think it belongs to the therapeutic aspect of philosophy. Did you ever have that 70's perennial The Road Less Travelled? Very much along those lines. (Actually the Wiki entry on 'Know Thyself' is really not too bad https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Know_thyself) -

Joe Biden (+General Biden/Harris Administration)Perhaps. There's some murmurs around that Jim Jordan might win the Speaker's Ballot. God help us all if that's true.

-

Donald Trump (All General Trump Conversations Here)Truly scary. He's succeeded by innoculating millions of people against reality.

— Wayfarer

How so? Were they previously good, decent human beings who could easily tell reality from fantasy? — baker

What I mean is that millions choose to believe Trump's lies over reality. Like Jan 6 was 'an evil plot by leftists' or even 'a beautiful day'. That the 2020 election really was stolen, even if every one of 60 lawsuits brought to make that case were tossed out of court. So you have a significant proportion of the electorate who cannot be convinced of matters of fact, regardless of the evidence. That's what I meant by 'innoculated against reality'. -

The Mind-Created WorldSelf-knowledge is a transcendental paralogism, a logical misstep of pure reason... — Mww

I always thought the maxim 'know thyself' was simply about seeing through your own delusions and false hopes. It doesn't necessarily pre-suppose a 'real self' that needs to be known, except maybe as a figure of speech. Self knowledge as an important aspect of wisdom and maturity.

Burning with the fire of lust, with the fire of hate, with the fire of delusion.

— Fire Sermon — plaque flag

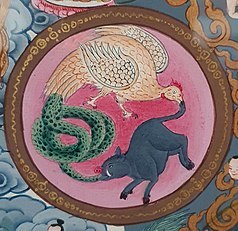

Those are the 'three poisons' of Buddhism, represented iconographically as the pig (greed) snake (hate) and rooster (stupidity/delusion) chasing each other around an endless circle (saṃsāra).

These are said to be the chief motivators of the 'deluded worlding', replaced in the wise by their opposites, namely:

amoha (non-delusion) or paññā (wisdom)

alobha (non-attachment) or dāna (generosity)

adveṣa (non-hatred) or mettā (loving-kindness) -

Joe Biden (+General Biden/Harris Administration)The way it's going I really think they will let the US have a default. — ssu

Actually I believe the next debt limit vote is not required until 2025 - that was part of the agreement between Biden and McCarthy signed off in June (and one of the causes of his overthrow). But the next round of appropriations are due Nov this year - that's the next crisis on the menu.

Wayfarer

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum