Comments

-

The Dan Barker ParadoxTrying to eff the effable? – yeah, that's poetry. Multiple "authors" for each of the 66-70+ books, countless mis/translators & redactors. Nothing credible, some nuggests of memorable 'cautionary tales' gleaming in the fossilized, ignorant dung of Ages. So what's your point, Fool? — 180 Proof

The point, if there's one, is this: people were grappling with two issues viz. ethics and, how can I put it, that which has no name, the so-called Hashem which, if memory serves, simply means name. I don't know how the two ended up under the same roof so to speak but the truth is they did and the problem then becomes to, in a way, weave a coherent story around and about them but, as you can see, this is nigh impossible for one party is, well, outside the domain of everyday experience while the other is, if one really looks at it carefully, just a matter of ouch! and hahaha! -

The Dan Barker Paradox

Religion, whatever said and done, seems to have, on the whole, two sides to it. One is the quite obvious moral dimension we have a love-hate relationship with and the other is the rather obscure aspect to religion which has been approached circumlocutously for the simple reason that it's ineffable, indescribable, inexpressible, and the like.

Could it be that the ancient authors of the holy books were trying very hard to find the foundations of the good in the ineffable and in doing so wrote books whose contents seem to be, well, all over the place, touching upon as many topics as were known back then, all in an effort to ground the good in that which they knew so little about that they didn't even have a consensus on what to call it?

Surely such a state of affairs is a recipe for utter confusion and if Dan Barker is right, that's exactly what is apparent in scriptures. -

The Problem Of The CriterionDid you read my last post. I'll provide a synopsis:

The Problem Of The Criterion has, at its core, the belief that,

1. To define we must have particular instances (to abstract the essence of that which is being defined)

2. To identify particular instances we must have a definition

The Problem Of The Criterion assumes that definitions and particular instances are caught in a vicious circle of the kind we've all encountered - the experience paradox - in which to get a job, we first need experience but to get experience, we first need a job. Since neither can be acquired before the other, it's impossible to get both.

For The Problem Of The Criterion to mean anything, it must be the relationship between definitions and particular instances be such that in each case the other is precondtion thus closing the circle and trapping us in it.

However, upon analysis, this needn't be the case. We can define arbitrarily (methodism) as much as non-arbitrarily (particularism) - there's no hard and fast rule that these two make sense only in relation to each other ss The Problem Of The Criterion assumes. I can be a methodist in certain situations or a particularist in others; there's absolutely nothing wrong in either case. -

The Problem Of The CriterionTo All Concerned

It appears, on closer examination, that The Problem Of The Criterion is a pseudo-dilemma insofar as definitions are concerned because it makes a critical assumption that's unfounded. Let's go through The Problem Of The Criterion again at the risk of boring everyone.

1. We need a definition to identify particular instances

2. We need particular instances to construct a definition.

The Problem Of The Criterion occurs when we realize that to construct a definition we need particular instances but to get particular instances we first need a definition, the circle is constructed and we're inside it, hapless victims of an ingeniously constructed trap.

However...

A way out, if it is one, is to, specific to the problem itself, think of definitions as being of two kinds:

1. Arbitrary definitions. Such definitions are, in a sense, pulled out of the ether very much like a magician produces a rabbit out of his hat. Such definitions don't require particular instances from which some kind of an essence is extracted/abstracted; au contraire such definitions can be viewed of as hypothetical to begin with and if what they define are instantiated then that would make them real. An example of such a definition would be say the word "pigfly" whose definition is "a pig that can fly". As you can see that I'm able to do this indicates, in no uncertain terms, that arbitrary definitions are possible and even real if you consider the word "unicorn"

2. Non-arbitrary definitions. These definitions are derived from particular instances but it's not true that the particular instances were first identified using a definition. What actually happens is a group of objects is studies, a detailed list of their properties are made, and objects in the group are sorted according to different combinations of properties. So, take the group of objects in the set {c, 1, 9, 4, u}. If I sort the elements of this set in the categories letters or numbers I get {c, u} and {1, 4, 9} but if I sort them according to whether they're curvaceous or angular I get {c, 9, u} and {1. 4}. To construct these categories I didn't rely on a preexisting definition; all I did was sort them based on certain properties which were chosen from the list of properties drawn up from the elements themselves.

Since there are two ways of defining i.e. there are two methods of constructing definitions and these two are independent of each other, The Problem Of The Criterion is, at some level, solved because the problem is predicated on the dependence between these two ways of defining. -

Free speech plan to tackle 'silencing' views on university campusThe free speech dilemma is like the gun dilemma. The good guys know that they need guns (free speech) to defend themselves but to do that they have to risk guns (free speech) getting into the wrong hands. To ensure that the good guys are well-protected guns (free speech) are essential but for that the good guys must risk harm from bad guys with guns.

-

The Problem Of The CriterionSo I’m going to throw this back to you: can you define ‘dog’ without a qualitative pattern of non-essential features? — Possibility

No, and isn't that the point?

Sorry but I seem to have lost my train of thought but what I'm getting at is very simple and perhaps that simplicity is misplaced in an issue that is, could be, complex. Let's discuss definitions as it seems to be relevant.

A good definition must:

1. be based on essential features

2. not be too broad or too narrow

3. be clear (no figurative languages, avoid vagueness and ambiguity)

4. be positive whenever possible

5. not be circular

The point of contention between the two of us is 1 - we're debating whether essentialism in definitions is a reasonable condition to ask for. As far as I'm concerned a definition must focus on the essentials, otherwise how would we identify that which is being defined? If that which is being defined can't be identified from a "...line-up..." then the discussion ends there. Nothing more can be said. -

The Dan Barker Paradox:up: :clap: regarding the following:

"That which is despicable to you, do not do to your fellow, this is the whole Torah, and the rest is commentary, go and learn it." — Babylonian Talmud, Shabbat 31a

The way Hillel puts it, it gives us the impression that religion is rather simple at heart and every holy book written or conceived of is just a long-winded discourse - sometimes to the point and other times beating around the bush - on a single a rule predating many of the world's current great religions, that rule being the golden rule viz. do unto others as you would like others to do unto you. I daresay that all religious texts can be made sense of in this way; if your view on the matter are true, assuming my reading is correct, we maybe able to slowly chip away all that's superfluous and incidental from scriptures and what we're left with, at the end of that process, could be the golden rule. So far so good.

I wonder how Dan Barker would respond to your comment and Hillel's insight? Barker seems to be much concerned with the many contradictions which he alleges the Bible suffers from. By his reasoning another, more suitable, title for the Bible, the Torah, and the Quran, is "Contradiction" and he wants nothing to do with them.

If Hilel is correct then Barker would be the unfortunate victim of a deceptive misdirection - he's been led astray, led away from the real message of religion and distracted by the superfluous and the incidental at his own peril.

Nevertheless, to be fair to Barker, the holy books seem to have been written by folks who were doing their very best to get a crucial message across to the people but they themselves seem to have lost their way in the maze of past and then extant paradigms and what came out of that falls short of the mark. -

The Dan Barker ParadoxWhat paradox? — 180 Proof

Interesting that you don't see a paradox. That in itself seems worth investigating. -

Do atheists even exist? As in would they exist if God existed?I'm sorry I am not able to make this clear enough. My fault. What I'm trying to say is that God is an occult notion and Socrates (even if he never lived) is merely a dramatized method of philosophy.

There is no preexisting requirement that you believe Socrates existed. All you need to do is read the material and it speaks for itself. You cannot say the same thing about God in the Abrahamic tradition. Belief is the first step towards taking a moral position - without this you won't accept any of the 613 commandments, let alone the famous 10. As the believer will often argue, an atheist can follow the ten commandments but is still a sinner unless he believes in and loves God. — Tom Storm

What's the logic that underpins the position that believing in god is good? I don't see a clear-cut answer to this question. -

To the benefit or detriment of the state.Socrates was never in the business of proving things - he probably considered that quite impossible given how ignorant everyone, including himself, was/is/will be.

-

The economy of thoughtThe reason behind excluding 1 from the set of primes is that we wouldn't/couldn't have a unique prime factorization for a given number:

For example,

9 = 1 × 3 × 3

9 = 1 × 1 × 3 × 3

9 = 1 × 1 ×...× 1 × 3 × 3

and so on... -

"Persons of color."I suppose you're right but such expressions as "people of color" are what I call linguistic relics i.e. they're remnants of past weltanschauungs that are now outdated. Their presence in the modern world is only indicative of a lack of better, less-prejudiced, expressions, phrases, or words or due to linguistic aspects like shelf-lifes of words, expressions, phrases which maybe determined by various factors none of which I can name as of the moment.

If you'll allow me to make a guess, the one factor that would effectively spell the end of a word, expression, or phrase, it would be when that word, expression, or phrase becomes meaningless; this is where people like you come in I suppose. -

Why Be Happy?If you seek contentment, you can be 100% with happiness when it comes and 100% with sadness when it comes. The key is letting each go, otherwise you will fall into the cycle of birth and death of both over and over and over... — synthesis

I see. Are you 100% with happiness or 100% with sadness? -

Why Be Happy?Why be happy?

Happiness seems to be like a place which we like but where we're persona non grata. So, we always look for reasons, even excuses, to go there but our stay there is short, too short to satisfy us, and we're chased off no sooner than we arrive, and we, in response, constantly look for another reason to go there but then, again, we're deported as it were. Lather, rinse, repeat. The question is, when should we give up? -

Do atheists even exist? As in would they exist if God existed?Well, Socrates isn't God, so the analogy is not apropos. We are not talking about a man's ideas. We are talking about the intrinsic moral position inherent in God belief which I have already addressed. Perfectly fine if you disagree, but I see no way out of it. — Tom Storm

Well, as far as I know, what is said must stand on its own, who said it is irrelevant. Ref: Epicurean dilemma. -

Do atheists even exist? As in would they exist if God existed?A Buddhist canonical reference for this, please. — baker

I'm trying to reconstruct the Buddha's logic. Sorry, nothing explicit to go on except his conspicuous coyness on the matter of God and other metaphysical issues. -

Why do people need religious beliefs and ideas?Sure there is science behind technology, but when the science is not known it doesn't matter. It matters a lot when the science is known. That is when we step away from superstition and realize our power to overcome evil. — Athena

I suppose it's about different levels of experimental rigor. The birth of technology was driven by experimentation yes but these experiments were crude and simply consisted of feeling less tired when rolling something (wheel) than when sliding it (more friction), a similar argument can be made for other ancient technologies that existed before science became a formal discipline. On the other hand science, after it took its present form whenever that was, has as an absolute requirement that experiments meet a certain set of criteria that are designed to not only prove a point but also to reveal the principles of the phenomenon being studied. -

The paradox of Gabriel's horn.:lol:

Suppose r=1/n and h=n^2. Then V -> pi. You are not describing Gabriel's Horn. — jgill

We can't suppose anything we want. Gabriel's horn begins with the assumption that r = 1 and h extends from 0 to infinity. -

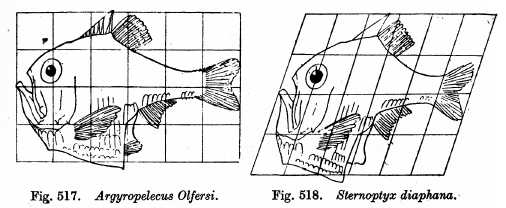

How does evolution work@Wayfarer if interested. Evolution from D'Arcy Wentworth Thompson's (1860 - 1948) point of view isn't anything to be surprised by. The basic body plan is identical in all organisms, at least within a given phylum if I'm correct. The variations in bodies we observe, sometimes so extreme that we completely fail to see the similarity, are simply geometric transformations which may involve some topological elements on the basic baupläne common to a given phylum. The bottom line - some might say - is that we're all just glorified tubes.

See here

That takes care of the physical aspect of evolution. Coming to biochemistry, it's an open secret that all living organisms, even across phyla, have similar, even identical, biochemical pathways.

So, there's not much to evolution - the variety we see in the living world doesn't require too much "work" i.e. random mutations in DNA can easily handle the evolution of species because, at the end of the day, what's happening is existing species are being, how shall I put it, deformed/disfigured i.e. it should be much, much harder to preserve a species' characteristics than to alter it (to form new species).

We're just deformed chimps. :lol: -

The paradox of Gabriel's horn.Surface area of a cylinder A = 2 * pi * r * h where r is the radius and h is the height.

Volume of a cylinder V = pi* r^2 * h where r is the radius and h is height

r approaches zero and h approaches infinity

A = 2 * pi * r * h = 2 * pi * (r approaching zero) * (h approaching infinity)

V = pi * (r approaching zero) * (r approaching zero) * (h approaching infinity)

(r approaching zero) * (h approaching infinity) = 1

So,

A = 2 * pi * 1 = 2 * pi

V = pi * (r approaching zero) * 1 = pi * (r approaching zero) = 0

As you can see, A plateaus to 2 * pi but V becomes 0. -

Free willThe question of free will is an important one. Few can deny that but fewer still have made progress in demonstrating its existence or nonexistence, in fact the problem stands at it did roughly 2000 years ago when Greek/Indian philosophers first put the topic under the philosophical microscope.

Speaking for myself, I must report no progress at all in my investigations into the matter except for one small detail which is best illustrated through scenarios:

Imagine a person, X, who has been offered a choice of fizzy drink between a can of Pepsi and a can of Coke. Consider now that this person is, in scenario 1, simply presented with the two drinks and is asked to choose. However, in scenario 2 a gun is pointed at X's temple and he's asked to pick up the Coke can and not the Pepsi can.

Clearly there's a difference between scenarios 1 and 2 with respect to freedom of choice. In scenario 2, X is under duress to pick up the Coke can but in scenario 1, X is not under any coercion to do so. It's my hunch that such scenarios, which are realistic as in they do occur in real life albeit in different contexts, are the reason why people are under the impression that they have free will.

Note that this, in no way, proves that free will exists because scenario 1 doesn't demonstrate that we weren't compelled by factors other than a gun to the temple - our preference for any particular brand of fizzy drink maybe something we have no control over. Nevertheless...it does provide, in my humble opinion, some kind of an intuition or explanation/reason for why people believe they're free. -

The Problem Of The CriterionIt’s not about essential features, but about recognising patterns in qualitative relational structures. — Possibility

I beg to differ. In the absence of essences to dogs or whatever else is the topic, there can be no further discussion. Can you tell me what "dog" means? I'm supremely confident, as out of character as that is, that you'll be listing a set of essential features.

fuzziness — Possibility

Why are we discussing predictions? -

Is this quote true ?Well, a couple of things:

1. There seems to be a huge body of work on the limitations of logic, math, science, almost every subject we can conceive of. Most of them are obscured by garden variety theses, articles, essays, and so on and their importance is equalled only by their abstruseness insofar as I'm concerned.

2.These limitations should, if anything productive is to follow from them, give us new insights into the nature of logic, math, science and, if all goes well, provide us with clues to how we may improve/replace these "tools".

I'm out. -

Do atheists even exist? As in would they exist if God existed?Don't see how they are not the same. Remember moral behaviour for God is simply that which pleases him. The fist step is belief. Tick. Not believing has been traditionally seen as an immoral position by many believers. Hence, believing is a moral position. — Tom Storm

Well, I'm approaching the issue from a Doestoevskyian point of view, the view that "if god didn't exist, anything would be permissible" which, in essence, means that god's primary role seems to be as the wellspring of morality i.e. god's existence means nothing if morality weren't part of god's being. If so, doesn't that imply we can, like we've all done in our lives, learn the lesson and forget the teacher? I don't see how believing in the existence of Socrates has anything to do with the merits/demerits of his philosophy? -

Why do people need religious beliefs and ideas?I think we assume science and technology are the same thing. They are not. Human beings have always had technology but we did not always have science. Learning a technology does not improve our understanding of life and does not lead to wisdom as science greatly improves our understanding of life, moral judgment, and makes democracy as rule by reason possible. Technology does not lead to wisdom as science does. Education for technology has always been the education of slaves. It is not the education of men. — Athena

You maybe right but I doubt whether there is a well-defined line of demarcation between the two. To my reckoning, the fact of the two being, in a sense, out of phase - technology preceding science - has no bearing on what many have acknowledged viz. that at the heart of every piece of tech we've invented lies a scientific principle. Take for example the wheel - it's a good way to get around the problem of friction. -

What is AncientThe word "ancient" has two meanings that are, in my humble opinion, absolute and relative. I concede that the word itself has no precise definition and is loosely applied to time periods that extend, at a minimum, to thousands of years but, for some reason, it seems to be restricted to human history and that too to the transitional phase between hunter-gatherer societies and the birth of civilizations. That's the absolute meaning of "ancient".

Coming to the relative definition of "ancient", the word is used to describe time-gaps between two objects, one being recent and the other relatively older. I see young people often use the word "ancient" when they talk about adults and elderly people.

:joke: -

Is this quote true ?Isn't the problem of induction something in philosophy as well ? — Swimmingwithfishes

Well, it's a philosophical take on empiricism which itself, as far as I know, is the foundation of the sciences. -

Do atheists even exist? As in would they exist if God existed?Not many believers have read much scripture and often traditions don't come form this source. Actually it is pretty common for a Christian, Jew or Muslim (especially the latter) to see the atheist as making an immoral choice right out of the gate. In fact in Islam (in 13 countries), atheism is punishable by death. — Tom Storm

Well, this in no way proves that believing in God is, in and of itself, a moral act in the same category as saving someone's life or helping the poor, right? The matter of apostasy and heresy, to me, seems to be an entirely different issue with a different explanation altogether e.g. they may be part of the psychological response elicited by a subconscious fear of, for want of a better word, evil as assumed to follow from rejecting God. This makes some kind of sense if it's God, the belief in God, that maintains societal integrity. Is it God, the belief in God, that's the bond between people, keeping them peaceful, and good? -

Is this quote true ?Doesn't physical possibility depend on weather or not physics governs everything ? And can fields like biology and chemistry have their own immutable laws i.e survival of the fittest ? — Swimmingwithfishes

I don't know if this amounts to anything but science seems to be a poor yardstick to study the topic of possibility/impossibility because of the problem of induction. It's true that empirical evidence leads to the discovery of patterns in nature but induction, the strain of logic at work in science, goes out of its way to stress on the contingent nature of empirical knowledge, science inclusive. The same may not apply to logical impossibility - contradictions - because that would mean we're living in a world that doesn't make sense, make sense in the sense that the world is coherent/consistent. To make the long story short, I would be dumbfounded if the law of noncontradiction were violated but mildly amused if a law of nature were violated.

More can be said. -

Do atheists even exist? As in would they exist if God existed?Untrue - Islamic State, just one example, demonstrate that religions - which all have their fundamentalist expressions - cab be ethically repulsive. And there are any number of vile acts committed by religions of all sorts from sexual abuse to bigotry. — Tom Storm

The situation maybe slightly more complex than either of us assume. I was simply pointing out the absence of any clear-cut statement in scripture that claims that one is at an advantage, morally speaking, by believing that god exists. I haven't ever encountered a man of the cloth taking the position that mere belief amounts to a moral act, an act of goodness, an act that would be equivalent to established good actions such as charity or saving someone for example. -

Do atheists even exist? As in would they exist if God existed?I'm second-guessing the Buddha's rationale behind his "no comment" attitude towards God here but take a close look at the situation atheists and theists are in in re God.

There are no moral differences between atheists and theists - both camps seem to be doing fine in the ethics department as far as I can tell.

Ergo, the relevant dissimilarity seems to be only one viz. the belief in the existence of a god. I'm not completely sure about this but I haven't come across a religious doctrine that states that the belief that god exists matters in any way to religion; after all, the bottom line, the key message of theistic religions, is that we'll be judged, and that's what matters, on the basis of the moral nature of our thoughts and actions, and not by whether we believed that a god exists or not.

Do we get bonus points for believing in god? Is there a difference between X who believes in god and is good and Y who is equally good but doesn't believe in god? Perhaps, if you'll allow me to say so, there's a correlation between a tendency toward theism and good moral character but that's psychology and has little or nothing to do with the the ontological aspects of god. -

Complexity in MathematicsSorry to have wasted your time then. I've bitten off more than I can chew. G'day.

-

Is this quote true ?I don't know how meaningful what I'm going to say will be in re your question's import but my approach will be from the other side of the coin of possibility viz. impossibility, although I suspect it might amount to the same thing.

1. Logical impossibility [contradiction]. A square circle is impossible. This variety of impossibility is what the entire edifice of philosophy is based on. Take note, however, that there are logics that make room for true contradictions e.g. paraconsistent logic and dialetheism.

2. Physical impossibility, an example of which is the now-famous speed limit on all physical motion, kind courtesy of the great Albert Einstein.

3. Technological impossibility, an example of which is teleportation, a trope in the Star Trek franchise

And, just for fun and because I've run out meaningful things to say, the impossibility implied in:

4. "You're impossible!" screamed Greta as she stormed out of the room.

It's only a hunch of mine but philosophy, at least its logic department, seems to be well on its way exploring the subject of possibility/impossibility as it applies to itself and other disciplines as well - sometimes it gives philosophy a game-like quality and we're left with the impression that we're all children at heart though we now have crow's feet around our eyes, knee problems, and backaches.

Science, on the other hand, seems to be focused on physical and technological possibilities.

Will the two, philosophical and scientific, trajectories intersect at some point or is one a subset of the other? Your guess is as good as mine. -

Why do people need religious beliefs and ideas?Splendid, sir. Exactly what it would mean. — Wayfarer

I'm in your debt. G'day -

Why do people need religious beliefs and ideas?The origin of modern science was to concentrate on a particular type of causal explanation - what Aristotle would call material and efficient causation. What cause gives rise to what effect? But the two other kinds of causes were left out. — Wayfarer

:up: :clap: It's true that science, in its present form, seems to be only half the story if we look at it from an Aristotelian perspective on causality.

As I remember, Aristotle on causes and how science has dealt with them:

1. Material cause. Check

2. Efficient cause: Check

3. Formal cause: Check but only descriptively

4. Final cause: Ignored

It must be then that were Aristotle alive, science would be exactly half the picture in his eyes. The way I see it, Aristotle's take on causality seems to provide, intended or not, a good place to start the reunification process of science and religion given, as it appears to me, the first two causes as listed above is what current science is about and the last two causes seem to have a religious dimension. -

Complexity in Mathematicsnumber of alphabets, but rather with the cardinality of the set of symbols — GrandMinnow

Explain this difference. My high school math knowledge informs me that these are the same thing.

it appears, as in other threads, that this poster is not familiar with the actual subject matter of the discussion. — GrandMinnow

A thousand apologies. :smile:

As far as I know, Godel's theorems aren't a function of, ergo not liable to be disproved, assuming that is your objective, by any consideration of the cardinality of the symbol set employed in proving them.

To be fair though, if I'm not mistaken about the general idea behind your, what shall I call it, hypothesis, I'm very eager to see what it leads to.

As for my personal views on the matter, you might want to consider the matter of polysemy, something I'm sure you're familiar with. Given that one symbol maybe given two or more semantic identities, your investigation, if I may call it that, fails right from the start for the simple reason that the cardinality of the set of symbols is completely arbitrary and that implies you would draw the wrong conclusions, see patterns that may not really exist.

Of course, what I know about logic and computer languages if that's relevant at all indicates that they're constructed in ways that make it a point to avoid polysemous words. It's only after taking this into account that we can hope to find some kind of correlation between Godel's theorems and alphabets.

I hope I didn't bore you. -

Why do people need religious beliefs and ideas?Try googling ‘dark matter occult’. — Wayfarer

Yeah, science and even math, in certain respects, seems to have come full circle. Both had origins in occult practices (grain of salt recommended), along the way, they discarded this filial association, and now, they're back into doing business in the gray zone between science as we know it and, for lack of a better word, religion. The child has returned home.

TheMadFool

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum