Comments

-

A hybrid philosophy of mindA problem completely avoided by not using terminology regarding psychological phenomena to describe non-psychological phenomena. Put it this way: a horse is just a bunch of physical stuff reacting to and acting on a bunch of other physical stuff, and everything is like this. So everything is a horse? No. Psychological phenomena regard brains. It doesn't matter if there's no fundamental difference between a brain and a bowl of soup: it's a classification for specific kinds of things (or behaviours: to be is to do). — Kenosha Kid

I’m mostly using psychological terminology for phenomenal consciousness just because that’s the terminology already used for it, but I can see the historical reasons for its use, just like I can see why quantum mechanics talks about “observers” that can just be inert objects with no brains. It’s talking about things in their capacity to fill a role that we also can fill, and which we tend to associate with our minds. Extending “mind” (or “consciousness” or “observation”) in that sense to everything, even things without brains, is just acknowledging that this capacity that we initially thought was special to us brainy things is not so special; that it’s something else about us brainy things that makes our version of that common feature special.

Being itself is purely functional though, isn't it? You went to pains in previous threads to establish that there is no real distinction between to be (i.e. to have a bundle of properties) and to do (i.e. to have the potential to behave a certain way). Seems odd now to insist on a distinction between emergent properties and emergent function. — Kenosha Kid

I’m not trying to do that, and I don’t see how you can read that in to the passage you responded to.

There's stuff in between this and strong emergence. Thermodynamic properties of gases in a box are just statistical, large-scale descriptions of fundamental particulate behaviour. However, there is such a thing as collective behaviour. A phonon is an example of this. While phononic behaviour is just motion, you need at least two interacting bodies for these particular modes of motion to emerge. Likewise, while chemical bonds are just modes of electrostatic attraction, they are only possible when you have two or more atoms. There's important stuff between statistics and magic (strong emergentism). So the difference between the thermodynamics of gases, liquids, and solids is derivable but not comprehensible in terms of the dynamics of individual atoms: you have to consider at least two (often more) of something before some behaviours are possible. — Kenosha Kid

Okay, I have no objection to that. That is still weak emergence, in that if you modeled the underlying system that that behavior emerges from, you would automatically model the emergent behavior (as in see that behavior emerge in your model; not that you would have a higher-level model of it). I don’t see what bearing that has on phenomenal conscience.

Why are you assuming physicalism to be the case? — RogueAI

Because this thread is a followup to another thread where I argue for a kind of physicalism. -

A hybrid philosophy of mindThanks for the response!

I think the short answer to both of your questions lies in the ontology of my web of reality, wherein it's explained how I view experience and behavior as two ways of looking at the exact same thing, interaction.

Experience only "is not anything to do with any behavioral properties of a thing" in the sense that you can't tell whether a thing has phenomenal consciousness or not based on what behavior it exhibits. But on my account, experience plays a definite causal role in every behavior of everything: the experience of each thing is the input into its function which prompts its behavior as output. Of course, even non-panpsychists accept that there is some input into things that prompts their behavior; the only novelty on my account, so far as that goes, is to identify that input that nobody denies the existence of with phenomenal experience itself.

Every domino experiences the forces that prompt it to fall over, in one sense or another of "experiences"; I'm just saying that that sense in which a domino can be said to experience the force of another domino hitting it is the same sense, or at least a part of the same sense, in which we experience the force of things hitting us. The difference between the domino and us is that we do a lot more than just absorb the momentum of a thing that hits us and change our bulk motion in response; we're complicated things that have a bunch of complicated internal reactions to things hitting us.

And those complicated internal reactions build up to our unified experience in the same way that our behaviors build up from the behaviors of our constituent atoms, etc, because experiences and behaviors are two ways of looking at the same thing, on my account. I don't see any combination problem in philosophy of mind, at least no more than one could posit a combination problem in ordinary physics: electrons do certain things, sure, but how is it that the behavior of a bunch of electrons adds up to the behavior of the solid-state electronics with which I am composing this message? The actual answer to that is a complicated one, but it's not a philosophical one; it's just an account of how signals pass into one thing as its experience and out of it as its behavior which is in turn the experience of another thing that has another behavior in response, and the aggregate inputs and outputs from the aggregate of those things are their experiences and behaviors. We generally see no problem with this on the behavior side of things -- the behavior of my computer is the aggregate of the behavior of a bunch of electrons, etc -- and I see experiences as literally the same events as behaviors, just viewed from a different perspective, and so no more problematic than the behaviors are. -

The Useless Triad!No, I mean that even if I believed that there existed such a god, I could not find hope in that possibility, because of the problem of evil.

An all powerful and knowledgeable being must not be all good, or else must not be sufficiently knowledgeable or powerful even if it is very knowledgeable and powerful, because if there were a sufficiently knowledgeable, sufficiently powerful, and sufficiently good being, there would be no excuse for the continued presence of bad things in the world, for it would have fixed them already. If it does not know that they need fixing, that would explain why they continue to occur; likewise if it is not able to fix them, or simply is not inclined to do so.

I know various theodicies have been offered for why an all-knowing, all-powerful, all-good being could allow "evil" to exist anyway. But even if any of those theodicies were true, if any of those excuses held water, still such a being would be no source of hope, even if it were positively known to exist, because the existence of such a being would then not necessarily have any impact on whatever hardships one might hope to escape by means of it; for some reason or another, it could still let them happen, as evidenced by all the hardship, the horrific pain and suffering and death, that does happen all the time. It doesn't really matter, for the purposes of something to hope for, whether or not any god exists, if for whatever reason or another it still allows genocides to occur and children to be sold into sex slavery.

One could argue that that is only allowed in the mortal life that we think is the entirety of the universe, and that we could all hope to move on after our apparent deaths to a better world somewhere in some larger true universe. But if that place is run by the same being we suppose is all-powerful over this universe, where for some reason or another he can't or won't stop all the horrific things that happen here, that leaves me with little confidence that he will be willing and able to do better somewhere else.

We could, I suppose, imagine that there is some all-good being in some larger universe within which what we know of the universe is something like a simulation, who is not actually all-powerful over this universe and cannot stop all the horrors that happen here, but does have the power to take people from here upon their apparent deaths and bring them somewhere that he does have the power to ensure that they get to live happily ever after. That is, I admit, a technical possibility. But it no longer resembles much the usual religious conceptions that real people actually look to for hope, and it seems to be more far-fetched than we really need to look, at least those of us who are not facing imminent death before more realistic possibilities might come to pass. -

The Useless Triad!the existential crisis as the rest of the godless — Hanover

Even if a god existed, that wouldn’t help with my kind of existential crises. -

Drug use and the law: a social discussionSo in essence, does legislation need reform? — Benj96

Yes.

Is there a better way to allow people to safely use drugs? Or — Benj96

Yes.

Or should they remain criminalised? And — Benj96

No.

And if so, what must be said of alcohol use or smoking? — Benj96

They should be treated the same as other drugs. -

The Minds Of Conjoined TwinsIt's like using using Darwin's theory — TheMadFool

That’s another good analogy.

There are a lot of mutations that are possible, caused by tiny random environmental factors, but most mutations either do nothing of note, or cause the mutated cell to die. If they don’t, the mutated cells usually malfunction and get killed off by other cells. It’s a very rare mutation that produces a lasting genetic difference... and most of those make no noticeable phenotypic difference. Those that do, again, are usually detrimental to the organism, and are quickly weeded out of the gene pool. So out of all the chaotic mutations that could happen, there is a very limited selection of phenotypic changes that can be introduced into the population; it’s not like a stray cosmic ray can just cause a horse to give birth to a pegasus. -

Penrose Tiling the Plane.I saw that video when it came out and found that penrose tiling fascinating. I don’t know why you think it sounds so wrong but I look forward to discussion about it with people more knowledgeable than me.

-

The Minds Of Conjoined TwinsIf we do attempt to complete the analogy, the content of the hard drive should stand for brain function but any changes in the fine structure of the hard drive will produce a corresponding change in the contents of the hard drive. — TheMadFool

The content of the hard drives is analogous to mental content — your thoughts, beliefs, feelings, etc. That stuff can and does change, which is the whole point here, accounting for origins of that change. The overall function of the brain though, like the overall function of the hard drive,

remains the same; those big features are relatively fixed and not easily altered. -

The Minds Of Conjoined TwinsYou mean to say you can predict the climate and not the weather? Any references to support your claim? — TheMadFool

Some top Google results:

https://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/noaa-n/climate/climate_weather.html

https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/news/weather-vs-climate

Also, kindly explain the analogy in more detail. What aspect of our minds is the climate and what aspect of our mind is weather? — TheMadFool

Someone else already gave a great illustration with regards to a hard drive earlier. The magnetization of individual bits on a hard drive can be completely different, but the whole structure of the hard drive remains that of a hard drive. The magnetization of individual bits can change drastically and unpredictably over time, like weather, but still the general overall structure of the drive remains the same, or only changes very slowly, like climate.

So I can't know what the microstructure of my hard drive will be like tomorrow, what with all the many crazy processes always changing that; but I can be pretty sure it will still be a hard drive a year from now. Likewise, I don't know for sure it won't rain here tomorrow -- this is the time of year when it starts to rain around here, but exactly when the first rain will be is hard to predict -- but I can be virtually certain that it will not rain at all next July, or the July after that, etc, because raining in July is just not something that can happen here.

And likewise, brains have a general structure to them that is going to be the same no matter what, barring traumatic injuries. But the microscopic brain states can change radically and unpredictably, and with them the mental states that they encode. Yet there are limits on the kinds of mental states that be had too -- you can scarcely more be "a little bit theist" than you can be "a little bit pregnant" -- so all those variations on brain microstates just influence how likely you are to end up in one of the fewer possible mental states, in such cases. -

Things we can’t experience, but can’t experience withoutLike vectorizing a raster image. I have very similar thoughts about that that I plan to write more about for an upcoming thread about epistemology.

-

Things we can’t experience, but can’t experience withoutThanks, that’s very encouraging to hear!

-

The Minds Of Conjoined TwinsYou're focusing on minor differences and ignoring major similarities. — TheMadFool

Weather and climate again.

It’s very hard to tell exactly what the weather will be like on a particular day even one month away, but I can guarantee you there will be no rain in my hometown on any day in July ten years from now. -

Donald Trump (All General Trump Conversations Here)https://news.yahoo.com/taking-page-authoritarians-trump-turns-151748832.html

Apparently Trump wants the State Department to release full unredacted versions of all the emails from Hillary Clinton's private mail servers to the public.

The private mail servers that were such a big deal because classified information stored on them might get compromised.

Compromised as in, made available to people without proper clearance to see it.

People like the general public.

Whom he is now ordering all that information be released to.

What? -

Atheism: A Story of Teenage AnguishThe seconds do not admit that there may be something above their experience. — smartguy

Or do not admit of things that are either beyond all possibility of anyone’s experience, or else contrary to experience.

All claims about God are either meaningless (they tell you nothing at all about what you should expect the world to seem like), trivial (they amount to nothing above and beyond things even atheists would admit), or demonstrably false (contrary to actual experiences people have and can replicate). -

Is “Water is H2O” a posteriori necessary truth?I think that the meaning of words is a posteriori, and analytic, but that necessity tracks with a priority, not with analyticity. Given the a posteriori fact about what “water” and “H2O” mean, it is analytically, a priori knowable, and thus necessary, that water is H2O. But it is a posteriori, and so only contingent, that “water” and “H2O” refer to the same thing.

It’s like how it’s not necessarily true that all bachelors are married IF “bachelor” just means “someone who lives like Bachus” rather than what we usually use it to mean. -

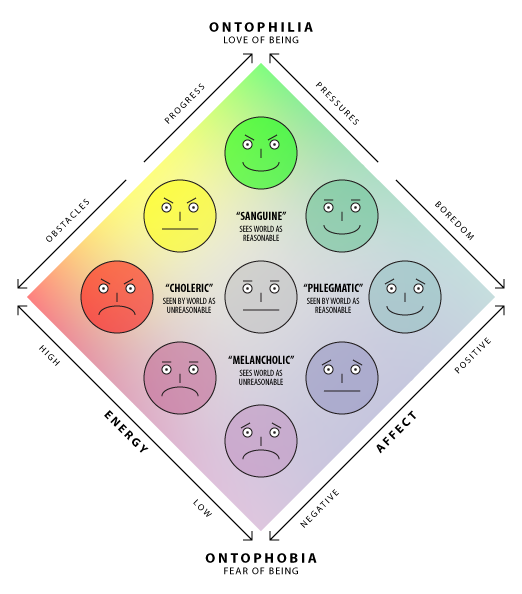

TempermentsI feel like I should add that my use of the four temperaments above is not so much as character types, as they are moods. I found myself cycling through high and low energy / positive and negative affect moods, and graphed that in prep for talking to a therapist, then later realized the four corners of that mood spectrum are basically the four temperaments.

-

Donald Trump (All General Trump Conversations Here)The who live in the borough — ssu

That may be the etymology of the word but you know that’s not its meaning in this context. In this context it means the capital-owners, in contrast to the laborers.

Never heard of the Petite bourgeoisie? — ssu

You contrasted the bourgeoisie with the elites. If you had instead contrasted the petit bourgeoisie with the bourgeoisie proper I would have agreed with you. I think Marx unfairly ignores the true middle class that he ought to be championing, those who have capital enough that they don’t have to labor extra to service debt, but not so much capital that they can profit from just owning it and have others do their work for them. Owner-operators = employee-owned businesses. That should be the ideal he wants to elevate the proletariat to. -

Donald Trump (All General Trump Conversations Here)Normality? — StreetlightX

"Normality" is relative. In one sense, things have never been "normal". In another sense (the one I take Punshhh to be using here), "normal" is just the status quo ante Trump. And there's a whole spectrum in between. -

Donald Trump (All General Trump Conversations Here)So apparently QAnon has been largely spread by the senior VP of technology at Citigroup.

At least he got fired for it. -

TempermentsI accidentally re-created the four temperaments in my own self-analysis, which inclines me to think that there is some conceptual use to them.

Here's the chart I was making about myself back then, that I've since adapted for general philosophical use:

-

Donald Trump (All General Trump Conversations Here)bourgeoisie as a willing partner of the elite — ssu

The bourgeoisie ARE the elites. -

The web of realityYeah pretty much, though I think the underlying reality is agnostic to QM interpretation, as they work out to equivalent results: from an a given observer's point of view it's fine to talk of wavefunction collapse, even if from an outside perspective that observer just entered a superposition along with what they observed.

(This is a common trend in my philosophical thinking: a lot of supposedly contradictory things work out to the same thing in the end, and the seeming contradictory perspectives are just different, equally valid ways of looking at the same underlying reality. See for example the earlier notion of a true solipsism just being equivalent to the self being part of the world. Or I guess the whole topic of this thread, where phenomenalism, which is like idealism, boils down to the same thing as physicalism, which is like materialism, even though materialism vs idealism is nominally a clash of opposites). -

The web of realityThe human hasn't done the observation yet, so the human isn't entangled with the electron / hasn't collapsed its waveform / hasn't split into multiple versions yet. But the Higgs field already has. It's Wigner's Friend, where we are Wigner and the Higgs is our friend.

-

The Minds Of Conjoined TwinsI understand the significance of differences in experience for how we turn out to be down the road but conjoined twins don't have that luxury. They're stuck to each other, remember? — TheMadFool

Yeah, the left-or-right thing isn’t meant to apply to the twins, it’s just a clearer example of the butterfly effect. A tiny insignificance change can snowball into a large difference through unpredictable complications. Likewise, tiny differences in the two twins’ brains compound over time into larger different between their brain-states. We would still expect a lot of similarities of their brain states, because of their shared experience and genetics, but this allows for enough differences to explaining why they aren’t exactly the same person despite those similarities. -

The Minds Of Conjoined TwinsSo, is it fair to say that the belief your espousing in this thread is ultimately mood-based? Why are you trying to argue then? — TheMadFool

Moods are just an example of a subtle non-rational brain process that can go on to influence your life in the future. They’re not at all integral to the point I’m making.

For another example, say you’re on a walk one day and at a fork in the road you have to go left or right, without any real reason for either. One of those choices will lead you to meet a person who will become a short-time acquaintance of yours through whom you will meet someone else who will introduce you to a new circle of friends among whom you will meet your future spouse with whom you will have many deep conversations that will heavily influence your opinions on things like theism or atheism. If you turned the other way on that walk, your future state of mind would have turned out completely differently. And whether you felt inclined to turn left or right is the kind of thing that could be influenced by tiny physical differences, or more likely built up to by an accumulation of consequences of tiny physical differences in the same way that your future beliefs were built up to by an accumulation of differences based on whether you turned left or right. -

The web of realityIf this division is arbitrary then you've not defeated solipsism by any means other than say saying 'let's not' (which, incidentally, is my own argument against solipsism). — Isaac

I don't pretend that my rejection of solipsism is very much more than "let's not", albeit with pragmatic reasons why it's more useful to "not".

Earlier upthread I even wrote already:

In the end, identifying the world with oneself is no different than identifying oneself as just a part of the world, which is uncontroversially true. — Pfhorrest -

The web of realityThe difference between a cup and...what shall we call it...the experienceability of a cup? - — Banno

There is no difference between those on my account. The existence is the cup is consists entirely of the potential of certain experiences.

That potential of certain experiences vs anyone actually having those experiences is the difference I mean. The existence of the cup doesn't consist of (or depend upon) someone experiencing a cup. But it doesn't consist of anything that is not some kind of potential for experience. -

The Minds Of Conjoined TwinsYou mean to say that beliefs are dependent on one's mood. — TheMadFool

Not directly. But they're dependent on previous beliefs, which are dependent on previous experiences, which are dependent on previous choices, which are dependent on previous moods. It's not as simple as you want to make it out, so as to easily refute it.

The brain is highly structured, and not chaotic in the sense that people are predictable to a fair degree. They sleep at certain times, they have certain habits such as tea or coffee, certain opinions that are so we'll rooted that no amount of conversation can change them, etc. This is not typical of a chaotic system. Too predictable. — Olivier5

Long-term climate trends are also highly predictable and regular, but weather is very chaotic. I mentioned this comparison in my first post in this thread. -

Donald Trump (All General Trump Conversations Here)Are we seriously entertaining whether Trump knows what "stand by" means? A native English speaker? — Benkei

You have heard him speak, right? He can barely get through a single sentence without fucking it up one way or another.

I'm not saying that his idiocy is any excuse for his actions, but he is clearly either a genuine idiot or else really good at pretending to be one. I'm not at all optimistic about Trump's character, but it's genuinely hard to tell sometimes whether something awful he says is due to maliciousness or stupidity.

Sometimes he even says good things, apparently being too stupid to realize that that's contrary to his party platform; promising universal health care in 2016, for example, or suggesting a gun-control-first-ask-questions-later approach shortly after his election.

I think his utter amorality stems from an inability to know (or care enough to figure out) what is genuinely good or bad. Instead he just goes with whatever gets him praise, thus being easily manipulated by whoever will allow him to feel good about himself. Which, to be clear, is a bad way of conducting oneself, not a moral thing to do.

But it's behavior I see in people like my own parents, and I imagine is behind a lot of the people who vote for Trump too; the kind of people who believe whatever crazy thing they read on Facebook, if it allows them to feel like they're the good people and that good people like them are going to win over the bad people, who by definition aren't like them, because they're the good people.

It's a horrible way of thinking and living that's done horrible things when elevated to the highest office, but it's an all-too-common way of thinking and living that I can understand and pity as much as it may disgust me. -

The web of realityThe basic criticism remains, If all there is, is experience, what remains of reality for you to call yourself a realist? — Banno

All there is is experienceability. I don't know why it's so difficulty to communicate this difference, between something being the kind of stuff that is available to be experienced, and something being actively experienced by someone.

On my account, there is a reality independent of anyone in particular experiencing it, but there is nothing about that reality that is not accessible to experience. -

The Minds Of Conjoined TwinsYou mean to say that if someone were to introduce me to atheism/theism, my response to it depends on variations in sodium ion concentration and sodium channel activation — TheMadFool

Probably not in that direct a fashion. But your response to the ideas of atheism or theism would depend heavily on your other life experiences, which would depend on previous life experiences, where those life experiences can be influenced tremendously by tiny choices you make, tiny variations in your mood, things that aren't such a clear black or white conscious choice but more something that you wouldn't be able to clearly state why you did one thing instead of another, you just felt like one more than the other; but those choices ended up giving you a different experience in your life, and that different experience in your life changed how you would react to the ideas of theism and atheism. And those tiny subconscious states of mind that can send you down one life path instead of another can be influenced by small changes in neurochemistry. -

The Minds Of Conjoined TwinsI can accept that the physical environment (temperature, humidity, air pressure, etc.) can vary quantitatively in ways that chaos in brains becomes possible a la the classic butterfly effect. However, if the physical environment has such an effect on the mind, we should be seeing a clear gradation in mind-types (gradation in beliefs, attitudes, etc.) with latitude, temperature being the most well-defined variable in physical environment. What I'm saying is the minds of people living in hot places should be different from the minds of people living in cold places. I haven't come across any scientific study that makes such a claim. Perhaps something worth investigating. — TheMadFool

You seem to be thinking of the brain as though it were a gas, with its processes predictably correlating with the things that you list (temperature, humidity, air pressure, etc). That has nothing to do with chaotic things like the butterfly effect; in fact such a correlation is contrary to them. The brain as a chaotic system would be one in which, say, a single sodium ion either does or does not make contact with a neuron because of some small physical difference, and then that neuron does or does not fire in accordance with that, and then all of the neurons that would fire in response to that one firing either do or do not fire in accordance with that, and then all the neurons that they would trigger to fire either do or do not in accordance with that, and pretty soon you've got a vastly different state of which neurons are firing, and so what the brain overall is doing, all because some trivial physical effect either did or didn't inhibit the motion of a single sodium ion. -

Donald Trump (All General Trump Conversations Here)Libertarianism in the United States is generally associated with the right. There are some left-libertarians, like me, but we’re either a minority or terribly underrepresented. Left-libertarians aren’t usually calling to just destroy the government and let the pieces fall where they may, but to displace the government with something better.

-

The web of realityAre there philosophers who hold that "actual concrete reality" is transcendental? — Gnomon

They don’t usually call it such because they’re usually pre-Kantian, but basically all representative realism is transcendental realism in Kantian terms, because it holds that phenomena are just ideas, not real, they only represent what is real.

How would you classify neuroscientist Don Hoffman's Model Dependent Realism? — Gnomon

It sounds like a kind of empirical realism to me. -

Donald Trump (All General Trump Conversations Here)Would you consider Timothy McVeigh a right wing extremist? — BitconnectCarlos

He is generally considered one.

Pretty much all domestic terrorists in the US have been. -

The web of realityThere is a view that true statements must in principle be confirmable. But that's not really in line with what you're saying either. — frank

Nope, my view is that statements must be falsifiable. That’s exactly why I reject all claims of unobservable things: they could not be falsified.

And if they were true, their truth would make no difference whatsoever to us, so such claims are effectively empty. They add nothing. Appending a claim about unobservable things to your view of reality is like adding zero to a sum. -

The web of realityYes, obviously with the 'in principle' caveat: — Kenosha Kid

Yes, of course.

I guess I'm just not seeing the relevance of masslessness. — Kenosha Kid

It's only massless particles that are lightlike, and so have an existence that (from their frame of reference) consists entirely of the interaction between what emitted them and what absorbed them.

This might be off topic, but one thing occurs to me. When we interact with anything, it is overwhelmingly electromagnetic in nature. When we see a tree, photons emitted by that tree are destroyed in our eyes: this is sight. When we feel the tree bark, virtual photons emitted by the charges in the bark are destroyed by charges in us: this is touch. We never destroy charges, only the emissions of charges or systems. — Kenosha Kid

Yes, that's something I've been assuming as background knowledge in this thread. Glad you explicitly pointed it out though. :-)

I guess that's why I find the primacy of mind and experience in your language (and I think that you do not distinguish between the experience of a person and of an electron) a bit of a barrier. — Kenosha Kid

I see the experience of a person as a special subset of the experience of an electron. "Experience" here can be taken as equivalent to QM "observation". When a human observes something, they are still doing the thing that an inert object merely interacting with it does, that causes (or is) wavefunction collapse or entanglement or the splitting of worlds, however you want to interpret it. But a human is also doing a lot of other stuff that an electron isn't doing. That other stuff isn't metaphysically important here, it's just brain function, more complex information processing, but it's a thing humans do that electrons don't.

In your literalist interpretation of the creation/annihilation operators of QFT, it is the fields that destroy electrons directly. (The Higgs mechanism is the destruction of an electron with one isospin followed by the creation of another with the opposite isospin. The motion of an electron is the destruction of the electron at one position followed by the creation of an identical electron at another.) — Kenosha Kid

Yes, although not all motion can be reckoned like that -- specifically, the lightlike motion of massless particles can't, because from their frame of reference they travel zero distance in zero time, so motion is irrelevant. It's only massive particles, which already consist of a "blending" of several more-fundamental massless particles through their constant annihilation and recreation by the Higgs field, that can be construed as moving through a series of annihilations and recreations; because it's precisely that series of annihilations and recreations that gives them mass, and makes their motion slower than light.

Somehow this makes me think of the sort of equivalence between experience and objective reality you're getting at without necessarily being the sort of thing you had in mind. — Kenosha Kid

It sounds like you're on basically the same track as me, to me. :up:

If you are not an idealist, then you must hold that there is unexperienced information. If you hold that all information is experienced, as you seem to be saying here, then your position is idealist, not realist. — Banno

I am not saying that all information is experienced, but that all that exists is the kind of stuff that can be experienced -- whether or not it actually does get experienced. That kind of stuff can be characterized as information.

My own worldview is best defined as both Empirical Realism and Transcendental Idealism — Gnomon

In Kantian terms, any empirical realism is also a transcendental idealism, and conversely any transcendental realism is an empirical idealism.

An empirical realism is a view that takes the stuff we can observe, phenomena, to be the stuff that is concretely real, and conversely the transcendental, unobservable stuff, the noumena, to be only abstract ideas. My account of the "objects of reality", the nodes in the "web of reality", being abstract mathematical functions, which we infer from their behaviors that we experience in response to other behaviors they experience, accords with this.

An empirical idealism, on the other hand, would hold that the kind of stuff we can observe, phenomena, are just abstract ideas in our minds, and conversely that actual concrete reality is the transcendental, unobservable stuff, the noumena, that underlie those phenomena, and which those phenomena represent to our minds. That's a view that both Kant and I reject.

Science does not give us any evidence that all real things can be experienced, so how did you arrive at that conclusion? — frank

From the practical reasoning that if we ever take any claims to be beyond questioning, we simply stop searching for the truth, and so are likely to never find out if we are wrong, so we must not ever take any claims to be beyond questioning; and that claims about things that are not subject to experience cannot ever be shown wrong (because we could not tell whether or not they were, because we have no experience of them at all), so we could only take such claims on faith, without the ability to question them; so we must not ever entertain the possibility of things that are in principle beyond all experience, for in doing so we would be giving up our pursuit of truth.

And it definitionally cannot be shown that there does exist something beyond experience, because to show that would be to make it available for experiencing, so we don't have to worry about ever finding our assumption that there is not to be wrong. -

Donald Trump (All General Trump Conversations Here)There's a group Proud Boys, that goes out of its way to deny it's white supremacist is then identified by Trump as white supremacist — Benkei

To be completely fair, Trump was asking "what do you want me to call them? Who do you want me to..." and Biden suggested "Proud Boys". It is hard to make out in the audio because everyone is talking over each other, but Trump didn't pick the Proud Boys to name himself.

And as I said earlier, it seems to me like a coin toss whether Trump was just too stupid to know the difference between "stand down", "stand back", and "stand by", or whether he was using obfuscating stupidity to send a coded message. It is plausible, but maybe a little too convenient, that he was trying to do as he was asked, and just fucked it up royally. In any case, the Proud Boys themselves took it with the worst possible interpretation, so whatever Trump's intentions, the effects were the same.

Pfhorrest

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum