Comments

-

Ukraine CrisisDude, you are debating someone who believes that nations have a natural right to conquer and subjugate other nations based on their ethnic origin. I don't know why this neo-Nazi scum hasn't been banned yet. At least don't legitimize him.

-

Ukraine CrisisJanuary 2021

Russia: OMG! We suddenly realized that NATO has been expanding in Europe since 1997! And Ukraine might some day join NATO too! This is an existential threat! NATO must pull back right now!

Putinverstehers: See what you've done, NATO? Putin feels threatened!

February 2021

Russia: That's it! We can't wait any longer! We have to attack Ukraine right now, before it might some day join NATO and attack us!

Putinverstehers: See what you've done, NATO? Russia's war on Ukraine is totally your fault! You left Russia no choice!

May 2022

Finland & Sweden: We are going to joining NATO now.

NATO: Welcome, Finland & Sweden!

Russia: It's cool, we are not worried. -

Ukraine CrisisRussia is still sore about the sinking of their Black Sea flagship and attacks on patrol boats near Snake Island. How else to explain this delirious disinformation campaign on Twitter? But who are these English-language posts aimed at? (Although, given that some posters here have been quite willing to give credence to the most ridiculous Russian propaganda, simply because it validated their favorite narratives, perhaps this isn't as stupid as it looks.)

-

Ukraine CrisisPutin has publicly demonstrated many times that he basically does not understand what a discussion is. Especially a political one – according to Putin, a discussion of the inferior and the superior shouldn’t take place. And if the subordinate allows it, then he is an enemy. Putin behaves in this way not deliberately, not because he is a tyrant and despot ad natum – he was simply brought up in ways that the KGB drilled in him, and he considers this system ideal, which he has publicly stated more than once. And therefore, as soon as someone disagrees with him, Putin categorically demands "to stop the hysteria." (Hence he refuses to participate in pre-election debates, which are not in his nature, he is not capable of them, he does not know how to make a dialog. He is an exclusive monologist. According to the military model the subordinate must keep silent. A superior talks, but in the mode of a monologue, and then all the inferiors are obliged to pretend that they agree. A sort of ideological hazing, sometimes turning into physical destruction and elimination as it happened to Khodorkovsky). — Anna

This has the ring of truth. And if it is true, there is nothing to be done short of complete military defeat at any cost. It certainly makes more sense than the cries of delusion, stupidity, and pathology that are projected rather too easily in his general direction. — unenlightened

A striking illustration of how Putin talks to his underlings was this bizarre televised spectacle of his Security Council meeting right before the war, in which he sat them all down in front of him like children, in a semicircle, and had them publicly pledge their allegiance and complicity to the course, while scolding and humiliating those who went off script.

link -

Ukraine CrisisYou have a knack for picking the worst foils for your contributions (I mean, Apollodorus? Really?)

-

Ukraine CrisisRussian anti-war protestors brave police repressions, sometimes resorting to subtle subversion in an attempt to avoid being arrested.

"Мир! Труд! Май!" (Peace! Labor! May!) used to be a common slogan at Soviet May 1 demonstrations. Here is an updated version at a government-sponsored demonstration today, featuring the omnipresent "Z"wastica:

In contrast, this lone picketer is holding up a sign on which the word Peace is conspicuously absent. (When passersby asked her why there was no "peace", she told them that she could ask them the same question.)

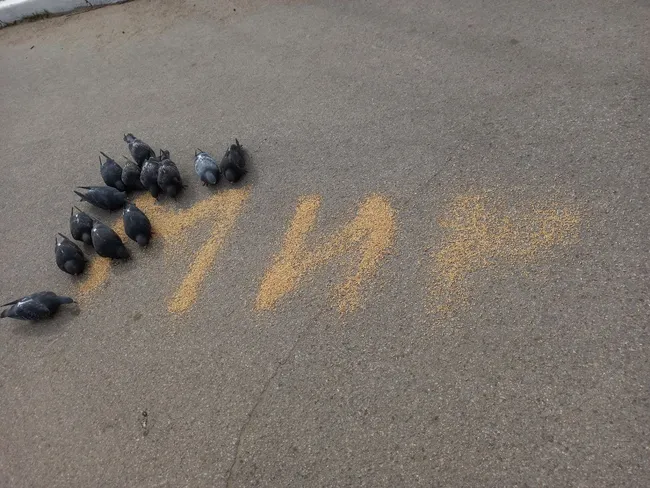

I like this one best (the disappearing letters spell PEACE in millet):

-

Ukraine CrisisSo this rubles-for-gas confrontation that Russia got itself into is pretty bizarre. To be clear, there is zero economic sense in it for Russia - it's pure political posturing. Although Europe says that agreeing to pay for Russian gas in rubles would violate European sanctions against Russia's Central Bank (not to mention that it would violate existing energy contracts), it's not like getting their payment in rubles would somehow cushion the blow from financial sanctions for Russia.

Lately, Russian Central Bank requires all Russian companies to convert 80% of their foreign currency revenue into rubles, whether they need them or not. Gazprom is no exception. And if the government wanted Gazprom to convert all of its European revenue into rubles, it could just order it to do that. The end result would be the same as if its customers were paying it in rubles, except that there wouldn't be all this brouhaha. -

Ukraine CrisisRecently news media and analysts have been discussing a reported comment made by some Russian general about Russia's goals in the next phase of the war, which, according to him, consist of taking Donbas and southern Ukraine all the way to Transnistria (a Russian-controlled breakaway border region of Moldova). While many took this to be the new official direction, it's not at all clear whose position this general was expressing and why. Gen. Minnekaev serves in a large military district, but he does not participate in the "special operation," his position has nothing to do with military planning, and he does not commonly give public statements. He made his apparently unsolicited comment at a meeting with local business representatives. Was he just sharing his personal opinion of what Russia should be doing?

These veteran investigators of Russian security services think so. In a recent article on a Russian-language site Andrei Soldatov and Irina Borogan report on the prevailing attitudes among their contacts in the FSB (the successor of the KGB) and the army. It seems that officers are not happy with the direction the war has taken, and they even criticize Putin himself (in private, mostly). But they don't oppose the war - on the contrary, they want more of it. They are disappointed that the initial push to take Kiev was abandoned. One widely shared video recorded by a veteran special forces officer with a popular Youtube channel urges Putin to wage a total war with airstrikes targeting all of Ukraine's infrastructure. "Dear Vladimir Vladimirovich, please make up your mind: are we fighting a war or jerking off?" -

Ukraine CrisisUkraine has long running issues with extreme corruption and powerful oligarchs holding back any reform, as well as radical ideologies infecting the nation's politics. — Count Timothy von Icarus

That's the one issue Ukraine doesn't have (ironically, given the context). Since the Maidan Revolution in 2014, radicals have signally failed to make any political gains. On the contrary, as @ssu has been pointing out, they have been progressively losing what little hold they had in Ukrainian politics.

In 2014, in the wake of regime change, annexation of Crimea and Russian invasion in Donbass, when one might have expected nationalist sentiments to be running high, the two ultra-nationalist candidates collectively claimed less than 2% of the presidential vote, and none of the far-right parties were able to clear the 5% barrier in the parliamentary elections (although a few of their members won majoritarian seats). Radicals have been losing popular support ever since. The Right Sector - one of the main boogeymen of Russian propaganda - is all but extinct. Svoboda - the largest nationalist party in Ukraine - again failed to make it into the parliament in 2019, winning even fewer votes than in 2014. There is a plethora of far-right movements in Ukraine, but they have virtually no political power. -

Ukraine CrisisYes, and then there are useful idiots who are idiots enough to actually buy into the propaganda. I should have made that clear.

-

Ukraine CrisisOr:

C. Able to distinguish nuance. Maybe it isn't about a specific number of Nazis, but what they are doing. Are they massacuring civilians and gearing up to invade their neighbors the way the real Nazis did? Do they actually have the capacity to do these things or is there an immanent risk of them gaining those capabilities? How will said Nazis be eliminated and what collateral damage will occur during these efforts? What tools are available for dispatching the Nazis: a modern, professional military with guided munitions for avoiding collateral damage, or one that is going to begin punitively shelling residential neighborhoods when they meet resistance and which will start gang raping women and children? Are there ways to engage the Nazi threat with more limited means? — Count Timothy von Icarus

Or D: Refuse to take the bait. Seriously discussing whether or not there were enough Nazis in Ukraine to justify an invasion, or even considering it a topic worthy of discussion serves to enable Kremlin's fake narrative. For the useful idiots to do their job, they don't even need to buy into the narrative completely - they just need to take it seriously and keep it in the public consciousness. This creates the general impression that there is such a thing as "Ukraine's Nazi problem." -

Ukraine CrisisIf you are in Russia, you can no longer watch this classic Soviet cartoon on Youtube (although Youtube hasn't been banned yet):

Kids explore the seas in a submersible named "Neptune" (sporting yellow and blue colors!) in search of sunken treasure. Instead they find a sunken Nazi warship with a letter Z inscribed on its side.

Basically Russian history tells us how we got here. — ssu

Come, ssu, get with the program. Who cares about Russian history? History matters only when it revolves around the US. Everything revolves around the US. America is so powerful that it dwarfs all other causal factors, in all matters, everywhere.

Enough about Russia and Ukraine already. This thread, like every thread having to do with politics and current events, is about America. -

Ukraine Crisis

-

Ukraine CrisisWorth remembering that Russia was indeed led to believe that NATO wouldn't advance beyond 1990 borders. — Xtrix

You aren't bringing up anything new. The NATO thing has been done to death... -

Ukraine CrisisCould be the real story. Could be made up to show that the Ukrainian made Neptune works deter future amphibious assaults. They did just get Harpoon missiles from the UK, although those are fairly antiquated, so the Neptune might be more likely. — Count Timothy von Icarus

There is a sort of indirect acknowledgement of the missile attack version from Russia in the fact that they struck a factory near Kiev that produced Neptune missiles the following night.

I agree that the mass executions of civilians, rapes, and looting reported don't seem organized. It's more indicative of terrible discipline, maybe ethnically motivated in the case of some units, but that's impossible to say. — Count Timothy von Icarus

We don't have much to go on at this point, but there are consistent patterns emerging from witness testimonies. One common theme in many stories of those who lived under Russian occupation, passed through Russian checkpoints, or were deported into Russia is the search for "Nazis" and "nationalists." Soldiers or security officers are searching documents and phones for anything they might deem incriminating. They are also looking for nationalist or patriotic tattoos. Those who arouse their suspicions are often the ones who are imprisoned, tortured or killed.

One woman, who spent a few weeks in an occupied village with her family, told about their occasional conversations with the Russian soldiers who lodged in their house (while forcing the family with two small children to stay in a cramped cellar). They said, apparently in reference to the locals, that they had orders to shoot to kill. They also said that they would shoot at any moving car after one warning shot, and there was plenty of evidence that they did just that. -

Ukraine CrisisRussian military are making thousands of job postings on sites like HeadHunter and Superjob: https://hh.ru/vacancies/voennosluzhaschij-po-kontraktu

This isn't a new phenomenon as such, but in the past such postings were mostly for civil specialists like bookkeeper. Now it's mostly combat specialties. And there are a lot more of them all of a sudden. Posted salaries for these essentially mercenary contracts are pretty modest even by Russia's standards, although real pay would be much higher for a combat deployment.

In one city you can even find ads for a short-term military contract in the local subway:

What a contrast with this!

-

Ukraine CrisisWhat Russia is doing is still awful and criminal, they shouldn't have done it, the punch is coming back with interest added. But from a "realpolitik" perspective, it makes sense. — Manuel

So as you admit, the invasion hurts Russia big time. And it will continue to hurt for many years to come. In addition to the human cost (both from war casualties and from the massively accelerated brain drain), its economic, scientific and technological development will be thrown back by decades. Its foreign relations are in shambles. Its security situation, even from the paranoid Kremlin point of view, will be worse than it was before, with NATO strengthened, expanded and on full alert.

Then in what fantasy world does it "make sense"? Just saying "realpolitik" over and and over, like a magic incantation, won't cut it. -

Ukraine CrisisThe primary assault was done on the assumption that Ukrainians wouldn't fight, that it would be somehow a repeat of 2014. Now that's out of the question. And the total withdrawal from the Kyiv area shows that Putin understands that it didn't work. — ssu

Word is that many of the FSB officers from the 5th Division, the office responsible for Ukraine intelligence, have been fired and may be facing prosecution. If true, this would likely be the biggest purge in the security services since Stalin. The head of the office has been charged with embezzlement and premeditated disinformation. On some level this is encouraging: at least this shows that Putin is aware that he was massively misinformed before the invasion. -

Ukraine CrisisYeah, I saw the reports as well. It's unconfirmed at this point. We don't know whether the Russian army even has chemical munitions in its arsenal (poisons that security services have been using for assassinations are a different thing).

It's hard to imagine that the atrocities that the Russians are already committing could be made worse, but I fear that chemical weapons could take them to a new level. Remember the bombing of a theatre in Mariupol where hundreds of women and children were taking shelter? Many died, but many who were hiding in the basement survived and were able to get out. If instead of, or in addition to conventional explosives the theater was hit with chlorine or Sarin, there would be fewer survivors. As we have seen in Syria, these heavier than air gases are terrifyingly efficient at killing large numbers of civilians sheltering underground in cities. -

Ukraine CrisisNotably though, Russia kept its official conscription figures fairly normal, which was a good sign for peace, but now apparently they are doing behind the scenes conscription, including on the spot conscription at road blocks. — Count Timothy von Icarus

In the separatist "republics" they have been forcibly conscripting all military-age males right from the start of the invasion. Many men there are in hiding, afraid to go outside even to buy food. Recruitment patrols grab anyone they can find and take them straight to the barracks. I haven't heard about such things in Russia proper though. -

Ukraine CrisisWell. Maybe. But they surely must have heard that NATO will intervene if they use chemical weapons, or at least, this is what they've stated. — Manuel

Nah, NATO will not intervene over an alleged use of chemical weapons (which Russia will, of course, deny or blame on Ukrainians themselves). They've been careful this time about not setting any red lines. Even Biden, loose cannon that he is, has consistently been saying that US would not intervene under any circumstances whatsoever. "Dire consequences" is as far as anyone would commit, which would likely amount to nothing more dire than a nonbinding UN resolution. -

Ukraine CrisisWMD news:

- Eduard Basurin, press secretary of the DNR (the self-proclaimed Donetsk Republic) military command, said that "chemical troops" will need to be deployed in order to "smoke out" Mariupol defenders.

- Ramsan Kadyrov, the Chechen strongman, said in his latest video that tactical nukes should be dropped on Kiev and Kharkov if Ukraine does not surrender.

Kadyrov's troops have been taking part in the siege of Mariupol (or so he claims), and for the last several weeks he has been regularly posting videos announcing an imminent fall of Mariupol. There's no reason to take him seriously in this case either. In Russia he is allowed to say and do pretty much anything he wants, and his security forces have also been involved in assassinations abroad. But he has no say over the use of nukes, or for that matter over the general conduct of the war.

But DNR stooge's casual reference to "chemical troops" should be taken seriously. I can see Russia using chem weapons via its proxy forces, which would give it a modicum of plausible deniability. -

Ukraine CrisisThe second time I checked, it was behind a paywall, so I just wanted to spare you the hassle. — neomac

Ah I see, for some reason I was able to see it - perhaps because I use NoScript. -

Ukraine CrisisYou know we can just follow the link, right? You don't need to copy-paste the entire thing here.

Yes, this looks like a typical presentation of the official stance, geared more towards the foreign reader.

If you want to see something even more candid and unrestrained, read this article that was published about a week ago by the Russian state news agency RIA: What Russia Should Do with Ukraine (offsite English translation). It is a true fascist manifesto. -

Ukraine CrisisCrimea never would've become a part of Russia if the US hadn't been meddling in the internal affairs of Ukraine for decades already. — BenkeiHypotheticals are difficult as you yourself implied, but simply use your head here, Benkei. I know you have one. — ssu

I've been wondering about this phenomenon: Benkei, etc. are not even Americans, and yet they are as parochial as Americans are often said to be. Parochial about someone else's country! How pathetic is that? In their closed minds nothing exists, save for or because of the United States. Nothing else is worth talking about. Ukraine? Russia? Who the fuck cares! The US (and, of course, NATO and capitalism) is what this is all about. Or at least all that they can think about.

Then I realized what this reminded me of: antisemitism and other such obsessive bigotries and conspiracy theories. Now at least it makes some sort of psychological sense. Those Jews (Masons, gays, Americans) are the root of all evil. They openly and secretly manipulate events for the purposes of world domination or apocalyptic destruction. -

Ukraine CrisisI'm wondering if the harsh sanctions may have been a mistake. If it just closes Russia off to the rest of the world, that's unfortunate. — frank

They are. No doubt about it to my mind. Perhaps isolate sanctions to oligarchs and Putin, try to make these bite, other sanctions only hurt the population. — Manuel

In the past, Western sanctions against Russia attempted to spare the majority of the population by targeting mostly individuals and selected military-industrial entities. That didn't seem to have any effect. Now sanctions are explicitly aimed at the entire nation. Such total sanctions are really a war by other means, and just like in the conventional hot war, the entire nation suffers. The thinking behind such sanctions is that, even if they don't directly motivate the rulers, they may build up pressure from below. (What they don't take into account is that public discontent is more likely to be directed at those who impose the sanctions, as seems to be happening in Russia.) At a minimum, they will degrade the country's ability to make trouble abroad - but that can only happen in the long run. Sanctions won't stop an ongoing war.

Do sanctions generally work? That's a tough question. Studies of past sanctions claim to show that sanctions have achieved some objectives in a minority of cases, but also that they were more likely to succeed when objectives were modest, such as changing some trade policies. But discerning the impact of sanctions on decision making can be difficult. If Putin did not order the invasion, would that be credited to the threat of sanctions? Not likely, given that most people did not expect a large-scale invasion to happen anyway (despite warnings from Western intelligence). In Putin's case they would probably be right though: he cares little about such things.

In deciding to impose sanctions, there is a significant factor of moral outrage and moral signalling, perhaps more significant than any pragmatic calculations. We want to punish the bastards. The latest escalation of sanctioning activity is a good illustration of that point, as it followed on the heels of gruesome imagery coming from journalists who got direct access to freed areas around Kiev. Images of a dozen dead civilians lying in the street produced a stronger reaction than credible reports of hundreds of people dying from indirect fire in Mariupol and elsewhere. Let alone the estimated 95% of Afghan population that are not getting enough to eat, partly as a result of Western governments' action or inaction. -

Ukraine CrisisI don't think all roads save one were cut off. And I think the trains have been moving also. — ssu

Evacuation trains have been leaving Kiev every day since at least early March. But never mind facts, let's listen to some bullshitter obsessed with proving a point :roll: -

Ukraine CrisisThey're depressingly subservient. It seems they have totally bought into the fact that Putin is an absolute ruler. — Wayfarer

Well, you have to assume that there is a negative selection at work here: how else could these people climb up the power hierarchy and stay there? There are no heroes among them, to be sure. (Although a few at least jumped ship, but that's not an option for everyone.) -

Ukraine Crisis

Speaking of consolidating power, these two articles by the Russian journalist Farida Rustamova are interesting. She has talked to her contacts among the Russian power elite about the war, first in the first week after the invasion ("They’re carefully enunciating the word clusterf*ck"), and then again weeks later (“Now we're going to f*ck them all.”).

(Given that most of her sources are anonymous and there is little independent confirmation for any of this, you can only trust her integrity. But she has written for respected media outlets before independent media was completely shut down in Russia.)

What she describes in the first article is that apparently, the full-scale invasion was a complete surprise to all, and the first reaction to it was shock, incomprehension and fear. But then the mood changes. There is the expected rally-around-the-flag effect, as well as a realization that, like it or not, this is a new reality to which they will have to adapt.

Over the past week, I’ve spoken with several people close to Putin, as well as with about a dozen civil servants of various levels and state company employees. I had two goals. First of all, to understand the mood among the Russian elites and people close to them after the imposition of unprecedented sanctions on Russia. Secondly, to find out whether anyone is trying to convince President Putin to stop the bloodshed — and why Roman Abramovich ended up playing the role of mediator/diplomat.

In short, it can be said that, over the past month, Putin’s dream of a consolidation among the Russian elite has come true. These people understand that their lives are now tied only to Russia, and that that’s where they’ll need to build them. The differences and the influence of various circles and clans have been erased by the fact that, for the most part, people have lost their past positions and resources. The possible conclusion of a peace treaty is unlikely to change the mood of the Russian elites. "We’ve passed the point of no return,” says a source close to the Kremlin. “Everyone understands that there will be peace, but that this peace won't return the life we had before.” — Farida Rustamova -

Ukraine CrisisI am sorry I started this. You have shown that are quite capable of holding both sides of this imaginary argument that you are having with yourself, so you don't need me here. I'll continue to ignore you as I did before.

-

Ukraine Crisisbut to argue they haven't achieved anything militarily and the Ukrainians have in some way "won" just doesn't make any sense. — boethius

You are projecting. I never asserted anything of the sort.

Russia has invaded Ukraine, it is fighting a war entirely on Ukrainian soil and holding some Ukrainian territory (which it wasn't already holding before the war). That is a military achievement, in a narrow sense. (What, in the long run, Russia is to gain from all this is another question.) But why, in arguing this obvious point (against whom?), do you find it necessary to give ridiculous rationalizations even for the campaign's obvious failings? Do you think this somehow makes your argument stronger? -

Ukraine CrisisYes, I know you've dumped a lot of bullshit commentary in this thread. I stopped paying attention a long time ago - I just chanced on that delusional passage because it was quoted by someone else.

Sure, the evident military setbacks and losses are really all part of a cunning plan... I understand when it's Russian generals saying this - because what else could they say? - but it still boggles me why someone apparently disinterested would use such desperate arguments just to shore up his positions in a debate. -

Ukraine CrisisOn an unrelated note, the new narrative is hilarious. All the stalling out and counter attacks are actually part of a grand strategy.

— Count Timothy von Icarus

Oh and here of course is a useful idiot echoing the generals' line with his trenchant "analysis":

It's not "convoluted" to point out they achieved those core goals ... which manoeuvres elsewhere in the country, in particular pressure on the capital, help achieve by spreading forces and supply lines thin (and making it easier to map and blowup said supply lines). — boethius -

Ukraine CrisisYeah, losing face is probably the biggest problem now. They can't go home humiliated, or to state it another way, they will not. — Manuel

They will declare a glorious victory regardless of what happens. Remember, as far as Russian authorities are concerned, Russia did not even go to war with Ukraine. Russia is conducting a "special military operation," which is proceeding strictly according to the plan (whatever that plan may be). Anyone saying otherwise will be persecuted.

A large segment of Russian population is living in a world that has very little to do with reality. They believe what they are told on TV. Even people whose close relatives are right now dodging Russian bombs in besieged cities refuse to believe them. Others don't dare show their dissent. Those who do are arrested, fined, jailed, fired from their jobs, pressured to leave the country.

When you can flat-out deny or assert anything and get away with it, why should you be concerned with reality?

"How many fingers am I holding up, Winston?"

There are also reports - which again, taken with lots of salt - which say that Russia expected this thing to last about 2 weeks. Now, this may all be fake. — Manuel

This article was published on Russian state news agency RIA just days after the war started, then quickly pulled down. (The original can still be found on wayback machine and on Sputnik news site, and an English translation was published on a Pakistani site at about the same time.) Apparently, the article was prepared in anticipation of a quick conclusion of the "special operation" and distributed to friendly news organizations in advance. It is a delirious and nauseating celebration of Russian takeover in Ukraine that includes passages like this:

Returning Ukraine, that is, turning it back to Russia, would be more and more difficult with every decade – recoding*, de-Rus-sification of Russians and inciting Ukrainian Little Russians against Russians would gain momentum. Now this problem is gone – Ukraine has returned to Russia.

(My emphasis)

* The translation is rather poor. "Recoding" here means "brainwashing." -

Ukraine CrisisWell, that was unresponsive. Seems like all you got from my post was that I am a "propaganda denier." Fine, carry on.

-

Ukraine CrisisYes, they do propaganda and we do propaganda too. — Baden

start babbling about any other bad thing — Baden

Funny how that works, isn't it?

So, you keep asking, what about our propaganda ("our" being the collective West, I assume). Well, unlike a lot of other whataboutism in this thread, this is somewhat relevant to the topic. So, what about it?

I assume that people have some idea of what propaganda is like in Russia. Without getting into details, the most important thing about Russian propaganda is that it dominates public discourse inside the country (and is surprisingly influential outside, but let's put that to the side). It is univocal, institutionalized and pervasive. There is no public accountability for truth. Dissenting voices are suppressed.

When you say that "we do propaganda too," do you see something similar in the West? I would assume not. (And please, let's not debase ourselves with hysterical exaggerations and silly conspiracy theories when arguing the point.) So in what way is Western propaganda similar to Russian propaganda? What would you even qualify as propaganda?

There is government discourse: statements, speeches, press releases, etc. There is discourse originating from from various political, business, activist interests. There are influential media. But taken collectively, they are far from univocal, and individually, none of them have the power to dominate the public discourse. -

Ukraine CrisisYeah, looking back over the past year, it almost looks like the authorities knew all along that all that tosh about human rights and freedoms would soon become irrelevant. With everything else that's going on, there's no more need for even halfhearted pretenses.

As soon as Russia was kicked out of the Council of Europe ("you can't fire me - I quit!") Dmitry Medvedev (who many thought to be softer and more liberal than Putin) gleefully declared that now Russia was finally free to reinstitute capital punishment.

I don't know who you are jumping up and down for, but if it's on my account, then don't bother. Go back to bickering with whoever cares. -

Ukraine CrisisOn an unrelated note, the new narrative is hilarious. All the stalling out and counter attacks are actually part of a grand strategy.

— Count Timothy von Icarus

Some, uh, experts seem to go along with this narrative:

On a related note, I think that some of the commenters (and I don't entirely absolve myself) tend to hold official Russian rhetoric to a standard of truthfulness, rationality and consistency to which it does not hold itself. For example, some say that after repeatedly and forcefully stating their objectives in this war, the Russian side cannot afford to back down and leave with much less - something that they could have achieved sooner and easier, with far fewer losses. Most of all, because that would threaten its standing at home. This analysis does not appreciate just how little bearing facts and common sense have on what Russian officials and propagandists are saying, and how abruptly they can switch their talking points. (How much any of this matters to the Russian populace is a different and more complicated question.)

For people on the outside, the depth of denial, absurdity and cynicism in the official rhetoric may be difficult to fathom, but here is just one example. One of the principle justifications for the war (which cannot be called a war) was and remains the "genocide" of the Russian people in the separatist Donbass. Apparently, the public is more receptive to this narrative than to others, and so propagandists put it front and center (for example, when talking about the not-war to schoolchildren). But contrary to what one might expect, this narrative was almost entirely absent from the public sphere until about two weeks before the invasion, when suddenly it was being blasted out of every TV set. Neither actual numbers nor the record of news stories and official statements over the past several years bear it out. And yet it appears that this jarring switch went unnoticed by many. In true Orwellian fashion, a sizable number of people (according to some surveys) now believe that a genocide has been ongoing all these years.

I am not going to make any predictions, but my point in all this is that there are more live possibilities here than some prognosticators admit. It is entirely possible that at the end (if there is an end) the Russians will declare that their goal was always whatever it is that they will have decided to settle on, and that will be it. The record showing otherwise won't matter in the slightest. -

Ukraine CrisisMy understanding from what I've read is that Putin won't agree to a ceasefire until he's negotiating from a position of strength, which he hasn't yet achieved. One metric for achieving that would be to cut the Ukranian forces off from the sea. Another, would be to take some of the major cities. If that is true and the Ukranians are provided with more weapons and encouraged not to back down to Russian demands where does that leave us?

It seems to me the worst case scenario for Ukraine is a continued war of attrition that they're not losing quickly but can't win either and lose slowly until Putin achieves his military position of strength. And so they continue fighting while their cities are reduced to rubble; their citizens lose access to food, water and electricity; civilian casualties mount; and the cost of reconstruction both in terms of time and money skyrockets. And seeing as NATO has explicitly ruled out intervening militarily, which of the following do you think is the more likely outcome? — Baden

I don't see Ukrainians needing encouragement or persuasion - they are the ones doing all the persuading. And they are the ones doing all the fighting. So it is not for you to decide what is best for them, as if they were children who can't make responsible decisions about their own well-being. If they ask for help, you either give it to them or fuck off.

SophistiCat

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum