Comments

-

Squeezing God into Science - a sideways interpretationA god, or logos, some kind of transcendent spirit is wanted. When one contemplates the immense complexity going on in 1 cell, never mind the biosphere and the universe, it seems to many of us just too damned complex to have happened without guidance. This isn't a scientific reaction, of course. On an intellectual level, I'll say "Yes, life did self-assemble, but it had a very long time to work out the details. Life has self-assembled on many planets in the universe. Matter can self-assemble into more complex forms, and it does--inorganically as well as organically. Mind is not beyond the capability of matter." On an emotional level, given the faith I received as a child, a God-directed biosphere and universe beyond is preferred.

That's where the tension comes in: Does one go with the intellectual approach of science, or the intellectual approach of religion? I don't hold them irreconcilable; we can accept that God was the primum mobile -- the first mover. But combining scientific and religious thinking doesn't resolve the tension entirely, because "how God was the first mover" still has to be resolved.

We've been stewing over this pot for a long time. -

How do those of you who do not believe in an afterlife face death?Death is certainly closer for me than it used to be -- I'm 71. I'm not afraid of death, I just don't want to be there when it happens. (full disclosure: Woody Allen joke)

I don't really expect anything to follow death, and if one is lucky the process of dying will proceed speedily, and one will soon be unconscious, then more deeply unresponsive, till the heart and breathing stops. Of course, death may not be in a hurry, in which case one will suffer during the dilly dallying around.

"How We Die" by Dr. Sherwin Nuland is a cause-by-cause explanation of how death comes about. It was published in 1994. You can read it for free here.

There is also an interview with Dr. Nuland here. In the interview he was saying that many people say

"Anything is better than death.

Well, you know, that's not true. It's not true that anything is better than death. As a wise oncology nurse said to me, there are many people, more than you would dream, and many of our listeners I think probably fall into this category, for whom what you have to go through in order to come out on the other side alive is simply not worth the effort." — Dr. Nuland

Nulland died in 2014.

My husband of 30 years died a slow death from cancer; it was quite painful, and the initial surgery was quite disfiguring (it was a very aggressive cancer in the lymphatic system in the jaw). He felt well for a while after the surgery, radiation and tough chemo. It was all for naught -- the cancer had already spread to the bones of the neck, and eventually into the brain. He spent 4+ months in hospice, needing total care. He could speak, and breath, but had little control over his arms and none over his legs. Swallowing was a problem. His care was excellent; he was as comfortable as one could be. He was alert and talkative. About 3 weeks before his death he started a visible decline -- less alert, less conscious, less interest, then unconsciousness, and finally death. It was 1 year, first symptom to death. -

A Sketch of the PresentStill, one might think that a political party (after a rough start) could actually swell by delivering on its promises to tax the rich. — n0 0ne

They did in the early 1900s -- the Progressives were fed up with graft and corruption. They elected reformers to the presidency (Theadore Roosevelt), progressives to congress, governorships, and the state legislatures. Milwaukee had 3 socialist mayors, one serving from 1916 to 1940. That one, Daniel Hoan, was considered the best, most effective mayor Milwaukee had. Farmers formed the Nonpartisan League in the upper midwest to fight for a fairer deal for agriculture; women won the vote, prohibition was instituted, and an income tax was instituted, to replace the revenue the government had received from taxes on alcohol. The trusts were attacked; Standard Oil was was broken up; so were the railroad trusts, and some others.

WWII happened in the middle of all this, as did the Russian Revolution in 1917. The RR of 1917 started a "red scare" which along with the KKK set back some reform elements, such as labor and civil rights reformers.

The Great Depression decade saw a resurgence of labor organizing, communist agitation in many social justice areas, and of course things like Social Security, Unemployment Insurance, and other New Deal programs. Then WWII, and an economic boom which benefitted many working class people. But, the good times couldn't last, and Republican--who by Reagan had migrated considerably towards a more extreme conservative position--started lowering tax rates on the rich while wasting a lot of money on the fucking Star Wars Initiative -- a trillion dollar boondoggle. (Before Vietnam, the US was pretty much out of debt.) Now were in very deep doo doo.

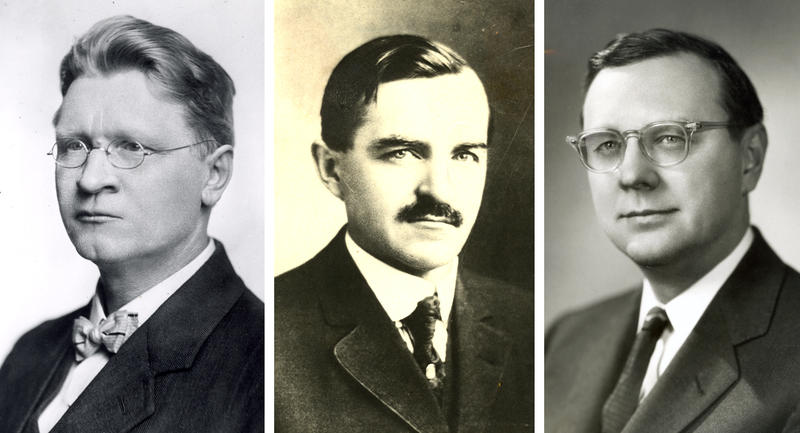

The socialist mayors of Milwaukee. See, no horns!

-

Squeezing God into Science - a sideways interpretationYou are (of course) not the first person to assign God the task of supervising the atoms so that they eventually become the Acme, Zenith, and Crown of creation.

The question of where God stands with respect to Creation is unsettled; some people want to do what you propose; some people want God to be apart from matter, but altogether sovereign over it. Some place God outside of nature altogether, and then quite a few just eliminate God's position altogether.

It seems to me that the mainline Judeo-Christian approach is the second one: God isn't "in" nature (no tree-dwelling for God), God is sovereign over matter -- all matter -- over the whole universe, God being its sovereign creator. The writer of the Genesis story didn't have this concept at hand, but just as God hovered over the face of the deep, you are proposing that God also hovered over the hot vent at the bottom of the deep and willed atoms and molecules to bind together in the desired way, over time.

During the 6 days of creation God repeated His benediction on creation "and it was good". What God makes IS good.

Oddly enough, some fundamentalists / evangelicals / pro-apocalypsists are quite indifferent to the "good creation". To them all that matters is Jesus and heaven. Whatever happens to the world--to nature, creation--is irrelevant. Polluted, creatures going extinct left and right, dead oceans, filthy rivers -- It's all going to go down the drain anyway when Jesus pulls the chain and flushes all the sinners down the sewer into hell.

It seems to me that the mainline Judeo-Christian view is the best one for Western civilization. It yokes us with responsibility to care for and about the world--not just humans, but all of creation. Humans - eastern, western, northern, and southern - are too short-sighted to leave us to our own devices. We all need some kind of prompt to take care of our only world. -

A Sketch of the PresentBut what triggered or allowed these changes in tax law? — n0 0ne

Two things. #1, pressure from wealthy individuals and businesses. How do wealthy people pressure congress? They underwrite their campaign costs, they give them gifts (under the table), they supply congressmen's staff with texts for tax bills with all the details worked out, and so forth. They also threaten congressmen with a loss of the goodies, or that they will move a plant out of their district, or will invest somewhere else--and that they will make it clear the congressman was responsible.

#2. Political parties are sometimes swayed by seductive economic theory, like supply-side economics, and trickle down economics. Lowering taxes on the rich will produce a wave of new investment which will benefit everyone. The economic benefits given to the rich trickle down to everyone. Win win. The trouble is that these schemes do not always work. Once in a while they do, but lower taxes on the rich too much while increasing spending is a sure-fire way to increase the annual deficit and the national debt.

Look, the masses only need to be appeased enough to keep them from rioting. The rich have to be pleased and be given plenty of real treasure, not just bread crumbs which the poor get. Since the wealthiest 1% control so much of the wealth, they are in a very real position to punish congressmen who get in the way. -

A Sketch of the PresentYes, the US could possibly reduce defense budget to 2-2.5%. My only question is why US military is not tens of years ahead of everyone else already... — Agustino

Because defense spending has followed a pattern first pioneered by the railroads back in the late 19th century. A handful of extremely avaricious railroad entrepreneurs (aka thieves) lobbied congress to build, and over build, railroads through the largely empty great plains to the economically small west coast -- the "transcontinental railroads". They were mostly a complete economic failure.

The failed because there was little demand for the transportation the several transcontinental roads offered. Once the railroads imported a few million European settlers into North Dakota to Kansas, the Missouri river to the Rockies, they produced a glut of agricultural products that exceeded the demand, depressing the ag market they depending on. Similarly, the silver mines opened near the railroads in the SW exceeded the demand for silver. The real purpose of the railroads was to get cash from the government for the "entrepreneurs".

Transcontinental railroads would have been needed anyway, just 30 to 50 years later.

President Eisenhower warned the American people of the Military Industrial Complex in his farewell address. His advice was ignored. Industry would use the military to milk procurement budgets, and the military would use industry to accumulate cargo that enhanced their sense of power, but generally didn't work all that well.

We have had repeated rounds of procurement in major weapons systems that just didn't deliver performance. Compare the B52 with numerous high tech bomber and fighter systems. The B52 has been flying for 60 years and still works well. The fighters sometimes show up dead on arrival. Too complicated, not reliable, waaaay too expensive, difficult to repair and service, crash-prone, etc.

Granted, not everything the military and industry work together on turns to shit. The nuclear arsenal seems to be very reliable. The AWACS have turned out well. We have a number of systems that are quite good, and quite a few that are so-so.

The corporations and military leaders got what they wanted the same way the railroad thieves got what they wanted. They descended on congressmen en masse, out maneuvered the objectors, a bribe or two here, a very generous donation there, maybe a junket onboard a bomber or submarine... you get the picture. Heavy duty lobbying. -

A Sketch of the PresentWhy doesn't the poor majority just tax the rich and take it wants legally? Because they identify themselves and their position in their private hierarchies in terms of culture, religion, race, etc., as much as they do via class. — n0 0ne

Actually, they did do that. While the US, like every other society, has always had hierarchies and inequality of wealth, there were two episodes of extreme inequality -- the Gilded Age (so named by Mark Twain) anding in the early 20th century, and the person time, which started around 1975 (give or take a few years). What was it that allowed these things to happen?

Mostly governmental policy. A huge amount of money was made in the dominate industry of the 19th century -- railroads -- and it was mostly made by government grants to the railroads, which were then milked for cash. Plus, there was no income tax at the time. That came about in 1920. By then a reform period had cooled off the railroad/iron/steel industries.

What triggered the second, current feeding frenzy by the rich (making them super richer) were changes in tax law, allowing them to keep and shelter much more wealth. (There were also some new digital industries which made a lot of people quite rich).

Outside of these two episodes, the ratio between the highest paid executive and the average worker in a company was stable and not absurdly exaggerated. -

Predetermined ExistanceThe view that everything is determined is not assailable, because one can say that whatever happens was determined. You think you have free will? No. You just intend to do what you are compelled by physics and chemistry to do.

I don't agree with that view; I take a "some things are freely chosen, some things are determined" approach. This solution has problems too, because I can't aways distinguish between what I chose freely and what I didn't.

Chance plays a role in life. The baby fell out of the 10th floor window when there happened to be a very strong up-draft on that side of the building, he bounced off an awning, and then landed on very thick grass planted on very soft dirt. Otherwise, S P L A T. Maybe the fellow who survived the crash was cushioned by the other victims -- who the hell knows. In any case, chance can't be counted on. Drive carefully.

The context into which we are born makes a great deal of difference. I was born in a working class family in a small town in rural Minnesota. Had I been born in New York City (everything else being equal) my life would likely have taken a different course.

Michelangelo was a genius coupled with great creativity coupled with a culture interested in his work of creative genius and also happens to be willing to support the guy. Had Michelangelo been born in Patterson, New Jersey in 1975, the same result would not have happened.

Beethoven was not born in a musical vacuum. He studied briefly with Haydn and other composers. He was deeply immersed in a culturally rich milieu. Were he born in south Chicago -- much different outcome. -

A Sketch of the PresentWhy — Cavacava

Why all this defense spending? Obviously, there is the self-perpetuating military-industrial complex which lobbies hard to keep all sorts of contracts flowing. Then there is the money we spend to do something on behalf of other people. What we do for the Europeans is presumably clear, what we are doing for the Iraqis and Afghanis is exceedingly unclear (at least to me). Plus there is the task of patrolling the open seas so that wicked nations like China or Russia don't decide to assert their self-interests. Then we need to be ready to totally destroy either the armed might of, or the mere existence of the North Korean state.

This from 1953

-

Why Can't the Universe be Contracting?Damned if I know what's going on with the universe. But...

No one can "see" the universe in its entirety -- we are part of it, of course, or at least I hope we are -- and it exceeds our farthest reach of vision. Perhaps (or probably) some galaxies are already invisible to us, and will never be visible in the future.

The universe is a model, not a photograph.

Does the background microwave radiation help you at all? It appears to be everywhere, not evenly spread out. How would the big bang be consistent with a universe that was NOT expanding? How could something be "in the center"?

What is the relationship between a black hole and the space around and in it? Does it have space within it? -

A Sketch of the PresentYou did an admirable job of rounding up and corralling a herd of connected phenomena (aka, problems) in your OP.

Solutions? Well, sure -- we could have a revolution of just the right kind, perfectly targeted, splendidly executed, and then eased to an end before it ran amok. Fat chance. Fat chance of gradualist solutions too. Are we at an End Game--not where the world comes to an end, but where the world order can not be extended further; gradually decays; power systems (of all sorts) fall apart, and then... we can start over (and maybe end up where we are now, only 500 - 1500 years hence)?

I thought your OP also elicited some very thoughtful responses too.

From my personal perspective, 1973 (the year of the Arab oil boycott) was the year the economic season turned from summer to autumn. For most of the 1970s and early 1980s I, single and frugal, was able to afford a modest standard of living, and save money. Over the years since, it has taken more income to produce the same, or somewhat reduced, effect. Thirty years of two incomes helped us a great deal. Without pooling resources in a relationship, neither of us would have been able to prevent a steeper decline in what were modest expectations.

I see the same situation in many, many other working class people. They have worked steadily; they raised families; they led sober lives. As they now reach their 60s, they find themselves in a quite worrisome situation where retirement is in sight (say, in a decade) but they do not have sufficient resources to quit working. They didn't gamble, drink, drug, or piss away their security. They simply never made enough income.

Their parents were luckier. They were able to save, pay off their mortgages, and as they die off, can leave some resources for their children, but not enough to grant them security in their old age. The grandchildren of the lucky generation are probably going to be in debt for the rest of their lives.

Granted, there are working class people who are better off, will get a pension -- especially if they worked for government agencies at everything from teaching to road maintenance -- but they are nothing close to a majority. -

'Beautiful Illusions'Rather than resign your membership, why don't you try simplifying the language of your posts? Some things you might try:

Get acquainted with the period (.). Your OP has 140 words in one sentence. That's a good length for a paragraph. It's about 10 times too long for one sentence.

Write short sentences which have one subject and one verb. (Right, that's a bad practice as a habit, but you would benefit from practicing writing short sentences.) "See Spot run. Look Dick, I have two big balls. Jane is a bitch." Of course you don't want to write like that all the time. For God's sake (he has to read that stuff too) improve your writing!

Use short words whenever possible. Prefer Anglo-Saxon words over words borrowed or coined from Greek, Latin, and French. Some examples of longer, less common words: conducive, [leads to] conversely [opposite], corresponding [matching], disillusionment... Use more common words instead of less common words. (Google Ngram can tell you how common a word is.)

Sure, most people here are well educated. But want to know a secret? Even educated people prefer to read easier text than harder text.

Use proper grammatical construction--no sentence fragments, no run on sentences. Limit the number of clauses within a sentence

Simplify, simplify, simplify.

Here, look at this sentence (It's yours). How could it be made simpler, easier to read, and easier to understand?

"Wonder why it unfortunately tends to be the case that the more benign an individual’s personal situation the typically more conducive it then tends to be towards encouraging a naive and illusory concept of reality within them - " 37 words

Start with a subject. That would be you.

"I wonder why more benign situations tend to encourage a naive concept of reality in people. 16

Less than half as long. You seem to want to say everything in 1 sentence. It's OK in America to use several sentences to convey a thought. Yes, it's unfortunate; yes, it's both naive and illusory.

I used to write like you. A college teacher was handing tests back and said that I should be writing for the IRS (not a compliment). Another teacher told me to get acquainted with the semicolon. I liked writing that way. But later on, (25 years later) I finally figured out how to write simply. It's not painful to leave all that verbiage behind. -

Artificial intelligence...a layman's approach.The brain's architecture surely has something to do with the way our minds are. — TheMadFool

Yes, it does. Quite a bit, I would think. There's the left brain/right brain, then there are the lobes. Then there the sulci and gyri -- hills and valleys of the brain surface, and the layers of the brain--the reptile brain stem, the older limbic system, and then the cerebral layer. There are gray cells and white cells, and so on.

Once the brain is presented with sensory input, it starts rewiring itself to process and make sense of what it receives. This rewiring goes on throughout life. In order to have a new memory, the interior of neurons and the exterior structures of neurons have to change. Memories are linked by reaching out and touching other neurons. This is a self-managing system. We don't have to receive instructions from outside to connect and disconnect, alter neuronal states, and so on.

There are more connections possible among the neurons of the brain than there are stars in the universe. Or maybe atoms in the universe. (It's a BIG number.)

You may not like the way humans have managed their world. Actually, lots of people don't like it. However, people can readily perceive a difference between a junked environment and one that is quite pristine, and they prefer the pristine (unless they are in the property development business, then pristine is a bad thing -- unused resources). The rich English and other brits who bought land in North America viewed the land as a waste -- it had not been "improved". So they set about "improving" it, and the "improvements" continue on.

There's no certainty AT ALL that a digitized intelligence would do any better with the natural world than we have. You are assuming that your AI would be god like. It might be more fiend like. -

Confined Love AnalysisGood is not good, unless

A thousand it possess,

But doth waste with greediness. — Anonymys

Donne can spread a coverlet of ambiguity over his poems' presumed meaning. Is it the case that "Good is not good unless a thousand it possess, but doth waste with greediness..." ? Is having only one good woman not enough? Must one have a thousand women, and waste them with greediness?

Some man unworthy to be possessor

Of old or new love, himself being false or weak,

Thought his pain and shame would be lesser,

If on womankind he might his anger wreak ;

And thence a law did grow,

One might but one man know ;

But are other creatures so? — Anonymys

Let me rearrange this to make the point clearer:

Some men who are false or weak, and are unworthy to possess old or new love, decided they could lessen their suffering by displacing their pain, anger, and shame onto women, and making it a rule that women were stuck with one man only. Enforced monogamy is the strategy of losers.

If ships are male (going out into the world...) and houses are female (receiving the world), isn't Donne saying that men and women should both be free to love who all they will?

But we are made worse than those. — Anonymys

Are we as free and easy as the birds? OR are we affected in negative ways (made worse) by behaving like birds and beasts?

I conducted my sex life promiscuously until age snowed white hair on me. Then I became a good man to my husband and strayed no more. (After a certain point, it gets to be just too much trouble.)

Are women naturally faithful? Not according to this familiar Donne poem: (There are formatting codes buried in the text that I can't get rid of.)

GO and catch a falling star, Get with child a mandrake root, Tell me where all past hours are, Or who cleft the Devil’s foot; Teach me to hear mermaids singing, Or to keep off envy’s stinging, Or find What wind Serves to advance an honest mind. If thou be’st born to strange sights, Things invisible go see, Ride ten thousand days and nights, Till age snow white hairs on thee. Thou at thy return wilt tell me All strange wonders that befell thee, And swear, Nowhere Lives a woman true and fair. If thou find’st one, let me know, Such a pilgrimage were sweet; [i][b]Yet do not, I would not go Though at next door we should meet. Though she were true when you met her, And last till you write your letter, Yet she Will be False, ere I come, to two or three.[/b][/i]

Don't bother telling me you found a faithful woman, because before you came from next door to tell me, she would be unfaithful to two or three. What we don't know is whether our infidelity is an "is" or an "ought". -

Why do we like dreaming?What is satisfying about a good dream? Why do we like getting lost in a story?

...What Is it about these experiences that makes us want them? — Crane

We like narratives. We like stories that unfold and have surprises. Dreams sometimes are organized narratives, of a sort, which is pleasant, provided the story is pleasant. -

Power and equalityFirst of all I do not believe they create structures that are convenient. I believe the power structures are already in place. — Jeroen Roelfs

That is certainly true in many cases. A new pope steps into a very old, rigid power structure. Most prime ministers step into structures and roles that are in place. Even if someone is not elected -- say, a top level adviser or aide-de-camp, there are usually clear limits to what they can get away with, unless they engage in illegal activities which sometimes happens.

But in some cases, one has to get power first then build up a structure to exercise it. This was true in the 1917 revolution, wasn't it? It was true in the American Revolution, too. Apple, Microsoft, Exxon (formerly Standard Oil) Google, Facebook, etc. all had to erect new structures. The corporate template was in place, but the enterprise and its structure -- the part that produced the cash and then the power, wasn't.

Criminal enterprises usually have to create structure from scratch -- there is no template for criminal cabals.

We might be debating a small point, not sure -- which comes first, the structure or the power. The bigger question is who gets their hands on the levers of power and what do they do with it. -

Power and equalityYou know it was very close -- Clinton won the popular vote, but Trump luckily won the electoral college, which "trumps" the popular vote. Clinton should have polled better than she did in November. Comey's late announcement that the investigation into her e-mails was resuming (or something to that effect -- maybe hadn't ended...) was either deliberate sabotage or it was the result of tone-deaf advice. I suspect the former. Had she campaigned more in Wisconsin... but who knows.

I will admit that Trumps insouciant irreverence for good form has an appeal which I feel too. Bernie Sanders had a similar 'outsider' appeal. The overwhelming earnestness is stultifying. -

Power and equalityI'm going to disobey the rule and judge your book by its cover.

Do people get power from a structure (here a pyramid of power) or do people who have power organize structures for their convenience? I think the latter.

Power doesn't exist as a disembodied force. It has to be produced, and the usual way of getting power is to gather material force (guns, votes, cash, etc.) through exploitation. Donald Trump exploited two resources to win election: cash (of which he had quite a bit to spend) and the discontent of many people (they were/are discontented by their collective situation in life). Hillary Clinton exploited the same resources.

Adolf Hitler exploited the dire post-WWI economic circumstances of Germany, the fairly deep well of anti-semitism, working class insecurity, the usual and customary greed of the bourgeoisie, and resentment towards the WWI settlement to gain power. He also had cash and brutality on hand. The Sturmabteilung and the Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei aided his acquisition of power.

His power rested on three things: loyalty purchased with better economic conditions and repudiation of the Versailles Treaty, fear of punishment (through the good offices of the Gestapo, et al) and yes, charisma.

Hitler isn't an outlier. A lot of powerful leaders are at the top of the pyramid because they used the same methods as Adolf to get there. -

Should Capitalizing Your Name or the Word "I" be a Choice?People think that "unique spellings of ordinary names" will give their children something "special". So Jane is twisted into Jaynne; Mary is converted to Marrree, and so on. Words not normally used as names are pressed into service: colt, willow, sunshine, and so on. People make up names: Toyletoisha, and such nonsense. Names that sound great for infants, like Bambi, are a liability for adults. What these names do for children is signal that their parents were morons.

Some people think that an uncapitalized name will be nifty. john, don, ron, and quan. What this does is just increase social friction.

Spelling, capitalization, punctuation, and grammatical rules exist for everyone's convenience. These rules reduce confusion and misunderstanding and increase clarity. The more people adhere to these rules, the better.

Take any radical political position you want, publish it abroad, give mob-rallying speeches in support of it, but stick to the rules of the language.

Am I suggesting we "freeze" the language? No. Changes will occur over time. New words are added, old words fall into disuse; which words are preferred change. "Negro" is no longer preferred. "People of color" is preferred over "colored people". "Due to" as opposed to "as a result of" or "owing to" has been in disrepute in some circles for decades.

Informal language is where changes begin, then migrate into formal language. Spelling and capitalization rules are, though, quite conservative. We don't spell "night" as "nite". Some people would like things spelled that way -- brite (not bright), rite (not right) and thru (not through), for example. They are not making much progress, merciful God.

An aspect of language that changes the most is pronunciation. For instance, in the eastern Great Lakes region, the word "block", pronounced with an open soft 'a', is shifting to a pronunciation that sounds closer to "black". (This has been observed over the last 30 years, or so.)

the question had been reignited in my head. — XanderTheGrey

Fire in the brain can be a problem. I hope the smoke detector in your skull is working. -

Unconditional love does not exist; so why is it so popular?I think you are playing word games--the delight of getting people to agree that something unconditional must have conditions. It's an empty exercise.

We know what conditional love is: I will love you IF you obey -- otherwise, not. I will love you IF you make me proud of you -- otherwise, not. and so on. Some people have quite conditional love for their own children, spouses, parents, etc.

Unconditional love is possible: It means that someone loves you--period. God's love is said to be unconditional--Agape. Other kinds of love - storge, eros, filio - could be, but probably are not often unconditional because they arise from fraught motivation -- getting turned on sexually, being related to somebody by blood, and so on.

Practitioners of Carl Rogers' therapy try to offer their clients "unconditional positive regard", which means they ALWAYS have the client's self-definition of their own good as their goal. They don't have a view of their own about what is good for the client.

Difficult to deliver? Absolutely. Unconditional love is the bread of heaven, not our run of the mill product. We are bid to try. -

Does any form of Supremacism "actually" exist?If supremacism did actually existed, then there should be a very strong brotherhood between the people of the so-called 'supreme group'. However, evidence is say that this is not the case. — PEU

Hmmm, I don't know about that. Didn't the Nazi's in Germany hang together pretty well? Also the fascists in Japan? The KKK (ku klux klan) is derived from the Greek kuklos or ‘circle’ plus clan. Their fellowship seems to have been pretty solid. Especially now that they are pariahs, they find each other's company even cozier. -

Does any form of Supremacism "actually" exist?There as many types as drops in the ocean with enumerable gradations. — Rich

So many different kinds? There are only two kinds of people: Those who think everybody is different (with innumerable gradations) and those who think that everybody is pretty much alike. You belong to the former group, I to the latter group.

Is this what you meant by enumerable - "able to be counted by one-to-one correspondence with the set of all positive integers"? Did you mean "innumerable" or "enumerable"? If I ever knew "enumerable" I'd totally forgotten it. I probably never knew it. -

Anyone on disability on here?if you are implying that the fact he was blind caused him to give a lesser service to the customers you would be wrong. — Jeremiah

Of course I was implying no such thing. I was making a joke along the lines of "You'd have to be blind not to see what was going on..."

My comment was aimed at Wells Fargo (and their various fraud problems) not the blind. It would just seem that at Wells Fargo, there must have been someone with very little vision keeping an eye on the bosses -- which is where their fraud originated.

If you are implying that I am prejudiced against handicapped people, you would be wrong. -

Artificial intelligence...a layman's approach.Dehumanization — Rich

I think the Nazis killed over 50 million people - with advanced technology. — Rich

Maybe they did; it depends how one counts up the total--it could be fewer or more than 50 million. But the point I wanted to insert here is that their technology was ordinary; their organization and murderous will were advanced. Their planes, bombs, guns, bullets, tanks, and gas chambers weren't high tech--at least any more high tech than was available to the allies. In the Soviet Union, they killed Jews by lining them up in front of ditches and shooting them -- not exactly high tech. They killed their Soviet POWs by putting them in fenced in corrals and just leaving them in the open without food or water. Again, not high tech. What the Nazis had in abundance, though, was a highly focused murderous will.

The Nazis (and Japanese) developed dehumanization to a high level, by taking the approach you earlier identified -- just not caring what happened to people. The Jews (and others) were referenced as "useless eaters".

The few pieces of high tech in WWII were RADAR, the automated bomb site, and the atom bomb. Ballistic missiles didn't play a huge role in the war. They were too late. So was the jet engine. -

Artificial intelligence...a layman's approach.Reason is the only thing that humans distinguish themselves with. We're the leading edge of biological technology, — TheMadFool

Humans distinguish themselves from other species the same way crows, cats, and bees distinguish themselves from other species. We are no more the cutting edge of biological technology than whales and giraffes are.

Computing machines, on the other had, all work pretty much alike, have similar capacities (given a similar chip set) and do not evolve. When they are no longer useful, they are junked. There is nothing a computer can do to make itself more useful. -

Artificial intelligence...a layman's approach.Our brains are made of neurons and their language is electrical signals. — TheMadFool

Our brains are made of neurons, among other types of cells, and their language is chemical and electrical. Neurons to do not communicate between each other by electrical signals. They use chemistry. Electrical current is used within a neuron. If electrical currents were not complicated enough, chemical transmission makes it all even more complicated.

Intelligence isn't built into the hardware of humans. A newborn has the hardware and knows just about nothing. As newborns become infants, toddlers, young people, and finally adults the brain continuously changes itself to accommodate everything that is learned.

How does the brain do this? Among other things, it is directed by DNA. Know of any computers that are under the direction of DNA? -

Anyone on disability on here?The biggest problem I see in disability is that for some people (I am not thinking of you, Postface) is that disability benefits can, paradoxically, become a disability in themselves. This is particularly true for people who have have been working, depended on work for a social life and structure, and become disabled. Work provided them with an essential structure for their lives. Without the necessity of getting up and going to work, some people find their lives fallen apart. They can't provide a structure on their own. They have difficulty rebuilding a social life. They are lonely, and disorganized.

For people in this situation, religious participation, volunteering, a dog that needs to be walked every day, and such activities can help a great deal. -

What is the purpose of government?But there must be governance of some kind... — John Days

Yes. But in whose interest? Marx observed that in capitalist economies the state (the government) is the servant of the wealthy business class. That's fine if one likes it that way. But some people would like the state to be the servant of much more of the population which lives under the effects of its activities. -

Which is better? Ignorance, Confusion or Wisdom?The existential situation of humanity is that we are sloshing around in a bath of water that is dirty and getting cold. We have to make a decision. We can remain in the tub and get colder. Or we can drain the tub and start over with fresh, hot water. Or we can get out of the tub and dry off. Why don't we pursue one of the happier choices, instead of just sitting there in the cooling water?

I don't have an answer (sorry) but we seem to spend a lot of our time in situations like this, or wondering about things like "Which is better? Ignorance, Confusion or Wisdom?" It would seem obvious enough that wisdom is preferable to confusion and ignorance. Ignorance might be bliss if there is nothing that can be done to avert the impending doom. Don't worry about the impending doom you can do nothing about it. It is going to get every one of us in due time.

TMF: get out of the tub and pursue wisdom.

Now you have something worthwhile to wonder about: What is wisdom?

I think it is experiences from which we learned something useful, common sense, good advice, and a certain amount of reflection boiled down into nice golden brown gravy which goes well on mashed potatoes. Wisdom tastes like fried chicken gravy. It's delicious.

There is actually quite a bit of reasonably good canned wisdom around. Some of it is on the eye-level shelves where the highest profit items are displayed. Sometimes it's on the bottom shelf where the products that don't move go.

I gave you an example of reasonably good wisdom above: Ignorance is bliss when there is nothing you can do about the impending doom. Don't worry about it. If you happen to know what your impending doom is, then embrace it. You might as well, because it's yours to keep. Otherwise, occupy your mind with more pleasant matters, like the delicious chicken gravy smell of wisdom. Follow your knows [accidental pun, but it's worth keeping]. If something stinks, leave it alone. -

Anyone on disability on here?It isn't a question of remaining weak. It's a question of administrative interpretation. Undertaking college work is a good thing. An administrative judge over-seeing a review might interpret doing well in college as either a sign that the person was trying to better himself, or, was malingering and wasn't actually disabled.

There is no reason for a client to risk having benefits to which he is legitimately entitled taken away because of misinterpretation of the client's intent. I'm just suggesting that our client use some caution. -

Anyone on disability on here?I am glad you received disability status. The benefit will help you either find yourself something more satisfactory, or if you don't, keep you from starving into your old age. However... bear in mind, that disability can be revoked. I'm not trying to scare you, but Social Security does periodic reviews to find out if you are still disabled. Most people who are disabled do legitimately stay that way, but they may get better, or the standards of disability may change.

I can't remember how old you are, but you haven't earned very high income in the past, right? So, your disability payment is probably not very large. Do apply for housing assistance. At least in this state, disabled and elderly are the first in line for public housing. But be realistic--how long is the waiting list? If it's 1 year long, not too bad. Ten years... a different story. But sign up anyway. In 10 years you will still need housing.

Do apply for food assistance (food stamps). It will help your disability payment go farther.

I assume that you qualified for disability with a doctor's support. Keep a relationship with your doctor, or some other doctor, because when your case is reviewed you will need to support your claim again. (Most people keep their disability status, because they really are disabled.)

Be sure that going to college doesn't undermine your claim to disability. Taking a full load or better and getting very good grades would kind of undermine your claim. (This would be relevant at the time of your review in several years.)

Yes, you can work and collect disability at the same time, but not work full time for years on end and still collect disability. There is a program for people who want to try returning to work. Your benefit level may sort of force you to work to make ends meet, at least part time, if your benefit level is at the minimum.

What is your medical insurance situation like at this point? Medicaid? (I'm assuming you are not qualified for Medicare yet.)

My partner was disabled for the last 15 years of his life. It greatly improved the quality of his life. Most people who are disabled do much better with disability than without it.

As always, good luck. -

Depressive realismPlease keep in mind that there is a line (rather fuzzy) between clinical depression and with it, suicide that accompanies it, and the sort of depression some people experience while allowing them to function to some degree. — Posty McPostface

Yes, this is a familiar line. Many depressed people function quite well. -

How long will human beings last? Is technological innovation superior to natural innovation?How do you know they won't love and adore us? They may actually like us.

-

Will the Arctic Methane Emergency Crisis Kill and Displace by the Billions?e won't live to see the devastating effects of climate change, combined with the runaway effect that could be entailed by methane release. In most likelihood, we will learn to adapt to the new state of affairs provided by climate change, at the cost of hundreds of billions if not trillions to adapt our cities and current infrastructure and agriculture. — Posty McPostface

Whether you live to see devastating effects of climate change depends on your age. I'm 70. I plan on being dead in a decade, so I'll be spared (I hope). If one is 50 and lives another 30 years, you'll be around to see worsening conditions, but not rock bottom. If one is 30, and might live another 60 years, you'll most likely have a view of some pretty bad conditions. If one is 10 or less, with a life expectancy of 90, hey -- you are IN LUCK -- you're going to get to see big time climate change problems.

As for adaptations, yes and no. Some places in the world can't adapt -- they'll be depopulated by death or migration.

Cities north of the 40th parallel and not on a low-lying shore, (like most of the Netherlands is) will not experience severe heat, severe water shortages, or severe and long-term flooding from ocean rise. A city like Boston has areas that were filled in harbor. Those areas will likely flood. Lower Manhattan will flood, but the rest of those two cities will be OK. Miami will be toast -- wet toast. New Orleans will be flushed down the drain. The Mississippi Delta comprises Mississippi, Louisiana, and south-eastern Texas. That land is too low to be stay above water.

The cost of adaptation will certainly be in the trillions--pounds, dollars, yens, or euros. But there are real limits. If the wheat, soy, and corn fields of the world are too hot and dry or too wet, there just won't be as much food as is needed. As for fruits, nuts, vegetables, and the like -- some areas will do OK, and some won't. -

Will the Arctic Methane Emergency Crisis Kill and Displace by the Billions?Regarding excess heat in South Asia:

-

Will the Arctic Methane Emergency Crisis Kill and Displace by the Billions?We can quibble about how much methane will rise from the thawed and warmed tundra and will erupt from methane hydrate deposits on the ocean floor, and exactly how long it will last in the atmosphere. But every additional warming brings us closer to our species thermal limit.

IPCC = International Panel on Climate ChangeMethane is a powerful greenhouse gas. Despite its short atmospheric half life of 12 years, methane has a global warming potential of 86 over 20 years and 34 over 100 years (IPCC, 2013). The sudden release of large amounts of natural gas from methane clathrate deposits has been hypothesized as a cause of past and possibly future climate changes. Events possibly linked in this way are the Permian-Triassic extinction event and the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum. — Wikipedia

https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/plugged-in/methane-hydrates-bigger-than-shale-gas-game-over-for-the-environment/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Methane_clathrate

Some qestions i have for anyone with environmental and weather sciences knowladge is: — XanderTheGrey

Can the relase of methane cause widespread increase in forrest fires and how does it work?

By raising the average temperature of a climate area, the soils dry out (and with it, the trees eventually) and warmer winters allow insect vectors to survive. Greater insect infestation leads to more tree diseases, and more dead trees. Millions of acres of dead and/or dry trees are a forest fire hazard under any circumstances.

I don't know where you live, but Minnesota and surrounding states have had very poor quality air on some days from fires which are 1000 to 2000 miles away. In some cases the smoke was at ground level all day.

Can it cause an increase in hurricanes and or tornadoes and how does it work?

Oceans and land in a warmer climate have more thermal energy stored up in it, and thermal energy (along with other factors) drives cyclonic storms. So, yes.

Will it effect lightning? In what way, and how?

The more storms, the more lightning. Methane won't have a direct effect on lightning.

What temperature can a human being survive at individually?

There is the "wet bulb temperature" -- the lowest temperature that can be achieved by evaporation. So, if it is 100% relative humidity, and the temperature is 95º F, a person will not be able to cool down below 95º. As the temperature rises above 95º F, the individual's temperature will rise with it. If the temperature rises to 106º or 108º, with saturated humidity, the person will begin to over heat and will die at some not very distant point (oh... 15 to 60 minutes, depending).

Why aren't more people dying, if this is so? Two reasons: Mad dogs and Englishmen go out in the midday sun. Just about everybody else stays in the shade. That's one. The other reason is that it isn't very often 100% humidity and 110º F. People can survive 135º F if the humidity is low -- because they can evaporate away heat.

Most places aren't going to experience these kinds of lethal "wet bulb temperature" levels. But the river valleys of southeast Asia will, and not in the far distant future. About 1.5 billion people live in these river valleys, and a lot of their food grows there. If people can't work the fields, they will die of heat stroke first, and if no agriculture, then starvation.

Other areas will have survival problems too. The SW U.S. won't experience web bulb temperatures like Bangladesh will, but even at 0% relative humidity and temperatures of 125 all day, everything is dead before too long. (Hot air and desiccation can kill things as well as saturated humidity and somewhat temperatures). -

How long will human beings last? Is technological innovation superior to natural innovation?And if we only have 750,000 years left, that's plenty. Of course, it could be a lot less. There are plenty of large chunks of material "out there" that could be jostled loose by a passing star, for instance. The chunk might wander our way and crash into our planet. Sic transit gloria mundi. Literally.

Or, we may trigger enough global warming to cook our own goose. People can only stand to work in so much heat, and as the average temperature rises, more and more places will be too hot, too wet, or too dry for our plants or us animals.

Disease is always a possibility. Nuclear war can't be ruled out (not because of North Korea, but because of all the more familiar nuclear powers). And it may be that an Angry God may decide to let go of this sin-soaked celestial ball, suspended over the pits of Hell and do away with the lot of us. -

Depressive realismIs it the case that depressive personalities take a greater delight in irreverence, satire, travesties upon the dominant class, sarcastic jokes, and so on?

I hope so.

BC

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum