Comments

-

Why Nothingness Cosmogony is NonsenseIf modal realism is true, then the “innate potential for reality to exist” just consists of the trivial fact that there is no possible world at which there is no world, i.e. at every possible world there is some world, so some world or another existing is not only possible, but necessary. There couldn’t have been nothing.

-

My profile pic?Consensus seems to be leaning strongly toward personal logo, so I've changed it back for now. Thanks everyone for the feedback.

-

Plantinga: Is Belief in God Properly Basic?I know he claims that, but I'm saying that it's not the same as the kind of experiences we have with one another. The kind of experiences we have with one another are not the kind that can be sensibly doubted, at least not usually. Whereas these supposedly direct experiences with God are easily doubted for good reason. — Sam26

And then there is the point I made earlier, that didn't seem to strike a chord with anyone. When you see your hand and are prompted to believe that your hand exists, the contents of that belief are an elaboration upon the details of the experience that prompted it. If you look up at a grand starry sky and are thereby prompted to believe that God exists, the contents of that belief, whatever they are (it's not really clear), are different from just an elaboration upon the details of the experience that prompted it, which would instead be something like a belief about astronomical facts. -

Bernie SandersIt occurs to me that if my system were in place, it might not even result in a significantly inflated Supreme Court; in fact it looks like said court might remain about the same size, if history is anything to go by:

Trump would have gotten one appointment instead of the two he's had so far, so we'd actually be down to a size of eight right now on account of that, 4 liberal 4 conservative.

Obama would have gotten two, which he did.

GWB would have gotten two, which he did.

Clinton would have gotten two, which he did.

GHWB would have gotten one, and we currently have one of the two he appointed still with us, so we might have been down to a size of seven at some point on account of that, with one fewer conservative.

Reagan would have gotten two, instead of the four he did, so we might have been down to a size of five at some point on account of that, with cumulatively four fewer conservatives.

Carter would have gotten one, instead of the zero he did, so we wouldn't have been down to five but only six at some point under Reagan, with one more liberal and still cumulatively four fewer conservatives.

Ford would have gotten one, which he did.

Nixon would have gotten one, instead of the four he did, so we might have been down to a size of three at some point on account of that, with cumulatively seven fewer conservatives and one more liberal.

Johnson would have gotten one, instead of the two he did, so we might have been down to a size of two at some point on account of that, with cumulatively seven fewer conservatives.

JFK would have gotten one, instead of the two he did, so we might have been down to a size of one at some point on account of that, with cumulatively one fewer liberal and seven fewer conservatives.

Eisenhower would have gotten two, instead of the five he did, so we might have been down to a size of... er... negative three, with cumulatively one fewer liberal and ten fewer conservatives...

Yeah, looking back on how this would have worked out historically makes me think that maybe each presidential term should get two nominees, not just one, to make sure that the Supreme Court doesn't wither away and die. Have an appointment every Presidential and Midterm election, so each appointment coincides with a different President/Congress combination. Also then the court balance adjusts more quickly with the times, but still with plenty of past inertia to keep it stable.

So GHWB would have gotten two, as he did, only one of whom survives to this day.

Clinton would have gotten four, instead of two.

GWB would have gotten four, instead of two.

Obama would have gotten four, instead of two.

And Trump would have gotten two, as he has.

So we would currently (assuming none of the newer appointees would have died or retired in the meanwhile) have a Supreme Court size of fifteen, with seven conservatives and eight liberals, had we always used this system.

And man, looking back over the court history to compile this post... Republicans have gotten damn lucky with happening to be in office right as a bunch of justices were dying off, going back for decades and decades, even before they started outright stealing them like Mitch and Trump did. I mean look at those cumulative differentials... things have been tilted as much as +9 toward the conservative side since Eisenhower. -

Bernie SandersOne, the members of the Supreme Court need to be rotated more often -- which means ending life-time appointments. Fixed terms would solve part of the problem. The court IS POLITICAL. It has to be knocked off its pseudo-august pedestal. — Bitter Crank

A solution to this problem that I’ve thought up before that would be easier to implement constitutionally and probably a lot easier to sell to the politicians who would have to implement it: every presidential term is guaranteed one Supreme Court appointment (and if the Senate doesn’t approve any such appointment by the end of a term, the court itself chooses its pick of the President’s various nominees). Justices still remain seated for life (or their voluntary retirement).

This would gradually increase the number of justices, yes, but in an orderly and controlled way, not starting a fight between parties for who can inflate the court the fastest to maintain their political edge; and only up to a limit naturally set by the age of the appointees. This would result in judges that are still unbeholden to political popularity, and a court that continues to be a steady rudder not constantly changing with the political winds, but also make the court gradually change with the political evolution of the country, with a range of justices to each reflecting one small period of the country’s political mood from some time in living memory. -

Bernie SandersWhat do you make of Krugman's position vs. Wolff's? I'll link below, if you're interested:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z6J3ROV4IPc — Xtrix

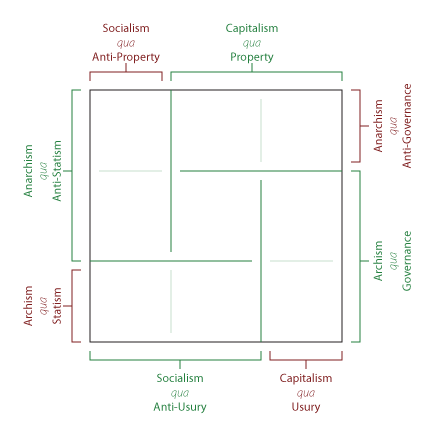

They both sound mostly correct and not in contradiction to me. The places I see them disagreeing are on whether Bernie's use of the term socialism is politically expedient (they both seem to agree that he's actually not, though Wolff points out that his use of it is in line with an existing sense of it, but to my knowledge that sense is only used by ignorant American capitalists, not self-identified socialists); what is "centrist" or not; and whether Bernie's Medicare-for-All plan is the best plan.

On the first issue of whether Bernie's use of the term socialism is politically expedient, I'm ambivalent about it. Republicans would call him "socialist" anyway, they would call any policies like his "socialist", and because they control the propaganda machine, that's what increasingly many Americans think "socialism" is, and increasingly think is actually a good thing not a bad thing. So it seems like just pragmatic identification with the label people use to mean what he is for, to me. It does come with a bunch of pejorative baggage, but since the label would be applied to him anyway, I don't really see the harm (and maybe even some benefit) in owning the word. Reclaiming it if you will. "We're here, we're 'socialist', get used to it."

On the second issue, "centrism" is relative to one's Overton window, and they clearly have different ones. The mainstream American Overton window is from Republicans on the right to establishment Democratic party leadership on the left, so within that window, establishment Democrats are left, and "centrists" are somewhere between them and Republicans. By that framing, Krugman is clearly "far left". But there are plenty of views even further left than that, that have long since been popular in Europe and are increasingly popular in America today, and from that point of view Krugman and establishment Democrats are "centrist". I personally consider even that further-left viewpoint "centrist", in a good way -- there is still further left than that that one could go, but that would be too far left -- but even from that far-widened-to-the-left Overton window I think in, I kinda dislike this attacking of establishment Democrats and "centrists" from the left. I'm a big-tent kind of guy, and I think anyone to the left of the current center of power should be on the same side for so long as it takes to pull that center of power leftward, and only as people in that big tent start to fall right of the new center of power should they be attacked from those further left of them.

As for Medicare For All, I am fine with Bernie's proposal, but I don't think he's going to get it done exactly as he wants it (because other politicians will stand in the way and at best some kind of compromise will be made), and I don't think it's the ideal solution either, either pragmatically or ideologically. I'm a kind of libertarian socialist, so while I'm okay with a limited state putting limits on capitalism to pro tem, I prefer to keep as much choice in the hands of people as possible while doing so. My ideal health care solution (for within the present political system, not in my utopian world) would be to give everyone a stipend of however much Medicare costs per person, charge all Medicare users that much to be on the program (so those who are currently on it see no net change), and allow anyone to buy into it with that stipend, or to spend that on an alternative if they really want; and then make Medicare good enough that most people wouldn't want to, if it's not already. Halfway between a public option and Medicare-for-All, I guess, because private insurance is not banned and nobody has to buy into Medicare, but everyone receives public funding for their insurance and anybody can buy into Medicare. Possibly make Medicare the default, with easy opt-out, so everybody who currently has no insurance just automatically gets Medicare for free, but anybody who really wants to keep their current insurance can opt out of that and spend their stipend on their current insurance instead. -

The Road to 2020 - American ElectionsHe's a billionaire transparently trying to buy his way into the presidency, with no consistent ideological positions, with a known history of racist and sexist comments and political actions, who is awkward and incompetent at public speaking. Sounds like a Trump clone to me. What do you see about him that's different?

-

The Road to 2020 - American ElectionsAll the Democratic candidates are a significant improvement. — Relativist

Even Bloomberg? -

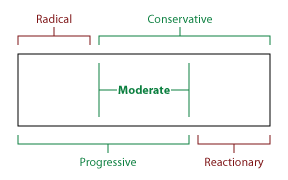

The Road to 2020 - American ElectionsThe old word for "centrism" was "reformer", someone who had beliefs different from the status quo but believes it's only gradual step-by-step changes that will yield the best results. — boethius

I think there's two important things that need to be distinguished here: the place on the political spectrum one is pushing toward, and how hard one is pushing toward it. To my mind, a "centrist" is someone who is pushing toward (what they perceive as) the center of the political spectrum. What you're describing by "reformer" is what I would instead call a "moderate", which is someone who is progressive but not radical, conservative but not reactionary, someone who wants change, but not reckless change, cautiousness, but not hyper-cautiousness.

-

Against NihilismThe "those who [think/feel] differently are incorrect, relative to that group" part, the the treatment of different groups as each correct relative to themselves and not in need of reconciliation to some universal standard, are the defining features of relativism and subjectivism. Someone who tries to get everyone who disagrees to come together and figure out something that everyone should agree to is not a relativist at all. That's exactly what objectivism is.

-

Plantinga: Is Belief in God Properly Basic?Correct, and that's exactly why foundationalism is bullshit (not in the technical sense). "Everything needs a reason", except for these things that obviously don't. Well then why isn't God or the Great Pumpkin or any other nonsense "obvious" enough? If you ever stop to say something is without need of justification, you're saying that it's beyond question, and therefore asking anyone who might disagree just to take your word for it, on faith. Foundationalism is equivalent to fideism, and consequently anti-rationalist. Critical rationalism is the only sound rationalism that doesn't fall either into fideism or an infinite regress to nihilism.

-

Against NihilismSo your argument against Nihilism is purely a pragmatic one. — khaled

I thought I had explicitly said that, but apparently not. I explicitly meant it in any case. I should probably add a small bit explicitly saying it.

You can't logically respond to the people that choose to "give up". — khaled

No, but I can point out that that's all they're doing. If they don't want to try to figure out what it real or moral, that's their choice, but them choosing that action doesn't mean that it is not possible to figure out what is real or moral, just that they're not trying to do so.

That's where the "for no reason" part comes in. They haven't shown that everyone should give up, that there is no hope, that trying is pointless. They have just elected not to try themselves. Which is their choice, but they haven't provided a reason why others need to choose likewise.

The very next essay (in the new order, or two essays prior in the old order), Against Fideism, is all about needing a reason to make an assertion to others; and the essay after that (in the new order, or the very next essay in the old order), Against Cynicism, is all about not needing a reason just to choose something for yourself. So nihilists are free to give up if they want, but if they want to tell anyone else that giving up is the thing to do, they'll need a reason, and their very nihilism deprives them of any reasons.

But how is that different from the initial position you disagreed with of saying that the closest we can get to objective morality or reality is whatever the group agrees with? — khaled

Relativists say that whatever a majority of some thinks (their beliefs or intentions) is correct, relative to that group, and those who think differently are incorrect, relative to that group.

Subjective idealists say that whatever a majority of some group feels (their perceptions or desires) is correct, relative to that group, and those who feel differently are incorrect, relative to that group.

I say that whatever everybody unanimously experiences (their senses or appetites) is correct, and if there isn't unanimity of experiences, people need to replicate others' experiences for themselves, and if they run into difficulty doing so, then there is some qualification that needs to be added to their model of what is objectively correct to account for those differences between the people doing the experiencing.

Thoughts and feelings are interpretations. Experiences are not. The three blind men touching the elephant each feels like (perceives that) they're touching a different thing, and none of them are correct, but the objective truth of what they are actually touching still accounts for the senses they all experience. The hard part is coming up with a model that does account for all their different experiences.

I pretty much said this in the essay already:

But rather than the perceptions and desires that underlie those views, which can contradict from person to person because they are constructed in the different minds of different people, I propose instead attending to the more fundamental underlying experiences that give rise to those perceptions and desires, free from the interpretation of the mind undergoing them.

Etc. It sounds like you already read that part, but didn't get it. -

Against TranscendentalismBased on feedback from these threads here, I have rearranged the first four essays of the Codex into a different order. This essay, Against Transcendentalism, is now the last essay of this series of four, because the first two are now Against Nihilism and Against Fideism, followed by Against Cynicism which is a followup to Against Nihilism, and then this one, which is a followup to Against Fideism. This is also in a way the most substantial of the four essays, in that rather than just establishing that there are answers to be found and not to take anyone's word for what they are yet to give everyone the benefit of the doubt, this one actually finally gives a direction as to where to look for those answers.

-

Against CynicismBased on feedback from these threads here, I have rearranged the first four essays of the Codex into a different order. This essay, Against Cynicism, is no longer the last essay, but now falls after Against Fideism, because it immediately addresses a bunch of objections that arise when people read that essay, and before Against Transcendentalism, which is now the last essay of this series of four.

-

Against FideismBased on feedback from these threads here, I have rearranged the first four essays of the Codex into a different order. This essay, Against Fideism, is no longer the first essay, but now falls between Against Nihilism and Against Cynicism, because the former is lower-hanging fruit than even this, and establishes better up front what I am not arguing for in this; and the latter immediately answers a bunch of the objections that seem to arise in response to this.

-

Against NihilismBased on feedback from these threads here, I have rearranged the first four essays of the Codex into a different order. This essay, Against Nihilism, is now the first essay, as I figure being against nihilism is the lowest-hanging fruit, and will get more people on board quicker than starting out with the other core principle, against fideism.

-

Bernie Sandersreinforcing what they believe and convinced that they have a lock on truth and knowledge -- when in reality, they're parroting propaganda. — Xtrix

I discuss this phenomenon and its relationship to the origin of religion in my essay On Academics, Education, and the Institutes of Knowledge. On my view, these kinds of “truther” bubbles are formally identical to cults, which in turn are formally identical to small, unpopular religions. -

Bernie SandersBernie calls himself a "democratic socialist".

The policies he promotes are what get called "socialist" in America.

Those policies actually fit the technical definition of social democracy (which is not a kind of socialism), not democratic socialism, or any kind of socialism. They have nothing to do with capital being owned by those who use it, they just provide a band-aid over the worst excesses of capitalism.

But most Americans don't know or care about that. They just hear something called "socialism" (which other Americans do to policies like Bernie's) and think it's authoritarian. So Bernie prefaces it with "democratic" to be clear that he's not authoritarian in promoting the things Americans call "socialist".

It's the practical way to communicate his stance to the average American, even if it's technically incorrect. -

Bernie Sanderssalty — NOS4A2

Why does it only seem to be right-wing manchildren who use this new slang? -

Bernie SandersRight, because they can’t vote for Sanders. — Wayfarer

Of course they can. The worry is that they won't; that Biden or Bloomberg are closer to Trump than they are to Bernie (I think that that's actually true; there is a huge overlap between the two mainstream parties, and the right wing of the Democrats is closer to the right wing of the Republicans than it is to its own left wing), so people who prefer that kind of candidate would prefer Trump over Bernie.

The thing is, it's not moderate Democrat voters who prefer right-wing Democrats over Bernie, it's establishment Democrat leadership, who presume to speak for moderate Democrat voters, who do. The voters themselves overwhelmingly favor the policis that Bernie pushes, sometimes even when they identify as "conservative". People just don't know what labels mean, and everybody wants to think of themselves as "moderate" and "independent"; but most of those people who think of themselves that way like the things Bernie is proposing, even if they say they don't like "socialism" or the "left wing", etc. -

How many would act morally if the law did not exist?To be clear, I still have abnormally high levels of passion. Aside from working my full-time job and generally keeping my life going ahead full steam, I've "written two books" (eh...) and "made a video game" (kinda) over the past three years. I'm just far less optimistic and energetic and bright and hopeful than I used to be, and I see that downward trend as leading toward what I've observed many other people had already become decades earlier in their lives; and from that, I conclude that the thing that makes so many other people so dulled and lifeless isn't some flaw internal to themselves, but just the result of life grinding them down a lot earlier than it did me.

And consequently, that we can get people to recover that childlike positivity by helping them to heal from the traumas of life. The penultimate essay of my philosophy book, On Empowerment, is all about that. -

How many would act morally if the law did not exist?While I certainly agree that concern for morality is important, life has beat me down when it comes to being optimistic about MOST people being INTERESTED enough to actually engage and analyze their morals (they would agree that morality is very important to them, but as soon as we begin to question and analyze, they want no part of it). — ZhouBoTong

May I humbly suggest that a likely reason that people are like that is that life has beat them down too much. Children are naturally curious and love to learn, until life beats that out of them. I was fortunate to have maintained many (positive) child-like qualities into my early adulthood, and other adults around me seemed like they had been blunted somehow. I used to think that that was because I was better in some way than them, but as I've gotten older and older, life has begun to blunt me in similar ways that I remember seeing in others back then, and I realize now that most people just suffer too much trauma (at the hands of people who are themselves reacting to their own traumas, generation over generation) in their lives to maintain that child-like "innocence", that desire and ability to learn and teach and be helpful and useful to others. -

Plantinga: Is Belief in God Properly Basic?The content of ordinary empirical beliefs is more or less an expectation of having those same empirical experiences in similar contexts; the expectation of the sensations of experiencing a tree is the content of a belief that a tree exists; "the tree", that we believe exists, is whatever it is that gives rise to such sensations, and that is the whole of its being. So if belief in God is similar, and people's perception of God is the warm fuzzy feelings they get when praying or having religious experiences etc, then is "God" just whatever it is that gives rise to those feelings, and belief in God just an expectation of such feelings occurring in those contexts, etc? Is "God is love" more literal than it's usually taken to be, and "God" just is a kind of lovey feeling? That's basically theological noncognitivism right there, which is fine with even most atheists so far as I know. Nobody expects to go searching the world for the object that the feeling of love corresponds to, asking "does love really exist or is it just a feeling?" doesn't make any sense, there is nothing more to love than people feeling love. So if our conception of God is just of a feeling like that, then there is nothing more to "God" than people feeling like that. But that really doesn't mesh at all with the kind of "God" described in any holy texts, who himself has feelings and does things other than just give rise to feelings in people. It's the existence of that kind of thing, that does that kind of stuff, that's in question.

-

Plantinga: Is Belief in God Properly Basic?

What is "the world"? The only idea of a world I have is from my senses. Sometimes what I think they're telling me doesn't line up with other things I think they're telling me, but all I have to work with is what my senses seem to be telling me, and the best I can do is try to make consistent sense (no pun intended) of that as a whole. I don't have a foundational, basic belief that my senses are delivering an accurate view of something else beyond what I sense; what I sense just is what seems to be, and though it might not be, I have no reason to doubt that seeming unless other senses seem to contradict it.I beg to differ. Here's a couple:

- belief that our senses deliver a functionally accurate view of the world — Relativist

What difference is there between an "external" world and, I presume, an "internal" one? Is the world I describe above an internal one or an external one? How could I tell the difference between those (nominally) two things?- belief that there is an external world (i.e. solipsism is false).

Don't get me wrong, I think that something like the views you espouse here (empiricism and realism) are correct, and very core, central views that can support a bunch of different more specific views on other things, so if foundationalism were true they seem like they would make good basic beliefs. But foundationalism isn't true, and the reason to retain (not adopt) these beliefs is because there are no good arguments against them, and there are good arguments against doing otherwise. The same is true, FWIW, about anti-justificationism: there are good arguments against justificationism, and no good arguments for it, so it's rational to reject it and retain its negation. These three things (empiricism or more generally phenomenalism; realism or more generally objectivism; anti-justificationism or more generally what I call "liberalism") plus anti-fideism (which I call "criticism") are the four core principles of my entire philosophy, but they're still not properly basic beliefs. -

Plantinga: Is Belief in God Properly Basic?I skimmed it to see if he was actually going to argue against foundationalism or not, and from what I can see he does not, only arguing that it does not rule out taking belief in God to be properly basic. My counterpoint is that foundationalism itself is wrong (as are all forms of justificationism, including coherentism and infinitism as well) and consequently no beliefs are properly basic. Proper rationality isn't about believing nothing unless it is properly justified from the ground up, but about only believing things that cannot be critically ruled out. (Which belief in the usual conception of God can).

(Coincidentally, my latest thread is mostly about exactly that topic.) -

Against NihilismYou ask where the ideas have been had before, I am simply providing you the answer that the idea that we can still function, that it's still worthwhile to keep an eye out for the truth, even if we don't have it, goes back, at least, to the Hellenistic philosophers, is the foundation of skepticism, and is also a Socratic theme (though debatable Socrates is a skeptic as it later developed, you are not really taking a skeptic position, only presenting part of a skeptical argument, elsewhere it very much seems you are claiming the arguments you present are true and you believe them to be so; so, more akin to a Socrates that claims to know much more). — boethius

Thank you for that.

I'm a moral relativist/nihilist and I've argued with a number of people on the topic, your summary opinion of how we don't know therefore there's no more reason to be a nihilist than not be one is probably the second or third most popular counterargument from my experience.

I think most of your issues with moral relativism are all pretty common, at least with people who don't like it. — Judaka

Thank you for that too.

What do you mean by what actually hurts them? What is this actual good that you are here to tell us all about? — BitconnectCarlos

As I said, that's getting way ahead of the game and will be answered in detail in later essays, some of which I've already linked, and you refused to read. For a short answer for now, it's very close to what is meant by interests (as opposed to positions) in principled negotiation, and as I think I said already, it's analogous to the difference between beliefs and observations in science. You find out if something actually hurts someone (or vice versa, though I can't think of unambiguous terminology for that as "pleases" could mean the wrong thing) by standing in their circumstances and seeing if it hurts (etc) you, after controlling for differences between you if necessary. Just like you verify an observation by repeating an experiment, controlling for differences in instruments (including natural senses) as necessary. -

Against CynicismThanks for the feedback again. I don't follow how you say I reason and support this position well, but then also don't give a logical reason. The reason I give against cynicism here is the entailment of nihilism, and I gave reasons against nihilism in the previous essay. So if those reasons against nihilism are good in that essay, and this essay is right that cynicism entails nihilism, then those reasons against nihilism are consequently reasons against cynicism.

Also, I know that this part so far is pretty boring and not very interesting, but this is all just laying the groundwork for the more interesting stuff to come later. I'm going to be arguing for things like "the universe is made of math", "everything is physical", "everything has a mind", the right way to do science and education, ethics, the nature of free will, anarcho-socialism, and meaning-of-life stuff, by the end, and all of it is going to depend on these basic early principles.

Or as I wrote in the first and last paragraphs of the Introduction page:

When laypeople think of philosophy, the first thing that comes to mind is often a vague "meaning of life" type of question. Besides that, people will most often think of big social questions regarding religion or politics, or perhaps more psychological questions about consciousness or free will. In these essays I will address all of those topics. But to do so I must first address more general topics about knowledge and reality, justice and morality, and even more abstract topics of art, math, and the very language we use to discuss any of this. And before even that, I must addressing the nature of philosophy itself, and the different possible ways of broadly approaching it.

...

That general philosophical view is the underlying reason I will give for all of my more specific philosophical views: everything that follows does so as necessary to conform to that broad general philosophy, rejecting any views that require either just taking someone's word on some question or else giving up all hope of ever answering such a question, settling on whatever views remain in the wake of that rejection. In the rest of the essays that follow, I will lay out more specifically what my positions are on a wide variety of particular philosophical topics, ranging from abstract matters concerning language, art, and math; through descriptive matters concerning reality and knowledge; through prescriptive matters concerning morality and justice; and finally on matters of empowerment and enlightenment, inspiring the pursuit of goodness and truth, practical action, and the meaning of life. -

Against NihilismSo, just to provide some context, in the discussion me and Pfhorrest were having earlier we were roughly defining good as "social contentment or satisfaction" or something along those lines. — BitconnectCarlos

I make a very important distinction between intentions or desires, and appetites, in my ethics. It's analogous to the distinction between beliefs or perceptions, and sensations, in physical sciences. What people believe, or think they're seeing (their interpretation of their observations), is not relevant to truth. What they actually observe is. Likewise, what people think ought to be the case, or what they want, is not relevant to the good. What actually hurts them is, though.

It would help if you would actually read the entirety of what my position is before arguing about it, although we are getting way, way ahead of ourselves here, as this thread is just about one essay establishing one principle that will be employed in many places later on. All of the follow questions about "but what is that objective morality like, what's its relationship to justice, who gets to make the decisions", etc, will be addressed later.

This seems incompatible with the content of your essay which concludes there is "a much better chance of getting closer to finding them, if anything like that should turn out to be possible, if we try to find them". — boethius

The "right now" part that you quoted is important, as is the part immediately following that that you didn't quote:

...especially the ones that have already been long-debated (though I'd be up for debating the truly new ones, if any, at a later time)

I'm don't want knee-jerk rehashing of very old arguments to get in the way of critiquing the form and presentation of this particular project first and foremost. When the whole project is polished and done, then I'm happy to debate its merits as a whole.

You are "open to find answers, whatever they may be and even if they can't be fond" ... as long as they are "not some transcendent kind of reality or morality". — boethius

Technically in this essay by itself I'm not arguing against transdentalism, I'm just stating that I'm not arguing for it just by being against nihilism. But in another essay I am arguing against transcendentalism, precisely on the ground that answers about trancendent things can't be found. And in this essay I don't say "even if they can't be found", I say that if we're not certain either way that they can or can't be found, we should try to find them. That's entirely compatible with not looking for them in places where we're sure they won't be found. -

Against CynicismWhoops! Made a small typo: "cynicsm" instead of "cynicism". Fixed now. Thanks!

-

Bernie SandersDo you honestly think Sanders will be able to fulfill his promises, or is that beside the point - i.e. you just want someone with the right set of concerns? — Relativist

That's my take. The president alone doesn't, and shouldn't, have the power to make changes like this themselves. So legislative and judicial seats are ultimately way more people than the presidency. But the president sets the agenda for their entire party, so having a president like Bernie being in charge is a useful first step toward change in the right direction. -

The Road to 2020 - American Electionsrent and interest which create a pressure away from center (pushing the rich richer and the poor poorer) in proportion to the relative scarcity — Pfhorrest

It occurs to me, to make this a little more philosophically relevant, that this is essentially an issue of dealing with the Lockean proviso. The Lockean system of property and contracts that underlies the whole modern world works great so long as there is "enough and as good" left over for others to go and and get for themselves, as Locke himself said. So for people who live in Bumfuck Nowhere where there's plenty of equally shitty land for hundreds of miles in every direction, there isn't a problem of how to ethically handle scarcity, because there effectively isn't scarcity; that's why I could easily buy several suburban blocks of land in California City, where nobody wants to live. When there isn't enough and as good to go around, though, then the economic system is tested, and possibly breaks down if it isn't built to handle that right. I think rent and interest are the flaw of capitalism that causes it to break down in the face of scarcity. It works fine enough when there's a go-to solution to scarcity: go make more. But as of this writing, we can't yet make more land, and there it breaks down. -

The Road to 2020 - American ElectionsJust curious, what's your solution to this problem? Should homeowners not be allowed to decide which price to sell at? — BitconnectCarlos

Nothing so crude as that. I think the problem traces back to much deeper systemic problems involving rent and interest which create a pressure away from center (pushing the rich richer and the poor poorer) in proportion to the relative scarcity (demand per supply) of whatever the market is for. That would undoubtedly turn into a very long argument (that I think we might have had already elsewhere), but the short version of the conclusion of it is:

The existence of rent and interest (caused by government enforcement of the contracts that create them) drives up demand for housing by the rich, who view it as an investment vehicle, and thus drives the price of it out of range of the poor, who need it to live in, and must instead rent and borrow, fueling the returns on those rich people's investments, and perpetuating (and exacerbating) the cycle. The world that I envision in place of what we have now is ultimately one very similar to what we have now, but where all payments for housing go toward equity, you can't profit from letting someone else borrow your property so instead your best option is to sell it, but for that same reason nobody buys housing for someone else to live in just as an investment anymore, and thus the cost of housing comes down to what the remaining market of people who just need it to live in can bear, and thus that housing ends up owned by the people who live in it.

I have extensive thoughts on the exact details of how a world like that would be implemented and the objections you're probably screaming right now can be circumvented, but that's a very long conversation because I have to unravel all of the assumptions everyone takes for granted and why they don't have to be that way. But the short version of that is: starting buying something (in installments) needn't be more difficult than starting renting something, nor do the size of the payments need to be different, and if what you want is the convenience of renting, you're always free to walk away from the thing you've been paying for and let the seller keep it and your money, like the owner would if you were renting. So if people want something like rent, they can easily get it, but if someone would rather be buying something and currently has no option but to rent, under my scheme they would accumulate equity and eventually get to stop paying.

I think you're viewing it wrong. I want to show you a podcast a successful real estate investor sent me. The goal isn't to pay off the mortgage ASAP and therefore have no more payments (which even then isn't true you'll always have payments.) But seriously that money could be invested in much, much better places than in a house.

The podcast that was sent to me was "Get Rich Education: With Keith Weinhold" it's an apple podcast it's #6 "Here's why you aren't financially free" and it directly addresses this question of financially free vs debt-free. — BitconnectCarlos

I never listen to podcasts, so I don't know how to find or listen to that, and I'd really prefer a text source for time efficiency if you have one, or can at least summarize it.

In any case, I am currently investing that money somewhere other than a house, and I have considered the possibility of, rather than putting that money into equity when it's enough, using the returns on those investments to offset the cost of rent or mortgage interest. Basically grow my investments until they pay my current rent (even that is a ridiculous bar to reach right now), and then allow myself to move somewhere with higher rent (or mortgage interest) once I have the return on other investments to offset that. That does sound like a better solution, in the context of our current economic system at least, but I'm not certain whether it will delay the time before my girl and I can move in together and thus get married even further than the current plan. -

The Road to 2020 - American ElectionsBack on actual topic (maybe this housing stuff should be split into its own thread?), after this weekend's Nevada caucus FiveThirtyEight is showing Bernie with basically even odds on getting the nomination by majority vote, with Bloomie tanking hard now, so Biden back to heir apparent should it come to a brokered convention. I agree that Bernie/Warren is the way to go, and I hope that just prior to the convention she throws her delegated to Bernie and he picks her as his VP. Having the first female VP would attract a lot of the crowd that were behind Hillary just for the milestone factor, while simultaneously pleasing a lot of the Bernie supporters as her policy positions are quite similar to his in many ways and she's got similar fire and passion for justice too.

-

The Road to 2020 - American ElectionsI don't fully follow your numbers. You save 75% of your income — Hanover

I don't know where you got that 75% figure from. Maybe the bit where I said somewhere earlier about only spending a quarter of my income disposably? Which both you and Carlos seem to have misinterpreted, but differently: I meant that that is the portion of my take-home income which is neither dedicated to fixed costs that I can't reduce (basically rent and bills) nor left over to save. That doesn't mean it's the only money I spend (like you seem to interpret it), nor that that's my free happy fun time party money (like Carlos seemed to interpret it), but that it's the part of my budget that's flexible, in that I could spend more or less on it. It's basically split pretty evenly between food and gas, as I said earlier, and all other non-fixed irregular expenses (like car repair and dental work, etc) make up the negligible rest of it. As I said earlier, my budget is roughly 1/8 food, 1/8 gas, 1/6 bills (mostly medical insurance), 1/4 rent, 1/3 savings toward future housing.

This points to either (1) low income and fear of a high mortgage — Hanover

I have a statistically high income, as I've repeatedly said; I make about the mean income, which is twice the median income, or nearly four times the mode income, and falls at around the 75th percentile of incomes.

I am afraid of a high mortgage inasmuch as that means spending even more on interest than I am already spending on rent, because at my current rate of savings it's not entirely clear that I will ever be able to save enough to pay off a house, and if I was mortgaging with a higher interest than my current rate, then that rate of "savings" (diverted directly into equity on the house, which is fine since the savings are earmarked for a house anyway) would be even lower and make it pretty much certain that I will never finish paying anything off. In order to avoid that, I need to borrow little enough that the interest does not exceed my current rent, which means paying off a huge portion of the house up front.

Look at the numbers: currently about 25% of my income goes to rent and 33% goes toward eventual equity. If I started mortgaging the cheapest place in the area now, the interest alone would easily be over 50% of my income, leaving at most about 8% to go toward equity, probably less. Meaning it would take about four times longer to pay something off (which means effectively never as I barely expect to pay anything off in my lifetime as it is now).

(2) unrealistically financially conservative. — Hanover

What is unrealistic? When I complain about this housing issue everyone always says "work harder, work smarter, spend less, budget more". I've spent most of my adult life feeling guilty for not working hard enough, not spending little enough, because of people saying things like that. It wasn't until my current girlfriend (of nearly a decade now) talked me into believing that I could fit things into the budget like a trash can for the bathroom, or a new vacuum cleaner that isn't duct-taped together, that I stopped living like a starving student and working myself to death and decided to actually enjoy life a little bit along the way instead of waiting until I retire to live... and now Carlos is telling me I need to get a side hustle and budget more. So which is it, too conservative or not conservative enough? Should I go back to living off stale bread and water again so I can allocate whatever 10% or so of my income I spend on food toward saving for housing instead, or should I let myself splurge on a place big enough that I can marry and live with my girlfriend at the cost of spending more than half of my income on mortgage interest alone and therefore dying in the street when I'm too old to pay rent anymore?

(3) credit problems — Hanover

I have excellent credit. Well, technically a few points shy of the top "Excellent" category of FICO score, but zero debt, decades of on-time payments, etc.

or (4) residing in a very affluent unaffordable area. You seem to suggest it's 4, but that you're in a trailer suggests otherwise (sorry, but true). What area are you from? — Hanover

As I've said, I'm in Ventura county, California. And yes, I live in a trailer park, because that was the most economical way to get out of renting a bedroom in someone else's house full of ever-changing assholes I had no control over, which is how I lived my entire adult life prior to that. Market rate on a 1br apartment about the size of my trailer runs well over 2X, easily 3X my lot rent here. Because MH lots are rent-controlled, I've managed to keep my costs down close to what they were on the bedroom before, while the cost of even a rented bedroom like I used to live in now easily goes for nearly 2X what I'm paying here.

And this is not a problem restricted to just my "city" (I don't live in a city, I live in unincorporated countryside) nor my county. This is a problem that affects pretty much the entirety of the populated parts of the state. There are some places where you can buy a plot of land for $1000, but that's for good reason. Everywhere people actually live and jobs and civilization are found, it's like this. Looking at neighboring states, it doesn't seem much better; my job relocated to Oregon (I telecommute now) and the boss was telling me to move there too because it was so much cheaper, but I looked at the prices and it's really not, and the weather there would leave me an emotional wreck, never mind leaving behind everything else in my life, including the woman I want to marry who would be even more ruined by leaving our home than me.

It might also be 2, based upon your statement that you think the goal of buying is to outright own. The goal of buying is to accumulate equity and hence wealth, as well as to get tax benefits, regardless of whether you eventually pay off the mortgage. — Hanover

That is completely backwards. The point of wealth is to own the things you need so you don't have to pay someone else to borrow them from them. I am accumulating wealth, much faster than I would be if I was mortgaging a house right now (see the math above), and I am accumulating that toward the goal of eventually getting to stop paying to borrow someone else's land to live on. And I am succeeding at that far better than a supermajority of people, and yet still not sure I will ever actually succeed, which tells me that this is not a problem with me, this is a systemic problem.

Look at it this way. It seems to me a fairly reasonable, quite minimal thing to expect that:

- for any "commutable area" (an area of such a size that a typical person, i.e. a person making about the mode income, could reasonably live on one end of it and work on the other end of it with the kind of transportation affordable to them, which I'd estimate is about a 100 mile diameter with today's technology and infrastructure);

for any such area, ...

- the typical person in that area (meaning again, someone making about the mode income, which the statistics tell me is about the income of a full-time minimum-wage job for the US nationally, though the California minimum wage is significantly higher and yet the median income is about that of a full-time CA-minimum-wage job, which suggests to me that most people here are under-employed);

such a person ...

- should be able to finish paying off housing sufficient for at least one person (or two if we expect them to have children, which would mean a bathroom, kitchen, an open area like a living room, and one or two closed areas like bedrooms, which means, assuming about 10ftx10ft per room on average, obviously with some variance between them, about 400-500sqft in total);

should be able to pay off such a house ...

- by the time they could have grown kids (so mid-late 30s to early-mid 40s).

I am about that age. I have always made at least twice that income, and currently make about four times it. I finally own a structure about that size, but on rented land, and it's uncertain if I will ever be able to afford anything on its own land. My girlfriend is also that age, has always made about that mode income, and owns nothing whatsoever. My parents are 25 years older than us and they both own practically nothing (my mom literally nothing, my dad is complicated but suffice to say he won't leave any estate that I could inherit). Her parents are more like 30-35 years older than us and they just recently, as their grandkids are almost grown, finished paying off something about twice that size (so appropriate for a couple with children). And that situation her parents worked out is an enviable dream to our generation, but yet still pretty unreasonable by any objective standard; they spent basically their entire lives dedicating the bulk of their income just to the task of not owing anybody money for the right to exist somewhere. But they at least succeeded, whereas it's not clear that I, or the 75% of people who are worse off than me, ever will.

And that is a sign that something somewhere has gone horribly wrong. I have my ideas about what, but arguing for those ideas isn't nearly as important as people just recognizing that there is a problem in the first place. -

The Road to 2020 - American ElectionsFrom the picture you've been painting you seem to be doing generally alright. Sure, maybe a 600k house is a little out of your range but you seem to be financially secure with a nice emergency fund and decent savings. You mentioned you have disposable income and you're able to go out to eat whenever you want which is really nice. — BitconnectCarlos

Yeah, I do have it much better than a lot of other people, which is part of the point I’m making about the problem being systemic. And part of why I have it so much better is because I’m constantly fighting and sacrificing to beat the system, living in shitty conditions to stay way below market costs so I can otherwise have this security, where if I just went out and rented a market-rate apartment I’d be scraping by check to check.

And the point of complaint isn’t that a specific price point of house is out of my reach, but that ANY house available for purchase (not a MH on rented land) in a very very broad area is out of my reach, and consequently out of reach of almost everybody else in that area, who mostly do barely scrape by check to check. I can easily buy a big enough structure; a simple add-on to the MH I already own would suffice. But even an empty plot of land to park and build that on would cost hundreds of thousands, and you can’t get a mortgage on an empty plot of land, if anyone were even to sell one of the right (small enough) size.

It should not be an unreasonable stretch goal for most people to own a place to live some time before they die. But evidently it is, and somehow everyone has normalized this concept of being indebted to whoever owns their land from adulthood to grave. It’s insane.

I understand you want the house but you know the mortgage on that thing is going to be a constant stressor and much more than what you're paying now for the land — BitconnectCarlos

If I tried to mortgage right now it would be yeah, which is why I need to save a ton of money for a huge downpayment in order to make it manageable. I basically have to pre-pay-off over half the house in order for “buying” (mortgaging) to not delay the day I have something paid off even longer than renting + saving already will take.

I live in a 1 bedroom apartment so I figure we probably live in similarly-sized areas and I'm honestly perfectly happy with mine. I think even if I had a partner 700 square feet is fine for me. — BitconnectCarlos

Your apartment is about 2/3 bigger than my trailer, so yeah if I had that much space it would be fine to live together. The difference between your place and mine is almost 3X the size of my girlfriend’s rented bedroom.

It's just hard to me to try to sympathize with you when you're able to go out to eat whenever you want. — BitconnectCarlos

See above about that only being possible because I’m living way below market rates and making way more than other people in an attempt to beat this system (and still not sure I will ever succeed at that). Most other people in the area are not so fortunate. Which is my whole point: I’m not the sob story myself, I’m just a clear demonstration of how much of a sob story the whole system is if EVEN SOMEONE LIKE ME may never end up owning just a place to sit and starve to death without getting kicked out when I inevitably run out of steam and stop kicking so much ass. -

Against NihilismThe primary divide within normative ethics is between consequentialist (or teleological) models, which hold that acts are good or bad only on account of the consequences that they bring about, and deontological models, which hold that acts are good or bad in and of themselves and the consequences of them cannot change that. The decision between them is precisely the decision as to whether the ends justify the means, with consequentialist models saying yes they do, and deontological theories saying no they don't. I hold that that is a strictly speaking false dilemma, between the two types of normative ethical model, although the strict answer I would give to whether the ends justify the means is "no". But that is because I view the separation of ends and means as itself a false dilemma, in that every means is itself an end, and every end is a means to something more. This is similar to how the views on ontology and epistemology I have already detailed in previous essays entail a kind of direct realism in which there is no real distinction between representations of reality and reality itself, there is only the incomplete but direct comprehension of small parts of reality that we have, distinguished from the completeness of reality itself that is always at least partially beyond our comprehension. We aren't trying to figure out what is really real from possibly-fallible representations of reality, we're undertaking a fallible process of trying to piece together our direct sensation of small bits of reality and extrapolate the rest of it from them. Likewise, to behave morally, we aren't just aiming to use possibly-fallible means to indirectly achieve some ends, we're undertaking a process of directly causing ends with each and every behavior, and fallibly attempting to piece all of those together into a greater good.

Perhaps more clearly than that analogy, the dissolution of the dichotomy between ends and means that I mean to articulate here is like how a sound argument cannot merely be a valid argument, and cannot merely have true conclusions, but it must be valid — every step of the argument must be a justified inference from previous ones — and it must have a true conclusion, which requires also that it begin from true premises. If a valid argument leads to a false conclusion, that tells you that the premises of the argument must have been false, because by definition valid inferences from true premises must lead to true conclusions; that's what makes them valid. If the premises were true and the inferences in the argument still lead to a false conclusion, that tells you that the inferences were not valid. But likewise, if an invalid argument happens to have a true conclusion, that's no credit to the argument; the conclusion is true, sure, but the argument is still a bad one, invalid. I hold that a similar relationship holds between means and ends: means are like inferences, the steps you take to reach an end, which is like a conclusion. Just means must be "good-preserving" in the same way that valid inferences are truth-preserving: just means exercised out of good prior circumstances definitionally must lead to good consequences; just means must introduce no badness, or as Hippocrates wrote in his famous physicians' oath, they must "first, do no harm". If something bad happens as a consequence of some means, then that tells you either that something about those means were unjust, or that there was something already bad in the prior circumstances that those means simply have not alleviated (which failure to alleviate does not make them therefore unjust). But likewise, if something good happens as a consequence of unjust means, that's no credit to those means; the consequences are good, sure, but the means are still bad ones, unjust. Moral action requires using just means to achieve good ends, and if either of those is neglected, morality has been failed; bad consequences of genuinely just actions means some preexisting badness has still yet to be addressed (or else is a sign that the actions were not genuinely just), and good consequences of unjust actions do not thereby justify those actions.

Consequentialist models of normative ethics concern themselves primarily with defining what is a good state of affairs, and then say that bringing about those states of affairs is what defines a good action. Deontological models of normative ethics concern themselves primarily with defining what makes an action itself intrinsically good, or just, regardless of further consequences of the action. I think that these are both important questions, and they are the moral analogues to questions about ontology and epistemology: fields that I call teleology (from the the Greek "telos" meaning "end" or "purpose"), which is about the objects (in the sense of "goals" or "aims") of morality, like ontology is about the objects of reality; and deontology (from the Greek "deon" meaning "duty"), which is about how to pursue morality, like epistemology is about how to pursue reality. In addition to consequentialist and deontological normative ethical models, there is a third common type, called areatic or virtue ethics, which holds that morality is about the character, the internal mental states, of the person doing the action, rather than about the action itself or its consequences. I hold that that is also an important question to consider, and that that question is wrapped up with the question of what it means to have free will. And lastly, though it's not usually studied as a philosophical division of normative ethics, there are plenty of views across history that hold that morality lies in doing what the correct authority commands, whether that be a supernatural authority as in divine command theory or a more mundane authority as in some varieties of legalism. That concern is of course wrapped up in the question of who if anyone is the correct authority and what gives their commands any moral weight, which is the central concern of political philosophy. So rather than addressing normative ethics as its own field, I prefer approaching those four questions corresponding to four kinds of normative ethical theories as equally important fields: teleology (dealing with the objects of morality, the intended ends), deontology (dealing with the methods of justice, what the rules should be), the philosophy of will (dealing with the subjects of morality, who does the intending), and the philosophy of politics (dealing with the institutes of justice, who should enforce the rules). I would loosely group these together as "meta-ethics" in a slightly different than usual sense, they being the questions necessary to answer in order to pursue the ethical sciences I propose above; in a way analogous to how the fields of ontology (about the objects of reality), epistemology (about the methods of knowledge), the philosophy of mind (about the subjects of reality), and the philosophy of academics (about the institutes of knowledge) — which we might likewise group together in a slightly unusual sense as "meta-physics" — address the questions necessary to answer in order to pursue the physical sciences. -

The Road to 2020 - American ElectionsGet a side hustle, make a budget, and maybe look into the tiny house movement. I'm also not sure what your IRA is invested in, but the S&P is a decent option. — BitconnectCarlos

I have a full time job already making significantly more than most people in my area never mind the country as a whole, I only spend a quarter of my take home income disposably and most of that is split between food and gas, I already live in what is effectively a tiny house (which doesn’t solve the problem of needing land to park it on), and my IRA is mostly in a S&P tracking index fund. None of this is new advice, though it would be good advice for someone who wasn’t doing it. My point is that I’m already doing every right, doing better than a supermajority of people, and I’m still facing an impossible uphill battle, which is a sign that something is systematically wrong that I personally am not responsible for single-handedly overcoming or else helplessly succumbing to.

Pfhorrest

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum