Comments

-

"Free Market" Vs "Central Planning"; a Metaphorical Strategic Dilemma.We do have information, which is some small boats have a much higher chance of some people surviving. — boethius

But the trade-offs are not known or are presumed to be equal. Some boats means it is more likely that at least some people will survive but makes it more likely that some people will die, but the big boat makes it much more likely that everyone will survive and more likely that everyone will die.

If you're an individual who wants the best shot at staying alive, then you probably want the big boat. If you're someone who wants to ensure the continuation of the society and culture, then you want the small boats. Most people probably don't know which they would actually choose.

The strategic dilemma emerges precisely because we have two different strategies but we don't know which one is optimal. By establishing broad goals (long term survival of the genome vs short term survival of individuals) we can fathom which option is better, but we still don't know if the decision we end up making will be the best one. If people disagree about the importance of individual vs group survival, then there's no way to select a mutually acceptable strategy; because we're ignorant of what is to come, at some point, to some degree, we're just flipping coins or rolling dice in the very selection of our strategic methods.

I'm disappointed that no one is arguing for the free-market solution I propose to the problem: of letting people act with their own wealth, as it is my understanding the point of this thread was to contrast free market principles and central planning principles in this example. — boethius

The purpose of this thread was to put one of these strategic coin-flips front and center, the strategic dilemma I chose was only meant to facilitate the example (in hindsight, I focused too much on free markets vs central planning). -

Should A Men's Rights Movement Exist?I appreciate this thread, and I commend you for writing it as dispassionately as you have done. I also think I agree with the main thrust of the thread; there are indeed issues that men face which most women do not, and a social movement to address those issues is not unwarranted.

But I must object to some parts of your argument. Specifically this:

There's a reason why the intellectual leadership of the women's rights movement has always been exclusively female, even when men express sympathy for the feminist cause; it's because one cannot fully understand and appreciate the experiences of a sex without belonging to that sex. This holds true for men as well as women. Yes, a woman may know in an intellectual sense the challenges men face. She may know that men are the majority of suicides, the majority of work related deaths, the majority of combat deaths, the majority of alcoholics, et cetera et cetera. Doubless you've heard the men's rights spiel before, whether from reactionaries or true supporters. — Not Steve

It doesn't actually hold true; it mustn't. If we cannot sufficiently understand the ideas, feelings, experiences, and opinions of "others", then we're philosophically fucked up beyond all recognition (PFUBAR). Philosophical exchanges utterly depend on our ability to communicate our ideas, feelings, experiences, opinions, and beliefs, as well as the underlying reasons which have driven us toward them. If it works for other things, why can't it work for identity based suffering?

It's a clever line, to be sure: "How can you disagree with me when you do not share, and therefore cannot comprehend, my suffering?", but it's a classically fallacious appeal to authority (the authority of race or gender, which is racist/sexist).

Meanwhile, in the real world, race and gender demographics do not compose monolithic groups who all share the same set of experiences. For instance, some black individuals experience certain forms of racism, some black individuals experience other forms of racism, and some black individuals experience no racism. Are each of them therefore unable to comprehend or understand the position of the others?

Shared experience can lead to shared understanding, but what of shared experience that leads to mutually exclusive understandings? (doesn't that refute the whole argument?). What of our human ability to empathize and sympathize with the plights of others? What of human imagination?

The back-of-the-line approach (for non-marginalized identities) that too many contemporary social justice movements organize around is just classic and arbitrary segregation based on race or gender. Outrage is king these days, and objecting to the color of someone's skin or the shape of their genitalia is alive and well as a form of political motivation; the pendulum has merely swung in a novel direction.

Is more identity politics really the answer? Where ideas are apparently correct only in proportion to the correctness of the various orifices, sexual preferences, and skin pigments of the great and terrible apes who espouse them?

My avatar is a representation of a snake eating its own tail. Fourth wave intersectional feminism was my inspiration in adopting it: it's a rare and extreme phenomenon where people set out to accomplish something (in this case, to bring about social justice and equality), but the effect of their methods actually winds up subverting and dismantling their founding objective or principle. Intersectional feminism seeks to create justice, but they do it by confusing us with sloppy and fallacious rhetoric (like the "lived-experiences" bull-shit) and then by inherently dividing us into in and out groups (which leads to conflict that can prolong/exacerbate inequality).

It's tragic irony at best, and reprehensible ignorance at worst. We don't need leaders whose immutable features have symbolic and therefore rational value, we need leaders with good ideas. In trying to remedy "bad feelings", we would be remiss to allow "feelings" to replace reason and evidence.

In summary, yes, many men experience the effects of inherent or systemic sexism in ways that most women do not, but it's not so simple. Some men are free or almost entirely from any and all social burdens placed upon them (eg: born rich), but so too are some women, some gays, some blacks, some transsexuals, etc... We have problems, but they aren't rigidly defined along the lines of race or gender. Much more severe are problems that don't see pigments or sexual organs/desires (eg: poverty), and it is in the solving of those more fundamental problems that the social disparities we now decry will actually be solved.

Not being sexist isn't going to change the religious beliefs that see to the mutilation of infant genitalia (it is estimated that more than 100 babies die in America each year due to circumcision related complications), and it isn't going to change the fact that drafting women into an infantry force could never work. It isn't going to change that fact that many women will seek male partners who assume the responsibility of provider, or generally that many men will always look to compete with one another (to the detriment of those males who are more interested in cooperation). I might catch flack for saying this, but women tend to make better care-givers than men. Courts should be giving men a fair hearing when they seek custody (the kid should get the best parent), but that also means women will tend to be the victor in such disputes. The solution to all this is to stop thinking of ourselves as team-oriented groups (we're not), and to start thinking of ourselves, and others, as individuals. To do otherwise is to adopt classically anti-humanist racism. It's anti egalitarian and it's blatantly not allowing us to morally progress as a society. -

Philosopher Roger Scruton Has Been Sacked for Islamophobia and Antisemitism

I don't want to step too far away from the issue, but I've been flailing against this kind of over-sensitive censorship for a few years now.

When thinkers/writers/academics/speakers that we value listening to are de-platformed or otherwise marginalized (unfairly), it's not just the individual being de-platformed that is harmed, it's us as well (our right to hear the ideas of others).

Free-speech is also meant to protect our right to listen if we want to. I'll be the first to point out that nobody is entitled to the private platforms of others, but we've managed to create a situation where individual private platforms (and governments) are absolutely terrified of being socially sanctioned for making an incorrect decision about who should be allowed to use them (making them inaccessible in practice to people with opposing views).

Nobody cares about seeing both sides of an argument anymore. They want the other side to go away, and if they don't get what they want they'll make unending fuss. The result is that platforms now have to cater to specific political niches, because exposing their audience to opposition would garner outrage from either polarized end. Are there any major news networks that still have politically diverse viewer bases?

It has a very chilling effect on democratic health. Instead of finding a coherent middle, the chasm between the left and the right just keeps growing... -

sunknightToo many flies in the ointment can lead to unpredictable side-effects.

I made a thread some time ago about what we could do to capitalize on the many low-quality posters that darken our doors. I proposed a less-visible low-quality section which could work as a kind of limbo for those posters who would otherwise be banned. It could even be replete with guides about how to make coherent and quality posts.

The thinking was that if we could retain and train these people, our community would grow and become enriched, but it's asking a lot from the site developer and it's a bunch of headaches for moderators.

It's also possible that we don't need a massive community, or that increasing our size would create more burdens than benefits. -

On intentionality and more

"Philosophy" can be so broad a category that I'm necessarily generalizing when I say it tends to use reason/logic/evidence as opposed to other vectors of inquiry.

These are much more common to (good) epistemology than philosophy in general, but good philosophy also tends to have good epistemic foundations. Reason and evidence are highly persuasive, but more importantly, are highly reliable means of improving understanding or predictive power (and they happen to be even more persuasive once we recognize how reliable they can be). -

On intentionality and moreThis seems to make quite an epistemic leap from the evidence. What we have from history is that - what was more persuasive in the past does not always continue to be most persuasive contemperaneously. Which is most 'true' requires substantiation through one or other epistemic truth theory. — Isaac

Fully disentangling truth and persuasion is probably a very tedious affair, but suffice it to say: in so far as "truth" of whatever caliber is actually discoverable, it may differ from what is persuasive to us.

It's an admission that we might be wrong; that belief does not arbitrate truth (such as it does in a jury-case/court setting). We normally think of "philosophy" as a set of theories and knowledge-products waiting to be consumed, but there's also philosophy the solo-sport, which is a slow process that involves recognizing past, present, and possible future errors as we continuously strive toward better truth and more accurate or useful understanding. A good philosopher must access "truth" through that much longer process of substantiation rather than the immediate suasive whims of their potentially fallacious mind.

Maybe it's not persuasion per se that I'm wary of, but rather the common primitive varieties (i.e: fallacious appeals) that give me pause.

Time to thoroughly examine all the evidence seems to be the rub. Reason and evidence based persuasion takes much more time, and is much more reliable than the results of fast and loose conclusions. -

Philosopher Roger Scruton Has Been Sacked for Islamophobia and AntisemitismHe didn't paint the roses red enough.

Off with his head?

Fast and loose are our reactions, and atonal rage is our rhythm.

The Kafka trap springs again... -

What can't you philosophize about?We can philosophize about "everything", which includes nothing.

OR

If you can't philosophize about it, it's ineffable, or inaccessible in the first place, hence the titular cannot possibly answered. -

On intentionality and moreIsn't it fantastically obvious?

The good lawyer focuses on persuasive power while the good philosopher focuses on predictive power.

Under the adversarial justice system, prosecution and defense attorneys both do their best to win their case, with the overall thinking being that truth or justice will tend to emerge as the result of their conflict and competition (in more or less the sense that truth tends to emerge from debate). A good defense lawyer will try to get the lightest sentence they can for their client even if that defense lawyer thinks their client is guilty and deserves to get a harsh sentence.

Philosophers sometimes do the same as a consequence of dialogue and debate, but history and experience shows us that what is more persuasive is not always more accurate or more true. That truth tends to be more persuasive than falsehood could be mere evolutionary happenstance; and since we're not caught in a dilemma where we need to make a fast and reliable decision about important matters (which is why we use courts), we can achieve more reliable standards. The pursuit of "truth" impels us toward the best standards we can derive. -

On intentionality and moreMeaning, that some appeal to authority is required, which in my opinion goes against the very ethos of philosophy. And they call economics the dismal science. — Wallows

Square one is logic, reason, and evidence in pursuit of truth above persuasiveness. That's the authority it appeals to by definition (or at least under most philosophical roofs).

How do you present either of those traits in a post-modern, hyper-normalized world? — Wallows

With arguments that are simultaneously persuasive and true. -

On intentionality and morePeople are saying things in an attempt to persuade the other to change their positions (moral suasion), right? (the intent of persuasion itself matters to us as individuals).

While this is true to us as individuals with the subjective opinion that we are more correct than others, philosophy has demanding standards about the method of persuasion it prefers to use. It requires that something be persuasive for rational, logical, or otherwise evidence based reasons (we want/pray/wish that truth is more persuasive than falsehood).

There's a whole world of sophistry out there whose only utility is that it is highly persuasive, and people appeal to them every day (more and more in the quick-rhetoric-slinging world of online media). But as philosophers, we're supposed to recognize them as fallacious appeals and seek more reliable arguments and conclusions.

In theory it is more important that we are correct than it is important we are persuasive, but neither is useful without the other. -

On intentionality and moreI would say that intent is actually irrelevant entirely. Authorial intent (intended meaning) can be important, but the intended ramifications of statements has no bearing on whether or not they are true.

Ideas and arguments must stand or fall on their own merit, not the merits of the speaker, or the merits of their intentions.

If people are sharing pointless or irrelevant ideas and arguments which happen to be technically true in some respect, just ignore them as irrelevant and pointless to interact with. -

The Problem of “-ism” on ForumsA middle section of two extremely opposite aspects is inevitable to surface into a discussion by consequential considerations. Evaluating proposed dispositions of each aspect, it is inevitable that people would want the established problem to be resolved by another aspect that's just: moderate, common, the exact middle. For example, atheism and theism = agnosticism. Determinism and free-will = compatibilism. Would that middle section, which is inherently not any different from an ism, be a problem as well? — SethRy

Yes there's still a problem, because the undefined middle will be subjectively warped according to how we each conceive of the poles (either end of the spectrum).

For example, you stated that agnosticism is directly in the middle of theism and atheism, and while in some sense that is vaguely true, atheists do not see it that way (we see atheism as the refusal to take a positive position, not a denial of one). For most atheists, agnosticism is on an entirely different spectrum (an epistemological spectrum, not an ontological/existential spectrum) because we reject the belief-disbelief dichotomy outright. Agnosticism is one of the most frequently misused words in discourse about gods, so I can hardly blame you for missing its specific meaning. It is actually "the positive belief that evidence pertaining to god(s) is unavailable", and It only becomes important to clarify on the journey towards soft-atheism because as a theist there is no practical difference between someone who denies your god because they believe it does not exist and someone who denies your god because they have no proof or good evidence that it does exist.

Consider your stance toward Zeus. You cannot prove Zeus does not exist (not without some effort), so you certainly don't "believe in" Zeus, but do you actually believe Zeus does not exist? If you said yes, and I accused you of having no actual proof, how would you respond?

The more controversy there is surrounding a label, the better you would do to avoid it unless you're argument is semantic in nature (i.e: trying to reclaim a word). "Isms" usually point to broad categories of belief, making them inherently ambiguous. It seems like a situational dogma because "isms" suffer severely from the problem of ambiguity, but really it's a fundamental problem of all language.

Post-modern thinkers like Foucault will tell you that "the gap between the intended meaning of the author and the received meaning of the reader can never be fully bridged", but it's not an insurmountable problem (the post-modern clutch has always been melodramatic). We just need to be clear enough... -

The Problem of “-ism” on ForumsCategorical labels of all kinds are just short hand meant to make communication easier, but in the context of "philosophy" where precise meaning makes a difference, they can actually make communication more difficult. (i.e: someone uses a label to describe their political persuasion, but their interlocutors have an entirely different conception of what those political beliefs might entail).

This isn't just a problem with isms, it's a problem with all kinds of words. To mitigate it, sometimes it is better to take the long-winded approach by avoiding labels in exchange for a description of the thing the label is intended to point to. Your writing will become less concise, but your intended meaning will be much clearer.

A good example is a word like "gender", which can lead to ridiculously prolonged miscommunications. Sometimes people are referring to chromosomes, sometimes they are referring to phenotype or to hormonal balances, sometimes to gender roles, and sometimes to personality or to "identity". If we had different words for all of these different meanings there would be less miscommunication, but it will take time for the language market to fill those relatively new gaps. -

Jussie Smollett’s hoax an act of terror?Does anybody actually know why he was let off? — NKBJ

The police didn't want to let it go, so it must have come from one of the higher-ups. The trial would have been expensive and retarded, and likely gone on to inflame racial tensions further.

There's also a chilling effect that happens when you throw the book at people who make false police reports: actual victims then fear to report actual crimes.

Ultimately the cons of prosecution, for the city, (or whoever interceded) outweighed the pros. -

Why do christian pastors feel the need to say christianity is not a religion?Headline: Christianity Declared 'Not A Religion'; Thousands of Preachers Suddenly Open Churches In Panama!

-

Why do christian pastors feel the need to say christianity is not a religion?Almost nobody is saying that, especially pastors (tax purposes).

Why would anyone say it? Because they wan't to frame it as factual truth probably. It's a reactionary position brought on by science-envy. -

What are our values?

Some of us will have conflicting values, but because we've all sought out this forum, it's likely that we all share the value of wanting to learn.

Speaking for myself, one of my fundamental core values is learning in and of itself. I enjoy learning on an intrinsic level (it's pleasurable), and I also value learning because of the way knowledge positively relates to just about every other possible value.

The first time I formulated an answer to "what is the meaning of life?" it was something like "I don't know, but I enjoy learning, and maybe one day if I learn enough I'll figure out what the meaning of life is; until then, I'll just keep learning."

Beyond "learning", I value survival; freedom from oppression, pain and discomfort; the freedom to pursue my own interests; and the health and safety of others. (The requisites of eudaimonia).

You mentioned specific values like loyalty and honesty, and in general I tend to agree, but to be strict, I only value loyalty and honesty because they support the values I just mentioned (among other fundamental values), not because honesty and loyalty are inherently good. In other words, there is a time and a place for disloyalty, as well as dishonesty; they are means to an end, they are not ends.

Is there a difference between a virtue and a value? Be there hierarchical structure? -

Are prison populations an argument for why women are better than males?I think he is reacting to a particular choice of language: "inferior". The thrust of the OP is an inquiry into why there are disparities between gender prison population numbers (an excellent question to ask, in my opinion), but framing it in context of superiority/inferiority (though motivating) has way too much baggage.

-

Are prison populations an argument for why women are better than males?Is being tall a deformity?

Being tested out in the real world (to find out what deformity works (i.e: to find out who can more successfully reproduce)) is the trial and error I'm referring to.

The emergence (the sustaining of) and slow optimization of new "deformities" happens because inter-generationally they result in higher reproductive success. -

Are prison populations an argument for why women are better than males?The filtering of "what works" that happens over generations is the driver of evolution. It adapts through trial and error.

-

Are prison populations an argument for why women are better than males?Again, you didn't just say that adaptive variation exists, which I would have no problem with, you gave a detailed description of specific body differences between men and women and claimed they were caused by specific differences in their social and biological roles. — T Clark

You only appeared to object to a particular sub-point involving height, which wasn't actually about sexual dimorphism. That women exhibit a smaller variance in height, and a smaller average height, than men is the observation that the main thrust of my post attempts to explain (the point in question was explaining the context for adaptive divergence). The raw observation is undeniable, and the fact that men are capable of reproductive success across a wider range of heights really isn't that controversial. Evolutionary thinking along these lines is never a certainty, and though we often have mathematical models that can back them up, they're still quite persuasive without them.

Your posts always seem as if I'm attempting to oversimplify things, when in reality my intention is to provide models and questions that beget a deeper level of attention to complexity. Why is there more variance in the height of men than the height of women? You can say it's all directionless happenstance, and that we can never begin to know, but I say an evolutionary perspective (a la commonly cited reasons for sexual dimorphism) can get us started down a usefully predictive road.

Show me the skulls of a male and female of a species I've never encountered, and I might be able to predict something insightful about the behavior of the organism. Are the skulls identical in size and shape? Are there any unique features? Is one thicker than the other? If skulls are identical, we can surmise that the both the male and female of the species have a similar phenotype. That they both share the same general form suggests that they both perform the same set of tasks in general. "Pair-bonding" species which involve both parents contributing to the rearing of offspring generally have males and female that are hard to distinguish from each-other. "Tournament" species which involve male-male competition for access to reproductive females (and where the male might not contribute to the raising of the offspring) typically have very high levels of sexual dimorphism. There are exceptions, and a spectrum of causal factors to consider (humans are a notable in-between; we exhibit a high variance in sexually dimorphic traits), but at least we have something to work with.

It is my understanding that this is not true, so I checked. The underpinnings, infrastructure if you will, of reactivity to light have been around since just about the beginning. The photoreactive proteins and structures and some of the light-reactivity related genes are present in some of the currently living organisms near the split between vertebrates and invertebrates. It's not as if vision just popped into existence in completely unrelated organisms by coincidence. There was history involved. — T Clark

Photosynthesis was around since nearly the beginning (or maybe at the beginning), but photosynthesis does not an eye-ball make. You start with a patch of photo-sensitive cells on or near the skin of an organism, which can confer the advantage of knowing what direction light is coming from. Over many stages of subsequent alterations, each with their own adaptive benefit, refined eye-balls emerge. Different styles of eye-ball have followed similar evolutionary steps across a range of different organisms. Is any of this objectionable?

Evolution by natural selection, as envisioned by Darwin, only represents adaptation by specific organisms to changes in specific local environments. There is no master plan or pattern. No tendency. Dolphins and sharks both have fins and are streamlined, but it's not because nature tends toward fins and streamlining. Evolution has no direction. No guiding principle. — T Clark

The guiding principle is "what works" in the long run. "Fins" are a trait we tend to see in creatures that have evolved in aquatic environments. The principles are ultimately physical; fins happen to work well in water to create locomotion.

"Evolutionary convergence" (the tendency for similar adaptations to evolve in different organisms that exist in similar situations) is not controversial. -

Are prison populations an argument for why women are better than males?And no, evolution doesn't have "vague tendencies." It doesn't have any tendencies. — T Clark

Eyeballs have evolved separately dozens of times in the grand history of life on earth. We might say that evolution has a tendency to innovate and refine eyes when evolving life finds itself in a light filled environment. Creatures found in isolated caves often have no functional eyes because they have never needed to evolve them in the first place, or because their inter-generational lack of use has degraded the eyes their ancestors once had.

Evolution is the very tendency of life (or things) to adapt and optimize, to change, according to the environment it finds itself in. -

Are prison populations an argument for why women are better than males?"Plausible" has any number of connotations. One of them being possible. The context of my explanation made it clear that I was taking up a narrow focus for the sake of the discussion (the point I made). I even made a secondary post just to clarify that fact.

You didn't present it as a possible, plausible explanation. You presented it as fact. — T Clark

You're objecting to a moot point (I might be wrong about the specific causes of height variation, but my point is that adaptive variation exists); I said we should expect to see height correlate with environment, and we do! I'm not wrong that we do see differences in the height distributions between different ethnic groups, and I never suggested that the causal factors I supposed are the only ones in existence. That said, environment must be a factor of some kind in genetic selection for height. You haven't added to, or taken away, anything meaningful from my original post. -

Are prison populations an argument for why women are better than males?I'm not rendering a full explanation of height, (nor criminal deviance), but i AM providing an important piece of the explanatory puzzle. Presumably there's much more to the adaptive story of height (which is about 80% genetically determined), but it's at least highly plausible that greater height enables greater top speeds (more useful in plains) and hinders mobility in dense brush (a hindrance in jungles). I'm not trying to draw firm conclusions about the adaptive utility of height, I'm trying to show why trait variation in men can be more liberal in order to gain a species wide adaptive advantage.

-

Are prison populations an argument for why women are better than males?I know you're using this as a metaphor, but still, evolution don't know nothing. — T Clark

But it still has a kind of "predictive power" that essentially emerges from the "stored data" which DNA represents. -

Are prison populations an argument for why women are better than males?I am very skeptical of this type of simplistic story-telling about evolution. There is not this sort of one-to-one correspondence between traits and evolutionary "causes." Your explanations don't seem very plausible to me. — T Clark

They're not my explanations, I'm just relaying the fruits of applying an evolutionary perspective to human behavior. Sexual dimorphism and changing frequencies of traits are a part of the fundamental building blocks of Darwinian evolution (well described and well observed):

If traits are heritable, if they can vary in degree (such as height), and if they impact future reproductive success, then natural selection will act upon them.

That DNA has an impact on behavior is not exactly debatable. You can try to argue that nurture is more important in determining psychological outcomes, but you can't argue that the principles I've outlined don't also apply. -

Are prison populations an argument for why women are better than males?I should temper the above by pointing out that we absolutely must consider environment in addition to genetics. Genes do absolutely nothing without an environment to express in, and changes in environment (eg: pre-natal hormones, diet, climate, culture, etc..) can have wild ramifications on the shape and behavior of the resulting organisms.

DNA plays an undeniably important role, but so too does environment. -

Are prison populations an argument for why women are better than males?I mean, how do you explain that? — Wallows

There are so many factors that warrant discussion to fully answer the question of why there are fewer female prisoners than men, but I can at least start you off with an explanatory evolutionary perspective:

As @Bitter Crank pointed out, populations of men and women have a certain amount of internal "divergence" (a tendency to display varied traits across different individuals). Let's assume for the sake of discussion that people who are in prison are there because of ultimately genetically programmed deviance (we can leave the nurture discussion for another time; I'm dealing with the "nature" side).

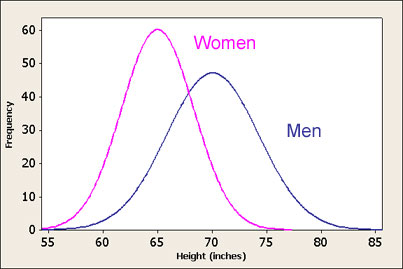

Just about any human trait can be measured in populations as a distribution curve (statistically). Let's use height as an example. On average women are shorter than men, but men have more variance in their height. Their distribution curves on a graph charting the frequency of different heights look like this:

Why is there more variation in the male population you ask? There's a fairly strong evolutionary argument that helps explain it:

Women have wombs (an evolutionarily critical human organ), and wombs have certain physiological requirements to be functional: hips need to be a minimum width; metabolism needs to be capable of supporting pregnancy, etc... On top of this, women are typically the primary child-rearers, and rearing children demands a particular kind of personality to be successful (patient, caring, etc...) (now we're getting closer to the crux of the thread).

The set of tasks that evolution is optimizing women for don't change a great deal; much of their energy is imperatively invested in a body that can support the necessary sex organs. Meanwhile, men of any size, shape, and personality are capable of having a working penis, and using it. Instead of growing big tits and big asses, evolution is free to roll more dice with us in order to ensure that inter-generationally we can adapt to a wider set of changing environments that require different kinds of tasks. For instance, height is beneficial in mostly open landscapes (savannah, plains, hills), but it is decidedly not useful in dense forest or jungle (for obvious reasons); we should expect to see height correlate with environment in this way, and we do!

In short, men are expendable compared to women (only a few men need actually reproduce, whereas our population numbers and growth are bottle-necked by the number of available wombs), and evolution therefore uses them as such.

It's true that men and women have the same average I.Q, and it's also true that there are more extremely high IQ men than there are extremely high IQ women (and there are also more men of extremely low I.Q). Evolution knows that women need to be within a certain range to be good parents, but it doesn't know what kind of man will be most optimal for the future environment, so it covers more bases.

If crime is at all the result of genetics, then we should see more male outliers than females. (and what is a criminal BUT a behavioral outlier?).

--------

If this perspective interests you at all, there's a wider field of study with many such useful models that are really highly insightful. I've reccomended this (free) Standford lecture series here before, and I'm proud to do so again!

-

Is criticism of the alt-right inconsistent?Isn't it fascinating though?

Perhaps it's because I've spent so long observing the contemporary rituals from the safety of wild blinds, but the overall evolution of "feminist" thought (into the abstract mosaic that it is today) is like a great and terrible kaleidoscope of emotion and angst.

Just like I said. Stronger medicine. Dworkin is that tablet of acid you've been saving; that old school cure. The fast and loose nature of social media has basically widened theOvarianOverton Window to the point that just about any ridiculousness is acceptable (so long as it attacks fashionable targets)

"All penetrative sex is rape" isn't rationally too far off from "all whites are racist". Hyperbole within hyperbole. As the article you linked notes, Dworkin's approach of being "intentionally" bombastic is something that modern rad-fems often claim is necessary for a message to be heard. Trouble is sarcasm doesn't usually read well in text, and so Dworkin's burgeoning proponents take it all seriously. -

"Skeptics," Science, Spirituality and ReligionAny reason these can’t these be held as base values and science given the authority to develop normative ethics? — praxis

Relative to our agreement on those starting values, we can and should use science to assist our decision making, but it will only hold "true" relative to those agreed upon values.

The realm of debate regarding normative starting points is much more lousy with variation than mere human happiness. We are able to carry on in practice because there are nearly universally agreeable values, but exceptions and objections stick out like sore thumbs in philosophical debate. -

Is criticism of the alt-right inconsistent?Keep bringing it up. Is Andrea Dworkin a 3/4th wave feminist? I encountered her loathsomeness back in the 1980s. Quite repellent. She's still around; she gotten written up in some paper recently. — Bitter Crank

Ah! Ye olde "sex negative feminism". What an anti-gem! According to wiki, Andrea Dworkin died in 2005, but the bloated corpse of her ideas oft drift ashore on a spat isolated beaches.

80's And 90's feminism (specifically pre-social media) was at first a wild west of thinkers who were all trying to take feminism to its next radical level (coincidentally at a time when the word "radical" had connotations of cool and awesome). The high of the 60's and 70's was wearing off, but we still hadn't reached utopia; the market demanded stronger medicine. Initially there were dozens of formalized feminist camps, each with their own focus and concerns (eg: some were concerned with sexualization of women, some were concerned with gender equity in political representation, some were concerned with keeping the traditional family together, some were concerned with dismantling necessary conformity to the traditional family unit; some were were concerned with women of color, some with women with disability, some with the oppression of ugly women, of hot women, of fat women, of skinny women; you name it.). This landscape demanded some sort of meta-feminist theory to explain it all, which is where "intersectionality" comes in. It's the idea that the amount of oppression a given person experiences exists theoretically at the intersection of their various "disadvantages". On its own this idea is actually compelling and potentially useful, but the hasty conclusions that have since been drawn from it are now dominant for perverse reasons.

As the pile of feminist causes grew, it generated a marketplace of competition. The more compelling a cause (let's call them "grievances") the more reaction and support it generateed, the more students it attracted, the more their proponents gained tenure. A "progressive stack" emerged where the prevalence and persuasive strength of a given theory was primarily based on the emotional strength of the grievance it sought to model or remedy. Feminists like Dworkin were given more than soap-boxes strictly because of the emotional strings they pulled (there were no tangible academic strings on her ideas whatsoever). Overtime things seem to settle down a bit, and some of the more ludicrous grievances either fade away or lead to fringe schisms within and between ostensibly feminist academic departments. By the late 90's, contemporary feminism at large actually seemed to have its head on straight. There was a global focus on helping women (and everyone) stuck in oppressive old world conditions, with sensible focus on the plight of women vs men in western society. Tucked safely away in my Canadian public school, I was taught to believe in the basic principles of the civil rights movement, and I was given a common sense description about what hatred, racism, sexism, and discrimination are, and why I should not engage in them. Radical feminist theory of the 80's and early 90's was nowhere to be seen (granted, radical feminist literature was still being produced, it just held no real political or cultural purchase).

At some point in the late 2000's, catastrophe struck. Social media created a realm of communication that has never before existed: everyone can talk to everyone (or at least, many can talk to many). Like a macrocosm of 80's feminism, the myriad of confusion and disagreement created a marketplace that selected for emotionally persuasive power as opposed to rationally persuasive power. Basically it's ancient Greek sophistry 2.0: whatever is persuasive is therefore true. And this environment was like a bull-horn for the entire body of grievance studies that departments had been built up since the 80's. The most emotionally provocative theories were given the biggest bull-horns, and the resulting market share they were able to capture became the wave of "social justice warriors" gone wild that has plagued the 2010's.

Interestingly, sex-negative feminism does re-emerge every so often, but it is quickly and vehemently put down by sexually liberal camps who take a different view of things (sex-negative theories are more repulsive today than they ever were, but in the new online environment, anyone with half a brain can make controversial statements and get undue attention). To be precise, I think Dworkin's ideas are largely set apart from the rest of 3rd or 4th wave feminism (post 70's feminism), but they're definitely in the same unkempt zoo.

The reason I say that is that by partnering across racial lines, they are the change they want to see. A very unkind critique of BWMT was raised back in the 70s (it's just white guys out slumming). Today the criticisms would be harsher, grinding on power differentials, oppressive roles, exploitation, reverse racism, etc. — Bitter Crank

They would say that the inherently white assumption that men of color should have sex with white men is an extension of colonialism into queer performativity, and that the very idea undermines their agency, mirroring the master-slave relationship of the 1800's. If as an organization they had politics that were in any way not fashionable to contemporary grievance politics, you can bet your ass they'd be problematized.

I'm white and I plead NOT GUILTY, your honor, and I am not a white-hyphen-something, other than live-white-male. I only know (for sure) 1 white supremacist--a brother in law. We don't spent much time together--I've been banned for a good 15 years, at least. I'm not a separatist or a nationalist. On the other hand, I like white western culture (English, French, Mozart, Van Gogh, all that). I don't feel guilty about the Amerindians (I feel deep regret) nor do I feel guilty about slavery--again, deep regret -- really. What history and anthropology tells us is that we are one vicious species, as often as not, and we have all employed similar strategies to promote our particular aspirations.

Personally, I think we would be farther ahead of we stopped talking about racism, sexism, homophobia, transphobia and so forth. What we are saying a good share of the time is social justice boiler plate, and it prevents us from seeing nuance or progress. Like, do Somali's in Minneapolis run into racist attitudes? Sure they do. On the other hand, a Somali was elected to Congress from a Minneapolis district that contains more Christian and Jewish voters than Somalis. We also elected a [home grown] Moslem as Attorney General, after he had served in Congress. White (mostly Democrats) people electing a black [home grown] Moslem is progress, no matter how you slice it. — Bitter Crank

Somehow we've become over-sensitized to grief, and desensitized to progress on a psychological level, which is in part why ideas like "white guilt" affect some people so severely (the more vehemently you deny it, the more proof of your white guilt you display!). We've focused on how evil racism, sexism, etc, are to the point that when a child encounters it for the first time in their life, they crumble to the ground while screaming bloody murder.

It really doesn't matter how far we've progressed as a whole, so long as there are a noticeable number of racist or sexist individuals out there, they can be cherry-picked as representative of the system, and to encounter one in real life is to encounter Satan himself. There's no room for nuance when every available emotional chip is at stake (except the positive ones). When Kim Crenshaw coined "intersectional feminism" and envisioned a system that sought to fairly empower victims, she didn't realize that people would therefore have perverse incentives to establish themselves as victims.

And that's a part of the political world we now live in. Victim-hood can mean everything, and if you disagree, you might just get yelled at until you go away. "Whites as victims" from the alt-right is just inter-sectional feminism by another name, and with a different victim hierarchy.

People don't have time to consider things like improving merit based diversity in outcomes, and improving levels of acceptance of and between different identity groups; what's compelling now?

Nothing motivates like a good problem. -

"Skeptics," Science, Spirituality and ReligionImho, advice like "treat others as they want to be treated' is not advice about what we should do for somebody else, but instead advice regarding what we can do for ourselves. — Jake

And we're very greedy bastards indeed! We might not realize it, but cooperating instead of competing can lead individual success that is many orders of magnitude beyond what we could get if we were in strict competition and conflict.

Many people come to religion in crisis when they've spent their lives earnestly trying to make "me" as big as possible and then discovered much to their horror that it doesn't accomplish the desired goal. — Jake

It might be fair to say that everything we do is in the pursuit of pleasure and happiness (and in flight of pain or despair). For some people, religion is really an ultra convenient way for them to realize stable happiness. Whether or not they are empirically justified is of secondary concern to me. Religion is definitely not for me (and it doesn't seem to for you either) but we ought remember that our worldview might not be beneficial to everyone (in theory and in practice). Some people just don't work without what we perceive as grand superstitions. -

"Skeptics," Science, Spirituality and ReligionThere are scientific theories about moral development and what constitutes moral intuition and reasoning. Also, the results of moral choices can be measured. Suffering can be measured. — praxis

Descriptive theories, not normative theories. They may have indirect normative implications, but they cannot arbitrate human values. (we can describe moral reasoning with a scientific approach, but we cannot derive normative implications about what our starting moral suppositions or moral conclusions ought to be). To do that we need a starting value that is ultimately subjective to individual human minds.

As for religion being the arbiter of moral values, it proves to be remarkably moldable by those in the position to use it. — praxis

Absolutely, but I'm seeking to frame the boundaries of religious knowledge, not to broadly qualify it. That said, corrupt as most of all religions seem to be, some religious moral tenets are actually quite truthy from any reasonable perspective. We don't need Jesus for "treat others as they want to be treated" to make sense, but "Jesus" wasn't wrong... -

"Skeptics," Science, Spirituality and ReligionAs I said, I think it's my responsibility as a turd in the swimming pool to express myself more clearly. I think I've gone as far as I can in this thread. — T Clark

Very well. But for the record I'm still optimistic that we can both get something useful out of this exchange. Despite the mutual rib-shots (I do enjoy them), I think overall we've been sufficiently intellectually charitable and honest, and though I'm not that much closer to understanding the roots of your position, I'm still quite interested in it.

If you do happen to make a new thread on the subject, count me in. -

"Skeptics," Science, Spirituality and Religion

Religion in practice covers intellectual territory that science can never tread upon, such as determining the starting moral values that individual humans should choose. Science is inherently more narrow minded because it has intentionally blinded itself to the immeasurable and unobservable; not to deny their existence, but instead to place focus on the measurable as the specific puzzle it seeks to solve.

Science has yet to generate any accepted moral oughts from a physical is, while religion has basically generated all of them from meta-physical is's. The very ontological nature of the "knowledge" that religion and spiritual interpretation seek to provide can be fundamentally different from the nature of the "knowledge" that science seeks to create/discover. Science wants physically descriptive and predictive power over the world of physically measurable observations (so if we can't measure it, we can't do science on it both by definition and in practice). Religious knowledge, under forced comparison, seeks to do a myriad of things. Sometimes it's meant to control or guide human objectives (as well as their decision making methods), and sometimes it's meant to describe eternal meta-physical (immeasurable) truth.

Consider what would happen to science and religion respectively if the laws of physics suddenly changed. We might have to throw most of our scientific models out the window and completely restart the process of scientific inquiry from the ground up, but how much religious "knowledge" would actually be affected?

P.S We can always be more earnest in our attempt to understand one another, and I'm legitimately trying harder to understand your position. I want to do more than just restate my position; I'm trying to restate it in a way that better exposes its arteries, both so that it might be easier to understand, and so that you have a better opportunity to attack them with arguments and evidence of your own. If my tentative materialist convictions really are as naive as you say, I want to know why. -

"Skeptics," Science, Spirituality and ReligionAs I indicated, behaviorism has fallen into disfavor these days.

Behaviorism is not the assertion that the mind is a fiction, it is that we can understand behavior by treating people as black-boxes with inputs and outputs. (by "black-box" I mean that behaviorists were not concerned with how the brain actually works, but were instead concerned with how the mind behaved; they never looked inside the skull). Behaviorists referring to the "mind" as a convenient fiction needs this context to make sense; he wasn't saying that thoughts don't exist, he was saying that thinking machines can be understood by deducing things about the relationships between inputs and outputs. Even in the case where Skinner was really trying to make "mind" incoherent, it doesn't matter. His controversial contention is not an established product of science (as science in general is a mix of different fields, some of which are at odds with each-other, where overtime the more explanatory and predictive models are eventually identified and selected). Looking only at behavior as a means to predict it has its uses, but it quickly gave way to more comprehensive approaches.

I was using the term "cognitive science" as it is often used, to denote the study of human behavior through the lens of new technologies such as CAT, MNR, and PET scans. When I was a psychology major in the 1970s, we called it "cognitive psychology." "Psychology" became "science" as more hard science techniques joined the team. On this forum, many posters are not willing to recognize that CS is psychology at all. — T Clark

I've lost the context of your point then. Cognitive psychology/science doesn't asserting that "minds" don't exist. There may be some scientists making claims that vaguely amount to this, but I'm lauding the established fruits of science, not the beliefs and failures of any and every proponent of science. Some scientists contradict each other, especially when they're speaking about less proven models near the cutting-edge of scientific progress.

Are you really suggesting that the brain is not the seat of the mind? That if i damage your brain I won't also damage your mind?There is no "hard problem of consciousness." But that's another discussion. — T Clark

Tell me what the hidden variable is. Where do you get the idea that "minds" come from anywhere other than nervous systems and neural networks? If I didn't know better I would say you're trying to get at "souls" or something.

Tell me how pain "reflects" electrical current running through living conductors. What does that mean? They have no traits in common that I can see. If you and I are watching basketball on TV, would you say that the television equipment is the same as the presentation of the game? — T Clark

I think you are indeed getting at the hard problem, why else would you want me to explain how subjective feeling can be produced by a physical system? Pain "reflects" what's happening in our brain because our brain has figured out that something has gone very wrong in the external world that demands immediate correction (our "intelligence" is meant to "reflect" things in the external world). We can prove this with elementary induction: every-time we injure our bodies, we feel pain, and when we consume pain-killers (which act on the mechanisms within our brain which play a role in the creation of "pain") we feel pain less.

If I surreptitiously dose you with a drug, your body and brain (and hence your mind) will react to it regardless of whether or not your mind is consciously aware that it has been drugged.

This is not a new argument. It's been around for hundreds of years. It is discussed often on the forum. For you to claim that you cannot fathom it is... well, I'm not sure what it is.

As I've said elsewhere, I think I may open another discussion on the general subject of the underlying assumptions and values of science without focusing on god. Maybe that will make it easier. — T Clark

I'm not focusing on god either though, we're talking about the merits of cognitive science. I'm saying that it approaches "minds" as if they are a thing that is produced by brains (not that "minds" are incoherent or non-existent), and you're saying that it somehow makes an empirical error by assuming that minds do not exist. (isn't the statement "minds do not exist" self refuting? A true logical "ouroboros"? (Considering cogito ergo sum and all).

It seems there is more than one tangential thread we could make. There's the values of science thread (whether or not, epistemologically, the philosophy of science is malformed), and there's also the "Is the mind the seat of the brain; do minds exist?" thread.

Let's earnestly try and eek out an agreement before we do so. Where do we disagree exactly: we differ on the nature of scientific inquiry in some meaningful way, or else we disagree about the epistemological implications of the results of our scientific inquiries; we also have an apparent disagreement about the relationship between minds and brains, and I'm hard-pressed to imagine how we must necessarily differ:

Do you remember learning about Phineas Gage? (the dude with the pipe through his frontal cortex). Do you believe that the alterations to his "mind" apparently caused by the physical damage to his brain were superficial or coincidental? We both agree that minds exist, and I point to the brain as the thing that generates it (and to changes in the brain correlating with changes in the mind as evidence), but what do you point to as the thing that generates it? Are you holding out judgement in case of some development that shows we're more than the contents of our flesh-sacks?

I don't understand where you're coming from, truly. I know that you perceive cognitive science (or science as a whole) as a profligate possibility-denier, but which possibility is it denying that you hold to be plausible (other than that minds exist in the first place, which I contend science does not deny)? -

"Skeptics," Science, Spirituality and ReligionThis is not correct. Science and scientists try to discredit the idea of the mind in a number of ways:

There is a school of psychology, behaviorism, which claims that there is no need to hypothesize the existence of a mind. We can deal scientifically with human behavior just by observing the behavior. It's not very popular these days. — T Clark

Behaviorism seeks to gain predictive power about human behavior, not to comment on the existence or non-existence of minds. It's an approach to predicting behavior based on inputs and outputs. You're mistaking the point and implications of behaviorism as some kind of definitive statement about the underlying nature of minds, but it's just the opposite.

Its mantle has been taken up to some extent these days by cognitive science. Personally, I think CS is the best thing to happen to psychology since Oedipus, but there are lots of claims that it eliminates the need to think about minds at all. — T Clark

Cognitive science is broadly "the study of minds", so you must be conceiving of "mind" as something other than the thing cognitive science seeks to study. Are you talking about the hard problem of consciousness?

Related to that, lots of scientists, and lots of people here on the forum, think that the mind is the brain. I took two philosophy courses in college in the early 1970s. One was called "The Mind-Brain Identify Problem." The idea had been around for hundreds of years before then. — T Clark

The processes of the mind reflect the processes of the brain. There's so much evidence for this that I can't fathom what you're trying to say.

It is very common for scientists to claim that psychology, the study of mind and behavior, is not a legitimate science at all. This claim has been made on the forum many times. — T Clark

If the study of mind or behavior cannot be scientific, why are you trying to say that science denies the existence of minds?

The bullshit/bologna No Overlapping Magesteria flapdoodle. — T Clark

Insisting that science is like religion isn't accurate or useful.

My belief that an external world exists should not imply that I think science is "the only important thing".This is fun. I may start a new thread so I can think of more examples. All of these are signs of the same disorder - those who think of themselves as so-called "hard" scientists and their intellectual cohort believe that the only important aspects of our world are what they call "external reality." Here's a great example: — T Clark

How and why do you make this irrational leap on my behalf? -

Is criticism of the alt-right inconsistent?I think defeatism must have been rife during the 80's, probably for more reasons than I can fathom (Born in '88 myself), but I can say with confidence it was prevalent because of how much it has come to define the "3rd/4th wave" of "feminist" ideology.

Feminism has long been intertwined with other social equality and civil rights movements (female rights advocates and abolitionists of the 1800's noticed they shared many core beliefs, and they've generally ganged together ever since), and in today's academic and political/cultural landscape, "intersectional feminism" aggressively defends its monopolistic right to have the main and final say on all things unequal. I know I bring up intersectional feminism more than I should (as if it is a bogeyman), but it's just so damn relevant because it's the ideological and academic source for contemporary identity-based politics.

In any case, the post 80's vectors of social justice are inherently defeatist in that they blame everything on a system of systems that is beyond their immediate control. It portrays a power-dynamic that cannot be worked with, and instead must be destroyed entirely (ultimately the power dynamic they've defined is based upon identity such as race, gender, or sexual orientation, so almost invariably white/male/cis/het/etc become "problematized").

This is where the simplistic and polarizing ideas and rhetoric that actually gave birth to the proto-reactionary alt-right originally came from (I.E the idea that "whiteness" or "white people" or "white culture" are "under attack"). Ideas like "white guilt" which are based on the idea that all whites have all the power are the perfect rhetorical tools for right wing pundits to appeal to the emotions of (especially) young white men by stoking fear and paranoia (it doesn't help that the online world of rhetoric can amplify absurd messages, which warps our perceptions of the political landscape and magnifies the severity of certain elements).

Once a large enough base of the emotionally vulnerable and intellectually immature had coalesced (with no coherent political worldview), it was really only a skip and a hop for many of them to turn to full blown neo-nazism. After soaking themselves in the anti-white rhetoric and paranoid delusions of a white-apocalypse, it's hard to see how none of them would be enticed by it. At the same time, as if they were dormant vampires awakened and rejuvenated by fresh youthful blood, the neo-nazi and KKK old guard came out of the wood work to enter and stoke the evolving alt-right movement (which exists almost entirely in social media formats that mainstream reporting is not equipped to report on or compete with).

What's the answer to white guilt? "White pride", they said. "If it's O.K for other groups to celebrate their heritage and be proud of who they are, and to seek to preserve their culture, why not us whites? What if they hate you because you're white?

And that's how a faction of the alt-right became a tribalistic white supremacist movement that is out of touch with reality. It took a counterpart; a dance partner to mirror. Intersectional feminism is tribalistic in every way, and it directly controverts the main thrust that made MLK so effective (peace, love and unity). In the same way that the alt right is tribalistic, so too are many over-blown "justice" movements that claim to champion a different shade. Being tribalistic poses a danger to modern society of a certain magnitude, but tribalism that is also largely divorced from reality is another magnitude of danger entirely. Alt-right lunatics with their deeply held delusions and irrational fears (e.g: white people will soon cease to exist) are especially dangerous.

"The sky is falling, there's nothing we can do about it alone, and they are to blame".

It's the exact same dull argument from all sides, and it's maddening.

P.S Sorry to suddenly lay this tangent on you; I've been trying to make a post in this thread and it turns out you're my safe space! <3

VagabondSpectre

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum