-

Reading group: Negative Dialectics by Theodor Adorno

That’s precisely what Adorno will not accept. For him, the actual is the site of reason's failure, not its fulfillment.

Indeed, and I think this makes sense given his starting point in Kant, Hegel, and the broader framework of Enlightenment philosophy, which tends towards "philosophy as a system," and a distinct totalizing tendency within these "systems." This tendency is particularly acute in Hegel's philosophy of history.

Maritain is similarly motivated in his claim that philosophy can never be a system, and can never be closed, but is rather man's openess to being. It's a problem a lot of people seemed to be grappling with during this time period.

The common appeals to the Holocaust in these discussions, now the better part of a century later, start to strike one as properly historical in particular. If reason must lose its luster, or even its authority after the Holocaust, then it should have already shed these in the wake of the Thirty Years War, the conquistador conquests, the Mongol sweep across Asia, the aftermath of the sack that gave us the Book of Lamentations, etc. Wiesel, for his part, picks the 17th century's pogroms, as opposed to the 20th's, as the setting for his Trial of God," and while Enlightenment, "rational," Dr. Pangloss style metaphysical optimism ends up being the tool of Satan, neither does the play end up seeming to exclude the Logos of the generation of Jews who saw Masada fall. In this aspect, these debates sometimes remind me of Dostoevsky's Pro and Contra section of the Brothers Karamazov, that is, there is a "I humbly return my ticket," element.

My thoughts have tended more towards rejecting the particular Enlightenment notion of reason and systematicity tout court, but I can see why, within that tradition, Adorno's proposals make sense. There has to be an irrationality in consciousness because "rationality" has become so bound up in rules and systematicity (ratio) that it seems incapable of providing its own content and impetus. It is far from the old "infinite fecundity" and the erotic. Indeed, it's downright sterile. Other thinkers of this period also had to look for "new sources" in consciousness, Jung being a good example. -

What is real? How do we know what is real?

This may have no appeal for you, but I was quite pleased with the papers cited (by Chakravartty and Pincock) in the "Epistemic Stances . . . " thread. I thought those two philosophers did an excellent job making big issues clear within a smaller, manageable discussion. Would you be willing to read them, perhaps guided by some of the comments in the thread? At the very least, you'd see that the "either it's foundationally true or it's merely useful" binary is not the only stance available.

That makes sense. I think the problems brought up there are more serious than they might seem. Just for one example, an anti-realism that makes science a matter of sociology seems to be able to keep the door open on any attempt to specify "natural" good or a human telos. Indeed, a sort of anti-realism often underpins calls for major social engineering projects. If man has no nature, he can be molded to fit any ideal system (the Baconian mastery/engineering of nature). The popularity of transhumanism with today's oligarchs suggests this sort of thinking might make a comeback.

In particular, I think appeals to reasonableness outside the confines of reason per se tend to actually be relying on a sort of shared tradition and backcloth, a shared moral paradigm. But I think we are seeing such a shared paradigm collapse in real time these days. It's only held up so well because it was around for two millennia and had time to work its way into every aspect of culture and even into our very vocabulary, but other paradigms exist, and there is no reason to think the one undergirding the West will overcome the forces of decay through sheer inertia.

I think what bothers some people is that "true in a context" is seen as some inferior species of being Truly True. It's hard, perhaps, to take on board the idea that context is what allows a sentence to be true at all. If a Truly True sentence is supposed to be one that is uttered without a context, I don't know what that would be.

Well, the idea that 'truth' is primarily a property of sentences appears to be a core step in the path that leads towards deflationism and relativism. I would imagine rejecting this premise itself is more common. Utterances are signs of truth in the intellect, but truth is primarily in the intellect.

We might ask, what is the "context" you refer to? A "game?" A formal system? I would argue that the primary context of truth is the intellect (granted we can speak of secondary contexts). My take would be that analytic philosophy has gravitated towards "truth is a property of sentences," and "justified true belief" precisely because they are analytically tractable and open to more formal solutions. But to my mind, this is a bit like looking for the keys under the streetlight because "that's where the light is." When these assumptions lead to paradox, we get "skeptical solutions" that learn to live with paradox, but I'd be more inclined to challenge the premises that lead to paradox.

I think Borges story the Library of Babel is an excellent vehicle for thinking through the implications of the idea that truth is primarily "in" strings of symbols, although the idea of a truly random text generator that outputs every finite string of text over a long enough time works well too. The fact is that these outputs are never "about" anything from the frame of communications.

To see why meaning cannot be contained within external signals, consider a program that randomly generates any possible 3,000 character page of text. If this program is allowed to run long enough, it will eventually produce every page of this length that will ever be written by a person (plus a vastly larger share of gibberish). Its outputs might include all the pages of a paper on a cure for cancer published in a medical journal in the year 2123, the pages a proof that P ≠ NP, a page accurately listing future winning lottery numbers, etc.¹¹

Would it make sense to mine the outputs of such a program, looking for a cure to cancer? Absolutely not. Not only is such an output unfathomably unlikely, but any paper produced by such a program that appears to be describing a cure for cancers is highly unlikely to actually be useful.

Why? Because there are far more ways to give coherent descriptions of plausible, but ineffective treatments for cancer than there are descriptions of effective treatments, just as there are more ways to arrange the text in this article into gibberish than into English sentences.¹²

The point of our illustration is simply this: in an important sense, the outputs of such a program do not contain semantic information. The outputs of the program can only tell us about the randomization process at work for producing said outputs. Semantic information is constructed by the mind. The many definitions of information based on Shannon’s theory are essentially about physical correlations between outcomes for random variables. The text of War and Peace might have the same semantic content for us, regardless of whether it is produced by a random text generator or by Leo Tolstoy, but the information theoretic and computational processes undergirding either message are entirely different.

A funny thing happens here. The totally random process is always informative. Nothing about past outputs every tells you anything about future ones. It is informative as to outcomes, and wholly uninformative as to prediction. Nothing that comes before dictates what comes after. Whereas the string that simply repeats itself forever is also uninformative, although one always knows what future measurements will be (it is perfectly informative vis-a-vis the future). There is a very Hegelian collapse into oppositional contradiction here, a sort of self-negating. Spencer Brown's Laws of Form have a lot of neat stuff like this too. Big Heg has a funny relationship to electrical engineering :rofl: . -

Are moral systems always futile?

I enjoyed your response, plenty to look up. Can I ask you why you are drawn to medieval philosophy? Not an area I know much about. Feel free to recommend any 'essential' texts, I got a lot out of reading your last one!

Totally by accident. I started with Nietzsche, the existentialists, and post-modern thinkers. I read a decent amount, but wasn't a huge student of philosophy. What got my into philosophy was studying the natural sciences, particularly biology and physics and the role of information theory, complexity studies, and computation in those fields. Most of my early threads on that sort of thing. I was of the opinion that useful philosophy stayed close to the contemporary sciences.

It was through studying information theory and semiotics that I got introduced to Aristotle and the Scholastics. I came to discover that, not only were their ideas applicable to "natural philosophy/science," but they also tied it together with metaphysics, ethics, politics, etc. I had sort of written those other disciplines off as interminable, adopting the popular liberal skepticism towards them (liberalism is very much justified through skepticism and a fear of "fanaticism.")

Unfortunately, medieval thought tends to be quite complex. I don't know if philosophy got to that level of specialization again until the mid-20th century (for better or worse, the printing press really "democratized" and deprofessionalized philosophy of a while). I have become a great admirer of Thomas Aquinas, but it's hard to say where to start with him because it takes a very long time to "get" it and see how it is relevant and applies broadly. I find a lot of the Patristics more accessible, but they tend to be more spiritual, theological, and practical (big focus on asceticism, meditation, and contemplation), and less straightforwardly philosophical and systematic.

One book I really like is Robert M. Wallace's Philosophical Mysticism in Plato, Hegel, and the Present because I think he explains the relationship between reason, self-determination, freedom, happiness, and "being like God," very well. Once one understands that, one can see how Aristotle turned these deep psychological insights into even deeper metaphysical insights. I don't know a great introduction to Aristotle though, although Sachs' commentary on the Physics is very good.

Another one I like is Fr. Robert Sokolowski's The Phenomenology of the Human Person, which does a lot with Husserl, modern philosophy of language, and modern cognitive science, but is grounded in Aristotle and St. Thomas. Jensen's The Human Person: A Beginner's Thomistic Psychology is pretty good too, but still feels a bit "historical." Fr. W. Norris Clarke's The One and the Many: A Contemporary Thomistic Metaphysics is good too, I just feel like I didn't totally get it on the first pass. I got the ideas, but not their power or applicability.

Or, from another direction, Fr. William Harmless has a really good book called Mystics that delves into medieval mystical thought, and he also wrote probably my favorite introduction to the Augustinian corpus Augustine in His Own Words. Pretty sure hard copies are out of print for the former unfortunately though, although you can probably find it online somewhere.

Or, for a third direction, you could start with Dante (which is more fun!). Both the Great Courses and the Modern Scholar have excellent lectures on them (on Audible and elsewhere). Mahfood's commentary is good too, as is Teodolinda Barolini's commentary.. I feel like a close read of the Commedia gets you pretty far into the ethical, political, historical, and even some of the metaphysical dimensions of medieval thought, because Dante was a great synthesizer and weaves it into his narrative. Granted, given its subject matter, it also tends to be heavy on theology.

This might be a dumb question, but how is it a given that moral virtue is an epistemic virtue?

I think the following covers this pretty well. The "rule of reason," in at least some form, is required for good faith inquiry. A person can just write off good faith inquiry from the beginning, but they certainly won't have any good reasons for doing so. The end of the paper I mentioned talks about the anti-realist and their particular objections. Their problem is that they end up like Protagoras, unable to say why philosophy is worthwhile or why anyone should listen to them if they don't already like what they hear.

Knowledge plays an essential role in ethics. It seems obvious that human beings often fail to act morally. Yet just as importantly, we often disagree about moral issues, or are uncertain about what we ought to do. As Plato puts it: “[we have] a hunch that the good is something, but [are] puzzled and cannot adequately grasp just what it is or acquire… stable belief about it.”1 In light of this, it seems clear that we cannot simply assume that whatever we happen to do will be good. At the very least, we cannot know if we are acting morally unless we have some knowledge of what moral action consists in. Indeed, we cannot act with any semblance of rational intent unless we have some way of deciding which acts are choiceworthy.2 Thus, knowledge of the Good seems to be an essential element of living a moral life, regardless of what the Good ultimately reveals itself to be.

Yet consider the sorts of answers we would get if we were to ask a random sample of people “what makes someone a good person?” or “what makes an action just or good?” Likely, we would encounter a great deal of disagreement on these issues. Some would probably even argue that these terms cannot be meaningly defined, or that our question cannot be given anything like an “objective answer.”

Now consider what would happen if instead we asked: “what makes someone a good doctor?” “ a good teacher?” or “ a good scientist?” Here, we are likely to find far more agreement. In part, this has to do with normative measure, the standard by which some technê (art or skill) is judged vis-à-vis an established practice.3 However, the existence of normative measure is not the only factor that makes these questions easier to answer. Being a good doctor, teacher, or scientist requires epistemic virtues, habits or tendencies that enable us to learn and discover the truth. The doctor must learn what is causing an ailment and how it can be treated. The teacher must understand what they are teaching and be able to discover why their students fail to grasp it. For the scientist, her entire career revolves around coming to know the causes of various phenomena—how and why they occur.

When it comes to epistemic virtues, it seems like it is easier for people to agree. What allows someone to uncover the truth? What will be true of all “good learners?” A few things seem obvious. They must have an honest desire to know the truth. Otherwise, they will be satisfied with falsehoods whenever embracing falsehood will allow them to achieve another good that they hold in higher esteem than truth.i For Plato, the person ruled over by reason loves and has an overriding passion for truth.1 Learning also requires that we be able to step back from our current beliefs, examine them with some level of objectivity, and be willing to consider that we might be wrong. Here, the transcendence of rationality is key. It is reason that allows us to transcend current belief and desire, reaching out for what is truly good. As we shall see, this transcendent aspect of reason will also have serious implications for how reason relates to freedom.

Learning and the discovery of truth is often a social endeavor. All scholars build on the work of past thinkers; arts are easier to learn when one has a teacher. We benefit from other’s advice and teaching. Yet, as Plato points out in his sketch of “the tyrannical man” in Book IX of the Republic, a person ruled over by the “lower parts of the soul,” is likely to disregard advice that they find disagreeable, since they are not motivated by a desire for truth.1 Good learners can cooperate, something that generally requires not being ruled over by appetites and emotions. They take time to understand others’ opinions and can consider them without undue bias.

By contrast, consider the doctor who ignores the good advice of a nurse because the nurse lacks his credentials. The doctor is allowing honor — the prerogative of the spirited part of the soul — to get in the way of discovering the truth. Likewise, consider the scientist who falsifies her data in order to support her thesis. She cares more about the honor of being seen to be right than actuallybeing right, or perhaps she is more motivated by book sales, which allow her to satisfy her appetites, than she is in producing good scholarship. It is not enough that reason is merely engaged in learning. Engagement is certainly necessary, as the rational part of the soul is the part responsible for all learning and the employment of knowledge. Yet the rational part of the soul must also rule over the other parts, blocking out inclinations that would hinder the the search for truth.

Prior to reading "After Virtue", I don't think I could have defined 'telos'. How does one land on the premise of a human telos, today? Is it simply moral pragmatism? Is 'excellence' fundamental to the premise of telos?

It could be, but it's normally grounded in the philosophy of nature and metaphysics. -

Reading group: Negative Dialectics by Theodor Adorno

I think Adorno would agree that reason needs to broken free of rigid frameworks, but this is reason's way of correcting itself, not an irrationalist rebellion.

Right, and if you combine this with something like MacIntyre's view of traditions it could be the traditions themselves that are "rigid frameworks," but not necessarily! Calcified historical frameworks can also be the "matter" of such traditions, perhaps even a sort of material sickness frustrating the actualization of form (i.e. the tradition's attainment of rationality), sort of in the way that all animals are different and yet they all strive for life and form, and yet can be frustrated in this by material deficits.

One would be led to this view though only if one actually accepted the adage in PR that "the actual is the rational and the rational is the actual" (Hegel at his more Aristotlelian). -

Reading group: Negative Dialectics by Theodor AdornoThe discussion re keeping particularity and difference in focus came to mind when I came across this G.K. Chesterton quote again recently (from Orthodoxy):

The sun rises every morning. I do not rise every morning, but the variation is due not to my activity, but to my inaction. Now, to put the matter in a popular phrase, it might be true that the sun rises regularly because he never gets tired of rising. His routine might be due, not to a lifelessness, but to a rush of life. The thing I mean can be seen, for instance, in children, when they find some game or joke that they specially enjoy. A child kicks his legs rhythmically through excess, not absence, of life. Because children have abounding vitality, because they are in spirit fierce and free, therefore they want things repeated and unchanged. They always say, “Do it again”; and the grown-up person does it again until he is nearly dead. For grown-up people are not strong enough to exult in monotony. But perhaps God is strong enough to exult in monotony. It is possible that God says every morning, “Do it again” to the sun, and every evening, “Do it again” to the moon. It may not be automatic necessity that makes all daisies alike; it may be that God makes every daisy separately, but has never got tired of making them. It may be that He has the eternal appetite of infancy; for we have sinned and grown old, and our Father is younger than we. The repetition in Nature may not be a mere recurrence; it may be a theatrical encore.

IIRC he is here reflecting on Saint Augustine's reflection re miracles that the rising of the sun is quite miraculous and that if it has only occured once in a generation we would still be talking about it generations later. I thought it was an interesting celebration of sameness in difference, and of repetition as repetition in particulars.

The philosophy of history is interesting in that it is always particular, and yet it is the particular in which all universals are instantiated if they are instantiated at all (e.g. cosmic or natural history), and so represents the individualization of all universals in their larger context. That is, "materialism" is one way to focus on difference and particulars, favoring a sort of "smallism," but one also reaches maximal particularity through a sort of "bigism," the frame of history. -

Positivism in Philosophy

Right, but that's precisely where the conflation can occur. Are things (e.g. cats, trees, clouds, etc.) "in the senses" or are they "projected onto the senses," or "downstream abstractions?" Empiricism has tended to deny the quiddity of things as "unobservable," but a critic might reply that nothing seems more observable than that when one walks through a forest they sees trees and squirrels and not patches of sense data. Indeed, experiencing "patches of sense data without quiddity," is what people report during strokes, after brain damage, or under the influence of high doses of disassociate anesthetics—that is, the experience of the impaired and not the healthy.

But this is obviously going to trickle down across the sciences. Is zoology the study of discrete organic wholes and their natural kinds of is it the study of relatively arbitrary fuzzy "systems?" The entire organization of the special sciences seems to rely on allowing something of quiddities to play a role in defining them. The denial of quiddities plays a pretty large role in a number of classic empiricist arguments that lead to indeterminacy as well.

If empiricism refers just to experience, it starts to cover essentially all philosophy, whereas if it refers to some narrowed down "sense experience" there are still difficulties disambiguating this. The wider definitions of "sense experience" open the door to a very large number of thinkers outside the empirical tradition. Hence, I would say that the "method" has to be expanded to excluding specific sorts of judgements, experiences, and intuitions, which tends to mean supposing some metaphysics to justify such an exclusion.

This sort of goes with Hegel's quip that: "gossip is abstract, my philosophy is not." To already assume that the higher level and intelligible is "more abstract" is to have made a very consequential metaphysical judgement.

Yes, but sadly they became Pragmatists and not Pragmaticists :cool: -

Positivism in Philosophy

That is, if you can show how psychological or economic models (for example) fail to offer consistently, predictable results, then that counts for me as a substantive blow against positivism as opposed to just an analytic attack on the self consistency of the theory.

It seems to me that this would still be consistent with opposing philosophies though, since many of them hardly deny the techniques in question or their potential predictive power. For example, a Neo-Scholastic like C.S. Peirce is hardly denying the usefulness of predictive models and experimentation, he is just asserting a robust metaphysical realism that supposedly augments, makes sense of, and improves this.

The broadly positivist position would be better justified by somehow showing that explorations of metaphysics, or causes in the classical sense, tend to retard scientific, technological, and economic progress, or at least that they add nothing to them. I think this will tend to be difficult though, as a lot of more theoretical work (which tends to be paradigm defining and influential) is also the place where that sort of thing often plays a large role.

Of course, the positivist can also claim that such explorations are only useful because of defective quirks in human psychology. However, this seems like a thesis that it would be extremely hard to justify empirically, although certainly you can "fit the evidence to it." But that's true of a lot of things. -

Positivism in PhilosophyThere is a pretty massive conflation common in this area of thought re "science" and "empiricism." This is pivotal in how different varieties of empiricism often justify themselves. They present themselves as responsible for the scientific and technological revolution that led to the "Great Divergence" between Asia and Europe in the 19th century, and this allows for claims to the effect that a rejection of "empiricism" is a rejection of science and technology, or, in some versions, that empiricism is destined to triumph through a sort of process of natural selection, since it will empower its users through greater technological and economic advances.

But this narrative equivocates on two different usages of "empiricism," one extremely broad, the other extremely narrow. In the broad usage, empiricism covers any philosophy making use of "experience" and any philosophy that suggests the benefits of experimentation and the scientific method. By this definition though, even the backwards Scholastics were "empiricists." Hell, one even sees Aristotle claimed as an empiricist in this sense, or even claims that Plotinus was an empiricist because his thought deals with experience. By contrast, the narrow usage tends to mean something more like positivism, particularly its later evolutions.

I have written about this before, but suffice to say, I think empirical evidence for this connection is actually quite weak. As I wrote earlier:

However, historically, the "new Baconian science," the new mechanistic view of nature, and nominalism pre-date the "Great Divergence" in technological and economic development between the West and India and China by centuries. If the "new science," mechanistic view, and nominalism led to the explosion in technological and economic development, it didn't do it quickly. The supposed effect spread quite rapidly when it finally showed up, but this was long after the initial cause that is asserted to explain it.

Nor was there a similar "great divergence," in technological progress between areas dominated by rationalism as opposed to empiricism within the West itself. Nor does it seem that refusing to embrace the empiricist tradition's epistemology and (anti)metaphysics has stopped people from becoming influential scientific figures or inventors. I do think there is obviously some sort of connection between the "new science" and the methods used for technological development, but I don't think it's nearly as straightforward as the empiricist version of their own "Whig history" likes to think.

In particular, I think one could argue that technology progressed in spite of (and was hampered by) materialism. Some of the paradigm shifting insights of information theory and complexity studies didn't require digital computers to come about, rather they had been precluded (held up) by the dominant metaphysics (and indeed the people who kicked off these revolutions faced a lot of persecution for this reason).

By its own standards, if empiricism wants to justify itself, it should do so through something like a peer reviewed study showing that holding to logical positivism, eliminativism, or some similar view, tends to make people more successful scientists or inventors. The tradition should remain skeptical of its own "scientific merits" until this evidence is produced, right? :joke:

I suppose it doesn't much matter because it seems like the endgame of the empiricist tradition has bifurcated into two main streams. One denies that much of anything can be known, or that knowledge in anything like the traditional sense even exists (and yet it holds on to the epistemic assumptions that lead to this conclusion!) and the other embraces behaviorism/eliminativism, a sort of extreme commitment to materialist scientism, that tends towards a sort of anti-philosophy where philosophies are themselves just information patterns undergoing natural selection. The latter tends to collapse into the former due to extreme nominalism though.

I suppose I should qualify that though in that there seems to be a third, "common sense" approach that brackets out any systematic thinking and focuses on particular areas of philosophy, particularly in the sciences, and a lot of interesting work is done here. -

What is real? How do we know what is real?

Pluralism, as I understand it, allows different epistemological perspectives, with different conceptions of what is true within those perspectives.

This just seems like relativism though, as in "what is true is relative to systems that theoretical reason (truth) cannot decide between." Here is why I think this:

Either different epistemic positions contradict each other or they don't.

If they don't, then they all agree even if they approach things differently.

Whereas, if there can be different epistemological perspectives that contradict one another and they are equally true (or not-true, depending on which perspective we take up?) then what determines which perspective we take up then? Surely not truth, theoretical reason, since now the truth sought by theoretical reason is itself dependent on the perspectives themselves (which can contradict each other).

If we appeal to "usefulness" here, it seems we are appealing to practical reason. But there is generally a convertability between the practical and theoretical, such that practical reason tells us what is "truly good." Yet this cannot be the case here, since the truth about goodness varies by system. Hence, "usefulness" faces the same difficulty.

Dialtheist logics normally justify themselves in very particular ways, e.g. through paradoxes of self-reference. So their scope is limited to rare instances with something like a "truth-glut." We might find these cases interesting, and still think they can be resolved, perhaps through a consideration of material logic and concrete reasons for why some alternative system is appropriate for these specific outliers. But this isn't the same thing as allowing for different epistemologies and so different truths.

The straightforward denial of truth, e.g. moral anti-realism, actually seems less pernicious to me here. Reason simply doesn't apply to some wide domain (e.g. ethics), as opposed to applying sometimes, but unclearly and vaguely.

It also encourages discussion between perspectives, including how conceptions of truth may or may not converge.

And a denial of contradiction doesn't? Why? Does denying contradiction or having faith in the unity of reason require declaring oneself infallible?

You could frame it the opposite way just as easily. Because in relativism one need not worry about apparent contradiction, one need not keep at apparent paradoxes looking for solutions. Nor does one need to fear that opposing positions might prove one wrong. One can be right even if one is shown to be wrong, and so we can rest content in our beliefs. As reason becomes a matter of something akin to "taste" it arguably becomes easier to dismiss opposing positions out of hand.

This at least comports with common experiences in the fields where relativism has become dominant, where students and professors report frequent self-censorship and "struggle session" events within the context of an ideology that nonetheless promotes a plurality of equality valid epistemologies and "ways of knowing." Marxism is in decline, but this is also still an area where "history" (power) is often appealed to as the final authority ("being on the right side of history").

Relativism (about truth) would deny even this perspectival account as incoherent. (A very broad-brush picture of a hugely complicated subject, of course.)

IDK, this seems like how most relativism re truth is framed (as opposed to from anti-realism, which is the common framing for ethics). -

What is real? How do we know what is real?

I was just thinking of more straightforward examples, like if we had never seen an animal, nor any picture or drawing, it could still be described to us. Or, had we never seen a volcano erupt, it could still be explained in terms of comparisons to fire, etc. I just wanted to head off the counter that we don't always need sense experience to competently speak of things. No one has ever seen a phoenix, but we can learn to speak of them too.

This works because you can use comparisons, analogy, composition and division, etc. But some prior exposure to things is necessary. It can't just be linguistic signs and their meanings (it could be just signs, if you take light interacting with the eye, etc. as a sign).

The causal priority of things is needed to explain why speech and stipulated signs are one way and not any other. If one wants to say that act of knowing water and knowing 'water' are co-constituting, one still needs the prior being of water to explain why knowing water and 'water' is not the same thing as knowing fire and 'fire' or why, if 'water' was used for fire, that would involve knowing a different thing with the same stipulated sign.

Actually, I see this later point has come up here ( ; ).

No doubt, how we act vis-á-vis fire would be different from how we act vis-á-vis water, even if we called fire 'water,' but this action, and the "usefulness" driving it, doesn't spring from the aether uncaused, but has to do with differences between fire and water.

I am a big fan of some thinkers who put a heavy focus on language here, such as Sokolowski or parts of Gadamer, but I also think it's precisely philosophers of language who are apt to make claims like: "that which can be understood is language." Would a mechanic tend to make the same claim? Is understanding how to fix a blown head gasket primarily a manner of language? Or throwing a good knuckleball? What are the limits of knowing for people with aphasia who can no longer produce or understand language (or both)? I think that's a difficulty with co-constitution narratives as well. They tend to make language completely sui generis, and then it must become all encompassing because it is disconnected from the rest of being. I think it makes more sense to situate the linguistic sign relationship within the larger categories of signs.

What is it the critic wants to conclude - that our use of the word is grounded in a pre-linguistic understanding of what water is? Perhaps we learn to drink and wash before we learn to speak. But learning to drink and wash is itself learning what water is. There is no neat pre-linguistic concept standing behind the word, only the way we interact with water as embodied beings embedded in and interacting with the world. Our interaction with water is our understanding of wate

This just might be an misunderstanding. Some pre-linguistic understanding of water might well exist (indeed, this seems clear in babies), but that's not really the issue. The point is that water exists, has determinant being/actuality, prior to being interacted with by man. Otherwise, we wouldn't interact with water any differently than we would fire, except through the accidents of co-constitution. But co-constitution that is one way, instead of any other (e.g. water for washing, fire for cooking) presupposes that there are prior, determinant properties of both. There would be no reason for us to interact with any one thing differently from any other if this weren't the case. "Act follows on being."

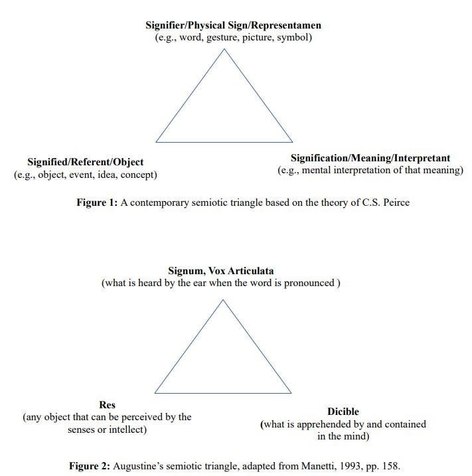

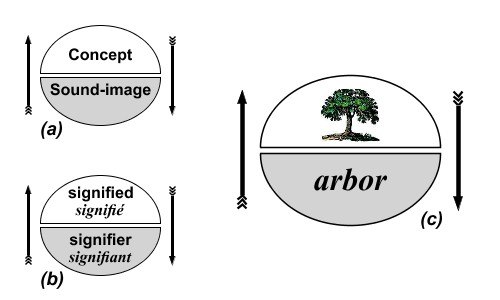

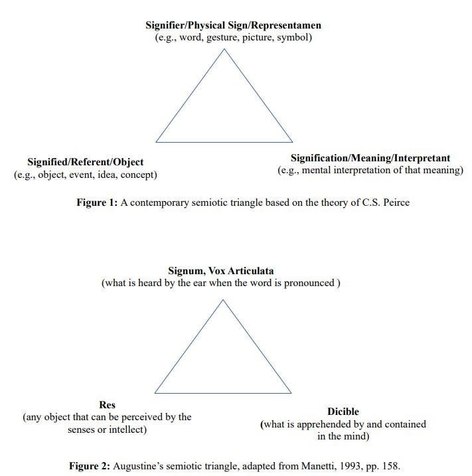

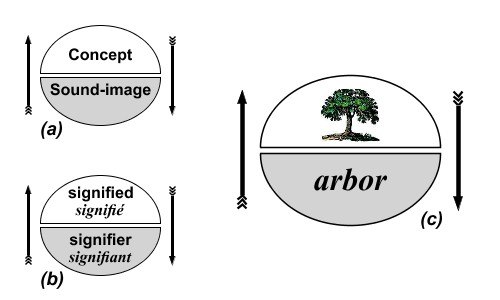

So on one hand we have a triadic {water – concept-of-water – use of water}; on the other just water being used.

This is misunderstanding the triadic sign relation. The sign vehicle could be the "concept of water" in some relation, but in general it will be the interpretant.

A basic relation in sight would be:

Object: water

Sign vehicle: light waves bouncing off water and to the eye

Interpretant: person

But light only reflects of water differently than a tree because the two are already determinantly different. The difference doesn't come after the fact. Co-constitution theories have difficulty with this because they often lack a notion of essences/essential properties (or a strong one) and so they are left with the problem that whenever something is known differently it has seemingly changed and become a new thing. -

What is real? How do we know what is real?

You and Tim objecting to formal modal logic robs you both of the opportunity to present your arguments clearly.

I objected to the weak modal formulation of essences, that's hardly the same thing. But yes, there are also other ways to conceive of modality as well. For someone who argues that formalisms are merely tools selected for based on usefulness, you sure do like to appeal to them a lot as sources of authority and arbiters of metaphysics a lot though.

What was "Banno 's Principle? "It is easier to disagree with something if you start out by misunderstanding it." A bit rich coming from someone who frequently wants to post about "Aristotelian essence" and "Aristotelian logic," but seems to be unwilling to read about the basics of either.

The suggestion that formal logic is restricted to analytic philosophy is demonstrably ridiculous

:roll:

What should I do? Is it OK for me to just shoot you, in order to eliminate dissent? Should I do what the One True Explanation of Everything demands, even if that leads to abomination?

:roll:

Slow down, you're going to run out of straw over there. I suppose if you think that "the truly best way to do things" involves shooting dissenters that says more about you.

Funny, how here we are now moving over to the ideas entertained in the thread on Faith. I wonder why.

Hey, we made it 15 pages before the "Banno starts bringing up the religion of everyone who disagrees with him" bigotry phase of the thread. I'd say that's pretty good. -

What is real? How do we know what is real?

You know, those basic liberal virtues. How much worse would a world be in which only the One True Explanation Of Everything was acceptable, uncriticised?

I assume the unstated premises here are that the "One True Explanation of Everything" isn't really true and is only not criticized out of force, otherwise, it sounds like a world that would be immeasurably better—a world free from error and ignorance and in harmony.

I mean, what's the assumption here otherwise, that there would be a One True Explanation that was demonstrably true, and yet it would be bad if people didn't criticize it and demand error over truth and the worse over the better? (The old elevation of potency as "freedom" I suppose).

Pluralists can accept many truths within different practices - physics, literature, religion, without affirming logical contradictions. But this doesn’t mean that "2+2=5" and "2+2=4" are both true. Pluralism has limits, governed by coherence, utility, and discursive standards.

I think this a much more wholesome response than supposing that some amongst us have access to the One True Explanation and the One True Logic.

Yes, it's the bolded that seems to lead to the problems described here. You keep setting infallibilism and "absolute knowledge" up in a dichotomy with a pluralism based on utility, but this is a false dichotomy. Most fallibilists are not relativists. All that is required is a faith in reason (i.e. not misology) not "knowing everything."

From the thread:

Misology is not best expressed in the radical skeptic, who questions the ability of reason to comprehend or explain anything. For in throwing up their arguments against reason they grant it an explicit sort of authority. Rather, misology is best exhibited in the demotion of reason to a lower sort of "tool," one that must be used with other, higher goals/metrics in mind. The radical skeptic leaves reason alone, abandons it. According to Schindler, the misolog "ruins reason."

If we return to our caricatures we will find that neither seems to fully reject reason. The fundamentalist will make use of modern medical treatments and accept medical explanations, except where they have decided that dogma must trump reason. Likewise, our radical student might be more than happy to invoke statistics and reasoned argument in positioning their opposition to some right wing effort curb social welfare spending.

Where reason cannot be trusted, where dogma, or rather power relations or pragmatism must reign over it, is determined by needs, desires, aesthetic sentiment, etc. A good argument is good justification for belief/action... except when it isn't, when it can be dismissed on non-rational grounds.In this way, identity, power, etc. can come to trump argument. What decides when reason can be dismissed? In misology, it certainly isn't reason itself.

-

What is real? How do we know what is real?

In that sense, our version of reality or truth functions similarly to how language works; it doesn’t have a grounding outside of our shared conventions and practices.

I guess I probably wouldn't agree with the ideas behind this, so that might be a difference.

The position isn’t that truth is mere popularity, but that truth is built through ongoing conversation and agreement. What counts as true is what survives criticism, investigation, and revision within a community over time. So instead of certainty, we have a fallible and evolving consensus. Tradition, in such a context, is something that should be investigated and revised if necessary.

Right, I have no problems with fallibilism and a circular epistemology. A certain sort of fallibilism seems necessary to defuse the idea that one most know everything to know anything.

But I also don't think it's helpful to conflate a rejection of relativism with a positive assertion of foundationalism and infallibilism, which I seem to recall Rorty doing at times. Precisely because one need not know everything to know anything, it does not seem necessary to have an "ultimate" or "One True" in sight to make judgements. Rorty sounds sensible to me sometimes, but then there is stuff like the idea that a skrewdriver itself, its properties, recommends nothing to us about its use, that strike me as obviously wrong.

Anyhow, those all seem to me like points related to fallibilism and foundationalism. But with

Humans work to create better ways to live together,

We settle, at least for a while, on what works

having conversations about improvement,

In a relativism based on anti-realism (which I'm aware no one in this thread has suggested) there is simply no fact of the matter about these criteria you've mentioned. Nothing "works better" than anything else. So, we can debate in terms of "what works," or "is good," but, per the old emotivist maxim, "this is good" just means "hoorah for this!" That seems to me to still reduce to power relations.

In a relativism where truth about "what works" and "better" changes with social context (where there is no human telos), where "we decide" (as individuals or as a community), none of those claims about "what works" or "what constitutes improvement" is grounded in any sort of underlying "goodness" or "working" that is separate from current belief and desire. That is, there is nothing outside the "playing field" of power politics. Rather, if something "truly works" or is "truly good," depends on what people are driven towards at the moment.

This certainly still seems to me to be very open to a reduction towards power. Truth as "justification within a society," for instance, seems obviously open to becoming a power struggle. One can just look at real life examples from totalitarian societies or a limit case in fiction like 1984 and "A Brave New World." "A Brave New World" is probably the more difficult case because it's obviously a case with a tremendous amount of manipulation, yet one where people are positively inclined towards the system, and even their own manipulation.

Now, I am all for the idea that the human good is always filtered through some particular culture or historical moment, and that this will change its general "shape." It's the denial of any prior form to this good that I think sets up the devolution into power politics. Likewise, human knowledge is always filtered through a particular culture and historical moment. Yet there are things that are prior to any culture or historical moment, and which thus determine the shape of human knowledge in all cultures and historical moments. The being of an ant or tiger for instance, is prior to culture, as its own organic whole, and so there is a truth to it that is filtered through culture, but not dependent upon it.

Edit: the other thing with him (and a lot of other relativistic arguments) is the heavy reliance on debunking. But debunking only works if we have a true dichotomy such that showing ~A is equivalent with showing B. I guess to the early topic of skeptical and straight solutions, it seems to me like a lot of skeptical solutions likewise rely on debunking heavily. -

What is real? How do we know what is real?

I think you'd see, rereading, that this isn't accurate.

How so? I'm genuinely confused here? What exactly would be your explanation of why relativism and pluralism re truth is wrong?

A thorny issue. I suppose one's understanding of signs is important here, as well as the proper ordering of the sciences/philosophy (if one is supposed at all).

If metaphysics has priority, we can say that water has to be before it is known. The being, its actuality, is called in to explain the sign and evolutions in what the sign evokes

But the role of the object is collapsed with that of the interpretant in the Sausserean model that has so much influence on post-structuralism, and that paints a different picture.

And the difference between these two models lies in the question: in the second model, what is signified: the object, or an interpretation called forth by the sign (the meaning)? That seems to be the essence of the question here to me.

It would be question begging to simply assume the prior model of course, but I think one can argue to it on a number of grounds.

First, a system of signs that only ever refers to other signs would seem to be, in information theoretic terms, about nothing but those signs. This would be the idea, rarely explicitly endorsed, but sometimes implied, that books about botany aren't about plants, but are rather about words, pictures, and models, or that one primarily learns about models, mathematics, and words when one studies physics. There is also the question of the phenomenological content associated with signs. Where would that come from?

Second is the old question: "why these signs (with their content)?" This is the old question of quiddity that Aristotle is primarily interested in. Then also, "since these appear to be contingent, why do these signs exist at all?" (the expanded question of Avicenna and Aquinas). Which is, to my mind, a question of how potential is made actual.

Yes, in a way, but I think reality comes first. I think we have to have some familiarity with water before we have any sensible familiarity with "water."

I agree as a rule, although the tricky thing is that one might indeed become familiar with something first through signs that refer to some other thing. We can learn about things through references to what is similar, including through abstract references. Likewise, we can compose, divide, and concatenate from past experience and share this with others so that what we are talking about refers to no prior extra-mental actuality (at least not in any direct sense).

But this cannot be the case for everything, else it would seem that our words would have no content. Our speech would be a sort of empty rule following, akin to the Chinese Room.

Mary the Color Scientist can know so much about color because she has been exposed to the rest of the world, just sans color. But if she had no experiences at all, it's hard to see how she could "know" much of anything.

Now I suppose this doesn't require some prior actuality behind sense experience and signs. They could move themselves. It's just that if they did move themselves there wouldn't be any explanation for why they do so one way and not any other. -

RIP Alasdair MacIntyre

He is definitely worth checking out. After Virtue is the classic for a reason but I actually think folks who don't agree with After Virtue might find his later stuff (particularly "Whose Rationality?") more fruitful. His background in Marxism (and thus Hegel), as well as Nietzsche, gives him a historicism at odds with a lot of Thomism. He makes an argument that "rationality" is always embedded in tradition and that tradition is a means of knowing/being rational.

In some ways, he builds on the post-modern theorists, who he is in dialogue with (particularly Foucault). However, he remains a critic of modernity here. He points out that the Enlightenment, liberal tradition is self-undermining, and this is precisely why it has bottomed out in relativism and perspectivism and has such a deep problem with a "slide towards multiplicity." He then goes about defending his preferred tradition as a tradition (as opposed to denying it is one).

Interesting stuff, although I might modify bits of it. It seems to me that reason can be broader, more truly catholic (always relating to the whole and so always bringing itself beyond itself) and still always filtered through some particular tradition. This is perhaps a sort of form/individuating matter distinction we could make. Tradition unfolds in history according to reason, as one of its particular modes. But it can also attain this form more or less well, in the same way an animal can be healthy or sick. (For those of us Solovyev fans, perhaps this can even be the Providential unfolding towards theosis.) Modernity is sick because the Enlightenment has built in contradictions (and arguably has kept sublating new contradictions as it consumed nationalism and socialism through competition).

This element of his thought is what makes it particularly annoying to see MacIntyre occasionally lumped in with strawman of critiques of modernity that declare that they amount to simply asserting the superiority of antiquity of the middle ages, and must involve a denial of women's rights, technology, etc. At least Weaver brings this sort of response on himself (and does say some rather churlish things). Or even Schindler, who is perhaps a deeper thinker, still is partly responsible for being taken this way due to his polemical style and adages like "liberalism is the from of evil in the modern world." MacIntyre always struck me as more subtle and diplomatic, with something for most people to like. -

What is real? How do we know what is real?

I am not a relativist about truth

No? And yet to the question of where relativism applies you say that this itself is subject to relativism.

Of course, so much so that I'd hesitate to talk about "truths" here at all. Or maybe I don't understand what a non-context-dependent truth about a philosophy would be.

Presuming that philosophy includes epistemology, ethics, metaphysics, logic, and natural philosophy/the philosophy of the special sciences, this would mean that there are no non-relativized, pluralized truths vis-á-vis most of human knowledge though, no?

But the very claim that the truths of philosophy are relative is a (presumably non-context-dependent and potentially contradictory?) claim about metaphysics and knowledge.

At any rate, I'm curious, if one is not a relativist, but assumes that there aren't truths about epistemology, metaphysics, logic, or ethics, how does one go about demonstrating the relativism is not correct? What would be your counterargument to the relativist?

I'm assuming there is some misunderstanding here because it seems to me obviously impossible to accept that there are no non-pluralized truths about philosophy generally and to move from this to an anti-relativist stance, particularly if we have also affirmed that the question of whether or not any topic is relativistic or not is itself relativistic.

What is the argument against relativism given these starting premises?

Nor do I think that acknowledging "pluralistic, context-dependent truths" makes someone a relativist.

I agree here. The truth of: "it is raining," is context dependent for example. However, if one expands pluralism to the whole of logic, epistemology, metaphysics, ethics, and the philosophy of nature, or if the justification of logic and predication rests on "we decide" I cannot see how a fairly all-encompassing relativism wouldn't be the result. -

What is real? How do we know what is real?

Distinctions between our intuitions about the real, actual, existing, etc. are the bread and butter of metaphysics. Indeed, words like actual, virtual, essential, substance, form, information, idea, being, potency, existence, etc. come from this tradition, which influenced the development of English.

Of course, it's unhelpful to make vague distinctions. But that's not generally what metaphysics does (at least, there is some attempt at clarification). When people refer to the "common sense" meanings of such terms, they are sort of appealing to the residue of millennia of metaphysical and theological speculation. It is also unhelpful to use the same terms in different ways, and metaphysics often does this. It does this precisely because it is always striving to make these terms more definite. I would say that historically, the terms are vague precisely because so many people have tried to clarify them in different ways.

Formalism is one way to try to clarify terms. But a difficulty here is that not all explanations and understandings are equally easy to formalize. Hegel's dialectic couldn't be formalized until the 1980s with major advances in mathematics, particularly category theory. Analogical predication, the a core feature of classical metaphysics, has yet to be convincingly formalized. Indeed, arguably logic is rightly the domain of univocal predication alone.

Certainly, discussions of logic and the form of arguments and discourse can inform metaphysics. But I think the influence tends to go more in the other direction. Metaphysics informs logic (material and formal) and informs the development of formalisms. This can make pointing to formalisms circular if they are used to justify a metaphysical position. -

RIP Alasdair MacIntyreThe last of an era. Almost, Charles Taylor is still alive.

He certainly has an interesting thesis in After Virtue. Arguably, the "apocalypse" thesis can be applied to a much wider area than ethics alone, really to our entire metaphysical vocabulary re substance, essence, causes, etc.

That'd be my pet radical claim. The move to "modernity," including what MacIntyre looks into in ethics, is defined by the elevation of potency over actuality (often in terms of potency as "freedom"). And if one says: "hey now, my preferred modern area thought doesn't even have a clear conception of actuality or potency," or "but potency is covered differently in each system these days," my response will be "exactly!" QED. :cool: -

What is real? How do we know what is real?

Subject to certain purposes, you might say.

And these are true measures of usefulness, or only "useful" measures for usefulness? The problem is that this seems to head towards an infinite regress. Something is "useful" according to some "pragmatic metric," which is itself only a "good metric" for determining "usefulness" according to some other pragmatically selected metric. It has to stop somewhere, generally in power, popularity contests, tradition, or sheer "IDK, I just prefer it."

So:

what we can point to is broad agreement,

So popularity makes something true? Truth is like democracy?

shared standards

Tradition makes something true?

and better or worse outcomes within a community or set of practices.

Better or worse according to who? Truly better or worse?

I hope you can see why I don't think this gets us past "everything is politics and power relations." I think Nietzsche was spot on as a diagnostician for where this sort of thing heads.

Well, either there is a truth about which truths are "pluralistic, context-dependent truths" or there isn't, right? Is "which truths are pluralistic, context-dependent truths?" a question for which the answers are themselves "pluralistic, context-dependent truths?"

To be sure, if one starts throwing around all sorts of capitalized concepts without explaining them, they will be confusing. I would generally assume that when someone asks a pluralist re truth about what is "really true," though, they are asking about the existence of truths that are not ultimately dependent on what some individual or community currently considers to be useful or true.

The mistake comes when we think we've consulted the Philosophical Dictionary in the Sky and discovered what is Really Real.

A "mistake." Are you saying it would be wrong to affirm this? Curious. Would this be another of those "non-serious" philosophies that we can dismiss? But let me ask, are they "truly non-serious,' or would truths about which philosophies are "wrong," "mistakes," or "unserious" be "pluralistic, context-dependent truths?"

Second, what separates a pluralism that sees assertions of non-pluralism as mistakes from the "crude pluralism" discussed earlier? The problems of the "unity of dogmatism and relativism," the way their reinforce one another, do not seem resolved here. -

What is real? How do we know what is real?

What I got from @Banno seems to be that pluralistic or context-based truths don’t mean that every contradiction is true. Instead, truths depend on the situation, purpose, or point of view.[/quote

Of course. Just the ones that are useful to affirm are "true"... and "false." Maybe neither too. Perhaps in the interest of greater tolerance we shall proclaim in this case that there both is and is-not a One True Truth (TM)?

But that doesn't really seem to work. To say "is" and "is-not" here is really just to deny "is." Yet can it be "wrong" to affirm the "One True Truth" in this case?

When contradictions happen, it usually means they come from different ways of looking at things -not that truth doesn’t exist

Why not just: "there are different ways of describing the same thing that might be equally correct. Some might be more useful in some situations. And some might appear to contradict each other if one is not careful with one's distinctions, simplifying assumptions, definitions, clarifications, etc." as opposed to the idea that something can be both true and not-true depending on what is useful?

I imagine you’re unlikely to be a Rorty fan, but didn’t he say that truth is not about getting closer to some metaphysical reality; it’s about what vocabularies and beliefs serve us best at a given time?

Yes, is what Rorty says true? I know Rorty says it is "more useful." Is it truly more useful? I would deny it. But there are either facts about what is "truly more useful" or there aren't. If there aren't, and we are both just asserting sentiment, then won't this just becomes a power struggle? (I like my chances against Rorty since I still have a heart beat).

Well it may well be useful for one's survival to accept that Big Brother is right, so at one level (that of ruthless pragmatism) sure. But being compelled to believe something out of fear of jail or death is a different matter altogether, isn't it?

Yes, but if you're the one doing the "compelling" it can be plenty "useful" right? Truth becoming a power relation doesn't ensure that you always win the power game. -

Which is the bigger threat: Nominalism or Realism?

Have you finished Olesky's book? I have not made it all the way through, but I think his exact objections are covered in depth (that's at least what the introduction and chapter summaries suggest, I only got through the discussion on Scotus and Ockham).

Lots of thinkers have called nominalism "diabolical" or demonic though. There is a history here. It's not just that they think they are "bad ideas." Something akin to nominalism shows up at the very outset of Western philosophy, but never gets much traction. By late antiquity, it is all but gone.

A lot of philosophy in this later period (late-antiquity to the late medieval period) is focused on self-cultivation, ethics, excellence, and "being like God." "Being like God" was the explicit goal of late-antique philosophical and monastic education in many surviving guides (even the biographies of Pagan sages paint them as "saints"). Here, reason plays an essential role in self-determination, freedom, the transcending of human finitude, and ultimately "being more like God." Reason itself also has a strong erotic and transformative element. This is a theme in Pagan, Christian, Islamic, and even Jewish thought to varying degrees.

Hume's formulation that "reason is, and ought only be, a slave of the passions," and his general outlook on reason (wholly discursive and non-erotic), hedonism, and nominalism/knowledge, very closely parallels what the old sages describe as the paradigmatic state of spiritual sickness (e.g. "slavery in sin"). The Philokalia, for instance, describes this sort of perception/experience of being in terms of "what can I use this for to meet my desires" (i.e., the Baconian view of nature) as the "demonic" mode of experience. That is, they consider something like utilitarianism (Mill mentions Bentham), and decide that this is how one thinks in the grips of demonic fantasy (for a whole host of complex reasons). The state of Hume's ideal, which is for him insulated from dangerous "fanaticism" and "enthusiasm," is in some ways pretty much a description of the state of the damned in Dante's Hell.

Nominalism also tends towards the "diabolical" in the term's original sense (where it is opposed to the "symbolical"). It will tend to focus on multiplicity and division. But the "slide towards multiplicity/potency/matter" is the very definition of evil in classical thought. Evil is privation, and matter is, ultimately, privation on its own.

The "pragmatic" (and so generally volanturist) recommendations of a number of nominalist thinkers line up pretty well with what Pagan and Christian thinkers thought was the state of a soul "enslaved by the passions and appetites," with a corrupt and malfunctioning nous. It's an orientation towards a hunger that turns out to be a sort of self-consuming, self-negating nothingness (the Satanocentrism of Dante's material cosmos, or perhaps R. Scott Bakker's image of Hell as inchoate sheer appetite, and the consumption of the other, and thus total frustration of Eros-as-union—or Byung-Chul Han's "Inferno of the Same" recommend themselves as images here).

The idea is not that only nominalists, or specifically nominalists are uniquely "evil." A realist might easily allow that it is better to be led by a virtuous nominalist liberal than by a vice-addled realist. A liberal nominalist society might be organized more virtuously than a corrupt realist one (e.g. the Papacy of Dante's time).

The point is more about how nominalism will make it impossible to identify virtue as virtue and vice as vice in the long run. Indeed, that is, I would imagine, a big motivation for the polemics, the idea that broad currents in modern thought slowly make vice into a virtue. I think there is a strong case for this re pleonexia (acquisitiveness) in capitalism.

And I think this is how you get forceful takes like Weaver's:

Like Macbeth, Western man made an evil decision, which has become the efficient and final cause of other evil decisions. Have we forgotten our encounter with the witches on the heath? It occurred in the late fourteenth century, and what the witches said to the protagonist of this drama was that man could realize himself more fully if he would only abandon his belief in the existence of transcendentals. The powers of darkness were working subtly, as always, and they couched this proposition in the seemingly innocent form of an attack upon universals. The defeat of logical realism in the great medieval debate was the crucial event in the history of Western culture; from this flowed those acts which issue now in modern decadence.

By contrast, the modern tends to approach philosophy more like Hume on average than a Plotinus or an Origen. At the end of the day, you kick back from it and play billiards. It's not that serious. Daoism appeals more to some people, nominalist pragmatism to others, realism to still others, etc. It is, in some sense, a matter of taste.

So, when some raving realist says: "don't drink that, it's poison!" the response is likely to be: "well that's quite rude to call it poison. I quite like it." But of course the response here assumes that "poison" is uttered as a matter of taste. The realist thinks they have good reason to think it is really poison. It's a fundamental disconnect. This is why nominalist rebuttals will tend to be less organized.

This is all speaking in very broad terms of course. I am just speaking to the broad pitch of the rhetoric and where it seems to have its history. Nominalism, volanturism, and the elevation of potency over actuality are anathema to broad swaths of the history of Western thought, but the elevation of desire also puts it in conflict with a lot of Eastern thought (which is why the latter has become a popular alternative). -

What is real? How do we know what is real?

IS there some conclusion that you would like to draw from all this?

Yes, that the one sentence explanation of essences you've offered is metaphysically insubstantial (which was @Wayfarer's point in the other thread). Now, there are attempts to use this basic conceptual machinery to develop a more robust notion of essence. The point made in the articles referenced earlier is that the machinery itself is perhaps inadequate for this task (or perhaps requires modification). It's hard to start with a system designed with nominalist presuppositions and work one's way back to essences, perhaps impossible.

In particular, if it leaves open the possibility that "essential" is only predicated of things accidentally, it is not even really a theory of essences in anything like the classical sense, more a method of stipulation that could be developed into a workable theory of essences. -

What is faith

I agree whole-heartedly that the notion that one has grasped an Absolute Truth is extremely dangerous. It makes it impossible to acknowledge and tolerate any disagreement. I cannot think of a situation in which this might be a a Good Thing, but I can think of many in which it is clearly a Bad Thing.

What about propositions such as: "other groups of humans should not be enslaved?" or "all humans deserve dignity and some groups are not 'subhuman?" Or "one ought not molest children?"

Are these extremely dangerous absolutes we should be open to reconsidering?

At any rate, what you're saying clearly can't be "Absolutely True," itself, right? :wink: -

What is real? How do we know what is real?

So if "One Truth" (I guess I will start capitalizing it too) is "unhelpful," does that mean we affirm mutually contradictory truths based on what is "useful" at the time?

Or, if not, if truth does not contradict truth, then it seems to me that we still have "one" truth and not a plurality of sui generis "truths" (plural).

As I mentioned earlier, a difficulty with social "usefulness" being the ground of truth is that usefulness is itself shaped by current power relations. It is not "useful" to contradict the Party in 1984 (the same being true in Stalin's Soviet Union or North Korea). Does this mean "Big Brother is always right,' because everyone in society has been engineered towards agreeing? Because this has become useful to affirm? -

How do we recognize a memory?

There are indeed a lot of different "types of memory," and perhaps "faculties" involved in different sorts. I figure episodic memory is what we're focused on here, although this same thing also applies to crystalized knowledge recall too (i.e. that we can tell facts we have made up, fictions, and lies, from facts that we think we genuinely know).

My favorite book on this sort of thing is Sokolowski's "The Phenomenology of the Human Person." He talks a lot about imagination. In imagining, we can either self-insert or imagine in a "third person" way. One does not have "third person" episodic memories, but this doesn't seem like the key differences.

Obviously, they are phenomenologicaly distinct, and it would be problematic if they weren't. Pace some of the much (over) hyped studies on prompting "false memories," these only really work in vague cases. You might be able to get someone to misremember being lost in the mall when they were three, but you're not going to prompt them into thinking they went to college when they didn't, etc.

I might instead look for the difference chiefly in them being physically/metaphysically distinct actually. When considering the formation of a memory, we are talking about the senses, memory, and intellect being informed by some external actuality. Whereas, with imagination, we are dividing and composing stored forms. The two processes look quite different from a purely physical standpoint (although the same areas of the brain get used for imagining, perception, and memory, but to different degrees).

It would make sense that an actual stimulus would tend to leave a deeper impression than a virtual/synthetic one, and that we would indeed have an anatomy that structures this sort of difference into our experience, since an inability to keep imaginings and memories straight would be very deleterious for human life. Although, if consciousness is purely an epiphenomenon, there actually wouldn't be any benefit to memory and imagination being phenomenologicaly distinct (another mystery of psycho-physical harmony).

If I were building an android for instance, I would "tag" real versus synthetic experiences so as to keep them distinct during recall to avoid accidents like looking for food that never existed, etc. -

What is faith

More and more it's the extended family/(intentional) community, at least in the ideal case (for religious intellectuals).

But it's not like the alternatives don't enforce power dynamics. The power dynamic in more self-consciously "progressive" thought just tends to be the exceptional individual destroying other power relations so as to increase individual freedom on behalf of the "masses" (a move favoring the exceptional individual most of course), and then the (progressive) state stepping in to remove friction between individuals and to correct various "market failures."

However, since individuals liberated from culture (particularly exceptional ones) tend to have a lot of friction, and because markets fail a lot and entrench, rather than revalue existing disparities, the state (and activist) has to do a lot of intervention and reeducation. Hence, they need to have a lot of power. -

What is faith

Isn't your take informed by a bias that values traditionalism and is suspicious, perhaps even hostile towards political radicalism (particularly of the Left)? Is your use of irony as Rorty uses it? Is 'unseriousness' how they would describe it, or is that your description for it? There's a further quesion in what counts as a politically radical circle?

The constant use of irony and humor is sort of a defining feature of the Alt-Right and something they are self-consciously aware of. It's why their biggest voices, and now the presidential administration itself, often advances ideas through vague but provocative "funny" memes. E.g., Trump as the new Pope, joke memes about deportations, etc.

Tucker Carlson fit this mold quite well (who does the two minutes hate better?). He also fits the mold of the sarcastic "exceptional individual who sees through through all the bullshit" (the audience being implicitly one as well, a style incredibly popular since at least Nietzsche).

I wouldn't put this on the left in particular. If anything it is bigger for aspects of the right. The entire Manosphere ideology would seem to make meaningful romantic relationships impossible. Everything is transactional and defined in an economic calculus defined by evolutionary psychology, with catchphrases like "alpha seed and beta need" or "alpha fucks and beta is for the bucks." One cannot "fall in love" without risking becoming a sucker and a "cuck." But the obsession with being "cuckolded" goes beyond romance, and expands to all realms of social life. Hence, one must "keep it real," which means being a strong willed egoistic utility maximizer with one's gaze firmly on those goods which diminish when shared so as to "get one's share."

Simone de Beauvoir's analysis of gender relationships in terms of Hegel's Lord-Bondsman dialectic is spot on here. The "pick up artist" craves female validation (sex being one of the last goods to be commodified) but makes woman incapable of giving him recognition because he has denigrated her into a being lacking in dignity.

Likewise, the right-wing fixation on warrior culture, war, and apocalypse, which seems akin to 1914 in many ways, is a desire for war precisely because "nothing matters/is serious." It's the desire for war, apocalypse, crisis, etc. precisely because of this sort of spiritual constipation and the fear of degenerating into Nietzche's "Last Men," i.e. into the "consumers / workers" they are so likely to be seen as by those in authority.

But it's certainly still a factor in the left as well, in different ways. The political left has done more to lead the way on undermining all claims to authority, advancing the idea that everything comes down to power relations, and yet there is still shock that people no longer trust sources of authority, such as doctors or scientists.

Anyhow, re traditionalism, I see no reason to prefer tradition for the sake of tradition alone. All tradition was new at some point. But iconoclasm, the destruction and denigration of tradition for its own sake, for the sake of an amorphously defined "progress" that has no clear view of human flourishing, or "to liberate the exceptional individual," strikes me as the more common problem. There are indeed people who value tradition for tradition's sake, but they have far less influence than those who value desacralizing everything in the name of "progress."

It is the person restrained by custom who most benefit from its destruction. This is unlikely to be the meek and gentle. -

What is real? How do we know what is real?

It's the thing we were discussing. If water was not H2O in Aristotle's day would this mean that being H2O is neither essential nor necessary for water or that water itself changes? Or could heat be caloric? might be a similar sort of question (or was it?) -

What is real? How do we know what is real?

Lots of thinkers. If it's "there are something like essences, but they change," we can consider Hegel, a number of Hegelians, Whitehead, maybe Heidegger (unfolding), a lot of contemporary process philosophers, etc.

If it's "there is nothing like an essence (in the classical sense) but what classical metaphysicians called essences changes" then Deleuze, Kuhn, Butler, Merleau-Ponty, constructivists generally, etc. -

What is faith

You'd imagine this is fairly common today. Why do you find this more pernicious?

First, because people end up offending others without realizing it and holding on to a sort of subtle bigotry.

But more importantly, I think it ties into a large problem in liberal, particularly Anglo-American culture, were nothing can be taken seriously and nothing can be held sacred. Deleuze and Guattari talk about this sort of "desacralization" that occurs under capitalism. I think it leads to a sort of emotional and spiritual constipation. Feeling deeply about anything (thymos), or especially being deeply intellectually invested in an ideal (Logos), as opposed to being properly "pragmatic" (which normally means a focus on safety and epithumia, sensible pleasures) is seen as a sort failing. This is born out of an all-consuming fear of "fanaticism" and "enthusiasm" (something Charles Taylor also documents).

Part of what made Donald Trump's campaign so transgressive was the return to a focus on thymos, whereas elites have long had a common habit of complaining that people were not "voting according to their economic interests" (which apparently ought to have been their aim vis-a-vis politics, the common good).

Today, even in politically radical circles, it seems everything must be covered in several layers of irony and unseriousness. Indeed, all pervasive irony is particularly a hallmark of the alt-right. To care about anything too deeply is to be vulnerable, potentially a "fanatic," or worse "a sucker."

This tendency can also lead towards a sort of elitism, which I think Deneen explains this well using Mill:

Custom may have once served a purpose, Mill acknowledges—in an earlier age, when “men of strong bodies or minds” might flout “the social principle,” it was necessary for “law and discipline, like the Popes struggling against the Emperors, [to] assert a power over the whole man, claiming to control all his life in order to control his character.”9 But custom had come to dominate too extensively; and that “which threatens human nature is not the excess, but the deficiency, of personal impulses and preferences.”10 The unleashing of spontaneous, creative, unpredictable, unconventional, often offensive forms of individuality was Mill’s goal. Extraordinary individuals—the most educated, the most creative, the most adventurous, even the most powerful—freed from the rule of custom, might transform society.