Comments

-

What evidence of an afterlife would satisfy most skeptics?None. The question is metaphysical and therefore doesn't really concern evidence, for any answer to the scientific question "is there an after-life" whether "yes", "no", "maybe" or "mu" (meaning the question is nonsense) is tautologically decided.

For the scientific question to make sense, the concepts of "Persons", "lives" and "After-lives" must first be given definitions in terms of physically contingent types and/or natural kinds. At which point scientific evidence becomes relevant in so far as deciding whether a given "person" is now in the "after-life" state relative to the assumed ontology, which begs the entire metaphysical question. -

Can the universe be infinite towards the past?I'll plead ignorance about this point, I don't know enough physics to comment on that.

But I guess my point is that the notion of “cause” may not be applicable to the total, as Russell pointed out in his famous debate with Copleston.

If we see the universe as a “set” or “collection/bundle of events”, then there may be no sense in asking what its cause is, just as there is no sense in asking what the cause of “the set of all ideas” is, in the same sense as we would ask what the cause of a rock, or of lightning, is.

But then again, Russell did also say that matter could also be seen as a way of grouping events into bundles, so maybe there is a sense in asking for the cause of sets after all. — Amalac

Right. As you point out, a notion of causality cannot play a role with respect to any data-set that is regarded as complete and self-contained. This creates a conflict within realism, for realists tend to simultaneously assert i) the transcendental reality of causality, ii) the transcendental existence of a completed universe whether finite or actually infinite, and iii) that counterfactual propositions have a definite truth value independent of actual measurements and observations.

By contrast, if the reality of an inter-subjectively complete universe is denied, then causality can not only retain it's useful meaning as referring to the potential outcomes of an intervention relative to an agent's perspective, but also it's ontological status to a limited extent, albeit not necessarily as a linear ordering of events from "past" to "future". Bayesian networks come to mind here. -

Can the universe be infinite towards the past?

By asymmetric causality, I am referring to either the belief or definition of causality such that causes come before their effects. This is a physically problematic assumption due to the fact that the microphysical laws are temporally symmetric.

mean, the past is either finite or it's infinite, right? What is meant by “potentially infinite” then? — Amalac

The realist interpretation of potential infinity is that it is epistemic ignorance of the value of a bounded variable. For the realist an unobserved variable has a definite value irrespective of it's measurement or observation . Hence for the realist, the value of a variable is either actually infinite or it is finite, with no third alternative.

Likewise, the constructive interpretation of potential infinity also refers to a bounded variable whose value if measured, is necessarily finite. The difference is, it doesn't assert the existence of any value until as and when the value is constructed. In computer programming terms, a potentially infinite natural number in this sense refers to a natural number variable that is lazily evaluated . Only upon evaluation, does the variable possess a definite (and finite) value.

The logic of a potentially infinite past in this constructive sense is superficially demonstrated in the video games genre known as "roguelikes", where a player assumes the role of an adventurer who explores a randomly generated dungeon that is generated on the fly in response to the player's actions.

The existence of the games are effectively a demonstration of the coherence of retro-causation that is conditioned upon the players present choices. Of course, a realist will be quick to point out that the implementation of such games demonstrates nothing of the sort, being as it is an ordered sequence of instructions with a beginning and end. The deficiency of the realist interpretation of the game must therefore be argued by other means, such as by the Quantum Mechanical refutation of local causation + counterfactual definiteness + no conspiracy.

In the current context regarding the truth of past-contingent propositions , a constructive interpretation of history is that a past cause of an event does not exist over and above the construction of presently existing historical information. For example, if the present state of the universe is compatible with Jack the Ripper having any number of historical identities, then according to historical constructivism Jack the Ripper did not exist and does not exist until as and when his/her identity is constructable from historical information. And because historical evidence is rarely conclusive, the constructivist is forced to reject the assignment of a definite truth value to most, if not all, past-contingent propositions. -

Can the universe be infinite towards the past?The idea of an actually infinite past in the extensional sense of actual infinity is incompatible with the beloved premise of asymmetric causality running from past to future. In order to accept the premise of an actually infinite past, one must both theoretically reverse the direction of causality and somehow square that against physics and intuition, and in addition posit a finite future - a situation that is at least as problematic as the original picture. Or else one must entirely reject the notion of causality altogether - with the presumable consequence that having abandoned the doctrine of causality one must accept that one can no longer construct a theoretical or experimental argument for or against one's position.

In physics , the notion of actual temporal infinity is metaphysical in the literal sense of meta-physics, i.e it is a proposition that cannot be falsified, verified or even weakly evaluated through experiments.

However, there cannot be any empirical evidence on the basis of the observable universe to posit a past of any particular length. Therefore, the idea of a potentially infinite past is both perfectly consistent and the least assuming position to adopt. This position is adopted by presentists, who view the past and future as logical constructs that are reducible to sense-data. It's also compatible with quantum mechanics, due to the fact that QM has perpsectivalist retrocausal interpretations. -

Universal Basic Income - UBIAccording to Oxfam in 2020, the world’s 2,153 billionaires have more wealth than 4.6 billion people, i.e. 60 percent of the world's population.

According to Statista, the wealth of US billionnaires grew by a trillion dollars since the start of the pandemic.

According to inequality.org, "US Billionaire wealth is twice the amount of wealth held by the bottom 50 percent of US households combined, roughly 160 million people."

According to americansfortaxfairness.org, "From 2010 to March 2020, more U.S. billionaires derived their wealth from finance and investments than any other industry. The financial sector boasted 104 billionaires in 2010 -- ten years later the number had grown to 160."

UBI amounts to a forced redistribution of capital from this tiny minority to everyone else. Correct me if i'm wrong, but I suspect that there aren't any billionnaires participating in this forum thread, so I am somewhat confused by the personal anxieties in this thread concerning the idea of UBI. -

Universal Basic Income - UBIAs a global redistribution of capital from the haves to the have-nots, UBI is also a form of collective bargaining that reduces the incentive for people to work in the non-desirable jobs, thereby putting upward pressure on the wages of those jobs. It should also encourage the elimination of bullshit jobs that don't need to exist in the first place, as well as hastening the robot revolution in order to completely eliminate the undesirable jobs whose cost of labour is increasing.

-

Do human beings possess free will?hmm, would you reject the cosmological argument for the existence of God? As the main principles use causality as a means to prove His existence — Charlotte Thomas-Rowe

For me, a causal proposition is merely a synthetic proposition used to describe an intervention, that has the form "If an action A is performed upon a system in state S then the system possibly produces state R" .

Since my view of causality is anti-realist , game-theoretic and possibilistic, I suppose that my view is closest to the Occasionalists, at least as I understand them when squinting in an attempt to see past their surface-level dualism. -

Do philosophers really think that ppl are able to change their BELIEFS at will? What is your view?Do false beliefs really exist?

For example:

If the Earth is in fact round, then the assertion "The Earth is Flat" cannot be referring to the non-existent fact that the Earth is flat. And so at most "The Earth is Flat" refers to the possibility that the Earth is flat. But how can beliefs refer to possibilities?

If it is possible that the Earth is flat, then presumably the Flat Earther is referring to this possibility, in which case his assertion cannot be judged as false. On the other hand, if it isn't even possible that the Earth is Flat, then the Flat Earther can only be referring to other facts of his life, such as his present mental-state. In which case his assertion still isn't false when understood. -

A Question about ConsciousnessThat is, must consciousness always only occur, or exist, in a first person, present tense mode? — charles ferraro

That position has the advantage of deflating away the "hard problem", for consciousness becomes merely a synonym for present and actual objects. -

Philosophical justification for reincarnation

I think the central question concerns the elasticity of the rope. For liberally minded persons who only believe in "death by definition", the rope is infinitely elastic. For conservatively minded persons however, the rope is very taut. -

Philosophical justification for reincarnationYou, not we. There's nothing in the list of things that constitute the self that continues past death — Banno

What is the ontological justification for us treating an individual as being the same person throughout the course of single lifespan? -

Philosophical justification for reincarnation

-

Philosophical justification for reincarnationThe "I" is memory, body, intent, narrative...

None of which survive death. — Banno

But are these things even persistent during the course of a single lifespan?

I cannot for instance remember my childhood before the age of 5. So does this childhood belong to somebody other than I? -

Can it be that some physicists believe in the actual infinite?Category theory is a popular mathematical area. An offshoot of algebra, it can be used as an alternative to establish the foundations of math. It searches for so-called universal properties in various categories. Personally, I find it alien and entirely non-productive in the nitty gritty stuff I study in complex variables.

The Wikipedia page for Category theory gets 575 views/day, a respectable number. The page you linked gets 5 views/day and is classified as low priority (like my math page). So it may not help. But good try. — jgill

I'm unsurprised that you dislike CT. Abandoning elements feels a bit like abandoning nouns in ordinary language. It isn't a coincidence that the Turing Machine has been the predominant model of computing over the Lambda calculus - the modular conceptualisation of systems in terms of reusable and independently existing entities or elements is cognitively and practically expedient relative to the holistic structuralism of type theory/CT, albeit at the mere cost of potential philosophical confusion.

Although in the case of comp-sci, the practical expedience has recently moved towards CT due the shift to multi-core parallel programming, where control flows can be containerized, layered and equalized in a logically concise fashion using Monads. I also suspect that some generalisation of CT will become important to AI and machine learning over the next few years, due to it's notational emphasis on processes and interaction.

If nothing else, CT serves as an elitist language for getting ahead in the programming jobs market. -

Philosophical justification for reincarnationYou point is obscure. The caterpillar becomes a butterfly. — Banno

So by analogy, is personal identity over time an illusion? How should persons being counted? -

Philosophical justification for reincarnationI baulk at having a different sort of truth for science than for religion. Truth is truth. The you that awakes forma coma has the very same body as the you that entered the coma. There is a publicly available way to asses the meaning of "I" in "But was I really unconscious previously". It's missing from reincarnation. — Banno

Are caterpillars identical to butterflies?

"Theology as grammar" - Wittgenstein. -

Do human beings possess free will?This question concerns the grammar of intervention; What do we mean when we say that an agent "intervenes" upon a system to bring about a particular state of affairs?

For example, one might say that the Earth considered as an isolated system has "no choice" but to assume a particular orbit when subjected to gravitational forces exerted upon it by the rest of the solar system. Hence in this situation we have a notion of causality that relates a system taken independently and in isolation, namely the Earth, to the rest of the solar system considered as an external system. Here "no choice" means that the earth is expected to move differently given a different arrangement of the surrounding solar system, but it should also be noticed that the meaning of "different arrangement of the solar system" is itself partly determined by how the Earth itself moves. Hence even in this materialistic and atomistic example of an isolated system subject to external forces, the meaning of having no-choice is somewhat fuzzy and tautological in character.

But what about when considering the orbit of the Earth jointly with the motions of the rest of the solar system taken as a single, collective holistic system? When considering the solar system jointly, all that physics needs and has is an equation that describes the simultaneous motion of all the planets. As Bertrand Russell observed, the notion of causality that we had in the previous instance disappears when considering everything jointly, and in this latter context it would be meaningless to say that the earth's trajectory was determined by the solar system that it is simultaneously modelled with.

In a nutshell, causality is a meta-theoretic relation that relates a system considered as "foreground" to a context considered as "background". This implies that the question of free-will versus determinism is meaningless in the absolute sense in which everything is (hypothetically) considered simultaneously. -

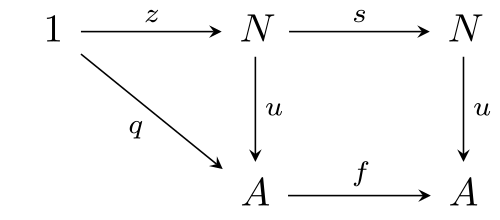

Can it be that some physicists believe in the actual infinite?The category theoretic description of the natural numbers does away with the pesky elements of the natural number "set" and externalises the notion of 'element' onto the objects counted.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Natural_numbers_object

And so the notion of elements isn't needed for the pure purpose of constructing abstract numbers.

Does that help? -

Philosophical justification for reincarnation..and no basis for calling it true. Reincarnation becomes a form of life that does not make contact with truth or falsehood. It's use - meaning - can only be in its social function. — Banno

Scientifically speaking, I agree, but of course, your argument also applies to the "you only live once" position, so it's a moot point.

But i don't agree that scientific truth and metaphysical truth are synonymous, due to the fact the latter directly concerns the logic of first-person experience, whereas the former is precluded from coming into contact with first-person experience due to the public semantics of scientific discourse , where identity relations are decided by public agreement with respect to propositions stateable in the third-person. Hence it is possible, imo, to accept the public meaningless of the scientific question, whilst accepting the private question to be metaphysically meaningful, and even potentially answerable in some philosophically critical sense.

To give a related example, if i awaken from a coma then I am said to have been "previously unconscious" by definition of the circumstances i am presently in, which includes such things as medical opinions i hear from loved ones around me, a brain-scan i am presented with showing an absence of critical neurological activity, and my self-observed tendency to abstain from memory recalling behavior (amnesia). As with the question of reincarnation, it is logical for me to ask "But was I really unconscious previously", or only in the tautological sense decided by public convention, where my "previous unconsciousness" is ironically decided by present observations that make no actual reference to a non-existence of first-person experience per-se? -

Philosophical justification for reincarnationPersonal identity isn't a topic that science is able to investigate, because identity relations are part of logic and ontology rather than empirically deducible matters of fact, and science is compatible with any set of identity relations, provided they are consistent.

Given any assumed set of identity relations, science only has the power to decide whether or not a given observable process conforms to those relations. For example, if a caterpillar is defined as being identical to the resulting butterfly, then scientific experiments have the potential to confirm whether or not a given caterpillar is identical to a given butterfly. But the result can neither confirm nor deny the reality of the assumed identity relation.

There a multiple cultural and practical factors as to why western culture has converged onto an assumed set of identity relations that makes rebirth not merely physically impossible but logically impossible. I think part of the reason is that scientific theories are initially easier to understand relative to an atomic ontology, such as periodic tables and subatomic particles, than holistic process ontologies. This is also reflected in logic and mathematics, where most students find set theory with elements easier to understand than category theory without elements. -

Can it be that some physicists believe in the actual infinite?Given that intuitionists who reject the existence of actual infinity also reject the law of excluded middle, they are likely to disagree with the assumption that the universe must either be finite or infinite.

For the intuitionist, truth is synonymous with verification of some sort, meaning that according to this stance there are no unknowable true propositions. This implies that if it is unknowable in principle as to whether the universe is finite or infinite, then there is no transcendental matter-of-fact as to which is the case.

Also, it should be mentioned that the commonest use-case of potential infinity involves an agent querying nature for the value of an unbounded variable and accepting the received response (if any). Therefore it is false to claim that denial of actual infinity entails denial of external reality. -

Philosophical justification for reincarnationPersonally, I am sympathetic with regards to beliefs in rebirth, due to logical reasons connected to the temporal philosophy of presentism that ontologically prioritises the present to the extent of rejecting the literal existence of the past. The implication is that memories aren't so much the recordings of bygone and static states of existence, but are part of the very meaning of what the past presently is.

Essentially by this view, the first-person subject is static and exists only "in a manner of speaking", with the concept of change applying only to presently observed things. -

A proposed solution to the Sorites ParadoxI personally have no problem with someone calling a single grain of sand a heap, even if that isn't my cup of tea. What harm could it do, and who am I to decree otherwise?

There is no a priori linguistic definition of "heap" in terms of any specific number of grains of sand,

— sime

Yes, that is the problem. — bongo fury

Why is linguistic imprecision a problem? "Heap" trades referential precision for flexibility, whilst retaining the necessary semantics for useful, albeit less precise communication. -

What’s the biggest difference Heidegger and Wittgenstein?The only theory of meaning Wittgenstein ever published was in the Tractatus, which was a solipsistic, subjectivist or idealistic doctrine of meaning that constituted conclusions he drew via methodological solipsism , that is to say by phenomenological investigation strictly in the first-person, that discounted the applicability and relevance of third-personal scientific rationalisization.

And the later Wittgenstein, whose solipsistic methodology remained the same as the earlier Wittgenstein and who now directly asserted that philosophy was purely therapeutic and descriptive and wasn't in the business of proposing theories, didn't immediately contradict himself by proposing the frankly ridiculous theory attributed to him that meaning is grounded in inter-subjective agreement or in some publicly obeyed rule-set sent decreed from above by the guardians of meaning in Platonia.

The confusion here, seem to partly stem from the public's lack of understanding of the positivistic epistemological ideas of his time that he was attacking, as well as a general lack of awareness regarding Wittgenstein's so-called "middle period", in which he wrote about his phenomenological inquiries and negative conclusions that there was no hope of obtaining a phenomenological theory of meaning of the sort proposed his earlier self proposed.

But that doesn't mean Witt then concluded "in that case, by appealing to the law of excluded middle realism is true. I propose a new epistemological foundation in which there is only one sort of meaning that is decided by the public, platonia or scientific naturalism in a mind-independent reality". All he concluded is that due to the overwhelming complexity and uncertainty of phenomenological analysis, it is impossible for himself to give an exhaustive and unconditional phenomenal theory accounting for his own use of words.

It is therefore understandable, as to why Wittgenstein was sympathetic towards Heidegger and could personally relate to Being and Time on the one hand, while at the same time insinuating that Being and Time was nonsensical when viewed as a collection of propositions with an inter-subjectively determinable truth-value.

Nonsense doesn't mean "false", it merely refers to an inability to determine the sense of a word when it used in a context from which it did not originate. Wittgenstein's sympathies towards Heidegger demonstrate that he did not believe the most important types of meaning to be inter-subjectively decided. Only inter-subjective meaning is inter-subjectively decided.

We can all agree that we can relate to Being in Time, without pretending to ourselves that we understand each-other's understanding of this work when viewing our agreement from the perspective of a different language-game. -

A proposed solution to the Sorites ParadoxAny finite number of grains of sand does not have this property.

— sime

So... isn't a heap? — bongo fury

There is no a priori linguistic definition of "heap" in terms of any specific number of grains of sand, which is why "heap" must be logically represented as referring to a potentially infinite number of grains of sand.

The role of potential infinity in a logical specification is to act as a placeholder for a number that is to be later decided by external actors or the environment, rather than the logician or programmer.

Agreed. But what is the smallest number of grains that would need considering by speakers as a particular case? Is it 1? — bongo fury

It is you and only you who gets to decide the answer to that question whenever you are next confronted by a growing or diminishing collection of sand grains.

I would be surprised if there isn't a population study that has attempted to quantify the mean number of grains of sand at which speaker of English judge a collection of sand to be a heap. A few hundred grains?? A few thousand? -

A proposed solution to the Sorites Paradoxlike imagining a heap of sand that never changes after a grain is removed or added.

— sime

... leading to the conclusion (incompatible with a premise, or there's no puzzle) that a single grain is a heap. Does that happen also with your "infinite" element, so that it can evaluate to 1? — bongo fury

No, that isn't the case. To summarise, a heap of sand can be defined as the list:

Heap := [ Heap, grain]

The list remains constant, regardless of how many grains are added to it or subtracted from it. Any finite number of grains of sand does not have this property. That is precisely what it means to say that a heap of sand has no inductive definition.

Where i differ with the OP, is his belief that it is an approach unconnected to ideas of fuzziness or ambiguity. This isn't the case, because the practical usage of infinity, such as the use of infinite loops in computer programs, is to defer the termination of the program to the environment. Or in the case of heaps of sand, the semantics which concern the precise moment when an actual heap of sand is considered to be mere grains of sand, isn't linguistically specified a priori but is decided by speakers on a case specific basis. -

A proposed solution to the Sorites ParadoxYour proposed solution sounds to be in a logical sense the same as mine, which is to consider the heap to be a co-inductive type.

First consider the recursive definition for the set of inductively constructed lists.

Inductive List := { [ ] AND x : Inductive List }

Evaluating this equation by substituting the left-hand side into the right-hand side is analogous to building every possible collection of sand-grains by starting from nothing and adding a grain at a time. Yet we don't call a collection of sand-grains constructed by this process a heap, because "heaps" aren't defined by induction.

In contrast, the set of co-inductively constructed lists is defined by switching the AND for an OR:

Co-inductive List := { [ ] OR x : Co-inductive List }

The set of co-inductive lists contains the inductive set of lists, but because it isn't obligated to build lists by starting from empty, it also includes an additional list of "infinite" length. By "infinite" we are merely referring to the fact this set contains the definition of list that might never terminate upon iterated evaluation.

The former type of list corresponds to the natural numbers, whereas the latter type corresponds to the conatural numbers, otherwise known as the extended natural numbers that includes a numeral for infinity, which in computing can be used to denote programs will never halt to produce an output.

I think that the grammar corresponding to "a heap of sand" is analogous to the "infinite" element of a coinductive list, which as you say is like imagining a heap of sand that never changes after a grain is removed or added. -

Have we really proved the existence of irrational numbers?What's a "theorem prover"? Computer program? A tutor? — jgill

More generally, it is a dependently typed logical programming language, with clause resolution and other rules of logical inference, together with SAT solvers, methods of analytic tableaux and heuristics for automated or interactive theorem proving.

Lean with Mathlib, to my understanding is a state of the art approach to logic and mathematics programming that embodies the above principles , an approach which together with advances in deep learning theorem proving will undoubtedly revolutionise mathematics education , automation and research. Remarkably, the mathematics library of lean now codes the proofs of a lot of undergrad level mathematics.

https://leanprover.github.io/live/latest/ -

Have we really proved the existence of irrational numbers?I don’t regard professional mathematicians as being trustworthy or helpful with regards to the literal truth of their subject, for several reasons.

1. They can be expected to exhibit a political bias towards inflating ontological claims in mathematics , in the same way that professional chess players can be expected to inflate the importance of chess and exhibit bias against other games. Traditionally this is bias is evident in the continued prevalence of classical logic in the justification of mathematical claims and the high percentage of mathematicians who are platonists, a position that is troubling to any engineer or computer scientist who unlike pure mathematicians have actual responsibilities regarding the physical actualization and interpretation of mathematical results.

2. The subject of ontological claims and commitments is the domain of logic rather than of mathematics, and the classical mathematician isn’t logic savvy, unlike today’s generation of mathematics undergraduates who are studying mathematics using theorem provers from the outset. -

Have we really proved the existence of irrational numbers?

yes, sorry, i should have clarified that i was referring to number in the extensional sense, i.e. as an obtainable state of a calculation. This is because i understood the OP as questioning the existence of sqrt 2 in this extensional sense.

Naturally, Sqrt 2 exists intensionally in the constructive sense of an algorithm that generates any finite cauchy sequence of computable reals, whose limit x fulfils the axiomatic definition

sqrt 2:= x : x^2 = 1.

Furthermore, it is constructively provable that the limit is irrational in the sense of being separated from any computable rational number. And the sqrt of 2 intensionally exists in this sense, irrespective of whether the limit of this process of calculation is axiomatically accepted as being a number in the extensional sense.

Of course, normally when we assign numbers to physical lengths we aren't resorting to logical construction, nor even necessarily to calculation, which means that our practical use of numbers is logically under-determined. We could for instance, declare the hypotenuse of unit length triangles to be "real" lengths that correspond to extensional numbers relative to some novel logical construction of numbers, in which the unit lengths of the other sides of the triangle only exist intensionally as limits in this number system.

In my opinion, constructive mathematics should permit a plurality of axiomatic systems to represent our use of numbers. That way we don't have to make arbitrary a priori decisions as to which numbers only exist as limits. -

Collingwood's PresuppositionsDoes Collingwood undermine his own arguments, by begging his own ontological assumptions, when he makes a hard distinction between absolute presuppositions and propositions?

Initially, SEP's article on Collingwood says that the difference between presuppositions and propositions isn't one of content, but one of role:

"Whether a statement is a “proposition” or a “presupposition” is determined not by its content but by the role that the statement plays in the logic of question and answer. If its role is to answer a question, then it is a proposition and it has a truth-value. If its role is to give rise to a question, then it is a presupposition and it does not have a truth-value. Some statements can play different roles. They may be both propositional answers to questions and presuppositions which give rise to questions. For example, that an object is for something, that it has a function may be a presupposition which gives rise to the question “what is that thing for?”, but it may also be an answer to a question if the statement has the role of an assertion. "

So far, so good, for no Positivist could disagree with that; whenever an assertion is understood to be meant presuppositionally it isn't used in a truth-apt sense, but as a temporary conditional assertion upon which a subsequent course of a truth-apt epistemological enquiry is founded. This is to understand a presupposition as being a modest and consciously subjective assertion that is comparable to an axiom or a Wittgenstein 'hinge proposition'. But then immediately after that (emphasis added), the article makes a stronger claim on behalf of Collingwood, saying

"Philosophical analysis is concerned with a special kind of presupposition, one which has only one role in the logic of question and answer, namely that of giving rise to questions. Collingwood calls these presuppositions “absolute”. Absolute presuppositions are foundational assumptions that enable certain lines of questioning but are not themselves open to scrutiny."

At first I wondered if SEP was overstating Collingwood's position. For if the distinction of these types of sentences is one of role rather than content, then presumably he was merely pragmatic and did not think that his distinctions had significant implications with respect to epistemological conclusions, but only with respect to the defence of a plurality of epistemological methodologies, none of which have the capacity to contradict the assertions that the other methodologies arrive at. But then the article makes it clear that his position is even stronger:

" Collingwood’s account of absolute presuppositions generates an interesting angle on the question of scepticism concerning induction. Hume had argued that inductive inferences rely on the principle of the uniformity of nature. If it is true that the future resembles the past, then inferences such as “the sun will rise tomorrow” are inductively justified. However, since the principle is neither a proposition about matters of fact nor one about relations of ideas the proposition “nature is uniform” is an illegitimate metaphysical proposition and inductive inferences lack justification. The principle of the uniformity of nature, Collingwood argues, is not a proposition, but an absolute presupposition, one which cannot be denied without undermining empirical science. As it is an absolute presupposition the notion of verifiability does not apply to it because it does its job not in so far as it is true, or even believed to be true, but in so far as it is presupposed. The demand that it should be verified is nonsensical and the question that Hume ask does not therefore arise:

…any question involving the presupposition that an absolute presupposition is a proposition, such as the question “Is it true?” “What evidence is there for it?” “How can it be demonstrated?” “What right have we to presuppose it if it can’t?”, is a nonsense question. (EM 1998: 33) "

If the SEP is portraying his beliefs correctly, then I think Collingwood has jumped the sharked from making reasonable and modest epistemological commentary, to arriving at a dogmatic position regarding presuppositions that appears to beg the very ontological premises which he claimed philosophy isn't about. For you cannot insist that Hume was mistaken to question the uniformity of nature on the basis of it being an absolute presupposition, without adopting the dogmatic ontological standpoint that absolute presuppositions constitute objective existential claims. -

Have we really proved the existence of irrational numbers?Isn't denying the existence of sqrt of 2 on the grounds that it isn't a computable number a bit like denying the existence of a "heap" of sand on the grounds that a "heap" isn't derivable from a granular definition of sand?

The "Sqrt 2" is at the very least, pragmatically useful as a moniker for the hypotenuse of a certain class of visually recognisable triangle, and it should be remembered that we have as much empirical justification for labelling the hypotenuse with sqrt 2 as we have for labelling its other sides with "1".

Zeno's reaction to his paradox is also similar to yours, in his conclusion that the existence of motion is impossible on the grounds that motion cannot be constructed from positional information. But the converse is also true: a position, in the logical sense, cannot be constructed by slowing down motion. Motion and position are irreconcilable concepts pertaining to mutually exclusive starting conditions of a system and mutually exclusive choices of disturbance of the system by an observer thereon after. Each concept can only informally represent the other as a "limit" that can only be approached but never arrived at.

The constructivist isn't forced into believing in the literal existence of hypertasks as the platonist might insists, rather the constructivist only needs to deny the existence of a universal constructive epistemological foundation. -

Existential angst of being physically at the center of my universeI suggest you google Nelson Goodman and his ideas concerning irrealism that more or less convey the basic structure of community-level solipsistic logic. His argumentation embraces and accommodates, rather than rejects, the inevitable conflicts of speech that arise in community discussions of truth, such as when every member of a community of solipsists declares himself to be the centre of the universe.

The traditional way of thinking is to assume that whenever a community of speakers discuss the universe in an absolute sense, they must be referring to the "same" universe. But this is proposterous according to a Goodmanian irrealist, according to whom each and every speaker cannot transcend their personal frames of reference and so cannot refer to the same universe in an absolute sense, even when they insist otherwise.

Consquently the irrealist understands every assertion, including assertions of absolute truth, as being relative to the speaker and of the form "according to speaker X assertion Y is true". -

Help coping with SolipsismNot all individualists are solipsists, and not all solipsists are individualists.

And why can't a solipsist be a realist? after all, the thought that the external world has independent existence is just a thought, and solipsists accept the existence of thoughts. -

Godel's Incompleteness Theorems vs Justified True Beliefthink you are focusing too much on the fact that theoremhood is not strongly representable in PA, with the consequence that you are ignoring the fact that it is weakly representable in PA. Indeed, while theoremhood is not computable, it is computably enumerable. In other words, there is an algorithm which lists all and only theorems of PA. It exploits the fact that, given your favorite proof system, whether or not a sequence of formulas is a proof of a sentence of PA is decidable. Call the algorithm which decides that "Check Proof". Here's an algorithm which lists all the theorems of PA, relative, of course, to some Gödel coding:

Step 1: Check whether n is the Gödel number of a sequence of formulas of PA (starting with 0). If YES, go to the next step. Otherwise, go to the next number (i.e. n+1).

Step 2: Decode the sequence of formulas and use Check Proof to see if it is a proof. If YES, go to the next step. Otherwise, go back to Step 1 using as input n+1.

Step 3: Erase all the formulas in the sequence except the last. Go back to Step 1, using as input n+1.

This (horrible) algorithm lists all the theorems, i.e. if S is a theorem of PA, it will eventually appear in this list. Obviously, this cannot be used to decide whether or not a given formula is a theorem, since, if it is not a theorem, then we will never know it isn't, since the list is endless. But, again, it can be used to list all the theorems. My point is that there is nothing comparable for the truths, i.e. there is no algorithm that lists all the truths. In fact, by Tarski's theorem, there can be no such algorithm. So, again, the two lists (the list of all the theorems, the list of all the truths) are not the same, whence the concepts are different. — Nagase

I'm still confused as to where and how we disagree. I suspect the issue might be mostly terminological, due to your use of modal notions versus my deflationary/constructive terminology. However it is possibly worth recalling that PA must have the following theorem for any provability predicate

PA |-- Prov('G') --> ~G for any Godel sentence G.

In other words, there cannot be an exhaustive and infallible enumeration of theoremhood within PA. - and here we aren't referring to the failure of ~Prov to enumerate the non-theorems - rather we are referring to the inability of Prov to correctly enumerate all and every derivable theorem.

We can of course construct an infallible Prov by defining it to enumerate only the godel-numbers that have been independently determined to be proofs via brute-force checking. In which case Prov along with the godel-numbering system are merely redundant accountancy of what we've already derived, and in which case Prov sacrifices exhaustivity for infallibility.

Alternatively, prov could be an 'a priori' algorithmic 'guess' as to theoremhood , in which case it can be exhaustive , e.g. by guessing "True" to every godel number, but at the cost of infallibility, in guessing both correctly and incorrectly as to theoremhood.

But we're at least both in agreement it seems, that there isn't an algorithm for listing all and only the actual theorems of PA - which is precisely the reason why truth should be constructively identified with actual derivability, as opposed to being identified with whatever is unreliably or incompletely indicated by a 'provability'/'truth' predicate.

So where and how do we diverge?

The upshot of all this is that, in my opinion, constructivists should resist the temptation of reducing truth to provability. Instead, they should follow Dummett and Heyting (on some of their most sober moments, anyway) and declare truth to be a meaningless notion. If truth were reducible to provability, then it would be a constructively respectable notion. But it isn't (because of the above considerations). So the constructivist should reject it. (Unsurprisingly, most constructivists who tried to explicate truth in terms of provability invariably ended up in a conceptual mess---cf. Raatikainen's article "Conceptions of truth in intuitionism" for an analysis that corroborates this point.) — Nagase

Dummett's overall arguments sound roughly similar to my deflationary position of truth in mathematical logic'; software engineers don't say that the operations of a software library has no truth value, rather they define truth practically in terms of software-testing, without appeals to the choice axioms, or the Law of excluded middle.

What i think classical philosophers overlook is that the absolute consistency of PA isn't knowable, or even intelligible. As an absolute notion, undecidability is meaningless. -

The grounding of all moralityIn your view, if flourishing has to be the intention of a moral action, then how should moral intentionality be determined?

— sime

Hi sime, sorry, did not understand the question, can you restate in a different form? Thanks! — Thomas Quine

What is your position regarding moral intention, moral freedom, moral responsibility and moral competency? How are these things definable and measurable?

Presumably you don't consider social utility to be sufficient grounds for defining morality, for otherwise, morality is indistinguishable from luck.... -

Godel's Incompleteness Theorems vs Justified True BeliefI don't think Löb's theorem supports the constructivist position. That's because truth is generally taken, prima facie to obey the capture and release principles: if T('S'), then S (release), and, if S, then T('S') (capture). But what Löb's theorem shows is that proof does not obey the release principle. So there is at least something suspicious going on here. — Nagase

Constructively, Prov doesn't fail either the capture or release properties of a truth predicate with respect to decided sentences, rather Prov doesn't supply negative truth value when classifying undecided sentences that no axiomatic system can decide without either begging the question, or by performing a potentially infinite proof search equivalent to doing the same in Peano arithmetic.

Perhaps part of the confusion/suspicion comes from overlooking the following symmetry in what Peano arithmetic cannot derive

PA |-/- (For All S: S --> Prov('S')) ( since compilation is potentially infinite)

PA |-/- (For All S: Prov('S') --> S ) ( since decompilation is potentially infinite)

Löb's theorem only deduces the existence of an as-of-yet undecided object on the assumption that the decompilation process of it's respective code terminates. And yet the undecided object will only compile into a code in the first place, if it is decidable. Therefore Löb's theorem does not have constructively relevant implications.

Why would you want, let alone expect, a truth predicate to capture and release the properties of potentially infinite objects whose existence is potentially non-demonstrable?

Moreover, one can show that the addition of a minimally adequate truth-predicate to PA (one that respects the compositional nature of truth) is not conservative over PA. Call this theory CT (for compositional truth). Then CT⊢∀x(Sent(x)→(Prov(x)→T(x)))CT⊢∀x(Sent(x)→(Prov(x)→T(x))), where "T" is the truth predicate. As a corollary, CT proves the consistency of PA. So truth, unlike provability, is not conservative over PA. — Nagase

In other words, introducing new axioms to represent undecided formulas generally permits the derivation of new sentences in a vacuous manner.

Finally, you have yet to reply to my argument regarding the computability properties of the two predicates, namely that one does have an algorithm for listing all the theorems of PA, whereas one does not have an algorithm for listing all the truths of PA. So the two cannot be identical. — Nagase

The set of theorems of PA isn't recursive due to the halting problem, meaning that any proposed test of theoremhood by a "truth predicate" is bound to be either incomplete or to contain an infinite number of mistakes.

Consequently, the "truth" of PA consists of the explicit construction of each and every theorem, doing everything the hard way.

Edit: I rushed this post, so came back and rectified some mistakes. -

How to accept the unnaturalness of modern civilization?As an aside, being an engineer you sound well positioned to lead a digital nomadic lifestyle close to the outdoors

-

The grounding of all moralityIn your view, if flourishing has to be the intention of a moral action, then how should moral intentionality be determined?

sime

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum