-

What is real? How do we know what is real?

Yes, this akin to the problem of circularity in Locke where the nominal essence by which different things are defined ends up determining the real essence by which they are identified as a certain nominal essence. Nothing seems particularly essential in this formulation, as it's all subject to revision.

But this certainly goes against the intuition that water was water millions of years ago, one which is supported by plenty of empirical evidence.

This is to my mind a general weakness of formulating a theory of essences by begining with language and naming. It puts the effect before the cause, and one needs a sort of circularity to resolve things. -

What is real? How do we know what is real?

Paul Vincent Spade's The Warp and Woof of Metaphysics might frame things in terms you are more familiar with.

Or Klima's comparison, but I would say the first is more direct and accessible.

As Spade (along with many others) remarks, there is confusion because: "In analytic philosophy, there is a view called “Aristotelian essentialism”— by both its supporters and its opponents — that in fact has nothing to do with Aristotle."

Note that subject can be said in two ways, in terms of logic or in terms of metaphysics. In logic, the subject is what any predicate is "attached" to. In metaphysics, subject can be said properly or improperly, as of a thing or as of a things underlying substrate. Substance is said of particular things primarily. It is secondary substance where we see essence, the "type of thing" something is.

The logic interacts with the metaphysics but I am not really sure what to recommend for that aside from just reading the Categories (and Porphyry's Isogogue), the Physics, and Metaphysics. I have no found a really good summary the way I have for some parts of Plato. -

Demonstrating Intelligent Design from the Principle of Sufficient Reason

That's a good example. What is impossible/contradictory is not always obvious. That is one of the risks when talking about potential/possibility in lose terms. We end up affirming the "possibility" of any words we can smash together without obvious contradictions.

This can get sort of out of hand in "bundle" and "pin cushion" theories of predication. E.g. a subject just is a "bundle of predicates," or "predicates attached to some bare haecceity" (the pin cushion that makes things individual). It would seem that anything can become anything else here, because the subject is completely bare.

Anyhow, an interesting thing is that "the first number that violates the Goldbach Conjecture" is a rigid designator. It uniquely specifies a number (if it exists). You could think of such a designator in terms of the shortest program that would retrieve a number too (it is easy to check if a number fits the criteria). But, strangely, this ability to uniquely specify the number fails to reveal its identity. It's a sort of recreation of the Meno Paradox. You don't really know what you're looking for until you've found it. -

Which is the bigger threat: Nominalism or Realism?

Are the particulars not as worthy of being loved, admired, or understood as the abstractions and universals the realist holds dear?

I'm not sure if this makes much sense as a critique. A lot of realism is extremely person centered and sees a strong telos at work in history (the history of particulars). Valuing particulars is not really what is at stake.

Actually, I think some realists attack nominalists precisely for destroying particulars and turning them into a formless "will soup." Note that personalism and phenomenology seems to be biggest in traditional Christian philosophy, which tends to be unrelentingly realist.

I'm hoping someone can point me in the direction of those who see realism as a threat, and we can continue this ancient battle on an even footing.

While there are strong similarities between anti-nominalist critiques from a variety of Eastern and Western sources, I think nominalist critiques of realism will be more diverse because nominalism tends towards greater plurality (for better or worse). There are simply skeptical critiques ("you cannot know that because you cannot know the noumenal,") and there are critiques rooted in a view of freedom primarily has power/potency ("your ideas are keeping you from realizing maximal freedom"). The critique of an eliminitive materialist is going to be different from that or a Nietzschean, which will be different from that of a skeptical liberal, etc.

Ockham is singled out by lots of people, it's a bit of a trope. But it's really the voluntarism that's more important. Arguably, the nominalism is just a means to his voluntarism.

But it's not like all realism comes from the angel of intellectualism. Some seek to find a unity of intellect and will above all distinctions (more common in the East because the "nous" and "heart" do not map neatly to intellect/will e.g. Palamas, but even for Aquinas the distinction of will and intellect in God is purely conceptual, not real, while in Eckhart there is the "darkness above the light" beyond all distinctions as "Unground"). Yet these will tend towards volanturism being "more wrong, particularly as respects man. Or, in the Philokalic tradition, we might even say that volanturism is the state of the sick soul, the presence of the diabolical, linear reason.

I don't think these critiques are totally off-base, although Ockham and Scotus might be bad targets. The later anthropology that comes to dominate modern thought in thinkers like Hume, and its conception of reason in particular, is very close to the description of the mind in the condition of sin/under demonic influence in writers like Evagrius. So they are diametrically opposed in a fairly strong sense. But I think people tend to confuse "moral opprobrium" with a more "philosophical opprobrium" here. -

What is real? How do we know what is real?

“ . . . a position no one familiar with philosophical inquiry could take seriously.”

Do you not see the irony in having the write off fairly popular opinions in philosophy as "unserious" here? Grayling is responding to other professional philosophers. Harris's stories come from professional conferences as well, e.g. a speaker at an ethics conference who claimed that we could not say whether or not another culture was wrong if they tore out the eyes of every third born infant out mere custom because "it's their culture." Nietzsche is, I would imagine, the long-running title holder for "most popular thinker in the West."

But in virtue of what are positions to be dismissed as "unserious?" Again, it seems to me that you have to start with some (more or less foundational) premises here to avoid the problems mentioned in the "Dogmatism and Relativism" thread. And like I said before, the problem you mention seems to apply to affirming all sorts of premises, not just "foundational" ones. People will either affirm what follows from more or less obvious or well-supported premises or they won't. In Harris's example, "tearing infant's eyes out is not good for them," would be the obvious premise in question.

The person denying this premise seems factually wrong. Are they wrong in a moral sense? With that particular premise, I'd say yes. In particular, if they allow children to be blinded when they could have otherwise prevented it, or blind a child because "when in Rome do as the Romans," that seems particularly bad. Whereas, while "act is prior to potency" might be more "foundational," it's hardly blameworthy to have failed to consider it. Those terms need some serious unpacking. "What is known best in itself" is not generally "what is known best to us." What is known best to us is particulars, stuff like "blinding children isn't good for them." If people have any rational responsibility at all (through action or negligence)—and I would tend to say they do—it will tend to lie most heavily here, in these sorts of concrete judgements. -

What is real? How do we know what is real?

That sentence isn't meant to be a definition of essential properties. It's a response to representationalism.

We had a thread on a while back. I think my answer might be a very qualified "yes," as presented through the notions of virtual quantity in Aquinas and similar notions in Platonism and Hegel. Perhaps "more intelligible in itself" would be better. -

What is real? How do we know what is real?

And I'm sure you're right that a "crude relativist" could leave a discussion worse off than they found it, by accusing people who aren't relativists of being wrong. I hope we agree that this doesn't characterize a position that anyone could take seriously.

Lots of people take that sort of view seriously. I see it all the time. We were just in a thread were total anti-realism and relativism re values was being argued, and where "good argument" was framed entirely in terms of persuasion, not truth (i.e. a "good argument" is one that gets people to agree with you—gets you what you want—i.e. a power relation). Virtually every ethics thread on this site had at least one user popping in to add that value is subjective and "objective value" a sort of delusion. You yourself seem to think the septic, if not the relativist, has extremely strong arguments here. It's also the view I was brought up with. Relativism is very popular. It's certainly less popular re theoretical reason, but it is hardly a fringe position there either.

Let me ask, did A.C. Grayling make the "cognitive relativism" thesis discussed here up? Is he objecting to a view no one has advocated for? I posted the thread here because his description of cognitive relativism reminded me of a thesis I had seen presented here before.

Sam Harris likewise opens up the Moral Landscape by running through a number of troubling encounters he had with extreme relativists at academic conferences, and quoting a number of similar positions. If relativism is a hallucination, it's apparently a group one.

I may never understand your rhetorical habit of contrasting Position A with a Position B that no one has ever espoused!

Fictionalism, etc. are popular opinions. Open up a mainstream introductory text on metaphysics, something like the Routledge Contemporary Introduction, and you will find it introduced there as a major position.

No one has ever espoused these positions? I have personally espoused them :rofl:! That was the default I was brought up with. And I have had plenty of conversations on this site with people exposing extreme forms of nominalism. We get someone (normally a new user) popping in to assert epistemic nihilism every few weeks. I assume they rarely stick around because epistemic nihilism makes philosophy fairly boring.

Go check out the sort of questions that get asked to credentialed philosophers on AskPhilosophy. Some people are genuinely confused about how anyone could not be a relativist.

So, I may have misunderstood what you were getting at, but I hardly think I have hallucinated the existence of relativist positions.

But in terms of your particular framing, you said the problem was:

In short, if you start from premises you believe you can show to be foundational, does that commit you to also saying that everything that follows is rationally obligatory?

To which I said:

What would the opposite of this be? You start with premises that are foundational and then refuse to affirm what follows from them?

So:

P

P→Q

But then we affirm:

~Q, or refuse to affirm Q.

Yes, this is what most people would call "irrational." No?

To which you replied:

That's why indisputably foundational premises might be abandoned in favor of something closer to epistemic stance voluntarism. This may not be a worry for you, but many philosophers, myself included, are concerned about the consequences of rational obligation which do seem to follow, as you correctly show, from allegedly indisputable premises. The idea that there is only one right way to see the world, and only one view to take about disagreements, seems counter to how philosophy actually proceeds, in practice, and also morally questionable.

But what you're saying isn't a problem just for "foundational premises," it literally is a problem for affirming any proposition at all. To say:

P

P → Q

Is to say that you believe that the person affirming ~Q is mistaken (or that some further distinction is needed, etc.). Assuming the principle of non-contradiction, it is to say that there is a right way to describe the world and that the right way includes P and Q, not ~P and ~Q. An appeal to "voluntarism" as resolving the issue of disagreement just seems to me like relativism. How is it not?

If you don't want P to imply that the person affirming ~P is mistaken, you need all judgements to be hypothetical. Perhaps that is your solution? I recall you saying that we can reason about values, but only ever generate a "hypothetical ought." All I can say is that this would seem to imply a far-reaching skepticism. Doesn't this imply that we could never say "P is wrong," but only "if you adopted these premises, with these inference rules, P would be wrong?"

And again, I am not sure how holding to premises non-hypothetically necessarily precludes considering that it might be we ourselves who are in error, or attempting to resolve seeming contradictions through distinctions. -

What is real? How do we know what is real?

there's a grab-bag of entities which don't have as firm an answer as we'd like -- dreams, halucinations, mistaken worldviews, historical counter-factuals, hypothetical examples...

Right, or, to continue with the broadly Aristotlian view, we also have stuff like "humanity considered absolutely," "the notion of humanity in my mind," and "humanity as instantiated in Socrates." And we have stuff like "animal" and "animality." One might see animals everywhere, but one never sees just "an animal," but always "an animal of a particular species." And even if one accepts that species and genus are real distinctions, they are certainly not "real" in the way a horse or man is. You can touch and interact with both the horse or man, or point to them. But where in nature can one interact with a 'genus?' The universe is full of quantities, but one never stumbles across "just one" or "just two." This last part seems particularly relevant to the extent that chemistry and physics (and so H2O) are mathematized relationships.

The medievals turned this into a whole series of distinctions. There is ens reale, real existence, and ens rationis, things existing only in the mind. Then we also first intentions (our concepts about things like trees and dogs) and second intentions (our concepts about concepts, such as genus and species).

This becomes relevant when we want to speak of essences. A horse has an essence. What about a centaur though? Is it also an essence, because it seems it could possibly exist, or does it lack an essence because it is really just the mind concatenating two real essences? We might make a distinction here that the centaur represents a known essence, but not an actual essence (because it has no real act of existence). But this isn't quite the "real / unreal" distinction. I think the "real / unreal" distinction might actually reveal itself to be better thought of as many different sorts of distinction.

Water, having a real essence, doesn't change its essence when people learn about it. It has its own unique act of existence (actuality) that is prior to (and informs) cognition.

Hegel has the idea of essences unfolding in time. This is in earlier thinkers like Saint Maximus the Confessor and Eriugena too, although in a different way, since the particulars are just the realization of the universal (its becoming what it is as respects immanence), while things always already what they are in the fullness of the Logos. But then, some readers of Hegel take a similar approach to identify at "the end of history," (Wallace) and it's not clear that water would be the type of thing that is changing in Hegel.

My take, argued below from a past post, would be that it is in the relationship of being known by a rational agent that things most fully "are what they are." Hence, the evolution of human knowledge represents a sort of unfolding of essences in history. However, this unfolding is not arbitrary, although it is subject to contingencies (e.g., it did not need to be Cavendish who discovered that water is H2O for instance). This unfolding occurs according to prior actualities, and the prior actuality by which water is water (which determines its relationship with material knowers) is its form, which is unchanging.

One of the claims that is often made by the representationalist position that Sokolowski critiques is that many of the properties of objects that we are aware of do not exist "in-themselves," and are thus less than fully real. For example: "nothing looks blue 'of-itself, things only look blue to a subject who sees." If the property of "being blue," or of "being recognizably a door" does not exist mind-independently, they argue, such properties must in some way be "constructed by the mind," and thus are less real.

What I'd like to point out is that this sort of relationality seems to be true for all properties. For example, we would tend to say that "being water soluble" is a property of table salt. However, table salt only ever dissolves in water when it is placed in water (in the same way that lemon peels only "taste bitter" when in someone's mouth). The property has to be described as a relation, a two-placed predicate, something like - dissolves(water, salt).

I think there is a good argument to be made that all properties are relational in this way, at least all the properties that we can ever know about. For how could we ever learn about a property that doesn't involve interaction?

So, "appearing blue" is a certain sort of relationship that involves an object, a person, and the environment. However, this in no way makes it a sort of "less real" relation. Salt's dissolving in water involves the same sort of relationality. The environment is always involved too. If it is cold enough, salt will not dissolve in water because water forms its own crystal at cold enough temperatures. Likewise, no physical process results in anything "looking blue" in a dark room, or in a room filled with an anesthetic that would render any observer unconscious.

Intelligibilities (form abstracted from the senses) require syntax to acquire (ratio). They result from bringing many relations together in such a way that they can be "present" at once and understood (intellectus). The grasping of a thing's intelligibility by a rational knower is a very special sort of relationship. This isn't just because it involves phenomenal awareness. "Looking blue" or "tasting bitter" is a relationship between some object and an observer, but these do not "actualize" an intelligibility. What the grasp of an intelligibility by the intellect does is it allows many of an object's relational properties to be present together, often in ways that are not possible otherwise (e.g. something cannot burn and not burn, dissolve and not be dissolved, be wet and not wet, etc. at the same time, but we can know how a thing responds to fire, acid, water, etc.)

For example, salt can dissolve in water. It can also do many other things as it interacts with other chemicals/environments. However, it cannot do all of these at once. Only within the lens of the rational agent are all these properties brought together. E.g., water can boil and it can freeze, but it can't do both simultaneously. Yet in the mind of the chemist, water's properties in myriad contexts can be brought together.

In a certain way then, things are most what they are when their intelligibility is grasped by a rational agent. For, over any given interval, a thing will only tend to manifest a small number of its properties — properties which make the thing "what it is." E.g., a given salt crystal over a given interval only interacts with one environment; all of its relational properties are not actualized. Yet in the mind of the rational agent who knows a thing well, a vast number of relational properties are brought together. If a thing "is what it does," then it is in the knowing mind that "what it does" is most fully actualized. And this is accomplished through syntax, which allows disparate relations to be combined, divided, and concatenated across time and space.

So, rather than the relationship between knower and known being a sort of "less real" relationship, I would argue it is the most real relationship because it is a relationship where all of a things disparate properties given different environments can be brough together. And this is a relationship that is realized in history.

I am reminded here that in Genesis God first speaks being into existence, but then presents being to Man to know and name himself. There is the being of things within infinite being, and then their unfolding in immanence, the two approaching each other (e.g. in the, admittedly suspect, idea of the "Omega Point"). -

Why did Cleopatra not play Rock'n'Roll?

I like Fisher for some things, but I'd rather say that we are surfing on the waves of Zygmunt Bauman's "liquid modernity." We haven't entered a "post-modern period," we're just doing modernity turned up to 11.

Maybe the post-modern period will come with some AI singularity, or maybe it will be Deely's vision of a semiotic age, a return to realism (or maybe both?).

Let's pretend unique musical forms aren't dead (nor history either) and 1000 years later, people are listening to Drock music. Why aren't we listening to Drock music now?

I'm not sure, technical and material limits seem to be fading away. We are able to make any sound wave that can be differentiated by the human ear. But AI will allow people to cycle through the possibility space way more rapidly than they could in the old days. Drock is already out there, potentially. It will now be extremely easy to actualize. You can even actualize the music videos to go along with the music easily.

The problem is that, because it is so easy to actualize Drock, and Brock, and Krock, and Zrock, it might simply come and go without market share, entertaining only a few ears. The sound waves will be actualized, but perhaps not the "movement" as a social force.

Here is the analogy I'd use: on a still pond, you can throw a few rocks in and get recognizable patterns of waves interacting. It's a good signal to noise ratio.

By contrast, the future, with AI media, is more like a pond in a torrential downpour. All surface tension is lost as billions of scattered drops hit the surface at all angles, making the effects of any one indiscernible. In such an environment, the only way to effect the overall ecosystem is to do something like hurl a meteor into the lake, or drive a large boat through the waters, or wait for the rains to pass.

As potential media becomes easier and easier to actualize, the actual space of media comes to resemble the potential space. What you get is the elevation of potency over actuality (already the hallmark of modern thought), but now this shift is becoming instantiated in the realm of entertainment media (which is itself the substrate for the realm of man's intellectual life). This brings forth the risk of what R. Scott Bakker calls the "semantic apocalypse." This risk is doubled if man begins to edit himself, his nature (through gene editing, cybernetics, tailored drug administration) such that we get a rupture in our shared cognitive ecology, a sort of divergent evolution.

The Logos might be envisioned as a sound wave, a song. But it is one of infinite amplitude and frequency, such that all waves cancel each other out in their antipode. The result is silence, but the pregnant silence of the Pleroma. It is intelligible act that must break this equilibrium, giving birth to something specific and historical through limitation. As the Kabbalahists say, God's first act had to be one of withdrawal to make space for the world, a withdrawal of actuality into potency.

In the Age of Actualization, we each become like the librarians of Borges' "Library of Babel." A harrowing thought. Basically, I really don't like "AI slop." :rofl: -

Why did Cleopatra not play Rock'n'Roll?

Notice that there being a "Youth Culture" in general is something quite new.

And arguably something already vanishing, a product of a particular moment in history. I've seen a number of people observe how the 50s, 60s, 70s, 80s, and even 90s had very distinct styles, new musical genres, etc. This seems to have stopped in the 00s. Today some kids dress like hippies, some in the 90s goth style, some as 80s punk rockers, etc. Certainly, styles still come and go, but fast fashion has made them so rapid and so multitudinous that they no longer have the global reach they once did.

It's a sort of balkanization of taste. It's the same with other forms of media. People used to watch the same shows because that's what was broadcast, read the same books, play the same video games. The internet, social media, and technological advances that have massively lowered the barriers to entry for producing media (e.g. single video game developers) have led to an acceleration of multiplicity. When Trent Reznor was a one man band with Nine Inch Nails in 1989, it was somewhat unique (at least for a chart topper); not so much anymore.

Interestingly, it's the very freedom to create and consume, the breaking down of barriers, that makes "everywhere becomes everywhere else." And this happens on the political stage too, e.g. the standardizations of the EU make different places similar. Huge influxes of immigrants make English increasingly common across city centers on the continent, and you even see a lot of English-language universities/programs. A sort of move to "monoculture through diversity" (although it might be called a sort of "anti-culture," since it isn't so much a "cultivation" that is occuring).

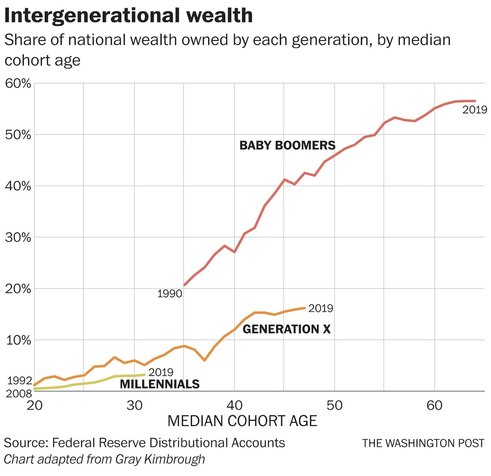

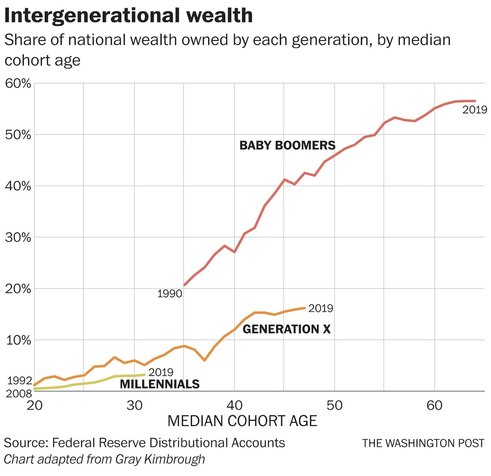

Of course, demographics have something to do with it too. The youth once made up the largest share of the population by far. Now they are the smallest. The youth were once themselves quite homogeneous, now they are the most likely to come from diffuse backgrounds. For the Baby Boomers in the US, the presidency came to their generation fairly early in life, and control of Congress shortly after. They kept it for 30+ years, becoming a huge supermajority after the Great Recession, when the average age of people in high office surged (cabinets also average about retirement age). And the share of society's wealth in the hands of the young has followed this trend. So, a more classical view might just be that money and political power drive the dominance of culture.

-

What is real? How do we know what is real?

The idea that "some people are not perfected" by one's own presumably correct doctrine makes me smile, but I suppose it expresses the attitude you'd have to take if you saw philosophy as an attempt to make a single correct view triumph, and the failure to do so is down to the other guy, not the issue itself.

It's just an admittedly old-fashioned way of putting it. People have a potential for knowledge/understanding/good behavior, etc. The goal of education, law, etc. is to actualize this potential more fully ("bringing it to perfection.") One needn't think one's law is perfect or infallible to think that people are improved by doing the minimum to follow it (e.g. littering), and so to for philosophy.

But when it comes to philosophical views? I would have said that one of the key differences between thinking philosophically and our ordinary ways of thinking about the world is the recognition that we don't propose ignorance or bad faith as a plausible explanation for someone's disagreeing with us. And I have to admit how difficult it is for me even to imagine carrying on as you suggest.

How are you defining philosophy here? If philosophy encompasses the sciences, ethics, politics, aesthetics, and our most bedrock metaphysical assumptions—if it is the broadest study of human knowledge—I hardly see how it's the sort of thing than can be rendered a manner of taste without trivializing essentially everything

Note though that it would be a sort of strawman to tie an acknowledgment of first principles to a "one true description of being," or a "one true methodology." There might be many methodologies, useful for different things. A broad "realism" is not committed to, and in general does not proclaim, "a one true description of being or ethics." Rather, it claims that there are descriptions that are more or less correct and that all correct descriptions share morphisms and do not contradict one another. That's all that's needed.

I share your concerns, but like I said, I think there is a good philosophical argument for the idea that relativism will actually tend to make philosophy into more of a power struggle/matter of politics. I think one can even observe this happening in some cases. Scientific debate can always get heated, but things get particularly fraught when the unitary truth is abandoned in exchange for "different approaches" that are allowed to contradict one another. This is where you get "Aryan versus Jewish physics," "capitalist versus Marxist genetics," and claims to a sui generis but equally valid "feminist epistemology." How can one bridge the gap in the "culture wars" if different identity groups have different epistemologies?

Whereas I don't share the concern over being "rational" as a sort of limitation or source of unfreedom. This seems to me to only be a problem under more deflated notions of reason as something more akin to a mere calculator.

What would you think of the method that says, "Hmm, tell me more. Help me understand why you say this. Here's how I see it. Let's see what we can learn"?

Is this not open to people who deny a sort of pluralism or relativism? I don't think so. Again, when I think of which areas of philosophy seem most siloed, it seems that the exact opposite might be the case. The committed Nietzschean is, in my experience at least, the person least interested in understanding other ethical theories, instead waving them away with (normally unflattering) arguments from psychoanalysis. But this isn't incidental, it flows from their relativism.

When parts of philosophy become matters of taste or art, one is then able to dismiss broad areas on merely aesthetic grounds, to simply not take them seriously. Whereas more evangelical philosophies, while they might tend to be more dogmatic, also seem to have much more of an incentive to understand other positions, both out of fear that their own position might be wrong, or to convince others. One cannot fear error if it is not possible to be wrong. -

"Substance" in Philosophical Discourse

Right, but there is a difference between methodological bracketing and simplifying assumptions and allowing that bracketing to become a sort of metaphysics that defines things like black holes, birds, and trees in terms of "usefulness."

And a lot of times these assumptions do lead to contradictory claims about reality; that's an ongoing tension in the sciences. The physics of atoms does not comport with the physics of relativistic scales. Explanations of biological function do not comport with "everything is blind mechanism." The Extended Evolutionary Synthesis controversy centers around this disconnect. Eliminitive materialism does not comport with pretty much the whole of the social sciences, which have a role for conscious agency. The "Hard Problem of Consciousness" centers around this seeming contradiction. A lot of contradictions arise from this bracketing, which is fine if it is just a methodological tool for simplifying models and predictions, but problematic if the model is inflated into a metaphysics.

It appears that it is a common way of thinking of "substance" as being something fundamental. According to the above descriptions, substance would not be fundamental but would simply be what we call a thing that consists of only type of atom or molecule, and atoms are not stuff but are excitations in fields. We abandoned this view of atoms being little billiard balls bouncing around in favor of quantum mechanics that talks about wave functions and superposition. So it appears that science at least has abandoned the idea that substance is something fundamental, in favor of a view that process appears to be fundamental and substances are just a type of process, or relation between certain types of atoms.

With the rejection of the "billiard ball model" has tended to come a rejection of "smallism" the claim that all facts about large things are reducible to facts about smaller parts. Prima facie, there is no reason why "smaller" should entail "more fundamental." Nor is it clear that wholes should always be definable in terms of their parts. The opposite appears to be the case in some instances.

But this can, and has, led to a flip to a sort of bigism. Only fields are fundamental because they are truly universal. Bigger is more fundamental.

Yet one might think that what is needed is a via media here between bigism and smallism. That's what the idea of substance (in some usages at least) is called in to do, to explain how there are wholes (nouns) and not just verbs (interactions), and to explain the intrinsic intelligibility by which things are things (as opposed to all things being a product of a sort of bare human will—"bare" because the will cannot be informed by the intellect re things if things' existence is itself a product of the will).

In discussions of emergence, it's often said that whatever is "strongly emergent" would have to also be "fundamental." After all, it isn't reducible. This means that a rejection of reductionism is a rejection of the idea that "fundamental = small."

However, "strong emergence" starts to look like sorcery in many framings. At the same time, reductionism has its own problems, not the least of which is a pretty terrible empirical track record. What's the big reduction outside of thermodynamics to statistical mechanics? Chemistry is not an immature field and yet a century on the basics of molecular structure have yet to be reduced. Unifications seem far more common than reductions (which suggests bigism more than smallism). Reductionism starts to look more like a hopeful metaphysical presupposition, a hunch, than an empirical theory (and no doubt, it is partly popular because it is such an intuition, since the basic idea is older than Socrates and crops up throughout history).

Hence, principles and their role in form (and defining beings-plural): :smile:

The epistemic issues raised by multiplicity and ceaseless change are addressed by Aristotle’s distinction between principles and causes. Aristotle presents this distinction early in the Physics through a criticism of Anaxagoras.1 Anaxagoras posits an infinite number of principles at work in the world. Were Anaxagoras correct, discursive knowledge would be impossible. For instance, if we wanted to know “how bows work,” we would have to come to know each individual instance of a bow shooting an arrow, since there would be no unifying principle through which all bows work. Yet we cannot come to know an infinite multitude in a finite time.2

However, an infinite (or practically infinite) number of causes does not preclude meaningful knowledge if we allow that many causes might be known through a single principle (a One), which manifests at many times and in many places (the Many). Further, such principles do seem to be knowable. For instance, the principle of lift allows us to explain many instances of flight, both as respects animals and flying machines. Moreover, a single unifying principle might be relevant to many distinct sciences, just as the principle of lift informs both our understanding of flying organisms (biology) and flying machines (engineering).

For Aristotle, what are “better known to us” are the concrete particulars experienced directly by the senses. By contrast, what are “better known in themselves” are the more general principles at work in the world.3,i Since every effect is a sign of its causes, we can move from the unmanageable multiplicity of concrete particulars to a deeper understanding of the world.ii

For instance, individual insects are what are best known to us. In most parts of the world, we can directly experience vast multitudes of them simply by stepping outside our homes. However, there are 200 million insects for each human on the planet, and perhaps 30 million insect species.4 If knowledge could only be acquired through the experience of particulars, it seems that we could only ever come to know an infinitesimally small amount of what there is to know about insects. However, the entomologist is able to understand much about insects because they understand the principles that are unequally realized in individual species and particular members of those species.iii

Some principles are more general than others. For example, one of the most consequential paradigm shifts across the sciences in the past fifty years has been the broad application of the methods of information theory, complexity studies, and cybernetics to a wide array of sciences. This has allowed scientists to explain disparate phenomena across the natural and social sciences using the same principles. For instance, the same principles can be used to explain both how heart cells synchronize and why Asian fireflies blink in unison.1 The same is true for how the body’s production of lymphocytes (a white blood cell) takes advantage of the same goal-direct “parallel terraced scan” technique developed independently by computer programmers and used by ants in foraging.2

Notably, such unifications are not reductions. Clearly, firefly behavior is not reducible to heart cell behavior or vice versa. Indeed, such unifications tend to be “top-down” explanations, focusing on similarities between systems taken as wholes, as opposed to “bottom-up” explanations that attempts to explain wholes in terms of their parts.i...

At the outset of the second book of the Physics, Aristotle identifies proper beings as those things that are the source of their own production. (i.e. “possessing a nature”). Beings make up a whole—a whole which is oriented towards some end. This definition would seem to exclude mere parts of an organism. For example, a red blood cell is not the source of its own production, nor is it a self-governing whole.

On this view, living things would most fully represent “beings.” By contrast, something like a rock is not a proper being. A rock is a mere bundle of external causes. Moreover, if one breaks a rock in half, one simply has two smaller rocks (i.e., an accidental change). Whereas, if one cuts a cat in half, the cat—as a being—will lose its unity and cease to exist (i.e. death, a substantial change).

There are gradations in the level of unity something can have. Aristotle maintains that substantial change (i.e., the change by which one type of thing becomes another type of thing, e.g. a man becoming a corpse) involves contradictory opposition. That is, a thing is either man or not-man, fish or not-fish. It would not make sense for anything to be “half-man.”i

By contrast, unity involves contrary opposition.1 Things might be more or less unified, and more or less divisible. For instance, a volume of water in a jar is very easy to divide. A water molecule less so. We can think of the living organism as achieving a higher sort of unity, such that its diverse multitude of parts come to be truly unified into a whole through an aim.ii

For Aristotle, unity, “oneness” is the ground for saying that there are any discrete things at all. To say that there is “one duck” requires an ability to recognize a duck as a whole, to have “duck” as a measure. Likewise, to say that there are “three ducks” requires the measure “duck” by which a multitude of wholes is demarcated. Magnitude is likewise defined by unity, since it would not make sense to refer to a “half-foot” or a “quarter-note” without a measure by which a whole foot or note is known.2...

[Organisms are most properly wholes because they are unified by aims. Life is goal-directed.] What then can we say about the ways in which non-living things can be more or less unified? Here, the research on complexity and self-organizing, dissipative systems might be helpful. Consider very large objects such as, stars, nebulae, planets, and galaxies as an example. These are so large that the relatively weak force of gravity allows them to possess a sort of unity. Even if a planet is hit by another planet (our best hypothesis for how our own moon formed), it will reform due to the attractive power of gravity. Likewise, stars, galaxies, etc. have definable “life-cycles,” and represent a sort of “self-organizing system,” even though they are far less self-organizing than organisms. By contrast, a rock has a sort of arbitrary unity (although it does not lack all unity! We can clearly distinguish discrete rocks in a non-arbitrary fashion).

-

What is real? How do we know what is real?

But isn't the goal of the kind of philosophy you espouse to resolve those disputes? More, to claim that in principle they must be resolvable? This would make the history of philosophy, taken in toto, a story of failure, since the disputes live on. That's the part that I have trouble recognizing as my own experience of doing philosophy with others.

I don't see how this is a problem. The fact that people still break the law is not an argument against good jurisprudence. The fact that people still sin is not an argument against theology. The fact that some students don't learn is not an argument against teaching. Even if one was committed to a very rigid, foundationalist philosophy (or theology, or theory of law, etc.) it would not follow that one's own doctrine is undermined by the fact that some people are not perfected by these. It's like how of the strictest ascetics, with a very strong position on the need to "uproot the passions" nonetheless maintain that most people will remain slaves to the passions.

Anyhow, as Gibbon says: "History…is, indeed, little more than the register of the crimes, follies, and misfortunes of mankind." :grin: Or, if there is some sort of progress in history, a telos, a dialectical unfolding, a transcendence of finitude...it ain't easy. Socrates has to die to make his point.

The worry here is that the foundationalist philosopher who believes that everything of importance can be demonstrated apodictically, thus resolving all disagreements in favor of a position they hold, will treat those who disagree as if they must be doing something wrong, whether due to ignorance, stupidity, stubbornness, or malice.

Wouldn't this just be true in general? If we think we know something, and people do not accept it, or affirm something contrary, we think they are ignorant in that matter (or I suppose acting in bad faith). The only way to avoid this is a sort of pluralism re truth or simply lacking conviction (the deflation of truth to a matter of taste).

Second, this suggests that philosophy based on first principles and rationalism will be particularly inflexible and prone to dogmatism, while pluralism or relativism will tend not to be. I've discussed philosophy a lot of places online and in person over the years. Do I think this is so?

No, not really. If anything, it might go in the other direction. I have seen a great many people be quite aggressive in asserting pluralism and relativism. Particularly, over the years, I have encountered a lot of Nietzsche fans who assert their particular flavor of pluralistic moral anti-realism with a great deal of vitriol.

Anywhere philosophy is discussed, there is a tendency for people to defend thinkers by claiming that anyone who disagrees with them simply lacks the ability to understand them. This happens with all sorts of philosophy. It's more common with difficult or abstruse thinkers, who are indeed easy to misunderstand (e.g. Kant), so the criticism is sometimes valid. But it seems to me that this happens less with say, analytic philosophy, with its heavy focus on argument, and the most with post-modern thinkers (and particularly with Nietzsche). But this is a sort of dogmatism rearing it's head precisely where relativism is strongest. Likewise, these are the areas where the "cult of personality" seems to become most dominant (we have had threads on this, so I know I'm not alone in this appraisal).

Is this just incidental? I don't think so. I had a thread before about the relationship between relativism, misology, emotivism, and dogmatism. In a philosophy that claims that knowledge claims come down to power relations, one that claims that moral claims are just expressions of emotion, or one where beliefs are just the result of being inculcated in a certain sort of social game, etc. the role of rational argument is necessarily limited. There is only so much it can do; we have stepped outside logocentrism, for better or worse. Whereas, while belief in accessible first principles might lead to dogmatism, I do not see why it might not also lead to greater faith in argument and the capacity to demonstrate one's position in good faith in the long run.

Third, while telling people they are wrong about closely held metaphysical or moral beliefs can produce friction, I don't see how other methods, i.e. explaining broad fields as pseudoproblems or declaring all sides of the debate "meaningless," claiming they involve merely relative truths, or that they deal in "fictions," etc. is necessarily any less so. Again, this is a case where sometimes it seems like the opposite is sometimes true.

I don't actually think that's true. Can you cite a relativist philosopher who says this, or who's been unable to respond to this criticism? If it were that simple to refute relativism, surely the position would be in the graveyard by now!

This wasn't meant as a refutation of relativism, it's just pointing out that it doesn't make people play nice or avoid disagreement. Indeed, relativists and pluralists can be plenty aggressive in arguing for their position (whether the relativist is contradicts themselves in this depends on the sort of relativism). They don't fall victim to this criticism because they don't use relativism as a way to avoid friction, but assert it explicitly at the expense of non-relativists (often as an "obvious truth").

That said, I have had this exact conversation with Joshs before (I think more than once), on truth being situated within metaphysical systems which are embraced based on a sort of "usefulness," and I definitely do think that such a position still has to call other positions wrong. I used Saint Augustine has an example in that discussion. If the relativistic view on truth is correct, then it has to say Augustine is wrong because Augustine doesn't think truth is relative in this way. To say he is "also correct" is to not take what he says seriously.

More broadly, I think this is somewhat related to an abuse of the principle of charity one sometimes sees, where pluralists translate monists into holding just "one position among many," to make their arguments more acceptable (more acceptable to the pluralists anyhow). Some (but not all) perennialists tend to do this with religious claims too. -

What is real? How do we know what is real?

But I'd put it in historicist terms -- we can imagine Kripke being transplanted to another time with different concepts being taken seriously,

So, for example: "Fire is the release of phlogiston."

I think the essentialist would tend to say the concept of fire (the understanding in the mind actualized by fire being experienced through the senses) stays the same, but our intentions towards it are clarified. Fire hasn't changed, but our intellects have become more adequate to it, and towards its relationship with other things. The identity of water as H2O clarifies a whole host of relations between water and other things (the way water acts in the world), and it is through those interactions that things are epistemically accessible at all.

I suppose one challenge to the essentialist lies in pursuing the primacy of interaction into something like a process metaphysics, dissolving the thing-ness (substance) of water into processes. Yet this has its own difficulties. -

What is real? How do we know what is real?

The framing of the infinite regress of justifications is in Posterior Analytics I.2, although I think it might show up elsewhere. Aristotle answers that justification does stop, but it stops in a different form of knowing (of which he actually has many in his anthropology). This is covered in Posterior Analytics II but I hesitate to say that this is "the argument" because its plausibility is greatly enhanced by the work done in De Anima, the Physics, and the Metaphysics.

The beauty of this solution is that it is very broad, and can largely be argued as flowing from the primacy of actuality over potency (without which, arguably, being would be incoherent and wisdom a lost cause anyhow). But, I think a difficulty here, when one reads a work like De Anima is the desire to see it as some sort of contemporary empirical theory, which it sort of is, but this isn't really where its value lies. The basic notion of potential in the mind being actualized by the form (act) by which anything interacts with it in this way and not that way is perhaps more important that the exact typology/psychology of the senses (the faculties) that Aristotle develops. I think that one can accept that things like "the common sense" and the "cogitative faculty" get "something right" without having to be overly committed to them (similar to Plato's parts of the soul, which are useful as a psychology, but less so if they become as sort of ridged description). In terms of connecting this broad framework to the contemporary sciences of physics, perception, and information, you'd need to look to contemporary Aristotlians and Thomists.

On a side note, a while back I came across this interesting dissertation on the more Platonic/Plotinian/Augustinian conception of noesis: https://theses.gla.ac.uk/2741/

No, that would be ruled out, so the opposite would indeed be irrational. That's why indisputably foundational premises might be abandoned in favor of something closer to epistemic stance voluntarism

And in virtue of what is a stance adopted? Reason? Sentiment? Aesthetic taste? Sheer impulse?

If stances are adopted according to reason, then you have the same problem. If they are adopted according to some standard that is irrational, you seem to have an irrational relativism.

This may not be a worry for you, but many philosophers, myself included, are concerned about the consequences of rational obligation which do seem to follow, as you correctly show, from allegedly indisputable premises. The idea that there is only one right way to see the world, and only one view to take about disagreements, seems counter to how philosophy actually proceeds, in practice,

If they are disputable they will certainly be disputed, hence "how philosophy actually proceeds." That someone claims that a premise is indisputable does not make it so.

and also morally questionable.

I don't get this one. How so?

I'm getting confused by "rational nature" and "finite nature" and "transcend their finitude". Could you rephrase in more ordinary terms? Are you talking about objectivity and subjectivity?

A rational nature, as in "possessing a rational soul," or a will and intellect. But we need not accept those exact distinctions, just that man has an intellectual appetite for truth (including knowing the truth about what is truly best). For Plato, and a great deal of thinkers following him, it is the desire to know what is "really true" and "truly good" that moves us beyond the given of what we already are, taking us out beyond current beliefs and desires (what we already are).

If we did not have a desire for truth itself (the "love of wisdom"), if "all men do [not] by nature desire to know," then we would only ever learn things accidentally as we uncritically and unquestioningly followed our sensible appetites (a sort of slavish unfreedom). In this psychology, rationality is a prerequisite for freedom. Freedom is not constrained by "being 'forced' to do what is rational," but rather, because reason always relates to the whole (it is "catholic") it draws us out beyond ourselves (there is an ecstasis in knowing, "everything is received in the manner of the receiver," but the knower is also changed by knowledge). Because knowledge changes the knower (knowing by becoming), the freedom to become is deeply bound up in rationality, whilst ignorance is a limit on freedom.

And would a strong epistemology of rational obligation mean that we were wrong in doing this?

Wrong in doing what exactly, not affirming truth? That truth is preferable to falsity seems like a prerequisite assumption for even concerning oneself with epistemology. One ought to seek truth because truth is more desirable.

Yet we might suppose that people have a right to make mistakes, or to be wrong. This is often part of the learning process. Wisdom, knowledge, these involve understanding, so it would not make sense to "force people to affirm what they do not understand." Yet neither would it make sense to deny that they can be wrong.

One of the problems with relativism as a nice solution to disagreements is that it doesn't actually allow "everyone to be right" anyhow. It says that everyone who isn't a relativist (most thinkers) is wrong. If you tell the non-relativist, "no, you can be right too, it's just that it's simply 'true for you'" they shall just reply: "but I maintain that it is true for everyone, not that it is 'true for me.'" -

Demonstrating Intelligent Design from the Principle of Sufficient Reason

You seem to be hung up on the idea that every property of an object is essential to that object's identity. If not, then two distinct objects could have the same identity. Why is this difficult for you to accept?

This is what haecceity is called in to do (although, a lot of philosophy of quantum mechanics denies particles' haecceity, e.g. Wheeler's idea of there just being one electron in the whole universe that is in many places at once).

It's a tough issue. What individuates things is a matter of much discussion, and ties into the difference between "what they are" and "that they are."

It leads to implausible claims. Joe has the property of being awake at T1, and the property of being asleep at T2.

Indeed. The same sort of thing happens when all properties are said to be accidental (which seems to be the much more common claim in contemporary philosophy and on TFP). I will give credit for embracing the more unique formulation. It sort of reminds me of Parmenides in a way.

But surely , there is a way to do counterfactual reasoning, right? So, "if this plant was not watered, it would not have grown." But the plant in question has to be, at least in some sense, the same plant, or else we would just be saying that if the plant was a different plant it might not have grown.

On this point:

What I have been complaining about is the way that modal logic is interpreted and applied. To avoid determinism, (fatalism), we must allow that any spoken about object has no existence, or true identity, in the future, and therefore the fundamental laws are inapplicable. It is a possible object, and this means that it cannot have a true identity. But in the past, the object had existence, therefore identity, and the laws are applicable. If we do not respect this difference, that modal logic can be applied consistently with the three laws toward the past, but it cannot be applied consistently with the three laws toward the future, equivocation of different senses of "possible" is implied, along with significant misunderstanding

Maybe you would be more amenable to this framing:

Now, in the present, certain things have certain potentials. Joe might potentially be asleep at 10 PM or be awake then. A rock, by contrast, cannot be asleep or awake. So, we can speak about possibilities in the future according to the ways in which things in the present possess potentiality.

Likewise, in counterfactual reasoning, we speak to the potencies that some thing possessed in the past, and then discuss what would be true if they were actualized differently. IDK if this works without at least some differentiation between substance and accidents, but it might at least resolve some of the concerns.

The past is, in some sense, necessary, having already become actual. But when we speak to "possible worlds" with a different past, we are simply talking about different potentialities becoming actualized. -

What is real? How do we know what is real?

In short, if you start from premises you believe you can show to be foundational, does that commit you to also saying that everything that follows is rationally obligatory?

What would the opposite of this be? You start with premises that are foundational and then refuse to affirm what follows from them?

So:

P

P→Q

But then we affirm:

~Q, or refuse to affirm Q.

Yes, this is what most people would call "irrational." No?

[/quote]That you are caused to so reason?

It seems obvious that people can contradict themselves, no? So there is a sort of arbitrary freedom here. But this seems to make reason extrinsic to the rational nature, a source of constraint rather than the very means by which finite natures can transcend their finitude by questioning current belief and desire. So, I might simply disagree with the anthropology that makes this "causing" problematic. Such a causation isn't even determinant though, since people can simply act inconsistently if they chose to . -

The Forms

To be clear, when I say he has reductionist tendencies, I don't mean "materialist reductionism." That substantial form is built up from other "regularities" can seem reductionist, without implying anything about materialism. Maybe it isn't though; this might just be an expression of something like Thomistic virtual quantity (qualitative intensity). His thought is sort of opaque at times, so I am not confident in that judgement. -

What is real? How do we know what is real?

As noted in the other thread, PA just lays out the challenge to scientific knowledge and demonstration. The full justification of the solution spans a good deal of the corpus because it involves the way man comes to know, and a sort of "metaphysics of knowledge."

The problem with this sort of "argument from psychoanalysis" is that they are very easy to develop. One could create the same sort of argument re attacks on teleology. Moderns come to define freedom in terms of potency. Determinant telos is a threat to man's unlimited freedom. Hence, they set out to develop a philosophy where everything is ultimately grounded in the human will, in "pragmatism," etc. (and so appetite and choice—will). Pace arguments to the effect that people "cling to teleology because it makes them feel good," Nietzsche is by far and away the best selling philosopher of our era it would seem. He dominates bookstore shelves and popular discussions of philosophy. Far from being "terrified" of such views, the masses have been inclined towards them (Nietzsche no doubt is spinning in his grave). Likewise, far from facing despair from his "universe devoid of meaning and purpose," Bertrand Russell, despite his sorted personal life, sometimes seems to elevate himself above famous saints in moral standing by having the courage to accept this.

Afterall, if there is psychological comfort in teleology, there is no doubt also psychological comfort in: "nothing one does is ever truly good or bad," or "we decide," etc.

Such arguments might be plausible, or even true to varying degrees, but they don't actually address the real issue at hand. -

Reading group: Negative Dialectics by Theodor Adorno

Good stuff, but here is the thing: the bolded conclusion isn't justified. It begs the question. From the fact that we impose artificial boundaries on hurricanes it doesn't follow that hurricanes don't exist apart from those boundaries.

:up:

Right, and common objections to this tend to rely on the assumption that any such systems must be defined according to some sort of rigid binary. But if unity (by which anything is one thing) and multiplicity represent a sort of contrariety (and so to for relative degrees of self-organization, self-government, self-determination), then we shouldn't expect the distinctions to be distinct. The storm need not have exact boundaries to be a storm. If the boundaries are "artificial" they nonetheless do not spring from the aether uncaused, but unfold for reasons (per Hegel at least).

In particular, rigid "building block" ontologies have a problem with defining systems or things. You can see this in the "Problem of the Many." Which molecules exactly make up a cloud? Which atoms exactly make up a cat?

But this is a demand that the higher order be explained in terms of, and ordered to, the lower, i.e. a cat is already assumed to be a mere concatenation lower constituents, as opposed to the higher, unifying principle itself.

Whereas, the focus on the principle of unity would seem to be a focus on "yes-saying," on actuality and form. An idealism? I suppose that depends on how one looks at such an actuality. But an actuality also determines potencies and powers, so it is always not just a "yes-saying," and specifically not a static yes-saying if this is kept in view, because the actuality of things is directed towards change/becoming, towards a potency to be actualized.

Actually, movement towards any goal assumes that the goal hasn't yet been reached, so there is a sort of bracketed priority of potency and difference in this. If a thing were not different from its perfection, it would have no impetus to change. -

Currently ReadingFacing East in Winter by Rowan Williams. It's a philosophical treatment of the doctrines in Orthodox Christianity, primarily those in the Philokalia, as read through its most cited contributor, Saint Maximus the Confessor.

I have been looking for a book like this to recommend for a while, one that can lay out the philosophical aspects of Eastern thought in a clear and accessible manner. Von Balthasar's Cosmic Liturgy on Maximus is fantastic, but it is quite technical, and at times abstruse, and doesn't do as much to connect the theoretical to the practical as it might. But one of the defining features of Eastern thought is the way the practical deeply informs the theoretical.

Edit: only the introduction of this book is accessible and it is actually quite challenging and presupposes as a depth of knowledge in Orthodox thought and contemporary Continental philosophy to really get it all. -

"Substance" in Philosophical Discourse

Doesn't it depend on what the current goal is? Is it useful to think of all living and non-living things as part of one group? If so, when is that the case? Is it useful to think of living things as separate from non-living things? If so, when is that the case?

Try applying this logic to other questions. Does Iraq really have or not have WMD, or does it depend on what is useful to us? Are there truly substances, things, or does the existence of any thing at all (even the human person) merely depend on our goals? How can we have goals if our existence is itself a question of usefulness?

Basically, are there facts about the world (e.g. that something is living or not), or do these just depend on what our goals are?

Here is the problem with trying to ground epistemology in "usefulness:" either there are facts about what is useful or there aren't. If nothing is "truly useful," but instead is "useful because we feel it is so," then we have relativism. For the fundamentalist, it is useful to deny evolution for instance. In 1984, it is useful for both citizens and the Party to live by "whatever Big Brother says is true is true."

Whereas, if things are truly useful or not, then such usefulness has a cause. It can be explained. But then this explanation will lead back to questions like "are living things truly (relatively) discrete substances, organic wholes?"

So, while I am all for a constrained form of pragmatism, I think pragmatism is incoherent as a basic epistemic principle and leads towards an infinite regress: See the OP: https://thephilosophyforum.com/discussion/15308/pragmatism-without-goodness/p1

This does not mean that all correct descriptions of reality have to be "one way," or that such distinction involve discrete binaries (contradictory opposition). Many will involve contrary opposition (a sliding scale) and analogy. But I don't think "cats are real or not depending on what we are trying to do," leads anywhere good (granted that it may make sense to bracket such questions at times, or make simplifying assumptions). It ultimately ends up putting the will before the intellect, potency before actuality.

not that the universe is contradictory or ill-defined.

Exactly. The reduction of reality to quantity was originally a sort of methodological bracketing. I guess the difficulty is that, when such a bracketing is useful, this usefulness is then used as justification for inflating it into a full blown metaphysics. -

"Substance" in Philosophical Discourse

All physical beings are changing and so arguably they all are processes, yes. Mark Bickhard had a good (if flawed) article on this that I've posted parts of before (since it's in one of those $250 academic tomes no one without library access will ever get to read).

https://thephilosophyforum.com/discussion/comment/826617

https://thephilosophyforum.com/discussion/comment/826619

Terrance Deacon makes a similar appeal to a metaphysics of process as resolving key issues in our understanding of emergence (he also uses Aristotle a lot):

House of Cards?

The most influential critiques of ontological emergence theories target these notions of downward causality and the role that the emergent whole plays with respect to its parts. To the extent that the emergence of a supposedly novel higher - level phenomenon is thought to exert causal influence on the component processes that gave rise to it, we might worry that we risk double - counting the same causal influence, or even falling into a vicious regress error — with properties of parts explaining properties of wholes explaining properties of parts. Probably the most devastating critique of the emergentist enterprise explores these logical problems. This critique was provided by the contemporary American philosopher Jaegwon Kim in a series of articles and monographs in the 1980s and 1990s, and is often considered to be a refutation of ontological (or strong) emergence theories in general, that is, theories that argue that the causal properties of higher - order phenomena cannot be attributed to lower - level components and their interactions. However, as Kim himself points out, it is rather only a challenge to emergence theories that are based on the particular metaphysical assumptions of substance metaphysics (roughly, that the properties of things inhere in their material constitution), and as such it forces us to find another footing for a coherent conception of emergence.

The critique is subtle and complicated, and I would agree that it is devastating for the conception of emergence that it targets. It can be simplified and boiled down to something like this: Assuming that we live in a world without magic (i.e., the causal closure principle, discussed in chapter 1), and that all composite entities like organisms are made of simpler components without residue, down to some ultimate elementary particles, and assuming that physical interactions ultimately require that these constituents and their causal powers (i.e., physical properties) are the necessary substrate for any physical interaction, then whatever causal powers we ascribe to higher - order composite entities must ultimately be realized by these most basic physical interactions. If this is true, then to claim that the cause of some state or event arises at an emergent higher - order level is redundant. If all higher - order causal interactions are between objects constituted by relationships among these ultimate building blocks of matter, then assigning causal power to various higher - order relations is to do redundant bookkeeping. It’s all just quarks and gluons — or pick your favorite ultimate smallest unit — and everything else is a gloss or descriptive simplification of what goes on at that level. As Jerry Fodor describes it, Kim’s challenge to emergentists is: “why is there anything except physics?” 16

The concept at the center of this critique has been a core issue for emergentism since the British emergentists’ first efforts to precisely articulate it. This is the concept of supervenience...

Effectively, Kim’s critique utilizes one of the principal guidelines for mereological analysis: defining parts and wholes in such a way as to exclude the possibility of double - counting. Carefully mapping all causal powers to distinctive non - overlapping parts of things leaves no room to find them uniquely emergent in aggregates of these parts, no matter how they are organized...

Terrance Deacon - Incomplete Nature

[But there is a powerful argument against mereological substance metaphysics: such discrete parts only appear at the quantum scale through large scale statistical smoothing. In many cases, fundamental parts with static properties don't seem to exist and even those that are put forth can form into new, fundamental entities (e.g., Humphrey's notion of fusion).]

This is not meant to suggest that we should appeal to quantum strangeness in order to explain emergent properties, nor would I suggest that we draw quantum implications for processes at human scales. However, it does reflect a problem with simple mereological accounts of matter and causality that is relevant to the problem of emergence.

A straightforward framing of this challenge to a mereological conception of emergence is provided by the cognitive scientist and philosopher Mark Bickhard. His response to this critique of emergence is that the substance metaphysics assumption requires that at base, “particles participate in organization, but do not themselves have organization.” But, he argues, point particles without organization do not exist (and in any case would lead to other absurd consequences) because real particles are the somewhat indeterminate loci of inherently oscillatory quantum fields. These are irreducibly processlike and thus are by definition organized. But if process organization is the irreducible source of the causal properties at this level, then it “cannot be delegitimated as a potential locus of causal power without eliminating causality from the world.” 20 It follows that if the organization of a process is the fundamental source of its causal power, then fundamental reorganizations of process, at whatever level this occurs, should be associated with a reorganization of causal power as well.

Terrance Deacon - Incomplete Nature

The problem though, is that the old issue of the One and the Many rears its head here. If everything is a process, in virtue of what is anything also a discrete thing? How is anything any thing at all? Process metaphysics tends towards a singular universal monoprocess.

Anyhow, these sorts of questions remain important to a number areas in science. Science isn't presuppositionless. In many areas, it has tended to carry on with a 19th century metaphysics of "everything is little balls of stuff touching and arranged such and such." I used to think this was just inertia, that this view stuck around (with children continuing to be indoctrinated in it for the first decades of their lives) merely because it was "good enough." However, I have come around to the conclusion that such a metaphysics is still embraced, despite good evidence to the contrary (and it no longer being popular in physics itself) because it helps to support a number of ethical and political positions, and "personal philosophies" popular in the academy/middle class (philosophies which fulfill something like the role of religion for their adherents). The old metaphysics makes the world either properly absurd for existentialist or properly inscrutable for both volanturist theology and a "pragmatic" hedonism. It makes man's telos inaccessible/non-existent ("science says this"), which is useful for liberal political theory, since it justifies entirely privatizing concerns about ultimate goods.

Every age has its own dogmas and older eras helpfully shed light on them while suggesting alternative paths. -

"Substance" in Philosophical Discourse

Sometimes. At times, theoretical work needs to take a more philosophical look at what is mean by change and motion, and so "process." This comes up a lot in work on time. I really like Richard Arthur's "The Reality of Time Flow: Local Becoming in Modern Physics," which spends a lot of time defining process.

Some physicists, like David Bohm, carry out these sorts of primitive analyses (another example would be similarity and difference).

The soul is just the form by which living things are the sort of self-organizing, self-determining, self-generating proper wholes that they are. Some (philosophical) conceptions of science do away with any real distinction between living and non-living things (e.g. "everything is just collocations of atoms"), but most do not. "Soul" is broadly consistent with those that do not, and include some sort of principle of life. "Soul" is another one of those terms with tons of baggage though. Hardly any scientist is going to use "soul" because it tends to get associated with some sort of ontological dualism due to later uses, or, because the soul is said to be "immaterial" this is taken to mean something like "existing in a discrete spirit realm," instead of simply "being act/form." -

"Substance" in Philosophical Discourse

Yes, that's a provisional definition. Sach's translation/commentary, which is fairly widely used, is quoted in the post you are quoting from:

Aristotle identifies nature as an "innate impulse of change" that not only sets things in motion but governs the course of those motions and brings them to rest. Only certain things have such inner sources of motion. A tentative list of natural beings is given in the first sentence of Book II, but it is corrected in the second paragraph. The parts of animals are not independent things, so while blood, say, or bone is natural, neither of them is that to which an inner source of motion belongs primarily, in virtue of itself. It is only the whole animal that has a nature, or a whole plant. Similarly, fire cannot properly be said to have a nature, since it is incapable of being a whole [though is can be said to be "natural"]. Like blood and bone, fire, along with earth, air, and water, is only part of the whole being that has a nature.The ordered whole of the cosmos is the one independent thing in nature that is not an animal or plant.

I bolded the relevant part this time. This distinction is developed throughout the corpus. Aristotle is here begining with two prior definitions of nature. Things "are what they are made of," or "things are their form." He will, in a sense, reject both of these to some degree, while retaining elements of them.

"Man generates man," a bed does not generate a bed, but neither does a rock generate a rock. Some nonliving phenomena are more or less self-organizing, but Aristotle was not particularly familiar with these. These aren't really a challenge to his thought though, because it doesn't suppose a binary distinction.

Of course, Aristotle does have a distinction between artifacts and non-artifacts. Fire acts according to a prior actuality. Then again, so does a bronze ball, which rolls (moves/acts) on account of its artificial form, not on account of being made of bronze.

Here is a similar example: Aristotle offers "two-legged" as a definition of man in a number of places (e.g. the Categories , the Metaphysics). This does not mean he thinks this is a good definition of man or that the statement of the definition is the final word on the matter. Rocks possessing principles of motion and generation in the same way that things with souls do leads towards the caricature of Aristotlian physics as a sort of naive animism. -

What is real? How do we know what is real?

What we discussed in that thread isn't Aristotle's answer to the question Wittgenstein took up, just an ancillary point that the positive skeptic's position is self-undermining. -

What is real? How do we know what is real?

You seemed to think the conclusion of his argument is skepticism

No, Kripke is driven to a "skeptical solution" (his term) which learns to live with the paradox, as opposed to a "straight solution" which dissolves the paradox. Quine is similarly led to several skeptical solutions by arguments from underdetermination. My point is that people used to think perfectly good straight solutions to these arguments existed. This is because they had a different anthropology and understanding of rationality, different epistemic presuppositions about what could be used as evidence in philosophical argument, and different metaphysical presuppositions.

Which starting points are more correct is a complex question. My point is merely that the need for skeptical solutions doesn't come from some space of presuppositionless thought. It becomes acute in the 20th century in the analytic tradition because of certain presuppositions. Continentals often reject these, although it seems they are also often quite happy to give Anglo-Americans "the rope they use to hang themselves with" on these points.

Wittgenstein's theory of hinge propositions in On Certainty might also be considered a skeptical solution. Wittgenstein is unknowingly retreading the ground of Aristotle's Posterior Analytics re "justification must end somewhere," and Aristotle himself suggests this is an old problem by the time he is writing about it.