Comments

-

Donald HoffmanRational consciousness can reflect on that. I’m trying for the bare-bones definition.

-

Donald HoffmanAssembled throng of philosophical worthies: I think I have a simple definition of consciousness (which i might as well put here as start a thread).

>>Consciousness is the capacity for experience<<

What do we think? -

Evidence of Consciousness Surviving the BodyObviously, he's an authority on what he does know - which is physics after the free miracle — AmadeusD

What’s the ‘free miracle’? -

Evidence of Consciousness Surviving the BodyI posted a sketch of a non-materialist metaphysic a few posts above. As I’ve noted, I think Stevenson’s research on children who claim to remember previous lives and the corroborating information is noteworthy but I understand from previous conversations that you reject it.

-

Donald HoffmanAll well and good - but that also embodies a perspective, somewhere outside both the mind and the world. A mental picture, if you like, or image of the self-and-world.

— Wayfarer

I'm not sure what you mean here. — Apustimelogist

I will try and explain again. You said:

I think its more about trying to be as clear as possible. I think its about the idea that there is an objective way the world is and the mind is embedded within that. It is a slave to other parts of the objective world that undergird it, not independent from those things; the evidence relating our minds to neurons and physics is overwhelming. There is no harm trying to clarify that relationship as precisely as possible. — Apustimelogist

All well and good, but I'm referring to the sense in which even this realist view is itself a mental construction. To form that picture, you have to adopt a perspective that is outside of both and that contains an image or concept of both 'the world' and 'the mind'. I think we're in agreement on that.

I suppose I should acknowledge my agenda, so to speak. I'm resistant to the kind of realist view which subordinates the mind to the scientific perspective itself, which seeks to explain philosophical issues through a scientific perspective. And why? Because philosophy has an inextricably qualitative dimension which eludes a strictly objective analysis, but which is nevertheless fundamental to our well-being. The scientific image of man often tends to deprecate or belittle that.

As for this somewhat mysterious issue of 'seeing things as they are' - I believe that that is what is conveyed by the faculty of 'sagacity'. The archetypical sage is able to arrive at a holistic understanding of nature of being, not necessarily in conflict with the scientific image, but also not necessarily disclosed by science itself, although scientists do describe moments of insight which correspond with that.

And speaking of sages, here I'm reminded of several passages from Erwin Schrodinger's 'Nature and the Greeks':

I am very astonished that the scientific picture of the real world around me is deficient. It gives a lot of factual information, puts all our experience in a magnificently consistent order, but it is ghastly silent about all and sundry that is really near to our heart, that really matters to us. It cannot tell us a word about red and blue, bitter and sweet, physical pain and physical delight; it knows nothing of beautiful and ugly, good or bad, God and eternity. ...

We do not belong to this material world that science constructs for us. We are not in it; we are outside. We are only spectators. The reason why we believe that we are in it, that we belong to the picture, is that our bodies are in the picture. Our bodies belong to it. Not only my own body, but those of my friends, also of my dog and cat and horse, and of all the other people and animals. And this is my only means of communicating with them. ...

The observing mind is not a physical system, it cannot interact with any physical system. And it might be better to reserve the term "subject" for the observing mind. … For the subject, if anything, is the thing that senses and thinks. Sensations and thoughts do not belong to the "world of energy." ...

The scientific world-picture vouchsafes a very complete understanding of all that happens — it makes it just a little too understandable. It allows you to imagine the total display as that of a mechanical clockwork which, for all that science knows, could go on just the same as it does, without there being consciousness, will, endeavor, pain and delight and responsibility connected with it — though they actually are. And the reason for this disconcerting situation is just this: that for the purpose of constructing the picture of the external world, we have used the greatly simplifying device of cutting our own personality out, removing it; hence it is gone, it has evaporated, it is ostensibly not needed.

In particular, and most importantly, this is the reason why the scientific worldview contains of itself no ethical values, no esthetical values, not a word about our own ultimate scope or destination, and no God, if you please. Whence came I and whither go I? -

Evidence of Consciousness Surviving the BodyAs for Lommel, again, you never posted any of his evidence or argumentation. For all I know, he's a quack. I'm not going to take time out of my day to read an entire book, as I'm not arguing for consciousness existing outside of the body. If he has good arguments, post them — Philosophim

Non-Local Consciousness, Pim Van Lommel. It's a kind of summary of his research. He notes this anecdote from a nurse:

'During night shift an ambulance brings in a 44-year old cyanotic, comatose man into the coronary care unit. He was found in coma about 30 minutes before in a meadow. When we go to intubate the patient, he turns out to have dentures in his mouth. I remove these upper dentures and put them onto the ‘crash cart.’ After about an hour and a half the patient has sufficient heart rhythm and blood pressure, but he is still ventilated and intubated, and he is still comatose. He is transferred to the intensive care unit to continue the necessary artificial respiration. Only after more than a week do I meet again with the patient, who is by now back on the cardiac ward. The moment he sees me he says: ‘O, that nurse knows where my dentures are.’ I am very, very surprised. Then the patient elucidates: ‘You were there when I was brought into hospital and you took my dentures out of my mouth and put them onto that cart, it had all these bottles on it and there was this sliding drawer underneath, and there you put my teeth.’ I was especially amazed because I remembered this happening while the man was in deep coma and in the process of CPR. It appeared that the man had seen himself lying in bed, that he had perceived from above how nurses and doctors had been busy with the CPR. He was also able to describe correctly and in detail the small room in which he had been resuscitated as well as the appearance of those present like myself.'

Although it is clear that replication of this kind of event in controlled laboratory conditions might be challenging, but they are often reported in the literature. (The paper discusses attempts to corroborate this kind of evidence by placing objects in proximity of ICUs where such procedures are carried out, but with no conclusive results.)

He has an entry on Wikipedia also. -

Evidence of Consciousness Surviving the BodyYou keep taking the time to treat me like I'm an idiot, and I keep proving you wrong. Is this ever going to change? — Philosophim

I don’t believe I did that, nor did I wish to imply it. You can't have a conversation you don't like without falling into ad hominems. If I've been critical, it's because of what I see as the presuppositions you bring to bear, for example:

Currently the hypothesis, "Our consciousness does not survive death," has been confirmed in applicable tests. You'll need to show me actual tests that passed peer review, and can be repeated that show our consciousness exists beyond death. To my mind, there are none, but I am open to read if you cite one. — Philosophim

Where the obvious difficulty is that of obtaining an objective validation of a subjective state of being and which only occurs in extreme conditions. Would, for instance, the peer review group also had to have had NDE's? The 'replication crisis' in psychology is severe enough even for much more quotidian matters. Myself, I don't really see how the claim that there can be a state beyond physical death is ever going to be scientifically validated, although I believe there are research programs underway to do that.

I brought up Ian Stevenson's research into children with past-life memories, because it's obviously a more realistic source of objective data than are NDE's. Reason being, the subject children will make claims about his or her remembered previous identity, and those claims can be subjected to documentary evidence and witness testimony. And I have read it - I did take his two-volume Where Reincarnation and Biology Intersect out of the library, and read large parts of it (although it's two very large volumes and much of it worded in the dry technical terminology of medical literature). But it is the consequence of the examination of several thousand such cases. It's easy to dismiss Stevenson as a crank or charlatan but he did amass a considerable amount of data which I happen to think is a more empirically reliable source of data than NDE testimonies.

I also laid out a sketch of an alternative metaphysic, within which the idea of continuity from life-to-life might be considered plausible, to which you didn't respond.

I have no problem with his pointing out the fact scientism can't explain itself, but it would be more reasonable to point toward the need for a metaphysical model that fills the gap he identified. — Relativist

You make many solid points there, and I'll need to do some more reading, obviously. I will own up that the reason for my hostility to Armstrong, and he was the professor of philosophy were I was an undergrad, was that I believe that materialist theories of mind are incorrect in principle. But I also recognise that he was a brilliant thinker and that to get into the ring with him would take someone with a lot better skills than myself. I don't believe your responses really do adequately address the challenges of modern physics, but I know better than to try and pursue that line of argument. Anyway, many points to consider there and I appreciate that. -

Donald HoffmanI think its about the idea that there is an objective way the world is and the mind is embedded within that. — Apustimelogist

Further to this point. The idea I keep coming back to is that we instinctively accept that mind is 'the product of' matter. The causal chain which supports this contention is ostensibly that of the neo-darwinian synthesis, which proposes that the brain evolved through the aeons to the point where it is able to generate the mind-states that comprise experience. So, mind as a product of matter - the essential contention of materialist theory of mind.

But what we understand as physical facts are in reality dependent on the mind. That doesn't mean we can generate our own facts gratuitously or casually - I often quote the maxim, 'everyone has a right to their own opinions, but not to their own facts'. And I think that's true. There is a massive and ever-growing body of objective facts. But again, I argue that objective facts are invariably surrounded and supported by an irreducibly subjective or inter-subjective framework of ideas, within which they are meaningful, and one which the empiricist understanding of 'mind-indendent nature' doesn't acknowledge.

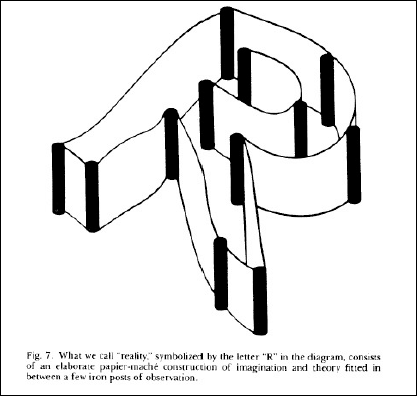

Hence this graphic from physicist John Wheeler:

The caption reads, ‘what we consider to be ‘reality’, symbolised by the letter R in the diagram, consists of an elaborate paper maché construction of imagination and theory fitted between a few iron posts of observation’ (from his paper Law without Law.)

This is also suggested by a paper on a physics experiment known as Wigner's Friend which creates an experimental setup that calls into question that subjects all see different perspectives on the same thing. This experiment shows that two subjects can see different results that are both supposedly 'objectively true'. So it's touted as 'calling objective reality into question' although that needs to be carefully interpreted. It doesn't mean 'anything goes' or that total relativism reigns. As noted, there's indubitably an enormous range of objective facts about which you or I can be right or wrong. But there is also a subjective element which is generally overlooked by 'objectivising' tendencies of today's scientific culture.

Chapter 6 in Hoffman's book deals with a lot of this kind of material. -

Donald HoffmanI think its about the idea that there is an objective way the world is and the mind is embedded within that. — Apustimelogist

All well and good - but that also embodies a perspective, somewhere outside both the mind and the world. A mental picture, if you like, or image of the self-and-world.

What Hoffman et al are doing is actually de-constructing that sense - which is what you yourself said in an earlier post! I'm slogging through his book, and there's a lot of data from cognitive science and evolutionary biology. But through that he's arriving at the counter-intuitive insight that the brain/mind in essence constructs the world which we reflexively believe is 'out there'. And there's a lot of pushback on that point, because it undermines our instinctive sense of what's real. Hoffman himself says in an interview that he finds it difficult to really accept the implications of his own theory!

the evidence relating our minds to neurons and physics is overwhelming. — Apustimelogist

But is it? Who are the case studies for that view? I know of a clique of academic philosophers who are customarily associated with pretty hard-edged materialist theories of mind: they are P & P Churchland, a married couple who are both academics, Alex Rosenberg, and the late Daniel Dennett are frequently mentioned in this regard. They were very much the target of David Chalmer's argument, and I think the argument succeeds. (There are also naturalist philosophers of mind, like John Searle, who are critical of the materialists, it was Searle who dubbed Dennett's book Consciousness Explained as 'Consciousness Explained Away'.)

But going back to the point I made above, brains and neurons and physics are themselves mental constructs, in some fundamental sense. It doesn't mean they're 'all in the mind' in an obvious or gross kind of way, but that the mind (or the observer) imputes meaning and value to the terminology and principles of those sciences. So there is a fundamentally mental or subjective element to those theories, which is never disclosed, because they're not critically aware of them. They impute to the objective and external what is really being generated by the mind. So there's a vicious circle at back of it, the attempt for science to explain itself. Kant was aware of that in a way the above philosophers can never be.

Similarly, science cannot tell us anything about the fundamental "intrinsic nature" of things beyond experience. — Apustimelogist

But it's a question philosophy must grapple with. So if we continue to operate within the boundaries of empiricism it's fair to question whether we really are engaging with philosophy.

I don't need to know what is happening on the slopes of Mount Everest right now to believe there are some definite events happening on the slopes of Mount Everest right now. — Apustimelogist

By bringing them to mind! You can't say anything about them, unless you do that. -

Evidence of Consciousness Surviving the BodyThat science is a rational form of inquiry doesn't require a supernaturalist metaphysics to justify; the "causal regularities" he refers to can be accounted for as laws of nature (relations between universals). — Relativist

But, are universals themselves physical? I know David Armstrong says they are, but I think his is a revisionist account of universals shoehorned into a materialist framework and undermined by science itself. (For example, the Copenhagen interpretation suggests that quantum entities do not have definite properties until they are observed, which conflicts with Armstrong's view that properties (or universals) exist independently of perception and measurement). And the ontological status of 'the laws of nature', and why the Universe has just these laws and not some other, is also neither a scientific question nor something that can be adjuticated by physics.

In the SEP entry on Physicalism, cited above, there is a section on 'the problem of abstracta' which is precisely that numbers and the like are not material in nature - and yet they are also basic to the success of the mathematical physics which underpins a great deal of science. There is still controversy in philosophy of mathematics as to whether the Platonist view is the correct one, and Platonism maintains that number is real but immaterial (which is why it is controversial.) So the ontological status of universals and abstracta is far from a settled question.

So:

"For scientific inquiry itself rests on a number of philosophical assumptions: that there is an objective world external to the minds of scientists; that this world is governed by causal regularities; that the human intellect can uncover and accurately describe these regularities; and so forth. Since science presupposes these things, it cannot attempt to justify them without arguing in a circle." ~ Edward Feser — Relativist

I think this is quite true, and will often defend this argument. The succinct way of expressing it is that 'naturalism assumes nature' - it starts with the apparently self-evident fact of the existence of the empirical world, to be studied by science. But again, that apparently innocuous assumption always entails an implicit metaphysics and epistemology. An example is the status of objectivity: I've argued at length in another thread that objectivity is itself reliant on there being a subject to whom objects appear (per Kant). The fact that communities of subjects see the same sets of objects doesn't undermine that. And then, there's the observer problem in physics, already noted, concerning the objects of physics itself which are essentially abstractions in the first place.

So I think Feser is quite justified in that claim. -

Donald HoffmanAs you know, many of us don't think there is any problem to face up to. — T Clark

Not seeing a problem does not amount to grounds for dismissing it. -

Evidence of Consciousness Surviving the BodyThat's not phyicalism, it's scientism — Relativist

They’re nearly always joined at the hip. Are there any advocates for ‘scientism’ who do not hold to physicalism? We look to science as the arbiter of what is real, and science is best equipped to deal with the objectively measurable and inferences grounded against objective measurement. So I think Feser’s metal-detector analogy is perfectly apt, especially in a discussion such as this one. We are pre-disposed to a metaphysical view that is in concordance with science, hence the constant eye-rolling and exasperation when mention is made of researchers who question physicalism. -

Donald HoffmanNor was I aware there was a special authority required to make philosophical claims. Maybe we should be verifying everyone's philosopher cards here. — hypericin

An important part of philosophy is criticism, especially of poor analogies and misapplied categories.

People want to hold onto words like "agency" and "rationality" and "subjectivity" without analyzing what they mean because they fear it deconstructs their humanity. — Apustimelogist

And I see you as reflexively hanging on to something like scientism, the belief that philosophy must always defer to the white lab coat of scientific authority. To ‘deconstruct’ the mind is to analyse it in terms of something else, or of its constituent elements - the impossibility of which is precisely the point of Chalmer’s ‘facing up to the problem of consciousness’ article. I don’t want to thrash all that out again, but nothing you’re saying indicates that you are facing up to that problem. -

Evidence of Consciousness Surviving the BodyMust they be hallucinatory? I don't know. I never claimed that. Did you read our discussion and my points, or are you only taking a later post? — Philosophim

Never?

If a bunch of people have a hallucination, no one doubts they have a hallucination. But the fact that multiple people have a hallucination is not an argument for that hallucination being real. — Philosophim

The point about Van Lommel and Ian Stephenson is simply to indicate that large data sets exist, that researches have wrestled with the question as to whether nde’s and past-life memories have any basis in reality. I could take the time to reproduce some of their examples for discussion, but I have a fair idea of what the response would be, so I’m not going to bother. -

Donald HoffmanIs it a mistake to say that hearts pump blood? — hypericin

Not in the context of physiology and anatomy, but it’s not an apt comparison with cognition and judgement. It appeals to the supposed authority of neuroscience to make philosophical claims about the mind - very different thing to the circulation of blood. -

Evidence of Consciousness Surviving the BodyI have an issue with the expression 'consciousness surviving the body'. I think it's inherently self-contradictory insofar as consciousness is generally understood to be an attribute of physical organisms and is generally not perceived in any other context. But then, I also think the tendency to see this question in these terms is due to the framework in which this is understood.

There was an opinion piece published in Scientific American, by physicist Sean Carroll, called Physics and the Immortality of the Soul. Carroll argues that belief in any kind of life after death is equivalent to the belief that the Moon is made from green cheese - that is to say, a ridiculous idea.

But such an assertion is made because of the presuppositions that he brings to the question, the perspective through which he views it. In other words, he depicts the issue in such a way that it would indeed be ridiculous to believe it.

Carroll says:

Claims that some form of consciousness persists after our bodies die and decay into their constituent atoms face one huge, insuperable obstacle: the laws of physics underlying everyday life are completely understood, and there’s no way within those laws to allow for the information stored in our brains to persist after we die. If you claim that some form of soul persists beyond death, what particles is that soul made of? What forces are holding it together? How does it interact with ordinary matter?

I can think of an answer to this question, which is that the soul is not 'made of particles' and that the idea that the soul is 'made of particles' is not at all characteristic of what is meant by the term 'soul'. (Some of the ancient Stoics and Hindus did believe in a form of subtle matter, but I'll leave that aside. And I'll also leave aside the implicit hubris.)

First recall that the Greek term interpreted as 'soul' was 'psuche' or 'psyche' which is of course still with us as a form of a word for 'mind' (preserved in 'psychology'). But I think the soul could be better conceived in terms of a field that acts as an organising principle - analogous to the physical and magnetic fields that were discovered during the 19th century, that were found to be fundamental in the behaviour of particles. This is not to say that the soul is a field, but that the field analogy might be a better metaphor than particulate matter. (And bearing in mind, in Aristotle, the soul is given as 'the form of the body', where 'form' is akin to 'animating principle'. It is not 'the shape' nor is it conceived of as a separable entity.)

Morphic Fields

So - just as magnetic fields organise iron filings into predictable shapes, so too might a biological field effect be responsible for the general form and the persistence of particular attributes of an organism. The question is, is there any evidence of such 'biological fields'?

Well, the existence of 'morphic fields' is the brainchild of Rupert Sheldrake, the 'scientific heretic' who claims that:

Morphic resonance is the influence of previous structures of activity on subsequent similar structures of activity organized by morphic fields. It enables memories to pass across both space and time from the past. The greater the similarity, the greater the influence of morphic resonance. What this means is that all self-organizing systems, such as molecules, crystals, cells, plants, animals and animal societies, have a collective memory on which each individual draws and to which it contributes. In its most general sense this hypothesis implies that the so-called laws of nature are more like habits.

As the morphic field is capable of storing and transmitting remembered information, then 'the soul' could be conceived in such terms. The morphic field does, at the very least, provide an explanatory metaphor for such persistence. (This also resonates with the idea of the collective unconscious (Jung) and the alayavijnana, the ‘storehouse consciousness’ of Mahāyāna Buddhism. Meaning that the soul or psyche is analogous to a standing wave or whirlpool structure in such a medium, the 'cittasantana' or mind-stream of Mahāyāna Buddhism. )

Children with Past-Life Memories

But what, then, is the evidence for such effects in respect to 'life after death'? As mentioned previously a researcher by the name of Ian Stevenson assembled a body of data on children with recall of previous lives. Stevenson's data collection method comprised the methodical documentation arising from the seeking out and recording of a child’s purported past-life recollections. Then he identified from journals, birth-and-death records, and witness accounts, the deceased person the child supposedly remembered, and attempted to validate the facts from those sources that matched the child’s memory. Another Scientific American opinion piece notes that Stevenson even matched birthmarks and birth defects on his child subjects with wounds on the remembered deceased that could be verified by medical records.

On the back of the head of a little boy in Thailand was a small, round puckered birthmark, and at the front was a larger, irregular birthmark, resembling the entry and exit wounds of a bullet; Stevenson had already confirmed the details of the boy’s statements about the life of a man who’d been shot in the head from behind with a rifle, so that seemed to fit. And a child in India who said he remembered the life of boy who’d lost the fingers of his right hand in a fodder-chopping machine mishap was born with boneless stubs for fingers on his right hand only. This type of “unilateral brachydactyly” is so rare, Stevenson pointed out, that he couldn’t find a single medical publication of another case. — Are We Sceptics Just Cynics?

Carroll goes on in his essay to say that 'Everything we know about quantum field theory (QFT) says that there aren’t any sensible answers to these questions (about the persistence of consciousness)'. However, that springs from his starting assumption that 'the soul' must be something physical, which, again, arises from the presumption that everything is physical, or reducible to physics. In other words, it is directly entailed by his belief in the exhaustiveness of physics with respect to the description of what is real.

He then says 'Believing in life after death, to put it mildly, requires physics beyond the Standard Model. Most importantly, we need some way for that "new physics" to interact with the atoms that we do have.' However, even in ordinary accounts of 'mind-body' medicine, it is clear that mind can have physical consequences and effects on the body. This is the case with, for example, psychosomatic medicine and the placebo effect, but there are other examples.

He finishes by observing:

Very roughly speaking, when most people think about an immaterial soul that persists after death, they have in mind some sort of blob of spirit energy that takes up residence near our brain, and drives around our body like a soccer mom driving an SUV.

But that is not what 'most people have in mind'. As mentioned above, the idea of a self that transmigrates life to life is condemned in no uncertain terms in Buddhist scriptures, which do otherwise accept the reality of re-birth. But that is what physicalism ‘has in mind’ because it's the only way to conceive of something if you think that all that is real is matter.. If you start from the understanding that 'everything is physical', then this will indeed dictate the way you think about it. And while it may be true that there is no such 'blob' as Carroll describes, that is not what the 'soul' is; but what it might be, is something that can't be understood in the terms of Carroll's ontological presuppositions.

So, I myself don’t much like the terminology of ‘consciousness surviving death’, especially when ‘consciousness’ is defined in terms of an attribute of conscious beings. The fact that we feel compelled to conceive it that way is a consequence of the ‘objectifying’ tendency which is deeply rooted in the way we think about it. But very subtle questions of identify, metaphysics and epistemology underlie this issue.

Physicalism is, in slogan form, the thesis that everything is physical.... The general idea is that the nature of the actual world (i.e. the universe and everything in it) conforms to a certain condition, the condition of being physical. — Stanford Encylopedia of Philosophy, Physicalism -

Missing features, bugs, questions about how to do stuffgreat work man and we're all in your debt. :pray:

-

Missing features, bugs, questions about how to do stuffI figured it was a capacity problem. I wonder if there's a way of deleting draft comments by age. I know it saves all mine and they go back years. Every so often I go and delete a few but it's like pulling weeds.

-

Donald HoffmanI bought the Kindle edition for a lot less than that. Anyway, never mind, I won't try and sell it. I cover some of the details in the mind-created world thread.

-

Donald Hoffmanlumpen idealism. — apokrisis

I know an oxymoron when I see it.

You should look into Pinter's book. The reason I say it will be unsung, is because it was a labour of love on his part, he's a mathematics emeritus - now deceased - who in the last part of his very long life devoted considerable energy to cognitive science. But as he's not published in that field - all his previous books were on algebra and the like, JGill knows them - nobody in the field paid much attention to his Mind and the Cosmic Order, which I think is a shame. He doesn't push an idealist barrow, although I think his book provides some grounds for it. I don't think you would see it as incompatible with your biosemiotic philosophy. -

US Election 2024 (All general discussion)For a year or more, Democrats have been facing the dim prospect of keeping a historically old, historically unpopular incumbent in the White House. Resignation and hopelessness were Joe Biden’s real running mates. Then with that debate performance, it became clear to the most significant forces in the party that Biden simply could not win in November. Amid a rising pressure campaign and worsening polls, the president yielded and stepped down from his reelection bid.

It was as if the Democratic Party had rediscovered a power that it had never used, maybe never even been aware of; far from being a “coup,” it was the execution of the essential task of a political party: The use of formal and informal power to protect itself from political disaster.

Within a matter of two weeks, voters now faced a reality that had previously seemed impossible: “You don’t want to vote for Biden or Trump? Now you don’t have to! You want change? Here she is!” The flood of money, volunteers and crowds toward Harris testifies to the power of that sentiment. — Trump’s Crucial Power Has Been Neutralized

I said months ago that the replacement of Biden would completely changed the dynamic of the election - and it has. That’s why MAGA is kvetching about it, waxing sentimental for ‘poor old Joe’, when really all they wanted was an easybeat. -

Donald HoffmanYeah, well. I'm not all in on him, but still positively disposed. But I still think Mind and the Cosmic Order, Charles S Pinter, is a superior book covering very similar territory, and much more philosophically coherent. (And probably, sadly, forever unsung.)

-

Donald HoffmanThe neurons of the central nervous system terminate in mechanical switches — apokrisis

Despite the appeals to semiosis, signs and meaning, C S Peirce, you default to physicalism where it counts. Who or what presses these buttons, and to what end? That is a philosophical problem, not a question of bio-engineering.

His account often mentions, and is compatible with, QBism, which is not the realist theory in the sense that you insist on.

he has a book to sell, a name to make. There is a social incentive for him to angle his story so as to attract the audience he does. — apokrisis

And that's a blatant ad hom, he's just a shabby opportunist. There are a lot of things I question about his account, but that's not one. -

Donald Hoffmanif the scope of knowledge is defined in purely objective terms. But then, you tend to naturally look at philosophical questions through a scientific perspective, don't you?

— Wayfarer

What are the alternatives? I genuinely can't conceive of any off the top of my head. — Apustimelogist

Right - my point exactly. I think the assumption that objectivity defines the scope of knowledge is what is at issue. I'm not taking a shot at you in particular, I think this is very much the assumed background of the culture we live in. But I also think it's philosophy's task to be critical of that. -

Evidence of Consciousness Surviving the BodyBut if you just figured out that some observed phenomenon is not possible to explain; then you'd need to believe in dualism. — god must be atheist

Physicalism could be falsified by clear evidence of something nonphysical existing. — Relativist

Ed Feser gives the example of the metal detector. Defenders of physicalism will say:

1. The predictive power and technological applications of physics are unparalleled by those of any other purported source of knowledge.

2. Therefore what physics reveals to us is all that is real.

Which can be compared with:

1. Metal detectors have had far greater success in finding coins and other metallic objects in more places than any other method has.

2. Therefore what metal detectors reveal to us (coins and other metallic objects) is all that is real.

Now metal detectors are specifically adapted to those aspects of the natural world susceptible of detection via electromagnetic means. But however well they perform this task -- indeed, even if they succeeded on every single occasion they were deployed -- it simply wouldn’t follow for a moment that there are no aspects of the natural world other than the ones they are sensitive to - - that there are no things other than metal objects.

Similarly, what physics does -- and there is no doubt that it does it brilliantly -- is to capture just those aspects of the natural world susceptible of the mathematical modeling and detection that makes precise prediction and technological application possible. But here too, it simply doesn’t follow for a moment that there are no other aspects of the natural world. (And it might also be noted that despite the spectacular success of mathematical physics, there are many profound anomalies and conundrums thrown up by it.)

As I mentioned above, until the middle of the 19thc nobody knew that there were electromagnetic fields. Since the discovery of Maxwell's field equations and its integration with physics, these are now understood to be even more basic than sub-atomic particles- before then, they weren't even considered.

But what if there were biological fields, which could only be detected by organisms? No matter how sensitive and how accurate your metal detection or particle-accelerator instruments were, these would be invisible to them, outside the scope (the 'boundary conditions') of your instrumentation.

Furthermore, all this is taking place in a cultural context which has inherited the dualism of 'mind and matter' from early modern science. So against that backdrop, to demonstrate the existence of something which was not physical, would presumably to identify and isolate the mysterious 'res cogitans', the 'thinking substance' which Descartes identified as 'consciousness'. But this gives rise to a whole set of interlocking problems, starting with the so-called 'interaction problem'. And that's maybe because the whole model, which again is foundational to the modern world, has radical deficiencies.

So once these kinds of factors are considered, different perspectives become available. It means going back and re-examining the pathway by which the conclusion that 'the universe is solely physical' was arrived at. It sounds daunting, but it's eminently achievable. -

Evidence of Consciousness Surviving the BodyNo, that's an appeal to authority fallacy. — Philosophim

Appealing to data in response to a claim is not a fallacy. If you claim that near death experiences must be hallucinatory, then evidence to the contrary ought to be considered also, and Pim Van Lommel's books are a source of that evidence. I've gone back and looked at the first page again - after 7 years :yikes: - Sam presents his arguments carefully enough, and of course it is right and proper that they're challenged, but there is testimonial evidence - and what other kind could there be for this subject?

What I'm getting at, is not the belief that these experiences have no basis in reality, but why they can't have any basis in reality. I think there's a mindset to disprove or deny any possibility of them being real. I think that's the question that ought to be explored. But your responses are underwritten by the conviction that they could not be real. Let's discuss why they couldn't be, what would have to be the case for such experiences to be real.

So, I disagree with your carte blanche dismissal of what Sam has been presenting. I think it's more likely that it concerns something that is so at odds with your worldview that it couldn't be admitted. That was the point of the Richard Lewontin quote I provided. -

Donald HoffmanAnd yet in practice, there are procedures developed by neurologists to determine brain death in hospital situations. — apokrisis

While this is true, it is not really the point. Recall Hoffman is a cognitive scientist and there are many pages devoted to the question of the neural correlates of consciousness and what is involved in mapping sensory experiences against neural activity. He discusses the split-brain procedures and various neurological anomalies and the nature of optical illusions. But the nub of the issue is this:

______We have no scientific theories that explain how brain activity—or computer activity, or any other kind of physical activity—could cause, or be, or somehow give rise to, conscious experience. We don’t have even one idea that’s remotely plausible. If we consider not just brain activity, but also the complex interactions among brains, bodies, and the environment, we still strike out. We’re stuck. Our utter failure leads some to call this the “hard problem” of consciousness, or simply a “mystery.” We know far more neuroscience than Huxley did in 1869*. Yet each scientific theory that tries to conjure consciousness from the complexity of interactions among brain, body, and environment always invokes a miracle—at precisely that critical point where experience blossoms from complexity. The theories are Rube Goldberg devices that lack a critical domino and need a sneak push to complete the trick.

What do we want in a scientific theory of consciousness? Consider the case of tasting basil versus hearing a siren. For a theory that proposes that brain activity causes conscious experiences, we want mathematical laws or principles that state precisely which brain activities cause the conscious experience of tasting basil, precisely why this activity[…]

If we propose that brain activity is identical to, or gives rise to, conscious experiences, then we want the same kind of precise laws or principles—that link each specific conscious experience, such as the taste of basil, with the specific brain activities that it is identical to, or with the specific brain activi“ies that give rise to it. No such laws or principles have been offered [footnote reference to Integrated Information Theory].

If we propose that conscious experience is identical, say, to certain processes of the brain that monitor other processes, then we need to write down laws or principles that precisely specify these processes and the conscious experiences with which they are identical. If we propose that conscious experience is an illusion arising from some brain processes attending to, monitoring, and describing other brain processes, then we must state laws or principles that precisely specify these processes and the illusions they generate. And if we propose that conscious experiences emerge from brain processes, then we must give the laws or principles that describe precisely when, and how, each specific experience emerges. Until then, these ideas aren’t even wrong. Hand waves about identity, emergence, or attentional processes that describe other brain processes are no substitute for precise laws or principles that make quantitative predictions.

We have scientific laws that predict black holes, the dynamics of quarks, and the evolution of the universe. Yet we have no clue how to formulate laws, principles, or mechanisms that predict our quotidian experiences of tasting herbs and hearing street noise. — Donald Hoffman, The Case Against Reality

*The English biologist Thomas Huxley was flummoxed by this mystery in 1869: “How it is that anything so remarkable as a state of consciousness comes about as a result of irritating nervous tissue, is just as unaccountable as the appearance of the Djinn, when Aladdin rubbed his lamp. -

Donald HoffmanI think what makes brains conscious is that they are general informational processors whose interface to the world is the result of the modelling of sensory information you are talking. To brains, as far as they/we are concerned, such models are the subjective plentitudes we experience, they/we are wired to interface with the world in this way. — hypericin

It's a mistake to say that brains do anything - that is what is described in Philosophical Foundations of Neuroscience as the 'mereological fallacy', attributing to the part what only a whole is capable of.

we are simply limited to describing what living things do (or what things we deem as being alive do) and nothing more. — Apustimelogist

That is true, if the scope of knowledge is defined in purely objective terms. But then, you tend to naturally look at philosophical questions through a scientific perspective, don't you? Isn't that why you find Aristotle 'diametrically opposed' to your way of thinking when I've mentioned him? (That link above returns a 404 by the way, due to the inclusion of the ending colon in the URL.) -

Evidence of Consciousness Surviving the BodyI would love for there to be life after death. Only weird people who cut themselves in the dark while crying to death metal don't. — Philosophim

It is obviously true that ‘the next life’ is a fertile ground for wish-fulfilment and fantasies of living forever, but in cultures which believe in the reality of the afterlife, not all Near Death Experiences are roses and sunshine. Buddhist sacred art depicts an elaborate hierarchy of hell-realms in which beings remain enmeshed for ‘aeons of kalpas’ as a consequence of their actions in this life. There’s a publisher, Sam Bercholz, founder of Shambhala Books, which is a large American publisher of Buddhist literature. He suffered an NDE after undergoing heart surgery which he recounts in an illustrated book, A Guided Tour of Hell:

This true account of Sam Bercholz’s near-death experience has more in common with Dante’s Inferno than it does with any of the popular feel-good stories of what happens when we die. In the aftermath of heart surgery, Sam, a longtime Buddhist practitioner and teacher, is surprised to find himself in the lowest realms of karmic rebirth, where he is sent to gain insight into human suffering. Under the guidance of a luminous being, Sam’s encounters with a series of hell-beings trapped in repetitious rounds of misery and delusion reveal to him how an individual’s own habits of fiery hatred and icy disdain, of grasping desire and nihilistic ennui, are the source of horrific agonies that pound consciousness for seemingly endless cycles of time. Comforted by the compassion of a winged goddess and sustained by the kindness of his Buddhist teachers, Sam eventually emerges from his ordeal with renewed faith that even the worst hell contains the seed of wakefulness. His story is offered, along with the modernist illustrations of a master of Tibetan sacred arts, in order to share what can be learned about awakening from our own self-created hells and helping others to find relief and liberation from theirs.

So, it’s not all just ‘wake up and smell the roses’. Worse things can happen. -

Evidence of Consciousness Surviving the BodyI can find at least one person in a professional setting who will go to bat for anything. The only thing that matters is the soundness of their evidence and the logic of their argument. — Philosophim

I raised Pim Van Lommel's book because it is a source of evidence and argument. It's not something I have first-hand experience of, but if you claim that all NDE's are 'merely hallucination' then the evidence of a cardiovascular doctor who has amassed considerable data to the contrary is salient, because you're writing as if there is no such evidence.

The philosophical point is, what is the significance of such claims? If you believe they're hallucinatory, then they're not significant. But, your objections illustrate my point, as they're based on the conviction that it's all superstition and pseudo-science. I'm not going to try and persuade you otherwise, but I have an open mind about the question. -

Donald Trump (All General Trump Conversations Here)Trump is not going to deal with being challenged in the polls. I think there’s a chance he’ll go to pieces.

-

Donald Trump (All General Trump Conversations Here)

-

A (simple) definition for philosophyKant's Critique of Pure Reason is a long-winding text that rarely commits to anything actionable, but when it very occasionally does, it turns out to be wrong. — Tarskian

That text figures in many a list of great philosophical books and is also particularly relevant in our day. While I perfectly agree that Kant’s writing is voluminous and extremely difficult, I don’t believe he can be dismissed so easily. Furthermore I’m sure many who dismiss him fail to grasp the significance of that work.

Successfully arguing a point by using partial functions, is hard — Tarskian

:chin: You seem to me to be highly trained in a specific subject area but much of what you say is impenetrable to others not so trained. -

A (simple) definition for philosophyIt is naive to believe that by merely studying the old masters, you will be able to make a relevant contribution to the world of philosophy as it exists today. Instead, you will find yourself mostly divorced from the contemporary discourse. — Tarskian

.Something I will call out, is the inherent tendency of moderns to ‘historical presentism’ - that what we know now, what with science being so powerful, renders much or even all of pre-modern philosophy archaic and superseded. There is an element of truth insofar as factual matters are concerned, but in respect of questions of meaning and the nature of lived existence, the border isn’t at all clear-cut. — Wayfarer

And by the philosophical canon I don’t just mean ancient philosophy, there are many interesting current philosophers.

Accountancy companies and engineering firms might have philosophies concerning how they do business but that doesn’t necessarily mean they have wider application outside their spheres. -

A (simple) definition for philosophyI totally get that. I now have far too many books, and always the nagging realisation of how little I know. Still, I do try and relate what I’m thinking or arguing with some touch-points in philosophy generally. Something I will call out, is the inherent tendency of moderns to ‘historical presentism’ - that what we know now, what with science being so powerful, renders much or even all of pre-modern philosophy archaic and superseded. There is an element of truth insofar as factual matters are concerned, but in respect of questions of meaning and the nature of lived existence, the border isn’t at all clear-cut.

-

Donald Hoffman:lol:

I've skimmed more of the book, and am reading the concluding chapter. But at this point, I must say I don't really understand it, nor do I like it much. What he's saying seems to be compatible with the idealist type of philosophy that I favour. But I'm really not clear on a lot of it, like what conscious agents are (I no more understand that than Whitehead's 'actual occasions of experience'. ) -

Evidence of Consciousness Surviving the BodyNot long ago, nobody knew what ‘an electromagnetic field’ is. Now, fields are more fundamental than atoms, which are said to be only 'excitations of fields'. So, what is ‘physical’ is being constantly re-defined. Hence the proliferation of sci-fi movies about alternative realities and many worlds. Physics sure ain't what it used to be.

And I've long argued that if an individual life is understood as part of a continuum extending before physical birth that has consequences beyond physical death, that this can provide a framework within which the life beyond is at least conceivable. Consider that if Sheldrake's 'morphic resonance' is real (and I know that this is a contested claim) - something of the kind at least provides a medium for the persistence of habit-patterns beyond the confines of birth and death.

The Buddhist view of re-birth is instructive in this context. It is not that there is an individual entity that transmigrates from life to life (a view that is harshly condemned in the early Buddhist texts). Rather there are patterns of causation that give rise to individual lives, and these patterns can be propogated from life to life, concieved as a mind-stream (cittasantana) of which individual lives are instantiations. It is much more like a process view than an entity view. The aim of the Buddhist path is to dissociate from these repetitive patterns of experience (saṃsāra, literally 'going around') which constitutes liberation. Otherwise the same patterns will go on to generate further lives (many of which will be, shall we say, considerably less fortunate than this one, according to Buddhist lore.)

I think the work of Ian Stevenson and his followers around reincarnation are closer than the NDE research, though I have to say I haven't look at the latter research for about ten years. — Bylaw

There's also a book by a Buddhist scholastic monastic, Bhikhu Analayo, called Rebirth in Buddhism which contains a disspassionate account of the matter. I mention Stevenson from time to time, but his ideas are hugely controversial and to all intents taboo, especially on this forum. As rebirth is an accepted element in Buddhist cultures, such material doesn't suffer the same social approbation as it does in the West. (Stevenson used to say, 'when I talk about rebirth in the West, people say "that's nonsense, it never happens". When I talk about it in the East, people say "why bother with it? It happens all the time".)

Again, no one, and I mean no one, is saying that NDE's aren't real. This is the part you seem to keep glossing over. If a bunch of people have a hallucination, no one doubts they have a hallucination. — Philosophim

I don't know if Pim Van Lommel has been mentioned in this thread but he claims to have research that indicates that nde's can't be dismissed as mere hallucination. I'm not going into bat for that research, only noting that it does exist, and that he is a cardiovascular doctor who has a considerable body of research to draw on. Information about his book can be found here.

//

I think an interesting philosophical question to consider about this matter is, why the controversy? Not only is it controversial, but it provokes a great deal of hostility about 'pseudo-science' and 'superstitious nonsense'. As I said above, it's a taboo. I believe it's because it challenges the physicalist account of life, that living beings are purely or only physical in nature. If we believe that, then it's a closed question - and it's not necessarily a question we want to contemplate opening again.

We take the side of science in spite of the patent absurdity of some of its constructs, in spite of its failure to fulfill many of its extravagant promises of health and life, in spite of the tolerance of the scientific community for unsubstantiated just-so stories, because we have a prior commitment, a commitment to materialism. It is not that the methods and institutions of science somehow compel us to accept a material explanation of the phenomenal world, but, on the contrary, that we are forced by our a priori adherence to material causes to create an apparatus of investigation and a set of concepts that produce material explanations, no matter how counter-intuitive, no matter how mystifying to the uninitiated. Moreover, that materialism is absolute, for we cannot allow a Divine Foot in the door. — Richard Lewontin, review of Carl Sagan, Candle in the Dark, January 1997

Wayfarer

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum