Comments

-

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismReading through, the play for indirect realism seems to be to pick two supposedly distinct aspects of a perceiver and to have one mediate perception for the other. This gives the impression that there are 3 parties, a relationship that is necessary for mediation, and for indirect realism.

But the distinction is abstract and has no empirical grounds. All one has to do is observe a perceiver and note that only two parties are involved in the perceptual relationship, and all the indirect realist has really done is implied that the perceiver mediates his own perception, which isn’t mediation at all. — NOS4A2

Indirect realists recognise that experience does not extend beyond the body, and so that distal objects are not constituents of experience, and so that the properties of the experience are not the properties of the distal objects. The relationship between experience and distal objects is nothing more than causal. As such there is an epistemological problem of perception and so direct realism fails, as direct realism was the attempt to explain why there isn't an epistemological problem of perception. -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismMust they, though? — jkop

Assuming that conscious experience is causally determined then yes. Given the same input (the stimulus) and the same processing (the central nervous system) then the same output (the experience) will result. Different outputs require either different processing or different inputs.

I'd say seeing a colour is neither right nor wrong, it's just a causal fact, how a particular wavelength in the visible spectrum causes a particular biological phenomenon in organisms that have the ability to respond to wavelengths in the visible spectrum. — jkop

That's the exact point I'm making, except I'm extending it to something that might usually be considered a "primary" quality – visual orientation. -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismYou postulate that we (humans) have the experience with our kind of eyes / brain, so how come you say that another organism must have differently working eyes and brain to have the same experience? — jkop

For them to see when standing what we see when hanging upside down it must be that their eyes and/or brain work differently.

What do you mean by saying that photoreception is subjective yet not special?

I’m saying that whether or not sugar tastes sweet is determined by the animal’s biology. It’s not “right” for it to taste sweet and “wrong” for it to taste sour. Sight is no different. It’s not “right” that light with a wavelength of 700nm looks red and not “right” that the sky is “up” and the ground “down”. These are all just consequences of our biology, and different organisms with different biologies can experience the world differently. -

Indirect Realism and Direct Realism

I don't see how that's at all relevant to my point.

Consider some animal that has eyes in the palms of its hands rather than in its head. To see the "correct" orientation of the world, must its fingers point towards the sky, towards the ground, or towards the side?

Or is the very premise that there's a "correct" orientation mistaken? -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismThe argument that there is no "correct" orientation or "correct' way of perceiving the world seems to me help make the case for direct realism rather than for indirect realism. Direct realists think it is possible for our perceptions of the world to be veridical, despite there being no "correct" way to perceive it (whatever that might mean). It is indirect realists who seem to think it is impossible for our perceptions to be veridical, and this seems to be because we either do not perceive the world "correctly" or because we cannot know whether we perceive the world "correctly". — Luke

My understanding is that direct realism entails A Naïve Realist Theory of Colour (and related theories on other sense modalities like smell and taste). The naive realist theory of colour is incorrect. Colours are a mental phenomenon caused by the brain reacting to the eyes being stimulated by photons. The same principle holds for other sense modalities. Therefore, direct realism is false.

If some self-proclaimed direct realist rejects the naive realist theory of colour then it isn't clear to me what the word "direct" means to them, or how their position is in conflict with the indirect realist who also rejects the naive reality theory of colour.

I'm guessing it's something to do with this. We have phenomenological indirect realists and semantic direct realists talking past each other. -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismNow, it's true that when your turn you head all the way upside down, some illusion regarding the orientation of the external world may ensue. — Pierre-Normand

There is no illusion.

There are two astronauts in space 150,000km away. Each is upside down relative to the other and looking at the Earth. Neither point of view shows the "correct" orientation of the external world because there is no such thing as a "correct" orientation. This doesn't change by bringing them to Earth, as if proximity to some sufficiently massive object makes a difference.

Also imagine I'm standing on my head. A straight line could be drawn from my feet to my head through the Earth's core reaching some other person's feet on the other side of the world and then their head. If their visual orientation is "correct" then so is mine. The existence of a big rock in between his feet and my head is irrelevant.

See also an O'Neill cylinder.

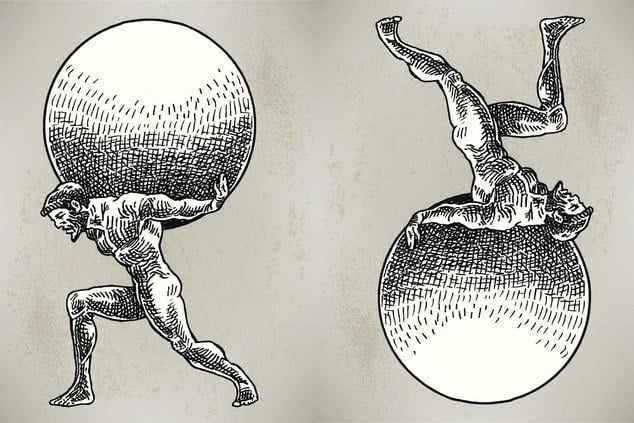

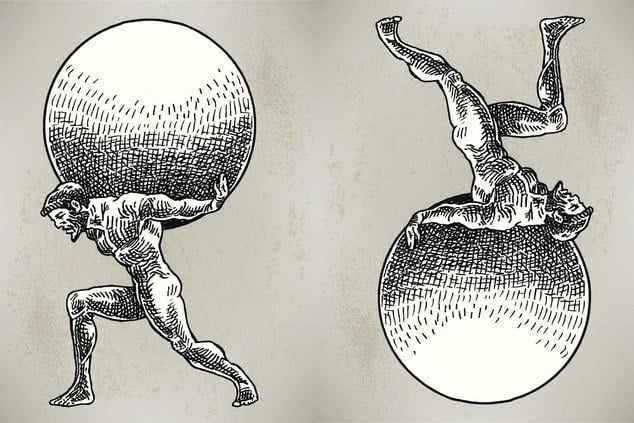

And just for fun: is Atlas carrying the Earth or lying on it with his legs in the air? We can talk about which of Atlas or the Earth has the strongest gravitational pull, but that has nothing to do with some presumptive “correct” visual orientation.

-

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismWorld maps are indeed conventional, like many other artificial symbols, but misleading as an analogy for visual perception. Visual perception is not an artificial construct relative conventions or habits. It is a biological and physical state of affairs, which is actual for any creature that can see.

For example, an object seen from far away appears smaller than when it is seen from a closer distance. Therefore, the rails of a railroad track appear to converge towards the horizon, and for an observer on the street the vertical sides of a tall building appear to converge towards the sky. These and similar relations are physical facts that determine the appearances of the objects in visual perception. A banana fly probably doesn't know what a rail road is, but all the same, the further away something is the smaller it appears for the fly as well as for the human. — jkop

That's not relevant to what I'm saying.

When I hang upside down and so see the world upside I'm not hallucinating or seeing an illusion; I am having a "veridical" visual experience.

It is neither a contradiction, nor physically impossible, for some organism to have that very same veridical visual experience when standing on their feet. It only requires that their eyes and/or brain work differently to ours.

Neither point of view is "more correct" than the other.

Photoreception isn't special. It's as subjective as smell and taste. -

Direct and indirect photorealismDirect and indirect then both apply, in different senses: direct because connecting in an unbroken chain; indirect because involving links and transformations. — bongo fury

What would a "broken" chain be? Is seeing my face in a mirror an "unbroken" chain and so "direct" perception of my face? Is watching football on TV an "unbroken" chain and so "direct" perception of a football match?

I guess, the same work as "actually"? — bongo fury

So when you say that the flower's properties are "directly presented in and constitutive of the photo" you're saying that the flower's properties are actually presented in and constitutive of the photo? Well that's factually incorrect. The flower (and its properties) is a thousand miles away, and cannot exist in two locations at once.

Also, the flower is organic whereas the photo isn't, so I'm not even sure which properties you're claiming to be "presented in and constitutive of the photo". -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismBut isn't that our eyes? Our eyes receive light physically upside down. Our brains spin it around.

If some creature had upside down eyes relative to us, it would be up to their brain how they experience the visual orientation, not necessarily the way their eyes are positioned. — flannel jesus

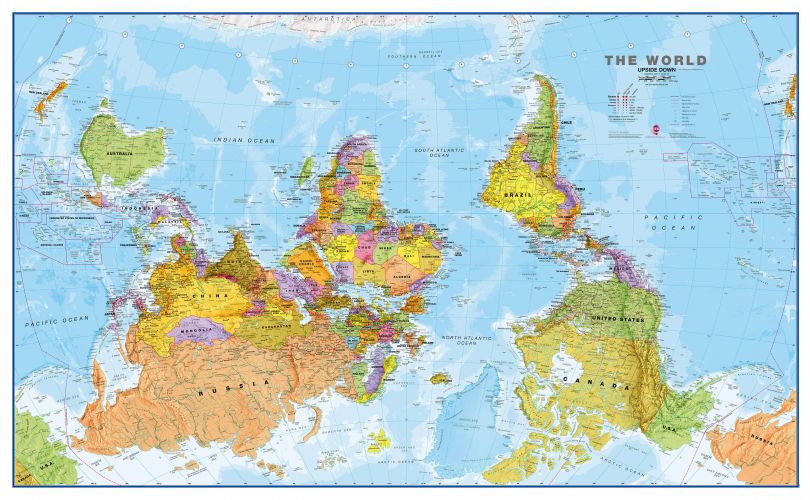

What your eyes and brain do when hanging upside down is conceivably what some other organism's eyes and brain do when standing on their feet. Neither point of view is privileged. Much like an "upside down" globe is as a valid as the traditional globe, an "upside down" perspective is as valid as the one you're familiar with.

The below is only "upside down" as a matter of convention.

-

Direct and indirect photorealismmany of its properties, and its downstream physical effects, are indeed directly presented in and constitutive of the photo — bongo fury

What do you mean by the flower’s properties being directly presented? What is the word “directly” doing here?

The photo is hung up on my wall. The flower is 1,000 miles away. There is a very literal spatial separation between the photo and the flower. The flower and its properties do not exist in two locations at once.

It seems to me that you are just needlessly, and meaninglessly, throwing in the word “directly”. Whatever you mean by “direct” here isn’t what is meant when debating the epistemological problem of perception.

You might say that the photo resembles the flower (as seen in real life), but then any indirect realist can agree. -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismIn your thought experiment, somehow, this relative inversion between the contents of the two species' (or genders') respective visual experiences is a feature of their "private" qualia and is initially caused by the orientation of their eyes. But what does it even mean to say that an animal was born with its eyes "upside down"? Aren't eyes typically, functionally and anatomically, symmetrical across the horizontal plane? And since our eyes are camera obscura that already map the external world to "upside down" retinal images, aren't all of our eyes already "upside down" on your view? — Pierre-Normand

Why is it that when we hang upside down the world appears upside down? Because given the physical structure of our eyes and the way the light interacts with them that is the resulting visual experience. The physiological (including mental) response to stimulation is presumably deterministic. It stands to reason that if my eyes were fixed in that position and the rest of my body were rotated back around so that I was standing then the world would continue to appear upside down. The physics of visual perception is unaffected by the repositioning of my feet. So I simply imagine that some organism is born with their eyes naturally positioned in such a way, and so relative to the way I ordinarily see the word, they see the world upside down (and vice versa).

It makes no sense to me to claim that one or the other point of view is “correct”. Exactly like smells and tastes and colours, visual geometry is determined by the individual’s biology. There’s no “correct” smell of a rose, no “correct” taste of sugar, no “correct” colour of grass, no “correct” visual position, and no “correct” visual size (e.g everything might appear bigger to me than to you – including the marks on a ruler – because I have a more magnified vision). Photoreception isn't special. -

A discussion on Denying the AntecedentDeductive reasoning is when the conclusion necessarily follows from the premises.

Inductive reasoning is when the conclusion doesn't necessarily follow from the premises but is nonetheless reasonable to infer.

For example, "if you don't stop shouting then I am going to turn the car around" doesn't necessarily entail that if the children stop shouting then the mother won't turn the car around, but it is nonetheless a reasonable inference. As such it is a case of inductive reasoning. -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismPaintings and human texts indeed (often) purport to be about objects in the world. But this purport reflects the intentions of their authors, and the representational conventions are established by those authors. In the case of perception, the relation between the perceptual content and the represented object isn't likewise in need of interpretations in accordance with conventions. Rather, it is a matter of the experience's effectiveness in guiding the perceiver's actions in the world. You can look at a painting and at the scenery that the painting depicts side by side, but you can't do so with your perception of the visual world and the visual world itself. — Pierre-Normand

There are paintings of things that no longer exist and books written by dead authors about past events. So in which presently existing things is such intentionality found?

But I don't even think that intentionality has any relevance to the debate between direct and indirect realism, which traditionally are concerned with the epistemological problem of perception; can we trust that experience provides us with accurate information about the nature of the external world? If experience doesn't provide us with accurate information about the nature of the external world (e.g because smells and tastes and colours are mental phenomena rather than mind-independent properties) then experience is indirect even if the external world is the intentional object of perception.

After struggling for a couple of days with ordinary manipulation tasks and walking around, the subject becomes progressively skillful, and at some point, their visual phenomenology flips around. — Pierre-Normand

Does it actually "flip around", or have they just grown accustomed to it? I've read about the experiments in the past and the descriptions are ambiguous.

In the case that they do actually "flip around", is that simply the brain trying to revert back to familiarity? If so, a thought experiment I offered early in this discussion is worth revisiting: consider that half the population were born with their eyes upside down relative to the other half. I suspect that in such a scenario half the population would see when standing what the other half would see when hanging upside down. They each grew up accustomed to their point of view and so successfully navigate the world, using the same word to describe the direction of the sky and the same word to describe the direction of the ground. What would it mean to say that one or the other orientation is the "correct" one, and how would they determine which orientation is correct?

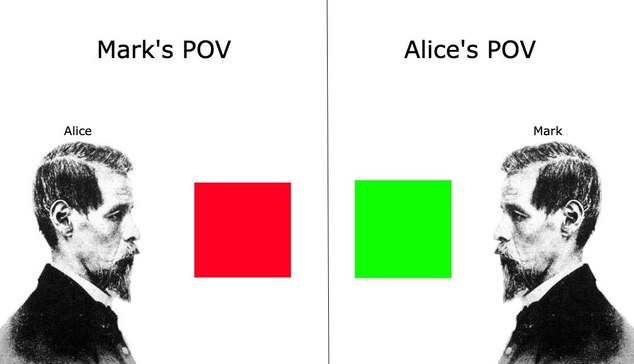

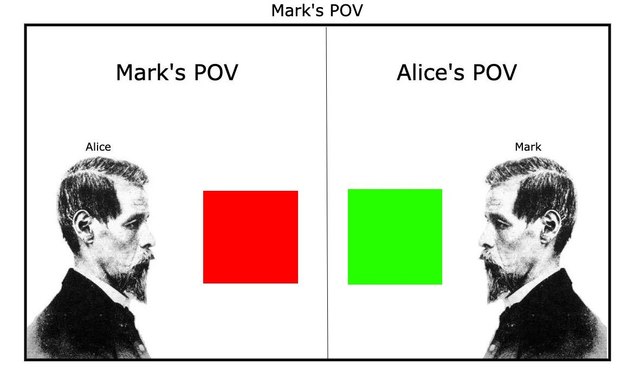

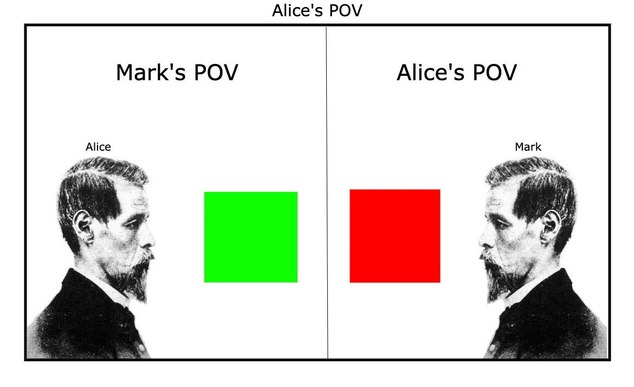

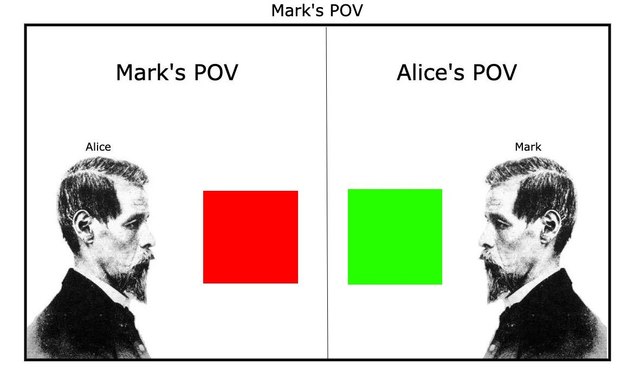

I don't think that visual geometry is any different in kind to smells and tastes and colours. The distinction between "primary" and "secondary" qualities is a mistaken one (they're all "secondary"). But if I were to grant the distinction then how would you account for veridical perception in the case of "secondary" qualities? Taking this example from another discussion, given that in this situation both Alice and Mark can see and use the box, describe it as being the colour "gred" in their language, and agree on the wavelength of the light it reflects, does it make sense to say that one or the other is having a non-veridical (colour) experience, and if so how do they determine which? Or what if sugar tastes sweet to Alice but sour to Mark? Is one having a non-veridical taste?

Or perhaps “veridicality” only applies to visual geometry? If so then what makes vision (and specifically this aspect of vision) unique amongst the senses? To me it’s all just a physiological response to sense receptor stimulation. -

Indirect Realism and Direct Realismit is the visible property of the rain that determines the phenomenal character of the visual experience — jkop

I don't think anyone disagrees, but that doesn't say anything to address either direct or indirect realism. It simply states the well known fact that the physics of cause and effect is deterministic (at the macro scale).

Given my biology, when light of a certain wavelength stimulates the rods and cones in my eyes I see the colour red, and when certain chemicals stimulate the taste buds in my tongue I taste a sweet taste. Given a different biology I would see a different colour and taste a different taste. -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismBecause perception is direct. — jkop

I don't see how that answers my question. If visual experience is one thing and rain is another thing then why can't you separate them?

Or are you saying that rain and the visual experience are the same thing? Even though visual experience occurs within the body and the rain exists outside the body? -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismI can't separate my visual experience from the rain — jkop

Why not? Visual experience does not extend beyond the brain/body, but the rain exists beyond the body, and so they must be separate. -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismAs I am also attempting to explain, it is the indirect realists who are facing a challenge in explaining how the inner mental states that we enjoy can have intentional (referential) relations to the objects that they purport to represent that are apt to specify the conditions for those experiences to be veridical. — Pierre-Normand

I suspect the answer to that is the answer that explains how paintings can have intentional relations to the objects that they purport to be of or how words can have intentional relations to the objects that they purport to describe.

On the disjunctivist view, the phenomenal character of this experience isn't exhausted by an inner sensation or mental image. Rather, it consists in your very readiness to engage with the apple — Pierre-Normand

What is the difference between these two positions?

1. The phenomenal character of experience includes the inner sensation, the readiness to engage with the apple, and the expectation that we can reach it.

2. The phenomenal character of experience is exhausted by an inner sensation. In addition to the phenomenal character of experience, we are also ready to engage with the apple and expect to reach it.

The disjunctivist, in contrast, can ground perceptual content and veridicality in the perceiver's embodied capacities for successful interaction with their environment. — Pierre-Normand

I think there might be some degree of affirming the consequent here. That if perception is veridical then we will be successful isn't that if we are successful then perception is veridical.

If I am blindfolded then I can successfully navigate a maze by following verbal instructions, or simply by memorising the map beforehand. Or perhaps I wear a pair of VR goggles that exactly mirrors what I would see without them.

I think something other than "successful interaction" is required to define the difference between a veridical and non-veridical experience. -

Wondering about inverted qualiaAlso I don't think language is at all relevant and is in fact a red herring. Presumably deaf, illiterate mutes who aren't blind can see colours.

It's possible that the colour that one deaf, illiterate mute sees some object to be isn't the colour that some other deaf, illiterate mute sees the object to be.

With respect to physicalism, the question is whether or not this difference in colour perception requires differences in biology, and with respect to naive realism, the question is whether or not one of them is seeing the "correct" colour (in the sense that that colour is a mind-independent property of the object). -

Wondering about inverted qualiaFirst of all, does it make sense to speak of shared sensations? — sime

Possibly shared type, but not shared token. -

Wondering about inverted qualia

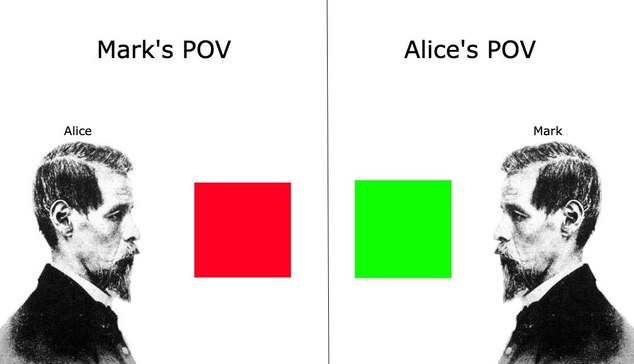

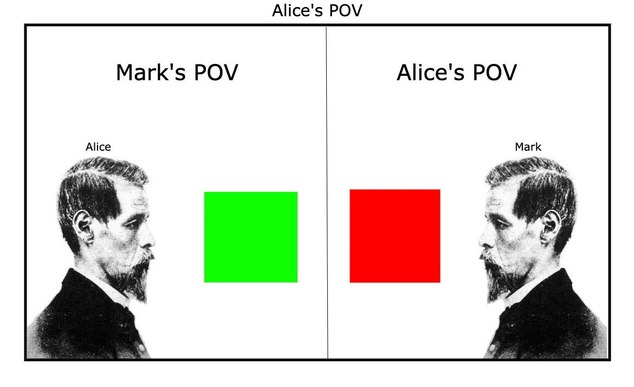

The claim is that if it's conceivable that Mark and Alice have no relevant physical differences and yet see different colours despite looking at the same object then colours are non-physical.

And just for fun let's carry on from this and assume that the box in question reflects light with a wavelength of 700nm. If we show the above image to Mark and Alice then this is what they will see:

Both Mark and Alice will agree that the left hand side of the image shows the colour of the box as seen in real life (named "gred" in their language), although Alice will disagree with the right hand side being labelled "Alice's POV". -

Who is morally culpable?Yes it does. He had to. — Hanover

Fair. I suppose a more appropriate response is to say that any claim that we should or shouldn't do something is true only if hard determinism is false, and so if hard determinism is true then the claim that we shouldn't hold people responsible is not true. -

Who is morally culpable?We assign culpability to people who are not actually culpable. — Truth Seeker

Yes. But asking if we should makes no sense, given that we don't have a choice. -

Who is morally culpable?I think hard determinism is true. — Truth Seeker

If hard determinism is true then we don't choose to hold people responsible; we just do. Asking if we should makes no sense. -

Who is morally culpable?If hard determinism is true, then no one is morally culpable.

I am not sure if this follows. Consider a basic sketch of compatibalist free will as one's relative degree of self-determination: — Count Timothy von Icarus

Compatibilism is soft determinism, not hard determinism. If hard determinism is true then compatibilism is false. -

Who is morally culpable?However, if hard determinism is true, then it is inevitable that X murdered Y. In that case, X is not actually culpable. The actions of X are as determined and inevitable as death by an earthquake. We don't hold earthquakes culpable for murder, but we hold adult humans of sound mind culpable for murder. Should we though? — Truth Seeker

Your question presupposes that we can choose to hold people responsible or not, i.e. that hard determinism is false. If hard determinism is false then we should hold people responsible. -

The Vulnerable World HypothesisThe question is, does scientific progress ultimately lead to self-destruction or major destabilization of human civilization? — SpaceDweller

I suspect so. Global travel increases the likelihood of a global pandemic, excessive industrialisation increases the use of non-renewable resources and the likelihood of harmful climate change, and automated systems controlled by an artificial intelligence is vulnerable to coding errors and sabotage.

I suspect we die off before we're capable of interstellar colonisation.

We'd need excessive regulation to avoid that, but capitalism won't allow it. -

Indirect Realism and Direct Realismyou have internal representations that map to objective features of it. — hypericin

That’s an open question too. I don’t think colours and sounds and smells and tastes “map” to objective features at all, and certainly not in a sense that can be considered “representative.”

The connection between distal objects and sensory precepts is nothing more than causal, determined in part by each individual’s biology.

The “objective” world is a mess of quantum fields, far removed from how things appears to us. -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismI’ve only seen red things. — NOS4A2

I see red things when I dream and hallucinate. Those with synesthesia might see red things when they listen to music with their eyes closed in a dark room. These are visual percepts. They occur in ordinary waking experience too. The colour red as present in these visual percepts is not a property of distal objects.

I have no problem understanding the argument, only the entities we’re dealing with. And that the indirect realist cannot point to any of these entities, describe where they begin and end, describe how and what they perceive, nor ascribe to them a single property, is enough for me to conclude that they are not quite sure what they are talking about, and that this causal chain and the entities he puts upon them are rather arbitrary. — NOS4A2

They can point to the visual cortex and temporal lobe. Visual percepts and rational awareness are either reducible to the activity in the brain or supervene on them. But the hard problem of consciousness hasn't been resolved yet so it's still an open matter.

If you want an account that does not assume anything like mental properties or a first person perspective then the claim is that perception is the neurological processing of certain streams of information. By physical necessity any information processed by the brain is located in the brain. The unconscious involvement of the eyes may be a prerequisite (if you deny that we see things when we dream and hallucinate) but it itself is not a constituent of conscious perception - and the distal object itself is certainly not a constituent of it either.

Hence the epistemological problem of perception. The brain has no direct access to the information that constitutes distal objects. We have to assume and hope that the information it directly processes is capable of accurately informing us about the existence and nature of those distal objects. -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismBut again, your position lacks a referent. — NOS4A2

It's what the sighted have and the blind (including those with blindsight) don't have. It's what occurs when we dream and hallucinate.

As it stands, no intermediary exists between perceiver and perceived. — NOS4A2

If you define "perceiver" in such a way that it includes the entire body and "perceived" in such a way that it includes the body's immediate environment then what you say here is a truism.

But this isn't what indirect realists mean which is why you've misinterpreted (or misrepresented) them.

You might not believe in something like "rational awareness" and "sensory percepts" but the indirect realist does, and their claim is that sensory percepts are the intermediary that exist between rational awareness and distal objects. The colour red is one such sensory percept. A sweet taste is another. -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismThe odour molecules are a part of that unperceived causal chain. — Luke

The odour molecules are perceived. I smell them. -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismYou seem you construe the perception as of an intermediary sensation which lays "between" the distal object and the perception, and thus perception is not of the distal object and thus is indirect. — fdrake

As referenced in the aforementioned article Direct Perception: The View from Here, "the view that perception is direct holds that a perceiver is aware of or in contact with ordinary mind-independent objects, rather than mind-dependent surrogates thereof."

So, to say that my perception is directly of a distal object is to say that I am directly aware of a distal object.

I do not believe that I am directly aware of a distal object. I believe that I am directly aware only of my sensations. Therefore, my perception is not of a distal object and so therefore perception is not direct.

@Luke's position seems to be that perception is direct if sensations are (direct?) representations of distal objects.

The first issue with this is that it doesn't explain what it means for a sensation to be a representation of a distal object.

The second issue with this is that it doesn't explain what determines that the sensation is a representation of that distal object rather than of some other distal object, or even of the proximal stimulus (e.g. why is the sensation a representation of the cake in the oven rather than a representation of the odour molecules in the air).

The third issue with this is that it is prima facie consistent with the indirect realist's claim that we are not directly aware of distal objects, as it may be both that a) we are directly aware only of sensations and that b) sensations are (direct?) representations of distal objects.

The fourth issue with this is that (as mentioned in the SEP article) his position (and any other non-naive so-called "direct" realism) argues that "we directly perceive ordinary objects" and that "we are not ever directly presented with ordinary objects." Either his position equivocates on the meaning of "direct" or it contradicts itself. -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismYou don't directly perceive images formed by your brain. Those images are your perceptions. — Luke

This is where people are getting lost in the grammar.

I see colours. Colours are a visual sensation.

If you don't like the phrasing of the conclusion "therefore I see a visual sensation" then just don't use it. It is still the case that I see colours and that these colours are a visual sensation, not properties of distal objects. The same for every other feature of visual and auditory and olfactory experience. That's the substance of indirect realism.

Perhaps adopt something like adverbialism. Rather than "I see colours" being a verb and a noun it's a verb and an adverb. Maybe that's the best way to understand "the schizophrenic hears voices" or "I saw a mountain in my dream." In each case, whatever is the direct object of perception it isn't some distal object. Waking, non-hallucinatory experiences are of the same kind, and only differ in that there is some appropriate distal cause. -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismDid you read all of this article? It argues in favour of direct realism. — Luke

Yes, I wasn't offering it as a defence of indirect realism. I was offering it as an explanation that the problem of perception concerns whether or not we are directly aware of distal objects and their properties.

The causal chain is prior to the visual percept. If, by "visual percept", you mean a "perception" of a distal object, then it cannot be a perception of the causal chain, since the causal chain is prior to, and is the cause of, that perception.

Surely, the intermediary - whatever it is - does not provide a direct perception of its distal object, and allows only a representation of the object to be perceived without allowing the distal object to be immediately perceived.

You do not perceive the causal chain that produces your visual percepts. — Luke

I'm not saying that we perceive the causal chain. I'm simply trying to explain the inconsistency in your position. You say that there are no intermediaries between visual percepts and some distal object, and yet there are; the odour molecules in the air are an intermediary between the visual percept and the cake in the oven.

I'm also trying to understand why you say that the perception is of the cake in the oven, and not of the odour molecules, given that it is the odour molecules that stimulate the sense receptors in the nose. Clearly the causal chain has something to do with the object of perception under your account given that, presumably, the object of perception is never some distal object that has no role in the causal chain (e.g. you never see something happening on Mars). So how do you determine which object that is a part of the causal chain is the direct object of perception? You just say it's the cake without explaining why it's the cake.

At least if you were to say that the object of perception is the odour molecules you could defend it by saying that the odour molecules are the proximal stimulus. There is at least some sense in such a claim. -

Indirect Realism and Direct Realismit just isn't the case that you see mountains in your dreams. It would be more accurate to say that you dream of mountains, in my opinion. — NOS4A2

Dreams, and hallucinations, have various perceptual modes. I see things and hear things and smell things. The things I see and hear and smell when I dream, and hallucinate, are not distal objects.

Light is of the world. The eye is of the perceiver. It just doesn't make sense to me that the perceiver can be the intermediary for himself. The contact is direct, so much so that light is absorbed by the eye, and utilized in such an intimate fashion that there is no way such a process could be in any way indirect, simply because nothing stands between one and the other.

...

Yes, more than just eyes are involved in vision. I would argue it requires the whole body, give or take. A functional internal carotid artery, for instance, which supplies blood to the head, is required for sight, as are the orbital bones and the muscles of the face. Sight requires a spine, metabolism, digestion, water, and so on. Because of this, I believe, the entity "perceiver" must extend to the entirety of the body. In any case, I cannot say it can be reduced to some point behind the eyes. — NOS4A2

There is such a thing as visual percepts. It's what the blind (even with functioning eyes) lack. It's what occurs when we dream and hallucinate, as well as when awake and not hallucinating. They come into existence when the relevant areas of the visual cortex are active. The features of these percepts are not the distal objects (or their properties) that are ordinarily the cause of them. The features of these percepts is the only non-inferential information given to rational thought; that inform our understanding. The relationship between these percepts and distal objects is in a very literal physical sense indirect; there are a number of physical entities and processes that sit between the distal object and the visual percept in the causal chain.

This is what indirect realism is arguing. It's not arguing anything like "the human body indirectly responds to sensory stimulation by its environment" or "the rods and cones in the eye react to something inside the head" which seems to be your (mis)interpretation of the position. -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismSince they point outward, you cannot see into your own skull, for instance. — NOS4A2

The indirect realist doesn’t claim that we see into own own skull. You’re misrepresenting what is meant by seeing something or feeling something. I feel pain, I see mountains in my dream. Nothing about this entails anything like the sense organs “pointing” inwards or anything like that.

In most cases the sense organs play a causal role in seeing and feeling and smelling, but “I see X” doesn’t simply mean “the sense receptors in my eye have been stimulated by some object in the environment.”

It’s direct because at no point in your chain is there any intermediary. I would distill it as such: — NOS4A2

There literally are intermediaries. Light is an intermediary between the table and my eye. My eye is an intermediary between the light and my brain, etc.

Or when I point to a sensation I point to my body. — NOS4A2

That doesn’t make it right to. We know that people with certain brain disorders are blind even though they have functioning eyes, and we know that people can be made to see things by bypassing the eyes and directly stimulating the brain, so clearly whatever vision is it sits somewhere behind the eyes, either in the visual cortex or in some supervenient mental phenomenon. -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismSince most of his senses point outward one would assume he mostly perceives in an outward direction — NOS4A2

What does this mean?

But indirect realism undermines this relationship. It claims that even though the senses point outward, and interact directly with the rest of the world, his perception remains inward. — NOS4A2

The indirect realist recognises that in most cases the causal chain of perception is:

distal object → proximal stimulus → sense receptor → sensation → rational awareness

The indirect realist also recognises that the qualities of the sensation are not properties of the distal object (although in some accounts the so-called "primary qualities" of the sensation, such as visual geometry, "resemble" the relevant properties of the distal object).

So in what sense is the relationship between rational awareness (or even sensation) and the distal object direct?

And given that I see things when I dream and hallucinate, sometimes the casual chain is just:

sensation → rational awareness

What is the direct object of perception in these cases? Why would the involvement of some distal object, proximal stimulus, and sense receptor prior to the sensation change this? -

Indirect Realism and Direct Realism

-

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismAt this point I don't know if we're just speaking different languages. You seem to have a very different understanding of the meanings of the words "awareness", "perception", "direct", and "intermediary".

-

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismThe relevant issue is about perceptions of objects, not awareness of sensations. The directness or indirectness of awareness is irrelevant. — Luke

The directness or indirectness of awareness is the very issue under discussion. I don't understand what you think "perception" or "awareness" mean.

Let's take Direct Perception: The View from Here as a starting point:

The view that perception is direct holds that a perceiver is aware of or in contact with ordinary mind-independent objects, rather than mind-dependent surrogates thereof.

...

The position that perception is direct begins with the common sense intuition that everyday perceiving involves an awareness of ordinary environmental situations.

...

The indirect position, in contrast, argues that the common sense intuition of perception as the direct awareness of environmental objects is naïve. Upon closer examination, a perceiver is actually only in direct contact with the proximal stimulation that reaches the receptors, or with sense-data, or with the sensations or internal images they elicit - but not with the distal object itself.

...

The perceiver is directly aware only of some mind-dependent proxy— the sense-data, internal image, or representation - and only indirectly aware of the mind-independent world.

How do the causes of a perception act as an intermediary between the perception and its object? — Luke

In the very literal sense that light is the literal physical intermediary between my eyes and some distal object, "carrying" whatever "information" it can about that distal object into my eyes. If the lights are turned off then I don't see anything.

So, sensations are an intermediary between rational awareness and the proximal stimulus and the proximal stimulus is an intermediary between the sense receptors and the distal object. Given this, there is no meaningful sense in which we are directly aware of the distal object. Therefore, perception is not direct. -

Indirect Realism and Direct Realism@Luke Also, you missed something I added in:

What if, say, the cake has since been taken away and eaten, but the smell lingered. What am I (directly) smelling now? Nothing? The contents of my family's stomachs in the other room? Odour molecules in the air?

Michael

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum