Comments

-

Nothing to do with Dennett's "Quining Qualia"But the distinction between primary and secondary attributes is hard-baked into our worldview. There’s no easy way to unscramble this particular omelette. Heck, Dennett won’t even admit there’s a need to make the effort, or that there is an issue to solve. Modern scientific method ‘brackets out’ the subjective - that is the meaning of the ‘view from nowhere’. And then, having bracketed it out, it says it can’t find any sign of its reality. There’s a really basic sleight-of-hand behind this entire debate, but for those who can’t see it, it’s devilishly hard to explain. — Wayfarer

I think the first step to unscrambling that omelette is to reject the 'view from nowhere', and thus also the 'bracketing out' of the human perspective.

So-called "primary attributes" ultimately derive their meaning from their role in human experience. Einstein notably developed his special theory of relativity as a construction based on measuring-rods, clocks, and observers.

"Secondary attributes" similarly derive their meaning from their role in human experience. Alice observes that the red measuring-rod has black markings at one centimeter intervals. That's the view from somewhere - the perspective of Alice. So there's no good reason to dichotomize human experience in those primary/secondary terms (which is just the Lockean manifestation of subject/object duality). -

Nothing to do with Dennett's "Quining Qualia"Okay so on this ordinary language scheme, subject/object duality is necessary. — Olivier5

I don't understand your point. Can you elaborate? -

Nothing to do with Dennett's "Quining Qualia"English grammar makes no distinction between subject and object. — Olivier5

I'm referring to philosophical subject/object dualism, not grammar. The grammatical distinction is very useful. -

Nothing to do with Dennett's "Quining Qualia"Because some of them are properties of perception.

...

All of these sort of example demonstrate that our experiences are not simply reflections of the world. They're generated by our act of perceiving and other mental activities. So appealing to some direct realism or externalism still needs to account for perceptual relativity and all the other stuff occurring for the organism. — Marchesk

Statements such as "Alice feels cold" and "the apple is red" abstract over the underlying physical processes. First, as abstractions, they are direct by design and are (high-level) reflections of the world (being true or false). And second, as abstractions, they presuppose a particular perspective. So that permits perceptual relativity.

Note that "feels cold" doesn't predicate Alice's sentience, or perceptions, it predicates Alice herself. The statement does, however, presuppose that Alice is sentient, otherwise it would be a category mistake.

On this ordinary language scheme, subject/object duality is unnecessary, and an internal/external distinction is just an artefact of that duality. So a question of qualia doesn't arise.

I think there's a parallel between qualia and 'secondary qualities' — Wayfarer

Yes, I agree.

The primary qualities are those which are subject to precise quantification, while tastes, smells and so on are secondary and associated with the obsering subject. I think in physicalism, only bearers of primary attributes - that would be 'matter' - is real. It's those annoying 'inneffable feels' that have to be disolved in the acid of Darwin's dangerous idea into the doings of the only real sources of agency, which are molecules: — Wayfarer

So an alternative to that is that Alice's feeling of the cold, or that the apple is red, etc., are first-class attributions which more specialized scientific statements derive from and explain. We're interested in scientific explanations of how it is that Alice feels cold, not in creating artificial distinctions that make such explanations impossible in principle or, on the other hand, denying that they are real at all. -

Nothing to do with Dennett's "Quining Qualia"Humorously. — Srap Tasmaner

:up:

Ah. I hope so! I was wondering if we'd get into experiential spatiality stuff (proximity, the experiential aspects of place etc) as a result of Andrew M's post. I hope it went straight over my head! — fdrake

Sorry fdrake! It was satire. I regard qualia as a philosophical fiction. My post was an attempt to vividly illustrate in a slightly different context some of the standard confusions that arise. A different kind of intuition pump. Which is not to say that there isn't some philosopher somewhere that might endorse that view!

That aside, thanks for your excellent summary which seems right to me. In particular, I think exposing the often implicit subject/object duality and recognizing the relational nature of experience goes a long way towards clarifying the issues.

Why wouldn't the response just be that there's nothing particularly special about one location over another. Unless location is specific to a question at hand, i.e. the view of a building from a particular place, I don't see how it presents any kind of problem for D. — Wayfarer

Well, indeed. But I think we could say the same for red apples, or illusions, or whatever. They're just normal aspects of our experience which nonetheless seem to generate particular kinds of philosophical confusion. -

Nothing to do with Dennett's "Quining Qualia"So, here it is:

Quining Qualia

Let's take a closer look.

"My goal is subversive. I am out to overthrow an idea that, in one form or another, is "obvious" to most people--to scientists, philosophers, lay people. My quarry is frustratingly elusive; no sooner does it retreat in the face of one argument than "it" reappears, apparently innocent of all charges, in a new guise." — Banno

My challenge to Dennett and the qualia-deniers on this thread, answer me this:

Location is subjective. I'm standing here and you're standing there. That's a genuinely hard problem for science to explain. Nonetheless location qualia is undeniable and anyone who does deny it must be a zombie. But zombies still shuffle around, and use language claiming to do so. So the onus is on materialists to explain how that is possible without presupposing the very location qualia they deny. (The mind boggles.)

Further, we know that there is a "what it is like" to be standing here that is private and ineffable. It's quite likely that bats don't stand here in the way that humans do. There's apparently even suggestions that they hang upside down (not that that would be verifiable - it's purely a thought experiment which means that it is therefore a logical possibility that can't be ruled out). For a further knock-down argument, no one can deny that it seems that I'm standing here. That's location qualia too.

In conclusion, rejecting location qualia not only defies common sense, it denies what it means to be human.

Q.E.D.

(And I haven't even got to size qualia yet. Alice says that Bob is fat, which Bob denies. Explain that, science.) -

What is Dennett’s point against Strawson?I think you're right. I read a remark by an Oxford don that every philosopher is one or the other, and I'm definitely the former. At least it gives an amicable ground for disagreement! — Wayfarer

:up: -

What is Dennett’s point against Strawson?the distinction between objective and subjective is clear in plain languge.

1. Object: a material thing that can be seen and touched.

"he was dragging a large object"

2. a person or thing to which a specified action or feeling is directed.

"he became the object of a criminal investigation" — Wayfarer

The ordinary usages are fine. I'm arguing against the specifically philosophical subject/object distinction which is also stated in that source:

1.1 Philosophy A thing external to the thinking mind or subject.

For reference, see also subject (philosophy) and object (philosophy).

Incidentally I am reading Nagel's View from Nowhere, which is a slog, but I don't think it says anything like what you appear to think it says. It looks at the way science presumes to arrive at a view from nowhere, that is, one that is not at all under the influence of subjective factors. It goes through a number of paradigmantic philosophical positions in the light ot the contrast between the impersonal, scientific view, and the perspective of living beings - subject! — Wayfarer

That's the philosophical subject/object dualism that I'm arguing against. Scientific models are abstractions of human experience, they are not independent of human experience.

The solution is to reject dualism in its entirety, and understand the human being as a natural and inseparable unity.

— Andrew M

The word 'natural' already containes carries baggage! You're still narrowing the scope of what the human might be, to a definitioin that is satisfactory to naturalism, when that is one of the points at issue. The Greeks, for instance, tried to trace the origin of reason in the mind and in universe through reasoned argument and introspection. — Wayfarer

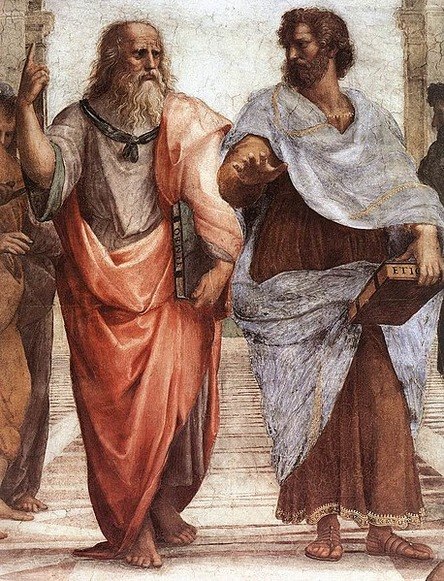

Human nature (which includes human rationality) is a part of nature. Yours and my disagreement here reflects the disagreement between Plato and Aristotle. Aristotle considered form to be immanent in nature (hence hylomorphism), whereas Plato considered form to transcend nature (hence Plato's Forms). -

What is Dennett’s point against Strawson?I don’t accept Hackers elision of the duality of subject and object. — Wayfarer

So I'm pointing out that it's a purely philosophical distinction that has no use in ordinary life or scientific practice.

Arguing against systematically misleading terminology is entirely consistent with Hacker's, Wittgenstein's and Aristotle's approaches. And to argue against dualism doesn't imply agreement with Dennett's materialism. As I noted to you earlier, I reject both materialism and dualism.

Materialism fails because it still accepts half of the dualist's premise, namely Nagel's "view from nowhere". That barren landscape may well abrogate one's sense of wonder, but the solution is not to tack on ghosts. The solution is to reject dualism in its entirety, and understand the human being as a natural and inseparable unity. -

What is Dennett’s point against Strawson?Here's Hacker's proposal again: that sentience emerges from the evolution of living organisms.

Do you think that's a valid problem for science to investigate?

— Andrew M

Yes of course - evolutionary biology, cognitive science, and so on. Does not, however, vitiate the fundamental issue. — Wayfarer

It seems to me that the emergence of sentience is the fundamental issue. Now note how Nagel frames the issue:

"it seems natural to think that the physical sciences can in principle provide the basis for an explanation of the mental aspects of reality as well — that physics can aspire finally to be a theory of everything.

However, I believe this possibility is ruled out by the conditions that have defined the physical sciences from the beginning. The physical sciences can describe organisms like ourselves as parts of the objective spatio-temporal order – our structure and behavior in space and time – but they cannot describe the subjective experiences of such organisms or how the world appears to their different particular points of view."

— Thomas Nagel — Wayfarer

The inclusion of objective and subjective only appears in Nagel's proposal, not Hacker's. The description of the "objective spatio-temporal order" is Nagel's "view from nowhere". "Subjective experiences" translates as "radically private experiences" (that can't be described "objectively"). Thus a hard problem arises by definition, due to the subject/object dualism.

No such hard problem arises in Hacker's proposal since it doesn't assume subject/object dualism. In ordinary language, we experience the world, and therefore that is what we naturally investigate and describe (from our particular points of view). -

What is Dennett’s point against Strawson?It's actually orthodox Christian doctrine that believers undergo bodily resurrection. So dualism isn't required even there.

— Andrew M

'At death the soul is separated from the body and exists in a conscious or unconscious disembodied state. But on the future Day of Judgment souls will be re-embodied (whether in their former but now transfigured earthly bodies or in new resurrection bodies) and will live eternally in the heavenly kingdom.' ~ Encyc. Brittanica

Not saying I believe it, but it's clearly incompatible with Dennett's neo-darwinian materialism, which is not surprising, given that he's a militant atheist. — Wayfarer

A separate soul implies dualism. But there is no definite Christian position on a separate soul, as IEP notes:

c. The Resurrection of the Body

Whereas most Greek philosophers believed that immortality implies solely the survival of the soul, the three great monotheistic religions (Judaism, Christianity and Islam) consider that immortality is achieved through the resurrection of the body at the time of the Final Judgment. The very same bodies that once constituted persons shall rise again, in order to be judged by God. None of these great faiths has a definite position on the existence of an immortal soul. Therefore, traditionally, Jews, Christians and Muslims have believed that, at the time of death, the soul detaches from the body and continues on to exist in an intermediate incorporeal state until the moment of resurrection. Some others, however, believe that there is no intermediate state: with death, the person ceases to exist, and in a sense, resumes existence at the time of resurrection. — Immortality - IEP

Orthodox Christians do believe God is spirit, so their worldview is still dualistic. — Marchesk

Yes though, as the above IEP quote suggests, human soul/body dualism may have more to do with the influence of Platonism than with monotheistic religion itself. -

What is Dennett’s point against Strawson?The problem is the implicit dualism in the claim. There are no 'first-person' versus 'third-person' perspectives. There is just your perspective, my perspective, and Alice's perspective. Each is a distinctive perspective of the world, but it is a world that we all participate in, and use common language to describe.

— Andrew M

The problem with this is that the world is more than individual perspectives. — Marchesk

It is. But note that describing that world requires a perspective whether in day-to-day life, or as a scientist performing specialized experiments. The latter is just a natural extension of the former, it's not "a view from nowhere".

Science describes a world independent of that. We can't sense most of what science tells us, and what we do sense is based on our particular biology, which science has to work to abstract from to arrive at mathematical models that are predictive and explain the world as it appears to us. — Marchesk

Yes, however those abstractions are not Platonic, they are a function of our perspective on the world.

Another problem is that people do have private thoughts, dreams, feelings. We can't always know that Alice's tooth is aching, or whether she's faking. But she knows, because she's the one feeling or faking the pain. — Marchesk

Yes. But what I'm arguing against is the idea that one's thoughts, dreams and feelings are radically, or intrinsically, private. That is, there is always a physical (and so, in principle, detectable) difference between a person in pain and a person faking pain, or between a person thinking about an apple and a person not thinking about an apple.

We also don't know what it's like if her brain works in an idiosyncratic way from our own. Thus people who have no inner dialog, people who think in images, people with odd neurological conditions and so on. — Marchesk

Yes. But that again is a manifestation of some physical difference. In principle, it is possible is to modify a person's physical state such that they experience things in different ways. Maybe Mary in her room discovers how to modify her own brain or eyes to perceive color. -

What is Dennett’s point against Strawson?It fixes the conceptual problem at issue. Hacker makes a concrete proposal that doesn't assume dualism.

— Andrew M

However, Christian doctrine must allow for the immortality of the soul, must it not? — Wayfarer

It's actually orthodox Christian doctrine that believers undergo bodily resurrection. So dualism isn't required even there.

Here's Hacker's proposal again: that sentience emerges from the evolution of living organisms.

Do you think that's a valid problem for science to investigate? -

What is Dennett’s point against Strawson?I'm very open to hylomorphism, but the Aristotelian 'hyle' is nothing like the modern conception of matter. — Wayfarer

Correct.

Secondly, hylomorphic dualism still implies a duality, insofar as 'the rational soul' is the principle within the human which is in principle immortal. That is highly developed in various forms of Thomistic philosophy, and so is still largely accepted by many Catholics, however for very obvious reasons is completely incompatible with Dennett's Darwinian materialism. And it's still dualism! — Wayfarer

The phrase "hylomorphic dualism" is a label coined for the Thomist version of hylomorphism:

Hylemorphic dualism is the approach to the mind-body problem taken by Aquinas and the Thomist tradition more generally. (The label may have been coined by David Oderberg... — Edward Feser

Whereas, to the contrary, Aristotle's hylomorphism is not dualist. Matter and form (of which the soul is an example) are not separable from particulars except as abstractions:

So, Aristotle claims, “It’s clear that the soul is not separable from the body – or that certain parts of it, if it naturally has parts, are not separable from the body” (De Anima ii 1, 413a3–5).

...

His hylomorphism, then, embraces neither reductive materialism nor Platonic dualism. Instead, it seeks to steer a middle course between these alternatives by pointing out, implicitly, and rightly, that these are not exhaustive options. — Hylomorphic Soul-Body Relations: Materialism, Dualism, Sui Generis? - Aristotle’s Psychology - SEP

The philosopher Peter Hacker argues that the hard problem is misguided in that it asks how consciousness can emerge from matter, whereas in fact sentience emerges from the evolution of living organisms.

— Wikipedia

It just re-states the problem in other terms, it doesn't solve it. — Wayfarer

It fixes the conceptual problem at issue. Hacker makes a concrete proposal that doesn't assume dualism. -

What is Dennett’s point against Strawson?There is plainly a distinction between the first- and third-person perspectives, as is implied by grammar itself! — Wayfarer

I pointed out the grammatical distinctions earlier. "Wayfarer observes the world" versus "The world is observed by Wayfarer". Grammatically, the subject and object are interchangeable.

Distinct from that, there is no "third-person perspective", understood as "a view from nowhere". And there is no "first-person perspective", understood as "radically private and subjective". There are just human beings with their individual human views of the world.

And furthermore, it is also undeniable that people have different perspective, for the obvious reason that if we did not, then there would no individuation. — Wayfarer

Yes, that has been just my point, as I say above. But ...

Persons are subjects of experience, and that dimension of existence is not something that can be fully captured from a third-person perspective. — Wayfarer

... see how you now move to the "view from nowhere", which can't capture "radical privacy and subjectivity"? That is the dualism I'm rejecting. Those philosophical usages are implicitly assumed without argument.

In the WIKI article you provided the link to, we read:

In contrast with Chalmers, Dennett argues that consciousness is not a fundamental feature of the universe and instead will eventually be fully explained by natural phenomena. Instead of involving the nonphysical, he says, consciousness merely plays tricks on people so that it appears nonphysical—in other words, it simply seems like it requires nonphysical features to account for its powers. In this way, Dennett compares consciousness to stage magic and its capability to create extraordinary illusions out of ordinary things.

Questions: why is it important for Dennett to prove that 'consciousness is not a fundamental feature of the Universe'?

What currently prevents it from being fully explained by natural phenomena? — Wayfarer

Presumably Dennett is arguing for what he thinks is true - I don't know his motivations beyond that. However, I do agree with Hacker (as noted here) that what requires explaining is how sentience emerges from the evolution of living organisms, not how consciousness can emerge from matter. Without the dualism, the landscape and the nature of the problems look very different, and not impossible in principle.

The universe appears to contain elements that possess subjectivity. Let's head toward a theory of consciousness that includes that.

— frank

Mind, I suspect, is not an inexplicable accident or a divine and anomalous gift but a basic aspect of nature that we will not understand until we transcend the built-in limits of contemporary scientific orthodoxy.

Thomas Nagel The Core of Mind and Cosmos — Wayfarer

The alternatives are not simply materialism and dualism. As you may know, my own position is hylomorphism. -

What is Dennett’s point against Strawson?Substance dualism? Chalmers is famous for suggesting property dualism at least methodologically. But beyond that, he just invites speculation about how to bring phenomenal consciousness into the realm of science. The universe appears to contain elements that possess subjectivity. Let's head toward a theory of consciousness that includes that. — frank

I'm arguing against the philosophical subject/object distinction which is the underlying premise of both Descartes' and Chalmers' dualism. My main argument can be found earlier in the thread here. -

What is Dennett’s point against Strawson?These categories are from neuroscience. Should scientists not use them? — frank

There's no problem where there is an operational meaning in terms of people's reports (patient and scientist, say). My argument is with dualism. -

What is Dennett’s point against Strawson?Yes, seeing someone do something is different to doing it yourself. However yours and my view is not 'a view from nowhere', and neither is Alice's experience radically private or subjective. As human beings, we can use the same language to describe Alice's activity as she can.

— Andrew M

Sorry, but I think you’re missing the point. The basis of the whole debate is whether there is an essential difference, something that can’t be captured objectively, about the first-person perspective. Obviously we can ‘use the same language’ and if you say ‘Alice kicks the ball’ of course I will know what you mean. But that misses the point of the argument. — Wayfarer

The problem is the implicit dualism in the claim. There are no 'first-person' versus 'third-person' perspectives. There is just your perspective, my perspective, and Alice's perspective. Each is a distinctive perspective of the world, but it is a world that we all participate in, and use common language to describe.

The really hard problem of consciousness is the problem of experience. When we think and perceive, there is a whir of information-processing, but there is also a subjective aspect. As Nagel (1974) has put it, there is something it is like to be a conscious organism. This subjective aspect is experience. When we see, for example, we experience visual sensations: the felt quality of redness, the experience of dark and light, the quality of depth in a visual field. Other experiences go along with perception in different modalities: the sound of a clarinet, the smell of mothballs. Then there are bodily sensations, from pains to orgasms; mental images that are conjured up internally; the felt quality of emotion, and the experience of a stream of conscious thought. What unites all of these states is that there is something it is like to be in them. All of them are states of experience. — David Chalmers

Experience, in its ordinary sense, is one's practical contact with the world. But note that Chalmers' definition decouples experience from the world, which is dualism, and that is what produces 'the hard problem'. As Peter Hacker puts it, "The philosophical [hard] problem, like all philosophical problems, is a confusion in the conceptual scheme." -

What is Dennett’s point against Strawson?But, nevertheless, there is a valid distinction to be made between the first- and third-person perspective. In other words, me seeing Alice kick the ball is completely different to me kicking it. Of course, to you, then both me and Alice are third parties, but the point remains. — Wayfarer

Yes, seeing someone do something is different to doing it yourself. However yours and my view is not 'a view from nowhere', and neither is Alice's experience radically private or subjective. As human beings, we can use the same language to describe Alice's activity as she can.

↪Andrew M

"So if that philosophical distinction is rejected, both in whole and in part, then what are we left with? I think ordinary language serves us just fine here."

Perhaps the point, the whole point of this world is to be a vehicle for experience. — Punshhh

Maybe! Certainly that is what our ordinary language is grounded in. -

Determinism, Reversibility, Decoherence and Transaction@Kenosha Kid

Once the emitter and the absorber "handshake" (which is sometimes described by another pseudo-process, which I haven't investigated), the "tails" of the wavefunctions going back in time from the emitter and forward in time from the absorber cancel out, as are the imaginary parts of the waves between them, leaving only the superposed real parts of the offer and confirmation waves. To any observer this will look as if a wave traveled from the emitter to the absorber. — SophistiCat

So that is how it appears to an observer. What actually happens once a handshake has occurred, and thus a single destination has been determined? In the double-slit experiment, does the electron follow a definite, albeit unknown, trajectory through one and only one of the slits, similar to pilot wave theory? Or does an electron essentially just disappear from the source and appear at the destination a short time later (a kind of non-local electron/hole exchange)? Or does it travel all possible paths to the destination as a wave? -

Determinism, Reversibility, Decoherence and TransactionFor anyone curious about the puzzle I presented earlier...

So I opened an account at the bank with $100 at an imaginary 314% interest rate. A year later, the bank claims I owe them $100! They say that if I keep my account open for another year, I'll get my $100 back. Should I trust them, or just pay the $100 and close the account? — Andrew M

...The short answer is, yes, I can trust them. Here's the worked out solution.

Euler's formula is:

e represents continuous growth starting from 1, at a rate indicated by the exponent. If the growth rate is 0, we remain at the starting point (i.e., e^0 = 1). Similarly, starting from $100, we remain at $100 (i.e., 100 * e^0 = 100 * 1 = 100).

While real exponential growth occurs along the real number line, imaginary growth is circular. That is, it can be visualized as rotation around the origin of the complex plane (where the real number line is horizontal and the imaginary number line is vertical).

From the problem above, a 314% interest rate is a growth rate of 3.14, or (approximately) . Plugging that rate into the formula, we get

which is Euler's identity. So, starting with $100, I ended up with -$100 (i.e., 100 * e^i.pi = 100 * -1 = -100). Not a great outcome! But suppose I leave my account open for another year. That is a rate of pi for two years, or 2pi. Plugging that rate into the formula, we get:

So starting with $100, I'll end up with $100 (i.e., 100 * e^i.2pi = 100 * 1 = 100). That is, I'll get my original money back. 2pi radians, of course, is 360° - the money has gone full circle.

So the best strategy is to borrow lots of money at an imaginary interest rate, wait until it becomes positive (a 180° rotation), and then withdraw it. -

Determinism, Reversibility, Decoherence and TransactionWith interest rates for savings where they are one might as well open an account with an imaginary rate. :worry: — jgill

:up: Though this can potentially be beneficial as I'll show in my next post... -

What is Dennett’s point against Strawson?"On the face of it, the study of human consciousness involves phenomena that seem to occupy something rather like another dimension: the private, subjective, ‘first-person’ dimension. Everybody agrees that this is where we start."

The phrase beginning ‘on the face of it...‘ is Daniel Dennett’s own statement of where the argument starts. So you’re saying you don’t agree with Dennett in that respect? — Wayfarer

Right, I don't agree with Dennett in that respect. I think there is only one world (or dimension) but thinking of it in Cartesian terms, whether as 'first-person' or as 'third-person', is a mistake. The latter can be characterized as a 'view from nowhere', which I think is untenable. Whereas the former fails to connect with the world at all, being radically private and subjective.

So if that philosophical distinction is rejected, both in whole and in part, then what are we left with? I think ordinary language serves us just fine here.

Grammatically, "Alice kicks the ball" and "The ball is kicked by Alice" both describe the same event, despite the subject and object being different in each sentence.

Similarly, Alice saying "My tooth hurts" and Bob saying, "Alice's tooth hurts" both describe Alice's toothache, despite them being first-person and third-person expressions.

Note how these grammatical distinctions don't divide up the world like the Cartesian distinctions do. Instead each statement above presupposes both a world being described (which includes toothaches) and a reference point in the world from which it is being described (Alice, or Bob, say). So the seemingly opposite (but actually interconnected) issues I raised above about "a view from nowhere" and "radical privacy and subjectivity" don't even arise.

See this as something akin to Bennett and Hacker's language criticisms in their "Philosophical Foundations of Neuroscience". If the assumptions that define a research program are flawed, then it's going to be difficult to solve some of the problems. -

What is Dennett’s point against Strawson?There's an awful lot of unclarity about what Dennett does and doesn't say, what he does and doesn't deny. That is why I included a lengthy quotation from him, as follows:

"On the face of it, the study of human consciousness involves phenomena that seem to occupy something rather like another dimension: the private, subjective, ‘first-person’ dimension. Everybody agrees that this is where we start."

I presume we all agree on that. — Wayfarer

I don't agree that that is where we start. That is the philosophical subject-object division that is often an unchallenged assumption in these discussions. Do you prefer ghosts (idealism), machines (eliminativism) or both (dualism)? Pick your poison. -

Determinism, Reversibility, Decoherence and TransactionUnderlying both DEs is the fundamental relationship: The instantaneous rate of change of something is proportional to the amount at that time. The first DE has the imaginary i in its "constant", and eiθ=cos(θ)+isin(θ)eiθ=cos(θ)+isin(θ) works its magic. — jgill

So I opened an account at the bank with $100 at an imaginary 314% interest rate. A year later, the bank claims I owe them $100! They say that if I keep my account open for another year, I'll get my $100 back. Should I trust them, or just pay the $100 and close the account?

Edit: The interest rate should be 314% (not 3.14%) -

Determinism, Reversibility, Decoherence and TransactionJust a clarification, it is not lost to the environment in the Copenhagen interpretation: it is simply deleted. — Kenosha Kid

Yes, good point.

Decoherence is the process of information loss to the environment, in which superpositions cannot be sustained by macroscopic objects because of the large number of degrees of freedom. When an electron is found at y, the contribution at y' is dissipated. Last time I checked, consensus was this is real but insufficient to account for apparent wavefunction collapse, although Penrose advocated this view at some point.

https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/qm-decoherence/#ConApp — Kenosha Kid

I'm not sure I follow your last sentence (and I read the SEP section). If, on measurement, the superposition state information is lost to the environment (apart from the measured value) then what else could be required for apparent collapse to have occurred?

They cannot determine from that state what the original state was. But an isolated observer can (in principle).

— Andrew M

This is specifically the Von Neumann-Wigner interpretation. — Kenosha Kid

Not specifically. This is just unitary QM. For example, MWI and RQM both agree with this prediction and are both referenced in the paper you linked:

The friend can even tell Wigner that she recorded a definite outcome (without revealing the result), yet Wigner and his friend’s respective descriptions remain unchanged (6). [Deutsch]

...

Another option is to give up observer independence completely by considering facts only relative to observers (24) [Rovelli] — Experimental test of local observer independence

Also the Zurek paper I linked specifically addresses the von Neumann-Wigner interpretation and states that retention of information suffices for collapse. (Which the paper treats as relative.)

The familiar ‘paradox’ of Wigner’s friend offers an interesting setting for this discussion. Wigner speculated [9] (following to some extent von Neumann [1]) that ‘collapse of the wavepacket’ may be ultimately precipitated by consciousness. The obvious question is, of course, ‘How conscious should the observer be?’

The answer suggested by our discussion is that—if the evidence of collapse is the irreversibility of the evolution that caused it—retention of the information suffices. Thus, there is no need for ‘consciousness’ (whatever that means): The record of the outcome is enough. On the other hand, the observer conscious of the outcome certainly retains its record, hence being conscious of the result suffices to preclude the reversal—to make the ‘collapse’ irreversible. Quantum Darwinism [11,25–34] traces the emergence of the objective classical reality to the proliferation of information throughout the environment. — Quantum reversibility is relative, or does a quantum measurement reset initial conditions? - Zurek

Anyway, point being that these various interpretations are not interchangeable. The docoherence picture of wavefunction collapse is at odds with Copenhagen, MWI, transactional QM, and Wigner's friend. Likewise Wigner's friend is at odds with Copenhagen, decoherence and transactional. — Kenosha Kid

Zurek is a decoherence guy and he agrees with the Wigner's friend predictions. You seem to be treating decoherence as objective.

Also I'm curious why you say Wigner's friend is at odds with transactional QM. Is it an objective collapse interpretation, like GRW? -

Determinism, Reversibility, Decoherence and TransactionIs making a measurement in QM and getting a specific result time reversible? How much of "time reversibility" might be artifacts of the mathematics that describe phenomena? — jgill

As you may know, unitary quantum mechanics conserves information. So given an arbitrary state for a system, any earlier state can be determined. In this sense, a system is reversible (i.e., inverse transformations can be applied to the system to restore the earlier state).

Where things get more complicated is when a measurement is taken. At that point, information is generally lost to the environment due to wavefunction collapse. However even then, the pre-measurement state can be determined by someone else isolated from that system and observer.

For example, consider a quantum coin that begins in a "heads" state and is transformed to a superposition of "heads" and "tails". Suppose an observer measures "tails". They cannot determine from that state what the original state was. But an isolated observer can (in principle).

This recent paper by Zurek (one of the pioneers of decoherence theory) provides the details:

I compare the role of the information in classical and quantum dynamics by examining the relation between information flows in measurements and the ability of observers to reverse evolutions. I show that in the Newtonian dynamics reversibility is unaffected by the observer’s retention of the information about the measurement outcome. By contrast—even though quantum dynamics is unitary, hence, reversible—reversing quantum evolution that led to a measurement becomes, in principle, impossible for an observer who keeps the record of its outcome. Thus, quantum irreversibility can result from the information gain rather than just its loss—rather than just an increase of the (von Neumann) entropy. Recording of the outcome of the measurement resets, in effect, initial conditions within the observer’s (branch of) the Universe. Nevertheless, I also show that the observer’s friend—an agent who knows what measurement was successfully carried out and can confirm that the observer knows the outcome but resists his curiosity and does not find out the result—can, in principle, undo the measurement. This relativity of quantum reversibility sheds new light on the origin of the arrow of time and elucidates the role of information in classical and quantum physics. Quantum discord appears as a natural measure of the extent to which dissemination of information about the outcome affects the ability to reverse the measurement. — Quantum reversibility is relative, or does a quantum measurement reset initial conditions? - Zurek -

What is Dennett’s point against Strawson?What I’d like to know is how, in Dennett’s model, there can be ‘an illlusion’ as an illusion is ‘ an instance of a wrong or misinterpreted perception of a sensory experience.’ What is it that is ‘wrong’ or ‘mistaken’, if not consciousness? What error does Dennett want to set straight in all his writings? — Wayfarer

The error is the "ghost in the machine" model of consciousness, with its presumptions of qualia, sense data, zombies and what not. To reject that model is not the same as rejecting consciousness, which has an ordinary usage independent of that model. -

What is Dennett’s point against Strawson?"No, we Deniers do not say this. We say that there isn’t any conscious experience in the sense that Strawson insists upon. We say consciousness seems (to many who reflect upon the point) to involve being “directly acquainted,” as Strawson puts it, with some fundamental properties (“qualia”), but this is an illusion, a philosopher’s illusion." - Dennett [bold mine] — Olivier5

Dennett's point is that Strawson has a mistaken model of conscious experience. Strawson then takes Dennett's denial of his model as being an instance of his model. But Strawson, and others who accept that model, are themselves subject to an illusion, since their model is mistaken. -

Is Logic Empirical?Then I think we may have reached a satisfactory point of agreement. — Dusty of Sky

:up:

And thanks for your comments throughout - it's been a good discussion. -

Is Logic Empirical?If we accept "consciousness causes collapse" but reject the many minds interpretation, then wouldn't we conclude that whatever is definitely the case for Wigner's friend is also definitely the case for Wigner? Once Wigner's friend performs a measurement and collapse occurs, the result he observes becomes definite for all potential observers even if they do not observe it themselves. Wigner doesn't know what his friend observed, but once his friend observes it, it is no longer in a superposition. — Dusty of Sky

Certainly that was Wigner's conclusion:

Wigner considers a superposition state for a human being to be absurd, as the friend could not have been in a state of "suspended animation"[1] before they answered the question. This view would need the quantum mechanical equations to be non-linear. It is Wigner's belief that the laws of physics must be modified when allowing conscious beings to be included. — Wigner's friend - Wikipedia

We could also reject both the many-worlds interpretation and "consciousness causes collapse" and hold that unattended measuring devices can also cause collapses which become definite for all potential observers, conscious and mechanical alike. Does that not work? — Dusty of Sky

As Wigner implies above, it doesn't work if you want to retain standard physics. Changing the physics leads to theories such as objective collapse and de Broglie-Bohm (which each introduce non-locality to make the standard predictions).

Note that Wigner still observes interference after the friend's measurement. So if the friend's result "becomes definite for all potential observers", then it is a hidden variable. That amounts to a rejection of locality, per Bell's Theorem.

Either way, definite parts of the universe (whether it's only one observer's universe or the universe for all observers) exist definitely and indefinite parts exist indefinitely. — Dusty of Sky

The way I would put it is that what is indefinite has the potential to be definite (for an observer).

I think we must posit that the indefinite parts are grounded in the definite parts. — Dusty of Sky

That seems right to me. Or, in alternative language, that the potential is grounded in the actual.

Note that I haven't argued that what exists depends on what does not exist (or exists indefinitely). I don't think that is true. I've only argued that part of the universe can be indefinite, or lack definite form, for a particular observer. It takes an interaction or measurement to actualize that potential, so to speak. -

Is Logic Empirical?This is the first I've heard of Wigner's friend, but I just read that the purpose of the thought experiment is to support the theory that consciousness causes collapse i.e. that everything is in a superposition until a conscious being observes it. But maybe I misunderstood what I read. Theoretically, it is possible that nothing exists definitely until it is observed. In that case, consciousness is necessary for existence. I'll call this theory quantum idealism. If something could be definite for one observer but indefinite for another, then perhaps a many worlds interpretation of quantum idealism would follow. Each consciousness exists in its own world. Where two conscious beings observe the same thing, their worlds converge and where they observe contrary things (e.g. I observe the cat is alive and you observe it's dead) their worlds diverge. Since Wigner's friend observes something definitely which remains indefinite for Wigner, the consciousness of Wigner's friend has diverged into two separate worlds, each with its own version of Wigner's friend. Until Wigner contacts his friend, it is undetermined which of the two divergent worlds Wigner's world will converge with. — Dusty of Sky

While Wigner held that "consciousness causes collapse", the thought experiment is independent of that interpretation. The key issue is that there can be two apparently incompatible reports - one by the friend who reports having measured a definite value (i.e., collapse has occurred) and another by Wigner who reports an indefinite value (i.e., collapse has not occurred). Those reports could be generated by unattended measuring devices, perhaps time stamped and read by someone at a later time.

That aside, your interpretation is a possible one, something like a many-minds interpretation.

I don't necessarily endorse either a many worlds or a single world version of quantum idealism, but I think this is one possible way to account for lengthy alternative histories existing in superposition without contradicting LEM. As long as reality bottoms out in definite facts, such as being x observes y, LEM remains in tact. Whatever is indefinite exists only relation to what is definite. The cat is only indefinitely alive or dead in relation to the definite fact that it is in the box. — Dusty of Sky

OK. But note that per the Wigner's Friend thought experiment above, that box can itself be in an indefinite state with respect to some further observer or measurement device. In this sense, such definite facts assume a measurement or decohered context.

It seems to me like the main difference between quantum and classical logic is that "a or b" in quantum logic means "a or b or it is indefinite whether a or b". So is the reason he sees quantum logic as more empirically significant that physical states of affairs can be indefinite? — Dusty of Sky

Yes. More precisely: per quantum theory, the world can be represented as a non-distributive lattice. So a logic that seamlessly captures that structure will also be non-distributive.

There are two separate claims there. The first is about the geometry of the world (analogous to whether spacetime is fundamentally curved or flat). The second is about the propositional logic that naturally applies to that geometry.

I see how this would make quantum disjunctions more useful to apply in certain contexts, but I don't think it makes the classical disjunction false. And if the classical disjunction is not inherently false, then neither is the principle of distributivity. And if I am right that reality bottoms out in something definite, then the classical disjunction applies to what is most fundamental. — Dusty of Sky

That is true for quantum logic as well. Any claim about the universe as a whole is definite since it's a claim about the whole geometrical space. Any claim in a measurement or decohered context is also definite (at least relative to that context) since, on measurement, an indefinite state collapses to a definite state.

The difference between a classical disjunction and a quantum disjunction only emerges in those cases where two orthogonal subspaces in a higher-level space (such as two orthogonal lines on a plane) don't exhaust all the possibilities. Which is to say, those situations characterized by indefinite states such as the dual-slit experiment or the quantum coin. -

Is Logic Empirical?Couldn't we say that the electron exists but no definite state of the electron exists and no definite number of photons exists? Saying no definite state exists just means that the state is indefinite. I see why it seems problematic that we can neither affirm nor deny that a photon exists. Could we perhaps resolve this problem by thinking of the photon's indefinite existence as a property of the electron. Existence is only existence as such when it is definite. If something exists indefinitely, it only exists as a property of something which exists definitely. For instance, the position of a particle in superposition exists indefinitely as a property of the particle, which exists definitely. — Dusty of Sky

The superposition can extend to the electron's existence as well. Consider Schrodinger's Cat where there can conceivably be lengthy alternative histories in superposition (and exhibiting interference). This also plays out in the Wigner's Friend thought experiment which describes a scenario where a system's state is definite for one observer (the friend) but indefinite for another observer (Wigner, for whom the friend is in superposition).

I'm not sure I understand this argument. Are you saying that giving up counterfactual definiteness also forces us to give up LEM? I've argued that this isn't the case because you can't meaningfully predicate something of a non-existent subject. LEM even applies to indefinite states of affairs because all states of affairs are either definite or indefinite. It just doesn't apply to particular determinations of indefinite states of affairs because no such determinations exist. — Dusty of Sky

I just meant that we can't assume that if the (unobserved) state of the quantum coin is not heads then it must be tails. A superposition of heads and tails is also a possible state. (And, in this single quantum coin flip example, is the state.)

You said, "what exists or not can be in a superposition". This strikes me as not only counterintuitive but inconceivable. If something does not exist, then it is nothing, and it can have no properties. Therefore, a thing can only have properties insofar as it exists. If it is indefinite whether a thing exists or not, then it is indefinite whether it has properties. — Dusty of Sky

OK. But be careful not to read "what exists or not can be in a superposition" as more than a mathematical description (e.g., a line somewhere on a plane that represents the probability of measuring the definite alternatives). It's just that quantum mechanics allows such a state, however that be conceived (which is supplied by the various quantum interpretations).

Hence the distributive law is wrong.

— Quantum logic is alive ∧ (it is true ∨ it is false) - Michael Dickson

If the disjunction symbol means what it means in classical logic, the distributive principle is correct. If it means what it means in quantum logic, it is incorrect. The disjunction symbol can mean whatever we want it to mean, so I don't think either application is fundamentally right or wrong. — Dusty of Sky

Dickson would agree that you can define logical connectives either way. But he argues that only (non-distributive) quantum logic has empirical significance, and thus relates to correct reasoning, since it derives from quantum theory. He discusses this further under "The Motivation" on p3. -

Is Logic Empirical?There's no law preventing us from thinking the words square circle, but we can't form a concept corresponding to these words.

— Dusty of Sky

Oddly, one can say the same about i - the root of negative one. Despite this, we make use of them. — Banno

i can be conceptualized as a quarter rotation on the complex plane. So, 1 * i * i = -1. As Gauss said:

That this subject [imaginary numbers] has hitherto been surrounded by mysterious obscurity, is to be attributed largely to an ill adapted notation. If, for example, +1, -1, and the square root of -1 had been called direct, inverse and lateral units, instead of positive, negative and imaginary (or even impossible), such an obscurity would have been out of the question. — Carl Friedrich Gauss -

Is Logic Empirical?Although the law of excluded middle may not be universal in as obvious a sense as the law of non-contradiction, I still think we can truthfully call it universal. Reality consists of things which exist, and as long as excluded middle applies to all things which exist, it applies to all things in reality. Therefore, it is universal. Since no definite position of the photon exists, the law of excluded middle does not apply to it. But the photon itself exists, so the law applies to the photon. For instance, it is either true or false that the photon has a definite position. — Dusty of Sky

Indefiniteness can apply to existence as well. An electron could be in a superposition of an excited state and ground state (having emitted a photon). In this case the number of photons (0 or 1) is in superposition. That is, what exists or not can be in superposition.

So the issue seems to boil down to definiteness and indefiniteness. In everyday experience, an unobserved flipped coin is definitely heads or tails and we don't have any trouble visualizing that scenario. We can describe the situation formally using the law of excluded middle (with observed anomalies, such as the coin landing on its edge, having straightforward explanations).

QM upends that intuitive picture. You can have a quantum coin which, when flipped twice and then observed, will always be found in the same state it started in (e.g., always heads). There is no straight-forward way to visualize that process without giving up counterfactual-definiteness. And so the LEM is no longer applicable in the obvious way.

Further, since a classical coin flip scenario depends on quantum decoherence, that suggests the LEM is contingent. That is, there is no logical requirement for quantum systems to decohere - a quantum system could conceivably remain coherent indefinitely (i.e., isolated and not interacting with other systems). The universe, taken as a whole, may be an example of such a system.

So there are at least two broad options available. One option is that there is a more fundamental logic (say, quantum logic) that applies universally with classical logic emerging as a special (or approximate) case that applies in decohered environments. A second option is that classical logic is universal, with indefiniteness being just a placeholder for what has not yet been satisfactorily explained in definite terms.

It doesn't seem that either option can be definitively ruled out at present. Michael Dickson discusses the first option in his paper:

The Fundamental Claim of QL. QL claims that quantum logic is the ‘true’ logic. It plays the role traditionally played by logic, the normative role of determining right-reasoning. Hence the distributive law is wrong. It is not wrong ‘for quantum systems’ or ‘in the context of physical theories’ or anything of the sort. It is just wrong, in the same way that ‘(p or q) implies p’ is wrong. It is a logical mistake, and any argument that relies on distributivity is not logically valid (unless, of course, distributivity has been established on other grounds). — Quantum logic is alive ∧ (it is true ∨ it is false) - Michael Dickson -

Is Logic Empirical?It seems that disjunction in quantum logic has a different meaning than in classical logic. In classical logic, A or B means either A is true or B is true. In quantum logic, A or B means either A is true or B is true or it is indefinite whether A or B is true. You pointed out that this indefiniteness is not merely epistemic (at least according to the Copenhagen interpretation). It might be epistemically indefinite i.e. uncertain, whether a coin landed on heads or tails, but we know that it actually did land on one or the other side. But in the case of the photon, it is metaphysically indeterminate whether it went through slit A1 or A2. Disjunction in quantum logic can express this state of metaphysical indeterminacy. — Dusty of Sky

Yes, that's right. But note Putnam's analogy with non-Euclidean geometry. Geodesic has a different meaning to straight line. However a geodesic on a flat surface is a straight line. Similarly, quantum disjunction has a different meaning to classical disjunction. However a quantum disjunction of measured quantities is a classical disjunction.

If P is indeterminate, then the proposition "A or not A" does not make sense, for the same reason that the proposition "the present king of France is bald or not bald" does not make sense. There is no present king of France, so it's neither quite correct to say he is bald nor that he is not bald. Likewise, there is no determinate outcome of P, so it is neither quite correct to say A obtains nor not A obtains. Neither example proves that the law of excluded middle has exceptions. All existing subjects either have or lack a given predicate, but if the subject does not exist, then it does not make sense to assert that the subject lacks the predicate. It does not make sense to assert that the present king of France lacks baldness because this implies that he has hair, which he does not because he doesn't exist. Likewise, it does not make sense to assert that the outcome of P is not A, because this implies that P has a determinate outcome. For a more concrete example of indeterminacy, take the statement "Bob will leave his house tomorrow". Assuming that Bob has free will and the future does not yet exist, it is undetermined whether he will leave his house tomorrow. So it is neither quite true to say that he will leave his house nor that he won't leave his house because both statements falsely imply that his future is already determined. — Dusty of Sky

Agreed. Along the same lines, consider Aristotle's future sea battle scenario:

One of the two propositions in such instances must be true and the other false, but we cannot say determinately that this or that is false, but must leave the alternative undecided. One may indeed be more likely to be true than the other, but it cannot be either actually true or actually false. It is therefore plain that it is not necessary that of an affirmation and a denial, one should be true and the other false. For in the case of that which exists potentially, but not actually, the rule which applies to that which exists actually does not hold good. — Aristotle, On Interpretation, §9

Aristotle's proposal was that the sea battle propositions had the potential to be true or false, but weren't actually true or false until the event occurred. Similarly, "the present King of France is bald" has the potential to be true or false, but isn't actually true or false without a present King of France. (In Peter Strawson's terminology, "the present King of France is wise" represents a presuppositional failure and therefore isn't truth-apt.)

So the same idea can be applied to QM. There is a potential answer to the question of which slit the photon goes through, but no actual (or definite) answer in the absence of a measurement. As physicist Asher Peres put it, "unperformed experiments have no results".

Just because classical disjunctions don't express indeterminacy doesn't mean that indeterminacy defies the laws of classical logic. We can still reason about indeterminate states of affairs using classical logic. For instance, we can conclude that, if A obtains, then P is not indeterminate.

So I don't think that we should think of quantum logic as a deeper form of logic and classical logic as merely a special case. It may be true that the physical world is fundamentally indeterminate, meaning that determinate processes such as coin flips are a special case in relation to the indeterminate subatomic processes which underlie them. And it does seem to be true that quantum logic is often more useful than classical logic when it comes to describing quantum phenomena. But this is only because quantum logic is specifically designed to express indeterminacy, not because classical logic is violated by indeterminacy. — Dusty of Sky

Yes, one approach here is to say that classical logic applies when things are definite, e.g., when a measurement has been performed, or the subject being predicated exists, or the contingent event has occurred. But it does not apply outside that context. So it's not that classical logic is violated by indeterminacy, it's that the preconditions for its use have not been met. Garbage in, garbage out.

In a similar way, Euclidean geometry is applicable when a surface is flat. We know that the angles of triangles will sum to 180°, the Pythagorean Theorem will hold, and so on. But it is not applicable (or needs to be applied in a different way) to curved surfaces. -

PlatonismIt is clear that if Alice is thinking it's going to rain, then we are entitled to say she's thinking something. What is not clear is how we should take the further claim that "there is something Alice is thinking". Andrew M claims that the something Alice is thinking is a convenient fiction, and he calls this fiction an "abstract entity" without committing in any way to its independent existence.

If Bob is also thinking it's going to rain, we can say anaphorically that Bob is thinking the same thing as Alice, and here the convenience of @Andrew M's fiction becomes more apparent, for we may wish to talk about what they're both thinking in more general terms: anyone thinking it's going to rain has reason to take an umbrella, or, thinking it's going to rain is a reason to take an umbrella.

That you can translate what an Aristotelian, like @Andrew M, says, or what someone who may have stronger nominalist inclinations says, into terms we might call Platonist -- that is not at issue. Of course you can. But what do you say to convince us that there are Propositions? That there are Relations? Where does @Andrew M's way of talking or mine come up short? — Srap Tasmaner

Well said again. Just a note to clarify the sense of convenient fiction there. The Aristotelian view is that the abstract depends on the concrete. So the convenient fiction is that we may consider an abstract entity as if it were an independent entity when it is not. But it doesn't imply that abstract entities are something that we (as human beings) have imagined or invented. That distinguishes Aristotle's immanent realism from Nominalism, for which shared features are dependent on language, naming, or minds.

Consider Russell's example which he uses to argue for Platonism:

Consider such a proposition as 'Edinburgh is north of London'. Here we have a relation between two places, and it seems plain that the relation subsists independently of our knowledge of it. When we come to know that Edinburgh is north of London, we come to know something which has to do only with Edinburgh and London: we do not cause the truth of the proposition by coming to know it, on the contrary we merely apprehend a fact which was there before we knew it. The part of the earth's surface where Edinburgh stands would be north of the part where London stands, even if there were no human being to know about north and south, and even if there were no minds at all in the universe. This is, of course, denied by many philosophers, either for Berkeley's reasons or for Kant's. But we have already considered these reasons, and decided that they are inadequate. We may therefore now assume it to be true that nothing mental is presupposed in the fact that Edinburgh is north of London. But this fact involves the relation 'north of', which is a universal; and it would be impossible for the whole fact to involve nothing mental if the relation 'north of', which is a constituent part of the fact, did involve anything mental. Hence we must admit that the relation, like the terms it relates, is not dependent upon thought, but belongs to the independent world which thought apprehends but does not create. — THE PROBLEMS OF PHILOSOPHY: CHAPTER IX. THE WORLD OF UNIVERSALS - Bertrand Russell

I agree with Russell here. But it doesn't further follow that there is any 'north-of' relation independent of a concrete context, e.g., a planet with poles. So that distinguishes Aristotelian realism from Platonic realism. -

Is Logic Empirical?Here is a geometrical proof-of-concept for quantum logic and how classical logic emerges as a special case in normal experience.

The quantum superposition state (psi) in the double-slit experiment (where A1 and A2 represent the photon going through each respective slit) is

psi = 1/sqrt(2)(A1 + A2)

where the probability of the photon being measured at either slit is the square of 1/sqrt(2), i.e. 1/2.

This can be geometrically represented by the following state space where the potentially definite states A1 and A2 are orthogonal axes of unit length, and psi is a 45° diagonal line of unit length (imagine the plus signs form a solid line to the origin).[*] Psi is essentially a North-East arrow which has a North component (A2) and an East component (A1).

A2 | | + psi | + | + +------------ A1

We can see here that the superposition state psi is not the same as either of the axis states A1 or A2. So, absent a measurement at the slits, the question of which slit the photon goes through has no definite answer (i.e., it's counterfactually indefinite). On a measurement at the slit, psi is projected (collapses) onto one of those axes, at which point the question of which slit the photon goes through becomes definite.

Now we can ask what is the smallest subspace that contains both axis lines. It is the 2D plane. The 2D plane is the span of the union of the two axis lines. However the plane contains any line that lies on it, and we can see that psi is another line on the plane.

So, in quantum logic, that span of the union is what is meant by disjunction. Intersection is what is meant by conjunction (in this case, the lines intersect only at the origin). The complement of a line is what is meant by negation (in this case, each line has multiple complements - every other line on the plane - which makes the logic non-distributive.)

Now, absent a measurement at the slits, if we ask whether the photon goes through slit A1 or A2, we can see that psi is contained in the span of the union of A1 and A2, so the answer is yes. That is, the disjunction itself is definite even though the question of which disjunct is true is indefinite.

There is a special case where psi may already be on one of the axes when it is measured. This is the case if a second detector is placed at the slits. If it is measured by the first detector as having gone through slit A1, then it will be measured by the second detector as having gone through slit A1 as well. The fact that no interference pattern is observed on the back screen just is a consequence of that. It's a consistent history, so to speak.

Which brings us to classical observations. Why, when an experiment is performed firing bullets instead of photons, and we don't measure which slits the bullets go through, is no interference pattern observed?

The reason, in effect, is that the measurement has already been done by the environment (termed decoherence). And the rest of what is observed follows consistently from the initial measurement. Thus what we are doing when we ordinarily observe something is to measure a value where psi has already been projected onto one of the axes. The worst case is that we don't know which axis it was initially projected onto, which is just a case of ordinary probability (e.g., whether a hidden coin is heads-up or tails-up). So, even absent our measurement, the disjuncts of which slit the bullet went through are definite. And that special case, which is always and everywhere observed except in quantum interference experiments, is the empirical and intuitive basis for classical disjunction.

So based on this state space geometry, quantum logic is the general case and classical logic is the special case (where states are definite and have unique complements).

See here for a helpful definition of quantum logic and the axioms.

--

[*] As a fun exercise for those who don't have degrees in this sort of thing, see if you can figure out where the 1/sqrt(2) comes from in the geometry.

Andrew M

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum