Comments

-

Postmodern Philosophy : what is it good for?And what is genuine value? — schopenhauer1

The true and the good, like always. But no from-on-high declaration of what is absolutely true or what is absolutely good, what you must believe or what you must do. Just fallible ordinary people doing their best to at least try. -

Architectonics: systemic philosophical principlesThank you for that great analysis! Overall I mostly agree with your reading, but there's some finicky little details where I think differently about the east-west divide:

And then east/west is the flip between the objective and the subjective - the world and the mind — apokrisis

I think of both sides as having both objective and subjective aspects to them, which often blur and blend together in spectra instead of sharp dichotomies. The organizing principle distinguishing the physical and ethical parts is direction-of-fit though, so you're close to seeing my thinking there. It's not world on the left, mind on the right, but mind-to-world on the left and world-to-mind on the right.

At least for those bottom parts. I see both logic and rhetoric as having roles in both the mind-to-world and world-to-mind sides of things (there is a logic of reality and a logic of morality, and a rhetoric to teach what is real and a rhetoric to teach what is moral). The division between those two I instead describe as:

... whereas logic is more mathematical, concerning itself with the form and structure of the argument and appealing more impersonally to dispassionate thought, rhetoric as I would characterize it is more artistic, concerning itself with the style and presentation of the argument and appealing more personally to passions and feelings ... when I speak of rhetoric, I am speaking of the packaging and delivery of speech-acts, as differentiated from the contents and structure thereof [which I cover under logic]

[...]

logic and rhetoric as complimentary to each other, not in competition. I like to use an analogy of prescribing someone medicine: the actual medicinal content is most important of course, but you stand a much better chance of getting someone to actually swallow that content if it's packaged in a small, smooth, sweet-tasting pill than if it's packaged in a big, jagged, bitter pill. In this analogy, the medicinal content of the pill is the logical, rational content of a speech-act, while the size, texture, and flavor of the pill is the rhetorical packaging and delivery of the speech-act. It is of course important that the "medicine" (logic) be right, but it's just as important that the "pill" (rhetoric) be such that people will actually swallow it.

That content vs packaging dichotomy doesn't seem to line up perfectly with the direction-of-fit dichotomy. But nevertheless, as logic segues into mathematics and that into philosophy of mathematics, philosophy of mathematics then segues into ontology and so still connects more to that mind-to-world side of things. And as rhetoric segues into the arts (inasmuch as they are all about style, package and delivery) and that into aesthetics, aesthetics then segues into ethics and so still connects more to that world-to-mind side of things.

I feel like there is still some missing piece in my understanding of why exactly it seems to work out that way, when it superficially seems like math-art should be a different axis entirely than physics-ethics. -

Postmodern Philosophy : what is it good for?When is one to be ironic and one to be authentic? Is there a good balance? — schopenhauer1

Be ironic toward the made-up hifalutin' nonsense, and be authentic toward the simple, fallible things of genuine value. Try for truth, try to do good, and in doing so tacitly assume through your actions like they are attainable, never impossible, but also never guaranteed. If someone thinks either is guaranteed, roll your eyes at them. But also roll your eyes at those who think either is impossible. Just get to work, realizing it might be hopeless, but try anyway.

Jim rolls his eyes at the camera over all the office bullshit, but he still does an honest day's work. -

Is the forum a reflection of the world?Honestly, I suspect that someone who thinks they’re going to be in over their head would make a better forum participant than someone who thinks they have it all figured out but really doesn’t. You can ask honest questions, even “stupid” ones, and people can give you their different answers, and argue with each other, trying to convince you the new guy that each other are wrong. Sounds a lot more productive and enjoyable than yet another “look I proved that God exists“ type of thread.

-

Architectonics: systemic philosophical principlesOh and additionally, on the relationship between the sciences (physical and ethical), philosophy, and both math and art, I wrote elsewhere something else that Peirce reminds me of:

Philosophy uses the tools of mathematics and the arts, logic and rhetoric, to do the job of creating the tools of the physical and ethical sciences. It is the bridge between the more abstract disciplines and the more practical ones: an inquiry stops being science and starts being philosophy when instead of using some methods that appeal to specific contingent experiences, it begins questioning and justifying the use of such methods in a more abstract way; and that activity in turn ceases to be philosophy and becomes art or math instead when that abstraction ceases to be concerned with figuring out how to practically answer questions about what is real or what is moral, but turns instead to the structure or presentation of the ideas themselves.

Mathematics explores the abstract relations of ideas to each other without concern for the applicability of any of those ideas to any more practical matters (although applications for them are nevertheless frequently found), but philosophy is directly concerned with the practical application of the abstractions it deals with. It is not enough to merely define axiomatically some concept of "existence", "knowledge", "mind", etc, and validly expound upon the implications of that concept; it also matters if that is the correct, practically applicable concept of "existence", "knowledge", "mind", etc, that is useful for the purposes to which we want to employ that concept.

And it is not enough that a philosophical theory be beautiful or intriguing; a philosopher aims for their theories to be right. -

Architectonics: systemic philosophical principlesBut a sense can be made of the hierarchy IEP describes where maths is the most general discipline in terms of being the most abstract level of rationalisation and philosophy is a concrete expression of that rationalising habit. We are in the realm of Platonic forms, but moving towards engagement with the world. Then science is the habit of rationalisation properly engaged with the world as empirical knowledge creation. — apokrisis

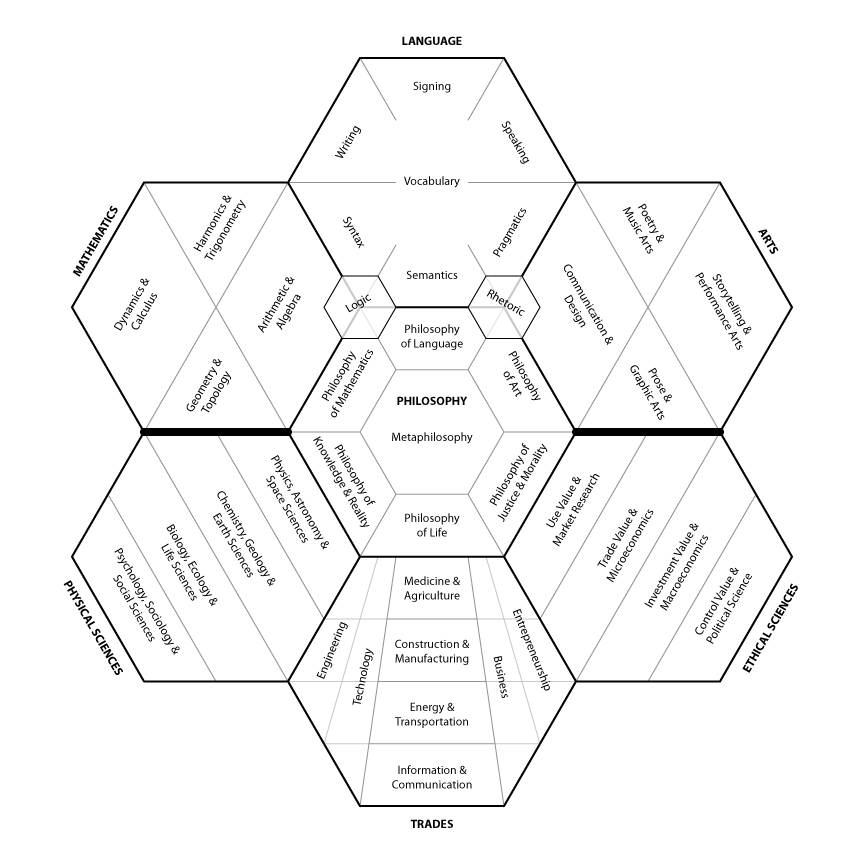

I remember this from the cursory study of Peirce that I have done, and I remember remarking on how it’s almost perfectly half of my own structure of philosophy as discussed in my thread on that topic (linked in the OP). I have language in general at the very top (from one perspective), then mathematics below it to one side. Centered directly below language and further down than mathematics is philosophy overall, with philosophy of language and philosophy of math bordering the respective fields, and relating to each other and math and language generally relate. At the intersection of all three is logic. Philosophy of math segues into ontology, epistemology, and other subfields of philosophy relating to knowledge and reality. Then below and off to that same side come the physical sciences: physics and astronomy, chemistry and geology, biology and ecology, psychology and sociology...

But on the other side, there is an independent and parallel chain. The arts are below and to the other side of language, opposite math, and at the intersection of language, art, and the philosophies thereof, lies rhetoric. Philosophy of art / aesthetics segues into ethics and other subfields of philosophy to do with justice and morality, opposite ontology, epistemology, and other philosophy of knowledge and reality. Then below that, I propose a whole chain of underdeveloped ethical sciences, incorporating elements of some existing fields like economics and political science.

Just as the physical sciences then segue into engineering and technology, about the tools we use to do all our jobs, so too those ethical sciences segue into entrepreneurship and business, about the jobs we use al those tools to do. At the bottom, most concretely, opposite the most abstract field of language, are the various trades using those various tools to do those various jobs.

-

Postmodern Philosophy : what is it good for?Something can have the opposite direction of fit without therefore being arbitrary. One could declare arbitrary laws of reality too; religions do that all the time.

I spoke already upthread about my problem with social constructivism taking all attempts to talk about facts as actual hidden power grabs, and trying to take moral discourse to be description is the same problem in reverse. There are two different kinds of reductionism that I consider tantamount to “cynicism” (an approach that can’t help but lead to nihilism of some sort), because each of them effectively refuses to consider even the possibility of answers to a certain kind of question, by insisting that that kind of question is reducible to another, unrelated kind of question.

Besides constructivism already discussed, scientism conversely attempts to reduce all questions to questions of fact, which is to say, descriptive questions, questions about reality. Questions of norms, which is to say, prescriptive questions, questions about morality, are a fundamentally different kind of question to questions of fact, to which a descriptive statement gives no answer; something David Hume called the "is-ought problem". If someone asks whether something ought to happen, a statement to the effect that something does (or does not) happen gives no answer at all to that question.

So to insist on discussing only matters of fact, and trying to twist all discussion of norms into discussion of facts, is simply to avoid answering any normative, moral questions at all, and so implicitly to avoid stating any opinion on morality at all, leaving one in effect a moral nihilist. Scientism responds to attempts to treat normative questions as completely separate from factual questions (as they are) by demanding absolute proof from the ground up that anything at all is objectively normative, or moral, and not just a factual claim in disguise or else baseless mere opinion. So it ends up falling to justificationism about normative questions (where justificationism is the primary kind of “cynicism”), while failing to acknowledge that factual questions are equally vulnerable to that line of attack. Thus such scientism is tantamount to cynicism with regards to moral questions, inevitably leading to moral nihilism.

But in my rejection of scientism, I am not at all rejecting science. I have great esteem for science and hold it to be the uniquely correct way of building true descriptions of reality. I am only against attempting to reduce all discourse to attempts at describing reality, when we clearly also do other things with our speech as well. Ordering someone to do something, for instance, is not an attempt to describe what that person is doing, and such a command cannot be factually right or wrong (although we could instead evaluate the command as normatively right or wrong). I hold moral claims to be more akin to such orders or commands than they are to descriptive claims, though they are often phrased in such as way as to project that morality as though it were a descriptive property of whatever is being evaluated; not unlike with social constructs. -

Postmodern Philosophy : what is it good for?One can posit objective moral law, but it has little explanatory power compared to the assumption of an objective physical reality which obeys physical law. — Kenosha Kid

Moral law isn't supposed to be explanatory. It's not descriptive, but prescriptive. -

Postmodern Philosophy : what is it good for?You have an embedded assumption that the causes of the differences are of a like kind. — Adam's Off Ox

It's not embedded as in tacit or implicit, I explicitly say we pragmatically must make such an assumption, because to do otherwise is simply to give up on the attempt. If we haven't succeeded at the endeavor yet, we just haven't succeeded yet, but that is no grounds to say success is impossible. It is assuming that success is impossible because it has been hard so far that is the inductive leap. I am saying to keep open to the possibility of it, and keep trying, always. -

Postmodern Philosophy : what is it good for?It is in empiricism that the explanatory power of objective reality finds its place, not in belief systems — Kenosha Kid

Completely true, but what is empiricism if not appeal to the things we have in common between our sensory experiences, and a commitment to sorting out why we sometimes have different ones?

There is a kind of experience that impacts opinions about morality in the same way sensory experience impacts opinions about reality: appetitive experiences, things like pain and hunger etc. An appeal to the things we have in common between such experiences and a commitment to sorting out why we sometimes have different ones would enable an approach to morality just as objective as a scientific approach to morality. -

What do you experts say about these definitions of abstraction?All actual circles, obviously. None of which are perfectly identical to that ideal circle, but the thing they have in common with each other that makes them al circles is their similarity to that ideal circle.

-

Can something be ''more conscious'' than we are?There is another user here, bert1, who knows a lot about panpsychism and can discuss it in a very articulate way. I’m pinging him to come join this conversation so maybe you can get some more productive discussion instead of just people denying your premises.

-

Can something be ''more conscious'' than we are?Paging @bert1, Dr. Bert1 to the green panpsychist thread please. Your assistance is needed.

-

Postmodern Philosophy : what is it good for?At best, it makes no difference whether it exists or not, because bottom-up self-organising morality has all of the explanatory power and seems like what actually occurs. — Kenosha Kid

To the extent that that is true, I would say the exact same thing about reality. Humans seems to have a lot of the same subjective experiences and to perceive a lot of the same things in those experiences and so to believe a lot of the same things.

But some people don’t. Beliefs about reality obviously differ drastically between cultures, especially historically before the rise of science (look at all the different religions’ accounts of the nature and history of the world). Perceptions differ too because they are inherently interpretations, not the raw sensory observations themselves. Even sensations differ: some people are blind or deaf, some women have tetrachromatic vision and some men are color blind, etc.

Science is in assuming that we can account for and reconcile all those differences and converge on some total common agreement about what is real if we’re just very careful, thorough, and methodical about it. That involves assuming that there is some objectivity reality that all of our different experiences, sensations, perceptions, beliefs, are incomplete or distorted pictures of.

I see no reason not to approach morality in the same way, not so unlike how you describe it, but in undertaking a project to do that, we necessary act under the tacit assumption that there is some objective morality: that we can account for and reconcile all our moral differences and converge on some total common agreement about what is moral if we’re just very careful, thorough, and methodical about it. -

What do you experts say about these definitions of abstraction?Consider the number 2. It is abstract, but it has no instances, so it is not a universal. — Nagase

Is not any pair of objects an instance of the number 2?

In any case, etymologically “abstract” means “pulled apart”, so I think the OP example of breaking down and analyzing a car, or of removing unnecessary details, etc, is on the right track. “Catness” is whatever features all individual cats have, pulled apart from the features that differ between individuals. “2” is whatever is in common between all pairs of objects, pulled apart from the unnecessary details that differ between them. Etc. -

Architectonics: systemic philosophical principlesHow is an OP on the architectonic structure of theories not an epistemological question? — apokrisis

It is possible I misunderstood the word “architectonic”.

In any case, epistemology is but one subfield of philosophy. I suppose one could approach all of philosophy through epistemology, placing it as their “first philosophy”, but that seems to me like merely one perspective one could take on the interrelationships of different subtopics, as @fdrake describes. -

Postmodern Philosophy : what is it good for?In both, objective reality is inferred from human activity. In science, the existence of objective reality is the simplest possible explanation for why the universe behaves as if it does, i.e. it appears to be a top-down. In morality, not so much. We know why morality is in some ways universal and others not, and it's a bottom-up structure, not a top-down one. (We'll end up making every thread about this before the week is out.) — Kenosha Kid

I’m not sure what you mean here by top-down and bottom-uo. I would describe science as a bottom-up process the way I mean those words: it’s a decentralized, fallibilist operation, rather than some authority handing down truths from on high. You seem to think that an objective morality would have to be that kind if from-on-high approach, but my point is that science doesn’t do that and yet is still objective about reality, so we can do likewise toward morality too. -

Why is mental health not taken seriouslyBlame (the act of blaming, not the mere attribution of someone as the cause of something ) is never morally deserved, but can sometimes be an effective treatment perhaps. Blame is basically a verbal form of punishment, and punishment should be entirely preventative, rehabilitative, and restorative, never punitive. If blaming someone makes them change, then it’s an effective response. If not, then it’s just making them feel bad for no productive reason.

There is definitely such a thing as agency though. Agency, acting in a way that you thought was best because you thought so, rather than doing things you wish you hadn’t because you just couldn’t make yourself do otherwise, is kind of the opposite of character defects: an agentive, freely willed, self-controlled mode of operation is a properly functioning mind. It seems plausible that it could be exactly in those circumstances that blame is effectively: someone did something they thought was the best course of action, it wasn’t, and telling them so may be effective in making them do differently in the future. -

Why is mental health not taken seriouslyDo you think there are character defects at all? — jamalrob

I do, but I think of them as one should think of mental illnesses, which they are. If I have an infection or traumatic injury or genetic deformity in my leg, then my leg is defective. That’s not something I deserve blame for though, that’s something I deserve sympathy and treatment for. Likewise if something is wrong with the way my mind works, that’s a “character defect”, inasmuch as my mind defines my character. But that is likewise not something that warrants blame, but sympathy and treatment.

NB that on my account disease of any kind, mental or physical, is defined by the suffering of the person who has it. If my leg is unusual in a way that I prefer, then it’s not diseased or injured. Likewise if my mind is unusual in a way that I prefer. -

Architectonics: systemic philosophical principlesIt also occurs to me that I could be under a mistaken impression that Kant, Peirce, etc, even have general principles with myriad specific applications in the way I mean. I've studied them both some, probably not as extensively as you @apokrisis, and I didn't come away with an idea of what they were, so maybe they don't have them. I'm only under the impression that they did, and I somehow missed it, because people here have called my approach "architectonic", a word I wasn't previously very familiar with, and I have since read that Kant and Peirce at least are also described by that word, which I took to mean that they had approaches similar in structure (not necessarily content) to mine. But I might just be wrong about that; please let me know if so.

-

Architectonics: systemic philosophical principlesWhere do they start (their general principles) and where does that take them (their various conclusions about specific topics). — Pfhorrest

NB that I'm not implying this is chronological; just logical. They maybe started chronologically with a bunch of conclusions that seemed correct, then noticed shared types of reasoning in those, and worked back to general principles that had implicitly underlain their reasoning on those specific topics. I know that's how it went for me. Well, back and forth actually, from specifics to general to specifics and back again, until it all cohered together nicely. Which sounds a lot like what you're saying Peirce's process is like. But that still doesn't tell me (perhaps) what the general principles on one end of that are, and what the specific conclusions he derives from them on the other end are. -

Architectonics: systemic philosophical principlesLists don’t really cut it if what you are reaching for is an account of a functional architecture — apokrisis

I'm not so much looking for a complete account of it at this point, as a sketch of it. Where do they start (their general principles) and where does that take them (their various conclusions about specific topics).

The rest of what you've described of Peirce's sounds like an epistemology. Maybe his principles are generally epistemological in character, I guess that could be fine. But where does following that take him on questions about, say, freedom of will, or politics? I don't need the complete chain of reasoning that he follows from those principles to reach those conclusions, I'm just curious, for our purposes here, what the general start and specific ends are. -

Architectonics: systemic philosophical principlesActually I stated my own principles implications incorrectly just then. Positions in all of those different fields are directly implicated by my principles, but also there are cross-implications between various fields: ontology and mind, ethicse and will, epistemology and academics, ethicsm and politics, ontology and epistemology and mathematics, ethicse and ethicsm and the arts, math and art and language, mind and academics and life, and will and politics and life; as illustrated in my earlier thread on the structure of philosophy.

-

Architectonics: systemic philosophical principlesI think I agree with you about the idea of a network of different relationships between various subfields, and that is the kind of thing that (as I said in the OP) got me to thinking about this kind of thing. But what I'm wondering about is if anyone here (or notable philosophers like Peirce and Kant) does a thing like I do: I don't have any one field as the core of philosophy upon which all others depend, but I have some very general principles that have implications on a bunch of fields, which then have implications on still other fields, etc.

(My principles, for example, have direct implications on ontology, epistemology, and on ethics in two different ways, forcing me to split it up into two fields; ontology then has implications on philosophy of mind, epistemology on education, the two parts of ethics on will and politics respectively; ontology also has implications on philosophy of math, and ethics on philosophy of art; and the whole arrangement has implications on philosophy of language and "philosophy of life"). -

Postmodern Philosophy : what is it good for?moral objectivity about an objective set of moral truths — Kenosha Kid

No more so than notions of objective reality, which you support in your support of natural science. Objective reality doesn't depend on there being some unquestionable set of descriptive statements; as you know in science everything is open to question, every claim is tentative, subject to later revision. There's no reason that one can't take precisely that same attitude toward morality, which would be exactly as objective an approach to morality as the scientific approach is to reality. That would mean there isn't some unquestionable set of prescriptive statements ("moral truths"), just a notion that there is some scale of correctness, some way to indicate what the direction toward more correct is, something by which such statements can be critically compared to each other, rather than all being equally indefensible out the gate.

rationalism around objective reality as discoverable by thinking really hard about it — Kenosha Kid

Okay, so you meant capital-R "Rationalism" as in the anti-empirical philosophical movement containing people like Descartes, Spinoza, and Leibniz, not just common-noun rationalism as in asking for reasons to (dis)believe things and not just obeying orthodoxy on faith. No disagreement there then. -

Architectonics: systemic philosophical principlesI am enjoying reading your posts, but struggling to pull out of them the kind of thing I was wondering about in the OP.

Since you seem to know much about both Kant and Peirce, who are two architectonic philosophers I was specifically wondering about, do you think you could give a couple short lists like the ones I gave for my philosophy in the other thread (linked in the OP) for each of them? A list of a few sentences that are their core principles, and a list of a few sentences that are the entailed positions they consequently take on some different philosophical questions? A pair of such lists for each of them.

Thanks! -

Dark Matter possibly preceded the Big Bang by ~3 billion years.I don't think it's absurd at all. — fishfry

But you just said a moment ago:

"Past eternal but not bounded?" Sorry that doesn't make a lot of sense. — fishfry

I'm still confused by where you're coming from. Sometimes you claim an infinite past is a plausible or at least published scientific theory; but recently you said that you aren't talking about science, only philosophy. — fishfry

I said there are scientific theories that don’t rule it out. That doesn’t mean they say it is definite so. -

Cutting edge branch of philosophyThat’s not an accurate historical account. Philosophy wasn’t and isn’t always just about speculating, and mathematics is older than the branching of science off of philosophy, and used to be mixed up with philosophy itself (as with Pythagoras).

-

Demarcating theology, or, what not to post to Philosophy of ReligionIf you mean the quality of the forum, it has seemed both busier and less hostile in the parts that I’ve interacted with the past few days.

-

Dark Matter possibly preceded the Big Bang by ~3 billion years.I think you're confused somehow about this conversation. I've only posted that link the one time. And I didn't say that science claims there definitely is an infinite past, just that an eternal inflation model doesn't rule one out. Here's what I said before:

there is also a model of eternal inflation, where there wasn't necessarily any start of time, just a local stop of inflation, which is the "big bang" for all intents and purposes as we usually mean it, in such a model — Pfhorrest

So far as I understand, theories of eternal inflation don't claim to settle the question either way of whether time had a beginning; they just open the door for the possibility that it didn't, since the thing that we previously thought was the beginning turns out (on such a model) to not have been. We don't yet have evidence one way or another (even counting the limited evidence that supports eternal inflation) to tell, scientifically, whether or not there was any start to the inflating universe; the model is consistent with either option — Pfhorrest

You seemed to think that it would be absurd to even think that it could be infinitely old, and I don't see why that or any other "actual infinity" would be absurd.

ETA: Also, Kenosha wrote:

the eternal inflation field which may have caused the start of this universe, which may be eternal into the past — Kenosha Kid

Nobody is claiming anything in science says the past is definitely infinite, just that it's not definitely finite (which, NB, is not the same thing as "definitely not finite"). -

0.999... = 1That doesn’t seem in disagreement with my point at all, which is that the naturals aren’t closed under subtraction. You have to invent additive inverses of the naturals, creating the integers, or else some subtractions will not have solutions.

-

0.999... = 1That's your qualification not mine. I can perfectly well consider - invent - a negative number by considering relations between positive numbers. I have $5; I owe $10 - a perfectly natural situation. What is my net worth at the moment? Less than 1. — tim wood

Yes or course, but that relation there is subtraction, not addition. You have X and owe Y, so your net worth is Z = X - Y. So long as X > Y you can start with natural numbers and stay within them, but once X < Y you have to, as you say, invent a new kind of number.

Likewise with division, square roots, etc. They require you to invent new kinds of numbers, because the kinds of numbers you already had aren’t suitable to solve all such problems. -

Fashion and RacismIf one did do a racism on the grounds of fashion, would that be... fashism?

I’ll show myself to the door. -

0.999... = 1I just gave a bunch of examples.

You can’t get -1 by adding natural numbers to each other. You have to do subtraction, and then that takes you out of the naturals to the integers.

You can’t get 1/2 by adding (or subtracting) integers to each other. You have to do division, and then that takes you out of the integers to the rationals.

You can’t get the square root of 2 by adding (or subtracting or dividing) rationals to each other. You have to take a square root, and then that takes you out of the rationals and into the reals.

Etc.

My best attempt: — Michael

Clever! :up: -

Is the forum a reflection of the world?But why make an account for somewhere that that’s only required for posting, when you’re not going to post?

-

Architectonics: systemic philosophical principlesThanks for that! This is the response most in line so far with the kind of thing I was looking for.

-

0.999... = 1Yep. No amount of addition will result in the square root of negative one half.

-

Joe Biden (+General Biden/Harris Administration)3) Nail down universal health care. — tim wood

Unfortunately this isn’t something Biden could personally make happen, unlike most of the rest of your list. That’s something that will take both houses of congress to accomplish. -

0.999... = 1I thought all mathematics is addition, with just some techniques for doing it efficiently. — tim wood

That may be true of multiplication, exponentiation, tetration, etc, but the inverse operations break that closure. The numbers you can get by starting with 1 and then doing those operations are all the same, the natural numbers.

But if you subtract (undo addition to) a natural from another, you might get something that isn’t a natural: a negative number. So okay, we call the naturals and their negatives integers.

But if you divide (undo multiplication to) an integer by another, you might get something that’s not an integer: a fraction. Okay, so the integers and all their fractions are the rationals.

But if you take the root or log of (undo exponentiation to) a rational, you might get something that isn’t a rational... etc. -

The principles of commensurablismWhere there is no shared phenomenal experience there's no correct opinion. — Isaac

This doesn’t sound quite like what I mean, but I’m having difficulty explaining quite why.

I think a good illustration would be the parable of the three blind men and the elephant, which I presume you’re familiar with. As the story goes, none of the three men have shared their phenomenal experiences of the elephant yet. But there is still the correct opinion, that it is an elephant they are feeling. That correct opinion has to be consistent with all of their separate experiences. Nobody is going to come to that opinion without having all of those different experiences to combine together; and even someone who has had all of these different experiences still has to think up something that would account for all of them together.

So for any of these blind men to figure out what they’re really touching despite their differences of opinion (that all seem well-founded to each of them based on their limited experiences), someone is going to have to stand where the other ones stood and feel what they felt in order to have the full set of experiences with which their hypotheses about the thing in question need to accord. If the blind man doing that checking doesn’t feel what the other blind men reported feeling there, he’s got to figure out what is different between them to account for why they feel different things in the same circumstances.

That doesn’t mean he has to figure out what could possibly be a tree, a snake, and a rope all at the same time. It means he’s got to figure out what feels like a tree to this kind of person in this context, feels like a snake to that kind of person in that context, and feels like a rope to another kind of person in another kind of context. In the end, the investigative blind man will have a bunch of experiences with which the hypothesis of an elephant is consistent.

Where we don't know if there's shared phenomenal experience, we're better off proceeding as if there is because that we we might approach a correct opinion, whereas presuming there isn't rules out that possibility. — Isaac

It’s more that, as described above, we should proceed on the assumption that our phenomenal experiences are in principle sharable: that we can figure out what is different about ourselves and the circumstances we’re in that accounts for the differences in our experiences, and then build a model that accounts for every kind of experience anybody would have in any circumstance. That might be really hard to do, but we have a better chance of getting closer to doing it if we act as though it’s possible by trying to do it, than if we say it’s not possible and so don’t try.

So the opinion that I'm asking about is the opinion that right/wrong equates to pleasure/pain. That opinion seems not to be one which benefits from much shared phenomenal experience - people seem to disagree quite widely about it. — Isaac

This seems like a category error to me. When I talk about pleasure and pain etc, I mean them in a way that isn’t separable from the things seeming good or bad. If you like some experience, enjoy having it, then it doesn’t seem correct to call that painful to you.

You might still decide to bear some pain to get something else you enjoy, but if it’s truly pain to you then it seems analytic that you would prefer to avoid it if possible. If you could get a healthy fit body (which is enjoyable to have) without suffering from your workouts, you’d want that. You decide to bear the pain of the workout for the greater pleasure of fitness because the alternative seems to you like even greater suffering overall. You’re picking the path that seems least bad, even though it is still kinda bad — “bad” in terms of suffering and enjoyment, pleasure and pain, etc.

That is all a purely subjective assessment of good and bad so far; not an assessment that pain is bad etc — that’s just analytically true, “pain” is “whatever feels bad” — but an assessment of what is best on account of merely your own pain etc. Making it objectively just means concerning yourself in the same way with experiences that you personally aren’t having right now. In the same way that you could be an empiricist and be a total solipsist, believing that things you personally don’t see are not real; making such empiricism objective just means accounting for everything that “seems true” (empirically) to everyone in every context. Likewise, hedonism can be made objective by accounting for everything that “seems good” (hedonically) to everyone in every context.

The alternatives in both cases are either denying that anything at all is actually true/good (and so all our empirical/hedonic experiences of things seeming true/good are just subjective illusions all equally baseless), or else that whatever it is that is true/good is so in virtue of something besides our experiences (in which case we have nothing against which to gauge what is true/good, and just have to take someone’s word as to what it is).

And if we’re not even sure whether anything is true/good or whether we can figure out what it is, we stand a better chance of figuring out what it is (if that turns out to be possible after all) if we try, acting as though something is true/good and we have some access to (experience of) what that is, and then trying to account for as many pieces of that access (as many experiences) as possible.

When applied to questions of what is true, that results in empirical realism. When applied to questions of what is good, that results in hedonic altruism.

Pfhorrest

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum