Comments

-

What do people think philosophy is about?I just added to the OP this for clarification of the intent behind this poll:

The impetus behind this question is reflecting on how at different stages of my life, prior to having actually studied philosophy, if someone asked me "what's your philosophy?" my answer would have been an answer to one or another specific sub-field of philosophy. For example at one point someone asked that question I basically told them that I believed in string theory, taking the question to mean roughly "what is real?". Another time half a decade later someone asked the same question and I basically described utilitarianism, taking the question to mean roughly "what is moral?" So I'm wondering what first comes to mind when most people hear "philosophy". -

On deferring to the opinions of apparent expertsIs your username "A Seagull" because you're just here to shit on everything?

-

On deferring to the opinions of apparent expertsI think you understood my example backwards. This isn't about you or me arguing with a creationist. This is about what if you or I are like the creationist? The reason I'm talking about the arguer rather than the argument is because the scenario that interests me here is when the argument is above one's head, when one is not up to following or critiquing the argument. Of course, if you can follow an argument, then address the argument not the arguer. This is about what if you can't follow it. What if you're the ignorant creationist and someone throws a wall of science at you proving you're wrong, but you're too dumb to understand it? Do you ignore the science you can't understand and go on being wrong, or do you accept what they say because they're obviously smarter than you and believe something without really understanding why?

My view has long been "when you can't work something out yourself, recognize the limits of your own knowledge and believe people who are clearly smarter than you", but I've almost never actually been on that side of the equation before, except in an educational setting where I've set aside the time and effort to dedicate to studying more and more until I can understand and critique the argument itself. But outside of the classroom a lot of people don't have the time or energy or opportunity or maybe just the intellectual ability to do that, to learn about every topic they're faced with until they can adequately understand explanations as to why they're wrong or else adequately argue that they're actually right. So now I'm questioning that long-held view. -

On deferring to the opinions of apparent expertsThat is my usual approach, which is what makes circumstances like this interestingly problematic to me: when I can’t follow the line of argument, but the person presenting it seems like someone who probably has a followable argument. I don’t want to be like the creationist who dismisses all the scientific arguments against creationism because they’re too uneducated to follow them, but it also seems wrong to just accept an argument you can’t follow because the person making it seems like they should know what they’re talking about. That’s really the thing that makes this seem an interesting problem to me, not so much my handling of people on this forum, but the general principle behind that and how it would apply to things like public education. If the ignorant creationist is too ignorant to follow the scientific arguments against him, should he ignore the science or accept its conclusions blindly? Obviously, ideally, he’d learn the science and then accept its conclusions with eyes wide open, but that’s a big undertaking, so until they’re able to do that (which may be never, depending on their circumstances and abilities), what should they do for now?

-

On deferring to the opinions of apparent expertsbelief is a form of knowledge. It is not absolute knowledge, but a form of it. Therefore all faith or belief is a form of knowledge as well. — god must be atheist

Other way around: knowledge is a form of belief. Justified true belief, traditionally, but it's recently come into question whether that is enough. But it's still necessary, even if not sufficient: to know something, it must be true, you must believe it, you must be justified in believing it, and maybe some other things too, still being debated. "Belief" is not a synonym for "faith".

Your username reminds me of how in the Lord of the Rings, the Elves, who openly perform what Men consider "magic", declare that there is no such thing as magic. Similarly, your username makes me imagine a being that many humans would call "God", declaring that there is no such thing as God. The resolution to both apparent paradoxes is that those with lesser knowledge see something mystical and supernatural, while the so-called "mystical" or "supernatural" beings themselves possess superior knowledge and know that everything about them is in fact perfectly natural and amenable to science. -

On deferring to the opinions of apparent expertsThis isn't meant to be passive-aggressive toward him, I don't have any problem with him personally, and it's not just about him. I genuinely thought this an interesting philosophical problem more generally, and didn't want to make it just about him. But I find it interesting that at least two people immediately jumped to the conclusion that it was all about him, without me naming him or anyone.

-

On deferring to the opinions of apparent expertsI find it interesting that this thread has been derailed into exactly one if the examples of this phenomenon I had in mind (math proving things about religion) without me even naming it.

-

What does Kant mean by "existence is not a predicate"?Kant was using what contemporary philosophers would consider slightly ambiguous language. "Predicate" is a linguistic term, and existence is certainly a predicate in that technical sense: you can say "X exists", and "X" is the subject and "exists" is the predicate.

What Kant meant was that existence isn't a property of a thing. It's not like you can give a list of all of the properties of a thing and "existence" will be one of them. It's even more the case that you can't bake "existence" into the analytic definition of a thing: in my philosophy class that covered this, we talked about the example of a "perfect pig", and listed a bunch of things that are good properties of a pig, and of course such a pig actually existing is better than it not, so "existence" would have to be one of those properties right? So the perfect pig by definition must exist! It's as valid as the ontological argument for God. Kant's critique is that "existence" isn't the type of thing that belongs on a list of properties for anything; it's not a property.

He just phrased that oddly (to the contemporary ear) as "not a predicate" instead. -

Causes of HomelessnessFirst question lacks the reasonable answer: housing is ridiculous overpriced (due largely to rent-seeking activity on the part of the rich). Even average people can barely afford temporary shelter. Most people don’t own their homes, and it’s increasingly difficult for an increasingly large fraction of people to have any hope of ever doing so. By that standard most people are “homeless”, it’s just that most of them manage to barely scrape by to afford temporary (rental) housing better than some others can.

-

What is art?Art is anything presented bu an artist to evoke a reaction in an audience. No qualities of the thing presented or the kind of reaction evoked or the causal origin of the thing matter to qualify it as art: just that it is presented as art.

How successful it is at evoking the intended reaction determines how good the art is. -

Do colors exist?Are there true sentences involving colors as objects of them? If so, then colors exist.

-

Forrester's Paradox / The Paradox of Gentle MurderMurder is a subset of killing, not an alternative.

-

On deferring to the opinions of apparent expertsI didn't create this thread to talk about one specific argument, but more about the general type of question that an argument that I've seen repeated around here keeps bringing to my mind. Namely: if someone who looks (to you) smarter than you in one field says that things in that field have implications contrary to things you feel confident about in another field, what do you do? Question their competence in the first field (even though you're not competent enough in that to directly challenge their claims about it), or question yours in the second?

Also, the particular doubts like that that have come up about the clearest case of that that I've seen here have already been addressed by another apparent expert in the first field who immediately guessed who I had in mind right after I started this thread and assured me that they also find this apparent expert's implications outside their own field dubious. Much as @SophistiCat suggested I seek out the advice of alternate experts. So I'm not especially shaken about that case in particular any more.

In any case, I don't think I would especially like if if someone started a new thread with the topic "I see Pfhorrest keep saying this thing about [x -> y] over and over again on the forum and he seems smarter than me in [x] but he's obviously wrong about [y] and I don't know what to do about that." I dunno, I might like that, depending on how it's phrased, because I love attention, but I'm doubtful enough about whether others would like that that I wouldn't want to start a public thread just about it. I would PM them instead, if I cared that much about that particular topic. Which I don't. But the general question of how to handle questionable conclusions from apparent experts is more interesting, and worth its own thread I think.

That's just refusing to pose an answer to the question. Which is your choice to do, but... it's not really an answer, obviously.

Thank you for your kind reply! To be clear, the incidents that prompted this question in me weren't arguments I was having with other users, but rather claims I see other users make in other arguments with still other people. My self-doubt makes me not dive into those argument, because even though I see conclusions that I think are clearly wrong, I don't feel competent enough to tackle the particular arguments that come to those conclusions, so I would just have to jump in out of nowhere with an unrelated argument to the contrary conclusion, which doesn't seem like a productive thing to do. -

Forrester's Paradox / The Paradox of Gentle MurderWe can always just rephrase it as the Paradox of Gentle Killing and still have the same formal problem to sort out. It actually works out a little better, because it's a pretty common opinion that some killings ought to happen, and that when a killing has to happen, it ought to be done gently. But the formal paradox Forrester raises still suggests that every killing that ever happened ought to have happened.

-

On deferring to the opinions of apparent expertsI don't really want to share a specific example because I don't want to cause drama calling out the main person I've encountered this phenomenon with. I will however say that it is a person who has participated in this thread, so if everyone in this thread (or at least that person, without yet knowing it's them) is cool with it possibly being them, and the thread turning to focus on their opinions and what about them seems obviously wrong on the one hand but above my head on the other hand, then I'll share that.

-

The Road to 2020 - American ElectionsI'll be voting Bernie in the Democratic primaries, but probably whoever wins the Green ticket in the general (living as I do in California; if you live in a "safe" state, vote 3rd party, whether you lean left or right, vote your conscience! If you live in a "swing" state, vote Democrat just to press away from the worst of all options).

I'm sorely tempted to support Yang just because he actually backs a UBI which I think is probably the most important progressive idea seriously raised in American history, but I think the ticket is going to come down to Bernie vs Biden and Biden's a lot worse, so I've got to vote strategically there. Warren would also be an acceptable win, though I'm a little turned off by how nominally "pro-capitalism" she is, but I think she just doesn't understand what the word "capitalism" means and is really just pro-market, anti-command-economy, which, sure, duh, but that's not what capitalism vs socialism is about.

I also think that Bernie has the best chance of beating Trump in the general election, and might actually consider voting Democrat in the general just to send the DNC the message that they didn't fuck up horribly this time and to please do more like that. (The point of voting Green is to tell the DNC "you lost a vote to these guys, be more like them"). -

On deferring to the opinions of apparent expertsAbout Russell: it's math, he is proving math with logic. That is not conceptualizing or conceptualization of philosophical ideas. It is a proof of a highly complex yet only logical system, of math. Failed or not. I don't think the answer to "is there a god" comparable to proving second degree five-unknown sets of differential equations with N degree of freedom.

And to my satisfaction, it was first Russell who answered the "is there a god or not" question. It took two or three easily understood, simple sentences. — god must be atheist

Now suppose that Russell, who you probably trust to be a lot better at you than math, claimed that he could mathematically prove, with math too complex for you to follow, an answer to that "is there a god or not" question, an answer that you're very confident, for other reasons, is the wrong one.

Do you dismiss Russell's incomprehensible argument as obscurantist nonsense, or accept the conclusion of his complex technical argument you're not smart enough to follow just on his word? -

On deferring to the opinions of apparent expertsI have never. Homophobic, yes. Cisgender? It has come to that? — god must be atheist

I'm not sure what you're saying here. "Cisgender" is to "transgender" as "heterosexual" is to "homosexual". What's the problem?

Trans actually does not mean across from; it means "transiting" or "having transited". — god must be atheist

It can mean both:

Across, through, over, beyond, to or on the other side of, outside of. — https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/trans-#English

If it meant "across from" then all women would be transgender males and vice versa. — god must be atheist

The thing that's being crossed or not is the assignment of gender at birth and present gender identity. Someone who identifies on the same side of the gender spectrum that they were assigned to at birth is cisgender, someone who identifies on the other side of it is transgender.

What's PM? — god must be atheist

This following an excerpt from Principia Mathematica (PM): — alcontali -

On deferring to the opinions of apparent experts"Cis" is short for "cisgender", the opposite of "transgender".

"Cis" and "trans" are generally Latin prefixes meaning "on the same side as" and "across from", that can be found in many sciences etc. -

On deferring to the opinions of apparent expertsI intentionally picked two things that seem like a huge mismatch to me, because when I encounter this phenonemon in person the field of the premises and the field of the conclusions seem just as mismatched to me, and I'm not able to follow the supposed connection between them. So if you can't see the connection between these two things, that's great. Pretend someone who you recognize as far more knowledgeable than you about math says that there is such a connection. You can't see how, you can't understand their argument, the inference seems obviously impossible, but they also seem obviously more knowledgeable than you. How do you handle that?

-

Forrester's Paradox / The Paradox of Gentle MurderThe logic as Forrester interprets it means that every murder that was ever done, ought to have been done. That seems like something has gone wrong in that logic somewhere, as I’ve already elaborated upon above.

-

Is increasing agency a valid basis for morality?I don't see why it would be a tautology. As to whether that could be a workable basis for a normative ethical theory, that would depend entirely on how you fleshed out the rest of it. It sounds like it would be very similar to aretaic (virtue ethics) models, in that presumably you wouldn't just want more moral agents but more good moral agents, i.e. more laudable, virtuous people. It also sounds consequentialist in nature, in that you're focusing on the ends, without any regards to means so far. So a lot of critique of both utilitarianism (the premier consequentialist theory) and virtue ethics would probably apply to it.

-

Mathematicist GenesisI think that last bit has some small errors in the explanation of ∀A∀B(∀x(x∈A↔x∈B)↔A=B), and it might be clearer to switch the places of the biimplicants in that anyway, so ∀A∀B(A=B↔∀x(x∈A↔x∈B)). "For all sets A and B, set A is equal to set B when and only when (for all x, x is in A when and only when it is also B)". It's not ∀A∀B(∀x(x∈A↔x∈B)) that is equivalent to A=B, but rather for all A and all B ("∀A∀B"), just ∀x(x∈A↔x∈B) is equivalent to A=B.

-

Radical Skepticism: All propositions are falseIn my philosophy I set out to do something very similar to this. I start out with rejecting two positions that I call fideism and nihilism, the latter of which I take to mean roughly the same thing as saying nothing is true. And the former is something you're probably just taking for granted here: you can't just prove something by assertion. Between the two of those, you get the view that something or another is true, but no claim about what it is can just be taken for true. The result is that everything must be taken as possibly true until we can show that it is false. You can think of this as taking the infinite disjunction of all propositions (A or B or C or D or ...) and then ruling out some of them bit by bit to narrow in on a smaller and smaller disjunction of possibilities. But of course, whittling down an infinite set still leaves you with an infinite set, but you nevertheless "gain knowledge" of what is not the case, even if you will never settle concretely on one specific thing that is the case.

-

Forrester's Paradox / The Paradox of Gentle MurderSomehow I missed your post earlier. You make a good point about my formalization of "you murder gently" as a conjunction of "you murder" and "you are gentle". But your reformalization of it into separate propositions doesn't really change much, no, other than that you can't just logically infer M from MG the way you can infer M from (M ^ G), and instead you would need a separate premise to tell you that MG -> M.

I think it is very helpful if we can formalize it in a way that shows that gentle murder is a subset of murder. Logical conjunction is isomorphic to set intersection, which is why I went with conjunction as the way to show that (the intersection of murder and gentleness is a subset of murder), but if you're familiar with a better way to formalize something like that I'd be interested to learn about it. -

Forrester's Paradox / The Paradox of Gentle MurderThis is a flashback to the empty set being both red and not red (with the blood of the murder victim, presumably.) — god must be atheist

Yeah, I mentioned that upthread, in my second post.

But I don't think "do it gently" means hands down "don't do it ungently", unless there is no murder taking place. — god must be atheist

That is correct. If you were in fact obliged to murder gently, then not murdering would be incompatible with that: you have to murder, and you have to be gentle about it.

That's why I think formalizing the sentence "if you murder, you ought to murder gently" the way Forrester formalizes it doesn't get at what is naturally meant by it. The way he formalizes it -- which, I'll concede, is the superficial reading of the grammatical structure of the sentence -- is equivalent to saying that either there is an obligation to murder gently (and therefore to murder in the first place), or else there is not a fact that you murder; or also equivalently, there is no state of affairs where you commited a murder and were not obliged to do so (and do so gently), so all murders that actually happen were obligatory.

That's why instead I think the intended meaning behind the natural sentence "if you murder, you ought to murder gently" is, in essence, "make sure that any murders that you do are are done gently", or equivalently, "don't do any un-gentle murders". Which can be accomplished by not doing any murders at all. -

How confident should we be about government? An examination of 'checks and balances'Would there be no public property — Wayfarer

Anarchy is all about public property. Anarchy is socialism without the state. -

Forrester's Paradox / The Paradox of Gentle MurderI think the problematic premise is 1, not 3. It is not the case that we ought to murder gently, for it is the case that we ought not murder at all, which precludes murdering gently as well. Instead, it is the case that we ought not murder un-gently, and that is perfectly compatible with it being the case that we ought not murder at all. That's why I would encode the intended meaning of "if you murder, then you ought to murder gently" as "you ought to (if murder then murder gently)" or the logically equivalent and less awkward sounding "you ought to murder gently or not murder at all". That's true, because you ought to not murder at all, but it were the case that you ought to murder, then it would be the case that you ought to murder gently.

-

Science is inherently atheisticDark matter and dark energy are posited because we see weird things happening in the universe and posit those names for the as-yet-unknown whatever it is that's causing them. There aren't any things happening in the universe that we need to posit the existence of God for. "God" is an answer looking for a question; "dark matter" and "dark energy" are placeholder answers to genuine questions.

Also, and this is kind of a pet peeve of mine, but the multiverse stuff talked about by physicists isn't really the same kind that's talked about by philosophers. Physicists are talking about multiple "universes" in a sense that there could be evidence in our "universe" for these other ones, which in a philosophical sense would put our "universe" and the other "universes" in the metaphysically same universe. It's a bit like how "galaxy" and "universe" used to by synonymous, until it was discovered that there were other galaxies. Now it's being hinted at that there might be other things-that-we-have-thus-far-been-calling-the-universe, and we just don't have terminology to differentiate that type of thing from, you know, the universe proper. -

Forrester's Paradox / The Paradox of Gentle MurderYeah, that is a key rule, but I don't think that that is the source of the problem. It's true that if Smith ought to murder Jones gently, that Smith ought to murder Jones.

That's not the only way of encoding the "if you murder, you ought to murder gently" sentence into deontic logic though. It's not even the one Forrester himself uses. Forrester encodes it as "Smith murders Jones" implies "Smith ought to murder Jones gently", which then suggests that in any case that Smith does murder Jones, that is the right thing to do (provided he did so gently). That no murder is ever wrong, so long as it's happens, and it's gentle. If it's not gentle then it's wrong, and if it doesn't happen, then it's wrong. That's the weird thing about Forrester's encoding.

An alternative encoding, which I prefer, is to take the entire conditional "if Smith murders Jones then Smith murders Jones gently" and say that that whole thing is obligatory: it's not that there's an obligation that holds in the case of certain facts, it's that there's a conditional relationship between obligations. It's only if you ought to murder than you ought to murder gently, not just if you do murder.

The usual objection to that solution is that "if P then Q" is logically equivalent to "Q or not P", so obliging "if Smith murders Jones then Smith murders Jones gently" is equivalent to obliging "Smith murders Jones gently or Smith doesn't murder Jones" (which is fine by me so far), and therefore "Smith murders Jones gently" satisfies the obligation: so long as you murder gently, you've still done the right thing.

My retort to that is, as you brought up, the background assumption that you ought to not murder at all. That assumption is the only thing that makes "you ought to murder gently" (and therefore you ought to murder in the first place) sound like an absurd conclusion. But given that assumption, one of the disjuncts of "Smith ought to murder Jones gently or Smith ought to not murder" is ruled out, and the other affirmed: it is not the case that Smith ought to murder Jones gently, because it is not the case that Smith ought to murder Jones, which means it must instead be the case that Smith ought to not murder, which... yeah, he oughtn't. No problem.

To put it another way, "it ought to be that (if you murder then you murder gently)" is also logically equivalent to "it ought to be that (you don't murder un-gently)", which is true if it ought to be that you don't murder at all, which we presume is the case. So there is no problem with this encoding of the sentence in question.

Interestingly enough this circles back around to the same thing at issue in the "Everything, Something, Nothing" thread. If it ought to be that all murders are gentle, that doesn't imply that there ought to be any murders, because "all murders are gentle" is true when there are no murders at all. -

Science is inherently atheisticThe whole circle of science rests inside the circle of philosophy which rests inside the circle of religion — vmarzell

You've got the first part right, but the second part backward. Science is applied philosophy, but philosophy is broader than religion. I would argue that religion properly construed is actually the opposite of philosophy properly construed (what I'd call phobosophy), but given the prevalence of religious philosophers, I'm forced to accede to a broader sense of "philosophy" that can accommodate them.

To the OP though, no, science is not inherently atheistic. It is inherently naturalistic, but there could in principle be a natural god that is amenable to scientific inquiry. Turns out there’s not, but in principle there could be. -

Forrester's Paradox / The Paradox of Gentle MurderYour point about the hidden premise that it’s obligatory to not murder was a key part of my OP.

-

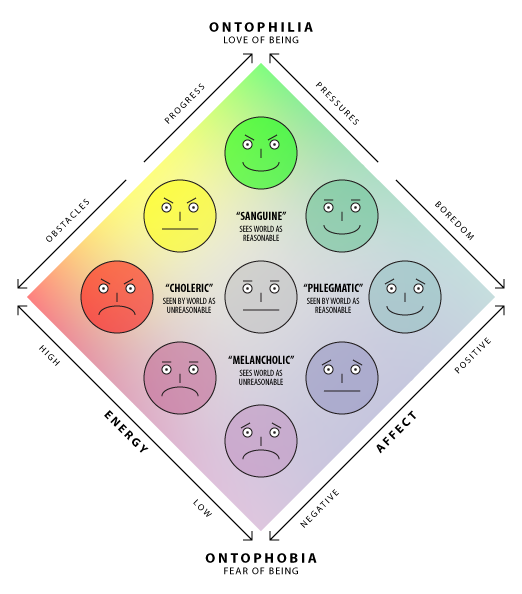

Defining Love [forking from another thread]Something I've long found interesting to contemplate and never come to an adequate resolution on is the relationship of love to fear and hate. I traditionally thought of hate as the opposite of love, such that when I first heard fear juxtaposed as its opposite, back before I studied any philosophy, I thought that sounded really weird. But after studying some philosophy and learning the Greek roots "phobia" and "philia", fear seemed like a natural opposite to love; but so did hate, still. I wondered, does that make hate a kind of fear, or vice versa? Are they maybe opposite love on orthogonal axes?

The conclusion I came to is that fear is a repulsive feeling (pushing away from something that seems bad) in relation to an object that is more powerful than yourself (so repelling it moves you away from it), while hate is the same kind of thing but in relation to an object that is less powerful than yourself (so repelling it moves it away from you).

That made me think that there should be something that bears the same relationship to love. Love is an attractive feeling (pulling toward something that seems good), but in relation to an object that is more powerful than yourself, or less? And either way, what is the other? One thing is wanting to go to someone or something else, the other is wanting to bring that thing or person to you. Are those both "love"? Are there terms to differentiate them? — Pfhorrest

Coincidentally I came across an old note to myself tonight about this very topic, and I think the conclusion I've now come to upon reading my old thoughts is that love and fear are opposite corners of a two-dimensional spectrum of emotions, while hate and tolerance are on the other pair of opposite corners. I already use such a spectrum in my philosophy book (why I'm digging through old notes to myself) in this diagram here:

In the top corner I would put love (and joy), in the bottom fear (and despair), in the left corner hate (and rage), and in the right corner tolerance (and peacefulness). -

Down with the patriarchy and whiteness?What does it mean to act white or black when there is already diversity of actions and needs and wants within those groups themselves? — Harry Hindu

This exactly. When I see black people criticize each other for “acting white”, it looks like they’re being racially prejudiced against their own kind. Any way a black person chooses to act is “acting black”, and criticizing them for not conforming to some stereotype of “blackness” is almost as bad as a white person criticizing another white person for “acting black” because they, I dunno, listen to rap and sag their pants and wear gold chains? I don’t even know what the current stereotype is.

Or like how the movie In And Out determined that its protagonist is gay because he meets a bunch of gay stereotypes, without ever asking if he’s attracted to men. -

4>3What you're describing there is a composite function with the y-value 4 from x-values 1 to 2, and y-value 3 from x-values 3 to 4. In that case it's true that the range of F(x) (which only exists in the domain from 1 to 2) is always greater than the range of G(x) (which only exists in the domain from 3 to 4).

In the first pair of functions, you're describing a composite function with a linear curve of slope 3 from x-values 1 to 30, an undefined curve between 30 and 91, and a linear curve of slope 1 (starting at point 91,91) from x-values 91 and onward. In that case, the range of F(x) is always greater than the range of G(x). But there is no case where a given x is mapped both to F(x) and to G(x) at the same time, so you can't ever conclude that a given value is greater than 3 times that value.

And in any case, you can't compare functions like that, by their domains, or even by their ranges, which only coincidentally (or more likely intentionally by your choice of values) don't overlap in either case here. It's entirely possible that F(x) and G(x) could have non-overlapping domains and overlapping ranges (for example if your first G(x) = 4x instead), in which case it would not always be the case that F(x) > G(x). And they could have overlapping domains, and not intersect, in which case everywhere in the overlapping area would have two y-values mapped to each x-value. -

4>3Since the functions have non-overlapping domains, they are not simultaneous equations, and x can mean different things for each of them.

-

Is the moral choice always the right choice?A person, or someone on their behalf, has a right to protect themselves when they are physically threatened — Tzeentch

That is a moral claim itself. If someone disagrees with that moral claim and tries to stop someone from stopping someone from attacking themselves or others, is it morally okay to stop them from stopping them from stopping them?

You see where this is going? I of course agree completely that people have a right to stop people from harming others, but that is precisely forcing the morals that determine those actions to be "harmful" upon those people being stopped. And of course I agree that murdering someone is harmful to the murdered. But we have that right to stop someone from murdering if and only if murder is actually harmful, which is itself a moral question. So basically, it's right to force the right morals on others, in the right ways, and wrong to force the wrong morals on others, or in the wrong ways. Forcing people to do things that are morally obligatory (like not murdering) is good. Forcing people to do things that are not morally obligatory (like, I'd say, wearing the "right" clothes or listening to the "right" music, or whatever) is bad. Which doesn't tell us much: it just pushes the question back to "what actually is moral or not?" -

Is the moral choice always the right choice?I don't think a decision based on a moral position can really be considered moral when it forces those morals upon people who disagree with it. — Tzeentch

So Alice is about to kill someone when Bob stops her because Bob thinks killings like that are immoral. Bob is therefore immoral, for forcing his morals upon Alice?

In any case in response to the OP, yes, the moral decision is necessarily the right decision. What's at question in your example case is whether open borders really is the correct moral position, or if instead there are counterpoints that suggest it might actually be immoral instead to have open borders. If proponents are just asserting that it is moral, without argument as to why, then they're just asserting that it's the right thing to do, without arguing why it's the right thing to do. Opponents can present reasons why it's the wrong thing to do and then they can argue about who's got better reasons, and whoever does, their position is more moral and the better decision.

Pfhorrest

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum