Comments

-

Ownership - What makes something yours?You said that, but it's not true, and I just gave a counter-example.

There's a public park, an open field where anyone can play. Someone goes out there and starts putting up a fence around it. I don't like that, it's my park too and he has no right to exclude me from it, so I take down his fence. No state involved, just a member of the public defending their own rights.

True, he might then try to fight me over that, but if someone tries to trespass on your private property and you try to exclude them, they might try to fight you over that too. In either case, either the stronger party wins that fight, or some social institution intervenes to settle it.

One way or the other there's a chance that the winning power in that conflict might be wrong about who has what rights and who violated them. There's no difference between the private property and public property in that respect.

(And it's possible the two scenarios described above might in fact be the same scenario: I think that land is public property and he's wrongly excluding people from it, he thinks it's his own private property and people are trespassing on it. Who is right? Dunno, haven't fleshed out this scenario enough. Who gets to decide who is right? Either "nobody" or "whoever has the most power", depending on whether "gets to" is prescriptive or descriptive). -

Ownership - What makes something yours?Similarly, a left-libertarian would say that defending their access to public property is a natural right, and if one party for instance tries to enclose a commons that everyone had been using, everyone else has a natural right to break down their fences or whatever is necessary to continue their equal free use of it. Or if someone were to try to destroy a public resource, others would have a natural right to stop them from doing so. Etc.

-

How would past/contemporary philosophers fare in an internet philosophy forum (like this one)Instead of writing a book and letting others defend it THEY would have to defend all points themselves from any direction from any angle. — schopenhauer1

You know that the peer review process of publishing is exactly the author of a paper having to defend it against criticism from other people, right? It is a limited board of highly-educated other people (hence "peers"), not the general public, but still it's not a matter of just writing something and then walking away and letting others defend it for you. You have to defend it yourself, to at least the gatekeepers of the journal you want to publish in, otherwise you don't get published. -

Ownership - What makes something yours?By that measure it sounds like "public ownership" is in fact state ownership, because some state or other would be required to determine and enforce what one could or couldn't do with this property. — NOS4A2

Private property generally requires government enforcement as well (governments are not necessarily states, NB), unless you want to go back to what Maw was saying that your own power to defend something is all that makes it yours. -

How would past/contemporary philosophers fare in an internet philosophy forum (like this one)When studying philosophy in college, it was emphasized that reading, writing, lecture, and discussion all serve their own distinct purposes for honing one's philosophical skills. The dichotomy you are talking about here sounds like that between writing and discussion, where writing lets you structure and compose your thoughts in slow, methodical detail, but discussion requires you to think on your toes and be quick and concise. The two reinforce each other: having written about something prepares you better to discuss it, and having discussed something prepares you better for writing about it. Ancient philosophers didn't have internet forums, but they had the meatspace equivalent of them in philosophy discussion groups.

Lecture and reading are likewise complementary. Lecture gives you breadth, and offers immediate if non-comprehensive feedback when you have questions without having to go digging for answers yourself. Reading on the other hand gives you depth on a narrower subject, but without the interactivity of a lecture, making it harder to figure something out if you don't just understand it right away.

That's why philosophy classes are often structured such that you read some passages from primary sources in advance of a lecture about that topic, then write about the topic in advance of a discussion group about it. Reading, lecture, writing, discussion, 'round and 'round, filling out your breadth and depth of philosophical knowledge and establishing a well-grounded but agile footing for your own philosophical thought.

(In martial arts there is also a similar emphasis on the complementary practices of slow and fast workouts, practicing the same techniques slowly so that you ingrain all the fine details of the movement better into muscle memory, and then practicing them as fast as possible so that you can actually use them quickly when the time comes that you need to). -

Ownership - What makes something yours?To own property is to have rights in it. For something to be private property is for someone to have those rights exclusively. For something to be private property, everyone has those same rights, inclusively. How does that work? Same way jointly owned private property does, just with more owners. If a husband and wife own a house together, they each have claims against the other regarding the house (one can't unilaterally start demolishing it, for instance) and liberties regarding it (either is free to stand in the living room, for instance). For public property, everyone has those same kinds of rights regarding the thing and each other.

-

Ownership - What makes something yours?I have never said that "might makes right". Might does not make one right. — Harry Hindu

Okay, then I think this whole conversation has been mislead somehow, because everything I've been asking is trying to reconcile something you said earlier that suggested that you think might makes right, which you then immediately contradicted in the same post. I've been trying to suss out how you reconcile that contradiction. It was this post:

Power — Maw

Power to defend what you've acquired. A limited government is necessary to ensure that you acquired it legally - meaning: without infringing on the rights of others. — Harry Hindu

That sounds like you're agreeing with Maw that ownership consists in having power to defend what you've acquired: that might (power to defend) makes right (legitimate ownership). But then you immediately say that a government is necessary to make sure you don't acquire things that aren't yours. But if having power to defend is all that makes it yours, then your act of acquiring it from someone else would mean they failed to defend it and so it wasn't theirs anymore. And if the state is the one doing all the defending, and defending it makes it yours, then either everything belongs to the state, or at best anything belongs to whoever the state acts like it belongs to. Which seems like a conclusion you would disagree with, but that's the consequence of what you seemed to be saying, so you seemed to be contradicting yourself.

If you're not saying that power to defend what you've acquired is all that makes something yours, then that resolves the contradiction. I've just been trying to get you to either say that, or say that you accept the consequences of that, to tell which side of this apparent contradiction you really fall on. -

Metaphilosophy: Just how does one do Philosophy?I started another thread earlier this month with a bunch of metaphilosophical questions, and I can quote some of the answers people gave for you here:

The Meaning of Philosophy

What defines philosophy and demarcates it from other fields? — Pfhorrest

1.1 Philosophy, as I understand it, consists in contemplating, critically exposing, and even shaming foolery (i.e. failing to learn from failure, due to 'answering' pseudo/irrelevant questions or 'solving' pseudo/irrelevant problems, because one doesn't know that one doesn't know what one needs to know in order to adaptively judge one's circumstances, which in the long(er) term tends to adversely affect either oneself or others).

1.11 Nonphilosophical fields (e.g. sciences, arts, politics), on the other hand, tend to be invested in applying domain-specific answers and solutions and not in reflecting on how or why questions and problems are framed (i.e. paradigmatic assumptions for posing questions and pragmatic implications from working out problems) and whether or not they are relevant questions to be asked or fecund problems to be tasked. Domain-specific fields tend to be specialized, or instrumental, to the point of being blind to foolery (which also includes normative misuses, or maladaptive practice, of domain-specific knowledge & techniques).

1.12 Philosophy critiques ignorance - illusions of knowledge - which persist due to (indoctrinated? ideological? expedient?) ignorance of ignorance, or what I mean by "foolery" "folly" "unwisdom" ...

1.13 Nonphilosophies, however, produce knowledge, techniques & applied practices in ways, more often than not, oblivious to the foolery with which these productions are (usually) framed.

The Objects of Philosophy

What is philosophy aiming for, by what criteria would we judge success or at least progress in philosophical endeavors? — Pfhorrest

1.2 Philosophy's horizon, at which it's always been aimed, is wisdom - habits of 'thinking well' (free mind) and 'living well' (free body) acquired through reflective inquiries & reflective practices. (By reflective I mean 'self-examining'.)

1.21 The criterion is internal to thinking & living since philosophizing - the exercise itself - is its product, unlike e.g. chemistry which produces new & improved formulas or industrial materials; or painting which produces new expressive styles & artworks; or politics which produces new movements & social arrangements. To the degree, at any moment, a philosophical discursive practice has filtered-out pseudo-questions & pseudo-problems as well as marginalized the irrelevant/trivial, this counts as "progress" of an evanescent kind, achieving topic-specific clarity.

The Method of Philosophy

How is philosophy to be done? — Pfhorrest

1.3 In Marx's or Dewey's sense of praxis:

1.31 (a) Reflective inquiry into concepts used in, or to construct, e.g. scientific, technical, artistic & political theories.

1.311 Taxonomy of questions: definitions for filtering out irrelevant, trivial & pseudo-questions.

1.32 (z) Reflective practice of applying e.g. sciences, technologies, arts & politics in ways useful to persons & communities for surviving and flourishing despite social conflicts, martial catastrophes or natural disasters.

1.321 Taxonomy of problems: (See 2.51, 2.511, 2.512, 2.513, 2.52)

The Subjects of Philosophy

What are the faculties that enable someone to do philosophy, to be a philosopher? — Pfhorrest

1.4 Courage. Sapere aude. Amor fati. Solitaire et solidaire. No doubt intellectual courage is needed, but only moral courage suffices for philosophizing with 'skin in the game' (i.e. fat's in the fire), or like Freddy says "with a hammer", and not just to sound out "hollow idols" but to build anew in (or bricole with) the rubble our hammering makes of (the last) old prisons. Otherwise, without courage, philosophers amount to little more than idly vacuous, tenured twats - either p0m0 scholastics of "wokeness" or think-tank rationalizers of the status quo ante.

The Institutes of Philosophy

Who is to do philosophy and how should they relate to each other and others, socially speaking? — Pfhorrest

1.5 Dead philosophers (via primary sources whenever possible and/or excellent translations): they alone "do philosophy". We living fools merely need to relate to - philosophize with - each other like children at play in the world's minefields precociously engaged in the most tragicomic of dialectics.

The Importance of Philosophy

Why do philosophy in the first place, what does it matter? — Pfhorrest

1.6 The same reason an alcoholic or drug addict goes to rehab and learns how to soberly live a 'life of recovery', I philosophize in order to rehab my own foolery and live as lucidly as a recovering fool can live, as they say, one day at a time — 180 Proof

The Meaning of Philosophy

What defines philosophy and demarcates it from other fields? — Pfhorrest

General truths, reflections on the human condition and the existential quandaries specific to human beings. I see the Platonic corpus, in particular, The Republic, and The Apology as being foundational to philosophy and indeed to Western culture proper.

Of course it is true that philosophy quite rapidly became desultory, wandering across topics, questions and subjects. But there is a constant undercurrent of questions, or a characteristic attitude, which animates it.

Pierre Hadot:: 'The goal of the ancient philosophies was to cultivate a specific, constant attitude toward existence, by way of the rational comprehension of the nature of humanity and its place in the cosmos. This cultivation required, specifically, that students learn to combat their passions and the illusory evaluative beliefs instilled by their passions, habits, and upbringing. 1'

I find that a satisfactory definition. This definition is also quite agreeable from a Buddhist perspective.

What differentiates philosophy is its general nature. It is not concerned with techne or with politics as such, but first principles and ultimate ends.

The Objects of Philosophy

What is philosophy aiming for, by what criteria would we judge success or at least progress in philosophical endeavors? — Pfhorrest

The difficulty in this question is that modern culture and society has no ready equivalent for the kind of intellectual illumination which classical philosophy sought. Nowadays progress is nearly always judged in economic, technical or scientific terms - this is what has been criticized as the 'instrumentalisation of reason'. I suppose one attempt to answer the aim of philosophy in contemporary literature would be something like Eric Fromm's Man for Himself:

'In Man for Himself, Erich Fromm examines the confusion of modern women and men who, because they lack faith in any principle by which life ought to be guided, become the helpless prey of forces both within and without. From the broad, interdisciplinary perspective that marks Fromm's distinguished oeuvre, he shows that psychology cannot divorce itself from the problems of philosophy and ethics, and that human nature cannot be understood without understanding the values and moral conflicts that confront us all'.

Note that this is a psychology text, but I think there's an unbreakable connection between philosophy, psychology (in the broad sense understood by Fromm's) and cultural anthropology.

So the objects of philosophy need to be holistic, to provide an ethical compass, and to be rational in the sense of addressing all human needs, and not just those envisaged by materialist philosophy which invariably reduces mankind to a means rather than an end (i.e. a means by which the evolution executes its basically meaningless algorithm.)

The Method of Philosophy

How is philosophy to be done? — Pfhorrest

The first and practically only rule is: know thyself. Anyone can say it, very few advance in it, hardly anyone masters it. — Wayfarer

The Subjects of Philosophy

What are the faculties that enable someone to do philosophy, to be a philosopher? — Pfhorrest

I think, independence, intuition, reason, compassion, and a degree of innate intelligence.

The Institutes of Philosophy

Who is to do philosophy and how should they relate to each other and others, socially speaking? — Pfhorrest

First and foremost, those drawn to it, and also who have received some form of endorsement from those already practicing. That would include, for example, lecturers and teachers in the subject.

The Importance of Philosophy

Why do philosophy in the first place, what does it matter? — Pfhorrest

Again, it's the contemplation of 'what really matters'. There's any number of subjects, a practically uncountable number of facts to be discovered. But we are born human, we live our three score years and ten (hopefully), and then we die. Philosophers wonder about the meaning of that. I'm a believer in the principle that 'philosophy requires no apparatus'. Certainly today's technology and science can provide innumerable benefits and I never want to be thought of as being against them, for what they can do. But they can't solve the deepest questions of human life, as only humans can do that, in human form. (But, for example, medical science can help countless people to be physically cured to enable them to live to explore such questions which in times past wasn't possible. But I'm highly sceptical of trans-humanism or VR.) But philosophically, I think humans are in some basic sense the form that the Universe takes to discover itself or to fully realise its own reality. 'A physicist', said Bohr, 'is just an atom's way of looking at itself'; one of Bohr's apparently tongue-in-cheek remarks, but containing a profound insight. I regard many religious myths and metaphors as ways of expressing this idea, although unfortunately the meaning is often forgotten while the outward forms are clung to.

So I suppose one contemporary expression of that is Maslow's idea of 'self-actualisation', although it finds expression in many forms of the idea of 'self-realisation'. That is often associated with Indian spirituality, about which I will have more to say later. — Wayfarer

The Importance of Philosophy

Why do philosophy in the first place, what does it matter? — Pfhorrest

The philosophy that is most important is the effort we make to situate ourselves in the world, and judge whether where we are is good or not. some people do not think about these questions, because their questions have been answered by their other-worldly or their temporal ruler, or because they prefer not to think about such matters. Somebody has to get out and till the corn so that there will be food on the table. Be grateful that the corn was hoed.

Somebody has been thinking about these questions beginning perhaps 300,000 years ago. There is no accumulation of insight, because each person in each generation who asks these questions must find his or her own answers.

Now in the 21st Century, we are still asking these kinds of questions. Perhaps we are able to use more sophisticated language (or not) but the need to situate ourselves in our time and place is no less or more important. The answer does not usually come to us swiftly. We can spend decades rolling the question around in our heads without much result. — Bitter Crank

The Meaning of Philosophy

What defines philosophy and demarcates it from other fields? — Pfhorrest

Philosophy is the thing outside or on existing borders of "usefull" categories/views.

The Objects of Philosophy

What is philosophy aiming for, by what criteria would we judge success or at least progress in philosophical endeavors? — Pfhorrest

Philosophy tries to enable the expaning of borders or creating of new categories. This is mainly done by clarifing unclear concepts by creating models that aproximate roughly what is being talked about.

The Method of Philosophy

How is philosophy to be done? — Pfhorrest

Creative thinking that consists of a sufficient degree of critical thinking and rigor.

The Subjects of Philosophy

What are the faculties that enable someone to do philosophy, to be a philosopher? — Pfhorrest

Whatever faculties enable the creative and critical thinking. Further one could add containing a certain productive element that consists either of theory builiding or precise and usefull criticism.

The Institutes of Philosophy

Who is to do philosophy and how should they relate to each other and others, socially speaking? — Pfhorrest

Whoever wishs to do so. I don't think it's reasonable to suggest a specific way of relating to others. In general one might constrain it artificially by limiting based on max number due to philosophers being not short term productive for society and thus demanding a certain wealth of a society. However I think this is done rather automatically.

The Importance of Philosophy

Why do philosophy in the first place, what does it matter? — Pfhorrest

It improves the long term development of civilizations. Like science it does not produce instant results and instead shifts the results to the future. One can imagine it this way we need food now/being active harvesting ect but improve overall foodproduction by allowing one member to be passive and think about food harvesting. — CaZaNOx

I’ll give ‘em a quick go ...

Meaning? Dunno. I guess it is more or less about dealing with items that evade demarcation and/or measurement in any accurate sense.

Objects? Dunno. I guess it’s more or less about opening up new/old perspectives and seeing what can be done with them separately and/or in combination.

Subjects? Dunno. I guess, very generally speaking, cognition of space and time (Kantian intuitions).

Institutes? Dunno. Doesn’t matter. People will or won’t do it regardless of my ideas of should, would or could as the most obtuse individuals will call anything ‘philosophy’ just as they’d call everything ‘art’. I guess this means the geniuses, idiots and insane are usually the primary movers - for good or bad!

Importance? I guess it’s importance comes into play by exploring questions - meaning how questions are useful and what their limitations are or are not.

Note: I’m not entirely sure what ‘metaphilosophy’ means in modern parse? — I like sushi

The Meaning of Philosophy

What defines philosophy and demarcates it from other fields? — Pfhorrest

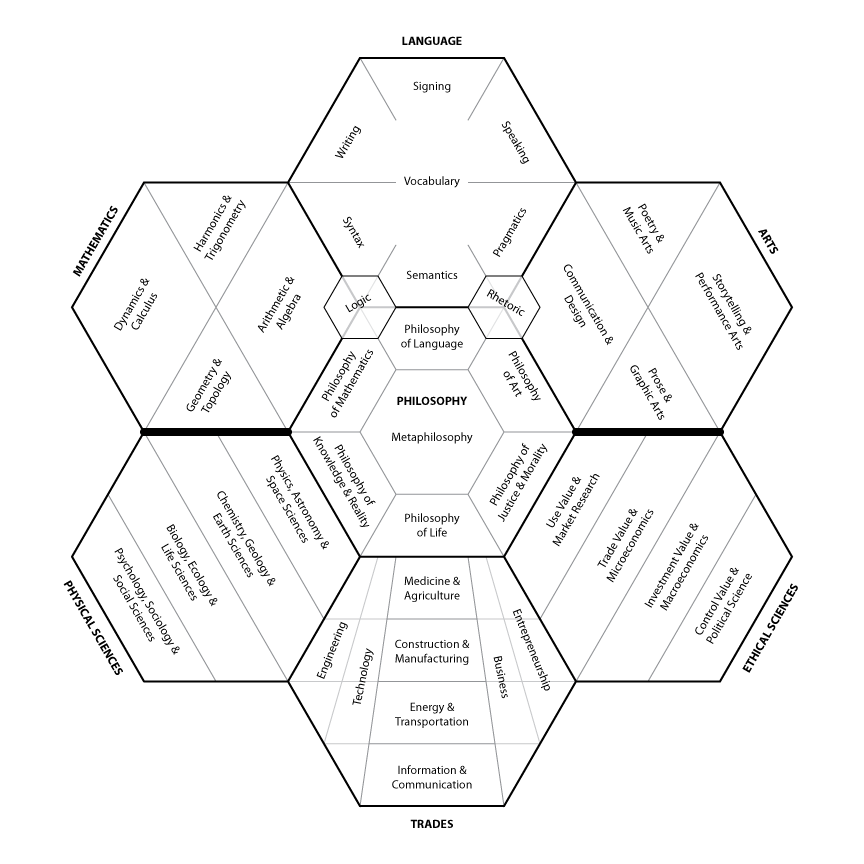

Philosophy is the seeking of wisdom - not simply knowledge, or even an understanding of the world. As such it permeates every field. To demarcate the seeking of wisdom from any field of endeavour is to claim that there is no wisdom to be found in that field. I think you showed this with your diagram.

Knowledge is an awareness of information; Understanding is the connection we make with the information we have about the world; and Wisdom is how we collaborate with that information. Wisdom ties in with knowledge and understanding in such a way that all three are inseparable. You can’t really understand something, even if you think you know as much as you can about it, until you can apply that knowledge in how you interact with the world. In the same way wisdom isn’t really wisdom if we ignore information or cannot (or will not) strive to understand all the information available to us.

Philosophy values all information, regardless of its current usefulness, and seeks to make effective use of all that we know and understand about the world - paying particular attention to what we don’t yet know, what we know but fail to understand, and what we know and understand but fail to integrate or apply to our interactions with the world. — Possibility

The Objects of Philosophy

What is philosophy aiming for, by what criteria would we judge success or at least progress in philosophical endeavors? — Pfhorrest

Philosophy aims to structure and restructure our conceptual models of the world, to make the most effective use of all the information we have. Progress in philosophical endeavour, then, is achieved when we can account for anomalous data or experiences, when we can include and collaborate with alternative viewpoints, and when we can revive and integrate suppressed or forgotten knowledge into how we interact with the world.

Successful philosophical endeavour aims to integrate useful information from disparate sources for application to living well - ie. interacting with the world with less prediction error.

The Method of Philosophy

How is philosophy to be done? — Pfhorrest

All information is potentially useful, so the first step would be to reserve judgement on information in an objective sense.

We are, however, each progressively limited in our capacity to be aware, connect and collaborate with information by the five dimensions of our existence, and so we cannot always make use of information ourselves. We are equipped, all the same, with the means to share that information with those for whom it may prove much more useful.

Philosophy may sometimes involve, therefore, extracting incomplete information as raw experience from what has been integrated and reduced to suit these individual or cultural limitations any number of times. This may involve grafting the information onto our own experiences or other experiential accounts, or borrowing structural patterns as a guide to completing the experiential information. This type of speculative philosophy is fraught with error, but relying only on reducible information encourages us to be dismissive of the additional aspects available in information from subjective experience. Keeping track of where and how we depend on assumptions, concepts and modelling can be more important than avoiding them altogether. — Possibility

The Subjects of Philosophy

What are the faculties that enable someone to do philosophy, to be a philosopher? — Pfhorrest

Short version, I think self reflection and self evaluation are the key faculties for doing philosophy. The capacity to be aware of our conceptual systems, and be critical of the specific way that we interact with the world in relation to how the universe interacts with each other in its diversity, provides the potential for us to strive towards more accurate conceptual systems that minimise prediction error while maximising interaction.

I think an effective philosopher has a handle on critical and creative thinking, and employs an inclusive approach to knowledge. Courage, respect and curiosity also enable one to do philosophy without limitations.

The Institutes of Philosophy

Who is to do philosophy and how should they relate to each other and others, socially speaking? — Pfhorrest

A closed mind cannot do philosophy. If you take the trouble to avoid making mistakes, then perhaps philosophy isn’t for you. History shows that philosophers can’t really avoid being mistaken about something. The best we can hope for is the rare gem of conceptual structure that leads us to new ways of thinking.

The mind isn’t structured temporally or spatially, but according to value. Reality, however, is ultimately structured according to meaning. So when we relate to each other, socially speaking, it should be with a focus on a shared value regardless of distance, space or time. But when we relate to what others experience, particularly the form in which they present it to us, it should be with a focus on reaching a shared sense of meaning regardless of value.

The Importance of Philosophy

Why do philosophy in the first place, what does it matter? — Pfhorrest

When we interact with the world, we encounter new information. We either use that information in subsequent interactions with the world, or we don’t. If we do, then the way that we use it, our philosophy, matters. But it is also the information that we don’t use, and why - the value and significance we attribute to information - that structures this philosophy.

Evolutionary theory says that the most important thing we pass on to our descendants is our genetic information, but I disagree with this. The way I see it, the most important thing we pass on is the capacity to make effective use of new information. Without it, we’re not really living, are we? — Possibility

The Meaning of Philosophy

What defines philosophy and demarcates it from other fields? — Pfhorrest

Philosophy is the love of wisdom, where by "love of" I mean attraction toward, or pursuit of; and by "wisdom" I mean the ability to discern truth from falsehood and good from bad, or at least the ability to discern superior from inferior answers to questions about either reality or morality. It differs from the sciences in that it is not concerned with contingent, a posteriori facets of the experiential world, but more about how to process and react to those, the necessari, a priori, foundational questions about how to do those sciences; those sciences apply wisdom thus defined, and philosophy is the pursuit of that ability to do so. It also differs from more abstract fields like the arts and mathematics in that is is not entirely disconnected from practical applications and concerned just with structure for structure's sake (like math) or presentation for presentation's sake (like the arts), but rather uses those things, like logic and rhetoric, as tools to do its job of facilitating the sciences, both the well-known physical sciences and what I would call the ethical sciences, that I may elaborate on later. It's the glue between the abstract and the practical.

And lastly I'd argue that, properly speaking, it differs from religion in that it is critical, anti-fideistic, taking nothing as unquestionable. But it's also properly speaking anti-nihilistic, allowing free investigation of things with uncertain grounding rather than shutting all such discourse down as groundless and impossible from the outset. I would argue that both fideism and nihilism are rather "phobosophy", the fear of wisdom. But I recognize of course that fideistic and nihilistic elements are often included in what are commonly considered philosophical endeavors; I just argue that, to that extent, those endeavors are failing to really do philosophy per se. — Pfhorrest

The Objects of Philosophy

What is philosophy aiming for, by what criteria would we judge success or at least progress in philosophical endeavors? — Pfhorrest

Philosophy aims for wisdom, in other words to discover or create a means of discerning truth from falsehood and good from bad, and it progresses in that endeavor by clarifying confused concepts about those scales of evaluation. The emergence of, loosely speaking, "the scientific method" is the greatest bit of philosophical progress in the history of the field, in my view, and though progress in moral investigations has been much slower, we're still slowly crawling there with increased emphasis on liberty, democracy, and material well-being, and less on things like ritual purity and obedience. — Pfhorrest

The Method of Philosophy

How is philosophy to be done? — Pfhorrest

Philosophy is done not so much by solving problems, but by dissolving them: showing apparent paradoxes and dilemmas that would seem to stand in the way of any route toward wisdom to actually be the result of confused thinking, conflated terms or ideas, etc. By teasing apart that confusion, differentiating conflated terms and ideas from each other, and so on, philosophy can progress toward wisdom by showing those apparent roadblocks to have actually been illusory all along. More generally, philosophy makes headway best when it analyzes concepts in light of the practical use we want to put them to, asking why do we need to know the answer to some question, in order to get at what we really want from an answer to that question, and so what an answer to it should look like, and how to go about identifying one.

In analyzing concepts and teasing them apart from each other, philosophy makes extensive use of the tools of mathematical logic. But in exhorting its audience to care to use one of those teased-apart concepts for some practical purpose, instead of endlessly seeking answers to the uselessly confused and so perpetually unanswerable question that they may be irrationally attached to as some kind of important cosmic enigma, philosophy must instead use the tools of the rhetorical arts. Thus philosophy uses the tools of the abstract disciplines, mathematics and the arts, to make progress in its job of enabling the more practical sciences to in turn do their jobs of expounding on the details of what is real and moral. — Pfhorrest

The Institutes of Philosophy

Who is to do philosophy and how should they relate to each other and others, socially speaking? — Pfhorrest

The question is largely whether philosophy is a personal activity, or an institutional one. Given that I have just opined that the faculty needed to conduct philosophy is literally personhood itself, it should come as no surprise that I think that philosophy is for each and every person to do, to the best of their ability to do so. Nevertheless, institutions are made of people, and I do value the cooperation and collaboration that has arisen within philosophy in the contemporary era, so I don't mean at all to besmirch professional philosophy and the specialization that has come with it. I merely don't think that the specialized, professional philosophers warrant a monopoly on the discipline. It is good that there be people whose job it is to know philosophy better than laypeople, and that some of those people specialize even more deeply in particular subfields of philosophy. But it is important that laypeople continue to philosophize as well, and that the discourse of philosophy as a whole be continuous between those laypeople and the professionals, without a sharp divide into mutually exclusive castes of professional philosophers and non-philosophers. And it is also important that some philosophers keep abreast of the progress in all of those specialties and continue to integrate their findings together into more generalized philosophical systems.

(I feel like I weirdly straddle all those divides, having some degree of professional education in the field but not nearly deep enough to teach it professionally, and working on a generalized philosophical system that draws from the more contemporary findings of all those specialties).

The Importance of Philosophy

Why do philosophy in the first place, what does it matter? — Pfhorrest

On the one hand, doing philosophy is literally practice at being a person, exercising the very faculty that differentiates persons from non-persons. Doing philosophy literally helps develop you into a better person, increasing your self-awareness and self-control, improving your mind and your will, and helping you to find meaning in the world, both in the sense of descriptive understanding, and in the sense of prescriptive purpose.

But also, as I already elaborated upthread, I think philosophy is sort of the lynch pin of all human endeavors. All the many trades involve using some tool to do some job. Technology administers those tools, business administers those jobs; engineers make new tools, entrepreneurs make new jobs; the physical sciences find more "natural tools" for the engineers to work with, and the ethical sciences I propose would find more "natural jobs" (i.e. needs that people have) for the entrepreneurs to work toward. Both those physical and ethical sciences depend on philosophy for the tools they need to do their jobs. Philosophy in turn relies on the tools of language, mathematics, and the arts to do its job, and then reflexively also examines those topics, as well as itself.

I drew a picture: — Pfhorrest

That last picture is also from my essay on the subject from my philosophy book in progress. -

What are your favorite video games?The Marathon trilogy by Bungie (whence my name), which is now free to play BTW. Story discussion about this was actually an early introduction to some philosophical thinking for me (especially the third game, which many people find confusing), and my unofficial sequel to it (Eternal), which is about twice as long as the original game, has been described as very "philosophical", though I didn't set out to make it a philosophy tract or anything.

Also their Myth series. -

Licensing reproductionI am against all licensing.

I don't admire the gall of drunk drivers or anyone else engaging in activities that put others at risk, but I think that they should be punished in proportion to the harm they cause -- as all punishment should be -- and so the deterrent effect of punishment will automatically be in proportion to how much their actions risk how much harm. Asking for permission in advance or not shouldn't play a part in how much they're punished.

But even within the realm of licensed activities, licensing reproduction seems even worse than the rest, precisely because the practical effect of it is going to be punishing someone for something, and what exactly do you propose the punishment be for what act? Are you going to punish people for having unprotected sex? How are you going to find out if that's happening? That's going to require an enormous invasion of privacy to be effectual at all. Do you only punish them if they actually conceive a child? What if they accidentally conceive, after taking all due precautions? (Birth control sometimes fails). In any case, do you force an abortion on them? That raises a huge ball of problems comparable to banning abortions. Even if you don't, then what? Do you take the children away from them? Children raised in institutional environments generally fare worse than even the averagely-badly-parented child, so that seems contrary to the intended purpose of protecting the children. Do you let the parents keep the children, and just jail one or both of them? Both seems obviously problematic, leaving the children in institutional care again, and even if it's only one, children of single parents, especially those with jailed co-parents, generally fare worse than otherwise, again defeating the purpose. Do you just fine the parents, but leave them free and let them keep the kid? That just leaves you with poorer parents, which again negatively affects the rearing of the children, defeating the purpose.

I do think people should be responsible in their procreation, just like they should be responsible in their driving, but trying to enforce that with punishment (besides the given of punishing people for the direct harm they cause) is not only morally wrong, but in this case seems like it would just cause way way more problems than it could possibly solve. -

Licensing reproductionThe only effect licensing anything has, compared to just punishing harm when it happens, is to punish people who did something harmlessly without first asking for permission. People who do ask permission first (get licensed) still get punished if they do harm and don’t get punished if they do no harm, and people who don’t ask for permission first (do it without a license) and cause harm would still have been punished for that harm even if we hadn’t required licensure. So the only people who receive any different treatment when licensing is required are people doing no harm, just acting freely, who get punished for having the gall to do so. Which makes licensure of any kind the antithesis of freedom.

-

Ownership - What makes something yours?So you are rejecting the might-makes-right principle that ownership = power? This subthread is challenging Harry about his acceptance of that.

(Also, note the last paragraph of the post you responded to, it might not be Alice's legitimately acquired property after all). -

Ownership - What makes something yours?The state is going to want something in return, and the state isnt going to do something that would cause its members to lose faith in the fairness of the system. How are you going to convince others that what I worked hard for is yours and how will that be consistent with how the state makes others decisions in regards to ownership? I think you're just making up unrealistic scenarios with taking into consideration the implications of your thought experiments. — Harry Hindu

The point of thought experiments it to tease out what you're really saying or thinking. Regardless of whether or not something would happen, I want to know what you think in the hypothetical circumstance where it does.

I'm trying specifically to avoid concrete real-world issues, but if you really want something like that, here's an easy scenario: the public, losing faith in the way the system works now, decides that it's not fair that there are more unoccupied homes than there are homeless people, and so ownership of those homes should be assigned to the homeless people. So the state, directed by the majority, who elect people to represent that view for them, stops keeping homeless people out of unoccupied homes, and instead keeps those homes previously-assigned "owners" from kicking the homeless people out. The state just starts acting like the homes rightly belong to the newly-assigned owners.

In your view of might makes right, does that then make those homes legitimately the property of the newly-assigned owners, and no theft have happened?

Or on a larger picture: if a state-socialist regime comes into power in a state and does start taking things from people and giving them to other people, on what grounds would you say (or wouldn't you say?) that that was wrong? So far, all you've said to similar questions is "that wouldn't happen". But this has happened, and I gather that you think that it was bad. Why is it bad, if might makes right, i.e. power is ownership? -

Ownership - What makes something yours?If your defense makes it not worth trying to take what you have from you, then you own it by default. — Harry Hindu

So if I can convince the state to help me keep you out of the house you live in, and keep anyone else besides me from living there, then it's my house, totally legit? (Or, if the state doing it is somehow wrong: if they just don't stop me from driving you out of the house myself?)

I'm pretty sure you'll say no, of course not, because it's your house and that would be stealing. But why is it your house if you can't defend your possession of it from the state (or from me)? Why is it wrong for the state (or me) to dispossess you of it, if your ability to maintain possession of it were all that made it yours, so your failure to do so would make it not yours anymore?

Should the state defend your possession of it because it's yours, or is it yours because the state defends your possession of it? -

Hard problem of consciousness is hard because...The point of my comment was less to argue for panpsychism, and more to make a point about the definition of 'consciousness'. The differences in experience between one thing and another are differences in what is experienced, not differences in degree of consciousness, because consciousness does not admit of degree. — bert1

I agree, and I think that this is analogous to the situation with incompatibilist free will. Incompatibilists insist that free will means being undetermined. Okay, electrons are undetermined, according to contemporary physics. So electrons have free will? Sounds like kind of a useless definition of free will then. But hey look over there, those compatibilists have a much more useful definition of free will according to which humans sometimes have it but electrons don't... it just has nothing to do with (in)determinism.

Likewise, phenomenal consciousness and access consciousness. -

Ownership - What makes something yours?Who owns them, or who has them? Maybe someone forgot to lock the door. Maybe someone else picked the lock. Picking a lock isn't always wrong, such as if you lost your keys, or they were pick-pocketed off of you, or if someone else changed the locks on your house while you were out. Or maybe Alice was just at home with the doors unlocked for whatever reason, and then Bob walked in and started acting like it's his home.

There's lot of ways you could flesh out this scenario (read the entire post please, I listed a bunch in the last paragraph). The important question for you is, what if any difference do those different circumstances make? -

Ownership - What makes something yours?If you never owned it, then how does it even make sense to say that someone is taking it by force? — Harry Hindu

There is some house that Alice is living in. Bob walks into it and starts living there too. Alice says "no, get out, this is my house". Bob doesn't obey her commands -- he doesn't use any violence against her, he just continues hanging out living in the house that Alice says is hers. Alice wants to force Bob out of that house -- or preferably, have the state come and force Bob out of the house for her, using violence if necessary. Bob is getting tired of this disturbance in the place he lives and would like the state to remove Alice instead, or maybe he'd like to remove her himself if they won't, though he hasn't tried that yet, nor has she tried to remove him by force yet. They're both just asking the state to make the other leave, so as to defend their exclusive right (they each claim) to this piece of property.

Under what circumstances should the state decide in Alice's favor or Bob's favor? What makes the house really Alice's or really Bob's? Is it just whoever the state happens to decide to favor? Or are there independent reasons that the state should consider in deciding whose rights are legitimate and deserve defending? If the latter, are those reasons simply "whoever succeeds at forcing the other out themselves gets to stay"? If not that (or the "whoever the state decides for whatever reason to force out" answer), then the "whoever can defend it owns it" principle is not being adhered to, but instead something else determines ownership, and the state just enforces (or ought to enforce) those independent rights.

Should the state defend your possession of something because it's yours, or is it yours because the state defends your possession of it?

(Consider all the possible circumstances that could lie behind Alice and Bob's conundrum. Did Bob used to live there before Alice? How long ago? Is this Bob's vacation home and Alice is squatting in it when Bob arrives for his vacation? Or is this Alice's family home since childhood and Bob is some vagrant who wandered in off the street? Does Bob usually live there, and just went to work this morning, and came home to find Alice had moved in while he was away? Did Alice just buy this place from someone who claimed to be the owner, and now Bob shows up acting like it's actually his? Do any of these things matter or not, and if so why?) -

What’s your philosophy?Bonus question: How do we get people to care about education and knowledge and reality to begin with? — Pfhorrest

I call this task, the inspiration of the mind to actively pursue the truth, the real, the knowable, or the state of the mind being (or the process it of becoming) fully conscious or self-aware, "enlightenment". We cannot enlighten someone just by telling them facts. We cannot simply tell them to operate their mind some way either. We must somehow inspire them to exercise their mind, show them opportunity and motive to think for themselves of their own accord. To do that we must show them that achieving truth is actually possible, and thus that there is hope for them if they try to do so themselves. But we must conversely be sparing in our direct help, lest they come to rely upon us, take our help for granted, and deem it unnecessary for them to try to learn themselves. Instead, we need to help people to help themselves, to require that they take initiative in trying to pursue their own truth, but to stand by and hold their hand while they get a bearing for it, to ensure that their early attempts are successful, and build in them the confidence and skill that they will need to continue pursuing truth on their own.

At the same time, we must also show them that achieving truth is not a foregone conclusion that someone else will always handle for them without any action on their own part, because if they thought that was the case they would have no motive to try to learn themselves. So to that end, we need to point out to them how any authorities on knowledge that they may be tempted to rely on are fallible, and that without their personal action such authorities may fail, not necessarily catastrophically or globally, but in any particular case, in which cases the individuals involved will need to be ready to pick up that slack and stand up to ignorance themselves.

But teaching not only oneself, but also others, can also help to cultivate that feeling of enlightenment, the feeling that achieving knowledge oneself is both possible and necessary. So more than merely helping people to learn themselves, we can also enlist them to help us teach other people to learn themselves, with the promise that doing so will in turn enlighten them, help them learn to learn themselves, and in doing so begin to build the groundwork for the kind of joint, mutual pursuit of truth necessary to underpin the kind of educations structure I've previously outlined. -

Hard problem of consciousness is hard because...The nature of the reality of number, is completely different than the nature of the reality of material objects, because the former can only be grasped by reason. It's the exact problem with a lot of modern philosophy, which fails to differentiate the sensory and the intelligible. — Wayfarer

Mathematicism like Tegmark's does differentiate the sensory from the (merely) intelligible ("merely" because we can also reason about the things we also have sensory experience of). The sensory, i.e. the concrete, the physical, is the stuff that's part of the same structure that we are, with which we are in communication if you will. There is other stuff that is not part of that same structure, that is not concretely real, but is of the same ontological nature as the stuff we are a part of; we're simply not a part of that stuff.

We don't have complete immediate access to the entirety of the structure of which we are a part, we only have access to the parts here, now, in the actual world -- including our memories of other times and places and so on, our imagination of possible futures and other possible worlds, etc -- and so to have any kind of a useful picture of even the concrete world, we have to reason upon and abstract away from the most concrete bit of reality we that have direct access to, because those most concrete bits, e.g. individual "pixels" of vision and so on, are uselessly specific.

Particular rocks and trees are slightly abstract objects, abstracted away from patterns of sensory experiences. The categories of "rock" and "tree" are abstracted from patterns of those particulars. Universals like "green" and "round" are abstracted away from them further still. Mathematical objects like numbers and sets even further still. And then from those distant abstractions we construct bigger more complex abstract objects that we take to be the universe as a whole. Whichever such abstract construction is a perfectly accurate map 1:1 of the entirety of the concrete universe, that just is the true concrete universe: whatever the correct theory of everything says the universe is, that's what the universe is, because that's what it means for that to be the correct theory of everything.

But that's still an abstract object, just like all the other abstract objects that aren't perfect 1:1 maps of the concrete universe. So if that's "real", if anything besides things like "pixels of vision" are real at all, then all abstract objects are real in the same sense as that one; but that one is special to us, because it's the one we're a part of, and so more concretely real, able to be observed, not just imagined.

besides, he still maintains a physicalist view of brain/mind. — Wayfarer

As he should. Mental stuff in one sense (access consciousness / easy problem) is reducible to physical stuff. But physical stuff is reducible to mental stuff in several other senses (phenomenal consciousness / hard problem, mathematicism inasmuch as information is considered "mental"). There isn't a clear divide between "mind" and "matter". -

Hard problem of consciousness is hard because...Yep. It is not uncommon for physicists today to think of all of reality as an informational structure. People like Max Tegmark argue (and I agree) that there isn't a hard ontological difference between abstract mathematical objects and the concrete physical world: the concrete physical world is just whichever mathematical object of which we are a part, and other abstract mathematical objects are just as real in the broadest abstract sense, they're just not concretely real, not part of the same structure as we are. "Concrete" is indexical, the way modal realists take "actual" to be.

-

Ownership - What makes something yours?But where do those others get those rights to it? Initially you said by being able to defend it. Then you’re saying that that defense is by the state. So if the state chooses not to defend their property, by this logic they have no rights to it; if the state just lets you take it then that’s perfectly okay for you to do, on this account.

Now it sounds like you think there are some other reasons why the state should or should not defend someone’s preexisting rights to things. Which is a fine position, but it’s counter to the “ability to defend it makes it yours” principle you started with. — Pfhorrest

It occurs to me that this is perfectly analogous to the Euthyphro Dilemma:

"God commands it" : "It is good"

::

"The State defends your possession of it" : "It is your property"

And then we ask "so if God commanded [thing we normally think of as bad] then it would be good?" and the Divine Command Theorist replies "God wouldn't command things that are bad", which then suggests that what is good or bad is independent of God's commandments; at best, if God is perfectly good, he would just never command things that are (independently) bad.

Meanwhile we ask "so if the State defended or allowed [thing we'd normally think of as theft] then it would be a legitimate exchange of property?" and if the might-makes-right proponent then replies "the State shouldn't defend or allow theft", that suggests that what is or isn't someone's property (and so what is or isn't theft) is independent of the State's defense of it; at best, if the State were perfectly just, it would never defend or allow any change of possession that was (independently) theft.

In other words, "Should the state defend your possession of it because it's yours, or is it yours because the state defends your possession of it?" -

Ownership - What makes something yours?But where do those others get those rights to it? Initially you said by being able to defend it. Then you’re saying that that defense is by the state. So if the state chooses not to defend their property, by this logic they have no rights to it; if the state just lets you take it then that’s perfectly okay for you to do, on this account.

Now it sounds like you think there are some other reasons why the state should or should not defend someone’s preexisting rights to things. Which is a fine position, but it’s counter to the “ability to defend it makes it yours” principle you started with. -

Hard problem of consciousness is hard because...Information is basically the modern equivalent of “Form” as the ancients would call it. Everything bears it. Information is the difference between a 200kg pile of graphite and a 200kg solid diamond grandfather clock: just 200kg of carbon atoms either way, but arranged according to a different pattern.

-

Ownership - What makes something yours?But what determines what others own, if “ability to defend it” determines ownership and all defense is done collectively through the state? If the state (with your input, but not your exclusive input) decides not to defend your ownership of something and instead to defend someone else’s ownership of it, doesn’t that make it then rightfully theirs on this account of might makes right?

-

Ownership - What makes something yours?I read it yeah. It sounded like you were saying that defending your acquisitions is what makes them yours, and that a state is needed to make sure you don’t acquire things from other people that you have no right to — but that raises the question of why those others have a right to them instead of you (that a state is needed to defend), if they’re not able to defend them themselves, that being the criterion given for what makes something yours.

If you’re saying instead that whatever the state will defend for you is what is yours, that’s very different from the original criterion. It’s still might makes right, sure, but it acknowledges that where a state exists it has all the might, and so all the rights (on such an account), and whoever it decides owns something thus becomes the fact of ownership, a far cry from the “defend it yourself” criterion implied originally. -

Ownership - What makes something yours?If those others could not defend their rights to the property in question, then how is it that they had any such rights to begin with, on this account of power = ownership?

-

What’s your philosophy?Thanks for finishing off the questions! I can’t respond at length now but I hope that you enjoyed the answering and that others can give you some feedback before I get the time.

-

Ownership - What makes something yours?To own something just is to have rights over it.

What qualifies you for rights to something is your undisputed habitual use and possession of it. -

Hard problem of consciousness is hard because...Okay, so am I, but then that is prior to any kind of processing of the experiences.

-

Hard problem of consciousness is hard because...

On my account there isn’t any “stuff” that would need to be observed or empirically analyzed, and there isn’t anything more for science to understand about it. I’m not positing that there are any other kinds of substances or properties besides physical things and their ordinary empirical properties — I’m saying that noting the difference between a first person and third person perspective on that same physical/empirical stuff is sufficient account of “phenomenal consciousness” and there’s nothing more that needs saying about that.it has no possible answer as to what this 'stuff' is or how it can be observed or brought into the ambit of empirical analysis. So it becomes another of the 'promissory notes of materialism', something which we are assured 'science will one day come to understand'. — Wayfarer

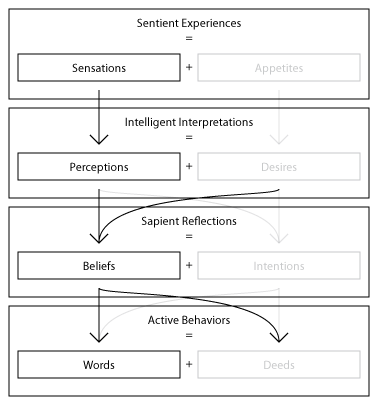

It sounds like you’re talking about a function that I would call perception, which is the interpretation of sensations, which are one direction of fit of phenomenal experiences, which are what I’m talking about. Such perception is the second to last major class of function in the larger function that I picture access consciousness to be, the last one being reflexive judgement of those perceptions and the formation of belief through one’s self-awareness and self-control. I suspect you are instead picturing the whole of access consciousness as just that last reflexive step, and so everything before it as “phenomenal consciousness”, but I don’t think that’s consistent with the original definitions of the terms.

In the picture below, the first layer is what I consider phenomenal consciousness, and I think you think the third layer is access consciousness, and you group the second layer with the first while I group it with the third:

That bit you quoted sounds like something I agree with, but not anything to do with phenomenal consciousness. -

Hard problem of consciousness is hard because...That’s worth exploring yes, but that’s a question of access consciousness, not phenomenal consciousness.

I heavily elaborated my last response while you were responding to it BTW. -

Hard problem of consciousness is hard because...The point is not to solve the problem but to dissolve it. Saying phenomenal consciousness, not just access consciousness, arises from computation still leaves the question of how and why, a seemingly unanswerable question as you point out in the OP.

Philosophy progresses by breaking down those intractable problems into either tractable problems for science to go solve, or non-problems that don’t need solving. The question of consciousness breaks down into two different questions, one of each kind. The tractable one, the easy problem of access consciousness, is just a question of functionality for psychologists, neuroscientists, and programmers to figure out.

The “hard” (non-)problem of phenomenal consciousness is whatever’s left after that: if we built perfect functional simulation of a human, would it have a first-person experience like we do? If no, why not, what’s different about it, besides the functionality that we’ve already stipulated is the same? If yes, then what is it besides the functionality, which we’ve already bracketed, that gives it that first person experience? My answer is “nothing”: there is no mystery to be explained, there is nothing besides the functionality of access consciousness that differs between a human and something that else that we wouldn’t normally call conscious, so whatever it is besides that functionality that might be required for humans to have a first-person experience, that is something trivial that’s just part of being, something everything has, and only the functionality, the access consciousness, is different.

I’m not saying that there are two kinds of substance, or two kinds of property, or anything like that: just that we can look at the same things, all things, which are all metaphysically alike and differ only in functionality, from two perspectives: third person / objective, and first person / subjective. That difference in perspective is all there is to phenomenal consciousness, and the functionality of access consciousness is all the rest of the explanation for consciousness, which is no longer a philosophical problem but a scientific one. -

Etiquette and diplomatic reasoning; A space where we can discuss how we engage with one another.I think the Principle of Charity is the most important starting point. I always try to make the most sense out of what someone else is saying, and then if I disagree with it, to put myself in their place and highlight the problems that I would run into thinking that way, and how I would find myself compelled to change my mind in response to those problems.

-

Hard problem of consciousness is hard because...Perception is something more than just raw phenomenal experience. To truly perceive, in the way that humans do, requires quite a bit of processing, sure. And even just perception like that isn't enough to count as consciousness in what I think is the ordinary way we mean it; that takes even more, and reflexive, processing.

But all of that is access consciousness, the subject of the easy problem of consciousness; which is really quite harder, because you have to do empirical science to explain it, but it's philosophically easy because we can say "the rest is just empirical science" in the way that mathematicians can say "the rest is just calculation" after all the abstract work is done.

The philosophically hard problem about phenomenal consciousness asks what exactly is it besides all of that functional stuff that gives us the subjective, first-person experience of all of that happening, and if you built a machine to do all of the same functionality, would it lack that subjective-first person experience, or would it have one just like us, and if so where does that come from and why?

The contemporary panpsychist answer is that there isn't anything special that gives us subjective first-person experience, there just is a subjective first-person experience to everything. But what that subjective first-person experience is like varies with the function of the thing, such that only complicated reflexive systems like us have an "internal life" (because we are experiencing our own self-interaction as well as just reacting to the world). So if you built a machine to do all the same functions that human brains do, it would automatically have the same kind of subjective first-person experience that humans do, and there's no need to explain where that came from, because it's not something that just popped into existence when you built that functionality into it: the experience is built out of simpler experiences that were always there, right alongside building the function out of simpler functions. -

Fake BanningsI dunno, banning yourself for being crazy sounds like a pretty crazy thing to do.

-

PrideI think it is useful to distinguish between two senses of "pride". Both bear a kind of opposite relationship to the concept of "shame", but a different kind of opposite relationship that I think can be more clearly expressed in functional notation.

One sense of pride is the negation of shame about something. proud(x) = ~ashamed(x).

The other sense of pride is shame at the negation of something: proud(x) = ashamed(~x)

Something like Gay Pride is usually used in the first sense. Gay Pride is usually just about not being ashamed to be gay. It's not about being gay being superior to being non-gay; just about being gay being not-inferior to being non-gay, because there are people who assert that being gay is inferior.

Something like White Pride, on the other hand, is usually used in the second sense. White Pride is usually about how there is something shameful about not being white. It's about being white being superior to being non-white, not just about being white being not-interior to being non-white, because nobody is asserting that being white is inferior.

That second sense isn't always bad though. Most of the kinds of pride in achievements are of that second kind. For example I'm proud to have gotten good grades in school, in that I would feel ashamed to have gotten bad grades, and I'm glad that I didn't. I think it only becomes toxic when someone has that kind of pride about things that either aren't actually rankable in terms of superiority or inferiority (like race, sex, etc), or about things that are beyond someone's personal control (like how rich or poor your family is, or what abilities or disabilities you were born with). About those things, it is more appropriate to feel pride only in the first sense, of being merely unashamed. -

How much philosophical education do you have?"Positivist" seems to fit, thanks.

(I remember the teacher of the class asking something like what's my philosophy, and I started to explain string theory to him, completely not getting what the question even was. A few years later, in a political science class my first year in college, I remember thinking that "my philosophy" was an ethical stance I had come up with that was basically utilitarianism though I'd never heard that word yet).

basically retook a lot of school classes with my students. I kept thinking "Wait! I learned this before? Where the heck was I? If all students actually remembered all this stuff after school, everyone would be so smart!" — Artemis

I remember having a similar thought after re-learning some basic grammar concepts (like subjects and objects of sentences, predicates, etc) incidental to learning logic as I started to study philosophy, though in my case it was more that memories of having studied these topics in elementary school came back to me as I learned them anew, and I was shocked to remember that something like this was being taught in elementary school.

I think an offshoot of that thought process was how I came to the conclusion that basic propositional logic should be taught in junior high alongside elementary algebra, since they use a lot of the same mental skills. I literally exclaimed out loud, upon seeing propositional logic for the first time in my first English class at college, "it's like algebra with words!" -

Hard problem of consciousness is hard because...It looks to me like the difference between (A) and (B) arises solely through propagating the conceptual distinction between phenomenal and access consciousness through the same evidence; the argument is really over whether the distinction makes sense in light of what we know about consciousness. Is there one construct (functionality alone, account B) or two (functionality and phenomenality, account A)? — fdrake

Your account of the differences between 180 Proof and I sounds pretty accurate to me, except I'm not really arguing that there is anything substantial to phenomenality, I'm just addressing the topic as it is brought up in philosophy; all I think really matters is the functionality.

I think I've said this already in this thread (I've said it all over other threads before definitely), but to me the situation is analogous to natural vs supernatural. I think that everything is necessarily natural and that "supernatural" things don't make any sense, the concept of something being supernatural is incoherent; but nevertheless, I say that everything is natural, which turns out to not really mean anything because naturalness is a completely trivial attribute of everything. Likewise, I think that everything is "phenomenally conscious" as that term is defined, and philosophical zombies don't make any sense, the concept is incoherent; but nevertheless, I say there are no philosophical zombies, and everything has "phenomenal consciousness", which turns out to not really mean anything because "phenomenal consciousness" is a completely trivial attribute of everything.

And the two things -- supernatural things and philosophical zombies -- are unreal for the same reason, seen in two different ways: reality is made up of the network of interactions between its constituents, which interactions constitute the phenomenal experience things have of each other and the empirical properties things have, and for a thing to be supernatural is for it to have no empirical properties (and so to be completely disconnected from everything else in reality, and so unreal), while to be a philosophical zombie is to have no phenomenal experience (and so to be completely disconnected from everything else in reality, and so unreal).

Pfhorrest

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum