Comments

-

The "Big Lie" Theory and How It Works in the Modern WorldWhat do you think—does this mechanism still hold today? — Astorre

I don't think that it's so much a conscious strategy, as the fact that America twice elected a Big Liar as President. If that hadn't happened, then we wouldn't be discussing it - there would still be plenty of disinformation and false news about, but it wouldn't be emanating from the Oval Office. -

On PurposeYou keep accusing me of exactly what I don’t claim — apokrisis

You said "That which is initially some unfiltered instant becomes sharply framed in terms of its particularity within a setting of generality. Firstness as an initial vagueness is transmuted into Firstness as some crisply fixed quality held within a system of interpretance. It becomes seen as a particular instance of the general thing we have learnt to label as "redness". The transformation of "unfiltered instant" into "some crisply fixed quality held within a system of interpretance" - reflects the nominalist tendency to treat qualities as products of classification, not as independently real (as Peirce does). That is conceptual nominalism: the idea that qualities only become real in or through being subsumed under general concepts or categories.

The question I am engaged with is “if not monism, then what?” — apokrisis

It's the same thing. Physicalism is monist, because it presumes only one fundamental substance, matter~energy. The epistemic cut then has to be represented as being an aspect of the physical world, because, if it's not physical.....

Peirce speaking in the spirit of his time and place.... — apokrisis

You always use that excuse to deprecate Peirce as idealist. 'Oh, he was a man of his times, he didn't know about systems science'. He was a thoroughgoing idealist, he said it himself many times. (He was before Moore and Russell's rebellion against idealism.) The 'holism of the triadic relation' is only an aspect of Peirce's ouevre, but it's the part biologists have appropriated for their purposes. I'm sure that Peirce would see the Cosmos as alive.

Peirce understood the divine not as a traditional, anthropomorphic God, but as a creative and unifying force inherent in the universe, manifesting as thirdness and the tendency towards order and habit-taking.

Sure. No problem with that at all. Besides, I never advocate for belief in God. There's no creator God in Buddhism. And that passage sounds like something you would find in many philosophies.

My antagonism is about your constant efforts to frame any comment I might make as reductionist and scientistic — apokrisis

I didn't introduce those terms. I said 'physicalist', which is how you described yourself. About the fact, as I said, and to which you didn't respond, that your system has no real place in it for human beings, as several others have commented. And the fact that the only place for organic life in your model is as kinds of heat sinks. What is there to like about that? -

On Purposethis is indeed an issue I am wrestling with right now in its most general physicalist sense. — apokrisis

I want to try and draw a line here. You came into this thread advocating physicalism, which as you know I disagree with. When I challenged it, you said

Remember how you like to seize on "objective idealism" as if Peirce's careful triadicism – or hierarchical causality – can be heedlessly reduced to your brand of dualism? The two forms of Cartesian substance. — apokrisis

Well, first of all, Peirce is known as a theistic idealist and often said as much:

I am an absolute idealist of the Hegelian type, though not a follower of Hegel. I believe the whole universe and all that is in it is a divine mind, realizing its own ideas, partly by direct creation and partly by the development of its own germs in the minds of its creatures.

— The Monist, Vol. 15 (1905)

I'm not an advocate for dualism, but I think it has a big influence on the conversation. Because, the lurking question is: if not physicalism, then what? That is a question that you don't want to deal with, because the implications must be, to your mind, some kind of dualism, and that territory is forbidden. Pattee says that straight out in the first part of Physics and Metaphysics of Biosemiosis. (Peirce also rejected Cartesian dualism.)

From a draft I'm working on:

'One of the most far-reaching consequences of Descartes’ dualism was not just philosophical but cultural: it effectively divided the world between *res extensa*, the extended, measurable substance that would become the domain of science, and *res cogitans*, the thinking, immaterial substance reserved for religion and theology. At the time it was formulated, this demarcation helped defuse tension between the rising authority of mechanistic science and the theological dominance of the early modern Church. Matter could be studied freely, so long as the soul remained untouched (and that was an explicit entry in the original Charter of the Royal Society.) But the cost of this division was steep: it left the mind stranded outside the physical world, and set the stage for centuries of debate about how—or whether—it could ever be brought back in. Physicalism had to insist that mind is the product of material causation, via neurology and evolution - it could have no reality in its own right, for these very reasons. And that still is probably the majority view. '

That is why the two fields of phenomenology and embodied cognition (or enactivism) are so important. They're not either physicalist or idealist (although phenomology was undoubetdly descended from Kantianism.) That is an emerging paradigm that has many areas in common with biosemiotics, although not so much with the physics-driven 'theories of everything' which you spend a lot of time writing about.

That's what I think is the cultural impetus behind the appeals to physicalism and antagonism towards anything perceived as spiritual or idealist. It's the consequence of this division. -

On PurposeNominalism. Just what Peirce wasn’t.

Peirce understood nominalism in the broad anti-realist sense usually attributed to William of Ockham, as the view that reality consists exclusively of concrete particulars and that universality and generality have to do only with names and their significations. This view relegates properties, abstract entities, kinds, relations, laws of nature, and so on, to a conceptual existence at most. Peirce believed nominalism (including what he referred to as "the daughters of nominalism": sensationalism, phenomenalism, individualism, and materialism) to be seriously flawed and a great threat to the advancement of science and civilization. His alternative was a nuanced realism that distinguished reality from existence and that could admit general and abstract entities as [immaterial] reals without attributing to them direct (efficient) causal powers. Peirce held that these non-existent reals could influence the course of events by means of final causation (conceived somewhat after Aristotle's conception),and that to banish them from ontology, as nominalists require, is virtually to eliminate the ground for scientific prediction as well as to underwrite a skeptical ethos unsupportive of moral agency. — Peirce and the Threat of Nominalism (review)

Chalk and cheese. -

Donald Trump (All Trump Conversations Here)It’s a criminal referral for what DNI Gabbard called a “treasonous conspiracy” — NOS4A2

A made-up report which directly contradicts an earlier, bi-partisan report, chaired by Marco Rubio, now Glove Puppet of State, which established that Russia really did try to meddle in the 2016 election, had a hand in publishing leaked DNC documents, and had favoured Trump over Clinton, but had not been able to change any actual votes.

And Trump accuses Obama of treason :rofl:

Impeach Now! :rage: -

On PurposeThe hallmark of phenomenology is its emphasis on the first-person character of experience.

— Wayfarer

Thanks for the lecture. But Peirce got it right by showing how the real story is about the hierarchical order of first, second and third person perspectives. First person leaves you stuck on the platform of idealism long after the train of useful discourse has departed the station. — apokrisis

Peirce didn’t treat Firstness as something to be discarded — it’s not simple subjectivity or a leftover from idealism. It refers to the irreducible immediacy of experience — qualities as they are felt or intuited before they're interpreted or acted upon. That’s not something that can be explained away by pointing to Thirdness (rules, mediation) or even Secondness (facts, brute reaction). 'Peirce usually attempts to explain firstness, in general terms, as quality or feeling'. Hence, first-person. (Qualia, in fact!) Without Firstness, nothing shows up to be reacted to or interpreted in the first place.

Where is the number seven? The law of the excluded middle? The Pythagorean theorem?

— Wayfarer

Why don't you tell me where you think they are? — apokrisis

They are principles and ideas which can only be grasped by reason, intelligible objects. So they're not existent, but they're real, in that they're the same for all who think:

I do not mean that universals exist, but they are real. — C S Peirce Collected Papers, CP 1.27

The Cosmos exists as the universal growth of reasonableness. — apokrisis

Agapasm... is that mode of evolution in which the original germinal idea, in growing, continually puts itself into deeper and deeper harmony with its own nature, not as a mere development of a mechanical necessity but by virtue of a sympathetic and benevolent attraction, an agapē, an outgoing love. — Collected Papers, CP 6.287

Differential equations were invented and the Western world went Newtonian. The industrial age was unleashed. — apokrisis

Appeals to progress don't begin to address the philosophical point at issue. -

On PurposeYou mean history shows we ignored the folk dumb enough to claim that. — apokrisis

Some of whom were eminent scientists.

There is the phenomenological experience of those of us for whom the maths of symmetry and symmetry breaking might truly have a look and a feel of some Platonic reality. It is a full sensori-motor experience. — apokrisis

The hallmark of phenomenology is its emphasis on the first-person character of experience. It begins by seeking to retrieve this dimension, which had been methodologically excluded by the quantitative orientation of modern science. This is the central concern of the opening section of Husserl’s Crisis of the European Sciences — to show how the lived world (Lebenswelt), the world as it is experientially given, was eclipsed by the objectifying methods of natural science. Hence Husserl's remark that Galileo was both a 'revealing and concealing genius'.

(Phenomenology, in this sense, is more than a philosophy of subjectivity, but a disciplined attempt to return to the conditions of meaning and appearance that make objective knowledge possible in the first place. It does not reject science, but seeks to clarify its experiential and conceptual ground.)

But the point of the mind-created world idea is that we do of course see reality through mental constructs and theories, as well as sense-perception. It is the mind which synthesises these into the unity of subjective experience. And the sense of what is physical relies on that, which is not itself physical. That is the world as it is lived by us, the lebenswelt. Mental and physical, mind and world, are all aspects of that.

As far the epistemic cut is concerned, I think that it signifies an ontological discontinuity, as well as an epistemic one. It reflects a real discontinuity in nature herselt: between matter and meaning, mechanism and interpretation, dynamics and semiosis. But you will reject that because it suggests dualism, which you've made your distaste for abundantly clear - again because of the shadow of Descartes.

What is nous when it is at home? — apokrisis

Where is the number seven? The law of the excluded middle? The Pythagorean theorem?

One of the texts I'm reading is The Phenomenon of Life, Hans Jonas (1966). The first essay in that anthology is about the fact that in the pre-modern world, life was seen as the norm, and death seemed an anomaly - hence the cults of the 'risen Christ' and similar religions. With the Renaissance, this began to invert, so that finally, dead matter is seen as the norm, and life the anomaly, something which has to be explained. And I think that's what your model does. But the problem is that there is really no room in it for the human being. Beings are just kinds of heat-sinks, mechanisms by which entropy seeks the path of least resistance. And that's why the only logical outcome of the model is death. After all, if the physical is all there is, then that is all that can be expected. -

On PurposeThe we in us is still the ghost in the machine. — Punshhh

Which will, however, not outlive it. The ghost is neither the machine, nor anything apart fro it. A figment, in fact. -

On PurposeIf something is not forbidden, it will occur. — apokrisis

By what, by the way? We used to think that the laws of physics forbade powered flight. -

On PurposeWhat I'm saying, on the contrary, is that nothing is purely physical, that the physical itself is itself an abstraction from experience. And where do abstractions dwell?

— Wayfarer

Yes. Where do they dwell? Follow your own argument through. — apokrisis

There are many things, abstractions among them, that are only perceptible by nous. They don't, therefore, dwell anywhere, in the literal sense, as they're not bound by time and space. But real, nonetheless. Hence, 'mind-created world'.

I do not mean that universals exist, but they are real. Real, I say, in the sense that they are not figments of the mind but have an objective being, though not a material existence. — C S Peirce Collected Papers, CP 1.27 -

On PurposeLife and mind the insert themselves into this larger story by accelerating the entropification. — apokrisis

But notice that 'insert themselves' implies agency.

Organisms have to be embodied. They must build a physical structure that is a molecular machinery with a metabolism that can digest their surrounds. — apokrisis

Why must they? What imperative drives that? Oh - that's right. It's something that could happen, therefore it did.

A body is nothing more that a physical structure that can rebuild itself just slightly faster that it falls apart. — apokrisis

There's your materialism showing again.

There. Is that enough phenomenology for you? — apokrisis

It's not phenomenology at all. There's a glaring omission in your model, as philosophy, but as it's situated squarely in the middle of the blind spot of science, I'm guessing it's something you wouldn't recognize. That blind spot is the consequence of the methodical exclusion or bracketing out of the first-person ground of existence.

Incidentally, with respect to Peirce's phenomenology, he said '‘…to decide what our sentiments ought to be towards things in general without taking any account of human experience of life, would be most foolish’ ~ C S Peirce, Philosophy in Light of the Logic of Relatives. Yet in your model, human experience only exists by happenstance, and then only to expedite entropy.

I'm not proposing dualism.You interpret what I'm saying through that perspective, because the mindset you're working within is post-Cartesian, which started off by dividing the world into mind and matter, and then rejected the model as incoherent (which it is) - leaving only matter. But I'm not trying to re-introduce mind as a 'thinking substance'. What I'm saying, on the contrary, is that nothing is purely physical, that the physical itself is itself an abstraction from experience. And where do abstractions dwell? -

On PurposeThis view understands interpretation not as conscious self-awareness, but as a more basic responsiveness to environmental signals — a kind of primitive subject-hood inherent in the way organisms engage with their surroundings, qualitatively distinct from the behavior of non-living matter

— Wayfarer

How is it "qualitatively distinct from the behavior of non-living matter" if such responses can be wholly explained on physical principles? We understand, for example, the electrochemistry of neurons and how they combine to form neural networks responsive to the environment. Indeed, this connectionist theory is the basis of many artificial intelligence programs. — Dfpolis

The enactivist approach doesn’t deny the role of electrochemistry or physical principles active in living organisms. But it emphasises that the behaviour of organisms is not wholly explainable by mechanism - which is a metaphor - but as a self-organizing, value-directed engagement with the world.

AI programs may simulate intelligence, but they aren’t beings — they don’t enact a world from within. They're not alive, and the distinction is crucial (I have a draft on this topic.)

That’s the point phenomenology and enactivism insist on: that organisms are subjects, not just systems. They have to negotiate their environment in order to survive and to maintain homeostasis. And homeostasis is not represented in the principles of physics.

Aristotle’s hylomorphism (form + matter) is explicitly non-reductive. The form of a living being is not a shape, but a principle of organization and activity — a telos. A heart isn’t just a pump; it's something that beats for the sake of circulating blood within an organism. That “for the sake of” is not captured by efficient causality alone. He opposed Democritus precisely because atomism treated form as accidental, whereas Aristotle saw form as essential — the organizing principle that makes something what it is.

“Soul is the first actuality of a natural body that has life potentially.” — De Anima, II.1

One immanent state can only yield one course of action. To have choices, several future states (alternative courses of action) must be immanent. This multiplicity cannot be found in a being's determinate physical state, but it is experienced in our intentional life. — Dfpolis

If organisms were nothing but deterministic physical systems, how would anything ever have evolved? Evolution doesn’t work on pre-programmed machines — it works on organisms that can vary, explore, adapt, respond in ways that are not reducible to mere stimulus-response mechanics. Again this is where Aristotle was prescient - he saw that the principles which govern organisms must allow for things to both change and yet somehow retain their identity. Darwin wrote that Aristotle 'shadowed forth' the idea of evolution (although not, of course, of natural selection.)

Ironically, your own point — that “one immanent state can only yield one course of action” — undermines the possibility of behavioral variation, which is essential for natural selection. If a given physical state leads only to one behavior, then there’s no room for differential response — and without that, there's nothing for evolution to select from. The very possibility of evolution requires that multiple courses of action can emerge from structurally similar, or even “identical,” physical configurations. That’s not just a point about consciousness — it’s a foundational insight for biology.

physical systems have material states, and intentional laws. What they do not have is an intrinsic source of intentionality. This seems to apply to the entire universe prior to the advent of conscious beings, and to most of the universe since. — Dfpolis

I would say ‘prior to the advent of life’ - which is self-organising in some fundamental way. -

On Purpose"Markoš concludes that all living creatures are interpreting subjects, and that all novelties of the history of life were brought into existence by acts of interpretation."

There is no reason to think that most non-human creatures are conscious of anything. Positing that they are is a pure, unsupported extrapolation. It is much better to confine our conclusions to those supported by evidence. — Dfpolis

This view understands interpretation not as conscious self-awareness, but as a more basic responsiveness to environmental signals — a kind of primitive subject-hood inherent in the way organisms engage with their surroundings, qualitatively distinct from the behavior of non-living matter. All organic life 'interprets' in a way that the inorganic domain does not, so as to preserve itself. The point is not to attribute conscious awareness to single-celled organisms or plants, but to acknowledge that the rudiments of agency — selecting among possibilities in response to internal states and external cues — emerge much earlier in the history of life than previously assumed.

Life is not just self-organizing and adaptive; it is also purposive and sense-making. Even the simplest organisms enact a world of significance in their adaptive and goal-directed activity. They are not merely pushed around by physical forces; they regulate themselves in relation to what matters to their continued existence. — Evan Thompson, Mind in Life (précis) -

Does anybody really support mind-independent reality?I didn't ignore them intentionally - I just didn't notice them (and still don't know which comments you're referring to. The word ‘fallacies’ appears just once on this page, in the post above this one.)

-

On PurposeReading more from Barbieri's A Short History of Biosemiotics, this passage caught my eye:

Hermeneutic Biosemiotics

In Readers of the Book of Life (2002), Anton Markoš has proposed a view of the living world that is based on interpretation, like sign biosemiotics, but that was inspired by the hermeneutic philosophy of Martin Heidegger and Hans Georg Gadamer, and has become known as biohermeneutics or hermeneutic biosemiotics...

The starting point of Markoš’s approach is the problem of ‘novelty’. Do genuine novelties exist in nature? Did real novelties appear in the history of life? In classical physics, as formulated, for example, by Laplace, novelty was regarded as a complete illusion, and even if this extreme form of determinism has been abandoned by modern science, the idea that nothing really new happens in the world is still with us. It comes from the idea that everything is subject to the immutable laws of nature, and must therefore be the predictable result of such laws. There can be change in the course of time, but only relative change, not absolute novelties.

Against this view, Markoš underlined that in human affairs we do observe real change, because our history is ruled by contingency, and entities like literature and poetry show that creativity does exist in the world. He maintained that this creative view of human history can be extended to all living creatures, and argued that this is precisely what Darwin’s revolution was about. It was the introduction of contingency in the history of life, the idea that all living organisms, and not just humans, are subjects, individual agents which act on the world and which take care of themselves. Darwin did pay lip service to the determinism of classical physics, but what he was saying is that evolution is but a long sequence of “just so stories”, not a preordained unfolding of events dictated by immutable laws (Markoš et al. 2007; Markoš et al. 2009).

According to Markoš, the present version of Darwinism that we call the Modern Synthesis, or Neo-Darwinism, is a substantial manipulation of the original view of Darwin, because it is an attempt to explain the irrationality of history with the rational combination and recombination of chemical entities. Cultural terms like 'information' and 'meaning' have been extended to the whole living world, but have suffered a drastic degradation in the process. Information has become an expression of statistical probability, and meaning has been excluded tout court from science.

Darwin has shown that the history of life is as contingent as the history of man, and Heidegger has shown that man can create genuine novelties because he can interpret what goes on in the world. From these two insights, Markoš concludes that all living creatures are interpreting subjects, and that all novelties of the history of life were brought into existence by acts of interpretation.

Much more my cup of tea. :halo: -

On PurposeBut then biology can shrug its shoulders and say they see this magic property in every enzymatic reaction — apokrisis

Biologists do that. Biology doesn't shrug.

biosemiosis cashed out in a big way when we discovered that biology is basically about classical machinery that is able to regulate quantum potentiality for its own private purpose. — apokrisis

Right - the beginning of intentionality, as I said in the OP. The origin of the self-and-world divide.

I really think your physicalist biosemiotic theory could be leavened with some phenomenology. It's a missing element, as far as the philosophical content is concerned.

I'm neither 'quibbling' nor 'hung up'. And this is a philosophy forum, with a broader remit than science. -

On PurposeA systems causality already accounts for ultimate simplicity as it says that emergent complexity is what simplifies things in the first place. As Peirce puts it, logically the initial conditions of systematic Being is vagueness or firstness. A chaos of fluctuation that is neither simple nor complex. But as constrained regularities start to form, so does the simplicity of fundamental degrees of freedom begin to show.

This is the story of the Big Bang. — apokrisis

Thanks — I follow the systems logic you're articulating (well, up to a point) but I think there's something more that needs considering: the emergence of interpretation, signs, meaning. Once codes arise — symbolic systems that are rule-based, context-sensitive, and capable of being read — we've crossed a threshold. This isn't just more complex thermodynamics; it's the birth of agency.

If organisms interpret signs and act based on goals, then something new is in play: not just constraint, but intention. This shift isn't captured by the idea that life merely “entropifies better.” That framing suggests a kind of nihilism — reducing agency, purpose, and value to entropy-optimization strategies. It risks explaining meaning by dissolving it. So the question can be asked: are you actually dealing with the problems of philosophy? I mean, the problem of agency is surely central to the question of human identity.

Given the readiness of the physical world to invest in such biological structure, the telic pressure for life to arise becomes irresistable. Yes, for such an information-based machinery to evolve is quite a leap in terms of complexity. But equally, if it could happen, it had to happen. The desire was there.... — apokrisis

...hence also the intention! Saying "it had to happen" isn't that far from saying "it was meant to be." And once you admit something like "desire" into the lexicon — even metaphorically — you're no longer in a purely entropic domain. You're on the threshhold of semiosis, value, and, again, agency. In fact I think the question can be asked if semiotics is really a physical phenomenon at all. As Marcello Barbieri argues, the emergence of biological codes — such as the genetic code — was not merely an incremental extension of chemical complexity but an ontological leap. Codes linking signs to meanings are not derivable from physical laws alone. That’s what makes them novel — and marks the boundary between life and non-life, mechanism and meaning.

(Although I will hasten to add, I only heard of Barbieri in the first place through researching your posts on biosemiotics.) -

On PurposeThe artillery officer, the war planners, and the politicians are all human. I've never claimed human actions can't have purposes and goals. — T Clark

It is not so easy. Are human ends and purposes completely separated or cut off from the processes and activities of nature? (Leaving aside kicking the ball into the long grass by declaring it ‘metaphysical’.)

Thank you.

Although I think this is precisely because the sunny Popular-Mechanics style realism doesn't fully eliminate teleology or teleonomy; it just sort of lets the issue float out there, — Count Timothy von Icarus

Perhaps it’s as simple as this: properties like mass, velocity, or charge lend themselves to unambiguous measurement and quantification. Purposes, goals, and aims, on the other hand, resist formalization — except in the purely mechanistic sense of trajectories or optimization functions. So modern science quietly brackets teleology, not necessarily because it’s false, but because it isn’t easily mathematized. But ‘not everything that counts can be counted, and not everything that can be counted, counts.’ -

Why are 90% of farmers very right wing?I would have thought that the Left, historically being the side for the working class, it would be natural they would be on that side. — unimportant

There was a book I looked at once - didn't read it - called "What's the Matter with Kansas? How Conservatives Won the Heart of America" by Thomas Frank. It was very much about the rightward drift in the rural heartland of the US. And that was published in 2004, but seems to me still pretty current. If anything it's become even more pronounced. You can find some details of the book onWikipedia.

More recent titles on similar themes:

-

"The Politics of Resentment: Rural Consciousness in Wisconsin and the Rise of Scott Walker" by Katherine J. Cramer (2016): This is a highly influential ethnographic study that directly examines the concept of "rural consciousness" – how rural residents perceive themselves as distinct from and often disrespected by urban dwellers, and how this shapes their political views. It provides a deeper, on-the-ground understanding of the resentment Frank alluded to.

"White Rural Rage: The Threat to American Democracy" by Tom Schaller and Paul Waldman (2024): A very recent and provocative book that directly addresses the disproportionate political power of white rural voters and argues that their grievances, combined with a susceptibility to conspiracy theories and anti-democratic sentiments, pose a significant risk to American democracy.

"The Rural Voter: The Politics of Place and the Disuniting of America" by Nicholas F. Jacobs and Daniel M. Shea (2024): This book offers a comprehensive analysis based on extensive survey data of rural voters. It delves into their sense of place, economic anxieties, and perceived belittlement, arguing that these factors are more central to their voting behavior than often assumed.

"Building a Resilient Twenty-First-Century Economy for Rural America" by Don E. Albrecht (2020): Focuses more on the economic realities of rural decline, examining specific communities affected by the loss of traditional industries (manufacturing, mining, agriculture) and how these economic shifts impact political choices.

"Deer Hunting with Jesus: Dispatches from America's Rural Culture War" by Joe Bageant (2007): A raw and personal account from a journalist returning to his rural roots, exploring the cultural and economic frustrations that fuel conservative populism. -

On PurposeI honestly have never found a convincing argument that shows that life and consciousness can be understood in a similar way as 'temperature', 'pressure' and so on 'emerge' from the properties of the constituents of an inanimate object. — boundless

Agree that it's a hard problem!

Notice that even for the non-living things, we can understand their 'behavior' in reductionist and holistic terms. The pressure of a gas can be understood as arising - 'emerging' - from the properties of its constituents. — boundless

However, and this is something that I picked up from one of the sources I mentioned earlier, organisms try to persist - they try to keep existing. Inorganic matter has no analogy for that.

Many decades ago, I had the set of six books by Swami Vivekananda on yoga philosophy. Vivekananda's concept of 'involution preceding evolution' is an aspect of his philosophical framework that bridges Eastern spiritual thought with Western scientific ideas. In this understanding, involution refers to the process by which consciousness becomes increasingly involved in or identified with matter, transitioning from subtle to gross manifestations. This is essentially the descent of consciousness into material form.

Evolution, then, is the reverse process - the gradual awakening and return of consciousness to its original state. Rather than consciousness emerging from matter (as materialism suggests), Vivekananda proposed that consciousness is already present in a latent, involved form, and evolution is simply its progressive unfoldment and manifestation. 'What is latent becomes patent'.

He thought that this framework reconciles Darwinian evolution with Advaita. He saw biological evolution as one layer of this broader process, where increasingly complex organisms provide better vehicles for consciousness to express itself. The ultimate goal of this evolutionary journey is the complete realization of our true nature - what Vedanta calls mokṣa.

Can't see it gaining many followers in evolutionary biology but to me it's an attractive, alternative paradigm. -

Does anybody really support mind-independent reality?Perhaps we should resist the equation of explaining something with reducing it. — Ludwig V

Perhaps 'understood in its own terms' was what I meant. -

Does anybody really support mind-independent reality?for instance, if a human was to be simulated down to the neurochemical level — noAxioms

Big 'if'. If mind (or life, or intelligence) is truly not reducible, then it's also not really explainable in other terms. -

On PurposeIt appears to me like you are getting sucked in by physicalism. — Metaphysician Undercover

Heaven forbid :yikes: But to truly win a battle, you must fight your opponent on his strongest grounds.

Life and mind then lucked into codes – genes and neurons – that could act as internal memories for the kind of constraints that would organise them into organismic selves. — apokrisis

Brilliant post, as always — your framing of emergence via the simplification of local degrees of freedom to allow for global order is spot on, and I’m strongly drawn to that systems-theoretic rehabilitation of formal and final causation. In fact a lot of what I'm reading now arises from my encounter with your posts on biosemiotics (along with phenomenology).

But there’s one phrase I want to call out: “life and mind then lucked into codes.” That feels like the crucial hinge in the story.

The emergence of codes — systems of symbolic representation that are arbitrary, rule-based, and capable of being interpreted — seems to me not just an evolutionary convenience but an ontological shift, a change of register. There’s a crucial distinction here that Howard Pattee describes (here): even if a system is entirely physically describable, its function — as a code, a memory, or a measuring device — is not derivable from that physical description. It requires selection among alternatives, and that involves interpretation, choice, or constraint relative to a purpose.

The concept of selection, natural, cognitive, or any other form, implies a choice of alternatives. The alternatives may be considered real, virtual, or states of a memory, but in any case, as with measurement, the language of fundamental physical laws is at a loss to predict what alternative is selected or even describe the process of selection which, by definition, must occur outside the system being described.

That’s not just a matter of epistemic framing; it’s an ontological distinction — between a system as matter-in-motion and a system as meaningful, functional, or intentional.

So when we say life “lucked into codes,” we’re brushing up against the point where selection, memory, and meaning enter the scene. And it’s not clear — even in the most sophisticated systems models — that these can be accounted for within physicalism. Hence my interest in Deacon and Juarrero, who cover these kinds of issues. -

On PurposeThat’s why I said I think it’s a bad analogy. — T Clark

But is it an analogy at all? Isn’t it pointing to something real — not metaphorical, but actual?

Let me try a different analogy. One of the motivations for developing differential calculus — or at least one of its consequences — was its application to aiming artillery shells. This had a huge impact on warfare, military capability, and by extension, the political outcomes of military campaigns.

Now, if you’re an artillery officer, all you need to know is how to aim — and that’s what Newtonian physics helps with. Your tables and calculations tell you how to fire accurately. That’s one kind of aim — and it’s the kind physics is concerned with. And it made a huge difference!

But there’s also another level of aim: why you’re firing, why you joined the army, what the war is about — and none of that appears in the physics. Yet it’s still part of the aim. Physics models the trajectory, but not the reason.

In the same way, when Aristotle speaks of telos, he’s not always invoking a designer’s intention or a conscious goal. He’s pointing to the formative structure of things — the way they unfold, and what they tend toward in their becoming. The acorn doesn’t “intend” to be an oak tree, but neither is its development just accident and brute cause.

It’s not just a matter of aiming shells. The analogy extends to science itself. The amazing discoveries of modern science — calculus, thermodynamics, quantum mechanics — give us incredible power to manipulate and control. We can aim more accurately, build better tools, send probes to the outer planets.

But the question of what all this is for? That’s not a scientific question. It’s a philosophical, moral, or spiritual one. And it’s exactly the kind of question that the language of telos is trying to keep alive — not in a dogmatic sense, but in the sense that human beings and living systems don’t just happen, they mean.

It don't make sense, and you can't make peace. -

On PurposeA knife is designed and made by humans to cut — T Clark

But he also refers to natural things, acorns and foals. Elsewhere the distinction is made between artifacts and organisms, but here the distinction is not that important in this context - only that artifacts have purposes imposed by their designers while organisms have purposes that are intrinsic to them. -

On PurposeI get what you're saying, especially if telos is taken to mean forcing reality into the shape of our own agenda. But it doesn't necessarily mean that.

The Tao doesn’t strive, but it does flow, and whatever flows, has to flow somewhere. Water 'seeks the low places' not because it was told to, or because it suits human ends, but because of what it is. To notice that is not to impose a purpose, but to witness the natural pattern in things.

I’d agree that when teleology becomes a way of carving up nature to fit our needs or narratives, then it’s missing the point. But if it’s a way of attending to the inner coherence of things then it might be closer to reverence than to imposition.

Water benefits all things and does not compete. It stays in the lowly places which others despise. Thus it is close to the Tao. — Tao Te Ching, trs Gia-Fu Feng & Jane English

And it's not too far distant from the Aristotelian:

The word telos means something like purpose, or goal, or final end. According to Aristotle, everything has a purpose or final end. If we want to understand what something is, it must be understood in terms of that end ...Consider a knife. If you wanted to describe a knife, you would talk about its size, and its shape, and what it is made out of, among other things. But Aristotle believes that you would also, as part of your description, have to say that it is made to cut things. ...The knife’s purpose, or reason for existing, is to cut... ...This is true not only of things made by humans, but of plants and animals as well. If you were to fully describe an acorn, you would include in your description that it will become an oak tree in the natural course of things – so acorns too have a telos. — Aristotle, Politics, IEP -

Israel killing civilians in Gaza and the West BankAgree. It's appalling what is happening in Gaza and it's turning many people otherwise sympathetic to Israel (like me) against them. This has been a repeated pattern ever since the terrible decision to scuttle the UNRWA last year. It's an humanitarian catastrophe, no question.

-

On PurposeThis is what I dismiss as incoherent. We know that order does not simply emerge. The second law of thermodynamics supports this knowledge. Therefore we need to assume an "agency" of some sort as the cause of order — Metaphysician Undercover

I think the deeper philosophical issue here revolves around the problem of self-organisation — or what Aristotle might call self-motion. How can living systems arise from non-living matter? How can purposeful activity emerge in a world governed by entropy? How can something move or structure itself?

That’s precisely the question I’m exploring through Terrence Deacon’s Incomplete Nature. His project is to show how order can, in fact, emerge from thermodynamic chaos — not through external design or miraculous intervention, but through specific kinds of constraints and relational structures that arise in far-from-equilibrium systems. He calls this “emergent teleology,” and while it’s a naturalistic account, it isn’t reductionist in the usual sense.

But even if we accept Deacon’s account of how purposive structure can emerge naturally, there remains the deeper metaphysical question: whence those constraints?

That’s where something like the Cosmological Anthropic Principle strikes a chord — the idea that the fundamental constants (or constraints?) seem to lie within a very narrow range necessary for complex matter to exist and for life to arise. Whether one interprets that as evidence of design, necessity, or simply a selection effect is, of course, open to debate.

Or more to the point, it’s an open question — and I think that’s as it should be.

//ps - that linked video above is by Jeremy Sherman - he's a kind of Deacon acolyte, presents many of Deacon's ideas in informal videos on Youtube. Has a sense of humour and a quirky style -looks worth knowing about.// -

On Purpose:clap:

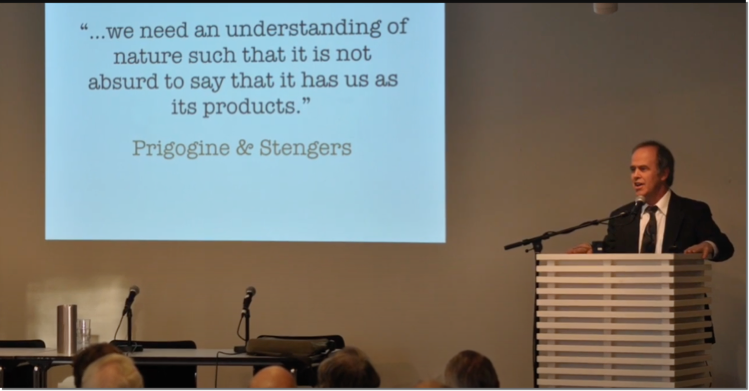

Screen grab of a lecture given by Terrence Deacon some time in the past. Excerpted from How Nature's Heirarchical Levels Really Emerge (video).

I had a thread before on how the Von-Nuemann-Wigner interpretation of quantum mechanics actually explains this — Count Timothy von Icarus

Forgotten that thread, thanks for mentioning! -

On PurposeYes, at first glance it does seem obvious that evolution has moved toward greater complexity and intelligence — after all, here we are! But what’s usually called ‘orthogenesis’ is actually rejected by mainstream biology, because it suggests that evolution has an inherent direction or goal - and according to theory, that’s not how natural selection works.

Evolutionary theory treats adaptations as responses to local conditions, not steps on a ladder. While some lineages have become more complex, others haven’t — many species have stayed much the same, or even simplified over time (think crocodiles).

The concern is that orthogenesis smuggles in telos without providing a mechanism ( :yikes: ) and so risks anthropocentrism — imagining that evolution was “aiming” at us. Darwinian theory never tires of assuring us that many species are much more successful, in evolutionary terms, on account of them having survived for far longer periods of time than h.sapiens (that, after all, being a measurable criterion, unlike ‘higher self awareness’.)

That’s exactly why the issue is relevant to the broader question of purpose. The mainstream rejection of orthogenesis isn’t just based on empirical considerations — it reflects a deep philosophical commitment within modern biology to explaining everything in terms of material and efficient causes (genes, mutations, selective pressures), while rejecting any appeal to formal or final causes as unscientific, a hangover from archaic patterns of thought. -

AssertionSalient essay on Philosophy Now at present Rescuing Mind from Machines, Vincent J. Carchidi.

-

On Purposein order for things to exist in specific ways, rather than absolute randomness, these ways must be designed, and the things somehow ordered to exist in these ways. — Metaphysician Undercover

I wouldn’t want it to be thought that the OP is advocating any form of intelligent design. That wasn’t the intention. The word 'design' almost always implies a designing agency, which is not what I mean by ‘purpose’. Rather, I’m pointing to the deeper philosophical issue of how order emerges from apparent chaos — a question that has animated metaphysics since the Presocratics.

I accept the basic, naturalistic account of evolutionary biology. Where I differ is in how it’s interpreted, and what meaning (if any) can be drawn from it. On one side are the ultra-Darwinists — figures like Daniel Dennett, Richard Dawkins, and Jacques Monod — who argue that life is a kind of biochemical fluke, a cascade of chance mutations filtered by the blind algorithm of natural selection (as outlined in Dennett's 'Darwin’s Dangerous Idea' and Monod's 'Chance and Necessity'). On the other side are proponents of intelligent design such as Michael Behe and Stephen Meyer ('Signature in the Cell').

I don’t subscribe to the Biblical creation narrative, though I respect its symbolic depth. Nor do I advocate a cosmic designer in the ID sense — though I also don’t think the ID theorists are entirely wrong in their intuition that something more is driving the process than blind mechanism.

I don’t want to wade too far into that controversy, which has produced a vast and contentious literature. But I am drawn to the idea of a naturalistic teleology, as Thomas Nagel very tentatively sketches in Mind and Cosmos — namely, that sentient beings are in some sense the cosmos become self-aware.

Accordingly, the one teleological principle I’m willing to defend — even if it’s heresy in mainstream biology — is orthogenesis: the idea that there has been, over evolutionary time, a real tendency toward greater awareness, self-consciousness, and intelligence. I don’t claim this as a comprehensive cosmology, but as a metaphysical intuition that can help accommodate diverse perspectives of the evolution of consciousness.

See also The Third Way. -

On PurposeThat is true, in a way, but it was because the thinkers of those times were schooled in, and trying to improve on (or supersede) the metaphysics and philosophy of their day.

Galileo, in particular, overthrew the antiquated system of Ptolemaic cosmology and Aristotelian physics - but then, he also leaned heavily on Plato, from whom he inherited the idea of ‘dianoia’ as the centrality of mathematical and geometrical knowledge. So these themes and ideas intermingle.

The cardinal difference between Galileo and his forbears was first the exclusion of the final cause - that for which something exists. That is what teleonomy or teleology are concerned with, and which the ‘new physics’ eliminated altogether. And second, the exclusive emphasis on what can be measured and quantified, which was absolutely crucial.

On the one hand, that opened the door to very much of what was to become modern science; but on the other, it tended to suggest the picture of the Universe and mankind as the product of blind physical causation, which became stock-in-trade for later scientific materialism.

Which is why Edmund Husserl said that Galileo’s genius ‘both reveals and conceals’. Reveals, because objectivity and quantitative methods yielded huge results; but conceals the "Lifeworld" (Lebenswelt). The core of Husserl's critique of modern philosophy is that Galileo's mathematical idealization conceals the pre-scientific, lived world of immediate experience (the "lifeworld") from which all scientific concepts ultimately arise. The lifeworld is the world as it is experienced by us in our everyday lives – with its qualitative perceptions, practical concerns, and subjective meanings. And modern science gave rise to this split (or ‘bifurcation’) between lived experience and scientific abstraction, which is very much what this thread is concerned with. -

On PurposeI read a lot of snippets, excerpts, and reviews, but of those books, I’ve only read parts. So I thought it a worthwhile aim, now I’m pretty well retired, to commit to reading these books in entirety. I’m working on the theme of ‘mental causation’.

-

On PurposeRestricting intention to human consciousness, such that only human actions can be understood as teleological, is a foundational, metaphysical mistake, which is common and prevalent in the modern western society. — Metaphysician Undercover

Exactly. Following Descartes, Enlightenment philosophy generally valorized the ego — the self-aware, reflective individual mind — as the seat of certainty and meaning. Husserl’s term egological is relevant here, because it names the modern presumption that consciousness means the kind of consciousness I am aware ot, usually understood introspectively. But this neglects more the more fundamenal forms of intentionality in life — what Jonas or Merleau-Ponty would recognize as the intentionality disclosed in embodied being. In other words, the mistake is not just empirical, but metaphysical: it misplaces the source of purposiveness by identifying it too narrowly with discursive, self-aware cognition (the ego). And an awful lot revolves around this mistake.

You're coming at it from a slightly different perspective, but I'm overall in agreement. (I'm exploring this topic through phenomology, which I've only begun reading the last couple of years. My current reading list is The Phenomenon of LIfe, Hans Jonas; The Embodied Mind, Varela, Thompson and Rosch; Mind in Life, Evan Thompson, Incomplete Nature, Terrence Deacon; and Dynamics in Action, Alice Juarrero all of which I hope to finish this year.)

It is not the case that "physics finds no purpose". It is intentionally designed, and employed, so as to avoid purpose. — Metaphysician Undercover

That's what the original post says!

So there is something intangible, or non-physical, about the contents of conscious experience, and it is within this intangible something, that purpose exists. Does that jibe? — Fire Ologist

:100: But a crucial fact is, the intangible and non-physical is not Descartes 'res cogitans', a thinking thing, which leads to the fallacious Cartesian dualism. I'll offer a passage here from a recent (but unsung) cognitive science book that I found very useful.

For the scientist, the universe consists of matter and incandescent plasma. These, however, are images invented by the human mind. Behind these images, and evoking them, are the constraints of nature that channel the scientist’s thinking and determine the outcomes of experiments. In fact, what we regard as the physical world is “physical” to us precisely in the sense that it acts in opposition to our will and constrains our actions. The aspect of the universe that resists our push and demands muscular effort on our part is what we consider to be “physical”. On the other hand, since sensation and thought don’t require overcoming any physical resistance, we consider them to be outside of material reality. — Pinter, Charles. Mind and the Cosmic Order: How the Mind Creates the Features & Structure of All Things, and Why this Insight Transforms Physics (p. 6). Kindle Edition.

This beautifully illustrates that even the concept of ‘physical reality’ is not independent of subjective orientation — it's already intentional, already laden with the phenomenological structure of purpose and resistance (and this, even though Pinter's not writing from an explictly phenomenological perspective). This embodiedness is precisely what the "egological" framework doesn't see, as it has already reduced objects to abstractions.

I don’t quite follow how meaning was left behind for the sake of predictive accuracy. Are you saying, scientists saw no need to wonder what the bat (for instance) is subjectively experiencing when they could make predictive models about bat behaviors that need not include any such considerations? — Fire Ologist

The "great abstraction" referred to in the original post isn’t about biology, but about physics — specifically, the revolution in natural philosophy during the 17th century that led to a mechanistic, mathematically formalised view of nature. This model prioritized predictive accuracy over interpretive meaning, redefining what counted as knowledge by bracketing off subjective or qualitative aspects of experience altogether.

Interestingly, Immanuel Kant himself expressed doubts about whether biology, in this mechanistic framework, could ever qualify as a true science:

Since only external forces can cause bodies to change, and since no ‘external forces’ are involved in the self-organization of organisms, Kant reasoned that the self-organization of nature ‘has nothing analogous to any causality known to us.’ — Alicia Juarrero, Dynamics in Action

In other words, because the physical sciences were built around time-reversible laws (like Newtonian mechanics), they couldn’t easily account for the purposive, self-organizing activity of living systems — which unfold over time and exhibit goal-directed behavior.

And indeed, biology didn’t fully establish itself as a predictive science until Darwin’s Origin of Species and later the discovery of genetic mechanisms. Before that, it was largely classificatory — a science of kinds, not causes. But even today, there remains a live tension between the mechanistic framework inherited from physics and the teleological character of life. Hence the argument that purposiveness, which was deliberately set aside in the development of modern science, must now be acknowledged — not as epiphemonenal but as central. -

On PurposeThe point isn’t that purpose is a substance-like feature found in some things (like organisms) and absent in others (like rocks). That’s still thinking in terms of objective, observable properties, which is the default stance of positivism. But from a phenomenological stance, purpose isn’t an object in the world. It shows itself through meaningful activity. It’s not a ‘thing’ to be pointed to, but something intuited in the enactment of life itself. This is why Wittgenstein says, ‘the sense of the world must lie outside the world’ (Tractatus 6.41): the kind of sense we’re talking about here—teleological, existential—isn’t in the world as one more fact among others. It’s how the world shows up as meaningful to a being who acts (and being is always in action.)

-

On PurposeWe see purpose or agency in the data collected by observing animal behavior. Are you claiming there is purpose or agency there in the inorganic even though we cannot detect it? If you are claiming that, then on what grounds? — Janus

The sense of the world must lie outside the world. In the world everything is as it is, and everything happens as it does happen: in it no value exists—and if it did exist, it would have no value. — TLP 641 -

On PurposeIt's a judgement based on critical thought. The human notion of purpose presupposes agency. and agency presupposes perception/ experience. If the universe as a whole has no agency, no perception/ experience then how could it have a purpose? — Janus

The ‘universe as a whole’ is the subject of scientific cosmology. It’s what is examined through the astounding technology of the Hubble, James Webb and now Vera Rubin observatories. Of course you won’t see anything like purpose or agency in the data that these instruments collect - but as I said, this is red herring. As I said, scientific method itself brackets out or disregards those kinds of considerations. But to refer back to the OP ‘the familiar claim that the universe is meaningless begins to look suspicious. It isn’t so much a conclusion reached by science, but a background assumption—one built into the methodology from the outset. The exclusion of purpose was never, and in fact could never be, empirically demonstrated; it was simply excluded as a factor in the kind of explanations physics was intended to provide. Meaning was left behind for the sake of predictive accuracy and control in specific conditions.

That this bracketing was useful—indeed revolutionary—is not in doubt. But the further move, so often taken for granted in modern discourse, is the assertion that because physics finds no purpose, the universe therefore has none. This is not science speaking, but metaphysics ventriloquizing through the authority of science. It is a philosophical sleight of hand that confuses methodological silence for ontological negation.’ And you continually pull on that to justify your claims that whatever can’t be known by way of science is not a legitimate subject for philosophy.

We think of human behavior as intentional. We also think of some animal behavior as intentional, but it seems a stretch to call the behavior of simple organism, or even plants or fungi, intentional. You agree that the inorganic universe is not intentional or purposeful, and if the vast bulk of existence is inorganic, then how do you reconcile that? — Janus

I’m interested in a perspective based on phenomenology - that the appearance of organisms IS the appearance of intentionality. It is how intentionality manifests. It’s not panpsychism, because I’m not saying that consciousness is somehow implicit in all matter. The fact that inorganic matter is not intentional in itself is not particularly relevant to that.

And yet, no doubt, this "being challenged by science" is an objective process. — 180 Proof

Perhaps - but, ironically, the whole question of the mind-independence of the fundamental aspects of nature has been thrown into question by this objective process. That’s what the Einstein-Bohr debates were about - Einstein the staunch realist, ‘the world is the way it is no matter what we think or see’ vs Bohr ‘no phenomenon is a real phenomenon until it is an observed phenomenon.’ -

On PurposeOf course, but the sense that the universe is, in Bertrand Russell’s words, ‘the meaningless outcome of the collocation of atoms’ is very much a product of Enlightment and post-Enlightenment rationalism. (And it’s not for nothing that Plato wanted all Democritus’ books burned ;-) )

To briefly recap the OP

- Modernity tends to view the universe as basically meaningless, although individuals and cultures may project concepts of meaning on it.

- But on the level of lived existence, organic life is animated by purpose, driven by the will to survive.

- Phenomenology has re-conceived intentionality as something much broader than conscious intention, instead identifying it as an aspect of the will to survive (re Hans Jonas The Phenomenon of Life)

- Enlightenment science divided the universe into the primary and secondary attributes of matter, roughly corresponding with the objective and subjective domains, respectively.

- A major aspect of early modern science was the abandonment of the idea of ‘telos’ associated with Aristotelian physics, which superseded by Galileo’s then-new physics.

- In this model, meaning, purpose and values are identified as being subjective and the universe said to be devoid of ‘telos’, however this view is itself a consequence of the perspective required by physics, now brought to bear on the life as a whole. This is the origin of physicalism.

- Biology is a different discipline to physics, and accordingly telos has had to be re-introduced through the neologism ‘teleonomy’ which describes the apparently-purposeful activities of organic life.

- Finally, unlike in early modern physics, current physics itself has now been obliged to take the context of its observations into account because of the ‘observer problem’ in quantum physics.

Meaning that the stark object-subject divide that characterised modern thought is now being challenged by science itself.

Wayfarer

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum