-

Devil Species Rejoinder to Aristotelian Ethics

Yes, but whatever we use "to speak of the territory" (including "essences") is not the territory itself.

A map is something used to know territories themselves, no? It is "that through which we know," not "what we know," (or at least not "all that we know.) It would be strange for a chemist to say: "I know a lot about words, language games, diagrams, theories, and models," and then to leave it at that.

The idea of "essence" might be explained quite differently from how Aristotle goes about it, but the idea that there are different kinds of plant and animal and that they each thrive in manner that is, in part, determined by "what they are," seems pretty unobjectionable. Even on a view that "species aren't real," something very much like species must still exist; the evidence for it is everywhere. -

10k Philosophy challengeI haven't finished yet, but I made it a good deal through and have a question:

In general, I think defining ethics in terms of freedom can work, since free beings—unconstrained by ignorance or circumstance—will chose what is good, what causes them to flourish, etc.

However, it seems to require a certain view of freedom for this to work. Whereas if freedom is primarily defined in terms of potency—"the ability to choose anything"— then we seem to be open to all the critiques of post-Enlightenment morality as defined in terms of "rational agents" (e.g. Nietzsche, MacIntyre, etc.)

So my question is, why does the "rational agent," care about other's freedom? I didn't catch this.

And then some other thoughts that may or may not be useful:

So, freedom consequentialism’s measure of value is the ability of persons to understand and make their own choices, specifically those choices regarding what to do with their mind, body, and property. It is generally best to think of this kind of freedom as to be protected rather than promoted. So long as a person is able to understand and make their own choices, they have their freedom...

It is only the freedom over things that already belong to a person that matters, so getting more stuff over which a person can have freedom is not morally valuable. Things are bad, on this measure of value, when they prevent a person from being able to understand and make their own choices.

Is the assumption that any adult is "free?" I am just not sure how this works with experience. It seems that "weakness of will," or incontinence are ubiquitous human experiences, as is acting against our goals out of ignorance.

I personally like a slightly modified definition of free acts based on Lynn Rudder Baker's definition. I would say an act is free when:

We want to do x and we actually do x.

We want to want to do x. (i.e., Frankfurt's second order volitions)

We do x because we want to do it (it is not a coincidence, our wanting is causally involved in the process)

We would still want to do x even if we understood the full provenance of why we want to will x (i.e., there is not some fact we might discover that would make us no longer want to do x)

These conditions, particularly the last, are difficult to meet entirely. This is no issue, an act can be more or less free, people more or less self-determining; freedom is not bivalent. But then it seems to me that freedom is exactly the sort of thing that needs to be "promoted," through education, self-discipline, etc.

There is a sense in which the virtues can be trained (Aristotle), and this seems to allow for greater self-determination. There is also a sense in which techne, knowing "how to do things," is essential to being free to do things. One isn't free to "tutor kids in calculus," if one doesn't know calculus for instance, and a society isn't free to traverse continents in a day if it has not discovered jet engines and the principles of lift. But techne in particular tends to be something that must be fostered, promoted, and taught, and it also often requires various "things" to be put into practice.

It also seems to me then that property is going to be very relevant to freedom. Hell, that's a big reason why people covet money, they think it will "make them free." A retired person who loses all their savings might no longer be "free to stay retired," for instance. Leisure must give way to work; they are coerced into an action they do not want to engage in by the loss of their property (and this could obviously work in reverse with gaining property). -

Do (A implies B) and (A implies notB) contradict each other?

That much I can agree with under a formalist/nominalist view of mathematics. If we take that mathematical objects are platonic objects, where, by definition, the two would be timelessly equivalent, does the Scandal of Deduction make mathematical platonism troublesome?

I don't think so. However numbers exist, they don't seem exist in the way physical systems do, so this is not strictly an issue.

It is however relevant for how the assumptions of platonism affect how we think of physics. Folks like Gisin have argued, somewhat convincingly I think, that assumptions about math have been key to how physicists think of physics. In particular, these assumptions are used to support claims about eternalism or "the block universe" (as opposed to local becoming, the growing block universe, etc.). His argument is that intuitionist assumptions make a better grounding for physics.

I also think these issues could be used as an argument against platonism, something to the effect of: "the way number is actually instantiated differs radically from the assumptions of platonism." However the two aren't necessarily in conflict.

If you think the above is an exemplification of the rebuttal, do you think it is a valid argument? The only way I see is by denying β which is denying the laws of chemistry, which is back to the problem of induction (how do you know every DNA degenerates?)

I don't think it gets around the problem of the premises having to include the conclusion. The conclusion still always follows with p=1 and must in a way be "contained" in what one starts with.

That quote also seems to assume some potentially problematic things about what constitutes a "natural law," but that's sort of aside the point.

Is this about all computation then and what I wrote above irrelevant?

It perhaps depends on how much you embrace pancomputationalism in physics and information theoretic explanations of the other special sciences. If we think number only appears in nature in terms of computation and process then that seems suggestive at the very least. But I don't think process metaphysics ultimately rules out more platonesque views like Hegel's doctrine of concept and essence, or the Patristics differentiation between logoi and Logos. -

Pragmatism Without Goodness

This questioning fully ignores that which I repeatedly have asked of you. This doesn't at this point come as a surprise. But, since you've asked as an open question, in non-metaphorical and what I take to be far more up to date terminology: by strictly consisting of literally pure, limitless, and absolute understanding (with strong emphasis on all three terms).

Understanding does not logically require intentioning - this, for example, in the way intentioning requires intent(s) - and yet is a rather pivotal aspect of what is termed "thought" in all cases.

Go back and read how Plotinus describes freedom across 6.8, which he explicitly ascribes to the One (as I have shown.) Or go read the quotes by two respected scholars I have shared that also explain this.

Like I have said, Plotinus is dealing with something very similar to your argument here and rejecting it. When the Good/One is determined by goodness it is not being determined by something outside of itself or by a mere part of itself (denoting a lack of simplicity). Nor is it striving after something not yet attained (denoting temporality).You are assuming a sort of univocity between act vis-á-vis infinite subsistent being and finite beings, which Plotinus explicitly rejects. This is why analogical talk, affirmations and negations, are required. And this seems to me to be the source of confusion.

Understanding does not logically require intentioning - this, for example, in the way intentioning requires intent(s) - and yet is a rather pivotal aspect of what is termed "thought" in all cases.

Intentionality, not "intentioning." I feel like sticking to the well defined term will (hopefully) help with the slide towards univocity. Understanding requires thought to have content, a content described in terms of "nothing through excellence," or "nothing through infinity," not "nothing in virtue of privation." The One does not emanate the way one domino knocks over another nor in the way a toddler wets himself.

I've by now come to believe that we will staunchly disagree on this point of Neoplatonism not being a form of Creationism. To which I cannot help but shrug and move on.

I've asserted no such thing, nor have I been engaged in "Christian apologetics," as you seemed to suggest earlier. I have simply pointed out that you have a very confused idea about Neoplatonism if you think the One is mindless principle, devoid of intellection and freedom, since Plotinus explicitly rejects this, and Proclus, Porphry, etc. follow this point. Likewise, this predates Plotinus in the influences he alludes to, e.g. Aristotle's Metaphysics Book XII:

The First Principle upon which depend the sensible universe and the world of nature.And its life is like the best which we temporarily enjoy. It must be in that state always (which for us is impossible), since its actuality is also pleasure.54(And for this reason waking, sensation and thinking are most pleasant, and hopes and memories are pleasant because of them.) Now thinking in itself is concerned with that which is in itself best, and thinking in the highest sense with that which is in the highest sense best...

The created/uncreated distinction is a common way to discuss that which exists by virtue of its essence—what exists necessarily—and that which does not. This is the difference between subsistent being, which depends on nothing else and "is what it is in virtue of nothing else," and non-subsistent being.

Creationism," is a modern term. In a one sense, the One is "responsible for," "the source of," or even "creates" the world. Likewise, there is a sense in which the One "has being" or "the One is." A strict negation of these terms is clearly not what Plotinus' means, else he would be talking about a fiction, pointing out the impossibility of what he is talking about.

Nonetheless, he denies that the One "creates" and denies it being. This is because the One is nihil per excellentiam (“nothingness on account of excellence”) or nihil per infinitatem (“nothingness on account of infinity”). This as opposed to nothing through privation” (nihil per privationem). Hence the need for "unknowing," and apophatic praxis to approach it. There is, however, not a lack of what finite entities possess in the One, but rather an analogical superabundance.

At any rate, "creationism" would be a strange term to apply to much the early Christian Neoplatonistic tradition as well, since many of the Patristics hew close to a view consistent with emanation, which is indeed something later thinkers need to try to iron out because there are conflicts here (although not in the way you describe).

Your earlier posts seem to suppose a sort of Biblical literalism, which in turn leads to positing a univocity of being, God as just a very powerful entity sitting over and against the world. But these ideas are almost always explicitly denied in those thinkers who are called Jewish/Christian/Islamic Neoplatonists, because it would indeed lead to serious incongruites if not outright contradictions. -

Do (A implies B) and (A implies notB) contradict each other?

Thinking of the two as timelessly equivalent leads to the Scandal of Deduction. P(I) should allow us to know O in "no time at all," on the view that they are the same exact thing. In reality, no computation occurs in "no time at all."

Consider a second program Q that simply takes the output of P as its input and prints it to tell a user what the shortest path is.

Well, if we have Q(P(I)) it is clear that Q cannot print until P is finished computing. But if the output of Q is equivalent with Q, this is a strange thing indeed.

A helpful way to think about this is by looking at the way physical computation always involves communication and the ways in which it can be explained/moddled in terms of communication theories: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1023/B:MIND.0000005133.87521.5c

Likewise, 2+2=4 can't be the same thing as 2+2 is 4 in terms of computation for other reasons. There are an infinite number of programs with 4 as their output (given some input). But (6+2)/4 is not the same computation as 2+2. If programs just are their outputs then all sorts of completely different programs, some very quick to execute, other intractable, all end up being the same thing. But then why are some intractable, taking millions of years, and some take a millisecond if they are identical? Clearly they aren't identical in every way.

Hence why I said, "in some sense it might make sense to think of 2+2 is 4." However, this assumption seems flawed when one discussed computation in general and physical computation in particular.

But the "Scandal of Deduction," is about why we find the results of deduction and computation surprising and informative. We are physical beings. We do not compute in "no time at all." -

Devil Species Rejoinder to Aristotelian Ethics

This is a mischaracterization of evil as privation. No one reputable denies that a person can aim at being unjust, cruel, etc. It happens all the time. Now, with what you are noting is:

Sure, people act devilish. This is different from a species whose telos specifically non-being. Like I said, a species whose end is specifically to thwart human good is perhaps coherent taken alone, although it makes no sense in the natural order of our world. A species whose end is evil tout court doesn't make sense though.

I outlined is doing bad things for the sake of their own well-being.

I don't think this makes sense. How does a species survive if its end is sickness over health? It cannot be fully oriented towards evil. It can be oriented towards goods that conflict with man's.

And for any sort of rational schemer, prudence still seems like a virtue. They won't get far doing evil if they act stupidly. Likewise courage will still be preferable to rashness or cowardice. You can't do your evil if you get yourself caught or are too scared to engage in evil acts. Etc.

My point is that, the “devil species” would be right to commit unjust acts for the sake of their own well-being, since there is nothing about their nature that relates them to doing just acts, and this would be entailed by Aristotle’s view—wouldn’t it?

A tiger is right to attack and eat people. I don't think the idea of a rational creature oriented wholly towards evil works the same way. Tigers' good is indeed fairly opposed to man as one of man's few natural predators. The good of the Bubonic Plague bacteria might be another example.

With respect to point B, Aristotle kind of confusingly defines ‘good’ in a two fold manner: what is done for its own sake (i.e., intrinsic valuebleness), and what is excellence for a particular thing. I couldn’t really decipher which definition he holds, and they are not compatible with each other. When you say it can’t exist in nature, what you are referring to, I would guess, is your example of a being geared towards unhealthiness (decadence); which is besides my point (as I already noted).

Have you read the Metaphysics yet? That's mainly the reason why I don't think this sort of thing is going to make sense from Aristotle's perspective (IIRC Book XII has most of the relevant stuff). -

Do (A implies B) and (A implies notB) contradict each other?

But probably only because it is NP-complete.

I'm not sure it is. Consider zip bombs, which were a way to overwhelm PCs and make them crash or ton overwhelm anti-virus software. The zip bomb is just a highly compressible file, something like a a text block of nothing but a the same few letters repeated a tremendous number of times. This is extremely compressible because it can be summarized as something like "print XYZ 10¹⁰⁰ times."

What makes the Hamiltonian Path problem intractable is precisely the extremely large number of operations and this can be true for any program provided it has enough steps.

E.g.:

One example of a zip bomb is the file 42.zip, which is a zip file consisting of 42 kilobytes of compressed data, containing five layers of nested zip files in sets of 16, each bottom-layer archive containing a 4.3-gigabyte (4294967295 bytes; 4 GiB − 1 B) file for a total of 4.5 petabytes (4503599626321920 bytes; 4 PiB − 1 MiB) of uncompressed data.

Excel used to be terrible at this sort of thing in terms of using up a ton of resources to try to visually represent (relatively) small amounts of data.

The other interesting question is how to account for forms of non-temporal knowledge

Not sure what you have in mind here. Non-temporal knowledge makes me think of God's self knowledge in Plotinus or something like that. -

Mathematical truth is not orderly but highly chaotic

If there are any practicing or retired mathematicians reading these threads I wish you would speak up. I would ask my old colleagues what they think of these philosophical discussions, but they are pretty much all gone to greener pastures.

I have a friend who is a math PhD. I have never really had a chance to discuss this sort of thing in depth, but I have asked him before if he though mathematics was something created or discovered. He said "created" but not with any great deal of confidence and waffled on that a bit. -

Mathematical truth is not orderly but highly chaotic

"What is math?" is a question situated in a larger metaphysical arena. If we say "it is just symbolic manipulation," we are then led to ask: "what are symbols? And: "why do we manipulate them?"

The "why" here leads right to physics, and the natural sciences more broadly, because a big part of the "why" seems to involve how our symbolic systems have an extremely useful correspondence to how the "physical world" is.

Explanations that just posit mathematics as "a social practice," "an activity," etc. are really non-explanations IMHO. No one denies that mathematics is a product of human culture engaged in by humans. But the question "why do we do this?" leads right to questions about "how the world is" which tend to include physics and metaphysics.

To the extent that we use mathematics to understand the world, our understanding of mathematics also seems to underpin our very notions of "what our lives and our world are."

My question would instead be: "why physics over metaphysics, semiotics, information theory, computer science, or biology?"

These all seem equally relevant. To my mind it has to do with a certain sort of view of naturalism and physics' role in the sciences, one that, if not "reductive," at least tends towards the ideas fostered by reductionism. -

Do (A implies B) and (A implies notB) contradict each other?The Scandal also has some implications for philosophy of mathematics.

Some might have it that 2+2 is just another name for 4. 2+2 is 4.

And in some sense it might be right to think of it this way, but not in terms of computation. Why?

Consider a program P that solves Hamiltonian path problems like the "traveling salesman," through brute force. Then consider an input I for that program with an absolutely massive number of nodes. Then consider O as the output of the program, which figures out the shortest path between all the nodes.

In a certain sense, we might be inclined to say that P(I) = O in the same way we would like to say 2+2 just is 4. However, if I includes enough nodes then all of the world's super computers running P(I) until the heat death of the universe still won't have been able to actually compute O yet.

So then, in a very important functional sense P(I) is not "the same thing as O." If we let abstraction get taken for reality we end up with some weird "problems."

This shows up with non-constructive descriptions as well. "The first number that violates the Goldbach Conjecture," is a rigid designator (if such a thing exists). However, there is loads it doesn't tell us, like what digit the number would start with. Discovering this would seemingly require some sort of Herculean computational effort (given a simple search, and given it exists) even though we have a rigid designator description of what we are looking for.

Well, what to make of this? Perhaps mathematics is better thought of in terms of signs and relations instead of identity. This will all be explained in my forthcoming magisterial book introducing Hegelian-Semiotic-Process-Thomism, also to be known as "The Correct Philosophy." :cool: -

Do (A implies B) and (A implies notB) contradict each other?

This sounds like the "Scandal of Deduction," and it actually holds not just for syllogisms but for all deterministic computation and deduction. From an information theoretic perspective, because the results/outputs of computation and deduction always occur with a probability equal to 100% it follows that they are not informative. Everything contained in the conclusion must be contained in the premise; we learn nothing from deduction. The premises must always assume the conclusion.

For some reason, philosophy has generally taken Hume's Problem of Induction more seriously than this problem, but they are equally intractable from a formal perspective. The entire early modern move to prefer deduction and "analyticity," and it's continuation in analytic philosophy, essentially just ignores that deduction is as undermined as induction.

I wrote an introduction on this a while back for 1,000 Word Philosophy, but they weren't interested in the topic.

https://medium.com/@tkbrown413/introducing-the-scandal-of-deduction-7ea893757f09

I do believe I have a solution here that goes beyond psychologism and grounds an answer for why deduction is indeed informative in physics and biology: https://medium.com/@tkbrown413/does-this-post-contain-any-information-3374612c1feb

The problem shows up because logicians, who tend to be the folks most interested in this problem, only look for formal solutions. But the issue is that "eternal implication," or "implication occuring outside time" is assumed. We can think of computation abstractly, but it remains defined by step-wise actions. Yet these abstractions are taken to be "real" as opposed to merely tools.

However, in the brain or in digital computers two things hold:

1. Computation always occurs over time.

2. Computation involves communication and can be thought of in terms of communication models (some very good work on this has been done and the two end up being almost the same thing, "information processing" indeed.)

Hence, deduction is informative because it involves communication. A message cannot be received before it is sent.

Floridi and others have tried very complex formal explanations and I think these just miss the point. What could be more "surface level" information than what color font a word is written in? We recognize color automatically, seemingly in "no time at all." The color "eternally" implies the word.

Except there is the Stroop Test. If you spell out the names of colors and put the font in a different color, people have a hard time reading off the color of the font. They take much longer. Their error rate goes from virtually always 0 to something fairly high if they are trying to do it quickly.

Why? Because deduction/computation, be it in computers or humans, always involves communication and must occur over some region of space-time, not "all at once and all in one place." Aristotle gets at this in his essentially processual conception of demonstration in the Posterior Analytics.

Again, the criticism I had of Wittgenstein for assuming implication is the "real deal," and causality is "superstition" applies here. -

What is a justification?Strong justification: We should adopt a "pay as you throw," fee system for our city's garbage collection services. This gives people an incentive to produce less garbage. Since available landfill capacity near the city is running out, it is imperative that we try to minimize garbage production since prices will spike dramatically when the current landfill reaches capacity. All empirical data suggests that "pay as you throw," reduces waste and we can still give discounts to low income households to avoid any regressive taxation.

Weak justification: Brenda down at DPW doesn't like the idea of having to print out bills of all different amounts. It's easier to do a flat rate because you can just stuff the envelopes and take the afternoon off.

Terrible justification: The Mayor says that because Mercury is in transit he feels that we should immediately halt all rubbish collection and tell people to burn their trash as an offering to Apollo.

Obviously, the type of justification required depends on the area of discourse. -

Devil Species Rejoinder to Aristotelian Ethics

I think this is right idea. Most "vices" only make sense in the context of their being a corresponding virtue associated with them. If prudence is simply not a virtue, then rashness isn't a vice, it just is how you act. E.g., it's not vice for a beetle or a snake to operate purely off instinct and impulse.

Whereas for any rational creature, prudence will always be a benefit. -

Pragmatism Without Goodness

I don't find anything objectionable in that quote. It's the same straightforward reading of Plotinus I have been pointing to in other scholars. The One is not a being, it is above being (super being). This does not mean "it is not" in terms of simple negation, that is to say "it is false." It does not act in the way that beings act. 6.8 among other places is also clear that this is not a simple negation though. For one, if it was a simple negation, i.e., "the One does absolutely nothing," then the One could not be responsible for any of the other hypostases.

To my main point:

While Plotinus suggests that the One subsists by thinking itself as itself

It's thought is not contentless and it can't "just be," without thought (see the quote from Perl). It doesn't act because in it, act and being (knowing and being) are not separate. Again, we have a lot of affirmation and negation here. This should not be taken as a straight forward negation of all act, a dead or mechanical God. God for Plotinus, as much as for Aristotle, must be pure actuality.

Hence:

Where-since we must use such words- the essential act is identical with the being- and this identity must obtain in The Good... Thus "acting according to its nature" does not apply; the Act, the Life, so to speak, cannot be held to issue from the Being; the Being accompanies the Act in an eternal association: from the two [Being and Act] it forms itself into The Good, self-springing and upbringing."

"Where-since we must use such words," because we are not talking about act in the creaturely sense here since we are talking about the Good.

Still, in assuming this is a forum of philosophy rather than a forum of Christian faith and various apologetics for it:

It's a forum on philosophy which is why I am correcting you on a misunderstanding of a famous philosopher. That's all. The section on divine freedom pretty much considers your exact argument, both:

1. The idea that the One cannot possess freedom (defined in terms of intellection) because intentionality entails being driven by something external to one's self or else being driven by 'one's nature' where 'nature' entails being a composite entity (violating divine simplicity).

2. The idea that the One cannot possess freedom or thought because this would require that it exist in time in order to will anything at all.

Plotinus explicitly rejects both of these, but you seemed to be laboring under the assumption that he accepts them. I am just trying to clear up this misunderstanding for you.

"intentional activity (or else acts) that is fully devoid of any intent"

The One wills itself, it isn't devoid of intentionality. How do you have thought devoid of all intentionality?

Part of the problem here is that you seem to assume that "intentionally requires acting towards some external telos," as a premise. This is exactly what Plotinus rejects at 6.8.8.

Intentionality is something like: "the quality of mental states (e.g., thoughts, beliefs, desires, hopes) that consists in their being directed toward some object or state of affairs." Thought without intentionality isn't thought, but the thought of the One is fullness, a pleroma, not empty.

The problem here is perhaps partly the analogia. You seem to be insisting on what holds for finite creatures for the One, particularly temporality.

This was not considered a problem for Christian Neoplatonists because God's contemplation of God includes everything that follows from God, and indeed created being "lives and moves and [has] its being," only in God (Book of Acts). What was a problem was divine freedom in terms of contingency. So Saint Anselm is still dealing with the issue of: "is the God of revelation just a contingent mask worn by the 'God of the philosopher?'" -

Do (A implies B) and (A implies notB) contradict each other?

Seems right, you can prove MT with contraposition and MP.

But you can do a disjunctive syllogism too.

And the disjunctive syllogism

1. a → (b ∧ ~b)

2. ~(b ∧ ~b)

3.~a V (b ∧ ~b) - material implication (1)

4. ~a - disjunctive syllogism (2,3)

Then again, this probably also amounts to the same thing. -

Do (A implies B) and (A implies notB) contradict each other?

That's not contraposed, I do see now that I didn't contrapose them in the post despite referencing it.

It's ~c → ~a.

This is of course assuming ~c because c would be affirming a contradiction.

And the disjunctive syllogism

1. a → (b ∧ ~b)

2. ~(b ∧ ~b)

3.~a V (b ∧ ~b) - material implication (1)

4. ~a - disjunctive syllogism (2,3) -

Do (A implies B) and (A implies notB) contradict each other?

I didn't contrapose them when I copied and pasted it, I inverted it.

1. a → (b ∧ ~b)

2. If b is true (b ∧ ~b) is false. If b is false (b ∧ ~b) is false, so (b ∧ ~b) is false.

3.~(b ∧ ~b) → ~a - contraposition (1)

4. ~a - modus ponens (2,3)

~(b ∧ ~b) is given in 2

~(b ∧ ~b) → ~a -

Do (A implies B) and (A implies notB) contradict each other?

¬c does not entail ¬a

If a → c it does. Contraposition, flip em and switch em (reverse the order and negate both).

Brad always wears his hat (a) on Mondays (c).

If Brad is not wearing his hat (~c) it cannot be Monday (~a). -

Do (A implies B) and (A implies notB) contradict each other?

But couldn't we just assume B here and get ~A just the same? "If B then ~A," seems to work fine here because the conjunct is still going to come up false.

And then we can do the same thing assuming ~B. That covers all our options assuming LEM.

I guess I'm not seeing the trouble here. I can see the trouble with proofs by contradiction in mathematics that prove things for which no constructive proof exists. That makes sense because, on some philosophies of mathematics, an entity doesn't exist until the constructive proof does (and perhaps it can't exist). -

Do (A implies B) and (A implies notB) contradict each other?1. a → (b ∧ ~b)

2. If b is true (b ∧ ~b) is false. If b is false (b ∧ ~b) is false, so (b ∧ ~b) is false.

3.~a → ~(b ∧ ~b) - contraposition (1)

4. ~a - modus ponens (2,3)

No modus tollens required. You can do it as a disjunctive syllogism too. For the second premise you can assume the b is true or false. Doesn't matter because the conjunction will come out false.

But what I am more interested in would be a system that takes:

a→b

a→~b

a→ (b • ~b)

As premises with their own truth value, judging whether or not the implication is actually valid (i.e. that the two are even related). I suppose this is what relevance logic is for. It would make tables very long, but it doesn't seem that complicated. -

Devil Species Rejoinder to Aristotelian Ethics

you are not denying that "if a devil species existed and 'good' is defined as ~'excellence at one's nature', then a devil species would be 'good' IFF it is unjust, cruel, etc."; instead, you seem to be saying that God wouldn't allow the devil species to exist. This doesn't contend with the hypothetical, unless I am missing something.

I'm saying that a being oriented towards evil is a contradiction in terms. Evil is a privation. How can a being be oriented fundamentally towards non-being? It would have to be "most what it is" when it is not.

On the evolutionary view, we might also consider how a species could ever evolve that prefers sickness to health? Strife and crisis to homeostasis? Destruction as an end in itself?

The closest Aristotle gets to your question is the contrast between vice and being bestial in the Ethics (Book VII IIRC). The bestial man is pretty much a psychopath, what you seem to have in mind. But the bestial man, unlike the man in vice, is incapable of rationality, or is at least a partially rational man beset by beastial urges that deprive him of his rational nature.

We might imagine rational creatures who are more solitary or quarrelsome than man (although man himself is pretty damn quarrelsome lol). But we can't have a creature fully oriented towards non-being as an end, since this would imply it most is when it is not.

Sadism might be another example you have in mind, but the sadist is attracted to causing suffering and destruction because of a sense of power or pleasure(a good), not for its own sake. Even if we suppose a species that acts like many spiders, where females attempt to eat the males that mate with them, it will be the case that this is done for a good (extra calories). Lack of concern for other's good is not being directed towards evil. Beings cannot be oriented towards absence, although they can face competing goods.

I am not sure if a creature whose end is specifically the thwarting of human ends is precluded. But such a thing: a. doesn't exist, b. wouldn't come to exist in the whole order of things. -

Devil Species Rejoinder to Aristotelian Ethics

:up:

It's worth noting that Aristotle explicitly rejects Anaximander's theory of natural selection in De Anima, but I don't think that leaves his philosophy rudderless in the face of modern evolutionary theory. A different species would have a different form of life, different needs, etc. However, they would be the same as respects their rational nature (on Aristotle's account of rationality). -

How do you interpret nominalism?

I don't see how Chesterton's comment commits him to realism vis-á-vis universals. It seems completely consistent with many forms of nominalism as well, e.g. most forms of trope nominalism I am aware of. The point is simply that each particular can't be wholly sui generis or else there is no way to group them and no way to point to any sort of grouping.

You took this statement out of its context within an argument. Language has nothing to do with universals because its purpose is communication, not metaphysical truth. Communication is flawed and based upon prediction by others, it cannot be 100% precise and so cannot refer to a universal, just as one is unable to describe colour to the blind. There are limitations to language.

I didn't mean to. I am also not really sure how this is supposed to show that language cannot refer to universals. Why must language be 100% precise in order for it to refer to universals? Why is being "based on prediction by others" a barrier to speaking of "redness" as a universal, but presumably not the "redness we experience vis-á-vis all red things?"

There are certainly limitations to language, but I don't see how the precludes talk of universals. Why does this lack of precision not preclude talk of other sorts of things like states of affairs, facts, properties, etc.?

Either way, you seem to be using language to say something about universals. Is the idea that we can only say what they are not, a sort of via negativa? But then this would seem to beg the question on realism since universals are called in precisely to explain phenomena, not vice versa.

Again, this is semantics. When I am referencing truth, I am describing the non-static and arbitrary nature of signs and definitions. If I define X as Y, it doesn't mean it is the "true" definition, in fact there is no such thing. Language is entirely relational, you can swap out anything and it doesn't become "false" for doing so. Hence, any term such as "chair" will never be able to have a single agreed upon definition. Everyone will have a different conception of how X is defined.

I would disagree with the idea that language is arbitrary. It isn't. We don't have the words we do for "no reason at all." There is a reason every culture has words for color and size, rather than say, breaking the color spectrum in half and having some words for 'blue and green + size' and other words for 'orange, red, and violet + texture.' Terms like "grue" and "bleen" which denote color and age together don't exist in any language. This is for a good reason - sense perception does not immediately give us any good indication for "how old something is," and the question of "when something was created" is itself fraught.

Likewise, words follow a power law distribution across languages where the most commonly used words are always short and longer, multi-syllable words are always much rarer. It's easy to see why this is the case; it would be a barrier to rapid communication to replace words like "I," "the," "at," "you," "up." etc. with seven syllable words. There are other commonalities in sign systems.

All humans point and the object pointed to is determined with a line going out from the hand or finger in the direction of the object. As Wittgenstein points out, this could conceivably be otherwise (i.e. it is not logically impossible). Pointing could refer to whatever is behind the shoulder of the pointing hand. It's obvious why no one does this. Our eyes are on the front of our head and thus we would not be able to see what we were pointing at if pointing worked like this.

Human signs systems are grounded in what Wittgenstein terms a "form of life," and while this includes elements that are relatively malleable it also includes elements grounded in human biology, our world's physics, etc. As such, the sign systems won't be arbitrary.

Someone is able to refer to the concept of a chair knowing this, that they are referring to a broadly understood but vague notion, which can nevertheless illicit the idea they wish to impose on other minds.

I'm not sure how this is a problem for realism. Plato, the foundational realist, allows that people often only understand forms in a relative fashion. The universal is called in to explain why people can agree at all, not to put forth the thesis that agreement must always occur; it clearly doesn't.

This is entirely semantic. The simplist answer is that it doesnt matter to my argument or the broader question of nominalism.

It doesn't? It seems relevant to the claim that signs are arbitrary and that "anyone can make a word and an arbitrary definition for it." It seems to me that anyone can stipulate a definition, preform an utterance stating "x is defined as y," but this doesn't seem to be enough to make it a word in a language. Languages are emergent social phenomenon; they don't come down to one person. -

Devil Species Rejoinder to Aristotelian Ethics

Very true. Man is the rational animal though and presumably "demon men" would be rational as well, so it's hard to see how they could have entirely different in terms of what springs from rationality and how this orients the person. -

An Argument for Christianity from Prayer-Induced Experiences

The Catholic Church also declared giving the Blood to the laity—utriquism—anathema and launched a crusade over it in Bohemia. And yet now Catholics take the blood at Mass every week. Which is orthodox?

Alright. Don't Mormons too believe they will become godlike themselves — leaving aside the whole planet thing?

I believe so, but I am not super familiar with Mormonism. In some ways this seems more like a return to traditional orthodoxy than the flight from tradition that some Protestants make it out to be. Theosis is a Catholic and Orthodox doctrine and is front and center in parts of the Catholic catechism. Certainly the Orthodox put a greater focus on deification, but it is core Catholic doctrine too. -

Devil Species Rejoinder to Aristotelian EthicsConsider what Aristotle says in Book X of the Ethics about how contemplation is highest form of life in that it is most divine.

Then consider his conception of form → intelligibility → divinity. All things, in tending toward their own actualization, their own fulfilment, are tending toward divinity, realizing form in their own greater and lesser ways. The form in anything is “divine and good and desirable” (Phys.Α.9, 192a17). The form which is the reality of anything is its limited, imperfect share of what the Unmoved Mover is purely and perfectly, that is, idea.

Form or primary substance at its highest-level actuality simply is God. And the desire which God inspires is none other than the desire of each organism to realize its form. Each natural organism has within it a desire to do those things necessary to realizing and maintaining its form. This desire is part of the organism’s form or nature itself: form is a force in the organism for the realization and maintenance of form… From a meta- physical perspective, one can see that in trying to realize its form, the organism is doing all that it can do to become intelligible.It is also doing the best job it can do it imitate God’s thought—and thus to imitate God himself”

-Jonathan Lear, Aristotle: The Desire to Understand

Your problem seems to come up because you are thinking of the good as defined primarily in terms of an organisms' form. This is correct, but then we have to ask "from whence and why this form? You seem to be presupposing a sort of indeterminacy lies prior to form. The form of an organisms just is what it is.

It might be helpful to consider why Aristotle's mentor Plato thought the divine could be neither hostile nor indifferent to what is other to it. Indeed, on Plato's account the Demiurge creates out of love and a desire to share its own self-determination and reality with an 'other,' to "give birth in beauty."

If the divine is hostile to what lies outside of it then it will be determined by those things; it will exist in response to them. But if the divine is determined by that which lies without, then it is not fully self-determining and thus not fully real as itself. Likewise, if the divine is merely indifferent to that which lies outside of it, the divine is nonetheless still defined by "what it is not." It is only in love, in a transcedent identification of the self with what is other, that the divine can be fully determined by what lies within the ambit of its identity and self, as opposed to being defined by and in terms of the other.

This is of course Plato's view, laid out most clearly in the Timaeus, but I don't think Aristotle rejects this part of Plato.

But Aristotle’s divinity is not only intelligible content or form but also thought itself, the act-of-intellection. Here we find, perhaps more explicitly although with less graphic imagery, the togetherness or coinciding of thought and being that we discovered in Plato. “Thought thinks itself by participation in the intelligible; for it becomes intelligible in touching and thinking, so that intellect and the intelligible are the same; for intellect is what is receptive of the intelligible, that is, of reality [τοῦ νοητοῦ καὶ τῆς οὐσίας]. And it is in act possessing." Met. Λ.7, 1072b20–23).

Richard Perl - Thinking Being

In Metaphysics XII Aristotle expands a bit more on the relationship between the human good and the divine.

The First Principle upon which depend the sensible universe and the world of nature.And its life is like the best which we temporarily enjoy. It must be in that state always (which for us is impossible), since its actuality is also pleasure.54(And for this reason waking, sensation and thinking are most pleasant, and hopes and memories are pleasant because of them.) Now thinking in itself is concerned with that which is in itself best, and thinking in the highest sense with that which is in the highest sense best...

Hence it is actuality rather than potentiality that is held to be the divine possession of rational thought, and its active contemplation is that which is most pleasant and best.If, then, the happiness which God always enjoys is as great as that which we enjoy sometimes, it is marvellous; and if it is greater, this is still more marvellous. Nevertheless it is so. Moreover, life belongs to God. For the actuality of thought is life, and God is that actuality; and the essential actuality of God is life most good and eternal. We hold, then, that God is a living being, eternal, most good; and therefore life and a continuous eternal existence belong to God; for that is what God is.

All goodness for organisms is filtered through their forms, but the forms themselves are not ordered to nothing at all, but to being itself. This is why Aristotle is often seen as presenting the germ of what would become the Doctrine of Transcendentals, the convertibility of Unity, Truth, Goodness, and sometimes Beauty, with Being.

The life of contemplation described in Book X of the Ethics is not good only in virtue of an arbitrary essence that man happens to have. It will be the highest good for all rational creatures in so much as they are rational. -

Pragmatism Without Goodness"Must be no being," does not mean "lacks being." This would be to say "the One does not exist." Plotinus is not saying that. He is denying the univocity of being, the idea the the One could be organized on a Porphyryean tree as one being existing alongside others. It is being itself (or superbeing) not a being. Augustine, Aquinas, Eriugena, etc. all agree on this point. Plotinus is here affirming a form of the Analogia Entis which he expands on throughout the work (see 6.8.8).

Your confusion stems from thinking of the will primarily in terms of potency. Plotinus follows Aristotle in that the Unmoved Mover must be pure act, not act deriving from potency. You are asking "how can there be act without something external to draw it out of potency?" This doesn't make sense in either Aristotle or Plotinus.

Absurd also the objection that it acts in accordance with its being if this is to suggest that freedom demands act or other expression against the nature. Neither does its nature as the unique annul its freedom when this is the result of no compulsion but means only that The Good is no other than itself, is self-complete and has no higher.

Plotinus is talking about the Good here, not Nous. Earlier, when discussing what freedom is he speaks in terms of Nous to avoid the difficulties of analogy, but Nous does not possess what the Good lacks, which is made clear below and in 6.8.8 and 6.8.9.

The objection would imply that where there is most good there is least freedom. If this is absurd, still more absurd to deny freedom to The Good on the ground that it is good and self-concentred, not needing to lean upon anything else but actually being the Term to which all tends, itself moving to none.

Where is there most good? In the Good itself. What is freedom for Plotinus?

He calls denying freedom to the Good "absurd."

Where-since we must use such words- the essential act is identical with the being- and this identity must obtain in The Good since it holds even in Intellectual-Principle- there the act is no more determined by the Being than the Being by the Act. Thus "acting according to its nature" does not apply; the Act, the Life, so to speak, cannot be held to issue from the Being; the Being accompanies the Act in an eternal association: from the two [Being and Act] it forms itself into The Good, self-springing and unspringing.

What do you think the Act is here? It seems to me you're saying the One is being without thought, which goes against Plotinus entire metaphysics (see the quote from Perl above). The Act does not spring from nature because it is not set over and against nature as in beings (again, pure actuality, not act flowing from potency). But this is clearly not saying "there is no Act." (And this is referring to the Good itself, it is saying this must hold for the Good because it even obtains in Nous, not "it only obtains in Nous and the Good lacks what Nous has")

Plotinus is here arguing specifically against the very argument you are trying to make, the idea that act requires being determined by something that lies external to the Good (or temporality, covered in 6.8.8)

If you look at the next section you will see that Plotinus both denies a univocity of the freedom of beings to the freedom of the Good and yet also denies total equivocity as well (again, affirmation and negation lead the way here).

Section 6.8.8 also speaks to your insistance on thinking of Act in terms of temporality, "happening," "not yet," "striving towards," etc.

To return to the previous topic, this presence of intentionality is as true for Aristotle's Unmoved Mover (which Plotinus is drawing on and makes reference to) as well. The Unmoved Mover is said to enjoy things in Metaphysics XII for example. -

Pragmatism Without GoodnessI mentioned Perl and this might be helpful for why the One cannot lack intentionality and why, having Act united to Being, Act cannot be "for no reason at all," which indeed would be the opposite of divine freedom.

But neither is being ‘mind-independent,’ as if it were prior to and could exist without, or in separation from, intellect.There is no thought without being, but neither is there any being without thought. In order to avoid subjectivism, it is necessary, as Plotinus says, “to think being prior to intellect” (V.9.8.11–12), but this is only because in our imperfect, discursive thinking they are “divided by us” (V.9.8.20–21), whereas in truth they are “one nature” (V.9.8.17). Neither thinking nor being is prior or posterior to the other, for, just in that thinking is the apprehension of being and being is what is apprehended by thought, they are ontologically simultaneous: “Each of them [i.e., each being] is intellect and being, and the all-together is all intellect and all being, intellect in thinking establishing being, and being in being thought giving to intellect thinking and existence … These are simultaneous [ἅμα] and exist together [συνυπάρχει] and do not abandon each other, but this one is two, at once [ὁμου] intellect and being, that which thinks and that which is thought, intellect as thinking and being as that which is thought” (V.1.4.26–34).

As Plotinus here says, however, “this one is two:” the unity of being and intellect cannot be a simple or absolute identity.Within the “one nature” (V.5.3.1) which is at once intellect and being, Plotinus finds it necessary to distinguish between the ‘seeing’ and the ‘seen,’ between intellect as act and being as content.That which thinks itself “is not separated in reality [τῇ οὐσία] [from that which is thought], but being with [συνὸν] itself, sees itself. It becomes both, then, while being one” (V.6.1.5–8). This again follows from Plotinus’ recog- nition of the intentionality of intellect. Thinking is necessarily a thinking of something: it is directed toward, is the apprehension of, some content: “Every intellection is from something and of something” (VI.7.40.6).

As St. Thomas points out in the commentary on Boethius' De Trinitate, we cannot think of this thought in terms of human discursive reason, since the latter is drawn out into parts. But neither can it be completely equivocal. The Absolute is the fullness, pleroma, of content though, not sheer contentlessness on account of simplicity.

[/quote] -

Pragmatism Without Goodness

Firstly, the “Divine Intellect” is clearly not equivalent to the One.

Yup, that's the basics of the cosmology and the hypostases. Nous is the result of the One's vision of itself. “In turning toward itself The One sees. It is this seeing that constitutes The Intelligence” (1.7)

The difficulty for St. Augustine in digesting this cosmology is that Nous, which is quite similar to the Christian Logos, e.g. in Origen (or the Barbelō in Gnosticism) is obviously not coequal with the One. This ultimately is what leads to Augustine's rejection of the hierarchical model for a semiotic triad as the model of the Holy Trinity.

But, because I so far can’t think of any such understanding of the term “will”, I can only then find the passage you’ve quoted to utterly misinterpret what Plotinus quite directly affirms (as per the above quote) in putting into Protinus's mouth terms such as (supposedly the One's, right?) "absolute self-will". The One (for that matter, this much like the typically understood Buddhist notion of Nirvana) is in want of nothing, hence devoid of any intent not yet fulfilled, and, thereby, fully devoid of volition, aka will, this as will can in any way apply to the "Intellectual-Principle".

Is there some other sense of will you understanding wherein purpose is, at the very least, not a necessary condition of the will’s occurrence? (A purpose-devoid willing?)

First, because Plotinus is engaged in analogical predication and sort of "pointing" as opposed to "describing," he frequently affirms and the negates his affirmations. As he says early on, the truth of what he says is to be found in contemplation not discursive reasoning. Nonetheless, simplicity does not imply a total equivocity of all words, else his project would make no sense.

To embrace an absolute via negativa, to say that nothing of God can be said except that God is not anything, is itself to slip into the very sort of total equivocity you yourself seem to point out as inappropriate.

Second, is your contention that the One is completely devoid of all intentionality and that simplicity demands that it be thought of as an almost mechanistic principle, devoid of any content since any content would introduce limit? Does Nous possess something positive that the One lacks?

I don't feel like arguing something completely at odds with Plotinus entire metaphysics. Even at the level of the Intellectual Principle, the thinker is the same as the thought, and the knower is the same as the known, transcending any distinction between Being and Knowing. Parmenides' "the same is for thinking is for being," sits at the heart of Plotinus' metaphysics and epistemology.

I don't mean to be rude but have you actually read the entire Enneads or any secondary literature on Plotinus? There seems to be a lot of modern assumptions packed into your thoughts here about the difference between thinking and being, a divorce of intentionality and existence, that simply do not make any sense in Plotinus. Something like Perl's "Thinking Being," could help explain the profound difference between Plotinus and the implicit dualism that pervades modern thought when it comes to intentionality.

Anyhow, consider the entire discussion of divine freedom in 6.8. At 6.8.3 Plotinus discusses freedom in created beings. Freedom can't be just doing what one desires, else infants would be free. Freedom is proper to the intellect, one must know what one wills and why one wills. Plotinus uses Oedipus killing his father out of ignorance as an example; here Oedipus is determined by a truth that lies outside his understanding.

But then Plotinus brings up a problem very similar to the one you have raise. If one is determined, by nature, by the Good, then is one truly free? For here the Good striven for must lie outside the person, or even for the Good itself, it seems it would be unfree in that it acts "according to its nature." But Plotinus rejects this objection, and he rejects it particularly for the Intellectual Principle (which as we shall see applies for the Good itself as well).

Further, this objected obedience to the characteristic nature would imply a duality, master and mastered; but an undivided Principle, a simplex Activity, where there can be no difference of potentiality and act, must be free; there can be no thought of "action according to the nature," in the sense of any distinction between the being and its efficiency, there where being and act are identical. Where act is performed neither because of another nor at another's will, there surely is freedom. Freedom may of course be an inappropriate term: there is something greater here: it is self-disposal in the sense, only, that there is no disposal by the extern, no outside master over the act.

In a principle, act and essence must be free. No doubt Intellectual-Principle itself is to be referred to a yet higher; but this higher is not extern to it; Intellectual-Principle is within the Good; possessing its own good in virtue of that indwelling, much more will it possess freedom and self-disposal which are sought only for the sake of the good. Acting towards the good, it must all the more possess self-disposal for by that Act it is directed towards the Principle from which it proceeds, and this its act is self-centred and must entail its very greatest good.

This seems to be Plotinus rejecting your argument tout court.

Now if we take the modern view of freedom/will where both are defined in terms of potency, we may run into difficulties here. But Plotinus is not laboring under the idea that will is primarily potency and must be driven externally into act. Act and being are united in 6.8.7:

This state of freedom belongs in the absolute degree to the Eternals in right of that eternity and to other beings in so far as without hindrance they possess or pursue The Good which, standing above them all, must manifestly be the only good they can reasonably seek.

To say that The Good exists by chance must be false; chance belongs to the later, to the multiple; since the First has never come to be, we cannot speak of it either as coming by chance into being or as not master of its being. Absurd also the objection that it acts in accordance with its being if this is to suggest that freedom demands act or other expression against the nature. Neither does its nature as the unique annul its freedom when this is the result of no compulsion but means only that The Good is no other than itself, is self-complete and has no higher.

The objection would imply that where there is most good there is least freedom. If this is absurd, still more absurd to deny freedom to The Good on the ground that it is good and self-concentred, not needing to lean upon anything else but actually being the Term to which all tends, itself moving to none.

Where-since we must use such words- the essential act is identical with the being- and this identity must obtain in The Good since it holds even in Intellectual-Principle- there the act is no more determined by the Being than the Being by the Act. Thus "acting according to its nature" does not apply; the Act, the Life, so to speak, cannot be held to issue from the Being; the Being accompanies the Act in an eternal association: from the two [Being and Act] it forms itself into The Good, self-springing and unspringing.

I don't know how you read this to imply "the Good lacks all intentionality." It says the opposite and is essentially refuting your argument. Other things seek the Good, the Good intends itself. Why do you think he is at pains to show that Act and Being are not separate?

The objection that "because the Good is a unity and unique it can intend nothing," is called absurd here. To be sure, words are imperfect, but "since we must use words here," Plotinus speaks of Being united to Act.

A God that intends nothing is an idiot God. It is not a free God (at least not for Plotinus who defines freedom primarily in terms of intellection not potency). It would essentially mindless mechanism.

Whereas a God who lacks intentionality would seemingly lack being on Plotinus view of being. Or if we cannot say it has intentionality because of a total equivocity that no analogy can span, then what exactly is Plotinus talking about in his entire project?

Ps. I’m here asking for cogent reasoning, preferably yours, and not for the questionable opinions of others regarding the matter.

You presented an argument about "Christianity" and "Neoplatonism" in general. I happen to be very familiar with the classical Christian tradition and some later medieval philosophy. I pointed out that you are making assumptions that these traditions would absolutely reject.

What more cogent reasoning do you need? Your premises would be judged false, ergo your conclusion is not demonstrated. The premise "if there is intentionality it must be directed towards something exterior and something temporal," in particular is not going to sail. It's not going to sail on Plotinus' view either.

But please reference the translation of Plotinus you’ve quoted. I ask because it is utterly discordant to the translations I’m so far aware of

The quotes in that post are from D.C. Schindler's (a philosopher primarily focused on classical and medieval philosophy, who is fairly prolific and well cited in those areas) Retrieving Freedom not Plotinus. -

An Argument for Christianity from Prayer-Induced Experiences

Is this much suffering really needed for self-transcendence?

I don't know. The same sort of question would seem to crop up elsewhere. How absurd does the world need to be for us to become existentialist overcomers? How meaningless does it need to be for us to become self-generating overmen?

My inclination would be to say it requires the maximal absurdity and meaninglessness that still allows one to overcome.

Though this might work as the basis of a useful fiction to solve the above trouble for Christian eschatology, is self-transcedence permanent? Can't one fall back into imperfection?

On most theologians views, no, definitely not. Because the goal is deification and once deification has occured the will is not corruptible. As St. Augustine puts it, the soul facing the beatific vision has become fully free and is thus incapable of sin. Sin requires some sort of deficit. The question then is explaining this initial deficit.

At the same time, given apokatastasis is not orthodox, I don't give it much merit.

Well, universalism was at its most popular in the first five centuries of the church, and was most popular where people were more literate and could read the Bible in their native language. Several Church Fathers affirm it or heavily imply it.

It was not the majority opinion, which was annihilationism, the destruction of unrepentant souls. Infernalism, the belief that the "second death," in Revelation actually means "eternal life, just really unpleasant" is virtually absent from the earliest centuries and only gains ground later. Straightforwardly universalist phrases are everywhere in the New Testament, in all four Gospels, in almost all of St. Paul's letters, in St. John, and in St. Peter. Annihilationst language is also common, but less so. Infernalism has Matthew 25:46 and that's about it.

Universalists don't deny Hell of course, just that it is everlasting and purely punitive instead of corrective. Early views had essentially all souls headed for purgation (generally justified using the same Scripture used to justify Purgatory today).

I'm not sure exactly what is "orthodox" here. The Eastern and Oriental view of Hell differs dramatically, and you can find Oriental sources proclaiming apokatastasis as matter of fact well into the Middle Ages.

Plus, Catholic theologians dance around this issue quite often. Just off the top of my head, Von Balthasar, Pope Benedict (hardly a radical), Thomas Merton, and Pope Francis. They never decidedly go this way, but they leave the door open for "hope" as Von Balthasar puts it. -

Pragmatism Without Goodness

One can always fall back on “God is beyond all human notions of logic, including the basic laws of thought, and hence beyond all human comprehension”, but if God is nevertheless understood as having intended and/or intending anything whatsoever then there necessarily is some end/purpose not yet actualized which God strives toward in so intending - hence making God’s actions purposeful - and this will then be blatantly incongruous with the notion of Divine Simplicity, among others.

But this is profoundly misunderstanding the classical tradition, Thomism, etc. Pace Maimonides, who only recognizes the via negativa and apophatic theology, the Christian tradition generally, and Thomism in particular, is based around analogical predication vis-á-vis the divine nature (to be sure though, the entire Christian tradition is heavily affected by Pseudo-Dionysus' apophatic theology, and Plotinus' comments on unknowing would fit right in with St. John of the Cross or the anonymously written Cloud of Unknowing). There is no retreat into total equivocity, at least not in influential thinkers. In fact, this is what the tradition is at pains to deny, and this is still a focus of Catholic thought (as set against some Protestant theologians), e.g. Pryzwara, Ulrich, Balthazar, etc.

Probably the biggest influence Plotinus had on the Christian tradition was his conception of divine freedom, so I am not sure how these are supposed to be completely opposed on your view. Pseudo Dionysus certainly builds on this conception of divine freedom, but it remains the same at heart. The entire idea of "an end lying outside of God," and "an end God strives towards," requires knocking out core premises in the classical tradition in the first place.

For example, on a comparison of the view best embodied in Plotinus, Proclus, and Porphery:

Divine freedom is thus the absolute contemplative act, thought thinking itself, which does not exclude, but necessarily includes, a “natural” procession of goods from the perfectly immanent intellectual act as its fruit: God creates what is other through the thinking of himself. What tends to be excluded in the Greek tradition, however, is any sense of relationship between the fontal goodness and the individual beings that constitute the cosmos specifically in their uniqueness and individuality. It is just this form that undergoes a transformation in the Christian appropriation, which we have seen in principle in the various figures we have studied [St. Denys, St. Augustine, St. Anselm, St. Maximus, St. Bonaventure, etc.], especially those with a more ontological approach to the theme of freedom.

D.C. Schindler - Retrieving Freedom

If anything, it is Plotinus' whose views trend closer to the voluntarism that would come to dominate some strands of Protestant theology after the Reformation. Not that it trends close to it, but the seeds are there and St. Denys is at pains to walk back those elements (St. Maximus as well).

In the light of these elaborations, let us look at a summary statement about the freedom of the One that Plotinus (significantly) presents already in the first chapter of part II of the treatise. Here he describes the Good’s self-relation, noting the constant qualification of “something like” (hoion), which indicates analogy, and noting too the description of the Good’s simplicity as an identification of its essence and its existence, or in Plotinus’s (not yet technical) terminology, his hypostasis and his actuality (or energy):

But when [the Good’s] hypostasis, so to speak [hoion], is the same as his energy, as it were—for one is not one thing and the other another if this is not even so with intellect, because its activity is more according to its being than its being according to its activity—so that it cannot be active according to what it naturally is, nor will its activity and its life, so to speak, be referred to its substance, so to speak, but its “quasi-substance” is with and, so to put it, originates with its activity and it itself makes itself from both from eternity, for itself and from nothing. (6.8.7.46–54)

There are three things to highlight in this passage.

First, Plotinus clearly has Aristotle’s Metaphysics 12.7 in mind here, referring as he does to this highest actuality and including reference to nous, substance, life, and eternity, all of which occur in Aristotle’s famous passage, not to mention the allusion to Aristotle’s claim that, in the unity of being and knowing, being has a relative priority to the act of knowing in the sense that thinking does not produce being but conforms to it (we will come back to this crucial point at the end of this chapter.) Second, Plotinus spells out the steps of the transcendence as we laid them out above: the Good’s actuality is not “according to nature” in the immanent sense, which is why we cannot simply describe it as life, except analogously; nor is its activity according to substance (ousia). The subject of the will is not nature per se or substance per se but simply the self (τὸ αὐτὸ), which lies beyond both. But this does not in the least imply that the self-constituting activity is opposed to nature or substance, in the sense that these are first given and that the activity then must either conform to it or diverge from it. Instead, Plotinus says what we take to be the third point to highlight, namely, that its “quasisubstance” and its “quasi-activity” emerge at the same time. The Good is what it wills to be, and it wills to be what it is.This, in the most compact nutshell, is Plotinus’s theory of divine freedom. [Consider Exodus 3:14 "I am that I am," and "tell the 'he who is' has sent you" and how much the Patristics made of these]...

By describing God as absolute self-will, or indeed absolute will-self—the meaning of which we need yet to unpack—Plotinus explicitly rejects what he calls “a bold discourse” (τις τολμερὸς λόγος), which turns out to represent what would seem to be the only alternative, namely, that God does not will himself to be (and to be will!) but first “just is” and then wills himself as a kind of recognition of what he already has been. Because God is by definition, so to speak, absolutely first, there can be nothing “prior” to him to which one might appeal to account for him; regarding God, he explains, it is not possible to ask the two most fundamental philosophical questions, the “why” question concerning final cause, and the “what” question concerning formal cause, but this is due to an overabundance of intelligibility rather than an absence of it...

To a modern ear, absolute freedom as absolute self-will sounds like the very limit of arbitrariness and blind power: consider Schopenhauer, Schelling, or Nietzsche, not to mention Jean-Paul Sartre. But this is simply because the modern ear has lost its capacity to hear the melody of the good and beautiful, so to speak, that constitutes the music of freedom. For Plotinus, it is simply impossible to conceive of the will apart from its relation to goodness; the very “discovery” of the will in Plotinus’s philosophy is a result of reflection on the “nature” of the Good.

The source of freedom, the One, cannot simply be lacking in freedom (see: 6.8.7.42–46), and pure arbitrariness is not freedom. Hence "ends," although Plotinus, and the classical Christian tradition, understand these analogically.

As to possible commonalities between diverse traditions - here primarily addressing the Neoplatonic notion of the One and some subspecies of Abrahamic thought - if there is a perennial philosophy, then this would account for different traditions' diverse interpretations of the same Divinely Simple, uncreated and imperishable, essence which, to here use Aristotle's terminology, is the unmoved/unmovable (i.e., changeless) mover (i.e., change-producer) of all that exists. Although, as I previously argued, this could not rationally be an intentioning God (e.g., God as described in the Torah/Bible, imv most especially as addressed in Genesis II onward).

You don't need an appeal to perennial philosophy, Plotinus grew up in a hotbed of Jewish and Christian Platonism. IIRC he was coming of age as Origen and Clement were at the height of their influence and they themselves are dealing seriously with the Gnostics, who are also big in Alexandria at the time (Gnosticism existing within orthodox churches to a large extent). The ideas are all in the milieu Plotinus is growing up in and being educated in, and of course there were pagan Platonists exchanging ideas with these traditions the whole time as well. But some Gnostic texts strike me very much as "Neoplatonism predating neoplatonism, just heavily mythologized."

One can always fall back on “God is beyond all human notions of logic, including the basic laws of thought, and hence beyond all human comprehension”, but if God is nevertheless understood as having intended and/or intending anything whatsoever then there necessarily is some end/purpose not yet actualized which God strives toward in so intending - hence making God’s actions purposeful - and this will then be blatantly incongruous with the notion of Divine Simplicity, among others.

Ignoring your placing God in time again (which violates divine simplicity and would be vigorously rejected by pagans and Jews/Christians alike), on this view none of the major Neoplatonists are Neoplatonists. -

Any objections to Peter Singer's article on the “child in the pond”?

I don't think an amount equivalent to about 1/5th of US public sector spending divided up amongst amongst the entire world is going to solve global poverty. A much greater amount of spending hasn't even solved US poverty. Social Security is about that amount by itself and Medicare is another trillion dollars. That's split between 58 million US seniors and is inadequate to lift many out of poverty.

The same sort of argument would obviously still stand even if somehow every person on Earth had a requisite number of calories. In many low income countries, obesity is now a larger problem than hunger at any rate. Simply moving excess food from other countries in isn't a panacea either because, in the poorest countries, much of the workforce works in agriculture. Lowering the cost of food has the effect of crashing domestic incomes, which in turn leads to people abandoning their farms and flooding into urban areas, bringing on all the problems of compressed urban poverty.

So, while the problem is hardly insoluble it also isn't easy to solve either. -

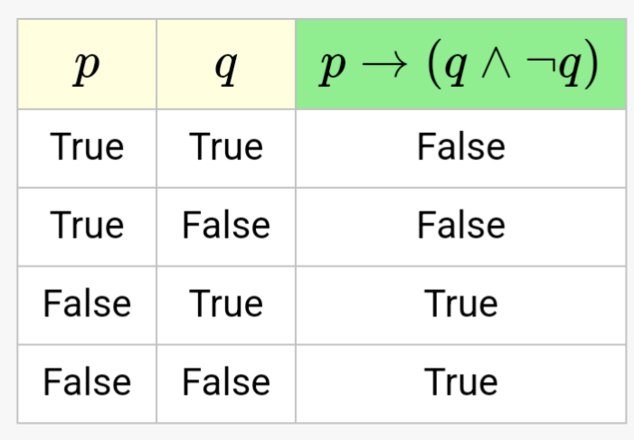

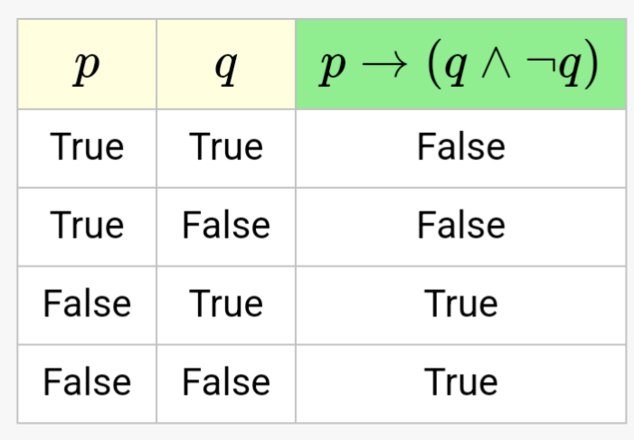

Do (A implies B) and (A implies notB) contradict each other?

I don't think there is any mystery around (A→(B∧¬B)) |= ¬A, if something implies a contradiction we may say it is false. My curiosity was more around ¬(A→(B∧¬B)). We know that ¬(A→(B∧¬B))↔A is valid, (A→(B∧¬B)) entails ¬A, and ¬(A→(B∧¬B)) entails A. Tones gave a translation of the latter as:

"It is not the case that if A then B & ~B

implies

A"

I still can't make sense of it.

These are just paradoxes of material implication, no?

The negation of a contradiction is always true, and being true it is implied by anything, true or false.

As I noted earlier in response to Tones' reductio, a reductio is an indirect proof which is not valid in the same way that direct proofs are. You can see this by examining your conclusion. In your conclusion you rejected assumption (2) instead of assumption (1). Why did you do that?

Same here, it seems to me to be a paradox of material implication that is the source of confusion.

In a normal conversation, we might ask "but what if A really only implies B and not B and not-B?" Or conversely: "what if A only implies not-B but does not actually imply B?" But the way implication works here it is not an additional premise we can reject, we don't assign a truth value to it except in virtue of the truth values of A and B themselves.

If A is true then B always implies it, whether B is true or false.

In a relevance logic or per Aristotle's comments, we might turn around and question if A truly implies either B or not-B regardless of the truth value of either A or B alone.

For example, we could set up something like:

Elvis is a man - A

Elvis is a man implies that Elvis is both mortal and not-mortal. - A → (B and ~B)

Therefore Elvis is not a man.

Obviously, the common sense thing to do would be to reject "Elvis is a man implies Elvis is non-mortal," while affirming that "Elvis is a man does imply Elvis is mortal."

A truth table won't lay those possibilities out, it will only tell us how things work in terms of A or B being true.

However, there is a quite good reason not to do this in symbolic logic. Once you start getting into "what 'really' entails what," you get into judgement calls and a simple mechanical process won't be able to handle these.

But of course, you still need judgement to make sure your statements aren't nonsense, so you just kick that problem back a level. A proof from contradiction is only going to be convincing if we believe that A really does imply both B and not-B. I know plenty of skepticism has been raised against proofs from contradiction in general, outside of this issue, but for many uses they seem pretty unobjectionable to me. -

Are actions universals?I've looked into this since it seems like it would come up at the intersection of process philosophy and realism. People have certainly proposed actions as universals, but it has really not garnered much attention from what I've seen.

Part of the problem is that the universal is called on to explain "what stays the same" across various instances but then a processual universal must in some way incorporate change within itself. -

A Case for Moral Anti-realism