Comments

-

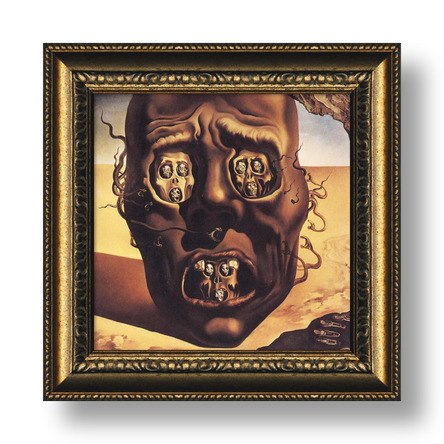

The Mind-Created World

As long as you include Kant in your criticism, I hear you. I do appreciate the relative clarity of English philosophers like J. S. Mill and Hume and so on. Descartes is excellent on this point too. But that's a bit of a secondary issue. I agree with ol' Popper that the source of an idea don't matter. It stands or falls on its own. One of Heidegger's problems was his reluctance to embrace this idea of the independence of the fruit from the soil. And how can we drag in Buddhism (and so on) without the assumption that such a transplant is meaningful ? So, respectfully, I'm not tempted to reject ideas on the basis of their circumstantial embedding context. Though obviously, like anyone, I'm less likely to bother figuring out what someone is saying if the package isn't promising.

More generally on the issue of charisma, authority, and other related source issues, I invoke a mathematical metaphor. I care more about the 'theorems' than the 'mathematicians,' but as a 'mathematician' I have a secondary interest in other players of the game. Indeed, a big part of reality is this cooperative adversarial structure of the [self-positing] Conversation that comes to understand itself. Theology constructs the God it seeks in that very seeking. (?) -

The Mind-Created WorldThen Ven. Maha Kotthita went to Ven. Sariputta and, on arrival, exchanged courteous greetings with him. After an exchange of friendly greetings & courtesies, he sat to one side. As he was sitting there, he said to Ven. Sariputta, "With the remainderless stopping & fading of the six contact-media [vision, hearing, smell, taste, touch, & intellection] is it the case that there is anything else?" — Kotthita Sutta, AN 4.174

Personally, I think those six elements are a plausible decomposition of all possible experience/reality in the abstract. So I'd answer no. Intellection includes the structure of the rest (and its own self-referential, arbitrarily complex internal structure.) -

The Mind-Created World

I'd say our skill with the word 'I' is part of that thrown falling immersion or they-self that we only can even begin to investigate after the fact of our enculturation. I'm a master of use before I even begin really to theorize about that use. -

The Mind-Created World

:up:As Thanissaro Bikkhu (translator) notes in his commentary, ‘the root of the classifications and perceptions of objectification is the thought, "I am the thinker." This thought forms the motivation for the questions that Ven. Maha Kotthita is presenting here.’ The very action of thinking ‘creates the thinker’, rather than vice versa. — Wayfarer

In other words ( ? ) , language speaks the subject. A convention of selfhood emerges, a very early piece of intellectual technology. This conceptual-cultural self is real enough, just not (in my view) absolute.

https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/johann-fichte/#Foun“the I posits itself”; more specifically, “the I posits itself as an I.” Since this activity of “self-positing” is taken to be the fundamental feature of I-hood in general, the first principle asserts that “the I posits itself as self-positing.”

The principle in question simply states that the essence of I-hood lies in the assertion of ones own self-identity, i.e., that consciousness presupposes self-consciousness (the Kantian “I think,” which must, at least in principle, be able to accompany all our representations). Such immediate self-identify, however, cannot be understood as a psychological “fact,” no matter how privileged, nor as an “action” or “accident” of some previously existing substance or being. To be sure, it is an “action” of the I, but one that is identical with the very existence of the same. In Fichte’s technical terminology, the original unity of self-consciousness is to be understood as both an action and as the product of the same: as a Tathandlung or “fact/act,” a unity that is presupposed by and contained within every fact and every act of empirical consciousness, though it never appears as such therein.

...

A fundamental corollary of Fichte’s understanding of I-hood (Ichheit) as a kind of fact/act is his denial that the I is originally any sort of “thing” or “substance.” Instead, the I is simply what it posits itself to be, and thus its “being” is, so to speak, a consequence of its self-positing, or rather, is co-terminus with the same. -

Pacifism and the future of humanity

I agree with your values, but I don't think it's a problem, mostly anyway, of us not individually wanting the good. I'm reluctant to even share my thinking here, because it's [ what many would call ] dreary and fatalistic. But what I have in mind is stuff like incentive structures and game theory (for instance, lately I'm reading Games of Life by Karl Sigmund.)

But before that I was reading an evolution textbook (Freeman/Herron). It opens with a study of the AIDS virus and analyzes how such a thing could evolve to counterintuitively kill its own host and therefore itself. It was too easy to see the analogy to humans. We are the AIDS virus killing our host, because in the short term it's advantageous for us to do so. And our reality just seems to be structured this way, as if it's a brute fact. I think our one-time visitor David Pearce nailed it with his focus on Darwinian evolution. The rest seems relatively shallow to me at the moment. If we follow the clues, they seem to lead back to the way we were made. And there's no one to blame. Trivially (obviously) that doesn't save us from having to navigate our little lives down here or justify our bad behavior. But it helps me anyway to understand the world. It's almost tautological, given fairly simple assumptions. But why the brute fact of this kind of world in the first place ? I don't know. -

Neutral Monism / Perspectivism / PhenomenalismA man from the country seeks "the law"[1] and wishes to gain entry to it through an open doorway, but the doorkeeper tells the man that he cannot go through at the present time. The man asks if he can ever go through, and the doorkeeper says it is possible "but not now (jetzt aber nicht)". The man waits by the door for years, bribing the doorkeeper with everything he has. The doorkeeper accepts the bribes, but tells the man he only accepts them "so that you do not think you have left anything undone". The man does not attempt to gain entry by force, but waits at the doorway until he is about to die. Right before his death, he asks the doorkeeper why, even though everyone seeks the law, no one else has come in all the years he has been there. The doorkeeper answers, "No one else could ever be admitted here, since this gate was made only for you. I am now going to shut it."

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Before_the_Law -

The Mind-Created World

One of my concerns about hidden-in-principle stuff in the self is that it leads us back into dualism. If to be is to be [potentially ] perceived or experienced, then nothing is [ absolutely ] hidden. If the world exists perspectively for 'transcendental' subjects which are ultimately nondual, then the deep structure of the subject must exists as manifest, both in the structure of the worldstreaming and then in the conceptual layer of this streaming as part of an intellectual culture that unveils it. The 'self in itself' which is 'infinitely' hidden ruins the whole nondual project, it seems to me.

I do acknowledge the obvious reality and intensity of memory and fantasy. And obviously we have the concept of both faculties, but I'd say the meaning of such faculties is ultimately in actual memories and fantasies that we've learned to classify. The lifeworld is always already culturally structured, and that includes interpretations of 'inner' states (and our sense of them as inner as opposed to outer, mine and not ours.) -

The Mind-Created WorldWell, Heidegger was according to some readings still pre-occupied with the fallen state of humanity. — Wayfarer

I agree that Heidegger was influenced, etc., though I personally have no trouble yanking 'falling immersion' and many other concepts into a secular/'universal' context. I can't speak for others, but I'm interested in the work as a body of potential insight which can be personally sifted and tested. Part of the attraction of phenomenology is its deeply anti-authority check-for-yourself spirit. It's also largely descriptive, simply pointing out what's typically overlooked, eschewing fancy uncertain constructions. -

The Mind-Created Worldexcept for when we don't, which seems to happen an awful lot. — Wayfarer

Sure, we are a wicked bunch, and there's an entire tradition with a right way for talking about that.

I've been reading some mathematical biology stuff, and it all makes a sick kind of sense. It's almost tautological that the world is snafu, given certain plausible assumptions and mathematical theorems. Life 'is' exploitation in a certain sense, with altruism 'forming' the inside of a larger organism (my group against yours.) I'm following the mess in Israel, and it's the same old history is a nightmare from which I'm trying to awake. -

The Mind-Created WorldRight. Dasein as being 'thrown into' existence. (Anamnesis, remembering how it happened, although I don't think that's in Heidegger.) — Wayfarer

Indeed, and it's like being thrown into a kind of driving or sleepwalking. We are thrown into doing things the Right way. One eats with a fork, says please and thank you, doesn't walk outside without pants on. One circumspectively takes a couch as something for sitting on. And, as we've discussed, one looks right through the way that objects are given to their practical relevance. In our culture, one learns that the human is a rational animal in the system of nature, and not of course (how silly ! ) the very site of being. Also religion is a Private Matter. I don't object to this last one, but I notice it. I'm aware that it emerged after centuries of something else.

I like Heidegger's phrase which is translated as 'falling immersion.' Our tendency is to fall back into the cultural default, which is not all bad, because plenty of conventions are justified. -

The Mind-Created WorldAs I understand it, Husserl grounds arithmetic in the act of counting. (I have the idea that this actually dovetails with Aquinas' idea of 'being as a verb'. So arithmetic, even though it comprises 'unchanging truths' on the one hand, is also inherently dynamic, in that grasping it is an activity of the intellect.) — Wayfarer

:up:

Have you ever seen rectangles of dots used to prove the commutative law ? Very persuasive. For me math is more visual than temporal, though it's grasped in time. Peirce thought of it in terms of diagrams. I think he was right, but that might be my visual bias talking. Others might 'see' the same mathematical objects differently. As long as people agree on their nature, it'd be hard to know. Sort of like the red-green reversal issue. -

The Mind-Created WorldReason is the relation of ideas. And the reason why it seems 'metaphysical' is because, as we already established, you look with it, not at it. We can't know it, because it is what is knowing. — Wayfarer

I'll agree with you partially here, on Heideggarian terms. Our fundamental form of being is a kind of 'subrational' understanding or knowhow or skill. And we live in language like a water lives in fish (I'm keeping this accidental reversal in, because it's fun.) We rely upon this blind skill in order to even begin to articulate our own ability to articulate. Our minds are an especially 'transcendent' object in the Husserlian sense ---the most complicated, manifold, and 'horizonal' of familiar entities. -

The Mind-Created WorldFor most mathematicians the empiricist principle that 'all knowledge comes from the senses' contradicts a more basic principle: that mathematical propositions are true independent of the physical world. Everything about a mathematical proposition is independent of what appears to be the physical world. — Scrapbook Entry, from an archived version of the Wikipedia entry on Philosophy of Mathematics

I loved Pinter's book on abstract algebra, and such algebra is a great example of abstraction. Group theory ignores absolutely everything about a system except its satisfaction of a few simple axioms. This allows for a rich theory that applies to all possible groups at once, even those not yet invented or discovered. But this theory still exists in the world as an intellectual tradition. It uses symbols to support a thinking which is basically immaterial. (I'm not a formalist. Math gives insight.) The theory is also temporal-historical. No mathematician can hold it all in their intuition at once. He or she can review the forgotten proof/justification of a theorem. Can reason (and often does) in terms of Assuming P, then ...

I don't know how seriously we should take 'physical world' if we've already granted that the being of the world is essentially perspectival --that physicality is derivative and conventional --- understood in terms of possible and actual experience. -

The Mind-Created WorldThey do indeed 'structure' experience, but they're not derived from experience. That's what makes them 'transcendental'. — Wayfarer

But all apriori knowledge is fished out of experience in the first place. Patterns in experience are noticed, articulated, and then [now consciously] relied upon. Even the early geometers had to 'see' or notice certain patterns in the first place, till they finally organized an axiomatic theory for the efficient communication of this insight to others.

The German phenomenologist Edmund Husserl wrote a famous essay, “The Origin of Geometry” that called for a new kind of “historical” research, to recover the “original” meaning of geometry, to the man, whoever he was, who first invented it.

It seems to me not that hard to imagine the origin of geometry. Once upon a time, even twice or several times, someone first noticed some simple facts. For example, when one stick lies across another stick, there are four spaces that you can see. You can see that they are equal in pairs, opposite to opposite. It happened something like this, perhaps at some campfire, 20 or 30,000 years ago.

https://math.unm.edu/~rhersh/geometry.pdf -

The Mind-Created WorldWhich, now that I reflect further, suggests 'that of which we cannot speak....' — Wayfarer

Ancestral objects are a totally reasonable concern, but I think they've already been covered by Mill's theory of possible experience. The meaning of an ancestral statement ('there used to be these giant lizards') is something like: if we had a time machine, we could go back and see those famous dinosaurs. Now some physical theories (11 dimensional, etc.) are impossible to even imagine, and I'd class them with what Kojeve calls 'the silence of algorithm.' The meaning of those theories only comes into focus with predictions that are finally 'within' the sensibility of the lifeworld. Note that chatbots use a mathematics of millions and even billions of 'dimensions.'

Something like Hegelian semantic holism is central here. No finite or radically disconnect entity has genuine being, because it'd literally be nonsense. Sense is structural-relational. That sort of thing. To explain a cat you need to explain a mouse. Single concepts (a language with only one) don't make sense (Sellars/Brandom). -

The Mind-Created WorldOn the contrary - doesn't C S Peirce say that 'matter is effete mind'? — Wayfarer

I grant that we could also read the thing backwards, with nature as a 'segment' of spirit. We create the scientific image from within an encompassing lifeworld. It depends on whether we are reasoning 'outwards' from where we always already are (the enabling assumptions of ontology) or trying to tell a plausible story of how we ended up here.

To me it's implausible for us to deny that we inherit centuries of development, and our best biological stories extend this to millions of years. -

The Mind-Created WorldAlthough the psychological or epistemological specifics given by Mill through which we build our logical apparatus may not be completely warranted, his explanation still inadevertantly manages to demonstrate that there is no way around Kant’s a priori logic. To restate Mill's original idea: “Indeed, the very principles of logical deduction are true because we observe that using them leads to true conclusions” - which is itself a deductive proposition! — Scrapbook Entry, from an archived version of the Wikipedia entry on Philosophy of Mathematics

I agree that Mill was guilty of psychologism on the issue of logic. But this doesn't establish some kind of metaphysical machinery hidden in the Self. Indeed, I'm more inclined to take a Hegel-Heidegger path here and emphasize that the self (as normative-ethical-linguistic locus of freedom-responsibility ) is largely and even mostly a social entity, a performance of and participation of norms, including logical-semantic norms. We performing such norms right now, as we try to articulate and explain those very norms within a framework of adversarial cooperation.

As far as I can tell, Kantian logical machinery wouldn't work anyway. How can a 'machine' (a mere faculty) give us a normative 'output' ? Unless you are invoking some kind of mystical supernatural 'biology,' it's not clear how this wouldn't be more psychologism. 'We are programmed to be logical.' Normativity seems pretty irreducible. Invoking faculties doesn't seem to help us here, for is that not equivalent to evolutionary biology, except in an opposite 'theological biology' flavor ? -

The Mind-Created WorldBut he moves on to Kant who showed that there must be innate faculties :yikes: which organize and categorise sense-data, otherwise we would not be able to make sense of sense. — Wayfarer

It'd be very un-Kantian to make those faculties more than structures or possibilities of experience. I have not the least objection to psychological entities like memory, but I'd say these faculties are mere postulations for explaining a structure in the experience that is first and foremost just there.

Heidegger does his own Kantian thing in articulating the care-structure of this world-streaming being-there. An evolutionary psychologist might postulate how expectation in the context of memory maximizes the average number of offspring. Which is fine. But the existence of that care structure (existence as that enworlded care structure) is primary. Explanations are secondary and tentative. This to me is part of phenomenological bracketing. Let's articulate what's there first, before we jump into theorizing. -

The Mind-Created WorldThe objects of experience then are not things in themselves, but are given only in experience, and have no existence apart from and independently of experience. — Kant

The OP is pretty well an exercise in understanding how this can be true. — Wayfarer

I really like the bolded part of the Kant quote, but I find it in tension with the first part. The objects are given only in experience and don't exist otherwise. So what in the world (but of course not in the world, which is exactly the problem) is left over ? -

The Mind-Created WorldI quoted from that in my MA thesis in Buddhist Studies. As I've said before, the self is never an object, yet the reality of the subject of experience ('what it is like to be....') is apodictic, cogito ergo sum. Where in the world is the metaphysical subject to be noted? Why, that would be 'nowhere', yet otherwise there is no world. — Wayfarer

'What it is like to be' is an interpretation of something prior to mind or non-mind. That's the way I'd go here. What interprets then ? If mind is not fundamental ? I'd go with some kind of emergent 'panlogical' timebinding. There is a subject, but it's cultural and emergent and self-positing. Spirit is a modification of nature. I don't pretend to explain this emergence. I prioritize [merely] articulating the given ---only a blurry-muddy-tentative foundation for further plausible speculation. -

Neutral Monism / Perspectivism / PhenomenalismThe article on neutral monism is a bit scanty, but something is better than nothing.

**************************************

Mach and James understand neutral monism as an especially radical form of achieving perceptual contact with the world. It might be understood as a limiting case of naïve realism—a case in which the relation between the subject and its perceptual object becomes the identity relation. In perception “subject and object merge” (James 1905: 57). A single reality—a red patch, say, when we see a tomato—is a constituent of two groups of neutral entities: the group that is the perceiver, and the group that is the tomato. The mind and its object become one. In James’s words:

A given undivided portion of experience, taken in one context of associates, plays the part of the knower, or a state of mind, or “consciousness”; while in a different context the same undivided bit of experience plays the part of a thing known, of an objective “content”. In a word, in one group it figures as a thought, in another group as a thing.

....

The most frequent type of objection to the traditional versions of neutral monism is that they are forms of mentalistic monism: Berkleyan idealism, panpsychism, or phenomenalism. The core argument is simple: sensations (Mach), pure experience (James) and sensations/percepts (Russell) are paradigms of non-neutral, mental entities. Hence there is nothing neutral about these neutral monisms. This type of objection—the “mentalism suspicion”—has been articulated by a diverse group of philosophers...

**************************************

https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/neutral-monism/#MindBodyProb

The objection is initially understandable. There's a tendency of neutral monists to cling to a still-subjective terminology. But I hope I've explained this tendency. What is given (just check yourself) is a care-structured 'streaming' of being with a sentient body as its roving center. Small wonder then the tendency to conflate the no-longer-subjective transcendentalegowith the psychological ego. Both are associated with the same body, and we reason about others in terms of their awareness and what they have a right to claim. -

The Mind-Created WorldLast one for now, I promise. Mill dissolves the subject too.

https://oll.libertyfund.org/title/mill-the-collected-works-of-john-stuart-mill-volume-ix-william-hamiltons-philosophyWe have no conception of Mind itself, as distinguished from its conscious manifestations. We neither know nor can imagine it, except as represented by the succession of manifold feelings which metaphysicians call by the name of States or Modifications of Mind. It is nevertheless true that our notion of Mind, as well as of Matter, is the notion of a permanent something, contrasted with the perpetual flux of the sensations and other feelings or mental states which we refer to it; a something which we figure as remaining the same, while the particular feelings through which it reveals its existence, change. This attribute of Permanence, supposing that there were nothing else to be considered, would admit of the same explanation when predicated of Mind, as of Matter. The belief I entertain that my mind exists when it is not feeling, nor thinking, nor conscious of its own existence, resolves itself into the belief of a Permanent Possibility of these states. If I think of myself as in dreamless sleep, or in the sleep of death, and believe that I, or in other words my mind, is or will be existing through these states, though not in conscious feeling, the most scrupulous examination of my belief will not detect in it any fact actually believed, except that my capability of feeling is not, in that interval, permanently destroyed, and is suspended only because it does not meet with the combination of conditions which would call it into action: the moment it did meet with that combination it would revive, and remains, therefore, a Permanent Possibility.

He then tackles the concern that understanding the self as what I'd call a worldstreaming implies solipsism.

He somewhat follows Husserl and suggests that we have good reasons to infer or suppose that others are worldstreams too, though we don't have direct access to this streaming. And in the age of high tech and AI, we may eventually be faced with genuine perplexity. Does this thing feel? Does this thing see ? Note that (for me) we can't 'prove' that other humans are 'really' there, but most of us fortunately don't wrestle with living, genuine doubt.In the first place, as to my fellow-creatures. Reid seems to have imagined that if I myself am only a series of feelings, the proposition that I have any fellow-creatures, or that there are any Selves except mine, is but words without a meaning. But this is a misapprehension. All that I am compelled to admit if I receive this theory, is that other people’s Selves also are but series of feelings, like my own. Though my Mind, as I am capable of conceiving it, be nothing but the succession of my feelings, and though Mind itself may be merely a possibility of feelings, there is nothing in that doctrine to prevent my conceiving, and believing, that there are other successions of feelings besides those of which I am conscious, and that these are as real as my own. -

Neutral Monism / Perspectivism / PhenomenalismMill tries to explain how we could come to believe in paradoxical substance beyond the possibility of experience. It's maybe like Husserl's examination of our growing misunderstanding of Galileo's science in Crisis.

It may perhaps be said, that the preceding theory gives, indeed, some account of the idea of Permanent Existence which forms part of our conception of matter, but gives no explanation of our believing these permanent objects to be external, or out of ourselves. I apprehend, on the contrary, that the very idea of anything out of ourselves is derived solely from the knowledge experience gives us of the Permanent Possibilities. Our sensations we carry with us wherever we go, and they never exist where we are not; but when we change our place we do not carry away with us the Permanent Possibilities of Sensation: they remain until we return, or arise and cease under conditions with which our presence has in general nothing to do. And more than all—they are, and will be after we have ceased to feel, Permanent Possibilities of sensation to other beings than ourselves. Thus our actual sensations and the permanent possibilities of sensation, stand out in obtrusive contrast to one another: and when the idea of Cause has been acquired, and extended by generalization from the parts of our experience to its aggregate whole, nothing can be more natural than that the Permanent Possibilities should be classed by us as existences generically distinct from our sensations, but of which our sensations are the effect.

*

The same theory which accounts for our ascribing to an aggregate of possibilities of sensation, a permanent existence which our sensations themselves do not possess, and consequently a greater reality than belongs to our sensations, also explains our attributing greater objectivity to the Primary Qualities of bodies than to the Secondary. For the sensations which correspond to what are called the Primary Qualities (as soon at least as we come to apprehend them by two senses, the eye as well as the touch) are always present when any part of the group is so. But colours, tastes, smells, and the like, being, in comparison, fugacious, are not, in the same degree, conceived as being always there, even when nobody is present to perceive them. The sensations answering to the Secondary Qualities are only occasional, those to the Primary, constant. The Secondary, moreover, vary with different persons, and with the temporary sensibility of our organs; the Primary, when perceived at all, are, as far as we know, the same to all persons and at all times.

...

We have no conception of Mind itself, as distinguished from its conscious manifestations. We neither know nor can imagine it, except as represented by the succession of manifold feelings which metaphysicians call by the name of States or Modifications of Mind. It is nevertheless true that our notion of Mind, as well as of Matter, is the notion of a permanent something, contrasted with the perpetual flux of the sensations and other feelings or mental states which we refer to it; a something which we figure as remaining the same, while the particular feelings through which it reveals its existence, change. This attribute of Permanence, supposing that there were nothing else to be considered, would admit of the same explanation when predicated of Mind, as of Matter. The belief I entertain that my mind exists when it is not feeling, nor thinking, nor conscious of its own existence, resolves itself into the belief of a Permanent Possibility of these states. If I think of myself as in dreamless sleep, or in the sleep of death, and believe that I, or in other words my mind, is or will be existing through these states, though not in conscious feeling, the most scrupulous examination of my belief will not detect in it any fact actually believed, except that my capability of feeling is not, in that interval, permanently destroyed, and is suspended only because it does not meet with the combination of conditions which would call it into action: the moment it did meet with that combination it would revive, and remains, therefore, a Permanent Possibility.

It's nice that he dissolves the magic subject too. -

The Mind-Created World

https://oll.libertyfund.org/title/mill-the-collected-works-of-john-stuart-mill-volume-ix-william-hamiltons-philosophyMatter, then, may be defined, a Permanent Possibility of Sensation. If I am asked, whether I believe in matter, I ask whether the questioner accepts this definition of it. If he does, I believe in matter: and so do all Berkeleians. In any other sense than this, I do not. But I affirm with confidence, that this conception of Matter includes the whole meaning attached to it by the common world, apart from philosophical, and sometimes from theological, theories. The reliance of mankind on the real existence of visible and tangible objects, means reliance on the reality and permanence of Possibilities of visual and tactual sensations, when no such sensations are actually experienced. We are warranted in believing that this is the meaning of Matter in the minds of many of its most esteemed metaphysical champions, though they themselves would not admit as much: for example, of Reid, Stewart, and Brown. For these three philosophers alleged that all mankind, including Berkeley and Hume, really believed in Matter, inasmuch as unless they did, they would not have turned aside to save themselves from running against a post. Now all which this manœuvre really proved is, that they believed in Permanent Possibilities of Sensation. We have therefore the unintentional sanction of these three eminent defenders of the existence of matter, for affirming, that to believe in Permanent Possibilities of Sensation is believing in Matter. It is hardly necessary, after such authorities, to mention Dr. Johnson,

or any one else who resorts to the argumentum baculinum of knocking a stick against the ground. Sir W. Hamilton, a far subtler thinker than any of these, never reasons in this manner. He never supposes that a disbeliever in what he means by Matter, ought in consistency to act in any different mode from those who believe in it. He knew that the belief on which all the practical consequences depend, is the belief in Permanent Possibilities of Sensation, and that if nobody believed in a material universe in any other sense, life would go on exactly as it now does. He, however, did believe in more than this, but, I think, only because it had never occurred to him that mere Possibilities of Sensation could, to our artificialized consciousness, present the character of objectivity which, as we have now shown, they not only can, but unless the known laws of the human mind were suspended, must necessarily, present.

Perhaps it may be objected, that the very possibility of framing such a notion of Matter as Sir W. Hamilton’s—the capacity in the human mind of imagining an external world which is anything more than what the Psychological Theory makes it—amounts to a disproof of the theory. If (it may be said) we had no revelation in consciousness, of a world which is not in some way or other identified with sensation, we should be unable to have the notion of such a world. If the only ideas we had of external objects were ideas of our sensations, supplemented by an acquired notion of permanent possibilities of sensation, we must (it is thought) be incapable of conceiving, and therefore still more incapable of fancying that we perceive, things which are not sensations at all. It being evident however that some philosophers believe this, and it being maintainable that the mass of mankind do so, the existence of a perdurable basis of sensations, distinct from sensations themselves, is proved, it might be said, by the possibility of believing it.

Let me first restate what I apprehend the belief to be. We believe that we perceive a something closely related to all our sensations, but different from those which we are feeling at any particular minute; and distinguished from sensations altogether, by being permanent and always the same, while these are fugitive, variable, and alternately displace one another. But these attributes of the object of perception are properties belonging to all the possibilities of sensation which experience guarantees. The belief in such permanent possibilities seems to me to include all that is essential or characteristic in the belief in substance. I believe that Calcutta exists, though I do not perceive it, and that it would still exist if every percipient inhabitant were suddenly to leave the place, or be struck dead. But when I analyse the belief, all I find in it is, that were these events to take place, the Permanent Possibility of Sensation which I call Calcutta would still remain; that if I were suddenly transported to the banks of the Hoogly, I should still have the sensations which, if now present, would lead me to affirm that Calcutta exists here and now. We may infer, therefore, that both philosophers and the world at large, when they think of matter, conceive it really as a Permanent Possibility of Sensation. But the majority of philosophers fancy that it is something more; and the world at large, though they have really, as I conceive, nothing in their minds but a Permanent Possibility of Sensation, would, if asked the question, undoubtedly agree with the philosophers: and though this is sufficiently explained by the tendency of the human mind to infer difference of things from difference of names, I acknowledge the obligation of showing how it can be possible to believe in an existence transcending all possibilities of sensation, unless on the hypothesis that such an existence actually is, and that we actually perceive it.

The explanation, however, is not difficult. It is an admitted fact, that we are capable of all conceptions which can be formed by generalizing from the observed laws of our sensations. Whatever relation we find to exist between any one of our sensations and something different from it, that same relation we have no difficulty in conceiving to exist between the sum of all our sensations and something different from them. The differences which our consciousness recognises between one sensation and another, give us the general notion of difference, and inseparably associate with every sensation we have, the feeling of its being different from other things: and when once this association has been formed, we can no longer conceive anything, without being able, and even being compelled, to form also the conception of something different from it. This familiarity with the idea of something different from each thing we know, makes it natural and easy to form the notion of something different from all things that we know, collectively as well as individually. It is true we can form no conception of what such a thing can be; our notion of it is merely negative; but the idea of a substance, apart from its relation to the impressions which we conceive it as making on our senses, is a merely negative one. There is thus no psychological obstacle to our forming the notion of a something which is neither a sensation nor a possibility of sensation, even if our consciousness does not testify to it; and nothing is more likely than that the Permanent Possibilities of sensation, to which our consciousness does testify, should be confounded in our minds with this imaginary conception. All experience attests the strength of the tendency to mistake mental abstractions, even negative ones, for substantive realities; and the Permanent Possibilities of sensation which experience guarantees, are so extremely unlike in many of their properties to actual sensations, that since we are capable of imagining something which transcends sensation, there is a great natural probability that we should suppose these to be it. — Mill

There's so much insight pack in these passages that I'm surprised that Mill is not more talked about. It was Husserl's appreciated of the some of the English philosophers that got me looking into Mill and Berkeley. With Mill, so far, there's no theological baggage to step around.

All experience attests the strength of the tendency to mistake mental abstractions, even negative ones, for substantive realities.

I think Mill hits the nail on the head on this issue of the I-know-not-what that's supposed to be more than possible or actual experience : some kind of [ aperspectival ] Substance that's hidden forever behind or within whatever actually appears. It seems cleaner to understand reality itself as horizonal or transcendent, which is to say never finally given but also not hiding behind itself.

As far as I can tell, this isn't of much practical importance. But for those who find themselves wanting clarity and coherence with respect to fundamental concepts, it might feel like progress. -

The Mind-Created World

https://oll.libertyfund.org/title/mill-the-collected-works-of-john-stuart-mill-volume-ix-william-hamiltons-philosophyThe sensations, though the original foundation of the whole, come to be looked upon as a sort of accident depending on us, and the possibilities as much more real than the actual sensations, nay, as the very realities of which these are only the representations, appearances, or effects. When this state of mind has been arrived at, then, and from that time forward, we are never conscious of a present sensation without instantaneously referring it to some one of the groups of possibilities into which a sensation of that particular description enters; and if we do not yet know to what group to refer it, we at least feel an irresistible conviction that it must belong to some group or other; i.e. that its presence proves the existence, here and now, of a great number and variety of possibilities of sensation, without which it would not have been. The whole set of sensations as possible, form a permanent background to any one or more of them that are, at a given moment, actual; and the possibilities are conceived as standing to the actual sensations in the relation of a cause to its effects, or of canvas to the figures painted on it, or of a root to the trunk, leaves, and flowers, or of a substratum to that which is spread over it, or, in transcendental language, of Matter to Form.

When this point has been reached, the Permanent Possibilities in question have assumed such unlikeness of aspect, and such difference of apparent relation to us, from any sensations, that it would be contrary to all we know of the constitution of human nature that they should not be conceived as, and believed to be, at least as different from sensations as sensations are from one another. Their groundwork in sensation is forgotten, and they are supposed to be something intrinsically distinct from it.

We can withdraw ourselves from any of our (external) sensations, or we can be withdrawn from them by some other agency. But though the sensations cease, the possibilities remain in existence; they are independent of our will, our presence, and everything which belongs to us. We find, too, that they belong as much to other human or sentient beings as to ourselves. We find other people grounding their expectations and conduct upon the same permanent possibilities on which we ground ours. But we do not find them experiencing the same actual sensations. Other people do not have our sensations exactly when and as we have them: but they have our possibilities of sensation; whatever indicates a present possibility of sensations to ourselves, indicates a present possibility of similar sensations to them, except so far as their organs of sensation may vary from the type of ours. This puts the final seal to our conception of the groups of possibilities as the fundamental reality in Nature. The permanent possibilities are common to us and to our fellow-creatures; the actual sensations are not. That which other people become aware of when, and on the same grounds, as I do, seems more real to me than that which they do not know of unless I tell them. The world of Possible Sensations succeeding one another according to laws, is as much in other beings as it is in me; it has therefore an existence outside me; it is an External World. — Mill

I think there are two views that tend to be conflated that should be distinguished.

The first view features every ego in a sort of bubble of dreamstuff, some of which may [merely] represent a outer, 'real' world. This is what I find in varieties of indirect realism. Appearance is given with a kind of incorrigible, absolute intimacy. But one can never be sure whether it refers beyond itself.

The second view is perspectivism (ontological cubism, neutral monism, etc.) The 'transcendental' ego (the metaphysical and not the empirical subject) is the being of the-world-from-a-perspective. This means that the world is arranged spatially around the flesh associated with that metaphysicalsubject.As Mach would put it, there are decisive and especially prominent functional relationships between the elements constituting this special flesh (including 'inside' its 'mind') and the elements understood to constitute everything else.

https://www.marxists.org/reference/subject/philosophy/works/ge/mach.htmAs soon as we have perceived that the supposed unities " body " and " ego " are only makeshifts, designed for provisional orientation and for definite practical ends (so that we may take hold of bodies, protect ourselves against pain, and so forth), we find ourselves obliged, in many more advanced scientific investigations, to abandon them as insufficient and inappropriate. The antithesis between ego and world, between sensation (appearance) and thing, then vanishes, and we have simply to deal with the connexion of the elements a b c . . . A B C . . . K L M . . ., of which this antithesis was only a partially appropriate and imperfect expression. This connexion is nothing more or less than the combination of the above-mentioned elements with other similar elements (time and space). Science has simply to accept this connexion, and to get its bearings in it, without at once wanting to explain its existence. — Mach

To me this is a beautiful breakthrough to a kind of phenomenological field of neutral elements, prior to mind and matter that emerge later. We go back to an idealized state-before-differentiation. -

The Mind-Created WorldFor the convenience of others, I provide some crucial quotes from J. S. Mill.

https://oll.libertyfund.org/title/mill-the-collected-works-of-john-stuart-mill-volume-ix-william-hamiltons-philosophyI see a piece of white paper on a table. I go into another room. But, though I have ceased to see it, I am persuaded that the paper is still there. I no longer have the sensations which it gave me; but I believe that when I again place myself in the circumstances in which I had those sensations, that is, when I go again into the room, I shall again have them; and further, that there has been no intervening moment at which this would not have been the case. Owing to this property of my mind, my conception of the world at any given instant consists, in only a small proportion, of present sensations. Of these I may at the time have none at all, and they are in any case a most insignificant portion of the whole which I apprehend.The conception I form of the world existing at any moment, comprises, along with the sensations I am feeling, a countless variety of possibilities of sensation: namely, the whole of those which past observation tells me that I could, under any supposable circumstances, experience at this moment, together with an indefinite and illimitable multitude of others which though I do not know that I could, yet it is possible that I might, experience in circumstances not known to me. These various possibilities are the important thing to me in the world. My present sensations are generally of little importance, and are moreover fugitive: the possibilities, on the contrary, are permanent, which is the character that mainly distinguishes our idea of Substance or Matter from our notion of sensation. These possibilities, which are conditional certainties, need a special name to distinguish them from mere vague possibilities, which experience gives no warrant for reckoning upon.

It's a nice thing to point out. At any given moment we have only a small piece of the world before us. But this tiny piece is fringed or enclosed within a vast sense of the possible. I could walk downstairs and make some coffee (tho really I shouldn't). I could google X and go down that rabbit hole.

Some might say that possibility is a mere illusion, but I'd just say that 'actuality' is a favored kind of being, typically for practical reasons. I can't spend the idea of one hundred dollars, or the one hundred dollars that only might be there. -

Why is rational agreement so elusive?One of the perennial problems in philosophy is why a general consensus or rational agreement is so hard to come by on virtually all the interesting topics. — J

So much could be said on this excellent topic, but I'll mention a possible sampling bias approach. The problems with solutions we agree on are for just that reason boring. We don't need to talk about them. If genuine inquiry is the settlement of belief in the context of genuine doubt, then we should expect conflict on interesting topics. It's maybe a bit like the jury being out for a long time suggesting the intricacy of the case. -

The Mind-Created WorldAnyway, 'unknown unknowns' are "meaningless" and yet ineluctably encompassing, even constraining, of "whatever we think or say ... absent any mind" or not. What you call "meaningless", sir, seems to me the most meaningful thing we (philosophers & poets) can think or say about the world. — 180 Proof

I like to think about the encompassing as the darkness that surrounds a campfire. Or the dark woods that surround a torch on the trail. I've been walking through the woods at night lately with just a little Catapult Mini, which throws a tight beam, so I can get a look a the doe at twenty yards whose glowing eyes call my attention to her. I found myself next to five of these beauties on a trail just recently, and in the silence before dawn.

Anyway, I perceive (interpret) this surrounding darkness as a deep blanket of threatening-promising possibility. I hear a rustle in the leaves 'as' a kind of blur of maybe. On the level of feeling, I love this fringe or frontier. Exploration is a (the?) reason to be born (a post facto justification maybe.) The 'meaningless' is, in this sense, the creative nothing or the birth of meaning. Any ontology has to tell the truth about the 'Horizon', of becoming. Being is 'really' an endless becoming.

Here's a beautiful sentiment:

My objection, despite my embrace of the sentiment, is that this is a logical absurdity, a bad check. It's like that joke about twelve-tone music being 'better than it sounds.' The emotional value of such an impossible Frontier (what people like about the Kantian X ) is obvious to me, but any pointing beyond all possible experience reads like mystified paradox to me -- which may have genuine motivational value but still lacks content otherwise.Now, my own suspicion is that the universe is not only queerer than we suppose, but queerer than we can suppose. I have read and heard many attempts at a systematic account of it, from materialism and theosophy to the Christian system or that of Kant, and I have always felt that they were much too simple. I suspect that there are more things in heaven and earth than are dreamed of, or can be dreamed of, in any philosophy. — Haldane -

Neutral Monism / Perspectivism / PhenomenalismIn the same vein, Meister Eckhart dismisses space-time phenomena as 'literally nothing'. — FrancisRay

But I'd say it's metaphorically nothing, unless that 'nothing' is supposed to point at the framework character of space and time.

From my POV, the nothingness of things is tied up in their value being conditional. dependent on our investment in them. Straw dogs. I like the phrase psychoanalytic Platonist.'

Before the grass-dogs [芻狗 chu gou] are set forth (at the sacrifice), they are deposited in a box or basket, and wrapt up with elegantly embroidered cloths, while the representative of the dead and the officer of prayer prepare themselves by fasting to present them. After they have been set forth, however, passers-by trample on their heads and backs, and the grass-cutters take and burn them in cooking. That is all they are good for.

Consider also (?) Buddha's last words: Transient are conditioned things. Try to accomplish your aim with diligence.

Or consider The Fire Sermon.

"Monks, the All is aflame. What All is aflame? The eye is aflame. Forms are aflame. Consciousness at the eye is aflame. Contact at the eye is aflame. And whatever there is that arises in dependence on contact at the eye — experienced as pleasure, pain or neither-pleasure-nor-pain — that too is aflame. Aflame with what? Aflame with the fire of passion, the fire of aversion, the fire of delusion. Aflame, I tell you, with birth, aging & death, with sorrows, lamentations, pains, distresses, & despairs.

...

"The intellect is aflame. Ideas are aflame. Consciousness at the intellect is aflame. Contact at the intellect is aflame. And whatever there is that arises in dependence on contact at the intellect — experienced as pleasure, pain or neither-pleasure-nor-pain — that too is aflame. Aflame with what? Aflame with the fire of passion, the fire of aversion, the fire of delusion. Aflame, I say, with birth, aging & death, with sorrows, lamentations, pains, distresses, & despairs.

"Seeing thus, the well-instructed disciple of the noble ones grows disenchanted with the eye, disenchanted with forms, disenchanted with consciousness at the eye, disenchanted with contact at the eye. And whatever there is that arises in dependence on contact at the eye, experienced as pleasure, pain or neither-pleasure-nor-pain: With that, too, he grows disenchanted.

...

"He grows disenchanted with the intellect, disenchanted with ideas, disenchanted with consciousness at the intellect, disenchanted with contact at the intellect. And whatever there is that arises in dependence on contact at the intellect, experienced as pleasure, pain or neither-pleasure-nor-pain: He grows disenchanted with that too. Disenchanted, he becomes dispassionate. Through dispassion, he is fully released. With full release, there is the knowledge, 'Fully released.' He discerns that 'Birth is ended, the holy life fulfilled, the task done. There is nothing further for this world.'"

Note that I'm not claiming to be a Buddhist. Instead I'm getting a more universal (perennial?) idea of transcendence in terms of detachment. The world becomes a spectacle. We get 'distance' on it. We find ourselves less 'immersed in the object.' Heidegger calls this 'falling immersion,' the way that everyday life sucks us into its flow.

Personally, I don't pretend to have some cure for life. Nothing beyond the usual possible quotations of wisdom literature, the same old worthy proverbs. And this is mere amelioration. Life has its terrible face and its beautiful face. As far as I can tell, there's not much more to be sought or had than the continual re-attainment of an always fragile state of grace or play. We always fall off the horse again, find ourselves petty and resentful, or just tormented by a health issue, or forced to deal with a dangerous situation where stress (tho never panic) is appropriate.

Do we agree on this ? Or do you find something that radically 'cures' life in what you call mysticism ? -

Neutral Monism / Perspectivism / PhenomenalismExactly! And no-thing is precisely what we need as the ultimate for a systematic fundamental theory. Again, Kant proves this. At any rate, mysticism will make no sense to anyone who reifies time or space. — FrancisRay

I'd say that the concepts of time and space are one thing, but that moving my arm around of seeing an object in experiential space is another thing. In the same way, there's the concept of red which a blind person can master, and there's seeing red. Existence has (even primarily) a 'transconceptual' or 'preconceptual' aspect. Feuerbach correctly made a big deal about this sensualism. The world is not just thought. Thought is merely something like its intelligible structure. -

Neutral Monism / Perspectivism / Phenomenalism

Your tone has sometimes been, from my POV, too much on preachy / condescending side. I view us as doing something like science here. When you bash Wittgenstein (a primary influence on this thread), you sound a bit crankish (a bit envious-bitter maybe of the fame of the charismatic man .) And you speak of Russell thinking Wittgenstein was a fool, but that's contrary to the well known details of their story. I've read biographies of both. And this is not a matter of my sentimental attachment. If you recklessly speak contrary to the facts or tear down the 'mighty dead,' then that's a stumblingblock to your credibility. You ought to explain how all the other shrewd readers could be so silly as to get things so wrong. -

The Mind-Created WorldHere is Kant at (in my view) his most phenomenological and empiricist.

https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/4280/pg4280-images.html#chap78Possible experience can alone give reality to our conceptions; without it a conception is merely an idea, without truth or relation to an object. Hence a possible empirical conception must be the standard by which we are to judge whether an idea is anything more than an idea and fiction of thought, or whether it relates to an object in the world. — Kant

[chapter 78]

This 'good' side of Kant can be 'read against' his 'bad' side. And that's of course what happened with Fichte and Hegel and others, who followed this 'empirical directive' (Braver).

More in that direction:

https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/4280/pg4280-images.html#chap78Transcendental idealism allows that the objects of external intuition—as intuited in space, and all changes in time—as represented by the internal sense, are real. For, as space is the form of that intuition which we call external, and, without objects in space, no empirical representation could be given us, we can and ought to regard extended bodies in it as real. The case is the same with representations in time. But time and space, with all phenomena therein, are not in themselves things. They are nothing but representations and cannot exist out of and apart from the mind. — Kant

A little farther down than the first quote...

Here's some outright correlationism in Kant, a little further down:

The objects of experience then are not things in themselves, but are given only in experience, and have no existence apart from and independently of experience. That there may be inhabitants in the moon, although no one has ever observed them, must certainly be admitted; but this assertion means only, that we may in the possible progress of experience discover them at some future time. For that which stands in connection with a perception according to the laws of the progress of experience is real. They are therefore really existent, if they stand in empirical connection with my actual or real consciousness, although they are not in themselves real, that is, apart from the progress of experience. — Kant

To me the point is that objects get their meaning in or from actual and possible experience. But indirect realism is the wrong way to understand this, for this conflates the psychological or empirical ego with the deeper 'nondual' transcendental ego which is no longer more subject than object. This is where Wittgenstein in the TLP and Mach in The Analysis of Sensations and James in Does Consciousness Exist? are all helpful.

Note that Kant allows for what Husserl calls an empty or signitive intention. Well before Kant's time, people could form the idea of lunar inhabitants. And this fantasy or idea was itself real as such an idea. The 'picture theory' is relevant here, and it's a good analogy for signitive and potentially fulfilled intentions.

We might understand Kant and Husserl to be doing 'critique of language,' sorting intentions into buckets which include the square root of blue or round squares on the one hand and that which makes sense as potential experience on the other. J. S. Mill's phenomenalism is best understood in terms of elaborating what we mean by physical or worldly object.

We understand the couch to tend to wait there in the living room for us. Any human being will see it and be able to sit on it. But my daydream, indeed existing in the same world ( because it plays a role in justifications) is not similarly [ ''directly' ] accessible to everyone. So we have [only ] practical reasons for sorting entities into the generically available extended kind and the differentially accessed unextended kind. But all of these entities exist in the same conversational-practical nexus -- in the same 'rationalist' 'flat' (one layer) ontology. All entities (toothaches and tarantulas) have their meaning in a unified flow ofexperienceinterpenetrative arranged-around-sentient-beings worldstreamings. -

The Mind-Created WorldI add some crucial passages from the TLP. [Of course this is not at all about the authority of anyone, but a nod to and an employment of their admirable concision and focus.]

https://www.wittgensteinproject.org/w/index.php?title=Tractatus_Logico-Philosophicus_(English)#5The world and life are one.

I am my world. (The microcosm.)

The thinking, presenting subject; there is no such thing.

If I wrote a book "The world as I found it", I should also have therein to report on my body and say which members obey my will and which do not, etc. This then would be a method of isolating the subject or rather of showing that in an important sense there is no subject: that is to say, of it alone in this book mention could not be made.

The subject does not belong to the world but it is a limit of the world.

Where in the world is a metaphysical subject to be noted?

You say that this case is altogether like that of the eye and the field of sight. But you do not really see the eye.

And from nothing in the field of sight can it be concluded that it is seen from an eye.

Here we see that solipsism strictly carried out coincides with pure realism. The I in solipsism shrinks to an extensionless point and there remains the reality co-ordinated with it.

There is therefore really a sense in which in philosophy we can talk of a non-psychological I.

The I occurs in philosophy through the fact that the "world is my world".

The philosophical I is not the man, not the human body or the human soul of which psychology treats, but the metaphysical subject, the limit—not a part of the world. — TLP

A highlight:

Here we see that solipsism strictly carried out coincides with pure realism. The I in solipsism shrinks to an extensionless point and there remains the reality co-ordinated with it.

There is only world, but physics and ontology look to this or that aspect. of it, ignoring the rest, which can result in the confusion of making some of it a kind of unreal appearance. -

The Mind-Created World

You may be surprised like I was to see how much the brain already figures in Descartes, and therefore, presumably, in Kant.

http://www.classicallibrary.org/descartes/meditations/9.htm

...the mind does not immediately receive the impression from all the parts of the body, but only from the brain, or perhaps even from one small part of it...

...when I feel pain in the foot, the science of physics teaches me that this sensation is experienced by means of the nerves dispersed over the foot, which, extending like cords from it to the brain, when they are contracted in the foot, contract at the same time the inmost parts of the brain in which they have their origin, and excite in these parts a certain motion appointed by nature to cause in the mind a sensation of pain, as if existing in the foot; but as these nerves must pass through the tibia, the leg, the loins, the back, and neck, in order to reach the brain, it may happen that although their extremities in the foot are not affected, but only certain of their parts that pass through the loins or neck, the same movements, nevertheless, are excited in the brain by this motion as would have been caused there by a hurt received in the foot, and hence the mind will necessarily feel pain in the foot, just as if it had been hurt; and the same is true of all the other perceptions of our senses...

...as each of the movements that are made in the part of the brain by which the mind is immediately affected, impresses it with but a single sensation, the most likely supposition in the circumstances is, that this movement causes the mind to experience, among all the sensations which it is capable of impressing upon it; that one which is the best fitted, and generally the most useful for the preservation of the human body when it is in full health...

...when the nerves of the foot are violently or more than usually shaken, the motion passing through the medulla of the spine to the innermost parts of the brain affords a sign to the mind on which it experiences a sensation, viz, of pain, as if it were in the foot, by which the mind is admonished and excited to do its utmost to remove the cause of it as dangerous and hurtful to the foot...

— Descartes -

The Mind-Created WorldAgain from Eastern philosophy, you will doubtless recall the koan, made into a song, 'first there is a mountain, then there is no mountain, then there is.' That also is about the transition from naive realism (first there is..) to critical philosophy (then there is no...), and the 'return' to seeing 'things as they truly are' (then there is...) — Wayfarer

:up: -

The Mind-Created World

I wouldn't be surprised if the East had it first, tho I'd check the Christian mystics for a premodern grasp?As I think I've already mentioned either here or some other place - it's something I mention often - the canonical source for the idea of that 'the eye cannot see itself' is not something found in the Western tradition, as far as I'm aware. It's found in the Upaniṣads. — Wayfarer

FWIW, I think what Wittgenstein was getting at (and I'm defending) is some version of tat tvam asi. My own take might be dry and secular, relatively speaking, but I really think there's a discursive approach here. One can reason to the conclusion.

As I mentioned earlier, if consciousness is really just the being of the world, then the eye not seeing itself is the fact that being is not itself an entity (the 'ontological difference.') There's something like the actual 'thereness' of things and also our weird articulation of this fact, invoking the concept of being which is of course an entity. -

The Mind-Created WorldBecause we lose sight of the necessity of experience, we erect a false idol of science as something that bestows absolute knowledge of reality, independent of how it shows up and how we interact with it. ...

I tend to blame a sort of hitchhiking bad metaphysics rather than science itself. Good clean science just creatively postulates and confirms patterns in experience. And shuts its mouth about anything beyond. Mach was a first rate philosopher, for instance, not just a scientist, and William James was all kinds of things, including a serious psychologist. Note that Mach studied psychophysics. He wrote a beautiful little book about space, very protophenomenological, influencing Einstein of course. -

The Mind-Created World

Let me clarify. 'Looking right through' is genuine practical achievement, even while being an ontological disaster. I mean we literally train to ignore what phenomenology therefore has to excavate. So that 'what is ontically closest is ontologically farthest.' Too intimate, like water we swim in, clothes we wear. We forget that our body just always happens to be there, right at the center of the world that flows around us.

plaque flag

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum