Comments

-

Sleeping Beauty ProblemIn the cosmopolitan encounter case, the random distributions of citizens in the street at any given time (with, on average, twice as many Tunisians out) directly result in twice as many encounters with Tunisians. — Pierre-Normand

Because of what I said before:

A1. there are twice as many Tunisian walkers as Italian walkers

A2. therefore, if I go out and meet at random one of the walkers then I am twice as likely to meet a Tunisian walker

A3. therefore, there will be twice as many Tunisian-walker meetings

In Sleeping Beauty's case:

B1. Sleeping Beauty wakes up twice as often if the coin lands tails

B2. the coin is equally likely to land tails

B3. therefore, there will be twice as many tails awakenings

This argument is sound and fully explains the betting outcome. Your conclusion that "therefore, if Sleeping Beauty wakes up then the coin is twice as likely to have landed tails" just doesn't follow.

What would follow is "therefore, if I pick at random one of Sleeping Beauty's awakenings then it is twice as likely to be a tails awakening," but given that the experiment isn't conducted this way it doesn't make sense for Sleeping Beauty to reason this way to determine her credence. -

Sleeping Beauty ProblemThe conclusion doesn't follow because, while the biconditional expressed in P3 is true, this biconditional does not guarantee a one-to-one correspondence between the set of T-interviews and the set of T-runs (or "T-interview sets"). Instead, the correspondence is two-to-one, as each T-run includes two T-interviews. This is a central defining feature of the Sleeping Beauty problem that your premises fail to account for. — Pierre-Normand

That doesn't mean that the credence isn’t transitive. My premises "fail" to account for it because it's irrelevant.

A iff B

P(B) = 1/2

Therefore, P(A) = 1/2

The conclusion has to follow.

See also what I said before:

-

The Andromeda Paradox

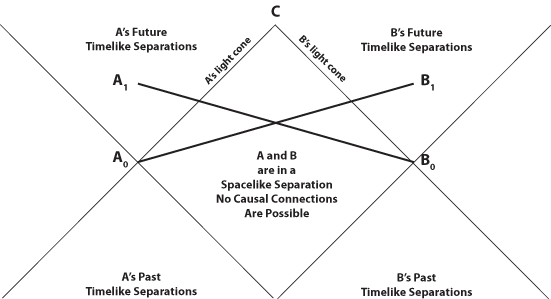

(1) Relativity of simultaneity + all observers’ 3D worlds are real at every event = block universe

The argument on that page accepts that relativity of simultaneity is true but claims that "all observers’ 3D worlds are real at every event" is false because "Our intuitions don’t really know how to deal with “elsewhere”; it’s neither fixed and certain, since we can’t predict what happens there with certainty based only on the data in our past light cone, nor changeable since we can’t causally affect what happens there; we can only causally affect events in our future light cone."

This is a non sequitur. That an event cannot be predicted with certainty isn't that the event isn't certain. Or to phrase it another way, even if we cannot know (with certainty) whether or not "there is intelligent alien life in the Andromeda Galaxy" is true, it doesn't follow that it isn't true (or false).

And nobody is suggesting that it's changeable. In fact if the block universe is true then nothing is changeable; it just is what it is.

So the Andromeda Paradox is the claim that if "aliens are leaving Andromeda en route to Earth" is (unknowably) true in some reference frame then "aliens will leave Andromeda en route to Earth" is (unknowably) true in my reference frame.

And furthermore, that for every proposition "X will happen" either there is some reference frame A in my present elsewhere such that "X is happening" is (unknowably) true, and so "X will happen" is (unknowably) true in my reference frame, or there is no reference frame A in my present elsewhere such that "X is happening" is (unknowably) true, and so "X will happen" is (unknowably) false in my reference frame. -

Donald Trump (All General Trump Conversations Here)Donald Trump Fantasized About Having Sex With Ivanka, New Book Says

“Aides said he talked about Ivanka Trump’s breasts, her backside, and what it might be like to have sex with her, remarks that once led [former Chief of Staff] John Kelly to remind the president that Ivanka was his daughter,” Taylor, who served as a Department of Homeland Security chief of staff under Trump, wrote in his book.

“Afterward, Kelly retold that story to me in visible disgust,” Taylor writes. “Trump, he said, was ‘a very, very evil man.’

Surprising no-one. -

Sleeping Beauty Problem

We have two different experiments:

1. A is woken once if heads, twice if tails

2. A is woken once if heads, A and B once each if tails

Your version of the experiment is comparable to the second experiment, not the first. Your case of HH is equivalent to the case that the coin landed heads and I am B. The very fact that I'm being asked my credence allows me to rule out one of the non-zero prior probabilities, i.e. P(HH) = 1/4 and P(Heads and B) = 1/4.

The second experiment is not equivalent to the first experiment. In the first experiment there is no non-zero prior probability that I can rule out when being asked my credence.

Given that I'm guaranteed to be woken up if heads in the first experiment but not the second (and guaranteed to be woken up if tails in both experiments) it makes sense that my credence in heads is greater in the first experiment than in the second. If I'm less likely to be woken up if heads then it's less likely to be heads if I'm woken up. -

Sleeping Beauty ProblemP1. If I am assigned at random either a H-interview set or a T-interview set then my interview set is equally likely to be a H-interview set

P2. I am assigned at random either a H-interview set or a T-interview set

P3. My interview is a H-interview iff my interview set is a H-interview set

C1. My interview is equally likely to be a H-interview

The premises are true and the conclusion follows, therefore the conclusion is true.

However, consider:

P4. If my sitter is assigned at random either a H-interview or a T-interview then his interview is half as likely to be a H-interview

P5. My sitter is assigned at random either a H-interview or a T-interview

P6. My interview is a H-interview iff my sitter's interview is a H-interview

C2. My interview is half as likely to be a H-interview

Prima facie the premises are true and the conclusion follows, therefore prima facie the conclusion is true. However, C1 and C2 are contradictory, therefore one of the arguments must be unsound.

Let's say that my sitter happens to be John:

P7. If John is assigned at random either a H-interview or a T-interview then his interview is half as likely to be a H-interview

P8. John is assigned at random either a H-interview or a T-interview

P9. My interview is a H-interview iff John's interview is a H-interview

C3. My interview is half as likely to be a H-interview

The issue is with P9. My interview is not biconditional with John's interview given that he is not guaranteed to be my sitter. That second argument commits a fallacy. P4 and P5 are true only under a de re interpretation of "my sitter" and P6 is true only under a de dicto interpretation.

This is why the participant shouldn't update his credence to match his sitter's. -

Sleeping Beauty ProblemI introduce the additional premise(s) because this is a non sequitur:

A1. there are twice as many Tunisian walkers as Italian walkers

A2. I am twice as likely to meet a Tunisian walker

If all the Tunisian walkers are in one area of the town but I'm walking in another then the conclusion is false. If, unknown to me, all the Tunisian walkers are wearing red and all the Italians wearing blue and I'm told to meet someone wearing blue if a coin lands heads or red if tails then the conclusion is false. If I don't go out to meet anyone then the conclusion is false. The experiment needs to be set up in such a way that the walkers are randomly distributed throughout the town and that I meet at random any one of the walkers. Only when this setup is established as a premise will the conclusion follow:

A1. there are twice as many Tunisian walkers as Italian walkers

A2. if I meet a walker at random from a random distribution of all walkers then I am twice as likely to meet a Tunisian walker

Similarly, this is a non sequitur:

B1. there are twice as many T-interviews as H-interviews

B2. my interview is twice as likely to be a T-interview

You would instead need something like:

C1. there are twice as many T-interviews as H-interviews

C2. if my interview is randomly assigned from the set of all interviews then my interview is twice as likely to be a T-interview

But this reasoning doesn't apply to Sleeping Beauty because her interview isn't randomly assigned from the set of all interviews.

For Sleeping Beauty the correct argument is the one that properly sets out the manner in which the experiment is conducted:

D1. there are an equal number of T-interview sets as H-interview sets

D2. If I am assigned at random either a T-interview set or a H-interview set then my interview set is equally likely to be a T-interview set

D3. I am assigned at random either a T-interview set or a H-interview set

D4. my interview is a T-interview iff my interview set is a T-interview set

D5. my interview is equally likely to be a T-interview

B is fallacious, C is inapplicable, and D is sound, hence why P(Heads|Awake) = 1/2 is the only rational conclusion. The fact that there are twice as many T-interviews as H-interviews is irrelevant. It's a premise from which no relevant conclusion regarding credence can be derived. It's only use is to explain betting outcomes.

In the cosmopolitan situation, the probability of meeting a Tunisian doubles because Tunisians are around twice as often. — Pierre-Normand

This is an ambiguous claim. If there are half as many Tunisians but they go out four times as often but are only out for 10 mins, whereas Italians are out for 20 mins, then it would be that Tunisians are around equally as often as measured by time out. The only way you could get this to work is if the argument is set out exactly as I have done above:

A1. there are twice as many Tunisian walkers as Italian walkers (out right now)

A2. if (right now) I meet a walker at random from a random distribution of all walkers (out right now) then I am twice as likely to meet a Tunisian walker

But there's nothing comparable to "if (right now) I meet a walker at random from a random distribution of all walkers (out right now)" that has as a consequent "then my interview is twice as likely to be a T-interview". -

Sleeping Beauty Problem

We start with the mutually agreeable premise:

P1) there are twice as many T-awakenings

Your conclusion is:

C) T-awakenings are twice as likely

Obviously this is a non sequitur. We need the second premise:

P2) if there are twice as many T-awakenings then T-awakenings are twice as likely

This is something that I disagree with and that you need to prove.

In the case of the meetings we have:

*P1) there are twice as many Tunisian walkers

*P2) if I meet a walker at random then I am twice as likely to meet a Tunisian walker (from *P1)

*P3) I meet a walker at random

*C) I am twice as likely to have met a Tunisian walker (from *P2 and *P3)

In Sleeping Beauty's case we have:

P1) there are twice as many tails interviews

P2) ?

P3) I am in an interview

C) I am twice as likely to be in a tails interview

What is your (P2) that allows you to derive (C)? It doesn't follow from (P1) and (P3) alone. -

Sleeping Beauty ProblemIf, over time, the setup leads to twice as many Tunisian encounters (perhaps because Tunisians wander about twice as long as Italians), then Sleeping Beauty's rational credence should be P(Italian) = 1/3. — Pierre-Normand

I believe this credence is based on fallacious reasoning as explained here.

Her reasoning is: if 1) there are twice as many Tunisian walkers and if 2) I randomly meet one of the walkers then 3) it is twice as likely to be a Tunisian walker.

Given the manner in which the experiment is conducted (2) is false and so this isn't the correct reasoning with which to determine one's credence. -

Sleeping Beauty ProblemYour argument is that: if 1) there are twice as many T-awakenings and if 2) I randomly select one of the awakenings then 3) it is twice as likely to be a T-awakening.

This is correct. But the manner in which the experiment is conducted is such that (2) is false. (3) doesn't follow from (1) alone.

(2) is true for the sitter assigned an interview but not for the participant.

For the participant it is the case that 1) there are twice as many T-awakenings, 2) I randomly select one of the awakening sets, 3) it is equally likely to be a T-awakening set, and so 4) it is equally likely to be a T-awakening. (1) it turns out is irrelevant.

You can't just ignore (or change) the manner in which Sleeping Beauty participates in the experiment, which is what your various analogies do. -

Sleeping Beauty ProblemHowever, you seem to agree that in this scenario, one is twice as likely to encounter a Tunisian. The conclusion that there are twice as many Tunisian-meetings emerges from the premises: (1) there are half as many Tunisians and (2) Tunisians venture out four times more often. This inference is simply an intermediate step in the argumentation, providing an explanation for why there are twice as many Tunisian-meetings. Analogously, the Sleeping Beauty setup explains why there are twice as many T-awakenings. If the reason for twice as many Tunisian-meetings is that Tunisians venture out twice as often (assuming there are an equal number of Tunisians and Italians), then the analogy with the Sleeping Beauty scenario is precise. The attribute of being Tunisian can be compared to a coin landing tails, and encountering them on the street can be paralleled to Sleeping Beauty encountering such coins upon awakening. In the Sleeping Beauty setup, coins that land tails are 'venturing out' more often. — Pierre-Normand

This goes back to my distinction between:

1. One should reason as if one is randomly selected from the set of all participants

2. One should reason as if one's interview is randomly selected from the set of all interviews

In the case where I go out and meet someone on the street it is certainly comparable to 2, and this is why when we consider the sitters it is correct to say that the probability that they are assigned a heads interview is 1/3.

But Sleeping Beauty isn't assigned an interview in the same way. It's not the case that there is one heads interview, two tails interviews, and she "meets" one of the interviews at random (such that P(T interview) = 2/3); instead it's the case that there is one heads interview, two tails interviews, and first she is assigned one of the interview sets at random (such that P(T interviews) = 1/2) and then she "meets" one of the interviews in her set at random.

If we were to use the meetings example then:

1. A coin is tossed

2. If heads then 1 Italian walks the streets

3. If tails then 2 Tunisians walk the streets

4. Sleeping Beauty is sent out into the streets

What is the probability that she will meet a Tunisian? That there are twice as many Tunisians isn't that her meeting a Tunisian is twice as likely. -

Sleeping Beauty ProblemWe have two different experiments:

1. A is woken once if heads, twice if tails

2. A is woken once if heads, both A and B once each if tails

Given that I'm guaranteed to wake up if heads in the first experiment but not guaranteed to wake up if heads in the second experiment (and guaranteed to wake up if tails in both experiments) I think it only reasonable to conclude that P(Heads|Awake) in the first experiment is greater then P(Heads|Awake) in the second experiment.

And given that P(Heads|Awake) = 1/3 in the second experiment I think it only reasonable to conclude that P(Heads|Awake) > 1/3 (i.e. 1/2) in the first experiment. -

Sleeping Beauty Problem

These are two different sets of claims:

A1. there are twice as many Tunisian-meetings because Tunisian-meetings are twice as likely

A2. Tunisian-meetings are twice as likely because there are half as many Tunisians and Tunisians go out four times more often

B1. there are twice as many T-awakenings because T-awakenings are twice as likely

B2. T-awakenings are twice as likely because Sleeping Beauty is woken twice as often if tails

"there are twice as many T-awakenings" is biconditional with "Sleeping Beauty is woken twice as often if tails" and so B uses circular reasoning.

"there are twice as many Tunisian-meetings" isn't biconditional with "there are half as many Tunisians and Tunisians go out four times more often" and so A doesn't use circular reasoning. -

Sleeping Beauty ProblemT-awakenings are twice as likely because, based on the experiment's design, Sleeping Beauty is awakened twice as often when the coin lands tails — Pierre-Normand

This is just repeating the same thing in a different way. That there are twice as many T-awakenings just is that Sleeping Beauty is awakened twice as often if tails. So your reasoning is circular. -

Sleeping Beauty ProblemBut why wouldn't it make sense? For example, if you're an immigration lawyer and your secretary has arranged for you to meet with twice as many Tunisians as Italians in the upcoming week, when you walk into a meeting without knowing the client's nationality, isn't it logical to say that it's twice as likely to be with a Tunisian? — Pierre-Normand

I've since edited my post to make my point clearer. To repeat:

In this case:

1. there are twice as many Tunisian-meetings because Tunisian-meetings are twice as likely

2. Tunisian-meetings are twice as likely because there are half as many Tunisians and Tunisians go out four times more often

This makes sense.

So:

1. there are twice as many T-awakenings because T-awakenings are twice as likely

2. T-awakenings are twice as likely because ...

How do you finish 2? It's circular reasoning to finish it with "there are twice as many T-awakenings".

I am unsure what it is that you are asking here. — Pierre-Normand

Starting here you argued that P(Heads) = 1/3.

So, what do you fill in here for the example of one person woken if heads, two if tails?

-

Sleeping Beauty ProblemHowever, we frequently talk about probabilities of (types of) events that depend on how we interact with objects and that only indirectly depend (if at all) on the propensities of those objects had to actualize their properties. For instance, if there are twice as many Italians as Tunisians in my city (and no other nationalities), but for some reason, Tunisians go out four times more often than Italians, then when I go out, the first person I meet is twice as likely to be a Tunisian. — Pierre-Normand

In this case:

1. there are twice as many Tunisian-meetings because Tunisian-meetings are twice as likely

2. Tunisian-meetings are twice as likely because there are half as many Tunisians and Tunisians go out four times more often

This makes sense.

So:

1. there are twice as many T-awakenings because T-awakenings are twice as likely

2. T-awakenings are twice as likely because ...

How do you finish 2? It's circular reasoning to finish it with "there are twice as many T-awakenings".

The management of the Sleeping Beauty Experimental Facility organizes a cocktail party for the staff. The caterers circulate among the guests serving drinks and sandwiches. Occasionally, they flip a coin. If it lands heads, they ask a random guest to guess the result. If it lands tails, they ask two random guests. The guests are informed of this protocol (and they don't track the caterers' movements). When a caterer approaches you, what are the odds that the coin they flipped landed heads? — Pierre-Normand

To make this comparable to the Sleeping Beauty problem; there are two Sleeping Beauties, one will be woken if heads, two will be woken if tails. When woken, what is their credence in heads? In such a situation the answer would be 1/3. Bayes' theorem for this is:

This isn't comparable to the traditional probem.

Incidentally, what is your version of Bayes' theorem for this where P(Heads) = 1/3? -

The Andromeda ParadoxI'm not seeing it. Light cones concern causal past and causal future. The Rietdijk–Putnam argument and Andromeda Paradox concern events outside the light cone.

If you want to be very precise with the terminology, the Andromeda Paradox shows that some spacelike separated event in my present is some spacelike separated event in some other person's causal future even though that person is also a spacelike separated event in my present. I find that peculiar.

And let's take it further and consider this:

Some event (A1) in my (A0) future is spacelike separated from some event (B0) in someone else's (B1) past, even though this person is spacelike separated from my present. It might be impossible for me to interact with B1 (or for B1 to interact with A1), but Special Relativity suggests that A1 is inevitable, hence why this is an argument for a four-dimensional block universe, which may have implications for free will and truth. -

The Andromeda ParadoxI don't see what that has to do with the Rietdijk–Putnam argument and/or Andromeda Paradox.

-

Sleeping Beauty ProblemIt's because her appropriately interpreted credence P(T) =def P(T-awakening) = 2/3 that her bet on T yields a positive expected value, not the reverse. If she only had one opportunity to bet per experimental run (and was properly informed), regardless of the number of awakenings in that run, then her bet would break even. This would also be because P(T) =def P(T-run) = 1/2. — Pierre-Normand

I don't think that works.

P(H-awakening) = P(H-run). Therefore either both are 1/2 or both are 1/3. This is expected given the biconditional.

I think it's more rational to say that P(H-awakening) = 1/2 than to say that P(H-run) = 1/3. Therefore I think it's more rational to say that P(H-awakening) = P(H-run) = P(H) = 1/2. -

Sleeping Beauty ProblemThe bet's positive expected value arises because she is twice as likely to win as she is to lose. This is due to the experimental setup, which on average creates twice as many T-awakenings as H-awakenings. — Pierre-Normand

Which of these are you saying?

1. There are twice as many T-awakenings because tails is twice as likely

2. Tails is twice as likely because there are twice as many T-awakenings

I think both of these are false.

I think there are twice as many T-awakenings but that tails is equally likely.

The bet's positive expected value arises only because there are twice as many T-awakenings. -

Sleeping Beauty ProblemRationality in credences depends on their application. It would be irrational to use the credence P(H) =def |{H-awakenings}| / |{awakenings}| in a context where the ratio |{H-runs}| / |{runs}| is more relevant to the goal at hand (for instance, when trying to survive encounters with lions/crocodiles or when trying to be picked up at the right exit door by Aunt Betsy) and vice versa. — Pierre-Normand

I think you're confusing two different things here. If the expected return of a lottery ticket is greater than its cost it can be rational to buy it, but it's still irrational to believe that it is more likely to win. And so it can be rational to assume that the coin landed tails but still be irrational to believe that tails is more likely.

However, it's important to note that while these biconditionals are true, they do not guarantee a one-to-one correspondence between these differently individuated events. When these mappings aren't one-to-one, their probabilities need not match. Specifically, in the Sleeping Beauty problem, there is a many-to-one mapping from T-awakenings to T-runs. This is why the ratios of |{H-awakenings}| to |{awakenings}| and |{H-runs}| to |{runs}| don't match. — Pierre-Normand

I'm not sure what this has to do with credences. I think all of these are true:

1. There are twice as many T-awakenings as H-awakenings

2. There are an equal number of T-runs as H-runs

3. Sleeping Beauty's credence that this is a T-awakening is equal to her credence that this is a T-run

4. Sleeping Beauty's credence that this is a T-run is 1/2.

You seem to be disagreeing with 3 and/or 4. Is the truth of 1 relevant to the truth of 3 and/or 4? It's certainly relevant to any betting strategy, but that's a separate matter (much like with the lottery with a greater expected return). -

Sleeping Beauty Problem

Would you not agree that this is a heads interview if and only if this is a heads experiment? If so then shouldn't one's credence that this is a heads interview equal one's credence that this is a heads experiment?

If so then the question is whether it is more rational for one's credence that this is a heads experiment to be 1/3 or for one's credence that this is a heads interview to be 1/2. -

Sleeping Beauty ProblemI think Bayes’ theorem shows such thirder reasoning to be wrong.

If P(Unique) = 1/3 then what do you put for the rest?

Similarly:

If P(Monday) = 2/3 then what do you put for the rest? -

Sleeping Beauty ProblemP(Unique) = 1/3, as one-third of the experiment's awakenings are unique. — Pierre-Normand

This is a non sequitur. See here where I discuss the suggestion that P(Monday) = 2/3.

What we can say is this:

We know that P(Unique | Heads) = 1, P(Heads | Unique) = 1, and P(Heads) = 1/2. Therefore P(Unique) = 1/2.

Therefore P(Unique|W) = 1/2.

And if this experiment is the same as the traditional experiment then P(H|W) = 1/2. -

The Andromeda ParadoxYou think it's peculiar that in a setup where event A follows B, where one person moves towards those events, that person will see A before the other person — Benkei

No. This has nothing to do with what one person sees. There are distant events happening in my present that I cannot see because they are too far away. According to special relativity some of these events happen in your future even though they are happening in my present. This is what I find peculiar. -

Sleeping Beauty ProblemRegarding Bayes' theorem:

Both thirders and double-halfers will accept that P(Heads | Monday) = 1/2, but how do we understand something like P(Monday)? Does it mean "what is the probability that a Monday interview will happen" or does it mean "what is the probability that this interview is a Monday interview"?

If the former then P(Monday) = P(Monday | Heads) = 1.

If the latter then there are two different solutions:

1. P(Monday) = P(Monday | Heads) = 2/3

2. P(Monday) = P(Monday | Heads) = 1/2

I think we can definitely rule out the first given that there doesn't appear to be any rational reason to believe that P(Monday | Heads) = 2/3.

But if we rule out the first then we rule out P(Monday) = 2/3 even though two-thirds of interviews are Monday interviews. This shows the weakness in the argument that uses the fact that two-thirds of interviews are Tails interviews to reach the thirder conclusion.

There is, however, an apparent inconsistency in the second solution. If we understand P(Monday) to mean "what is the probability that this interview is a Monday interview" then to be consistent we must understand P(Monday | Heads) to mean "what is the probability that this interview is a Monday interview given that the coin landed heads". But understood this way P(Monday | Heads) = 1, which, if assuming P(Monday) = 1/2, would give us the wrong conclusion P(Heads | Monday) = 1.

So it would seem to be that the only rational, consistent application of Bayes' theorem is where P(Monday) means "what is the probability that a Monday interview will happen", and so P(Monday) = P(Monday | Heads) = 1.

We then come to this:

Given that P(Awake | Monday) = 1, if P(Monday | Heads) = 1 then P(Awake | Heads) = 1 and if P(Monday) = 1 then P(Awake) = 1. Therefore P(Heads | Awake) = 1/2. -

Donald Trump (All General Trump Conversations Here)CNN obtains the tape of Trump’s 2021 conversation about classified documents

Except it is like, highly confidential.

...

Secret. This is secret information.

...

See as president I could have declassified it. Now I can't, you know, but this is still a secret. -

Sleeping Beauty ProblemThen, in the "scenario most frequently discussed," SB is misinformed about the details of the experiment. In mine, the answer is 1/3. — JeffJo

So we have two different versions of the experiment:

First

1. she’s put to sleep, woken up, and asked her credence in the coin toss

2. the coin is tossed

3. if heads she’s sent home

4. if tails she’s put to sleep, woken up, and asked her credence in the coin toss

Second

1. she’s put to sleep, woken on Monday, asked her credence in the coin toss, and put to sleep

2. the coin is tossed

3. if heads she’s kept asleep on Tuesday

4. if tails she’s woken on Tuesday, asked her credence in the coin toss, and put to sleep

I think the answer should be the same in both cases.

It may still be that the answer to both is 1/3, but the reasoning for the second cannot use a prior probability of Heads and Tuesday = 1/4 because the reasoning for the first cannot use a prior probability of Heads and Second Waking = 1/4.

But if the answer to the first is 1/2 then the answer to the second is 1/2. -

The Andromeda ParadoxI think this is unnecessarily pedantic.

In one person’s reference frame the event is in the present (or past), and in the other person’s reference frame the event is in the future. I find this peculiar.

And, for the purpose of the Andromeda Paradox, it shows that the second person’s future is inevitable. -

The Andromeda ParadoxYour statement assumes a privileged frame of reference. — Benkei

Which statement? -

The Andromeda ParadoxI also don't see how it applies in this context. — T Clark

A statement such as "a fleet of spaceships has just left the Andromeda Galaxy en route to Earth" is either true or false, even though we don't, and can't, know which.

The "common sense" realist view is that if it's true then it's true for all of us, otherwise it's false for all of us, but if special relativity is correct then whether or not it's true can be relative to our individual movements. -

The Andromeda ParadoxWhile Bill stays put, Ann moves toward the light coming towards her showing the events as they unfold. Of course she's going to see the decision to invade Earth before Bill does. By the time the light reaches her, she's simply closer to it. She's been walking millions of years towards it already. Once Bill sees the decision happening, for Ann at that point, having walked at 5 m/s for all that time, the light reaching her then is 15 days later and the armada is already on its way. — Benkei

But the relativity of simultaneity isn't just about one person seeing something before another person; it's about that thing actually happening for one person before another person. That's what I find peculiar. -

The Andromeda ParadoxDo you feel comfortable saying both are correct because neither has a privileged frame of reference? If yes, what makes the Andromeda example different for you? If not, why not? — Benkei

I don't really understand your question. I certainly accept that special relativity, and its various implications such as the Andromeda Paradox, are correct, but like much of science I find it very peculiar. -

The Andromeda ParadoxSorry. I think the difference you describe is meaningless. — T Clark

You think the distinction between "there is intelligent life in the Andromeda Galaxy" being truth-apt and it not being truth-apt is a meaningless distinction?

The realist would disagree. They would argue that it's truth-apt and either true or false.

The same with something like "a fleet of spaceships has left the Andromeda Galaxy en route to Earth". It's either true or false even if we can't know which it is.

However, what's interesting about special relativity is that it seems to entail that whether or not such a proposition is true is relative to one's reference frame such that if two people cross paths in opposite directions then it can be true for one of them and false for the other. And if it's true for one of them then the future for the other is "fixed". -

The Andromeda ParadoxAs the article asks "Can we meaningfully discuss what is happening right now in a galaxy far, far away?" Answer - of course not. — T Clark

Is that just because we don't know what is happening, or is it because there's nothing happening? A realist would presumably say that something is happening right now in a galaxy far, far way, but if special relativity is true then what's happening right now depends on our individual, relative velocities, such that what's happening right now in a galaxy far, far way in your reference frame isn't what's happening right now in a galaxy far, far away in my reference frame. -

The Andromeda ParadoxPlease explain how "even the slightest movement of the head or offset in distance between observers can cause the three-dimensional universes to have differing content." And how can this purported difference in content cause a difference in simultaneity of months? — T Clark

There’s some math here that might explain it: https://medium.com/mathadam/the-andromeda-paradox-b4bb30a0e372

Given the distance to the Andromeda galaxy one person moving towards another nearby person at just 5 m/s changes the frame of reference enough that there’s a 15 day difference between which events in Andromeda are simultaneous.

And the further the distance the lower the velocity needed to establish such a significant difference. So given a far enough away location even small head movements can bring about a sufficiently different reference frame. -

The Andromeda ParadoxI consider this "paradox" untenable since simultaneity cannot apply to distant events. — jgill

So do distant events occur in the past relative to my reference frame? Or the future? Or not at all? -

Joe Biden (+General Biden/Harris Administration)Continuing in that article:

Mr. Shapley, in fact, also told Congress that his investigation had uncovered some evidence that some of the claims of the elder Mr. Biden’s involvement were mere “wishful thinking.”

He told of an interview conducted with Hunter Biden’s business associate Rob Walker, who told investigators that it was “projection” that former Vice President Biden would get involved in their business ventures.

“I certainly never was thinking at any time the V.P. was a part of anything we were doing,” Mr. Walker said, according to Mr. Shapley.

...

House Republicans sought to portray the testimony as further evidence that Hunter Biden had gotten what they call a sweetheart deal from the Justice Department, even though his agreement to plead guilty to two misdemeanor charges appeared in line with how other first-time, nonviolent offenders were typically treated. Mr. Biden paid his back taxes and penalties in 2021.

Michael

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum