Comments

-

Ukraine CrisisEspecially the Americans. — Olivier5

Ok great, so what's you plan of action?

We condemn the Americans until they put down their guns?

... But if they put down their arms, how do they give arms to the Ukrainians if they've given up those old barbaric ways?

And, if Ukrainians are just and the just thing to do is to put down arms, why aren't you calling for the Ukrainians to put down their arms and do the right and ideal thing? -

Ukraine CrisisWhat would be the point, pray tell? — Olivier5

It's your standard: pick a side, cheerlead one and condemn the other.

And not just your standard you set for yourself, but you assume others have do anyways, just not honest about it: as any criticism of one side is doing what you prescribe for yourself.

Maybe, us serial misunderstandererers could use a few other examples to see how your method works and the righteous values it's based on. -

Ukraine CrisisNow you're talking. So ideally the Russians should lay down their arms and turn Russia into a vibrant democracy.

Glad we agree with that. — Olivier5

But, so too the Americans, you agree with that?

And, maybe bother to actually read my posts, as I've mentioned this several times. -

Ukraine CrisisI actually disagree with that. I think it should be divided. — Olivier5

The point is ... how will it change?

Ukrainians take back part of Crimea and if Russians don't accept that, they roll to Moscow? -

Ukraine CrisisI do. Why don't you discuss them, if they are so important to you? — Olivier5

Go ahead, enlighten us with who's right and who's wrong in every contemporary war.

Is that why you have to cheerlead the Russian side, a soddin' dictatorship, bombing innocent people? Because there are other wars? — Olivier5

I'm not cheerleading the Russians ... and no one in the EU is sending arms to the Russians.

The Russians can fight their own war, that seems clear, and what happens on social media doesn't affect their decision to do so.

You seem to think that "defeating" the Russians on social media will somehow defeat them in the field.

This is not the case. The war will not be fought in the sub-reddit's and the tweeting and the facebooking and in the forums, it's fought in the real world with real weapons and the affect of Western social media isn't very strong.

Pointing out the Ukrainians have no way of defeating the Russians, and therefore the war can only end with either the Ukrainians losing militarily or a negotiated settlement, is simply pointing out a fact, it's not cheerleading the Russians.

There is nothing that can be said on Western Social media that will change the Russian's policy and requirement of concessions for ending the war.

So, the choice are accept some concessions ... or fight to win.

If you have some plan that will have Ukrainians storming Moscow in any reasonable amount of time, then you do the Ukrainians a great disservice by placing your efforts here rather than going and telling them what to do. -

Ukraine CrisisOh you know of things that are morally right? That wasn't apparent so far. — Olivier5

It's far easier to know what are good things, and a good life, and the difference between pain and suffering, love and hate, peace and war, than condemn another as having nothing of value and doing nothing but evil.

Mostly, people agree on what are good things and would prefer love and peace.

The question is how to get there.

So what would be the ideal outcome of this war, according to you? — Olivier5

The war has already started. Assigning blame to who is most morally responsible for the war, can be easily debated many, many years, to get into every moral and political nuance, after the war is ended.

The ideal outcome of the war would be what minimizes suffering in the short term and creates a lasting peace.

No one disagrees that Dombas is filled with ethnic Russians that want to separate from a Ethno-Ukrainian nationalst state, and that they have done so and that there is no way for Ukraine to "defeat them" militarily as Russia won't allow it.

No one disagrees that Crimea is de facto now part of Russia and that won't change.

No one except neo-Nazi's and their sympathizers agrees that neo-Nazi's are a bad thing and policies should be agreed on by NATO, the EU, Russia and Ukraine on how to dismantle neo-Nazi organizations.

Of course, the "ideal" end to the war would be everyone in the whole world, including Americans and gangs and the mafia, laying down their arms and start talking things out in a bottom up participatory direct democracy without nation-states in any similar sense as they exist now.

However, if that "ideal" has no practical way to bring about as an ending for the war, then recognizing the right of "self determination" of the Dombas and Crimea, and that they are de facto in Russian control now anyways without any means of changing that, is a more reasonable outcome than fighting for ... what? To achieve what militarily? -

Ukraine Crisis↪boethius Empty words. Go bomb an Ukrainian if you want to be useful. — Olivier5

I don't have a problem with Ukrainians fighting, it's their choice.

I have a problem with neo-Nazi's, that's for sure; but I'm told that's a small part and the enemy of your enemy is your friend.

There is more than one war happening in the world at the moment.

Do you even know about the others, much less have picked one side and condemned the other?

Or do those people and whatever they're fighting about not matter in the slightest?

If so, why would you expect otherwise vis-a-vis Ukraine?

A few questions for you. -

Ukraine Crisisboethius disagrees with that. — Olivier5

I said I haven't analysed it yet.

However, I would agree with @Benkei that it's morally wrong in a very large sense of morality. In my view, "morally right" would be turning Russia into an anarchist direct democracy.

Condemnation is a much stronger statement, such as "true evil".

There is also a middle area of whether Russia's Imperial war is "worse" than the other great power's Imperial wars.

For example, all the great powers owe their existence to Imperial wars, but we view the Nazi's Imperial war as much worse in comparison.

We (the West) condemn the Nazi's for WWII ... but we don't have similar condemnation for US in Vietnam or Iraq or the French in Algeria (and pre-WWII Imperial conquests are simply off limits for moral analysis; "different time" kind of thing, I'm sure you understand). -

Ukraine CrisisYou're more submissive than most people, I guess. — Olivier5

They can come and fight if they care, that would be welcome ... social media isn't "support".

It's hypocrisy.

A war should never be a charity case. -

Ukraine CrisisAnd I know you can do better so I think that this means you're truly worried about an escalation including Finland. — Benkei

An escalation that would only happen due to Finland rushing ahead to join NATO ... but not actually be in NATO.

Otherwise, Russia would have already attacked Finland if that was "the plan all along" ... and, since that wasn't the plan as it hasn't happened, but the status quo has been acceptable to Russia, then if the status quo was maintained ... certainly Russia wouldn't attack Finland after being weakened by NATO in Ukraine.

However, if the exact same warning to Ukraine are sincere to Finland and Sweden, then tactical nuclear weapons would be dropped until they, too, accept neutrality ... the exact same status quo as before baiting Russia into dropping tactical nuclear weapons.

Which, may explain, rather than Finland's millennial Prime Minister, who is completely clueless about geopolitics, it is Finland's older president with far longer experience dealing with the Russians and talking with Putin, all of a sudden represents Finland on the international stage (after not a single woke article being written about him and Finland's wonderful young and woman led government ... where are those young woman leaders now?) and ... is one EU leader not just fiercely condemning Putin and calling him a madman but saying things like "the situation is complex". -

Ukraine CrisisIf Russia -- or anyone else for that matter -- was to attack your country, would you see the foreigners supporting your country as more disgusting than the army destroying your cities? — Olivier5

Yes, if we had no chance of gaining anything militarily and we were just being used as pawns to bleed the Russians, setup before hand to bait the Russians into a war, genuinely believing those "foreigners" supporting us would come to our aid in some concrete "friendly ally" sense.

Being manipulated is far more disgusting than dealing with someone who does exactly what they say they're going to do, even. Being manipulated by your "friends" is a far worse taste than having some sort of clear foe.

I would also not expect anyone to give us free arms, and the honorable requirement to buy our own arms to fight our own wars, and perhaps take on massive debts to do that, would be part of the equation of whether fighting was worthwhile and what sort of deal (which would be the only possible positive outcome of the war ... as we're not about to march to Moscow and actually "beat the Russians" in any scenario whatsoever) would be a reasonable deal to end the war.

You fail to understand that there is no winning in this sort of situation.

The only possible end to this kind of war is negotiated settlement or then complete defeat in the field.

Even if the Ukrainians routed the Russians and they pulled back to the Russian border ... Ukrainians have not "defeated" the Russians, they would still be there, the war would still be ongoing, the Russians would come-up with some other strategy, maybe just drop a few tactical nukes and call it a day.

You don't win a war by not-losing for now, you need to actually go and defeat the enemy in their own homeland, defending their own soil, hoist your flag in their capital, put your feet up in the enemies government offices and drive down their boulevards smoking their cigars.

There is this righteous WWII narrative ... but no feasible WWII pathway to victory. -

Ukraine CrisisYou have not answered the question. You're good at that, BTW, not answering questions. — Olivier5

Which question? I literally answered "yes" to your last question.

On the "gotcha" of morally condemning the Russians, I simply do not make moral condemnations without the same analysis I would ask people wanting to condemn me to make, and, in particular, after I have provided my own defense of myself as well, to my own satisfaction; analysis of the Russians I have not yet done, as it's mostly irrelevant to the current situation and actually saving a single life, helping a single child.

I view the purpose of analysis to make decisions, not morally condemn.

What decisions matter to me in this situation that I can affect: the policies of my own country and political block.

What are those decisions:

A. Go to war on the assumption of Ukrainian just cause ... well, nearly the entire country and political block believes in Ukrainian's just cause yet we are not going to put our boots where our mouths are.

B. Send arms to Ukraine in the hopes they fight our righteous battle "for the free world" for us and win.

C. Pump arms into Ukraine, not for the purposes of option B, but to ensure an endless insurgency that bleeds the Russians at Ukraine's expense ... Wooooweee!!!!

D. Use diplomatic leverage to protect civilians as much as possible and work on a diplomatic end to the war.

I, personally, don't know how option B is going to work, so, if it can't work, then it's foolhardy and gets a lot of Ukrainians killed for no better a military outcome.

I don't see how C, "give the Russian's their Afghanistan, with love from NATO" actually helps Ukrainians. I honestly don't think Afghanistan is better off after NATO gave NATO its own literal Afghanistan. Which is a bizarre part of that argument, as it's framed like "tit for tat" to the Russians ... as payback for something we did to ourselves ... and not to forget the Afghanis.

So, it seems to me D is the best choice.

Do Ukrainians "have a right" to defend their country: Yes, I would agree, I claim the same right for my own country.

However, simply because something is a right does not mean it's the best choice. I have a right to do a lot of things that are not in my, nor anyone's, interest to do.

Time will tell. -

Ukraine CrisisYou would do so? Like, if Russia was to attack your country you mean? — Olivier5

Yes.

The difference is that there would be a credible plan, equipment, bunkers and escalation of mobilization in lockstep with Russian force buildup (the whole point of conscripts against a larger country with a larger military that would obviously win in a total war situation, exceed the tolerance for losses and, through diplomacy, remove any reason to have a total war fight to the death situation, and, therefore, not be an "easy target" for a standing army in a non-total war situation).

And the whole point of such a posture is not to "wait for the day" to finally fight the Russians to the death, but demonstrate a respectful realism, and, instead of fighting words, offer friendship and good faith collaboration and grateful burning of Russian gas (that literally heats my home right now).

The point of actually fighting, if it came to that as the situation got out of control due to reckless civilian leadership (otherwise we'd be fighting the Russians right now if they were just that bad and no way to work with them), is to reach a settlement as quickly as possible, in a good negotiating position of having a credible military plan that would require total war to defeat.

Ukraine is in total war, but Russia is not in total war. However, Ukraine is in a severe geographical disadvantage.

There are many countries that do not exist for military reasons, but due to their existing being convenient for the far greater powers that surround them for one reason or another.

Monaco doesn't exist because it can fight the French, but because the French allow Monaco to exist, and you won't hear Monaco picking a fight with the French but rather diplomacy is used to maintain the status quo and continuously convince the French Monaco as it is now is better for them. This is perhaps the most extreme example, but many countries have no military option against a more powerful neighbor. No one claims Canada or Mexico would win in some total war situation with the United States. -

Ukraine CrisisTargeting hospitals, shelling of cities randomnly is a warcrime. — ssu

There are certainly war crimes, likely Azov battalion not letting people leave Mariupol, which may or may not come out as undisputed fact after the war, is also a war crime.

Extrajudicial killing of alleged "saboteurs" would also be a war crime if they weren't actually sabotaging anything.

But, if the world is suddenly so interested in war crimes, we should probably go in chronological order and start with indiscriminate bombing of Cambodians and use of agent orange (a chemical weapon that causes neurological damages), and targeting Iraqi civilian infrastructure ... and torturing people; certainly all those documented things can be wrapped up in a day.

Oh, sorry, my bad, US doesn't recognize the "war crimes court," as it's totally irrelevant and means nothing, and I'm sure US officials making use of that institution now when it suits their purposes is just "a mistake".

However, as @Benkei has pointed out, you need an actual trial to convict someone of a war crime ... a trial where they present their own defense and evidence.

Russia has plenty of video too, and one thing Russia doesn't like to do is reveal it's operational capacity and intelligence methods during an operation and one thing it does like to do is hold onto evidence and prove things wrong later. The more people repeat a claim and for longer, the more credibility is lost when the claim is disproved.

Of course, Western media will simply ignore that, but it means something to other countries being proven to be an unambiguous shit talker and liar.

... And if you hand out weapons to hundreds of thousands of civilians, to walk around feeling "safer" clutching their riffle, you also make hundreds of thousands of legitimate military targets. -

Ukraine CrisisThe small Baltic countries surely hope they aren't expendable. — ssu

Exactly.

People compare Russia to Hitler ... but Hitler didn't have Nuclear weapons, there was no threat of world obliteration if we went and fought Hitler.

Putin could be far, far, far more evil than he is now, and far more evil than Hitler ... and there's nothing much we can do about it through warfare ... why no Western country has sent any troops to Ukraine no matter the level of moral condemnation of Russia and praise of Ukraine as a bastion of freedom.

We can try to build a more peaceful world. That is our only practical choice.

Ukraine is completely expendable to NATO.

Finland was Gondor to Sweden's shire, but had the geography to hold out. -

Ukraine CrisisAre you Russian? — Olivier5

I am not Russian, I have in fact trained to fight Russians and would do so.

It's precisely because I have actually trained to fight against the kind of warfare Russia brings to the table, that I do not see how Ukraine can achieve any military victory in the field ... which we all agree it can't.

It needed NATO to supply its best and most sophisticated handheld weapons and for NATO and the EU to sanction Russia to put pressure at home.

At the same time the war is used as "proof" other NATO nations haven't been spending enough on their "own defense" ... yet no one holds Ukraine to the same standard, they get a free stuff.

A free pass from NATO, a doctrine NATO constantly rebukes, and they aren't even in NATO.

Zelensky literally threatened Russia with World War III yesterday ... is that a "Ukraine threat" or a "NATO threat"?

Guaranteed, if Ukraine didn't think it had free access to NATO resources and intelligence to fight the Russians, and would continue to have free access up to and including a NATO no-fly-zone, if not boots on the ground, then Ukraine would have had a different policy with Russia.

But when NATO reaches out it's hand to come along as a friend ... maybe is a false sense of security if NATO doesn't show up to the party to fight "the bully" you've been talking up a storm about finally teaching a lesson. -

Ukraine CrisisSo what is the MOST disgusting of the two: to aggress your neighbour in such a war, or to cheerlead the victims trying to defend themselves? — Olivier5

Cheerleading others to fight for your own virtue-signalling on social media is far more disgusting.

Actually fighting a war, at least there's skin in the game."Courage of your convictions" as they say in French.

We say all our wars are just wars that were needed for our current institutions and "nations" to exist, and, just-so-happens, no war that ever inconvenienced us was justified. Is this really statistically credible?

And, who's the aggressor? Ukraine has been shelling Russian citizens for 8 years.

As the videos I posted (spanning several years since 2014) describe it: a "war".

A war, neo-Nazi's are on video crediting themselves as starting and also explicitly stating their objective for a war with Russia and who are most active in both fighting and promoting the war with Russians since 2014. -

Ukraine CrisisJust to be clear, do you find Western sympathies for the Ukrainian side, their occasional cheerleading and their arm support more disgusting than the Russian aggression and indiscriminate bombing of Ukraine, or less disgusting? — Olivier5

Russians aren't cheerleading a war, they are fighting a war.

They are fighting a war their political representatives have told everyone they would fight in these circumstances for several decades.

They are at least not hypocrites.

With my limited understanding I can only judge contradictions ... to be contradictions, and thus wrong according to the self proposed standards.

Absolute truth and absolute right and wrong, I honestly can't really judge.

For example, I've pointed out that the moral and political question of "how many neo-Nazi's with power is too many neo-Nazi's with too much power and too much power". We would need to actually answer this question to start judging the Russian's justifications for the war.

Furthermore, the West doesn't take nuclear tensions and nuclear bating seriously (otherwise we wouldn't have pushed missile bases closer to Russia in order to "defend" ourselves in the middle-east) but maybe the Kremlin does and they see not-acting now as increasing the likelihood of a real nuclear exchange in the future.

The West basically assumes that the Kremlin is some sort of circus blundering around, knocking back shots of vodka and determining policy by throwing darts at a word-wall from a unicycle.

What if they are more serious thinkers than that? See themselves as being in control of nuclear weapons that could end the world and take that responsibility seriously and see NATO as an immature school boy skipping merrily into nuclear oblivion, that needs to be taught a lesson.

... Which ... as far as I can tell, NATO has learned that lesson and finally become a "NATO man".

History is made by people who don't hesitate to sacrifice a million souls to save 2 million. We praise those that won our wars and condemn those that lost against us.

This war is the lessor of two evils when it comes to Nuclear war. A classic MAD standoff is, in some respects, more stable than NATO just baiting Russia into nuclear tensions and war ... because it's fun?

Moral condemnation requires analyzing all these things to be sure the condemnation is justified.

Why do I say so? Because I would wish for myself a thorough analysis before I am condemned.

What does not take much analysis is to conclude that ending the war through talking, in some workable solution for everyone, is better than continued warfare.

If Zelensky wins, ok, another intrepid and committed war leader willing to sacrifice any number of his own citizens for glorious victory.

If Zelensky eventually accepts terms that were on offer before and at the start of the war, then it's difficult to justify the lives lost. -

Ukraine CrisisOh. So you think the "denazification" of Ukraine will be so easy at the end of a rifle? — ssu

The Kremlin does not care much about neo-Nazi's in themselves, they care about institutions that can threaten them ... and if those are explicitly or mixed up with neo-Nazi's it just so happens to be easy to explain to a Russian the reason to destroy those institutions.

That Westerners ignore the issue, or even cheer on the Azov brigade to "hold out" in Mariupol and never surrender, doesn't matter to nearly every Russian that is alive today.

Whopee! That sounds like fun. All this for a land bridge!!! :roll: — ssu

If Russians generally support the war, which they seem to do, and the objectives of the war are attained, then it's easy to declare victory. Russians were genuinely concerned about Crimea being caught off from it's water source and were genuinely concerned about over 10 000 Russian citizens (all the separatists got Russian citizenship) dying in Ukrainian shelling since 2014.

Of course. Those tens of thousands of anti-tank weapons being pushed in Ukraine won't mean a thing. Perhaps those 20 000 or so volunteers will come back after they have had an exiting weekend too. — ssu

In an occupation of the whole country, it would be disastrous, but if Russia simply pushes out the Dombas front (and so the territory is occupied by Dombas separatists and not insurgents) and just removes everyone from their land bridge, then, as we've discussed, ATGM's are so useful in assaulting a buildup front.

20 000 foreign fighters aren't a game changer, and will obviously mostly leave, if they don't die, once there's no military objectives that can possibly be achieved.

You also skip over the moral of these foreign fighters once in Ukraine as well as the moral of the Ukrainian forces. "Not letting men leave" from 18 to 60, was spun in Western media as "look at those heroes go valiantly back to the front! Such bravery" ... but I'm pretty sure those men wanting to leave don't feel the same way.

All that for half a billion! Let's now compare this to what is the aid for Ukraine. Before the war started, the situation was the following:

"Overall, the U.S. has provided $650 million in defense equipment and services to Ukraine in the past year — the most it has ever given that country, according to the State Department."

Then afterwards:

"The White House also said Washington is “helping the Ukrainians acquire additional, longer-range” air-defence systems, but did not provide further details.

"The most recent package brings the total US security aid to Ukraine announced since the Russian invasion began to $1bn. The Biden administration previously approved another $1bn in aid before the invasion began."

And the war has been on for less than a month. — ssu

If it's a question of money ... Russia has more than a billion to spend.

Have you been drinking or what? — ssu

As I've said many times, maybe there's some brilliant surprise counter offensive that routs the Russian army and the run back tail between their legs. I just don't see what it would be (but that's what a surprise means).

As it stands, Russia has militarily nearly achieved the key objectives it set out to achieve: destroy Ukrainian military capacity (1 billion doesn't magically repair all those bases and depots, nor bring back professional soldiers back from the dead), secure the Dombas, and secure a land bridge.

Although the Dombas front hasn't moved much (where the Ukrainians have been digging in for 8 years), it's logistical supply chain has been targeted by bombing and cruise missiles, and the front itself has been heavily bombarded since the start of the war. Simply because that line hasn't moved much yet, doesn't mean it's in the same condition as a month ago.

It's farthest from Western resupply and closest to Russian artillery and bombs, so I just can't see, from military strategy point of view, that it's possible to hold.

In addition, the Dombas line needs to deal with Dombas separatists who have extreme motivation to fight (get the war over with rather than continue the 8 years of shelling and accumulated deaths ... as well as finally the entire Russian army behind their movement); these aren't hapless Russian conscripts lost in the Ukrainian country side.

Now, if Ukraine pulls a win somehow, ok, Zelensky had speeches and the military strategy to back it up.

If not, and Zelensky accepts terms Putin offered at the start of the conflict, my prediction is that he will fall from grace in the eyes of Ukrainians and the world.

People like winners. Zelensky is winning on social media, which is usually enough for every other kind of dialogue, so people like him because they see he's winning. -

Ukraine CrisisMoi? I have been accused of war cheerleading here more often than I care to count. The words roll off the tongue of your buddies day and night. And when for the first time I return them the compliment, I'm the one to blame?

That's called a double standard. — Olivier5

If you support the Ukrainian war effort ... but aren't in Ukraine fighting the war, nor even proposing troops from your own country go and fight with Ukrainians to at least vicariously live through your own soldiers' bravery ... then you are simply cheerleading other people fight a war that you're not willing to fight personally nor you're own government.

If you're in Ukraine fighting, then maybe that serves a military or political objective, maybe not, we shall certainly find out.

If you're arguing with people who's position is to put pressure on their own governments (who's policy they can most affect and are most morally responsible for affecting) and super-political-block, the EU, to use their soft power to work on diplomatic solutions rather than pour in arms ... precisely because we aren't about to send any troops and sending arms instead is a cowards cop out, that is the opposite of cheerleading a war.

None of us are cheerleading Russia to level Ukrainian cities to the ground, we are appalled it is happening and there are certainly diplomatic solutions given the immense leverage NATO and the EU has in the situation.

The US didn't just send arms to Britain to fight the NAZI's and call that "fighting a righteous cause" ... yet somehow social media posts are a moral substitute to taking any actual risk for one's pet cause.

This is literally the first time in history where selling and gifting arms is a pure act of altruism and the bravest thing freedom lovers could possibly do, or ever have done, amen. -

Ukraine Crisis

Like what?

Maybe provide at least some examples of what's misunderstood.

How are you sure you're not serial misunderstanding your understanding of serial misunderstanderers? -

Ukraine CrisisOh sure, how the war is going it surely won't be an Afghanistan for Russia. It will be much, much worse. — ssu

This isn't an "Afghanistan".

If the war is quick, it may cost lives but doesn't slowly ground down morale and domestic support over time.

Right now Putin's popularity has increased and Russian's support the war, so the war need only be ended within this window of popularity.

Putin has not made promises that can't be kept: like "democratize" Ukraine at the end of a rifle.

Putin has already achieved the land bridge to Crimea and if the Dombas front collapses and territory pushes out regions border, Putin can just sit on this territory and shell to oblivion anything that approaches while continuing to strike command and control and logistics infrastructure.

The entire Russian army can be consolidated to the lines around what Putin claims to want, maybe around Kiev as well to keep pressure on the capital ... and then just wait for his terms, that have not changed since the beginning of the war, to be accepted.

What the Kremlin has learned from previous episodes, is that Western "Unity" is only ever short lived and only ever exists on social media and not in any tangible form. Winning the social media culture war ... doesn't win a real war, is the main lesson to be drawn from Syria.

If a military status quo settles in with the Russian army mostly just sitting on the territory it wants to keep, then the EU is going to start to wonder what it's going to do with all the refugees and disputes will break out about that ... gonna look really attractive the idea of the war actually ending so Ukrainians can go back to Ukraine (which, for now, most want to do ... but if the war goes on for any amount of time, most will start making new lives and will have nothing to go back to).

As far as I can tell, the only reason Zelensky didn't accept Russia's terms in the first phase of the war, when it was easy to do:

1. Neo-Nazi's made it clear they would kill him if he did.

2. He genuinely believed in the power of acting to conjure up a NATO no-fly zone a la Churchillian Dumbledore.

3. He got so many views ... no one in show business can walk away from

However, the difference with Churchill is that he also had a feasible military strategy and feasible political strategy of getting US into the war and a pathway to military victory based on military experience (indeed, experience largely considered to be failures, and maybe a little dabbling in genocide, but potentially kind of experience that breeds the requisite caution). Also a little foot note: Britain was still head of a large empire from which to draw resources to take on the new Nazi empire, with the Nazi-Soviet alliance tenuously paranoid at best.

The modern conception that Churchill's speech somehow caused, in itself, the defeat of the Nazi's without any sort of credible plan ... is possibly misguided.

Politicians love Zelensky because social media loves Zelensky and his views of photo-ops are their views of photo-ops and the whole thing makes other political problems just sort of ... vanish.

And, their real constituents, the arms manufacturers, tell them war is good, and so it is. And so it is.

However, if speeches don't cause wars to be won in themselves, then Zelensky is in a dilly of a pickle, having fought an existential war to the last man ... only to accept terms offered on day one.

Of course, Russia likely knew the terms would be rejected, so they could then sell the war they want (total obliteration of the Ukrainian military as a going concern) even easier to the home audience, as nearly all Russians will agree A. Ukraine should be neutral and not host NATO missiles and nukes pointed at their cities B. Crimea should stay Russian and be recognized as Russian and C. Dombas should be independent.

At the end of the day, Russians are simply buying what Putin's selling as it makes sense to them, and he hasn't overplayed his hand by promising much more.

He's argued Ukraine is somehow apart of Russia already ... but there has not really been any actual demands to annex the whole of Ukraine, so that could be sort of contextual historical analysis not directly connected to any current political aim as well as a legal cover for conscripts in Ukraine, which did happen and may have been planned as a plan-C "if needs be" (as the conscripts can legally only defend Russia ... obviously, as @Benkei points out, the law doesn't really matter, but still pretextual justifications are needed, just as NATO made the pretextual justification to go from "No-fly-zone" to bombs everything that moved on the basis that anything that moved could in theory support an anti-air asset that in theory could support a plane that in theory could fly if Lybia had any left that weren't already shot down or bombed--it was totally preposterous reasoning, and the whole point is that doesn't matter). -

Ukraine Crisis... of course, that being said NATO can always hire Marvel and DC script doctors to do a clean reboot a la The Batman and Spiderman: Far from Home.

But does NATO have that kind of cash to attract that sort of talent?

And is there enough creative material and fan loyalty to avoid an X-men or Fantastic 4 ... just ... sort of fizzling out?

There's chances the franchise can keep loyal fans and build on that, but, honestly ... NATO may have to sell to Disney to access their production studios, creative pool and audience reach.

Sure, NATO's tapping yesterday's stars, but can Bono's edgy anti-establishment poetry he's so famous for, really get fans back in the seats? Can audiences really keep up with the franchise when there's huge drops like Obi Wan ... is Disney even prepared to pickup another creative orphan?

Uncertain times in the market, and I'm just not sure one hit, even as massive and totally adored on social media as it is now, is enough to fix plot things long term for NATO's creative executives.

Even die hard fans maybe difficult to keep committed if plot holes like NATO officers being killed in missile strikes don't have some sort of fan service resolution that keeps the older generation, that really grew up reading the old pre-NATO installments, like WWII, interested, while also reaching out to the new generation that thinks the SS were just total bad asses and it's just super fun to mix them up in a campy mashup of different characters fighting the new super villain; bringing out the "Red Army" is for sure a nostalgic throwback and safe choice for NATO, really directly addressing the core audience, but at the same time, even details like the new uniforms is a really big leap in design for them to take in, not to mention the whole re-conception of "The Soviet Red Menace" for a younger, more digital audience who connects more if they fear them as more of a "virtual" foe that's mostly just a danger to anonymous avatars online, than some actual "physical" enemy that may blowup entire cities at any moment, the classic "ticking clock" that kept eyes glued to screens in the 70s franchise heyday; but viewed by younger generations as a pre-internet tiresome gimmick. There's not even any submarines in this new story that happens nearly entirely on land, and for a lot of people that's a big disappointment; but maybe NATO's teasing a neo-Nazi submarine escape from Mariupole as a way to bridge those concerns, there's certainly no end to that sort of speculation about this sort of plot twist on the legacy fan forums, and maybe a way to really win over hearts that the rebranded neo-Nazi's as a ambiguous "anti-heros" that fans are supposed to empathize and understand in this new alliance, rather than that classic archetypal villain that just needs to be defeated for the plot to move forward, are a core part of the story now; of course, solutions may exist, such as another fan theory favorite is having them play that super cool submarine role, satisfying old fans demands to see more submarines as well a form of narrative continuation of the original Nazi's, of which submarines was a signature ability. -

Ukraine Crisis

The script literally writes itself.

My only worry is we can't go "bigger" in the next installment of the NATO cinematic universe. -

Ukraine CrisisI think this is why right wingers gravitate to obvious liars: it is a sign of strength and status, to be able to tell such lies. The stronger one is, the bolder the lies one is able to tell. — hypericin

Oh, you mean like the literal head of the CIA accusing, unnironically, the Russian's of waging an "information war".

Or ... do you have more in mind the current President of the United States saying he engaged in civil disobedience with Corn Pop as well as arrested in South Africa trying to see Mandela in prison.

Or maybe you have in mind something like George Bush joking about finding WMD's in Iraq, that they "gotta be around there somewhere"?

You have that sort of unaccountable lying ... or just Trump, who, last time I checked, does get held accountable for his lies, the liberal media repeats them ad nauseam and, unlike the neo-con's who bragged about "making the facts", Trump was held accountable in the democratic process and lost re-election and he's held accountable by the powerful all the time for his continued insistence the election was stolen from him. But, certainly Trump had so much power and was so unnacountable for anything he says that losing the election was the biggest expression of raw power the world has ever seen. -

Ukraine CrisisYou are the only war cheerleader here. — Olivier5

By recommending diplomacy be engaged with in good faith to try to end the war? And, simultaneously to that, diplomacy be used to protect civilians ... like evacuating them by boat from a port city.

Before this high intensity phase of the war began, diplomacy could have easily resolved it.

However, not taking that opportunity, now Zelensky and the West are faced with the problem that Ukraine won't be Russia's Afghanistan as their plan is to just completely demolish Ukraine's war infrastructure ... and most it's trained soldiers, and then just lay siege to cities until their demands are met.

And the whole thing of Western war hawks rushing to declare Ukraine Russia's Afghanistan as the insurgency will be impossible to manage (until shh, shh, shh we need to pretend their winning to justify sending the warms to fuel the insurgency) is premised on what:

1. The West's own Afghanistan was a completely immoral debacle and cluster fuck that simply killed Western soldiers for nothing, couldn't be won, and simply resulted in two decades of war and suffering and terrible deaths for normal Afghans only to be ruled, in the end, by fanatical extremists (the only kinds of people that fight an insurgency for 2 decades) that are even more extreme than before and now have zero fear of any Western military interventions of any kind and no diplomatic pressure can be placed on them whatsoever to alleviate people's suffering much less try to export those "Western values" I keep hearing so much about.

2. The conflict only benefited Western Arms dealers, just as this Ukraine conflict only benefits Western arms dealers at the end of the day.

3. The self-righteous refusal for years and years and years to negotiate some peace settlement with the Taliban, when there was far better position and leverage to do so, as "they're too evil", wasn't self-righteous and good faith at all, but just as an excuse to sell more arms ... considering negotiating with the Taliban is exactly what NATO does when they tire of the war and there's more arms to be sold in a new Cold war which is obviously coming (the pull out of Afghanistan happens after the Ukraine army start preparing for a large offensive in Dombas which solicits the totally expected and inevitable buildup of Russian forces, that must invade if there's no deal ... which NATO knows ahead of time isn't going to happen).

4. Ukraine will be totally wrecked by the insurgency and far more Ukrainians will be killed by fanatical extremists than Russians will be.

5. Ukraine, like Afghanistan, will serve as a extremist fighter training ground as well as giant arms depot, to then export extremist violence all around the region to destabilize any government of the CIA's choosing at any moment by providing more arms and money in exchange for focusing a generally omnidirectional fanatical rage on the target of the day, with "advisors" on the ground if things aren't going to great as over confidence is the fanatical extremist fighter's weakness and they keep dying in foolhardy attacks planned and executed entirely based on their own sense of superiority.

6. Decades from now, Ukrainian babies will be literally starving to death, and, just as with the West's Afghanistan, no one will care about the Russian's Afghanistan at that point in the future. Let them eat cake, those babies ... you know, if it's their birthday they certainly deserve it.

7. Such a public and long term moral and military disaster, waste of troops and equipment, will, just like the US, undermine Russia's security, position in the world, and erode their military's confidence and domestic and international image, leading, ultimately, to an embarrassing withdrawal (military loss) and signal to American "friends" that American "friendship" means dick-all and can't be counted on and also signal to all America's competitors that US public is tired of war and they need not fear any "boots on the ground" military intervention at any time in the near and medium and perhaps long term future, except maybe the supply of arms and dropping some bombs from time to time (2 things that can be easily dealt with technologically if you're any more sophisticated and prepared than Gadafi ... who honestly though he was a friend of the West, pitching his tent in the ).

When current and ex CIA, and other retired "Generals" and officials and so on, trip over the dicks and their tits to gleefully tell us Ukraine will be Russia's Afghanistan, it's exactly the above they have in mind.

Caption: European Union foreign policy chief Javier Solana talks with Gaddafi during a meeting in his bedouin tent in Brussels, on 27 April 2004; Photograph: European Council/Reuters

For, when you have friends like these ... who needs enemies?

Lybia post-NATO no fly zone and glorious liberation! -

Ukraine CrisisThey have already oil & gas pipelines to China and likely will build more: — ssu

Yes, but these pipelines across thousands of Kilometres do take time to build, so my reading is the nuclear ice-breakers are a plan B to ship oil out the arctic ... it's not like they'd be shipping beanie babies.

Yes, we will surely soon forget this thread and the media can focus on other issues, but as long as the war goes on, the effects of it will be there. And even if the war would tone down as it did after 2015 for seven years or there would be a cease-fire that held, the World has already changed. — ssu

My basic point is that the Western media will focus on something else as soon as focusing on this is inconvenient. Afghanistan babies starving to death is inconvenient, so we're focusing on the Russians now.

Normal people don't necessarily forget, but the Western media is pretty synchronous with whatever policy the West "needs to do right now" to deal with [insert outrage].

Problems today, for Western institutions, are whatever Western media says they are, proven by the fact Western media is saying it and, doubly so, by the fact Western institutions are answering the call to do something about it.

Opinions of normal people don't really matter in this conversation between Western media and Western institutions, just that Western bureaucrats and politicians and even CEO's know what they're supposed to be doing today, hating the people that need hating today and coddling the people that need sympathy today from knowing about, sometimes even interacting, with said hated group (but mostly just knowing about a hated group exists, even if they lack any power at all to affect your life, is oppressive enough). From time to time the conversation exists to explain that, yes it's unfortunate, but nothing really can be done to help people negatively affected by Western policies--no end of the "realist" supply when those issues are "debated". -

Ukraine CrisisCan you at least stop using obscene words like that all the time? I find it disgusting. — Olivier5

I find cheerleading a war to continue and for arms to be poured in to fuel it with zero consideration if that even helps the victims of the war and simply pre-supposing any criticism of the righteous war and arms dealers propping it up is unrighteous as we know it's righteous even if it doesn't, and shouldn't, encounter any criticism of that premise at all, is disgusting.

We all have our own tastes, don't we.

I don't even like ice-cream at all. -

Ukraine CrisisAn oil embargo has been talked about by EU foreign ministers. For example Poland is openly demanding it and naturally many countries are opposing it. At least yet. — ssu

I guess post it when it actually happens.

You have to make infrastructure investments and quite a dramatic realignment to stop Russian gas and oil trade. But it is totally possible. It simply cannot be done in weeks. But in few years, totally possible. — ssu

Agreed that some infrastructure adjustments would be needed if the EU stopped importing ... but I'm not sure by how much, as Russia has been investing massively in a fleet of nuclear icebreakers, which, I assume, is to be able to ship out oil and gas from the arctic; and that capacity may be already there, at least most of the year, if the tankers can just show up. -

Ukraine CrisisStep 11- millions of refugees resulting from the situation look to their noble benefactors for succor.

Step 12- noble benefactors: "fuck off, we've got a new crisis on the front page now" — Isaac

I totally forgot about all those unpaid extras! Can't make a war epic without them.

I feel so silk stocking liberal right now, you have no idea.

But yes, people genuinely believe this current New cycle won't go the way of terrorism, Afghanistan, WMD's, Iraq, banks stealing trillions of USD after corrupting the entire system leading to it's crashing and a public bailout and zero accountability, emails, grab em by the pussy, emails, piss tape, the leader of the free world threatening to turn another country into a lake of fire as foreplay for some sort of online bromance, US mass riots and looting and buildings burning, and war on drugs needing more war part, invasion of the world's superpower's capital buildings, mass shooting of the week, ice-cream flavours, Chavez, Iran, Chavez, Iran, Maduro, Iran, China pivot, migrants drowning all the time, opioids scandal, Lybia, sporadic but most important political identity crisis to ever happen, Syrira, Covid, Afghanistan, toxic male executives all the time (guilty as charged though ... and this one will make a comeback, just like the Red Army and cold war paranoia!). -

Ukraine Crisis

The backlash is people getting into severe cognitive dissonance which disrupts the war horny trance like state they were in previously, when they encounter the fact the "neo-Nazi" problem isn't some fringe skinheads in some seedy bar, but a whole institution.

Which, please pay attention to the "black sun" which doesn't even have any apologist "it's just a rune" or "ancient Sanskrit symbol" whatever explanation, but literally created by the SS for the SS.

And also discover, at least the US and Canada (... maybe not other NATO members like Germany, who are the experts on neo-Nazi's after all and arbitrate whether they exist or not in today's media landscape) exposed to be breaking their own laws, which was military aid was contingent on irregular forces not doing any fighting or getting any weapons or ammunition ... which journalists could just go debunk in like, a single day's investigation?

And discover ... that when people talk about this problem going back to 2014 ... there's times and BBC reportings on this very thing:

January First, is one of the most important days in their callender. It marks the birth of Stepan Bandera, the leader of the Ukrainian partisan forces during the second world war.

The rally was organized by the far right Svoboda Party. Protests marched amidst a river of torches, with signs saying "Ukraine above all else".

But for many in Ukraine and abroad, Bandera's legacy is controversial. His group, the organization of Ukrainian Nationalists sided with Nazi German forces [but fortunately we have modern Germany to tell us there's no connection!] before breaking with them later in the war. Western Historians also say that his followers carried out massacres of Polish and Jewish civilians.

[... interview with a guy explaining the importance of Stepan Bandera's birthday party ]

Ukraine is a deeply divided country, however, and many in its East and South consider the party to be extremist. Many observers say rallies like today's torch light march only add to this division [really?!?! you don't say...]. — BBC

Or discover this one which interviews the FBI talking about these terrorists training with Azov ... but ... wait, "the war on terror" doesn't extend to white terrorists training "oversees".

And has the quote (recorded on video) from one of the recruiters:

We're Aryans, and we will rise again — totally not a neo-Nazi, according to the German government

But ... the president is Jewish and is allied with these forces, who don't even hate Jews all that much! So obviously you can have Nazi's if their friendly Nazi's (to your side).

This one's just adorable. -

Ukraine Crisis...familiar plot? — Isaac

Completely familiar ... but even more familiar is the exact same script in Syria:

1. Russian army is incompetent, hahahahah

2. "Resistance" is winning the information war, so many videos of "resistance" victories online!

3. Gains Russian army are making mean nothing

4. The people Russia are fighting are freedom fighters, not a single fanatical extremist among them

5. We need to pour arms into the situation to give Russia their Afghanistan! Hurrah!!!

6. Russia is winning ... but playing unfair!!! Boohoohooo

7. Chemical attack is going to happen

8. Anyday now, chemical attack since Russia is winning on the ground, but Putin and Assad are so evil they'll use chemical warfare when their wining! (obviously if they were actually losing we'd just let that play out into a failed state).

9. Chemical attack is coming ... it's coming ... Assad and Putin are just that crazy, and they know we'll be upset about a surprise chemical attack!!! And they know we'll easily find out!! And it will isolate Russia on the world stage and totally backfire!! But nothing can stop their evil machinations!!!

10. Chemical attack! Chemical attack!

We're on step 9 of this play. -

Ukraine CrisisOh it has, among the European left and even in the extreme right. — Olivier5

OMG!!! Putin must be terrified!!!

But, even if that was true, there's clearly a big backlash to the neo-Nazi's and so on, otherwise the Western Media wouldn't constantly be saying we can't talk about it and people in this conversations wouldn't be all "shhhh, shhhh, hush, we don't mention the neo-Nazi's that helps Purit!" ... ok, well how does it help Putin if his "allure" is all gone? -

Ukraine CrisisIt's just damage control, I suspect. The idea is to combat the rapid depreciation of Mr Putin's allure in the West and elsewhere, as swift as the ruble's on the currency market. — Olivier5

This is simply not true. Putin's "allure" in the West is exactly the same as it was before: dictator, evil, murderer, Hitler, chemical weapons user, fascist and old soviet reactionary in addition to even older school Empirial Czarist as well.

His "allure" in the West hasn't "declined".

As for the rest of the world, China, India, Brazil, Africa etc. are staying neutral or then supporting Russia in buying gas and oil.

Indeed, EU's purchases of gas and oil far out-weigh any other sanctions or arms dealing with Ukraine.

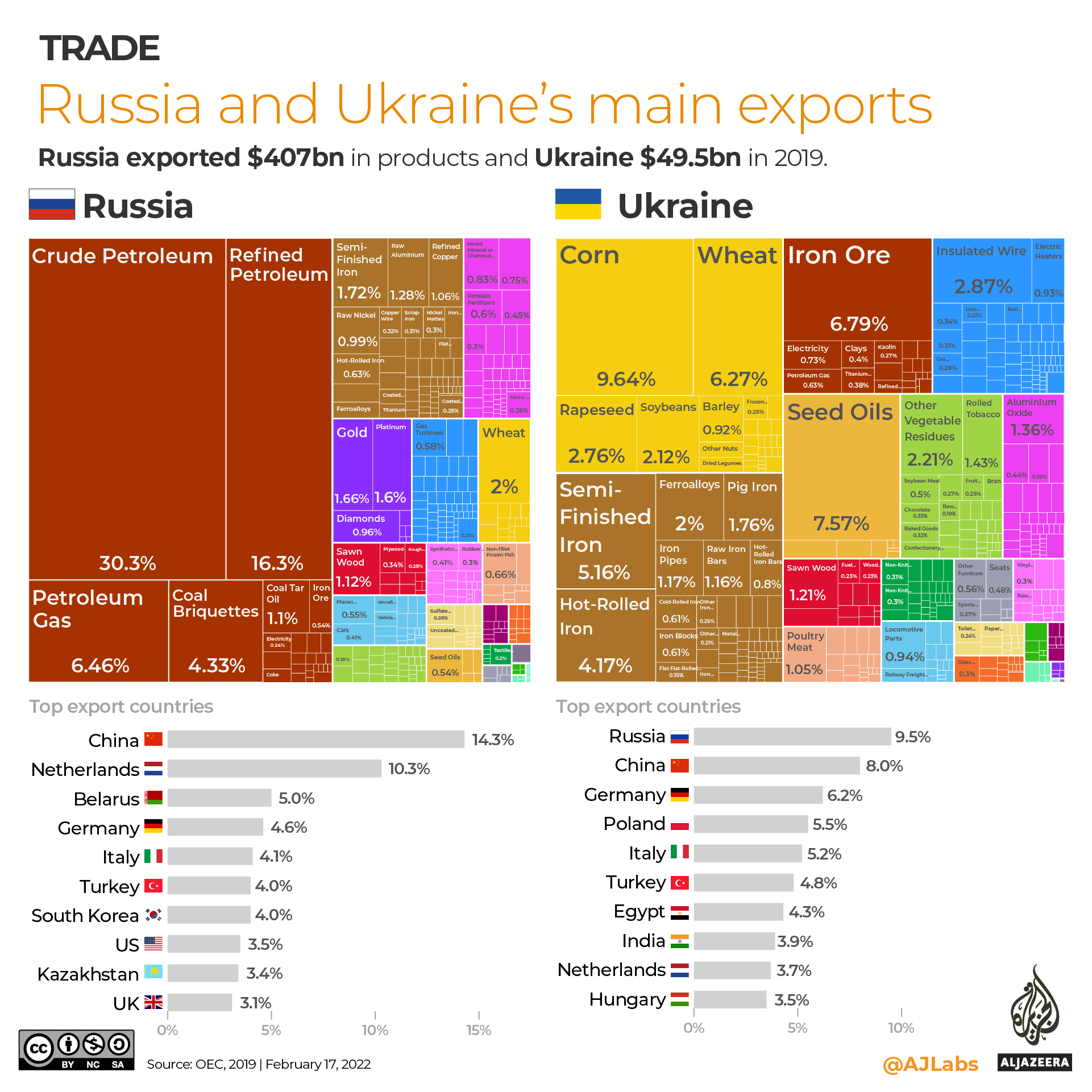

For example, check out this infographic

If you're not actually stopping the flow of oil and gas ... you aren't really doing anything of significance against Russia's economy.

What would be significant is blocking off real, tangible intellectual property that Russia needs to function (single points of failure that are disproportionate points of leverage, such as in Soviet times) ... but, oopsie, we sent all the Western IPR made by our superior "freedom based creativity" to Communist China and other East-Asian countries that aren't about to stop sending anything China buys to China to stop Russia buying it from the Chinese.

All the West has area brands and "spanking" Russia by pulling out those brands just cedes market share to the Chinese. It's a capitalist wet dream for the entire pantheon of competing brands to just "go away" from the market, and Communist China definitely understands that part of capitalism ... to go take that market share.

However, to make things even worse about the infographic:

Brown box is other raw mineral commodities totally unaffected by sanctions as everyone needs these kinds of commodities, in particular China, and Russia offering these at even a slightly cheaper price, will be bought up, and the most that happens is global resource flows just change around a bit.

The pink box is petroleum derivatives, totally unaffected by sanctions, same reason as above.

The purple box is precious metals, again easy to sell and also just easy to stockpile as part of central bank holdings.

Yellow is food ... no one about to "not buy food" if they need it.

Beige and orange also food.

Red is wood products, again commodity not going anywhere on the international market.

Blue is capital equipment that, guaranteed, Russia isn't selling much of to Europe and likely those trade relations are totally unaffected by sanctions.

In short, pretty much the entire infographic of Russia exports are either totally unaffected by sanctions ... even by their "enemies" such as the EU sanctioning them, or then, at best, just re-orders international material flows a bit but in no way stops those Russian exports.

And since the war increases commodity prices generally speaking, even if Russia has to undercut competition in the markets it has access to (... like one of largest economies in the world, China, but also India isn't sanctioning Russia, and certainly not Russia's post-soviet allies that remain and Iran and so forth) ... is still selling at a larger profit than before the war, that then easily pays for the war.

People think this is Soviet collapse 2.0 ... depressing commodity prices (intentionally or just because cheap oil was plentiful back then) and restricting critical IPR (in particular computation) was a big part of the unravelling of the Soviet Union. If the Soviet Union was making bank on its core business of commodities then likely it could have kept people happier during its reform programs ... which it was only trying to do in the first place because, back then, IPR economy was king (and commodities ran on thin margins) and the whole Soviet system wasn't great at IPR style capitalism to constantly innovate the new bling people crave (you know, after they've been told they crave it by marketers).

But we're now at the end of the great capitalist "innovate your way out of your problems" 500 year run, and there isn't really any new "must have" gadgets that keep the "myth of progress" narrative going.

Westerners have cell phones ... so do Russians, and the "grass is greener" effect also no longer works as Russia has now tasted Western style capitalism and most Russians think they were better off under communism ... so, isn't that happening, certainly at least in the authoritarian component, just "democracy". -

Ukraine CrisisOr possibly, are you just such an arrogant twat that you think whatever you've heard simply must be true because, unlike all those other dupes, you couldn't possibly be being fed a narrative, you wouldn't fall for that. It's only everyone else who falls for that. — Isaac

Well, to be fair, I'm falling for this narrative this very moment. -

Ukraine Crisis

Dude, the whole current war is precisely because NATO isn't Ukraine's friend ... or it would be in Ukraine right now shoulder to shoulder, protecting its "friend".

Saying NATO arms dealing with Ukraine is "friendship" is like saying your meth dealer dealing you meth is "friendship".

Maybe you need the meth, but big mistake thinking your meth dealer's your friend. That's how suicides happen. Public service announcement everyone. -

Ukraine CrisisI can't respond to all the responses to me just yet.

However, I wanted to drop this analysis that seems, so far in my research, the best overall view of the crisis and each expert more-or-less predicts exactly the current situation in their area, and also agree on where their subjects overlap.

Anatol Lieven even predicts the exact Russian political strategy, which is to not "occupy" and passify the country, but just hold territory militarily, blowup everything that's a threat, and basically demand Ukrainian Neutrality and independence for Dombass regions.

The military experts correctly predict it will not be "half measures" but a full scale invasion, and the political experts correctly predict Russia can likely withstand the sanctions.

When searching for theories, you don't actually want too much analysis of current "just happened" information (although that's useful too, and necessary to even have some idea of what a theory would need to explain, just that so many theories can fit today's data), but rather theories in the past that predict the current information; i.e. predictive power, is what is most insightful.

The absolute key takeaway is: "The Swedes could join NATO, or could join any other alliance, they still won't fight." -

Ukraine CrisisIn your cryptosoviet dreams. — Olivier5

This is literally what has just happened with cold war 2.0.

It's not a Soviet dream ... soft power didn't matter much in the cold war, but mattered a lot after the cold war, and again doesn't matter much in the new cold war.

EU doesn't have hard power, NATO does and it's lead by the US (which isn't even in the EU), so, as the worlds largest economic block, the EU had a lot more soft power in the global integrated economy as it existed before this war in Ukraine and schism in said globally integrated economy. -

Ukraine Crisis↪boethius Yeah, I get that, but, you know, actions speak louder than words. — Wayfarer

The BBC and other Western media are starting to "prepare" people for a negotiated settlement ... whether to encourage that to happen or then it's already been "more or less" worked out behind the scenes. Keep in mind Russia and US still have the "nuclear emergency phone" so may have been having a totally parallel top level negotiation all this time.

We certainly don't know the facts on the ground, but Russia and US certainly have a pretty good picture. If Ukraine can't win, then both Russia and US certainly know that, and they may have already worked out "a deal" of some sort.

Negotiation between the big powers is always secret and they can always "horse trade" all sorts of stuff, certainly to the disapproval of everyone here.

At the end of the day, Biden wants to be reelected more than he hate Russians, and so he's "pro Ukraine war" when that boosted his ratings, and now that there's not only blowback but potentially a lot more blowback if the war continues, he / administration maybe willing to work out a deal with Russia (there's all sorts of diplomatic channels to "feel things out", but the nuclear phone would be the most "dramatic" and I assume has been used in all these nuclear escalation talks).

The big liability for Biden if the war is not resolved is that supporting Ukraine and denouncing Russia has played well in this phase, but if Ukraine loses then he looks weak, which is worse in American domestic politics and all these international relations considerations.

So, at this particular moment of the war, everyone, in particular US and Russia (the people with all the nuclear weapons) can call it quits and still say they won.

As I said previously, Zelensky is entirely dependent on NATO, therefore the US, to supply his army, so will accept whatever deal US tells him to accept.

I want to see a resolution because I don't like people dying. Morality questions are easier to discuss with people that are still alive. -

Ukraine CrisisSome Kremlin PR hack drafting respectable-sounding diplomatic soundbytes to feed to the media, meanwhile Putin's army is destroying entire cities full of non-combatants because his troops are too incompetent to win on a battlefield. — Wayfarer

This is literally the BBC ... yes, state media, but the British state media last time I checked.

boethius

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum