Comments

-

Debate Discussion: "The content of belief is propositional".It seems that I am the only one around here who finds the bottom set to be more accurate and/or acceptable than the first. — creativesoul

Accuracy with respect to what? All I can say is that the most accurate report of someone’s belief at time t1 is the one that best matches the point of view of the believer at time t1. Why would I pick the point of view of some person P at time t2 (or some other person Q at time t1) as a criterium of accuracy for reporting P's belief at time t1? -

Debate Discussion: "The content of belief is propositional".

> "Something" that is shared by different sentences is too vague. […] If not, then how can we say that different sentences share things?

Right. But I left it vague on purpose b/c otherwise I should have taken position wrt what propositions are, which is not my intention. Yet a major intuition pump that is inspiring the philosophical theory of propositions lies in that kind of examples I provided.

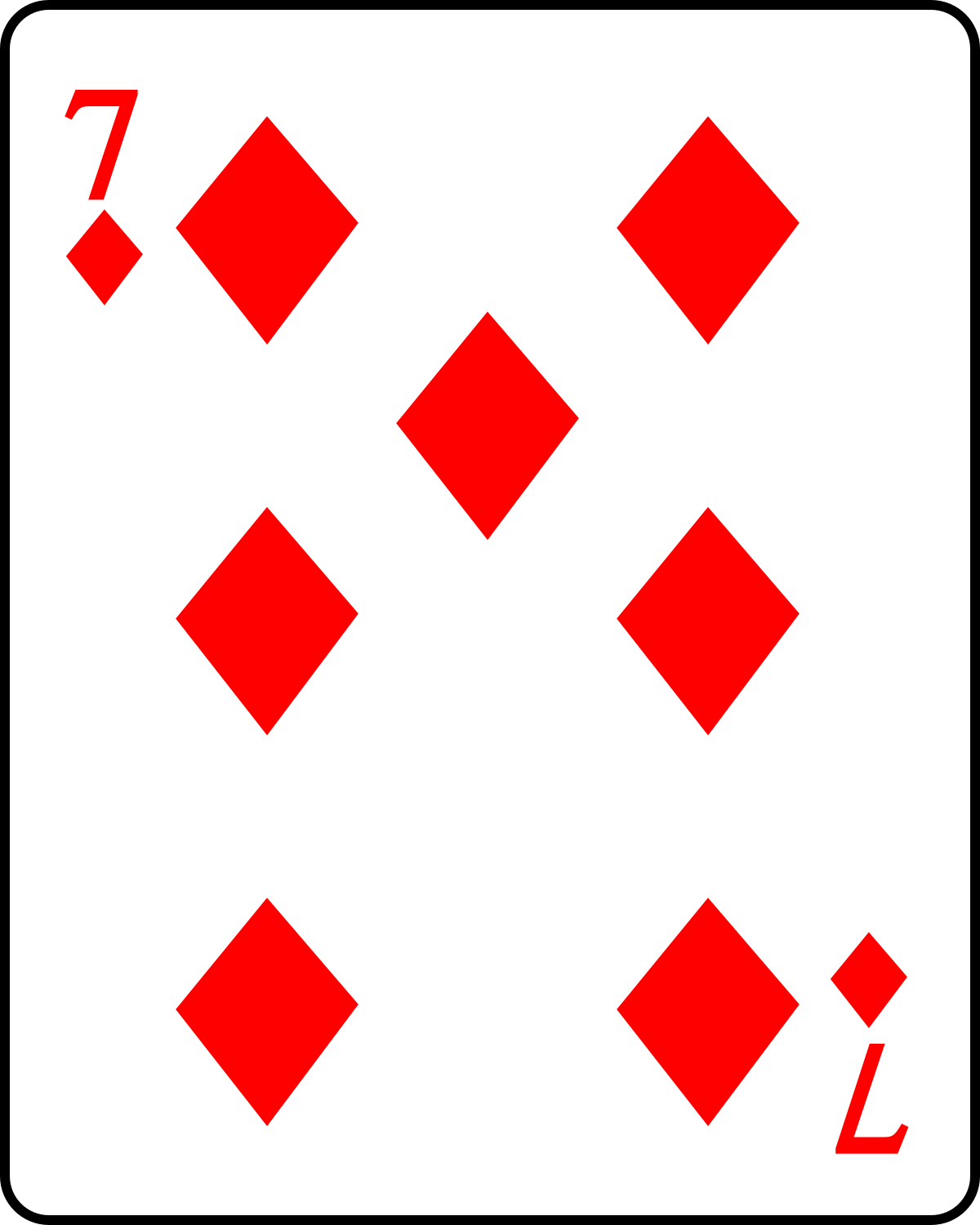

> So it isn't likely that someone just created a 7 of diamonds card without also creating the rest of the deck, hence the 7 of diamonds is only meaningful with the rest of the deck. With that I can agree, but it still is possible for someone to find a card with the number 7 and 7 diamonds on it that has never seen playing cards.

Your last point is going back to where we started: images (taken as a representational kind of things) can match different descriptions that do not share the same proposition. Then, if you remember, you asked me “what rules would we need to remove the ambiguity of images that are not scribbles?”. So, I proposed you to consider the codification systems that we have to interpret images (traffic signs, deck of cards, national flags, emoticons, brand logos, etc.). These codification rules are certainly helping us identify and understand images, but the issue at hand is more specific: can they help us determine the right propositional content of an image? I’m inclined to think that the correct answer is no. Unless, say, images are trivially coupled with sentences by stipulation (but what if the problem is deeper than this?).

> How would they go about determining the meaning of the card?

Good question, but your question should be more demanding than this, and look for a meaning that has an intrinsic propositional form (that sentences can share etc.). So the question should be: how would they go about determining themeaningpropositional content of the card? -

Debate Discussion: "The content of belief is propositional".

> What do you mean by "propositional content"? What are you pointing at when you use the string of scribbles, "propositional content”?

I take it to mean, something that at least can be shared by different sentences (e.g. “Jim loves Alice” and “that guy called Jim loves Alice” ), by different propositional attitudes (e.g. I believe that Jim loves Alice, I hope that Jim loves Alice), by different languages (e.g. “Jim loves Alice” and “Jim aime Alice”) and determines their usage/fitness conditions. Those who theorize about propositions have richer answers than this of course (e.g. Frege’s propositions, Russell’s propositions, unstructured propositions, etc.). But I’m not a fan of these theories, so I’ll let others do the job.

Anyways, I hear people wondering about images as propositions or as having propositional content, without elaborating or clarifying, so this was my piece of brainstorming about this subject.

> You seem to be confusing the card with the deck. I don't need to know it's relationship with other things to know that it is a sheet of paper with red ink in shape of diamonds and a “7".

To know that I’m confusing the propositional content of that image, presupposes that you know what the propositional content of that image is. But I’m not convinced it’s that simple, see what you just wrote about that image: <it is a sheet of paper with red ink in shape of diamonds and a “7”> while you previously wrote something like: <it’s a seven of diamonds >. Is it essential for the propositional content of that image the mention of ink or paper? A seven of diamonds tattooed on the the body doesn’t share the same propositional content of the image on paper? How about the arrangement of the diamonds on the surface of the card? How about the shade of red? How about the change of light condition under which the image is seen? If I warped that image with an image editor to make it hardly recognisable but still recognisable after some time as a 7 of diamonds, shouldn’t we include in the propositional content of that image all the features that allowed me to recognise it as a 7 of diamonds, despite the warping? And so on…

Again, I’m just brainstorming, so no strong opinion on any of that. Indeed I was hoping to get some feedback from those who talk about propositional content of images, or images as propositions. -

Debate Discussion: "The content of belief is propositional".

Fine with me, I don’t want to waste your time and energies. And you already have many other interlocutors. In any case, I'm more playful than you might think. Just I can play it tougher depending on other peoples' replies. -

Debate Discussion: "The content of belief is propositional".but only after you learned that is what the scribbles are labeled as. I've been using the term scribble, not word, because they are scribbles without rules and words when rules are applied to scribbles. — Harry Hindu

Agreed, indeed I was backing up the part where you wrote “meaning that words (as an image of strings of scribbles)”

Isn't it a seven of diamonds regardless of what card game that we are playing? We don't even need a game to define the image as a seven of diamonds, because we have rules about what scribble refers to which shapes (diamonds, spades, hearts, or clubs). — Harry Hindu

Maybe regardless of any specific card game, but the challenge here is to express the propositional content of that image (something that an image can share with sentences, different propositional attitudes, different languages): so is the propositional content of that image rendered by “this is a seven of diamonds” or “this is a seven of diamonds in standard 52-card deck” or “this is a card of diamonds different from a 1 to 6 or 8 to 13 of diamonds” or “this is a seven of a suit different from clubs, hearts, spades” or “this is a card with seven red diamond-shaped figures and red shaped number seven arranged so and so” or any combination of these propositions? All of them are different propositions which one is the right one? BTW “this” is an indexical, and shouldn’t be part of the content of an unambiguous proposition: so maybe the propositional content is “something is a seven of diamonds” or “some image is a seven of diamonds”? And so on.

At least this is how I understand the philosophical task of proving that images have propositional content, but I'm neither sure that others understand this philosophical task in the same way I just drafted, nor that this task can be accomplished successfully. -

Debate Discussion: "The content of belief is propositional".By definition, a broken clock doesn't work, so your proposition makes no sense. — Olivier5

Of course, but if you follow my exchange with Creative Soul with due attention, you should understand why I made it up. That crazy sentence is the result of some unjustified propositional calculus that I applied to the belief ascription rendering "Jack believes that broken clock is working" (proposed by CreativeSoul). Why did I do that? To show CreativeSoul that my unjustified propositional calculus is very much the same type of propositional calculus CreativeSoul used to justify his belief ascription rendering (e.g. "Jack believes that broken clock is working") -

Debate Discussion: "The content of belief is propositional".

> Rather than propose something I've not,

Oh really? This is what you wrote: “Can Jack look at a broken clock? Surely. Can Jack believe what the clock says? Surely. Why then, can he not believe that a broken clock is working?”.

To obtain “Jack believes that broken clock was working” you simply replaced the term “broken clock” from “Jack looks at a broken clock” with the term “the clock” from “Jack believe what the clock says”. This is a substitution operation applied to two propositions (one reporting a belief ascription), to obtain a third proposition (reporting a belief ascription) based on the sheer co-reference of some terms involved. That is why I call it propositional calculus. Indeed a propositional calculus that is supposed to work independently from any other pragmatic and contextual considerations. Hence: you proposed something by applying some propositional calculus that I find quite preposterous.

Since you didn’t perceive how preposterous your argumentative approach is, then I gave you another case where your type of reasoning (i.e. propositional calculus applied to belief ascriptions, based on sheer co-reference, and indifferent to any pragmatic/contextual considerations) looks more evidently preposterous: if one can render “S did/did not believed that p” as “p and S did/did not believe it” and vice versa, and one can take p="that broken clock was working”, why can’t I justifiably render “Jack did believe that broken clock was working” as “that broken clock was working and Jack did believe it”?

> would it not just be easier to answer the question following from the simple understanding set out with common language use?

That’s what I and others did, unless you think you are a more competent speaker than all of those who objected your rendering, you should take this as a linguistic datum and infer that your account is not that common language usage, after all. And indeed you did that already when you claimed to be questioning the “conventional” belief account.

Let me repeat once more: I don’t feel intellectually compelled to answer questions based on preposterous assumptions, like this one:“Can Jack look at a broken clock? Surely. Can Jack believe what the clock says? Surely. Why then, can he not believe that a broken clock is working?”. But I can certainly show you why I find them preposterous (which I did). BTW, as far as I read from your posts [1], this is the only argument you made to justify your belief ascription rendering (besides your thought experiment with a fictional character that — surprise surprise — agrees with you!).

Anyways, I now question this justification not simply because its conclusion is wrong (which is), but also because itself is flawed by design (even if your conclusion was correct)!

> Do you not find it odd that Jack would agree, if and when he figured out that the clock was broken?

Seriously?! By “Jack” you mean a fictional character in a story that you just invented? Oh no, that’s not odd at all, it would be indeed much more odd if you invented stories where fictional characters explicitly contradict your theories, and despite that you used those stories to prove your theory.

OK let me help you with your case. Indeed, I think there might be a way out for you but only if you reject this line of reasoning: “Can Jack look at a broken clock? Surely. Can Jack believe what the clock says? Surely. Why then, can he not believe that a broken clock is working?” (along with the idea that de re belief ascriptions are appropriate independently from pragmatic and contextual considerations, or a better rendering than de dicto belief ascriptions). Indeed if you rejected that line of reasoning, then you could explain the situation in your thought experiment based on pragmatic considerations and shared assumptions, much better. How? Here you go: since at moment t2, you and Jack share the same assumptions about the reliability of that clock, the belief of Jack about that clock at t1, and the rationality of you and Jack, then between you two it would be easier to disambiguate the claim “Jack believed that broken clock was working”, and this is why you two would not find it so problematic to use that belief ascription (BTW that is also why we can't exclude a non-literal or ironic reading of this belief ascription either). However, as soon as we add to the story another interlocutor who doesn’t share all the same assumptions relevant to disambiguate “Jack believed that broken clock was working” then this rendering would be again inappropriate or less appropriate than de dicto rendering “Jack believed that clock was working”.

> Interesting thing here to me is that on the one hand you're railing against propositional calculus(as you call it), and yet again on the other your unknowingly objecting based upon the fact that Jack would not assent to his own belief if it were put into propositional form and he was asked if he believed the statement. At least, not while he still believed it.

There are 2 problems in your comment:

- It can be misleading to claim that I’m “railing against propositional calculus”. I’m more precisely railing about the propositional calculus you applied to belief ascription rendering in order to justify the claim that “Jack believes that broken clock is working” is not only fine independently from any pragmatic and contextual considerations, but even better than the de dicto rendering “Jack believes that clock is working”.

- I didn’t make the claim you denounce here “your unknowingly objecting based upon the fact that Jack would not assent to his own belief if it were put into propositional form and he was asked if he believed the statement.” (ironically, you were the one repeatedly suggesting me to stick to what you write), nor my line of reasoning requires the claim “Jack would not assent to his own belief if it were put into propositional form and he was asked if he believed the statement. At least, not while he still believed it.” to be true, independently from pragmatic and contextual considerations (see the way out I suggested you previously).

[1] If you have others and can provide links, I’d like to read them. -

Debate Discussion: "The content of belief is propositional".Do you agree that in the Russell and Gettier cases that the belief was properly accounted for? — creativesoul

I don't see them as presupposing a specific account of belief as such, in their treatment of JTB. They are reasoning about the idea that JTB (formulated in some way) provides all necessary and sufficient conditions to have a case of knowledge. -

Debate Discussion: "The content of belief is propositional".You agreed with what I wrote — creativesoul

Agreed? In what sense? Where? Can you quote where I agree with you? I also said, let's pretend etc.

changed that, and then denounced the change — creativesoul

And this is just one part of the reasoning, where is the rest?

If you wish to see how they could be rendered similarly...

It was raining outside and I did not believe it. The clock was broken, and I did not believe it. — creativesoul

No sir. the problem I have is with "Jack believed that a broken clock was working" since your are insisting on it.

You came up with this rendering based on the propositional calculus suggested here: “Can Jack look at a broken clock? Surely. Can Jack believe what the clock says? Surely. Why then, can he not believe that a broken clock is working?”.

So I proposed you the following propositional calculus: if one can render “I did/did not believed that p” as “p and I did/did not believe it” and vice versa. And asked you: why can’t we do the same with p="a broken clock was working" [1]?

So I'm challenging you to explain why your propositional calculus is correct, and mine is wrong based on your own assumptions. This is the problem you should address, hopefully in a non ad-hoc way.

[1] I re-edited because the value of p that I had in mind was "a broken clock was working" but by copy-and-pasting I made a mistake. -

Debate Discussion: "The content of belief is propositional".@Harry Hindu

> If you are agreeing with me that strings of scribbles is an image then there could be many descriptions that could correspond to the same image of strings of scribbles, meaning that words (as an image of strings of scribbles) would be subject to the same ambiguity that you are ascribing to images that are not scribbles.

Yep, this is correct if we take strings of characters, independently from any pre-defined linguistic codification. The difference is that with words (notice that the term “word” is already framing its referent, like an image, as a linguistic entity!) we readily have different codified systems of linguistic rules that help us identify the propositional content of declarative sentences and solve ambiguities internal to that practice.

> I asked you what rules would we need to remove the ambiguity of images that are not scribbles?

You can have all kinds of sets of rules (e.g. the codification of traffic signs). Concerning the problem at hand, one thing that really matters is to understand if/what systems of visual codifications disambiguate an image always wrt a specific proposition: think about the codified images of a deck of cards. Does e.g. the following card have a propositional content that card game rules can help us identify? What would this be?

-

Debate Discussion: "The content of belief is propositional".What's your view regarding Russell's clock, Gettier's cases, and Moore's paradox? — creativesoul

Not sure about it, also because knowledge is a wider issue. What I can say now is that, concerning belief ascription practices, I'm strongly against a "propositional calculus" kind of approach. -

Debate Discussion: "The content of belief is propositional".If we say that Jack believes of that broken clock that it is working, what is the content of Jack's belief, and what is Jack's belief about? — creativesoul

As I said, this is the kind of de re belief ascription that we can use when we are not sure about a de dicto belief ascription (i.e. we don’t know what someone else’s beliefs are really about, see the case of the kid in the park). In the case of Jack, I would prefer that form of rendering, if e.g. I’m not sure whether Jack is holding contradictory beliefs or he simply ignores that that clock is not working. Certainly, if I knew that Jack ignores that clock is not working, I would prefer to say “Jack believes that clock is working” or “Jack mistakenly believes that clock is working” instead of “Jack believes of that broken clock that is working”, or worse, “Jack believes that broken clock is working”.

Now imagine another case: Jack and everybody else believes that clock is working, except me who hacked the clock to show whatever time I wanted it to show. If I decided to confess this to everybody, would I still say “you all guys believe of that broken clock that is working”? Nope, because given everybody else’s default understanding of the situation (the shared assumptions), people would reply “what?! That clock?!” being unsure that I’m referring to the same clock or what exactly I’m claiming about that clock, etc. (i.e. what shared assumption they need to revise). So what I would prefer to say, is “you all guys believe that clock is working, but you are wrong”.

Now imagine another case: I and Jim hacked the clock, so we both know that is not working, but Jim doesn’t know if Jack was told about the hack, what could I say to assure him? I could say indifferently “Jack believes that broken clock is working” or “Jack believes of that broken clock that is working” sure that - given our shared assumptions about the clock and Jack’s rationality - Jim wouldn’t possibly interpret my belief ascription as de dicto. Unless, of course, Jim has a philosophical attitude and will start questioning me about it! -

Debate Discussion: "The content of belief is propositional".I write something that you agree with. You change what I write. You disagree with and denounce the change, not what I wrote. Evidently, you cannot see. — creativesoul

All right sir, let’s talk about what I did and why I did it.

First of all, I already made my objections to your theoretical assumptions wrt a more common understanding of belief ascriptions (as others did). Those objections still hold, independently from the following additional remarks.

Secondly, this time I tried something different, namely I’m questioning the internal coherence of your theoretical approach on its own (de)merit. How?

Let’s recapitulate:

- Once you wrote: “Can Jack look at a broken clock? Surely. Can Jack believe what the clock says? Surely. Why then, can he not believe that a broken clock is working?”. What this line of reasoning shows to me is that the prospect of some propositional operation based on sheer co-reference, indifferent to any contextual pragmatic considerations, is enough for you to do your propositional math accordingly and grant legitimacy to the resulting belief ascription “Jack believes that a broken clock is working”.

- In a more recent comment you wrote: “there's nothing at all stopping us from admitting that it was once raining outside and we did not believe it, or that we once believed a broken clock was working”. This shows that you take the admission “that we once believed a broken clock was working” at least as plausible as the admission that “it was once raining outside and we did not believe it”.

Now to my argument: if we pretend that both these 2 points hold, then at the prospect of some propositional operation based on sheer co-reference that I spotted, I too did my propositional math accordingly in order to show you its dumb result.

Of course, you too disapprove of such a dumb propositional math, otherwise you would try to defend it. The problem however is: can you explain why your propositional math is acceptable while mine isn’t, based on your own assumptions? Again, if I can plausibly render “we did not believe that it was once raining outside” as “it was once raining outside and we did not believe it” based on sheer co-reference, why can’t we plausibly render “we once believed a broken clock was working” as “a broken clock was working and we once believed it” ? Or to put it into more formal terms: if one can render “I did/did not believed that p” as “p and I did/did not believe it” and vice versa, why can’t we do the same with your type of belief ascriptions?

If you can not provide an explanation on that case that is coherent with your own assumptions and doesn’t look ad-hoc, then your theoretical approach appears incoherent and your propositional math as dumb as mine. In other words, we have one more reason to question your theoretical approach along with what results out of it (your rendering of belief ascriptions).

Get it now? -

Debate Discussion: "The content of belief is propositional".Great job of denouncing shit that I've not written. — creativesoul

What do you mean? I just quoted verbatim the shit you wrote. Did you change it again? -

Debate Discussion: "The content of belief is propositional".

mmmkeyInteresting how different your account of my position is from what I've argued here. — creativesoul

And what does "My claim was that JTB was the basis of the rendering" is supposed to mean? -

Debate Discussion: "The content of belief is propositional".Great job denouncing shit that I've not said. — creativesoul

All right, as I wrote in the P.S. you re-edited the text, after I picked it up. I realised it too late. Apologies, sir. Let me repay you by denouncing the shit that you wrote (unless you change it again):

there's nothing at all stopping us from admitting that it was once raining outside and we did not believe it, or that we once believed a broken clock was working, — creativesoul

Now, admitting that it was once raining outside and we did not believe it, makes sense. While admitting that we once believed a broken clock was working, still looks problematic and a way to see it is by rendering it in the same form as the former statement: once a broken clock was working and I did not believe it. Does it make sense? Hell, no. -

Debate Discussion: "The content of belief is propositional".Plato is perhaps best attributed with the original conception of JTB. Nonetheless, JTB presupposes belief as propositional attitude, as you yourself have acknowledged. My claim was that JTB was the basis of the rendering. — creativesoul

You claimed that JTB was the basis of belief as propositional attitude. I took you to mean either that the notion of belief as propositional attitude is grounded on the notion of knowledge as JTB, and this is false, because it's at best the opposite. Or that the contemporary debate on belief as propositional is originally inspired by the debate between Russell, Moore and Gettier over the notion of knowledge as JTB. But that's not true b/c the contemporary debate about belief as propositional attitude was heavily inspired by Frege "Sense and Reference" which doesn't address the notion and the problems of knowledge as JTB. That is why I asked you to give me something else to support your claim, which it seems you tried to do, but I don't understand what you mean. -

Debate Discussion: "The content of belief is propositional".@creativesoul

> However, after becoming aware of our error, there's nothing at all stopping us from admitting that it was raining outside and we did not believe it, or that we believed a broken clock was working.

Still, I don’t see anything problematic in the claim “that it was raining outside and we did not believe it”, while “that we believed a broken clock was working” still looks problematic. If you tried to put the second claim into the same form of the former, you would obtain: that broken clock was working and I didn’t believe it. Does it make sense? Hell, no.

P.S. you re-edited your post, fine. But my comment still holds -

Debate Discussion: "The content of belief is propositional".@Harry Hindu

> Here we are talking past each other again. In 1 and 2 you are talking about the some string of scribbles (descriptive sentences that do not share the same proposition). You're talking about words, not images. You're explaining how words, not images, are ambiguous.

No, I’m talking about images. Images are visual entities like strings of letters written on a paper, yet we can take images and strings to represent something (again intentionality is a presupposition here for understanding images and textual strings as representational). If we were to describe with sentences what images can represent, we would notice that there can be many descriptions that could correspond to the same image (this is particularly evident in the case of so called “ambiguous images” - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ambiguous_image), yet they do not share the same proposition. And so on with the other remarks I made. Don’t forget that my brainstorming was about the propositional nature of images.

> Huh? How is it false?

That’s basic propositional calculus (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Conditional_proof): if you claim that conditional that I reported in the previous comment, it can not be true that the consequent is false and the antecedent is true. I gave an unquestionable counter-example to prove the falsity of the consequent, so the antecedent must be false.

> I also said that you can translate different words in the same language (synonyms).

Besides the fact that synonymity is grounded on semantics, while passive and active forms are grounded on syntax, the point is that translation has to take into account all the relevant semiotic dimensions of a text for a proper translation, and the co-reference to the same state of affairs is only one semiotic dimension.

> What else would belief include if not just experience and episodic memory?

To my terminology, experience includes perception, memory, imagination. Belief can not be reduced to experience. Belief is a cognitive attitude based on experience or other beliefs.

> In the moment of your dream, you are remembering what is happening and therefore believing it is happening. What happened in the beginning of the dream is useful to remember in the middle of the dream, or else how would you know you're still in the same dream?

After you wake up you still have the memories because they were stored when you were believing, not when you aren't. Because they aren't useful memories they will eventually be forgotten.

I don’t follow you here: first it seems to me you are talking about different types of memory (working and episodic memory) and I don’t know if you are taking this in due account, secondly your statements concern empirical regularities (while I’m more interested in broadly logic analysis and reasoning), thirdly they do not seem to be always true (I doubt that while dreaming at any given time I know that I am in the same dream, also because normally I’m not aware of dreaming when I dream), forth you talk about usefulness which is a term to be clarified and then empirically proved.

In conclusion, I’m not sure how to understand your claim, if I understood it, it doesn’t seem to be right, and even if you were right, I don’t know what to do with it.

> What is logic if not the manipulation, or the processing, of symbols?

This seems again an identity claim, but I wouldn’t talk about logic as identical to manipulation or symbolic processing. However, I’m not going to open another front of contention, before converging on the many ones that we already have at hand. -

Debate Discussion: "The content of belief is propositional".@Harry Hindu

> In what way are images suppose to be ambiguous? The only images and words that are suppose to be ambiguous is art.

My point was that images are ambiguous in 2 senses: 1. they can match different descriptive sentences that do no share the same proposition. 2. Propositions - differently from sentences - are supposed to be unambiguous, however images can be not only ambiguous but also be ambiguous in ways that no descriptive sentence can render (image ambiguity does not match sentence ambiguity).

These observations are relevant b/c if we are supposed to take propositions as correlates that different sentences, different languages, different propositional attitude can share, we can wonder if propositions can be shared across different media (images vs linguistic expressions)

> When I say "how it is said", I'm referring to the scribbles used. Using different scribbles to say the same thing is saying the same thing differently.

OK let’s start again. I remember you claiming “When translating languages, that is what is translated - the state-of-affairs the scribbles refer to”. Now, I understand your comment as implying the truth of the following conditional: if translation consists in replacing statements from at least 2 different languages co-referring the same state-of-affairs, then the French translations (I provided in my example) could translate the English sentences indifferently, because they all are referring to the same state of affaires (at least to me). But the consequent of that conditional is false, so it should be false also the conditional.

> I'm not clear of where we are agreeing or disagreeing here.

My central claim is that semantic relations can not be reduced to sequences of mind-independent causal chains. You seem to do the same (due to the relevance of the notion of “mind” in your argument), but you are also developing your discourse over aspects that simply widen the scope of that central claim (e.g. with the reference to art works), which is fine but I'm more interested in arguments that support or question the claim: semantic correlations (between sign and referent) can not be reduced to causal chains. To support that central claim, one could for example argue that while art works are ambiguous in some sense, any causal chain involved in the intentional production/experience/understanding of a piece of art work can not be qualified as "ambiguous". While to question that main claim one could argue that indeed ambiguity can be reduced to some probabilistic feature of causal chains involving psychological states, etc.

In any case, I'm not interested to deal with this specific task in this thread. So I'll leave it at that.

> It's not useful to remember/believe that you dream, or to remember/believe you know the difference between dream and reality?

In your past comment, you wrote “The act of memorizing an experience is the act of believing it”. This looks as an identity claim to me, and I don’t support such identity claim. For me belief exceeds both experience and episodic memory. Maybe you wanted to say that an act of memorizing a given experience always results from believing in that experience. Even if this was true, it would be just an empirical fact, namely something that doesn’t exclude the logical possibility of believing a given experience without memorizing it and memorizing a given experience without believing in that experience. Besides there are actual counter-examples: I remember a dream but I do not believe in that dream, I do not take whatever seemed to happen in that dream to be the case. Maybe you want to claim that while dreaming I was believing whatever was experiencing, and that resulted in me memorizing it. But that we believe in our dreams while dreaming can be acknowledged for all our most common dreams, yet we do not seem to remember all of them either.

The correlation between usefulness, memory, experience and belief you are pointing at, again looks empirical to me, not logical (which is the part I’m more interested in), and even more slippery because what counts as useful is no less controversial than what counts as memory, experience, and belief. -

Debate Discussion: "The content of belief is propositional".@creativesoul

> There is a common practice of personifying animals. If we follow your advice here, anthropomorphism is acceptable.

Not necessarily. First of all, I find acceptable as a linguistic datum the cases that you may qualify as anthropomorphic along with those that you do not qualify as anthropomorphic based on your assumptions, precisely to assess your own assumptions. Secondly, belief attribution practices evolve over time, so we can’t ignore this fact either, and I don’t assume that they do it arbitrarily.

> What I'm saying is that some belief existed in it's entirety prior to our talking about it, and as such, our common practices could very well be wrong, particularly regarding language less ones as well as ones that are formed and/or held prior to thinking about them as a subject matter in their own right.

One way to revise the practice is to fix ambiguities/indeterminacies internal to the practice itself (here the need to distinguish e.g. different logical functions of “to be”). Your approach about belief ascriptions however doesn’t seem to solve ambiguities/indeterminacies of ordinary belief ascriptions, instead - depending on the pragmatic context - introduces them as I already argued.

> My aim currently is to shine a bit of much needed light upon the current failings of our accounting practices. Russell's clock, both Gettier cases, and Moore's paradox all stem from belief as propositional attitude.

Not sure how I am supposed to understand such a claim. Also because I’m not sure that Russell, Moore, Gettier, and you share the same idea of “belief as propositional attitude”, nor that their arguments rely on a specific way of understanding “belief as propositional attitude”. Anyways, how can your way of understanding belief ascriptions “shine a bit of much needed light upon” these three cases? If you explained it already elsewhere and can provide the links, I’m willing to read it of course.

> My attitude towards your position is clear befuddlement. It is about as preposterous as it can be for us to deny that it is possible to believe that a broken clock is working, or object to the reporting of that simply because your accounting practice cannot make sense of it, because not only is it possible to believe that a broken clock is working, it happens on a regular basis to someone... somewhere. It's happened to me.

Sure, you are right, if you frame the problem in the way you believe it should be handled, how on earth can I possibly question it? Unfortunately it’s just a sophism.

Besides since the question for me, it’s not if it is possible, but under what conditions it is permissible to make such claims, there is a way I could make sense of it, after all. And I also told you that in this case, to avoid ambiguities, instead of saying “Jack believes that a broken clock is working” I would say “Jack believes of that broken clock that is working”, is there any substantial reason why you wouldn’t?

> Then I suggest you peruse the last couple of weeks worth of posts by yours truly here in this thread, because you seem to have either ignored or missed the arguments that have been given.

And I suggest you to do the same, because I addressed many of them when they were available.

But in the following comment I couldn’t find any, unless you consider emoticons as arguments:

...the JTB analysis of "knowledge" challenged by Gettier presupposes (or so it seems) the notion of "belief" as propositional attitude not the other way around. So, unless you have something more convincing to support your claim ("JTB is the basis for belief as propositional attitude"), b/c that is what I asked, then it is fair to say that you are completely wrong

:meh: — creativesoul

> I too prefer arguments to rhetoric, handwaving, and gratuitous assertions. So far, you've offered the latter three [1]. Got any of the former?

I wish I could help, but unfortunately, I don’t take emoticons to be arguments. Sorry.

[1]

Maybe you have that impression b/c you are the one to be challenged now. When I was challenging Banno you used to write things like: "I'd be honored to offer my feedback to such a carefully well-crafted post". Not to mention all the moments you agreed with my points against Banno. You even re-used an argument I made against Banno without mentioning me.Indeed this is what I already — neomaccreativesoul

If "The present King of France is bald" is not a proposition, and yet it can be believed nonetheless, then it cannot be the case that either all belief has propositional content or all belief is an attitude towards some proposition or other. — creativesoul

Indeed this is what I already remarked in my previous comment:

You mean your pointless challenge: " If there are beliefs that cannot be presented in propositional form, give us an example".

What about this example: X believes that the present King of France is bald. Did I win anything? — neomac — neomac -

Debate Discussion: "The content of belief is propositional".That is false on it's face.

We learned to use the word "belief" in the context of specific linguistic practices, but those practices were not about belief ascriptions. — creativesoul

I lost you again. It doesn’t really matter how you phrase it based on your questionable philosophical assumptions. All I meant was simply that you as anybody else learned the word “belief” when other speaking people around you were saying things such: I/you/he/she/we/they believe or not believe this or that etc. This is a linguistic fact. There is no possible contention on this. And that, only that, is the point I care making.

So if you are happier to write “We learned to use the word "belief" in the context of specific linguistic practices”, just go for it. The point I made still holds.

We've been using the term belief for thousands of years. We've been attributing beliefs to ourselves and others for at least that long. Some attribute beliefs to the simplest 'minded' of animals, such as slugs.

According to what you've said here, we ought make our theory of belief fit such usage. — creativesoul

Sure, why not? But our practices admit figurative and literal usages, normal and fringe cases, shared and non-shared background beliefs, successful and unsuccessful belief attributions, etc. When you were a kid you learned the word "belief" also in playful contexts and stories about fictional characters, if you had a religious education you also learned the word “belief” as applied to invisible divine beings or disembodied souls, etc.

In any case, I must confess in all honesty that I don’t know and never even heard of any example in any culture in the entire known human history where people learned the word “belief” predominantly as applied to slugs, do you? And if you don't, then this shows not only how weak your objection is, of course, but also an interesting linguistic fact that our theory of belief should take into account!

FYI I prefer arguments to emoticons. -

Debate Discussion: "The content of belief is propositional".I could be wrong, but not completely. — creativesoul

As far as I can tell, Frege published "Sense and reference" in 1892, while Gettier published his "Is Justified True Belief Knowledge?" in 1963, besides the JTB analysis of "knowledge" challenged by Gettier presupposes (or so it seems) the notion of "belief" as propositional attitude not the other way around. So, unless you have something more convincing to support your claim ("JTB is the basis for belief as propositional attitude"), b/c that is what I asked, then it is fair to say that you are completely wrong. -

Debate Discussion: "The content of belief is propositional".What are you ascribing to another prior to having an understanding of belief? — creativesoul

I lost you. I’m talking about your theoretical understanding of the belief ascription practice wrt to the notion of “belief”. A theory of belief should fit into a theory of belief ascription not the other way around, the reason being that you as any body else learned the word “belief” and its proper usage in the context of specific linguistic practices about belief ascriptions, prior to any philosophical debate. So the nature of belief should be such that it makes such a practice possible. Such practices tell us that we can provide de re/de dicto ascriptions, that they are appropriate in some circumstances not in others, that those belief ascriptions guide our understanding and expectations about other people’s behavior, that we can attribute beliefs even to non-linguistic creatures, etc. So based on these practices what can we claim about the nature of belief? That's the philosophical task that makes sense to me. -

Debate Discussion: "The content of belief is propositional".@Harry Hindu (bear with me for the non-standard quotation style)

> Were you asking me to describe the image, or what the image is about?

I was more brainstorming about Agent Smith’s question: “Are pictures/images propositions?”

The problem is that propositions are not supposed to be ambiguous, while images are.

Sentences can be ambiguous, but (not surprisingly) there are rules to systematically disambiguate them wrt to the propositions that they are supposed to represent (at least in the case of declarative sentences), that’s not the case for images.

> So A1 is said differently than B1, but you say that they are translatable and mean the same thing.

Because B1 not only matches with what A1 says (about Alice’s love for Jim) but also with how it is said by A1 (passive form)

> So, it all depends on what the goal of the mind is at any moment (intent).

That is the point I’m making as well: what enables us to single out semantic relations between signs and referents out of a causal chain of events is “a mind” with intentionality. If we talked only in terms of causality and effects, we would end up having a situation where, in a causal chain, any subsequent effect be "a sign of” any preceding cause.

> Imaginary concepts have causal power.

That is a very problematic statement to me: we should clarify the notions of “concept” and “causality” before investigating their relationship. But it’s a heavy task on its own, so I will not engage it in this thread.

> Why remember something that isn't useful? The act of memorizing an experience is the act of believing it so that you may recall it later (use the belief).

Not sure about that: e.g. we may remember things without believing in them (e.g. dreams). To my understanding, belief can interact with experience and memory in many ways, yet the latter cognitive skills come ontogenetically and phylogenetically prior to any doxastic attitude. -

Debate Discussion: "The content of belief is propositional".A sentence is semantically de re just in case it permits substitution of co-designating terms salva veritate. Otherwise, it is semantically de dicto. — creativesoul

All right, but pragmatic considerations should be taken into account to get the full picture of our communicative practices concerning de re/de dicto belief ascriptions (what terms are taken to co-refere, when substitution is allowed, etc.).

Besides also co-reference is matter of belief!

The point of this exercise, on my end anyway, is to show how the consequences of conventional accounting practices are absurd — creativesoul

Well, you are trying to make your belief ascription analysis fit your understanding of belief. For me, it should be the other way around.

Can Jack look at a broken clock? Surely. Can Jack believe what the clock says? Surely. Why then, can he not believe that a broken clock is working? — creativesoul

Simply because belief ascriptions are not based on such a math out-of-context, but on their explanatory power wrt to believers’ behavior in a given context.

BTW, once more, you didn’t clarify why JTB is the basis for belief as propositional attitude. -

Debate Discussion: "The content of belief is propositional".It has everything to do with it, for it is the basis of belief as propositional attitude. — creativesoul

Why? What are the reasons? Where are the arguments to support your claim that JTB is the basis for belief as propositional attitude? I mean, ought we not all do our own work?

Are you of the position that Jack cannot believe that a broken clock is working when he looks at it to find out what time it is? — creativesoul

Yep that would be my presupposition (and not only mine apparently) wrt your hypothetical case. The point is that I’m capable of de dicto/de re rendering/understanding of belief ascriptions as any other competent speaker in the right circumstances and prior to any philosophical debate. Your revisionist approach about this distinction based on your philosophical assumptions still looks unjustified for 2 reasons: 1. de dicto rendering is usually more accurate than de re rendering when we want to explain behavior 2. The success of de re ascriptions is not based on correctness but on shared assumptions between the one who makes the belief ascription and her audience on the situation at hand. If I don’t know enough Jack, I might find appropriate to make a de re ascription like this: Jack believes of that broken clock that is working.

Indeed de re belief ascriptions would still be effective if the shared assumptions were completely wrong: e.g. flat Earth believers could claim of me “he believes that our flat Earth is round” or, better, “he believes of our flat Earth that is round”.

Is that supposed to be clearer and more accurate somehow than just admitting that we can mistakenly believe that a broken clock is working? — creativesoul

Here my answer:

1. My claim is that “Jack believes that the broken clock is working” can be read in 2 ways, de dicto or de re. And de dicto ascription would be preferred over a de re ascription, when possible and based on shared understanding, because it’s more informative, more explanatory of believers’ behavior. But possibility and shareability assessments depend on the contextual assumptions of the involved parties: the one who states the belief ascription and her audience wrt the believer in the situation at hand.

2. The claim that “Jack mistakenly believes that the broken clock is working” out-of-context is more ambiguous about a de re and de dicto reading: with a de dicto reading Jack would simply be irrational (since it’s a contradictory belief), with a de re reading Jack could be either irrational or ignorant about the fact that the clock is not working. In other words, the de dicto belief ascription is more specific than de re belief ascription, therefore - if accurate - more explanatory or useful in guiding our expectations about Jack.

What would be a de dicto rendering of that toddler's belief? I mean, ought we not all do our own work? — creativesoul

Mine was indeed a rhetoric question! The example of the toddler was meant to show a common case where a de re belief ascription makes sense, since we may have at best an approximate idea of what a toddler’s understanding of the situation is (i.e. we would be much less confident in any de dicto belief ascription in this specific case). The same goes for belief ascriptions to animals. The better we understand the believer’s view of the situation, the more we would rely on her understanding of the situation to explain her behavior (or assess her rationality), and share it with others with de dicto belief ascriptions in the appropriate circumstances. -

Debate Discussion: "The content of belief is propositional".There's a difference between a statement and an utterance — Banno

How is this relevant? Instead, give me an example of a proposition, sentence, statement (or whatever else you don't care to distinguish from propositions) that can not be parsed into sequences of electric impulses of different voltage! -

Debate Discussion: "The content of belief is propositional".

Sure and propositions statements sentences (and whatever else you have in your menu) can be parsed in sequences of electric impulses with different electric voltages, therefore - by transitivity - beliefs are attitudes toward sequences of impulses with different electric voltage.Those who are working on these problems accept that beliefs can be parsed as attitudes towards statements, sentences or propositions. — Banno -

Debate Discussion: "The content of belief is propositional"."This is a picture of a duck or a rabbit, depending on how you look at it." The picture would be an example of "ambiguity". — Harry Hindu

That is the problem of putting visual content into propositional form. Images can be ambiguous in a way that is not captured by any related descriptions.

Besides one and the same image can correspond to many possible descriptions, whose number is arguably higher than any limited mind can conceive of.

The point is what you are saying, not how you are saying it. — Harry Hindu

When we translate, we take into account precisely how things are said, otherwise it wouldn’t be a translation.

So you can not use an active form in your native language to translate a foreign sentence in passive form, if you want to translate literally the foreign sentence of course.

That is why, in the examples I listed, B2 is a correct translation of A2, and not of A1, despite the fact that all 3 statements are about the same state of affaires.

I didn't say means are caused. — Harry Hindu

D'oh! I misread your statement. Apologies.

I said meaning is the relationship between cause and effect. (...) What they mean is the relationship between the scribbles existing and what caused them. — Harry Hindu

Still I disagree on this. My conviction is that linguistic meaning presupposes intentionality and intentionality can not be understood in causal terms for several reasons.

Here I limit myself to 3 and will leave it at that:

1. Causes and effects form an indefinitely long sequence of events, so in this chain of events start and end of a meaningful correlation (say between a sign and its referent) are identifiable only by presupposing the constitutive correlates of intentional states: namely subject (who would produce linguistic signs ) and object (which would be the referent of the linguistic sign).

2. “reference” between signs and referents is grounded on rule-based behavior that presupposes intentionality with its direction of fit, while causality has no direction of fit at all.

3. a sign can refer to things that do not exist, and things that do not exist can not cause anything

So beliefs would be an idea that something is true based on one observation, while knowledge would be something is true based on multiple observations that are integrated with logic. — Harry Hindu

Belief can be based on one or multiple observations, agreed. But this seems to contradict instead of supporting the idea that belief can be taken “in the form of their visual experiences”. Perceptual beliefs exceed the related visual experience: they are attitudes, but visual experiences are not attitudes. This should be true for both men and animals, to my understanding. -

Debate Discussion: "The content of belief is propositional".Russell, Gettier, and Moore all took JTB to task. — creativesoul

I don’t see what JTB about knowledge has to do with our understanding of belief ascriptions.

It's just that not all belief are equivalent to propositional attitudes, and thus those exceptions cannot be sensibly rendered in those terms. That's what my broken clock example shows us, and quite clearly it seems to me. — creativesoul

Your understanding of belief ascriptions is biased by your philosophical understanding of propositional attitudes. While de dicto/de re belief ascriptions have an appropriate usage and make sanse to competent speakers independently from your ideas about propositional attitudes.

And there is a strong reason to prefer de dicto belief ascriptions over de re ascriptions b/c the former ones generally explain better believers’ intentional behavior, than the latter (assumed they are both correct).

Jack - mistakenly - believed that a broken clock was dependable; read true; was running; was trustworthy; was where he ought look to find out what time it was; etc. Hid did not know that it was broken, but he most certainly believed it! — creativesoul

Your claim is misleading for 2 reasons: 1. De re belief ascriptions make absolutely sense in some cases (e.g. when we try to solve belief ascriptions ambiguities wrt other subjects’ contextual and shared background understanding of the situation [1]), yet it’s not correctness the ground for de-re belief ascriptions! 2. Your de re belief ascription about Jack is based on a de-contextualised assumption that the description “that brocken clock” is correct by hypothesis (an assumption that nobody would take for granted in controversial real cases b/c even your belief ascriptions are beliefs after all!).

[1]

A toddler runs toward a woman walking with her partner in a park, the toddler’s father runs after him, and, knowing that couple from the neighbourhood, explains to the surprised partner: “my son believes that your wife is his mum”. Of course the toddler knows nothing about the marital relationship between the partner and the woman, he doesn’t even have the concept of “marriage”, nor “motherhood” for that matter, as shared by adults, therefore the father’s belief ascription is not de dicto (what would be a de dicto rendering of that toddler’s belief?), yet this de re belief ascription is epistemologically plausible to the father and the couple based on their background and shared understanding of the situation. -

Debate Discussion: "The content of belief is propositional".When translating languages, that is what is translated - the state-of-affairs the scribbles refer to. — Harry Hindu

Not sure about that. Take a couple of English sentences with their relative translations in French:

A1) Alice loves Jim

A2) Jim is loved by Alice

B1) Alice aime Jim

B2) Jim est aimé par Alice

I would take all 4 statements to be about the same state-of-affairs (and you?). Yet B1 is a correct translation of A1 only, and B2 of A2 only. If it was true that the translation is based on reference to the same state-of-affairs then both B1 and B2 would be equally good translations of A1 or A2 indifferently.

Meaning, however, is not arbitrary. It is the relationship between cause and effect. What some scribble means is what caused it to exist on the paper or on the screen. It is caused by a mind — Harry Hindu

The idea that “a mind” is causing “scribble means” doesn’t sound right to me.

“Scribbles” may be the kind of entities that can be caused, but “means” are not caused, nor can be rendered in causal terms.

So non-language creatures have beliefs in that they learn by making observations and what they learn is what they believe to be the case in other similar states-of-affairs. Their beliefs are not in the form of propositions, but the visual experiences they had. The same goes for scribble-using humans, and is how they learned a language in the first place by believing that scribbles can be used to refer to what is the case or not. You have to believe that before you can begin using scribbles. — Harry Hindu

I’m inclined to agree with you in general, but the devil is in the details. So, I agree that animal cognitive skills and consequent behavior are much more constrained by their experience than human cognitive skills are. Yet it doesn’t sound right to me to claim that animals’ beliefs are “in the form of their visual experiences”. The problem is that experience (visual or other) doesn’t seem to be enough to grant belief (see the case of optical illusions like the Müller-Lyer illusion [1]: the 2 arrows keep looking different in length even if one correctly believes that they have the same size), therefore animals’ beliefs too are not necessarily nor tightly coupled with their experiences.

Besides the claim that human’s beliefs are “in the form of propositions” does sound right, at least in part. However I would complement it by saying that a belief in propositional form is just a belief that is expressed through a declarative sentence, i.e. through a specific linguistic behavior, that doesn’t imply that humans are equipped only of propositional beliefs.

[1]

-

Debate Discussion: "The content of belief is propositional".1. Are pictures/images propositions? — Agent Smith

Good question. Here is another one: if all propositions can be rendered in linguistic form, then what proposition would correspond to the following image?

-

Debate Discussion: "The content of belief is propositional".Mind independent abstract entities seems to be a contradiction. Abstractions are defined as existing as an idea and not as physical or concrete. So how can something that is abstract be mind independent? — Harry Hindu

Many philosophers take the technical notion “abstract entity” to mean something that is not the result of some mental operation (“abstraction”). According to them “abstract entities” are to be contrasted to “concrete entities”: indeed both of them are real (i.e. mind-independent) entities , the difference (at least according to many) is that abstract entities are not located in space and time, and they are causally inert, while concrete entities are located in space and time (or at least, in time) and are not causally inert. Propositions, numbers, sets are often taken to be some common cases of abstract entities by those who believe in their existence. So for example, while a sentence is a concrete entity, the proposition that the sentence is meant to represent would be an abstract entity of the sort I’ve just described. Frege seems to have proposed this view.

This sounds like what I was hinting at here:

What form does a language you don't know take? How does that change when you learn the language? Do the scribbles and sounds cease to be scribbles and sounds, or is it that you now know the rules to use those scribbles and sounds? — Harry Hindu — Harry Hindu

Yes it does. -

Debate Discussion: "The content of belief is propositional".creativesoul's reminder of "rigid designators" is misleading. Kripke's theory of rigid designators was supposed to address the logic distinction between proper names and decriptions, and to argue against the Russellian's analysis of proper names in terms of descriptions: now, "broken clock" is a description not a proper name.

Besides we shouldn't take Kripke's theory for granted. And indeed I don't. -

Debate Discussion: "The content of belief is propositional".de re belief ascriptions can be less ambiguously rendered in the following form:

S believes of X that p

E.g. Jack believes of that broken clock that is working

The reason being that in this form, the reference to X is put within the semantic scope of the one who is making the belief ascription instead of the scope of Jack's beliefs themselves.

Other examples to consider:

a1) Jack believes that Alice loves Jim

a2) Jack believes that Jim is loved by Alice

b1) Jack believes that Alice is the sister of Jim

b2) Jack believes that Jim is the brother of Alice

Do a1 and a2 express the same belief?

Do b1 and b2 express the same belief? -

Debate Discussion: "The content of belief is propositional".That gives me a nice place to start. I'll have a look at Sense and Reference. — ZzzoneiroCosm

creativesoul's ideas about belief ascriptions sound not only preposterous (and justifiably so for me), but also very dangerous: e.g. imagine some christian reported the belief of a high muslim mufti as “he believes that Allah is Jesus” because christians take Jesus to truly co-refere to god. And it doesn't matter if christians' religious beliefs are truly true, because as long they believe they are, they are allowed to make belief ascriptions the way creativesoul is suggesting. Indeed belief ascriptions are second order beliefs, and also description/name coreference is matter of belief, that is why we can't simply overlook de dicto belief ascriptions. De re belief ascriptions, are only apparently so, and when we use them appropriately this becomes more evident. -

Debate Discussion: "The content of belief is propositional".I'm spending some time trying to understand what a proposition — ZzzoneiroCosm

The philosophical debate about propositions starts (or should start) from some strong intuitions that should be readily acknowledged by all competent speakers. That doesn’t mean that they are rationally justified, it simply means that philosophical accounts are supposed to neither deny nor underestimate the strength of these intuitions, but to take them as a starting point for their analysis and explanations. Here are at least some strong intuitions:

1. All the following statements say “the same” in different languages:

That apple is on the table (in English)

La pomme est sur la table (in French)

Der Apfel ist auf dem Tisch (in German)

2. All the following statements are about “the same” based on name/description coreference (I.e. “that red apple” and “that Fuji apple” co-refere to the same apple):

That red apple is on the table

That Fuji apple is on the table

3. All the following statements report different types of attitude from different subjects toward “the same”:

Jim sees that apple is on the table

Sally states that apple is on the table

Jack believes that apple is on the table

Cindy does not believe that apple is on the table

Billy hopes that apple is on the table

Alice orders that apple should be on the table

4. In any belief ascription (e.g. “Jack believes that apple is on the table”), what the belief is about is “the same” as what the statement (related to the belief ascription’s subordinate clause) is about (e.g. “that apple is on the table”)

What is “the same” in all 4 strong intuitions? “Propositions” some/many/most philosophers say, but this is a theory-laden notion and it depends on the theory of proposition one supports (I would suggest you to read Frege’s “Sense and reference” to have a better grasp on the issue).

Well, I’m not very familiar with his views (which he also revised over time) so I’m not sure how to answer. As far as I’ve understood, Moore initially takes propositions to be mind-independent abstract entities (a view that was probably inspired by Frege’s views) that constitute the objects of our thoughts and the meanings of our statements. My understanding of meaning (in semantics) is highly influenced by Wittgenstein’s views (as reported in his “Philosophical Investigations”), so for me meanings are not mind-independent abstract entities, but rules that present themselves in the course of actual and contextual linguistic practices: this implies that meanings are neither mind-independent, nor practice independent, besides they are not “objects” of thought since they regulate how we think about “objects”, they kind of operate in our thinking when we think more than being things that we consult in order to think.I'm spending some time trying to understand what a proposition — ZzzoneiroCosm

So “proposition” for me is just a notion that we use for an a-posteriori semantic/logic formalisation of our language, in the same way we use the notion of “name” and “verb” for an a-posteriori grammar formalisation of our language. -

Debate Discussion: "The content of belief is propositional".Jack believed that the clock was working and believed that "the clock is working" is true. Your insertion of the adjective 'stopped' muddies the waters: it adds a perspective: it adds the perspective of some X that knows the clock is stopped.

(Again, I won't be hurt if you don't want to engage. If I can't play with others I'm content to play with myself :sweat: ) — ZzzoneiroCosm

↪ZzzoneiroCosm

You beat me to it! Of course Jack didn't know the clock was stopped. So he didn't believe a stopped clock was working, he believed a clock was workin — Janus

I made the same observation a while ago. -

Debate Discussion: "The content of belief is propositional".Be well. — creativesoul

You too along with your mentor

neomac

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum