-

"All statements are false" is NOT false!?!Besides which, there are loads of reasons to think this claim is simply false. You'd have to have a language without the logical constants.

Even if you changed it to "All atomic sentences of L are false", then the question is: under what interpretation? Systematic falsehood under one interpretation is systematic truth under another. -

"All statements are false" is NOT false!?!

Read this again. I did it that way specifically to leave room for the conclusion that the claim must not be a statement (i.e., not truth-apt), and that would be the result for the Liar. (You could think of that as concluding "If there's a set of all truth-apt strings, the Liar isn't in it.")

There was no reason to conclude either version of the claim is not truth-apt; both versions must be false. -

Semiotics Killed the Cat

I'll throw in Paul Grice too as someone with a theory of meaning that connects "natural meaning"-- what Eco calls "symptoms" in your quote, clouds meaning rain, that sort of thing-- and "non-natural meaning", that is, what we do when me mean something by a sound we make, etc., etc. -

The Ontological Proof (TOP)The argument is invalid anyway since (1) quantifies over the space of entities existentially. So (1) is equivalent to: there is a being Y such that Y = X and Y has property P, and a sub statement (there is a being Y such that Y=X) is exactly what the argument seeks to demonstrate, so it is circular. — fdrake

Yes, this is exactly right. I've had this argument twice with another forum member. To predicate (truly or falsely) of an object does not show that the object is within your domain of discourse, but presupposes that it is.

There is a sort of epistemic variant that is worthwhile:

1. Something is perturbing the orbits of these asteroids.

2. If there were a planet of a certain mass there, it would do that.

3. ?

Well, you don't get to conclude anything. (2) gives you an abductive hypothesis to investigate, but you still need to investigate. -

Change of thread titleI'm not disputing what fishfry meant, I'm criticising the way in which he expressed himself, which lead to a misunderstanding. — Sapientia

I'll agree @fishfry was a bit up on his hind legs. I didn't find it rude, but you did, and there's nothing more to say about that. (Might be a Merkin thing.)

You do have my sincere appreciation for the work you do to keep this place running. -

Change of thread titleThat's not what I said. — Sapientia

Really? What other way is there to read this:

If we're talking about grammar, then that's an instruction. — Sapientia

Whether an utterance is an instruction depends on the context and the purpose of the utterance, its intended or expected understanding by its intended or expected audience, and so on. So it's a question for pragmatics, not grammar. -

Change of thread title

-

If two different truths exist that call for opposite actions, can both still be true?Can two sides with conflicting views of truth both be right? If so, does the concept of truth remain? Can one side’s truth can be considered a greater truth that subordinates a lesser truth? Or, is the essence of a truth that it is a truth, and as such cannot be made less of a truth by another truth? — Mark Marsellli

There is the old story of the blind men and the elephant: two parties who disagree are sometimes both right because they are describing different parts of something, and both wrong in thinking the part they're describing is the whole, or that the whole must be like that part. Both speak the truth but neither speaks the whole truth, and that is the source of conflict.

If there is a greater truth, it would be one that encompasses these smaller, partial truths. Imagine two people trying to invent the idea of trading: each is hesitant because she reasons, quite correctly, "If I give you this thing, then I won't have it." But there is a greater truth they need to find, that if they both give the other something, then they have made a trade. (And it is whether that trade is fair that must be judged.)

In your case, it's entirely possible that both sides are right, but neither seems to be putting forth a greater truth that encompasses what the other is saying. Unfortunately, if that greater truth is "the effect on the US economy," no one will be able to tell you what that is.

And that's one reason there might be such a rule as not considering downstream effects in anti-dumping cases, because it would be impossible ever to decide to do what you've already determined, for other, overriding reasons of policy, must sometimes be done.

Of course each side is making the case for a decision that would benefit them, and putting forth a partial truth. Sometimes people want to test a claim by generalizing it. In this case, would the wire rod consumers be happy to give up the protection they would deny the wire rod manufacturers? Not on your life. But that does not mean what they are saying is false. It's a mistake to think your part of the elephant is the whole elephant, but it's also a mistake to say your part isn't what you say it is unless it's the whole elephant. -

Change of thread titleLike, if the sportscaster said it afterwards, but is speaking as though he's reliving the moment, thus the lack of past tense — Sapientia

There you go. It's more immediate and by using the indicative instead of the subjunctive, it sounds more like a statement of fact, more certain.

In general terms, I think you can't read off the use being made of a sentence, in a given context, from its surface grammar, anymore than you can read off a sentence's logical form from its surface grammar. That use would be something like the mood of the utterance. (For instance, Kevin Spacey can instruct you to go to lunch by repeatedly asking, "Will you go to lunch?") -

Change of thread titleDo Americans really mix up present and past tense like that? Do they really use "doesn't" when they mean "hadn't"? That's crazy. — Sapientia

Think of it as a past tense counterfactual expressed in the historical present. No one is mixing up their tenses. It's colorful. It's also a way of avoiding the subjunctive mood, and expresses greater certainty. -

Quantitative Skepticism and Mixtures

What you're talking about here is the underdetermination of theory by data, yes?

Every dataset is a duck-rabbit.

Goodman shows the same effect can be found in induction-- that there are always pathological predicates that can fit your observations just as well as the usual "entrenched" predicates (or kinds).

I think, in a general way, @T Clark is on the right track by asking which theory you can act on. If you want to build a rocket, would you use or one of the pathological alternatives?

That's sort of a "hot take" -- am I taking about what you're talking about? -

How to determine if a property is objective or subjective?Mr Tasmaner — Samuel Lacrampe

Mr. Tasmaner was my father. I'm just Srap.

(The things you can say on the internet ...) -

Change of thread titleImperatives are also a natural choice for perfecting conditionals: if you're negotiating, and you say, "Throw in another hundred and you've got a deal," it suggests I can make the deal if and only if I throw in another hundred (which could be false, but it's what you want me to think).

-

Change of thread titleAnd since I can't control what the staff does — fishfry

I think the grammar is exactly as you and @Sapientia interpret it; it's the bit of context given here that makes the difference. No Americanism. "Charge me or release me!" "Either let me do my job or fire me!" would be other examples of giving instructions to people you're not empowered to give instructions to.

Permissives can do weird stuff with expressing preferences too. "You can change my post if you want, but I'll never post here again." Again, I'm not even in a position to give permission, and this is actually a threat. "What should we watch?" "You can put on whatever you like." That one cedes my portion of the decision-making power to you, perhaps implying I don't have a preference-- but it could also be interpreted as taking all the power before handing it all to you, or implying that my preference would trump yours if I had one. -

Differences that make no differenceThat highlights that the only times these types of rules really matter are when decisions which have consequences have to be made. They don't really have anything to do with truth, they have to do with what to do next. — T Clark

This is really nice.

Generalize it and reword the second sentence, and you've reinvented pragmatism!

When I asked about statements about the future, I was thinking about an ambiguity in the word "attainable". For instance, it could be that everything we could possibly know is consistent with rolling a 1 and with rolling a 6. But that doesn't mean I can't find out which one I roll by just going ahead and rolling the die. -

Gettier's Case II Is BewitchmentI think that there is something to be gleaned out of the fact that B consists of more than one statement. What counts as being a proposition is starkly different than what counts as being a belief statement. — creativesoul

Yeah, that's an option.

Conjunctions would be easy, I guess-- just two beliefs instead of three. And you could work up an approach that doesn't treat disjunctions, conditionals, counterfactuals as being potential truth-bearers at all. (Just inference rules or habits.) What about negatives?!

It's worth playing around with. -

How to determine if a property is objective or subjective?kids will think, for example, that the tree over there is objectively real — javra

I was thinking about this driving home from work last night. The standard example for perception is always something like this: I see the road sign, that is a road sign, etc., an observation at a single point in time. But in English at least we have present participles: I am continuing to see the road sign as I drive along the road. (I think a similar point has been made in "embodied" theories of knowledge and perception-- that the persistence or invariance of the object as we move about and investigate is what we should capture. Optical illusions, for instance, often depend on observer position, light source, etc.)

So that would be an example of the object not changing state but the observer. If it's still there when you come back and it's just the same-- no, but if you come back and bring someone else with you, and the two of you walk around, look at it from different angles, maybe do so at different times of day and so on, then we start to think "objective". -

Gettier's Case II Is BewitchmentCan we make anything out of the difference between, on the one hand, A being a reason for believing B, and, on the other, A merely ("merely"?) being consistent with B?

-

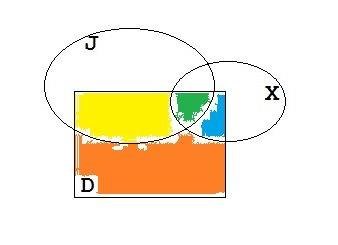

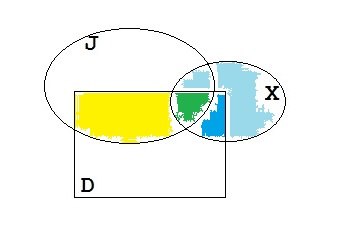

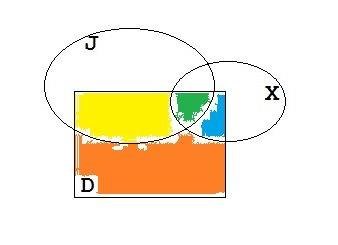

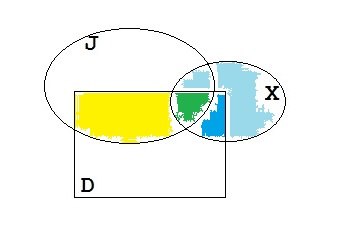

Gettier's Case II Is BewitchmentP(~J∨X∣D)≥P(J∣D). — unenlightened

Not sure why you think this.

Here's a diagram for what I said, which was :

That seems pretty straightforward: we start with the yellow and green bits and pick up the blue as well. The blue might be empty, but we still know yellow+green+blue ≥ yellow+green.

Now here's yours, which was :

Your claim is that orange+blue+green≥yellow+green. Maybe, maybe not. Depends on whether orange+blue≥yellow, doesn't it? And our hypothesis was that yellow+green is pretty big: Smith has strong evidence for his belief.

Two more points. Another interpretation of Smith's belief would be:

which looks like this:

That adds in the light blue bit. I don't think there's any reason to do this though, because all of Smith's reasoning is relative to , his reasons for believing Jones owns a Ford. Adding the light blue bit doesn't change the argument anyway. It's just a bigger version of the "≥" we've already got.

Now what about ? Are the reasons Smith has for believing Jones owns a Ford reasons to believe Brown is in Barcelona? Well, they're not reasons to believe he isn't: there's no reason to think that Jones having always owned a car and always a Ford and now driving a Ford, etc., precludes Brown from being in Barcelona. So there's no reason to think and are disjoint. But it doesn't give you much to go on, so when I assigned a prior to , I made it tiny, and that seems reasonable to me.

((Apologies for the crumminess of the diagrams.)) -

This Debunks Cartesian DualismWould you say they know what a wrench is? — Banno

Is there a difference between these two questions:

- Do you know what this is?

- Do you know what this is called?

(The latter refers to some language, not necessarily the language in which the question is asked, but maybe specifying it matters more than I think.) -

Gettier's Case II Is BewitchmentIf p is true then p ∨ q is true.

If there is strong evidence that p is true, then p is true.

Therefore, if there is strong evidence that p is true then there is strong evidence that p ∨ q is true. — unenlightened

Besides which, shouldn't your conclusion be "If there is strong evidence that p, then p v q"? -

Gettier's Case II Is BewitchmentIf p is true then p ∨ q is true.

If there is strong evidence that p is true, then p is true.

Therefore, if there is strong evidence that p is true then there is strong evidence that p ∨ q is true. — unenlightened

We don't have to do it this way.

I didn't bother with conditional probabilities before, but it's the natural way to model Smith's belief.

If is Jones owning a Ford, and is the evidence Smith is relying on, then the belief he holds highly probable is not really just but , the probability of given . And it's dead easy to show that for any

. -

"All statements are false" is NOT false!?!

One says, if x is a statement, then it is false. There is a longish tradition of so interpreting universal statements (Russell and Ramsey both for slightly different reasons), and thus denying them existential import.

The other version says, everything is a statement and everything is false. Is that what you want to claim? -

Differences that make no differenceFor some proposition (statement, claim, postulate), p, if attainable evidence is consistent with both p and ¬p, then further knowledge thereof is unattainable. It’s like a difference that makes no difference — not information. — jorndoe

Does this class encompass all statements about the future? -

Differences that make no difference

Is it irrelevant that the duck-rabbit has been heavily "abstracted"? That is, many, many details of ducks and rabbits are left out, aren't they? And we know the method: only those features are retained that can be made ambiguous as features of either a duck or a rabbit. The remaining features are even distorted a bit off true to push them more toward an "average" feature. (That we accept this distortion is really interesting.)

So I would think what's learned is something about abstraction. -

Order from Chaos

Suppose you're a curious youngster with internet access and you look up "Evolution" on the Wikipedia. Here are the first two paragraphs you'll read:

Evolution is change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations.[1][2] Evolutionary processes give rise to biodiversity at every level of biological organisation, including the levels of species, individual organisms, and molecules.[3]

Repeated formation of new species (speciation), change within species (anagenesis), and loss of species (extinction) throughout the evolutionary history of life on Earth are demonstrated by shared sets of morphological and biochemical traits, including shared DNA sequences.[4] These shared traits are more similar among species that share a more recent common ancestor, and can be used to reconstruct a biological "tree of life" based on evolutionary relationships (phylogenetics), using both existing species and fossils. The fossil record includes a progression from early biogenic graphite,[5] to microbial mat fossils,[6][7][8] to fossilised multicellular organisms. Existing patterns of biodiversity have been shaped both by speciation and by extinction.[9

We've got "shaped" there, looks a little intentional, so you check to see if either speciation or extinction are the sorts of things that have intentions. Nope.

So if you start from scratch, and just learn from Wikipedia, you should be fine. -

The Conflict Between Science and Philosophy With Regards to TimeUnless the speed of light has been measured in every possible type of circumstance, then there really is no reason to believe in SR. — Metaphysician Undercover

"No reason"? -

Order from Chaos

That Shakespeare could type is pure speculation, since he predated the typewriter by, I think, several years. How do you answer that, evolutionist scum?

(And, BTW, excellent point.) -

Order from ChaosLife however, in its 3 billion odd years that we know of its existence, has not passed out of its order. It makes adjustments for the purpose of maintaining its order. It seems to try to survive and keep the melody of life ringing. Not only this, but it seems to build on this melody, turning it into a mathematical symphony. — MikeL

I think the puzzles you keep running into, Mike, come from an image of the lone organism, a person, struggling heroically against their environment. Now you've even taken to treating Life as if it were a single entity doing stuff like adapting and surviving. It's not. There's not a single rock falling down the well but trillions. Evolution is a statistical phenomenon. It's all about populations. What evolution makes clear is how relative invariance arises, or relative "lock in" of change (usually advantageous in one way or another related to survival or reproduction). -

Evidence of Consciousness Surviving the Body

Sorry-- Individuals is the book. I just wasn't bothering to check. I have now, and Chapter 2 is the no-space thing and Chapter 3 has the three-bodies thing.

This is ever so barely on-topic because PFS argues that our concept of consciousness is entirely embodied, and a specific "my body", much as you have suggested here. -

Evidence of Consciousness Surviving the BodyDisembodied consciousness would mean experiences absent a body. So what is that like? — Marchesk

Chapter 2? maybe of Strawson's Individuals, the no-space thought experiment. Book also includes the I-have-three-bodies thought experiment, which I wish someone would make into a flash game.

Srap Tasmaner

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum