Comments

-

The Inequality of Moral Positions within Moral RelativismAnd how do you carry out this criticism and effort? By following rules. — Isaac

Which I in turn criticize and reformulate, ad infinitum. -

What School of Philosophy is This?I have, actually, but you haven't paid attention. — Olivier5

You've provided examples of disagreements, where each side of the disagreement has some argument, appealing to something that they value. But that's not evidence that each side is equally (in)correct. And now we're going in circles, because that's what I said before that got us to here. -

What School of Philosophy is This?These are all means of reaching conclusions about moral differences which are non-violent, seem to work for the most part — Isaac

...so long as people accept their outcomes as legitimately normative, i.e. as morally correct, as telling us what we ought to do, and not just as "what those people think, but why should I care about that? It's not like they're actually right or something. That's just, like, their opinions, man."

And except for all the times when even people who want to take them as legitimately normative still find them outputting prima facie absurd conclusions (a white majority vote to strip all black people of their rights... hey that's democracy for you!), which is evidence that that (particular formulation of that) principle or procedure is not, actually, legitimately normative, i.e. morally correct, and it needs some adjustments or refinements to eliminate problems like those. -

The Inequality of Moral Positions within Moral RelativismIt seems to me Pfhorrest is a meta-ethical relativist, as long as he thinks that everyone has, in fact, the same terminal goals such that rational argument can always in principle result in agreement. — bert1

No, I just “have terminal goals” (i.e. take morality to be something*) that involves the suffering and enjoyment, pleasure and pain, of all people.

Whether or not other people actually care to try to realize that end is irrelevant for whether that end is right. Some people may not care about others’ suffering, for instance; that just means they’re morally wrong, that their choices will not factor in relevant details about what the best (i.e. morally correct) choice is.

*One’s terminal goals and what one takes morality to be are the same thing, just like the criteria by which we decide what to believe and what we take reality to be are the same thing. To have something as a goal, to intend that it be so, just is to think it is good, or moral, just like to believe something just is to think it is true, or real. -

Can Life Have Meaning Without Afterlife?if you are unhappy to begin with, life will seem to lose its meaning. The opposite is also true: when you are happy, you tend to see the meaning in your life. Consider that happiness might be the cause, and meaning is the effect. If you can find other ways to increase your happiness, the fact that life is finite should bother you less. — Bird-Up

:up: :100: :clap: -

What School of Philosophy is This?For one thing, you haven’t provided any evidence that one side is wrong. — Olivier5

And you haven't provided any evidence that neither is.

I don't think it can be conclusively proven one way or another whether objectivism is true or not, without begging the question. So it all boils down to the pragmatic choice: of whether to proceed as though it is, and try to reach a conclusion that accounts for all of the reasons everybody brings to the table; or else proceed as though it's not, and just throw up our hands and say there's no resolution to be had, so much for reasoning, now we just fight I guess and who ever wins "was right". -

The Inequality of Moral Positions within Moral RelativismJust like intersubjectivity is not objectivity, but seems like it. — bert1

I've never really understood the supposed distinction between these two. It makes it seem like objectivity is being conflated with transcendence, like the objective is something completely beyond access. As I understand it, the objective is just the limit of the increasingly intersubjective; the maximally intersubjective (that we'll never reach, but can get arbitrarily close to) just is the objective. Any "objective" beyond that is incomprehensible nonsense, and so not worth speaking of. -

The Inequality of Moral Positions within Moral RelativismSomeone who follows the rules but without any feeling. — Isaac

I don’t just follow the rules blindly, I criticize the rules and make a great effort to be sure as I can that they really are the correct rules. NB that as I’ve said before I am firmly against absolutism, thinking that certain kinds of acts are always right or always wrong regardless of context; context matters a lot. But also, the ends don’t justify the means.

Those are the extremes that the usual types of normative ethical theory end up in, which is why I reject them both and try to find something better. And yeah, if someone just blindly followed those usual theories to their logical conclusion it would lead to atrocious ends. Kant would have you tell the Nazis you’re harboring Jews because lying is always wrong. Mill would have you harvest the organs of one healthy patient to save five dying ones because that end justifies those means. Those absurd conclusions that a robot blindly following such rules would reach is a demonstration that those rules are faulty.

Thinking in terms of how to program a robot is thus very useful in figuring out what the correct normative ethics is, and likewise, the correct normative ethics should lead an emotionless robot or psychopath to behave even more morally than someone just doing what they feel is right because they feel like it.

In the mean time, it’s still great that most people usually feel like doing something that’s usually mostly alright. But that still frequently goes wrong, to one degree or another. Ethics is all about thinking through what would be right more reliably than just that.

Although nearly all replies are just arguing against moral relativism, I just wanted to show that normative relativism is not the same as moral relativism — Judaka

Sorry for derailing your thread more above.

NB though that the terms are “normative MORAL relativism” and “META-ETHICAL moral relativism“. They are both kinds of moral relativism, so if you want to distinguish between them you have to make sure to use the qualifiers, because neither of them is just the one and only “moral relativism”. -

What School of Philosophy is This?That depends on one’s value system. There is no objective answer to this question. — Olivier5

There is no right or wrong answer in this case either. It all depends on whether you value frankness over social ties, or vice versa. — Olivier5

You keep giving examples of different answers people might give to different morals questions and concluding that therefore nobody is any more right or wrong than anybody else. But it’s entirely possible, for all you’ve argued, that one side of such disagreement is just objectively wrong. Or that they both are, in different ways, and what is objectively right is something that’s not wrong in either of those ways.

Disagreement isn’t subjectivity. That’s the point at issue here. Pointing out more disagreements doesn’t constitute an argument to the contrary. -

What School of Philosophy is This?Yes. Not for the sake of your answer, but to help demonstrate that there us often no right or wrong answer. There's the answer given by Hillel, which you side with, and the one defended by Shammai. Different people see things differently, they values different things. Some are more diplomatic, others more frank. — Olivier5

You gave an example of a disagreement, but that in no way demonstrates that there isn't a right or wrong answer. There are frequent disagreements about facts either, but that doesn't mean there is no objective reality.

Let’s take a less obvious example: the policy response to the COVID pandemic has varied from one country to the next. On one side of the spectrum, some countris have imposed very strict lockdowns to curb the spread of the virus and avoid many deaths. This has created a big economic slow down. On the other end of the spectrum, other countries have not imposed any lock down, our of fear for the economy. In doing so they implicitly accept a certain number of COVID death as the price to pay to keep the economy running. That may sound heartless but it’s not, for them it’s just recognizing that people can die of poverty and hunger, too.

What would be your call, if you were president of your country? — Olivier5

Well a president doesn't usually get to make such unilateral decisions, but my choice would be to impose lockdowns to the extent necessary to avoid overwhelming the medical system ("flatten the curve"), and redistribute wealth from the rich to the poor to keep people from dying of poverty or hunger (something that should be happening anyway). If, in a counterfactual scenario, there somehow weren't enough actual resources to go around regardless of the distribution of nominal wealth (money), I'd say to make exceptions to the lockdowns as necessary to allow the production of necessary resources, so long as that results in fewer deaths from poverty than deaths from disease. (Or generally, results in less suffering overall).

In any case, I'd make all such decisions based on the advice of a variety of experts in different relevant fields, listening to arguments for and against different strategies, weighing the merits of those arguments against each other, and trying to brainstorm together creative new solutions that account for all the good arguments everybody has to make simultaneously. While remaining aware that my knowledge and judgement are imperfect and despite these best efforts I might still be making the wrong decision.

But a decision can't even be wrong if there isn't any such thing as wrong, just differences of opinion, none of them more right or wrong than any other. -

The Inequality of Moral Positions within Moral RelativismWell I would say both descriptive and meta-ethical moral relativism is true — Judaka

Yes, each later type of relativism assumes the previous types.

Descriptive: "People disagree about what's moral or immoral..."

Meta-ethical: "...and none of them are more or less correct than any others..."

Normative: "...so we should all tolerate each other's differences in behavior."

something like an A.I. without our biology could intellectually appreciate the idea of morality. — Judaka

Yeah, that's generally how I feel about myself.

I get emotionally upset about things that impact me directly, but I could, largely, ignore everyone else's suffering. Except that I think I shouldn't. I think the correct way for people to behave generally is to act in a way that minimizes the suffering of others, and I am a person so I should behave that way too; it would be inconsistent for me to do other than what I think people in general ought to do. Whether or not I feel like it isn't relevant, except inasmuch as my feelings might interfere in my doing what I think I ought to.

I've done right by people that I hated before, even though I'd rather have watched them suffer, because I thought that I ought to and I was able to override the feelings to the contrary. People who only do what's they feel is right because they feel like it seem unlikely to do something like that; if they want to see someone suffer, they'll invent a reason why that person "ought" to suffer to justify allowing it to happen, and not care whether or not that "reasoning" is consistent with their other reasoning about other people in other circumstances.

I'm not demeaning people having feelings that incline them to do things they ought to do. I'm very happy that people generally have feelings that more or less incline them to more or less usually do things they more or less ought to do, because most people don't think past those feelings. But their feelings can often lead people to do bad things instead, and I'd much rather that more people actually stop and think about what is or isn't actually the right thing to do, than just do what they feel like, even though it's good that they pretty often feel like doing things that are pretty okay. -

Moore's Puzzle About BeliefI was talking about two different forms of sentence:

S1: "P but X doesn't believe P."

S2: "X says P but X doesn't believe P."

You're talking about the first, S1, which is the form of the original sentence Moore was concerned with, and you're right in everything you say about that. That sentence is absurd in some way or another when X = the person saying it.

Ciceronianus was saying that the sentence is equally absurd whether or not X = the person saying it, but then he gave S2 as the form of the sentence. I agree that S2 is equally absurd no matter the value of X, but that's because it's a different sentence, and it's not really absurd at all. It's saying that someone says other than they believe; in other words, they lie.

If I were to tell you that "I say my dick is enormous but I don't actually believe it is", say in the context of me talking to women, I'd just be telling you that I lie about my dick size. I'd be telling you that I lie to them, not trying to lie to you in the moment right there.

That's a different sentence though than "My dick is enormous but I don't believe it is". That's absurd, just like the original Moore sentence, which is of the same form.

But "Bob's dick is enormous but he doesn't believe it is", of the same form as that, makes perfect sense. Bob is underconfident about his dick size. It's not absurd to say that about someone else, only about oneself.

But that's a different sentence than "Bob says his dick is enormous but he doesn't believe it is". That just means that Bob lies about his dick size, exactly like the sentence where I did, which is of a different form than Moore's sentence. -

Can Life Have Meaning Without Afterlife?Neither a finite life not infinite life have any more or less meaning than the other. Even if you had infinite life after this one (or if this one just went on forever), you'd still need to find, or rather make, meaning for it.

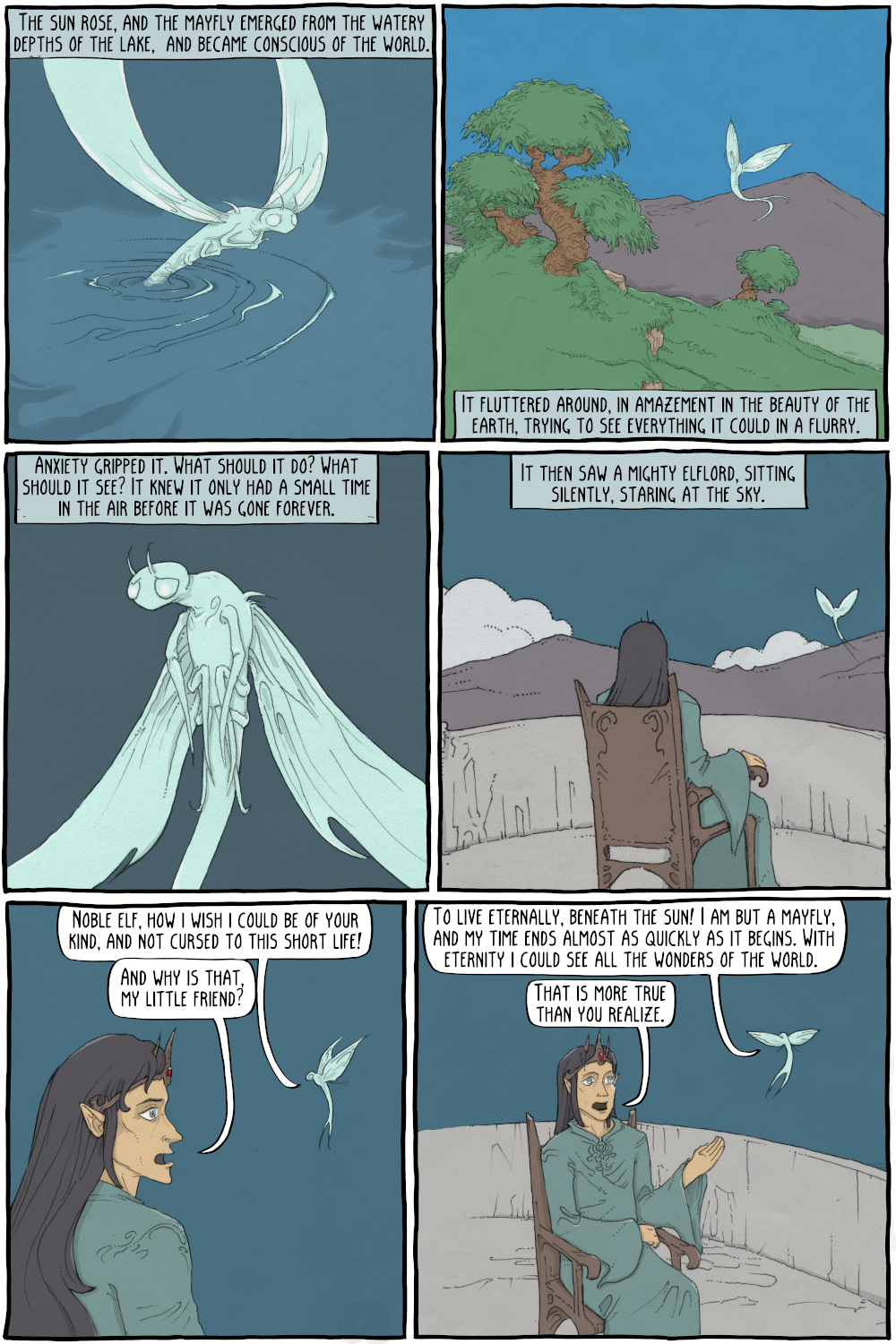

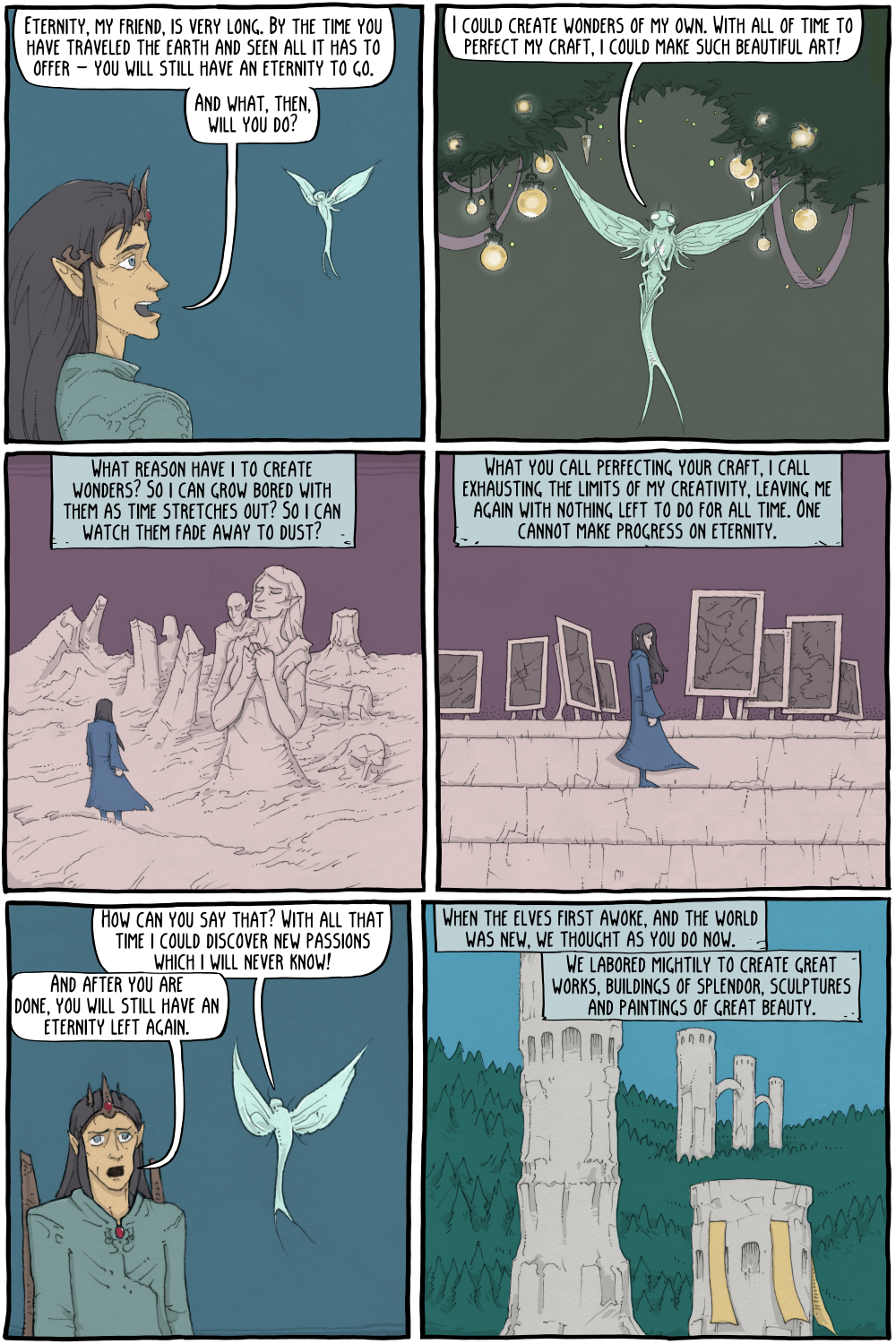

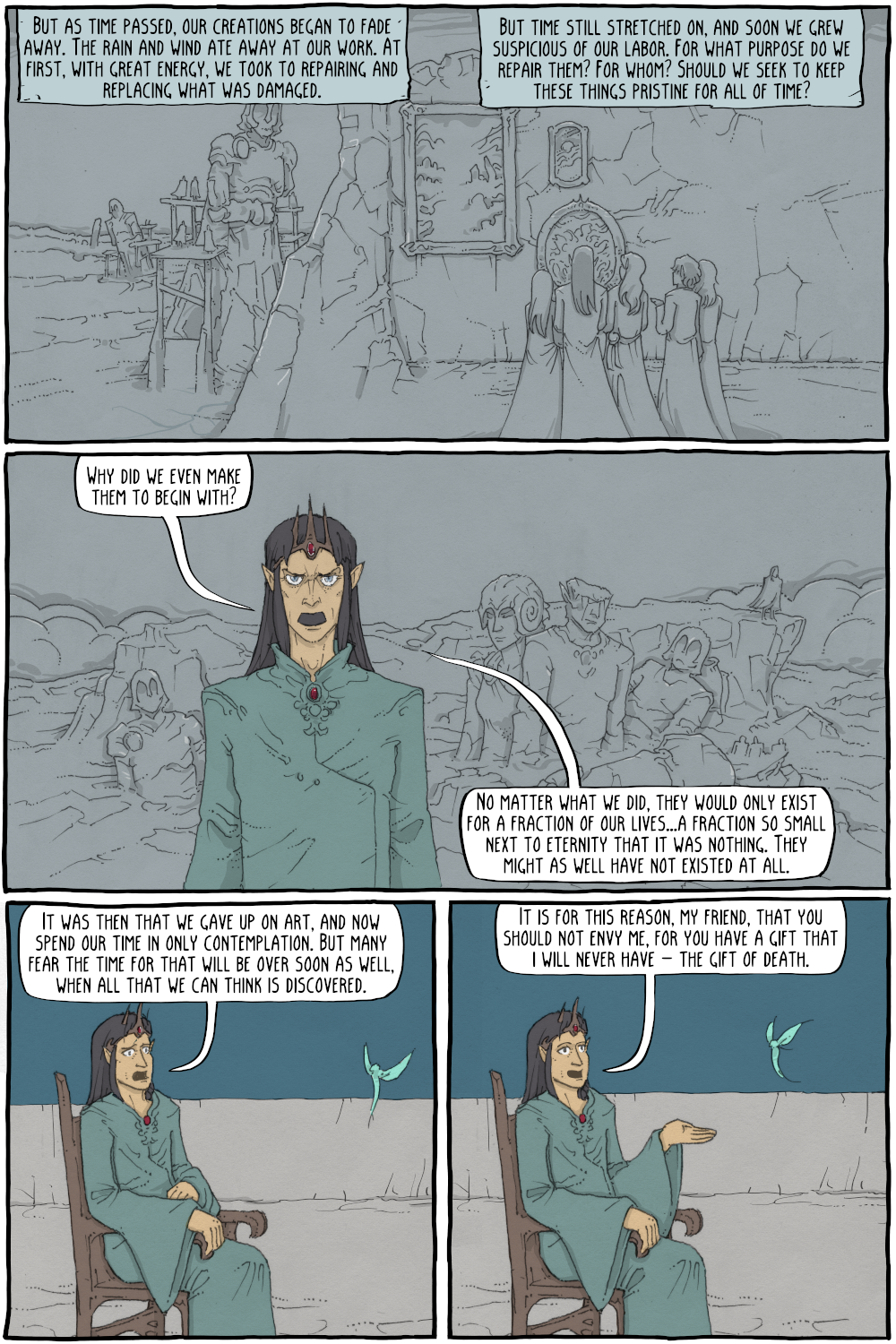

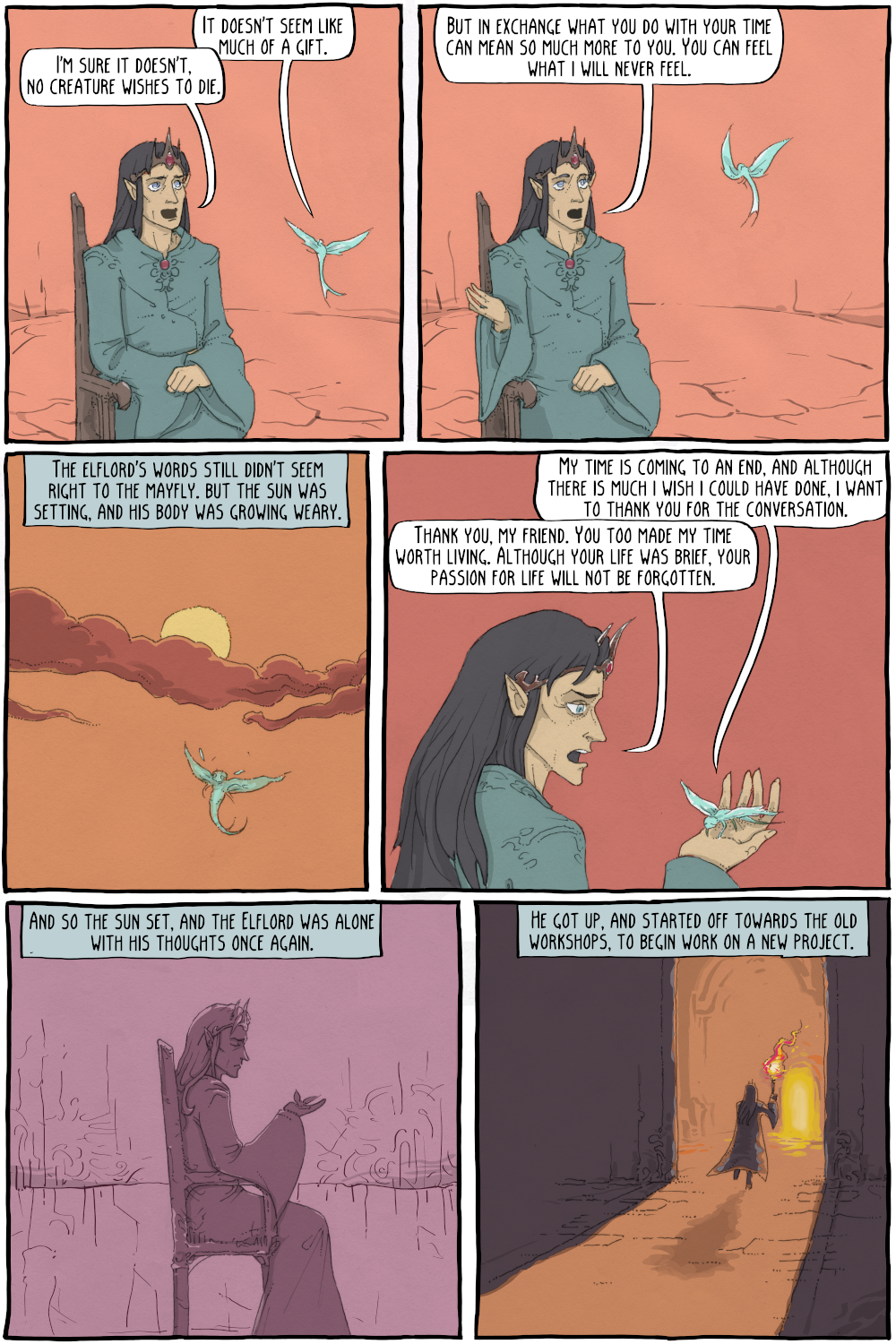

There was a great comic on this topic a week ago:

The Elflord and the Mayfly

-

The Inequality of Moral Positions within Moral Relativismmorality is not based on reasoning, a psychopath is not someone who thinks differently, they're wired differently — Judaka

Psychopathy doesn't have to have implications on behavior. Psychopaths can behave morally even if they don't have the empathy that drives people to behave morally.

I've wondered sometimes if I might have something in the direction of psychopathy. I rarely actually feel emotionally upset about other people suffering. I am able to tell how other people feel very well, and I intellectually do not want other people to suffer, but it doesn't actually hurt me emotionally to see other people suffer. (Normally. Most of last year, something weird came over me, and sent me into a crazy existential dread where I was constantly worried about the likely death to predation of every cute bunny I saw in the meadow, and things like that). 9/11 didn't faze me, for instance; "just another huge tragedy somewhere on the other side of the continent like happens all the time, now I have a job interview to get ready for" was my thought process that morning. (I was also too young to realize the geopolitical ramifications that would stretch beyond that one event, though).

I've often felt like people who only do moral things because of emotional reactions have a shallow, fickle sense of morality. I try to do what is right because I think it is the right thing to do. I try to figure out what is or isn't right to make sure that when I'm trying to do the right thing, the thing I'm trying to do is actually the right thing, and I don't end up some well-intentioned extremist. In contrast, people who only do whatever they feel is morally right, just because they feel like it, don't seem like people who are actually acting out of any kind of moral duty.

It's sort of the moral equivalent of people who believe things uncritically, just because they heard someone say it or read it somewhere and it seemed truthy to them. That seems to be most people, and doing what feels like the moral thing to do because they feel like it seems to be most people too, but both of those seem like a very shallow, fragile, easily corrupted and highly fallible ways to go about deciding what to think and what to do, in contrast to, you know... actually reasoning about these things critically. -

The Inequality of Moral Positions within Moral RelativismI can get behind the first sentence, not exactly what I would have said but whatever it's a reasonable attempt. The second sentence is clearly an interpretation of what to do as a result of the first sentence. If when I say I believe in moral relativism I am saying that I am advocating a "who am I to judge?" mentality then this is pretty annoying. Is this kind of cultural interpretation of relativism a component of the definition? — Judaka

Well, there are multiple definitions, which is why we've invented different qualifying terms to distinguish between them. That article you linked seems to be weird in that it lists the three different kinds of moral relativism correctly, but then also at the start and end talks about them like they're all the same thing.

It sounds like you are a meta-ethical moral relativist. If you say exactly that then nobody who understands the different kinds of moral relativism should think that you mean a "who am I to judge?" kind of attitude. But most people aren't going to understand the different kinds of moral relativism, and will think, like whoever wrote that article, that they're all the same thing: that acknowledging that there are disagreements (descriptive) means thinking nobody is more or less right or wrong than anybody else (meta-ethical) and therefore we ought to tolerate all our differences (normative).

You'll probably just have to clarify the difference between them and state which of them you support if you want to be understood correctly. -

Moore's Puzzle About BeliefIt doesn't say "I say it's raining" because "I" clearly is speaking, saying, that it's raining. It isn't necessary to say you're speaking when you're speaking. That in itself would be peculiar.

When someone says it's raining, they merely say that. They say nothing about themselves. The say something about the weather. — Ciceronianus the White

Right, so the original sentence isn't of the form "X says P but X doesn't believe P".

It's just of the form "P but X doesn't believe P".

The former form of sentence would not sound contradictory for any value of X, even oneself; it just describes someone who is lying, saying something they don't believe. I can easily say "I say P but I don't believe P"; I'm just telling you I'm lying when I say P.

The latter form of sentence doesn't sound contradictory for any value of X besides oneself, but then it does sound contradictory when said about oneself. I can't say "P but I don't believe P" without seeming to contradict myself, even though it's totally logically possible and non-contradictory that P might be the case and yet I might not believe it. If I say it about anybody else, the lack of problem there is clear: "P but Bob doesn't believe P" just means Bob is wrong about P. It's logically possible that I might be wrong about P too, so why does it seem so weird to say "P but I don't believe P" that nobody would ever utter a sentence of that form?

(Because saying P shows that I believe P, so if I'm simultaneously telling you I don't believe P, what I show and what I tell are in contradiction. While if I say the same thing about someone else, I show you what I believe but tell you what they believe, so there's no possibility of self-contradiction there, because the beliefs I'm showing off and the beliefs I'm telling about are different people's beliefs). -

The Inequality of Moral Positions within Moral RelativismNeither grounded nor relative?

One answer lies in considering ships at sea. — tim wood

For a moment I thought you were going to make the same analogy I do:

Don’t try to stand on the bottom. There is no bottom, the sea is infinitely deep. But that doesn’t mean you have to sink forever. You can just float on the surface, so long as you let go of anything that would pull you down.

This is a metaphor for falsificationism vs justificationism, and I think the same thing applies morally as it does factually. Everything and its negation is possible — morally speaking, it’s permissible — until it can be shown wrong. It is the possibility of showing wrong that makes for objectivity. -

The Inequality of Moral Positions within Moral RelativismWhat you're describing here is descriptive moral relativism (just basically a factual description of the world, yes, moral norms have changed and continue to change). When philosophers argue against moral relativism they're arguing against prescriptive moral relativism: The view that morality on a fundamental level is always to be viewed relative to something (usually to some time or place) and that other standards cannot be privileged over that. — BitconnectCarlos

A common criticism of moral relativism is that it demeans morality, it means that we have to be tolerant of other points of view on moral issues. — Judaka

There are more than just two things to be differentiated here. Besides descriptive relativism, there are also meta-ethical relativism, which is what Carlos is talking about (the truth or falsity of moral claims is relative), but also normative moral relativism, which is what Judaka mentions here (we ought to tolerate behaviors that our morals say are bad because our morals are just relative). You can be the former without being the latter, and you can also be very tolerant of other cultures and practices without being a relativist of any kind — in fact, many think normative moral relativism is simply incoherent, because that “ought to tolerate” seems to be a universal moral claim.

Take me for instance. I’m a moral objectivist, or universalist, and I think we ought to be very tolerant of a wide variety of behaviors, because a lot of things are just not morally relevant at all, and a lot of the remaining things vary widely in their morality by context, and it’s often very uncertain whether a particular context even is the one in which something would be immoral, and even if it is, we are often not in a position where it would be morally right to intervene.

So on my account people who do intervene in circumstances where it’s not their place, where they can’t be sure it’s wrong, because it might not always be wrong, or might not even be the kind of thing that could be wrong... those people are doing something morally wrong, by being thus intolerant of things that might be fine or are none of their business. They’re doing something objectively, universally morally wrong by being intolerant. -

Moore's Puzzle About BeliefThe sentence isn't "I say it's raining, but I don't believe it's raining", it's just "It's raining, but I don't believe it's raining." If you say "It's raining, but X doesn't believe it's raining", that makes perfect sense, unless X = yourself. The interesting question is why does it matter whether or not X = yourself.

My answer is because when you say "it's raining", you're not only telling someone ("impressing") about the rain, you're also showing something about your beliefs ("expressing") about the rain. If you say it's raining but someone else doesn't believe it, you're showing something about your beliefs, while telling about someone else's, so there's no room for contradiction. If you say it's raining but you don't believe it, you're showing something about your beliefs, while telling something to the contrary about them.

To get the same weird effect in talking about someone, you have to use a different sentence. You have to say something about what they say is a fact and about what they believe. You can't just say something is a fact and then say whether someone believes it, because that only has weird possibilities when the someone is yourself. -

Moore's Puzzle About BeliefI think Peirce would say, similarly, that we shouldn't pretend in philosophy that a paradox is presented by describing as true a statement which nobody would make about himself/herself, let alone make at all, in any circumstances which resemble what takes place in the life of humans. What we learn from such a fabrication, beyond the fact that it is clearly a fabrication (which can be determined with very little effort) can only be a fabrication itself. — Ciceronianus the White

My girlfriend similarly asked why anyone would say anything like the statement in question, and I said in response that they wouldn’t, because it would be such an odd thing to say, but the interesting question, what makes for the paradox, is WHY is it such a weird thing to say about oneself that nobody would ever say it, but it’s not at all weird to say about others? That difference is the origin of the paradox, and the thing that may be illuminating upon our understanding of language. -

What School of Philosophy is This?What do you say? — Olivier5

I’m not sure if you’re asking me about that specific scenario regarding the beauty of a bride? I would say she looks beautiful, but not because it’s sometimes okay to violate moral principles, but because “never lie” is not an absolute moral principle. For the most part I don’t endorse any simple imperatives like that as absolute principles: never do this, always do that, etc. Context totally matters. But we can still find patterns in which contexts which actions are good and which are bad.

trying to formalised common morality — Olivier5

We can always formalize anything. Formalizing morality is what ethics, moral philosophy, is all about. I am engaging in an ongoing discussion about that topic, and mostly just arguing against previous positions that go against “common sense” in some way or another, trying to come up with a position that allows for reasoning about morality without demanding that people do things that violate that “common sense”.

If sounds like you’re just objecting to doing ethics at all, to people thinking about what’s right or wrong in general rather than just... following their instincts and acculturation... and the law?

For one, because we already have the law, which fulfills that function, so you are reinventing the wheel. — Olivier5

What is the right way to form laws, and should everyone always obey every law? These are questions of political philosophy, which has its roots in ethics. I am giving answers to the questions in those fields, that I think are better than the answers others have given before.

common morality is inherently subjective, fluid and flexible, something which you go at great length to ignore, as if you were afraid of this inherent messiness of humankind — Olivier5

Subjective is not the same thing as fluid and flexible. I am very much in support of flexibility, as shown at the start of this post. Being opposed to subjectivity is something else entirely. You can agree that different things are right or wrong in different circumstances, without agreeing that the exact same event is simultaneously right and wrong to different people who judge it differently, just because they judge thus and their judgement is all there is to being right or wrong. The latter is all I’m arguing against here, not the former at all. -

What School of Philosophy is This?Take things that obviously weren’t intended as though I actually said them if you want, that just makes you look bad, not me.

(Is that “plain English” enough?) -

Moore's Puzzle About BeliefIn my system of logic, I like to use the gerund for what you’re calling “statements”, things devoid of illocutionary force, to make it more clear that they are not assertions. “There BEING a fire in the next room” is an idea toward which we may have various different attitudes, and with which we may do various things. We can assert that that idea, or the state of affairs depicted in it, is real, by saying “There IS a fire in the next room”. We can also assert that that idea, or the state of affairs depicted in it, is moral, by saying “There OUGHT TO BE a fire in the next room”. Possibly we could do other things and adopt other attitudes toward it too.

And we can do all the logic we want on just those gerund ideas of states of affairs. “All men being mortal” and “Socrates being a man” entail “Socrates being mortal”, but in making that inference we haven’t yet committed to any claims that any of those states of affairs are the case, or ought to be the case. -

What School of Philosophy is This?Go ahead and argue in bad faith, that makes you look bad, not me.

-

What School of Philosophy is This?I suspect you're merely describing common morality here — Olivier5

As I've said, I consider my position the common-sense position, merely shored up against bad philosophy. Like the kinds that say nothing is actually moral or immoral, or that what is moral is so because God or someone just said so, or that no moral claims should be accepted until they can be justified from the ground up, or that the kinds of things that are moral are things that have nothing to do with whether or not anything brings suffering or enjoyment to anyone. -

What School of Philosophy is This?I’m not going to repeat something you can just scroll up and read.

-

What School of Philosophy is This?I didn't. This section explicitly speaks of appetites: — Olivier5

Right, but then you speak of desire as though it’s synonymous with appetite.

Do you have an example of what you would consider a moral question? — Olivier5

Name any event, or state of affairs. Asking about that event or state of affairs “is that good or bad?” is a moral question.

How does one account for the future experiences of the yet unborn? And you stop the accpunting at which future generation? — Olivier5

We are to build models of what kinds of things are consistently good or bad, tested against the experiences we have access to. (Just like we build models of what kinds of thing are consistently true or false based on the empirical experiences we have access to). Those models then have implication about the experiences that other people would have in various circumstances, and thus what would be good or bad in those circumstances. If our models predict that there would be some negative future experiences as a result of some present action, then that means our best models judge that action to be bad. It’s always possible our model is incorrect, but that’s no different regarding models of morality than it is models of reality.

It's possible to kill someone without him feeling anything. And how to weight good means vs good ends? What's the mathematical formula? — Olivier5

Removing the possibility of someone feeling pleasures is negatively impacting their experience just as much as inflicting pain on them is. There’s also issues of rights and obligations, necessary goods, property, etc, that get involved there, but I won’t go into all that right now.

The more important thing at the moment is that you don’t weigh good means against good ends. You have to have both.

The primary divide within normative ethics is between consequentialist (or teleological) models, which hold that acts are good or bad only on account of the consequences that they bring about, and deontological models, which hold that acts are good or bad in and of themselves and the consequences of them cannot change that. The decision between them is precisely the decision as to whether the ends justify the means, with consequentialist models saying yes they do, and deontological theories saying no they don't. I hold that that is a strictly speaking false dilemma, between the two types of normative ethical model, although the strict answer I would give to whether the ends justify the means is "no".

But that is because I view the separation of ends and means as itself a false dilemma, in that every means is itself an end, and every end is a means to something more. This is similar to how my views on ontology and epistemology entail a kind of direct realism in which there is no real distinction between representations of reality and reality itself, there is only the incomplete but direct comprehension of small parts of reality that we have, distinguished from the completeness of reality itself that is always at least partially beyond our comprehension.

We aren't trying to figure out what is really real from possibly-fallible representations of reality, we're undertaking a fallible process of trying to piece together our direct sensation of small bits of reality and extrapolate the rest of it from them. Likewise, to behave morally, we aren't just aiming to use possibly-fallible means to indirectly achieve some ends, we're undertaking a process of directly causing ends with each and every behavior, and fallibly attempting to piece all of those together into a greater good.

Perhaps more clearly than that analogy, the dissolution of the dichotomy between ends and means that I mean to articulate here is like how a sound argument cannot merely be a valid argument, and cannot merely have true conclusions, but it must be valid — every step of the argument must be a justified inference from previous ones — and it must have a true conclusion, which requires also that it begin from true premises. If a valid argument leads to a false conclusion, that tells you that the premises of the argument must have been false, because by definition valid inferences from true premises must lead to true conclusions; that's what makes them valid. If the premises were true and the inferences in the argument still lead to a false conclusion, that tells you that the inferences were not valid. But likewise, if an invalid argument happens to have a true conclusion, that's no credit to the argument; the conclusion is true, sure, but the argument is still a bad one, invalid.

I hold that a similar relationship holds between means and ends: means are like inferences, the steps you take to reach an end, which is like a conclusion. Just means must be "good-preserving" in the same way that valid inferences are truth-preserving: just means exercised out of good prior circumstances definitionally must lead to good consequences; just means must introduce no badness, or as Hippocrates wrote in his famous physicians' oath, they must "first, do no harm". If something bad happens as a consequence of some means, then that tells you either that something about those means were unjust, or that there was something already bad in the prior circumstances that those means simply have not alleviated (which failure to alleviate does not make them therefore unjust).

But likewise, if something good happens as a consequence of unjust means, that's no credit to those means; the consequences are good, sure, but the means are still bad ones, unjust. Moral action requires using just means to achieve good ends, and if either of those is neglected, morality has been failed; bad consequences of genuinely just actions means some preexisting badness has still yet to be addressed (or else is a sign that the actions were not genuinely just), and good consequences of unjust actions do not thereby justify those actions.

Consequentialist models of normative ethics concern themselves primarily with defining what is a good state of affairs, and then say that bringing about those states of affairs is what defines a good action. Deontological models of normative ethics concern themselves primarily with defining what makes an action itself intrinsically good, or just, regardless of further consequences of the action. I think that these are both important questions, and they are the moral analogues to questions about ontology and epistemology: fields that I call teleology (from the the Greek "telos" meaning "end" or "purpose"), which is about the objects (in the sense of "goals" or "aims") of morality, like ontology is about the objects of reality; and deontology (from the Greek "deon" meaning "duty"), which is about how to pursue morality, like epistemology is about how to pursue reality. -

What School of Philosophy is This?Do you have some objective process by which correctness can be determined or evaluated? — A Seagull

Yes. Have you not been following the rest of the thread? -

Confusion as to what philosophy isDifferentiate philosophy from other branches of thought. -Why is philosophy not science? Why is philosophy not religion? Why is philosophy not myth? — David Mo

...no definition of philosophy would be complete without demarcating it from those other fields, showing where the line lies between philosophy and something else.

Philosophy is not Religion

The first line of demarcation is between philosophy and religion, which also claims to hold answers to all of those big questions. I would draw the demarcation between them along the line dividing faith and reason, with religions appealing to faith for their answers to these questions, and philosophies attempting to argue for them with reasons. While it is a contentious position within the field of philosophy to conclude that it is never warranted to appeal to faith, it is nevertheless generally accepted that philosophy as an activity characteristically differs from religion as an activity by not appealing to faith to support philosophical positions themselves, even if one of those positions should turn out to be that appeals to faith are sometimes acceptable. The very first philosopher recognized in western history, Thales, is noted for breaking from the use of mythology to explain the world, instead practicing a primitive precursor to what would eventually become science, appealing to observable phenomena as evidence for his attempted explanations.

Philosophy is not Sophistry

Despite turning to argumentation to establish its answers, philosophy is not some relativistic endeavor wherein there are held to be no actually correct answers, only winning and losing arguments. While there are those within philosophy who contentiously advocate for relativism about various topics, philosophy as an activity is characteristically conducted in a manner seeking out answers that are genuinely correct, not merely seeking to win an argument. Though the historical accuracy is disputed, a founding story of the classical era of philosophy ushered in by Socrates, at least as recounted by his student Plato, is that philosophers like them were to be distinguished from the prevailing practitioners of reasoned argumentation of their time, the Sophists, who on Plato's account were precisely such relativists uninterested in genuine truth, only in winning. It is from that account that the contemporary use of the word "sophistry" derives, meaning wise-sounding but secretly manipulative or deceptive argumentation, aimed more at winning than at finding the truth. And whether or not the historical Sophists actually practiced such argumentation, philosophy since the time of Socrates has defined itself in opposition to that.

Philosophy is not Science

What we today call "science" was once considered a sub-field of philosophy, "natural philosophy". This had been the case for thousands of years since at least the time of Aristotle, such that even Issac Newton's seminal work on physics, often considered the capstone of the Scientific Revolution, was titled "Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy". But increasingly since then, what was once considered a sub-field of philosophy is now considered separate from it. What remains still as philosophy is demarcated from science in that while philosophy relies only upon reason or evidence to reach its conclusions, rather than appeals to faith, as an activity it does not appeal to empirical observation either, even though within philosophy one may conclude that empirical observation is the correct way to reach conclusions about reality. It is precisely when one transitions from using empirical observation to support some conclusion, to reasoning about why or whether something like empirical observation (or faith, or so on) is the correct thing to appeal to at all, that one transitions from doing science to doing philosophy.

Philosophy is not Ethics

One may be tempted to conclude that this means philosophy is entirely about prescriptive matters, rather than descriptive ones; that philosophy is all about using reason alone, without appeals to faith, to reach conclusions not about what is or isn't real, but about what one ought or ought not do, or broadly speaking, about morality. In other words, that philosophy is equivalent to the field of ethics. But as described just previously, philosophy does treat other topics concerning not just morality but also reality, at least the topics of how to go about an investigation of what is real. And while ethics is currently considered soundly within the field of philosophy, I contend that it properly should not be, for I hold that there are analogues to the physical sciences, what we might call the ethical sciences, that I consider to be outside the domain of philosophy, in that they appeal to specific, contingent hedonic experiences in the same way the physical sciences appeal to specific, contingent empirical experiences. I hold that philosophy bears the same kind of relation to both the physical and the ethical sciences, providing the justification for each to appeal to their respective kinds of a posteriori experiences, while never itself appealing to either of them, instead dealing entirely with a priori reasoning.

Philosophy is not Math

That in turn may raise the question of how philosophy is to be demarcated from mathematics, which also deals entirely with a priori logical reasoning without any appeal to a posteriori experience. Indeed in some ancient philosophy, such as that of Pythagoras, mathematics and philosophy bleed together in much the same way that what we now consider the separate field of science once did with philosophy as well. But today there is a clear distinction between them, in that while philosophy and mathematics share much in common in their application of logic, they differ in that mathematical proofs merely show that if certain axioms or definitions are taken as true, then certain conclusions follow, while philosophy both does that and asserts the truth of some axioms or definitions. So while mathematics says things of the form "if [premise] then [conclusion]", philosophy says things of the form "[premise], therefore [conclusion]". Mathematics explores the abstract relations of ideas to each other without concern for the applicability of any of those ideas to any more practical matters (although applications for them are nevertheless frequently found), but philosophy is directly concerned with the practical application of the abstractions it deals with. It is not enough to merely define axiomatically some concept of "existence", "knowledge", "mind", etc, and validly expound upon the implications of that concept; it also matters if that is the correct, practically applicable concept of "existence", "knowledge", "mind", etc, that is useful for the purposes to which we want to employ that concept.

Philosophy is not Art

Similarly, philosophy has many similarities to the arts, broadly construed as communicative works presented so as to evoke some reaction in some audience. Philosophy is likewise an evocative, more specifically persuasive, discipline, employing not just logic, as with mathematics above, but also rhetoric, to convince its audience to accept some ideas. But philosophy is not simply a genre of literature. Whereas works of literature, like all works of art, are not the kinds of things that are capable of being correct or incorrect, in the way that scientific theories are, but rather they are only effective or ineffective at evoking their intended reactions, with works of philosophy correctness matters. It is not enough that a philosophical theory be beautiful or intriguing; a philosopher aims for their theories to be right. -

The Unraveling of Americamandatory military training — tim wood

enormous step in entirely the writing direction -

Satanist religions... Anything interesting here?Actual Satanists (not evangelical boogiemen) seem to value freethought knowledge and individual freedom over being a follower either doctrinally or morally. In that sense, the seem basically Nietzschean, advocating what is basically a “master morality“ over a “slave morality”, and likewise what we might call a “master epistemology” over a “slave epistemology”.

They see Satan, as the mythical first rebel, as symbolizing that, making himself the master of his own domain rather than being a slave to God. -

What School of Philosophy is This?But it's easier to come to such agreement with other subjects when the topic is a plant, or a mineral or a star, than when it is yourself. — Olivier5

The objects of moral questions are not ourselves. They are phenomena in the world. We evaluate the morality of those phenomena through our experiences, yes, but we also evaluate the reality of phenomena through our experiences too.

What about educating our feelings and apetites? Trying to change them? Acquiring new ones? Is it not an age-old prescription of legions of philosophers and moralists to try and control our own desires? — Olivier5

You missed the distinction between appetite and desire, and intention. We can’t control our appetites or desires any more than we can control our sensations and perceptions, but we can and should control our intentions just like our beliefs: by not merely accepting whatever we happen to desire or perceive, respectively, but by checking them against both our and others’ appetitive and sensory experiences, and rejecting the parts thereby ruled out from what we judge good and true respectively, i.e. what we intend and believe.

Aren't we supposed to care for future generations? How do you factor in their satisfaction? Our present hedonism is their future doom. Can we burn all the carbon we want, après moi le déluge? — Olivier5

Future generations are other people, and other people’s experiences explicitly matter on my account.

What if in a particular society, the greatest level of good feeling was achieved by, say, killing all people over 70, or killing all red haired people? Would that make such killing "good"? — Olivier5

That definitionally could not be the greatest amount of good feeling, because the people you’re killing count too. And just because more good feeling is a better end than less good feeling, doesn’t mean that end justifies just any means. That’s consequentialism, which I already said I’m against. Morality has to achieve good ends by just means, neither one nor the other alone is sufficient.

There is no practical way to measure people's feelings. — Olivier5

There’s no way to measure other people’s sensory experiences either. But we can try to reproduce them, by standing in the same circumstances they reported experiencing them, seeing if we experience them too, and trying to figure out what’s different between us or the circumstances etc if we can’t. -

The three types of rhetoricI’m not at all doing away with persuasion. I’m simply noting that you can persuade someone that something is (or was, or will be) as much as you can persuade them that it ought to be (or ought to have been). And both of those categories contain both necessary and contingent propositions, and while a certain “epistemic contingency” (uncertainty) may be a prerequisite for the need to persuade someone of something, that doesn’t mean that no rhetoric is ever called for in persuading someone to accept a necessary truth of which they are nevertheless doubtful.

E.g. convincing someone that 0.999... = 1. That is necessarily true, and not a moral claim. Nevertheless plenty of people doubt it, but can potentially be persuaded to believe it. -

What School of Philosophy is This?Being 'correct' is also subjective, at least in matters to do with the real world — A Seagull

That's just your subjective opinion. (But that doesn't mean it can't be incorrect). -

What School of Philosophy is This?That is a subjective opinion. — A Seagull

That doesn't mean it can't be correct. -

What School of Philosophy is This?What makes it subjective, is that it's about the perceptions and opinions of subjects, aka persons, about themselves and other subjects. That's why any moral or political opinion is subjective, including opinions about how best to set the law. It's part of the territory. And your yet to be described process can't escape that either. — Olivier5

Empiricism is inherently "subjective" in that sense too (it's about what observations are made by what kinds of observers in what circumstances), and thus all scientific investigation of reality. That doesn't stop reality from being objective. There is a subject and an object to every investigation; it's the relationship between them that is most primary.

And my process is hardly "yet to be described". I wrote 80,000+ words on it and have gone over it in annoying detail in thread after thread here. Everyone (read: Isaac) just immediately gets hung up on the moral objectivist implications of it and every conversation ends up spiraling around that, so none of the rest of it can even get off the ground.

If you've somehow missed all of that, here are a few prebaked summaries of the whole thing:

With regards to opinions about morality, commensurablism boils down to forming initial opinions on the basis that something, loosely speaking, feels good (and not bad), and then rejecting that and finding some other opinion to replace it with if someone should come across some circumstance wherein it feels bad in some way. And, if two contrary things both feel good or bad in different ways or to different people or under different circumstances, commensurablism means taking into account all the different ways that things feel to different people in different circumstances, and coming up with something new that feels good (and not bad) to everyone in every way in every circumstance, at least those that we've considered so far. In the limit, if we could consider absolutely every way that absolutely everything felt to absolutely everyone in absolutely every circumstance, whatever still felt good across all of that would be the objective good.

In short, the objective good is the limit of what still seems good upon further and further investigation. We can't ever reach that limit, but that is the direction in which to improve our opinions about morality, toward more and more correct ones. Figuring out what what can still be said to feel good when more and more of that is accounted for may be increasingly difficult, but that is the task at hand if we care at all about the good.

When it comes to tackling questions about morality, pursuing justice, we should not take some census or survey of people's intentions or desires, and either try to figure out how all those could all be held at once without conflict, or else (because that likely will not be possible) just declare that whatever the majority, or some privileged authority, intends or desires is good. Instead, we should appeal to everyone's direct appetites, free from any interpretation into desires or intentions yet, and compare and contrast the hedonic experiences of different people in different circumstances to come to a common ground on what experiences there are that need satisfying in order for an intention to be good. Then we should devise models, or strategies, that purport to satisfy all those experiences, and test them against further experiences, rejecting those that fail to satisfy any of them, and selecting the simplest, most efficient of those that remain as what we tentatively hold to be good. This entire process should be carried out in an organized, collaborative, but intrinsically non-authoritarian political structure.

Like her, I think you should leave philosophy and study mathematics instead. — Olivier5

Sorry, I already got a degree in philosophy, and you apparently don't know basic philosophical terms like altruism, hedonism, and consequentialism, so ... -

Will pessimism eventually lead some people to suicide?Pessimism, however, is simply a rationalization (à la hypochondria) for coping with ineluctable frustrations (i.e. facticity). Besides — 180 Proof

:up: :100:

Suffering is made of thought. Thought is just a part of your body. Learn how to better manage this part of your body. — Hippyhead

:clap: :point: -

Confusion as to what philosophy isI think a quick and general answer would be that philosophy is about the fundamental topics that lie at the core of all other fields of inquiry, broad topics like reality, morality, knowledge, justice, reason, beauty, the mind and the will, social institutions of education and governance, and perhaps above all meaning, both in the abstract linguistic sense, and in the practical sense of what is important in life and why.

But philosophy is far from the only field that inquires into any of those topics, and no definition of philosophy would be complete without demarcating it from those other fields, showing where the line lies between philosophy and something else.

Philosophy uses the tools of mathematics and the arts, logic and rhetoric, to do the job of creating the tools of the physical and ethical sciences. It is the bridge between the more abstract disciplines and the more practical ones: an inquiry stops being science and starts being philosophy when instead of using some methods that appeal to specific contingent experiences, it begins questioning and justifying the use of such methods in a more abstract way; and that activity in turn ceases to be philosophy and becomes art or math instead when that abstraction ceases to be concerned with figuring out how to practically answer questions about what is real or what is moral, but turns instead to the structure or presentation of the ideas themselves.

The characteristic activity of philosophy is the pursuit of wisdom, not the possession or exercise thereof. Wisdom, in turn, is not merely some set of correct opinions, but rather the ability to discern the true from the false, the good from the bad; or at least the more true from the less true, the better from the worse; the ability, in short, to discern superior answers from inferior answers to any given question. -

Moore's Puzzle About BeliefThat difference in perspective explains, I think, why qualifying an assertion with the modifier "...believe(s) that..." can both be used to stress what one takes to be the good standing of one's epistemic credentials (when used first-personally) or be used to bring into question (and thereby attempt to weaken) someone else's credentials (when used third personally). — Pierre-Normand

I would like to hear if anyone else here thinks that “I believe...” strengthens rather than weakens an assertion, because that sounds very unusual to me. Even “I strongly believe that P” sounds weaker than just “P” to my ear. I asked my English major girlfriend her opinion, within letting her know mine first, and she said the same thing.

In any case, whatever specific wording conveys whatever specific force, the point of my impression/expression distinction is just that there is a difference in force there, where one can express a belief without fully asserting its truth, or impress it upon others. The later normally implies the former, but in the case of dishonesty doesn’t necessarily have to.

Pfhorrest

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum