Comments

-

Critical liberal epistemologyAll of this is begging the question. It assumes that there is some method of doing this — Isaac

Doing what? Differentiating more correct beliefs from less correct beliefs?

I’ve already given an argument for why we could only ever assume one way or another about that, and why we pragmatically ought to assume there is, instead of just assuming there’s not.

Also, per critical rationalism generally, saying “you can’t prove that” is not an argument against anything ever. You need an actual disproof, not just pointing at how someone is assuming something, became we’re all always assuming tons of things and that’s not wrong, only persisting contra counter-evidence is.

You'd have to first resolve Van Inwagen's argument from epistemic peers (broadly, if you don't already know it - if one of your epistemic peers disagrees with you about a matter, then that proves it is possible for someone with your knowledge and skills to be wrong despite thorough application to the issue - if that's the case then how will you ever know it's not you who are wrong?) — Isaac

The resolution to this is built right in to the system I’m advocating. There are always a range of possibilities that someone with the same knowledge and skills can rationally disagree within, on my account, because nobody can ever pin down one exact comprehensive truth. Within that range you can’t know you’re not wrong; “you might always be wrong” is a core upshot of my view. You can only ever know what possibilities are for sure wrong, never which are for sure not wrong.

That you think it's just the negation of those two things is one of the matter under contention. — Isaac

It’s literally just defined as such. Anything at all that is neither fideistic nor nihilistic is okay on my account. I think you think I’m advocating something much narrower or more specific than I am.

This essentially repeats the same foundationalist error you're trying to eliminate. Your previous arguments are not somehow 'foundational' to these — Isaac

Foundationalism starts with basic beliefs that are taken to be self-evident or indubitable. I don’t do that. I start with reductio arguments against certain broad classes of view — fideism and nihilism — showing how assuming that those are true leads to problems, and then just taking whatever else is left over, which is a really broad class of things. Exploring the implications of that on other things just means seeing what possibilities on those other subjects fall outside those bounds, into the already ruled-out realms of fideism or nihilism, and what remains still in the acceptable domain between them.

sticking to you unaltered beliefs despite nearly all of your epistemic peers disagreeing with you... — Isaac

It really doesn’t seem so much like disagreement as it does a strangely aggressive agreement aggravated by some sort of miscommunication.

It’s like I’m saying something is a quadrilateral, and others are vehemently opposed to that because it’s obviously a trapezoid, or a parallelogram, or a rectangle, or a rhombus, or a square... and I’m saying yeah, it’s all of those things, all of those things are quadrilaterals and also it’s possible to be all of those kinds of quadrilateral at the same time. Why do you think we’re disagreeing? My only point is that it can’t have fewer than 4 sides, and it can’t have more than 4 sides, so it must be a quadrilateral. -

Joe Biden: Accelerated Liberal ImperialismBut obviously I was looking for a clear-cut case: wouldn't you agree that there are cases that are clear-cut enough for pacifism to be morally reprehensible, even without an explicit call for help? — jamalrob

I guess the analogy wasn’t clear enough then, because the point of it was that we can (and should) intervene just enough to find out if our help is welcome by the people we think are in need, even without it being explicitly called for. If the apparent victims want us to butt out, we should. We shouldn’t just assume that they want us to, and go headlong into attacking their apparent enemies. -

The Road to 2020 - American Electionsthe confidence of the whole people [...] divided between exploiter and exploited, oppressor and oppressed. There is no unity to be found with kleptocrats and oligarchs. — StreetlightX

While the government is divided between those who openly back the exploiters, oppressors, kleptocrats, and oligarchs, and those who at least give lip service to the oppressed and exploited — and the people are divided between who supports one of those sides or the other — the people in general are not divided into oppressors and and oppressed: they are almost all oppressed.

Winning the confidence of the poor struggling white men etc who make up Trump’s base is important to do, just so long as it isn’t done by conceding to the rich white men in the Republican party who are exploiting them and everyone else. -

Joe Biden: Accelerated Liberal ImperialismI once saw a man and a woman fighting (physically) in a public place, and out of concern for the woman I stepped in to ask her if she was okay or needed help. They both stopped fighting and explained that it was play fighting and she said she was fine and didn’t need any help, in a believable manner. I’m glad I didn’t just assume she needed my help and wade in punching the guy.

I hope this analogy is clear (True story, FWIW). -

Things we can’t experience, but can’t experience withoutNo, that sounds about right, though it's phrased a little unusually for talk of a theory. But yeah, Einstein discovered that Special Relativity was a possible way of modeling the world (and also discovered that the world fit that model, but that part was was discovering something concrete about the world). And Einstein created the first model of that form. Discovering the possibility and creating the instantiation were the same act, so it's not like we can say unilaterally that he only created or only discovered, because with abstract ideas you're always kinda creating and kinda discovering them at the same time, in different senses, never just doing one or the other.

-

Critical liberal epistemologyIt does address them, directly. You can falsify a belief that not P, and so prove that P, sure, but only by observing something contrary to the observations implied by not P — that is, bu falsification. Merely observing something implied by P cannot prove that P. That is confirmation and is just affirming the consequent.

Likewise, you can falsify a belief that P and so prove that not P, by observing something contrary to the implications of P; but you can’t just observe something implied by not P and take that is proof that not P.

Sure you can prove anything by observing something contrary to the implications of its negation, whether that thing is it’s even a negation of something else or not; but you can’t prove anything just by observing something consistent with its implications. -

Critical liberal epistemologyThe truth of every statement is equivalent to the falsehood of its negation, sure, but that’s not the point in contention here. The point is the form of the argument being made about something.

You can say “if not P then Q, not Q, therefore P” and that works just fine. You can also say “if P then Q, not Q, therefore not P” without problem either. It doesn’t matter whether the antecedent (the beliefs you’re testing) is some proposition or the negation of some proposition. What matters is that you can’t say “if P then Q, Q, therefore P”, or “if not P then Q, Q, therefore not P”. Both of those are invalid inferences, whether the antecedent is a negation or not. The point is that you can only validity deny the consequent from an observation contrary to the consequent, you can’t confirm the antecedent from an observation affirming the consequent. -

Things we can’t experience, but can’t experience withoutAbstract ideas are neither found, nor made; they are thought. — charles ferraro

Sure, that’s a fine way of putting it.

Please explain with greater precision what your statement means which begins with "... because there is nothing to be found but the potential for something to be made, but that potential itself was not made, it was always "there." " What is the subject you are referring to here? — charles ferraro

Two different subjects:

When people speak of discovering something abstract, the “thing” they have discovered is just the possibility of making something concrete, because abstract things are nothing more than possible forms that concrete things could take on.

But when people speak of creating something abstract, they are not talking about creating that possibility that is the subject of the discovery above, but just of creating the first concrete instantiation of that form, since it was always already possible to create things of that form, the “creator” didn’t make it possible. -

Critical liberal epistemologyAbduction falls into the same place as induction as far as I’m concerned: a fine way of generating a guess, a hypothesis, a theory, a model, a belief. What I’m concerned with is not how to come up with them, though, but how to choose between them.

And when trying to choose between them, finding more results that follow the prediction of one of them tell us nothing, unless those results also go against the predictions of the other one, in which case you’ve falsified the other one. But you’ve still not verified the alternative, because it’s impossible to ever verify anything, since the verification (or confirmation) process is logically invalid, just affirming the consequent. -

Joe Biden: Accelerated Liberal ImperialismNothing gives a government or group of people the moral right to intervene in the internal affairs of another country other than a direct attack or a genuine call for help. — Daniel

:up: :100:

I’m almost a complete pacifist, and even I’ll say it’s fine to go help someone else under attack if they want it, and they’re in the right in that conflict, and we can afford to stick our necks out for them.

If I was dictator for a day I’d make that the official requirements for ever going to war. -

Critical liberal epistemologyTo my way of thinking achieving parsimony is done by weeding out propositions or assumptions that are not grounded in anything other than imagination, association or feeling. — Janus

I’ll save further discussion on parsimony for the thread on that, but for now I’ll just say that your characterization of it does not bear any resemblance to mine.

Earlier, unless I am mistaken, you said somewhere that you wanted to dispense with induction; that critical rationalism does not depend on inductive thought. — Janus

I said earlier that induction is perfectly fine (and indeed very useful, though not exclusively so) as a way to come up with beliefs in the first place, hypotheses to test. It’s just not a proper part of the process of testing which beliefs are correct when there are multiple competing hypotheses.

Two hypotheses reached by induction can’t be judged for their relative merits just by finding more things that fit either pattern. You need to instead find something that doesn’t fit at least one of the patterns — which is then into falsification, and so critical rationalism. -

Things we can’t experience, but can’t experience withoutI was referring to "natural", not manufactured, empirical entities as being encountered. — charles ferraro

Sure, but that's completely uncontroversial. My point is that the distinction between something being found and something being made originates in a distinction between kinds of concrete objects, "natural" vs "artificial", found-in-nature vs made-by-man. And that distinction doesn't really properly apply to abstract ideas, because there is nothing to be found but the potential for something to be made, but that potential itself was not made, it was always "there". (Not like in some Platonic realm, but as in it was always possible to make the thing, nobody created the possibility, they just found out that it was possible.)

I do not subscribe to the Platonic notion of pre-existent abstract ideas being instantiated. — charles ferraro

Neither do I, which is why I don't just come down on the "ideas are found" side of the divide. I'm also not on the "ideas are made" side of it. I'm saying the divide doesn't apply to ideas, only to concrete objects. -

The Road to 2020 - American ElectionsI think you misunderstand how right wing populism works. Yes, it is backwards-looking, but it's not conservative in the usual sense. Right wing populists like Trump, Johnson et al did not promise to keep things stable. They promised a return to the natural state of (national / racial) superiority by smashing the "establishment", which purportedly maintains an artificial, unnatural state. They want change, but change toward some ideal version of the past. — Echarmion

IOW they’re radical regressives. -

The definition of knowledge under critical rationalism

-

Critical liberal epistemologyYou just seem to think this is some use in dealing with people who don't already agree we have to start in the middle, and I don't see how it possibly could be. — Srap Tasmaner

No, I started off with arguments for why we must start in the middle. I’m not repeating those arguments in full in every thread, but exploring the implications of that conclusion on each sub-field of philosophy, thread by thread.

Something else I've had on my mind. It is sometimes said that epistemology is a search for a method that, if followed, would produce two results: (1) believing things that are true; (2) not believing things that are false. Critical rationalism is a claim that we get (1) for free so long as we do (2), at least in the very long run. But that only makes sense for finite sets of beliefs, hence you're inclined to model a person's web of beliefs as a snapshot that is at least arguably finite, on the grounds that it's hard to see how a person could hold an infinite number of beliefs. — Srap Tasmaner

As I frame it, believing anything at all always has some odds of believing things that are true, so if we go about eliminating beliefs in things that are false, we increase the odds that our remaining beliefs are true. And this works whether we have finite or infinite beliefs. Take an infinite continuous plane, and repeatedly draw lines across it marking the boundaries of possibility, and you will end up enclosing a smaller and smaller area between those lines, even if there are still infinitely many points in that area. -

Donald Trump (All General Trump Conversations Here)Born and raised in California, Elder Millennial (HS Class of 2000).

-

Joe Biden: Accelerated Liberal ImperialismI just realized I may have to clarify something for suspicious readers: my criticism of liberal imperialism here is not in any way connected with the criticisms of liberalism that have occasionally been heard from the Russian government and leadership over the past few years, and my opposition to American cold warriors should not be seen as support for authoritarian rule. — jamalrob

I was also suspecting that it would be necessary to clarify that you mean “liberal” in the historical and current international sense, which is closer in meaning to the American sense of “libertarian”, or perhaps just “capitalist”, and is generally a right-wing position contrasted with labor parties, socialism, and other leftist movements.

Not in the modern American sense of “liberal” as opposed to “conservative”, meaning roughly “left” and “right”.

Thankfully it looks like nobody has assumed you were attacking the American left from a right-wing point of view. -

Critical liberal epistemologyI object to the implication (resulting from such a long exposition) that there exist people who seriously disagree with you but who do so only because they haven't seen the strength of your argument. If you think these people are irrelevant then it seems petty to disabuse them of the cruxes. If rather, like me, you think these people's purported beliefs can be quite importantly damaging, then it seem crucial to find out exactly why they have them (or pretend to), not just guess at it from your armchair. — Isaac

So you admit that such people do exist. Why then were you pressing me for proof of them? This is the kind of thing that makes me suspicious that you're not arguing in good faith, when you radically doubt things that I would really expect you to already agree with... and it turns out later, you do.

Anyway, I never said those people are irrelevant, I said that it's irrelevant for the purposes of philosophy to know why they believe those things (or pretend to, if you like). For philosophical purposes, all that matters is whether those (purported) beliefs are true, or at least justifiable, and the causes of people believing falsehoods don't tell us whether or not they're false or unjustified.

For broader social purposes, it's good to know why people believe falsehoods. But to know that they believe falsehoods, you first need to know whether or not the things they believe are false.

It would not be very epistemologically sound, or discursively fair, to approach someone espousing something you think is false and reply to that only with an analysis of the conditions that have caused them to come to believe that, as if presuming that they are a crazy person who can't think rationally, just because they've reached a different conclusion than you. If what they believe is actually true, then you'd be dodging the issue they're trying to talk about entirely.

When people do irrationally believe falsehoods (or meaningless nonsense), it is good to figure out what's causing them to do that, but first we need to assess whether what they believe is false, and whether they believe it on rational grounds. To do that, we need to determine what the rational grounds for believing things are... and that brings us back to epistemology again.

(And if they are believing falsehoods on rational grounds, then doing philosophy with them, i.e. having a rational argument, is the most epistemologically sound and discursively fair way of changing their mind anyway. Only once that fails, and we conclude that they are not thinking reasonably, should be begin concerning ourselves with the irrational causes of their nominal belief).

I strongly disagree. It's absolutely imperative if you're going to advocate a task that the task is either achievable or, if not, then the partially achieved task is worth the effort that must be put into it relative to other methods. We can't fly either, despite the fact that it would be great if we could (save a lot on fuel). Do you think on those grounds alone it would be sensible to advise that we 'keep trying' to fly, just do our best, keep flapping those arms and jumping even if we only get a little bit off the ground because flying would be so great if we achieved it. No. If it is abundantly clear that a method cannot be achieved, then we need to consider the next best alternative - not just assume that a partially achieved version of the first idea will automatically be the next best thing. — Isaac

Unless you think fideism or nihilism will get us anywhere (which it seems you don't), then whatever other method could possibly get us anywhere will be some subset of my method, because it's just the negation of those two things.

Your flight analogy is actually quite similar to an analogy to this general balance of neither-fideism-nor-nihilism that I thought up a while back. That balance recurs throughout my philosophy, and I thought this analogy up originally in terms of existential nihilism etc, but it works just as well for other cases like this:

We're on the surface of an infinitely deep ocean, with the infinite sky above us. Therefore we cannot stand on the bottom, because there is no bottom. And we cannot grab for the sky, because the sky isn't some solid ceiling above us; nor can we just stick our arms up and hope our imaginary friend Superjesus will save us from drowning or anything like that. If we try to do either of those things, stand on the bottom or hang on to something above us, we will surely drown. Therefore we have to do something other than those things: neither try to stand on the bottom nor hang on to anything above us.

In other words, we have to swim. I'm not specifying how to swim, nor saying that the specifics of how to swim are unimportant. I'm just pointing out that there is no bottom to stand on and hanging from the sky isn't an option either, so we've got to do something else directly involving the water we're immediately surrounded by instead.

What exactly to do is beyond the scope of philosophy, and the realm of more specialized sciences. -

Donald Trump (All General Trump Conversations Here)I was going to reply to @tim wood with a much inferior version of that as soon as I got a moment, and I'm glad that you were able to get to it before I could. :clap: :100: :up:

-

Things we can’t experience, but can’t experience withoutOr, should we say he did both, simultaneously? — charles ferraro

Sort of both and neither. With abstract objects it's not really possible to differentiate.

Also, I think concrete objects (entities), not being abstract ideas, are encountered, neither discovered, nor invented. — charles ferraro

Some concrete objects are invented (or created if you prefer). This computer, a concrete object, isn't something that someone just found (discovered, or encountered if you prefer). Someone made it. On the other hand another concrete object, El Capitan, the famous monolith in Yosemite valley, was discovered, not invented. Someone just found it there already like that.

Abstract ideas, meanwhile, being nothing but possibilities until instantiated in concrete objects (including in human minds), are "made" by being "found", and "found" by being "made". To come up with an idea just is to realize something is possible; but it was already possible before you came up with it; yet there was nothing to that possibility other than the potential for someone to come up with that idea. They don't really come apart.

But this is really more a topic for that other thread (Creativity: Random or deterministic? Invention or discovery?) than this one. -

Donald Trump (All General Trump Conversations Here)In the version I’m familiar with, the scorpion stings the frog mid-crossing, and so both of them die. As the frog pleads why, the scorpion replies that it was his nature.

That seem ls more like a Trump thing to do. Take everyone down, even at his own expense, not even for any particular reason, just because it’s the kind of thing he does. -

The Road to 2020 - American ElectionsPost-truth bullshit.

If it isn't the truth, then its a lie. — Harry Hindu

Interesting that you use the word "bullshit" here when denying that the philosophical sense of 'bullshit' exists. TL;DR: a lie presumes you know and care that what you're saying is not true: you're trying to hide what is true behind a falsehood. Bullshitting is when you don't care (and so might not even know) whether what you're saying is true: if it is, how fortunate, but if not, no problem. They're different kinds of dishonesty. -

What's Wrong about RightsThere are different senses of "right", and you're conflating at least two of them here, while denying that another is a sense of the word at all.

There is a sense of "right" that just means "freedom". These are sometimes called "liberty rights". You have a liberty right whenever you're not prohibited (by law or morality, whichever system you're talking about) from doing something.

Then there's a sense of "right" that means what you say, a limit on others liberty rights, which places an obligation on them toward you. These are usually called "claim rights" to distinguish them. Property rights are claim rights.

Both of those are first-order rights, and there are second-order versions of each.

A second-order liberty right is a "power", which is basically the liberty to change others' first-order rights, to permit or prohibit things, to create or abolish obligations. These are the kinds of "rights" that states claim over their peoples.

A second-order claim right is an "immunity", which is a limitation on powers just like claims are limits on liberties. You have an immunity exactly when someone else doesn't have a power over you. Civil rights are generally immunities; everything in the US Bill Of Rights is an immunity, explicitly limiting the powers of congress (and later, via the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th amendment, state legislatures and all other lawmaking bodies as well). -

Depressed with Universe Block (and Multiverse)Does this imply that the atoms of an object "now" are not the same that those of the one second ago? — Philosophuser

What does it mean for an atom "now" to be (or not be) the same as that of one second ago?

The notion we have of diachronic identity (something being the same thing over time) comes from our experiences of things persisting over time. Exploring the exact nature of time and such doesn't change the applicability of that notion.

It's like when general relativity changed the prevailing explanation of why things fall down, it didn't mean that things "don't really fall", just because "falling" is now equivalent to "following a straight line in curved spacetime". Thing still really fall, just like we always thought they did, we just understand better now what falling is all about.

Likewise, I'm still the same person I was when I started this post, whatever that turns out to mean. I'm obviously not qualitatively identical to the way I was back then, I've lost some skin old dead cells, maybe grown some new ones, etc. But also, my arm is different at the wrist than it is in the middle of the bicep, yet it's still "the same arm" across the space in between them, despite those differences in different places. Being different at different times is no different than being different in different places like that, according to eternalism.

I think your connection between eternalism and modal realism (multiverses) is insightful, and I'm glad that someone else besides me has caught on to that. I think that the space of possible worlds (the multiverse) is more fundamental than time, and time is just a direction through that space, from less-entropic worlds to more-entropic ones (and we perceive it in that direction because memory-formation, like all processes, necessarily increases universal entropy, so earlier memories are always of less-entropic worlds).

And yes, in the same sense that I am the same person as I was when I started this post, an alternate me who got interrupted by something unexpected and never finished this post is also the same person as the past self that we both have in common. But again, this is no different from how each of my separate fingers is each a continuation of the same arm (that's narrower at the wrist than at the bicep), even though the fingers are not themselves the same as each other.

As to depression about this, I don't really follow why it's depressing.

Is it just because eternalism seems to undermine free will? That's a big topic of its own, but my short response to that is that it really doesn't undermine free will, and I'm happy to elaborate on why not if you like.

Or is it because you're worried about how when you narrowly avoided something awful, there's probably also some alternate version of you (or lots more alternate versions of you) who didn't narrowly avoid it, a bunch of yous who died in car accidents when you almost didn't react to that crazy driver in time, etc?

I admit that is something that has troubled me before too, but in the end I find peace in the fact that in this multiverse view, everything that could possibly happen does happen and was always going to happen, and there isn't anything you could possibly do to make things that are possible in the abstract not possible anymore, so there's no point to worrying about it. The best you can do is try to make it improbable that they will happen to you, which simultaneously has the effect of (because it's the exact same thing as) minimizing the number of universes in which those bad things happen.

Basically, the upshot of you existing across the multiverse is "don't do risky things with a high chance of causing catastrophes, because if you do there will be a bunch of versions of you who suffer those catastrophes". But that's really just a different way of phrasing "don't do risky things with a high chance of causing catastrophes, because if you do you're likely to suffer those catastrophes". And you (hopefully) already knew that, so thoughts about the multiverse shouldn't change anything. -

Critical liberal epistemologyWhat people actually believe and what they publicly assent to (or even self-deceptively assent to in internal verbalisation) are two completely different things with completely different origins and processes, they involve different parts of the brain, they're about as disconnected as it's possible for two mental activities to be. — Isaac

Okay, well part of my position could be phrased in your terms here as "don't assent to things you don't actually believe", though I would phrase that instead as "don't believe things that have no bearing on your experience of the world".

Prior to Einstein humans didn't have a fundamental 'belief' in classical gravity, they had a fundamental belief that when you throw things up in the air they come down in a predictable way, they still do after Einstein. — Isaac

I was thinking more of things like the relativity of simultaneity, which is far more counterintuitive than just a different explanation for why things fall down.

The difference being I haven't written a long series of posts on a public forum under the assumption that other people could benefit from my insight on the matter. That sets the threshold of justification higher for you than for me. You asked me for my opinion (implicitly, by posting on a forum), I never asked you for your, you decided it was important enough for other people to hear. — Isaac

It's sounding more and more like you think my positions are generally correct, and only object that they are trivially so. If you find them trivial, that's fine with me. I don't especially care to convince anyone who thinks these things are trivially true that they ought to find them more significant than they do. I'm only really concerned about reaching people who either don't think these things are true, or who don't think they're trivial.

If that's not you, that's fine. I don't really get why you even bother responding in that case. If I see someone post something that's just obviously correct to me, I either don't respond or just post a thumbs-up emoji or something. Seems pointless to belabor how obvious (to me) the thing they're saying is. That you do that towards me just comes off as you being somehow offended that I dare say something so obviously true. It kind of reminds me of complaints about "mansplaining", like you feel like I'm condescending to you personally by saying something you already well know. If you already well know it and think it's uninteresting and obvious, that's fine. If everyone else agrees, I'll get no responses, and the post will fall off the front page quickly. That'd be disappointing, but better than the pointless tediousness that our conversations always turn into.

Well then a good place to start would be some quotes or texts in which these philosophers make the case that you're claiming they're mistaken in, or reach conclusions that you're claiming have missed a crucial step. Otherwise it's very difficult to see what you're arguing against. — Isaac

The entirety of Descartes Meditations is basically an exercise in this, starting off with a cynical justificationism rejecting everything that can't be positively proven from the ground up, then claiming some beliefs are basic and unquestionable (not just the cogito, which is much more subtle in its flaws, but he basically grounds everything besides his own existence on "God exists and wouldn't let me be deceived"). It's classic foundationalism.

Even further back, Aristotle (in Posterior Analytics) explicitly explored the three branches of the trilemma and decided that since the only alternatives were circular reasoning or infinite regress, some beliefs had to be regarded as basic and unquestionable.

Only if you attend to every single experience you've ever had simultaneously. Which is flat out impossible. — Isaac

Sure, but that just means humans are incapable of perfectly conducting the epistemic process, which is uncontroversially true. Humans are limited and fallible. Saying what they should aim to do doesn’t require that they be capable of doing it perfectly. Just that they should do it as well as they can manage, and if they fail at it in some way, that’s an error they should aim to correct. (E.g. if you come up with a new theory that disregards some old observations, that’s a mistake, and hopefully peer review will catch it and help keep it from spreading).

Only if you've started from a premise of denying naturalism about truth already. — Isaac

Or if that’s in question, and you’re not asserting it as an unquestionable foundational belief. You say “here’s a hand” and Descartes asks “Is there really though? I mean it sure looks like one, but my senses have deceived me before...”. I agree in the end that this is a dumb line of questioning he’s starting, but the goal of my project is to make explicit WHY that (and other things philosophers say and do) is not as wise as he thinks it sounds, but rather goes against not only what everyone commonly thinks, but what they’re right to think: yeah, here IS a hand, for reals (unless maybe [unlikely alternatives]).

If everyone already agrees that there’s a hand, great, we can move on from there and do real science. But philosophy is about things like what to do when that kind of thing is questioned, and whether we can find our way back to that common sense or are compelled to believe some strange nonsense instead. I think we can find our way back to common sense, but it’s worthwhile addressing the nonsense people and showing them that; and preemptively inoculating others against such nonsense, too. -

Things we can’t experience, but can’t experience withoutGood question! I don't think either discovery or creation, in the senses that we normally use them of concrete objects, properly applies to abstract ideas, or patterns. Rather, something that is in some ways discovery-like and in some ways creation-like is what we do when identifying patterns. I had another thread that was all about that a little while back, but the short version of my view there would be:

On the one hand, if we supposed that ideas were simply invented in the way that concrete objects are, that would imply that each idea did not exist at one point in the past, and then came into existence when instantiated. So, for example, the idea that 2+2=4 would not have existed, and so could not have been true, until someone thought of it, and then only after someone did think of it, would it have existed, and been true.

On the other hand, if we supposed that ideas were simply discovered in the way that concrete objects are, that would imply that ideas already existed in some accessible way completely unrelated to the possibility of them being instantiated. So, for example, for it to be discovered that 2+2=4, there must have already existed the ideas of "two", "four", "addition", and "equality", and the relationships between them, somewhere "out there" in some kind of strange realm of abstract objects.

It seems that we are prone to call it "invention" when it is the first known instance of someone having an idea, or if it’s a relatively non-obvious idea; and we are prone to call it "discovery" when it is a later known instance of someone having an idea, or if it’s a relatively obvious idea. But I think there really is no difference between them when it comes to abstract ideas; the distinction between creation and discovery applies only to concrete objects.

I'm not really sure how this stuff about alternate "dimensions" etc is related to this thread, but I'm generally opposed to anything supernatural (which it sounds like you mean), as described in more detail in the thread preceding this one that was linked in the OP. -

The definition of knowledge under critical rationalismit is as if there are two criteria, when really there is just one 'justification.' — Coben

I pretty much agree with this.

I'd just like to add that fideism is oddly binary and extreme. IOW it prioritizes faith, at least when it is centered on religion (and perhaps philosophy) and denigrates reason.

I think that's problematic when taken as one of the two main choices and when applied to beliefs in general.

There is no reason I can see not to have a mixed epistemology. I think we HAVE to have one to manage to live. With beliefs being arrived at in a variety of ways. Adn one need not denigrate the various methods and choose just one. — Coben

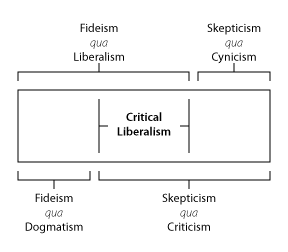

I don’t see fideism as one of the two main choices, but as one of the two main types of error, and the view I advocate is explicitly meant to be a mixed epistemology, taking things that each of those erroneous approaches get right (the criticism of cynicism and the liberalism of fideism), while rejecting both of their problematic extremes. -

Specific PlanThat seems to lead the left to thinking the right wants communism — TiredThinker

What?

Fascism ≠ Communism.

(Although the USSR and PRC and other countries ruled by authoritarian "Communist" parties self-avowedly practiced state capitalism as their "interim" form of government, and state capitalism is synonymous with the original sense of the word "fascism"). -

Critical liberal epistemologyBeliefs are just tendencies to act as if.... — Isaac

This may be a root of our disagreement. I do agree that well-formed beliefs are coextensive with "tendencies to act as if...", but there is a broader sense of "belief" that I am also concerned with here, a sense something like "propositions one would assent to".

There are things we tend to act as if were the case, these are fundamental beliefs and we don't question them — Isaac

We tend to resist questioning them, sure, but rationally speaking we need to always be open to questioning them if pressed. Look at how many widespread intuitive assumptions about the nature of the world have been overturned in modern theories of physics, for example. If we hadn't been willing to question those things, we wouldn't be where we are now in our understanding of the universe. Our intuitions are frequently wrong, sometimes even our deepest and most securely-held (and widely-shared) intuitions.

A basic belief, in the sense of foundationalism, of which Reformed epistemology is a species, is something held to be beyond such questioning, and it's my position that nothing is to be held as beyond questioning.

Yes, but we're still discussing whether you have actually shown this. This is another issue we're having here, we're in the middle of disagreeing over whether some issue has been shown and yet you still later refer back to it as if it had. — Isaac

As consistent with critical rationalism, there is no burden of proof on either of us to convince the other before we're allowed to continue believing as we did before. Claiming that I'm wrong and demanding proof doesn't require I give up my beliefs until I can do so. I think something is the case, you think it's not, and if you make some assertion on the grounds that it's not, I'm free to point back at my position that it is; that you've not conclusively established that it's not, so your assertion doesn't rest on solid ground since that's still in dispute. And you of course find my assertions to the contrary not to rest on solid ground either, since that's the same ground that's still in dispute.

My point being this isn't a one-sided thing; until the ground is settled, we both think the other is making an unfounded assertion by appealing to that ground, and neither of us is more right or wrong in thinking so, until the ground is settled. IOW I see you as doing the same thing you see me as doing.

That's not a belief. A belief is a disposition to act as if... Anything less is a meaningless statement and it's pointless to create a model of it, you might as well build castles in the air. — Isaac

Well you'll find plenty of people right here on this very forum claiming that God as they conceive of him is not empirically testable. I agree that this is a poor kind of belief, and ultimately claims of that sort are meaningless, but nevertheless people assent to the truth of such meaningless propositions. Showing why that's a useless or erroneous way of thinking is part of the aim of my philosophy.

It seems like you really want to restrict the topic of discussion to the subset of discourse where people are already being fairly reasonable, when all I'm trying to do is show why discourse beyond that subset is useless or erroneous. All the possibilities within the domain you're concerned about discriminating within are already A-OK by me; I'm only concerned with those who wander far outside that domain.

So what tests have you carried out to check that hypothesis? — Isaac

That hypothesis is not central to my project, so it's not something I've researched in any depth, and if the hypothesis turns out false it has no bearing on any of my main points, which are all about why it's counterproductive to do certain things, not what inclines people to do them. I'm just venturing a guess, informed mostly by my own interactions over many years with people who do those things (including their responses when I inquire as to why they do them), as to why they do them.

There you go, 100 words or so. See if anyone (serious) disagrees, if they don't, let's get on to the interesting stuff. — Isaac

As I said in my last post, I don't expect anyone to disagree with those premises. It's the implications that they have on other, common philosophical positions that would be contentious. Rejecting justificationism, the default form of rationalism most philosophers tend to assume, because it inevitably leads to either fideism or nihilism, for example. I expect most rationalists (e.g. most philosophers) to agree that fideism and nihilism are wrong (but not all of them, of course), yet not to have realized how all three justificationist possibilities (from Agrippa's/Munchausen's Trilemma) inevitably lead to one or the other.

And that is what I find to be the interesting stuff. You seem to find the interesting stuff to be the things that I say are work beyond philosophy and more the domain of more specialized sciences. Which makes sense, since you're a... neuroscientist? Psychologist? I forget what you do exactly but you study brains in some capacity, no? So it makes sense that you're more concerned with the nitty gritty details of how human brains in particular work. I don't think that's the domain of philosophy -- it's still important work, but not philosophical work -- and I'm focused on the broader philosophical stuff within which that kind of work is conducted.

How? I don't see how this process will lead to you being less wrong. It could just as easily lead to you constantly shifting beliefs to favour one experience only to find they now contradict an experience previously modelled well by your theory. — Isaac

Only if you discard your previous experiences that were modeled well by the old theory, which I assumed was obviously not implied. As you accumulate more and more experiences, the range of possible sets of belief that could still be consistent with all of them narrows.

So the entire matter rests on a judgement (both third party and introspective) of 'willingness'. Something which is a) entirely subjective, b) scalar, and c) has no proveable zero point as it anticipates future events. — Isaac

The third party assessment isn’t important at all for strict epistemological purposes; at most it’s useful for deciding whether you think it’s worth your time engaging in a discussion with someone who doesn’t seem open to changing their mind, but you can never be sure that they’re not and if time and effort were no consideration and all we cared about was arguing until we settled on the truth then guessing whether the other person is fideist or not would be irrelevant; we would have to assume they were not.

And it’s only in the third person that subjectivity is a problem: in the first person, you just decide whether you’re willing to change your beliefs or not.

It’s only in the first person that that matter, as one needs to remind themselves to consider all possibilities, even the possibility that one of their most cherished beliefs is false, if they really do care about figuring out what’s true. That’s not a scalar quality, that’s a boolean choice: “am I open to reconsidering this belief or not?” The only thing that makes it seem scalar is how integral to the rest of one’s belief system that belief is: one can be in principle willing to reconsider any belief, but if some beliefs would require that the whole rest of one’s belief system be made much more convoluted to accommodate their removal, then one is pragmatically right to consider other alternatives first.

If you're happy to let 'willingness' remains something naturalistically obvious to any rational person, I'd have no objection to that, but you have to then concede you have a naturalistic argument, not a logical one. Implicit in this concession is the requirement to absorb that which the proper sciences are showing to be the origins of such natural thought. — Isaac

A naturalistic account of epistemology cannot help but be circular, because to do the natural sciences soundly you need some epistemological account of what soundly done science is, and if that account in turn depends on the results of the natural sciences that in turn depend on the epistemological account for their soundness... well there’s your circle. -

Donald Trump (All General Trump Conversations Here)Also, I saw a rainbow this morning for the first time since April (I live in the desert). I swear to god, there was an actual rainbow about an hour after they called it. — RogueAI

It rained here for the first time since April too, and it’s such a gorgeous sunny post-rainy day that it feels like this must be a movie where the Big Bad is defeated and suddenly the sun comes out and the dead grass returns to life... and yeah, a big beautiful rainbow arches across the sky, though I didn’t get to see any here. -

The Road to 2020 - American ElectionsNot being Dubbya garnered Obama a Nobel prize... — Kenosha Kid

Yeah, and that was dumb too. -

The Road to 2020 - American ElectionsWhy not? — Wayfarer

For me, it’s mostly a repeat of Obama. W was the worst president of my life by then, ruining things after the heydays of the Clinton 90s, and Obama’s election promised to make everything sunshine and rainbows again. But none of the W-era problems got fixed in 8 years, and only the smallest bone of progress got thrown our way with the ACA, and even that just barely.

It’s great to celebrate the end of Trump, but it’s wise to actually hold Biden’s feet to the fire and let him know that merely not being Trump is not good enough, he needs to get on with actually fixing things and fast — plus, as Crank says, there’s a lot of things that simply aren’t in his direct power to fix. -

Critical liberal epistemologyLike the belief in the truth-preserving property of logic? — Isaac

No, that’s something completely different. Basic beliefs are the kinds of things one would use as premises in an argument. The validity of logical inference itself is not something you ever need to put in a premise of an argument, because if you did you would just get an infinite regress: “if P then Q, and P, therefore Q” would have to become “if P then Q, P, and if ‘if P then Q’ and P then Q, therefore Q”, ad infinitum.

And yet you claim to have no power other than your own ad hoc reckoning to justify an assertion that anyone does, in fact, think in a fashion other than this method you're expending so much effort advising us all of. — Isaac

And other people’s explicit advocacy of methods to the contrary, as I already said.

Oh, and I forgot in my answer to last post, something someone else (Janus?) already brought up in this thread earlier: some kinds of beliefs can only be held on fideistic grounds, like if you believe in the kind of God that cannot possibly be detected observationally. So if someone believes in that kind of thing, you know they’re believing it fideistically.

Why would anyone ever believe in something that no observations could possibly have led them to think was real? You’re the one saying everyone always has experiential reasons for their beliefs. My hypothesis is that they arrive at these kinds of unassailable but useless beliefs after they’re challenged in arguments and modify their old beliefs however necessary to avoid “losing”, even if it requires methodologically “cheating”.

As it is, the rest of your philosophy seems to either be trivially true to the point of uselessness — Isaac

To someone who agrees with it, I would hope it would. Premises are supposed to seem trivially true in any argument, since starting off with controversial premises just begs the question. To someone who can easily see the implications of those premises, the conclusions should seem equally trivial. It’s only people who already agree with the premises but didn’t realize their implications who are surprised to learn something from an argument — any argument, not just mine. It’s the people who didn’t think through all the implications of these trivial premises I’d hope everyone would agree are obvious that I’m hoping to reach with my arguments.

Yes, and that is the topic of the next thread I have written up already.

— Pfhorrest

Oh good God, no! — Isaac

See, this is the kind of thing that makes me think you just want me to stop talking.

The parsimony thread I have queued up doesn’t hinge on critical rationalism, it touches on things that could apply in a justificationist epistemology too.

Like I said at the start of this thread when you were upset that I dared to post this, I’m trying to start separate discussions on each little piece of each topic that I have some original thought on, rather than just one huge 80,000 word “here is everything I have to say about philosophy” post. And I’m spacing them out so I don’t flood the front page with dozens of threads all at once. Of course a lot of them are going to connect to each other, because everything in philosophy connects to everything else.

Besides just not posting, or that one huge 80k-word post, or maybe quarantining all my posts in one General Forrest Thread (should all users be quarantined to one thread like that? Lots of people start lots of threads wherein they repeatedly touch on the same theme; anything by schopenhauer1 is probably anti-natalist for instance), I just don’t know what you want from me.

Now we can add 'simple' and 'elegant' to our list — Isaac

Obvious synonym for “parsimonious” is obvious.

How do we form beliefs in the first place? "Do something reasonable." How do we apply the rules of the method? "Do something reasonable." How do we decide what belief to drop? "Do something reasonable." How do we gather and weigh new evidence? "Do something reasonable." — Srap Tasmaner

I don’t say “do something reasonable”, but just “do something” — presumably you’ll do what seems most reasonable to you, but whether that’s actually reasonable and what “actually reasonable” means in that context is not something my model cares about.

Go ahead and believe something, for any reason or no reason, it doesn’t matter. (This is the “liberal” plank of my system, contra “cynicism”).

When you experience something contrary to what you believed you would experience, change your beliefs, exactly how and why doesn’t matter. (This is the “critical” plank of my system, contra “fideism”).

Repeat forever and you’ll get less and less wrong over time. Just keep trying on beliefs (never give up and say you’re never believing anything again until it’s first proven for certain), and changing them when they fail you (never give up and say some belief you hold just has to be right because it just does), and you’ll continually improve.

How you pick your initial beliefs and how you change them doesn’t matter, so long as you keep up the process. Some methods could certainly be more efficient than others, and that’s an interesting question itself, but that’s a different question from whether they are epistemically valid or not. On my account, epistemic validity just requires that you believe something or other regardless of how little you have to go on, and that you remain willing to change anything you believe when you encounter evidence to the contrary. -

Critical liberal epistemologybasic immutable belief — Isaac

That is exactly what I mean by fideism. If you think any beliefs are basic and immutable, not subject to question, then that's fideistic.

against foundationalism — Isaac

Foundationalism likewise is all about basic beliefs.

You seem to have missed a long post early in this thread where I went through all three branches of Agrippa's/Munchausen's Trilemma, concluding that both foundationalism and coherentism are fideistic, while infinitism is nihilistic, and on those grounds reject justificationism in its entirety in favor of critical rationalism instead.

Hang on - are you describing the way our minds actually do work, or advocating a way they should work? — Isaac

Primarily the latter, but I don't think that that's generally in conflict with the former. I think most people generally act like they agree with the broad strokes of this methodology, they're just not consistent about it -- when threatened with the frightening prospect that maybe they were in error and someone else is about to "win" against them, they look for a way out, and cheat the system they otherwise seemed to agree with until then.

People tend to argue about things as though some of their opinions are right and others are wrong, or at least some are more right or wrong than others; and as though they can sort out which of their opinions is which, or at least which lies more or less in one direction or the other. Otherwise, they wouldn't be arguing in the first place.

I think that those basic implicit premises of every argument should be treated as correct, because either “I’m just right and you’re just wrong” (supposing that some answers are unquestionable) or “there’s not really any such thing as right or wrong” (supposing that some questions are unanswerable) are lazy ways to dodge the argument, avoiding the potential of having to change one’s opinions, and so cutting one off from all potential to learn, to improve one’s opinions.

All the rest of my philosophy stems from rejecting those two cop-outs and running with whatever's left.

are you claiming there's some objective algorithmic method of determining parsimony — Isaac

Yes, and that is the topic of the next thread I have written up already.

a first reading of C — Isaac

This is every bit as subjective judgement as my use of "obvious" for the same purpose earlier. I think you and I, who seem to have similar on-the-ground beliefs despite our philosophical differences, would likely see the same reading as "obvious" / "first", but if "obvious" is too subjective then so is "first reading".

How do we judge? — Isaac

In the third person, we can't, at least not conclusively. We'd have to rely on their self-reports of whether there is anything that could possibly change their mind about B or if that's a "basic immutable belief" to them.

We can take an educated guess at whether they're holding B like that or not, though, based on how un-parsimonious a system of beliefs they're willing to construct to excuse the preservation of B. If they're doing all kinds of twisty mental gymnastics full of exceptions upon exceptions to preserve B when it would be much easier to just reject B and leave everything else simple and elegant, that suggests -- though doesn't prove conclusively -- that they're likely unwilling to question B. -

Sex, drugs, rock'n'roll as part of the philosophers' questI think there is no intrinsic conflict between pleasure and philosophy, especially moral philosophy. That’s parallel to supposing there’s a conflict between empirical experience and philosophy, or between empiricism and reality.

Sure, there is definitely a trend going back at least to Plato that says both that the world of empirical experience is unreal and that hedonism is immoral. But there are plenty since then who disagree vehemently.

For my part, I disagree vehemently, but that doesn’t mean that everyone ought to pursue nothing but their momentary pleasures, any more than it means you should believe things disappear when you’re not looking at them. Past and future experiences matter in both cases, the description of what is real and the prescription of what is moral.

And more than that, OTHER PEOPLE’S experiences matter just as much as your own: both in that their corroboration of your empirical experiences matters for determining what is real, and in that their hedonic experiences matter as much as yours in determining what is moral.

Basically, the reason it’s wrong to hurt someone is because it HURTS them, causes pain, the opposite of pleasure. All sane accounts of morality connect it intimately with hedonism. -

Critical liberal epistemologyThe point that you seem to be glossing over is that it is on the basis of inductive thinking that we decide which of the range of possibilities we can imagine are "far-fetched". — Janus

I have already described what I mean by far-fetched in a way that has nothing to do with induction, and everything to do with parsimony. -

Critical liberal epistemologyYou'll tend to shrug off some of this as if it's okay to have a general theory and a practical way of applying it -- but that's not okay in this particular domain, as ought to be obvious. — Srap Tasmaner

I don't see what's obvious, or what particular domain you're referring to.

A large part of all critical rationalism, including mine, is that there's a lot of freedom that's rationally permitted in the epistemological process, something I'd think Isaac and Banno would like. Using the epistemological-deontological analogy again, we normally recognize it as a crazy extreme to either say that every action is either mandatory or fobidden, nothing merely permitted but omissible; or conversely to say that absolutely anything goes and there's nothing at all that is mandatory nor forbidden, everything is permitted and omissible. I'm applying that same standard to epistemology as we ordinarily do to deontology, saying that there's a lot of the process where you don't have to do it one way or another, you can do it however you like, and so long as you stay within the wide bounds of the few things where it does matter that you do it one way instead of another, you'll be fine.

Point being, the fact that I haven't specified exactly how to do every step of the epistemological process is a feature, not a bug. I'm not trying to give mandatory procedure for every "what do I do now?" question that comes up in every investigation. For a lot of those questions, the answer is just "try something, anything", and then if that doesn't work out, the parts of the procedure that are specified will eventually tell us that.

For instance, how are the background assumptions and theoretical commitments in your big conjunction ordered? Order doesn't matter for conjunctions. In what order are they examined? Is there a method, or is it more like the random 'fishing a belief out of a bag' I had above? — Srap Tasmaner

It's like "fishing out of a bag", but there's a rough natural order to even the process of fishing something out of a bag. You reach in blind, not knowing what's in the bag or aiming to grab any one thing in particular, but you're more likely to seize onto one of the largest things in the bag first, and only after all the bigger things have been pulled out will you end up grabbing the tiny pebbles and grains of sand in the bottom of the bag.

And what does it mean to examine a background assumption and see if it holds? Is that a logical process or is investigative, gathering more information? — Srap Tasmaner

A little bit of both. Reach in the bag of assumptions and grab the first thing you find -- probably some big obvious thing. Ask yourself, "without this, would I have expected these results?" (e.g. "if there were dirt on the antenna, contra my implicit assumptions, would I expect to see this signal?") If no, put it back and fish something else out until you get a "yes".

If yes, look for something that would test the new set of assumptions. (e.g. "do I see dirt on the antenna, as I would expect to if I thought there was dirt on the antenna?"). If the test is successful (i.e. you don't see anything unexpected anymore), then you're good to go for now.

If the test fails (e.g. you don't see dirt on the antenna, as you would expect to if you thought there was dirt on the antenna), you could start fishing around the bag of assumptions for something that would explain that observation, or you could fish out a different assumption to explain the first unexpected observation instead.

Which path you go depends on what the next biggest thing you grab onto when you reach into that bag of assumptions is. (E.g. if "there's not radiation coming from every direction in space" comes up first, i.e. with less digging for deeper, harder-to-find assumptions, before "dirt can't be invisible", then you try eliminating the first one before you resort to the second).

Pfhorrest

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum