-

Are there any good reasons for manned spaceflight?How things are going, it is extremely likely that the last astronaut that walked on the Moon may die of old age since we go back to the Moon, if we go anymore there. Going to Mars is even more questionable. Actually here Neil Armstrong (first on the moon) and Paul Ciernan (last on the moon) are asked that question on the future of manned space flight. Now both are dead and nobody has gone to the moon back. I think the youngest Apollo astronaut that walked on the moon is now 90 years of age. — ssu

That was a good and persuasive post, and I acknowledge the importance of space technology for scientific exploration and for the unintended benefits it has provided.

But I have become sceptical of the 'colonize Mars' narrative. There are plenty of articles out there on the huge physical impediments to doing that, let alone the economic and political barriers. There's also the fact that in the US at least, the ultra-wealthy tech oligarchs (Musk, Bezos, etc) are positioning themselves as the sole providers (and therefore beneficiearies) of the technologies required for these fantastical ideas. This article by Adam Becker, who is a reputable science author and journalist, spells it out particularly well. (His book More Everything Forever, is a powerful takedown of the tech bros visions.)

Mars is too inhospitable to allow a million people to live there anytime remotely soon, if ever. The gravity is too low, the radiation is too high, there’s no air, and the Martian dirt is filled with poison. There’s no plausible way around these problems, and that’s not even all of them. Nor does the idea of Mars as a lifeboat for humanity make sense: even after an extinction event like an asteroid strike, Earth would still be more habitable than Mars. Mammals survived the asteroid strike that killed the dinosaurs, but no mammals could survive unprotected on Mars today.

Putting all of that aside, if Musk somehow did put a colony on Mars, it would be wholly dependent on his company, SpaceX, for supplies. That’s one feature that tech oligarchs’ fantasies have in common: they all involve billionaires holding total control over the rest of us. — Adam Becker

Jezz Bezos, on the other hand, wants 'a trillion people living in a fleet of giant cylindrical space stations with interior areas bigger than Manhattan.' Also fantasy, plainly.

Recall that fantastic Tom Hanks movie about Apollo 13, that almost crash-landed on the Moon after an engine problem, and which required incredibly adroit improvisation and trouble-shooting with what we would now consider very primitive computer technology. That's the kind of pioneering spirit that made NASA great in the day. Whereas Musk and Bezos owe more to Star Wars than to down-home technological smarts.

This idea that we have to 'colonize other planets' to 'escape Earth' is a sci-fi fantasy. We have a perfect starship, one capable of supporting billions of humans for hundreds of milions of years. But it's dangerously over-heated, resource-depleted, and environmentally threatened. That's where all the technology and political savvy ought to be directed - to maintaining Spaceship Earth. -

About TimeGetting the sense for what 'empirical realism' means for Kant is not a wholesale rejection of Descartes. — Paine

I agree. It's not a wholesale rejection, but a correction.

I've also noticed that Edmund Husserl similarly commented on the mistake Descartes makes in respect of 'res cogitans'. He sees the cogito and the turn to first-person evidence as the genuine origin of transcendental philosophy (including his own). His criticism is internal: Descartes discovers transcendental subjectivity but then reinterprets it in the old metaphysical grammar of substances, turning it into something quasi-objective. Then follows all of the confused questions about what 'it' is etc. -

About TimeVery roughly, for me it shows up as (1) less compulsion to define or secure a fixed identity, (2) more tolerance for uncertainty and contingency, and (3) a slightly quieter self-preoccupation in everyday experience. Hard to argue for — more something noticed over time.

-

About TimeKant never refers to the transcendental subject or transcendental ego

— Wayfarer

He does refer to it, albeit in as a source of misunderstanding — Paine

Thanks for those passages, they are right on point.

So he refers to the transcendental subject as something that can't be referred to! Which was the point I was trying to make.

Kant’s point is precisely that the “transcendental subject = x” is not something that can be known, described, or treated as an object at all. It is a formal condition of representation, not a determinate entity. So yes — he refers to it only in order to show why it cannot properly be referred to as an object of knowledge. Questions about its constitution, origin, or ontological status are, for Kant, literally empty of meaning (i.e. 'what is it?' presupposes an 'it'.)

Recall this passage from the related thread about MIchel Bitbol and phenomenology:

Bitbol argues in Is Consciousness Primary? (that) consciousness is not an object among objects, nor a property waiting to be discovered by neuroscience. It is not among the phenomena given to examination by sense–data or empirical observation. If we know what consciousness is, it is because we ourselves are conscious beings, not because it is something we encounter. — Wayfarer

It is precisely the tendency to reify (=make into something) the subject (or observer) that bedevils so much of the discourse about consciousness. First Descartes designates it res cogitans, 'thinking thing'. Then natural philosophy comes along and negates any such idea as self contradictory and incoherent, leading to philosophical materialism (=sole reality of res extensa). But Kant has already diagnosed and ameliorated these mistakes in this analysis.

I think learning to accept and live with the elusive nature of the self/subject/'I' is a fundamental life lesson. -

About TimeGood as starting points and good to avoid dogmatisms but they can't structurally be 'the last world'. They seem to point to some conclusion and just stop before asserting it. In other words, these approaches seem to point beyond themselves naturally. — boundless

I think you meant ‘last word’ (although it’s an interesting slip). But I agree - they’re not ‘the last word’ in the sense of conveying the absolute truth. They’re a starting point, not a conclusion.

Hope all goes well, I too will be taking a few days out. -

Cosmos Created MindClearly, idealism (i.e. 'mind-dependency') is an anthropocentric fallacy and contrary to the Copernican Principle — 180 Proof

But you never demonstrate a grasp of the implications of philosophical idealism. In the various OPs and essays where I present it, idealism is closely linked to what is called in modern philosophy constructivism: the understanding that the brain synthesises sensory input and conceptual structures to generate what we ordinarily take to be a fully external world. That is not anthropocentrism, nor does it imply that the universe depends on human minds in order to exist. It is an acknowledgment of the nature of knowledge, and, more to the point, the reality of being.

I started listening to the video, and the very first sentence already gives the game away: “It seems that reality somehow waits for awareness before deciding what it is.”

“Waiting” is an intentional predicate. It presupposes an agent that entertains a state of anticipation or suspension. But no serious account of observation — in either physics or philosophy — is committed to anything like that. Introducing this language at the outset inserts a straw man into the presentation. The follow-up claim that “physics dismantles this idea” continues the same. Physics does nothing of the kind; 'dismantling is the aim of a presentation about physics, which in turn always requires interpretation. Phrases like “the universe constantly measures itself” are further examples of a metaphor doing illicit conceptual work.

There is also equivocation in the use of the word 'observer'. Sometimes it denotes a physical interaction system (detectors, environments, particles); sometimes it implicitly refers to a conscious subject. Showing that decoherence does not require a conscious observer in the first sense does nothing to address the second sense. The two uses of the term operate at different explanatory levels.

Finally, look closely at the channel itself: joined Nov 2025, a stream of 6-minute videos comprising computer-generated images with AI voiceovers, driven by a creator with a clear agenda. Someone selected the prompts, framed the claims, and published the material. In other words, there is very definitely an observer — namely the author of those materials. Without him (or her), they wouldn’t exist. :-) -

Cosmos Created Minddefinitions specifically tailored to the subject matter. — Gnomon

Discussion is one thing, but re-definition in support of an argument is another. 'Everyone has a right to their own opinions, but not to their own facts' ~ Daniel Patrick Moynihan. -

Michel Bitbol: The Primacy of ConsciousnessMy proposed second installment on Michel Bitbol was rejected by Philosophy Today. No reason given, but maybe because it's too specialised a subject matter, Bitbol's philosophy of quantum physics. But anyone interested can access it here ('friend link', ought not to require registration.)

-

About TimeNote that if, instead, you say that the transcendental subject is a 'pragmatic model' used to 'make sense' of the world without asserting that it is 'real', then you imply a non-dualist view (i.e. the very distinction of 'subject-object' is provisional). In these kinds of view, there is no need to explain how the subject came into existence. It is, after all, an useful 'map' at best. — boundless

Kant never refers to the transcendental subject or transcendental ego. That comes with later philosophers. But also, notice that in singling out the subject as an individual being, you're already treating this as an object of thought. That is what I mean by taking an "outside view".

What seems to be driving the worry you keep returning to is not so much a disagreement about Kant but a discomfort with contingency itself — the idea that the conditions under which a world appears are not grounded in something further, necessary, or metaphysically self-explaining or self-existent.

What you keep coming back to is

-

1. The transcendental subject is a condition of intelligibility.

2. But if it is contingent, it must have an explanation.

3. If it has an explanation, there must be something beyond it.

4. Therefore transcendental idealism is incomplete or unstable.

This is,preciselysomething like 'the Cartesian anxiety'. And perhaps, now, the 'useful map' analogy is a good one. In presenting this OP, I didn't set out to offer a 'theory of everything'. Really the point is to call out the naturalistic tendency to treat the human as just another object — a phenomenon among phenomena — fully explicable in scientific terms. This looses sight of the way that the mind grounds the scientific perspective, and then forgets or denies that it has (which is the 'blind spot of science' in a nutshell).

The point is not to replace scientific realism with something else, but to recall that the very intelligibility of scientific realism already presupposes what it cannot itself objectify: the standpoint of the embodied mind. So I'm not presenting it as 'the answer' but as a kind of open-ness or aporia. -

About TimeI think the main difference between Plato and Kant, is that Kant denies the human intellect direct access to the noumenon as intelligible object. — Metaphysician Undercover

Agree with the contrast you’re drawing: Plato allows a form of direct intellectual apprehension of intelligible reality, whereas Kant denies that human cognition has any such unmediated access apart from sensible intuition structured by space and time.

But I will call out the language of “intelligible objects.” I think this is where a deep metaphysical confusion enters. Expressions like “objects of thought” or “intelligible objects” (pace Augustine) quietly import the grammar of perception into a domain where it no longer belongs. They encourage us to imagine that understanding is a kind of inner seeing of a special type of thing. I'm of the firm view that the expression 'object' in 'intelligible object' is metaphorical. (And then, the denial that there are such 'objects' is the mother of all nominalism. But that is for another thread.)

But to 'grasp a form' is not to encounter an object at all. It is an intellectual act — a way of discerning meaning, structure, or necessity — not the perception of something standing over against a subject. Once we start reifying intelligibility into “things,” we generate exactly the kind of pseudo-problems that Kant was trying to dissolve. -

About TimeI think @Joshs previous comment (above your reply to me) holds, I hope that what I've been arguing so far conforms with it.

the 'transcendental idealist' takes the 'transcendental subject' as being an individual sentient (or rational*) being. — boundless

Here, you are treating the transcendental subject as if it were an entity that could itself be viewed from an external standpoint and compared with a “world without it.” But the whole point of the transcendental analysis is that there is no such standpoint. The subject here is not a being in the world, but the condition under which anything can appear as world. So asking how the world would be “without reference to it,” or how it “comes into existence,” already presupposes what the analysis rules out.

the transcendental idealist wants to deny that "the world without reference to any sentient/rational being" has any intelligibility and is completely unknowable even in principle. — boundless

And what world would that be? Presumably, the earth prior to the evolution of h.sapiens . But then, you're conflating the empirical and transcendental again. Notice that even to name or consider 'the world without any sentient/rational being' already introduces the very perspective that you are at the same time presuming is absent.

I totally get that this is not an easy thing to internalise, because we are so habituated to treating time, space, and objectivity as simply “out there.” Seeing them instead as conditions of intelligibility rather than as objects of description requires a genuine shift in perspective, a kind of gestalt shift. -

About TimeA note to clarify my view of what is meant by the 'in itself': it designates whatever has *not* entered 'the machinery and the manufactury of the brain' (to quote Schopenhauer.) Put another way: an object considered from no perspective.

You might be thinking of an object in the absence of any perspective, but even thinking of it requires either imagining it or naming it, both of which are mental operations.

This is why I have said previously that the ‘unobserved object’ neither exists nor does not exist — not because it is unreal, but because either claim already presupposes a standpoint from which it can be meaningfully predicated. To say 'it exists' is to predicate something of it when it literally 'hasn't entered your mind'. To say 'it doesn't exist' likewise already situates the object as something, the existence of which can be negated. So the 'in itself' is neither - in fact, not even a 'ding'! Just the 'in itself'.

(Again, the noumenon and the ding an sich are different in Kant's philosophy but they are often conflated, even by him.

Noumenon means literally 'object of nous' (Greek term for 'intellect'). In Platonist philosophy, the noumenon is the intelligible form of a particular. Kant rejects the Platonist view, and treats the noumenon primarily as a limiting concept — the idea of an object considered apart from sensible intuition — not as something we can positively know. And it’s worth remembering that Kant’s early inaugural dissertation already engages directly with the Platonic sensible/intelligible distinction.

The 'ding an sich' is not the same concept although as noted often treated as if it were. The ‘thing in itself’ designates whatever a thing may be independently of the conditions under which it appears to us. It is not an intelligible object we could know or describe, but precisely what cannot be brought under any standpoint or predicates at all.)

In relation to time, then: whatever we think exists, or might exist, is already implicitly located in time and space. Even the theoretical abstractions of modern physics (like virtual particles) are temporally, if ephemerally, existent. As Kant points out, in order to conceive of anything as a thing, it must be located in time and space which provide the structural conditions that underlie all empirical existence - the 'framework of empirical cognition', you might say. But because these ‘pure intuitions’ are so deeply embedded in our consciousness, we fail to recognise that the mind itself is their source. We think we are looking at them, when in fact we are looking through them, at the objects disclosed within them. -

About TimeIt's not a contradiction at all.

If there is, it is utterly independent of our perceptions and consciousness — Janus

Note the use of “is” and "it" here — “if there is X,” “if there is something unknown.” In designating it as a something, the grammar is already treating it as a determinate entity, when the whole point of the discussion is precisely that it is not even a thing in that sense. (In fact, this is where I think Kant errs in the expression 'ding an sich', 'thing-in-itself'. I think it would be better left as simply 'the in itself'.)

The phrase “in itself” is not meant to name a hidden object standing behind appearances, but to mark a limit: the point at which our concepts, predicates, and categories no longer legitimately apply. Once we start saying, of the in itself, that “it exists,” “it is independent,” “it has properties,” we have already introduced the very conceptual determinations that the notion of the in-itself was supposed to suspend. Remember this was Kant's argument against dogmatism (although I know you think that Kant was dogmatic.) But it should engender a genuine sense of not knowing.

That is why there is no contradiction in saying, on the one hand, that what reality is in itself lies beyond our conceptual and sensory reach, and on the other hand, that we cannot meaningfully predicate independence, existence, or non-existence of it. The first is a negative or limiting claim about the scope of cognition; the second is a refusal to reify that limit into a metaphysical object, a mysterious 'thing behind the thing.'

To insist that “if there is an in-itself, then it must be utterly independent” is already to assume the very issue under question — namely, that reality must be a kind of thing standing over against a mind, describable in abstraction from the conditions under which anything becomes intelligible at all.

None of this commits me to phenomenalism or to denying a shared world. We plainly inhabit a common world structured by stable regularities, constraints, resistance, error and correction. But those features belong to the world as it is disclosed within experience and inquiry, not to a metaphysical description of what reality supposedly is “in itself” apart from any standpoint whatsoever.

The deeper point is simply this: we are not outside reality looking in. We are participants within it. Treating the in-itself as a hidden object that either exists or does not exist already presupposes a spectator standpoint that the argument is calling into question.

Glad we have some points of agreement here and I appreciate the way you’ve framed this.

I agree entirely that something like a limiting or grounding function is logically indispensable. If we remove the idea that our experience is constrained by something not reducible to our beliefs or constructions, then reason, error, correction, and a shared world really do start to collapse. In that sense, I also agree that simply denying the “in itself” leads to incoherence.

Where I still want to be careful is about sliding from that logical indispensability to an ontological claim that what plays this limiting role therefore exists independently as some kind of determinate something — even if we immediately say it is unknowable or indefinable. My worry is that this quietly reintroduces the very reification the limit-concept was meant to address.

I’m not saying there’s a hidden thing behind the world that we can’t access. I’m saying that the fact we’re always inside reality — participating in it rather than standing outside it — means that our ways of describing it are never final or complete. Reality keeps pushing back on our concepts and forcing revision, but that doesn’t mean there’s a separate metaphysical object called “the in-itself.” The limit shows up in the openness and corrigibility of our own understanding, not as a mysterious thing beyond it.

So I’m not trying to remove the limit, but to interpret it differently: not as a hidden entity or substrate standing apart from us, but as a structural feature of our participation in reality — the fact that conceptual determination never closes upon itself, that experience is always constrained and corrigible without being exhaustively capturable in metaphysical predicates.

On that reading, reason, language, science, and intersubjective objectivity remain entirely intact. What drops out is only the picture of a fully observer-external reality that could, even in principle, be described as it is “in itself” from nowhere in particular. That seems to me a modest but important shift rather than a radical one.

With that, I offer another quote from the irascible but brilliant Arthur Schopenhauer, which I think makes the point that I was trying to press earlier, about how cogniive science validates aspects of philosophical idealism. The second sentence, in particular:

All that is objective, extended, active—that is to say, all that is material—is regarded by materialism as affording so solid a basis for its explanation, that a reduction of everything to this can leave nothing to be desired (especially if in ultimate analysis this reduction should resolve itself into action and reaction i.e. physics). But ...all this is given indirectly and in the highest degree determined, and is therefore merely a relatively present object, for it has passed through the machinery and manufactory of the brain, and has thus come under the forms of space, time and causality, by means of which it is first presented to us as extended in space and active in time. — Schopenhauer

And with that, I've said enough already, I need to log out for a few days to return to a writing project which is languishing for want of concentration. But thanks for those last questions and clarifications, I think the discussion has moved along. :pray: -

InfinityThe kind of thought that was subject of an excellent 2008 BBC documentary, Dangerous Knowledge.

-

About TimeThe quantum realm is so minute that the measuring tools we use to monitor the quantum state affect the state itself. Non-quantum measurement is like rolling a ping pong ball at a bowling ball. We bounce the ping pong ball off, then measure the velocity that the ball comes back to determine how solid the bowling ball is. The ping pong ball is rolled to not affect the movement of the bowling ball. — Philosophim

Not so:

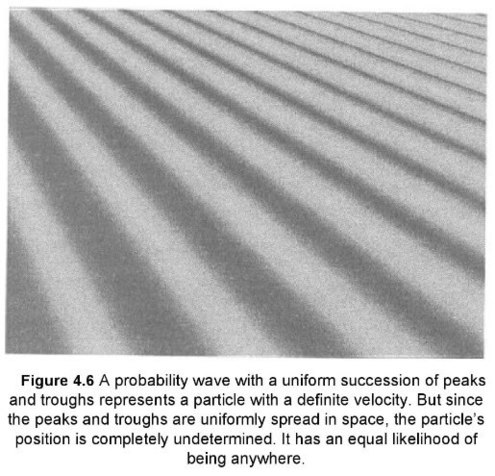

The explanation of uncertainty as arising through the unavoidable disturbance caused by the measurement process has provided physicists with a useful intuitive guide… . However, it can also be misleading. It may give the impression that uncertainty arises only when we lumbering experimenters meddle with things. This is not true. Uncertainty is built into the wave structure of quantum mechanics and exists whether or not we carry out some clumsy measurement. As an example, take a look at a particularly simple probability wave for a particle, the analog of a gently rolling ocean wave, shown in Figure 4.6.

Since the peaks are all uniformly moving to the right, you might guess that this wave describes a particle moving with the velocity of the wave peaks; experiments confirm that supposition. But where is the particle? Since the wave is uniformly spread throughout space, there is no way for us to say that the electron is here or there. When measured, it literally could be found anywhere. So while we know precisely how fast the particle is moving, there is huge uncertainty about its position. And as you see, this conclusion does not depend on our disturbing the particle. We never touched it. Instead, it relies on a basic feature of waves: they can be spread out. — Brian Greene, The Fabric of the Cosmos

There is a need to know the exact location and velocity of every electron circling an atom, and yet we don't have the tooling to get that — Philosophim

I'm sorry, but you're not seeing the real problem. The point of the uncertainty principle is that it's not a matter of 'tooling'. The uncertainty is genuine, as Brian Greene says above - a matter of principle. It is also true that scientific realists including Sir Roger Penrose don't accept this saying that there must be a better theory that hasn't been discovered yet. But I think that is far from a majority opinion. I acknowledge I'm not a physicist, but those references I mentioned (plus the Brian Greene one) do support what I'm saying.

But the issue is, you can't stipulate anything about the 'independent thing' without bringing the mind to bear upon it.

— Wayfarer

Barring one thing: That it is independent. Meaning you are saying it exists apart from your observation. How? Who knows really. That's the definition of true independence. It does not depend in any way on your comprehension of it. You know it can exist in a way based on your tested and confirmed model. But how does it behave apart from that model? At that point, you can glean certain qualitative logic that necessarily must be from the working model. One being, "That is independent". Meaning it exists apart from observation. How exactly? Who knows. Its the "Thing in itself" problem from Kant. And it is a fascinating topic. I like your exploration of it here. My point is that if it is not independent, what does that logically mean? Does that break our current model use, our definition of observer, and everything we comprehend? It would seem to. Maybe it doesn't, and I was curious if you had given it thought and could propose what that would be like. — Philosophim

I agree that this lands us very close to the “thing in itself” problem — but my own way of thinking about it probably leans more towards Buddhism.

What I mean is this: the “in itself” is what lies beyond our conceptual and sensory reach. It is not just unknown in practice; it is unknowable in principle insofar as any determination already brings the mind’s discriminations to bear. Even to say “it exists independently” is already to ascribe an ontological predicate to what is supposed to lie beyond all predication.

From that point of view, saying that the 'in-itself exists' is already a kind of over-specification — but saying that it does not exist is equally a mistake. Both moves bring in conceptual determinations into what is precisely not available to conceptual determination. We 'have something in mind'. That’s the sense in which 'it' is neither existent nor non-existent: not as a mysterious third thing, but because the existence / non-existence distinction itself belongs to the world as it is articulated for us.

So when you say “barring one thing: that it is independent,” I would hold off on that — not because I think the world collapses into subjectivism (ceases to exist outside my particular mind), but because “independence,” taken as an claim about reality in itself, is already a conceptual construction. What we actually encounter is constraint, resistance, regularity, surprise — all within experience and modelling. Independence as such is an abstraction we draw from that, not something we can meaningfully attribute to what lies beyond all possible description.

None of this breaks scientific models or the practical notion of an observer. Science continues exactly as before, operating perfectly well within the conventional domain of determinate objects, measurements, and laws. The point is only that when we try to step outside that domain and make ultimate claims about what reality is “in itself,” our concepts outrun their legitimate scope.

Bottom line: reality itself is not something we're outside of or apart from. We are participants in it, not simply observers on the outside of it. And that points towards an existential stance or way-of-being. -

About TimeThe distinction made between a realm of becoming and the realm of eternity in early Greek thought is an interesting frame to consider.

Change becomes the most difficult thing to talk about. — Paine

Yes — that distinction really does go back to Parmenides, for whom 'the Real' can’t change without becoming unintelligible, which is why becoming is relegated to the realm of appearance. Plato and Aristotle both respond by trying, in different ways, to show how something can remain the same while still genuinely changing. This was the origin of much of Aristotle's metaphysics of universals.

There’s also an interesting modern echo in Andrie Linde’s point that a purely observer-independent picture of the universe tends toward a kind of thermodynamic “deadness,” where time and becoming drop out of the equations in quantum cosmology. Meaningful change only manifests relative to observers in non-equilibrium conditions - 'an observer with a clock, and the rest of the Universe', as he puts it. It feels like a contemporary version of the same old tension between being and becoming (see this interview.)

The independent existent we are measuring, does not overlook the role of the observing mind. — Philosophim

But it does! This is the basis of the major arguments about 'observer dependency' in quantum physics. Here are some excerpts from an influential paper, which has really entered the realm of popular science, John Wheeler's Law without Law, something I've quoted previously. Here is Wheeler's gloss on the measurement problem in quantum physics, and it really shows in a few words, how it had called Einstein's lifelong belief in the 'mind independence of reality' into question:

The dependence of what is observed upon the choice of the experimental arrangement made Einstein unhappy. It conflicts with the view that the universe exists "out there" independent of all acts of observation. In contrast, Bohr stressed that we confront here an inescapable new feature of nature, to be welcomed because of the understanding it gives us. In struggling to make clear to Einstein the central point as he saw it, Bohr found himself forced to introduce the word "phenomenon". In today's words, Bohr's point - and the central point of quantum theory - can be put into a simple sentence: "No elementary phenomenon is a phenomenon until it is a registered (observed) phenomenon".

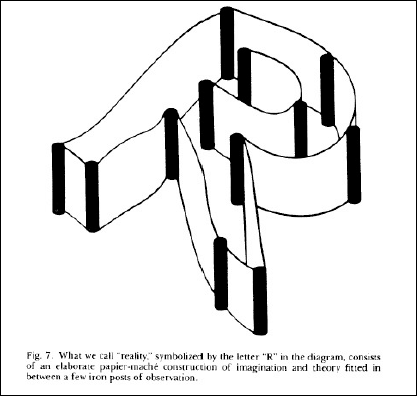

He also created this graphic to illustrate the point:

Caption reads: 'What we consider to be ‘reality’, symbolised by the letter R in the diagram, consists of an elaborate paper maché construction of imagination and theory fitted between a few iron posts of observation."

Notice this - the 'iron posts' are observations and measurements. But the shape of the R itself is a 'paper maché construction of imagination and theory'. That is what I mean by the way 'mind constructs reality'.

All this is elaborated in such books as Manjit Kumar. Quantum: Einstein, Bohr, and the Great Debate About the Nature of Reality. London: Icon Books; New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2008 and David Lindley - Uncertainty: Einstein, Heisenberg, Bohr, and the Struggle for the Soul of Science. New York: Anchor Books/Random House, 2008. They make the centrality of the question of the 'mind-independence of reality' is central to these debates.

You can absolutely logically claim that if observers weren't there, the measurements that they invented in themselves would not exist. But you haven't proven that what is concluded inside of the framework itself, that there is change which independently exists of our measurement, isn't necessary for the framework to work. That is why it is not an assumption that if you remove the measurement, that the independent thing being measured suddenly disappears. — Philosophim

But the issue is, you can't stipulate anything about the 'independent thing' without bringing the mind to bear upon it. We know a lot about the early universe, before h.sapiens evolved, from cosmological science, geology and so on. But all of that is still structured within the framework the mind provides. You might say it was 'there all along' or 'there anyway' - but 'there' and 'anyway' are what the observer brings to the picture. This is what I mean by saying that there being an observer, nothing exists - not that does not exist, but neither does it exist, because there is no 'it'. Yes, when we discover 'it', we learn that it was there all along - but outside that framework, what is 'it'?

We don't notice that we're 'bringing the mind to bear' because that is the way that naturalism frames knowledge. There's the subject/observer, here, and the object/target, there, and never the twain shall meet.

I notice that you haven't actually commented on any of the philosophical arguments presented in the original post. I suggest that this is because you instinctively interpret the question through the frame of scientific realism. This is it intended as a pejorative statement, but as a way of understanding what the debate is about. Scientific realism is based on conviction of the reality of the observed world, and to question it is really a difficult thing to do. -

About TimeSize", "weight", etc., are not "the object", those terms refer to a specific feature, a property of the supposed object, and strictly speaking it is that specific property which is measured, not the object. — Metaphysician Undercover

That’s actually on point. It’s very close to Bergson’s argument about clock time: what gets measured is not concrete duration itself, but an abstracted, spatialized parameter extracted for practical and mathematical purposes. Precision applies to the abstraction — not to the lived or concrete whole. But then, we substitute the abstract measurement for the lived sense of time.

You have to understand that the act of measurement assumes something is there independent of the measurer — Philosophim

I don’t think any of the sources I’m drawing on dispute that there is something to be measured. Of course measurement presupposes an independent reality — otherwise measurement would be meaningless. The point is not that we create what we measure, but that the act of measurement already involves an observer-relative framework of abstraction.

Distance does not disappear if no one measures it — but “distance in meters,” embedded in a metric geometry and operationalized by instruments and conventions, does not exist independently of those frameworks. Likewise with clock time. What exists is change, passage, becoming; what we measure is an abstracted parameter extracted from it.

The philosophical claim is simply that it does not follow from the existence of something independent to be measured that reality itself can be specified in wholly observer-independent terms. That further move is a metaphysical assumption, not something licensed by the practice of measurement itself. It overlooks //or rather takes for granted// the role of the observing mind.

I think there’s a deeper issue lurking here. Absent any perspective whatever, what could it even mean to say that something “exists”? To exist is to be this rather than that — to stand apart, to have determinacy, identity, and distinction. That act of discrimination is not supplied by the world in the abstract; it is enacted by cognitive systems.

Space and time are intrinsic to that discriminative capacity. Without spatial differentiation and temporal ordering, there could be no stable objects, no persistence, no comparison, no calculation — and therefore no measurement at all. Conscious awareness and intelligibility presuppose these structuring forms.

None of this denies that there is something there independently of us. The point is that what counts as an existent — as something identifiable, measurable, and meaningful — already presupposes a standpoint capable of making distinctions. Pure “observer-free existence” is not coherent; it is an abstraction that undercuts the very conditions that make existence intelligible in the first place.

Husserl makes a related point in Philosophy as a Rigorous Science: naturalism quietly assumes “nature” as already given and self-evident, instead of asking how nature becomes constituted as an objective domain in the first place. The intelligibility and measurability of the natural world presuppose structures of cognition that naturalism itself cannot account for without circularity.

That is a cognitive process: the way the mind “brings forth” or constructs the world that naturalism treats as its starting point. This used to be the territory of philosophical idealism, but in an important sense these insights have been increasingly validated by cognitive science. Cognitive science explores how the brain and mind actively structure what we take to be external reality. That does not deny that there is an external reality — but an external reality can only be real for a mind.

This is how mind is properly re-integrated into a universe that naturalism assumes is without one. -

About Time

I don’t want to give the impression that I doubt science’s capacity for extraordinary accuracy in the measurement of time (and distance). Atomic clocks measure time with astonishing precision. The philosophical point, however, is that the act of measurement itself cannot be regarded as truly independent of the observer who performs and interprets the measurement.

So what? might be the response. The point is that this quietly undermines the assumption that what is real independently of any observer can serve as the criterion for what truly exists. That move smuggles in a standpoint that no observer can actually occupy. It’s a subtle point — but also a modest one. It doesn't over-reach.

Where it does appear to be controversial is insofar as it calls into question the instinctive sense that the universe simply exists “just so,” wholly independent of — and prior to — any possible apprehension of it. But again, that is a philosophical observation, not an argument against science. It is an argument against drawing philosophical conclusions from naturalistic premises. -

About TimeIsn't the measurement (of time) objective? — Corvus

It is. If you read the OP as saying it isn’t, then you’re not reading it right. -

About TimeHey, thanks! Most appreciated. There’s nothing I really differ with there. Again, I’m not saying that ‘nothing exists’ sans observers. What this, and most of my arguments, are against, is the elimination of the observer - the pretence that through the perspective of science, we see the world as it truly is. And the almost invariable implication, we’re a ‘mere blip’ in the vastness of cosmic space and time. That is viewing ourselves “from the outside”, so to speak - treating the observer as another phenomenon. When in reality the observer is that to whom or to which phenomena appear. That, I take to be the lesson of phenomenology and its forbears.

Again, I’ve also been most impressed with a book I’ve mentioned before Mind and the Cosmic Order, Charles Pinter (Routledge 2021.) Pinter was a maths professor emeritus whose last book (and swansong) was about the intersection of philosophy and cognitive science. It was not much noticed in the philosophy profession as he had been a maths professor - which is a shame, because it’s a genuinely insightful book. His big idea is the way cognition (not only human cognition) organises experience by way of meaningful gestalts.

I’m also influenced by Aristotle - not by having studied him at length, because I wasn’t educated in ‘the Classics’. But I’ve absorbed it by cultural osmosis, so to speak, and also through my pursuit of comparative religion and philosophy. In the time I’ve been posting to forums, since around 2010, I’ve developed respect for Aristotelian Thomism, although without necessarily buying into the devotional commitments. But I’m very much in the overall mold of Platonism, again I think through cultural osmosis.

We know there is activity independent from the observer, and any activity requires the passage of time. — Metaphysician Undercover

“The observer knows there is activity independent from the observer”. He does indeed. -

Michel Bitbol: The Primacy of ConsciousnessThanks. I'm interested in this fragment from a review of the following book. (I acquired a copy, but it's very technical and specialised):

Husserl called his position "transcendental" phenomenology, and Tieszen makes sense of this by claiming that it can be seen as an extension of Kant's transcendental idealism. The act of cognition constitutes its content as objective. Once we recognize the distinctive givenness of essences in our experience, we can extend Kant's realism about empirical objects grounded in sensible intuition to a broader realism that encompasses objects grounded in categorial intuition, including mathematical objects.

The view is very much like what Kant has to say about empirical objects and empirical realism, except that now it is also applied to mathematical experience. On the object side of his analysis Husserl can still claim to be a kind of realist about mathematical objects, for mathematical objects are not our own ideas (p. 57f.).

This view, Tieszen points out, can preserve all the advantages of Platonism with none of its pitfalls. We can maintain that mathematical objects are mind-independent, self-subsistent and in every sense real, and we can also explain how we are cognitively related to them: they are invariants in our experience, given fulfillments of mathematical intentions. The evidence that justifies our mathematical knowledge is of the same kind as the evidence available for empirical knowledge claims: we are given these objects. And, since they are given, not subjectively constructed, fictionalism, conventionalism, and similar compromise views turn out to be unnecessarily permissive. The only twist we add to a Platonic realism is that ideal objects are transcendentally constituted.

We can evidently say, for example, that mathematical objects are mind-independent and unchanging, but now we always add that they are constituted in consciousness in this manner, or that they are constituted by consciousness as having this sense … . They are constituted in consciousness, nonarbitrarily, in such a way that it is unnecessary to their existence that there be expressions for them or that there ever be awareness of them. (p. 13). — Richard Tieszen, Phenomenology, Logic, and the Philosophy of Mathematics (Review)

My belief is that numbers, forms, and so on, are structures in consciousness, in a somewhat Kantian sense. Put very simply, if you ask me what 2 and 2 are, I am obligated to answer '4' - which doesn't say there is any such 'thing' as a number in some purported 'platonic space'. Counting is an act, and numbers represent those acts. So as acts, forms, ideas, etc are intrinsically dynamic, but also invariant.

(I haven't read Deleuze yet, although watched a very interesting video lecture on his 'registers', which, um, registered for me.) -

About TimeI did note that you claimed you weren't denying science, and it seemed to me that you weren't denying change. My point as been that this means you also cannot deny succession and duration, at least with how I've understood your argument so far. — Philosophim

But I respectfully suggest that you haven't. You will invariably view it through the frame of scientific realism, and the only kind of arguments you would consider, would be scientific arguments. Let's leave it at that, and thanks for your comments. -

Michel Bitbol: The Primacy of ConsciousnessFor Husserl and the other thinkers I mentioned there are no thing-in-themselves. Not just because humans or animals must be present for them to be perceived, but because a world seen in itself, apart from humans or animals, is a temporal flux of qualitative change with respect to itself. — Joshs

I had the idea that his ‘eidetic vision’ was concerned with essences ‘the pure perception of the essential, invariant structures (eidos) of phenomena, moving beyond mere empirical facts to grasp universal essences, achieved through the method of eidetic reduction, where one uses eidetic variation (imaginatively altering features of an object to find what must remain constant) to discover necessary laws of consciousness’. However it’s centered on conscious structures not on some supposed ‘third realm’. He referred to it as a kind of qualified Platonism. -

About TimeUltimately, the passage of time ought to be considered as an immaterial activity, which all material activities may be compared with (measured by). However, this presents us with the problem of determining exactly what this immaterial activity is, so that we might figure out a way to measure it. We actually already have a good idea about what it is, it is a wave activity, the vibration of the cosmos. — Metaphysician Undercover

Nothing like that is required. What appears mysterious is not some hidden feature of the world, but the fact that the conditions which make the world intelligible are not themselves part of what appears, but are provided by the observer. That is exactly what “transcendental” means: essential to experience, but not visible within it. -

About TimeTime is the fact of change. When you say time doesn't exist prior to consciousness, you state change didn't happen prior to consciousness. Thus, I understand why you say time starts with consciousness, as change would start with consciousness. The primacy of consciousness. But there is no evidence that change doesn't happen prior to consciousness by your points presented. — Philosophim

Change — understood as physical variation or state transition — can perfectly well occur without observers. I explicitly acknowledge that in the original post:

I am entirely confident that the broad outlines of cosmological, geological, and biological evolution developed by current science are correct, even if many of the details remain open to revision. — Wayfarer

If you think that is being denied, then you’re not engaging the point of the argument.

What I am questioning is whether physical change, by itself, amounts to time in the absence of an observer. Time provides the framework within which facts are ordered and rendered intelligible as a sequence — as earlier, later, before, after, duration. As soon as one considers those facts, that temporal ordering is already being brought to bear by a standpoint capable of making sense of them. That is what the observer brings to the picture. But the observer is never a part of the picture.

The period prior to the evolution of h.sapiens can indeed be estimated and stated, but that estimation is performed by an observer using conceptual units of time that are meaningful to human cognition.

It’s therefore important to see that this is not an empirical argument about what we observe, and hence not a question of empirical evidence as such. A useful parallel is the long-standing problem of interpretations of quantum mechanics: all interpretations start from the same empirical evidence, yet they diverge radically in what that evidence is taken to mean. The disagreement is not evidential, but conceptual. None of your objections really come to terms with this if you continue to see it as an empirical argument. -

About TimeI think you need to resolve the fact that measuring something doesn't mean we've created the thing that we've invented a measurement for. — Philosophim

What 'thing' is being discussed? TIme is not 'a thing'. For you and I to agree on a unit of time, we must use a common measure of time within the same frame of reference.

My claim is that time as succession or duration does not exist independently of the awareness of it. What can exist without observers are physical processes and relations between states. But “before,” “after,” “passage,” and “duration” are not properties of those processes taken in themselves — they arise only where change is apprehended as a unified flow by a subject. Without that, there is change, but not time in the meaningful sense.

It’s also worth noting that contemporary physics itself no longer treats space and time as fully observer-independent in the classical sense. As Ethan Siegel discusses in Does Our Physical Reality Exist in an Objective Manner?, relativity shows that simultaneity and duration are frame-dependent, and quantum mechanics ties physical outcomes to measurement contexts. Even there, what physics supplies are invariant relations between observations — not a single absolute temporal structure “in itself.” My point is not to deny physical reality, but to note that the naive realist picture of time as an observer-free container is no longer supported — even by physics. -

Ideological Crisis on the American RightThe White House official web page has today launched a page that blames the Democrats for the Jan 6 2021 outrage. Nothing further need be said about it - except, perhaps, that Trump's ascendancy has utterly annihilated any claim to proper political legitimacy on the US Right.

-

Michel Bitbol: The Primacy of ConsciousnessFor him (Husserl) a beyond of experience is not impossible but meaningless. — Joshs

But I'm a bit uncomfortable with the suggestion that this is a state of kind of dumb indolence. I was responding to @Tom Storm question about 'God, Brahman, The One'. In that context, I said that phenomenology was not overtly concerned with the question of the 'ultimate nature or ground'.

But here I have to acknowledge the way that Buddhism has influenced my attitude. Specifically the book Zen Mind Beginner's Mind. This is a Sōtō Zen text which stresses the 'ordinary mind' practice. Ordinary mind teachings suggest that enlightenment is not a distant, supernatural state to be achieved in a future life, but is found in the natural, unconditioned state of one’s own mind during everyday activities. But at the same time, this "ordinary" mind is not the habitual, reactive mind filled with habitual tendencies, judgment and grasping, but rather a state of "no-doing" or wu wei.

It is here that the parallel with epochē can be seen. As you probably know, there is scholarship on the parallels between epochē in Greek scepticism and Buddhist philosophy, originating in the encounter of Pyrrho of Elis with Buddhist traditions in Gandhāra. In both contexts, dogmatic views (dṛṣṭi) were seen as a source of disturbance or suffering. But this did not amount to scepticism in the modern, argumentative sense. The suspension involved was not a matter of withholding belief pending proof, but a practical discipline aimed at loosening attachment to reified ways of seeing, in order to transform one’s mode of experience. It was inextricably connected with meditative awareness, which in the Buddhist context, is the actual seeing of how 'dependent origination' conditions consciousness.

So the point is, behind all of this, there is considerable philosophical sophistication which can easily be misunderstood. Sōtō, in particular, is built around the writings of Master Dogen and his work the Shobogenzo, which is a classic of Buddhist philosophy and practice. Since the Kyoto School, there's been quite a bit of comparative literature on Heidegger and Dogen. -

About TimeYou start at X second and end at Y second to get a minute. It is a discrete measurement that is broken down into smaller discrete measurements in order. When we measure a minute, we have to watch for 60 seconds. — Philosophim

Of course, no contest. But the point is, the observer is watching, measuring, deciding on the units of measurement. The relationship between moments in time and points in space is made in awareness.

To clarify, time as an observable measurement only exists as a form of representation and can only be understood by a conscious subject. That doesn't mean that what is being represented does not exist independent of our ability to measure it. — Philosophim

I'm saying that in the case of time, that this is just what it means. We're not talking about rocks, trees and stars - but time itself. And the argument is that time has an inextricably subjective ground, that were there no subject, there would indeed be no time. Now obviously that's a big claim, but I've provided the bones of an argument for it in the OP. It can also be supported with inferential evidence from science itself.

What is the source of intelligibility of the empirical world? — boundless

Intelligibility is not something the world produces, but something that arises in the relation between a world and a mind capable of making sense of it. For a contemporary cognitive-science way of expressing this without metaphysical commitments, John Vervaeke’s notion of “relevance realisation” points in a similar direction: intelligibility emerges as an ongoing activity of sense-making enacted by cognitive agents in their engagement with the world.

I had never heard of Nagarjuna — T Clark

A major figure in Mahāyāna (East Asian and Tibetan) Buddhism. I am hesitant to bring Nāgārjuna into the debate, as the scholarship sorrounding his interpretation is difficult. This lecture might be a useful intro, from the Let's Talk Religion channel that I watch from time to time. -

Donald Trump (All Trump Conversations Here)I didn’t intend what I said as any kind of endorsement of Trump’s actions.

-

About TimeThe scientific method is attempting to represent reality in a measurable and objectively repeatable way. Science in its fine print never claims it understands truth. It claims it has been unable to falsify a falsifiable hypothesis up until now. — Philosophim

Right - agree. But here we're discussing a philosophical distinction. This understanding of 'the mind's role in the pursuit of scientific understanding' is not itself a scientific matter, right? It's the kind of discussion you will find in philosophy of science, or in the writings of philosophers I gave in the original post. And I do think that philosophers are concerned with disclosing truth, in a broader and less specialised sense than science. Philosophical analyses do not necessarily comprise 'falsifiable hypotheses' in the sense that Popper meant it. They are intended to provide insight and self knowledge. -

About TimeIf we accept what Schopenhauer and Lao Tzu were saying, doesn't the inconsistency you've identified disappear? — T Clark

Yes. Few do.

The fact that we can say “one second has passed” already presupposes a standpoint from which distinct states are apprehended as belonging to a single, continuous temporal order.

— Wayfarer

I don't see that as a pre-supposition, but an observed reality. — Philosophim

It's a measured reality - and that is a world of difference. 'One second' is a unit of time. As are hours, minutes, days, months and years. But (to put it crudely) does time pass for the clock itself? I say not. Each 'tick' of a clock, each movement of the second hand, is a discrete event. It is the mind that synthesises these discrete events into periods and units of time. That's the point you're missing. -

About Timeit seems to me that this position gives no explanation of their existence and their coming into being. — boundless

But as said, I have no reason to contest evolutionary theory or geological history. I’m not providing an alternative account of the evolutionary origins of our species. I suppose you could say that what is being questioned is the support that evolutionary theory provides for philosophical naturalism. Naturalism says, after all, that the mind is of a piece with all the other elements and attributes of humans and other species, and can be treated within the same explanatory matrix. That is what is being called into question here. Which is why I'm not contesting the empirical accounts.

If I measure 1 second forward, then one second later I have recorded and measured one second backwards. Again, follow the velocity of an object over time on a graph. If I set up a crash stunt, I have to measure the forces and time. Once the stunt is complete, I can see if the number of seconds that passed, did. To arrive at the point after the stunt is complete, time would have had to pass in the measure that noted, or else the current measure of time would be off. 1 minute past is what happened to be at the current time correct? Time is simply measured the change of one thing in relation to another thing. But to say time doesn't exist prior to consciousness is to claim there was no change prior to consciousness. An observer can observe and measure change, but an observer is not required for change to happen. — Philosophim

I don’t deny that physical change occurs independently of observers, nor that we can model and measure those changes using clocks, graphs, and equations. But this doesn’t yet give us temporal succession in the sense that’s at issue here.

Physics relates states to one another using a time parameter. What it does not supply by itself is the continuity that makes those states intelligible as a passage from earlier to later. A clock records discrete states; it does not experience their succession as a continuous series amounting duration. The fact that we can say “one second has passed” already presupposes a standpoint from which distinct states are apprehended as belonging to a single, continuous temporal order.

So the claim is not that change requires an observer, but that time as succession—as a unified before-and-after—does. Without such a standpoint, we still have physical processes, but not time understood as passage or duration.

What I am suggesting is that, in your examples, the role of the observer in supplying continuity and relational unity between discrete events goes unnoticed. This is not a personal oversight, but a consequence of how scientific abstraction works. Science deliberately brackets the experiencing subject in order to focus on those measurable attributes of change that can be recorded with precision by instruments. Once this abstraction has been made, the subject — as the individual scientist — can indeed be set aside, creating the impression that objects and interactions are being described as they are in themselves. But this methodological exclusion does not eliminate the subject’s role in making those measurements intelligible as a temporal succession in the first place.

(Something that is made explicit in quantum physics in the form of the “observer problem”. In Mind and Matter (1958), Erwin Schrödinger, drawing explicitly on Schopenhauer, argues that there is an important difference between measurement and observation. A measuring instrument, he notes, merely registers a value; the registration itself contains no meaning. Meaning arises only when the result is taken up by a conscious observer. In this sense, physical description presupposes, rather than replaces, the role of the observer in making the world intelligible. Schrödinger was well aware that such claims would invite charges of mysticism, but his underlying point is methodological rather than theological: physical theory, however powerful, cannot eliminate the standpoint from which its results acquire significance.) -

Donald Trump (All Trump Conversations Here)I was aware of that, but again, if Trump actually seized Greenland by military force, it would be a far bigger deal than extracting Maduro from Venezuela. (Which, according to reports, is now undergoing a massive crackdown by the military and intelligence communities. )

-

Michel Bitbol: The Primacy of ConsciousnessTo get rid of the remnants of physicalism, we need to stop talking about the mind, body and world in terms of objects which interact , even objects that exist only very briefly. — Joshs

I can't help be reminded of Buddhist abhidharma in this description. From Merleau Ponty and Buddhism, Gereon Kopf, Jin Y. Park:

This is why Buddhism is mentioned so frequently in connection with enactivism and embodied cognition. (Although the convergences shouldn't be overstated - the book also says that Buddhism is soteriological in a way that phenomenology is not. But again this is where Michel Bitbol is particularly insightful, he's been a participant in the MindLife Conference which explores parallels between science, philosophy and Buddhism.)

But what is the transcendent ground of being; God, Brahman, the One, or all of the above? And how could we ever know that such a foundation exists? It is one thing to adopt a phenomenological perspective and seemingly dissolve the mind–body distinction; it is quite another to posit a principle that underlies everything. What if there is no ultimate ground? — Tom Storm

Phenomenology was not originally concerned with spiritual or theological matters as such. Its primary task was methodological: clarifying the structures of experience and the grounds of meaning, objectivity, and being. That said, there are certainly existentialist thinkers—Søren Kierkegaard, Gabriel Marcel, Emmanuel Levinas—who engage seriously with questions of transcendence. But they do so in a way that is fully aware of the postmodern situation: the loss of metaphysical guarantees and the rejection of intellectual abstraction as a genuine mode of existence.

In these thinkers, transcendence is not treated as an 'ultimate ground' or cosmic substrate, but as an irreducible implication of lived experience.

It’s also worth recalling the original meaning of the phenomenological epochē, as articulated by Husserl: the suspension of judgement with respect to what is not evident (which it has in common with ancient scepticism.) This suspension does not amount to a denial of the transcendent, nor does it imply that there is no ultimate ground. Rather, it refuses to speculate.

In that sense, phenomenology neither asserts nor rules out a “beyond”; it simply declines to turn what exceeds experience into a theoretical object. There’s something quite Buddhist about this also: a refusal to indulge metaphysical speculation, paired with an insistence on attending carefully to the nature of existence/experience moment-by-moment. -

Donald Trump (All Trump Conversations Here)All that said, Maduro was responsible for a huge amount of suffering and economic degradation. Venezuelans have been reduced to living in poverty while he and his cronies squirrelled away the wealth of the nation in their private accounts. His wife owns entire neighborhoods in Caracas according to reports.

The other thing is, the extraction and incarceration of Maduro hardly provides a template for Trump’s other stated aims of ‘taking Greenland’ or ‘overthrowing the Colombian government’. Those are very different in size and scope. The extraction was very specific with a clear outcome and a limited theatre of operations. Occupations and regime changes are far more expansive and open-ended. One hopes that Trump’s musings on those ideas are just braggadocio. -

Can the supernatural and religious elements of Buddhism be extricated?Assuming that they were right and that 'Nirvana without remaineder' de facto coincides with oblivion, there is no 'transcendent' goal there. — boundless

There is a Mahāyāna sutra that explicitly rejects that idea. It would be a form of nihilism.

Wayfarer

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum