Comments

-

Ongoing Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus reading group.

Well I don't know, really, but I would like to explore that possibility, enjoy it even, I mean in logic it's all about possibilities, isn't it?

Huh, googling for the term, I came up with this:

https://ludwig.guru/s/enjoy+the+possibilities

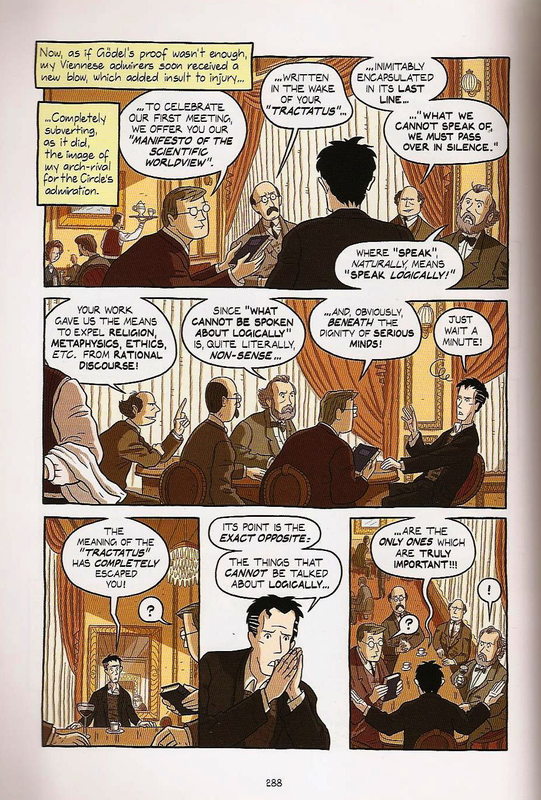

I see it like in Logicomix, I don't know if you know about it or read it, but you might enjoy it as I did.

-

Ongoing Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus reading group.My point was what I said above about what I think he was trying to do: to find a way to dissolve language, so that the inexpressible, the mystical like he says, or whatever this is, could either be expressed or show itself (6.522), to shine its way through, that is my take on Wittgenstein. But you know, we can be pretty harsh sometimes, cruel even, asking for trouble, mostly in cases where our love is involved, when it cannot be shown or appreciated, when someone or something stands in our way, and this is what I think happened to him, and why he was like this.

But we can see here, between us two I mean, how language can lead to the greatest misunderstandings.

-

Ongoing Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus reading group.haha, I doubt that he was, but then again, people say things about him. Anyway, that was not my point.

-

Ongoing Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus reading group.It may, or it may not, but certainly it is a possibility that we cannot dismiss. I mean, have you read about his life? A most troubled one, for sure, which I think shaped his philosophy, so I think we should see his work in tandem with his life, so that to understand better what he was on about.

In the wiki quotes, I read a statement of the physicist Freeman Dyson, mostly famous for the Dyson sphere, if you know about that, but anyway here it is:

Freeman Dyson, "What Can You Really Know?", The New York Review of Books (November 8, 2012)Finally, toward the end of my time in Cambridge, I ventured to speak to him. I told him I had enjoyed reading the Tractatus, and I asked him whether he still held the same views that he had expressed twenty-eight years earlier. He remained silent for a long time and then said, “Which newspaper do you represent?” I told him I was a student and not a journalist, but he never answered my question.

Wittgenstein’s response to me was humiliating, and his response to female students who tried to attend his lectures was even worse. If a woman appeared in the audience, he would remain standing silent until she left the room. I decided that he was a charlatan using outrageous behavior to attract attention. I hated him for his rudeness. Fifty years later, walking through a churchyard on the outskirts of Cambridge on a sunny morning in winter, I came by chance upon his tombstone, a massive block of stone lightly covered with fresh snow. On the stone was written the single word, “WITTGENSTEIN.” To my surprise, I found that the old hatred was gone, replaced by a deeper understanding. He was at peace, and I was at peace too, in the white silence. He was no longer an ill-tempered charlatan. He was a tortured soul, the last survivor of a family with a tragic history, living a lonely life among strangers, trying until the end to express the inexpressible. — Freeman Dyson

So this inexpressible might as well have been an expression of love and affection, something that appears easy, but apparently is not, as it has been obscured by language. And it might be that Wittgenstein's critique of language, and why he was so obsessed with it, was to expose this aspect, in order to arrive to the things that really matter the most in this world, feelings and love that is. -

Ongoing Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus reading group.Yes, but he doesn't make a matter of love only between him and Pinsent, but rather, in the motto above, includes everyone else, and whatever a man knows, with everything else being just rumbling. And if this is so, this makes the Tractatus, which is seen as an essay on logic and language, an essay on love, which carries the ethical weight that W mentioned to Ludwig von Ficker, that the point of the Tractatus was ethical.

-

Ongoing Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus reading group.But who was David Pinsent? Not much information on him, but the wiki page states:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/David_Pinsent

David Hume Pinsent (24 May 1891 – 8 May 1918) was a friend, collaborator and platonic lover of the Austrian philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein. Wittgenstein's Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus (1922) is dedicated to Pinsent's memory.

So could it be that these three words were "Ich liebe dich", "I love you"? -

Ongoing Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus reading group.Ok, first of all with the pre-preface:

Ludwig Wittgenstein

DEDICATED

TO THE MEMORY OF MY FRIEND

DAVID H. PINSENT

Mo t t o: . . . und alles, was man weiss, nicht bloss rauschen

und brausen gehört hat, lässt sich in drei Worten sagen.

Kürnberger.

“… and whatever a man knows, whatever is not mere rumbling and roaring that he has heard, can be said in three words.” Kürnberger

Who was this Kürnberger guy, and what are these three words Ludwig is referring to? -

Ongoing Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus reading group.Whenever you are ready, I guess. Although i am pretty tired now to start a proper conversation.

But I think you missed the preface, and even before the preface, not Russells comments but W's. Well, what do you have to say about that? -

Naming and Necessity, reading group?For sure? You are not just saying that to get me off your back, right?

-

Naming and Necessity, reading group?I tried to read N&N several times, but I always came to a stop, because of lack of meaning. I mean, what is the whole point of the book? Why is it important? Will I better myself reading and understanding it, or is it just a complete waste of time? I was unable to answer these questions, but then again people say it is important, yet I fail to see it. So, would anyone here care to explain its importance?

-

Ongoing Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus reading group.I could accompany you but as I am new, we would have to take it from the beginning. I studied and analysed the Tractatus, sentence by sentence, up to the start of chapter 3, so I could post all this here, but I have to translate it first since they are in greek! :)

-

Ongoing Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus reading group.hey, it says in the rules that bumps are not allowed!!

-

Metaphysics Lambda (Book 12)It's been a while since I studied Aristotle, and I don't have the time nor energy to go through it again, so I will answer by memory, whatever I remember, like I were on a desert island with no access to resources.

So he says that there are four causes, if I remember him correctly, efficient, formal, final and one more I think, which eludes me. When he discuses unmoved movers, he says that they are final causes, not efficient nor formal or whatsoever, probably owing to the fact that they are immaterial. But objects in the physical world that consist of matter, they ... are all four causes, I think he uses the example of a sculptor that makes a statue to explain better what he means. So I don't see a contradiction there, but one can say that he makes arbitrary and unsolicited distinctions, which is a different thing. -

Metaphysics Lambda (Book 12)1. It is not our fault that Aristotle makes a distinction between the two, the immaterial/material I mean, but I don't see it as trickery. Apart from that, I agree with Πετροκότσυφας. And I think that A introduces the concept of unmoved movers out of necessity, logical necessity that is, that there has to be such entities, if motion in the world can be explained at all. He arrived there to avoid circular argumentation, as has already been said, but then again objects affected by the unmoved movers move in circular motion, so it seems that the circle has been transferred from the logical and the metaphysical to the physical.

2. Duly noted. -

Metaphysics Lambda (Book 12)

Yeah, you are probably right that they are not self caused.

Huh, the unmoved movers always troubled me! -

Metaphysics Lambda (Book 12)Well first of all, to say that I dont really know how or what creates motion, we are just discussing here Aristotle's philosophy on the matter, to see what he was blabbering about.

Now, I think unmoved movers would have to be full actuality, having capitalized on and exploited their potential in full, so that to become or rather be actual. Like someone who aspires to become a pilot, but isn't yet, well when he becomes, we can say that he actualized his potential, so that he is now an actual pilot instead of a potential one, with potentiality having been stripped away from him and turned into actuality. The idea that moved him in the first place was that of a pilot, so this was his unmoved mover, forever immovable, static and speechless, but nevertheless inspired him to move accordingly. So this is how motion in the physical world is created. -

Metaphysics Lambda (Book 12)I think that Aristotle takes unmoved movers to be immaterial by definition. So they are not affected by motion in the material plane, and are thus immovable in that sense. They do however cause motion by thought, intellect, love and inspiration, beings in the material world doing that towards them, so they are movers. As for their causes, i think we can say they are their own cause, causa sui, how is it called. All this might be wrong and totally unfounded, but i dont see how it is contradictory.

-

Metaphysics Lambda (Book 12)It matters because motion, according to Aristotle, happens only in, say, the material universe, not the immaterial one.

-

Metaphysics Lambda (Book 12)Hold on, aren't unmoved movers supposed to be immaterial in nature?

-

The measure problemIf mathematicians were like philosophers, trying to fully resolve an issue before advancing, then there would be no progress in mathematics. So, wherever there is doubt, they create an axiom and tell their colleagues to invoke it in their work, if and when they like. In this way, they avoid the search for truth, so that to focus solely on mathematical work, numbers and proof: they just need to say which axioms were used, and leave the 'what really is the case' to philosophers. Mathematical axioms, in the way they are used by mathematicians, do not have anything to do with 'truth' in the real sense, they are just there to help them in their games. After all, if something was obviously true and accepted by everyone, we wouldn't have an axiom for it, would we? :)

-

The measure problemIt is the constructivist/finitistic approach to maths MO is supporting. But because there is not universal concensus in mathematical and philosophical communities alike, in maths we have axioms for this stuff, like the axiom of infinity or the axiom of choice.

-

Science is inherently atheisticIs this in contrast to Ancient Science, where belief in deities was common? Or else, when was science, modern or otherwise, ever concerned with deities?

Pussycat

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum