Comments

-

Wittgenstein, Cognitive Relativism, and "Nested Forms of Life"

Yes, of course you're right. It's just that that it isn't like the resemblances between one dog and another, but between a dog and a sculpture of it. We wouldn't confuse a fossil with a living member of the species, would we?

Of course not. But if one wants to explain why we don't confuse them one has to move from the vague metaphor to something more concrete.

That was my only point on the comment. Wittgenstein clearly knows he is being very vague, he anticipates this charge. So to answer your point: "Vagueness is not necessarily OK. But I think that W has a point if he's saying that sometimes it is all you've got," yes, I think this is sometimes true. I was speaking to the specific application.

Family resemblance isn't intended as a basis for biological theorizing. The notion of family resemblances is not intended to do any intellectual work for a biologist.

But it is appropriate for the linguist, philosopher of language, or semiotican? Don't grunts and screams share a family resemblance with speech? The issue is that you still need the "right sort of family resemblance," since all things resemble each other in at least some ways.

The "oh, now I get it, moment" you mention is definitely included as part of enacting or demonstrating understanding, and I have many times had that kind of thing in mind when thinking about it.

Then we're in agreement. I did not take it that this is what meant by behavior. Perhaps he can clarify.

If someone's behavior is expanded to include their thoughts, experiencing, etc. then I see no issue in the saying that understanding a rule can be judged solely in terms of behavior. Although, in this case, wouldn't "behavior" constitute essentially everything it is possible for a person to do (e.g., thinking, perceiving, liking, existing, understanding, being angry, etc.)? Would there be anything a person can do that won't count as behavior? Or to use Banno's phrasing: if "that someone is following a rule is shown by what they do," is "what someone does," anything they do at all?

But then "rule following is something people do, as part of the sum total of anything they do at all," isn't saying much of anything. I was thinking of "what people do," or behavior in terms of Skinnerian stimulus and response. Such a framing has the deficit of being wrong IMO, but it does at least actually say something.

The idea is not to resolve indeterminacy. The idea is that we enact appropriate behaviors even when a characterization of them is simultaneously indeterminate in principle. Social interaction doesn't make rules less indeterminate. We learn how to act appropriately by interacting with our environment, including the appropriate use of words when we interact socially, para-socially or whatever.

Ok, but wouldn't this hold for all activities, not just social ones. And wouldn't this be true or animals as well?

I do think Wittgenstein brings in social interaction to fix the underdetermination problem. That part seems fairly straightforward. I think I might disagree that it actually addressed the problem though. The argument from underdetermination is too strong, it proves too much. -

Perception

It happens every time you dream, it's happening to people who have received chemical paralytic drugs, it's happening to people who are locked in. The burden would be on you to show that bodily interaction is necessary to consciousness.

No it doesn't. The idea that the brain can generate experiences without any access to a very specific sort of enviornment is not "supported by science," in the least. I have already explained why. The enviornment is not simply a "power source," either, this is a comic simplification.

Does a brain generate any experience on the ocean floor? On the surface of a star? In the void of space? In a room filled with helium gas? Torn out of the skull? All your counter examples still involve brains inside bodies and bodies that are inside environments that are in the very narrow range that allow for the production of experience.

Take someone with locked in syndrome. Replace the atmosphere in the room with most other gasses: helium, argon, hydrogen, etc. They will stop experiencing. Turn the temperature down low enough and they will stop experiencing. Turn it up enough and they will instantly stop experiencing. You are abstracting away relevant details and then claiming that the brain can operate in a vacuum. The claim that "science says this is true," is particularly ridiculous. Science says there are no truly isolated systems and science also days that putting a human body in all sorts of only relatively isolated systems—even simply zipping someone into an airtight bag—will cause then to cease having experiences extremely rapidly.

Brain function requires a constant exchange of matter, information, energy, and causation across the boundaries of the brain. Dreaming and locked in syndrome are not remotely counterexamples of this. -

Wittgenstein, Cognitive Relativism, and "Nested Forms of Life"

Yes, this is pretty much the point of family resemblances so I just don't really understand what you are criticizing about it when you agree with it. I feel like you are attributing more to this concept than required and criticizing it for things not intended.

It would be vacuous for a biologist to say "all life shares a family resemblance," and to stop there. Whatever "all life," is it must surely have some sort of resemblance to be deemed "all life" in the first place. What biologists do in reality is posit a constellation of features that make up this "family resemblance," e.g. having a metabolism, undergoing selection, etc. If one stops at the metaphor and introduces nothing else one hasn't said anything. All of being can be said to resemble all that is in some way or another.

And what is understanding over and above the ability to enact or demonstrate understanding?

Chat GPT can enact grammatical rules. Does it understand them? I would say no, understanding has a phenomenological element.

I am pretty sure every mentally capable adult has had multiple experiences where they have struggled to learn some game or set of rules and had an "oh, now I get it," moment. That's understanding. The issue of validating understanding is not the same thing as describing what understanding is, just as being in pain is not equivalent with wincing and grunting.

Attributing rules to the behavior is chronically underdetermined / indeterminate on some level, and this issue regresses chronically. You can observe some behavior whose description by a rule is completely indeterminate; nonetheless, a person attributes a rule anyway.

As a previous poster already pointed out, all empirical science is undetermined. The problem of underdetermination is about as broad as the Problem of Induction or the Scandal of Deduction. It would seem to make most knowledge impossible if one demands "absolute certainty." That's why I never found the arguments about rule following from underdetermination particularly convincing. You could make the same sort of argument about Newton's Laws, quantum mechanics—essentially all empirical claims, or about all induction. That the future is like the past is "undetermined," as is memory being reliable. Thus, the issue of under determination is as much a factor for any sort of social rule following as it is for some person designing their own board game and play testing it by themselves; democratization doesn't eliminate the issue.

But I don't think this warrants nescience vis-á-vis phenomena like "understanding a rule," that we are well acquainted with either. The demand for "absolute certainty" is the result of a good deal of ridiculousness in philosophy. -

Perception

It's perhaps possible to have experiences while replacing a large part of the body with some sort of system that does functionally the same things as the body. But presumably you could also replace parts of the brain with synthetic components in a similar manner. Shall we abstract that away as well?

None of your examples prove that brains can generate experiences "all by themselves." All you do in your examples is substitute parts of the enviornment for functional equivalents. This is not the same thing as the enviornment being irrelevant to or uninvolved in the generation of experience. Indeed, the fact that you have to posit very specific environmental changes in order to preserve the possibility of there being any conciousness at all gives lie to the idea of the "brain alone" producing experience in a vacuum.

Not to mention that it seems uncontroversial that, in actuality, no brain outside a body has ever maintained conciousness. If one is to invoke "the science of perception," in any sort of a realist sense then it seems obvious that lemons are involved in lemons' tasting sour, apples are involved in apples' appearing red, etc. We can speculate all we want about sci-fi technology approaching sorcery (which is what "the Matrix" or a "brain in a vat" is), but this is to follow modern philosophy's pernicious elevation of potency over act in all of its analysis.

It would be more accurate to say that "physical systems give rise to experience" and that these physical systems always and necessarily involve both body and the environment. Truly isolated systems don't exist in nature and the brain couldn't maintain conciousness even if it was magically sequestered in its own universe.

At any rate, when something looks rectangular or big, this is because of interactions between the object, ambient light, and the body; it's the same with color. Color is susceptible to optical illusions, sure, but so to is size, motion, and shape. I have yet to see a good argument why color is "mental precept" all the way down, but presumably shape and size are not.

I am not sure what motivates Michael's response that shape, motion, and size should be seen as "properties of objects themselves," because this is suggested by "the Standard Model." I would assume the assumptions here are reductionist and smallist, since this is normally why people come to the old "primary versus secondary qualities," style distinctions and end up involving particle physics to make a case vis-á-vis perception. I don't think there is good evidence for assuming that reductionism is true until proven otherwise. 100+ years on and even the basics of chemistry like molecular structure have not be successfully reduced to physics. -

Perception

Does this mean we can't talk about the experiences John's brain creates while he's still with us?

No, it means we can't talk about the "brain alone," creating experience.

You'll note that in all your counter examples, e.g. the beam falling on John, you have concocted wild changes to the enviornment, not the brain, in order to sustain the possibility of conciousness, which gives lie to the "brain alone" explanation.

So I'll ask again, show me a brain alone producing conciousness. No enviornment. Your examples all involve radically altering the enviornment so as to have it preform the functions of the body, which is not a counter example. -

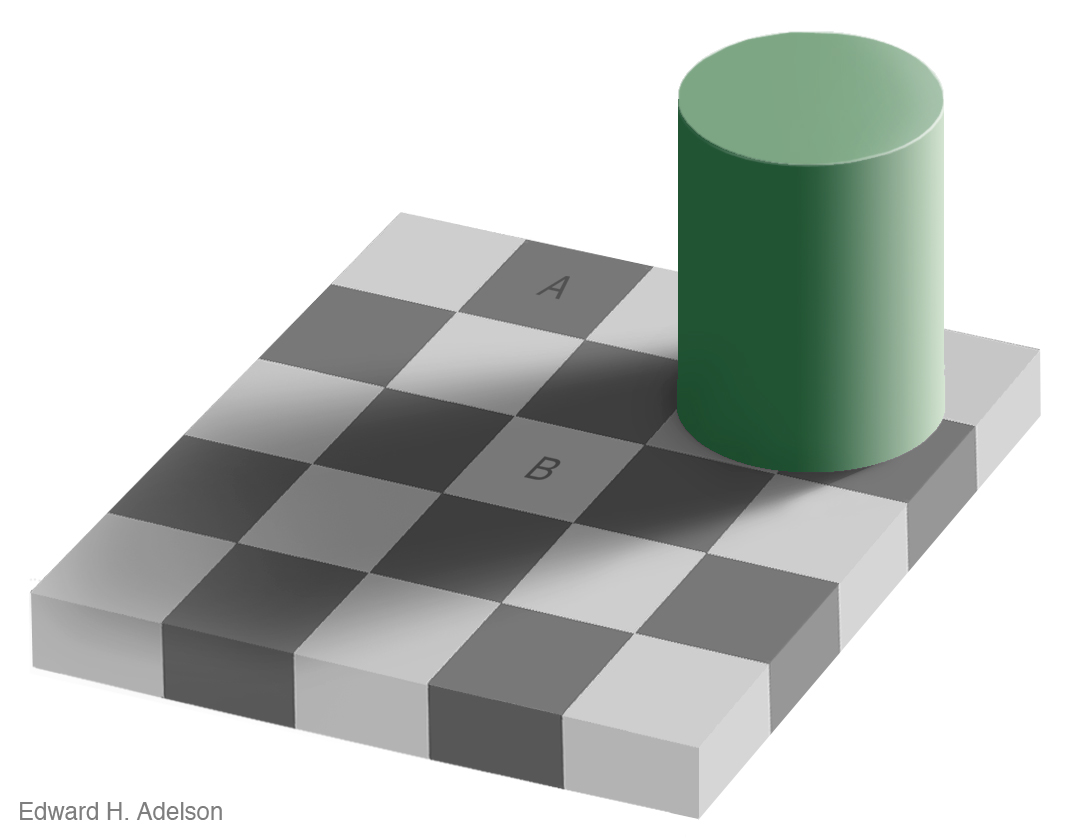

PerceptionConsider this famous optical illusion.

The "big reveal" is that both labeled squares are "the same shade of gray." I have had students refuse to believe this until I snip out one square and put it next to the other.

Of course, this is generally presented as the squares themselves being "the same color." You can confirm this by looking at the hex codes of the pixels that make them up.However, on an account where grayness, shade, hue, brightness, etc. are all purely internal and "exist only as we experience them," it seems hard to explain the illusion. If the shades of gray appear different, and color just is "how things appear to us," in what sense are the two squares the "same color gray?" It seems that their color should rather change with their context. -

Perception

In English it's pretty common to apparently directly equate them, as when we say the tea is cold. But in other languages, it would be that the tea has coldness, or that the coldness is upon the tea

I am not t sure how these are supposed to be counter examples. They still ascribe the property to the thing. Is there a language that does not ascribe color, heat, tone, or taste to things but only to subjects? I am not aware of one.

What about the experiences of people on say, ketamine? Their experiences are in some way "in the language" of earthly life, but they're definitely not reflecting anything in the person's environment. Those experiences appear to be created by the brain alone.

These experiences simply aren't created by the "brain alone."

What experiences will someone on ketamine have if they are instantly teleported to the bottom of the sea, the void of space, or the surface of a star? Little to none, their body and brain will be destroyed virtually instantly in the first and last case. The enviornment always matters.

Less extreme, imagine if we suck all that air out of the room. Will the person's experience remain the same? Obviously not, having access to air is part of their experience. Or suppose the building they are in collapses and a support beam runs through their chest but their brain is left pretty much unharmed? Same thing. Without the body and the enviornment the brain cannot produce experiences.

The brain doesn't produce experience "on its own," or "alone." Producing experience requires a constant flow of information, causation, matter, and energy across the boundaries of the brain and body. It only seems to act "alone" when we abstract away an environment that we have held constant within a precise ranges of values. A human body dies very quickly in the overwhelming majority of environments that prevail in our universe, there are very few where it continues to produce experience for even a few minutes (and this still requires the whole body, not just the brain). -

Wittgenstein, Cognitive Relativism, and "Nested Forms of Life"

Learning the rules is not playing the game.

Right, learning the rules is a prerequisite to playing the game. When we play a game that is new to everyone we sit down with the rules to figure out how to play. This is because the rulebook tells you how to play. One could conceivably learn the rules of a game without ever playing a game, which is a problem for your description.

I am not aware of my mother ever playing baseball but she's been an avid fan of the Mets for their entire existence and I assure you she knows the rules of the MLB quite well, even esoterica like the infield fly rule and pitching balks.

And how does one demonstrate that they understand the rule, apart from moving the piece?

Notice you have moved to demonstration instead of understanding here. As if it would be absolutely impossible to understand a game without playing it. This is what the assertion that there is "nothing more to the rule than what one does in a particular circumstance," forces you into. Yet this is clearly not correct. If I am watching young children set up and play a simple game, e.g. Chutes and Ladders, I can very easily figure out how to play by watching them and/or consulting the rules without playing them. Likewise, I've never played or reffed NBA rules basketball with a three second violation, but I know the rules.

Plus, violating the rules does not mean you do not understand them, so the theory is broken in the other direction as well. I am sure a veteran like Jrue Holiday knows what constitutes a lane violation but he still committed an important one in the finals. Likewise, the Mavs defenders certainly know what a three second violation is and yet they still committed them and complained to the refs about it as if they hadn't broken a rule. Behavior ain't everything. Nor are refs and umps the final word; leagues have had to come out and admit to bad calls (calls contrary to the officials' behavior).

"But how do you validate that you really know them?" is, of course, a different question. By focusing solely on some sort of third party validation you end up in the same place as behaviorists and eliminitivists. Behaviorism has always struck me as very much "looking for the keys under the streetlight because that's where we can see."

A great deal of board games are developed and play-tested by people working in isolation. It seems quite odd to me to say that there are no rules until the person invites some friends or co-workers to try testing the game and that the rules only start to exist when the players begin playing, even though they are playing according to what the creator has told them. The rules only come into being when the game is played? This seems to be another case of philosophers wanting people to entertain strange ideas like Parmenides' "motion is impossible," in order to save some pet theory.

ou posts do not come through on my mentions. That's somewhat discourteous.

No idea, I just hit the reply button. -

Perception

No, I think I get it. You said that movies cannot be funny, the lemons are not sour, and that apples cannot be red. Presumably waterfalls cannot be sublime, sunsets beautiful, noises shrill, voices deep, etc. This is precisely what Lewis is talking about.

I just don't think this separation makes any sense. Nor does it make sense to talk of such things as sourness or beauty existing exclusively in brains. Pace your appeal to "science," the science of perception does not exclude lemons from an explanation of why lemons taste sour or apples from the experience of seeing a red apple. These objects are involved in these perceptions; the perceptions would not exist without the objects.

Brains do not generate experiences on their own. If you move a brain into the vast majority of environments that exist in the universe, onto the surface of a star, the bottom of the ocean, the void of space, or anywhere outside a body, it will produce no experiences. Experience only emerges from brains in properly functioning bodies in a narrow range of environments and abstracting the environment away so as to locate these physical processes solely "in" brains or "brain states," is simply bad reasoning.

Science has nothing to do with it. It's projecting the foibles of modern philosophy onto science.

The key insight of phenomenology is that the modern interpretation of knowledge as a relation between consciousness as a self-contained ‘subject’ and reality as an ‘object’ extrinsic to it is incoherent. On the one hand, consciousness is always and essentially the awareness of something, and is thus always already together with being. On the other hand, if ‘being’ is to mean anything at all, it can only mean that which is phenomenal, that which is so to speak ‘there’ for awareness, and thus always already belongs to consciousness. Consciousness is the grasping of being; being is what is grasped by consciousness. The phenomenological term for the first of these observations is ‘intentionality;’ for the second, ‘givenness.’ “The mind is a moment to the world and the things in it; the mind is essentially correlated with its objects. The mind is essentially intentional. There is no ‘problem of knowledge’ or ‘problem of the external world,’ there is no problem about how we get to ‘extramental’ reality, because the mind should never be separated from reality from the beginning. Mind and being are moments to each other; they are not pieces that can be segmented out of the whole to which they belong.”* Intended as an exposition of Husserlian phenomenology, these words hold true for the entire classical tradition from Parmenides to Aquinas.

Eric Perl - Thinking Being -

Perception

the apple is red" means something like "the apple is causally responsible for a red visual percept".

Reminds me of the opening of Lewis's Abolition of Man.

In their second chapter Gaius and Titius quote the well-known story of Coleridge at the waterfall. You remember that there were two tourists present: that one called it 'sublime' and the other 'pretty'; and that Coleridge mentally endorsed the first judgement and rejected the second with disgust. Gaius and Titius comment as follows: 'When the man said This is sublime, he appeared to be making a remark about the waterfall... Actually ... he was not making a remark about the waterfall, but a remark about his own feelings. What he was saying was really I have feelings associated in my mind with the word "Sublime", or shortly, I have sublime feelings' Here are a good many deep questions settled in a pretty summary fashion. But the authors are not yet finished. They add: 'This confusion is continually present in language as we use it. We appear to be saying something very important about something: and actually we are only saying something about our own feelings.'1

Before considering the issues really raised by this momentous little paragraph (designed, you will remember, for 'the upper forms of schools') we must eliminate

one mere confusion into which Gaius and Titius have fallen. Even on their own view—on any conceivable view—the man who says This is sublime cannot mean I

have sublime feelings. Even if it were granted that such qualities as sublimity were simply and solely projected into things from our own emotions, yet the emotions

which prompt the projection are the correlatives, and therefore almost the opposites, of the qualities projected. The feelings which make a man call an object sublime are not sublime feelings but feelings of veneration. If This is sublime is to be reduced at all to a statement about the speaker's feelings, the proper translation would be I have humble feelings. If the view held by Gaius and Titius were

consistently applied it would lead to obvious absurdities. It would force them to maintain that You are contemptible means I have contemptible feelings', in fact that Your feelings are contemptible means My feelings are contemptible...

...until quite modern times all teachers and even all men believed the universe to be such that certain emotional reactions on our part could be either congruous or incongruous to it—believed, in fact, that objects did not merely receive, but could merit, our approval or disapproval, our reverence or our contempt. The reason why Coleridge agreed with the tourist who called the cataract sublime and disagreed with the one who called it pretty was of course that he believed inanimate nature to be such that certain responses could be more 'just' or 'ordinate' or 'appropriate'to it than others. And he believed (correctly) that the tourists thought the same.The man who called the cataract sublime was not intending simply to describe his own emotions about it: he was also claiming that the object was one which merited those emotions. But for this claim there would be nothing to agree or disagree about. To disagree with "This is pretty" if those words simply described the lady's feelings, would be absurd: if she had said "I feel sick" Coleridge would hardly have replied "No; I feel quite well." When Shelley, having compared the human sensibility to an Aeolian lyre, goes on to add that it differs from a lyre in having a power of 'internal adjustment' whereby it can 'accommodate its chords to the motions of that which strikes them', 9 he is assuming the same belief. 'Can you be righteous', asks Traherne, 'unless you be just in rendering to things their due esteem? All things were made to be yours and you were made to prize them according to their value.'10

But of course the larger point is about the "bloated subject," to which all the contents of the world are displaced. -

Wittgenstein, Cognitive Relativism, and "Nested Forms of Life"

Here is a pretty common experience if you play a lot of board games.

You play a new game. No one involved has ever seen anyone follow the game's rules before. You read the rule book and play. Eventually, there is a disagreement. Maybe even a heated one. Is x move against the rules? Should y be scored like that?

Well, not uncommonly this can be adjudicated by a close reading of the rules, such that the offended party acknowledges that they are wrong (even allowing that the rule might be a stupid one). But on an account that there is "nothing more to the rule than what one does in a particular circumstance," I'm not sure how you're supposed to explain these situations. What "one does" depends on the rules, that's the whole point of game's having rules in the first place.

You've completely reversed things, as if the reason "a bishop moves diagonally under the rules of chess," is "because people move the bishop diagonally." But quite obviously people move the bishop diagonally because they know that's the rule. -

Wittgenstein, Cognitive Relativism, and "Nested Forms of Life"

Well I agree, but I don't think it's on my part. A rule isn't just "whenever behavior is the same." I don't take it this is what PI is trying to say either. -

Wittgenstein, Cognitive Relativism, and "Nested Forms of Life"

My point is that if people are thinking about rules differently then there is a difference, regardless of whether or not their behaviors are identical. Your wife might act the same way if she feels duty bound or somehow coerced into acting like she loves you as if she really loved you, but surely her interpretation of what she is doing (playing the loving wife versus being in love) matters.

So, my disagreement would be with:

That someone is following a rule is shown by what they do. Indeed, there is in a strong sense nothing more to the rule than what one does in a particular circumstance. There is no "understand rules as we do... following the same rules, etc." apart from what we do in particular case.

Pedantically, I think you must mean "was a fossil alive". You are right. We can be (but may not be) quite specific about the criteria that determine each case. It's just that different critieria apply in different cases.

Actually, I meant "is." A fossil bears a close resemblance to the organism it is a fossil of. This could be considered a "family resemblance" in the metaphorical sense, no?

We can be (but may not be) quite specific about the criteria that determine each case. It's just that different critieria apply in different cases.

Right, well, this is precisely what my comment was on. Wittgenstein knows he is being vague. He calls himself out on it. And he seems to say "yup, but what can you do?" Well, I think we can do better. If you're vague enough, you can avoid ever being "wrong" (a plus I suppose), but potentially at the cost of triviality. -

Perception

This is just begging the question lol.

I mean, I could just as well say color words refer to "the colors of objects." And surely my blue car is not located inside my skull. -

Perception

But are extension in space and motion likewise not in external objects? Seems like you could make the same sort of case there.

Same for anything "being a tree" or "being a rock." I don't see how the examples that are supposed to show that color is only "in brains" doesn't equally apply to anything being any sort of discrete object at all. That is, things are only cats, rocks, planets, etc. "inside brains." -

Wittgenstein, Cognitive Relativism, and "Nested Forms of Life"

That someone is following a rule is shown by what they do. Indeed, there is in a strong sense nothing more to the rule than what one does in a particular circumstance. There is no "understand rules as we do... following the same rules, etc." apart from what we do in particular case. The rule is not understood by setting it out in words, but by enacting it.

What one says has less import than what one does. And what is meant by "this form of life" is displayed by what one does - don't look for a form of life just in language, look at what is being done.

Folk are following the same rule as you if they do what you would do.

Wouldn't this just be behaviorism?

But let's say two people are following different rules for some activity. They would both describe the ruleset in different ways and they understand these rules as well as anyone ever understands a rule.

Now lets say that whatever game or activity they are involved in just so happens to provoke identical responses from them. Are they then following the same rule because they had the same responses?

What if the activity has multiple "rounds." They do the same thing for the first two rounds, but in the third the conditions change and their rulesets each tell them to do different things. Now they do different things. Were they following the same rule right up until they began acting differently?

If not, then it seems like behaviorism is missing something.

This works for Turing Machines just as well. We can easily set up machines that will have identical outputs whenever the input is a positive number, but which will have differing outputs if the input is a negative number. You could achieve this very easily by just wrapping the initial input in an absolute value function in one of the computations.

In this case, I think it's pretty clear that they aren't the same Turing Machine setup, even when the input is a positive number and they have an identical output. The operations are different. And on any account similar to computational theory of mind (or really any sort of account of mental events in terms of superveniance) you will also always have differences when people understand rules in different ways. They just might not be easy to observe.

But there are cases where a similar vagueness suits the particular needs of other sciences. For example, the biological definition of life lists certain characteristics which are important to consider, without committing all of them being instantiated in any particular case.

There is no "One True Feature," to point to for defining life, but we generally don't have much disagreement over whether prions or self-replicating silicon crystals are alive. At least, I have never come across a biologist attempting to argue that silicon crystals are alive. But processes involving self-replicating crystals, "DNA computers," prions, etc. could certainly be said to share a "family resemblance," with life. Indeed, all sorts of thermodynamic processes that have selection-like effects could have some sort of resemblance to life. Is a fossil alive? Does it have the right sort of family resemblance? Obviously, to answer the second question means being a specific about what might constitute such a resemblance.

And this is the problem with vague metaphors, they seem to cover too much. If the relation in question is left vague it seems like it could stretch anywhere it wants.

Contrast this with something like computational theory of mind. CTM might very well be a bad theory, I sort of think it is. But it does say something definite enough to be disproven or supported. -

Perception

People can disagree about size and motion as well, and they can also experience these due to simulation of the brain. Are extension in space, motion, speed, etc. all also not properties of distal objects?

Likewise, the "mind independent" existence of any discrete objects seems like it can be called into question based on the same sort of reasoning employed to demote the reality of color. But if discrete objects "don't really exist" "out there" then it's hard to see how one can say anything true about anything. Or at the very least, anything true about anything other than "mere experience" (as opposed to that lofty goal of knowledge of "things-in-themselves.")

IMO, this is just abstraction run amok. Nothing we are aware of exists mind independently. No one can point to anything that is actually mind independent, on pain of such an entity losing its mind independence. I see no good reason to see thing's relationships with minds as somehow "less real," than any of their other relations. "Looking red to people," is a real relationship things have.

Rather, the move to positing all sorts of thing as somehow illusory seems to me to just be an elaborate coping mechanism for dealing with the fact that minds don't sit well in mechanistic accounts of nature — hence the demotion to "less real." -

Wittgenstein, Cognitive Relativism, and "Nested Forms of Life"

So I am not sure I would conflate "triviality" with generality.

Not necessarily. That's why I asked the question: can you think of any conditions in which it could be judged false?

I have no idea why you thought I was referring to the vague concept of "family resemblance" in the first place and not PI65's far more provocative claim that there is no way to define what is common to all languages.

I don't really understand what you mean here by warrant attention. You either agree with the claim or you don't. People can do advanced, even rigorous, linguistics study about the structure of language and still agree with the notion of family resemblance. So unless you are suggesting that modern linguistic contradicts it, I don't understand the consequence of what you are saying. It's like saying that someone who studied the mating behavior of a certain kind of insect is not interested in questions about the definition of life - so what? People interested in specialist linguistic fields are not necessarily going to be interested in a more general concept from the philosophy of language. I suspect you conflate Wittgenstein's philosophical arguments and rhetoric against the logical positivism at the time for a full-blown scientific theory of language which it clearly is not.

I don't. My comments were specifically in the context of that section being supplied in defense of the cognitive relativism thesis, and my point is that it's too vague to usefully say anything about it on its own. The comment on PI65 was ancillary, but to explain:

Wittgenstein draws attention to his own vagueness in PI65. He says "yup, I am dodging the question and refusing to answer it," but then seems to imply that this is because the question cannot be answered, and this is what my objection is to. That is, "there is no one thing" languages share, no specific thing(s) to point to in categorizing and defining them. What I was objecting to is the idea that such vagueness has to be how we speak of language because it isn't possible to do better.

Hence the reference to information theory. It turns out there do seems to be things all physical systems of communication must share if they are to communicate at all. And there are lots of things we can say about the throughput of codes, redundancy, etc. and these do indeed seem to explain a good deal about human language and its structure.

Actually, TLP has some interesting things to say on this even if it was a massive oversimplification and couldn't explain how even the most basic sentences "map to the world." I think Wittgenstein's initial disappointment may have swung him a bit too far over towards seeing difficulties vis-á-vis language as insoluble, and cognitive relativism represents the interpretation of the late Wittgenstein that seems to make virtually every question insoluble. -

Wittgenstein, Cognitive Relativism, and "Nested Forms of Life"

"Family resemblances" is not an "idea" or "theory" that can be proved wrong. It's a vague metaphor that one could call "true" so long as there are any shared similarities between whatever one considers to be a "language-game," (which is also a term that is left vague).

How could it possibly be "proven wrong?" Under what conditions could it possibly be said to be false? Surely all "language games" could always be said to share some constellation of features or they would not be 'all language games.' And this is particularly true because "language game" itself has no firm definition.

The question is not: "is it wrong? " but "is it so broad as to be trivial?" i.e. "all languages must share some things, but I shall not identify any," is a claim that really doesn't say anything of substance, (nor is it a novel claim). Perhaps it was less trivial when it was written. My point is that given advances in the study of language it is certainly now too trivial to warrant much attention. It's main 'benefit' is that it's so completely vague as to be a Rorschach test that theorists can paint anything on they'd like. But this is precisely what makes it a bad way of speaking with rigor, everyone can bring to it whatever meaning they like. That's what I can't imagine Wittgenstein wanting to stick with. The extreme vagueness always struck me as a way to avoid being open to criticisms, but I don't think it was a "feature" in and of itself the way it would be for later "Wittgensteinians."*

I'm not talking about: "this is a claim that has been disproven," I am saying "this level of vagueness is no longer necessary or helpful; there now exist ways to describe similarities in languages, animal communication, and codes with much more rigor—to actually say something beyond the trivial and banal." We might make a similar move in getting rid of the concept of "game" and moving to the broader concept of "system," (which seems to be far more common in linguistics). For one, games like chess pretty much just are their rules and it is not clear that this is true for languages. For languages, rules can be discussed in terms of more fundemental contrasts, limiting the combinatorial explosion of possible sentences, in terms of strengthening redundancy, etc. But then these are things posterior to the rules (and indeed rules seem more flexible and change more often than contrasts like the number of evidentials, plural vs singular vs dual, etc.)

*And I should note that plenty of Wittgensteinians make admirable attempts to dispell the vagueness, even at the risk of theories that sound wildly counterintuitive and implausible. It is only a certain type that seems to really thrive on the vagueness and the ability to avoid error by never really saying anything of substance. -

Semiotics and Information Theory

If you include the entire room you would have the temperature difference. Complete knowledge of the room alone would not give you the cup's status as a clue in a murder case though. In fact, to understand that sort of relationship and all of its connotations would seem to require expanding your phase space map to an extremely wide temporal-spatial region.

The same is true for a fact like "this cup was produced by a Chinese company." This fact might be written on the cup, but the knowledge that this is what the writing actually says cannot be determined from knowledge of the cup alone, and likely not the room alone either.

Likewise, knowledge of the precise location/velocity of every particle in a human brain isn't going to let you "read thoughts," or anything of the sort. You need to correlate activity "inside" with what is going on "outside." That sort of fine grained knowledge wouldn't even give you a good idea what's going to happen in the system (brain) next since it's constantly receiving inputs from outside.

But "building block" reductionism has a bad habit of importing this sort of knowledge into its assumptions about what can be known about things sans any context. -

Semiotics and Information Theory

The idea that humans have a unique ability to understand signs is a direct callback to the divinity of humanity.

It implies that humans have access to a special mechanism that isn't part of the rest of creation.

To believe in this version of semiotics, I am tasked with believing that God gave humanity access to mechanisms that are not available to mere mortal animals.

I am not sure where you got that from. The conversation has several examples of animals making use of signs. The interpretant need not be an "interpreter." We could consider here how the non-living photoreceptors in a camera might fill the role of interpretant (or the distinction of virtual signs or intentions in the media). -

Wittgenstein, Cognitive Relativism, and "Nested Forms of Life"

But has not history shown that what intelligent people called “reasonable” and “unreasonable” has changed from time to time

This is playing off an equivocation in how "reasonable" is commonly used. Of course, if we take "reasonable" to mean something like "appropriate and fair" then this does change quite a bit from time to time and place to place. But this is cultural relativism, not cognitive relativism. This is not "sui generis forms of reason."

The claim of cognitive relativism is that the reason of ancient Greece or of Advaita Vedanta might become completely inaccessible to us—utterly unfathomable. Scholastic logic—its syllogisms and demonstrations—these might seem to make sense to us, but really it's a totally different type of reason. What they mean by "the law of non-contradiction" is not related to what we mean the same term, etc.

On this view, if one reads Aristotle's Organon, it might seem that Aristotle is discussing a logic quite similar to our own (and to "common sense") but really there is no way for us to know if we mean the same thing. Being separated by vast cultural differences, it rather seems we should not mean the same things when we refer to syllogisms, premises, etc.

And yet this thesis seems entirely implausible. For instance, I have never heard of a culture who does arithmetic completely different from any other culture. Where is the arithmetic that is untranslatable?

Now the cognitive relativist can always claims that different forms of arithmetic and logic only seem translatable—that we don't really understand Aristotle or Shankara at all. However, this seems pretty far fetched. And aside from that, it seems to leave the door open on an all encompassing skepticism, for on this account how can anyone be sure that they truly share a form of life with anyone else? -

Wittgenstein, Cognitive Relativism, and "Nested Forms of Life"

Well that makes more sense. I think these sorts of biological constants (constant across diverse historical/cultural variances) is what Wittgenstein is sometimes pointing to with the "form of life." Variance within humanity occurs, and it is sometimes profound, but it occurs in the context of us sharing many other things. This is what allows us to identify morphisms between various socio-historical "forms of life" and translate between them with greater or lesser degrees of ease. But to my mind this capability doesn't jive well with the concept of entirely disparate, sui generis forms of reason (e.g., that Chinese reason is entirely different from French reason).

No doubt we would likely have a harder time translating between our own form of life and that of a comparably intelligent species descended from a squid or turtle ancestor. Yet we would still share much with these species. The difference with extra terrestrials might be even greater (although perhaps not, given convergent evolution).

I tend to think that scientists' arguments to the effect that extra terrestrials with human level technology should be able to communicate with us to some degree through mathematics are at least plausible. We would share with extraterrestrials all that is common to all corners of the universe, limits on the information carrying capacity of various media, ratios, etc. And this might profitably be thought of as an even broader "form of life," the form of life common to all organisms living in our universe.

But a good question might be the degree to which greater intellect and technological mastery allows for better translation across more disparate forms of life. It certainly seems like the application of reason and technology has allowed us to understand bee and bird communications much better for instance.

Wittgenstein's point that any set of actions is still consistent with an infinite number of rules still holds. This holds with the study of nature as well. Any sort of "natural law," based solely on past observations seems doomed to underdetermination.

Yet if we set aside this problem for the behavior of inanimate nature, then it seems like we have decent grounds for determining the "rule-like" strictures organisms hold to. For one, the finite computational and information storage capacities of organisms would seem to rule out rules like "repeat pattern y for 100 years, then begin pattern z." For another thing, natural selection seems to rule out the adoption of a great deal of potential rules. One might not be able to identify a rule that is "set in stone," or similarly a description that is "set in stone," and yet the range of possibilities can be winnowed down enough to have a pretty good idea of where things lay, at least under prevailing conditions. Or as Robert Sokolowski puts it: we might not ever grasp the intelligibility of some entity in every context, but this does not preclude some grasp of it in some particular set of contexts. -

Wittgenstein, Cognitive Relativism, and "Nested Forms of Life"

There are different family structures, there are half siblings, step siblings, etc. Yet, what culture believes in people who do not have biological mothers or fathers? Outside of miracles or myth, where do people accept: "that person was never in the womb?" or "oh yes, Jessie over there is another immaculate conception?"

Absolutely nowhere is the answer. It is truly miraculous for there to be a human being without a biological father or biological mother. A cloned human being would still have a "parent" who had two biological parents and they would still (barring astounding scientific progress) need to be born.

The metaphor is only unproblematic here if one is intentionally obtuse to save it. Notice that you have to take the odd step of moving to the nebulous question of "who is the 'real' parent?" Why? Because it would sound ridiculous to say that adopted children cannot understand what it means for someone to be their "biological" parent.

If someone told you they had no father and had never been born of a woman would your reaction be a shrug and the thought: "why yes, people of some cultures aren't born, I suppose they spring forth from rocks fully formed? There is no truth about biological parentage in these parts." You have to be on a severe overdose of pomo to believe it.

And to be honest, I think the continual contrasting of pernicious forms of relativism with "Final Answers" (capitalized of course), "One True Canonical Descriptions," "The Only Right Way," and the like, is a strawman/false dichotomy.

As I see it, A.C Graying desire is to hold on to the idea that there is one common essence for "truth", "reality", and "value" because the only alternative is "cognitive relativism." However, what I was suggesting is we need not fall into relativism either. First, words like "truth", "reality", and "value" will have multiple uses and thus have family resemblances that will related these word conceptually. These multiple uses are discovered by examining the forms of life which are grounded in the some human activity. That said, these concepts can take place in such radically different forms of life, the family resemblances are not strong enough to call them related. Hence, I introduce the term "stranger" to describe such a case. For example, if we visit another world where the inhabitants utilize symbols like 1, 2, +, -, etc and made expressions such as 1 + 1 = 3 were carried out, would we want to say this is some sort of arithmetic that was carried out? Or is the judgment so radically different that we would not want to call it "arithmetic"? To say "truth" is relative seems to presuppose that there is something conceptual linking all these words together but somehow the outcomes conflict. But that need not be the case, if these concepts are used is such dramatically different ways in which humans act and judge in entirely different ways, why should we even talk as if they had some relationship that deserve to fall under the banner of "truth".

Grayling is talking about the cognitive relativism thesis, not any thesis about cultural relativism. That the same symbols are used for different operations can be explained in terms of cultural relativism. Cultural relativism certainly seems to be the case. Indeed, it's so apparent and been so long accepted that it seems trivial.

The claim Grayling is discussing is the claim that it is impossible to identify other forms of life, or at least any particular variances between our form of life and others', such that translation between forms of life is also impossible. On this view, translation is impossible because we experience the world entirely differently, not because our systems are different.

If aliens use marks that look like "1+1=3" that doesn't seem to make us cognitive strangers. Indeed, if "3" is just the symbol for "2" and the other symbols match up to our usage, then our systems are almost identical.

The cognitive relativism thesis would rather be that the strangers use a form of mathematics that is so alien that we can never recognize it as such. They have their own system of pattern recognition and systematic symbol manipulation, and it is simply beyond us.

Is this possible? Perhaps in some respects. Plenty of animals have shown they can do basic arithmetic. Yet when has a pig ever used the Pythagorean Theorem or a crow solved a quadratic equation? It seems possible that aliens might have math that is as beyond us as our math is beyond pigs. It seems like more of a stretch to say different human cultures could have this sort of difference. It even seems implausible to say that all alien maths should be beyond us, given that our simple maths is not beyond crows or other more intelligent animals.

Re PI 65, I think this has simply been proven wrong by advances in linguistics and information theory. We can identify similarities. I find it hard to even imagine Wittgenstein wanting to argue this point in the modern context given his respect for the sciences. -

Wittgenstein, Cognitive Relativism, and "Nested Forms of Life"

I'm not sure how the vague metaphor here is supposed to address the point TBH.

But funny enough this is a point of contention in Wittgensteinian circles precisely because he uses a lot of vague metaphors.

Do we need to police the use of the words "truth", "reality" and "value", so we can ensure a unifying meaning for each of these terms?

On some accounts, isn't such policing the only way words can have any meaning at all?

In my personal opinion though, the answer is no. Truth has an ability to assert itself quite well in human affairs, e.g. Lysenkoism or the debate over "Aryan" versus "Jewish" physics.

Oh, surely, members of the same family can disagree without ceasing to be members of the family. There's no black-and-white rule here - just shades of grey.

Well, herein lies the difficulty of relying too heavily on metaphors. When it comes to family relations, it seems that they can exist even if no one believes they do. For example, if Ajax is the biological father of Ophelia, this relation of paternity exists even if neither Ajax nor Ophelia (nor any of their family members) are aware of it. And not only that, but evidence of the paternity relationship is "out there" to be discovered.

Yet because this holds for families does it mean it holds for notions of the True or the Good? -

Does physics describe logic?I suppose that, per most forms of physicalism, physics does have to describe human logic in a certain sense. Can it do it? That's an interesting question.

-

Does physics describe logic?That's a pretty broad question. There is a fairly popular related view in physics today called "pancomputationalism." Per this view, the universe might be profitably seen as a "quantum computer that computes itself" (as a cellular automata lattice).

People have used this sort of idea to create computational and communications based theories of causation, which are pretty neat. Past states of a system end up entailing future states (or a range of them). This seems right in line with the idea of cosmic Logos in some respects. It's also a version of causation that seems to deal with some of Hume's "challenges."

However, it's worthwhile to recall that when steam engines were the new hot technology physicists also wanted to think of the universe as "one giant engine/machine." Now, this conception actually did tell us a lot, but it wasn't perfect. The same is probably true here. For one, if the universe is a "computer" in this way it cannot have true continua, and yet empirical evidence is inconclusive on the question of if the universe is ultimately discrete/finitist. If it wasn't discrete, it might still be "computation-like," but it wouldn't be computation because it would involve infinite decimal values.

The ability of ZX Calculus to construct QM is interesting here but I haven't really looked into it. -

Wittgenstein, Cognitive Relativism, and "Nested Forms of Life"

But Witt shows is that the world has endless ways of being “rational” (having ways to account, though different), and so we can disagree intelligibly in relation from those practices. Ultimately we may not come to resolution, but that does not lead to the categorical failure of rationality, because a dispute also only happens at a time, in a context (which also gives our differences traction).

I don't think Wittgenstein shows this at all, as evidenced by the extremely diverse directions this thread is taken in by different Wittgensteinians. He leaves this incredibly vague; vague enough that a common take is that rationality just bottoms out in cultural presuppositions that cannot be analyzed. This view in turn makes any conflict between "heterogenous cultures" or "heterogenous language games," either purely affective/emotional or else simply a power struggle— i.e. "fight it out." This is especially true if the individual subject is just a nexus of signifiers and power discourses.

I think Grayling raises an important point on this subject. Can we identify these cultural differences? Can we understand differences in "forms of life?" If the answers are "yes," then reason maintains a sort of catholicity.

When you say reason doesn't suffer a "categorical failure" "because a dispute also only happens at a time, in a context," does this mean that such failures can eventually be overcome at other times and in other contexts? If so, then limitation doesn't seem to lie in reason itself, but in people's finite use of it, their patience, etc.

But of course the more relativist reading here is that nothing can ever overcome these differences.

Now we can NOT understand lions, as a physical impossibility

You can show a child videos of mammals, including lions, and they can tell you if it is demonstrating aggression or not. If the lion comment is taken head on it is just stupid. Mammals have a pretty good toolset for displaying basic emotions to one another, particularly at the level of aggression and threat displays. Horses and dogs are likewise quite capable of giving off signs that they are going to bite you or kick you if you get close to them, and in general people don't need to be taught these. Toddlers intuitively understand that the dog or cat with ears retracted, teeth bared, emitting a low growl, etc. is not friendly. These behaviors make sense as threats. Teeth and claws are dangerous to other animals. There is a shared reality that allows for translation here.

Pace Wittgenstein, we do understand Chinese gestures much better than Chinese. That's why people who don't share a language communicate through gestures. Gestures aren't arbitrary. There is a difference between stipulated signs and natural signs, and some gestures are more natural than stipulated (e.g. pointing, human signs of aggression, etc.).

I don't disagree with this. But I think that our practices are a bit more complicated than this seems to propose. If we say that rationality is a question of our agreement in ways of life, we seem to eliminate the distinction between those agreements that we call "correct" or "incorrect" by some standard that is not set by our agreement and those agreements that are simply a matter of making a deal, so that "correct" and "incorrect" do not apply. You will understand, I suppose, that I think that agreements that are correct or incorrect are, by and large, rational agreements and the other kind are, roughly, matters of taste. (The difficulty of agreements about values sits awkwardly between the two.)

Right, and on questions of things that are not matters of taste, nature sometimes offers a neat adjudication of the issue. Aspects of nature are law-like and this gives us a non-arbitrary standard for rule interpretation. The "culture all the way down view," obfuscates the fact that when culture contradicts nature it runs headlong into failure. Rule evolution and selection occurs in a world full of "law-like behavior."

Indeed, it's hard to see how "rules" could be particularly useful but for a world that itself has regularities. -

Is the real world fair and just?

There is a lot of interesting stuff on the contradictory nature of "sheer indeterminate being," or a "sheer something." A lot of time it's death with in an information theoretic context. Floridi writes a bit about this in his Philosophy of Information on "digital ontology" (although it's not specifically on Hegel). David Bohm's implicate order stuff, e.g. "why difference must be fundemental and come before similarity," is another.

From Terrell Bynum's chapter in the Routledge Handbook of the Philosophy of Information, "Informational Metaphysics:"

Note: dedomena is Floridi's term. It means: “mind-independent points of lack of uniformity in the fabric of Being” – “mere differentiaedere” (he also refers to them, metaphorically, as “data in the wild”).

"Let us consider what a completely undifferentiable entity x might be. It would be one unobservable and unidentifiable at any possible [level of abstraction]. Modally, this means that there would be no possible world in which x would exist. And this simply means that there is no such x. [ . . . ] Imagine a toy universe constituted by a two-dimensional, boundless, white surface. Anything like this toy universe is a paradoxical fiction that only a sloppy use of logic can generate. For example, where is the observer in this universe? Would the toy universe include (at least distinguishable) points? Would there be distances between these points? The answers should be in the negative, for this is a universe without relations. "

(2011, Chapter 15, p. 354) [This is Bynum quoting Floridi's 2011 "The Philosophy of Information," which is quite good, but dense.]

Thus, there can be no possible universe without relations; and since dedomena are preconditions for any relations, it follows that every possible universe must be made of at least some dedomena. (Note that there might also be other things which, for us, are forever unknowable.) There is much more to Floridi’s defense of Informational Structural Realism, including his replies to ten possible objections, and I leave it to interested readers to find the details in Chapter 15 of The Philosophy of Information. Floridi views the fact that his ontology applies to every possible world as a very positive feature. It means, for example, that Informational Structural Realism has maximum "portability,” “scalability,” and “interoperability.”

Regarding portability, Floridi notes that:

"The most portable ontology would be one that could be made to ‘run’ in any possible world. This is what Aristotle meant by a general metaphysics of Being qua Being. The portability of an ontology is a function of its importability and exportability between theories even when they are disjointed ([their models] have observables in common). Imagine an ontology that successfully accounts for the natural numbers and for natural kinds."

-

Is the real world fair and just?

I added a more detailed link. Lawvere would be the guy who got the ball rolling in this.

Anyhow, we both know "but it doesn't work in classical logic," is a terrible argument in most philosophical contexts. You seem to want to fall back onto formalism (and a simplistic one at that) thinking it can "set the record straight." But this is not what formalism can do for us. Hell, "it does work in classical logic," is not a particularly good one either.

Edit: The system in Spencer Brown's "Law's of Form" is another one that has obvious parallels to the Logics. -

Is the real world fair and just?

Classical logic can't handle all sorts of stuff. Hegel's logic has generally been dealt with in a category theoretic framework. Or: here

Not that this makes a difference for the arguments about world history. Obviously we can't model out world history (or test such models for that matter). Classical logic would be even more useless here. You can however make a broadly empirical case for such arguments. For example, Fukuyama butchers Hegel, but he does provide better case studies and empirical support than most political philosophers. Honneth stays truer to Hegel and has a similar methodology. -

Politics, economics and arbitrary transfers.Such payments are huge. Remittances, people working in wealthier nations and sending money back home, absolutely dwarf all the charitable and government aid given to lower income countries. This is one of the reasons that low income countries don't have particularly high incentives to keep their people from emigrating. Hence why plans to stop migrants normally involve keeping them in some third country (that country is willing to hold them up in exchange for some sort of reward because the remittances would not come back to them anyhow).

Remittances also dwarf loans and foreign private investment, which is why wealthy countries don't tend to have much leverage here. -

Is the real world fair and just?

The problem of people deciding where they want to end up and working backwards for a justification is possible given any type of philosophical method (e.g. it seems hard to deny that Russell didn't do just this at times; rather than his scientism preventing this, it just served to obfuscate it). Nor do I think such a move is always unwarranted. If you have a good "project" it can make sense to try to find a way to save it.

But the larger problem here is that a genetic fallacy is still a genetic fallacy. Bad motivations don't make someone wrong. Falsifiability hasn't even proven to be a particularly good metric for demarcation of the sciences. Mach attacked atoms as unfalsifiable. Quarks were called, not without merit, "unfalsifiable pseudoscience." Plenty of work in quantum foundations is still regarded as unfalsifiable pseudoscience even as it results in tangible discoveries.

Popperian falsifiability itself ends up failing an empirical test of its own ability to properly demarcate "good and bad theory" or "good and bad science." -

What can we say about logical formulas/propositions?

Right, I was just pointing out that this is almost certainly what the reference to "in modern theory," was referring to. This is how the French makes it into English sources.

Saussure is relevant to the conversation at hand in that his later post-structuralist disciples eventually worked themselves towards totally divorcing meaning from authorial intent and context. And this move was given an almost political connotation, a "freeing of the sign." Although one might question if some of the further evolutions of this way of thinking might not just succeed in freeing language from coherence and content.

I think there is actually a connection here to how formal grammar is conceptualized. In either case, the focus becomes signs' relations to other signs, pretty much to the exclusion of context or content. -

What can we say about logical formulas/propositions?

Curiously, the BE article also has to take refuge in modern French words to express itself:

It's a nod to Saussure (and his demonic, hyper-nominalist post-modern semiotics of destruction—as opposed to our Augustine and Co.'s virtuous and sure triadic semiotics of life).

English-speaking philosophers who embrace contemporary French philosophy have to be very careful to use the French, lest they commit a massive faux pas like pronouncing Derrida's "différance" with a French accent. This is embarrassing indeed. The whole point is that différance and différence are pronounced exactly the same, and so one can only tell the difference when looking at them on paper (the victory of the logocentric over the phonocentrism of Saussure's Grammar, which has now been deconstructed).

However, the idea that signs might have something to do with a res or referent is terribly naive, if not downright provincial. "Intent of the speaker?" In grammar?

Friend, surely you know that both the author and the utterer have been dead for decades now? It would be totalitarian, not to mention brutish to suppose that intent should be allowed to tell people how they should construct their meaning, or that the properties of res/signified should play any determinant role in shaping the meaning/dicible in some sign relation. After all, people are themselves just signifiers, nexuses of sign-based discourses. -

An Argument for Christianity from Prayer-Induced Experiences

I don't know how historical progression would work if people never died. Death seems as important to the development of the race as the death of individual cells is to the development of a single person. If Man, as a corporate entity, is the focus of salvation history, then death seems to play a crucial role.

Is the assumption here that suffering only exists "down here?" This is generally not an assumption for universalists or for the early Church in general. There is still Hell and purgation (purgation for all, even the saints on some accounts). Presumably what is required on Earth may be required in some form after death.

Purgation is not the final destination though, but rather the requisite precondition for deification.

Count Timothy von Icarus

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum