Comments

-

How Different Are Theism and Atheism as a Starting Point for Philosophy and Ethics?But dispensing with the idea of god (the ultimate consciousness) because of the failings of a few fallible humans is throwing out one big baby with some very dirty bathwater. — Pantagruel

I’d agree with that. But don’t forget, for a great deal of the cultural history of the West, belief was dictated by the ecclesiastical authorities. The meaning of orthodoxy is ‘right belief’, and for long periods of time, the penalties for not adhering to orthodoxy were severe. And the Religious Wars in Europe were very much fought over what constitutes right belief. I think this is what caused the throwing out of the baby with the bathwater, but in some sense, it was the Churches who had sullied it with the violence through which they prosecuted ‘wrong belief’. (I think it was Paul Tillich who said that this aspect of theism was the single greatest cause of atheism.)

But then the question becomes, if right belief is *not* described by orthodoxy, what might it comprise? A lot of people, including many here, will nominate science. But the problem with that, is that science excludes the qualitative as a matter of principle. It is concerned solely with what is measurable. It is a means of control as much as anything.

So, this is the question which has elicited the thirst for alternative religion outside the strictures of religious orthodoxy. And it brings to mind one of the books I have most liked from the past, The Heretical Imperative, by sociologist Peter Berger. Berger argues that contemporary society, characterized by pluralism and secularization, compels individuals to make personal choices about their beliefs. This contrasts with traditional societies, where religious belief was generally an unchallenged given (another means of control!)

Berger explores the idea that in a modern, pluralistic society, individuals face the “heretical imperative,” a term he uses to describe the necessity to choose one’s faith actively, rather than passively inheriting it. (Note that ‘heresy’ originally meant ‘having a view’. You weren’t supposed to ‘have a view’ - you were to receive the religion as given, no questions asked.) This situation leads to a range of responses, including reaffirmation of traditional beliefs, embracing of secular worldviews, or the adoption of a methodological doubt approach, where individuals continuously question and reassess their beliefs.

Berger also delves into the implications of this imperative for religious institutions, highlighting the challenges they face in maintaining relevance and authority in a world where belief is a choice. He proposes that these institutions need to adapt by becoming more open and accommodating to the diverse spiritual needs of individuals. In the book, he presents the metaphorical choice “between Jerusalem and Benares” to illustrate the fundamental decision modern individuals face in responding to the Heretical Imperative. This choice represents two distinct religious paradigms.

“Jerusalem” symbolizes the Abrahamic faiths—Judaism, Christianity, and Islam—which are monotheistic and have a historical, prophetic tradition. These faiths emphasize a personal God, ethical demands, and a linear view of history leading to an ultimate purpose or end. They tend towards dogmatism and exclusivism, that there can only be one true religion.

“Benares” (nowadays Varanasi), on the other hand, represents the Eastern religions, such as Hinduism and Buddhism. These traditions are more mystical, focusing on inner spiritual experiences, encompassing principles of re-birth and karma with a cyclical as distinct from liner view of time and existence. This metaphor underscores the diversity and complexity of religious choices in a pluralistic society.

Viewing the ‘theism/atheism’ divide against that background reveals that it is considerably more nuanced than the apparent black-and-white, yes-or-no issue that single-minded adherents of both sides of the debate would care to contemplate. After all, some of the Eastern religious paths are hardly theist in a Semitic sense, but they’re certainly not atheistic in the secular sense, either. -

The Blind Spot of Science and the Neglect of Lived ExperienceOh - and the word I had in mind was 'being', athough both the essay and the book draw heavily on phenomenology.

-

The Blind Spot of Science and the Neglect of Lived ExperienceI rescuscitated the thread because the book that was based on the original Aeon essay is being published in April.

-

The Blind Spot of Science and the Neglect of Lived ExperienceYes, I can see you two wouldn't get along. Talis is a reactionary from the post-modernist pov, but then that probably applies to me also :yikes:

I will say, when I did my two-odd years of undergraduate philosophy, late 70s-early 80s, my exposure was pretty mainstream - Descartes, Hume, Rosseau, logical positivism, philosophy of science, are the ones I recall. I'm sure that there were classes on the post-moderns but at that time, in that university, I didn't come across them. Most of what I've subsequently learned about them, which is not much, I've gleaned from references here, although I saw a really interesting video, The Imaginary, the Symbolic and the Real: the Register Theory of Lacan. That really resonated with me, but it's about all I know of Lacan. -

Paradigm shifts in philosophy'Being modern' or 'the modern worldview' is itself an over-arching paradigm, because it embodies many unspoken axioms or presumptions about 'the nature of things' or 'the way things are' that are themselves philosophical in nature. And it is, of course, constantly changing (hence, post-modernism, post-secular and other such descriptors.) But then the task of a critical philosophy is bringing these presuppositions to conscious awareness - which is difficult, as they are like the spectacles through which we view everything and it's hard to look at them, instead of through them.

-

The Blind Spot of Science and the Neglect of Lived ExperienceI believe I have mentioned this before, but if you can find yourself a copy of Tallis' The Knowing Animal, I think you will very much enjoy it.

I think it is his best work, by far, and I have read quite a bit of him. — Manuel

I wrote to Tallis after getting one of his books, and he replied very positively. I will look out for that title! (Looking at the Amazon page, one of the reviews comes from James le Fanu, another UK writer from a medical background, who's book Why Us? also really impressed me, about 10 years ago, which is of a similar genre. )

:up: -

The Blind Spot of Science and the Neglect of Lived ExperienceI think it's because pre-moderns had a fundamentally different 'experience of the world' as or them, it was an expression of the divine intelligence. So they had an 'I-thou' experience (per Martin Buber) rather than the experience of separatness which is the hallmark of modernity.

-

How Different Are Theism and Atheism as a Starting Point for Philosophy and Ethics?For example, do you think the typical US Evangelical Trump fan, or Iranian Ayatollah fan, is likely to be an Eagleton and Hart fan as well? — wonderer1

No, of course not. It's all become massively distorted, a quagmire of confusion and ignorance. But then the mystics, those with the most penetrating insight, are often condemned or put to death by religious authorities. -

Donald Trump (All General Trump Conversations Here)It's going to take a lot of mug-shot t-shirt sales to cover that one.

-

The Blind Spot of Science and the Neglect of Lived ExperienceHe takes it further and says that there is no objective or universal truth that stands independently of human interpretation. While you would accept the possibility of something approaching a Platonic realm. Nietzsche also subdivides perspective into both cultural and individual blindspots. His somewhat brutal visual approach to this struck me as apropos. — Tom Storm

I generally avoid comment on Nietzsche as I’ve never felt compelled to read him and don’t know his writings very well. But I don’t agree with his perspectivism, that literally everything is a matter of perspective. I accept the Buddha’s teaching that there is an unborn, unmade, unconditioned. But that this can’t be made subject of propositional logic, as it is subtle, deep, and profound, discernible only by the wise, and has to be discerned by each one for themselves (to paraphrase the canonical text.)

The problem with objectivity as usually construed is that it is anchored to sense-perception - that only what can be validated by senses and instruments can be taken into consideration. And as I said before, it’s a matter of fact that all sense-objects are conditioned. This results in a sense of misplaced absoluteness. The stakes in philosophy are much higher than that.

As for ‘we behold these things through a human head’ - ‘going beyond’ I take to be the point of enlightenment or sagacity. One of the books on my Amazon Wishlist which I’ll probably never get around to is To Think Like God, an account of Parmenides and Pythagoras, the title makes the point. But in our culture, such enlightenment is generally lumped in alongside religion by those who understand neither, and then dismissed on those grounds as ‘mere belief’. Can of worms, I know. -

The Blind Spot of Science and the Neglect of Lived ExperienceHere's a snippet from the essay which drives the point home.

— Wayfarer

I think much of this is correct, but what I find is that usually, at one point or another, these interlocutors have a tendency to overstate their case. It's pretty easy to fall into an excessive subjectivism when you are pressing hard against modern "objectivism." It's like when you are driving a motorcycle in high winds, leaning hard just to stay straight, and then the wind drops away and the bike swerves. — Leontiskos

On further thought, don’t agree. I looked back to when I first posted this five years ago, the response was vitriolic, it was taken as an attack on science. But it is not an attack on science. They say at the beginning:

This (their criticism) doesn’t mean that scientific knowledge is arbitrary, or a mere projection of our own minds. On the contrary, some models and methods of investigation work much better than others, and we can test this. But these tests never give us nature as it is in itself, outside our ways of seeing and acting on things. Experience is just as fundamental to scientific knowledge as the physical reality it reveals. …..

The Blind Spot arises when we start to believe that this method gives us access to unvarnished reality. But experience is present at every step. Scientific models must be pulled out from observations, often mediated by our complex scientific equipment. They are idealisations, not actual things in the world. Galileo’s model of a frictionless plane, for example; the Bohr model of the atom with a small, dense nucleus with electrons circling around it in quantised orbits like planets around a sun; evolutionary models of isolated populations – all of these exist in the scientist’s mind, not in nature. They are abstract mental representations, not mind-independent entities. Their power comes from the fact that they’re useful for helping to make testable predictions. But these, too, never take us outside experience, for they require specific kinds of perceptions performed by highly trained observers.

What I would take issue with is the use of the word ‘experience’ in these passages What I think is being referred to is closer in meaning to the capacity for experience - in other words, being. When they say ‘experience is just as fundamental’ - you can respond, ‘well, sure, isn’t that what ‘empiricism’ means?’ Empiricism, after all, means ‘verifiable in experience’. But that’s not what they’re trying to highlight. They’re pointing to the experiential aspect of even so-called objective measurement. When they say ‘experience is present at every step’, I think what they’re saying is simply ‘science is an activity of beings. The facts it discloses are registered and understood by beings - by human beings.’ But we don’t notice that, because of the ostensibly objective and observer-independent nature of scientific observation. We think that these facts are entirely observer-independent, which in one sense is true, but in a deeper, philosophical sense is not.

That’s what I see as the point of this essay, and the book that comes from it, and I think it needs saying. I talk to people here almost every day who don’t see this point (I don’t mean you.)

(I think there’s a connection here with Heidegger’s ‘forgetfulness of Being’, although he traces that back to metaphysics rather than to science per se. Although it’s also the case that scientific method was also an outgrowth of metaphysics e.g. E A Burtt’s ‘Metaphysics of Modern Science’.) -

Absential MaterialismActually I will provide more of a reason for the section in Deacon's book that turned me off it. it's the discussion about the homuncular fallacy, and in particular passages like this:

Why should ententional explanations tend to get eliminated with the advance of technological sophistication? The simple answer is that they are necessarily incomplete accounts. They are more like promissory notes standing in for currently inaccessible explanations, or suggestive shortcuts for cases that at present elude complete analysis. It has sometimes been remarked that teleological explanations are more like accusations or assignments of responsibility rather than accounts of causal processes. Teleological explanations point to a locus or origin but leave the mechanism of causal efficacy incompletely described. Even with respect to persons, explaining their actions in terms of motives or purposes is effectively independent of explaining these same events in terms of neurological or physiological processes and irrespective of any physical objects or forces.

...Like an inscrutable person, an ententional process presents us with a point at which causal inquiry is forced to stop and completely change its terms of analysis. At this point, the inquiry is forced to abandon the mechanistic logic of masses in motion and can proceed only in terms of functions and adaptations, purposes and intentions, motives and meanings, desires and beliefs. The problem with these sorts of explanatory principles is not just that they are “incomplete, but that they are incomplete in a particularly troubling way. It is difficult to ascribe energy, materiality, or even physical extension to them.

In this age of hard-nosed materialism, there seems to be little official doubt that life is “just chemistry” and mind is “just computation.” But the origins of life and the explanation of conscious experience remain troublingly difficult problems, despite the availability of what should be more than adequate biochemical and neuroscientific tools to expose the details. So, although scientific theories of physical causality are expected to rigorously avoid all hints of homuncular explanations, the assumption that our current theories have fully succeeded at this task is premature.

But I take it from what follows, is that he hopes and believes that physical theories will succeed, once they incorporate and understand his particular conceptual vocabulary with its absentials, teleodynamics, autogens, and so.

But what occurs to me, is the sense in which science seeks to subordinate the issues that it investigates to its methods and vocabulary. To explain something, in scientific terms, is to provide a full account of why it is the way it is. But when the subject is the nature life and mind, then we're really considering questions about the meaning of being, as such. And can such questions really be subordinated to scientific explanation? Isn't that more than a little hubristic?

(By way of contrast, for example, Buddhist philosophy seeks to provide an account of why life is the way it is, through its structure of the four truths, the eightfold path, and liberation from Saṃsāra. But it is not seeking a scientific explanation, that is, one that is third-person in the sense that scientific explanation is.)

Yes, Deacon sees through the (to me) obvious flaws and shortcomings of mechanistic materialism, but he's still first and foremost scientific in orientation, seeking, I think, instrumental explanations rather than philosophical insight for its own sake. I can see he's obviously a very clever academic and his work has its merits, but I don't think I'm going to invest the time required to fully absorb the book. -

How Different Are Theism and Atheism as a Starting Point for Philosophy and Ethics?So, I am asking to what extent does the existence of 'God', or lack of existence have upon philosophical thinking. Inevitably, my question may involve what does the idea of 'God' signify in itself? The whole area of theism and atheism may hinge on the notion of what the idea of God may signify. Ideas for and against God, which involve philosophy and theology, are a starting point for thinking about the nature of 'reality' and as a basis for moral thinking. — Jack Cummins

The first article that drew me to philosophy forums was a scathing review, by Terry Eagleton, of Richard Dawkin's book The God Delusion, way back in about 2008 or so. Some background. Terry Eagleton, whom I hadn't heard of prior, is an English leftist literary critic and academic. I've subsequently read a few of his other books, which are often very erudite and betoken a huge range of reading.

Anyway his critique of Dawkins was called Lunging, Flailing, Mispunching, and speaking of punches, he didn't pull any.

Dawkins speaks scoffingly of a personal God, as though it were entirely obvious exactly what this might mean. He seems to imagine God, if not exactly with a white beard, then at least as some kind of chap, however supersized. He asks how this chap can speak to billions of people simultaneously, which is rather like wondering why, if Tony Blair is an octopus, he has only two arms. For Judeo-Christianity, God is not a person in the sense that Al Gore arguably is. Nor is he a principle, an entity, or ‘existent’: in one sense of that word it would be perfectly coherent for religious types to claim that God does not in fact exist. He is, rather, the condition of possibility of any entity whatsoever, including ourselves. He is the answer to why there is something rather than nothing. God and the universe do not add up to two, any more than my envy and my left foot constitute a pair of objects. — Terry Eagleton

(Notice the out-dated references, places it quite well. I subsequently joined the Richard Dawkins forum, long since inactive, which was exactly as you would expect, manned and moderated by the most vociferous of Dawkinsian atheists, against which hapless evangelicals would dash their arguments to pieces against their massed polemical barbs. It was after that, that I found another forum, and then the precessor forum to this one. It's remained an interest.)

Anyway, I was interested, in particular, in Eagleton saying that 'it would be perfectly coherent for religious types to claim that God does not in fact exist.' 'Ah', you might say. 'But isn't that just atheism?'

Well, no. And the reasoning is given by a Bishop (of all people) in a newspaper opinion piece called (tantalisingly) God does Not Exist:

If God does exist, then that is not God. All existing things are relative to one another in various degrees. It is actually impossible to imagine a universe in which there is, say, only one hydrogen atom. That unique thing has to have someone else imagining it. Existence requires existing among other existents, a fundamental dependency of relation. If God also exists, then God would be just another fact of the universe, relative to other existents and included in that fundamental dependency of relation. — Bishop Pierre Whalon

Read the article for further elaboration. But that theme is something central to what is inelegantly described as apophatic theology, the theology of negation: you can't say anything about what God is, because God is beyond all description. ('You don't say!')

Finally, one of the better books on the topic, notwithstanding its frequent polemical passages, is David Bentley Hart's The Experience of God. He 'gets' this understanding of the meaning of 'beyond existence' in ways that most do not.

Now there are sophisticated atheists that do understand what it is they are seeking to deny. But a lot atheism speaks of God as a poor empirical hypothesis ('Where's the evidence?') or seems to envisage him as a kind of cosmic film director or CEO ('why are so many people suffering around here?? Who's in charge? :rage: )

That's some background and references. It's also worth mentioning that Paul Tillich, in particular, was a modern theologian who put great emphasis on negative theology and the God beyond existence.

An atheist that rages against God objectively all the time obviously gives "God" a lot of attention. — Vaskane

'Atheists are those who still feel the weight of their chains' ~ Albert Einstein (bona fide). -

Absential MaterialismInteresting JSTOR review of Deacon from a process-theology oriented academic:

Is Terrence Deacon's Metaphysics of Incompleteness Still Incomplete? (free but requires registration.)

I'm going to call it a day with Deacon, I have other fish to fry. -

US Election 2024 (All general discussion)Ironically, right now Trump seems to be holding up an immigration bill in the Senate that would help address the border that the GOP seems to approve of. — Mr Bee

It's not 'ironic', it's a deliberate tactic. He's furious that if the bill goes any way to addressing the problem, then it will reflect positively on Joe Biden. He wants the problem to be as bad as possible, so he can use it against Biden and then take credit for solving it himself.

I don't expect people to blame him. — Mr Bee

The Senate Republicans and the moderate Republicans in Congress are all furious about it. -

Absential MaterialismHow do you think the Pythagorean Theorem was discovered/ confirmed if not by observation and measurement? — Janus

So, there is no category of apriori facts? The only facts are those 'confirmable by observation'? How does that apply to mathematical theorems, and other 'truths of reason'? Even in the case of triangles, simple observation would not suffice to establish the facts. -

The Blind Spot of Science and the Neglect of Lived ExperienceThe 'blind spot ' of science may come down to the means and reliability of scientific measurement. So much may come into play of the role of participant observer bias and meanings. The blind spot itself may be a gulf of void of unknowing, and it may in itself be an area for expansion of idea of possibilities in the development of ideas. The blimspots of vision and philosophical visio may be dismissed or attuned to, in the scope of understanding of perception.and its significance. — Jack Cummins

The essay I linked to spells it out pretty clearly. It doesn't come down to the 'reliability of scientific measurement'. Measurement is one of the things that modern science excels at, science can measure things from the sub-atomic to the cosmic with astonishing precision. It is more about the idea that science, or us human beings using science, see the world as it truly is, as it would be without any observers in it.

Behind the Blind Spot sits the belief that physical reality has absolute primacy in human knowledge, a view that can be called scientific materialism. In philosophical terms, it combines scientific objectivism (science tells us about the real, mind-independent world) and physicalism (science tells us that physical reality is all there is). Elementary particles, moments in time, genes, the brain – all these things are assumed to be fundamentally real. By contrast, experience, awareness and consciousness are taken to be secondary. The scientific task becomes about figuring out how to reduce them to something physical, such as the behaviour of neural networks, the architecture of computational systems, or some measure of information. -

The Blind Spot of Science and the Neglect of Lived ExperienceIf it is given that a thing is intelligible, in what sense are there conditions for the possibility of its being intelligible? For that which is given, re: those things that are intelligible, the very possibility of it is also given, so wouldn’t the conditions be met? — Mww

More fully explained in the original essay. -

Absential MaterialismHow do you think the Pythagorean Theorem was discovered/ confirmed if not by observation and measurement? — Janus

Deductive truths are inferred from rational principles. That It is true of any triangle doesn’t need to validated by observing every particular .

But with deference to Deacon, he is certainly no lumpen materialist. He holds up Francis Crick’s neural materialism as an example of same. I am suspicious of the claim of the necessity of a ‘neural substrate’, that an idea is only real if it is instantiated in a physical brain, but I’m still considering Deacon’s book. -

Absential MaterialismDo abstract concepts exist independent of minds contemplating them? — ucarr

I would turn the question around, and ask if 'the law of the excluded middle' or 'the Pythagorean theorem' came into existence when humans first grasped them. It seems to me the answer is 'obviously not', that they would be discovered by rational sentient beings in other worlds, were they to have evolved. Yet they are the kinds of primitive concepts which constitute the basic furniture of reason.

Albert Einstein saidI cannot prove scientifically that Truth must be conceived as a Truth that is valid independent of humanity; but I believe it firmly. I believe, for instance, that the Pythagorean theorem in geometry states something that is approximately true, independent of the existence of man.

I think that is true, but that it's also true that while the theorem might exist independently of man, it can only be understood by humans. So it's mind-independent, on one hand, but only perceptible to a mind, on the other.

The next question I would ask, in what sense do such principles exist? Is the Pythagorean Theorem 'out there somewhere' - a popular expression for whatever is thought to be real. To which I'd respond in the negative - such principles are not situated in space and time, neither are arithmetical primitives or the other fundamental constituents of rational thought. But due to the influence of empiricism on philosophy, the nature of such principles must be relegated to the subjective or attributed to what you describe as 'brain phenomena'. But notice that 'phenomena' means 'what appears' but that whatever we ascribe to the neural domain can only be a matter of inference; nothing actually appears in a brain as object of neuroscientific analysis, save patterns of bio-electrical activity. But it seems to me that in support of your materialist thesis, you must insist on the connection between abstract principles and neural configuration, to maintain the connection with a material substrate, as an 'output' or 'result' of 'neural activities'.

I'll leave it at that for now, I'm up to Deacon's discussion of homuncular arguments, where I think I am beginning to detect a hint of scientism poking through the verbiage.

Although I will add that it is precisely at that point in cultural development where reason discerns unchangeable principles underpinning the flux of experience, that metaphysics proper emerged. -

The Blind Spot of Science and the Neglect of Lived ExperienceI think it suggests that Thompson thinks that the matters he brings up shouldn't be taken as supporting idealism. — wonderer1

I quoted what he said about idealism verbatim. If you missed it go back and have another look. Note the distinction he makes between subjective idealism and Kant - 'Kant's sense of "transcendental"' - and Kant's is still an idealism. -

The Blind Spot of Science and the Neglect of Lived ExperienceBut crucially, his statement is conditional, "...once you remove the life world." He is not talking about unperceived objects, he is talking about objects stripped of their condition of intelligibility (which he calls the life world). — Leontiskos

Which is the same as what I'm saying:

I am making clear the sense in which perspective is essential for any judgement about what exists — even if what we’re discussing is understood to exist in the absence of an observer, be that an alpine meadow, or the Universe prior to the evolution of h. sapiens. The mind brings an order to any such imaginary scene, even while you attempt to describe it or picture it as it appears to exist independently of the observer. — Wayfarer

That's what he, and Husserl, mean by the 'lebenswelt' - the 'life-world' of assumed meanings and relationships, which is assumed even in contemplating 'the universe prior to all subjectivity'.

Here's a snippet from the essay which drives the point home.

In general terms, here’s how the scientific method works. First, we set aside aspects of human experience on which we can’t always agree, such as how things look or taste or feel. Second, using mathematics and logic, we construct abstract, formal models that we treat as stable objects of public consensus. Third, we intervene in the course of events by isolating and controlling things that we can perceive and manipulate. Fourth, we use these abstract models and concrete interventions to calculate future events. Fifth, we check these predicted events against our perceptions. An essential ingredient of this whole process is technology: machines – our equipment – that standardise these procedures, amplify our powers of perception, and allow us to control phenomena to our own ends.

The Blind Spot arises when we start to believe that this method gives us access to unvarnished reality. But experience is present at every step. Scientific models must be pulled out from observations, often mediated by our complex scientific equipment. They are idealisations, not actual things in the world. Galileo’s model of a frictionless plane, for example; the Bohr model of the atom with a small, dense nucleus with electrons circling around it in quantised orbits like planets around a sun; evolutionary models of isolated populations – all of these exist in the scientist’s mind, not in nature. They are abstract mental representations, not mind-independent entities. Their power comes from the fact that they’re useful for helping to make testable predictions. But these, too, never take us outside experience, for they require specific kinds of perceptions performed by highly trained observers.

For these reasons, scientific ‘objectivity’ can’t stand outside experience; in this context, ‘objective’ simply means something that’s true to the observations agreed upon by a community of investigators using certain tools. Science is essentially a highly refined form of human experience, based on our capacities to observe, act and communicate. — The Blind Spot

The realisation I've had, is that all objects of perception are conditioned. (Yes, very Buddhist.) But due to the influence of empirical philosophy, somehow the mind-independence of supposed objects of perception are supposed to be the very yardstick by which we ascertain what is real. -

The Blind Spot of Science and the Neglect of Lived ExperienceIn your quote of Thompson, after clarifying that his claim is not about existence, he spends nine sentences explicating his position, and he does not reference existence or non-existence once in those nine sentences — Leontiskos

So in philosophical jargon, this is a transcendental claim, in Kant's sense of transcendental. It's about the conditions of possibility of the intelligibility of things, such as the past, or time, given that they are, indeed, intelligible. So there's no problem with ancestrality statements understood as statements about facts in the past, before there was subjectivity. Rather, the point is that such statements have no sense or intelligibility once you remove the life world. In that case, the statements suffer from a kind of presupposition failure, and they have no significance. They're neither true nor false. They don't refer at all. — Evan Thompson

Compare that with what I said here:

The idea that things ‘go out of existence’ when not perceived, is simply their ‘imagined non-existence’. In reality, the supposed ‘unperceived object’ neither exists nor does not exist. Nothing whatever can be said about it. — Wayfarer

I'm saying Thompson's 'they don't refer at all' is exactly synonymous with 'nothing whatever can be said about it'. I'm expressing the same idea as he is, in a slightly different way. The whole thrust of the Mind Created World is that it is impossible to speak of a truly mind-independent reality, as whatever is totally detached from the 'meaning world' that constitutes our consciousness is literally unintelligible. Note that I also explicitly reject subjective idealism and the idea that 'mind' is a literal constituent of objective reality (panpsychism). So I see the approach of the Mind Created World as very much aligned with that expressed in the essay at the head of this OP, The Blind Spot of Science is the Neglect of Experience.

Your view reminds me of Madhyamaka Buddhism, but I doubt many scientists would take up a Buddhist philosophy to such a strong extent. — Leontiskos

Why thank you, very perceptive.

You may not be aware, but Evan Thompson was co-author, with Francisco Varela and Eleanor Rosch, of 'The Embodied Mind', which has become a seminal book in the formation of 'embodied philosophy' and 'enactivism'. That book draws extensively on Buddhist abhidharma (philosophical psychology). Indeed Varela was one of the prime movers behind the Life and Mind Conferences, of which the Dalai Lama is the Chair, and before his untimely death took he lay ordination in a Buddhist order. So there is a Buddhist influence in that book.

Subsequently, Evan Thompson has published 'Why I am Not a Buddhist', in which he explains his critical view of what he calls 'Buddhist Modernism' and gives his reasons for why he doesn't consider himself formally Buddhist. Nevertheless throughout Thompson's writing there are perceptible influences of both Buddhist non-dualism and phenomenology, among other sources. He says in that book and elsewhere he remains positively disposed towards Buddhism. -

Donald Trump (All General Trump Conversations Here)Trump acts as if he's convinced he's above the law, and Trump supporters likewise view him as above the law, or as BEING the law. Hence his constant denigration of his prosecutors as 'perverts' and 'communists' and the cases being 'conspiracies' and 'hoaxes'. And millions believe him. Another of the enormous disservices he's doing to American civil society.

-

Absential MaterialismFair point, but he also makes it clear that what is at 'the bottom' of the 'bottom-up process' are not atoms as such. At the end of Chapter One, he says:

The current paradigm in the natural sciences conceives of causal properties on the analogy of some ultimate stuff, or as the closed and finite set of possible interactions between all the ultimate objects or particles of the universe. As we will see, this neat division of reality into objects and their interaction relationships, though intuitively reasonable from the perspective of human actions, is quite problematic. Curiously, however, modern physics has all but abandoned this billiard ball notion of causality in favor of a view of quantum processes, associated with something like waves of probability rather than discretely localizable stuff.

Here he's expressing the idea that physics itself has undermined physicalism, insofar as this was conceived as being reliant on the existence of 'ultimate objects'. Instead, it suggests a process-oriented approach associated with "waves of probability". So again, how this can be described as materialism escapes me. He's explicitly distancing himself from that, which he identifies as the 'current paradigm'. This is why he remarks that his 'absentials' are likely to be dismissed as mysticism by a lot of hard-nosed scientists (which I'm sure they have been). Sure, he has to thread the needle of not asserting immaterial forces or objects, while at the same time showing the inherent falsehoods of mechanistic materialism and the 'machine' analogy, which he explicitly rejects. But I don't see him as favourable to any form of atomistic materialism (and if it ain't atomistic, then what is it :yikes: ? )

The other subtle point is that constraints themselves, which are central to his model, are top-down by nature. Top-down constraints impose order and coherence within a system by providing a framework or set of rules that guide the behavior of its parts. They are essential for ensuring that the system functions in a coherent and organized manner. In his model, anything that exists does so as a consequence of the adaption of bottom up processes to top-down constraints. He mentions in Chapter One the relevance of universals - 'types of things have real physical consequences' . And these can hardly be said to originate at the base level - they act as the kinds of delimitations on possibility that dictate the form of particulars. The requirement for the wing to be lightweight is a top-down constraint. It is imposed because a heavy wing would make whatever can fly less able to stay aloft. Flatness is another top-down constraint, as the shape s crucial for generating lift, which is essential for flight. If the wing were small and dense or had a different shape, it will not generate the necessary lift. And that is 'multiply realised' in birds, bats, flying mammals, and aeroplanes (hence 'the wing', or rather, 'flight', as an Idea or universal.)

As far as the hard problem of consciousness is concerned, the review I quoted from Evan Thompson points out:

an animal's sentience is not the sum of the sentience of its individual cells: the nervous system creates its own sentience at the level of the whole animal. Yet Deacon doesn't get to grips with the hard problem of explaining why and how we and other animals have conscious experience. Simply pointing to the neural activity associated with sentience is not enough to answer this question. What we need to know is why this activity feels pleasant or painful to the animal, instead of being an absence of feeling. In my view, Deacon's error is not that he has no answers to such questions (no one does), but that he fails to recognize them. — Evan Thompson

(It should be mentioned that Evan Thompson's 'Mind in Life' is of a very similar genre to Deacon's. Thompson is overall positive about Deacon's book, with the above caveat.)

That criticism is also made in the long and difficult review I posted in by R Scott Bakker, who says that throughout the book, Deacon fails to comes to terms with the role of the observer in the formulation of his theory, meaning that it is in some sense 'a massive exercise in question-begging'.

None of that is the last word of course and Deacon's book has considerable depth and subtlety, but I do think there is something in those criticisms. -

Absential MaterialismI have never denied the existence of brain for the precondition of mind.

He also seem to think I was an idealist, which was not the case. If someone is not materialist, then it doesn't automatically place him into a position of being an idealist. — Corvus

Fair point. I don't agree much with ucarr either. I'm talking more about Deacon, which I give ucarr the credit for causing me (and no, that is not a matter of material causation!) to read more of.

Mind causes matter to change, move and work. A simple evidence? I am typing this text with my hands caused by my mind. If my mind didn't cause the hands to type, then this text would have not been typed at all. — Corvus

This is very much the kind of observation that Deacon starts his book with:

The meaning of a sentence is not the squiggles used to represent letters on a piece of paper or a screen. It is not the sounds these squiggles might prompt you to utter. It is not even the buzz of neuronal events that take place in your brain as you read them. What a sentence means, and what it refers to, lack the properties that something typically needs in order to make a difference in the world. The information conveyed by this sentence has no mass, no momentum, no electric charge, no solidity, and no clear extension in the space within you, around you, or anywhere. More troublesome than this, the sentences you are reading right now could be nonsense, in which case there isn’t anything in the world that they could correspond to. But even this property of being a pretender to significance will make a physical difference in the world if it somehow influences how you might think or act.

Obviously, despite this something not-present that characterizes the contents of my thoughts and the meaning of these words, I wrote them because of the meanings that they might convey.

So he does obviously consider these kinds of arguments. I'm still at early stages - it's a 608 page book! - but I haven't yet hit the point where I think, 'this just can't be right'. -

Absential MaterialismYour questions and posts have been mostly based on the false assumptions and misunderstandings on the other party's stance. — Corvus

I’m in your corner, but so far you have nothing to go on but sentiment. You could benefit from some more reading, starting with one of the books this thread is about, "Incomplete Nature" by Terrrence Deacon. You may not agree with it, but considering Deacon’s arguments is instructive. And, as I said, I'm in your corner, I don't agree with materialism in the least.

In this interview Deacon discusses the main concepts of Incomplete Nature. I can't find too much to fault. -

US Election 2024 (All general discussion)Yeah but Trump has been saying it's going to be a hiding, 90% or more.

Anyway, she better keep going. The Republicans are soon going to require a spare ;-) -

US Election 2024 (All general discussion)Pundits are saying he'll definitely win, but not by as big a margin as expected.

-

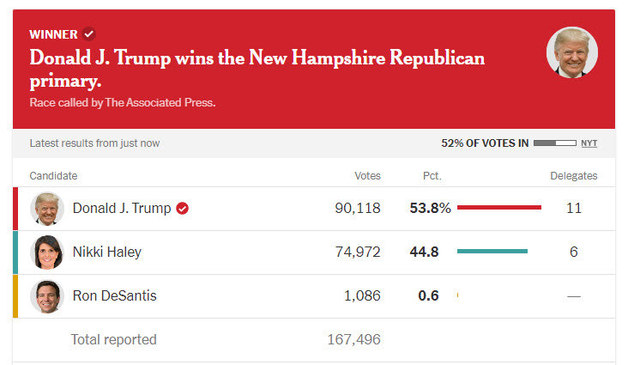

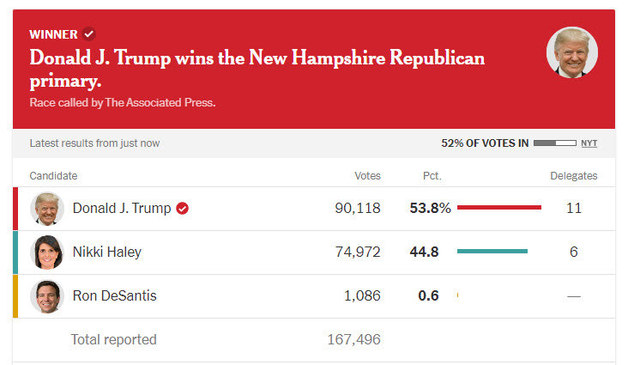

US Election 2024 (All general discussion)

Trump is ahead, as the polls predicted, but it's hardly a blowout. -

Absential MaterialismDo thoughts exist outside of the minds thinking them?

Do minds exist outside of the brains substrating them? — ucarr

A difficult and delicate question.

The bottom-up account of such entities is that they are the product of lower-level processes, beginning at the level of physical and chemical interactions, which evolve in such a way as to give h. sapiens the ability to produce such ideas. This is the mainstream consensus.

Deacon is concerned with just this issue. How intentional acts can have physical consequences, even though intentionality itself is not accomodated by physicalist accounts. That is the explanatory gap he's wanting to bridge. His account is that all living things posses a quality of goal-directedness - ententionality - which anticipates the more elaborate intentional abilities that rational sentient beings possess. Hence his lexicon of autogens and teleodynamics and so on.

But to provide an alternative 'top-down' account and framework would be too much of a digression for this discussion. I'll just note at this point that I'm more open to the platonist perspective on this question that Deacon says he is. -

The Blind Spot of Science and the Neglect of Lived ExperienceFrom around 36:23 -

One (claim) is that nothing exists outside of or apart from experience. That's not the claim I'm making. That's a first order claim about existence. It amounts to what philosophers call subjective idealism, that everything exists inside the mind, or that everything that exists is dependent on the mind. But the claim I'm making isn't about existence. It's about meaning or sense or intelligibility. The claim is that how things appear to us, how they show up for us in the life world, in our perception and action, is a necessary condition of the possibility of things being intelligible at all. So in philosophical jargon, this is a transcendental claim, in Kant's sense of transcendental. It's about the conditions of possibility of the intelligibility of things, such as the past, or time, given that they are, indeed, intelligible. So there's no problem with ancestrality statements understood as statements about facts in the past, before there was subjectivity. Rather, the point is that such statements have no sense or intelligibility once you remove the life world. In that case, the statements suffer from a kind of presupposition failure, and they have no significance. They're neither true nor false. They don't refer at all. — Evan Thompson

Aligns with the argument made in Mind-Created World.

The idea that things ‘go out of existence’ when not perceived, is simply their ‘imagined non-existence’. In reality, the supposed ‘unperceived object’ neither exists nor does not exist. Nothing whatever can be said about it. — Wayfarer -

Absential MaterialismThat's what he's working towards. As said, I quite like the book, I'm finding it pretty compelling, although I've also skipped ahead to some of his more philosophical chapters and critiques of those.

With consciousness, Deacon says that sentience — the capacity to feel — arises from a system being self-sustaining and goal-directed. So he sees individual cells as sentient. But, as he explains, an animal's sentience is not the sum of the sentience of its individual cells: the nervous system creates its own sentience at the level of the whole animal. Yet Deacon doesn't get to grips with the hard problem of explaining why and how we and other animals have conscious experience.

Simply pointing to the neural activity associated with sentience is not enough to answer this question. What we need to know is why this activity feels pleasant or painful to the animal, instead of being an absence of feeling. In my view, Deacon's error is not that he has no answers to such questions (no one does), but that he fails to recognize them. — Evan Thompson

Also, I've been well aware of what he is designating 'absentials' for a long time, but I conceptualise them in an entirely different way. As I explain in my Medium essay on the nature of number, what he refers to as absent or non-existent, I think of as being real in a different mode to phenomenal existents. Numbers, logical laws, principles, even scientific laws, are not existent as are chairs, tables, mountains, etc, but they are real as constituents of the meaning-world; perhaps they can be conceptualised as noumenal realities, as distinct from phenomenal existents. I don't feel any compulsion to try and account for them in physical terms, or reduce them to something a physicist might be comfortable with.

But I'll persist with reading Deacon for the time being, I find his prose style quite approachable. -

Absential MaterialismEmergent properties have radically different agendas from their lower-order substrates, to which they remain bound and without which that could not exist — ucarr

Only agents have agendas. This is where Deacon coins the neologism 'ententionality'. It refers to the goal-directedness that characterises organic life and is absent in chemical or physical reactions: 'both life and mind have corssed a threhold to a realm whjere more than just what is materially present matters'. -

Absential MaterialismBut the significance of what he calls abstentials is that while they have physical consequences, they're not physical in nature. He himself says that he is trying to move the scientific account in a less materialist direction. I agree he's trying to work within a naturalist framework, but he's doing that by extending the meaning of naturalism beyond materialism. Again, the term 'absential materialism' does not appear in the book.

-

Absential MaterialismThat the brain is able to invoke a meaning, a concept, from a symbol is trivial. In a deterministic universe, the symbol is the cause for the thought of the concept. — Lionino

Where the term 'cause' carries a completely different meaning to physical causation.....

That is very much connected to the thesis of the book this thread is about, Terrence Deacon's Incomplete Nature. -

Absential MaterialismA specific characteristic of mental acts, which do not have an analogy in material objects or states, is intentionality or 'aboutness'. Intentionality refers to the property of mental states or representations that they are about or directed towards something external to themselves. In other words, intentional mental states have meaning and refer to objects, concepts, or events in the world.

Materialism, as a theory of mind, posits that all mental phenomena can ultimately be explained in terms of physical processes in the brain.But this faces a challenge in explaining intentionality. Purely physical processes do not inherently possess meaning or reference, and so can't account for the intentional nature of mental acts.

the puzzle intentionality poses for materialism can be summarized this way: Brain processes, like ink marks, sound waves, the motion of water molecules, electrical current, and any other physical phenomenon you can think of, seem clearly devoid of any inherent meaning. By themselves they are simply meaningless patterns of electrochemical activity. Yet our thoughts do have inherent meaning – that’s how they are able to impart it to otherwise meaningless ink marks, sound waves, etc. In that case, though, it seems that our thoughts cannot possibly be identified with any physical processes in the brain. In short: Thoughts and the like possess inherent meaning or intentionality; brain processes, like ink marks, sound waves, and the like, are utterly devoid of any inherent meaning or intentionality; so thoughts and the like cannot possibly be identified with brain processes. — Edward Feser

Wayfarer

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum