Comments

-

Why Not Nothing?_AnsweredThere are moments when I find "something" disappointing, I'll admit. This is one of them.

-

Cosmos Created Mind

Gosh. You sure seem disappointed to me. Extensively so, in fact. Or is indignant a better word? Regardless, quod scripsi, scripsi. -

Ennea

I'm merely trying to explore what you were before you became human. I don't know what "commonplace matter" may be. I suppose you may have been "just" commonplace matter up to the time you became human. But over the billions of years you lived you may have been an animal, or perhaps commonplace matter that was part of an animal.

I assume you were born, and had a mother and father, or were commonplace matter which was a part of either or both. If not, did God or something else intervene and make you human?

Probably not, I would say. But if not, wouldn't you have been your mother and/or your father, or a part of them? And before that their ancestors down through the ages (who may have included non humans)?

It seems you may well have been a mammoth, then. Or that you may have a very peculiar way of defining what you are. -

Cosmos Created Mind

Well, I think you'll find my thoughts, such as they are, disappointing.

As for the title of this thread, I'm leery of the use of the word "created" (or other variations of "create"). I think it's too often associated with a conscious choice or act. I have the same concerns when it's claimed that we, or our minds, "create" the world. We don't. We're organisms having certain characteristics that are part of an environment. We don't make the world of which we're a part.

So I don't think it's appropriate to speak of the cosmos creating mind if it's intended to suggest the cosmos somehow intentionally made mind, or us for that matter. I know of no evidence supporting those claims. Nor do we have any evidence that something transcendent (outside of the universe) did so.

Given the information we have, I think the best evidence suggests mind arose as a result of substances or processes that are part of or take place in the universe. If that's the case, I have no idea how that worked. We seem to have a lot yet to learn about the universe, so maybe we'll know someday. Now we can only speculate. -

Deep ecology and Genesis: a "Fusion of Horizons"

For my part, I think that until such time as it's established we can know anything beyond the universe of which we're a part, we shouldn't claim to know of the existence or characteristics of any being or souce outside of it.

Perhaps that's a theological statement, though. -

Deep ecology and Genesis: a "Fusion of Horizons"

It seems to me that the issue which first must be addressed is whether theology is appropriately a subject of discussion in this forum. Sadly, there have been many threads devoted to the question whether God exists (a question which I wish would never be raised). So, perhaps that question, at least, may be considered here, much to my regret.

Christianity has a history of having recourse to philosophy in a relentless effort (which I think has been unsuccesful) to justify or at least provide something resembling a rationale for some of the bizarre beliefs and questions which arise due to its convoluted, confusing narrative--three persons-in-one deity, which includes God's Son, who is nonetheless begotten not made, one in being with the Father, born of a virgin, both God and man, who was cruelly killed for our salvation, descended into Hell, then resurrected, etc. So I think Christian theology is peculiarly suspect as philosophy. So much to explain!

But maybe some issues are allowed. I don't know. -

Deep ecology and Genesis: a "Fusion of Horizons"

I would call it an awkward relationship. Christianity's debt to pagan philosophy is enormous, but Christian philosophy, such as it is, is necessarily a kind of special pleading. All inquiry has a pre-established end. -

Deep ecology and Genesis: a "Fusion of Horizons"

Well, that's one way to insert the Bible into a philosophy forum. But I wonder at it, as the Bible warns us of philosophy's evils more than once. For example:

"See to it that no one takes you captive through philosophy and empty deceit, according to human tradition, according to the elemental spirits of the universe, and not according to Christ."

Colossians 2:8, Bible, Standard Revised Version, Catholic Edition. -

An Introduction to Accounting for Lawyers - the ultimate byline

Very clearly a joke, yes. -

Are trans gender rights human rights?

What is being said when it's claimed women have the right not to be subjugated? If we say that means they have the right to vote, we refer to a legal right. We don't refer to an "inherent right to vote "

One of the problems when we speak of "human rights" is one of lack of context or definition. When we try to define them, the definition which results is either so nebulous as to be useless or is dependent on legal rights. The example I give above applies context. If we say they have the right not to be treated as property we're not saying they have the right not to be property; we're saying that they're not property. In other words, as to women men do not have or should not have the legal rights they may exercise or have to property. -

Are trans gender rights human rights?

I must not have made myself clear. It makes no sense to me to speak of human rights or any rights outside of legal rights. -

Are trans gender rights human rights?It seems to me that using the language of "rights" outside of the law constitutes a form of wishful thinking.

A "right" which isn't a legal right (i.e. enforceable and subject to protection under the law, the violation of which is compensable) is nothing more than something which it's maintained should be a legal right, or should be considered as a legal right although it isn't one (which I think makes no sense).

So, I think the appropriate question to ask, if one wants to do so, is: Should what's being considered be legal rights? -

The purpose of philosophy

My point is these are not uniquely philosophical questions. They're not questions that philosophers, in particular, face "enormous pressure" not to ask. -

The purpose of philosophy

None of these resemble the questions referred to in the OP. They are, instead, questions which may be asked by most anyone most anywhere, e.g. at a Thanksgiving dinner. -

Cosmos Created MindThe ancient Stoics were stubborn materialists, but believed in a rarefied form of material, generally called pneuma, which was the generative force of the cosmos. Pneuma was a part of all things, organic and inorganic, but had different grades, one of which formed the rational mind/soul of human beings.

Perhaps they were pantheists or panpsychists--I don't particularly care which. I find the general idea of such a cosmos attractive. But I agree that if there is something similar to pneuma it will be established through science, not philosophy. -

The purpose of philosophyI confess I wonder just what questions philosophers have asked despite "enormous pressure" not to do so. Of those mentioned in the OP, the only one I think has, and may still, generate serious opposition or controversy is "What is God?" Some (like me) may think that question isn't or shouldn't be of any concern to philosophers, but outside of wishing it not be asked or discussed and perhaps sighing when it is in my presence, I can't recall enormous pressure being applied to prevent it from being asked.

Efforts made to prove that God does or does not exist seem to anger some and provoke bitter responses, it's true, but the unfortunate prevalence of such efforts establishes that any pressure to suppress them has been ineffective.

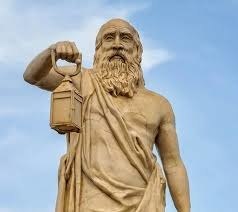

There is the example of Socrates of course, and whenever and wherever the Abrahamic religions or others similarly intolerant and exclusive hold sway there's very serious pressure applied to repress the question IF it raises other questions related to whether the God favored by the powerful really is God.

I think that the questions mentioned in the OP are so abstract that the claim there is "enormous pressure" not to ask them isn't credible. They lack context--like so much else in philosophy. Imagine enormous pressure being applied to prevent consideration of what it means to know something, or what it means to exist. So I ask for examples of these dangerous questions it's the purpose of philosophy to ask and address. -

The purpose of philosophy

"Thinking in the face of pressure not to" sounds rather like Hemingway ("grace under pressure"). The philosopher as matador, perhaps, fighting an unusually ponderous bull fed on platitudes? Or out hunting the dreaded guardians of the common herd of humanity? Perhaps philosophers in that case would be taking themselves too seriously.

Never stop questioning? Maybe have a reason to question, first. -

How to use AI effectively to do philosophy.

In fairness I should note that I find it difficult to attribute any significance to questions regarding Being. So, naturally enough, Nothing means nothing to me.

My reference was merely to the fact that the obscurity of H's work has prompted his admirers to, seemingly, compete with each other in providing explanations of it. -

How to use AI effectively to do philosophy.

It's really quite good at describing and summarizing these opposing positions. The lawyer in me admires this. I think it will be very useful in preparing and responding to legal arguments. I've chatted with it about it's application in the practice of law. -

How to use AI effectively to do philosophy.

Ugh. It seems that AI can successfully parrot

the explanations of Heildegger's many apologists. I'm with Carnap in this, of course, but am willing to acknowledge that the phrase may be an inept stab at poetry of a sort, which I think is what Carnap suggested as well.

That said, I think it's a good response. -

How to use AI effectively to do philosophy.

Well, it's output seems generally well written, though not scintillating. And, what's written speaks for itself. I think it should be identified when used but otherwise am unconcerned. I long to see its comment on such gems as "Nothing nothings." -

Banning AI Altogether

I merely emulate Wittgenstein, who rightly noted that a serious and good work of philosophy could be (and I would add has been) written consisting entirely of jokes. -

Banning AI AltogetherI was under the impression that intelligence of ANY kind had already been banned on this site.

-

Does Zizek say that sex is a bad thing?

Your confusion is understandable. Incontinence will result in voiding, and so causes the void. But the void isn't itself incontinent. -

Who is the Legitimate Author of the Constitution?

If the Constitution is changed, or abolished, it will have no more to do with whether it's "legitimate" than when it was created. Systems of law exist regardless of morality or principles. Laws apply whether they're good or bad. -

Who is the Legitimate Author of the Constitution?

Perhaps. But one should ask oneself, sometimes at least, what is achieved. Even if we merely play games, then at least there's a winner and loser. -

Who is the Legitimate Author of the Constitution?I wonder if our fascination with questions that don't matter has ever been given serious study. But now I think of it, that may not matter either.

-

Is there a purpose to philosophy?

It may be that I don't understand what you mean by "external world." If you mean by it the world we're part of, I don't know why you call it "external." External to what?

I certainly don't think we can't know the people and things we interact with every moment of our lives. What reason is there to think I don't?

Judging from our own conduct and how we live our lives, none of us actually doubt their existence or believe we don't know them. Claiming we nonetheless can doubt their existence or can't really know them is insist on a difference which clearly makes no difference. -

Is there a purpose to philosophy?[quote/Outlander]Just because someone convinces themself, or perhaps an entire society or even the whole world a given something is true and that a given something else is false, doesn't mean what they have convinced themself or others of is actually true or false."[/quote]

-- Outlander

I'm not sure what distinction you're making between true and false and actually true and actually false. More generally speaking, I'm sorry but I don't understand your point. -

Is there a purpose to philosophy?

Finding the way out of the fly bottle means there is no "external" world-- there is no world separate from us, in other words. We're not observers of the rest of the world; we participate in it interact with its other constituents every moment of our lives.

So, being free of the fly bottle doesn't mean one accepts the existence of world "external" to us. One accepts, instead, that there's a world and that we're a part of it. -

Is there a purpose to philosophy?

I don't understand. If someone finds they've been trapped in a fly bottle of their own making, they're free of it. Their metaphorical eyes have been opened (the fly bottle is of course only a metaphor as well). They're to be congratulated, not denigrated. -

Is there a purpose to philosophy?

Only if you're still buzzing around in the fly bottle. Once out, you may dare to think about, e g., your interaction with the rest of the world as an organism in an environment of which you're a part, and with others. But for those who like being in the bottle they've built, they may continue to indulge themselves. -

In a free nation, should opinions against freedom be allowed?

I'm not sure what nation has laws making employment discrimination a criminal offense. Please let me know which does. Nor do I know of any jurisdiction in the U.S. that provides it's employment discrimination to hold an opinion. Making employment decisions because someone belongs.to a particular race or sex is different from merely holding an opinion, though.

Ciceronianus

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum