Comments

-

Child Trafficking Operation We Should All Do Something AboutMy basic philosophical view here, which seems disturbingly necessary to elaborate, is that we have a universal duty to protect children. We must do our best to protect children wherever and whoever they are. Most of the time we can't do much about the situation of children far away (except engage in very long and cumbersome institutional processes starting with voting and local political engagement).

However, in this case, the fact that a whole group of Finnish child welfare corporations have optimized their data processing to both steal information and allow for traceless impersonation of their corporate identity, is a situation in which simply spreading that information can help protect children far away.

For those who believe in a duty to protect children, it is very little time to make a report in whatever country you are in, and that may result in someone checking and finding something. It also can not possibly be a false alarm as this incarnation of a scheme is useful to anyone needing to deal with anti-fraud related to child trafficking to know about and so the justification for and execution steps for more thorough checking.

I reported this immediately to all the authorities here in Finland over 2 weeks ago, and there's now a Health Ministry investigation into these data breaches, but what has not happened is anyone phone me to explain how this is not as alarming as it seems to be; if they did I would repeat such reassurances here. -

Child Trafficking Operation We Should All Do Something AboutWell, its a good thing you’ve brought this to this forum. Once its in the hands of an obscure philosophy forum there is no end to the help such a highly influential internet place will provide. — DingoJones

This is public information, anyone can report it in any police reporting or child trafficking reporting system of their country; can usually be done easily and also anonymously. If this scheme perfect for trafficking children has been used to traffic children that may only be find-out-able by spreading the notice as far as possible until someone gets the notice and happens to be like "ah yeah I remember these guys and this Finnish company moving children around".

And if more then one notice of the same thing arrives, that just usually encourages more thorough checking of records and asking around, so there's no disadvantage.

We also don't really know all the personal details of even the members of the forum, much less any lurkers out there, maybe there are readers in law enforcement (that isn't corrupt) or anti-trafficking networks that can take more specific actions. -

I am no longer under investigation for mad crimez

Which I was really puzzled by (maybe my sample of people was maybe really strange) until the genocide started, and what I had been experiencing in my little microcosm of family and former-friends and Finnish police (quite famous in Finland for being racist fascists) was suddenly on the scale of our whole Western society: People have seen movies in which we are emotional about a holocaust and do not accept the holocaust and do something about a holocaust, but that's something people do in movies (aka. famous actors no one should ever pretend to "be like" and try to share in their glory) and not "the real world" where you have to be realistic and accept things are the way they are. -

I am no longer under investigation for mad crimezThank you , it's really appreciated.

Most members of our Western society, that I've talked to, are not in anyway disturbed by false accusations, and even less disturbed by the implication that if the accusation of defamation is false it's because there's sufficient evidence the money laundering is definitely real and police obviously haven't been investigating those actual crimes these 4 years.

People try to explain to me how of course corporate people laundering money will accuse me of defamation, and that of course police are going to cover for them, and of course if I then complain about police obviously covering up money laundering that of course police aren't going to like that and they have their buddy system and of course they'll harass me even more.

This is all after they've accepted my account of things is true due to my having actual evidence.

Basically explaining in minute detail how the corruption works truly believing that I just don't understand how the corruption works and that once I do then I'll be able to accept it, and are truly unable to understand that I don't accept the corruption. I'll try to reassure such people that I definitely get that the cops have a buddy system to shield each other from any sort of accountability for their own actions, but the difference in values in that I don't find that acceptable, and not that I haven't accepted yet because I don't understand it. And they'll just repeat to me how cops look out for each other and really don't want me pointing out they've been covering up money laundering, they'll really not like that you see.

And I can talk to these kinds of people basically as long as they want, and they simply can never accept that what they describe in detail and clearly identify as corrupt actions by police and prosecutors, I simply won't enable and tolerate. What's weird is that they truly believe that I'm just not understanding things, that I'm stubborn basically, and simply cannot see my point of view of seeing the corruption, understanding the corruption, and just not going to accept the corruption.

And it's really strange as we have so many media productions of whatever form in which fighting corruption is the central theme, so you'd think (at least I did think before) that people would see what the motivation is, even if they personally would keep their head down or indeed be happy to take a bribe. But if I point out these kinds of stories as an example of what I'm talking about (that I don't like corruption and therefore will do something about even at some cost to myself) the response is just "you're not in a movie!". -

I am no longer under investigation for mad crimez

How could this possibly be BS?

Do you even formulate arguments before making claims? Same as the data system that is both a GDPR breach that happens to be ideal for child trafficking, you simply make contradictions and address zero points.

Not that you're persuadable by evidence and reason, but if others are curious, there is inaccuracies in my report of these events:

Police case number 5680/R/6414/22

Viman Tomi POL <TomidotVimanatpoliisidotfi> Tue, Aug 23, 2022 at 7:26 AM

To: Eerik Wissenz <wissenzatgmaildotcom>

Hello Eerik,

The minimum punishment of the crime has to be over 4 months.

”1) häntä epäillään tai hänelle vaaditaan rangaistusta rikoksesta, josta ei ole säädetty lievempää rangaistusta kuin neljä kuukautta vankeutta”

Harassing communication says the following:

“1 a § (13.12.2013/879)

«Viestintärauhan rikkominen»

Joka häirintätarkoituksessa toistuvasti lähettää viestejä tai soittaa toiselle siten, että teko on omiaan aiheuttamaan tälle huomattavaa häiriötä tai haittaa, on tuomittava viestintärauhan rikkomisesta sakkoon tai vankeuteen enintään kuudeksi kuukaudeksi"

Meaning the minimum (which would have to be over 4 months) is a fine. The maximum potential punishment for harassing communication is six months.

Tomi Viman

Senior constable

Central Finland Police Department

Tampere police station

Sorinkatu 12, 33100, Tampere

puh. 0295 445 831 — The Official Public Record

What I was suspected for kept on changing, it started in 2021 as defamation, then at the time of the above email it was harassing communication, later it became stalking, and then changed back to defamation and harassing communication.

For anyone interested in evidence, the key parts are in the mentioned folder: https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1SXU6VkygIWM14S4O-IQQUhlz41qYBjFH?usp=share_link

Which is a super abundance of evidence of money laundering and why 4 years later the investigation into me for defamation and harassing communication of my reporting and explaining how the money laundering worked to the auditor, corporate attorney and board members at the time, is obviously not a crime but reasonable suspicions to have and reasonable corporate actions to take. The harassing communication is from the corporation inviting me to negotiate and then my explaining things (at the time I hadn't compiled the evidence into PDF's so I'd explain each key point in texts or email as part of the negotiation) and then these messages (in a negotiation I was invited to) were just tallied up in a table as like 100 messages in January! That's harassment!

The police officer above even admitted (in a recorded call) that he didn't have copies of these messages, just knew I sent a certain number. Which also just completely insane, you can't "talk about evidence" that you have in your possession and police not review that evidence before creating the investigation. Reason my actual messages weren't submitted as evidence, nor collected by police, is that it's explaining all the crimes in the context of a back-and-forth negotiation.

Hence my explaining to police that they shouldn't create a mystery box.

I filed the reports of actual crime months before they put me under investigation, so they could have easily phoned me and understood what evidence actually exists.

Normally corporate crime is happening all the time, in many if not most corporations, but perpetrators don't create sufficient evidence. So, my understanding is police boldly assumed that this would be another case of corporate crime they can't do anything about because corporate people cover their asses. However, that's not some guarantee, obviously corporate people fuck it up every once and a while, so it's unclear to me why police decided best not to check what it actually is in this case. Hence constable Meletus helps us understand the police attitude in this affair. -

How true is "the public don't want this at the moment" with regards to laws being passed?↪boethius While we have found common ground on this point perhaps you can then understand I was merely pointing out you might be better trying to communicate in the style of Feynman, who you agree is a good communicator, than say...Derrida. — unimportant

The major difference is Feynman was paid for his work.

But beyond that critical aspect, there are also different levels to things.

There is a level of communication to lot's of people, whether propaganda or then this "good communication" to attempt to convey actual truths, and there is communication to arrive at those actual truths to begin with.

Not every Feynman "actual physics paper", much less most papers Feynman himself requires to develop his own understanding, are going to be masterworks of oration.

So, in order to have the level of Feynman lectures attempting to share what physics has learned with ordinary curious people, i.e. non-specialists, you must have first the level of Feynman the physics professor and researcher, of which most ordinary people would understand essentially nothing of what that's all about.

For our purposes here, my view is we are a community dedicated to that upper level of how knowledge is attained in the first place and how exactly do we know that it's knowledge. I am therefore mostly concerned with my statements here being actually true than convincing, and therefore also getting into all the complex aspects of the subjects we deal with.

Now, if I was employed by a political party to communicate with the masses, then I would attempt to create the Feynman lecture version of what I am confident is the truth.

It would be a whole new task. -

How true is "the public don't want this at the moment" with regards to laws being passed?Yes sure I agree now I read it again that I was agreeing with the point Hitler made and I did mean to agree with the point at the time now I reread the context.

As above, Hitler was a fantastic orator. — unimportant

Yes, the Hitler role in this conversation is more ironic than essential to the debate.

I think there is discussion to be had about charisma vs propaganda or if they are indeed one and the same. I don't think they necessarily are the same thing. There are charismatic people that do not speak propaganda but charismatic people often do speak propaganda. — unimportant

My criticism of propaganda is specifically insofar as we're referring to the sense that it is manipulative.

"Good propaganda", in the sense of effective in controlling public opinion in the short term, will also have plenty of elements that are in themselves elements of "good communication", by which I mean both good and effective (and not manipulative). Good propaganda will use plenty of actual facts, elements of logic and reasoning, clarity and well-spokenness, charisma and so on, insofar as it serves the overall manipulative objective.

We have an example of good propaganda with Hitler.

I'd propose an example of good communication as Feynman, exemplified in the Feynman lectures.

Both Hitler and Feynman are charismatic and use many of the same rhetorical methods. The difference being Hitler is trying to manipulate public opinion to conquer the whole world and liquidate whole classes of people he dislikes and breed a race of supermen, whereas Feynman is trying to convey actual truths about physics to those who are interested. -

How true is "the public don't want this at the moment" with regards to laws being passed?↪boethius I guess you are deliberately pushing the Hitler narrative to illustrate the problems with propaganda. — unimportant

Maybe just accept what happened.

You saw something you liked in a citation literally Hitler, original citation being:

The most brilliant propagandist technique will yield no success unless one fundamental principle is borne in mind constantly and with unflagging attention. It must confine itself to a few points and repeat them over and over. Here, as so often in this world, persistence is the first and most important requirement for success. — Adolf Hitler

And your use of this Hitler wisdom being:

unless one fundamental principle is borne in mind constantly and with unflagging attention.

— Adolf Hitler

This is what I tried to tell boethius to perhaps allow his points to get across better but he dismissed it and continues with is disjointed ramblings. — unimportant

Which I get it: Hitler doesn't say only false things, and what he says here is true enough as far as propaganda is concerned. Most people in the West would agree with Hitler on this point and definitely the PR people of every major Western political party are going to harp on about "staying on message" exactly as Hitler prescribes.

However, I disagree with the effectiveness of propaganda and so make the rebuttal ... as well as point out the clear fact that you're citing Hitler to make your point, as more a basic debate tactic.

But if we're talking about fundamentals, not caring what Hitler thinks about the subject, the problem with propaganda is that people resist being manipulated.

By definition you cannot want to be manipulated on the whole. By that I mean the difference between manipulation that is part of an overall consent, such as the manipulation of perception in seeing a movie, and a "manipulation overall" such as being tricked into seeing a movie that you don't want to see.

So, insofar as propaganda is manipulating public opinion, people resist that and so even if the cause really is good (which is difficult to tell if it's soaking in propaganda), and the propaganda achieves some actually good objectives, people will realize the methods of manipulation and undo the effect as well as lower their trust in your movement.

For, if people are going along with something because they've been manipulated then it's not because they are actually convinced, and sooner or later the contradictory beliefs will rise to the surface and all that time spent manipulating them will have far worse effects than having done nothing. -

How true is "the public don't want this at the moment" with regards to laws being passed?↪boethius Huh, interesting, so that is why you went silent on the other thread all of a sudden. I did wonder why you suddenly stopped commenting.

Didn't realize you were angry. — unimportant

The silence is not voluntary, and I mean to get back to that thread.

Certainly not angry about anything here.

I encountered this insane data breach that enables child trafficking globally, which I posted about in the lounge. Child trafficking does indeed make me angry, but I'm fairly confident no one here is a child trafficker.

Criticizing me for not following Hitler's advice I just find amusing.

But sure, the Hitler's criticism is fair if the goal is propaganda, which one is free to argue that all political persuasions should be simply focused on propaganda all the time; of course, I disagree with that, and would provide the counter-argument that propaganda (in the sense of manipulating public opinion) is always counter productive.

However, it obviously has some drawbacks citing Hitler as a role model generally speaking. -

Child Trafficking Operation We Should All Do Something AboutJust to update on this issue.

One of the data controllers actually doing their obligations under the GDPR is the Finnish Ministry for Social Affairs and Health, as they ultimately "own" government health and welfare data that would be sent to the data breach (i.e. into the possession of anonymous individuals in the US).

The ministry notified the Data Ombudsman within 72 hours as the law demands and continue their own "process", which hopefully is also what the law demands (further investigation into the breach by the data controller once notified, and then notifying victims of the data breach if there is risk to harm to their rights and freedoms). Which is what makes the GDPR such a potent law that it obliges reacting to risk and not proof of harm.

Under the GDPR, I can't leak your ID either intentionally or due to some security vulnerability and then sit back and claim no one's proven any harm has actually been done yet, and even if that is proven then no one's proven it was due to this particular data breach, and not some other breach or simple carelessness on the victims part.

The judges not reacting to such an obvious data breach that so obviously puts children's lives in danger (just allowing the child welfare corporations to be spoofed due to zero email security is incredibly dangerous), was already obvious corruption and judge participation in organized crime and child trafficking, but now it's even more obvious due to other government organs reacting the data breach.

Which pretty clearly establishes the corruption of the judges. -

Child Trafficking Operation We Should All Do Something AboutAnd how many perfectly legal companies are involved in child trafficking? — Sir2u

Yes, child trafficking is illegal.

Or, are there illegal groups acting as legal companies to commit crimes? — Sir2u

In this case the companies described in the OP are breaking the law, violating the GDPR, having zero email security on their official domain and then sending all their information to an anonymously owned parallel domain in the US.

So, they are legal structures, the companies themselves, but the companies and at least some people involved are doing illegal things. In the same way that you are legally a person, perhaps even a legal citizen of a country, but can go onto commit crimes nevertheless.

If you're in the US, the laws being violated are equivalent to HIPAA.

It would not be too strange to find an individual practitioner who doesn't know what they are doing, doesn't realize their alternative magnet based therapy falls under HIPAA if they request people's medical info to optimize the magnetic chakra pulses (i.e. just because you are practicing alternative medicine does not mean you can practice alternative laws), but if you found a whole group of corporations employing trained experts that weren't HIPAA compliant in super obvious ways, that's simply not credible to entertain as a incompetent accident. So I have no hesitation to make the accusation that the reason this corporate group setup their informations systems in a non-compliant way ideal for trafficking children, is because they are trafficking children.

Now, there is an investigation by one data controller involved, so we will presumably know more at some point. -

Child Trafficking Operation We Should All Do Something About

To save you, perhaps others, a bit of time, you're confusing liability with actually being held accountable.

Liability is simply the potential to be held accountable and where. So discussions of liability are about what you could possibly be sued, fined or imprisoned for, and where exactly that can occur.

So where you will find no-liability is with sovereign immunity and its various extensions. For example that Trump cannot be sued for "official acts", or congress and parliament members can't be sued for the laws they pass, ambassadors running people over, are all manifestations of sovereign immunity.

But even so, there's then a confusing international legal system where people and states can nevertheless be held liable for acts they had sovereign immunity for within their own territory.

Who always has liability are regular people for what they do as well as regular corporations and their management, aka. board members (maybe somewhere there's special "sovereign" corporations that are not liable).

Now, even after the question of liability is perfectly clear, that doesn't mean accountability exists in practice.

As you note, corporations get away with a lot of shit all the time; however, the explanation for that is corruption of regulators and the legal system that's supposed to hold them to account, and not that they have no liability to begin with.

And even so, with corporations there's often some sort of process, a lawsuit does get heard after many years of legal wrangling but they manage to win by some subterfuge, or then they get some tiny inconsequential fine that's categorized as "the cost of doing business".

Someone who'e not liable at all for an action means there is no legal process of any kind that ever even begins. For example, in a liberal democracy you simply cannot sue parliamentarians for voting in a way you disagree with; members of parliament have zero liability for their votes on legislation. -

Child Trafficking Operation We Should All Do Something AboutThe world is a lot bigger than that, the EU is a small part of it. — Sir2u

Ok, well keep looking in the rest of the the big ol' world for a place where limited liability corporations don't have a board of directors.

Maybe not an EU corporation but as you said, this is supposedly, according to your reference of the US and children being taken into Finland from somewhere else. affecting the whole world. — Sir2u

Yeah I guess keep looking outside the EU if there's even one example of your claim.

Maybe you could look into the Vatican, they rarely answer to anyone. — Sir2u

The Vatican is not a limited liability corporation.

Wow, bit of a comedown from: — Sir2u

There's no comedown. Compromising people's data is itself harmful. If you disagree send me your ID, medical information, anything other data you'd consider private.

This harmful act of compromising child data in combination with zero security implemented allowing anyone to misrepresent these corporations anywhere in the world, even more harmful things can be done.

Since anyone could misrepresent this fraudulent corporation anywhere in the world, the only way to find that maybe to diffuse notice of this information vulnerability.

So I ask again, is there any evidence of any of these crimes being commited through the methods you are explaining. — Sir2u

There's evidence of other crimes involving (beyond the reckless GDPR breaches) these corporations are involved in Finland, as I've mentioned several times. It's not public information yet.

Now, as I've stated many times, the only way to see if this insecure system has been used for abductions elsewhere in the world is through getting the notice out.

Some bodies have been responsive to my notice and are investigating right now, which would usually indicate they found something preliminary, but I don't have more details and it is extremely normal that I would not be kept appraised of any investigation details (as I'm a private person).

All I can do (vis-a-vis child abductions and trafficking in other countries) is create a notice that a child welfare corporation (actually 2 of them) can easily be impersonated in a data setup ideal for child trafficking, and describe what this vulnerability allows.

I've been pretty clear with this message: DATA breaches are themselves harmful, there's other evidence of wrongdoing in Finland that is private information currently, and this completely unsecured and non-compliant setup can be used for a long list of crimes.

I have no issue providing a lot of analysis of these basic points because it's possible such analysis encourages someone to send the notice themselves in their own country, leading to records being checked and potentially child trafficking being frustrated.

For example, it may matter to someone that incompetence is really not a good explanation for why a non-compliant system would be setup in the first place, by an entire corporate group of child welfare corporations. If you're not familiar with how corporations work, what the laws are, how liability works, if limited liability corporations even have any management, etc. then it maybe difficult to evaluate. -

Child Trafficking Operation We Should All Do Something AboutHow this all applies to the subject of the OP, is that the companies concerned definitely have a board of directors and by not implementing the GDPR those board members make themselves personally liable to be sued by any victims of the data breach for their negligence as well as being fined by the state; fines up to 10 - 20 million Euros, but even a 1 million Euro fine would be a lot of money for the typical professional on a corporate board.

To make and operate a limited liability company you typically need lawyers to do a lot of things, board members typically concern themselves with how much money they could be liable for if the company is run negligently (as well as breaking what laws could land them in prison), and then typically seek advice, typically starting with lawyers, to be confident that won't happen. For, nothing obliges anyone to sit on the board of a corporation, so if you thought it was all reckless improvisation you can just resign and your legal problems are solved if you haven't caused any damages yet.

The rational reason to join the board of a corporation dealing with sensitive information and not have the slightest concern that even step 1 of information security has been carried out, that no information expert of any kind has been involved in designing and implementing information systems and their supervision, would be to commit crimes with this non-compliant information system.

The other explanation available would be being irrational and taking on massive liabilities without knowing the first thing of how a corporation should be managed, not seeking to know from anyone who does know, and just flying by the seat of your pants in taking responsibility for processes as sensitive and critical and prone to litigation as child welfare and protection processes.

There is no legitimate and rational business process that would lead a corporate board to implement information systems for sensitive information in a way that clearly and obviously violates the law in literally step 1 of their implementation (non-transparent ownership and ownership by an individual of the domain used to process children's information, and zero email security on the domain that is officially owned allowing impersonation) and compromises people's private information and put children's lives in danger of these information vulnerabilities being exploitable to impersonate Finnish child welfare and protection to fraudulently gain custody of children anywhere in the world.

You might say that "well, me and my friends would definitely be that reckless and stupid if we ran a corporation" but that begs the question of are you and your friends running a corporation right now, not to mention a corporation that houses vulnerable children?

More relevantly to the matter at hand, even if someone was genuinely unconcerned with liability of any kind and would go through similar events with zero sense of possibly being held accountable for one's actions, that is not a good defence for others breaking the law in such situations.

Standing up in court and saying "Well, Jimbo over there doesn't give a shit about the law, would break exactly the same laws I did without a second thought, he's just that much of a fucking madlad, and never in a million years would it even cross his mind that the law even exists, much less could even potentially lead to some sort of accountability for the consequences of his own actions; therefore, gentlemen, ladies, as Jimbo has no sense of responsibility and genuinely feels he could never be held accountable for his actions in a similar situation, no matter how reckless and damaging they are, I too should not be held accountable. I rest my case." I guess has some sort of logic to it, could persuade some people (definitely some members of our little philosophic community), but mileage may vary. -

Child Trafficking Operation We Should All Do Something AboutTo save time for anyone interested in how things actually work.

All companies of all forms are liable. The type of company determines who is liable. A single proprietor and partnerships usually have unlimited liability for the owner(s) / manager(s).

Why limited liability (.ltd) corporations are so common is because, as the name suggests, liability is limited. What this means is that the managers of a limited liability company, even less the shareholders, are not personally liable for the decisions they make on behalf of the company (such as in day-to-day management typically by the managing-director, in board meetings by board directors, and in shareholder meetings by shareholders).

The basic meaning of this is that a limited liability company can go bankrupt and no one involved is personally on the hook to pay the outstanding debts.

There is, however, a critical caveat to be off the hook for debts or other damages the company has caused others, which is exercising "due care". Due care is basically a catch all for not being criminal or a complete moron basically.

As you may imagine, if you've been embezzling money out of the corporation you can be held personally responsible for that, likewise if you cause damages due to negligence you can be held responsible for that.

Where the liability is limited is for bad outcomes of business decisions that were legal and did make some sense at the time, such as taking out debts to launch a product and that product just doesn't sell leading to bankruptcy.

Since we're talking about Finland, this manifests in the law as the first and only duty of management:

PART I: GENERAL PRINCIPLES, INCORPORATION AND SHARES

Chapter 1: Main principles of company operations and application of this Act

Section 8: Duty of the management

The management of the company shall act with due care and promote the interests of the

company. — Limited Liability Companies Act

As for the idea corporations don't need a board of directors at all, we'll soon see if there's even one country in the world where this is true, but in Finland it is definitely not true:

Chapter 6: Management and representation of a company

Section 1: Management of a company

A company shall have a board of directors. It may also have a managing director and a

supervisory board. — Limited Liability Companies Act

Section 8 Members: deputy members and chairperson of the board of directors

There shall be between one and five regular members of the board of directors, unless otherwise provided in the articles of association. If there are fewer than three members, there shall be at least one deputy member of the board of directors. The provisions of this Act on a member also apply to a deputy member. — Limited Liability Companies Act -

Child Trafficking Operation We Should All Do Something AboutDo you really think that this applies international? — Sir2u

Let's just start with the EU as qualifying as "international".

Can you name one EU limited liability corporation that does not have a board of directors?

Have you any idea how many countries have massive companies without a single member on the board of directors. — Sir2u

Please inform me. Can you start by naming just one massive limited liability corporation that has no board of directors?

And that does not include a bunch of oversees companies that operate internationally and are not liable to nor answer to anyone. — Sir2u

Again can you name one oversees company of whatever form (limited liability, partnership, single proprietor) that are "not liable to nor answer to anyone"?

But we're talking about Finland, so after answering these questions please clarify how it relates to Finland.

Are you saying companies in Finland are not liable to anyone in Finland?

As for the rest of what you wrote, it still does not answer the question! — Sir2u

I did answer your question.

Compromising someone's data, violating the law that is the GDPR and a bunch of other laws, is by definition harmful and causes suffering (one must worry how one's data maybe abused).

If you disagree, just DM me your ID, medical history, anything else you consider legally private information, thus making the point that you don't feel others having a copy of your sensitive information is in anyway harmful.

Other forms of harm have also occurred but I can't so easily disclose specific details of individual cases at this time, hence to focus on the legal violations that can be demonstrated using only publicly available information.

Since the information setup can be used to steal information and create fraudulent child transfer processes anywhere in the world, the only way to discover fraud in other countries, especially poorer countries with less robust systems, is that a victim of the fraud encounters this notice.

There is no possible downside to spreading the information, in particular to authorities in different countries who can check if they are possibly a victim of a scheme involving the fraudulent representation of these companies we are talking about. -

How true is "the public don't want this at the moment" with regards to laws being passed?This is what I tried to tell boethius to perhaps allow his points to get across better but he dismissed it and continues with is disjointed ramblings. — unimportant

I'm not a propagandist, I'm first and foremost here to subject my own analysis to critical scrutiny. The worlds of ethics, concepts and facts is quite varied, diverse and complex and so any one thing is often related to a great many other things; and so maybe literally Hitler literally describing his propaganda methods of choice isn't the best guide to explore and understand matters.

But I guess thank-you for outing yourself as a self described propagandist following Hitler's advice and footsteps.

Also notable, you confirm your unwillingness to engage in critical debate by mentioning and criticizing me but not using the forum's mention link that would automatically inform me of your comment. You want to criticize me without being sure I have the opportunity to address your criticism and yet you call me bad faith?

Remarkable. -

Child Trafficking Operation We Should All Do Something AboutAs to the question of why government criminal conspiracies and networks so often involve pedophilia, I would not attribute most of that to the machinations of intelligence operations, though of course that happens too, but crime is anyways happening all the time and intelligence agencies are involved in very little of it overall.

The reason pedophilia and government corruption (or large institution corruption such as the Catholic Church) is so associated I would argue is not simply confirmation bias that such scandals get the most attention, but that such conspiracies are the most stable and so survive the longest with the most advantages both against legitimate law enforcement as well as other criminal conspiracies wanting to dominate the same processes but for different criminal reasons.

For, the major weakness of a criminal conspiracy over time is its internal coherence. For example, even if the criminal conspiracy under consideration is well run with no leaks or weaknesses, for example just embezzling government money in a super sophisticated way or then compromising border security to run drugs and these sorts of crimes, the criminal involved may anyways get caught doing other crime, then they find themselves faced with doing time and have the option of using their leverage of their knowledge of this other organized crime they are involved in. Criminals are not necessarily the most stable and law-abiding of people and so often it's this extracurricular crime that gets criminals in trouble and motivates them to rat on their criminal colleagues.

So there are these accidental weaknesses in most criminal schemes which there is not really any good way to prevent.

The exception to this rule is pedophilia. It's very unlikely for someone to confess to being involved in pedophilia and child rape in order to avoid prosecution of other offences.

So accidental discovery of a pedophile network is unlikely due to chance encounters with law enforcement about other fucked up shit the members of the conspiracy do in their spare time.

Then there's intra-conspiracy extortion. Another pathway to breaking up a criminal conspiracy is when members of the conspiracy start extorting each other. The means of extortion in a criminal scheme is simply threatening doing the above and going and cutting a deal with law enforcement. Even if this doesn't happen, this lowers the trust and mutual respect required for team work to happen effectively, so even if the ratting out doesn't happen the conspiracy will likely cease to function effectively (members may start destroying evidence and making sure not to create new evidence so they are squeaky clean).

For the same reason someone is unlikely to confess to pedophilia and raping children to plead down other offences, they are also unlikely to threaten to do so.

In other words, pedophilia and child rape are crimes that form the long term basis for trust based cooperation.

Through a process analogous to evolution and natural selection it is therefore pedophilia based conspiracies that have an advantage for long term survival. The potential effectiveness of any cooperative venture is directly proportional to mutual trust. Take a military unit where people trust each other implicitly and absolutely compared to a military unit where everyone suspects everyone else of being either dangerously incompetent or even enemy spies; the former organization can attain high levels of effectiveness while the latter not so much.

So, over the decades, if a pedophilia and child rape ring within government survives it will become more, rather than less, robust and stable over time. The pedophilia and child rape ring will be acutely aware of who threatens them and they can use their existing positions, power and connections with organized crime outside government to remove or otherwise neuter those threats. They cannot only use their network to rape children, but make lot's of money in selling that service to others but also just any criminal scheme that the are in a position to execute on, such as simply embezzling government money, taking bribes, protecting the drug trade and taking a cut, and so on.

Since they can have high confidence the other pedophiles in their network are exceedingly unlikely to confess to child rape, they can work in a highly organized, methodological and long term fashion.

Criminal conspiracies that do not solve the classic prisoner dilemma and variations or intra-conspiracy extortion dilemma (which is just a threatening the prisoner dilemma to maximize gain within the conspiracy) described above, will be unstable and ephemeral. The other long term basis for criminal conspiracy, as Vin Diesel in Fast and the Furious informs us, is "family", but this criminal foundation has the weakness of everyone involved being obviously linked whereas pedophilia does not have this weakness. An entire government process could be completely filled with pedophiles and it would not be obvious that there is a connection between anyone, much less everyone, arousing natural suspicion, compared to a situation in which everyone involved, from police and prosecutors to judges and witnesses etc., are apart of the same family, which would seem curious to most people; so pedophile networks even have an advantage over family based criminal networks.

If you have a long term advantage, over time you will likely dominate the space concerned. Of course that doesn't mean any given pedophile that launches into crime has an advantage, just the smart ones that manage to build a cooperative network and get over the first hurdles in doing so. -

Child Trafficking Operation We Should All Do Something AboutAlso, to address the point of why they have an email setup with zero security, both on their official website and this anonymously owned .com domain that they process emails on, but exploiting this vulnerability to send fraudulent email would take some computer skills, this is not a paradox of contradiction but easily compatible.

Corporate crime is almost always committed with layers of plausible deniability built in. Even if negligence is not a defence to allow criminal processes under your supervision, it's still better to be facing negligence charges than co-conspirator charges.

"Oh I'm just dumb, I didn't think" is still better to be able to say than facing clear and unequivocal participation in a criminal scheme.

So, in this case, if the key criminal role of the management of these corporations is to create the vulnerabilities in the first place and then those vulnerabilities can be exploited by criminals committing the criminal acts themselves that have some degree of criminal separation, then this maintains some plausible deniability that the vulnerabilities are created intentionally to participate in human trafficking.

What is meant by "degree of criminal separation" is that the criminals who then actually make fraudulent emails and actually go traffic the children are working for someone (who in turn maybe working for someone) up to a top boss that can then deal directly with criminal corporate managers in Finland. The "criminal laborours", for lack of a better term, would then not need to even know that the vulnerabilities were created intentionally for the criminal operation to function, but for all they know they are exploiting accidental vulnerabilities. Criminal management in Finland can then be compensated in off-shore accounts or with other money laundering methods.

Likewise, people who actually work for the child welfare corporation in Finland can be completely unaware that information they handle is being stolen for the purposes of human trafficking. For example, you can setup parallel devices that download all the information and you could even tell your employee about these parallel devices and that they stay in the office as a backup; indeed, you could explain that as precisely due to the sensitive nature of the processes this is a necessary security measure in case they lose their device.

As importantly as all that, Finland is a high technology sophistication country, so everyone who does anything remotely professional has degrees and certificates and so on. You need training and a certification to work as a waiter/tress in a restaurant.

Description of the training

You will graduate as a waiter/waitress from the Further Vocational Qualification in Restaurant Customer Service. During the training, you will learn to describe, recommend, sell and serve restaurant food and beverage products. You will be able to serve customers in a spontaneous, friendly and responsible way and to act in accordance with the company’s business idea and service culture.

You will also be able to explain to customers the ingredients and preparation methods of the food dishes sold. You will be able to serve customers with special dietary requirements and to process payment instruments. You will learn to make sales accounts and operate profitably, as well as to use various working methods, appliances and equipment. — Waiter/waitress training, Omnia.fi

So if you need training and certification to be waiter/tress at a restaurant, imagine how much training and certification software engineers have who build GDPR compliant systems for handling ID, medical and court information have. A lot.

In this sort of professionalized environment it creates a further problem of how to recruit a competent software engineer into your criminal conspiracy.

Your choices are:

1. Hire competent and non-criminal competency and try to carry out your criminal scheme behind their back. But this creates the enormous risk that the slightest thing that goes wrong, a single error message or someone making contact to report some odd thing on their network (such as a bounded email or information transfer or what have you), could result in an investigation and immediate uncovering up crime. If you higher some actual IT firm that dates responsibility for the data, they may do their jobs. Even if you circumvent their policies they may change policies at anytime in a way that reveals the previous circumvention.

Really this choice is a non-starter since if you have the skills to defeat highly trained forensic data experts that work for companies that actually manage ID, medical and legal information, then you have the skills to do things yourself.

2. Recruit a expert into your criminal conspiracy. Problem here is that easier said than done. Information experts don't necessarily need the extra cash, if they did they might not choose child trafficking as their extracurricular criminal activity of choice. Furthermore, even if you did find such an expert to setup and manage your network in a way that was not obviously in violation of the GDPR and participate in carrying out and covering up all the criminal activity, you'd be working for them as they would know everything, have backups of everything and possess all the leverage they could possibly want to rat you out. Such a person could extort you at anytime for any amount, so playing things out you may end up losing your cut and still be ratted out, so what's even the point of doing crime in that case? So, hard to find such a candidate and even if one did exist you may want to stay in charge of your criminal operation which requires staying in control of the data systems necessary to carry out the crimes in question, leading to the last and best option if you are not yourself an computer and information expert of some kind.

3. You improvise the data processing setup in such a way that allows your criminal partners to use out-of-country cyber criminals to carry out the crimes exploiting the security vulnerabilities, without even knowing this is by design. Cyber criminals are of course available for higher globally; the issue above is finding someone actually qualified in Finland for data GDPR compliance that you will trust with a birds-eye view of the whole scheme. With very little IT skills you can setup an official website with Wordpress (what this "corporate group" we are discussing actually does) and have zero email security opening the door to be fraudulently misrepresented by your criminal partners elsewhere (also what they actually do). Likewise, with very little IT skills you can setup email on another domain that is registered outside the EU (and so far less compliance checklists to go through as just an "private person"), in this case to an anonymous individual in the US, and so simply bring all the data outside the EU and GDPR scrutiny of even the service provider (and entirely outside the supervision of any competent IT company, which is not even involved at all). Suspicious logs maybe subtle, such as downloading information to suspicious devices and making the occasional odd contact to legitimate conversation (a fraudulent conversation could be a mix of actual emails that don't contain crime and fraudulent emails to pass the criminal information).

This irregular and non-compliant setup will still be noticed by police, prosecutors and judges in charge of the legal cases of these child protection process, but they can be compromised in various ways (from bribes to extortion).

Unlike hiring some highly skilled IT person that would have all the information, have the skills to launder their cut and disappear if needs be, but most importantly be the single most valuable person to any actual police investigation, having backups of all the data and communications etc. (possibly also recordings and other things competent IT people can easily do), compromised officials are far more easy to control, can have very little knowledge of what the scheme even is (just that if they don't do what they're told they won't get their money ... as well as arrested or even murdered, capiche), and would have little to no leverage if ever there's a legitimate investigation, so you can be more confident they really do work for you and not the other way around.

In fact, my guess would be this kind of criminal enterprise starts in the public sector by high-up pedophile officials, such as your typical Finnish appellate judge, who then slowly grow their criminal conspiracy over the years, maybe starting small with just covering up child rape crimes purchased on the "normal" blackmarket, creating a clique of officials that carry out and then coverup rape crimes against children while also then creating relationships and links with organized crime; at some point it is realized a lot more money could be made by everyone and a lot more children could be raped by those involved if the government say ... I don't know, ... just spit balling here ... contracted out child protection tasks to a private corporation that can operate without scrutiny (normally social workers in Finland work directly for the government so therefore use information systems managed by and overseen by the government IT people with all sorts of robust systems and scrutiny in place).

It would be difficult to conceive of and execute on this plan purely from the private sector (we're going to setup this company and this non-compliant GDPR system to do crime, then get government contracts and simply assume anyone who needs to be compromised can be compromised at any given time), but would be easy to conceive up and execute on from the point of view of public officials that have both a birds-eye-view and means of compromising the processes involved and are already involved in this kind of crime and now want to streamline things. This transfer of government money to a private corporation dealing in highly sensitive processes with essentially zero public supervision of what they are doing, also enables your more ordinary embezzling and laundering of government funds.

Furthermore, often red flag reports go to some choke point, so only that point needs to be compromised to reassure everyone below them that "nothing to see here" for the scheme to go unnoticed (so even if lots of people may notice a red flag that doesn't mean they all must be compromised). If you are unfamiliar with how the internet works and how the GDPR works and just find it odd that this company uses an email that has no corresponding website, and is not their official website, if some judge, or police chief or data controller told you that they know already, not to worry about it, most people wouldn't think further about it as it's "not my problem anymore". In fact, most people when encountering an irregularity outside their domain of expertise can be just confidently told the irregularity is in fact a good thing and required for greater security of these highly sensitive processes. So, police or other government employed child welfare officers involved could be just told things are done this way for "added security"; they'd have little way to know that makes no sense and their usual habit would be to not discuss their cases so it would be unlikely to randomly come up in conversation with people who would find that problematic (so from their perspective they carried out their anti-fraud training, reported out an email discrepancy as is their training, their job is done on that).

To take targets of the scheme in foreign countries, for example, in getting an email error message of some kind (say you write back to a fraudulent email and it bounces) you could be phoned up and told any number of things that will in fact increase your confidence this error message represents more rather than less security: for example that precisely because it's highly sensitive child information that this easily triggers all sorts of security systems that then make these sorts of error messages so that we can be sure everything is working as intended, or then simply the system is down precisely because the information is so sensitive and everything is regularly audited! Which is an essentially unsolvable problem in security that all anti-fraud warnings can themselves be transformed by fraudsters into an advantage when dealing with untrained people (a la "we're special, this whole process is special, therefore special things happen in these special processes and you can trust our special knowledge to guide you through this special day, and then once you know what we know you'll be special too"). -

Child Trafficking Operation We Should All Do Something AboutIs there any actual evidence that any children have suffered because of what you explained? — Sir2u

First of all, compromising people's data is itself harmful, which then, in itself, causes the suffering of needing to worry about how one's data could be used for ill, once one is made aware of the data breach (as required under the GDPR). If you knew your ID and medical history was stolen that would cause suffering even if the data theft is never exploited to commit further crimes against you.

Of course, I am aware your meaning is suffering beyond compromising the data in itself, but I just want to fully clarify that violating people's privacy, sending their data to the some anonymous individual, is harmful and causes suffering in itself.

This totally illegal setup has been running for at least 7 years compromising hundreds, likely thousands of people's data, so really not good.

Further crimes against children by the network involving the above company have also been committed; however, I can't as easily report on confidential information of ongoing investigations and / or court cases.

The data breach part of this criminal network, however, is public information so anyone can re-publish it anywhere and draw attention to it.

As to what exactly these corporations and their criminal network are doing; I only have insight into a small part.

However, what I can say about the whole is that there is no legitimate business process that would result in this sort of information processing setup.

These are corporations that can only exist with boards of qualified corporate managers liable for what the corporation does.

Chapter 22: Damages

Section 1: Management’s liability for damages

A member of the board of directors, a member of the supervisory board and the managing director

is liable to compensate for any injury or damage that they have, in violation of the duty of care

referred to in chapter 1, section 8, while in office, intentionally or through negligence caused to

the company.

A member of the board of directors, a member of the supervisory board and the managing director

is likewise liable to compensate for any injury or damage that they have, by violating other

provisions of this Act or the articles of association, while in office, intentionally or through

negligence caused to the company, a shareholder or a third party.

If the injury or damage has been caused by violating this Act in some other manner than by

merely violating the principles referred to in chapter 1, or if the injury or damage has been caused

by violating the provisions of the articles of association, it is deemed to have been caused through

negligence, unless the person liable proves that they have acted with due care. The same

provision applies to injury or damage that has been caused by an act to the benefit of a related

party. (512/2019) — Limited Liability Companies Act

The last thing you want to do as a corporate manager is be involved in breaking the law, as that's always by definition intentional or negligent violation of your duty of care.

Violating the GDPR, even in subtle ways, has famously large consequences:

GDPR fines are administrative penalties that can be imposed on organizations that violate the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). These fines can be substantial, reaching up to 4% of a company's annual global turnover or €20 million, whichever is higher, for serious infringements. There are two tiers of fines, with the lower tier reaching up to 2% of annual revenue or €10 million.

Fines Structure:

Tier 1: Up to 2% of annual global turnover or €10 million, whichever is higher.

Tier 2: Up to 4% of annual global turnover or €20 million, whichever is higher. — Google GDPR fine summary

So any corporate manager, even more-so for something as serious as child welfare services, will know about the GDPR, informed by their lawyer or then it being constantly in the news. It was the absolute biggest news in EU corporate management for years, while it was debated, then passed, then the 2 years before coming into force and then the constant high-stakes legal cases resulting from the GDPR.

The first thing a corporate lawyer will tell you as a corporate member of the board is that implementing the GDPR for processing sensitive information requires expertise, having regular data audits, and no expert consultant or data auditor of any kind would not immediately identify all the serious security concerns in themselves of the data setup described in the OP as well as the long list of GDPR violations. This is really basic stuff.

But that's anyways how corporations work, that liability is transferred to qualified experts about as much as possible (so that the corporate managers cannot be held responsible for intentionally or negligently causing harm if they hired an expert to do it; an expert that then has insurance to cover their own negligent damages they might cause; why everything get's so expensive so quickly doing things the corporate way).

Ignorance is not a defence of corporate board responsibilities (such as to avoid being fined and / or sued under the GDPR) and it's simply not a hypothesis in this case worth entertaining.

Any legitimate corporation that is created to handle incredibly sensitive information will have at least 1 board member talk to their lawyer to go over the liability of the position which will result in immediately identifying handling the data as a major source of liability and disagreeing with a plan to just have somebody improvise the whole thing ... and also remain anonymous for the part where they improvise the email setup in the US.

A typical legitimate board member of this kind of corporation, if it were legitimate, would be very accomplished in their career, regularly consult with their own legal council about legal issues and take their responsibilities of due care seriously.

In addition to that, these corporations do government contracts to provide social services, so there would be another round of due diligence (and supposed to be regular review) from the government to get these contracts.

Point being, the hypothesis that a corporate board of child welfare company "accidentally" created a data processing setup that happens to be ideal for trafficking children is super amazingly implausible, and anyways is not a defence for the GDPR breaches as well as any damages that occur anywhere in the world. For, this setup makes the board members of these corporations not just liable to whoever's data they handled but also to anyone that is damaged by their child corporate welfare corporations having zero security measure implemented to avoid fraudulent emails representing their corporation.

"Limited Liability Companies Act" and "we didn't know about the GDPR" are not remotely plausible legal defences for corporate board members.

Therefore, we can be extremely confident this data processing setup was created and then shielded from scrutiny for the purposes of committing crimes (which there's specific evidence of more crimes than the criminally negligent data handling, but the above is another way to arrive at the same conclusion).

That it can be used to impersonate Finnish child welfare services and gain custody of and traffic children anywhere in the entire world is reason to disperse the notice as widely as possible (which if you live in a country, you can do; most countries have reporting channels, even anonymously, and just sending the notice could intercept a child being trafficked right now).

Such child abduction and trafficking crime can also be committed without even involving the corporations that created these vulnerabilities; any cyber criminal can discover these vulnerabilities and then exploit the with their criminal network.

Various documentaries have been made about similar practices taking place in the Netherlands, and political parties have tried to garner attention for it. Predictably, the political establishment isn't interested. I wonder why? — Tzeentch

In this case, that their email not even corresponding to their official domain and instead a 404 error page is red flag that anyone with anti-fraud training would discover pretty much immediately.

So we can be sure that government officials (police, prosecutors, judges, bureaucrats of various kinds) are involved in covering up this illegal operation, either because they are in on it or then manipulated by others who are in on it to ignore the red flags.

Doesn't need to be an intelligence operation though.

All I can say is that western intelligence agencies like the CIA, MI6 and Mossad have been linked at various points in time and on multiple occasions to global pedophile networks.

Too crazy to be true(?). — Tzeentch

Absolutely not too crazy to be true and we have abundant evidence this happens.

However, at the moment nothing requires involvement of intelligence agencies to explain. Just "regular crime" also happens of, for example, pedophiles making a child protection agency and then making money in organized crime and compromising public officials to shield their organizations from scrutiny; once enough public officials are compromised then other public officials that weren't involved in the original crime tend to conclude they need to help coverup the incredibly embarrassing truth in order to protect their own political future, so the coverup tends to sprawl out precisely due to it being uncovered if it has reached a critical mass. -

Child Trafficking Operation We Should All Do Something AboutTDLR: a Finnish corporation has setup their information processing system to be perfect for both stealing child information as well as being impersonated due to zero email security on their official domain. This combination of theft of real child protection cases (and all the kinds of paperwork you could possibly need) and allowing impersonation of their official domain, is ideal for abducting children from orphanages, foster organizations, even adoption, or straight abduction, and moving them around the world with fraudulent documents. Many targets would have little training and means in anti-fraud and would also "want to believe" children are going to a better life in Finland.

Children could be in transit using fraudulent documents and misrepresentation of these companies right now. Since the scheme can operate in any country in the world, the only way to protect children from this security vulnerability is to spread this information globally, starting for example with law enforcement and child protection reporting systems in every country.

So please if you live in a country report this information to at least the proper channels if not other concerned parties. The vulnerabilities and law breaking the above represents are immediately obvious to anyone familiar with the DNS system and the GDPR, however if you're wondering what an AI like ChatGPT thinks of all this, I've done that basic sanity check for you:

https://chatgpt.com/share/6883c7e7-8bc4-8013-a982-62af7cb9e4c1

Feel free to submit the same prompts to the AI of your choice.

ChatGPT's conclusion abot all this:

"""

Final Thoughts

This setup creates a perfect enabling environment for child trafficking, including:

Digital identity laundering

Institutional impersonation

High-value data extraction

Complete lack of traceability or lawful oversight

If even one actual communication involving children’s data or welfare occurred through this .com domain, it is grounds for:

Immediate investigation by Finnish and EU authorities

Suspension or criminal scrutiny of anyone authorizing or tolerating the setup

"""

The base DNS records (DNS standing for Domain Name System) can be sourced directly from ICANN (the organization in charge of these records so the internet and world wide web functions as it does):

https://lookup.icann.org/en/lookup

Email server records, called "MX records" can be sourced from google's tool:

https://toolbox.googleapps.com/apps/dig/

Which will report "record not found" when clicking on MX.

But there's a bunch of tools available to make these inspections.

The errors produced by another popular tool https://mxtoolbox.com/emailhealth/ summarize the complete absence of any email security whatsoever:

Category Host Result Status

Problem mx uomasosiaalipalvelut.fi DNS Record not found Status

Problem mx uomasosiaalipalvelut.fi No DMARC Record found Status

Problem mx uomasosiaalipalvelut.fi DMARC Quarantine/Reject policy not enabled Status

Problem dmarc uomasosiaalipalvelut.fi No DMARC Record found Status

Problem spf uomasosiaalipalvelut.fi No SPF Record found Status

Problem spf uomasosiaalipalvelut.fi No DMARC Record found Status

Problem spf uomasosiaalipalvelut.fi DMARC Quarantine/Reject policy not enabled -

Differences/similarities between marxism and anarchism?↪boethius I have begun reading some of the classic Marx/Engels texts and what I am finding is that they assume a high level of knowledge on the reader's part about capitalist economics. — unimportant

Definitely things will be a lot clearer of what people are even talking about with reading the classic texts in a discipline. Highly recommended.

Partly Marx is addressing himself to other intellectuals who he assumes is familiar with all the texts he's familiar with, such as Ricardo and Hegel and he's using references and language and conceptual frameworks that Western intellectuals at the time would be familiar with; and partly there's a lot of words and concepts that everyone is familiar with at that time but now require more erudite historical knowledge to fully understand.

For example, everyone, for all intents and purposes, at the time Marx is writing are familiar with Lords and the bourgeoisie. The class distinctions were super obvious and people were very concerned with being identified with their class and their subgroup within their class.

Why analysts today still use the word bourgeoisie is first there's no good modern counter-part, as to say "upper class" is to include also aristocrats, but the whole point of the bourgeoisie is that they are rich but no aristocrats. So in modern language they are the 1% who aren't still actual kings and lords. King Charle's is part of the 1% but not bourgeoisie, likewise the pope is reasonable to say is part of the 1% but is not bourgeoisie.

Bourgeoisie also has more reference than just wealth (without being also still feudal), but there's a whole culture and world view that develops along with it: clothes, mannerisms, opinions, history, myth and so on; most importantly an ideology that optimizes their dominance that they can, through their dominance, push on the rest of the world; when very different cultures start to look "Western" what those cultural elements, world view and opinions actually are and come from are the Western bourgeoisie culture. There's obvious things like clothes and architecture, but more importantly is the way of thinking such as wealth always being caused by hard work (why wealth is deserved, and why the bourgeoisie should be in charge and not aristocrats who did not "earn their wealth"; i.e. wealth is always deserved except if you're an aristocrat, but even then only before the emergence of capitalism as since wealth is always deserved existing aristocrats, such as King Charles, "earn" their wealth through the hard work they do bringing in tourism, perfectly honest well deserved wealth of a modern hard working enterprising modern king; so that kind of obsession proving an anachronistic king in the contemporary age is economically justified, rather than even consider any theory of governance and justice and so on, is archetypical bourgeoisie sensibilities; the question of the effect of having a king on governance would not even occur in bourgeoisie culture as everything that exists under capitalism has an economic explanation and everything with an economic explanation is justified, except when they disagree of course, then it's a case of "it may work for them over there, but it wouldn't work for us here and there's an economic explanation, and thus justification, for both cases"). -

How can I achieve these 14 worldwide objectives?

One pretty good heuristic for systemic corruption in an organization (private or government) is increase in debt levels.

Corrupt people do not think about the future and simply takin on debt is the easiest way to satisfy all corrupt stakeholders and avoid inter-corrupt competition.

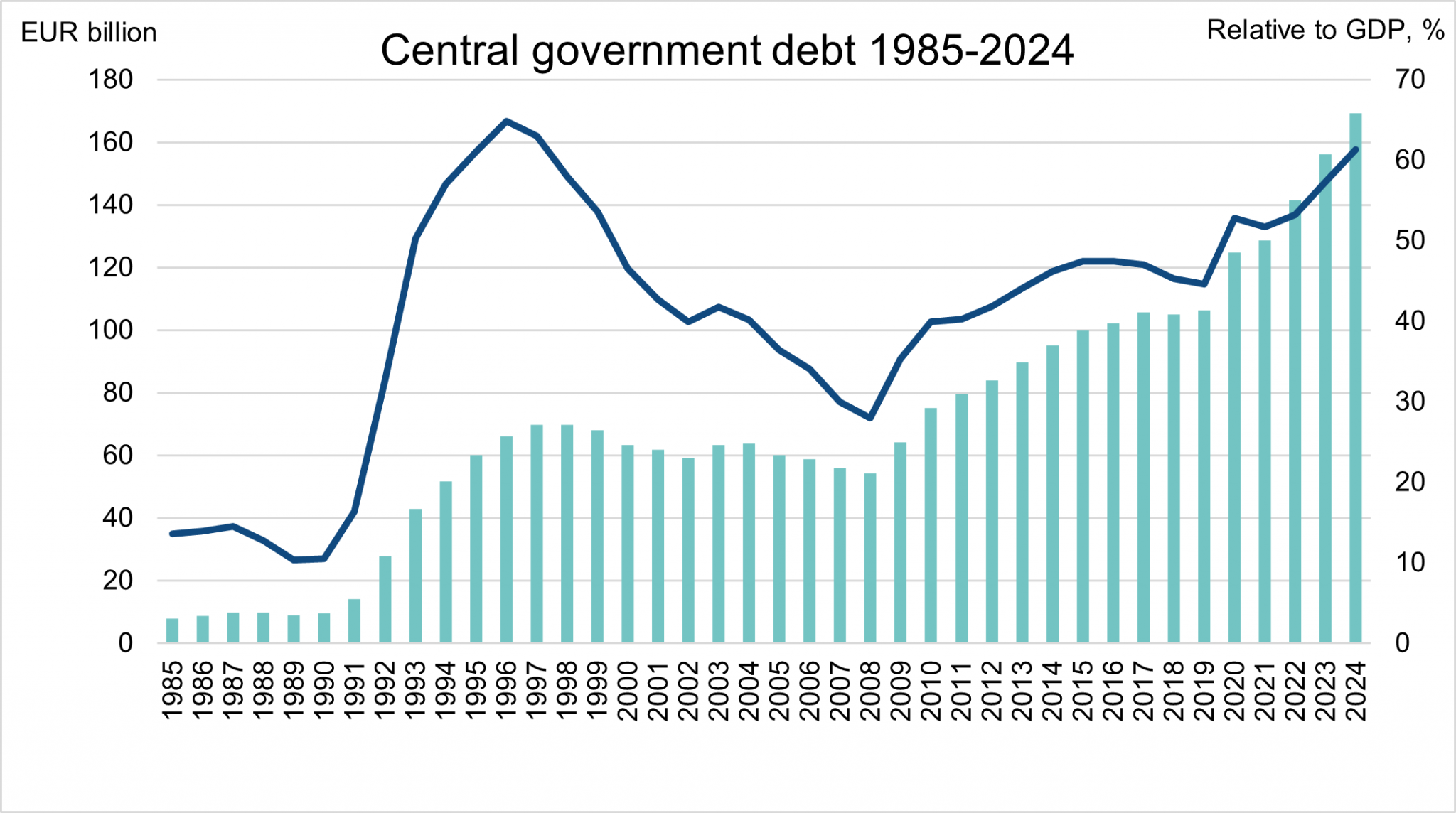

Consider Finland's national debt growth (Directly from the Finnish government debt page):

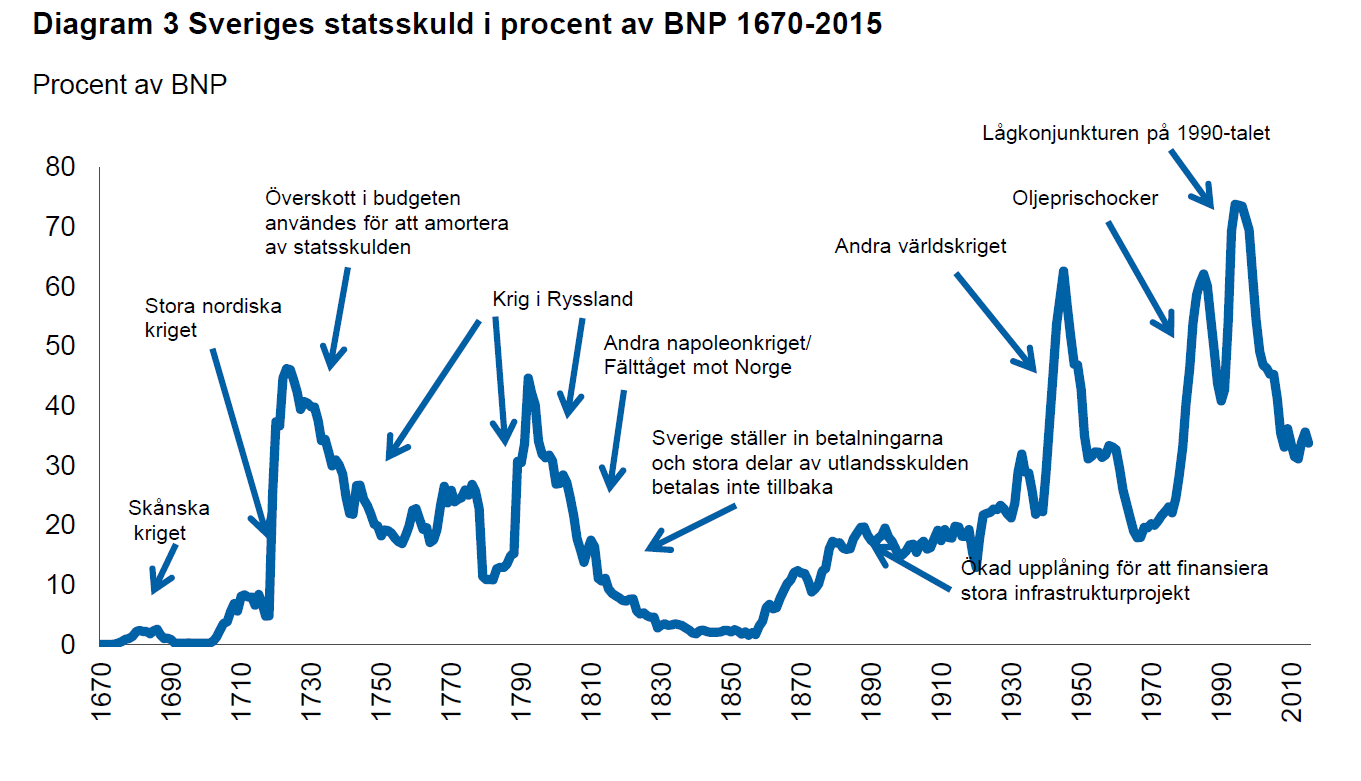

Compared to Finland's most direct peer that is Sweden (also direct from their government page on national debt):

Notably, Sweden is a lot less racist than Finland, so this difference in debt outcomes is compatible with racism being a core driver of law-enforcement and political corruption.

Of course increases in debt is not only caused by corruption, so there would be a lot to discuss, but it is one feature shared by all countries with corruption problems that debt increases. Corrupt people generally don't moonlight as brilliant financial planners. -

How can I achieve these 14 worldwide objectives?

Just to add a couple of key points.

The system of corruption is not planned in any coherent sense, but it's mostly reactive. There's this large illicit capital base that invests in actions (including careers of key people) to both avoid accountability and keeping the money flowing. The people who control this capital are not necessary allies but their interests are aligned in making sure money is easy to launder and there's never any real investigation into how billions of dollars are moved through the financial and corporate system without almost any being found.

So, when there's a threat the corrupt network of people either purposefully benefitting (think attorney who's business is washing money) or then people who are compromised, one way or another, and realize any actual impartial investigation would reveal their part in the corruption as well.

With time either organized crime would be mostly "dealt with" and go away or then all threats to illicit capital will be removed. Once you get rid of one nuisance prosecutor or judge it's even easier to ensure they aren't replaced with anyone more of a nuisance; indeed, most people are cowards anyways and won't "make waves" so just the process of getting rid of the nuisances will result in a compliant system anyways.

The system is not stable with large illicit funds.

It's also immensely profitable to corrupt the government ... it's not even really a tax on illicit capital, as once the government is compromised to ensure the safety of illicit cash flows, the same system of corruption can be used to embezzle government funds.

Even better, a corrupt government can be manipulated into war, which is the most profitable conditions for organized crime: allowing vulnerable children without fathers to be even more easily kidnapped and sold into the child-rape industry as well as endless cash and weapon systems to "go missing" in the fog of war.I

It's simply commonly accepted fact that half the money sent to Ukraine is stolen and laundered as well as a large proportion of the arms sent to Ukraine. When the Western media deals with this issue it's simply shrugged off as a cost of doing business if we want our war.

The Ukraine war is both one of the most profitable events in the history of organized crime as well as supercharging corruption and organized crime in Europe.

From the outset European governments know Ukraine is going to lose (that the West is not going to risk escalation with Russia, so the only available policy is prop up Ukraine until is loses), knows propping up Ukraine and encouraging their no-diplomacy position will result in hundreds of thousands dead, know sending money and arms to the most corrupt country in Europe and number 1 in the world in illegal arms trafficking even before the war is just pouring tax payer wealth directly into the most ruthless organized crime networks on the planet, know there will child abductions and organ harvesting on a large scale, knows literal organized crime Nazi groups need to be armed and financed in order to prop up Zelensky, and that all this is at the immense harm to European economies.

So what's a better explanation? That policies ideal for organized crime and that don't accomplish anything else except politicians weakening their own countries and harming their own population, are due to politicians just suddenly having the statecraft acumen of toddlers and "Putin meanie" is the absolute extent of their diplomatic skill now, or that these politicians work in the interest of organized crime, and none of the money sent to Ukraine and then laundered is found because law enforcement also works for organized crime?

Point being, the evidence for regulatory capture by organized crime is extremely obvious and abundant and offers the best explanatory theory of the policies we see as well as what we don't see (it's simply admitted as a "necessary evil" that a lot, if not most, of the money sent to Ukraine will be stolen by Ukrainian elites because they are obviously super corrupt ... so why not any policies to try to mitigate that? Or then mitigate the weapon being stolen and sold on the black market? Or the to mitigate the child-rape industry? Etc.). -

How can I achieve these 14 worldwide objectives?↪boethius That's so disturbing and horrific. — Truth Seeker

It is extremely disturbing, and unfortunately people don't want to see the evidence for it.

One additional note that I forgot to mention is that our Western political systems were intentionally designed to ensure the corrupting influence of the wealthy elite.

The wealthy elites who designed liberal democracies didn't want the monarchies and feudal system of aristocratic rights (that they no longer saw a reason for and just stood in the way of business) and to overthrow feudalism they needed the support of the people and revolution in the name of the people ... but they didn't exactly want the common people to have any actual power.

Liberal democracies therefore were designed by wealthy elites to serve the interests of wealthy elites, but they of course viewed themselves as honourable and rational and that they would "do good" with power over governance (same exact thing kings and aristocrats believed before), but of course a system in which wealth has the most power is naturally vulnerable to the power of illicit wealth.

Illicit wealth also naturally corrupts the entire business community without really needing "to do" much actual corruption other than invest illicit money that's been cleaned and have your people sit on corporate boards as part of the investment package. Most business people are naturally easily corrupted by simply offering them what they want.

So there's lots of vectors of corruption, both big and small, and the best way to visualize it as all summing to a sort of corrupt pressure that reaches a tipping point and the whole system switches over into a corrupt mode in which even the corruption that is uncovered there is no accountability, after which it's a point of essentially no return until the system collapses. -

How can I achieve these 14 worldwide objectives?Why is there so much corruption in Finland, despite its high HDI? — Truth Seeker

I'll write a fuller account later, but the short version is the combination of several factors.

The sort of "zeroth factor" is the context of the global narcotics trade, and now also human and arms trafficking trade, which in turn mostly reduces to racism.