-

The American Gun Control Debate

It isn't.

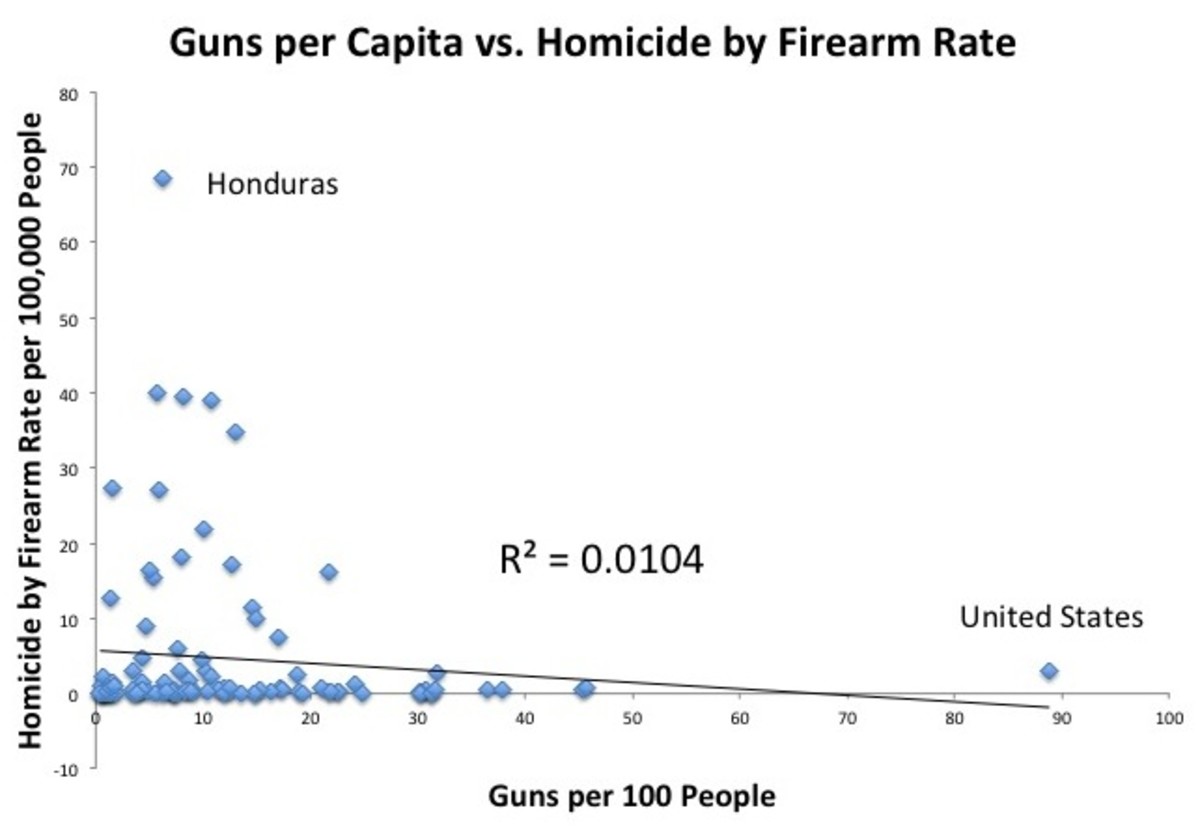

Yes it is. "The US has more mass shootings," can be true, and "fire arms ownership is not correlated with homicide rates across the world's countries," can both be true. The one does not refute the other. Nor does the weak correlation denote that gun control wouldn't reduce homicides in the US. As I pointed out, the relationship is weak because guns are expensive and homicides tend to be higher in poorer countries for a host of reasons not directly related to firearms. Second, very violent countries are more likely to have banned fire arms, but they will still be violent due to the initial conditions that spurred the gun control, which makes the relationship look weaker.

I'm all for gun control, but advocates do themselves a disservice by wanting to argue that there is any simple, direct relationship between the prevalence of firearms and homicides. Even time series data is fraught, because the US gun craze intensified greatly across the 90s-2010s even as our violent crime rate plunged nationally.

I am in favor of stricter gun control. I think mass shootings are a large enough issue to warrant gun control. But this has nothing to do with the point I was making, which is simply that you can have extremely high rates of firearms ownership without much by way of violent crime. The counter point to that is not "yes, but the US has more mass shootings." It would be "no, northern New England doesn't have a lot of firearms and low crime," which isn't true.

Spree shootings aren't common enough to shift the numbers on US homicide rates generally, which is why the numbers you're looking at do nothing to belie the fact that there is a weak, often negative correlation between firearms ownership and homicides at the state/county level.

IDK, I haven't seen those numbers. I would imagine that if they were strong, gun control advocates would use them more often, instead of blending suicide deaths in, which opens them up to attacks since there is a strong substitution of methods in suicide cases, and banning guns doesn't seem to be a particularly effective way to reduce suicides (unlike gun violence). But there are shooting accidents, so I'm sure it does move the numbers. -

The American Gun Control Debate

The comment was that there were areas of high gun ownership with very low crime, which is true. The entire state of Vermont is an example. The correlation is weak for countries too, but this has more to do with homicides being more common in low income countries and firearms being expensive.

Nor does 2014 look much different from 2004.

My point isn't by any means that gun control doesn't work. Evidence is that it does. My point was that some people fail to understand this because they live in relatively wealthy counties with quite low violent crime despite many people owning fire arms. And they can look to cities and states with much strict gun control and see far higher crime there, including crime using firearms.

The correlation does exist if you use enough controls (or cherry pick your sample), but then hacking becomes a concern. The correlation is also strong if you consider all gun deaths, but then suicide is normally not what the debate is about (when you see a strong correlation between "gun deaths" and gun ownership, this is including suicides.)

Spree killings common enough to be relevant for the gun control debate, but not common enough to meaningfully effect overall US homicide rates.

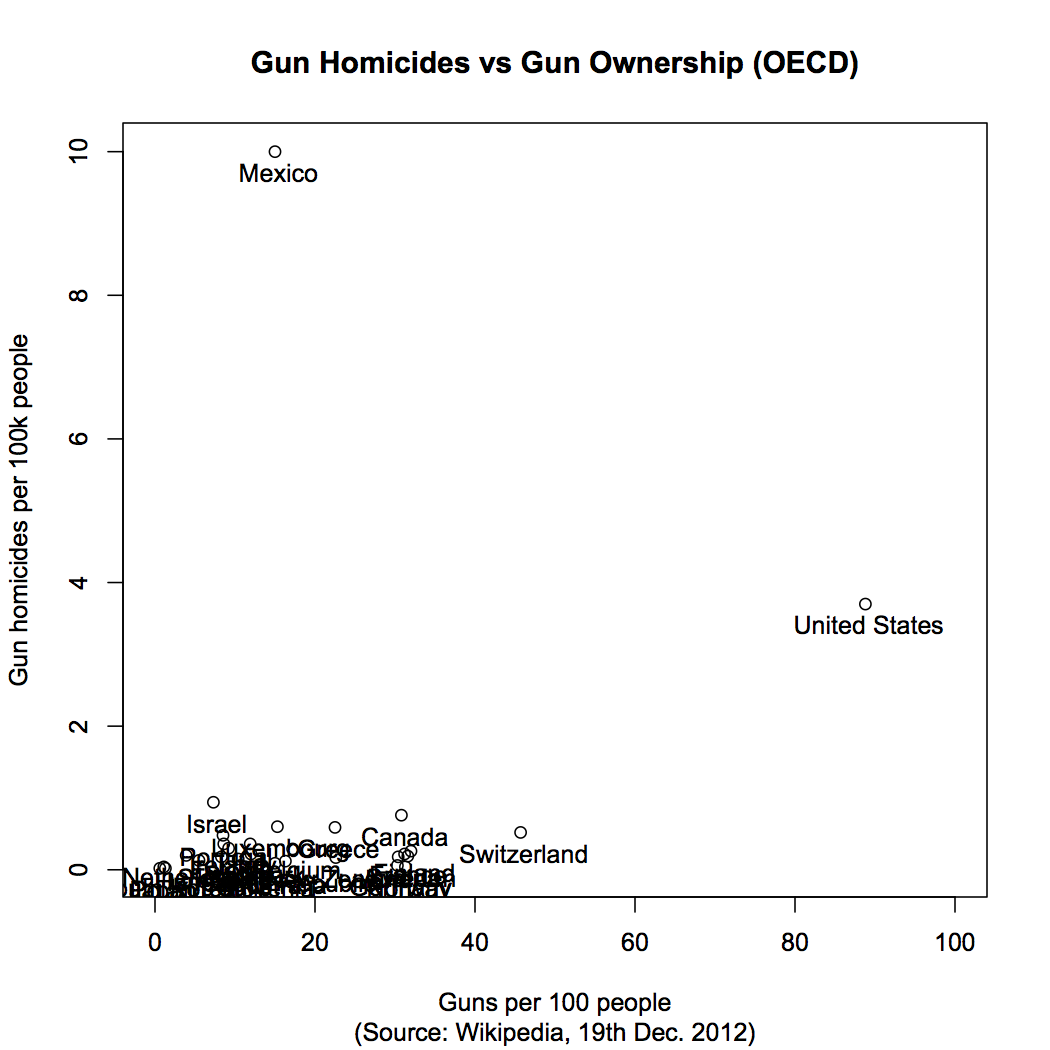

For example, if you consider the OECD as a sample:

It's not that there isn't a relationship, it's that it isn't straightforward or simple.

This is only tangentially related to what I said though. I was talking about low crime areas within the United States, of which there are many.

Not to mention, how do you pick you "developed countries," for the sample. If you excluded the US, Switzerland would be an outlier and your relationship is destroyed. -

Does Religion Perpetuate and Promote a Regressive Worldview?

For me progress is like morality. We might base it on presuppositions around notions of the flourishing or wellbeing of conscious creatures (as I do) but not everyone will agree on values. If you wish to defend, (for instance) that dictatorship is better than democracy then let's hear the argument.

Right, this is exactly my point re religious attendance. Based a wealth of research in the social sciences, religious attendance seems to boost the metrics we use to measure flourishing. And religious attendance also seems to boost a number of prosocial behaviors, like volunteering and charitable giving. Given its effect size, it's the sort of thing we would expect social scientists and policy folks to advocate in favor of, but for all its historical and political baggage.

And yet, as you rightly point out, religious attendance also tracks with a number of regressive attitudes. So it seems to me like it is a mixed bag, strongly progressive in some ways, and strongly regressive in others, and the principles that determine how strongly each factor presents itself transcends "religion" as a category.

How many churches will let trans women speak?

Many. You see rainbow and pink and blue trans flags on churches all the time. I would even wager they are the most common place to find such symbols on display. But this in no way contradicts the fact that most churches/mosques, etc. aren't open to trans individuals speaking.

It's a mix. The academy is extremely vocal in its efforts to promote diversity and equality. What broad industry puts more of a focus on diversity? In California, there were questions over whether an opening for a physics professor should have "track record of efforts to promote minority inclusion in the field," as a criteria for assessment alongside their ability to contribute to new research in the field, but the very fact that these are equal criteria speaks to the heavy focus on "inclusion."

And yet where is one more likely to find ethnic minorities and low income individuals, in the academy or in a Catholic church or mosque?

This is sort of like how progressives were angry that support was thrown behind Joe Biden in 2020, allowing him to defeat the more progressive Bernie Sanders. On the one hand, the administration would now be less progressive. On the other, the choice of Biden above Sanders reflected minorities' pick for the candidate more than white voters. Particularly, Biden was significantly more popular with African Americans, while Sanders won with white voters.

And this is where I think it gets tricky. Because self determination itself seems like a progressive good, and yet in many contexts it can also lead to regressive policy. Mosques in the West seem like a powerful progressive force in uniting the advocacy and political efforts of a minority group, and yet this advocacy can often lead to more regressive policy preferences. But religious institutions also motivate progressive reforms themselves (civil rights, the expansion of social welfare programs, universal education) and in this way the relationship doesn't seem straightforward to me.

This is true for less obviously political settings too. Without the YMCA and YWCA, or JCCs, some areas would have significantly less access to subsidized or free child care, enrichment programs, and women's shelters. The Catholic Church can push its followers to advocate for regressive policies on the one hand, and use donations to support refugee settlement on the other, settlement that people who see themselves as "highly progressive," often fight on account of Not In My Backyard sentiment ("yes, the Church settling refugees is fine, but not in my school district please. Low income housing? No thanks, put it down in the inner city.")

As a side note, there is some good evidence that refugee settlement works better in rural areas (Kentucky, Bosnians, Maine, Somalians), despite these places being more insular and conservative. It's an interesting phenomena. -

The American Gun Control Debate

Sure. The relationship between gun ownership and assaults/homicides extremely weak nationally. There is also a negative relationship between gun ownership and homicide rates internationally, with the highest homicide states in the world, mostly in Latin America, having quite low rates of firearms ownership.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/4332143/state%20gun%20ownership%20homicides.jpg)

But this is sort of a chicken and egg problem. Many Americans cities with the strictest gun control laws have some of the highest homicide rates. However, historically, they often only have strict gun control laws because of their high homicide rates, and gun control still seems to reduce homicide rates to some degree.

You do, however, have wealthy, highly educated counties with extremely low, European levels of homicides and fairly high firearm ownership (e.g. Vermont as a whole).

That said, there is a positive relationship between all "gun deaths," and gun ownership. This includes accidents (rare) and suicides (suprisingly common in the US). But generally, what people are most concerned about, is the crime.

People from low crime, high trust areas where fire arm ownership is more common than not seem to have a hard time understanding how their hobby can have such disastrous consequences elsewhere, because weapons are easily moved from place to place. It gets reduced to, "why punish the person who is doing everything right?" And from there, it's easy to turn this dissonance towards "government plots," to roll back freedoms. -

Truly new and original ideas?

One person's;new idea is someone else's old one.

Yup. And even when new thinkers make original contributions to older ideas, we have a bad habit of backwards projecting the new ideas onto the old. E.g., I am a very big fan of Wallace's "Philosophical Mysticism in Plato and Hegel," and yet it seems to me that Wallace's Plato is more the future "Plato" of the "middle Platonist" Jews and Christians (Philo, Origen, Cyril, etc.) and of the "late/Neoplatonists," (Plotinius, Porphyry, Proclus, Augustine, Eriugena, etc.).

Not that the seeds of these ideas cannot be located in Plato, but they seem a lot stronger in those he influenced.

But we also tend to allow a large set of ideas to accrue to "great names," in this way. -

Does Religion Perpetuate and Promote a Regressive Worldview?

This gets to an interesting question: by progress do we mean the metrics that technocrats tend to use: self reported well being, income, educational attainment, crime rates, etc. or do we mean subscribing to a specific set of beliefs and policy positions? Further, we might ask, is democratic participation a good in and of itself, even if it leads to regressive policies, or is democratic process only a means to progress?

This comes up in the real world, as when ballot measures to recognize gay marriage (a progressive good) were hurt by higher turn out among low income and minority voters (generally taken to be another progressive good). And it comes up when "progressive ends," are sought using highly regressive means.

Just to take one of your examples; isn't gun control simply a means to an end, fewer murders and assaults? We have plenty of areas of the US where gun ownership is extremely high and gun violence is extremely low. If religious observance reduces violent crime, isn't it already achieving the good we want (to some degree at least). I generally think the problem people have in accepting gun control is in being unable to generalize and identify with others. They are unable to see the negative effects of gun sales outside their lived context. That and they get too focused on liberal absolutes, the idea that, as a rule, freedoms shouldn't be taken away from the responsible due to other's responsibility.

I think this is a flawed way of looking at things; it fails to account for the way society functions as a whole, not a collection of individuals.

But my point here would be that various goods seem to cut against each other. In general, when progressives claim that low income individuals "vote against their own interests," the claim is that they are mislead, lacking in knowledge about what the "good is." Yet it is still assumed that they are seeking the good.

However, when the focus turns to outgroups, this assumption tends to go out the window. The pursuit of "bad policies" becomes tied to intrinsic qualities related to the outgroup (just see prior replies). The problem is then framed as intrinsic lack of intelligence, as opposed to contingent lack of knowledge or manipulation. The problem is wickedness, as opposed to differing opinions of the good.

But I'd tend to say that religion is regressive to the extent that it constrains knowledge or allows for manipulation, but can also be quite progressive to the extent that it leads to identification with others and a focus on rationally seeking the "good" and putting efforts towards that end.

Further, we could question how contingent the political-religous divide is. Religion has historically been a driving force on more "left-wing," political movements, and the current alignment in the West seems partly contingent to me. For example, early Christianity was unique in the roles it created for women. Saint Paul mentions female deacons, bishops, and apostles, and female prophets were a major part of early controversies in the Church. A return to the gender norms of the era only occured over future centuries of pushback.

Likewise, while many churches today are a force for enforcing traditional gender roles, they are also almost certainly the most common place where people go to hear women lecture on philosophical, spiritual, and moral issues. Philosophy as an academic discipline has a huge gender imbalance, whereas even denominations that don't allow for female head ministers (Baptists, etc.) frequently allow women to preach and lecture, and women are the decided majority in modern church life.[/b]

Hence, it is a blend in terms of influence. While churches may tend towards regression in political views, you're also far more likely to see women speaking than in academic settings. I don't think this is simply because the gender slant is reversed. Churches also speak much more often to classically defined "women's issues," than secular outlets for discussing philosophy. Not to mention that universities aren't called "ivory towers," without cause. You need a credential to speak in most cases, a credential largely awarded to males. Meanwhile, women from all walks of life might speak at a church, and often do. (And even in the academy, theology/divinity has a far more equal gender distribution than philosophy). -

Does Religion Perpetuate and Promote a Regressive Worldview?

I think I agree, if I'm understanding you correctly. The term "good," taken alone, without the possibility of anything being "bad," is contentless. Our understanding of the terms advances, but this in no way makes the term contentless in all contexts. On the contrary, it's the dialectical advance that gives the terms content in the first place.

But, without answering questions about the relationship between the universal and the particular, the many and the one, I don't know how well we can pronounce judgement on the opposition between such apparent opposites, except that such opposition cannot be "strict" or "absolute," in a naive sense.

Returning to the topic on hand, where exactly did this sort of idea come from? As best I can trace it, it seems first to spring from Eriugena, a monk writing theology, at least in terms of the dialectical aspects of change. And then Hegel, following similar ideas (probably through Boheme and Eckhart) popularizes a move towards a less naive analysis that navigates the gap between the Scylla of naive Platonism and the Charybdis of strict nominalism. This is, to my mind, a great example of religious thought being progressive.

Of course, religion is highly regressive in many contexts (in the sense the term is used in the OP.) My point would be that "the general principles by which theologies, philosophies, and ideologies become either progressive or regressive seems to transcend the secular/religious divide." You can compare on the one hand the old indulgence system, or Protestant justifications for African slavery in the United States, and on the other the centrality of churches to the Civil Rights Movement or religion's key role in promoting the first universal education systems and universal literacy (e.g. Puritans and the Massachusetts Bay Colony). Nor are individual groups always one or the other. The Puritans set up highly progressive educational and welfare systems, and were the first to ban slavery, but they also executed people for witchcraft and drove people into exile over theological differences. -

Does Religion Perpetuate and Promote a Regressive Worldview?

I agree with what you're saying, although I don't think religion has a straightforward relationship to the promotion of a libertarian and voluntarist conception of free will and responsibility. It's quite the opposite in Calvinism. Man is "totally depraved," and he does only evil, but for the workings of God. Actions are predestined and subject to divine foreknowledge, leading to fatalism or compatibilism (Romans 8, etc.) People cannot boast in their moral actions or in their salvation, for these are "through grace alone," in the form of "unconditional election." That is, nothing about us, as individuals, determines that we shall be moral, only God's free choice.

What you're describing sounds more like the Pelagian position, which, while common in Christianity through the ages, was also considered a heresy even by the early church. Bonaventure might talk about the world as a "ladder up to God," but it is a ladder only given and climbed by "grace," a free gift from the divine.

Yet is religious grounding always bad? I would say no. The thing we are grounded to in Platonism and the panentheistic vision of God displayed in Patristic theologians is transcendence, knowledge, freedom, and goodness itself. We are always drawn on to "go beyond" our initial desires, drives, instincts, biases, and beliefs. Christianity was, in this form, a much more universal religion. Johannine Logos Theology claims the intellectual insights of Plato and Aristotle (and in modern forms Zen, etc.) as its own, since all human knowledge springs from the same source, man's desire for "what is truly good," not what merely "appears to be good and brings pleasure."

Building on the vision of reflexive freedom — freedom as rational, unified self-determination — laid out in Romans 7, the idea was that we are free to the extent that understand our motivations and the world. We are free to the extent that we transcend our initial finiteness in reaching outwards, beyond our limits, in knowledge and self-identifying love. Or, "we are free to the extent that we are 'in' God, who is in 'all things'" since we then identify with the totality of the self-determining whole. But this idea, less clearly articulated but still present in Plato, developed by the early Patristics, and then re-paganized by folks like Plotinus, who drew on orthodox, Jewish, and Gnostic thinking, was first challenged by Islam, wounding the tendency towards universalism, and later shattered in the Reformation. You see a similar thing in Islam, where violent struggles against Pagan steppe nomads and crusading Christians caused the religion to become less universal and less focused on the role of knowledge, gnosis, in morality, or the identification of the self in "other" of love.

That said, such sentiment still stuck around, and you can still see it in modern settings. But this gets back to the "No True Scotsmanesque" problem of "you shall know them by their fruit." Do you take the legalism, the focus on the letter of the law versus the spirit of it to be primarily a historical narration of what happened during Christ's earthly ministry, or do you take it as a warning to all believers. What is meant by "I desire mercy not sacrifice?" -

Does Religion Perpetuate and Promote a Regressive Worldview?

I don't want to get sidetracked. My point was merely that, according to peer reviewed findings in the social sciences, the gold standard of evidence in the scientist framework, religion seems to be more a progressive force, at least within wealthy countries. Of course, this analysis is extremely complicated, because one might assume that only certain kinds of people have the wherewithal to get up early on weekend mornings to hear what, in most traditions, is going amount to a moralizing lecture. That said, time series data also shows a marked improvement in the behaviors we tend to take an interest in (namely crime) with increased religious attendance.

So, my point would be,by what standard do we say religion is regressive if this is what our gold standard is telling us? Our feelings? Our anger that people deny what we think is solid, blatant evidence for the way the world is? The fact that we can anecdotally point to "some people of group x" are terrible? But if our data tells us that religious attendance will tend to make them better, couldn't we suppose they would be even worse if they didn't go to religious services?

And indeed, that's what the research on the plunge in evangelical church attendance and its ties to radical right-wing beliefs and support for violence seems to suggest. People already in the "far-right" space don't tend to "get better" when they leave church. They tend to get more paranoid, more supportive of violence, etc.

Because in general, throwing out anger-laced anecdotes, appeals to "the lower intelligence of that whole group," etc., the stuff of PF's threads on religion, is generally not taken as sound reasoning. -

Does Religion Perpetuate and Promote a Regressive Worldview?

The statement was about "religion" generally. Neoplatonism is religious.

Belief in ridiculous New Age hokum is plenty strong with people who hardly ever step inside a house of worship. The odds that someone believes that "US Democrats are involved in an international pedophile ring and sacrifice children to Moloch," Q Anon, is actually associated with people dropping out of church attendence. Secular madness seems plenty potent as well, from street gangs to "the world is ruled by reptiles," to modern Neo Nazism, to the millenarian Marxism of prior generations. The whole nuRight is strongly areligious, yet they're even more noxious than Mike Pence, with their calls for global race war, etc.

During the French Revolution, the guillotine wasn't fast enough to dispatch all the priests and nuns they wanted to do away with, so they had to resort to building boats with removable panels so they could chain people inside and drown them by the boatload. The comparison case then, doesn't seem particularly strong to me.

I'm just talking numbers from the social sciences. "Religions organizations have done bad things," is obviously very true. We can look to plenty of sectarian wars and the horrors the wrought, etc.

However, teachers have been implicated in plenty of child abuse cases, and school districts regularly try to cover up and settle these cases. Are public schools are force for regression? Daycares? Summer camps? What is the comparison case here?

Because for religion to be regressive, it would seem to imply that irreligion promotes progress, and that doesn't seem particularly easy to justify. -

Does Religion Perpetuate and Promote a Regressive Worldview?Hegel, Cantor, Maimonides, Descartes, Dogen, Avicenna, Augustine, Eriugena, Proclus, Newton, Eckhart, Avarroese, Leibniz, Porphyry, Pascale, Maxwell, Berkeley, Ibn Sina, Bonaventure, Hildegard, Al-Ghazai, Cusa, Erasmus, Rumi, Merton, Plotinius, Anselm, Abelard, Al-Farabi, Ibn Kaldun, Plato, Schelling, Bacon, Magnus, Boyle, Kelvin, Eddington, Pierce, Godel, Faraday, Mendel, Pastier, Lister — quite the regressive bunch to be sure. Hell, there are a bunch of priests, monks, and imams in there!

One might ask, regressive as opposed to what exactly?

Weekly religious attendance is a curb on criminal behavior, child abuse, drug abuse, and divorce unrivaled by any welfare program or pilot program. Per Gallup, a whopping 92% of people who attend religious services at least once a week are "satisfied with their lives," a dramatic advantage over the general populace. A 9.1% increase in income in time series analysis also recommends it. Charitable contributions, even to non-religious organizations (on top of religious donations) are higher.

A technocrat could be tempted into prescribing religious attendance as a go to policy based on the data. But of course, the question of causal direction here is tricky.

In any event though, it seems hard to justify the idea that religion makes people particularly more regressive. We've seen attempts to remove religion, and Stalin's Soviet Union, Mao's China, or the Paris of the Terror don't exactly scream "progress," any more than the Thirty Years War or the Crusades.

Seems to me like a case of the fundemental attribution error of social psychology. "I see people of group X doing bad things, so it must be because of the type of people that group X are. I see people I identify with doing bad things, it must be because of their circumstances." -

Israel killing civilians in Gaza and the West Bank

Yet I don't think the orders are for the IDF to perform genocide. However, with unrestrained bombing, a tiny area filled with over 2 million people totally dependent on outside logistics and incapable of fleeing the battle, this is very difficult. It can easily become so that nobody can refute you.

This hasn't been the policy at least. While people talk about "indiscriminate," attacks, I don't see it. Israel certainly has the munitions to do what the US did to Tokyo or Dresden. But there is still a difference between total destruction and appropriate ROE, so it's not that "everything Israel is doing is appropriate," just that these maximalist claims are unsupportable.

By way of contrast, the Strip has 37.5% more people than Mosul. When the Iraqi Army and Peshmerga retook Mosul from the Islamic State, seeking to displace a force about a third of the size of Hamas' military component, 40,000 civilians were killed. If you're trying to remove an enemy that is digging into urban areas and comfortable using them as shields, this is the sort of thing you face. This was generally not an event where there were complaints about egregiously loose ROE; I don't recall any internation controversy.

By contrast, a recent event that did have egregiously loose ROE would be the Siege of Mariupol, against a much smaller resisting force. Scaled up to the Strip's population, such action would be the equivalent of 110,000-140,000 civilian fatalities. But even then, the Russian forces weren't pounding areas of the city they controlled to kill as many civilians as possible. They were simply completely indifferent to civilians and also punitively hitting civilian targets in areas they didn't control. -

Ukraine CrisisOctober was the first month of the war where Russia fired less shells than Ukraine. Originally, Russia was sustaining almost 16 times as many fire missions as Ukraine. Now Ukraine is carrying out about 20% more. Ukrainian fire missions haven't fluctuated much over the course of the war, but have been slowly trending upwards with new equipment.

At the same time, the share of all confirmed destroyed artillery (a good proxy for what is in use) has shown a dramatic decrease in 155/152mm guns as a share of all artillery for Russia, and an increase in 120mm guns. This bespeaks the ammunition and tube shortages. The very rapid fire mission rate early in the war probably also contributed, as you only get so many fire missions out a tube before it is degraded, and it will eventually be nonfunctional. -

A Case for Transcendental Idealism

I can understand the mechanics of Determinism, in that our choice at state S2 has been pre-determined by state S1, but the mechanics of free will elude me, causing me to come to the conclusion that the world is Deterministic and our belief that we have free will is just an illusion.

The mechanics of compatibilist free will, as I see it, are the same as the mechanics of determinism. Questions about freedom are questions about: "to what extent we are self-determining as opposed to being externally determined." This also explains how we can be unfree when constrained by internal causes. E.g. the agoraphobic who cannot attend their daughter's college graduation because they lack control over their fear of leaving the house, the alcoholic who wants to quit drinking, agrees it is the better choice, but cannot resist their urges, etc.

We can be alien to ourselves and lack self-control, and indeed, a good deal of the freedom we care most about is freedom over ourselves, freedom to engage in self-determination. Self-knowledge becomes crucial here as well, as we can be manipulated or choose things out of ignorance. Crucially, gaining knowledge is itself a transcendent act. Learning involves going beyond current beliefs and desires, the expansion of the self. By expanding the self, we can become more self-determining.

Mechanically, it works the same as fatalism, but fatalism seems to ignore the ways in which we also "determine ourselves." We can identify with and exercise control over what determines our actions. For example, if our work is a very important part of our life, then switching to a job with a very horizontal, consensus-based management style gives us more freedom, in important ways. We are freer in that we do more to determine our actions and feel ownership over our work. Likewise, we are always determined by the politics of our locale. But if we identify with our polity and exert influence on it, then the political determination of our actions becomes less external determination, more internal determination, in that we identify with the previously external force that determines our actions and exert causal control over it. But the control we exert still works through deterministic means. An absolute monarch is deterministically influenced by their polity, and yet, they also clearly possess great internal causal powers vis-a-vis their state.

It is quite absurd to consider that there is a theater in the brain, so why would a theory describing a method for what goes on in the brain, make room for one?

:up:

But then it seems to me that "representation" is really more about how we describe relations within the parts from which the cognitive system emerges, not the relations that obtain between the whole cognitive system and the objects of experience. Our sight of a tree is not a tree, but nonetheless, I feel confident in saying we "see trees," as opposed to "representations of trees," in an important sense. Information is, by its nature, relational, so "in-itselfness" itself seems to be a fraught abstraction. -

A Case for Transcendental Idealism

There is also the humoncular regress to consider. If we "see representations" by being "inside a mind" and seeing those representations "projected as in a theater," then it seems we should still need a second self inside the first to fathom the representations of said representations, and so on. Else, if self can directly access objects in such a theater, why not cut out the middle man and claim self can just experience the original objects?

It's a weird sort of inversion on the Allegory of the Cave. Instead of things being more real by virtue of being more necessary and self-determining, properties understood by the mind are downgraded into the shadows on the cave wall. In this way, the most contingent, least knowable becomes more veridical, the higher "thing in itself," while apparent necessity becomes a "creation of mind."

But if we reject the sort of ontological dualism that motivates such an explanation, I see no reason to assume that a red post can't have properties vis-á-vis how it relates to a person. The mistake is to go looking for an "in itselfness," of things like red. It's like asking "what does a thing look like without eyes?" Or "how is it conceived of without a mind?" Well, it isn't. Relations obtain between things and asking them to inher "in themselves" in the first place seems to be the category mistake.

Another way to think of it: assume objects are defined by their properties. "Looking red," is a relation an object can possess. Thus, it is a property of an object.

People reach the Kantian problem by other routes through supposing the objects must be more fundemental that properties, that properties "attach" to objects. And here you get the idea in contemporary metaphysics of "bare substratum," and pure haecceities," which start to look very similar to the noumenal on closer inspection. This just seems like a misstep to me, born out of attempts to define "identity," in terms of properties and relations. -

A Case for Transcendental Idealism

I don't see a need to bring physical states into it. When we choose something, we either choose it for some reason, or we choose it for no reason at all (it is random action). If it is random action, then it is arbitrary, not free. If we have a reason for chosing something, then those reasons determine our actions.

And our reasons for choosing different things have to do with our beliefs and opinions, our knowledge and judgement. It seems to me like the development of all of these is uniquely tied up with states of affairs in the world, and thus our choices are tied up with (determined by) states of affairs as well. We might choose to love who we love and despise who we despise, but we do so because of who those people are. Thus, those choices are "determined by," who those people have revealed themselves to be.

Freedom can't be something like: being in state S1 at T1 and, based on nothing but free floating "freedom," we either go to S2 or S3. That's just randomness. The "choice," between S1 and S2 has to be based on something for us to do any "choosing." Further, we seem less free when we are forced into choices by coercion, instinct, uncontrollable drive, etc., so it seems like we can be free in gradations and we are more free when our choices are "more determined by what we want them to be determined by," not when they are "determined by nothing."

And we can't say our "choosing between," is "determined by our freedom," because this is circular. It leaves the choice free floating, determined by nothing, and so random.

Physical states, dualism, etc. don't really make a difference on this point IMO. Rather than speaking of "choosing between," it might be better to say that we are free: "when we do what we want and don't do what we don't want," when "we want to have the desires we have," and when we "understand why we have those desires and still prefer that we have them" — a sort of recursive self-aware self-determination, as opposed to a free floating non-determinism. -

Personal Identity - looking for recommendations for readingThe opening parts of Axel Honneth's Freedom's Right have a pretty good overview major developments in the philosophy of freedom. He develops a typology of:

-Negative freedom from constraint

-Reflexive freedom as freedom to control one's own actions (rational control over desire, instinct, and circumstance), as well as the development of 'authenticity' (i.e. being your real self).

-social freedom - since we can constrict or empower each other's freedom, we need social institutions that reinforce freedom at the social level.

It's an academic book, so expensive, but if you have a university library you should be able to get it, or there is always LibGen. The parts that do the review are fairly short, the rest is interesting, but more a look at how Hegel's particular theory of freedom applies to our modern world.

Frankfurt's conception of "second order desires," is big in this area. This is our ability to "want to desire x," i.e. to have desires about our desires. Here is a decent summary.

https://philosophy.tamucc.edu/notes/frankfurts-theory

This ties into the biological side of autonomy when we think about how the prefrontal cortex and a "global workspace," might allow for a recursive examination of our own desires.

Last rec is a bit of a weird one. It's Wallace's Philosophical Mysticism in Plato and Hegel. This might be less helpful, but I do feel like Wallace explains his key points pretty early on and so you don't necessarily need to read the whole thing. Just search for the part where he considers Plato's Republic and the concept that "we prefer what is really good, not what we think is good."

Wallace gets at an important way in which self determination and autonomy has been defined in the history of philosophy. We become free by "going beyond," our current desires and beliefs because "we want what is really good, not what we currently think is good/true." It is in this "going beyond," that we transcend our current limits, and can thus "expand ourselves," in accordance with our reason and become more self-determining. And of course, for both Plato and Hegel, what is more self-determining and necessary is more "real," because it is less simply a "bundle of effects," a thing caused by that which is external to it.

Might not be relevant to you. I like it because it is a view of Platonism that is consistent with naturalism, and one which plays nice with science. Indeed, science is a prime example of such "going beyond," our current beliefs and desires. -

Israel killing civilians in Gaza and the West Bank

It's seems to me that allegations of genocide have to come with actual genocide to be meaningful, not just "genocidal intent among some of the members." It is not that the latter isn't worth pointing out or criticizing, but that it would apply to virtually all wars of any significant size.

If every war with massacres of civilians and attempts to displace populations was a genocide, than virtually every war is a genocide. Maybe they are in a sense, but then the term loses any value in international affairs.

By such a standard, Yemen's Civil War would be a war of genocide, as would Iraq's. The Vietnam War, the Russo-Ukrainian War, the Iran-Iraq War, Pakistani intervention in what is now Bangladesh, Algeria, the Russian Civil War, much of the Chinese Civil War, etc.

But it seems to me that the term "genocide" needs to apply to something more than "at least some leaders express such intent," and "at least some attacks are carried out showing such intent." If that's the bar, then it would also be the case that Hamas is guilty of "carrying out a genocide of Jews in Israel," by virtue of publically expressing such goals and carrying out attacks explicitly designed to further them. This seems wrong. Hamas isn't carrying out a genocide because of 10/7; the term has to be attached to some sense of scale. Russian actions in Bucha, heinous as they were, were likewise not "genocide."

It seems wrong in part because a study of most conflicts will find attacks like October 7th occuring very often, and because it seems ridiculous to say that Hamas, who is in such a militarily weak position, is guilty of "committing genocide." By such a metric, North Vietnam and the Vietcong would also be guilty of "genocide," because of events like Hue as well.

By such a weak definition, the PLO certainly committed genocide in Lebanon, because they massacred the populations of Lebanese Arab villages, destroyed their cultural heritage, etc., with the aim of removing them from the area. And then Lebanese groups would be guilty of genocide as well, carrying out similar attacks against Palestinians. And Russia would be guilty of "genocide," in Ukraine for its punitive strikes, executions, and population transfers.

Here, one can't really debate the absolute vileness of such acts. The reason they are not genocide is because genocide is a term that needs to apply to scale. Else you could easily have it that the victims of most genocides are themselves "committing genocide," whenever there are counter massacres.

Thus, in comparing scale we should look at the explicit examples. In Rwanda, 800,000 people were killed over the course of 100 days. During the Holodomor, 3.5-5 million were killed from 1932-1933, with deaths heavily concentrated in areas Stalin had denied food to, areas in Ukraine that were then immediately resettled with ethnic Russians (who there was plenty of food for). In Syria, where genocides against minorities have been carried out locally, 500,000-600,000 have been killed.

I would draw a distinction between that and Russia's actions in parts of Ukraine, but it isn't to "excuse," such acts in any way. It's just in scale and unified purpose of such efforts.

In this, the history of the conflict over Palestine does not seem like a genocide, with the possible exception of both parties' attempts at ethnic cleansing in 1948. This doesn't make their actions any less heinous, but the distinction has to remain meaningful.

Decades of conflict have not produced a very large number of fatalities (significantly less than other wars in the region). Population growth in Israel has remained strong due to continued immigration, but the Arab Israeli birth rate is higher as well. The Occupied Territories are subject to all manner of oppression, but their population has soared faster than almost anywhere on Earth in recent decades (actually a major problem/source of the collapse in standard of living.)

Until the decoupling of the OT's from the Israeli economy, the residents had significantly higher incomes than their Arab neighbors as well.

If simply being oppressive, offering a low standard of living, and responding to terrorism and protest with a massive use of force was genocide, then a very large share of the world's states fall into that category, cheapening the term.

Even indiscriminate mass killing is not necessarily genocide. US fire bombing of German and Japanese cities was never aimed at erasing those populations, but at forcing their governments to capitulate and reducing their ability to wage war. Israel has not been blanketing the strip in indiscriminate shelling and fire bombing— the death toll would be many times as high if they were, for they are well capable of doing what the US did to Tokyo.

IMO, to call either side's actions genocide is to simply cheapen the term such that, by any objective standards, it would apply almost anywhere. The Taliban would then be a genocidal force, the Soviets in Afghanistan as well, North Vietnam, etc. And then the imperative to "stop genocide," becomes impossible to meet, because it becomes equivalent with stopping all warfare.

Nor do I think the enlightened West would act particularly different. If the Swiss government carried out a 10/7 style attack on French, German, or Italian cities, you could certainly expect that there would be a counter invasion and heavy use of air power in urban areas. Actually, for all their righteous proclamations, given their actual track record and ability for complex air ops, combined with their aversion to casualties, I could definitely see the French just leveling all of Zurich in such a scenario (source: all of European history before the EU).

The condemnation due to Israel is rather due to their broader historical role in creating the situation, not simply that there has been an attempt to destroy Hamas at all. They are at fault in that they helped create Hamas and the situation they find themselves in, not because they are using military force to remove a hostile government that carried out an attack against their population. -

A Case for Transcendental Idealism

Ah, I've misunderstood you then. I was thinking of the way in which a logic gate is deterministic in roughly the same way neurons, cells, etc. behave as such.

But you are right, the structure of computers is set up with all sorts of artificial constraints such that inputs will flow into outputs in a straightforward manner, based in human logical operators. A person does not work this way, I agree.

The difference between serial processing and the single set of "instructions" in the Turing Machine head and the decentralized parallel processing at work in animals is profound. -

A Case for Transcendental Idealism

I would argue that some sort of determinism is a prerequisite for free will. We can't choose to bring about some states of affairs and not others based on our preferences unless our actions have determinant effects. We must be able to predict the consequences of our actions, to understand ourselves as determinant cause.

Likewise, arbitrary action is not free. Randomness isn't free, it is simply determined by nothing. But to be free, we must be determined by ourselves. Self-determinination is always relative for human beings, we can be more or less in control, more or less our authentic selves.

So the problem with 's contention for me is not in assuming free will, but in assuming that freedom comes from not being determined by "inputs." But if our actions aren't determined by the way the world is, inputs, what would they be determined by? And in what way would they now be free?

To my mind, Plato has the best answer to this conundrum. The fact that a person will tend to always prefer "what is really good," over "what they currently think is good," (Republic 5) shows the potential for reason to always go "beyond itself." It is in going beyond, in transcending current belief, emotion, and opinion, that we can achieve an "ascent" towards self-determination. And then, what is self-determining (not mere effect caused by external sources) is, in an important sense, more real (hence, self-"actualization.") -

A Case for Transcendental Idealism

:up:

I figured it might be something like that. I've read the Tractus and PI, but not particularly closely (I don't think I ever finished the Tractus) and PI in particular doesn't exactly lend itself to easy interpretation. -

Israel killing civilians in Gaza and the West Bank

I don't think it's that far of a stretch. They haven't delivered on any of their promises. They haven't delivered on good governance or quality of life improvements. And now they have openly declared that all the people they rule over by force "want to be martyrs," following their unilateral decision to start a war.

Not only this, but they also kept their plans for the war secret while stockpiling supplies for themselves, preparing for their own saftey. They then started the war, and have since seemed more focused on protecting their strength and themselves than defending against the attack they provoked (the IDF has encircled Gaza City and begun to push into urban areas and losses do not suggest anything like a "heavy" resistance).

And now they seem unable to even keep meaningful support from allies in a time of crisis, making armed struggle, the very thing they are committed too, look even more hopeless. If Iran won't step in now, it never will. And Hamas will never be able to overwhelm Israel. Leaving a change in strategy as the only realistic option. -

Israel killing civilians in Gaza and the West BankNasrallah's first speech since the attacks did not sound good for Hamas' hopes of a wider conflict.

"The October 7 operation was planned in total secrecy, even other Palestinian factions were not privy to it, let alone resistance movements abroad."

“The international community keeps bringing up Iran and its military plans, but the October 7 attack was a 100% Palestinian operation, planned and executed by Palestinians for the Palestinian cause, it has no relation at all to any international or regional issues.”

Hamas has already complained about the ineffectual response from Hezbollah, and that seems unlikely to change.

Despite some public moves in support of a cease fire, Hamas has yet to embrace that position with any consistency. Per the last interview with a politburo member:

"We must teach Israel a lesson, and we will do it twice and three times. The al-Aqsa Deluge [the name Hamas gave its October 7 onslaught] is just the first time... Will we have to pay a price? Yes, and we are ready to pay it. We are called a nation of martyrs, and we are proud to sacrifice martyrs.”

In the interview, Hamad says that Israel must be wiped off all “Palestinian lands,” i.e., must be completely annihilated, claiming that its existence is “illogical.”

But I wonder if this posture will change now that the response from allies has been about as unequivocal as you could expect it to be for public statements.

I imagine a cease fire would have to come with some sort of public statement about not carrying out additional October 7th style attacks whenever feasible. Not that Hamas will, or even should be bound by such statements, but because, if they want a ceasefire, they should realize that Israeli leaders need cover for one as well. Thus, there has to be some sort of shift in the language away from "such attacks will continue as soon as possible," and "total annihilation."

But, since both sides have face to lose in relenting first, I think we may be unlikely to see a move toward changing the rhetoric re "total destruction of Israel" and "total destruction of Hamas," until private negotiations bring about a mutual acknowledgement.

I still find it a bit strange though, because both militarily and in terms of protecting their people, a ceasefire would benefit Hamas, so I would think their messaging would follow the strategic imperatives. And if their goal is to win wider support, dropping the threats of continued attacks of the same nature (explicitly targeting civilians), while asking for the ceasefire seems like a no-brainer.

They did walk back the nature of the attacks, making an appeal to the targeting of civilians not being their goal, which is at least a move in the right direction. But it wasn't said very forcefully, and given the intent obviously was to massacre civilians, they probably need to expand on their view of future efforts. At least some acknowledgement of "mistakes were made," on the most heinous acts, not "everything was justified." You can claim the attack was justified and still say your soldiers might have "acted rashly," and blame it on the combat environment, etc. Diplomatically, claiming executing toddlers is "totally justified," is a non-starter.

It could be that the reason Amnesty and B'tselem refer to it as Apartheid is because the international community took action against Apartheid and that is what they believe is needed now.

Good point; I hadn't thought of that. -

Israel killing civilians in Gaza and the West Bank

Right, there is a great deal of discrimination within Israel proper. I just don't know if South Africa is the best analogy for that given the ways in which Arab Israelis are integrated into the economy, politics, and fabric of social life though. To my mind it seems more like Jim Crow, or even more so the less formalized, defacto Jim Crow or the northern US in the decades prior to the 1960s-70s (which was often none kinder for being less explicit).

Although, interestingly the wealth gap between households and educational achievement is not as large as gaps that exist in the US, with a good deal being explained by much lower employment rates for Arab women 28.3% vs Jewish women 61.6%. This is partly due to a cultural difference; the gap for men is much smaller, although still quite significant, showing the effects of job discrimination as well. This is not so much a defense of the noxious Israel system, as a signal of the scale of US issues.

The difference would lie in returns on wealthy, since the Black-White income gap is a bit smaller than the Arab-Jew gap in Israel, but then the wealth relationship flips, probably because of how much the US system is set up around the principle of "to those who have, even more shall be given" (all sorts of policies that inflate wealth so long as you scrape up to a certain level). -

Proposed new "law" of evolutionBTW, this sort of general process, as applied to the traits that corporations, states, and cultures pick up is exactly the sort of thing that I think would explain Hegel's intuition about historical development in mode modern empirical terms.

Essentially, Hegel is right. There are contradictions internal to systems. Their representation of the world is at odds with it. Thus, they need to absorb, to sublated the contradictions. It's a sort of selection process. -

A Case for Transcendental Idealism

...or is Wittgenstein correct

in his belief that we cannot think without language. He wrote in the Tractatus para 5.62: “the limits of my language mean the limits of my world.”

Not being an expert in Wittgenstein, I wonder what he thought of people with aphasia, who lose the ability to understand and/or produce language? Surely they still think, right? But it's possible he wasn't aware of those issues. Or is he defining thought in such a way that it always includes language? (Seems odd).

In any event, it seems wrong to say that language would be the limit of our world. Languages can always be expanded, and often are. There is no real limit to what existing languages can convey if properly expanded.

Indeed, all computable functions can be detailed using mere binary code. And it's a strong, (if not super well founded) supposition on physics that the universe "is computable," or "describable in computable terms." This would seem to make our processing throughput, our bandwidth, in essence, our "concious awareness," the limits of our world. And that seems more obvious as the limit.

On the flip side, we also have experiences we lack the ability to put into words. But we can, through hard effort, gnaw around the edges of the ineffable, something you see in Merton, Pseudo Dionysus, Eriugena, etc. But this doesn't show so much a limit on our language itself, but our ability to wield it. It's a limit on languages ability to live up to our full capabilities. -

Proposed new "law" of evolutionI saw this paper too. It's an idea I've seen in a lot of places. "Selection-like" phenomena show up in all sorts of places outside biological evolution and at different scales throughout life itself (e.g. neuronal development and pruning, synapse formation, lymphocyte lines, etc.). You also see it in non-living phenomena.

Synch by Strogatz is a pretty neat book on how different mathematical phenomena appear at different scales in a host of living and non-living phenomena. E.g., the mechanics behind the how heart cells synchronize a beat turns out to be similar to how Asian fireflies synchronize their blinking and how earthquakes form.

One thing to note here is the fractal recurrence. You have the same patterns repeating at both different scales and different levels of complexity/emergence. So, with life, you have information about the environment being encoded in genomes, but then again in nervous systems (at multiple levels), and then again in language, and then again in written texts, up to the human organizational level.

Selection-like effects have also already been studied vis-a-vis languages, corporate survival, state evolution, etc.

↪Gnomon You know, there's an old truism in science, 'a theory that explains everything explains nothing'. It suggests that if a theory is so broad and all-encompassing that it can be used to explain any observation or phenomenon, it may lack specificity and predictive power. In other words, a theory should be able to make testable predictions and provide a clear framework for understanding specific phenomena. If a theory can be stretched to explain anything, it becomes less useful as a scientific tool because it doesn't provide meaningful constraints or insights into the natural world. Good scientific theories are typically more precise and focused, allowing scientists to make specific predictions and test their validity through experimentation and observation.

Right, but studies of these similarities do make specific predictions about each specific phenomena. What they note is that the mechanisms and mathematical descriptions are shockingly similar, in some ways modeled almost identically, at very different levels of scale and emergence. The finding arises from comparing specific predictive models, thus the prediction is "baked-in" already. The question is: if the mechanism by which complexity arises in bacteria evolution, autocatalysis, galaxy formation, ant hive construction, etc. is modeled similarly, doesn't that denote a larger general principle.

Mathematics is incredibly wide, and a lot of mathematics is developed precisely to model nature. The information theory and chaos theory/complexity revolutions are surprising because the patterns across disparate fields that don't seem like they should have anything in common end up looking shockingly similar.

Maybe this shouldn't be surprising, since the same "rules" are in effect, but it does speak to fractal recurrence as its own sort of "trait of the universe." -

A Case for Transcendental Idealism

IDK, some systems seem to vocally criticize the attempts to make philosophy like mathematics. It seems to vary. -

Beliefs, facts and reality.Generally, when I've seen "facts" or "matters of fact," used in metaphysics, the term means "things that obtain regardless of what we believe about them." Thus, facts would be certain, our knowledge (beliefs) about them would not be. A fact could not be true or false, it just is.

Not that there is any one "right" way to use the word. I can certainly see the case for "facts" not being certain in this way, but I figured the distinction might be helpful.

Or, to borrow from SEP, main theories of facts are:

A fact is just a true truth-bearer,

A fact is just an obtaining state of affairs,

A fact is just a sui generis type of entity in which objects exemplify properties or stand in relations.

I find the whole fact vs state of affairs vs proposition vs event thing very interesting, even if it starts to seem downright silly sometimes.

The only truth we could ever know, the only fact 100% certain would be one that is eternally consistent. And because we can't measure anythings repeatability for eternity, we should probably just call it a day after the

first 3 or 4 measurements came out the same.

:up: sort of Hume's point re induction. -

The hard problem of...'aboutness' even given phenomenality. First order functionalism?

Given that some neural processes experience qualia, and even knowing that neural networks are exquisitely correlated with a world around,how are qualia inside the brain about that world rather than just the inside of a brain?

I think this specific issue may be a problem of misleading demarcation and division; i.e., a definitional problem. We want to explain how phenomena are "about" the world. But then we take it as a given that phenomena are "produced/occur" "in brains," without direct reference to the objects being experienced. Indeed, people often go even further, claiming (without good evidence IMHO) that we can be confident that phenomena are produced only by the activity of neurons and the patterns of action potentials.

Well, right there, we've already divided the "production of phenomena" from "objects in the 'external' world," as a given. It's assumed out the gate.

This being the case, we shouldn't be the least bit surprised if we find ourselves with the same sorts of problems that Kantians have with their dualism issues. Our scientific theories likewise presuppose that "external objects" are not part of the process of their coming to be experienced phenomenally, at least not in any direct sense. I've heard champions of Kant claim that Kant's great genius has been "vindicated by neuroscience." Maybe. But might it be that modern theories of consciousness have simply recreated his same dogmatic mistakes?

Such a division is an extremely strong tendency in how the science of consciousness is generally explained. However, I don't see much strong scientific support for the division. It is generally supposed that, if we see a tree, it will be because a tree is actually in front of us. That is, the tree is part of the physical processes that produces the phenomenal experience of the tree.

On the face of it, I see nothing wrong with saying that objects actually possess properties related to how they are experienced. It seems to be a mistake to assume that any phenomenal properties must be created by "the brain." This is just crypto dualism (and not even that hidden).

Putting it another way, "being experienced" is a relationship a tree can have with a person. This "being experienced" can be thought of as a unified physical process involving both tree and person. There is no real division I am aware of, the processes that make up the person seeing the tree, the tree, and the surrounding environment flow into one another, and demarcating them in any absolute sense is impossible.

A person placed in front of a tree in a vacuum does not see a tree. They will be quite dead. There is no light to reflect off the tree either. Experience is only "produced by brains" under an extremely narrow and (on the cosmic scale) extremely uncommon set of environmental conditions. It only appears to us that brains go on producing consciousness in all sorts of environments because we avoid going into the types of environments that cause consciousness to cease (plus, getting into the void of space or the interior of a star isn't easy).

We also only experience external objects when there are proper interactions between us and them. Thus, to my mind, there is no reason we should approach "aboutness" as necessarily something that starts at central nervous system. However, when we presuppose that the process must start at the boundaries of the CNS, we end up with the problems of Kantianism. This means having to talk about "representation" as some sort of sui generis thing, instead of simply talking about cause and the fact that "effects are signs (representations) of their causes," in the more general sense that is true for all physical interactions.

Could facing up to functions being somehow (somehow) first-order fundamental (with implications for internalism-externalism, organic-inorganic, selectpsychism - panpsychism) help face up to the 'aboutness' problem, in a way that's consistent with known physics? (somehow)

I think so. There are some interesting ideas floating around vis-a-vis fundamental physics and information. There are ways in which we can see that physical interactions themselves have a certain necessary element of perspective; as Rovelli says "entanglement is a dance for three." There is the "thing that generates an effect" (object), "the means through which the effect is generated" (sign), and "the thing effected by the sign" (interpretant). The effect of any one sign depends on the recipient, and this is clear in even very simple cases like mixing two reactive versus two non-reactive liquids together.

A certain "aboutness" and "correlative" element seems baked in. Yet how this builds up into the "aboutness" of experience, that's a real head scratcher. I don't think we answer it by only looking at neuronal activity, however.

Although they say in passing this should use "ingredients that are widely accepted as being nothing over and above physical or functional ingredients", they don't go into functionalism.

This is a common position, but it seems wrong-headed. We've been beating our heads against the same problem for more than half a century. The wide variance between theories and continual proliferation of new theories would seem to suggest that we are missing something quite fundamental. Part of the problem may be that we start with building blocks that simply assume consciousness doesn't exist, then try to construct consciousness from them. Second, if function is going to play a key role in defining consciousness, then it seems that form probably should too. Yet our general starting point is to deny any "real" causal efficacy to form over and above efficient causes. -

Israel killing civilians in Gaza and the West Bank

What makes Israeli policy in Israel's borders similar to Apartheid? I always thought the comparison was apt, but for the Occupied Territories.

Israeli policy in Gaza is hard to compare even with Nazi policy towards the French, let alone the policies they are best known for. There is a difference between callous ROE and lack of concern for collateral damage and attempts to exterminate the population. -

Freedom and Process

BTW, I totally agree that an understanding of physics can't rob us of choice. If anything, it opens up more choices because knowledge and techne enhance our understanding and causal powers.

Physics might also be related to the metaphysics of freedom in terms of fundemental theories. Retrocausality seems to be having a moment now, as it increasingly seems like one needs to either abandon realism (there is one world and states of affairs don't depend on who is looking) and locality, abandon time symmetrical QM, or embrace retrocausality.

Retrocausality says some interesting things about freedom in a broad sense because it tell us we live in a world of "real" potentials that get crystalized into "actual histories," based on physical interactions. This doesn't directly connect to human behavior in any straightforward way, except in that we generally think of freedom in terms of our "actions" also selecting between potentials based on our internal states, so there is an intuitive overlap (which is maybe more dangerous than helpful, but interesting nonetheless). -

Teleology and Instrumentality

Incomplete Nature by Terrance Deacon is an interesting modern attempt to recover Aristotlean formal cause through thermodynamics and thus to explain purposeful behavior and the emergence of first person perspective. It isn't fully convincing, but it's the best effort I've seen.

One deficit it has though is that it assumes that information only exists in terms of life, as a given. To assume otherwise would be to introduce humonculi for Deacon.

I think this is mistaken. My hunch is that a satisfactory accounting of intentionality will include an explanation of the way perspective and semiotic elements of reality are "baked in" from the outset. Scott Mueller's "Asymmetry: The Foundation of Information," and Carlo Rovelli's "Helgoland," have some interesting points on this front. -

Freedom and Process

I would see physics coming in for defining the boundaries of an agent. We tend to think that agents are "embedded," in spacetime. That being the case, how do we delineate them?

Or we might ask: "from the perspective of physics, how do we describe how choices result in changes in the world?" Something like: "how does my choice to turn left occur within space-time and then affect local events such that my car actually turns left?"

A naive answer to this question where people are simply their bodies doesn't seem to explain the amazing context dependence of our causal powers, and our causal powers seem directly tied to choice and freedom.

If I am scared by turbulence on a flight, my freedom to land the flight early at a nearby airport is determined by whether or not I am in the pilot's seat for example, the interactions therein. If the plane is remote piloted, then I can't effect this change regardless of where I sit. But a plane being remote piloted or not is a physical difference in the system.

Self-determination seems to vary in physical systems over time and between systems. A rock is going to do very little to determine its internal states of external environment, no matter how we define them. Homeostasis, niche creation, animal behavior, all represent radically different ways in which a system determines its internal states.

So, physics can't answer many questions about freedom, but it does seem like it can help to define some aspects of how we think of it. And my general inclination is that it doesn't work to talk about "static objects" or "bodies" possessing freedom in this context. It would be better to think of leverage points and the degrees to which a sub-system determines what is within and without in response to discernible differences in inputs.

Physics can't be totally excluded from an explanation without assuming some sort of hard epistemic or ontological line between segments of reality IMHO. -

Israel killing civilians in Gaza and the West Bank

Rough approximation of the area the IDF is holding, with reports of temporary advances outside of these axes. So far, they have stayed out of denser areas (with some exceptions).

Estimates are that 800,000 of the 1,100,000 civilians who live above the river have evacuated, but that still leaves a lot of people in the area and a lot of civilian infrastructure. The more the advance stays out of urban areas the better most likely.

I have not seen any estimates for how many Hamas fighters stayed in the North. Might be impossible to tell.

I imagine the pressure to let new supplies in will grow once they have bisected the Strip, since they can't plausibly claim that they lack an ability to intradict supplies moving north. -

Ukraine Crisis

More so when you consider the concentration of prisoner losses in the limited areas of offensive operations, (Bakhmut and Pisky earlier and Avdiika now).

Over the past days Russia has declared control of the waste heap near Avdviika! Yet then the UAF published media showing the waste heap being retaken! Russia again demonstrated that they had planted a flag on the waste heap. UAF released video of Russian waste heap forces being destroyed. Then the waste heap was no man's land. Now the UAF once again appears to control the waste heap!

Last count I saw was 190 Russian vehicles destroyed in the vicinity of the waste heap. I haven't seen a count of Ukrainian vehicles, although they are much lower because they are defending and so using far fewer vehicles and not moving through enemy mine fields.

The contested landfill that has become the hot spot of the entire conflict for now.

When soldiers say they are "fighting World War I, just with drones and social media," I see why. -

Israel killing civilians in Gaza and the West Bank

"Hamas carries out attacks with the sole goal of producing an Israeli response that kills civilians so that Gazan and international opinion shifts against Israel."

Come on, this is like the Likud propaganda caricature of Hamas. I'm willing to believe plenty of things about them, but not this level of cynicism. -

Ukraine CrisisFor perspective on the use of prisoners, Russia's pre invasion prison population was 420,000. Today it is just 266,000.

https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2023/10/26/russia-prison-population-convicts-war/

How many more prisoners they can recruit for combat roles is anyone's guess. The heavy use of prisoners, who are seen as "disposable," in front line combat roles and assault teams seems like one of the causes of the incredibly high losses for the Russians (UK MOD estimate, 190,000 KIA or permanently disabled, 300,000 casualties). Leaked US estimates had Russian fatalities 71% higher than Ukrainian losses (120,000 versus 70,000), and the use of prisoners in "meat assaults," is the primary culprit per both Western defense agencies and Russian milbloggers. But once this pool is depleted, can tactics change?

Treating conscripts the same way seems to risk larger morale issues across the force. -

Israel killing civilians in Gaza and the West Bank

It probably would still be there, just in a less dominant position. The US did not give Israel much support in their most precarious war, the 1948 War. This was prior to the US Arab rift, back when the Arab states were still being courted as potential clients in the emerging Cold War system. It was only the Suez Crisis that squarely settled the Arabs on the side of the Soviets and the US on the side of Israel (more by default than due to intentional maneuvering on behalf of the US). Prior to that, the French and domestic production were the main source of Israeli arms.

Israel won the 1948 war due to significantly better

organization and morale, despite a marked material disadvantage. It was the USSR who was the main sponsor of Israel during this period, owing to the large number of contacts between Jews and new communist states that were being stood up as Soviet vassals across Eastern Europe.

One of the great ironies of the 1948 war is that it was largely fought by the Israelis with Czech surplus Kar98k rifles donated by the Soviets, rifles which had been stamped with swastikas for their intended Nazi users (a dark premonition of the apartheid state perhaps?)

Truman was not a huge supporter of the idea of Israel and Eisenhower famously ignores the Holocaust in his telling of the war. Israel only became an appealing ally after they had succeeded in setting up a functioning democracy that granted the Arabs there full citizenship and voting rights while the Arab states has lurched into pan-Arabism, an explicitly socialist program that also failed to produce any real democratic reforms. And, it's worth noting that the US probably cared more about the Arabs being openly socialist than Israel making strides towards democracy, realpolitik being what it was.

Israel's position in 1967 and 1973 would have been more perilous without US aid and sales, but they probably could have managed with French arms or using Soviet arms. The Arabs' problems ran much deeper than the differences between Soviet and US hardware, which were less significant back in the 1960s anyhow. Plus, they had their nuclear deterrent quite early, without US support on that front.

Hell, they might be in a better place without US support because it could have forced them to make more concessions for peace. Alternatively, they might be a significantly more repressive and violent regime owing to increased existential anxieties. It's hard to say. But I'd wager that they'd be around in any case. -

Israel killing civilians in Gaza and the West Bank

The Jews continued to live in the region after the Babylonian Captivity, restablishing a Second Temple (Books of Ezra and Nehemiah) under Persian rule. They later won their independence from Alexander's Persian successors, the Selucids (Books of the Maccabees). Hence the existence of Judea at the time of Rome's arrival in the region.

But we could also consider if Italy has a claim on the land because it was part of the Roman Empire for so long. Or Turkey because they Byzantines held it. Or the Vatican because the crusader states existed for two centuries. The paper trail of "ownership," in the region is very long, to say the least.

Perhaps Mongolia even has a claim, as the crusader states were at one point Mongolian vassals as part of an alliance against their Muslim rivals.

This is true everywhere. Greece and Venice have older claims to Crimea than Moscow for example.

Count Timothy von Icarus

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum